1. Introduction

Nanocoating with nanoparticles on polymeric materials has emerged as an advanced technique that involves applying a nanoscale layer to polymer surfaces to modify and improve their functional properties [

1]. These nanolayers can be composed of coatings of other polymeric materials or of nanoparticles incorporated into the surface of the polymer matrix, generating a nanostructured composite with enhanced characteristics. This nanocoating confers unique properties to the materials, such as improved abrasion resistance, corrosion protection, antimicrobial properties, increased hydrophilicity or self-cleaning, and chemical resistance [

2,

3,

4,

5]. The nanoparticles used can be metal oxides (ZnO or TiO

2) or copper and silver [

4,

6,

7], which are highly effective antimicrobial agents against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria [

4,

8,

9]. These nanoparticles not only provide antimicrobial activity but also enhance mechanical strength, thermal stability, and protection against ultraviolet radiation, reducing degradation and extending the material’s useful life [

10,

11].

This approach is applied in various sectors, including automotive manufacturing, innovative packaging, functional textiles, and flexible electronic devices. Nanocoatings require molecular engineering to ensure homogeneous nanoparticle distribution and strong adhesion between the nanostructured layer and the polymer matrix [

12,

13,

14,

15].

Nanocoating with nanoparticles on PET polymers represents an innovative technique for improving the functional properties of this widely used material. Despite its widespread use, PET is limited in demanding environments by inherent vulnerabilities, including sensitivity to ultraviolet radiation, thermal degradation, and susceptibility to microbial proliferation in specific applications. Therefore, nanocoatings on the PET surface or the incorporation of nanoparticles into its matrix create a nanostructured composite that provides superior properties. In the case of PET, a common thermoplastic polymer in packaging and textile fibers, the inclusion of nanoparticles can provide significant improvements in thermal stability and protection against ultraviolet radiation, as well as conferring antimicrobial properties [

4,

16].

One challenge is achieving a homogeneous distribution of nanoparticles with strong adhesion to the polymer surface, thereby maximizing functional benefits without compromising the material’s properties. Molecular engineering technologies and methods, such as plasma functionalization, chemical deposition, or successive immersion, can provide fine control over the nanometric layer [

17,

18,

19,

20]. Thus, nanocoating on PET opens a wide field of advanced applications, where the combination of light weight, durability, and functionality is key to developing new high-performance materials [

21]. In summary, nanoparticle nanocoating represents a technological revolution in improving polymeric materials, combining nanotechnology with polymer science to create products with advanced functional properties that expand their use in high-performance applications.

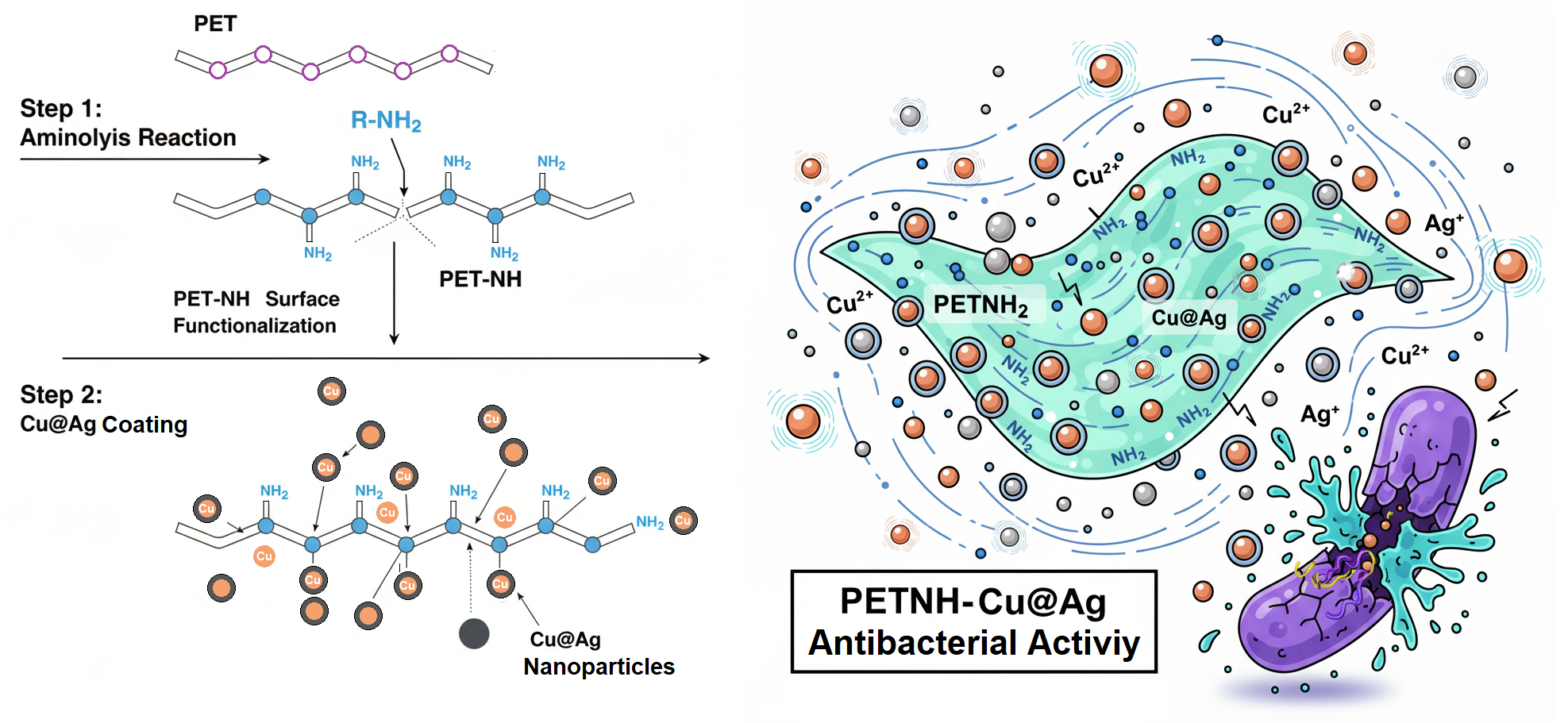

This work addresses the coating of PET films with Cu@Ag nanoparticles through surface functionalization with amino groups using an aminolysis reaction, followed by the reduction of copper and silver ions to form Cu@Ag nanoparticles. The materials were characterized using spectroscopic techniques, thermal analysis, mechanical tests, and evaluation of their antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative microorganisms.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

All reagents used were analytical grade and were used without further purification. Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) films, 100 µm thick, were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Deionized water, ethylenediamine (≥ 99%), copper sulfate pentahydrate (99%), silver nitrate (≥ 99%), and sodium borohydride (95%) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Sodium hydroxide, hydrochloric acid, methanol (99.7%), and sodium orange II salt (≥ 85%) were obtained from Meyer Reagents.

2.2. Functionalization of PET Films with Amino Groups (PETNH)

The PET films (1.2 x 5 cm) were initially washed with water, followed by MeOH, and finally dried at 50 °C for 15 minutes. The PET films were then immersed in 10 mL of ethylenediamine with constant stirring. The reaction was carried out at different reaction times and temperatures.

Table 1 lists the conditions used, and each experiment was performed in triplicate to ensure adequate reproducibility. The films were then thoroughly washed with deionized water and dried at 50 °C until a constant weight was achieved. The film degradation was then determined by measuring the weight loss of the PET film after the aminolysis reaction (Eq. 1).

where PPET is the weight of the unfunctionalized PET film and PPETNH is the weight of the PET film functionalized with amino groups.

2.3. Detection and Quantification of Amino Groups

Amino group quantification was performed using a colorimetric method with orange II. PETNH films were immersed for 30 minutes at 40 °C in 1 mL of an aqueous orange II solution (14 mg/mL) adjusted to pH 3 with 1 M HCl. After the reaction time, the samples were rinsed three times with an acidic aqueous solution (pH 3) and then dried. Subsequently, the orange II-treated films were immersed in 3 mL of an alkaline solution (a mixture of deionized water and 1 M NaOH adjusted to pH 12) to release the orange II. The resulting solution was adjusted to pH 3 with 1 M HCl. Finally, the absorbance was measured at 484 nm, and orange II was quantified using a calibration curve with a 1:1 stoichiometry for each amino group –NH

2 and orange II [

22]. The calibration curve showed a linear relationship, described by the equation [NII]

sol=0.0293Ab–0.0212, with a correlation coefficient of 0.9976. The procedure was performed in triplicate.

The surface density of amino groups in the film ([NH

2]

PET) was determined by relating the total amount of desorbed dye to the exposed area of the sample:

where [NII]

sol is the concentration of the desorbed orange II dye obtained with a 1:1 ratio with the amino groups present on the surface of the film, V

sol is the volume of the desorption solution (ml), A

film is the area of the analyzed PET film (mm

2).

2.4. Synthesis and Loading of Copper Nanoparticles (PETNH-Cu)

Three PETNH films were placed in 20 mL of 0.02 M copper sulfate solution, and the air was removed by bubbling with argon for 10 min. Subsequently, 20 ml of 0.04 M sodium borohydride solution was added, and the reaction was allowed to continue for 10 min. Finally, the PETNH-Cu films were removed, washed with MeOH, and dried under vacuum at 50 °C. Films with a dark orange color were stored in an argon atmosphere to prevent oxidation of the copper nanoparticles.

2.5. Synthesis of CU@Ag Nanoparticles (PETNH-Cu@Ag)

Three PETNH-Cu films were placed in 20 ml of a silver nitrate solution (0.3 M) for 5 min with constant stirring at room temperature. After this time, the films were removed from the medium and washed vigorously with deionized water. The PETNH-Cu@Ag films were stored under no special conditions until characterization.

2.6. Antimicrobial Tests

The ability of PETNH-Cu and PETNH-Cu@Ag films to inhibit bacterial growth against Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) and Escherichia coli (E. coli) was evaluated. Petri dishes containing Mueller-Hinton agar were inoculated at a concentration of 1.2 × 109 CFU/mL for S. aureus and 3.4 × 109 CFU/mL for E. coli (where CFU is a colony-forming unit). PET and PETNH were used as controls, and PETNH-Cu and PETNH-Cu@Ag (0.6 cm in diameter) were tested to evaluate antimicrobial activity. The sample plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The zone of inhibition was measured using a scale. Antimicrobial activity was assessed in triplicate using a fresh sample.

2.7. Instrumental

Fourier Transform Infrared-Attenuated Total Reflection (FTIR-ATR) of dry samples was recorded using a Perkin-Elmer Spectrum 100 spectrometer (Norwalk, CT, USA) of 16 scans.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) images were acquired by the Zeiss Evo LS15 instrument (Jena, Germany), and small pieces of 0.5 cm in length were cut and analyzed under a high vacuum with carbon coating.

A GEEFUNTECH GF08 brightfield trilocular compound microscope with 40x magnification was used to obtain images of the samples placed directly onto a slide.

The TGA5000 Discovery Thermobalance from TA Instruments (New Castle, DE, USA) was used to perform the thermogravimetric study in a temperature range of 30 °C to 800 °C, using a heating rate of 20 °C/min and a nitrogen flow at 100 cm3/min.

The X-Ray Photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) spectra of the samples were recorded using a Microprobe PHI 5000 Versa Probe II (Chanhassen, Minnesota, USA), with an excitation source of Al Kα monochromatic, energy 1486.6 eV, 100 µm beam diameter, and with a Multi-Channel Detector (MCD). The energy scale was corrected using the C1s peak to 285.0 eV. Multipack software was used spectra data.

Mechanical properties of the films were studied by applying an uniaxial tension test, as described in ASTM D1708. All tests were carried out on an INSTRON 1125 (Instron Inc., MA, USA) universal tensile testing machine at a crosshead speed of 10 mm/min, and all experiments were carried out in triplicate.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Surface Functionalization of PET with Amino Groups

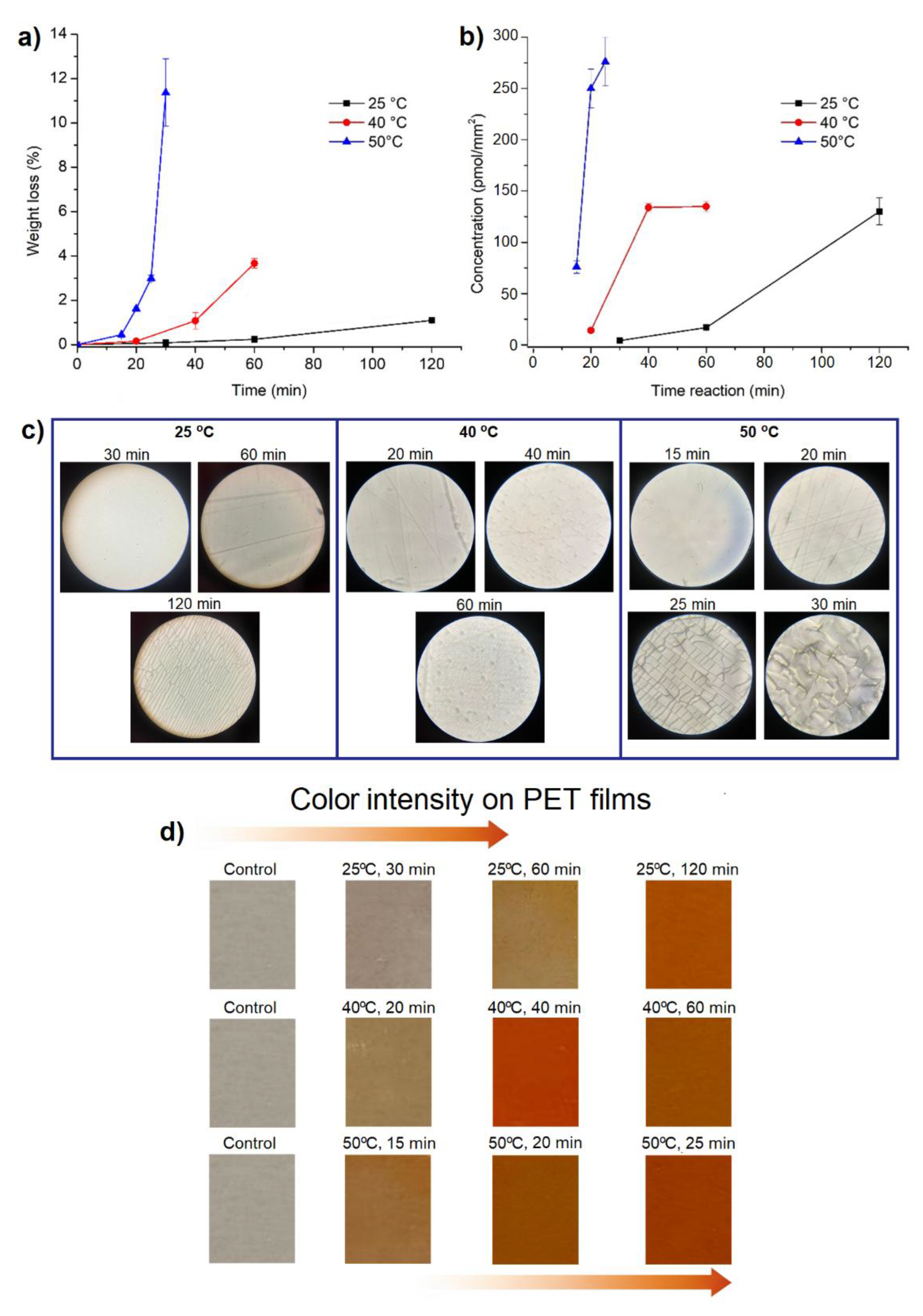

The aminolysis reaction of PET films with ethylenediamine was carried out efficiently, showing a weight loss attributed to the rupture of the ester groups that comprise the polymer chains. This degradation occurs as amino groups are incorporated through aminolysis reaction, and different reaction times and temperatures were studied to optimize functionalization and minimize the loss of the polymer’s structural integrity. At 25 °C, the weight loss increased gradually with time, requiring longer reaction times for effective functionalization. However, at higher temperatures (40 and 50 °C), the weight loss was significantly greater over much shorter times, increasing from 1.0 ± 0.05% at 25 °C after 120 minutes to 11.3 ± 1.51% at 50 °C after 30 minutes. These results indicate that temperature accelerates aminolysis, decreasing the reaction time but increasing matrix degradation. In addition, crack formation was observed on the surface of the PET under high temperature and prolonged reaction times (

Figure 1a,b).

Quantification of amino groups in PET films subjected to aminolysis indicated that increased temperature and reaction time favor the incorporation of amino groups into the polymer surface, despite some material degradation. Films treated at 50 °C showed the highest concentration of amino groups, reaching 276.13± 23.65 pmol/mm

2 in short reaction times, while longer reaction times were required at 25 °C and 40 °C to achieve lower concentrations, with 130.02± 12.93 pmol/mm

2 and 134.89 ± 4.83 pmol/mm

2, respectively (

Figure 1b,d). Based on these results, PET-NH films obtained at 50 °C for 15 minutes were selected for subsequent loading with Cu@Ag nanoparticles, thereby optimizing the surface functionalization process to enhance nanoparticle binding and stabilization.

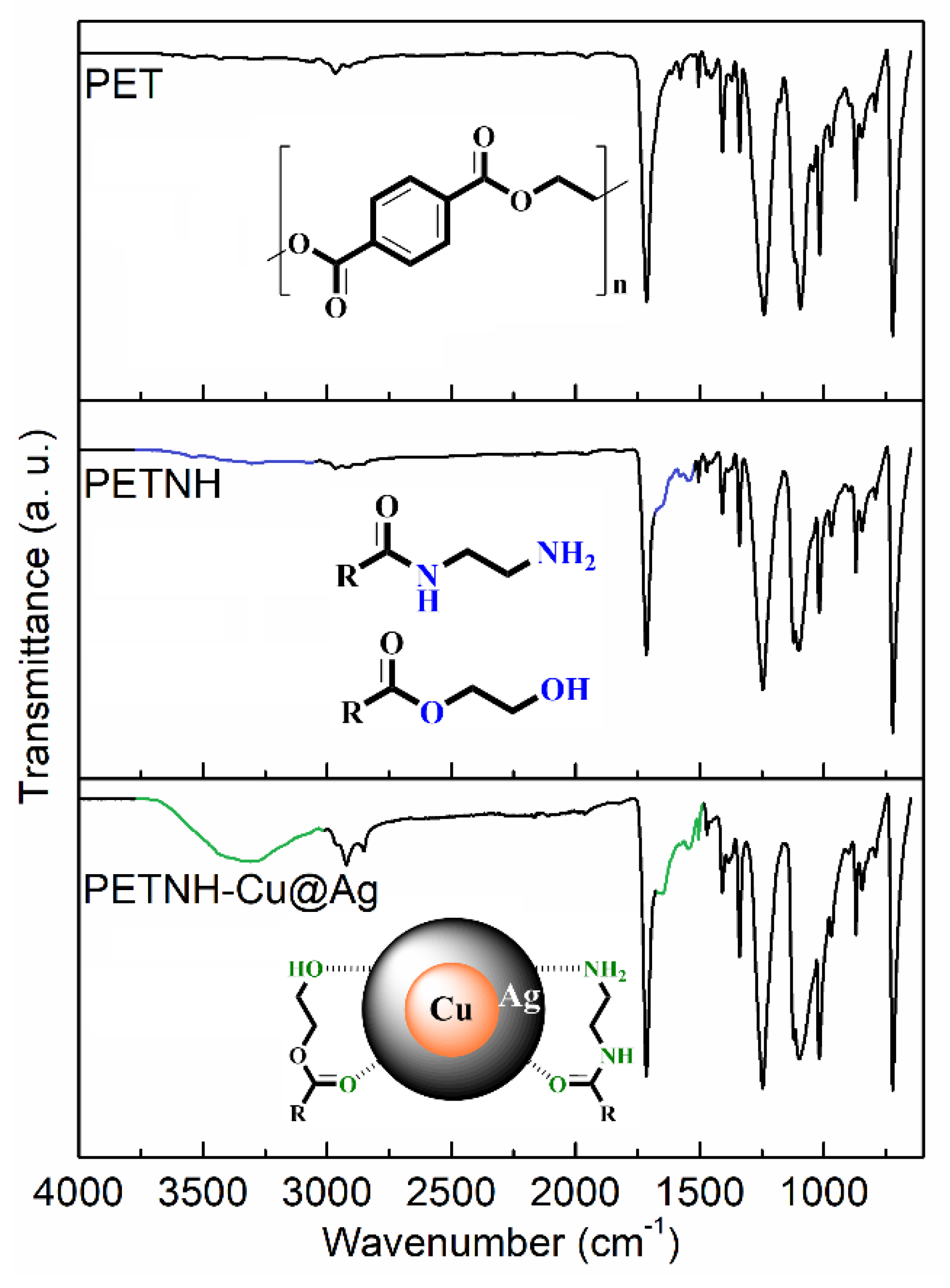

3.2. FTIR-ATR Analysis

Figure 2 presents the FTIR spectra of pristine PET and chemically functionalized samples during nanoparticle incorporation. The unmodified PET film spectrum shows a characteristic band at 1714 cm

−1, corresponding to the carbonyl stretching vibration (sv C=O), and another at 1242 cm

−1, attributed to the ester stretching vibration (sv C-O-C). Signals in the 2098–2967 cm

−1 range correspond to C-H stretching vibrations (sv C-H), while a band at 3030 cm

−1 is assigned to aromatic C=C-H stretching (sv C=C-H). Additionally, overtone bands from aromatic ring stretching (sv C=C) appear between 1950 and 2000 cm

−1.

In the PET-NH sample, a broad band centered around 3350 cm

−1 indicates overlapping O-H and N-H stretching vibrations (sv O-H and sv N-H), accompanied by a new band at 1676 cm

−1 assigned to amide carbonyl stretching (sv C=O, amide), confirming successful PET surface functionalization with amino groups via aminolysis using ethylenediamine [

23]. The spectrum of the Cu@Ag nanoparticle-loaded film (PETNH-Cu@Ag) shows no significant new bands compared to the amino-functionalized film but reveals an increased intensity in the N-H stretching region, possibly due to interactions between the nanoparticles and amine groups. Additionally, narrowing of this band suggests stronger interactions between amino and amido groups after chemical functionalization, evidencing effective nanoparticle stabilization on the modified PET surface.

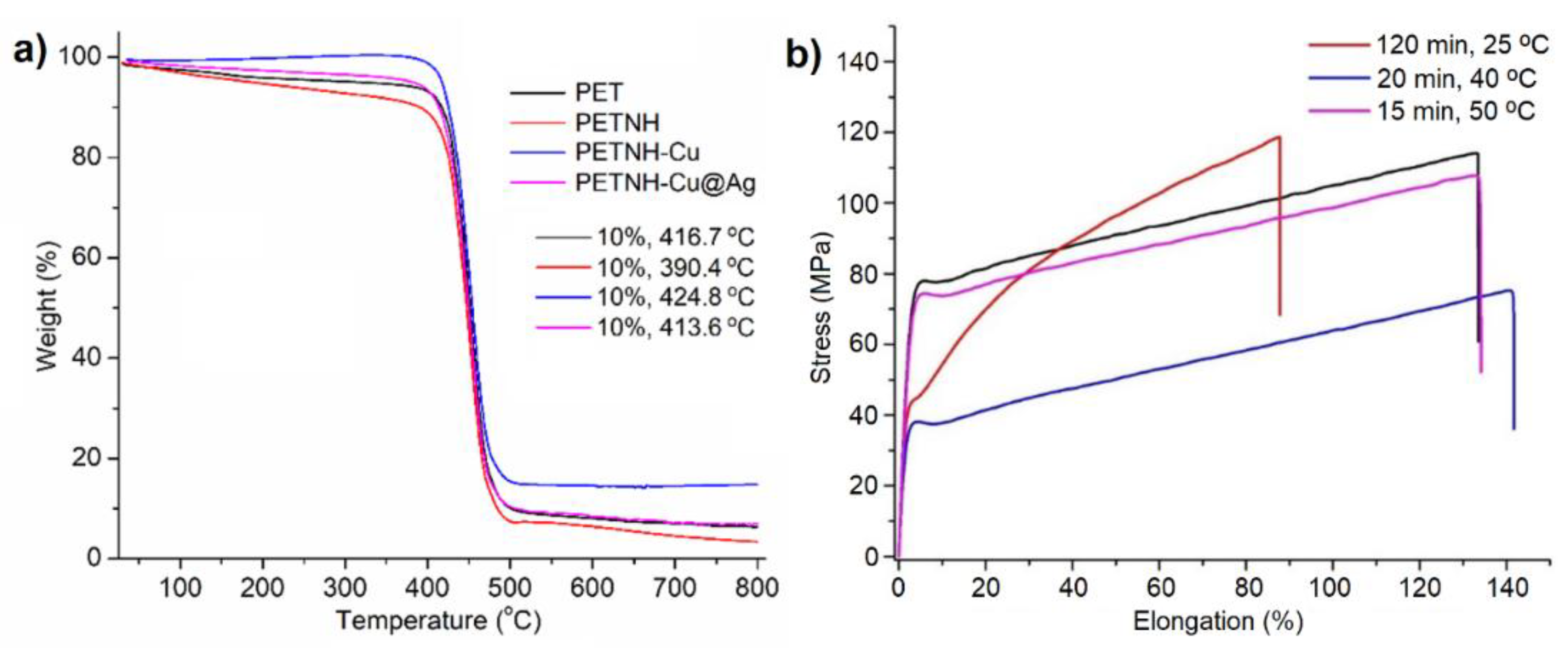

3.3. Thermal Analysis

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) under a nitrogen atmosphere (

Figure 3a) showed that the films exhibited similar thermal decomposition temperatures, with onset between 457.1 and 460.3 °C and a 10 wt% loss between 390.4 and 424.8 °C. These results indicate that chemical functionalization has a minimal impact on the thermal stability of the PET matrix, likely because the modifications are limited to the film surface. The thermogram of the PETNH film showed the lowest temperature for a 10% loss, indicating a higher concentration of volatile compounds, such as occluded water, attributed to the greater hydrophilicity generated by the amino groups on the surface. Furthermore, the residual mass after decomposition was comparable in most samples, except for the PETNH film, which showed a reduced residual yield. Taken together, these results suggest that surface functionalization and nanoparticle incorporation do not significantly compromise PET’s inherent thermal properties.

3.4. Mechanical Properties

The mechanical properties of PET functionalized by aminolysis allowed for the evaluation of the impact of this reaction on the films. Key parameters, including maximum tensile strength, strain at break, Young’s modulus, and energy absorbed, were measured via uniaxial tensile testing; the results are summarized in

Figure 3b and

Table 2.

Unmodified PET exhibited a maximum tensile strength of 114.44 MPa, an elongation of 132.87%, and a high Young’s modulus (2929.8 MPa), demonstrating its high strength and ductility. Samples subjected to aminolysis at 25 °C for 120 minutes showed a slightly higher maximum tensile strength (119.08 MPa) but a significant decrease in strain to 87.8%, indicating increased brittleness associated with surface microcracks observed under microscopy.

On the other hand, films treated at 40 °C for 20 minutes exhibited a notable reduction in maximum stress (75.48 MPa) but high elongation (141.6%), suggesting a less strong but more ductile material, consistent with surface irregularities and intermediate weight loss (

Table 2). Finally, the sample processed at 50 °C for 15 minutes maintained mechanical properties similar to pristine PET with a maximum stress of 108.79 MPa and an elongation of 134.02%, confirming that functionalization under these conditions does not significantly compromise mechanical performance.

These results demonstrate that aminolysis conditions critically affect the balance between functionalization and structural stability: lower temperatures preserve strength but increase brittleness; intermediate temperatures reduce strength but improve ductility, reflecting different types of damage to the polymer network.

3.5. SEM y EDS Studies

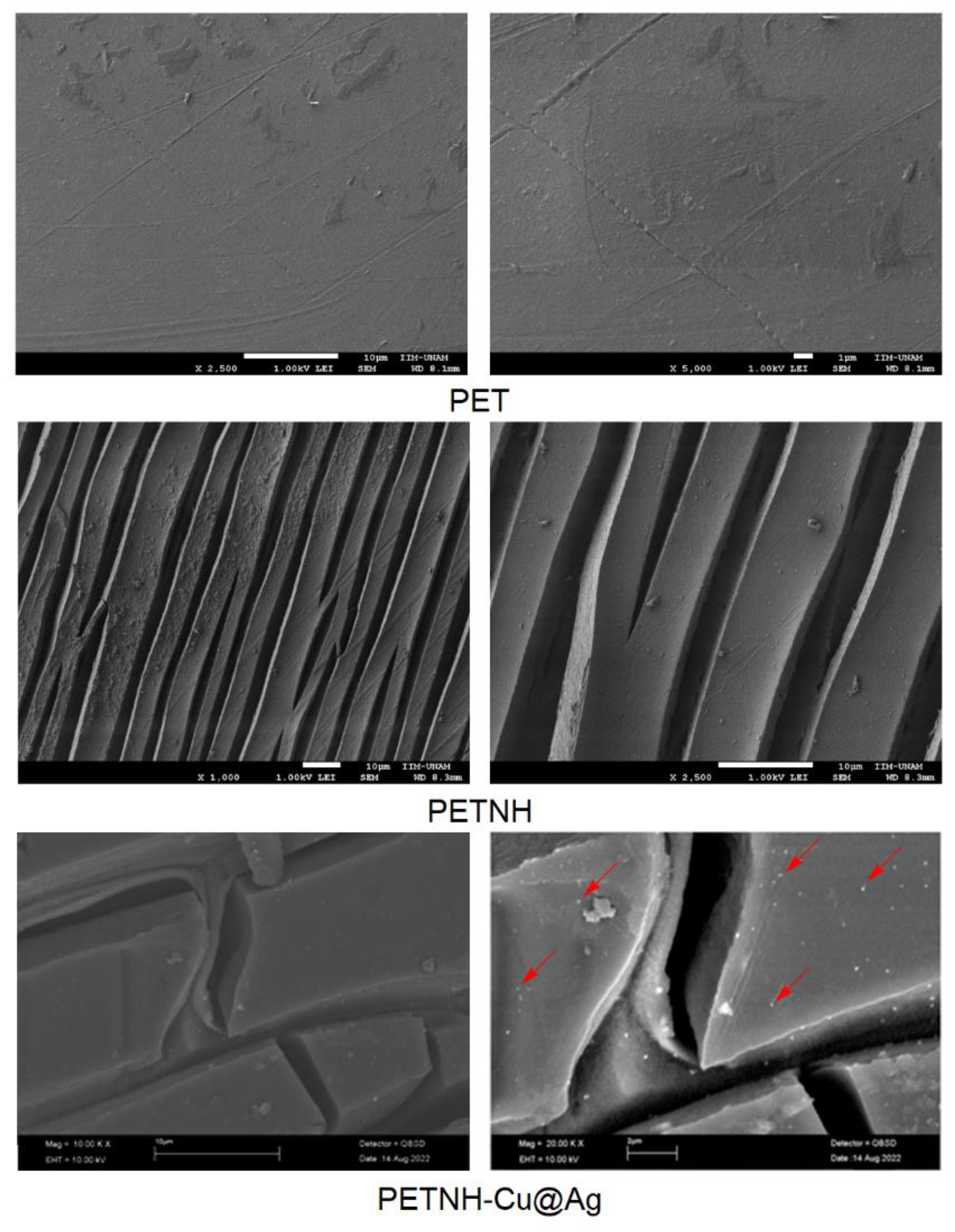

The SEM studies (

Figure 4) illustrate the morphological changes on the film surfaces induced by chemical reactions. The pristine PET film exhibits a smooth surface with minimal roughness and no visible cracks. Following the aminolysis modification, the surface developed elongated, layered structures resembling increased roughness with evident microcracks. In the PETNH-Cu@Ag samples, SEM images reveal well-dispersed nanoparticles firmly anchored on the amino-functionalized PET surface. These observations confirm that chemical functionalization and nanoparticle incorporation significantly alter the surface morphology, potentially enhancing the material’s antimicrobial properties.

Additionally, EDS mapping (

Figure 5) revealed the presence of carbon and oxygen atoms in the PET film, while a uniform nitrogen distribution was detected in PETNH, consistent with previous spectroscopic studies. Uniformly distributed copper and silver atoms were identified in the PETNH-Cu@Ag films, confirming the presence of Cu@Ag nanoparticles. A lower concentration of copper atoms was also observed, suggesting that the copper nanoparticles were coated with silver atoms. These findings are consistent with XPS studies, confirming that chemical functionalization and nanoparticle incorporation significantly modify the surface morphology

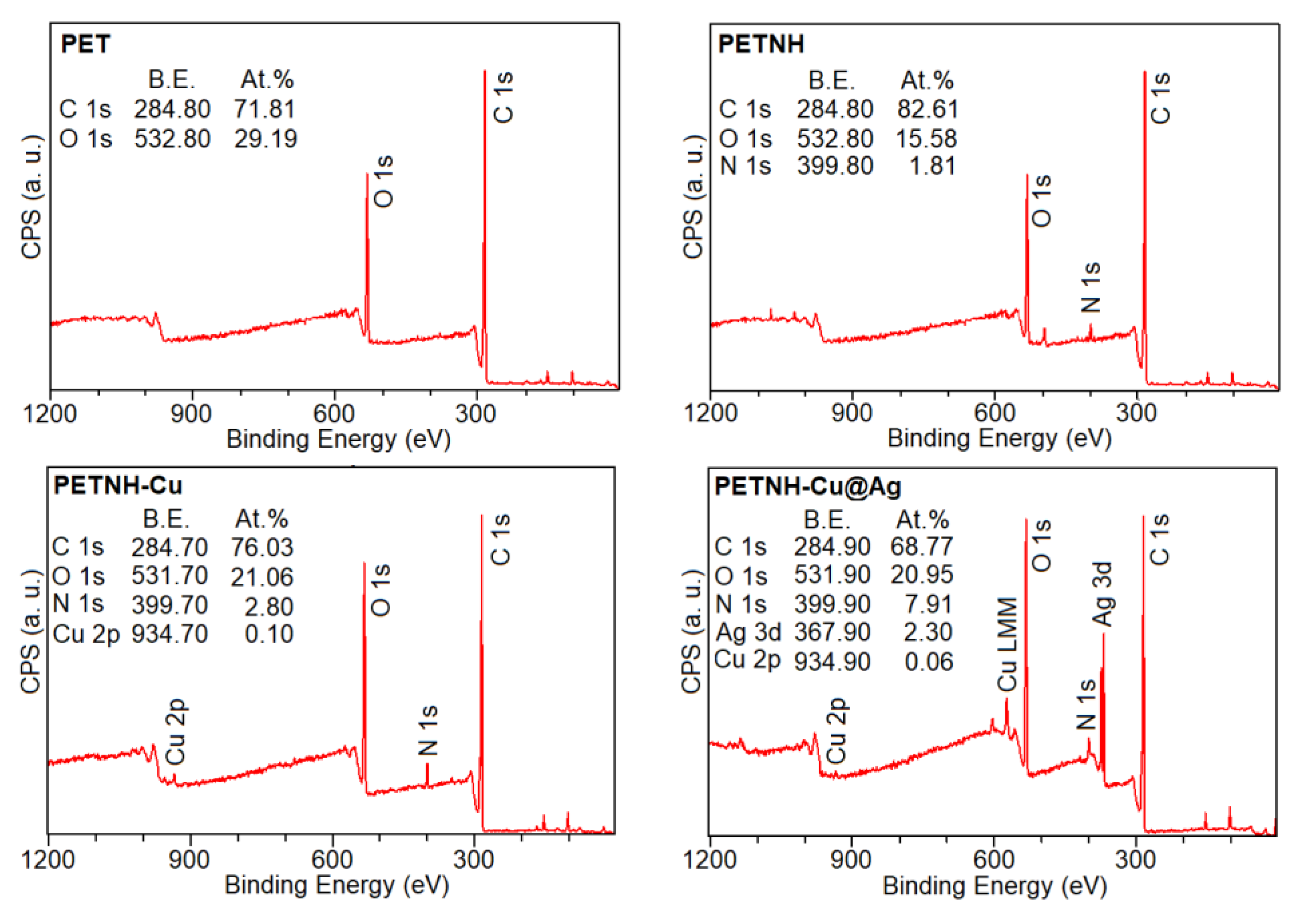

3.6. XPS Studies

XPS spectroscopy studies revealed the elemental compositions of PET, PETNH, PETNH-Cu, and PETNH-Cu@Ag films, showing characteristic peaks for carbon (C1s at 285.0 eV) and oxygen (O1s at 531.0 eV) in the PET films. Additionally, a peak corresponding to nitrogen (N1s at 399.4 eV) was observed in the PETNH films, while the PETNH-Cu and PETNH-Cu@Ag films, their corresponding doublet to copper (Cu2p3/2 934.70 and Cu2p1/2 953.06 eV) silver (368.0 eV (Ag 3d

5/

2) and 374.0 eV Ag 3d

3/

2) were also observed, suggesting the presence of copper and silver in the form of Cu@Ag nanoparticles as it was confirmed by the SEM images (

Figure 6) [

24,

25].

The atomic composition of the films was determined by integrating the XPS peaks and applying appropriate sensitivity factors. The atomic composition of the carbon and oxygen in the films is listed in

Figure 6, which is consistent with that of PET. The results indicated a decrease in the proportion of O1s due to the presence of N1s assigned to the covalent coating of amino groups on the PETNH films. Furthermore, the results of the PETNH-Cu@Ag showed that the atomic composition of the PETNH surface for O1s and C1s was altered by the presence of the Cu@Ag nanoparticles. In addition, the atomic percentage of Cu (0.10%) decreased after the formation of Cu@Ag nanoparticles, due to oxidation of the Cu, releasing copper ions into the reaction medium and possibly covering the Cu nanoparticle with Ag atoms to form the Cu@Ag nanoparticles.

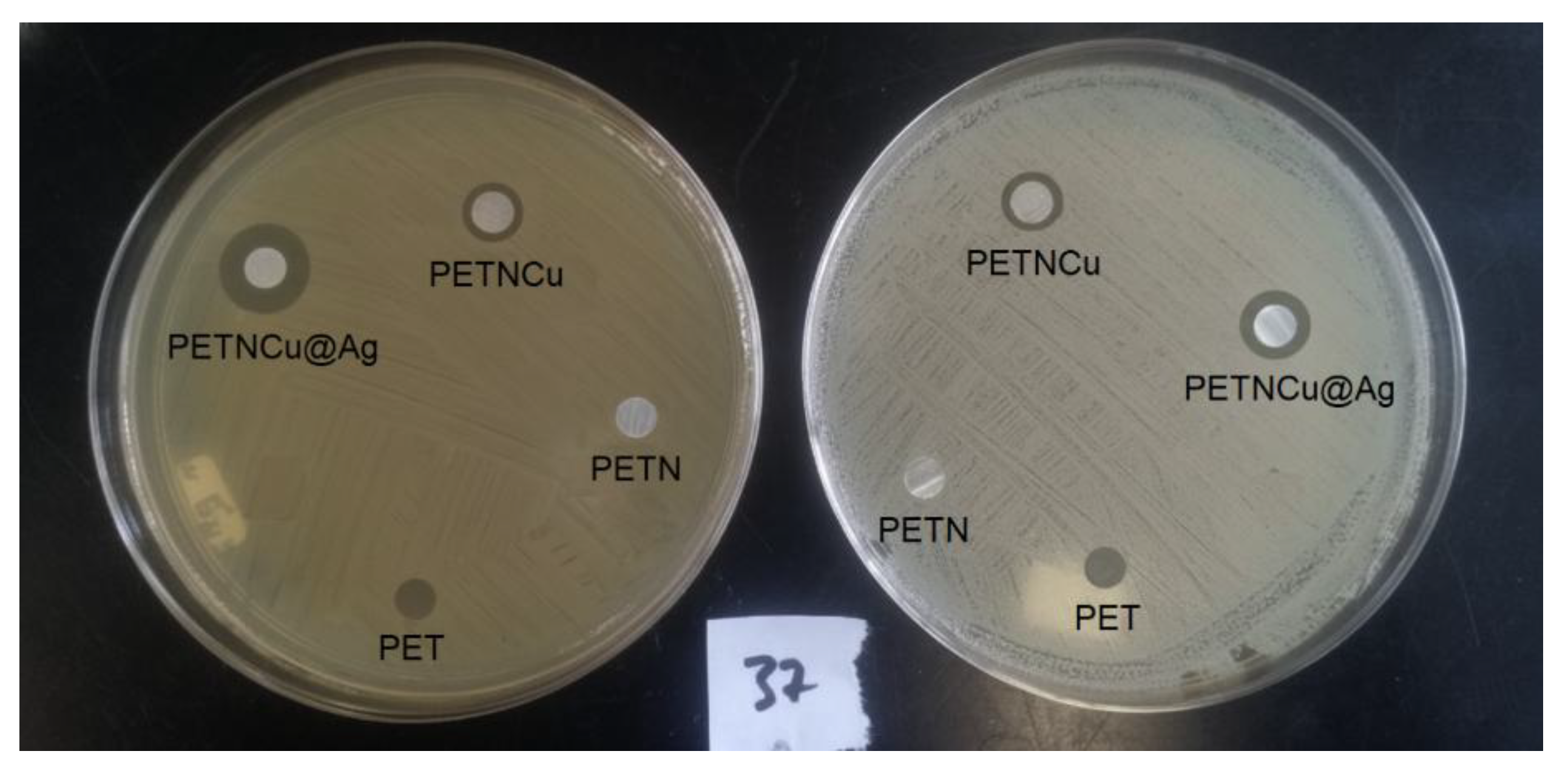

3.7. Microbiological Tests

The antibacterial capacity of films loaded with PETNH-Cu@Ag nanoparticles was evaluated against Gram-positive Staphylococcus aureus and Gram-negative Escherichia coli at 37 °C and pH 7 (

Figure 7). The study included PET, PETNH, PETNH-Cu, and PETNH-Cu@Ag films. Cu@Ag nanoparticles loaded on PETNH exhibited significantly enhanced antimicrobial activity against S. aureus compared to E. coli, with inhibition zones reaching maximum areas of 1.14 cm

2 and 0.35 cm

2, respectively. In contrast, PETNH-Cu films showed substantially smaller inhibition zones, 0.33 cm

2 (S. aureus) and 0.21 cm

2 (E. coli). These findings emphasize the critical role of silver nanoparticle coating in significantly enhancing the antimicrobial properties of PET films, highlighting their potential for applications requiring effective microbial inhibition.

5. Conclusions

The functionalization of PET with amino groups was successfully achieved via aminolysis with an optimized degradation matrix, yielding a maximum density of 276.13 pmol/mm2. This modification allowed for the formation, loading, and stabilization of Cu@Ag nanoparticles on the surface of the PETNH films. SEM micrographs revealed the appearance of surface cracks in the PETNH films, attributable to the partial degradation of the PET, and confirmed the presence of the Cu@Ag nanoparticles. EDS studies showed homogeneous functionalization of the PET surface with amino groups, as well as a uniform distribution of the Cu@Ag nanoparticles. The mechanical and thermal properties of the PETNH-Cu@Ag films showed minimal changes compared to unmodified PET, suggesting that the functionalization was limited to the surface of the material. In conclusion, the aminolysis process and the incorporation of nanoparticles did not significantly affect the intrinsic properties of PET and provided effective antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, expanding its potential applications where bacterial inhibition is needed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.G.F.-R.; methodology, G.G.F.-R., O.F.-E., and E.M.; software, G.G.F.-R.; validation, E.D., R.V.-G., and E.B.; formal analysis, O.F.-E., G.G.F.-R.; investigation, O.F.-E., G.G.F.-R, and E.M.; resources, R.V.-G, E.M., and E.B.; data curation, G.G.F.-R.; writing-original draft preparation, G.G.F.-R, and E.M.; writing-review and editing, E.M.; visualization, G.G.F.R.; supervision, E.M. R.V.-G, E.B.; project administration, E.M., R.V.-G, and E.B.; funding acquisition, R.V.-G., E.M., and E.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.

Funding

This work was supported by the University of Guadalajara under PROSNI 2022. Dirección General de Asuntos del Personal Académico (DGAPA), Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México under Grant IN204223. Support Program for Technological Research and Innovation Projects under PAPIIT IG100220 and National Council of Science and Technology under CONACyT CF-19 No 140617. Call for basic scientific research CONACYT 2017–2018 del “Fondo Sectorial de Investigación para la educación CB2017-2018” (Grant A1-S-29789). CONAHCyT postdoctoral fellowship provided to G. G. Flores-Rojas (CVU 407270) and master fellowship provided to O. FARIAS-ELVIRA (CVU 1340712).

Institutional Review Board Statement

No applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

No applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No applicable.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to M. Sc. G. Cedillo, M. Sc. E. Hernandez-Mecinas, M. Sc. L. Huerta, and M. Sc. C. Flores-Morales from the Materials Research Institute, UNAM, Ph. D. B. Leal-Acevedo from Nuclear Sciences Institute, UNAM, and Prof. A. Camacho-Cruz from Faculty of Chemistry for their technical assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Flores-Rojas, G.G.; López-Saucedo, F.; Vázquez, E.; Vera-Graziano, R.; Buendía-González, L.; Mendizábal, E.; Bucio, E. Nanoengineered Antibacterial Coatings and Materials. In Antimicrobial Materials and Coatings; Elsevier, 2025; pp. 177–213. ISBN 978-0-323-95460-0. [Google Scholar]

- Samad, U.A.; Alam, M.A.; Chafidz, A.; Al-Zahrani, S.M.; Alharthi, N.H. Enhancing Mechanical Properties of Epoxy/Polyaniline Coating with Addition of ZnO Nanoparticles: Nanoindentation Characterization. Progress in Organic Coatings 2018, 119, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Cabezon, C.; Salvo-Comino, C.; Garcia-Hernandez, C.; Rodriguez-Mendez, M.L.; Martin-Pedrosa, F. Nanocomposites of Conductive Polymers and Nanoparticles Deposited on Porous Material as a Strategy to Improve Its Corrosion Resistance. Surface and Coatings Technology 2020, 403, 126395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Rojas, G.G.; López-Saucedo, F.; Vera-Graziano, R.; Magaña, H.; Mendizábal, E.; Bucio, E. Silver Nanoparticles Loaded on Polyethylene Terephthalate Films Grafted with Chitosan. Polymers 2022, 15, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabagh, S.; Bahramian, A.R.; Kokabi, M. SiAlON Nanoparticles Effect on the Corrosion and Chemical Resistance of Epoxy Coating. Iran Polym J 2012, 21, 837–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elzahaby, D.A.; Farrag, H.A.; Haikal, R.R.; Alkordi, M.H.; Abdeltawab, N.F.; Ramadan, M.A. Inhibition of Adherence and Biofilm Formation of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa by Immobilized ZnO Nanoparticles on Silicone Urinary Catheter Grafted by Gamma Irradiation. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Yang, Z.; Tay, S.L.; Gao, W. Photocatalytic TiO2 Nanoparticles Enhanced Polymer Antimicrobial Coating. Applied Surface Science 2014, 290, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramyadevi, J.; Jeyasubramanian, K.; Marikani, A.; Rajakumar, G.; Rahuman, A.A. Synthesis and Antimicrobial Activity of Copper Nanoparticles. Materials Letters 2012, 71, 114–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya, M.; Venkatesan, R.; Deepa, S.; Sana, S.S.; Arumugam, S.; Karami, A.M.; Vetcher, A.A.; Kim, S.-C. Green Synthesis, Characterization, Antibacterial, and Antifungal Activity of Copper Oxide Nanoparticles Derived from Morinda Citrifolia Leaf Extract. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 18838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.; Cai, G.; Wu, J.; Ran, J.; Wang, X. UV Protective PET Nanocomposites by a Layer-by-Layer Deposition of TiO2 Nanoparticles. Colloid Polym Sci 2017, 295, 2163–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Król-Morkisz, K.; Pielichowska, K. Thermal Decomposition of Polymer Nanocomposites With Functionalized Nanoparticles. In Polymer Composites with Functionalized Nanoparticles; Elsevier, 2019; pp. 405–435. ISBN 978-0-12-814064-2. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, K.V. Nanotechnology and Energy, 1st ed.; Wong, K.V., Ed.; Jenny Stanford Publishing, 2017; ISBN 978-1-315-16357-4. [Google Scholar]

- Carbone, M.; Donia, D.T.; Sabbatella, G.; Antiochia, R. Silver Nanoparticles in Polymeric Matrices for Fresh Food Packaging. Journal of King Saud University - Science 2016, 28, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrinceanu, N.; Bucur, S.; Rimbu, C.M.; Neculai-Valeanu, S.; Ferrandiz Bou, S.; Suchea, M.P. Nanoparticle/Biopolymer-Based Coatings for Functionalization of Textiles: Recent Developments (a Minireview). Textile Research Journal 2022, 92, 3889–3902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Königer, T.; Münstedt, H. Coatings of Indium Tin Oxide Nanoparticles on Various Flexible Polymer Substrates: Influence of Surface Topography and Oscillatory Bending on Electrical Properties. J Soc Info Display 2008, 16, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhang, M.; Pang, L.; Yang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, J.; Wu, G. Fabrication of Highly Durable Polysiloxane-Zinc Oxide (ZnO) Coated Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) Fabric with Improved Ultraviolet Resistance, Hydrophobicity, and Thermal Resistance. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 2019, 537, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Santos, C.; Yubero, F.; Cotrino, J.; González-Elipe, A.R. Surface Functionalization, Oxygen Depth Profiles, and Wetting Behavior of PET Treated with Different Nitrogen Plasmas. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2010, 2, 980–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousif, M.; Zhang, M.; Hussain, B.; Khan, T.; Mahar, F.K.; Shaikh, A.R.; Ali, H.F.; Ahmed, R.; Mehdi, M. Revolutionizing PET Fabric Performance with Advanced Metal Deposition Techniques. The Journal of The Textile Institute 2025, 116, 2111–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, T.V.; Maydannik, P.S.; Cameron, D.C. Molecular Layer Deposition of Polyethylene Terephthalate Thin Films. Journal of Vacuum Science & Technology A: Vacuum, Surfaces, and Films 2012, 30, 01A121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Alba, E.; Dionisio, N.; Pérez-Calixto, M.; Huerta, L.; García-Uriostegui, L.; Hautefeuille, M.; Vázquez-Victorio, G.; Burillo, G. Surface Modification of Polyethylenterephthalate Film with Primary Amines Using Gamma Radiation and Aminolysis Reaction for Cell Adhesion Studies. Radiation Physics and Chemistry 2020, 176, 109070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Bedi, R. Mechanical and Durability Properties of Sustainable Composites Derived from Recycled Polyethylene Terephthalate and Enhanced with Natural Fibers: A Comprehensive Review. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noel, S.; Liberelle, B.; Robitaille, L.; De Crescenzo, G. Quantification of Primary Amine Groups Available for Subsequent Biofunctionalization of Polymer Surfaces. Bioconjugate Chem. 2011, 22, 1690–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinares, R.; Machaca, V.; Lozano, F.; Quispe, A.; Ccopa, R.; Calsin, B. Comparaciones de La Espectroscopía Infrarroja Por Transformada de Fourier (FTIR), Parámetros Colorimétricos y Porcentaje de Medulación En Fibra de Vicuña. Rev. investig. vet. Perú 2023, 34, e25953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, A.; Qu, S.; Li, K.; Hou, Y.; Teng, F.; Cao, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z. One-Pot Synthesis and Self-Assembly of Colloidal Copper(I) Sulfide Nanocrystals. Nanotechnology 2010, 21, 285602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishoyi, A.K.; Sahoo, C.R.; Samal, P.; Mishra, N.P.; Jali, B.R.; Khan, M.S.; Padhy, R.N. Unveiling the Antibacterial and Antifungal Potential of Biosynthesized Silver Nanoparticles from Chromolaena Odorata Leaves. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 7513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).