1. Introduction

1.1. Internet of Vehicles (IoV)

IoV, one of the rapidly developing area of Internet of Things, is transforming the modern transportation landscape by enabling real-time communication between vehicles, infrastructure and other entities such as manufacturers and service providers [

1]. In IoV, vehicles equipped with sensors and communication systems can relay data about their location, speed, and even the occurrence of potential hazards, such as sudden braking or adverse weather conditions [

2]. When this information is shared with other connected vehicles and traffic management systems, it can increase awareness among all participants in the network, reducing the likelihood of accidents and making more informed decisions. Beyond safety, connected vehicles can revolutionize urban mobility by optimizing traffic flow, reducing congestion and improving parking resource management [

3].

However, IoV faces significant challenges related to the secure and efficient sharing of data between different stakeholders. Current centralized systems create data silos that lead to fragmentation and limited interoperability [

4]. In addition, these centralized systems are prone to data breaches that compromise sensitive information such as vehicle status, driver behaviour and insurance records. The lack of a standardized, transparent and trustworthy platform further hinders collaboration among stakeholders and reduces the efficiency of operational processes [

5]. Therefore, there is a need for an approach to build a secure, transparent and interoperable data-sharing platform that fosters trust, ensures data privacy and improves efficiency within the connected car ecosystem.

1.2. Blockchain

Blockchain technology was first introduced in 2008 to support the cryptocurrency Bitcoin and has since attracted significant interest due to its potential to revolutionize industries beyond finance [

6]. In a blockchain network, data is stored in consecutive blocks that are linked together to form a chain. Each block contains a set of transactions or messages that are verified and encrypted by a network of distributed participants, often called nodes or miners. Once a block is added to the chain, it becomes immutable, ensuring that the recorded data cannot be modified or deleted, thus providing a tamper-proof and secure ledger [

7]. Nowadays, blockchain technology has emerged as a revolutionary solution to the challenge of secure and transparent data sharing across industries. Its decentralized, immutable and tamper-proof nature makes it particularly suitable for managing sensitive data and ensuring trust between untrusted parties. Blockchain enables seamless information sharing among multiple stakeholders, ensuring data integrity and traceability while protecting privacy [

8].

1.3. Hyperledger Fabric (HLF)

HLF is an open source blockchain framework developed by the Linux Foundation as part of the Hyperledger Project specifically to meet the needs of enterprise-class blockchain applications [

9]. Unlike public blockchains that rely on open participation and resource-intensive consensus mechanisms, HLF is designed to operate as a permissioned blockchain, where only authorized entities are allowed to join the network. This permissioned architecture makes it particularly suitable for environments such as connected car networks, where privacy and controlled participation are critical [

10]. One of the main advantages of the HLF is its use of smart contracts, called “chaincode” in Hyperledger terminology. Chaincode defines and automates business logic, ensuring that transactions between participants are executed according to predefined rules [

11]. This automated and secure contract management process simplifies complex workflows in connected car networks, including the management of vehicle status, insurance policy claims, and parking facilities. This is particularly useful when participants need to establish trust in a decentralized network without relying on a central authority. In addition, HLF's multi-channel architecture is a defining feature that sets it apart from other blockchain solutions. Channels in HLF can be thought of as private “sub-networks” within a larger blockchain network. Different organizations can create specific channels and share information only with the participants that need access [

12]. HLF also emphasizes data privacy through its fine-grained access control. In a network of connected vehicles, data generated by sensors, usage patterns, and maintenance logs may require different access rights for different stakeholders. HLF's endorsement policy adds additional security by allowing organizations to specify which members must approve a transaction before it becomes part of the ledger [

10].

1.4. Motivation and Challenges

The rapid proliferation of Internet-connected vehicles and the emergence of the IoV have revolutionized the transportation system, enabling vehicles to share data such as traffic conditions, operational status, and environmental information in real time. However, the increasing reliance on data sharing poses significant challenges related to data privacy, security, trust, and scalability that traditional centralized systems have struggled to effectively address [

13].

Blockchain technology, with its decentralization, offers promising solutions to these challenges [

8]. In particular, HLF has strong scalability while ensuring efficient and secure transactions [

10]. By leveraging this technology, our research aims to design a blockchain-based system that can handle the complex requirements of IoV, such as real-time data exchange, privacy protection, and scalability, while building trust among different stakeholders, such as manufacturers, insurance companies, and traffic authorities.

Despite the potential of blockchain technology, there are still a number of challenges waiting to be resolved in order to build a robust and efficient system for IoV [

14]:

Data Security: IoV involves sensitive data such as vehicle location, operational status and user identity. Ensuring that data is shared securely and only with authorized parties without compromising user privacy is a complex challenge.

Performance: IoV generates large amounts of data in real time, requiring blockchain systems to handle high transaction throughput while keeping latency low. The design must address the trade-off between decentralization and performance.

Trust Among Stakeholders: Building trust in a decentralized environment with different stakeholders such as manufacturers, insurance companies, and traffic authorities requires strong consensus mechanisms and governance models.

Data Isolation: Isolation of specific data ensures the rights and interests among different organizations. Blockchain systems need to develop functionality that is tailored to the specific needs of the organization to ensure proper management of specific data.

1.5. Our Contributions

In this paper, we propose a blockchain-based system architecture for IoV using HLF. Our contributions are summarized as follows:

Multi-Channel Design: We introduce a multi-channel architecture in HLF specifically tailored for IoV. In the system, different types of data are exchanged across multiple channels involving various organizations. Each channel is dedicated to specific types of data such as vehicle status, insurance policies, and traffic conditions. This approach allows different stakeholders to collaborate efficiently while maintaining strict access control policies.

Cross-Channel Communication using Chaincode: We develop and implement cross-channel communication using chaincodes, which is a key aspect of our multi-channel approach. This allows for the secure querying and exchanging of data across different channels. For instance, vehicle status data from one channel can be queried by a related insurance policy channel. Chaincode can enhance the system’s capability and provide a comprehensive data management solution.

Functional Testing: Self-defined node parameters ensures that organizations can choose the number of nodes according to their needs. Chaincode deployment and testing ensures stable information exchange between organizations. By implementing and testing our multi-channel system in a real blockchain environment, from deployment to functionality, we demonstrate its scalability, feasibility and reliability.

2. Literature Review

Blockchain-based product traceability systems are receiving increasing attention from industry and academia. Ding et al. [

15] proposed a permissioned blockchain-based double-layer framework for a product traceability system that addresses key challenges such as privacy protection, scalability, and regulatory compliance. In their framework, the consortium blockchain serves as the main layer, sharing product traceability information among organizations and allowing consumers to access the data, while a private blockchain is used for sensitive data storage within each enterprise. Unlike traditional single-layer systems, the double-layer framework separates data entry from data sharing. This separation enhances the scalability of the system and ensures better performance when handling a large number of transactions. In addition, the double-layer structure allows regulatory agencies to participate in the traceability process, which enriches traceable information and improves the reliability and credibility of the system.

Hussain et al. [

16] proposed a blockchain-enabled secure communication framework aimed at enhancing trust and access control within the IoV ecosystem. The framework includes two core modules: a vehicle registration system and a message alert generation system, which use smart contracts to ensure the secure interaction of autonomous vehicles. A key aspect of their solution is the use of Ethereum’s decentralized environment to manage interactions, ensuring that vehicle data integrity and reliability are maintained throughout communication. The proposed framework introduces a decentralized design that leverages the proof of stake (PoS) consensus mechanism to handle transaction validation, which reduces computational overhead compared to proof of work (PoW). This makes the system more energy efficient and suitable for real-time vehicle-to-vehicle communication, an essential feature in IoV scenarios where efficiency and timely data exchanges are critical.

Ndzimakhwe et al. [

17] presents an innovative approach to solving privacy and data integrity issues within electronic health records (EHR) systems by employing HLF as the foundational technology. HLF allows for granular privacy control, ensuring that only authorized participants have access to particular data sets. This aligns with the privacy requirements critical in healthcare environments. Chaincode in the framework manages user permissions effectively. This contract-driven mechanism supports fine-grained access controls, enabling users to grant and revoke data access permissions dynamically. This system guarantees data immutability, meaning any changes to the health records are securely logged in a transparent yet privacy-preserving manner. The relevance of this study to connected vehicle networks lies in its demonstration of how HLF can manage sensitive data in a secure, distributed manner, with a high emphasis on privacy and selective data sharing.

3. Our Design

Our system focuses on secure and trustworthy data exchanging between various stakeholders, such as vehicle manufacturers, insurance companies, service stations, and regulatory bodies. We leverage the features of HLF—particularly its multi-channel architecture, consensus mechanisms, and chaincode—to provide the necessary security, privacy, and efficiency in vehicle data management.

3.1. System Architecture

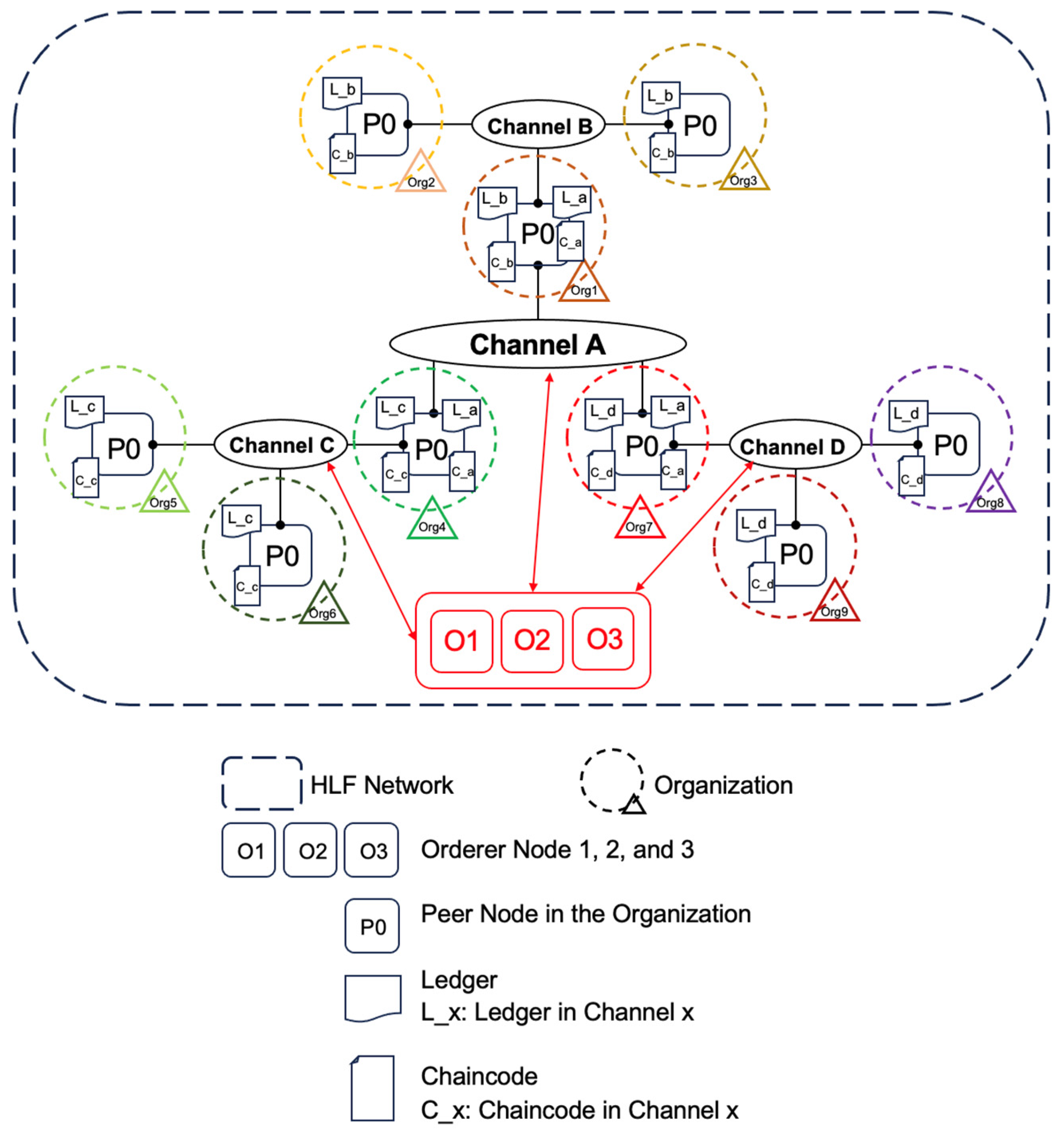

As shown in

Figure 1, our HLF-based system is composed of several components that work together to enable a decentralized and secure environment for data exchanging.

3.1.1. Organizations and Peer Nodes

In HLF, each stakeholder is represented by an organization [

9]. Our system consists of nine organizations. Org1 represents the vehicle manufacturer and holds the running status of the vehicle. Org2 and Org3 are also manufacturers. But they are below Org1. In other words, Org2 and Org3 can also be branches of Org1. Org4 stands for vehicle insurance company. It holds the insurance status of the vehicle. Org5 and Org6 are like Org2 and Org3, they are also branches of Org4. Finally, Org7 stands for traffic management department. It has information on real-time road conditions and surrounding facilities, such as parking lots, etc. Org8 and Org9 belong to the subordinate departments of Org7. Each organization has its own peer node that is responsible for executing chaincode, endorsing transactions, and maintaining the distributed ledger. Each peer node is linked to its organization's membership service provider (MSP), which ensures proper identity management [

10]. Multiple peer nodes can exist within each organization for information storage and sharing. For testing purposes, we set up only one node per organization.

3.1.2. Orderer Nodes

Our system employs a distributed ordering service, consisting of three orderer nodes Orderer1, Orderer2, and Orderer3. We use the etcd Raft consensus protocol to ensure fault tolerance and maintain consistency across the network [

18]. The orderers are responsible for collecting transactions from different organizations, ordering them, and then creating blocks to be distributed to peers. These orderer nodes are distributed among the stakeholders to avoid centralization, thereby providing resilience to failures and attacks.

3.1.3. Channels

One of the critical aspects of our system is the use of multi-channel architecture to achieve data isolation, privacy, and efficient communication. The channels allow different groups of organizations to share data without exposing it to unauthorized entities. There are four channels in our system.

Channel A serves as the central channel for the entire system. It connects the exchange of information between different organizations. It realizes the sharing of different kinds of information across organizations. For example, the traffic management department can call the insurance information of specific vehicles through Channel A. For security and authority reasons, only main organizations can join Channel A. Branches, such as Org2 and Org3, and subsidiaries cannot join.

Channel B includes Org1, Org2, and Org3. They share information about the real-time status of the vehicle, such as position, speed, etc., within the channel.

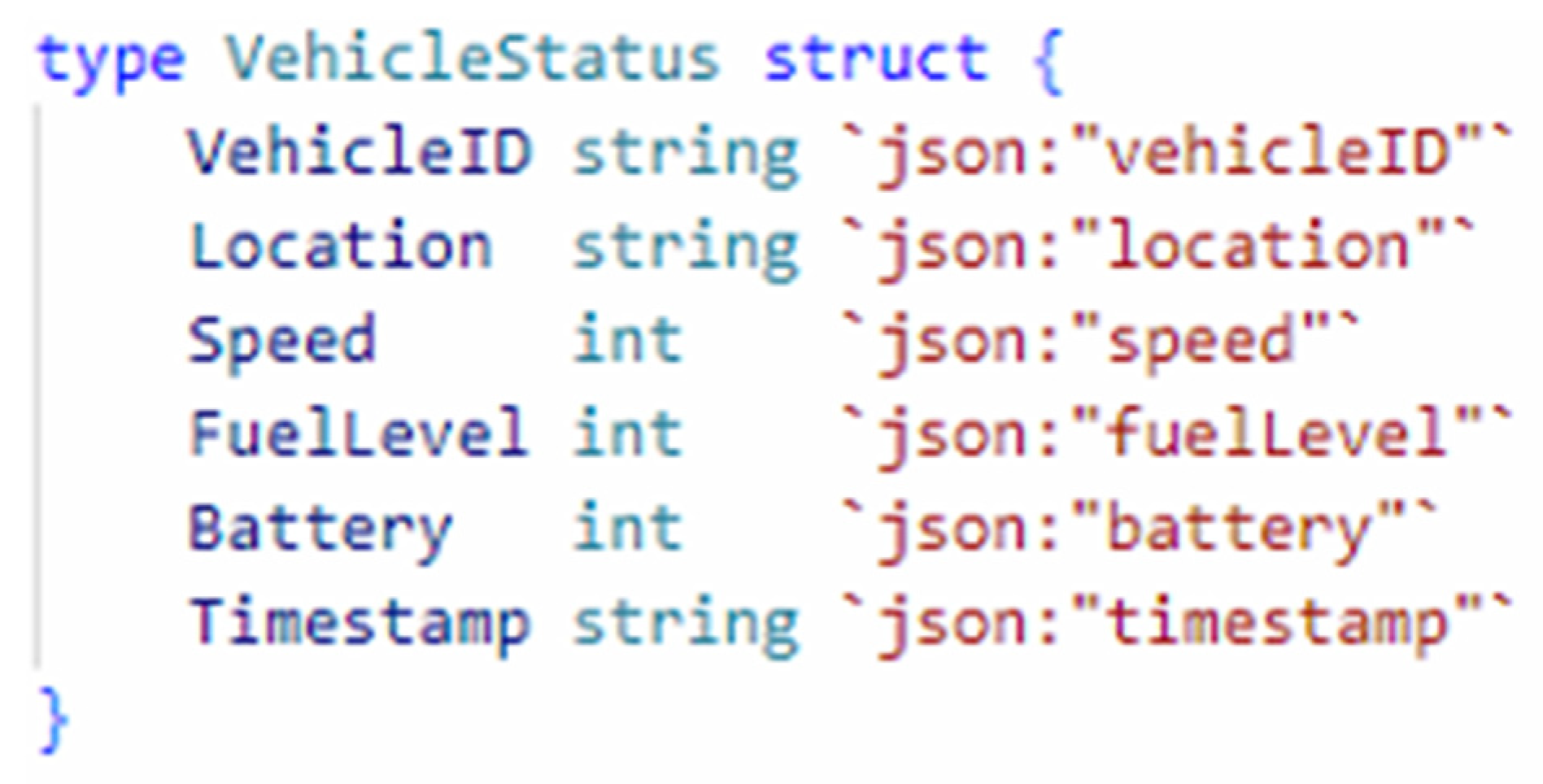

Figure 2 shows the structure of the real-time state of the vehicle that we set up during the testing phase.

Channel C includes Org4, Org5, and Org6. Serves as a conduit between insurance companies, primarily for the sharing of vehicle insurance information.

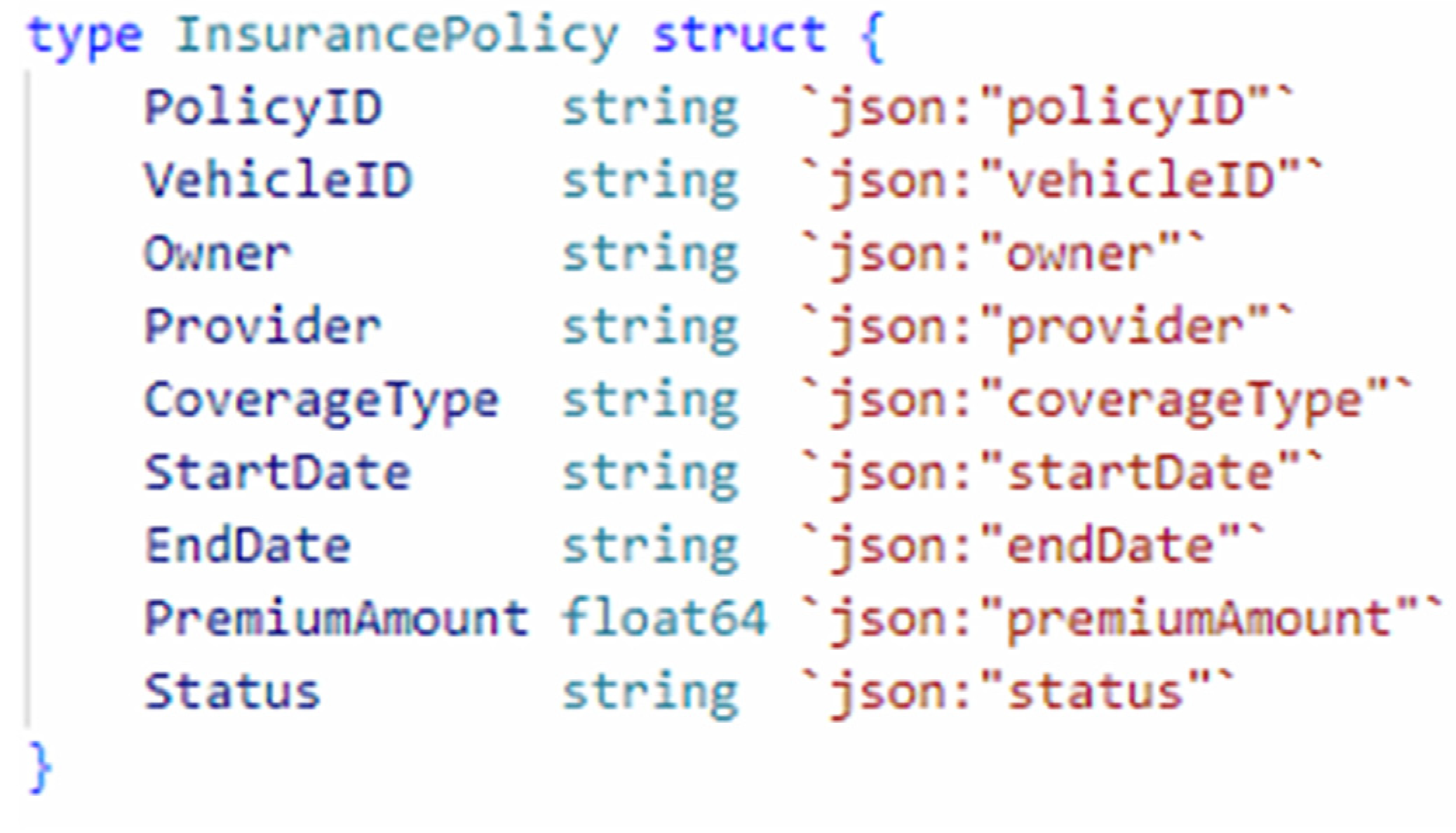

Figure 3 shows the structure of the insurance information.

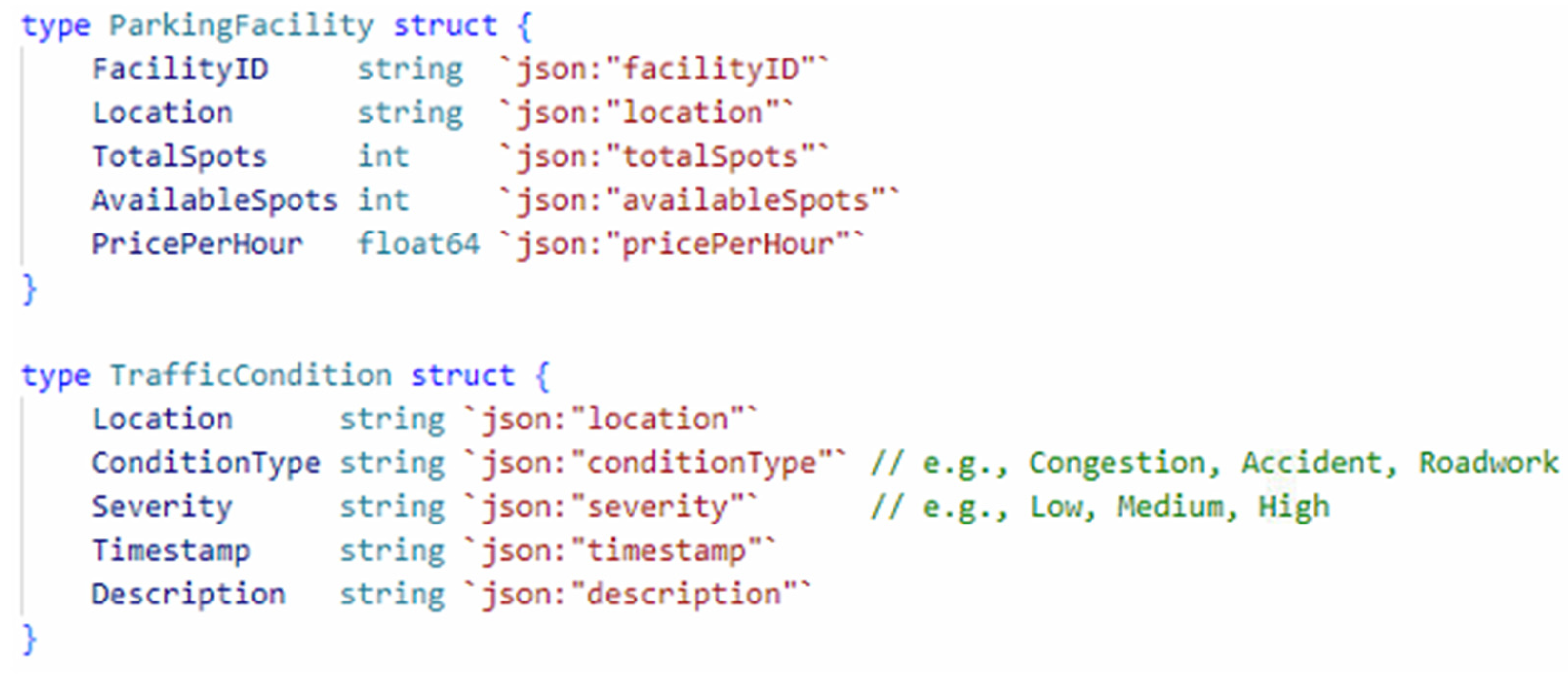

Channel D includes Org7, Org8, and Org9. Serve as a conduit between the traffic management department and subordinate departments to share information such as real-time road conditions and surrounding facilities. In our testing, we set up real-time information on parking lots.

Figure 4 shows the structure.

3.1.4. Certificate Authority (CA)

CA plays a crucial role in establishing identity management, authentication, and authorization. CA is a fundamental component for managing identities and securing communication in the HLF network. Each organization has its own CA to issue digital certificates and keys, ensuring secure identity management and mutual authentication among the nodes.

The CA issues digital certificates to peers, orderers, and clients, which serve as cryptographic credentials for verifying identities. The CA issues Transport Layer Security (TLS) certificates to peers, orderers, and clients, enabling encrypted communication between network components. This ensures that data transmitted over the network remains secure and prevents unauthorized access. Also, The CA can revoke certificates when necessary, such as when a participant's credentials are compromised. This ensures that revoked participants cannot access or interact with the network.

Here is the workflow of CA. Participants are first registered with the CA, which assigns them identity attributes. During enrollment, the CA generates a key pair and issues a certificate to the participant. HLF’s MSP uses CA-issued certificates to manage identities within the blockchain network. MSP ensures that only valid identities interact with the network. TLS certificates secure communication between peers, orderers, and clients. Additionally, multi-channel architecture ensures that only authorized members access specific channel data.

3.1.5. Docker and CouchDB

Our system is deployed using Docker for container orchestration. Docker provide a scalable and manageable environment for a distributed blockchain network. All peers, orderers, and CAs are deployed as Docker containers. This ensures easy deployment, isolation, and scalability. It allows each organization to manage its resources independently.

Meanwhile, each peer node in the network maintains a ledger and uses CouchDB as the state database. The integration of CouchDB with peer nodes facilitates efficient querying of vehicle and service-related data.

3.2. Consensus

The consensus protocol used in this system is the etcd Raft consensus protocol. It is a key feature of HLF to ensure the ordering of transactions in a secure and efficient manner [

18]. This protocol is particularly well-suited for enterprise blockchain applications where resilience and stability are critical.

It the system, etcd Raft achieves consensus through a leader election process. One node is elected as the leader, and it coordinates all transactions among the other nodes, which act as followers. This leader-based mechanism ensures that the transactions are processed in a sequential manner, minimizing conflicts and ensuring data integrity. The leader is responsible for proposing transaction blocks. Once a majority of the nodes (the followers) agree on the proposed block, it is committed to the blockchain [

12].

In our system setup, three orderer nodes are deployed as part of the etcd Raft consensus group. Each orderer node runs an instance of the etcd Raft protocol to replicate data and to ensure that all nodes have the same view of the ledger. This setup enhances the fault tolerance of the network. It allows the system to continue operating even if one or two of the orderer nodes fail.

3.3. Chaincode

Chaincode is a crucial element of the system. It acts as the smart contract logic that defines the business processes and governs transactions between participants in the blockchain network. It operates on the peer nodes of the network and is responsible for enforcing the rules of interaction, ensuring data integrity, and automating workflows in a decentralized manner [

19]. In our system, chaincode is written in Go language. The lifecycle of chaincode deployment follows several steps. It begins with packaging and installation. Then, each organization will approve it. And finally, the chaincode will be committed to the channel. This process ensures that the defined logic is agreed upon and trusted by all participants [

9].

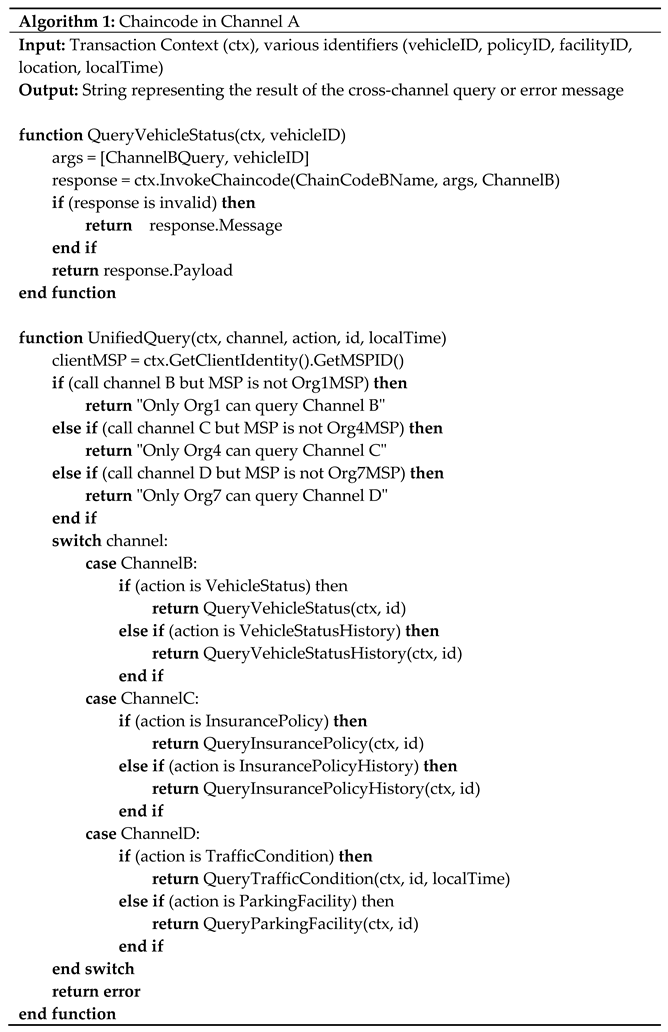

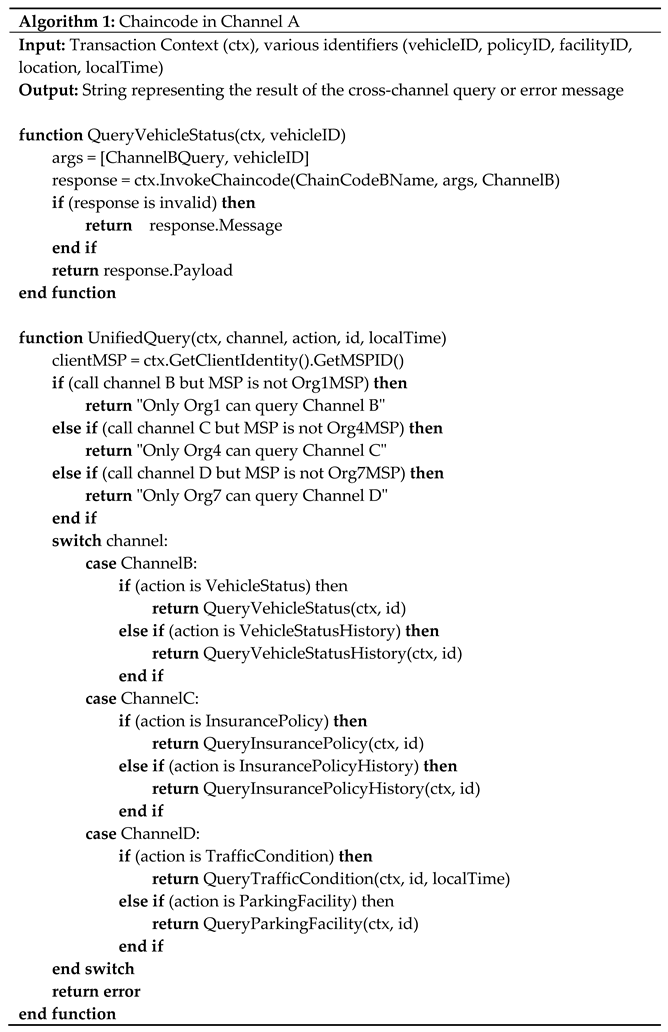

3.3.1. Channel A

In Channel A, the chaincode is designed to facilitate cross-channel queries that enable Channel A to interact with information present in Channels B, C, and D. The system leverages HLF's inter-channel capabilities, called InvokeChaincode API, to fetch information about vehicles, insurance policies, traffic conditions, and parking facilities from different channels. The chaincode includes functions for querying vehicle status and history from Channel B, querying Insurance policy information from Channel C, and querying traffic conditions and parking facility data from Channel D. The chaincode is shown in Algorithm 1.

The chaincode related to query is used to retrieve information from Channel B, C, and D. Their structure is similar, thus we only show QueryVehicleStatus() in Algorithm 1. It accepts a vehicleID as input and then invokes the chaincode on Channel B to get the data. The output is the current status of the vehicle, such as location. Also, The UnifiedQuery() function acts as a generic entry point that allows users to access multiple query types through a single function call. Based on the input parameters, this function will dynamically decide which specific query function to call. This simplifies user interaction with the system and provides a streamlined method to access multiple datasets across different channels.

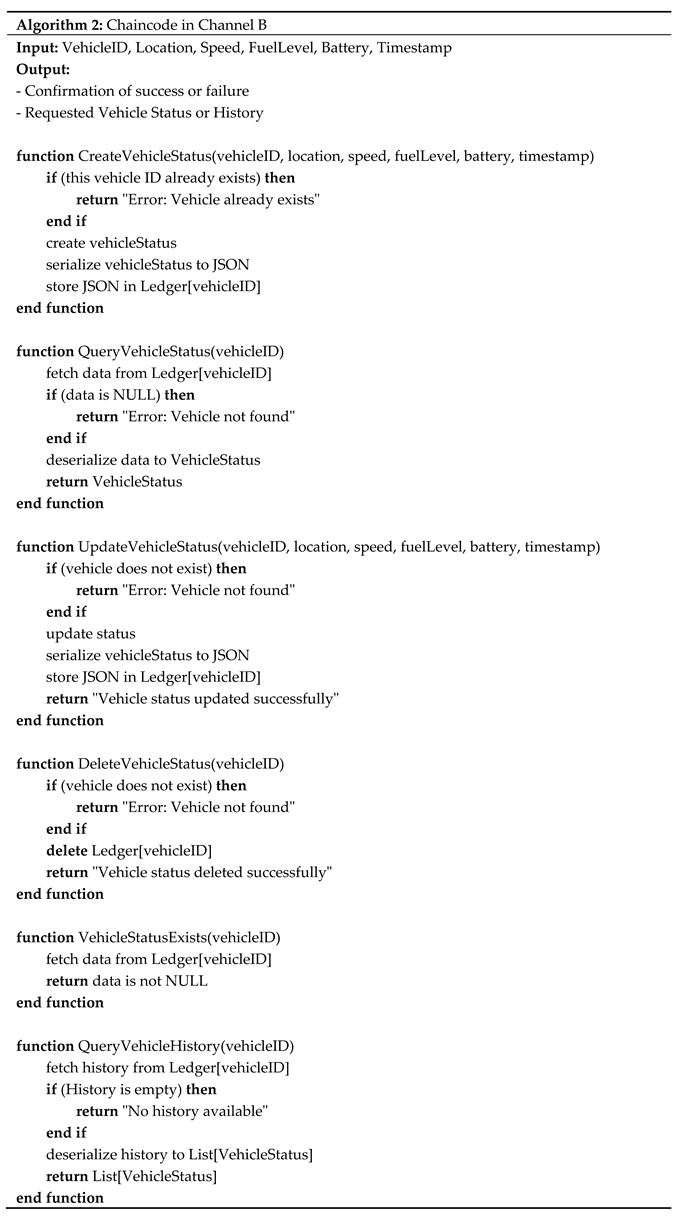

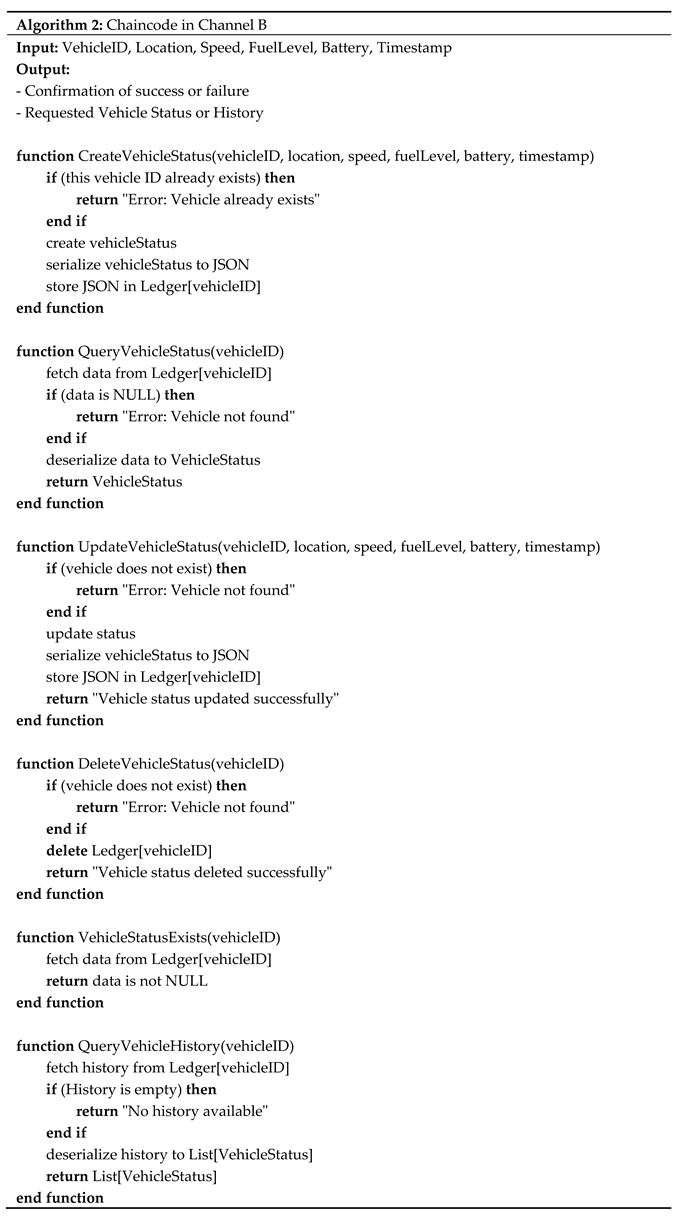

3.3.2. Channel B, C, and D

The chaincode in Channel B, C, and D offer a set of functions to perform CRUD (Create, Read, Update, Delete) operations and historical queries. Algorithm 2 shows the chaincode in Channel B. For additions, the implementation of CRUD in Channel C and D is the same as in B. Therefore, we only show the algorithm in Channel B.

These functions ensure complete lifecycle management of the vehicle status data. CreateVehicleStatus() adds a new vehicle status record to the ledger and validates that the VehicleID does not already exist. Finally, it encodes the data as JSON and writes it to the ledger. QueryVehicleStatus() retrieves the latest status for a given vehicle. It can decode JSON data. UpdateVehicleStatus() updates an existing vehicle record. It can modify the fields and writes the updated JSON back to the ledger. DeleteVehicleStatus() deletes a vehicle status record. It can verify the record exists before removing it from the ledger. Chaincode in Channel C and D have similar structure.

4. Deployment and Testing

4.1. Deployment

Before testing of our system, deployment of the HLF network and chaincode is an important step.

4.1.1. Deployment of HLF Network

In this section, we outline the step-by-step process for deploying a HLF network to support our proposed multi-channel system. The deployment involves generating cryptographic materials, configuring the network structure, creating channels, and connecting peers from different organizations to their respective channels. Below, we detail each step of the deployment process.

Step 1: we use the

cryptogen tool to create cryptographic certificates for all network entities [

9]. These materials are critical for creating secure communication and identity verification. By using this tool, we can create MSP directories and TLS certificates for peers and orderers.

Step 2: we use the configtxgen tool to define the structure and policies of the network. Totally, we create the genesis block, which defines the orderer and consortium configurations, configuration files for application channels and for updating the anchor peers of each organization in each channel.

Step 3: we submit the channel configuration transactions to the orderer to create channels. In this step, peer channel create command is used for creating each channel.

Step 4: it is necessary to connect peers from various organizations to their respective channels. We need to set the peer's MSP, TLS root certificate, and address and use the peer channel join command to associate each peer with the appropriate channel block.

Step 5: peer channel update command is used to update transaction to designate specific peers as anchor peers.

4.1.2. Deployment of chaincode

This section describes the process of deploying and activating chaincode on the HLF network. Chaincode, which implements the business logic of the system, must be packaged, installed, approved, and committed across all relevant organizations within their respective channels. This ensures consensus on the chaincode’s configuration and enables its functions to be executed securely on the blockchain. The following steps outline the detailed deployment process.

Step 1: We need to package the chaincode into a format suitable for distribution across the network [

9]. The chaincode is developed using Go in our system. The

peer lifecycle chaincode package command is used to package the chaincode into a

.tar.gz file. This file contains all the chaincode source code and metadata.

Step 2: The packaged chaincode is installed on all peer nodes of the participating organizations in the respective channel. For example, in Channel D, the packaged chaincode is only installed in Org7, 8, and 9. Therefore, environment variables specific to each organization are set to identify the target peer for installation. The peer lifecycle chaincode install command is executed to install the chaincode package on the peer node. Once installed, the chaincode’s unique ID is queried and stored for further approval steps.

Step 3: To ensure all organizations agree on the chaincode’s parameters, each organization must approve the chaincode definition. The peer lifecycle chaincode approveformyorg command is used in this step.

Step 4: Once all organizations have approved, the chaincode is committed to the channel, making it active for use. In this step, The peer lifecycle chaincode commit command is used and the peer lifecycle chaincode querycommitted command validates the chaincode deployment.

Step 5: Finally, we can test the chaincode by invoking its functions and querying data.

4.2. Testing

4.2.1. Channel Creation

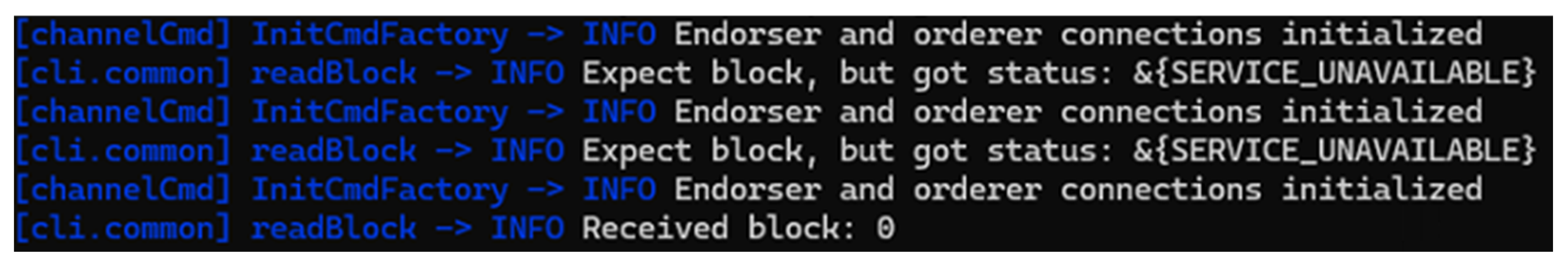

As shown in

Figure 5, creation of Channel A begins with initializing endorser and orderer connections. This confirms the communication setup between peers and the orderer. Also, initial attempts to retrieve the channel genesis block resulted in various statuses. NOT_FOUND suggests the block was not yet created and SERVICE_UNAVAILABLE indicates temporary unavailability of the orderer service. After a series of retries, the genesis block for each channel was successfully retrieved. In a nutshell, the retry mechanism can ensure resilience against transient failures and the genesis block shows successful channel creation.

4.2.2. Peer Joining Test

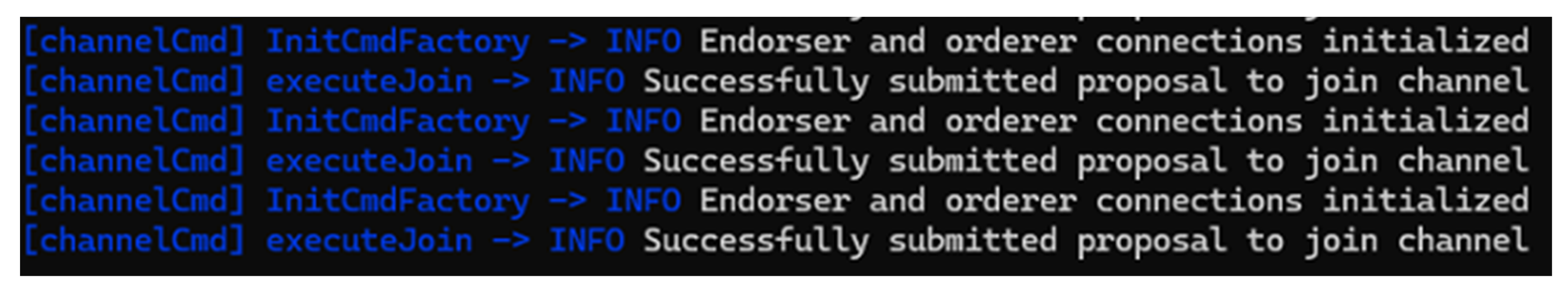

As shown in

Figure 6, each peer successfully submitted a proposal to join the channel. The successful join operation confirms that the channel block is valid and the peers are configured correctly to participate in the channel. These results confirm proper configuration of MSPs, certificates, and block files.

4.2.3. Anchor Peer Update Test

Anchor peers for each organization were updated to enable inter-organization communication. As shown in

Figure 7, updates to anchor peer configurations were successfully submitted. All anchor peer updates were processed without errors, indicating robust coordination among the peers, orderer, and the configuration update mechanism.

4.2.4. Query Channel Information Test

It is necessary to query information about the four channels to verify their proper configuration and deployment. The goal is to ensure that all participating organizations have successfully joined their respective channels and that the ledger state is synchronized across peers. As shown in

Figure 8, as we expected, Org1, 4, and 7 joined into Channel A properly. The consistent ledger height validates proper transaction propagation and block generation across the channel. Also, “_lifecycle” shows that the chaincode lifecycle management process is operational. Due to the excessive length of the image,

Figure 8 only shows the information for Org4, omitting the information for Org1 and Org7. The information for Org1 and Org7 is the same as for Org4, except for Endpoint and Identity.

4.2.5. Deployment of Chaincode Test

In this part, we tested the deployment, approval, and functionality of the chaincodes across the respective channels. As shown in

Figure 9, the chaincode installation succeeded across all peers in Channel B. Also, the generated package identifier is same across all installations. It confirms successful packaging and propagation.

Then, as shown in

Figure 10, all participating organizations, Org1, 2, and 3, approved the chaincode definition for Channel B. It means endorsement policies and chaincode parameters were correctly validated and accepted.

After approval, as shown in

Figure 11, chaincode was committed successfully on all peers in Channel B. The committed version 1.0 and sequence 1 confirm the initial deployment. Finally, it is functional test.

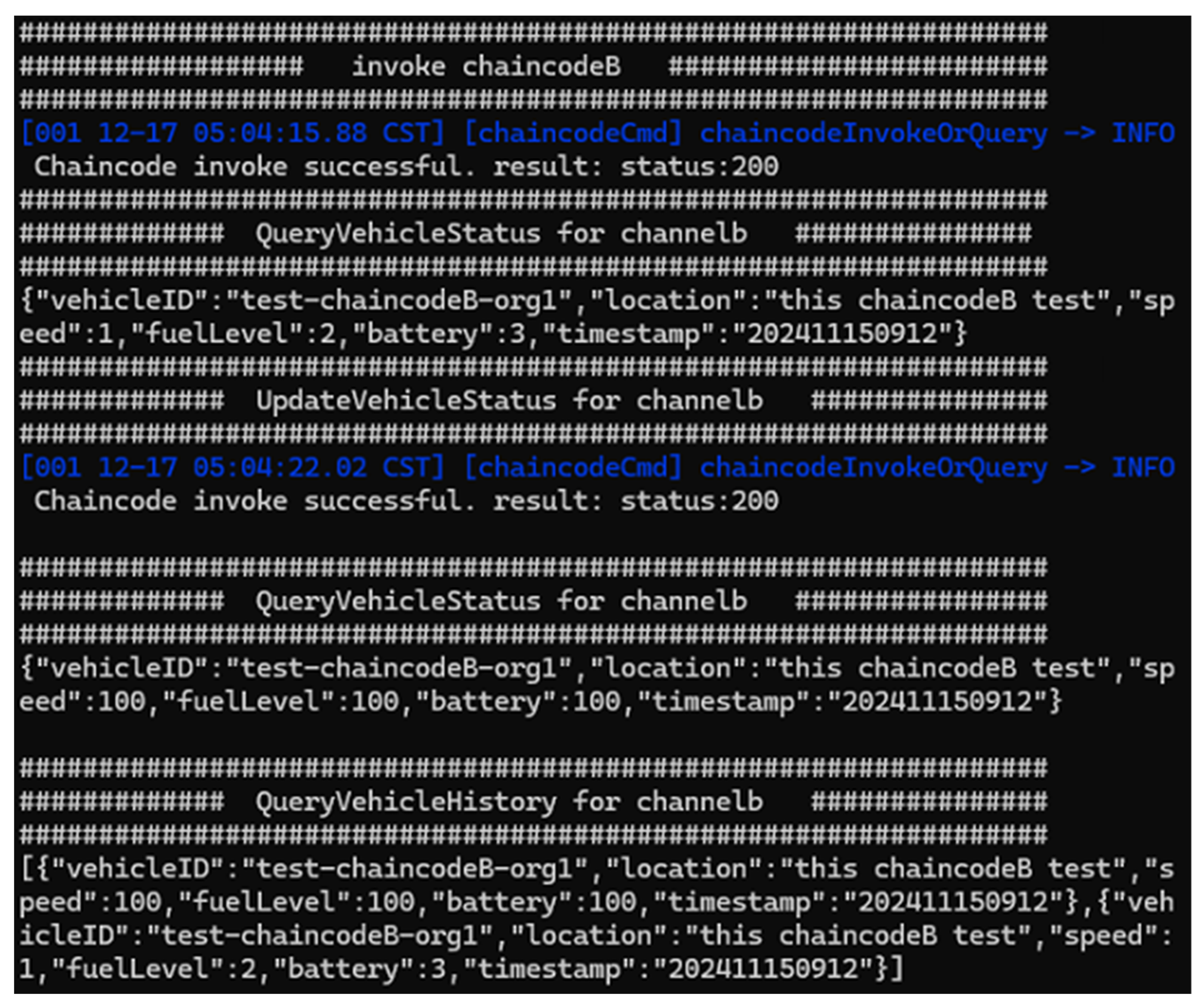

As shown in

Figure 12, in Channel B, we operated CreateVehicleStatus() function to create statues in advance and the result shows that chaincode executed the CreateVehicleStatus() function successfully, indicating proper function implementation. Then, by operating QueryVehicleStatus() function, vehicle status was retrieved successfully with expected values. Next, by operating UpdateVehicleStatus() function, vehicle status was updated correctly and the updated values were reflected in subsequent queries. In the end, the history query correctly retrieved all changes to the vehicle status. The basic function of Channel B, C, and D is the same, so only the result of channel B is shown here.

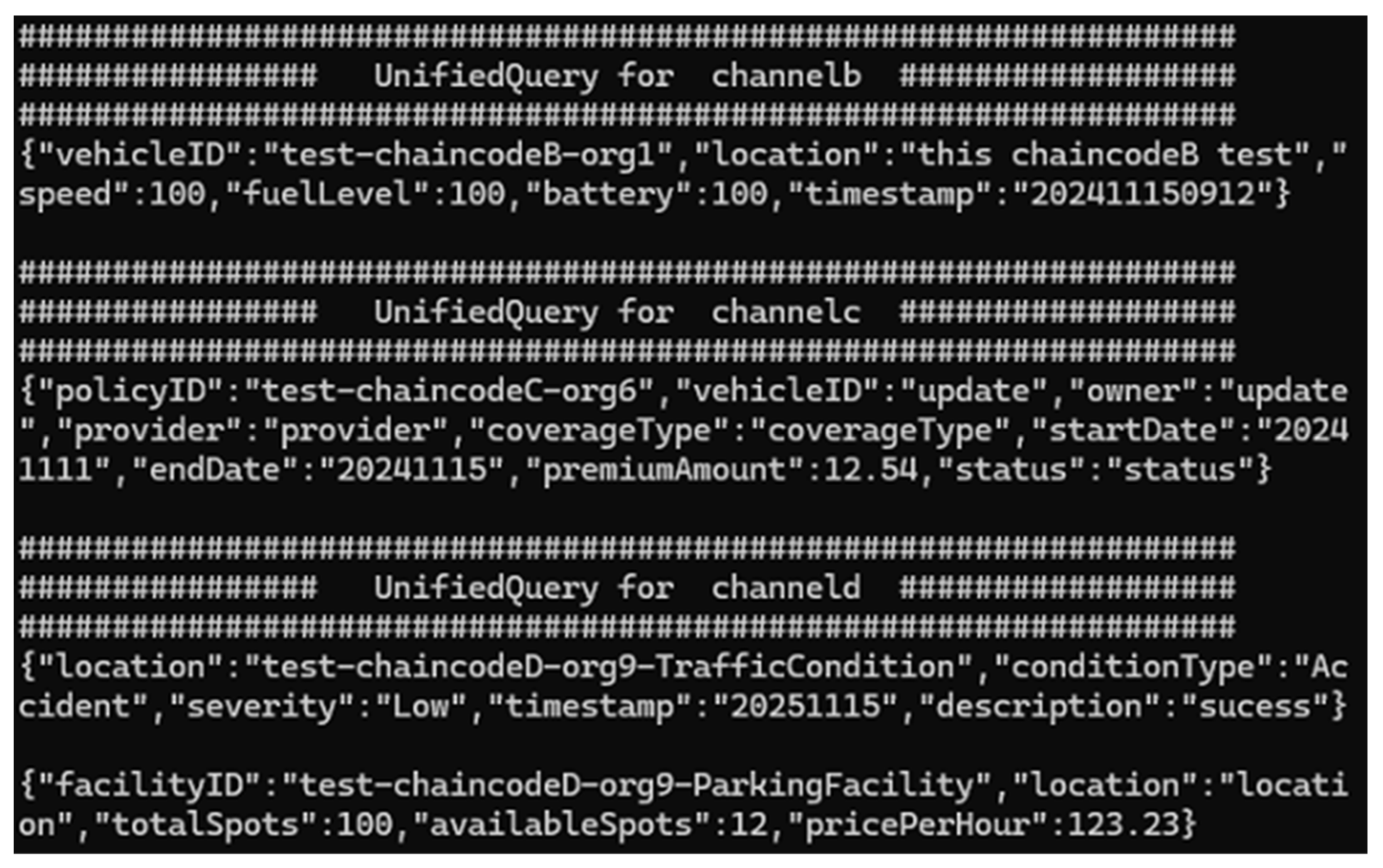

For Channel A, which is the central channel of the system, we did unified query test across channels. As shown in

Figure 13, we can see that unified queries successfully retrieved data across Channel B, C, and D. It shows the effective multi-channel communication.

5. Analysis

5.1. Pros

The decentralized architecture of HLF is the key feature of our system. It can eliminate the need for a central authority and reduce the risk of a single point of failure. Therefore, it ensures that no single organization has any unilateral control over the data. Meanwhile, the use of blockchain ensures that all transactions are immutable once submitted. The multi-channel structure provides logical isolation to ensure that only authorized parties have access to sensitive data. We find this feature particularly useful in use cases involving multiple departments. Especially where data collaboration is required. Thanks to HLF, our system utilizes TLS for secure communications and encryption for identity management. It can make the system resistant to common cybersecurity threats. Also, access control through MSP ensures that only authenticated and authorized participants can interact with the network. Finally, in the central channel, Channel A, of our system, unified queries allow seamless integration and interaction between different data domains.

5.2. Cons

First, during the testing phase, we find that consensus mechanisms, cryptographic operations, and approval from multiple organizations may result in slower transaction processing compared to traditional database systems. This may not be suitable for high-frequency trading environments. Second, setting up and maintaining a HLF network requires a significant number of operations. Updating or expanding systems can be challenging compared to conventional systems. Third, the size of the ledger grows over time, with higher storage requirements compared to traditional databases. When the system is large enough, it may be inefficient to store large amounts of data on the chain.

5.3. Comparison with Traditional Database Systems

Traditional database system typically managed by a single authority or organization. Decisions about the database, such as access rights and data updates, are centralized. For blockchain, data is replicated across multiple nodes in a peer-to-peer network. Each participant holds a copy of the ledger. It can ensure data redundancy and robustness against single-point failures [

20]. Traditional database system relies on user roles, passwords, and firewalls for security. A single breach in the central database can expose the entire dataset [

21]. For our system, logical isolation ensures sensitive data is only accessible to authorized parties. Transactions are validated by multiple nodes, making it highly resilient to fraud or cyberattacks. As for performance, traditional database system can have high throughput. It is optimized for speed, with support for thousands of transactions per second. It is also suitable for applications requiring immediate data updates [

22]. However, blockchain system may have transaction latency due to consensus protocols. It is optimized for trust and focuses on data integrity.

6. Conclusion and Future Work

This paper presents a multi-channel HLF-based IoV system. Our system leverages the decentralized, secure, and immutable architecture of blockchain to enhance data integrity, privacy, and trust among stakeholders in the IoV.

The key contribution of the system is the multi-channel structure. Separation of data into different channels can ensure data privacy and efficient collaboration among different organizations. The use of chaincodes enable secure and automated transactions across channels. Testing phase validates successful deployment, chaincode operation, and efficient data exchanging across channels.

Several areas remain for further research and enhancement. In the future, first, we will focus on improve user interfaces and developer tools to simplify the interaction and deployment of blockchain-based IoV systems for stakeholders. Moreover, we desire to explore the integration of edge computing for real-time data processing at the vehicle level. It is necessary to reduce the network load and latency associated with blockchain transactions. Finally, we want to conduct extensive scalability tests under real-world scenarios to evaluate system performance with many participants and diverse data streams.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L., Y.F, and K.S.; methodology, Y.L. and Y.F.; software, Y.L.; validation, Y.L.; formal analysis, Y.L. and Y.F.; investigation, Y.L. and Y.F.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.L.; writing—review and editing, Y.F and K.S.; visualization, Y.L.; supervision, Y.F. and K.S.; project administration, Y.L., Y.F., and K.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Meijers, J.; Michalopoulos, P.; Motepalli, S.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, S.; Veneris, A.; Jacobsen, H.A. Blockchain for V2X: Applications and Architectures. IEEE Open J. Veh. Technol. 2022, 3, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeong, D.J.; Velasco-hernandez, G.; Barry, J.; Walsh, J. Sensor and sensor fusion technology in autonomous vehicles: A review. Sensors 2021, 21, 2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ang, L.M.; Seng, K.P.; Ijemaru, G.K.; Zungeru, A.M. Deployment of IoV for Smart Cities: Applications, Architecture, and Challenges. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 6473–6492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Quan, S. A Summary of Security Techniques-Based Blockchain in IoV. Secur. Commun. Networks 2022, 2022, 8689651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammoud, A.; Sami, H.; Mourad, A.; Otrok, H.; Mizouni, R.; Bentahar, J. AI, Blockchain, and Vehicular Edge Computing for Smart and Secure IoV: Challenges and Directions. IEEE Internet Things Mag. 2020, 3, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Xie, S.; Dai, H.; Chen, X.; Wang, H. An Overview of Blockchain Technology: Architecture, Consensus, and Future Trends. In Proceedings of the Proceedings - 2017 IEEE 6th International Congress on Big Data, BigData Congress 2017, Honolulu, HI, USA, 25-30 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yaga, D.; Mell, P.; Roby, N.; Scarfone, K. Blockchain technology overview; No. 8202; National Institute of Standards and Technology,: Gaithersburg, MD, October 2019; pp. 1–57. [Google Scholar]

- Mollah, M.B.; Zhao, J.; Niyato, D.; Guan, Y.L.; Yuen, C.; Sun, S.; Lam, K.Y.; Koh, L.H. Blockchain for the Internet of Vehicles towards Intelligent Transportation Systems: A Survey. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 8, 4157–4185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Github Contributors. Hyperledger Fabric. Available online: https://github.com/hyperledger/fabric (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- Androulaki, E.; Barger, A.; Bortnikov, V.; Muralidharan, S.; Cachin, C.; Christidis, K.; De Caro, A.; Enyeart, D.; Murthy, C.; Ferris, C.; et al. Hyperledger Fabric: A Distributed Operating System for Permissioned Blockchains. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 13th EuroSys Conference, EuroSys 2018, Porto, Portugal, 23-26 April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nasir, Q.; Qasse, I.A.; Abu Talib, M.; Nassif, A.B. Performance analysis of hyperledger fabric platforms. Secur. Commun. Networks 2018, 2018, 3976093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajooh, H.H.; Rashid, M.; Alam, F.; Demidenko, S. Hyperledger fabric blockchain for securing the edge internet of things. Sensors 2021, 21, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alalwany, E.; Mahgoub, I. Security and Trust Management in the Internet of Vehicles (IoV): Challenges and Machine Learning Solutions. Sensors 2024, 24, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karim, S. M.; Habbal, A.; Chaudhry, S. A.; Irshad, A. Architecture, Protocols, and Security in IoV: Taxonomy, Analysis, Challenges, and Solutions. Secur. Commun. Networks, 2022; 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q.; Gao, S.; Zhu, J.; Yuan, C. Permissioned Blockchain-Based Double-Layer Framework for Product Traceability System. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 6209–6225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Tahir, S.; Masood, A.; Tahir, H. Blockchain-Enabled Secure Communication Framework for Enhancing Trust and Access Control in the Internet of Vehicles (IoV). IEEE Access 2024, 12, 110992–111006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndzimakhwe, M.; Telukdarie, A.; Munien, I.; Vermeulen, A.; Chude-Okonkwo, U.K.; Philbin, S.P. A Framework for User-Focused Electronic Health Record System Leveraging Hyperledger Fabric. Information 2023, 14, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Ma, X.; Zhang, S. Performance Analysis of the Raft Consensus Algorithm for Private Blockchains. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern Syst. 2020, 50, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foschini, L.; Gavagna, A.; Martuscelli, G.; Montanari, R. Hyperledger Fabric Blockchain: Chaincode Performance Analysis. In Proceedings of the ICC 2020 - 2020 IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC), Dublin, Germany, 7-11 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Stephen, R.; Alex, A. A Review on BlockChain Security. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 396, 012030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muqorobin, M.; Rozaq Rais, N.A. Comparison of PHP Programming Language with Codeigniter Framework in Project CRUD. Int. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2022, 3, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abourezq, M.; Idrissi, A. Database-as-a-Service for Big Data: An Overview. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2016, 7, 157–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).