1. Introduction

SiC is a hard, brittle, and difficult-to-machine material. During the grinding process, subsurface damage, high-pressure phase transformation, cracks, brittle fracture, residual stress and other issues often occur, which affect the integrity of the machined surface. In particular, chipping at the material edges, surface cracks, and pits are detrimental to the service performance of machined parts, especially their fatigue life. Reducing surface defects during machining or grinding has always been the core of machining research [

1,

2,

3,

4]. The brittle material damage model proposed by Lawn and Wilshaw [

5] is the main basis for analyzing subsurface cracks.

Many scholars have been committed to applying grinding technology to the surface processing of SiC. Kizaki et al. [

6] proposed ultraviolet laser-assisted precision cutting of zirconia ceramics, and the results showed that the introduction of laser significantly reduced the number of macro-cracks and decreased the specific cutting energy by 35%. Azarhoushang et al. [

7] studied the successful application of ultra-short pulse laser in the silicon nitride grinding process, realizing efficient material removal, controllable thermal damage and improvement of material removal rate through laser radiation.

The combination of laser and traditional machining methods has given rise to a variety of hybrid machining approaches, such as Laser and Ultrasonic Vibration Assisted Machining (LVC) [

28], Laser assisted Machining (LAM) [

9,

26], laser assisted drilling [

20] , laser assisted grinding [

26,

27,

28,

29], and laser cutting [

17] . Among these, a typical research method is to conduct scratch tests using single abrasive grains.

The primary objectives of machining are to achieve high surface quality, low power consumption and reduced tool wear [

8,

9,

11,

13,

14]. Research on surface quality focuses on inhibiting subsurface brittle fracture propagation and expanding the plastic deformation zone [

13,

15]. Meanwhile, studies on chip morphology and failure modes are important parts of machining mechanism research [

13,

28]. Based on fracture mechanics theories [

9,

10,

13], the brittle-ductile transition and critical transition scale is the key to surface quality control [

8,

9,

19,

24]. Consequently, relevant research on crack initiation, propagation, prefabricated cracks [

16] and crack control [

24] has been carried out smoothly. Further analysis at the crystal level involves aspects such as slip, stacking, stacking faults and amorphization [

24,

34,

35].

Crack initiation and propagation are usually induced by force/stress [

8,

9,

11,

28], which is not easy to be observed during the machining process. By means of SEM, EDS and white light interferometry, geometric characteristics can be detected, including surface topography [

9,

10,

20,

29], crack distribution and surface defects [

6,

7].

Fracture theory is usually based on indentation fracture experiments. Methods adopted in experiment include indentation tests [

4], control experiments (conventional cutting) [

8,

9], Taguchi methods (for analyzing cutting forces and surface quality under different machining conditions) [

23], Box-Behnken experimental design [

13], response surface methodology (RSM) [

13] and design of experiments (DoE) [

16]. In the experiments, characterizations are usually performed on morphology [

9], surface defects and roughness [

8,

9,

19,

28]. At the microscale, detections are carried out on cracks/microcracks [

8,

9,

10,

11] and surface/subsurface damage [

7,

15]. In addition, measurements or calculations can also be conducted for force/stress [

28], specific grinding energy [

6,

11], hardness [

16], etc.

Experiments are conducted under limited conditions, and the introduction of theoretical analysis helps to generalize and extend the experimental results. In this regard, commonly used theoretical analyses include thermo-mechanical coupling simulation [

12], temperature field simulation [

27], finite element model (FEM) [

28], molecular dynamics simulation [

35], surface roughness model [

13,

23], subsurface damage scale model [

15], grinding force prediction model [

13], tool wear model, etc.

Rao et al. [

31] analyzed material removal mechanism of grinding surfaces during the grinding process of RB-SiC. They found that the grinding surfaces are mainly characterized by brittle pits, abrasive scratches, and plastic grooves. Chen et al. [

35] investigated the variation laws of stress, temperature, dislocation, surface topography, and crystal structure of single-crystal and polycrystalline silicon carbide with changes in grinding speed and grain size through molecular dynamics simulations.

Qu et al. [

38] studied that the material removal of single-crystal 4H-SiC during the grinding process is mainly achieved through plastic deformation, accompanied by brittle fracture.

At present, extensive research on the grinding process of silicon carbide is carried out, covering aspects from the grinding removal mechanism at the micro level to the proposal of various new process methods such as composite grinding. In order to study how to reduce the damage during the silicon carbide processing and improve the processing efficiency, this study adopts engraving laser to modify the surface of silicon carbide, explores the action mechanism of laser irradiation on the surface properties of silicon carbide, controls the surface crack size of laser-modified silicon carbide, restricts the extension and propagation of radial cracks and median cracks during grinding processing, and analyzes the effect of surface cracks of laser-modified silicon carbide on the grinding process.

2. Experimental

2.1. Sample Surface Preparation

A green laser with a wavelength of 532 nm was used as the internal carving light source (PHANTOM Ⅰ laser internal carving machine produced by Han's Laser Group, China). The silicon carbide ceramic sheets produced by the pressureless sintering process (Beilong Electronics Co., Ltd., Guangdong, China) were irradiated. The laser was focused on the processed area below the surface layer of the sample, and the material was ablated at the focal point to modify the processed area of the material surface layer.

Table 1.

Performance parameters of silicon carbide ceramic materials.

Table 1.

Performance parameters of silicon carbide ceramic materials.

| parameters |

values |

| Density(kg·cm-3) |

3.12 |

| Elastic Modulus (GPa) |

415 |

| Vickers Hardness (HV) |

3000 |

| Fracture Toughness (MPa·m1/2) |

4.5 |

| Thermal Conductivity (W/m·k) |

148 |

| Melting Point (℃) |

2700 |

| Poisson's Ratio |

0.24 |

| Thermal Expansion Coefficient() |

4.2 |

A pulsed engraving laser processing system was used to irradiate the surface of silicon carbide ceramics, where the specific parameters of the laser engraving machine are listed in

Table 2. The green laser output by the laser system was expanded by a beam expander, then reflected to a focusing lens via an XY galvanometer. Controlled by a computer, the XY galvanometer swings to enable precise control of the laser focus in the XY two-dimensional directions, thereby regulating the laser beam's processing on the two-dimensional plane. The laser output power was adjusted by changing the output current; the laser defocus value was changed by adjusting the height of the processing platform in the Z-axis direction; the hardness and microcrack size of the laser induced layer were altered by adjusting the spot spacing and scanning times of the laser output.

The hardness of the laser-modified layer on silicon carbide ceramic was measured, and the micro-topography was observed. A digital micro Vickers hardness tester (HVS-1000M, Lead Instrument Co., Ltd., Ningbo, China) was used to measure the microhardness of the laser-irradiated region. A super-depth microscope (VHX-1000, Keyence Corporation, Japan) was employed for crack topography observation. The microscope is equipped with low- and high-magnification lenses, with the low-magnification lens capable of magnifying up to 200× and the high-magnification lens up to 5000×. Additionally, the microscope can perform depth-of-field synthesis on the measured area to automatically generate a 3D surface profile map within the range.

The phase composition of the laser-modified layer on silicon carbide ceramic was analyzed using an X-ray diffractometer (smartlabX, Lihua Saisi Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing), with an angular resolution of 0.001°, to precisely identify the phase composition based on diffraction principles. In the experiment, two silicon carbide ceramic wafers were bonded together with wax to facilitate the observation and analysis of the subsurface conditions and the depth of the laser-affected thermal modification layer, as shown in

Figure 1.

By adjusting the current, the output power of the laser engraving machine can be changed, so the current parameter is used to characterize the laser power. The laser current, number of scans, defocus amount, and spot spacing were selected as the laser process parameters to optimize the control of micro-crack scale in the machined area and its characterized surface hardness.

The thermal-induced cracks were generated by the internal engraving laser on the material surface, which has a significant impact on the material hardness. Material hardness is an extremely important material property index affecting the grinding process, as it will significantly influence the wear degree of the grinding wheel, the grinding force, and grinding efficiency during the process. These results will be presented in another article, and the role of cracks in grinding will be briefly discussed later. Therefore, analyzing the influence of different laser process parameters on the crack scale in the surface layer of silicon carbide ceramics and applying these findings to the relevant grinding process are of paramount importance for improving the grinding efficiency of silicon carbide ceramics, reducing the grinding force, and minimizing surface defects during the grinding process.

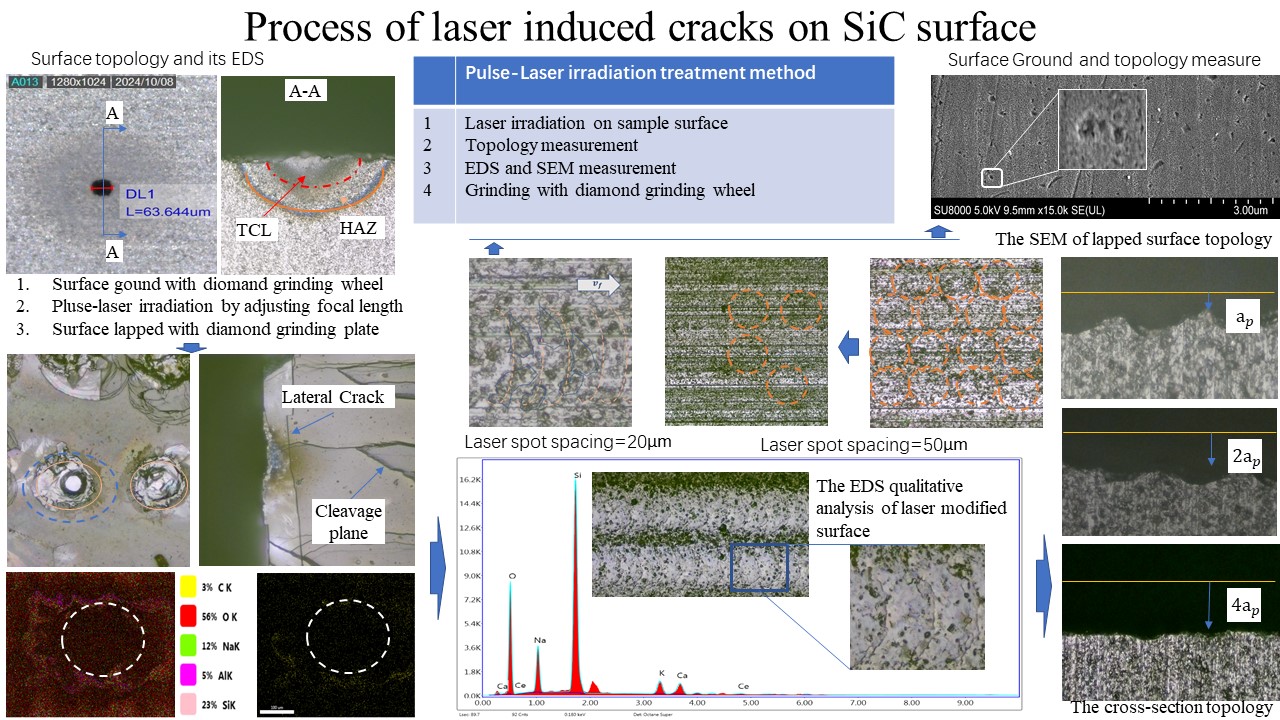

Figure 2.

Crack Characteristics of SiC Ceramic Surface Layer. (a) Ground surface with laser spot measured. (b) cross-section of (a). (c) hardness of sample measured by Vickers hardness tester. (d) correlation surface of sample after lapping. (d) another correlation surface of sample after lapping.

Figure 2.

Crack Characteristics of SiC Ceramic Surface Layer. (a) Ground surface with laser spot measured. (b) cross-section of (a). (c) hardness of sample measured by Vickers hardness tester. (d) correlation surface of sample after lapping. (d) another correlation surface of sample after lapping.

2.2. Grinding Experiment Scheme

To verify that the laser modification method for ceramic surface layers can effectively reduce grinding force and prevent crack propagation, a high-speed precision engraving machine (Mikael 300Q, Mikael CNC Technology Co., Ltd., Guangdong, China) was used with a 400-mesh diamond electroplated grinding head. The grinding test bench and abrasive tool are shown in

Figure 3.

A dynamometer (KWR75, Kunwei, Technology Co., Ltd., Guangzhou) was used to measure the grinding force during the grinding process, as shown in

Figure 3. Diamond wheel grinding remains the primary grinding method for silicon carbide ceramics. Electroplated grinding wheels offer the advantage of high bonding strength, so an electroplated diamond wheel with an abrasive grain size of 400# and a wheel diameter of 10 mm was selected for the experiment, as detailed in

Table 3.

Grinding force is generally decomposed into three directions: normal grinding force Fn,tangential grinding force Ft, and axial grinding force Fa. However, Fa is usually small and its impact on the machining process can be neglected. In the experiment, the grinding force was measured three times for each set of process parameters. Abrupt signals in the grinding force data were eliminated, and the average value of the grinding force during the stable grinding stage was taken as the final result to avoid the influence of contingency and random errors in the experiment on the test outcomes.

3. Results

3.1. Crack Dimensions

The surface topography of SiC ceramics treated by internal carving laser was shown in

Figure 4. The laser-modified layer consists of pulsed laser spots, thermal cracks layer (TCL) and heat affected zone (HAZ). The diameter d and depth h of thermal cracks layer is a core indicator to evaluate the effect of laser surface treatment, as it reflects the direct influence of laser on the material's surface properties (e.g., surface hardness, fracture toughness).

Additionally, the subsequent grinding process needs to completely remove the TCL and HAZ. Therefore, accurate measurement of the thickness of the thermal cracks layer and the HAZ after laser modification is of great significance for the subsequent grinding experiment.

The cross-sectional topography of silicon carbide was measured, which was influenced with laser parameters including laser current, scanning times, defocus value, and spot spacing. It can be observed that laser parameters have a significant impact on the depths of the thermal cracks layer and the HAZ. When the laser current is 15 A, the depths of the thermal cracks layer are close to that of HAZ. As the laser current increases to 18 A, the boundary between the thermal cracks layer and the HAZ begins to become clear. When the laser current further increases to 21 A and 24 A, due to the increased laser energy density, the surface oxide layer gradually thickens, and a white oxide layer can be clearly observed in the laser-modified zone.

As the number of laser scans times increases from 1 to 4, the depths of the thermal cracks layer and the HAZ gradually increase, while the surface oxide layer also thickens progressively. When the defocus amount increases from 0 mm to 1 mm, the dimension of the thermal cracks zone increases significantly. The reason may be that the focal point of positive defocus is located above the sample surface, where the spot diameter formed by the laser beam on the sample surface is larger than that at the focal point. When the defocus amount is further increased to 2 mm and 3 mm, as the distance between the focal point and the sample surface gradually increases, a large amount of energy dissipates in the air, resulting in a decrease in the effective energy transmitted to the material surface, and the width of the modified zone gradually decreases.

Figure 5.

Dimension measure of the TCL and the HAZ. (a)~(d) the correlation of the dimension of TCL and HAZ with laser power (indexed by laser current). (e)~(h) the correlation of the dimension of TCL and HAZ with scanning times. (i)~(l) the correlation of the dimension of TCL and HAZ with defocus amount. (m)~(p) the correlation of the dimension of TCL and HAZ with spot spacing.

Figure 5.

Dimension measure of the TCL and the HAZ. (a)~(d) the correlation of the dimension of TCL and HAZ with laser power (indexed by laser current). (e)~(h) the correlation of the dimension of TCL and HAZ with scanning times. (i)~(l) the correlation of the dimension of TCL and HAZ with defocus amount. (m)~(p) the correlation of the dimension of TCL and HAZ with spot spacing.

When the spot spacing increases to 90 μm and 120 μm, the depths of the thermal cracks layer are close to that of the HAZ. This may be attributed to the fact that with the increase in spot spacing, the energy absorbed by the material per unit area decreases, leading to reduced thermal accumulation, which in turn results in a significant reduction the HAZ comparable to that of the thermal cracks layer.

When the times of laser scans reaches 4, the silica oxide layer can reach a maximum depth of 20.13 μm, the TCL up to 41.21 μm, and the laser HAZ up to 53.84 μm. Spot spacing affects the energy accumulation effect and the continuity of the scanned area. At small spot spacing, adjacent spots overlap, and the same region is heated by other two pulses spots. Energy accumulation increases the peak temperature, promoting deep thermal diffusion.

3.2. Surface Hardness

Vickers hardness tester with a square pyramid diamond indenter was used to measure the hardness of the laser-modified region. After the hardness tester automatically loaded, held the load, and unloaded, the lengths of the two diagonals of the indentation in the target area were manually calibrated. Subsequently, the hardness tester automatically calculated the corresponding hardness value according to the Vickers hardness empirical formula.

As the laser current increases from 15 A to 24 A, the surface hardness shows a gradual decreasing trend, indicating that the increase in laser current has a significant weakening effect on the material's surface hardness, as shown in

Figure 6a. As the current increases, the laser output power gradually increases, leading to a higher laser energy per unit area. After being transmitted through the optical path and focused onto the silicon carbide surface by the focusing lens, part of the laser energy is absorbed by the material, causing the surface temperature to rise.

The surface hardness of silicon carbide gradually decreases with the gradual increase in the number of laser scans. When the number of scans increases from 1 to 2, the surface hardness of silicon carbide decreases most significantly, while the decreasing trend of surface hardness slows down when the index of scans increases to 3 and 4, shown in

Figure 6b.

3.3. Surface Topography and Composition

Since the powdery ablated products generated on the surface during laser irradiation are insufficient for individual detection, XRD analysis was performed on the entire laser-treated surface of the silicon carbide ceramics after laser irradiation. The overall topography of the sample is shown in

Figure 7a, the characteristic peaks of the SiC matrix are presented in

Figure 7c, and the characteristic peaks of the modified products are illustrated in

Figure 7b.

By comparing the XRD spectra of silicon carbide ceramics before and after laser modification, it is found that prior to laser modification, the characteristic peaks appear at 2θ = 34.061°, 35.597°, 38.268°, 41.383°, 43.253°, 54.581°, 60.024°, 66.654°, 71.651°, 72.327°, 73.513°, and 76.304°. Comparison with the standard PDF card confirms that all these characteristic peaks correspond to the SiC phase, indicating that the main constituent phase of the silicon carbide ceramics before laser modification is the SiC phase. After laser modification, in addition to the aforementioned characteristic peaks, a weak-intensity characteristic peak emerges at 2θ = 23.749°, which is identified as the SiO₂ phase by reference to the standard PDF card. Thus, the main phase generated on the silicon carbide surface after laser modification is the SiO₂ phase.

Surface roughness measurements of the silicon carbide were conducted, as shown in

Figure 7d. The results indicate that when the laser current is 15 A (with low laser power), the surface roughness is 1.452 μm. As the laser current increases to 18 A, the surface roughness rapidly rises to 1.73 μm, and further increases in laser current result in little change in surface roughness. This is because at low laser current, the laser power is insufficient to induce continuous melting of the silicon carbide surface.

3.4. Grinding Process

The presence of surface and subsurface cracks significantly reduces the grinding force. As the laser current gradually increases, both the normal grinding force

Fn and tangential grinding force

Ft decrease progressively. Compared with the control group without laser modification, the grinding forces are reduced to varying degrees, as shown in

Figure 8. The ground surface undergoes further lapping treatment, and its topography is presented in

Figure 8a.

When the laser current is 15 A, the normal grinding force decreases by 2.9% compared with conventional grinding, and the tangential grinding force decreases by 3.2%. This is because the laser energy is relatively low at this point, and the insufficient energy input only induces a weak phase transformation on the silicon carbide surface. The overall hardness and brittleness show no significant reduction, with the material still dominated by its original high-hardness and high-brittleness structure. During grinding, the resistance to abrasive grain penetration and the energy consumption for crack propagation are not significantly reduced, resulting in a small decrease in grinding force.

When the laser current reaches 24 A, both the Fn and Ft drop to the minimum. Compared with the experimental group without laser modification, the normal grinding force is reduced by 17.6% and the tangential grinding force by 22.2%. It can also be observed that the trend of the actual values is consistent with the theoretical values, but the theoretical values are larger than the actual ones. The maximum deviation is 32.1%, the minimum deviation is 5.8%, and the average deviation is 18.6%.

In summary, laser-modified silicon carbide ceramic grinding results in a significant reduction in both normal and tangential grinding forces. With the increase in laser current, the laser power increases, the surface hardness of silicon carbide ceramics continuously decreases, and the corresponding reduction ratio of grinding force gradually increases. The maximum reduction in normal grinding force can reach 17.6%, and that in tangential grinding force can reach 22.2%.

The specific grinding energy under

I,

Vsr was plotted as a dot-line graph. The curves showing the variation of specific grinding energy with laser power (indexed by current) and grinding wheel speed are presented in

Figure 9.

5. Conclusions

The material properties of silicon carbide SiC ceramics changes after laser irradiation, with multiple research sides considered such as surface/subsurface cracks, surface hardness, phase composition, laser-modified layer depth, and surface topography of the laser-modified SiC ceramics.

The order of influence of laser process parameters on the surface crack dimension of SiC ceramics is: laser power (indexed by current) > scanning times > defocus value > spot spacing. Additionally, the surface hardness of laser-modified SiC increases with the increase in laser current and number of scanning passes, while decreasing with the increase in defocus amount and spot spacing, with a maximum reduction of 8.2%.

A large amount of SiO₂ oxide layer is formed on the SiC surface after laser irradiation, with clear ablation groove boundaries. The width of the oxide layer increases with the increase in laser power and times of scanning passes, and decreases with the increase in defocus value and spot spacing. The SiO₂ formed by oxidation has a lower hardness but higher fracture toughness than the SiC phase, which is conducive to improving the grinding conditions of SiC.

Laser irradiation results in the formation of a melting zone, a thermal cracks layer, and a HAZ. The thicknesses of both the thermal cracks layer and HAZ increase with the increase in laser power and scanning times, and decrease with the increase in defocus value and spot spacing. Cracks are concentrated in the laser-modified layer. The maximum depth of the oxide layer reaches 20.13 μm, the laser-modified layer reaches 41.21 μm, and the laser HAZ reaches 53.84 μm.