1. Introduction

Public squares play a fundamental role in shaping urban life, providing spaces for commerce and socio-cultural interaction, particularly in central districts where they act as both physical and symbolic hearts of the city. These spaces reflect historical trajectories while responding to contemporary urban dynamics [

1,

2,

3]. In the context of Iranian cities, squares, locally known as “Meydans”, have historically served as instruments for expressing power relations and religious ideologies [

4].

This study presents a comparative analysis of two emblematic squares: Imam Khomeini Square in Hamadan, Iran, and Rynek Główny (Main Market Square) in Kraków, Poland. Despite their vastly different historical origins and planning traditions, both squares have evolved into multifunctional urban spaces at the heart of their respective cities. Imam Khomeini Square is a product of 20th-century modern urban planning imposed on an ancient urban fabric. In contrast, Rynek Główny dates back to the 13th century, having been established and developed as a medieval commercial centre.

By comparing these squares, the paper examines how historical transformations, spatial configurations, and recent urban interventions, particularly those related to pedestrianisation and placemaking, have shaped their current form and function. The study employs a mixed-methods research design, incorporating historical-documentary analysis, literature review, and qualitative field observations grounded in urban theory frameworks, specifically those of Kevin Lynch and Jan Gehl. Rather than conducting empirical behavioural mapping, this research interprets pedestrian presence, spatial use, and socio-cultural dynamics through descriptive observation and contextual analysis.

The findings reveal both shared characteristics, such as the centrality of each square in supporting social interaction, commerce, and heritage identity, and divergent features tied to their urban morphology and governance models. Ultimately, the study contributes to comparative urbanism by demonstrating how culturally distinct urban squares can converge around similar contemporary goals of livability, walkability, and the integration of sustainable heritage.

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Public Squares in Urban Theory

Public squares assume a vital role in urban environments by promoting social interaction and facilitating community development [

5]. In the words of Kevin Lynch (1960), squares can be characterised as essential “nodes” within the urban landscape, serving as focal points for orientation and movement within the city. The spatial configuration of urban structures, including public squares, profoundly impacts their attractiveness and usability, thereby shaping individuals’ movement patterns and social interactions [

7].

Building upon foundational urban theories, it is essential to emphasise the historical role of civic squares as the nucleus of community life. Throughout history, public squares have functioned as central venues for daily activities and commerce, embodying collective memory, cultural heritage, and political expression [

1]. Jan Gehl (2010) distinctly emphasises the significance of these environments in promoting pedestrian activities, cultivating social interaction, and enhancing the vibrancy of urban spaces. The multifunctionality of public squares mirrors the evolving social values of communities and underscores their lasting importance as venues for civic engagement and public discourse.

As society has further developed, the design and utilisation of squares have evolved in accordance with shifting social requirements, spanning from the ancient Greek agoras and Roman forums to Renaissance squares and contemporary urban spaces. Squares have assumed a significant role in political movements, cultural events, and everyday social activities. Their spatial organisation and function are intricately linked to the prevailing form of government and social relations [

9]. Nevertheless, modern urban development has, at times, resulted in the neglect of traditional public spaces and historical contexts, favouring new commercial areas instead [

5]. To achieve the successful design of public squares, it is imperative to incorporate human-centred perspectives and elements that foster social interactions, ultimately contributing to a dynamic and vibrant urban environment [

10].

In line with these evolving functions, recent research underscores the significance of vibrant public spaces in promoting social interaction and urban vitality. Key characteristics of effective public spaces include inclusiveness, engaging activities, comfort, safety, and enjoyment [

5]. The physical and spatial attributes play a crucial role in facilitating social interaction and enhancing human experiences within the public domain [

7]. To improve the quality and functionality of public squares, researchers have advocated for evaluative strategies and assessment frameworks aimed at their revitalisation and enhancement [

5]. Public spaces are increasingly acknowledged as vital components in fostering social interactions and community development, with the success of these spaces relying on local urban communities [

10].

Comprehending contemporary challenges necessitates a reconsideration of historical perspectives. The historical progression of city squares has been the focus of extensive research, examining their origins and transformations in conjunction with urban development. Squares frequently emerged in proximity to religious or administrative edifices, consequently forming the nucleus of urban settlements [

9]. These spaces have undergone considerable changes due to demographic growth, technological advancements, and evolving power dynamics [

4]. The evolution of squares reflects the transition from feudal to capitalist systems, thereby influencing the ideals of the urban landscape and social values [

11]. These characteristics establish a square as a “vital social, economic, and cultural core” of urban space.

Historical examples further exemplify these transformations. Notably, the 19th and 20th centuries experienced substantial urban transformations in numerous cities, particularly within the Ottoman Empire and the Middle East. The Tenzimat reforms of the Ottoman Empire (1839–1876) resulted in the “Europeanisation” of port cities, which introduced modern infrastructure, public services, and innovative urban planning principles [

12]. This process of modernisation significantly modified traditional urban spaces as nation-state policies redefined the relationship between markets and urban centres. In a similar context, between 1805 and 1922, Cairo underwent a transformation from its medieval characteristics to a more contemporary urban form [

13]. The 20th century witnessed additional shifts in urban planning paradigms, initially emphasising car-centric designs, but later reverting to pedestrian-friendly spaces, often drawing inspiration from medieval European city models [

14]. These transformations mirror broader political, economic, and social changes that reconfigured urban landscapes across various regions.

Consequently, contemporary urban interventions in historic centres endeavour to harmonise the past with the present. These interventions may disrupt existing urban fabrics and introduce new spatial orders [

15]. Recent literature analyses the revitalisation of central squares to accommodate modern needs, with walkability and heritage preservation emerging as prominent themes [

16]. The scope of these interventions encompasses enhancements in housing, modernisation of retail spaces, improvements in public areas, and the implementation of walkability schemes [

17]. In response to these challenges, frameworks for assessing urban interventions within heritage contexts have been established, merging place-making theories with traditional urban forms [

15]. The overarching objective is to reconcile spatial development with heritage preservation, adapting historic areas to contemporary lifestyles while safeguarding their cultural significance.

2.2. The Concept of Walkability in Urban Theory and Practice

Walkability has emerged as a fundamental aspect of sustainable urbanism, contributing not only to environmental goals but also to spatial justice and equitable access to public amenities. Research indicates that pedestrian-friendly environments foster inclusive mobility, particularly for children, the elderly, and economically disadvantaged populations [

8]. In urban areas where walkability is prioritised, both physical and psychological barriers to access are reduced, thereby enabling a greater number of individuals to engage in public life. According to Carmona, (2014), well-designed pedestrian zones enhance the sense of belonging and safety, thereby reinforcing public space as an essential democratic urban asset.

Effective walkability projects frequently depend not solely on spatial design but also on coherent municipal policy and robust institutional coordination. For instance, the transformation of Times Square in New York City and Strøget in Copenhagen exemplifies how clear policy objectives, phased implementation, and public-private partnerships can result in enduring success and public endorsement [

19,

20]. Additionally, local governments play a crucial role in maintaining walkable spaces through continuous programming, safety oversight, and integration with public transport systems.

In historic city centres, implementing pedestrianisation has been linked to measurable economic benefits. A study conducted across various European cities revealed that pedestrian zones typically lead to an increase in retail sales ranging from 10% to 25%, as well as a rise in property values in adjacent areas [

21]. Furthermore, walkable areas tend to attract a greater number of tourists, encourage longer visits, and stimulate the adaptive reuse of heritage buildings, thus supporting both cultural and economic sustainability. The effectiveness of such initiatives relies on balancing tourist activity with the needs of local residents to prevent the “museumification” of historic centres.

2.3. Research Gap

While numerous studies have addressed the form, function, and transformation of public squares within European and Islamic contexts, most have employed descriptive methods or single-case analyses, neglecting the integration of established urban theories. Existing comparative research often lacks a theoretical foundation and rarely juxtaposes cases that originate from fundamentally distinct cultural and morphological backgrounds.

This article aims to bridge that gap by utilising Kevin Lynch’s theory of urban legibility and Jan Gehl’s framework for pedestrian-oriented social spaces, applied to two morphologically distinct squares, Rynek Główny in Kraków and Imam Khomeini Square in Hamadan. These theories serve as both analytical tools and interpretive frameworks to evaluate spatial structure, walkability, and socio-cultural functionality. By linking theoretical perspectives with spatial analysis in the context of heritage-sensitive public space design, this study makes a valuable contribution to comparative urbanism.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Questions

This study addresses the following questions:

How have historical developments of the squares influenced their urban morphology and social function?

What role do economic, cultural, and social activities play in shaping their contemporary use?

How do walkability strategies affect spatial quality and urban vitality?

3.2. Methodology

A mixed-methods approach was adopted. Historical analysis included archival research of old maps, urban plans, and policy documents. Qualitative observations were conducted on user behaviour and spatial dynamics based on the theoretical frameworks of Kevin Lynch and Jan Gehl. The literature review covered interdisciplinary academic works related to public spaces, walkability, and urban morphology.

This study did not involve human participants or sensitive data; therefore, ethical approval was not required. No generative AI tools were used beyond minor grammar corrections. All field notes and archival references are available upon request.

4. Case Study Context: Kraków and Hamadan

This section offers the geographical and historical background of the two case studies—Kraków and Hamadan—highlighting their strategic locations, urban continuity, and cultural heritage. Both cities serve as notable historic urban centres in Europe and Asia, respectively. A comparative overview in

Table 1 outlines the main characteristics that shape their spatial development and importance for this study. Their geographical contexts at the regional, national, and urban levels are further illustrated in

Figure 1.

4.1. The Historical Evolution and Urban Form of Rynek Główny Square

The Kraków Rynek Główny (Main Market Square) is recognised as one of the most renowned and largest medieval market squares in Europe [

32]. Following the destruction wrought by the Mongol invasion in 1241, the city underwent significant reconstruction. In 1257, Rynek Główny was officially established according to the principles of Magdeburg Law, featuring a layout of approximately 200 metres by 200 metres and covering an area of around 4 hectares. Consequently, it emerged as one of the most expansive medieval squares in Europe [

33,

34]. The implementation of the Magdeburg Law from the 13th century onwards greatly influenced urban development in Central and Eastern Europe, promoting increased autonomy and standardised legal frameworks across towns. Furthermore, contemporary studies underscore that the widespread adoption of this legal model facilitated a network of cultural and political interconnections among urban centres, thereby strengthening regional cohesion until the 18th century [

34,

35].

The medieval urban plan of Kraków, initiated in 1257 by Prince Bolesław V the Chaste, featured a regular grid layout with a central market square. The design incorporated a network of streets arranged at right angles to the square [

36].

The Rynek (Market Square), embodying a quintessential medieval European urban plan, served as the central hub for commerce and civic activities. Initially, it was populated by wooden pavilions, trading stalls, a Gothic town hall, and a cloth hall (Sukiennice), which facilitated the concentration of the textile trade. This urban planning scheme was prevalent in Silesian cities, where wooden pavilions and masonry structures, such as town halls and cloth halls, played a central role in trade [

37] (see

Figure 2). The evolution of commercial practices within Sukiennice is further illustrated by historical and contemporary interior scenes (see

Figure 3).

The Hanseatic League played a pivotal role in shaping the cultural and economic landscape of medieval Northern Europe. Hanseatic cities displayed a distinctive material signature, characterised by stepped brick architecture, domestic goods, and trade artefacts [

40]. The cultural influence of the Hanseatic League extended into Poland, inspiring urban forms and architectural interpretations in cities such as Kraków [

41]. The main market square in Kraków, a centre for trade and civic life, experienced significant transformations over time [

42]. In Hanseatic cities, religious architecture predominated the urban fabric, with churches profoundly affecting the aesthetics and planning of cityscapes. During the 13th and 14th centuries, the construction of parish churches and chapels played a vital role in shaping the spatial structure and identity of these towns [

43]. Following a fire in the 16th century, the Cloth Hall was reconstructed in the Renaissance style, marking a crucial phase in the architectural evolution of the square. Alongside it, the freestanding Town Hall Tower and the 14th-century St. Mary’s Church emerged as enduring landmarks within the historical landscape of Kraków [

42].

Despite experiencing a decline after the 16th century, the city underwent a significant revival in the late 19th and early 20th centuries [

44]. In the 20th and early 21st centuries, urban planning in Kraków has integrated both traditional and modernist approaches, as evidenced by the development of new neighbourhoods and local squares [

45]. These projects often involve the reshaping and modernisation of public spaces, sparking debates and controversies among architects, planners, and citizens regarding the appropriate form and function of these historic areas [

46].

The square prominently featured significant urban structures, including the Town Hall with its Gothic tower [

37] and the Great Weigh House, which historically served as a facility for weighing goods [

47]. Additionally, churches played an essential role in shaping both the spatial layout and symbolic significance of the square, particularly the Church of St. Mary and the Church of St. Adalbert [

48] (see

Figure 4). The latter is intricately connected to the square itself, situated upon 11th-century foundations that are approximately two metres below the present ground level. Notably, the positioning of these churches, along with others in Kraków, appears to correlate with astronomical calendar lines, indicating a purposeful orientation based on celestial phenomena such as the solar revolution [

49].

Rynek Główny (Main Square) in Kraków has served as the central venue for various civic events and ceremonies throughout history. Between the 15

th and 18

th centuries, the Town Hall not only hosted significant ceremonies, such as council elections and royal tributes, which enabled the city to exert influence in political matters and showcase its grandeur [

50]. Additionally, it functioned as a site for more sombre occurrences, such as public executions, thereby reflecting the intricate social and political dynamics present within urban spaces [

51].

The square experienced considerable transformations, particularly during the 19th and 20th centuries. The medieval Town Hall was dismantled in 1820, leaving only the tower standing, which continues to serve as a vestige of the previous seat of the city government [

45]. Urban planning in Kraków persisted in its evolution, leading to the emergence of new concepts for neighbourhood squares in the 1920s and 1960s, which mirrored the shifting architectural styles and urban design philosophies of the time [

45,

52].

Similarly, other peripheral structures that encumbered the square were removed. Historical records indicate that the Small Weigh House was demolished in 1801 and the Great Weigh House in 1879 (see

Figure 5), as part of initiatives to enhance and monumentalise the Main Market Square in Kraków [

53].

The transformation of urban spaces in Central Europe during the late 19

th and early 20

th centuries exemplified the interplay between nationalist aspirations and modernisation efforts. In Kraków, this process was manifested in the reimagining of the Main Market Square as a monumental open space, with symbolic elements, such as the Adam Mickiewicz monument (see

Figure 6), emerging as focal points of national identity and collective gatherings [

55]. The historic centre of Kraków, including Rynek Główny, was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1978 to acknowledge its outstanding cultural value. This recognition holds particular significance given that the Old Town endured World War II with minimal damage [

56].

Archaeological excavations conducted beneath Kraków’s Main Market Square (Rynek Główny) during the early 21

st century unveiled substantial historical layers, culminating in the inauguration of the Rynek Underground Museum in 2010. This 6,000-square-meter exhibition presents a millennium of Kraków’s history, featuring ancient foundations and artefacts [

32].

The establishment of the Rynek Underground Museum beneath Kraków’s Main Market Square signifies a profound intersection between historical preservation and modern interpretation. This innovative museum serves as a bridge between the past and the present, illustrating how the evolution of Rynek Główny is chronicled in both archival and archaeological records while continuing to function as a dynamic urban node. The history of the square embodies continuity and adaptation; it has maintained its civic and symbolic role for nearly eight centuries [

32,

56]. Noteworthy transformations, including the erection of the Adam Mickiewicz monument in the 19

th century, have introduced additional layers of national significance while reinforcing its position as a public gathering space [

55]. The surrounding architecture, an elegant amalgamation of Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque, and modernist elements, constructs a cohesive urban environment that serves both as a remnant of the medieval city and as a vital, living public space. This spatial and symbolic layering of Kraków’s Main Market Square, shaped through centuries of architectural accretions and evolving civic functions, provides a coherent framework for understanding its enduring significance as a locus of public identity, social interaction, and cultural representation in the 21

st century [

42].

4.2. The Historical Evolution and Urban Morphology of Imam Khomeini Square

Modern urban planning in Iran, particularly the implementation of regular and extensive street plans, was executed during the Pahlavi era (1925–1941) and was significantly influenced by contemporary European urban reforms. These reforms aimed to modernise the urban structure, facilitate transportation, and establish order within traditional Iranian cities [

57]. Hamadan stood as one of the earliest Iranian cities systematically shaped by the modern urban planning initiatives introduced during this period. Before this transformation, the city displayed an organic and traditional urban fabric, predominantly organised around the historical bazaar and its adjacent neighbourhoods. In 1928 (1307 AH), the initial formal design intervention in the city’s modernisation process was implemented when the German engineer Karl Frisch was commissioned to design Hamadan’s central square, thereby marking a pivotal moment in the spatial reconfiguration of the urban core [

58]. In his redesign of Hamadan, a radial-circular street pattern was introduced, rendering it the first city in Iran to embrace such an urban form. The plan was centred around a circular square with several wide streets radiating outward (see

Figure 7). This new layout represented a significant departure from the traditional organic structure of Iranian cities, which had developed historically in response to environmental and socio-cultural conditions [

59].

The establishment of Imam Square (formerly Pahlavi), with a diameter of approximately 120 meters, served as the central point of the city, constructed in a radial-circular pattern from which six main streets branched at angles of 60 degrees to each other, thereby disrupting traditional urban hierarchy and communication patterns. This intervention led to the destruction of historic neighbourhoods, caravanserais, and parts of the traditional Grand Bazaar, thereby altering the city’s morphology and spatial hierarchy [

63]. Unlike the evolutionary changes in English cities that integrated old cores with modern networks, the radical transformations in Iranian cities, such as Hamadan, led to the fragmentation and alienation of historical centres [

64]. The streets are 30 and 35 meters wide, and their lengths from the square to key points in the city vary between 1.5 and 3 kilometres. The main streets connected to the square include Bu Ali Street, Ekbatan Street, Baba Taher Street, Shohada Street, Shariati Street, and Takhti Street. This square, acknowledged as the first example of modern radial urban planning in Iran, remains one of the most significant urban and economic hubs of Hamadan.

During the 1950s, the significance of the square was further enhanced by the construction of the Tomb of Avicenna along one of its axial routes, thereby reinforcing its ceremonial and symbolic status [

65]. The renaming of public spaces in Iran following the 1979 revolution constituted a component of a more comprehensive effort to reconstruct identity and collective memory, emphasising Iran’s Shiite heritage while concurrently eliminating pre-revolutionary national symbols. This process entailed the erasure of the memory of the previous regime and the assertion of Shiite heritage through the nomenclature of streets and public places [

66]. The concept of “square” (Meydan) has historically held a central position in formalising power relations and religious ideologies within Iranian cities [

4]. The renaming and reconfiguration of public spaces play a crucial role in Iran’s ongoing deliberations over national identity and collective memory [

67].

However, in contrast to Kraków’s Rynek, which evolved gradually, Hamadan’s Imam Square signifies a rupture in urban continuity, representing a top-down imposition of modern spatial order at the expense of the historical urban fabric. This led to the creation of a dual structure. At the same time, the traditional bazaar neighbourhood persisted alongside the newly established boulevards, and the square emerged as a centre for modern commerce, administration, and public ceremonies. It also became a prominent site for Ashura mourning, hosting religious gatherings, revolutionary marches, and national celebrations (see

Figure 8). Planned in the 1930s as part of a broader strategy to transform Hamadan into a “little Tehran,” the square embodies the intersection of early modernist urban planning and local political agendas. Despite numerous changes in name and function over the decades, it continues to constitute the city’s geographical and functional core, serving as the most significant urban access point from the centre to the entire city.

5. Present-Day Function and Impact of Walkability

5.1. Rynek Główny (Kraków): Pedestrianisation and Social Vitality

Kraków’s Main Square currently represents a vibrant, pedestrianised public realm that is central to the city’s economy and social life. Having been free of vehicle traffic for decades, and accessible solely by services and horse-drawn carriages, it exemplifies how pedestrianisation enhances urban vitality. Walking fosters sustainable mobility, improves environmental conditions, and enhances the perceived attractiveness of urban spaces [

69]. The Rynek Underground Museum, situated beneath the pavements, attracts millions of visitors annually, particularly during the Christmas and Easter fairs. Furthermore, civic events contribute to maintaining its role as Kraków’s social agora, providing extensive outdoor seating and a safe gathering space, thereby enhancing the quality of urban life. Studies in urban economics indicate that pedestrian areas tend to increase retail revenues and property values [

21].

In the case of Kraków, the enduring popularity of the main square serves as evidence of these beneficial effects. The square further illustrates the adaptive reuse of historical space. For instance, the stalls located on the ground floor of the Cloth Hall currently offer souvenirs to tourists, in contrast to the original function of selling cloth to medieval merchants. Additionally, the historic warehouse spaces beneath the surrounding townhouses have been repurposed as cafés and jazz clubs. The adaptive reuse of historic city centres can foster urban regeneration and sustainable development by integrating cultural heritage with contemporary functions [

70]. A pedestrian-friendly environment enhances this integration of heritage and modern use. This approach has yielded positive socio-cultural impacts, particularly when heritage sites are accessible to both direct users and the local community [

71].

Furthermore, the local government contributes to the maintenance of the square: The Kraków City Council diligently manages the square, overseeing permits for events, maintenance of surfaces and monuments, among other responsibilities, to harmonise its diverse functions. In Kraków, contemporary cultural buildings situated in historic areas have undergone assessments for sustainability, taking into account accessibility, conservation, and aesthetics [

72]. Overall, adaptive reuse strategies can proficiently balance the preservation of cultural heritage with modern urban requirements and economic development.

The resultant urban environment is characterised by a significant degree of walkability and accessibility, presenting a vibrant backdrop for street performances, flower vendors, art exhibitions, and daily cultural rituals, such as the traditional hanja trumpet. These varied activities collectively enhance a rich and dynamic public life (see

Figure 9).

In Kraków’s Rynek Główny, the ample seating, elevated levels of spatial permeability, and visual openness of the square facilitate both stationary and interactive uses. These encompass informal social encounters as well as large-scale civic gatherings, illustrating the principles of an inclusive and participatory public space. The square accommodates both optional and social activities, as described by Gehl, which include spontaneous performances, informal gatherings, and seasonal markets.

5.2. Imam Khomeini Square (Hamadan): Transformation through Pedestrian Projects

Recent studies have investigated the transformation of Imam Khomeini Square in Hamadan, Iran, from a traffic-dominated area to a pedestrian-oriented urban centre. A significant pedestrian project initiated in 2017 has notably enhanced the integrity and connectivity of the square, thereby improving the quality, safety, aesthetics, urban decor, public space, and pedestrian traffic. This renovation has had a positive impact on the vitality of the surrounding streets, as environmental-physical and spatial factors are instrumental in cultivating a dynamic urban environment [

73]. This transformation addresses the historical conflict between vehicles and pedestrians in Iranian cities, particularly in regions with high tourist attractions [

74]. Catalytic projects, such as those executed on central streets in Hamadan, can effectively infuse new life into targeted areas. Bu-Ali and Ekbatan streets have emerged as the most successful exemplars of walkable and user-friendly urban spaces. Moreover, Babataher Avenue has now been included in the Walkability projects (see

Figure 10).

According to research conducted in this field, the impacts of this significant change include:

Urban Life: The phenomena of urban living and social engagement have experienced a notable increase. Residents now frequent the square for evening promenades, socialising with friends, and participating in recreational activities. Additionally, they patronise the archaeological museum situated at the centre of the square, all while being free from the hazards and pollution associated with traffic. Enhancements in lighting and urban aesthetics have significantly contributed to an improved sense of safety (travel literature observes that “everything is here… a residential space where families gather in the square in the evenings”).

Economic Impact: Enhanced pedestrian access is anticipated to result in increased foot traffic for shops located within the adjacent arcades and streets. The Hamadan Bazaar, conveniently connected via Ekbatan and Shohada streets, stands to benefit from this more secure and aesthetically pleasing access to the square, thereby potentially revitalising traditional commerce. Furthermore, new commercial establishments, including cafes, restaurants, street food vendors, and shops offering tourist souvenirs, have emerged around the square, indicative of the economic revitalisation occurring in numerous pedestrian-friendly city centres.

Traffic Management: Vehicles are now systematically redirected around the outer ring or to designated parking lots, resulting in a significant reduction in congestion in the central area. Nevertheless, the current transportation challenges within the market remain unresolved. This initiative necessitated meticulous planning to ensure efficient mobility, as evidenced by the critical role of Hamadan’s six radial boulevards as vital arteries. Furthermore, the municipality has instituted measures to maintain circulation throughout the broader network, thereby mitigating any potential adverse effects resulting from vehicles exiting the square.

Tourism Boom: Hamadan aims to leverage its rich historical heritage, including the ancient remains located near Ekbatan, as well as significant monuments such as Avicenna’s Mausoleum, the Alavian Dome, and Baba Taher’s Tomb. The aesthetically pleasing and pedestrian-friendly Imam Khomeini Square enhances the city’s appeal to visitors. The square now functions as a picturesque focal point, particularly following the addition of sculptures and decorative features that pay homage to Hamadan’s history, along with the recognition of the ancient Hegmataneh Hill as part of the UNESCO World Heritage List.

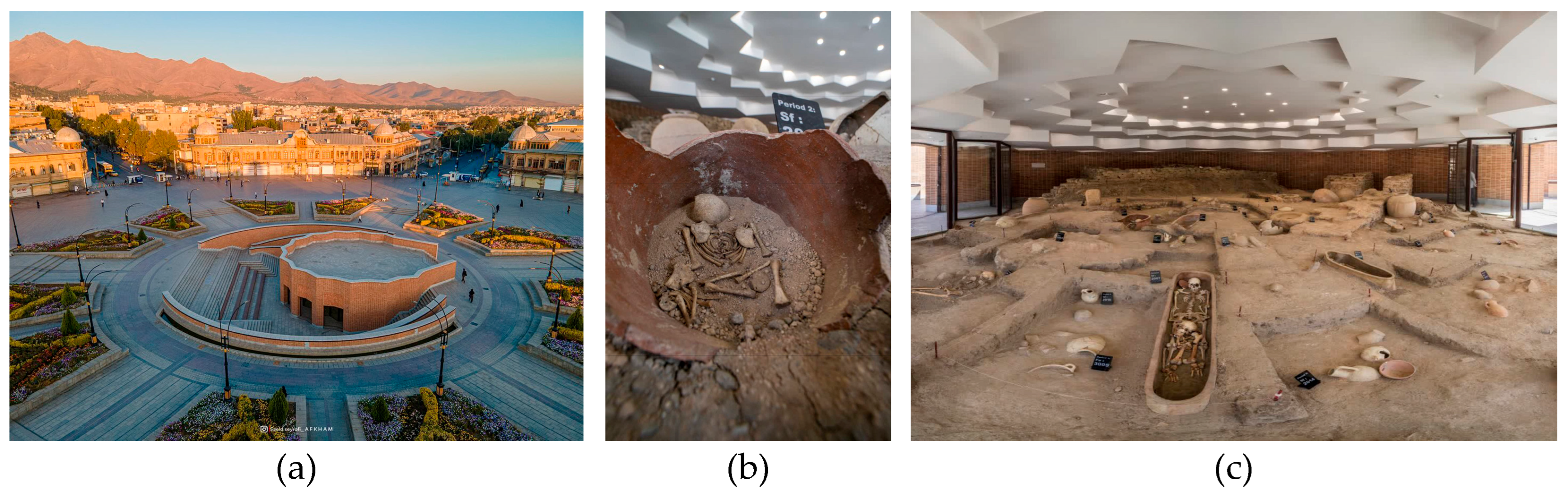

Imam Khomeini Museum: Situated in the central square of Hamadan, this museum reveals significant historical layers pertaining to the city. Archaeological excavations have uncovered three distinct cultural layers, indicating a continuous human settlement from the Median through the Islamic periods. During both the Median and Achaemenid eras, the area served residential purposes, as evidenced by Iron Age III ceramics that were uncovered at the site. In the subsequent Seleucid and early Parthian periods, the site appears to have been abandoned and later repurposed as a burial ground, as confirmed by the discovery of multiple stone sarcophagi. Although historical texts had long associated Hamadan with the Median dynasty, there had been no material evidence to substantiate this claim until recently. Recent excavations in Imam Khomeini Square have provided the first definitive archaeological evidence of Median occupation within the urban core [

75] (see

Figure 11).

Currently, the administration of Imam Khomeini Square necessitates collaboration between municipal authorities and organisations dedicated to cultural heritage. Segments of the adjacent complex are recognised as protected historical monuments and are listed in the National Heritage Register.

Recent research highlights the positive impacts of walkability and the revitalisation of public spaces in historic urban centres across Iran. By redesigning the square into an environment that prioritises people, urban planners in Hamadan have addressed long-standing critiques, particularly those claiming that the modernisation initiatives of the 1930s disrupted socio-economic structures and undermined traditional communal spaces.

Preliminary observations suggest that the Walkability project has effectively re-established the square as the symbolic and functional “heart of the city.” Recent enhancements have improved the legibility and visual hierarchy of the square, aligning with Lynch’s emphasis on spatial clarity and landmark visibility [

6]. These initiatives align with national urban planning trends that aim to enhance livability through pedestrian-focused interventions [

77]. However, sustainable success hinges upon thorough planning, community engagement, and integration into the broader urban framework [

78].

Currently, the square is the venue for a wide array of seasonal, cultural, and religious events, including the Persian New Year (Nowruz), the winter solstice (Yalda), Fire Wednesday (Chaharshanbe Suri), and various Islamic holidays such as Eid al-Adha (Festival of Sacrifice, commemorating Abraham’s devotion) and Eid al-Mab’ath (marking the Prophet Muhammad’s first revelation and the commencement of his prophetic mission in Islam). Furthermore, it accommodates exhibitions of local handicrafts, food festivals, and flower markets that showcase regional biodiversity. (see

Figure 12).

These transformations have reinforced the square’s identity as a social and cultural anchor within Hamadan’s urban fabric. They also illustrate the broader potential of adapting modernist planning legacies to support contemporary urbanism and enhance public life.

Figure 12.

(a) Seasonal flower market in Imam Khomeini Square, Hamadan, during Nowruz celebrations (photo by the author, 2025), (b) traditional street parade featuring folkloric characters [

79], and (c) musical performance by local artists in festive costumes [

80].

Figure 12.

(a) Seasonal flower market in Imam Khomeini Square, Hamadan, during Nowruz celebrations (photo by the author, 2025), (b) traditional street parade featuring folkloric characters [

79], and (c) musical performance by local artists in festive costumes [

80].

5.3. Comparative Observations

Notwithstanding their divergent origins, Imam Khomeini Square and Rynek Główny exhibit multiple functional parallels while also revealing distinctive spatial and managerial attributes. Presented below is a direct comparison across essential dimensions:

5.3.1. Urban Form and Spatial Organisation

Rynek Główny is a substantial rectangular square that is seamlessly integrated into a grid layout. A continuous facade of historic townhouses and notable landmarks along each side defines its precise boundaries. Conversely, Imam Khomeini Square is a circular area situated at the centre of a radial grid. Its borders are less continuous, as they are interrupted by wide street openings. The spatial logic of both squares is centripetal, as they draw individuals toward the centre of the square. At present, both squares primarily function as pedestrian centres; however, the morphology of Rynek Główny naturally facilitates circulation around a central space, whereas the circular shape of Imam Khomeini Square encourages movement along loops and radial pathways (see

Figure 13).

The scale is of considerable significance: both squares occupy approximately the same area in the plan (around 3–4 hectares), yet Rynek’s scale is inherently designed for pedestrian use from the outset. Conversely, Hamadan is segmented by vehicular traffic, exemplified by a 120-meter-diameter circular roadway featuring expansive radiating boulevards. Consequently, the incorporation of street furniture and landscaping in Hamadan has played a pivotal role in mitigating the scale to enhance comfort. Simultaneously, Kraków benefits from its enclosed architectural design and spatial segregation, which are afforded by the structure of its central hall building.

Figure 13.

(a) Aerial comparison of Rynek Główny, Kraków, and (b) Imam Khomeini Square, Hamadan, showing spatial axes. [

81,

82].

Figure 13.

(a) Aerial comparison of Rynek Główny, Kraków, and (b) Imam Khomeini Square, Hamadan, showing spatial axes. [

81,

82].

5.3.2. Accessibility and Connectivity

Both squares exhibit a significant level of accessibility, albeit in distinct manners. The primary square of Kraków is accessible exclusively on foot and by bicycle within the confines of the Old Town. Public transportation, including trams and buses, services the surrounding area, particularly the Park Planty loop, providing multiple access points such as Florianska and Grodzka streets that connect it to the remainder of the city. The accessibility of the square is further enhanced by a well-developed tourist infrastructure, consisting of informative signage, maps, and nearby parking facilities. Additionally, for individuals with limited mobility, the flat and open characteristics of the square, along with the adjacent pedestrian thoroughfares, represent a considerable advantage.

Conversely, Imam Khomeini Square remains a pivotal element within the city’s urban road network, with vehicular traffic redirected into a peripheral ring just before the square. All six radial streets constitute significant urban corridors (e.g., Ecbatan Street leading to the bazaar, Bu-Ali Sina Street, etc.), thus establishing the square as geographically central for accessibility. With the introduction of the new pedestrian layout, parking facilities and taxi stands are situated a short distance away, and the square features a direct connection to the city’s principal commercial streets. While this modification enhances pedestrian safety, it leads to traffic bypassing the immediate centre.

Concerning connectivity, Rynek Główny constitutes a component of a dense pedestrian network within the Old Town. Essentially, every thoroughfare in the vicinity leads to or departs from the square. This distinction is fundamentally attributed to urban form; Kraków’s spatial configuration is based on a grid (allowing for multiple routes). The initiative to enhance walking in Hamadan is beginning to forge secondary connections (such as the pathway to Hegmataneh and the upgraded sidewalks leading to the Grand Mosque and the bazaar), which may ultimately mirror the permeable access exhibited by locations such as Rynek over time.

5.3.3. Cultural and Economic Roles

Both squares serve as vital economic drivers and cultural venues; however, Kraków’s Rynek, with its centuries-old market function, is predominantly focused on tourism and the leisure economy. The presence of souvenir shops, international chain stores housed within historic buildings, hotels located on the square, and the consistent influx of tourists contribute to its global and service-oriented economic profile. In contrast, Hamadan’s Imam Khomeini Square exhibits a more localised economic aspect, being surrounded by a diverse array of shops ranging from traditional bazaar merchants to modern retailers, and it is situated adjacent to the market, which continues to function as a hub of local commerce. Tourism in Hamadan is moderate when compared to that of Kraków, resulting in the square’s commercial activities primarily catering to residents, such as daily shopping, market visits, and essential services. Following the construction of an underground museum in the centre of the square in 2022, which is intended to enhance the city’s attractions, it is projected to emerge as a centre for domestic tourism as well.

Culturally, both squares serve as significant venues for public celebrations and traditions. Rynek Główny is profoundly integrated into Kraków’s cultural calendar, hosting events ranging from medieval trumpet performances (the Hejnał played at noon and broadcast on national radio) to contemporary art festivals, outdoor exhibitions, the iconic Christmas tree, and New Year’s Eve celebrations. Similarly, Imam Khomeini Square is an emerging platform for cultural and religious gatherings. Celebrations in Iran include Nowruz (Persian New Year), Yalda Night (celebrating the winter solstice), events marking the arrival of spring, and official ceremonies such as Army Day parades and Islamic Revolution Victory marches. Informal cultural activities, such as street musicians and flower vendors, are also evident in both squares, although influenced by diverse cultural norms and regulations.

Another point of comparison involves the symbolic significance: Kraków’s main square serves as a representation of Polish national pride and urban continuity; it has been referred to as “the most beautiful urban square in the world” by several guides. Imam Khomeini Square symbolises the early modern Iranian urbanism and is associated with the legacy of Reza Shah’s reforms and post-revolutionary identity (as indicated by its name). Furthermore, local governance strategies exhibit notable differences: the management of Kraków’s Square emphasises heritage preservation and tourism management (such as restrictions on large advertisements and the provision of uniform umbrellas for cafes), whereas Hamadan’s management aims to balance heritage considerations with municipal needs (many of the surrounding buildings are currently protected but have yet to adopt new uses).

Essentially, both squares serve as flexible, open platforms capable of adapting to any collective activity hosted by the city, ranging from high culture, such as open-air opera and film screenings, to folk culture, including craft exhibitions, folk dance performances, and theatrical presentations like “Haji Firuz” in Iran, along with narratives from the “Shahnameh” (the Persian epic of kings), among other events, encompassing both festive and formal celebrations.

5.3.4. Governance and Planning Approaches

The comparative governance of these squares underscores various planning paradigms. Kraków’s Rynek Główny is bolstered by clearly defined heritage conservation policies, as the UNESCO World Heritage status since 1978 necessitates meticulous preservation. The integration of urban planning treats the Old Town as a pedestrian precinct. The involvement of the public in its management is reflected in the utilisation of space, wherein local businesses collaborate in events such as the Christmas market, and citizens articulate their opinions regarding any alterations to the square.

Traditional decision-making processes have historically influenced Hamadan’s square as a result of a singularly centralised plan. The original establishment, enacted by state decree, alongside the recent Walkability initiative spearheaded by municipal authorities, illustrates a consistent approach of authoritative planning interventions. Nonetheless, there are emerging indications of a shift towards community-centred ideation; for example, the advocacy for expanded pedestrian zones correlates with public demand for enhanced street safety and an improved urban environment. Nevertheless, the governance challenges facing Hamadan encompass the enforcement of new traffic regulations, the upkeep of the area to ensure cleanliness and aesthetic appeal in the pedestrian zone, and the potential integration of street vendors or small-scale enterprises to enliven the space.

Another critical factor resides in the manner in which each city coordinates the role of the square within broader urban strategies: Kraków positions Rynek as integral to its cultural economy, emphasising its significance to tourism and the city’s international image. In contrast, Hamadan may incorporate Imam Khomeini Square into its urban regeneration and heritage tourism plans, as indicated by the UNESCO nomination documentation for Hegmataneh, which highlights the square’s influence on socio-economic structures [

31].

To synthesise the comparative governance and planning perspectives of the two squares, key criteria such as spatial form, accessibility, cultural and economic functions, management approaches, and the application of urban theories are summarised. These comparative dimensions are presented in

Table 2, which highlights the convergences and divergences between Imam Khomeini Square in Hamadan and Rynek Główny in Kraków.

5.3.5. Synthesis of Comparative Insights

In conclusion, spatially, the squares of Kraków and Hamadan represent contrasting historical urban forms (organic-medieval versus planned-modernist). Nonetheless, both squares have converged towards a multifunctional, pedestrian-friendly public space model. From a functional perspective, the square of Kraków possesses a more significant international and recreational character, whereas Hamadan sustains everyday local functions alongside emerging civic and tourist purposes. Regarding planning, Rynek Główny exemplifies incremental urbanism and historical preservation, while Imam Khomeini Square represents transformative planning and subsequent adaptation to contemporary needs. Each case presents valuable lessons: Kraków emphasises the importance of preserving and enhancing an inherited public space, whereas Hamadan showcases the adaptation and multiple transformations that occur throughout the lifespan of a square, striving to uphold the significance of its inherited urban heritage. Ultimately, it reveals its identity as a museum, showing that even a machine-centric design can be reimagined to enhance urban life.

6. Application of Urban Theories

6.1. Kevin Lynch’s Theory of Urban Legibility

Kevin Lynch’s foundational theories emphasise the role of urban squares as essential spatial nodes characterised by legibility, identity, and human-scale connectivity [

6,

83]. According to his model, successful squares serve as intersections of routes and promote social interaction through a balance of closure and openness. The five elements he identifies (paths, edges, districts, nodes, and landmarks) are crucial for forming a coherent urban image. Building on Lynch’s concept of imageability (1960), recent studies have expanded the theory to encompass symbolic, cultural, and social meanings in various urban contexts [

84,

85,

86].

6.1.1. The Application of Kevin Lynch’s Theory in This Article

In comparing Imam Khomeini Square in Hamadan and the Main Square in Kraków (Rynek Główny), Lynch’s theory can be applied in the following manner:

Kraków’s Main Square: The square is prominently situated in the city centre, with regular streets providing connectivity to it. It features significant visual landmarks, such as the Church of the Holy Virgin and the Cloth Merchants’ Hall, which contribute to the square’s identity.

Hamadan’s Main Square: The square is characterised by a circular design with radial axes that enhance its legibility. In recent years, the legibility and visual appeal of the square have improved through various sidewalk projects. Additionally, it boasts a crucial visual landmark in the form of a museum.

6.2. Jan Gehl’s Theory of Social Squares and Fields

Jan Gehl’s theory of social squares categorises urban activities into necessary, optional, and social activities, emphasising that high-quality public spaces encourage optional and social activities[

87]. Gehl contends that well-designed squares should be human-scaled, provide seating and interaction spaces, ensure safety, and offer flexibility for various events [

8,

87]. The quality of outdoor spaces significantly influences the extent and character of activities occurring therein, as Gehl discusses in his chapters “Three Types of Outdoor Activities” and “Outdoor Activities and the Quality of Outdoor Space” in Life Between Buildings [

87]. Studies have operationalised Gehl’s theories using social media data to analyse urban spaces at larger scales [

88,

89]. Research indicates that streets designed for social and recreational functions, rather than solely for traffic flow, can enhance social life [

90]. The implementation of Gehl’s principles in urban design has led to an increase in city life and activities, as evidenced by the transformation of Copenhagen from a car-oriented to a people-oriented city centre [

19].

6.2.1. The Application of Jan Gehl’s Theory in this Article

A comparative analysis of Imam Khomeini Square and Kraków Square, grounded in Jan Gehl’s theory, may encompass the following:

Kraków’s Main Square: This square boasts seating areas, open-air cafes, and a range of cultural events, including Christmas markets and street concerts. Consequently, social and voluntary activities thrive in this space.

Hamadan’s Main Square: Before the construction of the sidewalks, this square predominantly served commercial and transit purposes; however, following the implementation of various improvement initiatives, there has been a notable increase in pedestrian presence and social activities. The addition of benches, walkways, and areas conducive to social interaction has transformed the square into a more vibrant urban social space.

6.3. Comparative Summary and Interpretative Conclusion

As summarised in

Table 3, according to Jan Gehl’s theory, Kraków Square serves as a successful example of a sustainable social square. In contrast, Hamadan Square is undergoing a transition into a desirable social space. Initiatives such as enhancing seating areas and organising cultural events may bolster social interactions within Imam Khomeini Square.

Kevin Lynch examines squares in relation to urban legibility, visual cues, and their connection to pathways. Conversely, Jan Gehl analyses squares with a focus on quality of life, social interaction, and dynamic activities. The principles of both theorists are observable within these squares.

Both squares operate as significant urban nodes; however, the differences in their functional scales indicate that Kraków Square functions more as a tourist and cultural space, whereas Hamadan Square embodies a more commercial and local space. According to Kevin Lynch’s theory, both squares possess the characteristics of a desirable urban square.

Through these comparisons, one can comprehend how two squares, one developed through organic urbanism and the other through planned urbanism, can effectively serve as human-centred public spaces. Each square reinforces the city’s identity: Kraków’s Rynek represents a medieval European city square, while Hamadan’s Imam Khomeini Square exemplifies a rare Iranian instance of a large radial square, often likened to a smaller version of Tehran’s renowned squares or even Isfahan’s Naghsh-e Jahan, despite their distinct forms. Noteworthily, both cities have acknowledged the importance of walkability and placemaking, highlighting the synthesis of best practices in urban planning across disparate cultural contexts.

The foregoing comparison substantiates the relevance of urban theories in interpreting the transformations of public squares. In the subsequent section, we will summarise key insights and provide recommendations for policymakers and urban planners.

Table 3.

Comparative Analysis of Kevin Lynch’s and Jan Gehl’s Urban Theories.

Table 3.

Comparative Analysis of Kevin Lynch’s and Jan Gehl’s Urban Theories.

| Conceptual Dimension |

Kevin Lynch – Urban Legibility |

Jan Gehl – Life Between Buildings |

| Main Focus |

Mental image of the city; clarity of urban form |

Human-scale activity; pedestrian experience |

| Key Components |

Paths, edges, districts, nodes, landmarks |

Necessary, optional, and social activities |

| Design Implications |

Improve wayfinding, reinforce landmarks |

Encourage walkability, sociability |

| Relevance to Case Study |

Helps interpret the spatial readability of Rynek Główny and Imam Square |

Explains public use intensity and behavioural patterns |

| Limitations |

Emphasis on the visual dimension |

May underrepresent symbolic or historical meanings |

7. Conclusion and Recommendations

A comparative study of Imam Khomeini Square in Hamadan and Rynek Główny in Kraków illustrates how historic public squares, despite their diverse origins across different eras and cultural contexts, can evolve towards similar contemporary ideals regarding urban livability and vitality while adapting to modern life. Historically, Kraków’s Rynek exemplified the ability of an organically developed square to adapt and thrive over the centuries, fostering commerce, governance, and cultural activities. In contrast, Hamadan’s Central Square demonstrated how modernist planning can significantly transform a city, yielding both positive outcomes (such as enhanced traffic flow, increased security, and a new civic focal point) and negative consequences (including the destruction of the traditional historical fabric and the erosion of the original identity of the location, which, thanks to recent excavations, discoveries, and the establishment of a museum, has reclaimed its latent essence and unveiled its historical identity). An analysis of urban morphology highlighted these disparities; Despite their disparate origins, both case studies validate Kevin Lynch’s theory of legibility and Jan Gehl’s model of social urban spaces, showing how landmark orientation, walkability, and flexible programming are foundational to urban vitality. The study offers empirical evidence that place-making and pedestrian prioritisation are not culturally bound phenomena, but globally transferable principles that enhance both civic identity and social inclusion.

Nonetheless, this study is not without limitations. First, while theoretical frameworks were rigorously applied, the research is grounded primarily in spatial and qualitative analysis without primary behavioural or economic data such as footfall counts, visitor surveys, or GIS-based assessments. Second, the focus on only two case studies—albeit emblematic ones—limits generalizability to broader regional patterns. Future research could expand this comparative lens to include cities from other Islamic and European contexts, or utilise mixed-methods approaches combining spatial syntax, user-experience data, and community-based participatory research to deepen the analysis. Moreover, longitudinal studies could assess how adaptive reuse and walkability projects influence urban identity and community cohesion over time.

Based on the findings, several policy recommendations emerge. First, the integration of heritage and contemporary usage in Kraków’s Rynek Główny exemplifies the notion that preserving historic character, in conjunction with adaptive reuse, fosters the development of sustainable public spaces. Similarly, the city of Hamadan can reflect this principle by preserving and repurposing adjacent historic buildings; for instance, by transforming an antiquated bank into a museum while converting various shops and stores into cafés and restaurants that feature local cuisine, exhibitions, and live music, akin to the practices observed in Kraków.

Secondly, the influence of walkability and place-making on urban outcomes is substantiated by both case studies, which support existing research indicating that walkability significantly enhances urban life and economic activity. In Kraków, the establishment of a car-free square has acted as a catalyst for local tourism and public enjoyment. Similarly, in Hamadan, the development of a nascent pedestrian zone has increased public utilisation and safety in the absence of vehicles, thereby serving as a facilitator for essential, optional, and social activities. It is imperative for municipal governments to continue promoting pedestrian-friendly designs, which may include, but are not limited to, appropriate paving, seating arrangements, shaded areas, high-quality lighting, and facilities for charging electronic devices such as phones and tablets, extending to feeder streets and connections. Place-making initiatives, including the incorporation of public art, as exemplified by Hamadan’s installation of sculptures along the full length of the pedestrian streets of Bu-Ali Sina and Ekbatan leading to the square, or strategic event planning, can enhance the attractiveness of squares as desirable destinations. These methodologies align with the placemaking theories put forth by Jan Gehl, which advocate for the proactive management of public spaces to promote social inclusion.

Thirdly, in balancing traffic and accessibility, the transformation of Imam Khomeini Square necessitated traffic rerouting, thereby underscoring the importance of robust urban traffic models while reclaiming streets for public use. Urban planners must ensure that peripheral roads are competent in accommodating diverted vehicles and that public transportation services are enhanced to compensate for the reduced accessibility of motor vehicles to the central core. The Kraków model serves as a valuable reference for maintaining transportation around the perimeter, with tram stops strategically positioned at a short distance from the square. One recommendation involves the establishment of a “complete streets” scheme surrounding each square; specifically, in the case of Hamadan, it is suggested to continue implementing traffic calming measures along the boulevards adjacent to the square, along with the addition of pedestrian crossings. In the context of Kraków, maintaining the Planty belt forms a multi-faceted ring. In both instances, pedestrian areas achieve optimal performance when integrated with efficient transportation and traffic circulation systems, a success exemplified by the city of Kraków.

Fourthly, spatial equity and inclusive design are of paramount importance, as both squares should be responsive to all segments of society. Kraków is generally recognised for its inclusivity; however, it is crucial to exercise caution to prevent the area from becoming overly tourist-centric at the expense of local necessities, such as maintaining basic services and daily markets, rather than solely focusing on high-end cafes. As a civic space serving a provincial city, Hamadan Square caters to locals from all backgrounds. Urban planners should thoughtfully incorporate amenities for children, including playground elements, to attract families, the elderly, and young individuals. Furthermore, the implementation of universal design principles for accessibility, such as smooth ramps and tactile paving for the visually impaired, is essential, particularly during the transition from a temporary traffic circle to a formal square. These strategies align with the recommendations presented by the Urban Design Scholarship on Inclusive Public Spaces.

Finally, city authorities should view these squares as dynamic entities, with a focus on monitoring and continuous improvement. Regular data collection on foot traffic, user satisfaction surveys, and business performance can guide necessary adjustments to ensure optimal results. For example, if a corner of Hamadan Square is underutilised, the municipality could introduce a kiosk or small café to activate the space. If Kraków’s Rynek experiences issues such as overcrowding during peak seasons, management could implement crowd control measures for significant events or promote the dispersion of activities into secondary squares. The principles of sustainable development also support greening initiatives, such as increasing green spaces in Hamadan.

References

- Carr, S.; Francis, M.; Rivlin, L.G.; Stone, A.M. Public Spacces; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1993; ISBN 9780521359603. [Google Scholar]

- Gehl, J.; Svarre, B. How to Study Public Life; Island Press-Center for Resource Economics: Washington, DC, 2013; ISBN 9781610915250. [Google Scholar]

- Madanipour, A. Public and Private Spaces of the City; Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, 2003. ISBN 0203402855.

- Mehan, A. Blank Slate: Squares and Political Order of City. J. Archit. Urban. 2016, 40, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim Ferwati, M.; Keyvanfar, A.; Shafaghat, A.; Ferwati, O. A Quality Assessment Directory for Evaluating Multi-Functional Public Spaces. Archit. Urban Plan. 2021, 17, 136–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, K. The Image of the City; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, 1960; ISBN 0-262-12004-6. [Google Scholar]

- Salama, A.M.; Remali, A.M.; MacLean, L. Deciphering Urban Life: A Multi-Layered Investigation of St. Enoch Square, Glasgow City Centre. Archnet-IJAR Int. J. Archit. Res. 2017, 11, 137–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehl, J. Cities for People; Island Press: Washington, DC, 2010; ISBN 9781597265744. [Google Scholar]

- Ateş, N. Changes in Historical Urban Squares: Historical Transformation of Beyazıt Square. Kent Akad. 2025, 18, 393–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stauskis, G.; Eckardt, F. Empowering Public Spaces as Catalysers of Social Interactions in Urban Communities. T. Plan. Archit. 2011, 35, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, H.W. The Greening of the Squares of London: Transformation of Urban Landscapes and Ideals. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 1993, 83, 90–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, P.K. Urban Transformation Of Ottoman Port Cities In The Nineteenth Century: Change From Ottoman Beirut, 2006.

- Rania Shafik; Hussam Salama Modernization of Downtown Cairo. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 339–343. [CrossRef]

- Raikhel, Y.L.; Rozhdestvenskaya, E.S. Historical City Center in the XX - XXI Centuries: Back to Pedestrian. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; IOP Publishing, March 1 2020; Vol. 775, p. 012072. [CrossRef]

- Arjomand Kermani, A. Developing a Framework for Qualitative Evaluation of Urban Interventions in Iranian Historical Cores. A+BE Archit. Built Environ. 2016, 10, 1–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowski, Ł.M.; Sumorok, A. Contemporary Revitalization of Public Spaces in Łódź. The Role of Squares, Streets and Courtyards in Creating the Genius Loci Based on the Historical Heritage. Prot. Cult. Herit. 2023, 16, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsas, C.J.L. City Centre Revitalization in Portugal: A Study of Lisbon and Porto. J. Urban Des. 2007, 12, 231–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, M. The Place-Shaping Continuum: A Theory of Urban Design Process. J. Urban Des. 2014, 19, 2–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, D.; Agyeman, J. Sharing Cities: A Case for Truly Smart and Sustainable Cities; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, 2015; ISBN 9780262329712. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, C. Happy City: Transforming Our Lives through Urban Design; Penguin UK, 2013. ISBN 9780141047546.

- Yoshimura, Y.; Kumakoshi, Y.; Fan, Y.; Milardo, S.; Koizumi, H.; Santi, P.; Murillo Arias, J.; Zheng, S.; Ratti, C. Street Pedestrianization in Urban Districts: Economic Impacts in Spanish Cities. Cities 2022, 120, 103468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO Historic Centre of Kraków. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/29/ (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Aḏkāʾi, P.; Iranica, E. HAMADĀN i. GEOGRAPHY. Available online: http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/hamadan-i (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Wikipedia History of Kraków. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Kraków (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Britannica, T.E. of E. Hamadan. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/place/Hamadan (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Chahardowli, M.; Sajadzadeh, H. A Strategic Development Model for Regeneration of Urban Historical Cores: A Case Study of the Historical Fabric of Hamedan City. Land use policy 2022, 114, 105993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britannica, T.E. of E. Krakow. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/place/Krakow#ref633433 (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Kiani, M.Y. Persian Architecture in Islamic Era; 14th (upda.; SAMT: Tehran, Iran; 2019; ISBN 978-964-459-418-2. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, F.W. Trade and Urban Development in Poland: An Economic Geography of Cracow, from Its Origins to 1795; Cambridge University Press. 1994; ISBN 9780521412391. [Google Scholar]

- Piri, S.; Afshariazad, S. Studies of the Caravansary Inside City of Hamadan Qajar Period Case Study Caravansara Haj-Safarkhany. Archaeol. Res. Iran 2016, 6, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO Hegmataneh. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1716 (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Lockwood, A. “In the Footsteps of Kraków’s European Identity” The Rynek Underground Archaeological Exhibit. Pol. Rev. 2012, 57, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyrozumski, J. Kraków Do Schyłku Wieków Średnich / Jerzy Wyrozumski.; Wydaw. Literackie: Kraków, 1992; ISBN 8308001157 83080. [Google Scholar]

- Starzyński, M. Main Market Square as a Stage in the Town Theatre. An Example of Medieval Kraków. In Transformation of Central European Cities in Historical Development (Košice, Kraków, Miskolc, Opava): From the Middle Ages to the End of the 18th Century; Hrehor, Henrich; Pekár, M., Ed.; Univerzita Pavla Jozefa Šafárika v Košiciach: Košice, 2013; pp. 57–64; ISBN 9788081520075.

- Köster, G.; Link, C.; Lück, H. Kulturelle Vernetzung in Europa: Das Magdeburger Recht Und Seine Städte: Wissenschaftlicher Begleitband Zur Ausstellung “Faszination Stadt”; Sandstein Verlag: Dresden, 2018; ISBN 978-3-95498. [Google Scholar]

- Krasnowolski, B. Kraków, Zawichost, Nowe Miasto Korczyn, Skała, Sącz: Plany Urbanistyczne Jako Źródło Do Badań Nad Epoką Bolesława Wstydliwego, Błog. Salomei i Św. Kingi. Nasza Przesz. 2004, 101, 147–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, S.; Lasota, C.; Legendziewicz, A. The Late-Gothic Town Hall in Zielona Góra and Its Remodelings in the 16th and 17th Centuries. Architectus 2011, 1, 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Narodowe Archiwum Cyfrowe Sukiennice Na Rynku Głównym. Available online: https://www.szukajwarchiwach.gov.pl/jednostka/-/jednostka/5896749/obiekty/280697#opis_obiektu (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Mucha, S. Tuchhallen (Mitteldurchgang), Kraków. Available online: https://www.whitemad.pl/en/krakows-cloth-hall-19th-century-reconstruction-of-the-building-gave-it-its-present-form/ (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Gaimster, D. The Hanseatic Cultural Signature: Exploring Globalization on the Micro-Scale in Late Medieval Northern Europe. Eur. J. Archaeol. 2014, 17, 60–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Węcławowicz-Gyurkovich, E. Image of a Hanseatic City in the Latest Polish Architectural Solutions. In Proceedings of the Back to the Sense of the City: International Monograph Book; Centre de Política de Sòl i Valoracions, July 27 2016; pp. 723–735.

- Crosby, A.G. Townscape and Its Symbolism: The Experience of Kraków, Poland. Landscapes 2002, 3, 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozola, S. THE NEW URBAN CONCEPT OF HANSEATIC CITIES OF THE RIGA ARCHBISHOPRIC IN THE 13TH–14TH CENTURIES. Soc. Integr. Educ. Proc. Int. Sci. Conf. 2024, 2, 356–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orton, L.D. The Formation of Modern Cracow (1866–1914). Austrian Hist. Yearb. 1983, 19, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motak, M. The Last Market Square in Krakow?: Two Concepts of a Neighbourhood’s Square. In Proceedings of the ISUF 2020 Virtual Conference Proceedings. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bursiewicz, N. Regeneration of Market Squares in Historic Town Centres: Ideas, Discussions, Controversies. Urban Dev. Issues 2018, 60, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardas-Lason, M.; Garbacz-Klempka, A. Historical Metallurgical Activities and Environment Pollution at the Substratum Level of the Main Market Square in Krakow. Geochronometria 2016, 43, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Węcławowicz, T. Medieval Krakow and Its Churches: Structure and Meanings. Lidé města 2007, 9, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Góral, W. Astronomical and Geodetic Aspects of the Location of Sacred Buildings in Krakow. Geoinformatica Pol. 2019, 18, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyżga, M. Ceremonie Na Ratuszu Krakowskim w XV–XVIII Wieku. Rocz. Dziejów Społecznych i Gospod. 2014, 74, 139–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basson, S. “Oh Comrade, What Times Those Were!” History, Capital Punishment and the Urban Square. Urban Stud. 2006, 43, 1147–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damen, M. The Town as a Stage? Urban Space and Tournaments in Late Medieval Brussels. Urban History 2016, 43, 47–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medieval Heritage Kraków - Cloth Hall and Commercial Buildings - Ancient and Medieval Architecture. Available online: https://medievalheritage.eu/en/main-page/heritage/poland/krakow-cloth-hall/ (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- Wikipedia, C. Great Weigh House. Available online: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Weigh_House (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Golonka-Czajkowska, M. Monuments and Space: Exercises in Political Imagination. Anthropol. Notebooks 2020, 26, 100–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porȩbska, A.; Godyń, I.; Radzicki, K.; Nachlik, E.; Rizzi, P. Built Heritage, Sustainable Development, and Natural Hazards: Flood Protection and UNESCO World Heritage Site Protection Strategies in Krakow, Poland. Sustain. 2019, Vol. 11, Page 4886 2019, 11, 4886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, E.; Floor, W. Urban Change in Iran, 1920-1941. Iran. Stud. 1993, 26, 251–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einifar, A.; Ghaffari, A. Effect of Streets Construction in the Context of Iranian Cities on Transformation from Traditional to Modern Housing, Case Study: Hamadan. Res. J. Environ. Earth Sci. 2014, 6, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheirabadi, M. Iranian Cities: Formation and Development; Syracuse University Press: Syracuse, NY, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre Nomination Text: Hegmataneh; 2024;

-

Geographical Division of the General Staff of the Army A Guide to Hamadan; Geographical Division of the General Staff of the Army: Tehran, Iran, 1953.

- Afshariazad, S. Composite Map of Hamadan Historic Core with Traffic Layer (Based on 1965 National Cartographic Center Map) 2025.

- Jamebozorg, Z.; Najafi, A.; Fakhar, Z. INVESTIGATING THE SPATIAL ORGANIZATION TRADITIONAL NEIGHBORHOODS OF HAMEDAN AND ITS IMPACT ON SOCIAL RELATIONS. Rev. Ciências Humanas 2020, 13, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, K. Continuity and Change in Old Cities: An Analytical Investigation of the Spatial Structure in Iranian and English Historic Cities Before and After Modernisation, University College London (UCL), 1998.

- Nik Khah, M.; Miralami, S.F.; Poursafar, Z. Route Analysis in the Architecture of Museums and Tomb Buildings through Space Syntax Case Study: (Tomb of Nader Shah in Mashhad, Avicenna Mausoleum in Hamadan, and Mausoleum of Poets in Tabriz). J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2021, 20, 640–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashfi, E. The Politics of Street Names: Reconstructing Iran’s Collective Identity. Stud. Ethn. Natl. 2023, 23, 122–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, P.G. The Politics of Iranian Place-Names. Geogr. Rev. 1982, 72, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farshi, H. Ghadir Celebration in Hamadan, Iran. Available online: https://borna.news/files/fa/news/1403/4/5/12473110_618.jpg (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Brownrigg-Gleeson, M.L.; Monzon, A.; Cortez, A. Reasons to Pedestrianise Urban Centres: Impact Analysis on Mobility Habits, Liveability and Economic Activities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeri, A.; Gaspari, J.; Gianfrate, V.; Longo, D.; Pussetti, C. The Adaptive Reuse of Historic City Centres. Bologna and Lisbon: Solutions for Urban Regeneration. TECHNE 2016, 12, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemczewska, Z.E. The Sociocultural Impact of Adaptive Reuse of Immovable Cultural Heritage from the Perspective of Direct Users and the Local Community. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 11, 240–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szpakowska-Loranc, E. Multi-Attribute Analysis of Contemporary Cultural Buildings in the Historic Urban Fabric as Sustainable Spaces—Krakow Case Study. Sustain. 2021, 13, 6126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbazi, M.; Bemanian, M.R.; Oryaninezhad, M.; Ghasemi, N. The Role of Environmental-Physical and Spatial Links Factors in the Vitality of Urban Streets Case Study: The Streets around Imam Khomeini Square in Hamedan. J. Arid Reg. Geogr. Stud. 2018, 9, 74–93. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseinikia, S.M.; Khiabanchian, N.; Rezaei Rad, H. Comparative Assessment of Spatial Indicators of Successful Places Using the Spatial Analysis Method, (Case Study: Hamedan’s Imam Square Pedestrianization, Before and After). Q. Journals Urban Reg. Dev. Plan. 2023, 8, 217–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabani, M.; Ebrahim Zarei, M.; Mollazadeh, K. Classification, Typology and Chronology of Iron Age Pottery at the Site of Meydan in Hamadan. J. Archaeol. Stud. 2023, 15, 107–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afkham, S. Exterior View of Imam Khomeini Museum, Hamadan 2023.

- Kermani, A.A.; Luiten, E. Preservation and Transformation of Historic Urban Cores in Iran, the Case of Kerman. WSEAS Trans. Environ. Dev. 2010, 6, 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- Khaleghi, N. Assessing the Impacts of Pedestrianisation on Historic Urban Landscape of Tehran. Int. J. Archit. Eng. Urban Plan 2018, 28, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafati, A. Welcoming Nowruz with a Festival of Joy and Puppets in Hamedan. Available online: https://newsmedia.tasnimnews.com/Tasnim/Uploaded/Image/1402/12/25/1402122515533351229622574.jpg (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Rafati, A. Musical Performances by Local Artists during Nowruz Celebrations in Hamadan. Available online: https://newsmedia.tasnimnews.com/Tasnim/Uploaded/Image/1402/12/25/1402122515533868429622574.jpg (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Google Maps Rynek Główny, Kraków, Poland – Aerial View (Edited by the Author). Available online: https://www.google.com/maps/place/Rynek+Główny,+Kraków (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Google Maps Imam Khomeini Square, Hamadan, Iran – Aerial View (Edited by the Author). Available online: https://www.google.com/maps/place/Imam+Khomeini+Square,+Hamadan (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Lynch, K. A Theory of Good City Form; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, 1981; ISBN 9780262120852. [Google Scholar]

- Damayanti, R. Extending Kevin Lynch’s Theory of Imageability; through an Investigation of Kampungs in Surabaya- Indonesia, University of Sheffield, 2015.

- Damayantı, R.; Kossak, F. Extending Kevin Lynch’s Concept of Imageability in Third Space Reading; Case Study of Kampungs, Surabaya–Indonesia. A/Z ITU J. Fac. Archit. 2016, 13, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidjanin, P. On Lynch’s and Post-Lynchians Theories. Facta Univ. - Ser. Archit. Civ. Eng. 2007, 5, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehl, J. Life Between Buildings: Using Public Space; 6th Englis.; Island Press: Washington, DC, 2011; ISBN 9781597268271. [Google Scholar]

- Cerrone, D.; López Baeza, J.; Lehtovuori, P.; Quercia, D.; Schifanella, R.; Aiello, L. Implementing Gehl’s Theory to Study Urban Space. The Case of Monotowns. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerrone, D.; Baeza, J.L.; Lehtovuori, P. Optional and Necessary Activities: Operationalising Jan Gehl’s Analysis of Urban Space with Foursquare Data. Int. J. Knowledge-Based Dev. 2020, 11, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q. Lively Streets and Better Social Life, Blekinge Institute of Technology, 2012.

|