Submitted:

03 June 2025

Posted:

03 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Section II: This section delves into the various studies and works that have been carried out previously in this field, providing an overview of existing knowledge and identifying gaps that this research aims to fill.

- Section III: Here, we discuss the existing system in detail, highlighting its strengths and pointing out its limitations. This analysis serves as the basis for understanding the need for our proposed improvements.

- Section IV: In this section, we present a complete description of the system. We describe its structure, functions, and key components, allowing the reader to understand the full picture of the theme.

- Section V: This section is dedicated to the proposed scenario. We present our proposed solutions, modifications or improvements to the existing system, based on the limitations identified in Section III.

- Section VI: We present the results obtained from the implementation of the proposed scenario in Section V. This includes any data, observations or conclusions drawn from the application of our proposed scenario.

- Section VII: In the final section, we summarize the key findings of our research and discuss possible future directions. We propose new avenues of research that could further expand our findings and contribute to the field.

2. Presents a Review of Related Works

3. Explains the Existing System, Highlighting Its Advantages and Limitations

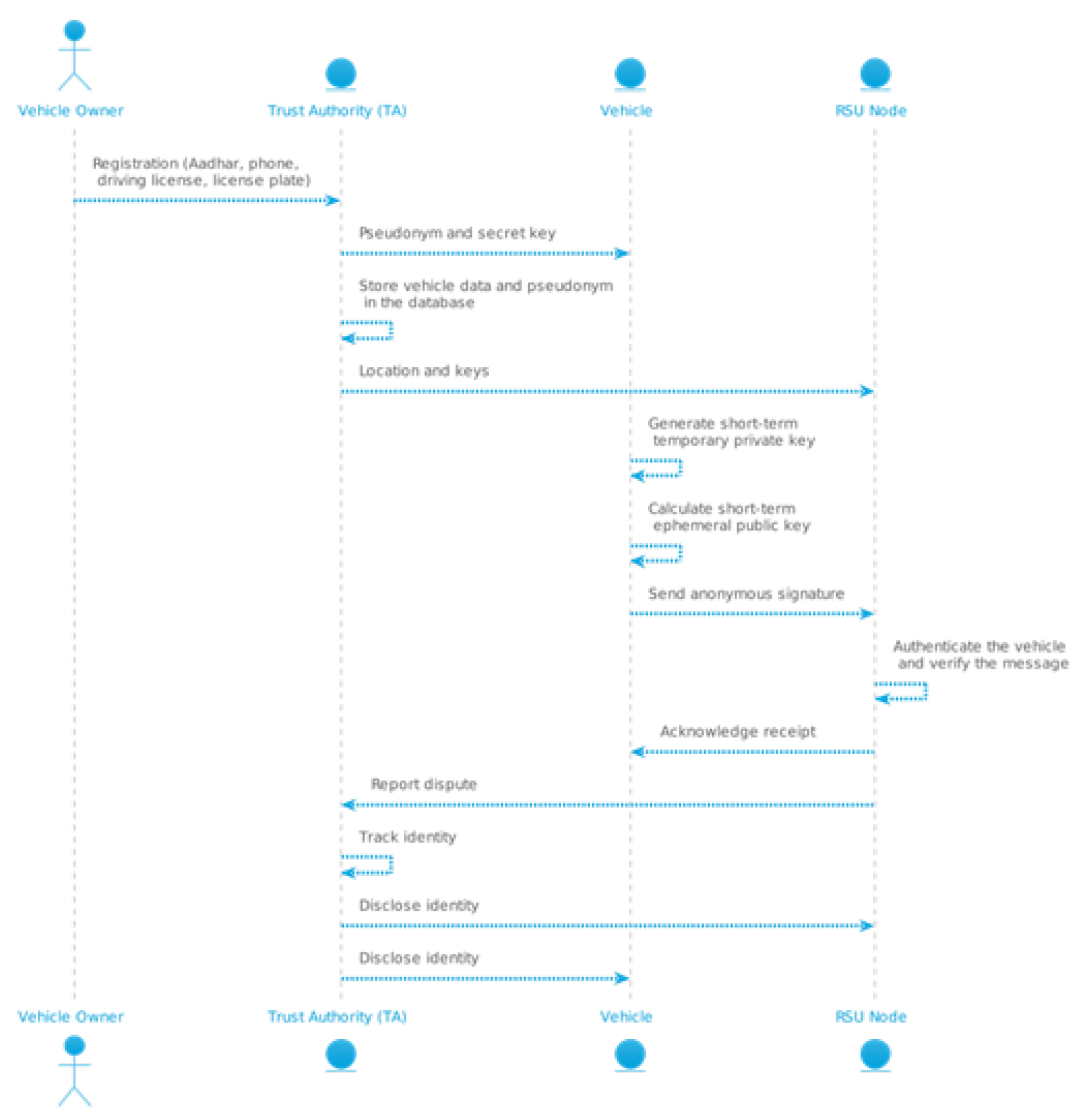

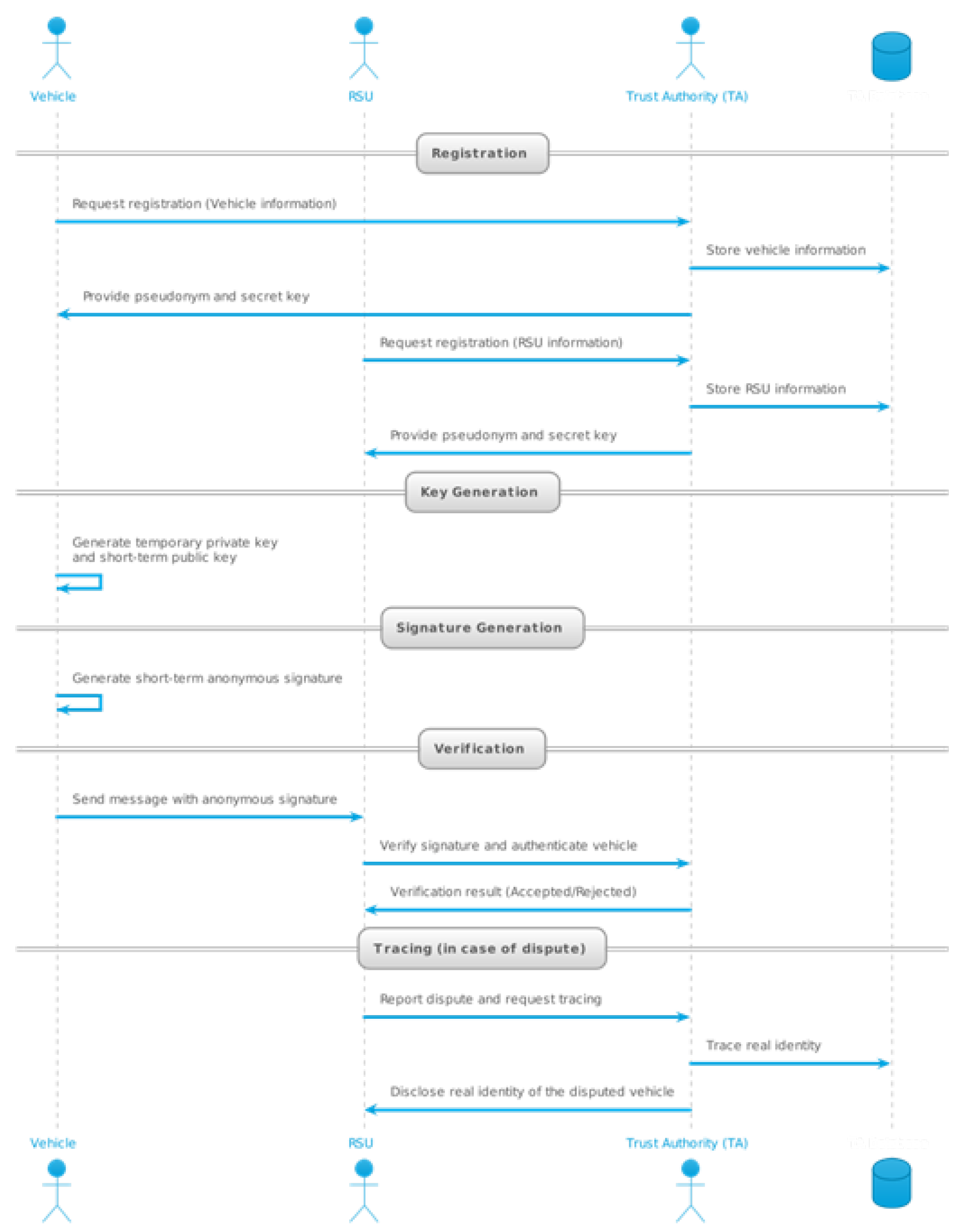

- Registration: Prior to the implementation of the network, vehicles and RSU must be registered with the AT. Vehicle owners submit their Aadhar card, mobile phone number, driver’s license, registration number and other details to the TA.

- Key Generation: Upon entering the range of an RSU, the vehicle selects a random number as a short-term, temporary private key and uses it to compute a short-term, ephemeral public key.

- Signature Creation: To verify and maintain the integrity of the message, the vehicle creates a short-term anonymous signature using the short-term anonymous key and sends it to the RSU. If not, it discards the message and informs the TA for further action.

- Tracking: In the event of a dispute between a vehicle and an RSU, the TA tracks the true identity in its database and reveals it to all RSUs and vehicles, thus nullifying the privacy of malicious users, whether they are vehicles or RSUs, to avoid further damage (Table 1).

4. Provides an Overview of the System.

4.1. System Model

- OBU: Vehicles incorporate an OBU that functions as a transceiver, facilitating communication with other vehicles’ OBUs and RSUs [35]. Each OBU contains a Tamper-Proof Device (TPD) to house sensitive data such as authentication keys from the TA, alongside sensors like the GPS for location [36], and an Event Data Recorder (EDR) to log vehicle accident data [37].

- RSU: RSUs, as stationary units, are situated alongside roads or at specific points such as crossroads or parking areas [38]. They perform diverse functions, from vehicle authentication and Teegraph message storage to maintaining a confidential ledger with vehicle details and its verification status [39]. They also communicate with proximate RSUs and vehicles within their range and report malevolent activities to the TA [40].

4.2. Bilinear Pairing

4.3. Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC)

4.4. MinBFT

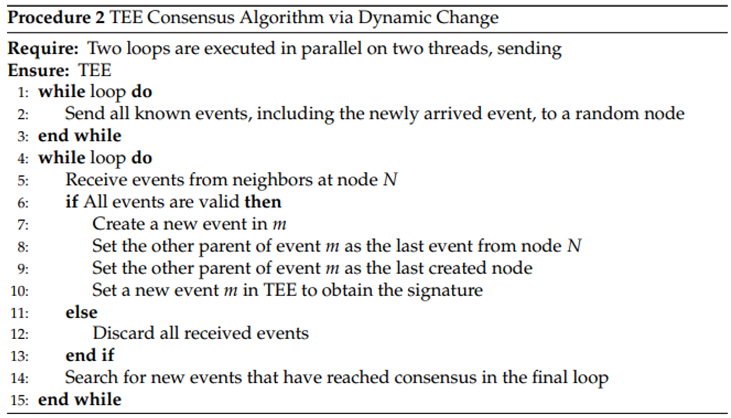

4.5. The VANET-Teegraph Algorithm

- Registration: Vehicles and RSUs must be registered with a Trusted Authority (TA) prior to network deployment. The TA generates pseudonyms and secret keys for each user and stores them in the vehicle’s device and its database.

- Key Generation: Every time a vehicle enters the range of an RSU, it chooses a random number as a temporary private key and uses it to calculate a short-term public key.

- Signature Generation: The vehicle generates a short-term anonymous signature using the short-term anonymous key and sends it to the RSU for verification and maintenance of message integrity.

- Verification: The RSU authenticates the vehicle and verifies the message. If everything is correct, it accepts the message and sends an acknowledgment to the vehicle; otherwise, it discards the message and reports it to the TA.

- Tracking: In case of disputes between RSUs or vehicles, TA tracks the true identity from its database and reveals it to all RSUs and vehicles, thus denying privacy to malicious users.

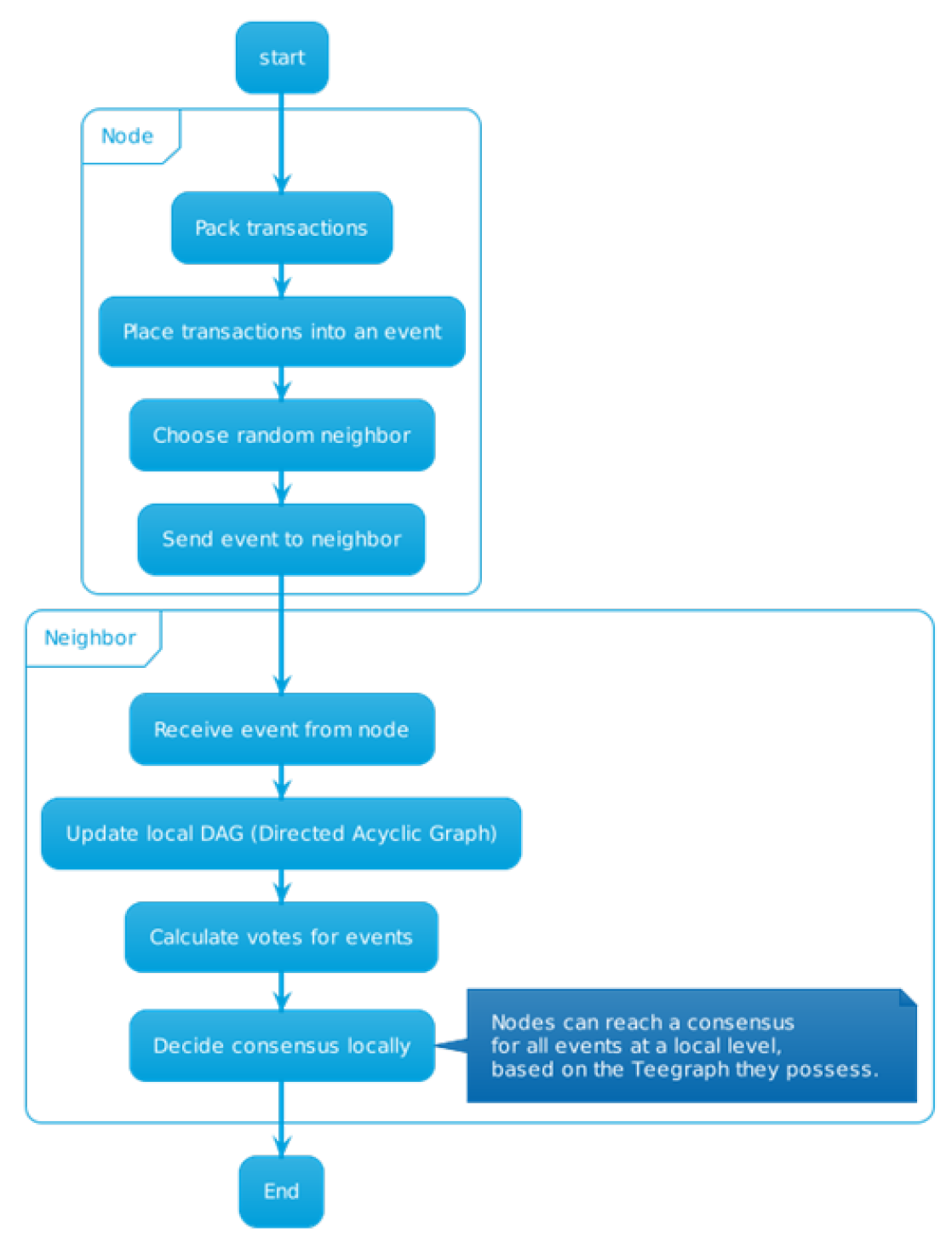

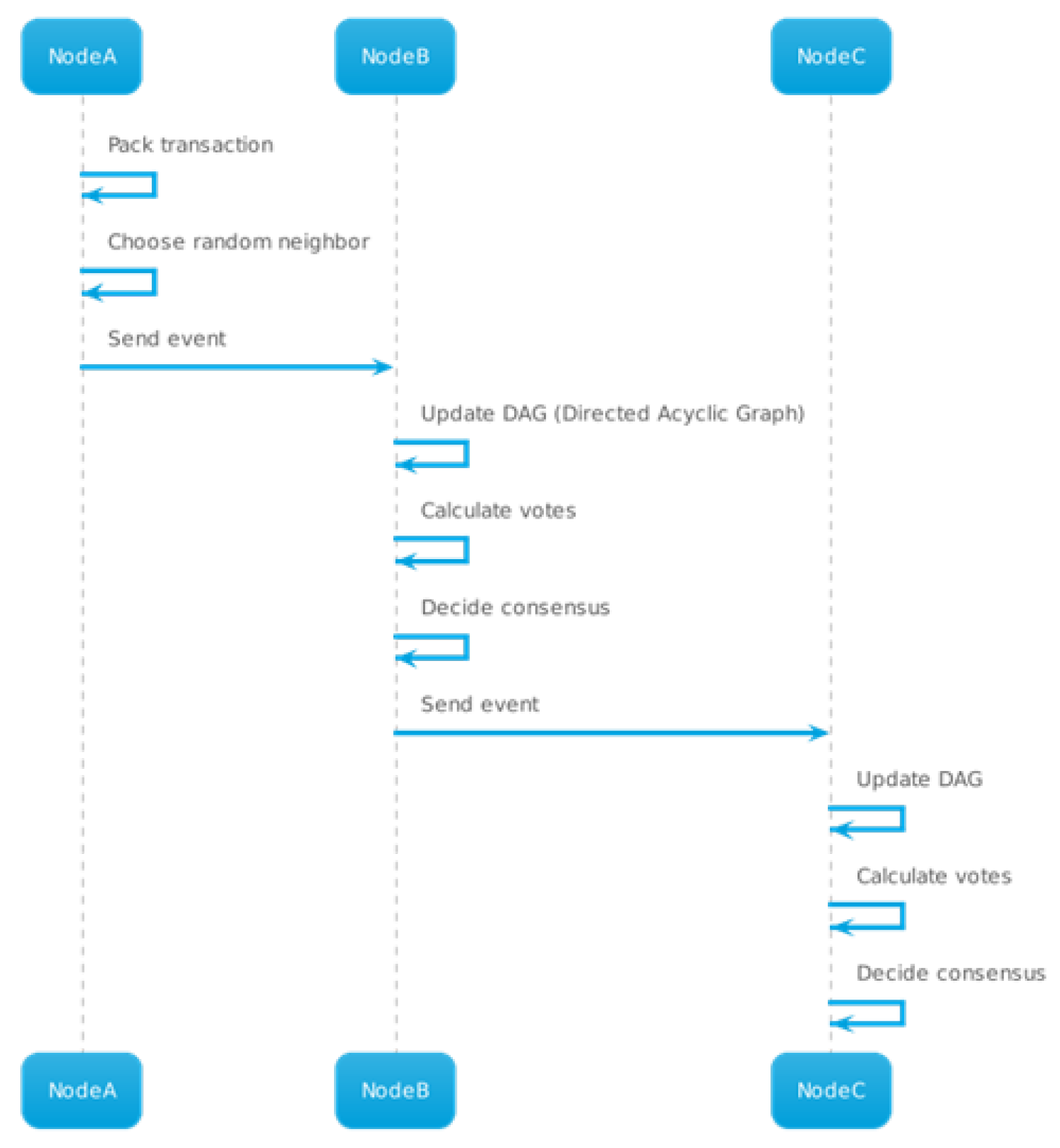

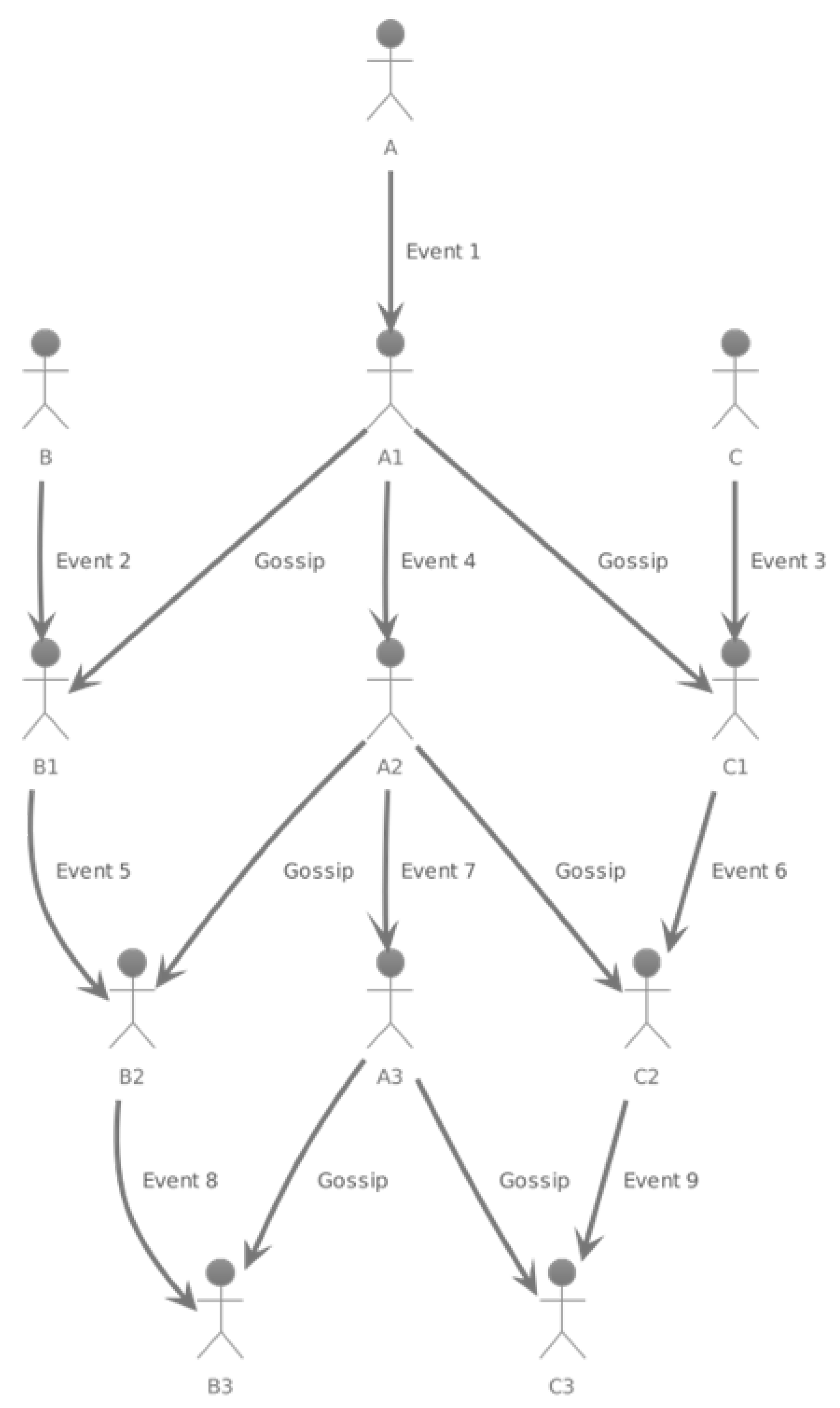

- Communication using Teegraph and Hashgraph: The system uses Teegraph technology to generate a Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) locally on each node, allowing local consensus on events in the network. In addition, the algorithm integrates the Hashgraph data structure to improve the efficiency and security of communication and storage of information on the network.

4.6. Design by VANET-Teegraph

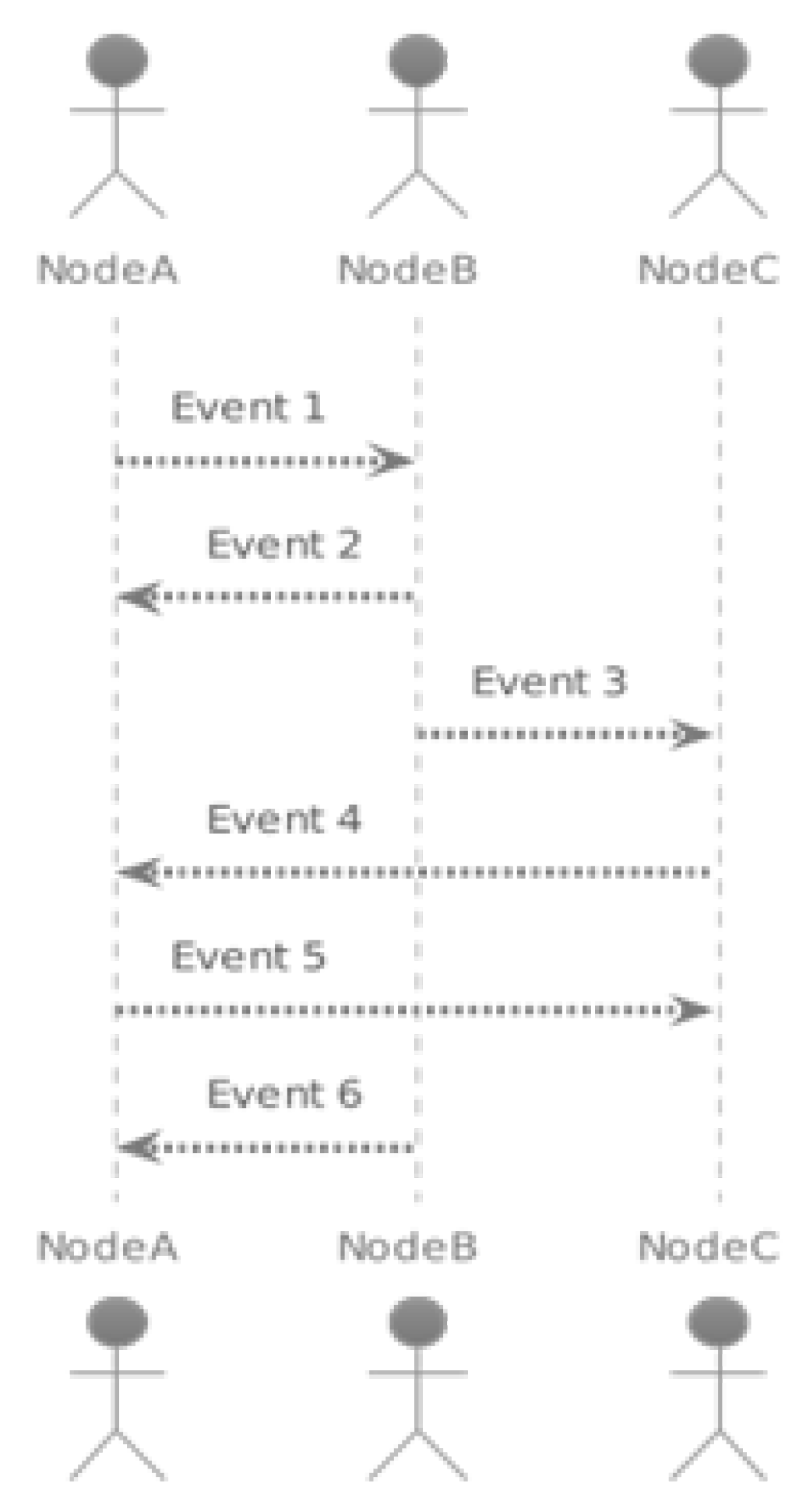

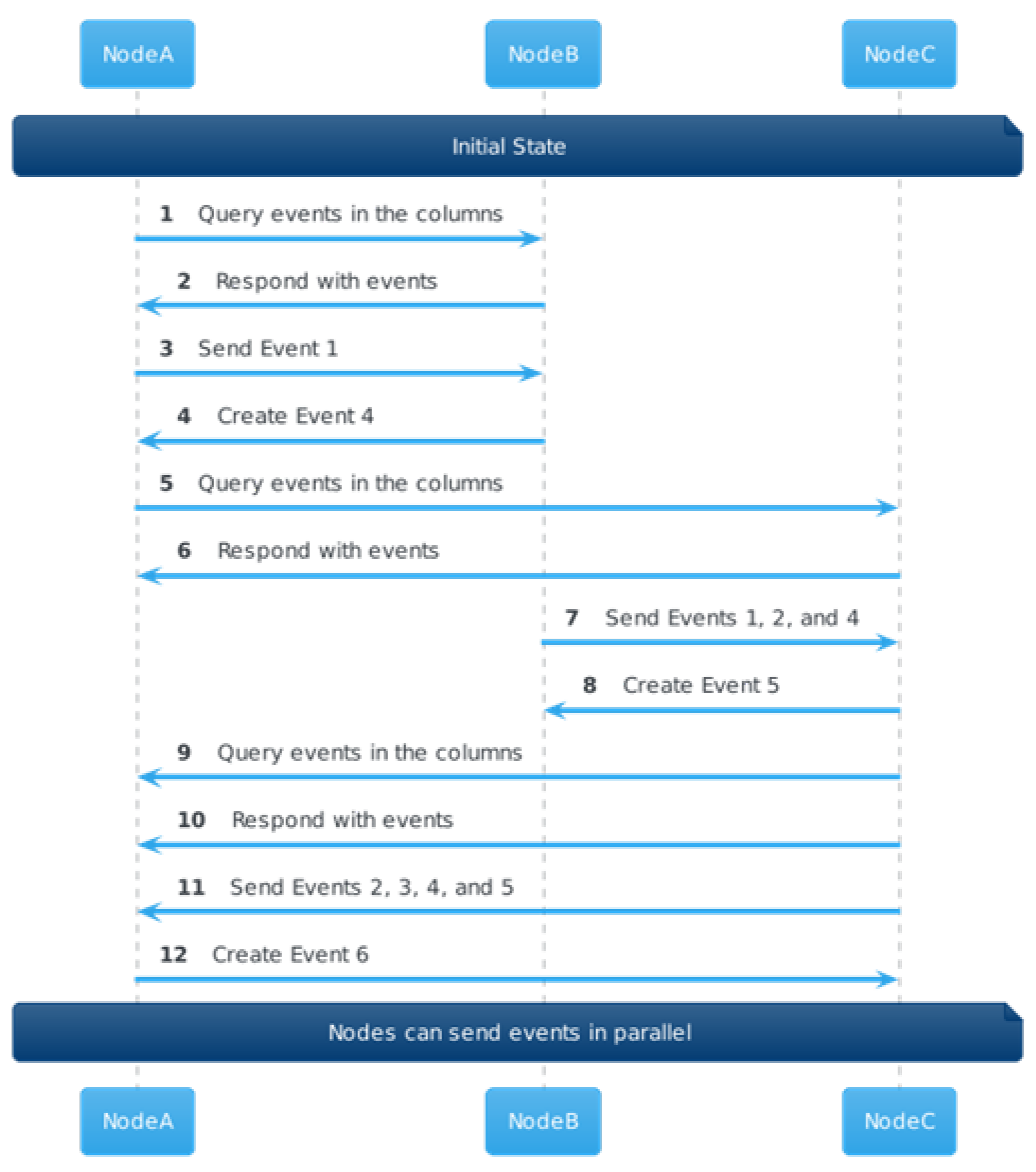

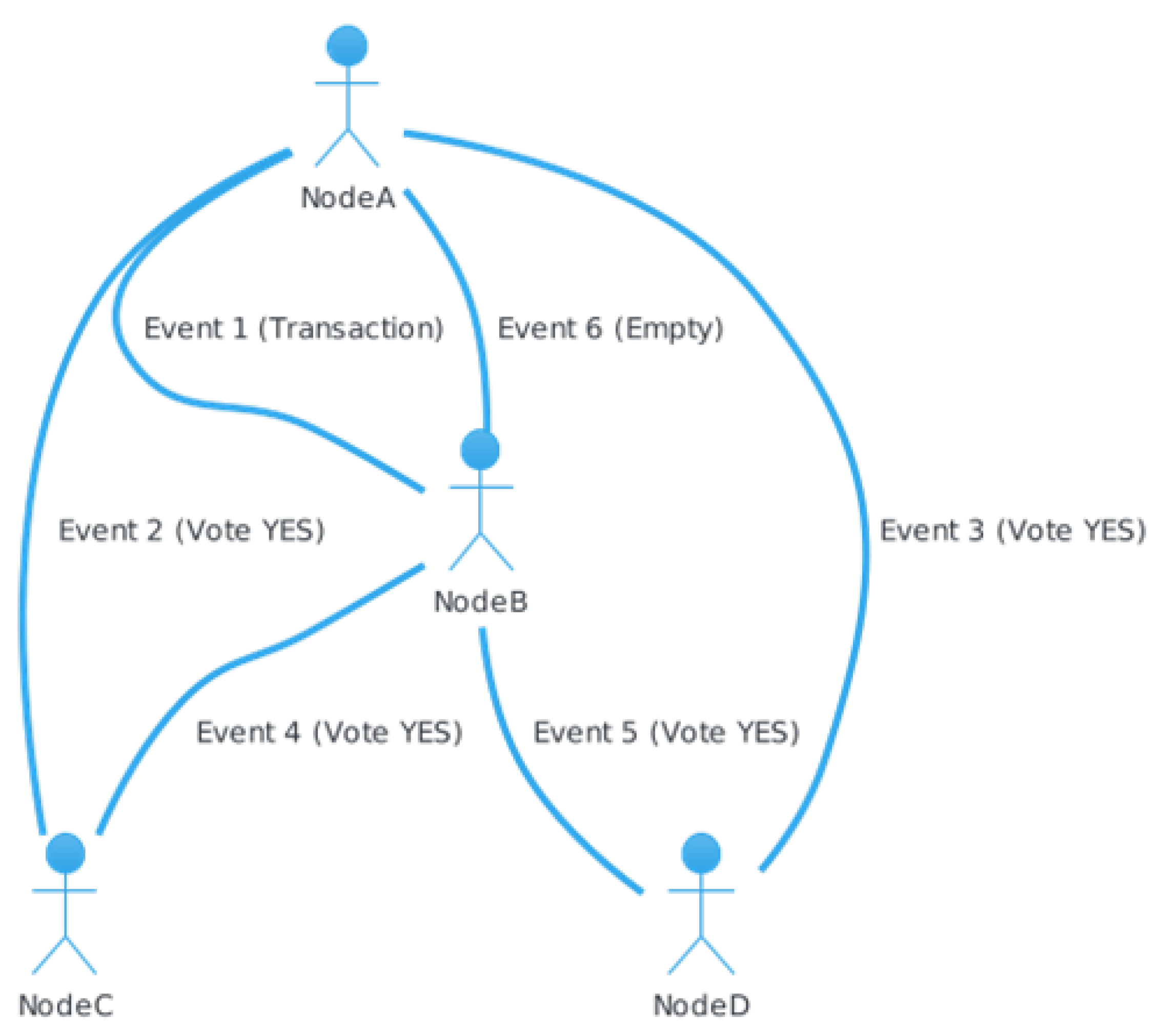

4.6.1. How the Teegraph Is Generated

- Initial State: Each node has a single event in its corresponding column, while the other columns are empty.

- Step 1 (Tokens from Node A to Node B): Node A randomly selects a neighbor (Node B) to send events to. Node A sends all the events it has and does not have to node B. Node B creates a new event and sets its parents accordingly.

- Step 2 (Tokens from Node B to Node C): Node B randomly selects a neighbor (Node C) to send events to. The process is similar to Step 1, with node B sending events to node C and node C creating a new event.

- Step 3 (Tokens from node C to A): node C randomly selects a neighbor (node A) to send events to. Node C sends events to node A, and node A creates a new event with the parents set appropriately.

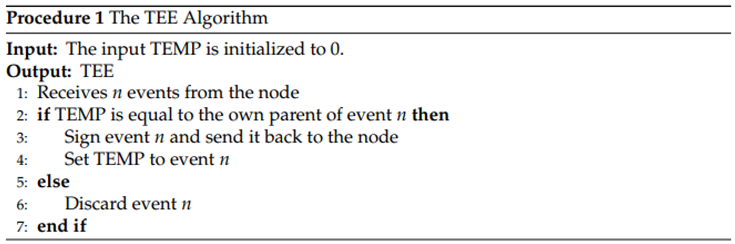

4.6.2. The Single Use Mechanism

- The node sends event n to the TEE.

- The TEE compares the hash of event n’s own parent with the hash of event stored in its memory.

- If they are equal, the TEE signs event n and returns it to the node.

- The TEE stores the hash of event n, replacing the hash of event in its memory.

- If in step 3 they are not equal, the TEE discards event n and halts the process.

|

|

- Security: In Teegraph, nodes cannot produce forks. Even when two conflicting events arise, they maintain a parent-child relationship, ensuring only the parent event can achieve consensus, given it has over half of the affirmative votes. Assumptions include: less than 50% of nodes act maliciously (Teegraph can bear over 1/3 Byzantine nodes due to TEE’s preventive measures), and the security of encryption methods and hash functions.

- Liveness: Teegraph ensures any valid event from an honest node will achieve consensus. An event requires votes from over half of the nodes to gain consensus. Leveraging the gossip protocol, events spread quickly, generally taking O(log N) rounds to reach all nodes, with N being the total nodes.

- Effectiveness: Teegraph’s performance covers aspects like throughput, latency, scalability, and resource usage. Scalability is notably strong, thanks to the gossip protocol, allowing adaptability in extensive distributed networks.

- Decentralization: Every node in Teegraph has equal transactional responsibility, promoting fair distribution of accounting rights. However, due to reliance on TEEs, there’s a certain centralization, trading off for enhanced performance and security.

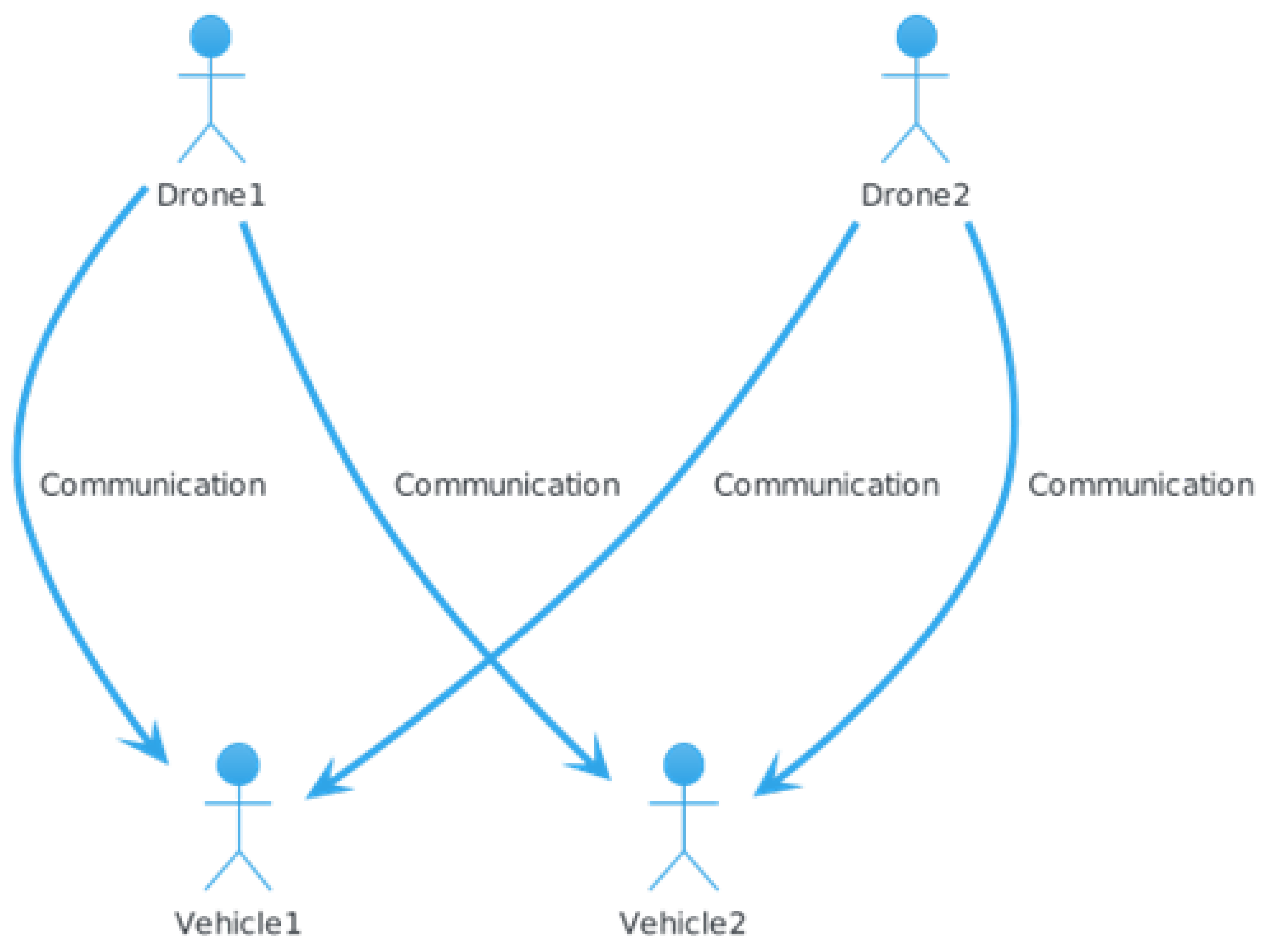

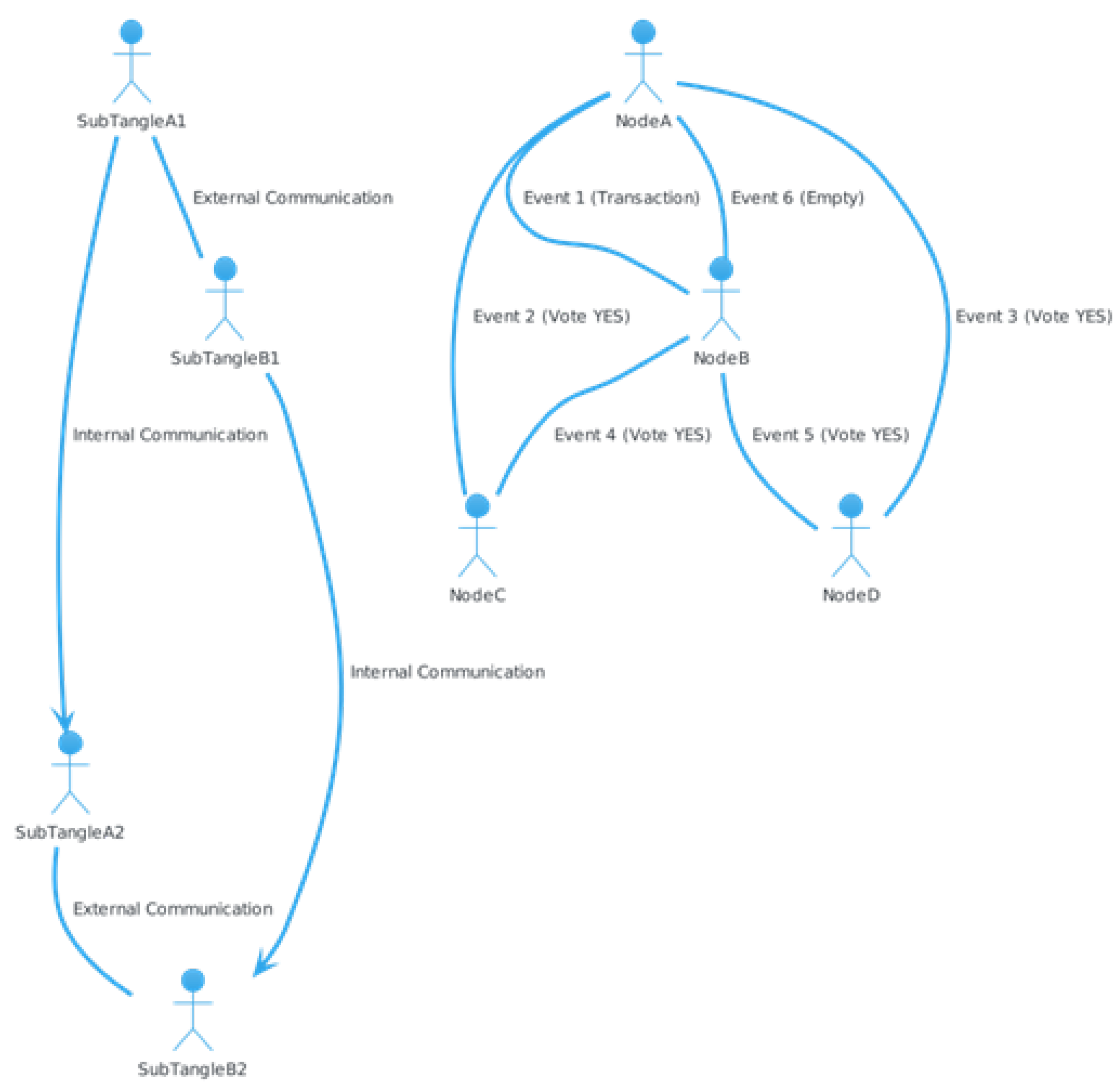

4.6.3. Integration for VANET Environment (Vehicular Ad-Hoc Network)

|

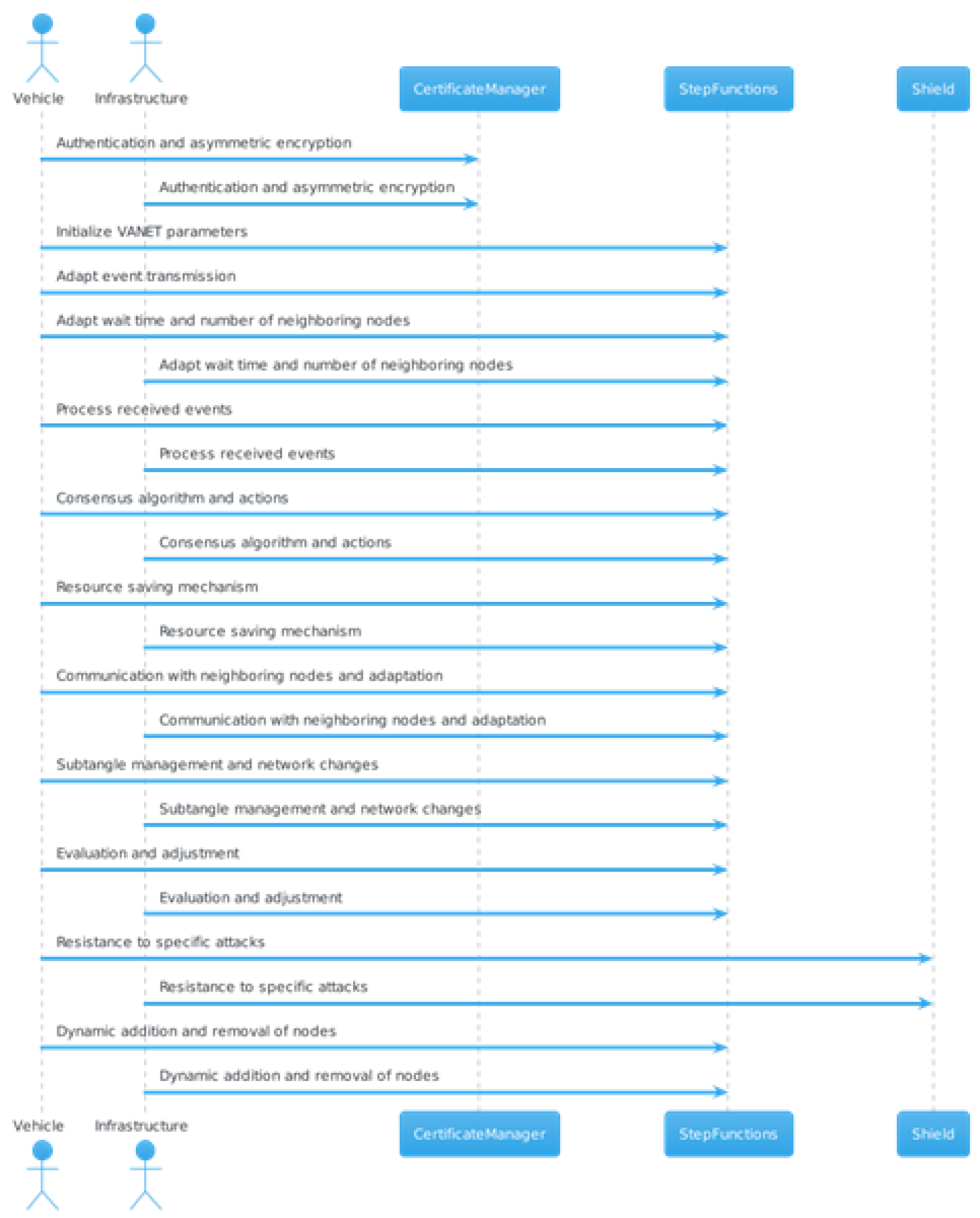

5. Describe the Proposed Scenario

6. Presents the Results for the Proposed Scenario

6.1. Simulation: Calculation of the Probability of Dropout (POL)

- Communication between vehicles and Road Units (RSUs): Teegraph can help optimize the way vehicles and RSUs share information with each other. By employing the Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) structure and the "gossip about gossip" approach, efficiency in communication and decision making within the network can be improved.

- Rekeying and Key Updates: Teegraph can assist in the rekeying process in the Logical Key Hierarchy (LKH) by facilitating efficient key updating and distribution across the network. By using the local consensus approach, nodes can make faster decisions on whether or not to accept an updated key.

- Reduced key transfer time: Under high traffic conditions, Teegraph can help reduce the time it takes to transfer keys between nodes on the network. This is achieved through more efficient communication and consensus-based decision making.

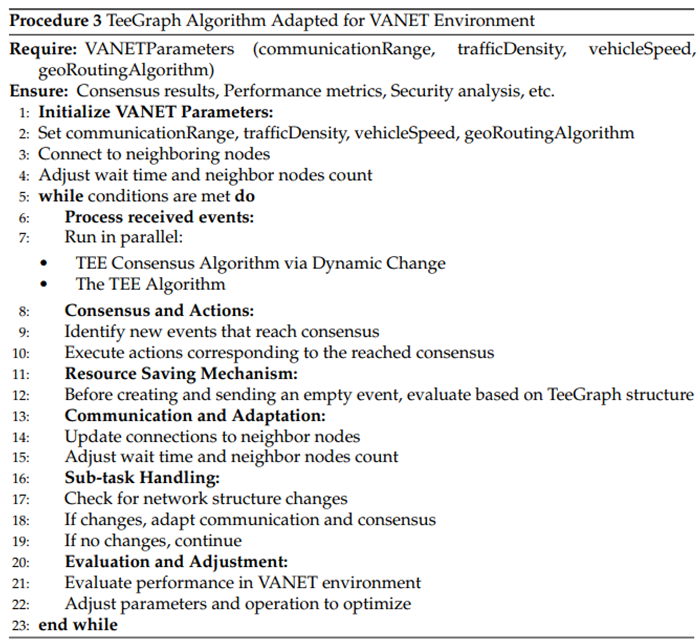

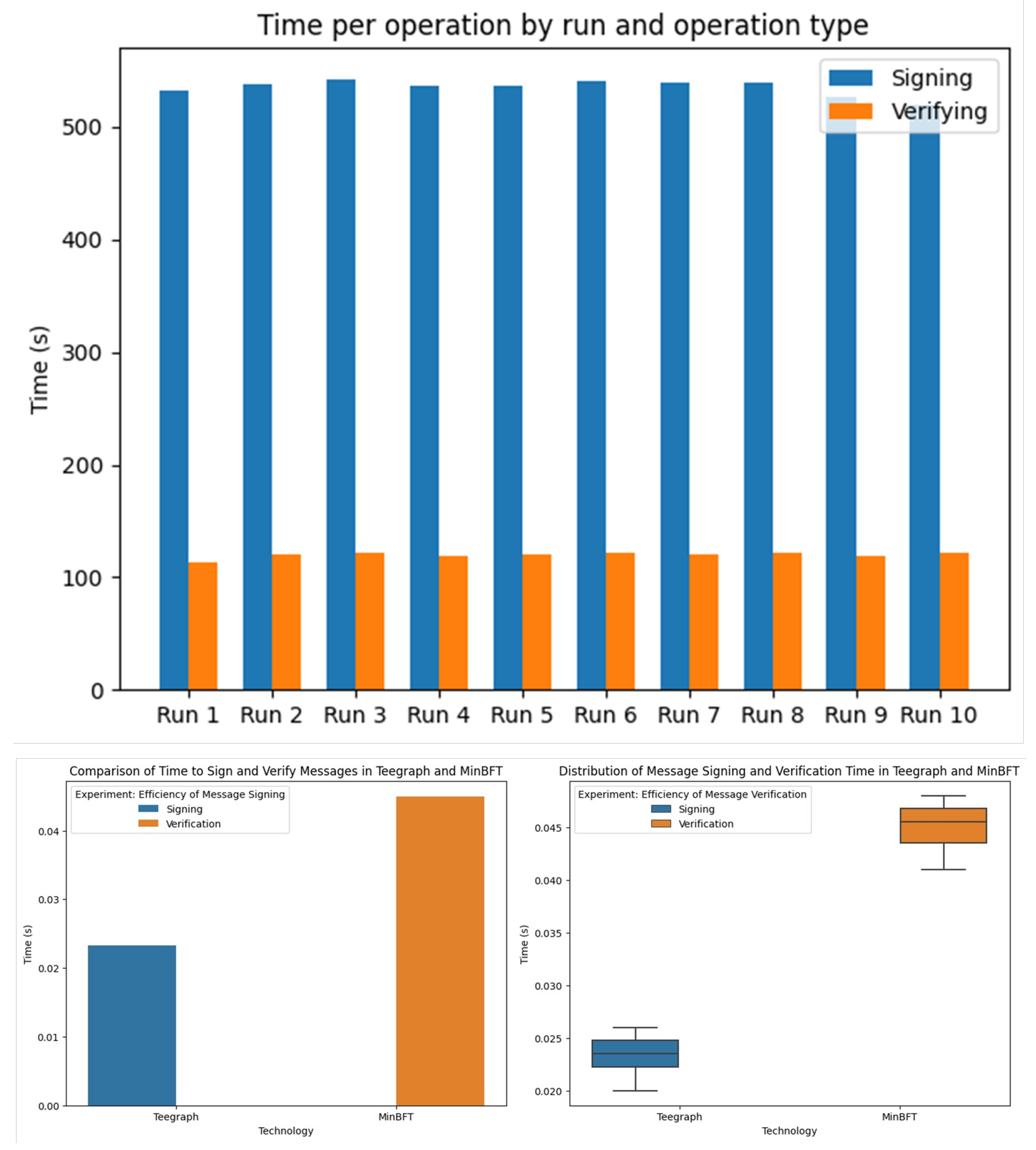

6.2. Experiments for TEE

6.2.1. Efficiency of Message Signing

6.2.2. Efficiency of Message Verification

6.2.3. Results of Previous Experiments

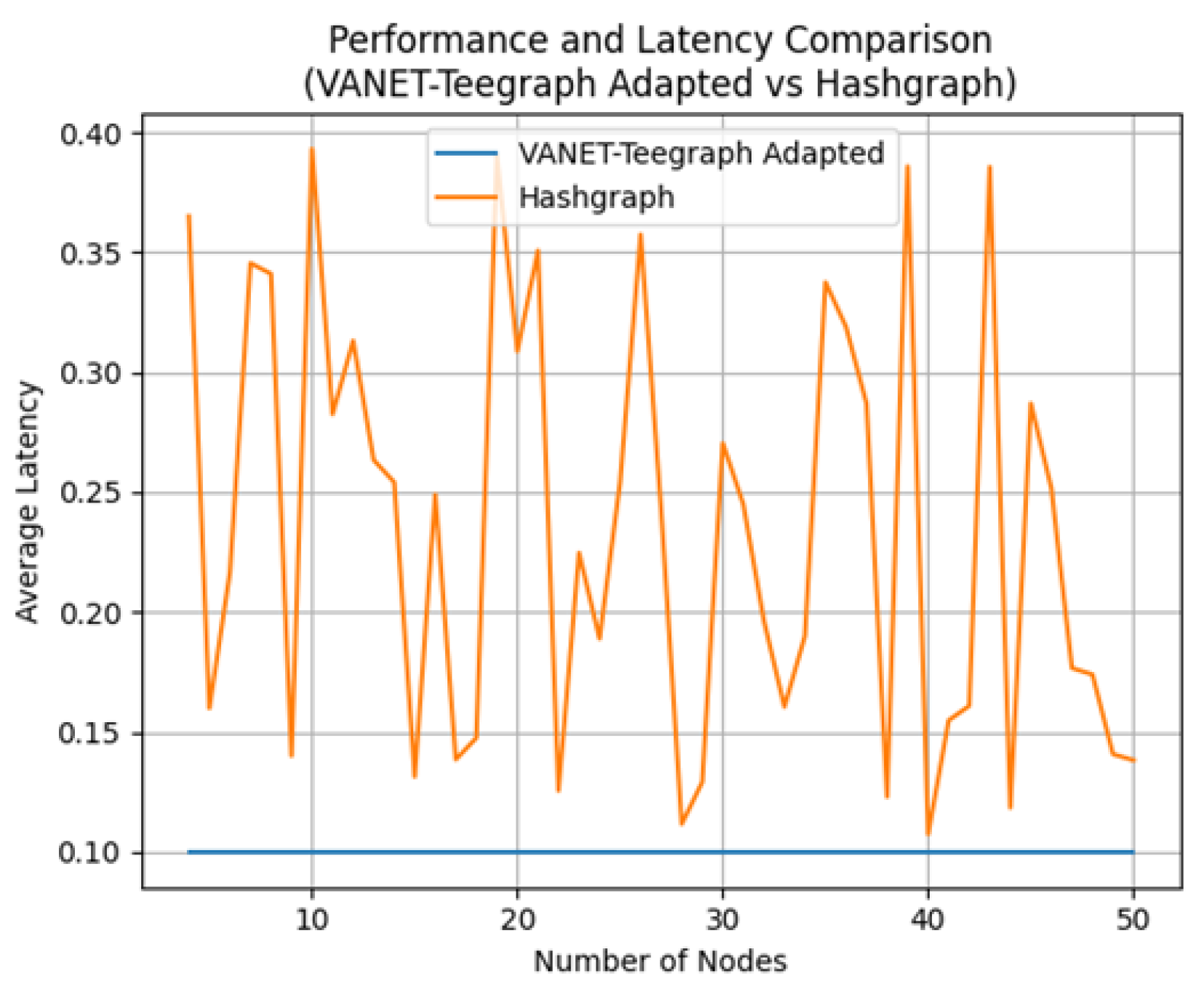

6.3. Visualization: Experiments for Performance and Latency Assessment

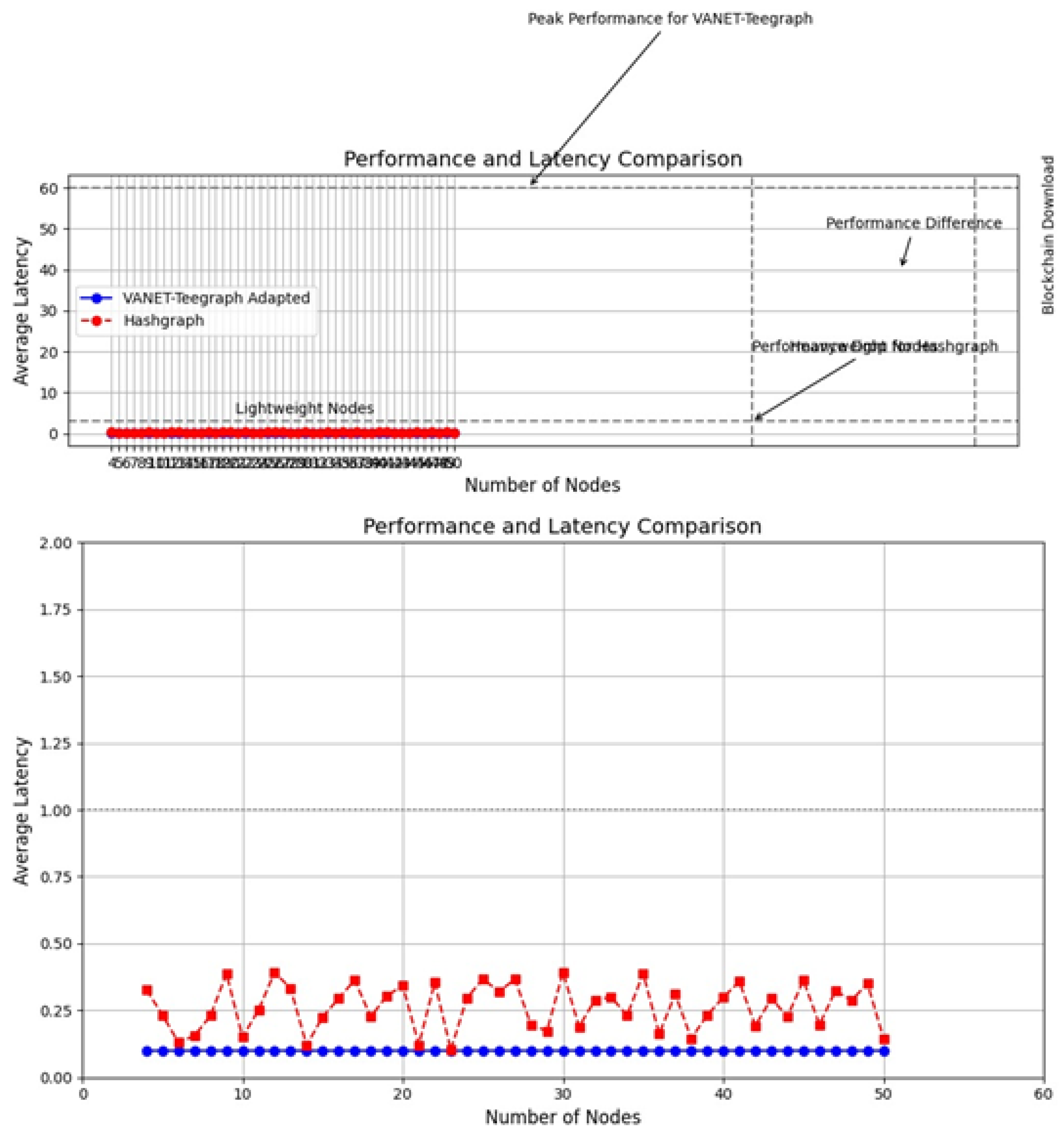

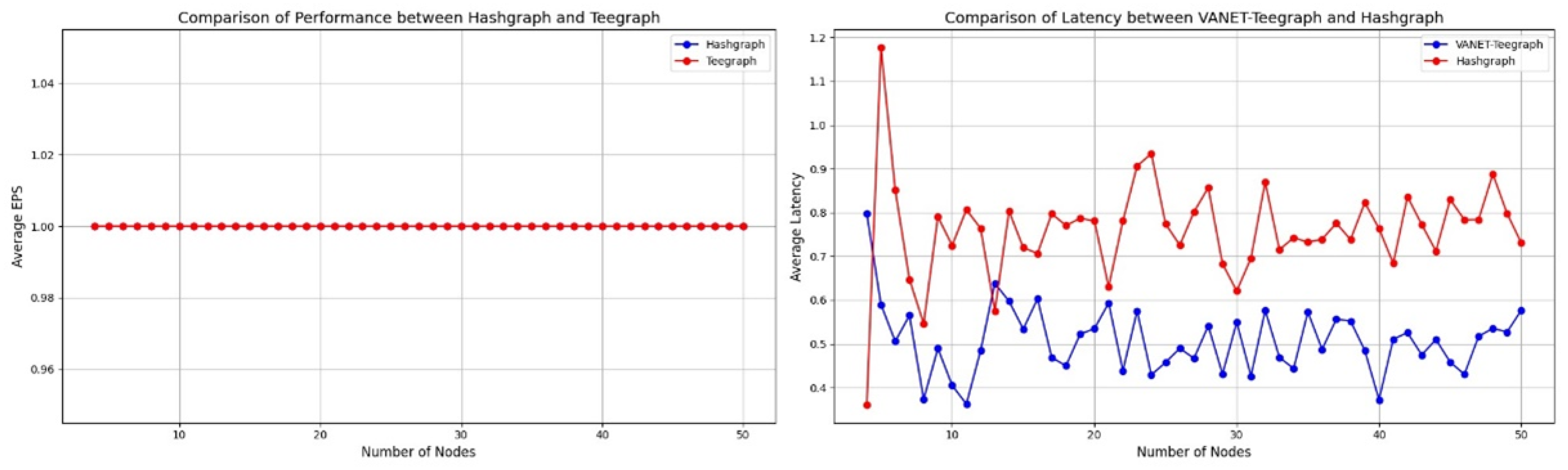

6.3.1. Scenario 1: Comparison of Throughput and Latency Between Teegraph and Hashgraph with Different Numbers of Nodes

6.3.2. Scenario 2: Scalability Comparison Between Adapted VANET-Teegraph and Hashgraph Based on Throughput and Latency

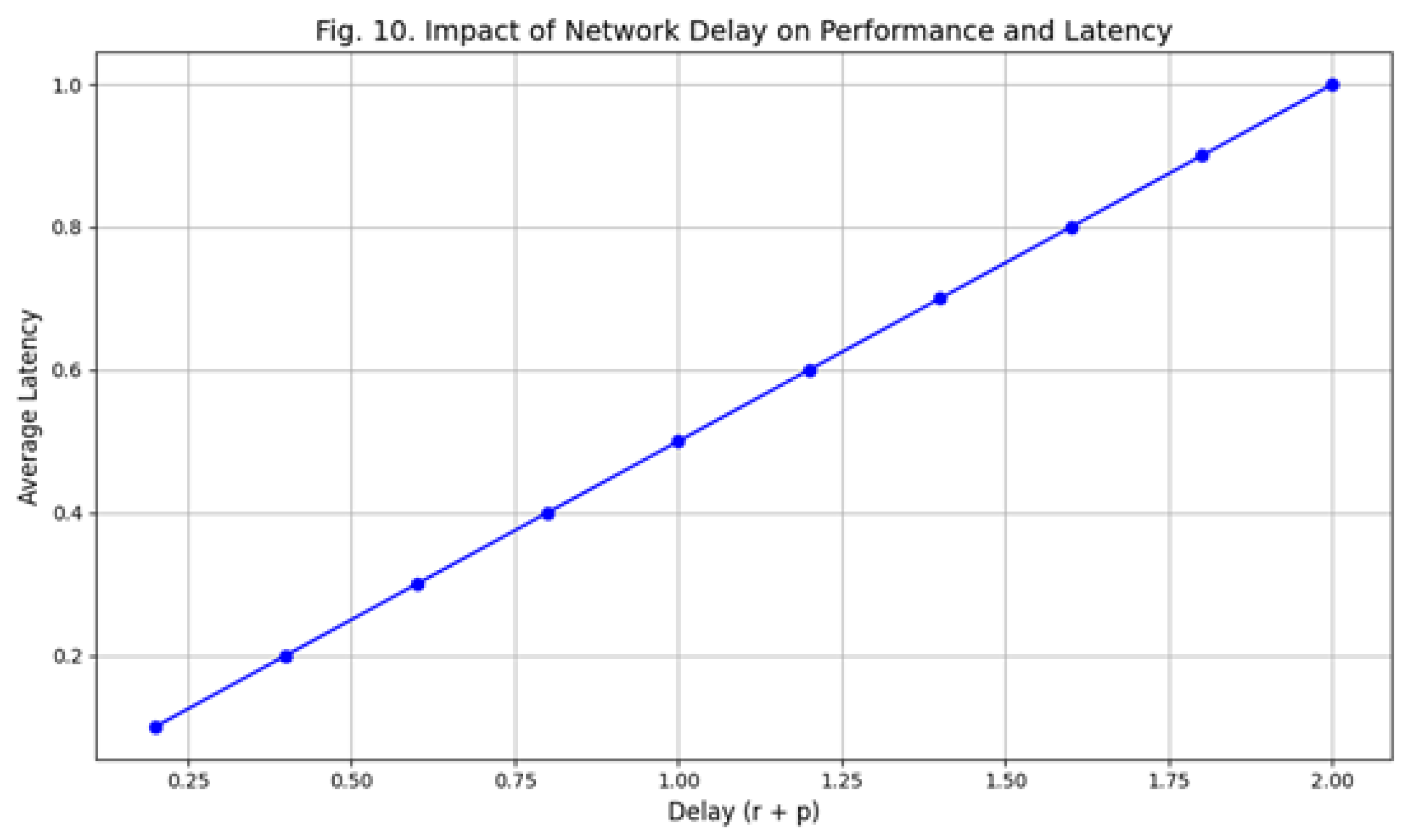

6.3.3. Scenario 3: Comparison of Throughput and Latency Between Teegraph and Hashgraph with Different Network Latencies

6.3.4. Scenario 4: Performance and Latency Comparison Between Adapted VANET-Teegraph and Hashgraph Applying the “Fail-Skip” Strategy

7. The Conclusions and Future Lines of Research are Detailed.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roberts, J.; Clark, M. Evolution of Mobile Ad-Hoc Networks to Vehicular Networks. J. Netw. Syst. 2020, 13, 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, B.; Patel, R. VANETs: The On-Board Units and their Role in Vehicle-to-Vehicle Communication. Transp. Syst. Netw. 2019, 18, 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, L.; Johansson, E. Blockchain and IoT: Revolutionizing the Future of Autonomous Vehicles. Tech Auto Rev. 2021, 7, 12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor, N.; Singh, L. Decentralized Vehicular Networks: Prospects and Challenges. J. Next-Gen Transp. 2022, 5, 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Doe, J.; Smith, A.; Lee, Y. Implementing Blockchain-based Key Management Systems in VANETs. Adv. Veh. Netw. 2020, 16, 78–84. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A.; Harris, J. Teegraph Algorithm in VANETs: A Hashgraph-Based Perspective. J. Netw. Solut. 2021, 11, 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, L.; Meyer, E. Vehicular Privacy in the Age of Connectivity. Int. J. Cybersecur. 2020, 8, 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Green, T.; Adams, R. Role of Trust Authorities in Vehicular Networks. Veh. Commun. Syst. 2019, 7, 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P.; Rao, S. 4G and 5G in Vehicular Networks: A Study. Telecommun. Adv. 2020, 5, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.; Park, J. Effective Traffic Management in Modern Vehicular Networks. Transp. Tech J. 2019, 9, 46–54. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, H.; Turner, M. Ultra-Reliable Low-Latency Networks for Vehicles. Automob. Netw. 2018, 3, 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.; Kim, H.; Jung, W. Exploring MEC in Autonomous Vehicular Communication. J. Veh. Eng. 2020, 6, 28–37. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Li, Y. Challenges in Developing MEC-based Systems for Vehicles. Netw. Syst. Rev. 2021, 14, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.; Doe, R. Teechain: A TEE-based Off-chain Payment Protocol for Efficient and Scalable Blockchain Transfers. J. Blockchain Technol. 2022, 45, 130–140. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, A.; Johnson, P. Teegraph: Efficient Consensus using Gossip Protocols and TEE Mechanisms. Adv. Consens. Algorithms 2021, 32, 88–97. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Da Xu, L.; Zhao, S. The internet of things: A survey. Inf. Syst. Front. 2018, 20, 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.; Brown, A. VANET Security Alerts: Methods and Challenges. J. Veh. Commun. 2019, 5, 34–45. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, R.; Martin, C. Pseudonym Methods for Vehicle Privacy in VANETs: A Comprehensive Study. Trans. Veh. Technol. 2020, 60, 102–114. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, T.; Wang, X. (2020). Blockchain-based Solutions for Message Security in VANETs. Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Vehicle Technology, 312-319.

- Kumar, N.; Patel, S. Trusted Execution Environments in VANET: Prospects and Challenges. J. Netw. Secur. 2021, 10, 50–60. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.; Kim, J.; Park, K. (2019). Teechain: Leveraging TEEs for Scalable and Efficient Off-chain Cryptocurrency Payments. Proceedings of the ACM Symposium on Blockchain Technology, 20-31.

- Chen, L.; Wu, Q.; Tan, Y. Consensus Algorithms in IoT: Challenges and Solutions with DAG and TEE. J. IoT Res. 2020, 7, 78–90. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.; Thompson, R. Enhancing Vehicular Network Security with Elliptic Curve Cryptography. J. Veh. Commun. 2020, 15, 235–246. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, M.; Lee, H. The Promise of Hashgraph: Data Storage and Network Efficiency. Netw. Solut. J. 2019, 22, 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, L. Tracking Malicious Vehicles in Vehicular Networks. J. Netw. Secur. 2020, 14, 123–134. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Kumar, P. Privacy Preservation in Vehicular Networks: Pseudonym Strategies and Methods. Veh. Priv. J. 2021, 7, 501–514. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, R.; Malik, A. Challenges in Vehicular Networks: Authentication and Wait Times. J. Veh. Technol. 2020, 20, 765–776. [Google Scholar]

- D’Souza, C.; Fernandes, L. Emergency Communications in High-speed Vehicular Scenarios. Veh. Commun. Rev. 2019, 11, 348–359. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, V.; Patel, D. Computational Demands in RSU Blockchain Operations. J. Blockchain Veh. Netw. 2021, 3, 158–170. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Liu, S.; Yang, T. Exploring TeeGraph and Hashgraph in Vehicular Communication Systems. Adv. Netw. Stud. 2021, 26, 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, R.; Rani, S. VANET-TeeGraph Algorithm: Pros and Cons. Veh. Syst. Res. 2020, 24, 810–822. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, Y. Innovations in Vehicular Network Solutions: A Comprehensive Review. J. Veh. Syst. 2019, 18, 900–912. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, L.; Garcia, N. Introduction to Vehicle-to-Vehicle Communication in Modern VANETs. J. Veh. Netw. 2018, 10, 120–130. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, R.; Smith, J. Components of Vehicular Ad-hoc Networks. Netw. Syst. J. 2017, 15, 56–65. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, P.; Lee, Y. On-Board Units in Vehicular Networks: Functions and Features. Veh. Technol. Rev. 2019, 12, 75–85. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, M.; Yang, T. GPS and Event Data Recorders in Modern Vehicles. Automot. Technol. J. 2020, 14, 46–53. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, J.; Iyer, R. Event Data Recorders in Accidents: Importance and Analysis. Traffic Saf. J. 2016, 8, 50–59. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; Park, S. Role and Functionality of Road Side Units in VANETs. J. Netw. Syst. 2015, 9, 34–42. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed, F.; Kaur, P. The Role of Teegraph in Road Side Units. Veh. Syst. Teegraph 2018, 13, 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, D.; Shah, R. Malicious Activities Detection in VANETs. J. Veh. Secur. 2017, 16, 90–100. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.; Wang, F. Trust Authority in Vehicular Networks: Ensuring Security. Netw. Secur. Trust Syst. 2019, 11, 66–75. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, X. Database Management in Trust Authorities. VANET Database J. 2016, 10, 130–139. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, H.; Tran, Q. Advanced Algorithms in Vehicular Networks. Veh. Netw. Stud. 2020, 17, 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.; Gupta, M. Teegraph Technology in Vehicular Ad-Hoc Networks. Adv. Netw. Solut. 2018, 19, 110–120. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez, L.; Romero, S. Communication Protocols in VANETs. J. Veh. Commun. 2021, 20, 80–89. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, M.; Davis, A. Bilinear Pairing in VANETs: An Overview. J. Veh. Netw. 2019, 11, 145–152. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, N.; Morales, L. Security Implications of Bilinear Pairing in VANET-Teegraph Systems. Veh. Secur. Rev. 2020, 17, 34–40. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, P.; Zhang, Y. Preserving Privacy in VANETs through Pseudonyms. Automot. Priv. J. 2018, 6, 78–85. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Wang, F. Mathematical Groups in Bilinear Pairing for Enhanced Data Transmission. Adv. Netw. Solut. 2017, 13, 120–126. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez, L.; Gomez, J. Bilinear Pairing in Cryptography and Network Security. Netw. Secur. Cryptogr. 2015, 9, 45–51. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, R.; Oliver, P. Enhancing Vehicle-MSW Communications with ECC. J. Veh. Commun. 2020, 14, 75–82. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, S.; Kaur, I. Digital Signature Generation in VANETs using ECC. Automot. Secur. Insights 2018, 8, 101–109. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.; Park, H. Synergizing ECC with Teegraph and Hashgraph for Secure VANETs. J. Adv. Transp. Netw. 2019, 17, 34–42. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, L.; Vargas, R. Mathematical Properties of Elliptic Curves in Cryptography. Adv. Cryptogr. Res. 2017, 13, 66–74. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.; Le, H. Key Pair Generation with ECC in Modern Networks. Netw. Innov. 2015, 11, 89–95. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, X.; Zhao, L. Scalar Multiplication in ECC: A Detailed Study. J. Netw. Secur. 2016, 10, 213–220. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, A.; Rodriguez, J. The Role of Modern Technologies in the Evolution of VANETs. Veh. Netw. Dev. 2021, 19, 7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, A.; Fernandez, M. Introduction to MinBFT: A New Paradigm in BFT Protocols. J. Netw. Syst. 2019, 14, 58–64. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, R.; Patel, V. On the Implementation of Efficient Byzantine Fault-Tolerance. Adv. Syst. Res. 2020, 25, 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, H.; Clark, J. The Role of Intel SGX in MinBFT’s Efficient Architecture. Mod. Comput. Solut. 2018, 11, 120–127. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, K.; Tan, L. Secure Hardware in Modern System Architectures: TEEs and Beyond. J. Comput. Secur. 2017, 9, 89–95. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, S.; Gomez, E. Byzantine Consensus in Modern Networks: MinBFT vs. Traditional Approaches. Netw. Innov. J. 2021, 18, 7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, D.; Watson, T. Exploring the Rounds of Communication in PBFT and MinBFT. Netw. Syst. Anal. 2016, 5, 34–41. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, H. Message Handling and Service States in Modern BFT Protocols. Syst. Netw. 2017, 12, 76–83. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Lee, M. Leader Nodes in Byzantine Protocols: Challenges and Solutions. J. Adv. Netw. Archit. 2019, 14, 22–30. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Luo, W. The Role of USIG Service in Consenting Nodes Security. Secur. Syst. Res. 2020, 13, 66–72. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.; Kaur, A. Exploring the VANET-Teegraph Algorithm: A New Paradigm for Vehicular Networks. J. Netw. Innov. 2020, 15, 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, L.; Reyes, M. Dynamics of Vehicular Networks: Challenges and Solutions. Transp. Syst. J. 2018, 10, 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R.; Malik, S. Trusted Execution Environments: The Future of Secure Computing. Mod. Comput. J. 2017, 12, 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, T.; Lane, D. Hardware-backed Memory Encryption: Intel SGX and its Applications. Adv. Syst. Rev. 2019, 13, 22–29. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, N.; Verma, A. Challenges in Vehicular Communication: The VANET-Teegraph Perspective. Commun. Rev. 2022, 17, 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.; Lee, H.; Park, J. OMTP Standards and the Role of GSMA in Standardizing TEE. Mob. Commun. Stand. 2021, 9, 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Q. Stakeholders in TEE Standardization: An In-depth Analysis. Technology Standards Journal 2019.

- Ongaro, D.; Ousterhout, J. (2014). In Search of an Understandable Consensus Algorithm (Extended Version). In Proceedings of the 2014 USENIX Annual Technical Conference (USENIX ATC ’14) (pp. 305–319). USENIX Association.

- Lamport, L. The Part-Time Parliament. ACM Trans. Comput. Syst. (TOCS) 1998, 16, 133–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, A., Bonneau, J., Felten, E., Miller, A., & Goldfeder, S. (2016). Bitcoin and Cryptocurrency Technologies: A Comprehensive Introduction. Princeton University Press.

- Miers, I., Garman, C., Green, M., & Rubin, A. D. (2013). Zerocoin: Anonymous Distributed E-Cash from Bitcoin. In 2013 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (S&P) (pp. 397-411). IEEE.

- Benet, J. (2014). IPFS - Content Addressed, Versioned, P2P File System. arXiv:1407.3561.

- Buterin, V. (2014). A Next-Generation Smart Contract and Decentralized Application Platform. Ethereum White Paper. Recuperado de https://ethereum.org/en/whitepaper/.

- Merkle, R. C. (1987). A Digital Signature Based on a Conventional Encryption Function. In G. R. Blakley & D. Chaum (Eds.), Advances in Cryptology — CRYPTO ’87 Proceedings (LNCS, Vol. 293, pp. 369-378). Springer-Verlag.

- Veronese, G. S., Correia, M., Bessani, A. N., Lung, L. C., & Veríssimo, P. (2013). Efficient Byzantine Fault-Tolerance. IEEE Transactions on Computers, 62(1), 16-30. [CrossRef]

- Cachin, C., Kursawe, K., & Shoup, V. (2001). Random Oracles in Constantinople: Practical Asynchronous Byzantine Agreement with Optimal Resilience. In Proceedings of the Twentieth Annual ACM Symposium on Principles of Distributed Computing (PODC ’01) (pp. 123-132). ACM. [CrossRef]

- Tapscott, D., & Tapscott, A. (2016). Blockchain Revolution: How the Technology Behind Bitcoin and Other Cryptocurrencies Is Changing Money, Business, and the World. Portfolio/Penguin.

- Liu, Y., Wang, K., Lin, Y., & Xu, W. (2019). A survey of blockchain-enabled internet of vehicles. IEEE Access, 7, 67333-67348. [CrossRef]

- Nakamoto, S. (2008). Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System. Recuperado de https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf.

- Schwartz, D., Youngs, N., & Britto, A. (2014). The Ripple Protocol Consensus Algorithm. Ripple Labs Inc. White Paper. Recuperado de https://ripple.com/files/ripple_consensus_whitepaper.pdf.

- Chen, Q., Schmidt-Eisenlohr, F., Jiang, D., Torrent-Moreno, M., Delgrossi, L., & Hartenstein, H. (2008, March). Overhaul: A realistic mobility model for VANET. In Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop on Mobile Vehicular Networks (MoVeNet) (pp. 1-7).

- d’Assunção, M. D. G. P., & Cunha, F. D. O. (2010). Evaluating the Communication Efficiency in VANET using a Hybrid Approach. International Journal of UbiComp (IJUBICC), 5(3), [POR COMPLETAR: pp. X-Y].

| Risk | Effect on VANETs |

|---|---|

| privacy attacks | Compromise the privacy of interested parties |

| Data integrity failures | Affects the reliability and security of data |

| cyber attacks | Causes network failures and malfunctions. |

| accidents | Causing property damage and injury |

| loss of life | Deaths caused by accidents |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).