1. Introduction

Urban regeneration has emerged as a primary strategy for contemporary cities to address physical deterioration, restructure commercial districts, and strengthen their competitive advantage [

1]. These initiatives have increasingly targeted traditional food markets as a tool for revitalizing central neighborhoods, reshaping local identities, and enhancing urban attractiveness [

2,

3]. While such interventions are often framed as necessary modernization, they frequently alter the social, economic, and cultural roles that markets have historically played in cities [

4]. In Southeast Europe, and particularly in post-socialist urban contexts, market reconstructions reveal broader tensions between neoliberal policy orientations, public distrust in institutions, and the persistence of informal economic practices.

The role and identity of marketplaces have evolved over time, often influenced by changing consumer preferences [

5,

6,

7], competition from supermarkets [

8], as well as urban development pressures and a desire to revitalize urban spaces [

3,

9,

10]. These factors have prompted cities to reconsider the purpose and design of marketplaces in order to ensure their continued relevance and economic success. Local authorities aim to improve the attractiveness and sustainability of the market by implementing a modern and more regulated setting [

2,

5]. Consequently, market reconstruction is often driven by the goal of attracting more visitors, encompassing both local residents and tourists, to increase profits [

9,

11].

Although food markets have been widely studied as historical institutions, socio-cultural spaces, and elements of urban food systems, there is limited empirical research on how contemporary regeneration projects reshape the social, spatial, and economic functions of markets in post-socialist cities. Existing studies on market modernization focus largely on Western European cases, where regeneration often produces gentrification, commercial diversification, or tourism-oriented transformations [

4,

12,

13,

14,

15]. However, the dynamics of market transformation in post-socialist contexts, characterized by hybrid informal economies, fragile vendor livelihoods, and legacies of socialist governance, remain insufficiently understood.

In Serbia, despite the cultural and economic importance of open-air markets [

16,

17], scholarship has not systematically examined how recent market reconstructions affect local producers, everyday vendor–customer interactions, or the socio-spatial identity of markets. This gap is particularly evident regarding the transformation of open-air markets into enclosed, multi-level commercial complexes that integrate supermarkets, hospitality venues, and diversified retail functions. The socio-spatial implications of such transitions – especially for traditional producers and small vendors – remain underexplored in the post-socialist transition, public distrust, and neo-liberalization.

The transformation of Palilula Market in Belgrade, the capital of Serbia, offers a valuable case for addressing this research gap. Established in the late nineteenth century as an open-air marketplace known for its flexible layout and close interaction between producers and consumers, Palilula Market underwent a complete reconstruction in 2019. The result was a large, enclosed, and tightly regulated facility. Promoted by city officials as a modernization effort aimed at improving comfort, safety, and economic vitality, the project also brought significant changes to the market’s physical structure, economic practices, and social life.

This study examines how modernization-driven regeneration reconfigures spatial practices, supply chains, vendor livelihoods, and alters the cultural and social roles traditionally associated with the marketplace. By positioning Palilula Market within broader discussions on urban regeneration, retail transformation, and post-socialist urban change, the research offers a more nuanced perspective on how modernization impacts traditional market spaces.

2. Theoretical Background

The modernization of marketplaces has long reflected dominant political and economic ideologies. In nineteenth- and twentieth-century Europe, reforms emphasized enclosure, standardization, and improved sanitation – changes seen as necessary to align urban commerce with the values of industrial progress and the bourgeois public sphere [

2,

3,

18]. Today’s regeneration narratives build on this legacy, presenting covered market halls as symbols of efficiency, consumer comfort, and urban competitiveness [

19]. As a result, markets are often selected for redevelopment not just for practical reasons, but because they serve as prominent public spaces where broader visions of modernization can be physically and visibly enacted.

Food markets have historically served as social institutions, embedded in local culture, community ties, and everyday rhythms of urban life [

10]. Their significance arises from various interconnected functions. Local food systems research highlights the importance of markets in supporting small-scale farmers and food entrepreneurs to sell their goods directly to consumers [

20], thus boosting their incomes and supporting sustainable agriculture practices [

21,

22]. Historically, they have served as important gathering places for communities and have been considered the centers of urban life where diverse cultures, tastes, and traditions converge [

16,

23,

24]. As Mehta [

25] emphasizes, such public spaces generate “social life” that cannot be replicated in structured retail environments.

However, in many cities, market transformation is closely tied to broader strategies of retail restructuring [

4]. Growing competition from supermarkets and global retail chains has pressured municipalities to rebrand and “upgrade” traditional markets in order to maintain their relevance [

6,

8]. Such interventions often seek to attract new consumer groups, such as tourists, middle-class residents, or creative city users, by enhancing aesthetic qualities, integrating hospitality uses, or promoting experiential consumption [

26]. In order to enhance the overall experience, transformed markets sometimes incorporate various amenities such as shared seating areas, dedicated spaces for educational activities like workshops and cooking demonstrations, ample parking facilities, and access to WiFi [

2]. In certain instances, markets have even integrated residential spaces for both the general population and specific groups, such as elderly residents [

26,

27].

Research also showed that regeneration often results in processes resembling retail gentrification, i.e., the displacement of traditional vendors through rising rents, corporatized retail models, and the prioritization of higher-value commercial functions [

4,

14]. Several mechanisms contribute to this shift. Modernization projects typically increase fixed costs for vendors, rendering participation unaffordable for lower-income or small-scale traders [

8,

13]. New management structures often bring stricter operating hours, product requirements, or design rules that limit informal practices and diminish flexibility, the character that has long defined traditional markets [

28]. Regenerated markets frequently integrate restaurants, gourmet shops, or specialty products, contributing to “gastrofication” which is a process through which food consumption becomes a lifestyle-oriented, upscale experience [

26,

29]. In addition, the growing presence of large retail chains within regenerated market complexes, which is a common trend across Europe, creates uneven competition, often to the detriment of small-scale vendors [

11,

30]. Together, these shifts reflect a broader “upmarketization” of traditional food spaces, eroding the informal economies and community-oriented practices that once flourished there [

4]. As Balat [

31] notes, such spatial reorganizations frequently shift markets from community-serving institutions to curated commercial destinations targeting middle-class consumers.

In post-socialist cities, modernization processes intersect with unique social histories. Markets in Serbia and across South-Eastern Europe have historically combined formal regulation with deeply rooted informal practices, local agricultural trade, and neighborhood-level sociality [

17,

32]. Following the political and economic transition of the 1990s, these institutions remained important livelihood anchors and spaces of economic resilience [

33].

Recent scholarship highlights that post-socialist market transformations often reflect broader tensions between liberalization, Westernization, and inherited urban cultures [

34]. Modern regeneration projects may therefore disrupt not only economic practices but also socio-cultural identities embedded in market life.

Planning studies in Serbia and the region demonstrate that local authorities increasingly pursue modernization agendas frequently influenced by global urban policies and competitive city narratives that prioritize visual upgrading, commercial diversification, and efficiency [

35,

36,

37]. Thus, analyzing market regeneration in post-socialist Belgrade requires attention to both macro-level governance changes and the micro-level social impacts experienced by vendors, consumers, and neighborhood communities.

2. Materials and Methods

This study employs a qualitative research design to examine how the spatial transformation of Palilula Market has influenced the practices, experiences, and perceptions of market vendors. Given that regeneration processes shape both tangible and intangible dimensions of urban life, a qualitative approach enables an in-depth exploration of the socio-economic and cultural consequences of the market’s reconstruction. The methodology integrates historical analysis, semi-structured interviews, and systematic on-site observations, allowing for a multi-layered understanding of the transformation.

3.1. Historical and Document Analysis

To contextualize the contemporary transformation of Palilula Market, historical documents, archival records, municipal planning materials, and policy documents were reviewed. These materials provided insights into the evolution of the market’s spatial and functional characteristics, the motivations guiding the reconstruction, and the broader urban development discourse within which the intervention was framed. The historical analysis was essential for understanding how the market’s longstanding socio-cultural role contrasts with the objectives and outcomes of its recent transformation.

3.2. Semi-Structured Interviews with Vendors

The core of the empirical research consisted of semi-structured interviews with market vendors who experienced the transition from the open-air to the enclosed market environment. Qualitative research was employed to avoid a uniform attitude for every interview, and open-ended questions were tailored to the interview context for each participant [

38]. A purposive sampling technique was used to select interview participants to ensure diversity in the sample, representing various vendor types [

39], including long-established stallholders, small producers, sellers of perishable and non-perishable goods, and vendors occupying different spatial zones within the market hall. These interviews aimed to explore the following aspects:

vendors’ experiences prior to the transformation,

perceived changes in economic performance, rental conditions, and customer flows,

shifts in vendor–customer relationships,

assessments of spatial design, regulation, and management after reconstruction,

perceptions of inclusion, exclusion, and identity loss or reinforcement.

This interview format allowed participants to articulate their experiences in their own terms, while enabling comparison across cases. Interviews were conducted in person, typically at vendors’ stalls, ensuring contextual relevance and facilitating rapport. All interviews were transcribed and thematically coded.

The interviews were carried out in July and September 2025. All participants were informed about the purpose of the research and consented to participate voluntarily. To ensure confidentiality, identifying details were removed from transcripts and pseudonyms were used in reporting the findings. The study complied with ethical guidelines for qualitative research involving human subjects.

3.3. On-Site Observations

Systematic observations were carried out after reconstruction, with the goal of documenting spatial practices, patterns of movement, the use of common areas, and interactions between vendors and customers. Observations focused on the physical layout, accessibility, circulation routes, visibility of stalls, and the presence of new amenities introduced during the redevelopment. Particular attention was given to the ways in which the redesigned space supported or constrained traditional market practices, as well as the emergence of new forms of commercial or social behavior. Observational notes were organized into descriptive and analytical categories and later triangulated with interview data.

3.4. Data Analysis

Data from all sources were analyzed through iterative cycles of coding and thematic synthesis [

40]. The analysis proceeded in three stages: 1) open coding of interview transcripts and observational notes to identify recurrent patterns related to spatial change, economic adaptation, social interactions, and identity shifts; 2) axial coding, linking themes to broader processes of urban regeneration, including formalization, commercialization, and spatial reordering; 3) triangulation across interviews, observations, and documentary evidence to validate interpretations and reveal contradictions between official narratives and vendor experiences. This analytical strategy allowed the study to capture both the intended and unintended consequences of the market’s reconstruction.

Table 1 summarizes the data collection methods, sample characteristics, and analytical procedures employed in the study.

4. Results

4.1. The Food Market Network in Belgrade: Historical Context

The evolution of Belgrade’s food market network provides the foundation for understanding the changing role and significance of Palilula Market. Historically, open-air markets functioned as central nodes of food provisioning, social interaction, and informal exchange. Early twentieth-century Belgrade hosted seven principal markets, many of which inherited spatial and functional characteristics from Ottoman-era bazaars [

16,

17,

41]. These spaces were initially characterized by makeshift stalls, minimal infrastructure, and a mix of local producers, artisans, and itinerant vendors [

42]. Despite their modest physical form, markets served as vital urban public spaces where socio-economic relations were anchored.

As Belgrade expanded, the municipal administration formalized and extended the market network. A professionalized Markets Department regulated daily operations, rental fees, hygiene standards, and trading rights, while maintaining preferential access for long-standing local producers and disadvantaged vendors [

42]. Over time, successive political and economic shifts, from the capitalist interwar period to the socialist post-Second World War era, reshaped market operations, vendor composition, and the degree of municipal oversight [

43]. The socialist period, in particular, introduced stricter criteria for participation and prioritized large public agricultural companies, reducing the presence of private traders.

Despite these transformations and the growing dominance of supermarkets in the 21st century, open-air markets have remained popular for daily shopping, maintaining their role as socially embedded and culturally valued urban spaces [

33,

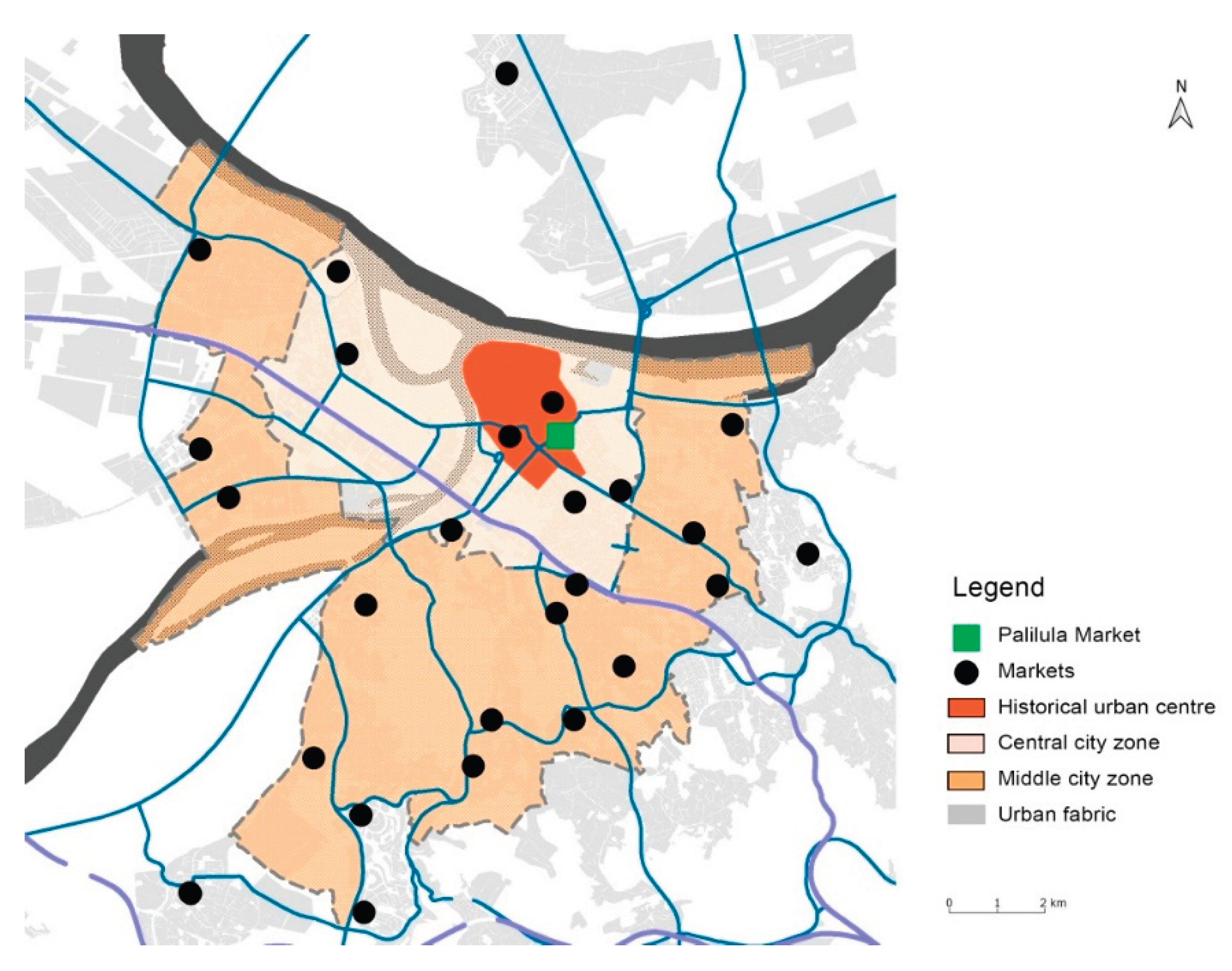

46]. Today, Belgrade’s metropolitan area includes 44 open-air markets of varying scale (

Figure 1) [

44,

45]. Among these open markets, there are also 29 modern farmers’ markets [

47]. The City Administration of Belgrade continues with the policy of city markets’ regeneration, whereby it is considered that certain markets, following the example of Palilula Market, will be transformed from an open to a closed or covered spatial form [

48]. In this context, Palilula Market experience represents an important reference example for future interventions.

4.2. The Transformation of Palilula Market

Palilula Market is one of the oldest and most historically important food markets in Belgrade. Founded in the late 1800s, it originally served as an informal “market site,” a term found in documents from 1888, and was officially recognized as a city marketplace in 1899 [

49]. Unlike other markets, Palilula Market was founded as a private initiative by the local Association “Miloševac” for the Beautification of the Palilula neighborhood, an organization established by local residents themselves. The Association was obliged to submit annual reports on income and expenditure, while any surplus funds were to be reinvested in the improvement of the surrounding neighborhood. This governance model remained in place until 1927, when the market was transferred to municipal control following the expiration of the agreement [

50].

Spatially, the market occupied a triangular plot defined by surrounding streets, a configuration that strongly influenced its internal organization. For decades, Palilula Market consisted primarily of stalls, stands, and wooden cabins arranged on unpaved ground, conditions that generated persistent problems related to hygiene [

51]. During the mid-1930s, the market featured two aged structures accommodating eight shops. In 1932, the municipality took steps to improve conditions in the market by partially concreting its surface and upgrading the water supply and sewage system [

42]. Although these measures brought some improvement to sanitation, issues relating to poor hygiene and overcrowding remained. Archival sources and contemporary press reports indicate that sanitation and spatial congestion remained unresolved issues, frequently debated in municipal council sessions.

Following the Second World War, Belgrade’s authorities introduced a series of measures aimed at reorganizing the city’s food markets as part of broader urban restructuring policies. Palilula Market had undergone several minor interventions since 1948, primarily aimed at enhancing organization and hygiene (

Figure 2a). In 1954, a significant reconstruction effort was undertaken. The market area was divided into two levels, expanding space for food and product stalls while new retail shops were built along the perimeter. This configuration defined the market’s physical structure for several decades (

Figure 2b). Prior to the most recent reconstruction, Palilula Market accommodated approximately 240 stalls within a total area of 3,600 m

2, including nearly 950 m

2 of enclosed built space [

52].

The decision to transform Palilula Market into a closed, contemporary facility marked a critical turning point in its history. Initiated in 2014, the comprehensive reconstruction was justified by the city authorities as a necessary step to improve organization, hygiene, operational efficiency, and the market’s overall public image [

52]. The architectural project was chosen through an open competition of ideas, and the final decision to construct it was determined by a public vote of the citizens, signaling an attempt to legitimize the intervention through participatory mechanisms. Official narratives framed the new building as comparable to modern European markets, combining functionality with a fashionable architectural expression [

53]. However, the transition disrupted market functions, requiring vendors to cease their operations and prompting them to express their dissatisfaction through protests.

Completed and opened in 2019, the new Palilula Market building comprises four levels, including underground storage facilities and a parking garage, a ground-floor food market with a limited number of stalls, modular retail units, cafés, and restaurants, as well as upper levels housing a supermarket and office spaces. Although the total area expanded to 12,689 m2, which is five times larger than before, the number of market stalls was drastically reduced to only thirty, effectively excluding local food producers from traditional market trading [

54]. Public reception of the new building has been mixed, with critical commentary highlighting its resemblance to a shopping center and questioning its compatibility with the historical and spatial character of the surrounding neighborhood [

55,

56,

57].

Figure 3.

Palilula Market after transformation in 2019: (

a) Entrance to the market; (

b) New modular food stalls placed in the central market area (right). Source: [

58].

Figure 3.

Palilula Market after transformation in 2019: (

a) Entrance to the market; (

b) New modular food stalls placed in the central market area (right). Source: [

58].

4.3. Vendors’ Perspectives on the New Market Environment

The reconstruction of Palilula Market involved changes which influenced local vendors in various ways. The interviews conducted with them provided insights into the impacts and their attitudes toward the new market’s spatiality. The interviews were conducted through the lens of spatial transformation of the food market from three perspectives of vendors: the new physical setting, basic economic viability, and social and human interactions.

Across interviews, vendors unanimously acknowledged the advantages of the new indoor setting – improved infrastructure, including protection from weather, better lighting, modern sanitation, and designated storage areas, enhanced working conditions and operational convenience. Many expressed pride in the market’s new appearance and appreciated the year-round functionality. One of the interviewees highlights the stark contrast in working conditions between the previous open market and the new closed market. “Goods and sellers and buyers are now protected. We can operate all year round, all 365 days, regardless of weather conditions. That is the advantage of this indoor market. In the open market, it can be very hot in the summer or cold, windy, and rainy in the winter, making the work difficult or impossible.”

Despite these improvements, vendors consistently emphasized the negative consequences of spatial reorganization. The drastic reduction in the number of stalls limits vendor participation, restricts product diversity, and reduces the presence of traditional local producers. Several vendors highlighted the loss of openness and the diminished ability for spontaneous spatial adaptation that characterized the old market.

While the inclusion of a parking garage improved customer accessibility, the lack of free or discounted parking for vendors was seen as burdensome. Some vendors emphasized that the logistical complexity of loading and unloading products had increased, especially due to traffic congestion and high parking fees.

Economic concerns were among the most frequently cited challenges. Vendors reported that: 1) rent increases of approximately 50%, making participation unaffordable for many former stallholders, 2) a mandatory six-day workweek, which excludes local food producers who depend on agricultural labor, and 3) significant competition from the supermarket located directly above the market, which offers lower prices, accepts payment cards, and regularly promotes discounts.

These changes resulted in lower revenues for many traditional vendors, forcing some to downsize operations or leave the market entirely. Several interviewees noted that decreasing stall occupancy and increasing shop presence have altered the market’s economic landscape, shifting it toward higher-end retail. As in the words of one of the interviewees: “The current arrangement includes a small number of stalls and a larger number of shops around. It would be beneficial to increase the number of stalls in order to foster trade. If the market offered more, it would attract a greater number of people.”

The new environment has reconfigured social relations. While the market remains a site of interaction, vendors noted a decline in spontaneous, informal exchanges typical of open-air markets. They also reported a shift in customer demographics, accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic, with fewer older residents and more sporadic visits by younger customers who prefer retail stores rather than food markets. An important observation was that the growing dominance of cafés and restaurants attracts more affluent consumers but does not necessarily support stallholders’ business. Overall, vendors perceived a weakening of the market’s former community-oriented character, replaced by a more commercialized, consumption-driven ambiance.

5. Discussion

The transformation of Palilula Market aligns closely with long-term trends in the evolution of European and global marketplaces, where urban modernization, retail restructuring, and changing social behaviors reshape the role and identity of traditional food markets. As Stobart and van Damme [

18] argue, markets have historically served as dynamic spaces reflecting broader socio-economic transitions, and their redevelopment often mirrors prevailing ideologies of modernity, regulation, and efficiency. The reconstruction of Palilula Market continues this trajectory, demonstrating how contemporary urban regeneration projects reshape everyday practices, vendor livelihoods, and community identity.

5.1. Regeneration, Modernization, and the Reframing of Market Space

The transformation of Palilula Market into an enclosed, multi-functional commercial complex exemplifies the modernization strategies documented in European cities during the late 19th and 20th centuries [

2,

59]. Much like the market hall reforms in Barcelona, Paris, and Lisbon, the Palilula Market project reflects a governance logic that associates architectural enclosure with improved hygiene, safety, and commercial competitiveness. Donofrio [

3] and Jones, Hillier, and Comfort [

19] emphasize that such interventions are often framed as necessary responses to contemporary retail standards and consumer expectations.

At the same time, modernization carries symbolic weight, as it signals alignment with Western European models and embodies aspirations for urban progress, which is a pattern observed in numerous post-socialist cities [

34]. The rebranding of Palilula Market as a “European-style” marketplace, therefore, resonates with a broader tendency in recent Belgrade planning approaches to deploy architectural upgrading as a symbol of integration into global urban practices [

35,

36,

37]. However, as Morales [

10] argues, successful market modernization must recognize markets not only as commercial infrastructures but also as public institutions and community anchors. The findings indicate that while regeneration improved physical conditions—sanitation, weather protection, and amenities—it also reconfigured the social and cultural dimensions that historically defined Palilula Market’s identity.

5.2. Retail Restructuring, Competition, and Vendor Displacement

The economic pressures experienced by Palilula Market’s vendors reflect wider patterns of retail restructuring documented across Europe and beyond. The rise of supermarket chains and formal retail environments has long been shown to undermine small-scale traders [

8,

30]. In Belgrade, as noted by Todorić et al. [

46] and Lovreta [

33], the increasing dominance of supermarkets has reshaped urban shopping patterns, creating structural disadvantages for open-air vendors.

The introduction of a supermarket within Palilula Market complex intensifies this competition, illustrating what González and Waley [

14] describe as retail gentrification. Guimarães [

13] shows that this process is widespread in regenerated markets in Lisbon, where “modernization” policies privilege gourmet food halls, hospitality venues, and curated retail offerings while marginalizing small-scale producers.

Similar patterns emerge in the Palilula Market case: stall numbers decreased drastically, rental prices doubled, and regulatory regimes tightened. These conditions limit opportunities for traditional local producers and small entrepreneurs, as also observed in marketplaces undergoing redevelopment in Barcelona [

11], Ankara [

6], and Windhoek [

28].

The vendors’ difficulties highlight what Denda et al. [

32] and Petrović et al. [

60] identified as structural vulnerabilities in Serbian marketplaces – limited adaptive capacity, low profitability, and dependence on aging customer bases – which are exacerbated when regeneration projects prioritize commercial diversification over vendor support.

5.3. Changing Consumer Behavior and the Socio-Spatial Reconfiguration of the Market

Palilula Market transformation also reflects shifts in consumer preferences toward convenience, leisure, and regulated shopping environments. Morales [

10] and Ledesma and Giusti [

24] argue that markets increasingly serve dual roles as food provisioning spaces and sites of social interaction, but the form of sociality produced varies significantly depending on spatial design and commercial mix.

In Palilula Market, cafés and restaurants have become primary social attractors, mirroring Cretella and Buenger’s [

26] observations of Rotterdam, where “food as creative city politics” encourages the

gastrofication of market districts. These shifts align with Lütke and Jäger’s [

29] concept of gastro-gentrification, where food-oriented regeneration reorients public life around consumption rather than community exchange.

Vendors’ testimonies reflect this reorientation: while spaces remain socially lively, sociability increasingly revolves around leisure consumption rather than traditional vendor–customer interactions. This shift is consistent with Zukin’s [

7] notion of “consuming authenticity,” in which cultural markers of tradition are aestheticized but stripped of their socio-economic foundations.

5.4. Informality, Cultural Heritage, and Post-Socialist Market Identity

Traditional Serbian marketplaces have historically embodied a hybrid urban culture at the intersection of formality and informality, reflecting patterns noted by Macura [

16], Đokić [

41], Vuksanović-Macura and Todorić [

17]. As Hannah et al. [

20] and Aubry & Kebir [

21] demonstrate globally, open-air markets often facilitate short food supply chains, support small-scale agriculture, and reinforce local identity.

Palilula Market, with its long presence of local smallholders and producers, once served this role richly. Its redevelopment, however, weakens the informal and relational dynamics that underpinned its authenticity. The displacement of local producers parallels findings from Malaysia [

23], Namibia [

28], and Spain [

27], where increased regulation and privatization dilute the cultural and social functions of traditional markets.

The erosion of Palilula Market’s local identity aligns with Zukin’s [

7] argument that modernization projects often transform markets into controlled versions of authenticity which are visually appealing but socially narrowed. This contributes to what Groenendaal [

61] calls the loss of “people power markets,” where community agency and informal negotiation are replaced by formalized managerial control.

Food markets function as vibrant public spaces, offering accessibility, economic inclusion, and informal social interaction in everyday life [

10,

25]. The transformation of Palilula Market brings important questions to the forefront regarding the spatial justice of regeneration outcomes. Although the new market provides improved facilities and more comfortable environments, the redistribution of space strongly favors commercial shops, restaurants, and a supermarket over traditional stalls.

This shift aligns with Denda et al. [

32], who document how market reforms in Serbia often prioritize revenue-generating functions at the expense of low-income users and small vendors. As Borucka et al. [

62] emphasize, sustainable market regeneration must balance economic development with social equity, yet the case of Palilula Market demonstrates the challenges of achieving this in practice. The diminished presence of local vendors, loss of informal sociality, and reduced cultural visibility point to a transformation of Palilula Market from a social infrastructure to a semi-privatized commercial node. This mirrors global market trends where redevelopment produces environments accessible primarily to wealthier consumer groups [

14,

30].

6. Conclusion

The present research has investigated the transformation of Belgrade’s Palilula Market as a paradigmatic case of contemporary urban regeneration in a post-socialist, neoliberal context. Bringing together historical analysis, on-site observation, and interviews with vendors, the study has presented how the transformation of a traditional open-air market into an enclosed, multi-level commercial complex has reshaped the spatial configuration, economic dynamics, and social life of this marketplace. While the redevelopment enhanced infrastructural quality, providing better hygiene standards, protection from the weather, and modern amenities, it also introduced significant challenges for traditional vendors, local agricultural producers, and long-standing patterns of market-based sociability.

These findings indicate that modernization-driven regeneration had both intended and unintended effects. On the one hand, the new building is fully aligned with wider European trends, which frame regeneration in terms of aesthetic upgrading, diversification of uses, and consumer comfort. On the other hand, the move toward higher rents, increased competition from an on-site supermarket, reduced capacity for stalls, and increasing dominance of hospitality and specialty retail tenants generated economic pressures and elements of retail gentrification. These changes undermined the presence of small-scale vendors, ruined the market’s traditional identity, and decreased the availability of space for informal social interaction. From this perspective, Palilula Market serves as an example of how physical improvement may not produce social sustainability, especially for those cities where markets have been significant socio-economic safety nets and cultural anchors.

These issues also involve a number of theoretical contributions. The paper extends the research on market modernization and retail gentrification by underlining how these processes are unfolding within post-socialist urban conditions shaped by informality, hybrid governance, and inherited cultural practices. It further develops the point that regeneration initiatives cannot be understood without consideration of their impact on everyday practices and the relational dimensions of public marketplaces. By showing how modernization interfaces with local economies of vendors, community identity, and social networks that are embedded, the study provides empirical insight into the contested nature of regeneration in transitional urban contexts.

6.1. Policy Implications

These findings have key implications for urban policy and practice in planning. First, traditional market regeneration strategies must incorporate mechanisms for ensuring affordability, such as differential rent systems, subsidized stall fees for local producers, or tiered pricing models to protect low-income vendors. In the absence of such measures, modernization is likely to further entrench socio-economic disparities and lead to a decrease in market accessibility.

Second, municipalities and market management bodies should pursue inclusive processes of planning, productively engaging vendors, producers, and the residents of the local areas in decision-making. Consultation and participatory design may serve to ensure that modernization does not damage those core social and cultural functions that give value to markets.

Thirdly, markets should be plainly recognized within regeneration schemes as social infrastructures, rather than solely as an asset of commercial real estate. Planning frameworks, therefore, need to balance revenue generation with the preservation of cultural heritage, community identity, and everyday sociality.

Fourth, municipal governments need to review the trend of locating supermarkets within traditional markets or right next to them. While these strategies do tend to boost patronage, many such initiatives at once establish a structural disadvantage for small-scale vendors. Policy tools that could reduce such impacts include controls on supermarket floor space, limitations on product category overlap, and incentives for complementary rather than competitive retail mixes.

Lastly, any regeneration in post-socialist cities needs to consider the historical role of informality and the fact that flexible trading practices are still an imperative today. Instead of trying to eliminate informality with inflexible regulation, planners should look to adaptive governance models that accommodate the coexistence of informal and formal systems productively.

6.2. Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations. The research has focused on one market in Belgrade, which restricts generalizability across Serbia or to other post-socialist cities. Vendor interviews provide an essential but partial perspective, as other stakeholders were underrepresented. Limited access to internal planning documentation restricted the analysis of the decision-making processes behind regeneration. Finally, lacking quantitative data also limits testing statistical aspects for the economic impacts of regeneration.

The necessary future research thus involves the use of comparative multi-market designs, incorporates quantitative indicators of economic performance, and includes planners, consumers, supermarket and retail operators, and market management as stakeholders in order to capture the full level of complexity of market transformation processes.

Taken together, such a transformation at Palilula Market highlights the need for regeneration models that transcend aesthetic modernization to socially just, culturally sensitive, and economically inclusive approaches. Traditional markets represent an integral part of urban life in supporting livelihoods, enabling short supply chains, and sustaining everyday sociability. As cities across Southeast Europe and elsewhere now pursue further modernization in terms of marketplace infrastructures, regeneration in the years to come must focus on the long-term social and economic well-being of the communities that rely upon such places, in tandem with physical improvement.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.V-M.; methodology, Z.V-M., J.G., and V.N.K.; validation, M.M.R., E.L. and M.D.P.; investigation, Z.V-M.; resources, S.D., J.G., V.N.K., and M.M.R.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.V-M.; writing—review and editing, Z.V-M., S.D., M.D.P., E.L. and M.M..; visualization, Z.V-M. and M.M.; supervision, M.M.R. and M.D.P.; project administration, J.G., V.N.K., and S.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia through institutional financing of the Geographical Institute “Jovan Cvijić” SASA, Belgrade (Contract No. 451-03-136/2025-03/200172).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Z.V.-M., S.D., M.M.R., and M.D.P. acknowledge funding from the Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia, through institutional financing of the Geographical Institute, “Jovan Cvijić” SASA, Belgrade (Contract No. 451-03-136/2025-03/200172). M.M. acknowledges funding from the Ministry of Science, Technological Development, and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia, through the University of Belgrade—Faculty of Architecture, on the basis of the Agreement for realization, registration number 451-03-68/2024-14/200090. V.N.K. and M.D.P. acknowledge support of the RUDN University (Grant no. 060509-0-000).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ricciardelli, A.; Amoruso, P.; Di Liddo, F. Urban Regeneration: From Design to Social Innovation—Does Organizational Aesthetics Matter? Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

The Markets of the Mediterranean – Management Models and Good Practices; Institut Municipal de Mercats de Barcelona: Barcelona, 2012.

- Donofrio, G. Attacking Distribution: Obsolescence and Efficiency of Food Markets in the Age of Urban Renewal. J. Plan. Hist. 2014, 13, 136–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, S. Contested Marketplaces: Retail Spaces at the Global Urban Margins. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2020, 44, 877–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssens, F.; Sezer, C. Marketplaces as an Urban Development Strategy. Built Environ. 2013, 39, 168–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozuduru, B.H.; Varol, C.; Yalciner Ercoskun, O. Do Shopping Centers Abate the Resilience of Shopping Streets? The Co-Existence of Both Shopping Venues in Ankara, Turkey. Cities 2014, 36, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zukin, S. Consuming Authenticity: From Outposts of Difference to Means of Exclusion. Cult. Stud. 2008, 22, 724–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozcan, G.B. The Transformation of Turkish Retailing: Survival Strategies of Small and Medium-Sized Retailers. J. South. Eur. Balk. 2000, 2, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashkov, R.; Shoval, N. Merchants’ Response towards Urban Tourism Development in Food Markets. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2020, 6, 1089–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, A. Marketplaces: Prospects for Social, Economic, and Political Development. J. Plan. Lit. 2011, 26, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrovski, D.; Crespi Vallbona, M. Urban Food Markets in the Context of a Tourist Attraction – La Boqueria Market in Barcelona, Spain. Tour. Geogr. 2018, 20, 397–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guàrdia, M.; Oyón, J.L. Introduction: European Markets as Makers of Cities. In Making cities through market halls Europe, 19th and 20th centuries; Ajuntament de Barcelona, Institut de Cultura Museu d’Història de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Guimarães, P.P.C. The Transformation of Retail Markets in Lisbon: An Analysis through the Lens of Retail Gentrification. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2018, 26, 1450–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, S.; Waley, P. Traditional Retail Markets: The New Gentrification Frontier? Antipode 2013, 45, 965–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cigale, D.; Lampic, B. Aspects of Tourism Sustainability on Organic Farms in Slovenia. J. Geogr. Inst. Jovan Cvijic SASA 2023, 73, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macura, V. Čaršija i gradski centar. Razvoj središta varoši i grada Srbije XIX i prve polovine XX veka [Bazaar and city center. Development of the center of the town and city of Serbia in the 19th and first half of the 20th century; Gradina, Svetlost: Niš: Kragujevac, Serbia, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Vuksanović-Macura, Z.; Todorić, J. Urbanizacija i Promena Prostornih Obrazaca Trgovine u Srbiji u 19. Veku. In Urbanizacija u Istočnoj i Jugoistočnoj Evropi; Istorijski institut, Državni univerzitet za arhitekturu i građevinu: Belgrade, Nizhny Novgorod, 2019; pp. 197–216. [Google Scholar]

- Stobart, J.; Van Damme, I. Introduction: Markets in Modernization: Transformations in Urban Market Space and Practice, c. 1800 – c. 1970. Urban Hist. 2016, 43, 358–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.; Hillier, D.; Comfort, D. Changing Times and Changing Places for Market Halls and Covered Markets. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2007, 35, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannah, C.; Davies, J.; Green, R.; Zimmer, A.; Anderson, P.; Battersby, J.; Baylis, K.; Joshi, N.; Evans, T.P. Persistence of Open-Air Markets in the Food Systems of Africa’s Secondary Cities. Cities 2022, 124, 103608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubry, C.; Kebir, L. Shortening Food Supply Chains: A Means for Maintaining Agriculture Close to Urban Areas? The Case of the French Metropolitan Area of Paris. Food Policy 2013, 41, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enthoven, L.; Van Den Broeck, G. Local Food Systems: Reviewing Two Decades of Research. Agric. Syst. 2021, 193, 103226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, S. Meeting in the Market: The Constitution of Seasonal, Ritual, and Inter-Cultural Time in Malaysia. Continuum 2011, 25, 619–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledesma, E.; Giusti, C. Why Latino Vendor Markets Matter: Selected Case Studies of California and Texas. J. Am. Plann. Assoc. 2021, 87, 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, V. Evaluating Public Space. J. Urban Des. 2014, 19, 53–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cretella, A.; Buenger, M.S. Food as Creative City Politics in the City of Rotterdam. Cities 2016, 51, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guàrdia, M.; Oyón, J.L.; Fava, N. The Barcelona Market System. In Making cities through market halls Europe, 19th and 20th centuries; Ajuntament de Barcelona, Institut de Cultura Museu d’Història de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2015; pp. 261–296. ISBN 978-84-9850-668-6. [Google Scholar]

- Kazembe, L.N.; Nickanor, N.; Crush, J. Informalized Containment: Food Markets and the Governance of the Informal Food Sector in Windhoek, Namibia. Environ. Urban. 2019, 31, 461–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lütke, P.; Jäger, E.M. Food Consumption in Cologne Ehrenfeld: Gentrification through Gastrofication? Urban Sci. 2021, 5, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.; Hubbard, P. Who Is Disadvantaged? Retail Change and Social Exclusion. Int. Rev. Retail Distrib. Consum. Res. 2001, 11, 267–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balat, P. Socio-Economic and Spatial Re-Organization of Albert Cuyp Market. Built Environ. 1978- 2013, 39, 261–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denda, S.; Petrović, M.D.; Vuksanović-Macura, Z.; Radovanović, M.M.; Ely-Ledesma, E. What Are the Current Directions in the Local Marketplaces Fiscalization? The Online Media Content Analysis. Societies 2024, 14, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovreta, S. Strategija Razvoja Trgovine Grada Beograda [Trade Development Strategy of the City of Belgrade]; Univerzitet u Beogradu – Ekonomski fakultet, Naučno-istraživački centar Ekonomskog fakulteta: Belgrade, Serbia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hilton, M.L. Retailing in Russia and Eastern Europe. In The Routledge Companion to the History of Retailing; Routledge: Abingdon, Oxon; New York, USA, 2018; pp. 396–412. [Google Scholar]

- Vuksanović-Macura, Z.; Gvozdic, M.; Macura, V. Continuous Planning: Innovations from Practice in Stavanger (Norway) and Belgrade (Serbia). Plan. Theory Pract. 2020, 21, 727–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arandelovic, B.; Vukmirovic, M.; Samardzic, N. Belgrade: Imaging the Future and Creating a European Metropolis. Cities 2017, 63, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćorović, D.; Korać, S.T.; Milinković, M. Revisiting the Contested Case of Belgrade Waterfront Transformation: From Unethical Urban Governance to Landscape Degradation. Land 2025, 14, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Qualitative Research from Start to Finish; Research methods; Second edition; The Guilford Press: New York London, 2016; ISBN 978-1-4625-1797-8. [Google Scholar]

- Palinkas, L.A.; Horwitz, S.M.; Green, C.A.; Wisdom, J.P.; Duan, N.; Hoagwood, K. Purposeful Sampling for Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis in Mixed Method Implementation Research. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2015, 42, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Lu, Y.; Wang, P. Why Knowledge Sharing in Scientific Research Teams Is Difficult to Sustain: An Interpretation From the Interactive Perspective of Knowledge Hiding Behavior. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 537833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Đokić, V. Urban Typology: City Square in Serbia = Urbana Tipologija: Gradski Trg u Srbiji; Faculty of architecture: Belgrade, 2009; ISBN 978-86-7924-024-8. [Google Scholar]

- Arsenović, M. Beogradske Pijace [Belgrade’s Markets]. Beogr. Opštinske Novine Belgrade Munic. Gaz. 1934, 52, 156–162. [Google Scholar]

- Solujić, Z. Urbanističko-Arhitektonski Aspect. In Beogradske gradske pijace; JKP Gradske pijace: Belgrade, Serbia, 1999; pp. 48–54. [Google Scholar]

- Official Gazette of the City of Belgrade No. 27/2003 General Urban Plan of Belgrade.

- Urbanistički zavod Beograda. Plan Generalne Regulacije Mreže Pijaca Na Prostoru Generalnog Plana Beograda; Urbanistički zavod Beograda: Belgrade, Serbia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Todoric, J.; Yamashkin, A.; Vuksanovic-Macura, Z. Spatial Patterns of Entertainment Mobility in Cities. J. Geogr. Inst. Jovan Cvijic SASA 2022, 72, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, M.D.; Ledesma, E.; Štetić, S.; Trišić, I.; Radovanović, M.M. Lessons Learned from Historical Development and Modern Practice of Marketplaces – Focus on the Serbian Capital City. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2022, 42, 675–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rekonstrukcija Pijaca „Kalenić” i „Bajloni”: Uređivanje Poznatih Beogradskih Tržnica. Available online: https://www.beograd.rs/lat/zivot-u-beogradu/beogradska-riznica/a107823/Rekonstrukcija-pijaca-Kalenic-i-Bajloni.html (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Minutes from the Meeting of the City Council. Beogr. Opštinske Novine Belgrade Munic. Gaz. 1899, 3.

- Novaković, D. Beogradske Pijace [Belgrade’s Markets]. Beogr. Opštinske Novine Belgrade Munic. Gaz. 1930, 48, 1341–1350. [Google Scholar]

- Krstić, V. Proširenja Sadašnjih i Stvaranje Novih Pijaca [Expansion of Existing and Creation of New Markets]. Vreme 1932, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Rekonstrukcija Palilulske Pijace Od Septembra 2017. Available online: https://www.danubeogradu.rs/2017/08/rekonstrukcija-palilulske-pijace-od-septembra-2017 (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Beobuild Uskoro Rekonstrukcija Palilulske Pijace. Available online: https://beobuild.rs/uskoro-rekonstrukcija-palilulske-pijace-p2678.html (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Palilulska Pijaca Ponovo Radi [The Palilul Market Is Open Again]. Available online: https://www.politika.rs/sr/clanak/445014/Palilulska-pijaca-ponovo-radi (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Brod, Titanik Ili Svemirski. Da Li Znate Kakav Je Ovo Objekat Koji Nice Ispod Tašmajdana? Available online: https://www.blic.rs/vesti/beograd/titanik-ili-svemirski-brod-da-li-znate-kakav-je-ovo-objekat-koji-nice-ispod/np4lb0s (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Maldini, S. Dnevnik Zabluda: Palilulska Pijaca Kao Potpuni Nesklad Sa Arhitekturom Beograda. Available online: https://www.novosti.rs/vesti/kultura.71.html:829016-Dnevnik-zabluda-Palilulska-pijaca-kao-potpuni-nesklad-sa-arhitekturom-Beograda (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- Dinčić, J. Palilulska Pijaca Nalik Vasinoj Torti. Available online: https://www.novosti.rs/vesti/beograd.74.html:725908-Palilulska-pijaca-nalik-Vasinoj-torti (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Beogradske Pijace. Available online: http://www.bgpijace.rs/?p=1151 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

-

Making Cities through Market Halls Europe, 19th and 20th Centuries; Ajuntament de Barcelona, Institut de Cultura Museu d’Història de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2015; ISBN 978-84-9850-668-6.

- Petrović, M.D.; Ledesma, E.; Morales, A.; Radovanović, M.M.; Denda, S. The Analysis of Local Marketplace Business on the Selected Urban Case—Problems and Perspectives. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groenendaal, P. People Power Markets. In The City at Eye Level. Lessons for Street Plinths; Eburon Academic Publishers: Delft, the Netherlands, 2016; pp. 76–79. [Google Scholar]

- Borucka, J.; Czyż, P.; Gasco, G.; Mazurkiewicz, W.; Nałęcz, D.; Szczepański, M. Market Regeneration in Line with Sustainable Urban Development. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).