1. Introduction

In Côte d’Ivoire, cotton is a pivotal component of the rural economy, offering a stable income to over 106.000 farmers. This crop is cultivated from the central region to the northern borders, covering more than 392.000 ha [

1]. However, cotton farming faces several challenges, including soil depletion [

2] and climate change [

3]. In addition, the productivity and quality of cotton are significantly compromised by pests. The pest spectrum is notably diverse and includes sucking insects (aphids, jassids, and whiteflies) and leaf- and carpophagous lepidopterans. The larvae of Lapidoptera (

Helicoverpa armigera,

Diparopsis watersi,

Earias spp.,

Pectinophora gossypiella and

Thaumatotibia leucotreta) are considered the most formidable pests because they directly attack cotton bolls, leading to substantial economic losses [

4,

5]. During the 2022–2023 cotton season, the invasive leafhopper

Amarasca biguttula biguttula Ishida [

6] emerged on cotton crops in Côte d’Ivoire, causing production losses exceeding 50% [

7], which disrupted plant protection strategies that were previously focused on bollworms (

Helicoverpa armigera). Consequently, jassids have become a critical factor in plant protection programs. During the cotton season, significant attention has been devoted to managing this new threat, leading to the neglect of larvae of Lepidoptera and their subsequent resurgence [

8]. This increased focus on managing

A. biguttula may create a new imbalance within the pest complex. Indeed, specific insecticides, such as flonicamid, used on leafhoppers are not effective against Lepidoptera larvae [

9]. Furthermore, in the context of

A. biguttula invasion, there are no updated data on the abundance of Lepidopteran pests and the level of damage they cause in different cultivation areas of Côte d’Ivoire. However, this knowledge is essential for developing effective management strategies for all pests. The present study aimed to evaluate the overall impact of the damage caused by the larvae of

Diparopsis watersi,

Helicoverpa armigera,

Earias spp.,

Pectinophora gossypiella, and

Thaumatotibia leucotreta on cotton cultivation in Côte d’Ivoire, within the context of jassid (

A. biguttula biguttula) invasion. The specific objectives were to determine the annual and spatial variations of these pests and to assess their impact on the health status of cotton bolls and seed cotton yield.

To address these objectives, a detailed study spanning various cotton-producing regions was conducted, as described in the following sections.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

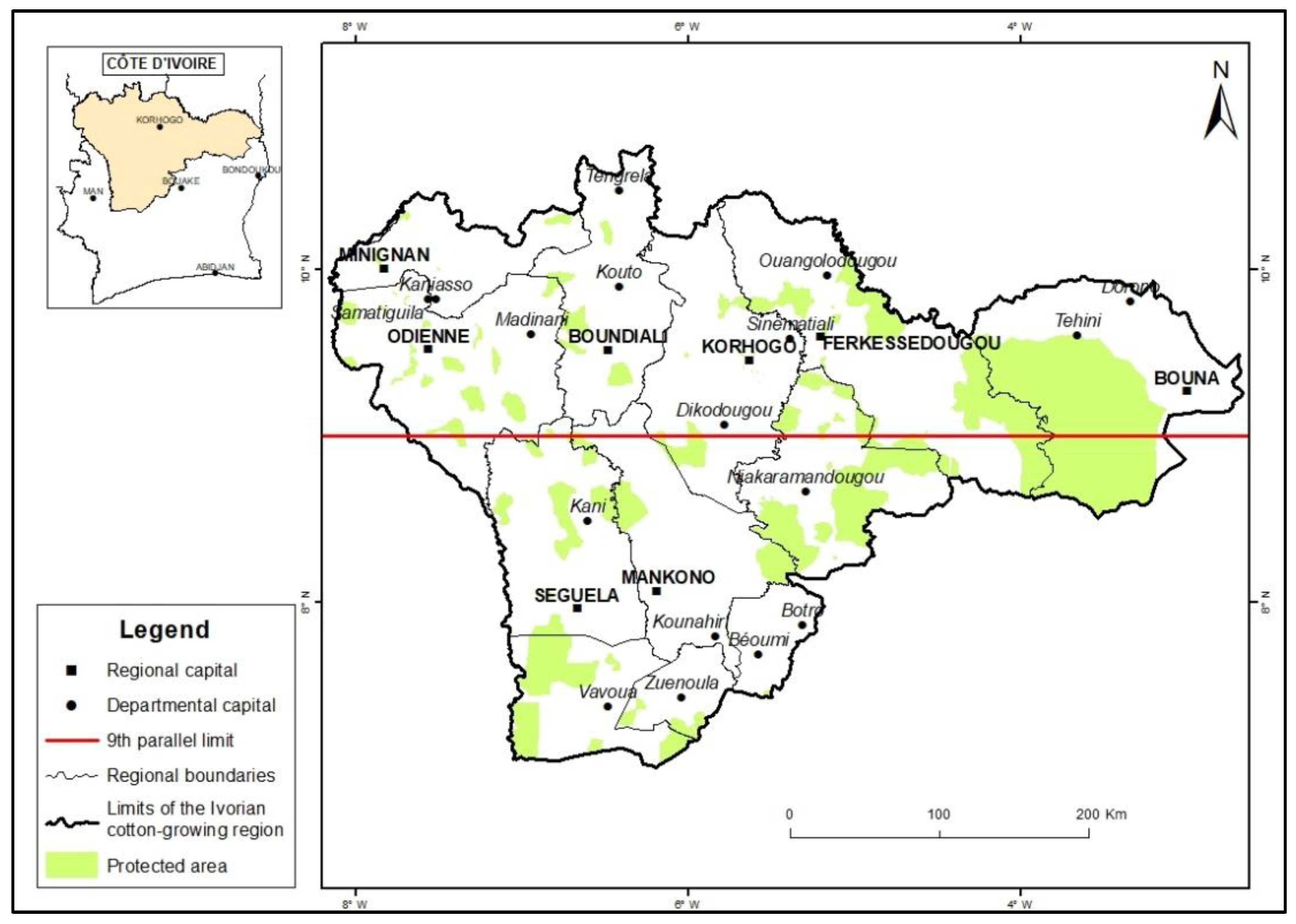

This research was conducted in the cotton-producing region of Côte d’Ivoire, which extends from the central to the northern part of the country between latitudes 7°5 to 12° N and longitudes 3° to 8.5°W (

Figure 1). This region spans both sides of the 9th parallel. The area north of the 9th parallel is characterized by a Sudanian climate featuring an extended dry season from October of one year to May of the subsequent year. Conversely, the southern area situated below the 9th parallel experiences greater precipitation and is characterized by a sub-Sudanian climate with two distinct rainy and dry seasons. The rainy season occurs from March to July and from October to November, whereas the dry season occurs from August to September and from December to February. The annual rainfall in this region varies between 1300 and 1700 mm [

10]. Fifty localities were selected from the entire cotton-growing region.

2.2. Plots Selection

In each location, 10 producer plots were chosen to ensure a representative sample of local variability while remaining feasible for intensive data collection purposes. Two parameters guided the selection process: First, the North-South and East-West axes were considered to ensure comprehensive representation across the locality. The second parameter was the cotton-sowing period. Initially, the sowing dates of all producers in the area were recorded and grouped into 10-day intervals, known as decades. Subsequently, 10 producers were selected from these sowing decades. The number of producers selected per decade was proportional to the overall number of producers who sowed during that period. In the northern region, most producers sowed between June 1st and June 30th, resulting in seven out of ten producers (70%) being selected during this timeframe. In the southern region, most sowing occurred between June 11th and July 10th, encompassing eight of the ten producers (80%) in the sample. After determining these allocations, a random draw was performed.

In each selected plot, a usable area of 0.25 ha was marked at the center for the purpose of data collection. This specific area size is commonly used in field trials to ensure a representative sample, and placing it in the center helps mitigate potential edge effects from surrounding non-study areas or different management practices. This allows for monitoring the evolution of the factors studied in the same portion and makes data collection easier

The local cotton variety used in this study was Gouassou Fus. In addition to being tolerant to Fusarium wilt, this variety has good agronomic and technological characteristics [

11].

2.3. Sampling and Observations

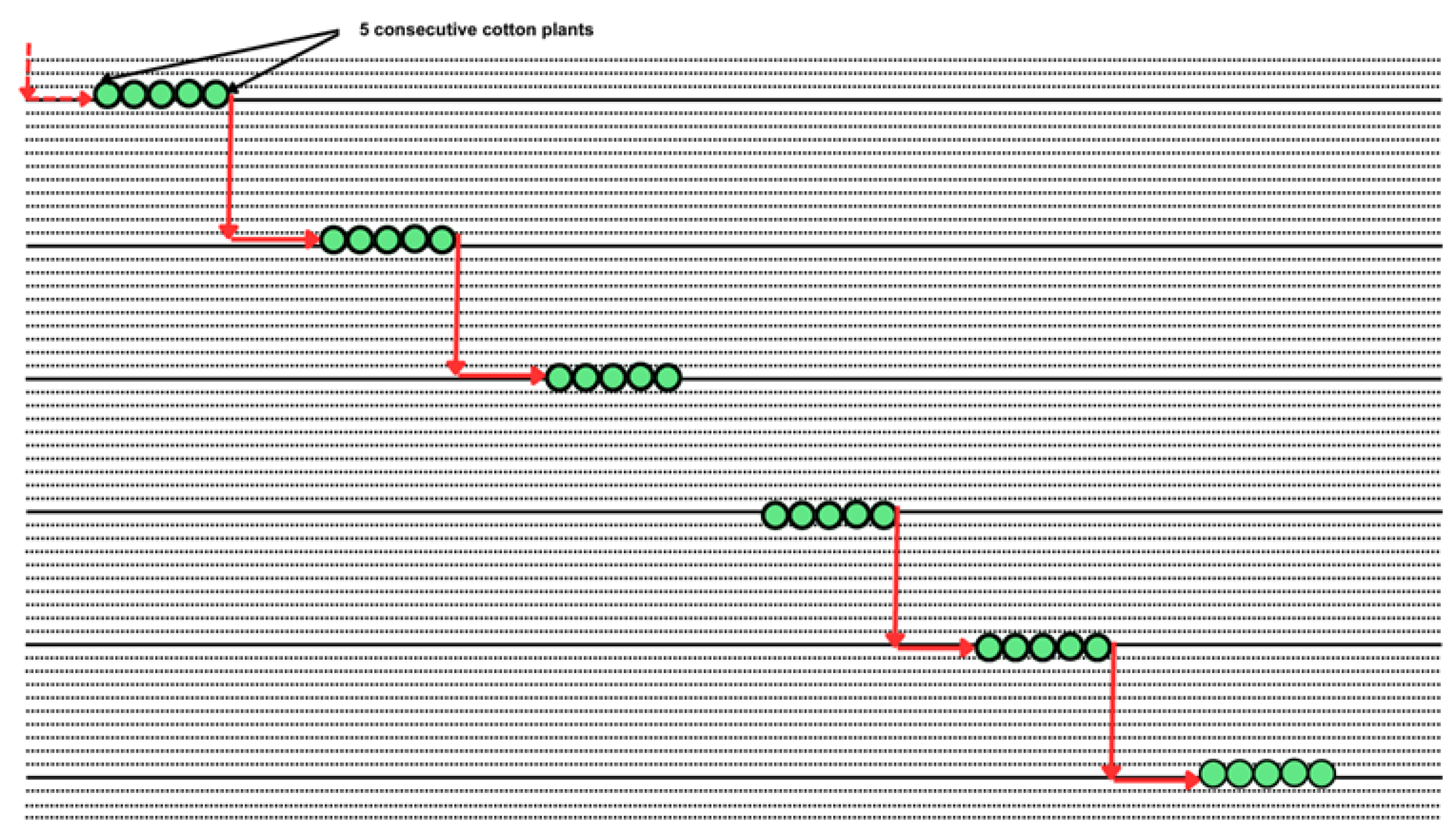

Weekly direct observations were conducted on the plants from the 30th to the 122nd day after planting. Each observation involved 30 cotton plants on 30 cotton plants within an observation area of 0.25 ha. These plants were selected in six groups of five consecutive plants along a diagonal transect of the field [

12], as shown in

Figure 2 to ensure representativeness. In addition, the diagonals were changed weekly to better cover the fields.

Each plant was meticulously examined to count Diparopsis watersi, Helicoverpa armigera, and Earias spp. larvae. These species are classified as exocarpic because the larvae inhabit and develop external bolls on the cotton plant.

P. gossypiella and T. leucotreta larvae develop within bolls and are thus categorized as endocarpic. Consequently, a sanitary analysis of bolls is imperative for their detection. Starting on the 80th day after sowing, five health evaluations were conducted on days 80, 87, 94, 101, and 108. During each evaluation, 50 green capsules were randomly sampled from within the 0.25 ha plot, with only one boll taken from each plant. However, the cotton plants in the four central rows were spared as they were reserved for yield estimation. These bolls, which were approximately the same age, were sampled from the middle of the plant and close to the main stem. After collecting, the bolls were examined and categorized into several classifications: healthy, perforated bolls, and bolls that appeared healthy but had internal damage.

During the sanitary analysis, larvae of Pectinophora gossypiella and Thaumatotibia leucotreta present into bolls were counted.

Harvesting was conducted in the four central rows of each plot when the bolls were fully opened. Seed cotton weighed after harvesting, and the yield was quantified in kilograms per hectare.

2.3. Statistical Analyses of the Data

Various analyses were performed on the data. Analysis of variance was performed to compare the pest averages across years. locations. and sowing periods. Correlation and regression analyses were performed to evaluate the relationship between bollworms, health status of bolls, and seed cotton yield. These analyses were performed using GenStat Tenth Edition software.

Spatial distribution maps were created using the ggplot2 package to assess the geographic distribution of carpophagous Lepidoptera in cotton-growing regions.

3. Results

3.1. Average Abundances of Cotton Bollworms

The mean densities of the various bollworms are listed in

Table 1. For exocarpic larvae, the average numbers per 30 plants were approximately 0.038±0.011 for

D. watersi, 0.14±0.061 for

H. armigera, and 0.06±0.012 for

Earias spp. In terms of endocarpic larvae, the mean densities in 100 green capsules were 0.014±0.003 for

P. gossypiella and 0.001±0.00 for

T. leucotreta. respectively.

Having established baseline densities, it is important to explore their fluctuations over the study period.

3.2. Annual Variations in the Abundance of Cotton Bollworms

3.2.1. Variation of Exocarpic Bollworms

Table 2 shows the results of the statistical analyses performed to evaluate the larval population densities from 2021 to 2024.

The average larval densities ranged from 0.03 ±0.00 to 0.07 ±0.01 larvae per 30 plants for D. watersi, from 0.11±0.04 to 0.22±0.04 larvae per 30 plants for H. armigera, and from 0.05±0.01 to 0.07±0.01 larvae per 30 plants for Earias spp. Statistical analyses revealed significant differences between the annual averages of D. watersi, H. armigera, and Earias spp. In 2024, the larval density of D. watersi was high, exceeding twice the average recorded in 2021. In contrast, H. armigera showed a decline in 2022, with densities of 0.06±0.03 larvae per 30 plants compared to 0.11±0.04 to 0.22±0.04 larvae per 30 plants in 2021. However, the density doubled in 2023, reaching 0.22±0.04 larvae per 30 plants before experiencing a slight decrease in 2024, with densities ranging from 0.13±0.04 to 0.22±0.05 larvae per 30 plants. The larval density of Earias spp. decreased in 2022. However, the population levels returned to the same level during the following two years (2023 and 2024).

3.2.2. Variation of Endocarpic Bollworms

For P. gossypiella, a notable variation in average density was observed across years. The highest density was recorded in 2023, at 0.02 larvae per 100 capsules. Conversely, the lowest densities were recorded in 2021 and 2022 at 0.006 and 0.009 larvae per 100 capsules, respectively. A discernible trend of gradual population increase was evident from 2021 to 2024. In contrast, the average density of T. leucotreta remained very low, approaching zero, in all years. No significant variations were observed. The populations appear to be stable at a very low level throughout the 2021-2024 period

3.3. Impact of the Production Area on the Larval Densities of Cotton Bollworms

3.3.1. Impact of the Production Area on Exocarpic Bollworms

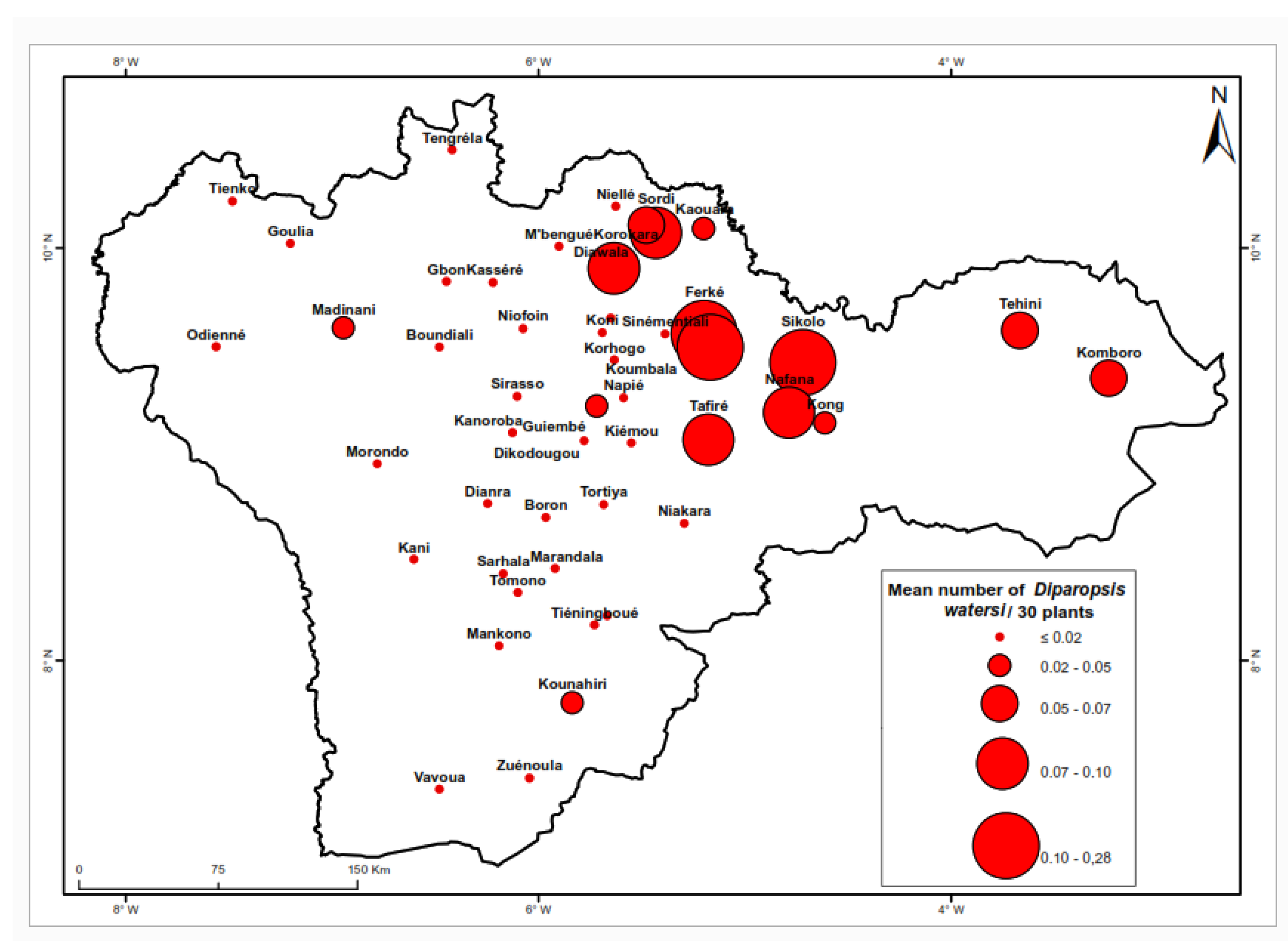

Figure 3 shows notable variations in the distribution of

D. watersi across different locations. The highest larval densities were recorded in the northeast, specifically in Ferké (0.46 larvae per 30 plants), Koumba (0.22 larvae per 30 plants), and Sikolo (0.20 larvae per 30 plants). Conversely, densities approaching 0 larvae per 30 plants were observed in Bouandougou, Boundiali, Boron, Niofoin, Odiéné, Sarhala, Sinématiali, Tienko, Tomono, Vavoua and Zuénoula. The comprehensive analysis presented in

Table 3 indicates that this species predominantly inhabits northern cotton-growing areas.

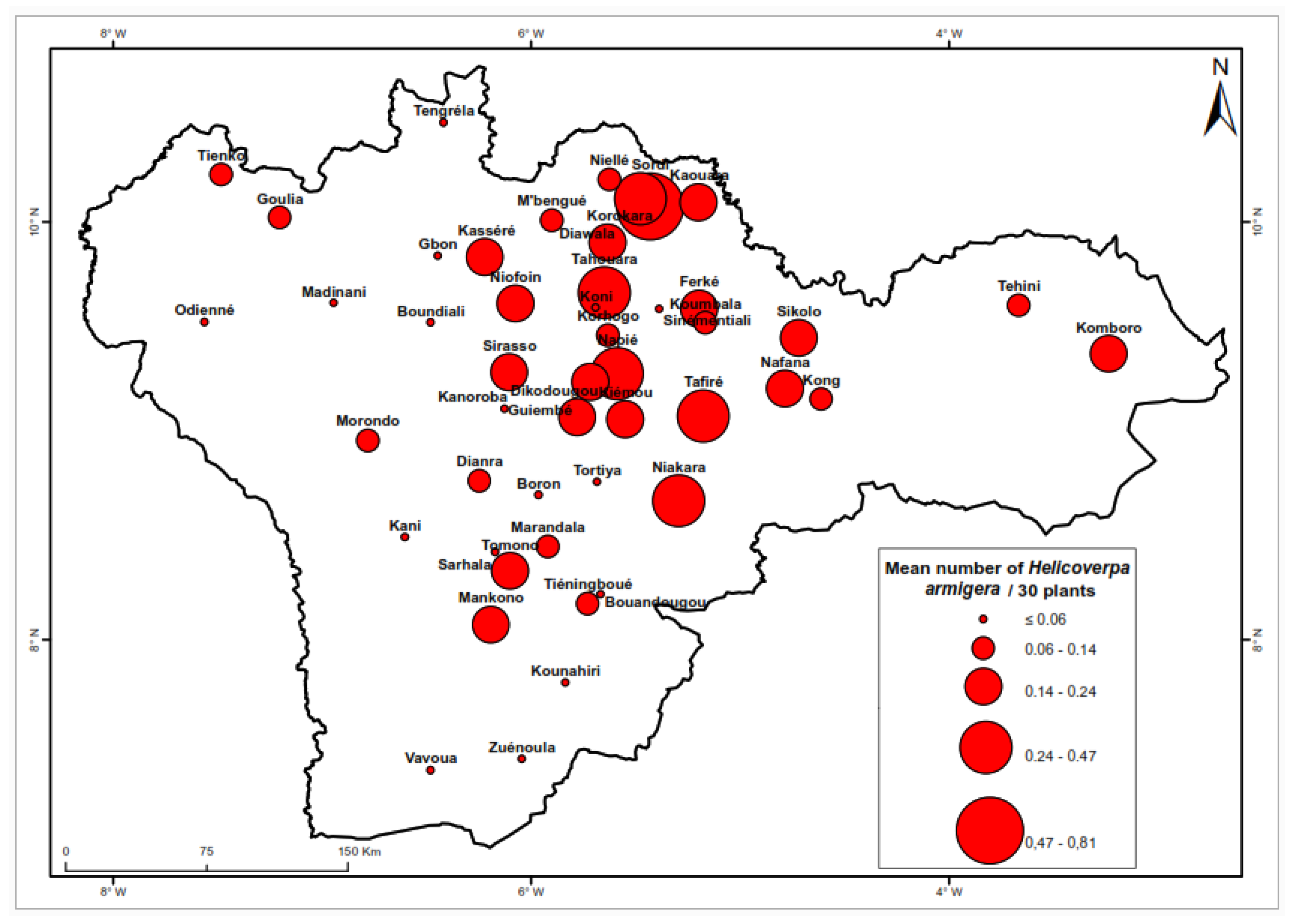

Figure 4 illustrates the distribution of

H. armigera across the various production zones. This species was prevalent in all zones. The highest density was recorded in Sordi (0.81 larvae per 30 plants). followed by Napié (0.47 larvae per 30 plants) and Diawala (0.41 larvae per 30 plants). In contrast, lower densities were observed in localities such as Boundiali and Ouéllé. Goulia and Gbon, with averages approaching 0.00 larvae per 30 plants. The comparative analysis in

Table 3 reveals a significant difference between the northern and southern regions of the cotton basin; larval density was greater in the north (0.16 larvae per 30 plants) than in the south (0.10 larvae per 30 plants).

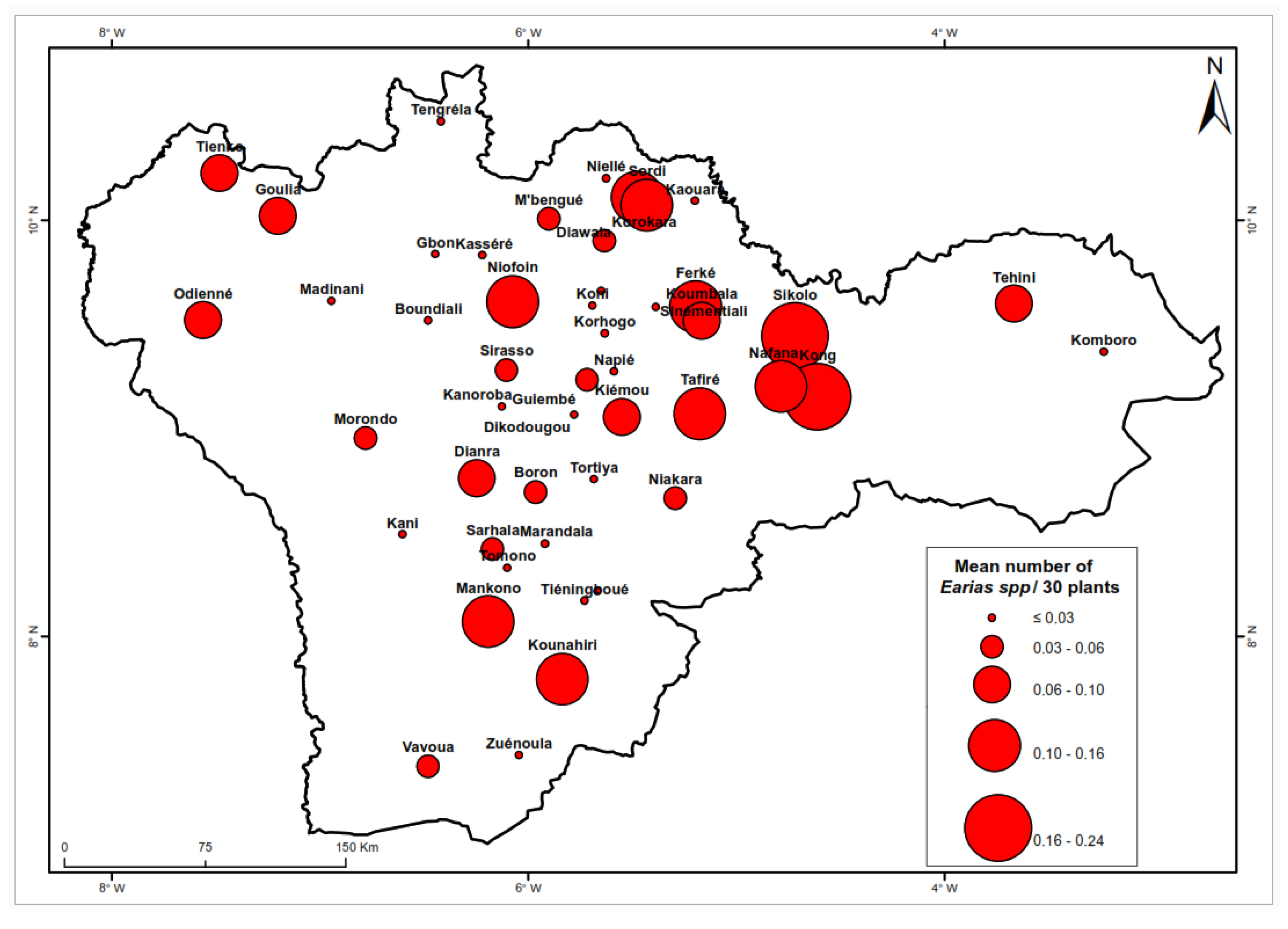

Significant variations in the presence of

Earias spp. were observed across different locations (

Figure 5) with a notably higher prevalence in the northeastern region of the country. The average larval density was highest in Diawala. with 0.45 larvae per 30 plants followed by Ferke and Sikolo each with 0.24 larvae per 30 plants. Conversely, the lowest densities (approximately 0.00 larvae per 30 plants, were recorded in Boundiali, Bouandougou, and Sinématiali. The analysis in

Table 3 revealed that the average density of

Earias spp. in the northern region exceeded that in the southern region.

3.3.2. Impact of the Production Area on Endocarpic Bollworms

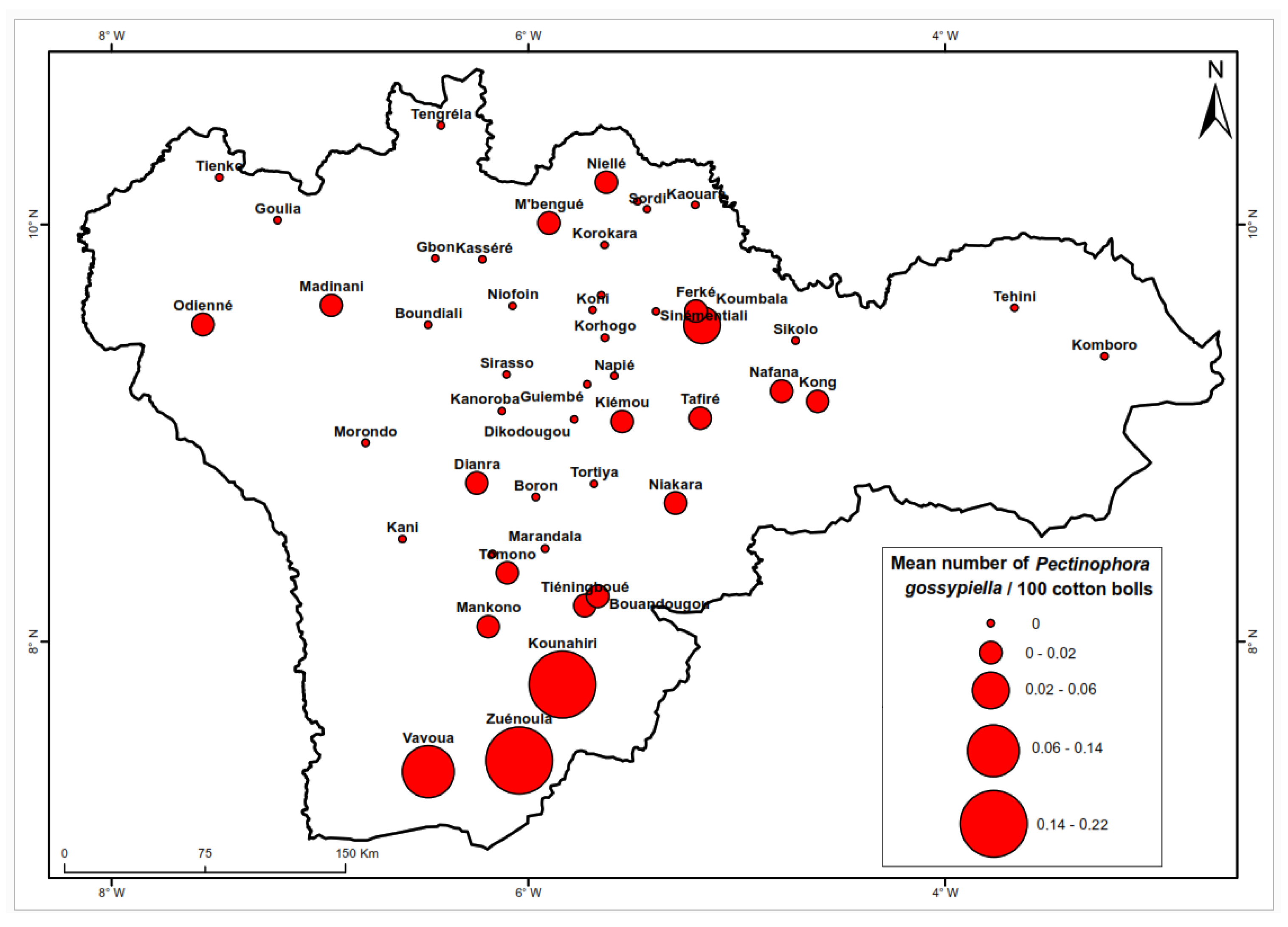

Figure 6 illustrates the notable variation in larval densities of

P. gossypiella across different localities. This species is predominantly observed in southern regions, specifically in the localities of Zuénoula (0.22 larvae/100 bolls), Kounahiri (0.21 larvae/100 bolls). Vavoua (0.14 larvae/100 bolls) and Koumbala (0.06 larvae/100 bolls). The analytical results presented in

Table 3 suggest a higher abundance of these species in the southern cotton-growing basin.

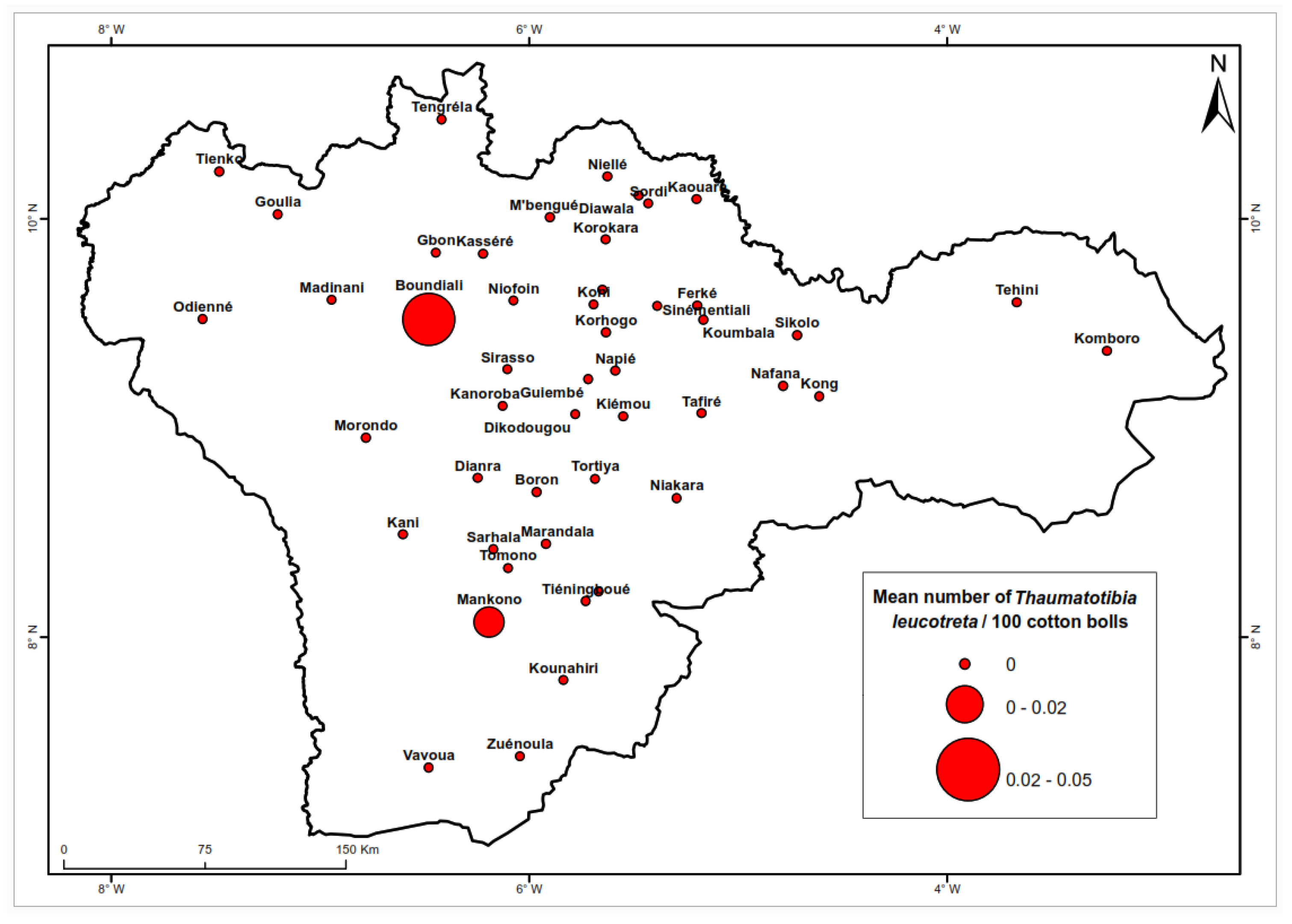

Figure 7 depicts the overall low density of

T. leucotreta. The highest densities were recorded in Boundiali (0.05 larvae/100 bolls) and Mankono (0.02 larvae/100 Bolls). This species did not exhibit a distinct distribution pattern between the northern and southern regions (

Table 3).

3.4. Influence of the Sowing Period on the Density of Cotton Bollworms

Table 4 presents the densities of various species of carpophagous Lepidoptera according to cotton-sowing timing.

No statistically significant differences were detected in the average densities of Diparopsis watersi, Earias spp., P. gossypiella, and T. leucotreta across the various sowing periods. In contrast, a significant variation in the density of H. armigera was observed depending on the sowing period. The highest density (0.18 larvae per 30 plants) was recorded during the D4 sowing period (June 21 to 30), whereas the lowest density was noted during the D1 sowing period (May 20 to 31). Overall, there was an observable trend indicating a progressive increase in H. armigera density from the early to the late sowing periods.

3.5. Influence of Bollworms on the Sanitary Condition of Green Bolls and Cotton Yield

Table 5 presents the results of multiple regressions of the mean number of perforated bolls as a function of the larval density. The analysis of variance was significant (p <0.001) and indicated that Lepidopteran larvae were responsible for approximately 10.5% of the prforation of bolls (R

2 = 0.105). The species with a significant influence were

D. watersi,

H. armigera,

Earias spp. and

P. gossypiella. All regression coefficients (β) were positive. This indicates that the rate of perforated bolls increases when larval populations are high. Furthermore, the analysis of the standardized coefficients showed that

D. watersi had the greatest influence on the rate of perforated bolls, followed by

P. gossypiella and

H. armigera.

The results of the regression analysis of bolls with internal damage are presented in

Table 6. The regression was significant and indicated that 3% of the variations in this parameter were due to the larvae of carpophagous Lepidoptera (R

2 = 0.3; p <0.001). An examination of the coefficients (β) showed that the rate of bolls with internal damage increased when the larval populations of

P. gossypiella and

T. leucotreta were high. Conversely, this rate decreased when the larval populations of

D. watersi,

H. armigera, and

Earias spp. were high. The analysis of the standardized coefficients (β std) showed that

D. watersi,

P. gossypiella, and

T. leucotreta were the most influential.

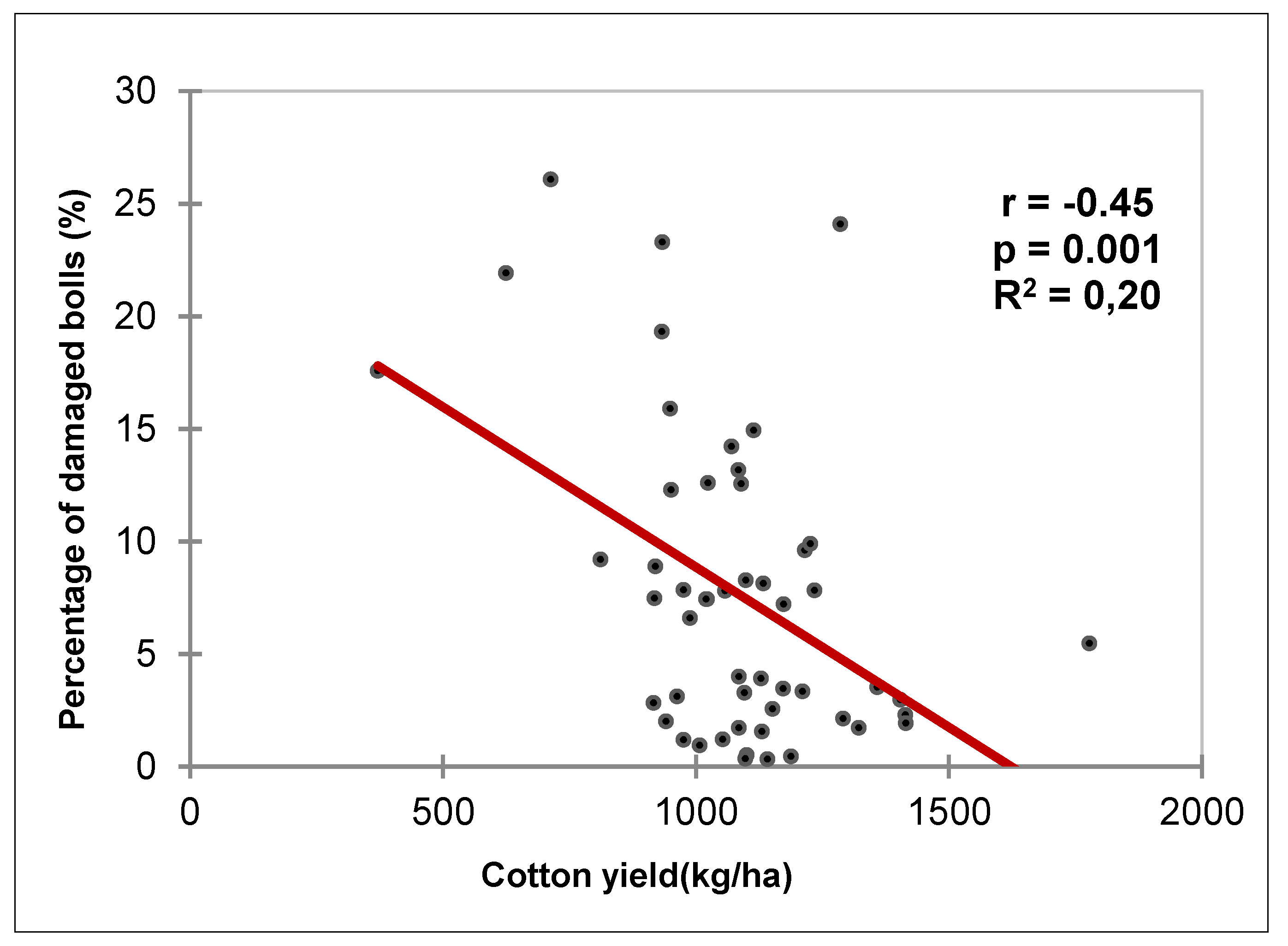

Figure 8 illustrates a significant negative correlation (r = -0.45) between seed cotton yield and the percentage of damaged green bolls. Approximately 20% of yield losses are related to damage caused by bollworms (R

2 = 0.20).

4. Discussion

The study showed that

Helicoverpa armigera is the most predominant exocarpic bollworm, followed by

Earias spp and

Diparopsis watersi. The prevalence of

H. armigera may be due to the diversity of host plants in the production environment. Indeed, this species is found worldwide and is known to feed on more than 300 plant species belonging to over 68 families [

13]. Although it is recognized as the key pest of cotton, studies have shown that several other crops are more attractive to

H. armigera, particularly tobacco, maize, and sunflower [

14]. This predisposition allows

H. armigera to adapt easily and proliferate in various regions [

15,

16]. Therefore, management of this species should take several aspects into account, including relay host plants. In contrast, the

Diparopsis watersi species does not have a wide diversity of host plants. This species enters diapause during the dry season to survive unfavorable environmental conditions, such as temperature, relative humidity, photoperiod, etc. [

17,

18,

19].

Among the two endocarpic species,

Pectinophora gossypiella was the most abundant. Indeed, previous studies have shown difficulties in controlling these two species. Previous work on

P. gossypiella demonstrated that larval development inside the capsules greatly limits the effectiveness of insecticide products [

20]. Furthermore, studies on sensitivity have revealed a strong presence of insecticide detoxification enzymes in

P. gossypiella and levels of resistance, particularly to organophosphates [

21]. It would thus be advisable to consider integrated management strategies. Alternative methods such as mating disruption [

22], mass trapping [

23], and integrated management strategies have been evaluated [

24,

25,

26].

Regarding the spatial distribution of the studied pests, exocarpic species (

H. armigera,

D. waersi, and

Earias spp.) were more abundant in areas located above the 9th parallel, whereas the densities of endocarpic species (

P. gossypiella and

T. leucotreta) were higher in the area situated below the 9th parallel. These results confirm previous studies [

27]. This distribution may be influenced by agro-climatic conditions. Indeed, the northern zone is characterized by a Sudanian climate, with a dry season and a rainy season. The southern part is marked by a sub-Sudanian climate, with two dry seasons and two rainy seasons throughout the year [

3]. In fact, climatic factors such as temperature, rainfall, and relative humidity in the different zones could determine the spatiotemporal distribution of the various pests [

28,

29].

From the perspective of year-to-year evolution, studies have shown fluctuations in infestation levels for all species. This could be explained not only by variations in agroclimatic factors but also by interactions with other biotic agents. Indeed, the 2022-2023 period saw the invasion of the jassid species

Amrasca biguttula, which disrupted the composition of the insect fauna on cotton [

30]. From 2023 to 2024, protection programs focused on controlling this new species, using specific products such as flonicamid. However, these products proved ineffective against fruit-feeding Lepidoptera. This situation led to a resurgence of their infestations [

8,

31].

The studies also highlighted the impact of bollworms on the health of the bolls and on yield. These pests are responsible for about 3 to 10% of the damage observed on the bolls, leading to nearly a 20% loss in yield, despite plant protection measures. These results confirm the status of carpophagous Lepidoptera as major pests of cotton cultivation in West Africa [

4,

5]. Despite the invasion of jassids in 2022, carpophagous Lepidoptera thus remain major pests. Their significance stems from their direct feeding on the reproductive organs (flower buds, flowers, and bolls) of the cotton plant. The resurgence of carpophagous Lepidoptera after the jassid invasion reflects the complexity of cotton plant protection and the need to consider other approaches.

The results generally show instability in the populations of bollworms in cotton-producing areas. This highlights the need for regular monitoring in relation to agroclimatic factors, to study the sensitivity of different species to the insecticides used by producers, and to assess the effectiveness of the pest control programs implemented.

5. Conclusions

This study conducted on cotton bollworms in Côte d'Ivoire from 2021 to 2024 revealed several significant results. It demonstrated that fruit-feeding Lepidoptera remain major pests of cotton, significantly affecting production. Then, focusing protection strategies on the invasive species Amrasca biguttula is likely to cause their resurgence.

These results underscore the necessity of sustaining continuous surveillance of bollworms and adjusting control strategies according to the prevailing species, geographic regions, and planting schedules. Integrated pest management, which encompasses suitable cultural practices and targeted phytosanitary interventions, is essential for mitigating yield losses attributable to these pests.

Author Contributions

Data curation, Mamadou Ouattara; Investigation, Norbert Bini; Methodology, Malanno Kouakou; Software, Mamadou Ouattara; Supervision, Malanno Kouakou; Writing – original draft, Malanno Kouakou; Writing – review & editing, Norbert Bini.

Funding

This study did not receive financial support.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author of this paper. due to the sensitive nature of cotton cultivation in Côte d'Ivoire.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest regarding the results presented in this study.

References

- INTERCOTON. « Flash d’information statistiques ». APROCOT-CI, 29 février 2024. Consulté le: 25 octobre 2025. [En ligne]. Disponible sur : https://www.intercoton.ci/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Flash_Stats_n%C2%B003-au-29-fevrier-2024.pdf.

- Kouadio, E.N.; Koffi, E.K.; Julien, K.B.; Messoum, G.F.; Brou, K. et N’guessan, D.B. « Diagnostic de l’Etat de Fertilité des Sols Sous Culture Cotonnière Dans les Principaux Bassins de Production de Côte d’Ivoire », Eur. Sci. J. ESJ, vol. 14, no 33, p. 221, nov. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Dekoula, C.S.; Kouame, B.; N’goran, E.K.; Yao, F.G.; Ehounou, J.N. et Soro, N. « Impact De La Variabilité Pluviométrique Sur La Saison Culturale Dans La Zone De Production Cotonnière En Côte d’Ivoire », Eur. Sci. J. ESJ, vol. 14, no 12, p. 143, avr. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Hillocks, R.J. « Main Pests and Diseases of Cotton in Sub-Saharan Africa. By M. Vaissayre and J. Cauquil. Montpellier: CIRAD-CTA (2000), pp.60, FF100.00. ISBN 2-87614-16-6. », Exp. Agric., vol. 37, no 3, p. 429-432, juill. 2001. [CrossRef]

- Silvie, P.J. et Papierok, B. Les arthropodes du cotonnier: Diversité et modalités de gestion des ravageurs. éditions Quæ, 2024. [CrossRef]

- CABI. « Amrasca biguttula ». in CABI Compendium. CABI Publishing, 19 septembre 2022. [CrossRef]

- Kouadio, H.; Kouakou, M.; Bini, K.K.N.; Ouattara, M.A.N.; Adepo-Gourène, B.A. et Ochou, O.G. « Diagnosis of jassid attacks on okra and eggplant plots in the Center and Center-West of Côte d’Ivoire », Int. J. Innov. Appl. Stud., vol. 38, no 2, p. 408-416, déc. 2022.

- Gouzou, D.R.J.; Norbert, B.K.K.; Malanno, K.; Woklin, K.P.E. et Houphouët, K. « Effectiveness of a formulation based on Indoxacarb 120 g/l + flonicamid 200 g/l (SC) in controlling sucking biting insects and carpophagous Lepidoptera larvae of cotton in Côte d'Ivoire », J. Entomol. Zool. Stud., vol. 12, no 5, p. 235-241, sept. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Morita, M.; Ueda, T.; Yoneda, T.; Koyanagi, T. et Haga, T. « Flonicamid, a novel insecticide with a rapid inhibitory effect on aphid feeding », Pest Manag. Sci., vol. 63, no 10, p. 969-973, 2007. [CrossRef]

- Halle B. et Bruzon, V. « Profil Environnemental de la Côte d’Ivoire ». https://fr.scribd.com/document/148957688/Profil-Environnemental-Ci. Consulté le: 25 octobre 2025. [En ligne]. Disponible sur: https://fr.scribd.com/document/148957688/Profil-Environnemental-Ci.

- Amangoua N.F.; Essoi, N.; Kouakou, M.; Kouakou, B.J.; Kouadio, N.E.; Bini, K.K.N.; Ochou, O.G. « Etude des caractéristiques agro-morphologiques et technologiques de cinq variétés de cotonniers sélectionnées en Côte d’Ivoire », Int. Jouranl Biol. Chem. Sci., vol. 16, no 5, p. 2102-2124, oct. 2022.

- Nibouche, S.; Beyo, J. et Goze, E. « Mise au point de plans d’échantillonnage pour la protection sur seuil contre les chenilles de la capsule du cotonnier ». Consulté le: 26 juillet 2025. [En ligne]. Disponible sur: https://publications.cirad.fr/une_notice.php?dk=509800.

- Wang, H.; Shi, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, S.; Wu, S. « CYP6AE gene cluster knockout in Helicoverpa armigera reveals role in detoxification of phytochemicals and insecticides », Nat. Commun., vol. 9, no 1, p. 4820, nov. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Firempong S. Zalucki, M. « Host Plant Preferences of Populations of Helicoverpa-Armigera (Hubner) (Lepidoptera, Noctuidae) From Different Geographic Locations », Aust. J. Zool., vol. 37, no 6, p. 665-673, nov. 1989. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, F.; Tae, W.T.; Robin, C.; Chi, Y. « Population genomics provides insights into lineage divergence and local adaptation within the cotton bollworm », Mol. Ecol. Resour., vol. 22, no 5, p. 1875-1891, juill. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, R.M.; Mastrangelo, T.; Rodriges, J.C.; Paulo, D.F.; Omoto, C.; Corêa, A.S.; De Azeredo-Espin, A. « Invasion origin, rapid population expansion, and the lack of genetic structure of cotton bollworm ( Helicoverpa armigera ) in the Americas », Ecol. Evol., vol. 9, no 13, p. 7378-7401, juill. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Caporale, A.; Romanowski, H.P. et Mega, N.O. « Winter is coming: Diapause in the subtropical swallowtail butterfly Euryades corethrus (Lepidoptera, Papilionidae) is triggered by the shortening of day length and reinforced by low temperatures », J. Exp. Zool. Part Ecol. Integr. Physiol., vol. 327, no 4, p. 182-188, avr. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Pener, M.P. « Environmental Cues, Endocrine Factors, and Reproductive Diapause in Male Insects », Chronobiol. Int., vol. 9, no 2, p. 102-113, janv. 1992. [CrossRef]

- Karp, X. « Hormonal Regulation of Diapause and Development in Nematodes, Insects, and Fishes », Front. Ecol. Evol., vol. 9, p. 735924, sept. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Busnoor, A.V.; Wadaskar, R.M.; Pillai, T.; Mahule, D.J.; Prasad, Y.G. « Laboratory evaluation of toxicity of selected insecticides against egg and larval stages of cotton pink bollworm, Pectinophora gossypiella (Saunders) (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) », J. Cotton Res., vol. 7, no 1, p. 2, janv. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.; Hafez, S.; Aly, A.; El-hadek, M. et Allam, R. « Comparative efficacy and Resistance Levels to Certain Organophosphates Insecticide in the Pink Bollworm (Pectinophora gossypiella) », J. Sohag Agriscience JSAS, vol. 8, no 2, p. 363-369, déc. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ghauri, Z.A. Anwar, H. et Ahmad, F. « Mating disruption of pink bollworm, Pectinophora gossypiella (saunders) using pb rope dispensers in cotton growing areas of punjab, pakistan », Plant Prot., vol. 3, no 3, p. 117-123, déc. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Arshad, M. Irfan Ullah, M. Wasim Abbas, A. Abdullah, et U. Hassan, « Mass trapping of Pectinophora gossypiella (Saunders) (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) using light and sex-pheromone traps in cotton », Enfoque UTE, vol. 11, no 4, p. 27-36, oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Lakshmi, V.N.; Ratnakar, V. et Veeranna, G. « Management of Pink Bollworm Pectinophora gossypiella (Saunders) in Cotton », Indian J. Entomol., p. 1-3, mars 2022. [CrossRef]

- Rakhesh, S.; Kumar, A.; Santhosha, K.M.; Krishi, V.K. Hanumanamatti, Haveri, Karnataka-581115, India « A brief review on integrated pest management of pink bollworm, Pectinophora gossypiella (Saunders) in cotton », Insect Environ., vol. 26, no 3, sept. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Narendar, G.; Madhushekar, B.R. et Kumar, K.A. « Strategies for Management of Pink Boll Worm Pectinophora gossypiella (Saunders) in Cotton through Different Methods », Int. J. Environ. Clim. Change, vol. 13, no 11, p. 2522-2527, nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Kouakou, M.; Bini, K.K.N.; Ouattara, B.M. et Ochou, O.G. « New subdivision of cotton production area of Côte d’Ivoire based on the infestation of main arthropod pests », J. Entomol. Zool. Stud., vol. 9, no 3, p. 50-57, mai 2021. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Liu, B.; Yu, H.; Zhang, Z.; He, Z. et Z. Zhuo, « The Effects of Global Climate Warming on the Developmental Parameters of Helicoverpa armigera (Hübner, 1808) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) », Insects, vol. 15, no 11, p. 888, nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Patterson, D.T.; Westbrook, J.K.; Joyce†, R.J.V.; Lingren, P.D.et Rogasik, J. « Weeds, Insects, and Diseases », Clim. Change, vol. 43, no 4, p. 711-727, déc. 1999. [CrossRef]

- Kouadio, H.; Kouakou, M. et Bini, K.K.N. « Annual and geographical variations in the specific composition of jassids and their damage on cotton in Ivory Coast », Scientifi Reports, p. 1-12, 2094 2024.

- Malanno, K.; Norbert, B.K.K. et Houphouët, K. « Efficient dose of thiamethoxam as a seed treatment product to reduce early damage of cotton leafhoppers Amrasca biguttula (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae) in Côte d'Ivoire », J. Entomol. Zool. Stud., vol. 13, no 1, p. 32-35, janv. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Brévault, T.; Badiane, D.; Goebel, R.; Renou, R.; Téréta, T. et Clouvel, P. « Repenser la gestion des ravageurs du cotonnier en Afrique de l’Ouest », Cah. Agric., vol. 28, p. 25, 2019. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).