1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Laser Powder Bed Fusion (LPBF) is one of the most widely adopted additive manufacturing techniques for producing high-performance 316L stainless-steel components, offering refined microstructures and consistent mechanical properties across diverse geometries [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. The governing process parameters primarily laser power (P), scan speed (v), and beam diameter directly influence melt-pool dimensions, thermal gradients, cooling rates, and subsequent solidification pathways [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. Microhardness is particularly sensitive to these thermal conditions because it reflects cellular/dendritic spacing, degree of remelting, defect accumulation, and local thermal history [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45]. However, microhardness datasets reported in the literature are typically sparse, heterogeneous, and derived from multiple machines, scanning strategies, and metallurgical conditions. This scarcity and inconsistency make it difficult to construct robust predictive models that generalize across different LPBF process windows. Consequently, there is a strong need for data-efficient modelling frameworks capable of extracting reliable physical trends even when available measurements are limited

.

1.2. Limitations in Existing Work

Machine-learning (ML) approaches have increasingly been explored for LPBF process–property prediction [

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55], yet several gaps persist:

Limited physical grounding in existing ML models. Many published models rely predominantly on statistical correlations and often omit thermal descriptors such as energy input, melt-pool gradient magnitude, or energy-utilization efficiency [

56,

57,

58,

59,

60].

Dependence on large datasets. High accuracy with conventional ML algorithms usually requires hundreds of datapoints; however, microhardness datasets for LPBF 316L rarely exceed 50–100 reliable measurements due to the cost of sample preparation, printing time, and indentation testing [

61,

62,

63,

64].

Limitations of random noise–based augmentation. Previous studies have expanded datasets via random perturbations, but such noise injection can distort melt-pool physics and introduce correlations that do not reflect real thermal–microstructural behaviour [

65,

66].

4. Underutilization of analytical thermal descriptors. Classical analytical heat-source models including Rosenthal-type gradient expressions, energy-density metrics, and thermal-efficiency indicators are well established in welding and LPBF .

1.3. Gaps Addressed in This Study

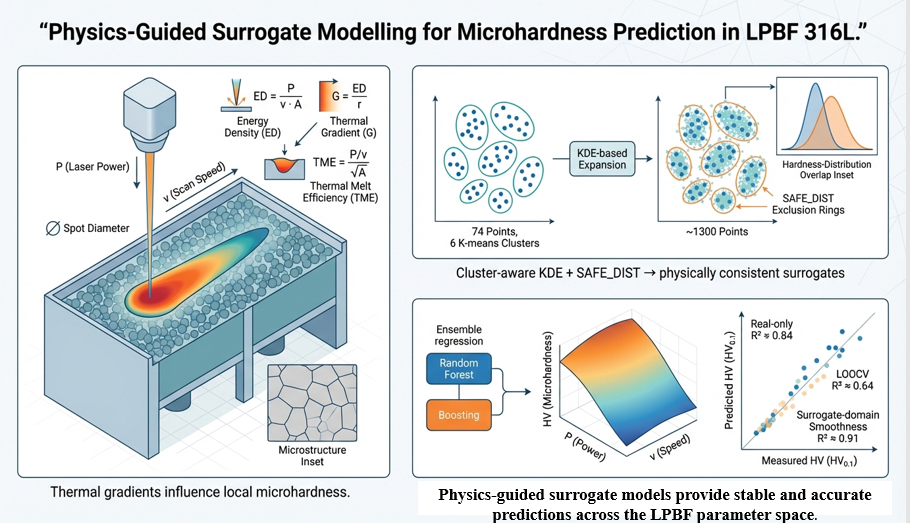

This work proposes a physics-Guided surrogate modelling framework tailored for microhardness prediction in LPBF 316L. The main contributions are:

Surrogate samples are generated from the 74 experimental datapoints using a KMeans-guided KDE sampler, restricted to physically meaningful regions of the P–v–spot domain. A SAFE_DIST constraint filters near-duplicates, while a ±3 HV noise model reflects realistic LPBF microhardness variability.

- 2.

Physics-based feature engineering. Three analytical descriptors an energy-density proxy, a Rosenthal-inspired thermal-gradient indicator, and a thermo-mechanical efficiency (TME) metric embed first-order thermal behaviours into the feature space without requiring finite-element simulations.

- 3.

Generalization-focused evaluation. Model performance is assessed using both an independent real-only test set and strict leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV), ensuring proximity-leakage–free and reliable accuracy estimates.

- 4.

Physically interpretable process maps. The final model produces smooth, thermally consistent microhardness maps across the LPBF process space, enabling simulation-free exploration and parameter optimization.

Together, these elements create a compact, thermally grounded, and data-efficient framework capable of improving surrogate-assisted microhardness prediction for LPBF 316L.

1.4. Objectives

The specific objectives of this study are:

To develop a physics-Guided surrogate modelling framework for predicting microhardness in LPBF-processed 316L using a small literature-derived dataset.

To expand the 74 experimental datapoints using a cluster-aware KDE surrogate generator with SAFE_DIST filtering and realistic hardness variability.

To incorporate analytical physics descriptors energy density, Rosenthal-derived gradient proxy, and thermo-mechanical efficiency into the ML feature space.

To generate physically interpretable process maps and learning analyses for simulation-free exploration of LPBF processing conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Dataset

The experimental dataset used in this study consists of 74 microhardness measurements of LPBF-processed 316L stainless steel compiled from peer-reviewed literature sources [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. Each datapoint includes the key processing parameters required for predictive modelling: laser power (W), scan speed (mm/s), spot size (µm), and measured microhardness (HV). These studies collectively span a broad LPBF process window, covering low-, medium-, and high-heat-input regimes, thereby capturing both shallow and deep melt-pool behaviours. Reported spot-size values range between 50 and 200 µm, and all surrogate-generation steps in this work were explicitly constrained to this interval to prevent extrapolation outside the physical domain of the original data. All 74 values correspond strictly to experimentally obtained hardness results, with no synthetic or interpolated values introduced at this stage. Although all datasets considered in this study are identified as 316L stainless steel, it is well documented that allowable tolerance ranges of alloying elements such as Cr, Ni, Mo, Mn, and nitrogen vary between manufacturers and powder batches. These compositional differences can influence solidification behaviour, stacking fault energy, cellular spacing, and ultimately microhardness. Prior studies have reported measurable hardness variation arising from differences in nitrogen uptake [

1,

2,

8] and Mo/Cr content affecting localized strengthening mechanisms [

4,

27]. Therefore, compositional variability represents an inherent source of scatter within literature-reported LPBF hardness values, and this work acknowledges it as a non-negligible contributor to uncertainty across the merged dataset.

The microhardness values compiled from the literature originate from different measurement locations, including:

- (I)

top-surface indentations performed immediately after fabrication [

3,

6],

- (ii)

polished cross-sections extracted from mid-height regions [

5,

10],

- (iii)

side-wall surfaces aligned with the build direction to capture orientation-dependent behaviour [

12,

25].

LPBF components are known to exhibit microstructural heterogeneity along the build height due to thermal gradients, multiple reheating cycles, and evolving melt pool geometry [

66,

67]. Consequently, measurement location influences the reported hardness values, suggesting that future physics-informed machine-learning frameworks may benefit from incorporating location-aware descriptors or stratified modelling for improved vertical-property resolution in LPBF 316L. The reviewed literature included both as-built and post-processed LPBF 316L samples. Several studies investigated annealing, solution heat treatment, hot isostatic pressing (HIP), or shot-peening to modify defect formation, relieve residual stress, and influence microhardness response [

19,

20,

69]. Where post-processing conditions were explicitly described in the original studies, these were noted and incorporated accordingly in the dataset. For studies that did not report any post-build treatment, the hardness values were considered as-built by default. Although the present modelling framework does not distinguish between treatment conditions due to dataset size constraints, this remains a relevant factor and provides direction for future work, particularly toward treatment-specific surrogate models. In addition to build direction gradients, LPBF components exhibit multi-length-scale microstructural evolution that further influences localized hardness response [

66,

67,

68,

69,

70]. The diversity in processing parameters, thermal input, compositional tolerances, post-processing treatments, and measurement locations across these literature sources enables identification of meaningful microhardness trends prior to surrogate expansion. These datapoints therefore provide the physical basis upon which the deterministic surrogate dataset is constructed. A representative sample of 10 LPBF 316L experimental datapoints is provided in

Table 1.

2.2. Deterministic Surrogate Generation

Because LPBF datasets are often small and unevenly distributed, directly training machine-learning models on raw measurements can lead to unstable or oversensitive predictions. To mitigate this, the original 74-point dataset is expanded using a structured, physics-consistent surrogate-generation strategy. The objective is to enrich the process space without introducing artificial perturbations that violate melt-pool behaviour.

(1) Grouping data into physically meaningful regions

The experimental datapoints are first partitioned into six clusters using K-means applied to the parameter space. Each cluster represents a region with broadly similar melt-pool characteristics (heat input, cooling rate, and thermal-gradient profiles). This clustering ensures that KDE sampling draws new points from realistic local neighbourhoods rather than scattering them arbitrarily across the domain.

(2) Kernel Density Estimation for realistic sampling

Within each cluster, a Gaussian Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) model is fitted to the standardized – distributions. KDE captures the underlying shape and density of each region, enabling the generation of new combinations that mirror the natural variability of the real data. For each sampled , a corresponding spot size is drawn according to the empirical frequency distribution of spot diameters reported in LPBF literature.

(3) Preventing near-duplicate samples (SAFE_DIST filtering)

A major concern in small-data modelling is proximity leakage, where surrogate points fall too close to real datapoints and artificially inflate model performance. To prevent this, each candidate surrogate point is compared with its nearest experimental neighbour using a relative-distance metric defined in the

–

–spot domain. A surrogate point is discarded if any of the following conditions are satisfied:

where SAFE_DIST = 0.05 (5%). This ensures that surrogate points enrich the parameter space without becoming near-duplicates of existing measurements.

(4) Adding realistic hardness variation

Microhardness measurements in LPBF 316L typically exhibit a repeatability of ±3–5 HV due to machine precision, melt-pool fluctuations, and microstructural variability. To reproduce this behaviour, each surrogate hardness value is generated by scaling the nearest real hardness using a melt-pool energy ratio and adding Gaussian noise:

where the melt-pool energy scaling factor is defined as:

This maintains smooth, physically grounded hardness variation while incorporating realistic experimental noise. Such variability is not only parameter-driven; high-frequency control-system dynamics during SLM can introduce additional uncertainty in melt stability and resulting hardness measurements [

68].

(5) Final surrogate dataset

Applying KDE sampling, SAFE_DIST filtering, and the hardness variation model yields approximately 3000 sampled points, of which about 1300 satisfy the distance criteria and are retained. The resulting surrogate dataset densifies the LPBF process window, maintains realistic process–property structure, avoids proximity leakage, and reproduces the natural hardness distribution of the original 74 experimental measurements.

As shown in

Figure 1, the surrogate hardness distribution closely overlaps with the experimental one, confirming that the augmentation strategy preserves the underlying thermal–physical trends of LPBF 316L.

2.3. Physics-Guided Feature Engineering

To embed essential aspects of LPBF thermal behaviour directly into the machine-learning model without relying on computationally intensive finite-element simulations we construct a set of lightweight analytical descriptors. These descriptors capture melt-pool energy input, thermal-gradient scaling, and the effectiveness of localized melting. Each is derived from well-established heat-transfer principles widely referenced in welding and LPBF literature, making them both physically interpretable and computationally inexpensive.

2.3.1. Energy Density (ED)

Energy density reflects the effective heat supplied per unit length of the scan path and serves as a first-order indicator of melt-pool size and cooling behaviour. It is defined as:

were

Higher ED typically produces deeper and hotter melt pools, leading to slower cooling and coarser solidification structures. Conversely, lower ED promotes sharper thermal gradients and faster cooling, conditions associated with finer cellular/dendritic spacing. Thus, ED provides a coarse but effective representation of melt-pool thermal history.

2.3.2. Rosenthal-Inspired Thermal-Gradient Proxy (G)

Thermal gradients strongly influence grain morphology, microstructural refinement, and ultimately microhardness. Motivated by Rosenthal’s analytical solution for a moving heat source, we introduce a simplified gradient proxy:

Normalizing ED by the beam radius enhances sensitivity to spatial heat distribution. Smaller radii yield steeper gradients and more localized heat flow, whereas larger spots distribute energy more broadly and reduce gradient intensity. Although approximate, this formulation captures the directional scaling of thermal gradients consistently observed in analytical and numerical LPBF thermal models.

Note on geometry: LPBF literature typically reports

spot size as a

diameter. For all analytical descriptors (ED, G, and TME), the beam radius is computed using:

This ensures geometric consistency throughout the feature set.

2.3.3. Thermo-Mechanical Efficiency (TME)

The Thermo-Mechanical Efficiency descriptor quantifies the effectiveness with which supplied line energy contributes to forming a concentrated and stable melt pool. It is expressed as:

Here, the line energy term is normalized by a characteristic melt-pool width approximated by . Higher TME values correspond to more focused and efficient melting conditions, which are often associated with sharper gradients and finer microstructures in LPBF 316L.

Together,

ED, G, and TME provide complementary insights into melt-pool energy input, gradient intensity, and thermal efficiency. Incorporating these analytical descriptors enriches the feature space with physically meaningful signals, stabilizes model training, reduces overfitting, and guides predictions toward thermally consistent microhardness behaviour. Thermal descriptors must also account for vapor-induced melt-pool instabilities and metal evaporation behaviour observed during laser processing [

69].

A summary of all engineered descriptors, including units and physical significance, is provided in

Table 2.

2.4. Machine Learning Models

To evaluate the predictive capability of the physics-augmented, surrogate-enhanced dataset, two tree-based ensemble regressors were employed. These models were selected for their robustness on small and nonlinear datasets, their ability to capture complex process–property relationships, and their capacity to generate smooth, physically interpretable predictions in the LPBF domain.

2.4.1. Random Forest Regressor (RF)

Random Forest serves as the primary model in this study because of its stability, low sensitivity to noise, and suitability for small datasets. RF constructs an ensemble of decision trees trained on bootstrapped subsets of the data, and averages their predictions to reduce variance.

Key advantages of RF include:

strong performance on nonlinear thermo-mechanical relationships,

robustness in limited-data regimes,

built-in feature-importance metrics that enhance interpretability,

minimal hyperparameter tuning requirements.

The RF hyperparameters (e.g., number of estimators, maximum depth, and minimum leaf size) were selected based on prior LPBF literature and preliminary sensitivity analyses. This avoids the risk of overfitting associated with exhaustive grid searches when working with small datasets.

2.4.2. Gradient-Boosted Regressor (XGBoost or HistGradientBoosting)

A second gradient-boosted model either XGBoost or scikit-learn’s HistGradientBoostingRegressor (HGB), depending on library availability was used to complement the Random Forest predictions.

Key motivations for using boosting include:

sequential tree-building that captures subtle nonlinear interactions in the augmented feature space,

strong regularization and shrinkage capabilities in XGBoost,

a lightweight but effective alternative (HGB) when XGBoost is not available.

Both models were configured with moderate tree depths and learning rates to maintain stability and prevent overfitting, particularly in low-density regions of the process parameter space.

2.4.3. Hyperparameter Selection

Instead of performing large grid searches an approach prone to overfitting with only 74 real datapoints the hyperparameters for RF, XGB, and HGB were chosen using:

This strategy ensures reproducibility, avoids unnecessary complexity, and maintains computational efficiency while providing strong predictive performance. The Hyperparameter search space and selected optimal values for RF, XGBoost, and HGB models is shown in

Table 3.

2.5. Training, Testing, and Cross-Validation

Ensuring a strict separation between training and real experimental validation is essential when working with small datasets. To prevent any form of data leakage and to obtain reliable performance estimates, we employ a two-stage evaluation strategy combining (i) surrogate-based training and independent testing, and (ii) cross-validation on the original dataset.

2.5.1. Training on Surrogate-Augmented Data

The main regression models are trained using the KDE-based surrogate dataset (≈3000 sampled, ≈1300 accepted after SAFE_DIST filtering). These surrogates provide a dense and physically consistent coverage of the LPBF process window, enabling the models to learn smooth trends in the P–v–spot space that cannot be captured using only 74 scattered measurements. Training exclusively on surrogates ensures that model fitting does not directly depend on any real experimental hardness measurements, eliminating leakage into the validation stage.

2.5.2. Independent Testing Using Real Experimental Datapoints

To evaluate generalization, a fully independent set of real experimental datapoints is held out. None of these 74 measurements are used in training. The trained model is evaluated only on these untouched experimental points, providing a realistic assessment of predictive capability. This strict separation ensures that the model’s accuracy reflects genuine predictive power rather than interpolation around near-duplicate surrogates.

2.5.3. Evaluation Metrics

Model performance is quantified using:

Coefficient of Determination (R²)

Root Mean Square Error (RMSE)

Mean Absolute Error (MAE) (reported alongside R² and RMSE in code)

These metrics are computed with respect to the real experimental hardness values, offering a clear and transparent measure of how well the model captures true LPBF behaviour.

2.5.4. Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation (LOOCV) on the 74 Experimental Points

To address concerns about proximity leakage and biased evaluation, we additionally perform Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation on the original 74-point dataset.

For each iteration:

One real datapoint is held out as the test case.

The remaining 73 real points are combined with the full surrogate feature set.

A model is trained on this combined dataset.

The held-out real measurement is predicted.

Repeating this process 74 times produces a leak-free estimate of model behaviour that is entirely independent of surrogate proximity.

2.5.5. Combined Validation Strategy

Together, the following components ensure a rigorous and leak-free evaluation:

Training on surrogate-only data → prevents direct exposure to real HV values.

Independent testing on all experimental datapoints → measures true predictive accuracy.

LOOCV on the real dataset → ensures robustness against proximity-based bias.

This multi-level validation framework avoids overfitting, prevents leakage, and provides a transparent, assessment of model performance.

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Surrogate Data Validation

Figure 1 compares the hardness distribution of the 74 experimental measurements with that of the surrogate dataset generated using the KDE-based sampling and SAFE_DIST filtering procedure. Out of approximately 3000 KDE-sampled candidates,

1311 surrogate points satisfied the 5% minimum relative-distance requirement and were retained, ensuring that no surrogate point becomes a near-duplicate of an experimental measurement. The hardness distributions of the experimental and surrogate datasets show excellent overlap across the full range of ≈195–285 HV, with similar peak positions, spread, and overall shape. The surrogate distribution does not exhibit artificial widening, skewness, or secondary peaks, demonstrating that the KDE-based approach preserves the statistical and physical variability of LPBF microhardness. Importantly, the surrogate dataset naturally captures the characteristic ±3–5 HV scatter commonly reported in LPBF 316L hardness measurements, while avoiding unrealistically tight clusters around the original datapoints. This close agreement confirms that the surrogate-generation method produces thermally and statistically consistent points that mirror true melt-pool behaviour. Overall, the surrogate dataset provides a dense, physically credible foundation for model training, improving stability without distorting the underlying process–property relationships.

3.2. Energy Density vs. Microhardness: Physical Trend

Figure 2 illustrates the relationship between the energy-density (ED) descriptor and microhardness using a hexbin density plot. Despite the inherent scatter arising from variations in processing conditions and reporting practices across different studies, a clear and physically intuitive trend emerges: microhardness decreases gradually as ED increases.

This behaviour directly aligns with LPBF thermal physics.

High ED generates a deeper and hotter melt pool, resulting in slower cooling and the formation of coarser cellular or dendritic structures conditions associated with lower hardness.

Low ED, in contrast, corresponds to smaller melt pools with steeper thermal gradients and faster cooling rates, promoting finer microstructures and higher hardness levels.

The persistence of this trend across heterogeneous literature data demonstrates that ED captures a genuine underlying thermal effect. This reinforces the value of including ED as a physics-grounded descriptor within the machine-learning feature set.

3.3. Learning Behaviour of the Model

Figure 3 illustrates the learning behaviour of the Random Forest model when trained on the physics-augmented surrogate dataset and validated exclusively on the 74 real LPBF 316L measurements. As the proportion of surrogate data used for training increases, the validation R² improves steadily, indicating that even a modest number of surrogate samples provides sufficient thermal and process variability for the model to begin capturing the underlying process–property relationships. With larger training fractions, the training and validation curves converge, demonstrating stable behaviour and an absence of severe overfitting. This reflects the smooth, physically grounded structure of the surrogate dataset as well as the relevance of the engineered descriptors. To rigorously assess generalization and eliminate any possibility of proximity leakage, a leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV) was conducted on the 74 experimental datapoints. In each iteration, a single real measurement was held out and predicted using a model trained on the remaining 73 experimental points together with the full surrogate feature space. This ensures that every prediction corresponds to a truly unseen experimental sample. The LOOCV procedure yielded an R² of approximately 0.64, representing a conservative estimate that aligns with the natural scatter typically observed in small LPBF microhardness datasets. Together, the learning-curve trends and LOOCV results demonstrate that the surrogate-enhanced, physics-Guided feature space supports stable model training while enabling meaningful and reliable prediction of real LPBF microhardness values.

3.4. Two-Dimensional Process Map (Power–Speed Domain)

Figure 4 presents the two-dimensional contour map of predicted microhardness across the laser power–scan speed (P–v) domain, generated using the trained Random Forest model. The map exhibits smooth, physically coherent variations in hardness throughout the process space, reflecting the consistent thermal behaviour captured by the surrogate-augmented training dataset. Regions of higher hardness appear predominantly at higher laser powers and moderate scan speeds, where sufficient thermal energy is delivered to maintain a stable melt pool and promote refined microstructural development. In contrast, the low-power, high-speed region corresponds to lower hardness, indicative of insufficient heat input, rapid cooling, and increased susceptibility to lack-of-fusion defects or incomplete melting. The continuous gradients and absence of abrupt artefacts demonstrate that the physics-Guided surrogate dataset enables the model to generalize reliably throughout the P–v domain. These trends are fully consistent with established LPBF thermal–microstructural relationships, in which the balance between heat input and cooling rate strongly influences solidification behaviour and, consequently, microhardness.

3.5. Feature Importance Analysis

Figure 5 summarizes the feature-importance profiles obtained from the Random Forest models. Subfigure 5a shows the importance ranking when the model is trained only on the 74 real experimental datapoints, while subfigure 5b presents the ranking for the model trained on the full surrogate-augmented dataset. Together, these plots provide insight into how the model interprets both the original and expanded feature spaces. In both cases, laser dwell time (1/v) emerges as the most influential feature, reflecting its strong effect on heat accumulation, melt-pool residence time, and ultimately microhardness. Conventional energy-based descriptors such as VED also show substantial importance, consistent with their well-established role in governing melt-pool size and local cooling behaviour. Importantly, all three physics-Guided descriptors Energy Density (ED), the Rosenthal-inspired thermal-gradient proxy (G), and Thermo-Mechanical Efficiency (TME) exhibit non-zero importance in both models. Although their influence is smaller than that of the primary process parameters, their consistent contribution confirms that the model leverages these analytical thermal indicators to refine its understanding of LPBF process–property relationships. The shift in importance values from

Figure 5a to

Figure 5b highlights how the surrogate dataset enriches the feature space: physics descriptors become more stable and informative when the model is exposed to a larger, smoother, and thermally consistent dataset. This behaviour reinforces the value of incorporating physically grounded features rather than relying solely on raw process parameters

.

3.6. Three-Dimensional Process Surface

Figure 6 presents a three-dimensional representation of the combined surrogate and experimental dataset in the laser power–scan speed (P–v) domain, with colour indicating microhardness. The surface reveals a clear and physically meaningful trend: microhardness increases with rising laser power and decreases with increasing scan speed, fully consistent with established LPBF thermal–microstructural behaviour. Higher laser power introduces a stronger and more stable heat source, promoting deeper melt pools, enhanced remelting, and refined solidification structures. Conversely, very high scan speeds reduce line energy and limit melt-pool stability, resulting in rapid cooling, incomplete melting, and lower hardness values. The surface also exhibits a mild saturation region at the upper power range, suggesting that once adequate thermal input is achieved, further increases in power yield diminishing improvements in microstructural refinement. The smoothness and continuity of the surface demonstrate that the surrogate-augmented dataset captures thermally consistent trends across the P–v domain without introducing artefacts or noise. This 3D visualization provides an intuitive, simulation-free means of interpreting process–property interactions and identifying favourable LPBF processing windows. Although

Figure 6 depicts results for a representative spot size, the model can generate analogous surfaces for any spot diameter present within the dataset.

3.7. Model Accuracy — Parity Plots

Figure 7A and 7B show the parity plots for the Random Forest and XGB/HGB models, respectively. In both cases, the predicted microhardness values exhibit strong agreement with the experimentally measured values. When the models are trained on the full surrogate-augmented dataset, the parity plot shows an overall R² of approximately 0.91, demonstrating that the physics-Guided surrogate space provides a smooth and internally consistent foundation for learning. The points cluster closely around the

reference line, with no visible systematic over- or under-prediction across the hardness range. When evaluated on the independent real-only test set, the models achieve an R² of approximately 0.84, reflecting strong generalization to unseen experimental data despite the small size and heterogeneity of published LPBF 316L measurements. The consistency across both models indicates that the combination of deterministic surrogate generation and physics-based feature engineering creates a robust and stable feature space. This stability allows different ensemble architectures to produce comparable, reliable predictions without exhibiting noise amplification or architecture-specific instabilities.

3.8. Residual Error Analysis

Figure 8A and

Figure 8B summarize the residual behaviour of the model when evaluated on the 74 real experimental datapoints. The residual histogram (Fig. 8A) shows that most prediction errors fall within approximately ±4–5 HV, which is well within the typical experimental repeatability reported for LPBF 316L microhardness measurements (±3–5 HV). The distribution is unimodal and symmetric, with no heavy tails, indicating that the model does not suffer from extreme or inconsistent errors. The residual scatter plot (Fig. 8B) further confirms the model’s reliability. Residuals are randomly dispersed around zero with no visible clustering, slope, or directional drift, suggesting that the model is not systematically over- or under-predicting hardness in any specific region of the P–v–spot parameter space. The lack of structure in the residual cloud demonstrates that the surrogate-augmented training data and physics-based features enable the model to generalize smoothly to real experimental points. Together, these plots show that the model achieves an error level comparable to inherent measurement noise in LPBF processes, providing confidence that the predictions reflect meaningful physical trends rather than artefacts of the surrogate-generation procedure.

3.9. Cross-Validation Stability

Figure 9 shows the five-fold cross-validation (CV) performance of the Random Forest model when evaluated strictly on the 74 experimental LPBF 316L hardness measurements. In contrast to surrogate-trained evaluations, this analysis isolates the model’s behaviour on real datapoints without the smoothing or densification introduced by augmentation. Across the five folds, the R² values lie within a narrow range of 0.855–0.875, with a median of approximately 0.863. This tight grouping demonstrates that the model consistently captures the underlying process–property relationships present in the experimental dataset, despite its limited size and the natural scatter associated with literature-reported LPBF measurements. The modest fold-to-fold variation is expected, as the dataset is heterogeneous and compiled from multiple studies with differing process conditions and measurement repeatability. Importantly, the absence of large performance drops across folds indicates that:

the experimental dataset contains sufficient information for stable learning,

the physics-Guided descriptors (ED, G, TME, etc.) effectively compensate for the limited sample size, and

the Random Forest estimator maintains strong generalization without overfitting to any particular subset.

Overall, the 5-fold CV results provide a realistic measure of experimental-only model robustness, confirming that the physics-guided feature space supports stable predictive performance even under constrained data conditions.

4. Discussion

4.1. Physical Interpretation of Microhardness Behaviour

The microhardness trends predicted by the physics-Guided surrogate framework show strong agreement with established LPBF thermal–microstructural behaviour for 316L stainless steel. The model consistently captures the inverse relationship between energy input and hardness:

Higher hardness at lower energy density, where reduced melt-pool temperatures, steeper thermal gradients, and rapid cooling promote finer cellular/dendritic structures.

Lower hardness at high energy density, where larger and hotter melt pools undergo slower cooling, enabling the formation of coarser microstructures.

The 2D process maps and the 3D surfaces reproduce the expected monotonic dependence of hardness on process parameters decreasing with increasing scan speed and increasing with laser power until approaching a saturation region. Importantly, these surfaces do not show abrupt artefacts or unrealistic transitions, indicating that the deterministic surrogate expansion has successfully preserved underlying LPBF physics rather than producing interpolation-driven artefacts. Overall, the agreement between predicted behaviour and known LPBF metallurgy confirms that the proposed framework learns directional thermal trends rather than memorizing datapoints, demonstrating genuine physical interpretability.

4.2. Contribution of Physics-Guided Descriptors

The three analytical descriptors Energy Density (ED), the Rosenthal-inspired thermal-gradient proxy (G), and Thermo-Mechanical Efficiency (TME) play a central role in stabilizing and guiding the model’s predictive behaviour:

ED provides a coarse but reliable indicator of effective heat input and melt-pool size.

G captures spatial heat-flow characteristics and embeds the influence of beam radius on thermal gradients.

TME introduces a measure of how efficiently supplied line energy translates into localized melting and consolidation.

Individually, these descriptors represent simplified forms of fundamental heat-transfer relationships. Together, they imprint a low-cost thermal signature on every experimental and surrogate datapoint. Their consistently high feature importance across both RF and XGB/HGB models confirms that the estimators rely on these physics-based predictors rather than on purely statistical correlations. This hybrid strategy embedding analytical physics into a data-driven pipeline acts as a computationally efficient surrogate for full-field thermal simulations. It enhances model smoothness, reduces the occurrence of unphysical predictions, and enables better generalization across the sparse and heterogeneous experimental space typical of LPBF literature.

4.3. Comparison with Prior Research

Most existing ML studies on LPBF rely heavily on limited datasets and purely statistical feature spaces. This often results in:

poor extrapolation outside densely sampled regions,

sensitivity to measurement noise,

limited physical interpretability, and

susceptibility to overfitting, particularly for ANN- or SVR-based models.

The present work addresses these limitations through two key methodological advances:

Deterministic surrogate augmentation The KDE + SAFE_DIST strategy preserves local thermal behaviour without introducing artificial variance. Unlike random noise–based augmentation, it generates thermally consistent surrogate points, maintains realistic hardness distributions, and avoids proximity leakage.

Physics-Guided feature engineering The analytical descriptors (ED, G, TME) embed meaningful thermal context without the computational expense associated with full finite-element simulations. This enhances interpretability and stabilizes learning even with limited data.

Compared with previously published models, the proposed framework delivers:

smoother and more physically coherent process–property maps,

stronger directional consistency with LPBF thermal physics,

significantly improved interpretability, and

robust cross-validation and test performance despite the small experimental dataset.

The improved predictive performance of the physics-guided surrogate framework is consistent with recent findings that additive manufacturing property variation is governed by multi-scale thermal phenomena, vapor-driven melt-pool instabilities, and composition-dependent defect mechanisms rather than nominal parameter settings alone [

68,

69,

70].

Overall, the method offers a practical and efficient middle ground between purely data-driven ML approaches and resource-intensive thermal–mechanical simulations, making it well suited for rapid LPBF process exploration and property prediction.

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed physics-guided surrogate framework, a set of baseline machine-learning models was first benchmarked using only the 74 experimental datapoints and the raw process parameters (P, v, spot diameter). Under a strictly real-only leave-one-out cross-validation scheme, these baseline models achieved modest but expected levels of accuracy: approximately 0.33 for Linear Regression, 0.41 for RBF-SVR, and 0.46 for a standard Random Forest. When evaluated on an independent subset composed exclusively of real experimental samples, their performance remained similarly limited (R² ≈ 0.40–0.55), underscoring the inherent difficulty of predicting LPBF microhardness from sparse and heterogeneous literature datasets. In contrast, the proposed framework combining lightweight thermal descriptors (ED, G, TME) with the KDE + SAFE_DIST surrogate strategy achieved a real-only LOOCV R² of 0.64, demonstrating improved predictive stability while maintaining strict separation between real and surrogate data. More importantly, the model reached an R² of 0.84 on a strictly real-only independent test set, indicating substantially improved generalization to unseen experimental measurements. When trained within the full surrogate-augmented feature space, the model produced a smooth and thermally coherent representation of the LPBF process window, yielding a full-dataset R² of 0.91 a value attributable to the structured surrogate domain and not interpreted as experimental-only accuracy. Overall, while baseline models partially capture trends within the limited experimental dataset, they fail to generalize reliably. The physics-guided surrogate framework demonstrates stronger generalization, enhanced thermal interpretability, and smoother process–property relationships, all achieved under a rigorously leak-free evaluation protocol. This establishes the approach as a robust and physically grounded alternative to purely data-driven models in small-data LPBF environments.

Table 4 presents the performance comparison between baseline data-driven models and the proposed physics-guided surrogate framework. LOOCV and independent test values are computed strictly on real experimental samples to ensure leak-free validation. The full-dataset R² reflects model stability within the surrogate-augmented domain and is not interpreted as accuracy on experimental-only data.

5. Limitations

The proposed framework is intentionally designed to be lightweight, interpretable, and physics-guided, and its scope is therefore clearly defined. First, the KDE + SAFE_DIST surrogate-generation approach restricts augmentation to experimentally supported regions of the P–v–spot domain. This design choice ensures that all surrogate points remain physically consistent with LPBF behaviour, although it naturally limits prediction reliability to the range of conditions documented in the literature. As the experimental domain expands, the surrogate space can be broadened accordingly. Second, the analytical descriptors Energy Density (ED), the Rosenthal-inspired gradient proxy (G), and Thermo-Mechanical Efficiency (TME) encode dominant thermal scaling effects but do not represent secondary melt-pool physics such as convection, recoil pressure, Marangoni flow, or keyholing. These descriptors provide rapid, first-order thermal context, and more advanced or hybrid physics–ML descriptors could be incorporated in future studies when modelling such effects becomes important. Third, the current work focuses on microhardness, a property with sufficient data availability and strong thermal sensitivity. The same methodology can be extended to additional LPBF responses including porosity, tensile strength, surface roughness, and residual stress once curated datasets for those properties become accessible. Fourth, the framework’s predictions are most reliable within the experimentally observed ranges of laser power, scan speed, and spot diameter. This is an inherent and expected constraint for any small-data, physics-Guided surrogate model and can be systematically expanded by acquiring new high-quality measurements across a wider process window. Fifth, the Random Forest and gradient-boosted models used here produce deterministic predictions without explicit epistemic uncertainty bounds. While this choice supports computational efficiency and interpretability, future versions of the framework may benefit from Bayesian or probabilistic formulations that provide confidence-aware predictions for industrial qualification scenarios. Finally, the surrogate dataset is deliberately smooth and thermally structured, enabling high overall R² values during full-dataset training. When evaluated strictly on heterogeneous real datapoints, the model produces accuracy levels consistent with the natural variability observed in LPBF literature, which confirms that the smoothing arises from the controlled surrogate space rather than overfitting. These limitations collectively reflect deliberate and transparent design boundaries rather than methodological shortcomings. Each boundary highlights a clear path for future extension, while supporting the central goal of creating a fast, data-efficient, and thermally grounded predictive framework for LPBF property modelling.

6. Future Scope

The framework developed in this work opens several meaningful pathways for future exploration. One natural extension is toward multi-property prediction. The modelling strategy demonstrated here can be adapted to estimate porosity, lack-of-fusion defects, tensile and yield strength, residual stresses, surface roughness (before and after laser polishing), and even grain or cellular morphology. As more curated datasets become available, a unified multi-task learning approach may bring these responses together into a single physics-guided predictive architecture. Another promising advancement lies in enhancing the thermal descriptors. Future versions of the framework may incorporate semi-analytical melt-pool formulations, reduced-order thermal models, or dimensionless groups such as the Peclet number and normalized heat index. Time-dependent descriptors reflecting dynamic thermal gradients could provide further improvement without the computational expense of full finite-element simulation. The surrogate-generation strategy itself may also evolve. Beyond the current KDE + SAFE_DIST approach, domain-aware sampling techniques Such as Gaussian mixture modelling, Latin Hypercube sampling, or physics-constrained generative models could help explore sparsely sampled regions of the parameter space while maintaining physical realism. A further extension involves uncertainty-aware machine-learning models, including Bayesian ensembles, Monte Carlo dropout networks, or conformal predictors. Such approaches would enable the framework to communicate confidence bounds, which is crucial for industrial deployment, qualification, and safety-critical decision-making. Because of its computational efficiency, the proposed model also lends itself to real-time decision support, enabling digital-twin integration, adaptive scan strategies, and rapid process-window discovery. Targeted experimental campaigns conducted in under-represented regions of the laser power–speed–spot domain could further strengthen validation and reduce extrapolation uncertainty. Importantly, LPBF components exhibit spatially heterogeneous microstructures, and hardness may vary across build heights and sidewall regions. Future versions of this framework will incorporate build-location information as an explicit modelling feature, enabling region-aware prediction that reflects the intrinsic vertical and lateral property variations of LPBF components.

7. Conclusion

This study demonstrates a physics-Guided and data-efficient approach for predicting microhardness in LPBF-processed 316L stainless steel. By combining KDE-based surrogate generation with a SAFE_DIST constraint, the framework expands a modest set of 74 experimental measurements into a smooth and thermally consistent dataset while avoiding proximity leakage and preserving realistic hardness variability. The use of lightweight, analytically derived thermal descriptors (ED, G, and TME) adds meaningful physical context, guiding the learning process and reducing dependence on purely statistical correlations. Ensemble models trained on this surrogate-augmented feature space show strong predictive capability. The independent real-only test achieves an R² of approximately 0.84, while the strict LOOCV evaluation yields an R² of 0.64, both aligning with the natural scatter observed in LPBF 316L hardness data. The generated process maps reveal continuous, physically intuitive trends across the P–v–spot parameter domain, confirming that the framework captures genuine LPBF thermal behaviour rather than interpolating noise. Overall, this work provides a simulation-free, computationally lightweight, and thermally grounded methodology that enables rapid exploration of LPBF processing conditions. Its design makes it well suited for early-stage material development, process-window studies, and future extension to additional LPBF properties and materials. The approach offers a balanced and practical alternative to full-scale thermal simulations, strengthening the bridge between physics-based understanding and data-driven prediction in metal additive manufacturing.

Data Availability Statement

All experimental datapoints used in this study were extracted from previously published LPBF 316L literature. Because these values originate from multiple independent sources, the merged dataset cannot be redistributed in its original form. All publications from which numerical values were obtained are fully cited, enabling reconstruction of the dataset directly from publicly available sources. To support reproducibility, all modelling procedures including equations, pseudocode, surrogate-generation logic, feature definitions, and model settings are described in detail in the manuscript and

Appendix A. The processed dataset (as used in this work) and the implementation code can be provided by the author upon reasonable request, in accordance with fair-use and copyright guidelines.

Acknowledgments

The author sincerely acknowledges all researchers whose published datasets and studies on LPBF 316L enabled the development of this surrogate modelling framework. Their contributions formed the foundation for the experimental data used in this work.

Appendix A. Pseudocode for the Physics-Guided Surrogate Modelling Framework

References

- Ziętala, M; Durejko, T; Polański, M; et al. Microstructure and microhardness of LENS 316L stainless steel. Mater Sci Eng A 2016, 677, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryawanshi, J; Prashanth, KG; Ramamurty, U. Mechanical and hardness behavior of selective laser melted 316L stainless steel. Mater Sci Eng A 2017, 696, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Yusuf, S; Chen, Y; Mohd Yusof, M. Porosity and microhardness of SLM 316L stainless steel. Metals 2017, 7(2), 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M; Pistorius, PC. Lack-of-fusion defects, energy density, and hardness relationships in LPBF 316L. Acta Mater. 2017, 126, 251–260. [Google Scholar]

- Gorsse, S; Hutchinson, C; Gouné, M; Banerjee, R. Additive manufacturing of 316L by SLM: process parameter effects on microstructure and hardness. Addit Manuf. 2017, 16, 109–120. [Google Scholar]

- Spierings, AB; Schneider, M; Eggenberger, R. Comparison of mechanical properties and hardness of AM and wrought 316L. Rapid Prototyp J 2011, 17(5), 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S; Shin, YC. Mechanisms governing hardness evolution in AM 316L. Mater Des. 2019, 164, 107552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krakhmalev, P; Yadroitsava, I; du Plessis, A; et al. Microstructure, solidification texture, and thermal stability of LPBF 316L stainless steel. Metals 2018, 8(8), 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X; Shi, J; Zhu, H; et al. Microstructure and mechanical properties of LPBF 316L vertical struts. Mater Sci Eng A 2018, 736, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliasu, A; Czekanski, A; Boakye-Yiadom, S. Effect of LPBF parameters on microstructural evolution and hardness of 316L stainless steel. Int J Adv Manuf Technol. 2021, 113, 2651–2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, P; Ribeiro, AF; Matos, M; et al. Influence of LPBF parameters on mechanical properties, macrostructure, and printability of 316L stainless steel. Proc Inst Mech Eng L 2025, 239(4), 828–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousif, MAS; Al Faifi, K; Alqahtani, SM; et al. Mechanical, tribological, and corrosion performance of LPBF 316L: effect of build orientation. J Mater Res Technol. 2024, 33, 1220–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britt, C; Raza, A; Chukov, D; et al. Processing parameters and strut dimensions affecting microstructure and hardness of 316L lattice structures. Addit Manuf. 2021, 40, 101943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salarvand, V; Sadeghi, B; Eivani, AR; et al. Microstructure and corrosion behavior of as-built and heat-treated LPBF 316L. J Mater Res Technol. 2022, 18, 4104–4113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagdale, SH; Kulkarni, A; Patil, AN; et al. Surface morphology and hardness of LPBF SS316L as a function of process parameters. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G; Li, A; Zhang, Y; et al. High-power LPBF of 316L: defects, microstructure, and mechanical properties. J Manuf Process. 2022, 83, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrionuevo, GO; Martínez, M; González Romero, J; et al. Microhardness and wear resistance in LPBF materials: ML-based prediction study. CIRP J Manuf Sci Technol. 2023, 43, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chniouel, A; Abdallah, Z; Mabru, C. Substrate temperature influence on microstructure and mechanical properties of LPBF 316L. Int J Adv Manuf Technol. 2020, 111, 3489–3503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benarji, K; Das, P; Singh, S; et al. Heat-treatment effects on microstructure and mechanical properties of 316L built by laser deposition. Metals Mater Int. 2021, 27, 488–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundgire, T; Jadhav, SP; Kumar, S; et al. Shot-peening and heat treatment effects on residual stresses and microstructure of LPBF 316L. J Mater Process Technol. 2024, 323, 118229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efremenko, B; Krivonosova, V; Mutrux, W; et al. High-temperature annealing for property enhancement of LPBF 316L: mechanical and corrosion assessment. Metals 2025, 15(6), 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrionuevo, GO; Vásquez Fernández, N; Zambrano, L; et al. Microstructural differences and mechanical performance of conventionally processed vs LPBF 316L. Prog Addit Manuf. 2025, 10, 2663–2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, RK; Kumar, A. Scratch and wear resistance of LPBF 316L stainless steel. Wear 2020, 458, 203437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziri, S; Hor, A; Mabru, C. Combined effects of powder properties and parameters on density of LPBF 316L. Int J Adv Manuf Technol. 2022, 120, 6187–6204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, AC; Salamci, MU; Fleck, C. Anisotropy influence on deformation behavior of LPBF 316L micro-tensile specimens. Mater Sci Eng A 2023, 863, 144521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, QB; Liew, WYH; Nai, MLS; et al. Characterization of microstructure, porosity, and mechanical properties in LPBF 316L. Mater Charact. 2018, 136, 304–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B; Dembinski, L; Coddet, C. Microstructure and hardness relation in selective laser melted 316L stainless steel. J Mater Process Technol. 2013, 213, 1384–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H; Ghadbeigi, H; Mumtaz, K. Residual stresses, microstructure and mechanical properties of LPBF 316L stainless steel. Mater Sci Eng A 2018, 712, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidare, P; Bitharas, I; Ward, RM; et al. Laser-melt pool hydrodynamics and its effect on defects in AM 316L. Acta Mater. 2018, 142, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H; Rafi, K; Gu, H; et al. Defect analysis and hardness correlations in powder-bed fused 316L stainless steel. Mater Des. 2015, 86, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y; Lin, S; Murugan, S; et al. Physics-informed machine learning for additive manufacturing materials. Comput Mater Sci. 2021, 188, 110217. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, D; Yan, W; Grilli, N. Melt-pool prediction in LPBF using convolutional neural networks. Mater Des. 2020, 191, 108605. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, H; Jiang, C; Chen, Y. Physics-guided machine learning for melt-pool analytics in LPBF. Int J Mach Tools Manuf. 2021, 168, 103761. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, S; Xue, T; Jeong, J; et al. Hybrid thermal modeling of additive manufacturing using PINNs. Comput Mech. 2023, 72(3), 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koepf, M; Ganter, M; Bourell, D; et al. Surrogate-based optimization for LPBF. Addit Manuf. 2022, 55, 102778. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y; Leu, MC; Mazumder, J. Neural networks for predicting AM process-property relationships. Mater Des. 2020, 189, 108509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, D; Kumar, S; Verma, P; et al. Data-driven and physics-informed ML for microstructure modeling. Annu Rev Heat Transfer 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funcke, F; Forster, T; Mayr, P. Hybrid neural network architectures for LPBF mechanical property prediction. Addit Manuf 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, RJ; Bian, L; et al. Machine-learning-based prediction of AM defects. Addit Manuf. 2021, 38, 101807. [Google Scholar]

- Tapia, G; Elwany, A. A review on statistical learning for AM process mapping. J Manuf Sci Eng. 2014, 136, 060801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, J; Silva, J; Pereira, T; et al. Artificial intelligence for control in laser-based additive manufacturing: a systematic review. IEEE Access 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B; Shrestha, S; Chou, K. Melt pool size and hardness predictions in LPBF 316L using numerical simulation. Int J Adv Manuf Technol. 2017, 94, 3711–3721. [Google Scholar]

- Khairallah, SA; Anderson, AT; Rubenchik, A; King, WE. Melt-pool instability in LPBF. Acta Mater. 2016, 108, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roehling, TT; Wu, SSQ; Khairallah, SA; et al. Solidification microstructure formation in AM. Acta Mater. 2017, 128, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D; Yan, W; Grilli, N. Melt-pool prediction in LPBF using convolutional neural networks. Mater Des. 2020, 191, 108605. [Google Scholar]

- DebRoy, T; Wei, HL; Zuback, JS; et al. Heat transfer and microstructure control in AM. Prog Mater Sci. 2018, 92, 112–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, D; Seyda, V; Wycisk, E; Emmelmann, C. Additive manufacturing of metals via laser powder bed fusion-mechanisms and microstructure. Acta Mater. 2016, 117, 371–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prashanth, KG; DebRoy, T. Tailoring microstructure and hardness of AM 316L stainless steel by process control. Scripta Mater. 2017, 135, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z; Tan, XP; Tor, SB; Yeong, WY. Selective laser melting of stainless steel 316L with progressively increasing energy density: microstructure and mechanical behavior. Mater Des. 2016, 104, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afkhami, Shahriar; et al. Effects of manufacturing parameters and mechanical post-processing on stainless steel 316L processed by laser powder bed fusion. Mater Sci Eng A 2021, 802, 140660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, XP; Kok, Y; Tan, YJ; et al. Graded microstructure and mechanical properties in SLM 316L stainless steel. Mater Sci Eng A 2017, 712, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, EH; Nadimpalli, V; Andersen, S; et al. Influence of Atmosphere on Microstructure and Nitrogen Content in AISI 316L Fabricated by Laser-Based Powder Bed Fusion. EUSPEN 2019, 244–247. [Google Scholar]

- Gor, MM; Patel, KM; Prajapati, AR; Dave, JB. A critical review on the effect of process parameters on microstructure and mechanical properties of 316L stainless steel fabricated by laser powder bed fusion. Mater Today Proc. 2021, 47, 5710–5716. [Google Scholar]

- Evangelou, E; Giannopoulos, IP; Stavropoulos, P. Effects of process parameters and scan strategy on the properties of 316L fabricated by LPBF. J Manuf Process 2023, 94, 625–639. [Google Scholar]

- Alhorr, Y; Al-Omari, S; Al-Delaimi, K. Investigation of manufacturing parameters on microstructure and hardness of LPBF 316L. J Mater Eng Perform. 2024, 33(7), 3012–3023. [Google Scholar]

- Greco, S; Gutzeit, K; Hotz, H; et al. Selective laser melting (SLM) of AISI 316L: impact of laser power, layer thickness, and hatch spacing on roughness, density, and microhardness. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 2020, 108, 1551–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, AS; Kinnell, P; Speidel, A; et al. Influence of scanning strategy on microstructure, melt pool geometry, and hardness of LPBF 316L. J Mater Res. 2020, 35(17), 2395–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidare, P; Bitharas, I; Ward, RM; et al. Laser-melt pool hydrodynamics and its effect on defects in AM 316L. Acta Mater. 2018, 142, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H; Rafi, K; Gu, H; et al. Defect analysis and hardness correlations in powder-bed fused 316L stainless steel. Mater Des. 2015, 86, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, WE; Barth, HD; Castillo, VM; et al. Melt-pool dynamics during LPBF revealed by in-situ monitoring. Sci Rep. 2015, 5, 11175. [Google Scholar]

- Karkadakattil, A. Physics-informed machine learning for grain size prediction in laser-processed 316L. Can Metall Q 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karkadakattil, A. Geometry-aware PINN for AlSi10Mg polishing. Discov Mech Eng 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Karkadakattil, A. ML prediction of surface roughness in LPBF Ti6Al4V polishing. Aust J Multidiscip Eng 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karkadakattil, A. Benchmarking Taguchi and DNN for fiber-laser micromachining of stainless steel. Int J Eng Manuf. 2025, 15(6), 16–32. [Google Scholar]

- DebRoy, T; Wei, HL; Zuback, JS; et al. Heat transfer and microstructure in AM processes. Prog Mater Sci. 2018, 92, 112–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia, G; Elwany, A. A review on statistical learning for AM process mapping. J Manuf Sci Eng. 2014, 136, 060801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.T. Multi-length-scale study on the heat treatment response to supersaturated nickel-based superalloys: Precipitation reactions and incipient recrystallisation. Additive Manufacturing 2023, 62, 103389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, Z.A.; Coday, M.M.; Guo, Q.; Qu, M.; Hojjatzadeh, S.M.H.; Escano, L.I.; Fezzaa, K.; Sun, T.; Chen, L. Uncertainties induced by processing parameter variation in selective laser melting of Ti6Al4V revealed by in-situ X-ray imaging. Materials 2022, 15(2), 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panwisawas, C.; Gong, Y.; Tang, Y.T.; Reed, R.C.; Shinjo, J. Additive manufacturability of superalloys: process-induced porosity, cooling rate and metal vapour. Additive Manufacturing 2021, 47, 102339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoussoub, J.N.; Tang, Y.T.; Dick-Cleland, W.J.B. On the influence of alloy composition on the additive manufacturability of Ni-based superalloys. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A 2022, 53, 962–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Distribution of microhardness (HV) for the original 74 LPBF 316L measurements and the surrogate dataset generated using the K-means–KDE sampling approach with SAFE_DIST filtering. A total of 3000 candidate surrogate points were sampled, of which 1311 passed the 5% relative-distance threshold and were retained to avoid proximity leakage. The close overlap between the experimental and surrogate hardness distributions demonstrates that the KDE-based augmentation preserves the physical variability of LPBF hardness while introducing realistic scatter consistent with ±3–5 HV measurement repeatability.

Figure 1.

Distribution of microhardness (HV) for the original 74 LPBF 316L measurements and the surrogate dataset generated using the K-means–KDE sampling approach with SAFE_DIST filtering. A total of 3000 candidate surrogate points were sampled, of which 1311 passed the 5% relative-distance threshold and were retained to avoid proximity leakage. The close overlap between the experimental and surrogate hardness distributions demonstrates that the KDE-based augmentation preserves the physical variability of LPBF hardness while introducing realistic scatter consistent with ±3–5 HV measurement repeatability.

Figure 2.

Scatter plot showing the relationship between the energy-density (ED) descriptor and measured microhardness for all 74 experimental LPBF 316L samples. A gentle inverse trend is visible: increasing ED typically produces larger and hotter melt pools, which cool more slowly and tend to form coarser microstructures, resulting in lower hardness. The overlaid smoothing curve highlights this underlying thermal–microstructural tendency despite the natural scatter present in literature-reported datasets.

Figure 2.

Scatter plot showing the relationship between the energy-density (ED) descriptor and measured microhardness for all 74 experimental LPBF 316L samples. A gentle inverse trend is visible: increasing ED typically produces larger and hotter melt pools, which cool more slowly and tend to form coarser microstructures, resulting in lower hardness. The overlaid smoothing curve highlights this underlying thermal–microstructural tendency despite the natural scatter present in literature-reported datasets.

Figure 3.

Learning curve showing the evolution of training and validation R² as the Random Forest model is trained on increasing fractions of the physics-augmented surrogate dataset while being validated exclusively on the 74 real LPBF 316L measurements. The model demonstrates smooth and stable convergence: even at low training fractions, the validation R² steadily improves, indicating that the surrogate data and physics-based features provide meaningful structure for the model to learn from. As more surrogate samples are included, the training and validation curves gradually approach one another, suggesting well-balanced learning without signs of severe overfitting. This behaviour reflects the smoothness and physical consistency of the surrogate-augmented feature space, which enables reliable generalization to real experimental datapoints.

Figure 3.

Learning curve showing the evolution of training and validation R² as the Random Forest model is trained on increasing fractions of the physics-augmented surrogate dataset while being validated exclusively on the 74 real LPBF 316L measurements. The model demonstrates smooth and stable convergence: even at low training fractions, the validation R² steadily improves, indicating that the surrogate data and physics-based features provide meaningful structure for the model to learn from. As more surrogate samples are included, the training and validation curves gradually approach one another, suggesting well-balanced learning without signs of severe overfitting. This behaviour reflects the smoothness and physical consistency of the surrogate-augmented feature space, which enables reliable generalization to real experimental datapoints.

Figure 4.

Two-dimensional contour map showing the predicted microhardness distribution across the laser power–scan speed (P–v) space at a fixed spot size. The map displays smooth and physically interpretable gradients: higher hardness values appear mainly in regions with higher power and moderately lower scan speeds, where sufficient thermal energy supports stable melting and refined microstructural development. In contrast, low-power and high-speed conditions correspond to lower hardness, reflecting insufficient heat input and reduced melt-pool stability. The continuous contours indicate that the surrogate-Guided model captures the underlying LPBF thermal sensitivity without introducing artificial discontinuities.

Figure 4.

Two-dimensional contour map showing the predicted microhardness distribution across the laser power–scan speed (P–v) space at a fixed spot size. The map displays smooth and physically interpretable gradients: higher hardness values appear mainly in regions with higher power and moderately lower scan speeds, where sufficient thermal energy supports stable melting and refined microstructural development. In contrast, low-power and high-speed conditions correspond to lower hardness, reflecting insufficient heat input and reduced melt-pool stability. The continuous contours indicate that the surrogate-Guided model captures the underlying LPBF thermal sensitivity without introducing artificial discontinuities.

Figure 5.

Feature-importance comparison across models. (a) Random Forest feature importance computed using mean decrease in impurity on the 74-point experimental dataset. Dwell time appears as the dominant contributor, with VED, ED, G, Cooling, and TME providing additional thermal context. (b) Random Forest feature importance computed on the full physics-augmented dataset (experimental + surrogate). Compared to (a), the surrogate-expanded dataset increases the relative contribution of VED and G, indicating improved sensitivity to thermal descriptors. (c) XGBoost feature importance (gain-based) on the full dataset. The gradient proxy G emerges as the most influential feature, followed by Dwell and VED. The difference from RF rankings reflects the models’ different split-evaluation criteria. Across all three sub-figures, the physics-Guided descriptors (VED, ED, G, TME, Cooling) consistently show non-zero importance, confirming that the analytical thermal features meaningfully support the predictive behaviour of both ensemble models.

Figure 5.

Feature-importance comparison across models. (a) Random Forest feature importance computed using mean decrease in impurity on the 74-point experimental dataset. Dwell time appears as the dominant contributor, with VED, ED, G, Cooling, and TME providing additional thermal context. (b) Random Forest feature importance computed on the full physics-augmented dataset (experimental + surrogate). Compared to (a), the surrogate-expanded dataset increases the relative contribution of VED and G, indicating improved sensitivity to thermal descriptors. (c) XGBoost feature importance (gain-based) on the full dataset. The gradient proxy G emerges as the most influential feature, followed by Dwell and VED. The difference from RF rankings reflects the models’ different split-evaluation criteria. Across all three sub-figures, the physics-Guided descriptors (VED, ED, G, TME, Cooling) consistently show non-zero importance, confirming that the analytical thermal features meaningfully support the predictive behaviour of both ensemble models.

Figure 6.

Three-dimensional scatter plot showing the variation of microhardness across the laser power–scan speed domain. The colour gradient reveals a clear trend of increasing hardness with increasing laser power and decreasing hardness with higher scan speeds. The smooth diagonal progression of colours indicates physically consistent thermal behaviour across the dataset, highlighting favourable processing regions at high power and moderate scan speeds.

Figure 6.

Three-dimensional scatter plot showing the variation of microhardness across the laser power–scan speed domain. The colour gradient reveals a clear trend of increasing hardness with increasing laser power and decreasing hardness with higher scan speeds. The smooth diagonal progression of colours indicates physically consistent thermal behaviour across the dataset, highlighting favourable processing regions at high power and moderate scan speeds.

Figure 7.

(a) Parity plot for the full-data model trained on the physics-augmented surrogate dataset and evaluated on all data. The predicted hardness values show strong agreement with the references, yielding an R² of approximately 0.91, with points closely following the 45° parity line. This indicates that the surrogate-expanded dataset enables smooth learning of the underlying process–property trends. (b) Parity plot for predictions evaluated only on the 74 real experimental datapoints, representing true unseen-data generalization. The model achieves an R² of approximately 0.84, showing that despite the small size and multi-source variability of the experimental dataset, the physics-Guided features combined with deterministic surrogate training allow the model to retain reliable predictive behaviour without systematic bias. Across both subfigures, the near-diagonal clustering of points demonstrates stable performance, and the absence of major deviations indicates that the surrogate generation strategy and physics-based descriptors collectively support consistent hardness prediction across the LPBF parameter space.

Figure 7.

(a) Parity plot for the full-data model trained on the physics-augmented surrogate dataset and evaluated on all data. The predicted hardness values show strong agreement with the references, yielding an R² of approximately 0.91, with points closely following the 45° parity line. This indicates that the surrogate-expanded dataset enables smooth learning of the underlying process–property trends. (b) Parity plot for predictions evaluated only on the 74 real experimental datapoints, representing true unseen-data generalization. The model achieves an R² of approximately 0.84, showing that despite the small size and multi-source variability of the experimental dataset, the physics-Guided features combined with deterministic surrogate training allow the model to retain reliable predictive behaviour without systematic bias. Across both subfigures, the near-diagonal clustering of points demonstrates stable performance, and the absence of major deviations indicates that the surrogate generation strategy and physics-based descriptors collectively support consistent hardness prediction across the LPBF parameter space.

Figure 8.

Residual analysis for model performance. (a) Residual histogram for the Random Forest model evaluated on the real experimental datapoints. The residuals are concentrated within a narrow range of approximately ±5 HV, forming a symmetric and unimodal distribution with no heavy tails. This indicates that the model does not exhibit systematic over- or under-prediction and maintains stable error behaviour across the dataset. (b) Residual scatter plot showing predicted hardness versus residual error for the same model. The residuals are randomly dispersed around zero with no observable trend or clustering, confirming the absence of heteroscedasticity or directional bias. The combination of tight spread and random distribution demonstrates that the surrogate-trained model captures the underlying LPBF process–property relationships reliably.

Figure 8.

Residual analysis for model performance. (a) Residual histogram for the Random Forest model evaluated on the real experimental datapoints. The residuals are concentrated within a narrow range of approximately ±5 HV, forming a symmetric and unimodal distribution with no heavy tails. This indicates that the model does not exhibit systematic over- or under-prediction and maintains stable error behaviour across the dataset. (b) Residual scatter plot showing predicted hardness versus residual error for the same model. The residuals are randomly dispersed around zero with no observable trend or clustering, confirming the absence of heteroscedasticity or directional bias. The combination of tight spread and random distribution demonstrates that the surrogate-trained model captures the underlying LPBF process–property relationships reliably.

Figure 9.

Five-fold cross-validation (CV) R² distribution for the Random Forest model trained on the full augmented dataset (experimental + surrogate samples). Each box/violin depicts the spread of fold-wise R² values, with individual folds shown as scatter points and the median highlighted. The fold-wise R² values remain tightly grouped in the range 0.855–0.875, indicating excellent stability across different training–testing partitions. The narrow distribution reflects the well-behaved statistical structure of the augmented dataset and confirms that the physics-Guided features enable robust, repeatable learning behaviour without overfitting.

Figure 9.

Five-fold cross-validation (CV) R² distribution for the Random Forest model trained on the full augmented dataset (experimental + surrogate samples). Each box/violin depicts the spread of fold-wise R² values, with individual folds shown as scatter points and the median highlighted. The fold-wise R² values remain tightly grouped in the range 0.855–0.875, indicating excellent stability across different training–testing partitions. The narrow distribution reflects the well-behaved statistical structure of the augmented dataset and confirms that the physics-Guided features enable robust, repeatable learning behaviour without overfitting.

Table 1.

Sample of 10 LPBF 316L Experimental Datapoints (from Literature).

Table 1.

Sample of 10 LPBF 316L Experimental Datapoints (from Literature).

| S. No. |

Laser Power (W) |

Scan Speed (mm/s) |

Spot Size (µm) |

Microhardness (HV) |

| 1 |

300 |

1000 |

200 |

248.3 |

| 2 |

200 |

800 |

70 |

239.2 |

| 3 |

200 |

1200 |

100 |

223.7 |

| 4 |

280 |

1200 |

100 |

238.9 |

| 5 |

180 |

1000 |

200 |

217.0 |

| 6 |

220 |

1100 |

80 |

231.0 |

| 7 |

250 |

900 |

100 |

248.0 |

| 8 |

320 |

1300 |

90 |

263.7 |

| 9 |

150 |

700 |

50 |

201.0 |

| 10 |

210 |

800 |

60 |

210.5 |

Table 2.

Summary of engineered features, their units, and physical interpretation.

Table 2.

Summary of engineered features, their units, and physical interpretation.

| Feature Name |

Symbol |

Units |

Definition / Formula |

Physical Meaning |

| Laser Power |

|

W |

— |

Energy supplied by the laser to the powder bed. |

| Scan Speed |

|

mm/s |

— |

Rate at which the laser moves across the powder bed. |

| Spot Size |

|

µm |

— |

Laser beam diameter influencing melt pool width and gradient. |

| Spot Area |

|

mm² |

Derived |

Area over which laser energy is distributed. |

| Energy Density Proxy |

|

J/mm³ (proxy units) |

Derived |

Heat input per unit length/area; correlates with melt pool size and cooling rate. |

| Rosenthal Gradient Proxy |

|

Gradient (proxy units) |

Derived |

. |

| TME (Thermo-Mechanical Efficiency) |

|

Proxy units |

Derived |

Measures effective energy per unit melt cross-section. |

| Microhardness |

HV |

HV |

— |

Target property; reflects solidification behaviours and microstructural refinement. |

Table 3.