1. Introduction

According to the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), a biofilm is an aggregate of microorganisms in which the forming units adhere to each other and/or to a surface. This is frequently achieved by embedding within a self-produced matrix of extracellular polymeric substances (EPSs) [

1]. The bacteria in biofilms are significantly more tolerant to antibiotics, biocides, and environmental stress, such as the immune system attack of a host organism. Furthermore, the proximity between units in biofilm facilitates the exchange of gene transfer and metabolized products [

2]. Therefore, to prevent the proliferation of microorganisms in different hosts, it is important to avoid adhesion to surfaces. This strategy includes reducing surface roughness or anti-adhesive compounds that repel bacterial cells using physical mechanisms [

3]. However, providing antimicrobial activity on surfaces is desirable to prevent clinical infections in severe surgical practice. This protection can be proportionated by antibiotics, antimicrobial proteins, enzymes, quorum sensing inhibitors, nanoparticles, and others [

4]. In this regard, one of the most versatile and interesting techniques for obtaining antibacterial surfaces for biotechnological applications are the layer-by-layer techniques (LbL) [

5]. LbL techniques alternate the physisorption of oppositely charged polyelectrolytes, whereby electrostatic interactions between molecules are critical to control the stability/degradability [

6]. The main aim of the LbL technique is the multilayer assembly of polymers, colloids, or biomolecules on substrates to form a surface coating that provides superior control and versatility to other film deposition methods, especially on micro and nanostructured surfaces [

7]. In that sense, nanoporous silicon (nPSi) can be an excellent biomaterial for LbL assemblies due to its biocompatibility, biodegradability, and bioresorbability [

8]. nPSi consists of silicon nanocrystals embedded in a porous amorphous matrix. It has been successfully used in many

in-vitro and

in-vivo applications such as drug delivery, diagnosis, imaging, complex biochip systems, and tissue engineering [

9].

On the other hand, various synthetic polymers can be used to prepare multilayers but often lack bioactivity and biocompatibility, resulting in adverse side effects [

10]. In this context, due to its natural origin, biocompatibility, biodegradability, and non-cytotoxicity, chitosan (CHI) is an excellent antibacterial candidate [

11]. The antibacterial action of CHI is mainly due to the electrostatic interaction between its protonated amino groups, positively charged in acidic and moderately acidic media, and the negatively charged bacterial membrane, resulting in the leakage of the cytoplasmic content and consequently the death of the microorganisms [

12]. However, CHI is less effective against Gram-negative than Gram-positive bacteria because they are protected by the outer cell membrane that constitutes the outer surface of the cell wall and can hinder its interaction with CHI [

12]. In this regard, it is recommended the addition of active antimicrobial species, for example, antimicrobial peptides or silver nanoparticles (AgNPs). AgNPs are well-known antibacterial agents with low toxicity to mammalian cells at controlled concentrations [

13,

14]. The antibacterial mechanism of AgNPs is related to their easy adsorbtion to the membrane surface of bacteria through electrostatic interactions, forming permeable pits causing an osmotic collapse in the cells [

14]. CHI and Ag can be combined by the CHI sorption abilities and capacity to form chelate compounds with metal ions, such as Ag

+ [

15], which could generate synergistic antibacterial effects. Thus, CHI-Ag, a polycation complex, can be assembled LbL with carboxymethylcellulose (CMC), a water soluble cellulose derived polyanion [

16].

The five more important routes to assemble films by LbL are: (i) immersive or dip, (ii) spin, (iii) spray, (iv) electromagnetic, and (v) fluidic assembly, being the most frequently employed dip-coating (DC) and spin-coating (SC) because they are simple, versatile, and cost-effective for the fabrication of thin-film coatings [

6,

17].

In the present work, we focus on synthesizing antibacterial CMC/CHI-Ag nanofilms assembled on nPSi by two LbL routes: dip-coating and spin-coating. The antibacterial synergic effect of CMC/CHI-Ag/nPSi was systematically studied against Escherichia coli (Gram-negative), and Staphylococcus aureus (Gram-positive) bacteria strains as model microorganisms.

2. Experimental Approach

2.1. Polyelectrolyte solutions

Two polymers were used for the preparation of electrolyte solutions: carboxymethylcellulose (CMC, molecular weight ≈ 9×104 g/mol, degree of substitution ≈ 0.9), and chitosan (CHI, molecular weight ≈ 5×104 g/mol, 75–85% deacetylated) (Sigma–Aldrich, USA). Polyelectrolyte solutions were prepared by dissolving the respective polymer in distilled water at concentrations of 1% (w/v). In the case of CMC, pH was adjusted to 4. CHI solution was also prepared with 100 mM glacial acetic acid. Then, AgNO3 salt was dissolved in CHI solution at a concentration of 1 mM and adjusted to pH = 4.0 (CHI-Ag). All solutions were stirred overnight.

2.2. Fabrication of nPSi substrate

The fabrication of nanostructured porous silicon substrates (nPSi) was performed using the galvanostatic method by electrochemical etching of single-crystalline p-type Si wafers (boron-doped, orientation <100>, resistivity 0.001–0.005 Ω·cm) in a 1:2 electrolyte solution of hydrofluoric acid:ethanol. The applied current density was set to 80 mA/cm

2 for 120 s. The as-prepared nPSi layers were stabilized by a chemical oxidation process in H

2O

2 (30% v/v) overnight, as previously reported [

18]. Finally, nPSi substrates were dried under nitrogen streamflow and used as the template for silver deposition. Si wafers were purchased from University Wafer, South Boston, USA, and hydrofluoric acid, ethanol and H

2O

2 were acquired from Merck, Santiago, Chile.

2.3. Formation of the nPSi-(CHI-Ag/CMC) composite layers

In order to fabricate the nPSi-(CHI-Ag/CMC)X composite layers (X = number of cycles), one of two thin-film deposition techniques were used: (i) CDC or (ii) CSC. The standard deposition for the CDC series comprised the alternate immersion of nPSi substrates in the CHI-Ag and CMC solutions for 15 min; each deposition was followed by three consecutive distilled water rinse steps of 2, 1, and 1 min, respectively. The CDC assembling was repeated for 3.5, 6.5, 9.5, and 12.5 cycles in each case with the CHI-Ag coating on the top. On the other hand, the standard deposition for the CSC series consisted of alternating 500 μL of CHI-Ag and CMC solutions onto the nPSi substrate at 3000 rpm during 60 s; each deposition was followed by 500 μL of distilled water rinse step, also at 3000 rpm during 60 s. This process was repeated for 3.5, 6.5, 9.5, and 12.5 cycles. For both techniques, after samples were obtained at different cycles, they were immersed into 1 mM ascorbic acid solution (ASC) for 3 h to reduce the ionic silver and stabilize the silver nanoparticles. Finally, the samples were washed with ultrapure water at pH 4 and dried at room temperature. All chemical products were acquired from Merck, Santiago, Chile.

2.4. Physicochemical characterization techniques

The first cycle of nPSi-(CHI-Ag/CMC) by LbL depositions was monitored by UV–Vis, Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopies. UV–Vis absorbance spectra were recorded using a Jasco V-750 double-beam spectrophotometer (Hachioji, Tokyo, Japan).

FTIR spectroscopy was used to identify the functional groups in the nPSi-(CHI-Ag/CMC) multilayers. The FTIR spectra were obtained using a Spectrum Two FTIR Spectrometer in the 4000-450 cm-1 range with 4 cm-1 resolution.

XPS was used to determine the surface chemical composition of the nPSi-(CHI-Ag/CMC). XPS spectra were acquired in the Surface Analysis Station 150 XPS RQ300/2 (TAIB Instruments) equipped with a hemispherical electron analyzer, using an Mg-anode X-ray source. The pass energy was set at 20 eV, giving an overall resolution of 0.9 eV. All XPS binding energies were referenced to the adventitious C 1s carbon peak at a binding energy of 284.6 eV to compensate for the surface charging effects. The fitting of the XPS spectra was carried out using the CasaXPS software.

The 3.5, 6.5, 9.5, and 12.5 cycles of nPSi-(CHI-Ag/CMC) obtained by CDC and CSC techniques were characterized by field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM), X-ray fluorescence (XRF), Rutherford backscattering spectroscopy (RBS), X-ray diffractometry and Raman spectroscopy.

The surface and cross-sectional morphologies of the samples were observed by FESEM (Philips XL-40FEG), operating with an acceleration potential of 10 keV. Images were obtained from the FESEM images that were processed using freely available ImageJ software.

XRF measurements were carried out using an irradiation system consisting of an X-ray generator (Teledyne ICM model 160D) with the ability to operate at voltages of 10–160 kV, tube currents of 1.0–10 mA and 900 W of power. The generator had a Tungsten (W) anode and 800 μm Beryllium window. The equipment was configured for irradiations with voltages of 50 kV and 2.0 mA. A 0.8 cm long lead collimator and an internal hole of 3 mm in diameter permits irradiating a circular area of 1.5 cm diameter of the analyzed samples at a tube-sample distance of 15 cm. The detection system consisted of a Canberra low energy germanium detector (LE-Ge) model GL1010 based on semiconductor diodes having a P-I-N structure with intrinsic region (I) sensitive to ionizing radiation, particularly X- and g-rays from 3 keV to 2 MeV. The GL1010 had a detector crystal with a area of 1000 mm2 and 1 cm thickness and characterized by an energy resolution of about 300 eV at 5.9 keV. The LE-Ge detector was operated with the digital pulse processor (DPP) AMPTEK® model HPGe-PX5.

In-depth profiling of the AgNPs infiltration into nPSi layers was studied using RBS. RBS experiments were carried out at the standard beamline of the Centro de Micro-Análisis de Materiales (CMAM), which hosts a 5 MV Cockroft-Walton tandetron accelerator, For the measurements, 2 MeV He+ ions were used. The scattered ions were detected at a scattering angle of 170º with a Si semiconductor particle detector; the samples were oriented in random geometry to avoid channeling through the crystalline substrate. The vacuum was about 5×10–5 Pa. Simulations and spectra fitting was carried out using SIMNRA 7.02 software.

The crystalline structures of nPSi-(CHI-Ag/CMC) composite layers were examined using a Smartlab X-ray diffractometer, with Theta-2 Theta Bragg-Brentano geometry and solid-state D/teX Ultra 250 detector (Rigaku Corporation, Japan). The instrumental alignment was checked against the NIST SMR 660c LaB6 powder standard, and its optic configuration was employed Ni-filtered Cu radiation (30 kV and 40 mA), 0.5° divergence slit, 0.25° anti-scatter slit, and both sides with 5° Soller slits. In preference, patterns were collected in the 10–60° range, counting 0.5°/sec per step of 0.01°. PDXL 2 v.2.7.3.0 software and ICDD 2018 PDF-4 reference database were used for matching.

The Raman spectra were acquired at room temperature using a Renishaw Ramascope 2000 microspectrometer, in the range between 0 and 4000 cm-1, and a 514.5 nm excitation wavelength (green) line from an argon-ion laser. Exciting light was focused on the sample surface with a BH-2 Olympus microscope. The objective had a 50 X magnification and a numerical aperture of NA = 0.85. The laser power on the sample surface was in the order of 1 mW. The integration time for each CCD pixel was 50 s.

2.5. Antibacterial assays

The antibacterial activity of nPSi-(CHI-Ag/CMC)x composite layers was studied against Escherichia coli (Gram-negative) and Staphylococcus aureus (Gram-positive) by the well diffusion method using Muller-Hilton agar. Both bacteria strains were grown overnight at 37 °C with a standard turbidity concentration McFarland 0.5 (108 CFL/mL). Pieces of 5 mm × 5 mm were incubated by triplicate in the well plates for 24 hours at 37 °C without culture media replacement. Micrographs of the surface of composite layers after 24 hours of contact with both kind of bacteria strains were obtained with a CMEX-10 Pro Microscope camera coupled on a JNOEC JSZ4 binocular loupe, and the area covered by bacteria was estimaded by analyzing the images with ImageJ software. nPSi layers were used as control.

Antibacterial rate was calculated as:

where

A is the covered area by bacteria on the control sample (nPSi substrate) and

B is the mean fraction area of bacteria adhered on the composite's layers.

3. Results and discussion

In this study, single nPSi layers produced by electrochemical anodization of silicon wafers were used as substrates for the layer-by-layer deposition of CHI-Ag and CMC. The schematic of the synthesis process is represented in

Figure 1.

Figure 1a shows the fabrication of nPSi substrates via photoassisted electrochemical etching, followed by a H

2O

2 chemical oxidation to stabilize the porous structure. The CDC and CSC methods are depicted in figures 1b and 1c, respectively. In the CDC method, the obtained nPSi substrate was cyclically incubated into CHI-Ag next to CMC solution, after intermediate washes. On the other hand, for the CSC process, CHI-Ag layers were cyclically placed LbL onto CMC by spin-coating after intermediate washes. After the required deposition cycles samples were immersed into ASC in order to reduce Ag

+ ions to Ag

0 [

15]. In this work, final layer with 3.5, 6.5, 9.5 and 12.5 cycles were studied for both methods.

FESEM was used to study the morphology of stabilized nPSi layer before deposition of the CHI-Ag/CMC layers (

Figure 2).

Figure 2a shows a porous surface, with an irregular shape tending to a circular form. The mean pore size estimated was found to be 17±2 nm (

Figure 2b). The cross-section of stabilized nPSi layer has a thickness of ~5.3 µm (

Figure 2c) where the depth of the pores is distinguishable (

Figure 2d).

To gain a deeper insight into the layers deposition during a cycle, UV-Vis, FTIR (both in

Figure 3) and XPS analysis (Figure 4) were performed on the first assembled layers. The complete cycle implies immersion in the ASC for the Ag reduction. UV–Vis reflectance spectra of nPSi-(CHI-Ag/CMC) composite layers fabricated by CDC and CSC are displayed in Figures 3a and 3b, respectively. For both kind of deposition methods, UV-Vis spectra presented a similar behaviour. Oxidized nPSi control showed an almost zero reflectance in the 300-500 nm visible range, and the tipical inteference signal of a thin film of 5 µm of thickness. However, after the first CHI-Ag polication step (nPsi-CHI-Ag), the reflectance is increased in the range of 300 nm to 500 nm, confirming that the layer assembled since the first step. Similalry, the reflectance also increase in that range after the CMC potianaion step (CMC). After the second CHI-Ag polication step (CHI-Ag), the reflectance also increases due to the deposition of the new part of the layer. Finaly, the reflectance showed a low decrease in intensity after the chemical reduction of Ag ions by the ASC. This step is detrimental for the CHI-Ag layer, but to a limited stage since the change of absorption does not appear to affect the underlying CMC layer.

Figure 3c and 3d show the FTIR spectra of the nPSi substrate and after each step of the composite formation during the first cycle of deposition for CDC and CSC methods, respectively. The spectra of nPSi sample displayed bands in the range of 615-666 cm

-1, which corresponds to SiH

x deformation modes overlapping the silicon crystal modes [

19]. At 1220 cm

-1 a band associated with amorphous silicon dioxide (a-SiO

2) [

20] and at 1350 cm

-1 a band attributed to the Si-O wiggling mode [

21] were observed. The band at 3240 cm

-1 correspond to the stretching vibration mode of the OH in the silanol (Si-OH) groups [

22,

23]. These peaks are characteristic of a partially oxidized nPSi [

19], a typical chemical oxidation of nPSi with H

2O

2 [

18]. However, after applying the progressive polymer depositions, in both techniques, these bands exhibited a decrease attributed to the electrostatic interactions between CMC and CHI-Ag. Moreover, the broadening of the band at 3240 cm

-1 can be ascribed to the intermolecular interaction among SiO, CHI-Ag and CMC [

24]. This interaction arises from the characteristic bands of the utilized polymers falling within the range of 3200-3450 cm

-1, associated with the O-H stretching in both polymers, as well as the N-H stretching of CHI [

25]. On the other hand, the high intensity of band in this range in the CDC spectra (

Figure 3c) may be attributed to enhanced polymer penetration into the nanopores, resulting in a surface with a greater concentration of silanol groups from nPSi. Finally, in both thechniques, the ASC spectra does not present any peak due to the reduction of the ionic silver in CHI-Ag and stabilization of the obtained Ag nanoparticles [

15], wich abosrbe the IR radiation.

The surface chemical composition of the composites was studied by XPS.

Figure 4 shows the XPS spectra of nPSi-(CHI-Ag/CMC) composite layers fabricated by CDC (

Figure 4a) and CSC (

Figure 4b) after one complete cycle. In general, the survey spectra for both CDC and CSC methods evidenced the presence of C, O, Ag, N, and Si. The results show that the C 1s and O 1s signals increase while Si 2p signal decreases for both CDC and CSC methods with the increasing number of steps on the cycle, due to the formation of the polymer layers on the top of the nPSi thin film. In adddtion, after the final step, Ag 3d signal was more intense for CDC than the CSC method.

Figure 4c shows XPS spectra of Si 2p band of nPSi and after the final step by CSC and CDC method. The two main typical contributions of oxidized porous silicon layer can be observed on the nPSi sample: one located at 99.2 eV correlated to Si-Si bonds and the other at 103.2 eV which correspond to Si-O bonds [

26]. After the first cycles for both methods, similar XPS spectra were obtained, suggesting that the polymer layer is formed on the top of nPSi thin film, without modifying its physico-chemical properties. In order to study the formation of the Ag nanoparticles inside the polymer layer,

Figure 4d show the high resolution XPS spectra of Ag 3d bands, after the final step of the cycle for both methods. It can be observed that by CDC technique, Ag 3d bands are more defined and with higher intensity than the CSC ones, suggesting that a higher amount of Ag was reduce by this method. However, both spectra could be fitted with the same two doublet with a spin-robit separation of 6 eV and an area ratio of 2/3. The first one located at 367.4 eV, which is related to metallic Ag-Ag bonds, and another one shifted to higher binding energy which can correspond to oxidized species of Ag, such as Ag-O and Ag

2O [

27,

28,

29]. These results induce that the reduction of silver ions is not only in the form of metallic structure. Instead, some oxidized silver structure are also formed.

To obtain thicker and more stable polymer thin films, in this work we studied the proporties of the nPSi-(CHI-Ag/CMC) composite layer formed applying 3.5, 6.5, 9.5 and 12.5 complete cycles, respectively, using the both methods, CDC and CSC. The cross section FESEM images of nPSi-(CHI-Ag/CMC) composite layer after each cycle studied in this work by the both methods are shown in

Figure 5. For all the samples, the composite thin film is observed on the surface of nPSi layer. For CDC method (

Figure 5a–d), it is notified that the surface layer increases its thickness after each deposition cycle, suggesting a successful LbL deposition. For 3.5 cycles (

Figure 5a), the composite layer is formed almost completely by AgNPs of granular morphology with a particle size around 100 nm. After 6.5 cycles (

Figure 5b), the amount of AgNPs increases as well as the size distribution, raising the thickness of the layer. For 9.5 cycles (

Figure 5c) and 12.5 cycles (

Figure 5d), the formation of an homogeneous composite polymer/AgNPs begins to be most remarkable, in which the amount of AgNPs predominate on the layer. The maximum thickness of the thin film was around 0.8 µm for the cycle 12.5. On the other hand,

Figure 5e–h show cross section images of the composites obtained by CSC method at the same cycles. Similarly to the CDC method, it is evident that an increase in the number of cycles corresponds to a thicker layer, thereby confirming the success of the process. However, in contrast to the CDC method, the morphology of the AgNPs obtained by CSC is mostly in the form of flakes and very few in the form of granules, with a wide range of sizes: from 50 to 500 nm. Furthermore, the composite layer exhibits a predominantly homogeneous distribution of the polymer, which encapsulates the AgNPs. Moreover, the maximum achieved thickness was approximately 1.3 µm at cycle 12.5, as depicted in

Figure 5h.

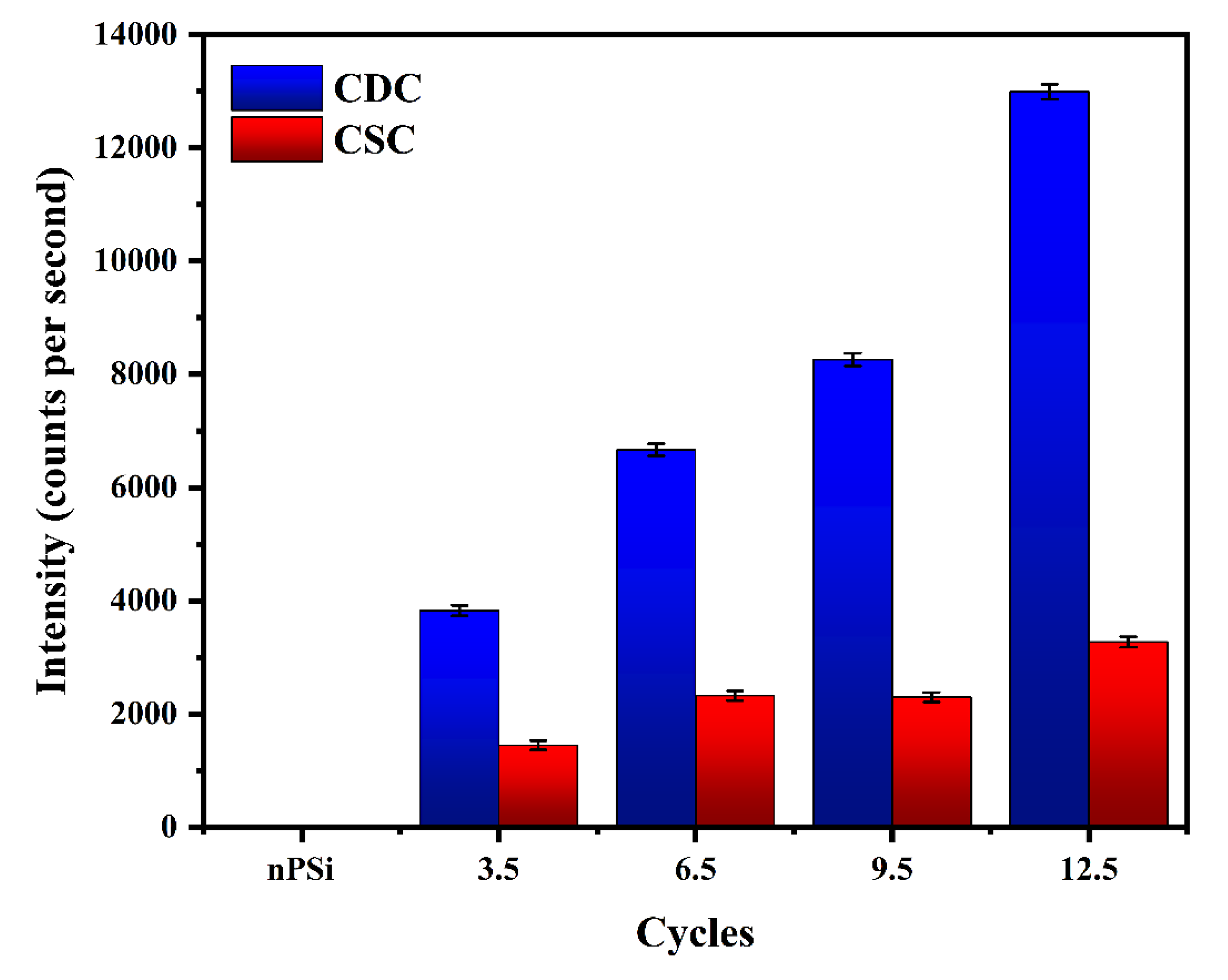

To confirm the presence of Ag on the composite layer, XRF measurements were performed (

Figure 6). The fluorescence signal was determined by measuring the intensity of the Ag Kα line (21.99 keV), which is proportional to the amount of Ag. The Ag fluorescence signal increased significantly according to the number of cycles in the samples obtained by CDC. However, for CSC method, the amount of Ag is clearly lower, in concordance with FESEM images. This result confirms the higher amount of AgNPS obtained by CDC than CSC samples, as it was expected from XPS analysis.

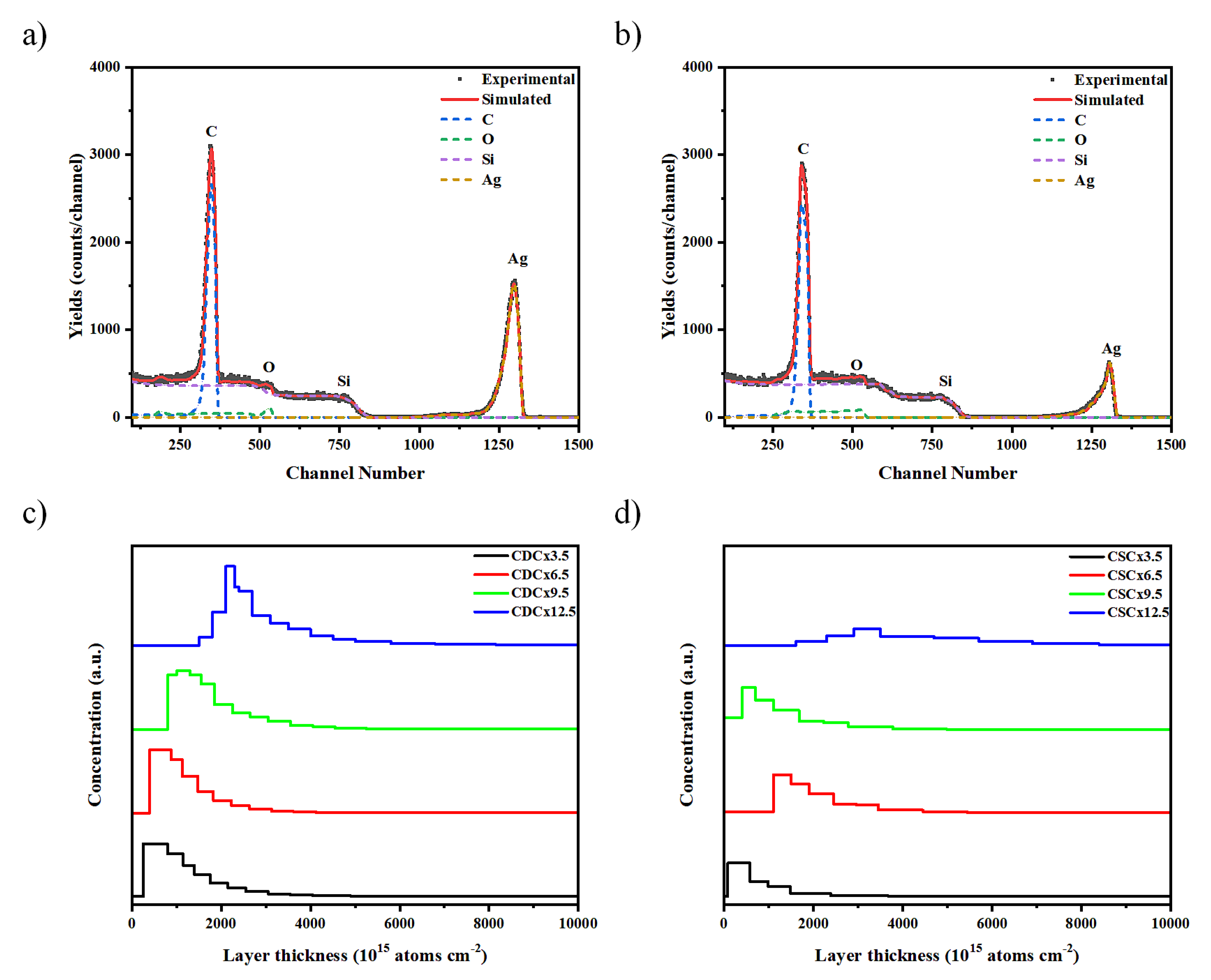

RBS spectroscopy was performed to analyze the diffusion of AgNPs in the different polymer and nPSi layers. Figure 7a and 7b shows the RBS spectra for the composites obtained by CDC and CSC after 12.5 cycles, respectively. Four element related signals can be observed for both samples, corresponding to C, Si, O and Ag. The Ag signal shows a peak at 1295 and 1306 channel number for CDC and CSC, respectively. These signals confirm the presence of silver in the composites, in addition to a deeper infiltration of silver in the CDC composites. On the other hand, there is a significant decrease in the intensity of the silver peaks when the composites are produced by CSC. This diminution could be attributed to a larger Ag particle size [

30], or to a migration of the particles towards the film surface [

31]. Other authors have associated it to a lower number of silver atoms diffusing in the composite [

32].

Figure 7c and 7d shows the depth concentration profiles of silver derived from the RBS spectra at different deposition cycles, for CDC and CSC samples, respectively. The profiles by the CDC method (

Figure 7c) show that the Ag concentration does not vary significantly between the different layers obtained, but there is a difference between cycles 3.5 and 9.5, where the silver tends to be closer to the surface, as opposed to cycle 12.5 where it is found at a greater depth. When analyzing the CSC profiles (

Figure 7d), the Ag signal decreases as the number of cycles increases, at cycle 12.5 it is observed that there is a very low concentration of Ag atoms.

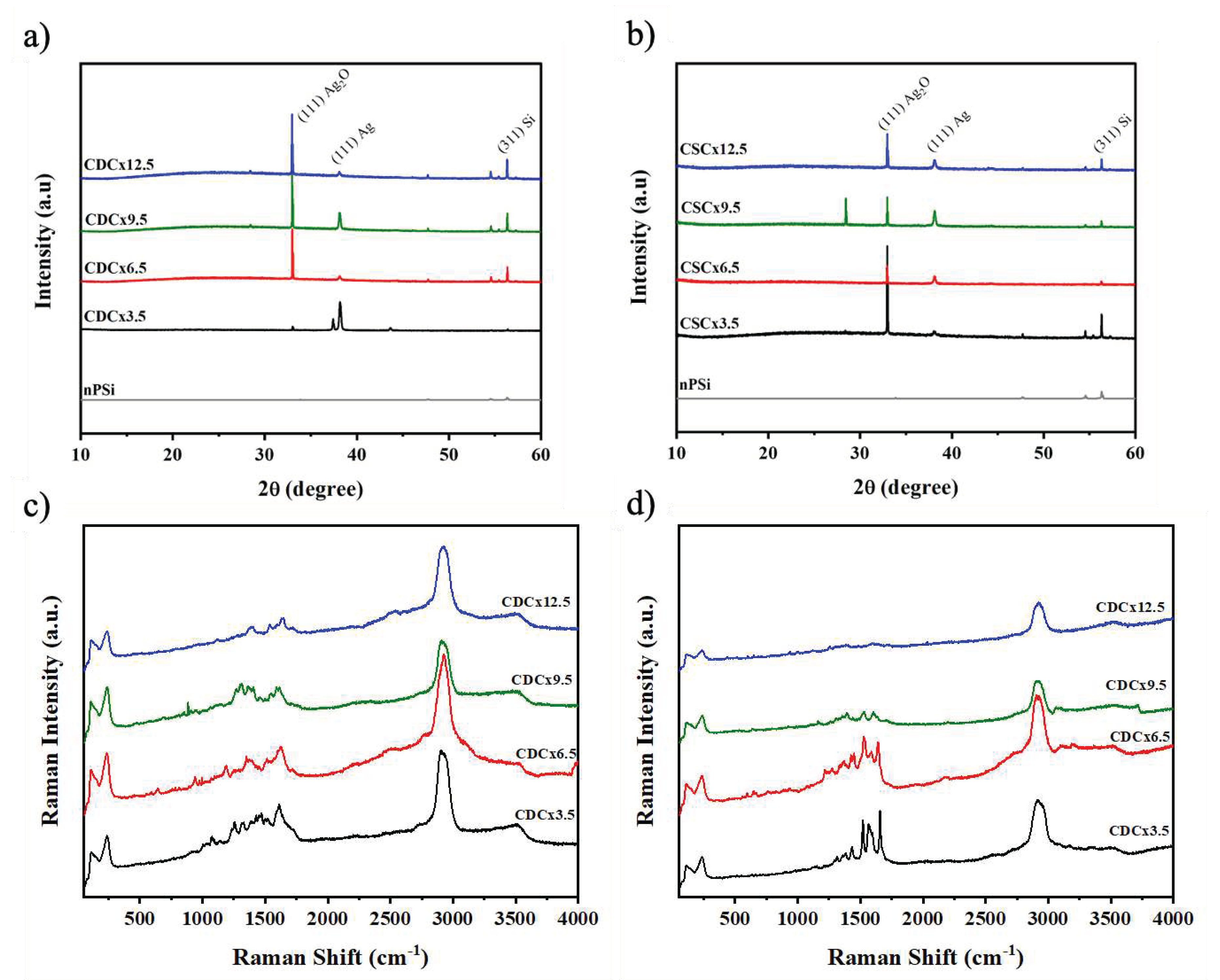

The crystal structure of the nPSi-(CHI-Ag/CMC) composites were analyzed by X-ray diffraction.

Figure 8a shows the peaks of the composites obtained by CDC. The reflection peaks at 32.95°, 38.17° and 56.32º are attributed to the (111) plane of Ag

2O [

33], the (111) plane of metallic silver (Ag) [

33] and the (311) plane of Si, respectively. These peaks could be attributed to the fact that the silver particles obtained are in the nanometer range, which leads to a higher surface area/volume ratio, thus the Ag particles have a high reactivity with oxygen in the air [

15] leading to Ag

2O, in concordance to XPS analysis. The XRD spectra of the composites obtained by the CDC method show an increase in the intensity of the peaks when the number of cycles increases. The composites obtained by CSC (

Figure 8b) show the same peaks associated with Ag, Ag

2O and Si, but their intensity roughly increase with the number of cycles, a similar effect was observed in the XRF characterization (

Figure 6).

Figure 8c and 8d show the Raman spectra of nPSi-(CHI-Ag/CMC) composite layers obtained by CDC and CSC techniques, respectively, in different deposition cycles.

Figure 8c shows that the spectra of the nPSi-(CHI-Ag/CMC) composites obtained by CDC do not show significant changes in their spectra as the number of cycles increases. The main signals observed are at: 2925 cm

-1 related to the stretching vibrations of the ν(C-H). This vibration is found in both polysaccharides (CMC and CHI) [

35,

36]; the band at 1644 cm

-1 is attributed to the absorption of the carbonyl (C=O) stretching of amide I in CHI [

37]; at 1547 cm

-1 bending vibrations δ(NH

2) or at antisymmetric stretching of carboxylate group (COO

-) and bands around 1378 cm

-1 due to stretching vibration ν(N-H) of the amide.

Figure 8d keeps the characteristic peak of the two polysaccharides at 2922 cm

-1, 1640 cm

-1, 1570 cm

-1 and 1396 cm

-1 are attributed to ν(C-H), ν(C=O), δ(NH

2) and ν(N-H), respectively. The spectra decrease in intensity as the number of cycles increases, this would be attributed to the loss of the surface enhanced Raman scattering effect (SERS), which improves the Raman scattering of a molecule when there is a metallic nanoparticle nearby [

34]. In this case the SERS effect is produced by the silver nanoparticles [

9], this effect is gradually lost, which decreases the intensity of the polymer peaks. This would be due to a lower amount of AgNPs on the surface of the composites obtained by CSC.

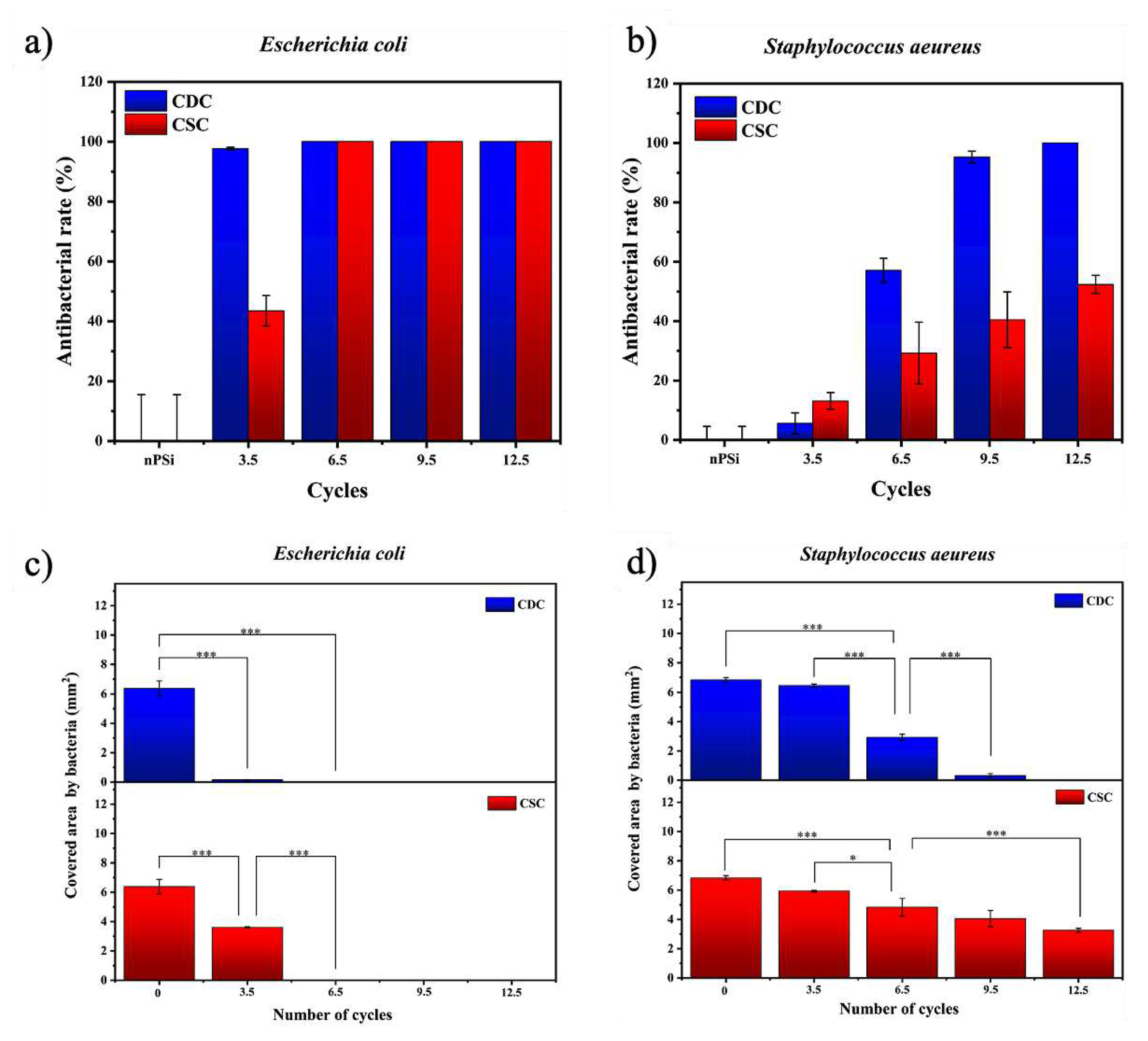

The nPSi-(CHI-Ag/CMC) composite layers studied in this work presented high antibacterial rate. Tests against

E. coli and

S. aeureus are shown in

Figure 9a and

Figure 9b, respectively. Particularly, both types of samples presented high antibacterial activity against

E. coli bacteria strain. CDC samples did not allow bacterial proliferation from 3.5 cycles, while CSC samples needed 6.5 cycles to completely the inhibition of the bacteria growth on the surface. On the other hand, CDC samples showed a high antebacterial activity against

S. aeureus just after 9.5 cycles, whereas CSC samples merely got 50% of antibacterial rate after 12.5 cycles.

To get deeper statistic information about the antibacterial activity,

Figure 9c,d present the area covered by bacteria for each sample. The area covered by

E. coli (

Figure 9c) showed a significant difference with respect to the nPSi subtrate from the sample formed after 3.5 cycles. This sustains for both CDC and CSC, exhibiting total absence of bacteria after 6.5 cycles on each single sample. On the other hand, the area covered by

S. aeureus Figure 9d) showed only a mild difference after 3.5 cycles with respect to the control. Although the antibacterial activity increases after 6.5 cycles for both CDC and CSC, the area was totally uncovered of bacteria only for the CDC sample after 12.5 cycles.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the nPSi-(CHI-Ag/CMC) composite layers: a) synthesis of nPSi substrate by electrochemical etching and stabilization by chemical oxidation, b) CHI-Ag and CMC deposition onto nPSi by cyclic dip-coating (CDC), and c) CHI-Ag and CMC deposition onto nPSi by cyclic spin-coating (CSC). In both cases, after the required cycles deposition performed, samples were immersed into an ascorbic acid solution (ASC) for Ag reduction.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the nPSi-(CHI-Ag/CMC) composite layers: a) synthesis of nPSi substrate by electrochemical etching and stabilization by chemical oxidation, b) CHI-Ag and CMC deposition onto nPSi by cyclic dip-coating (CDC), and c) CHI-Ag and CMC deposition onto nPSi by cyclic spin-coating (CSC). In both cases, after the required cycles deposition performed, samples were immersed into an ascorbic acid solution (ASC) for Ag reduction.

Figure 2.

FESEM images of a nPSi layer used in this study: a) surface and b) histograms of particle size distribution, c) and d) cross-sectional view.

Figure 2.

FESEM images of a nPSi layer used in this study: a) surface and b) histograms of particle size distribution, c) and d) cross-sectional view.

Figure 3.

Reflectance spectra of nPSi-(CHI-Ag/CMC) composite layers fabricated by: a) CDC and b) CSC. FTIR-ATR spectra of nPSi-(CHI-Ag/CMC) composite layer fabricated by c) CDC and d) CSC.

Figure 3.

Reflectance spectra of nPSi-(CHI-Ag/CMC) composite layers fabricated by: a) CDC and b) CSC. FTIR-ATR spectra of nPSi-(CHI-Ag/CMC) composite layer fabricated by c) CDC and d) CSC.

Figure 4.

XPS survey spectra of nPSi-(CHI-Ag/CMC) composite layers fabricated by: a) CDC and b) CSC. c) XPS spectra of Si 2p bands of nPSi and after ASC step for CSC and CDC method. d) XPS spectra of Ag 3d bands of CSC and CDC layer after ASC step.

Figure 4.

XPS survey spectra of nPSi-(CHI-Ag/CMC) composite layers fabricated by: a) CDC and b) CSC. c) XPS spectra of Si 2p bands of nPSi and after ASC step for CSC and CDC method. d) XPS spectra of Ag 3d bands of CSC and CDC layer after ASC step.

Figure 5.

Cross-sectional FESEM images of a typical nPSi-(CHI-Ag/CMC) composite layer after deposition using CDC: a) 3.5 cycles, b) 6.5 cycles, c) 9.5 cycles, d) 12.5 cycles; and CSC: e) 3.5 cycles, f) 6.5 cycles, g) 9.5 cycles, h) 12.5 cycles.

Figure 5.

Cross-sectional FESEM images of a typical nPSi-(CHI-Ag/CMC) composite layer after deposition using CDC: a) 3.5 cycles, b) 6.5 cycles, c) 9.5 cycles, d) 12.5 cycles; and CSC: e) 3.5 cycles, f) 6.5 cycles, g) 9.5 cycles, h) 12.5 cycles.

Figure 6.

Ag fluorescence signal in nPSi-(CHI-Ag/CMC) composite layers after 3.5, 6.5, 9.5, and 12.5 CHI-Ag and CMC deposition cycles using CDC and CSC techniques.

Figure 6.

Ag fluorescence signal in nPSi-(CHI-Ag/CMC) composite layers after 3.5, 6.5, 9.5, and 12.5 CHI-Ag and CMC deposition cycles using CDC and CSC techniques.

Figure 7.

RBS spectrum and in-depth concentration profile of Ag obtained by simulation of typical nPSi-(CHI-Ag/CMC) composite multilayers by: a) and c) CDC, and b) and d) CSC.

Figure 7.

RBS spectrum and in-depth concentration profile of Ag obtained by simulation of typical nPSi-(CHI-Ag/CMC) composite multilayers by: a) and c) CDC, and b) and d) CSC.

Figure 8.

XRD pattern of nPSi-(CHI-Ag/CMC) composite layers after 3.5, 6.5, 9.5, and 12.5 CHI-Ag and CMC deposition cycles using a) CDC and b) CSC. Raman spectra for the nPSi-(CHI-Ag/CMC) composite layer after 3.5, 6.5, 9.5 and 12.5 CHI-Ag and CMC deposition cycles using a) CDC and b) CSC.

Figure 8.

XRD pattern of nPSi-(CHI-Ag/CMC) composite layers after 3.5, 6.5, 9.5, and 12.5 CHI-Ag and CMC deposition cycles using a) CDC and b) CSC. Raman spectra for the nPSi-(CHI-Ag/CMC) composite layer after 3.5, 6.5, 9.5 and 12.5 CHI-Ag and CMC deposition cycles using a) CDC and b) CSC.

Figure 9.

Antibacterial rate of nPSi-(CHI-Ag/CMC) composite layers after 3.5, 6.5, 9.5, and 12.5 CHI-Ag and CMC deposition cycles using CDC and CSC techniques against a) E. coli, and b) S. aeureus. nPSi layers were used as control. Covered area by c) E. coli and d) S. aeureus on nPSi-(CHI-Ag/CMC) composite layers after 0, 3.5, 6.5, 9.5, and 12.5 cycles for CDC and CSC techniques. Error bars represent mean ± SD of three measurements, and they were statistically interpreted by analysis of variance (ANOVA) multifactorial model where * and *** denote a significant difference compared to the nPSi substrate after 24 hours with p < 0.05 and p < 0.001, respectively.

Figure 9.

Antibacterial rate of nPSi-(CHI-Ag/CMC) composite layers after 3.5, 6.5, 9.5, and 12.5 CHI-Ag and CMC deposition cycles using CDC and CSC techniques against a) E. coli, and b) S. aeureus. nPSi layers were used as control. Covered area by c) E. coli and d) S. aeureus on nPSi-(CHI-Ag/CMC) composite layers after 0, 3.5, 6.5, 9.5, and 12.5 cycles for CDC and CSC techniques. Error bars represent mean ± SD of three measurements, and they were statistically interpreted by analysis of variance (ANOVA) multifactorial model where * and *** denote a significant difference compared to the nPSi substrate after 24 hours with p < 0.05 and p < 0.001, respectively.