1. Introduction

Today, bacterial infections remain a serious public health concern, a challenge further exacerbated by the emergence of multidrug-resistant bacteria (MDRBs). The principal MDRBs include both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, such as

S. aureus,

S. pneumoniae,

E. faecium, and

E. faecalis (Gram-positive) and

A. baumannii,

E. coli,

P. aeruginosa, and

K. pneumoniae (Gram-negative) [

1]. Patients infected with MDRBs face:

i) an increased risk of mortality. For instance, in 2019, approximately 1.3 million deaths globally were attributed to MDRBs, and this number could rise to 10 million by 2050 if no effective action is taken to combat these microorganisms [

1,

2] ; and

ii) prolonged illness, leading to rising medical costs [

3], due to the high expense associated with accessing next-generation antibiotics and extended hospitalization periods. In this regard, burden estimates from World Organization for Animal Health and World Bank Group indicate that MDRBs cost health systems approximately 66 billion dollars per year, with projections suggesting that these costs could continue to rise over the next 25 years [

2,

3]. Therefore, it is of paramount importance to seek alternative approaches to combat these bacteria. This effort includes the discovery of new antimicrobial drugs, either synthesized or isolated from natural sources, as well as the development of novel strategies for bacterial clearance, including the design and fabrication of functional nanoparticles (FNPs). From a broader perspective, the antimicrobial effect of the FNPs can be an intrinsic property, depending on their chemical composition and their ability to respond to external physical stimuli. Furthermore, the antimicrobial activity of previously ineffective or “obsolete” drugs can be enhanced by loading them into FNPs, enabling targeted delivery to bacteria.

In this regard, plasmonic nanoparticles have emerged as promising candidates for antimicrobial applications, with gold nanoparticles (GNPs) standing out among them due to their optical properties, stability, and biocompatibility [

4,

5]. Their unique optical property is characterized by a strong absorption band, known as the surface plasmon resonance (SPR), which arises from the collective oscillation of conduction band electrons at the surface of GNPs when they resonate with incident electromagnetic radiation of a specific energy. There are two remarkable characteristics of GNPs,

i) the SPR of GNPs can be tuned across a wide wavelength range, from visible to NIR region, by simply varying their size and shape [

6]. For instance, spherical gold nanoparticles (SGNP) exhibit SPR at approximately 520 nm, with the absorption peak broadening and red shifting as particle size increases. In contrast, anisotropic gold nanostructures -such as nanorods, cubes, and core-shell architectures- display broader SPR bands in the NIR region, which can be further tunable by adjusting their aspect ratio; ii) all these GNPs can efficiently convert the absorbed light into heat through nonradiative electron relaxation, dissipating the thermal energy into the surrounding medium [

7]. This phenomenon, known as the photothermal effect (PT), is a critical property for alternative therapeutic applications, such as photothermal therapy (PTT), which has been explored for inactivation of viruses, fungi, and tumor cells and even MRDBs [

6,

8,

9].

In the present report, GNSs grown on a dielectric template based on chitosan nanoparticles are proposed for the clearance of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria via photothermal effect. Several studies have reported the synthesis of GNSs on dielectric templates, such as AuS

2 SiO

2, PLGA and polystyrene NPs [

9,

10,

11]. However, no reports were found, at least within the reviewed literature, where chitosan nanoparticles have been used as dielectric template for the growth of a gold shell.

2. Results

2.1. Chitosan Modification and Synthesis of Chitosan Nanoparticles (TCNP)

2.1.1. Chitosan Modification

The chemical modification of chitosan is typically performed to alter its physicochemical properties in aqueous media, including its hydrophilic/hydrophobic balance and reactivity in water. Given the strong affinity of sulfur for gold [

12,

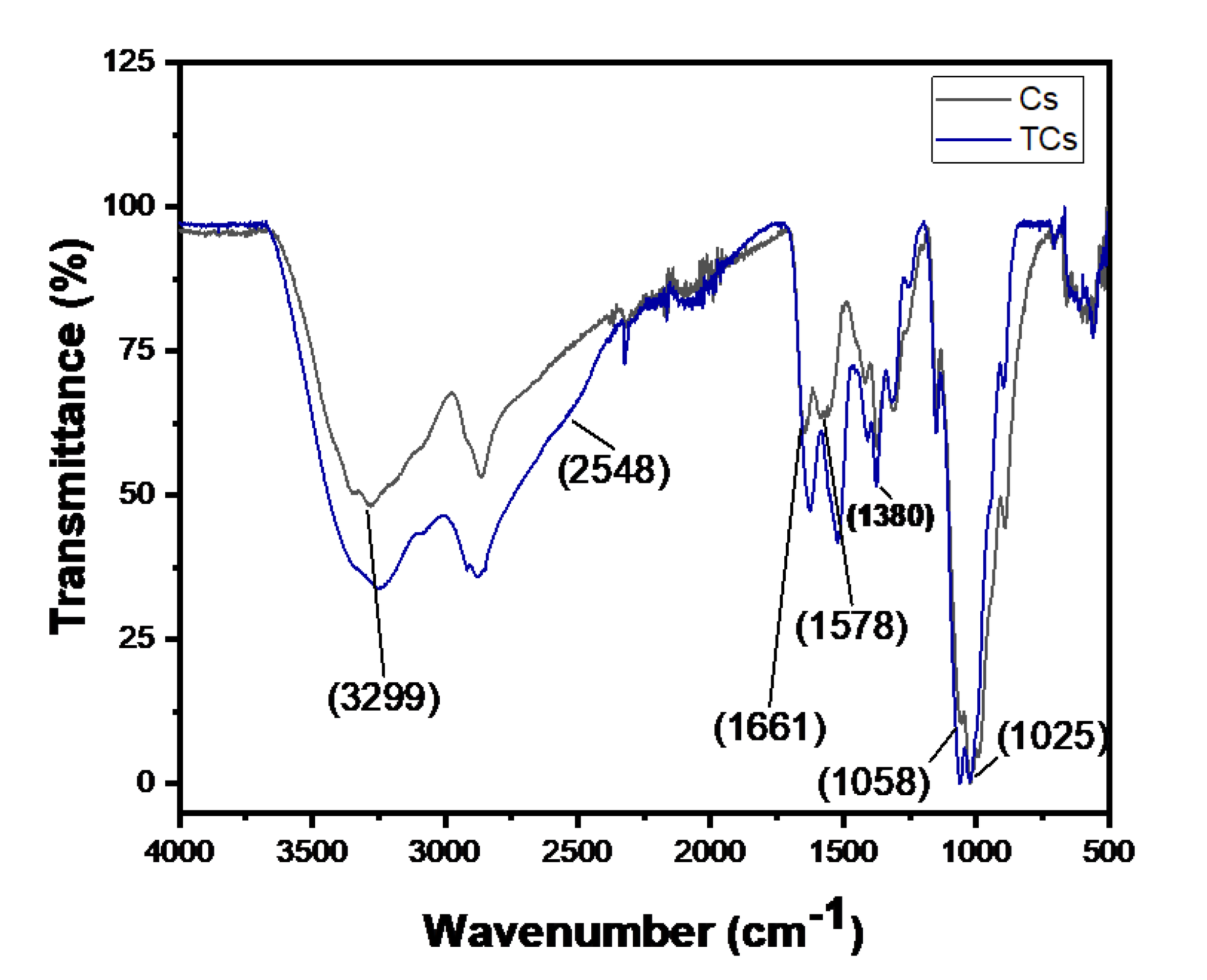

13], 3-mercaptopropionic acid (3-MPA) was conjugated to the amine groups of chitosan to facilitate the growth of a gold shell, achieved via a gold seed-mediated growth process, onto the surface of TCNP. The chemical attachment of 3-MPA to chitosan was confirmed by FTIR in ATR mode. The FTIR spectra of native CS and TCS are shown in

Figure 1. The black line corresponds to the FTIR spectrum of native CS, which shows characteristic stretching bands at 3299 cm

-1, attributed to -OH and -NH

2 groups. The asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations of C-O-C group appear at 1058 and 1025 cm

-1, while the C-N stretching (amide III) is denoted by the peak at 1380 cm

-1 [

14,

15]. The successful modification of chitosan was confirmed by changes in amide I (1661 cm

-1) and amide II (1578 cm

-1) bands [

16]. The blue line of TCs shows the peaks corresponding to amide I and amide II show changes in intensity and shift to lower wavenumbers. These spectral changes indicate the successful attachment of 3-MPA to CS via amide bond formation. Additionally, the presence of the thiol (-SH) functional group was confirmed by the small shoulder observed at 2548 cm

-1 [

12], further validating the success of the amidation reaction.

2.1.1. Synthesis of TCNPs

TCNPs were synthesized using the ionic gelation method, with TPP as a crosslinking agent. Synthesis conditions, such as pH (4.5, 4.8, 5.0 and 5.2) and the TPP:CS ratio (1.2:1, 1:1, 0.8:1 and 0.6:1 w/w), were varied to optimize the formation of spherical TCNPs with sizes below 200 nm. The results are summarized in

Table 1. Based on the observed morphology and size of TCNPs, the optimal synthesis conditions were achieved at pH 4.8 with a TPP:CS ratio of 0.8:1. These conditions appear to favor TCNP formation due to several factors: (i) the amount of TPP is sufficient to facilitate ionic crosslinking with TCS, whereas both lower and higher TPP:CS ratios tend to result in the formation of larger nanoparticles; (ii) at pH 4.8, electrostatic interactions between TPP and thiolated chitosan are optimized, playing a key role in nanoparticle formation; and (iii) under these pH conditions, TCS molecules adopt a partially coiled structure, ensuring the availability of a sufficient number of amino groups, which promotes the formation of spherical TCNPs with sizes below 200 nm [

17,

18]. It is worth noting that TCNP sizes below 200 nm were also observed under other pH conditions and TPP:TCS ratios (

Table 1); however, the TCNP suspensions showed instability in the aqueous medium, along with high polydispersity index (PDI) values, indicating non-monodisperse nanoparticles size distribution [

19].

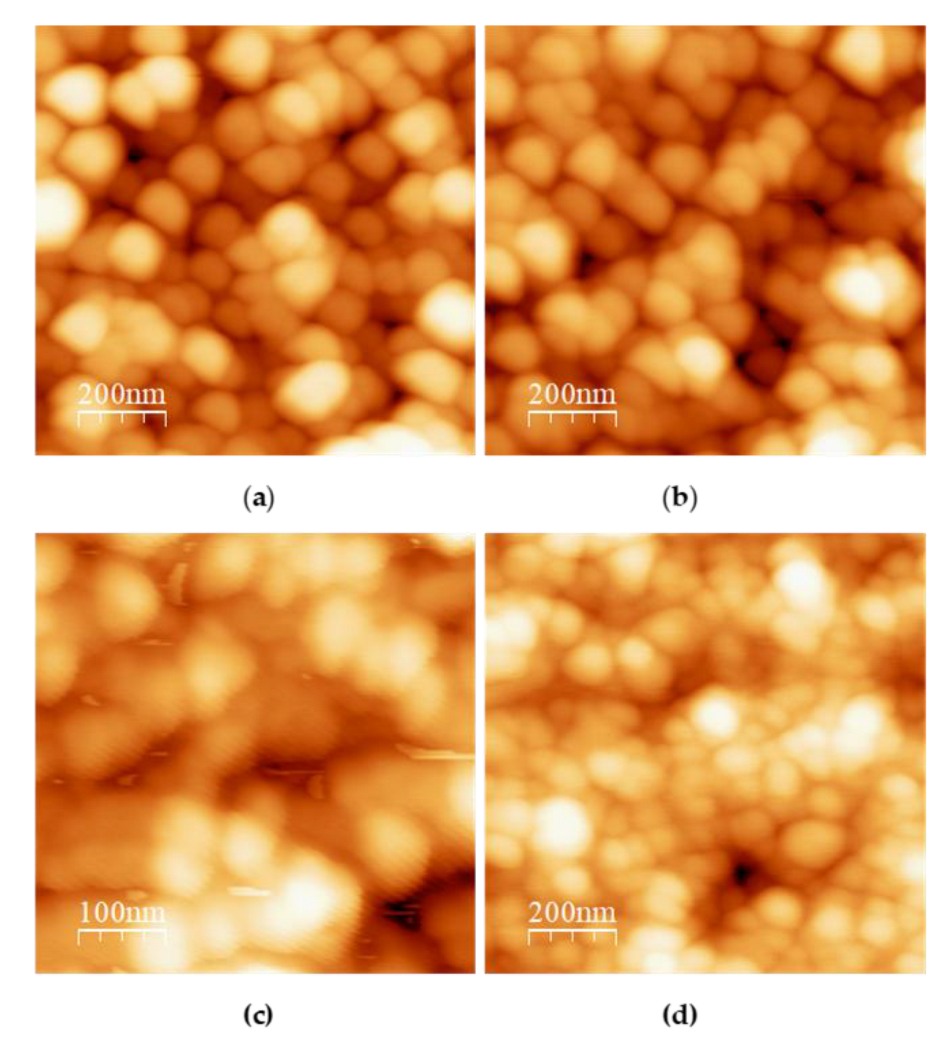

Figure 2 presents the AFM images of TCNPs synthesized at a TPP:TCS ratio of 0.8:1 under different pH conditions (4.5, 4.8, 5.0 and 5.2). It can be observed that TCNPs synthesized at pH 4.5 and 4.8 show a spherical morphology, with approximate size of 190 nm and 150 nm, respectively (

Figure 2a,b). These sizes measurements are consistent with the hydrodynamic diameters determined by DLS (215 nm and 178 nm). Furthermore, TCNPs synthesized at pH 4.8 conditions demonstrate enhanced stability, whereas those obtained pH 4.5 exhibited poor stability, consisting with previous reports [

20]. At higher pH values, the synthesized TCNPs displayed increased polydispersity and polymorphic structures. Based on these findings, TCNPs synthesized at pH 4.8 were chosen as the dielectric template for gold shell growth.

2.2. Core-Shell Chitosan-Gold Nanoparticles

Gold shells were grown onto the surface of TCNPs using a seed-mediated method, which involves the growth of shell layer from gold seed previously adsorbed onto the surface of nanoparticle. This approach is similarly to the synthesis of gold shell using silver and platinum NPs as templates [

21,

22,

23], or their deposition onto dielectric nanoparticles as silicon oxide and polymer NPs [

24,

25,

26]. For instance, when silver nanoparticles are used as growth templates, gold hollow-shell structures are spontaneously formed through a galvanic replacement process. In contrast, a dielectric core–gold shell structure is obtained when silicon oxide or polymer nanoparticles serve as the growth scaffold. This process consists of two consecutive stages: The adsorption of gold seeds onto the surface of the dielectric core, and the two-dimensional (2D) shell growth, which occurs after gold seed adsorption, thorough deposition of gold atom (typically Au

+) in the presence of a moderate reductant. The adsorption of gold seeds can be further enhanced by modifying the surface of the dielectric nanoparticles thorough chemical attachment of functional groups with strong affinity to gold, such as thiol (-SH) groups. In this regard, the chitosan structure was modified by conjugating 3-MPA motifs, resulting in TCS, which was then used to synthesize TCNPs with surface-exposed -SH groups.

Then, TCNPs were used as templates for the growth of gold shells, mediated by gold seeds. First, gold seeds were added to TCNP solution and allowed sufficient time (16 hours) to anchor onto the surface TCNPs. After this period, the gold shells growth was initiated by the sequential addition of Au

+3 and ascorbic acid (AA). The gold shell formation was monitored by UV-Vis spectroscopy, where the appeance of a broader SPR band in the wavelength range of 600-1000 nm confirmed the successful gold shell growth.

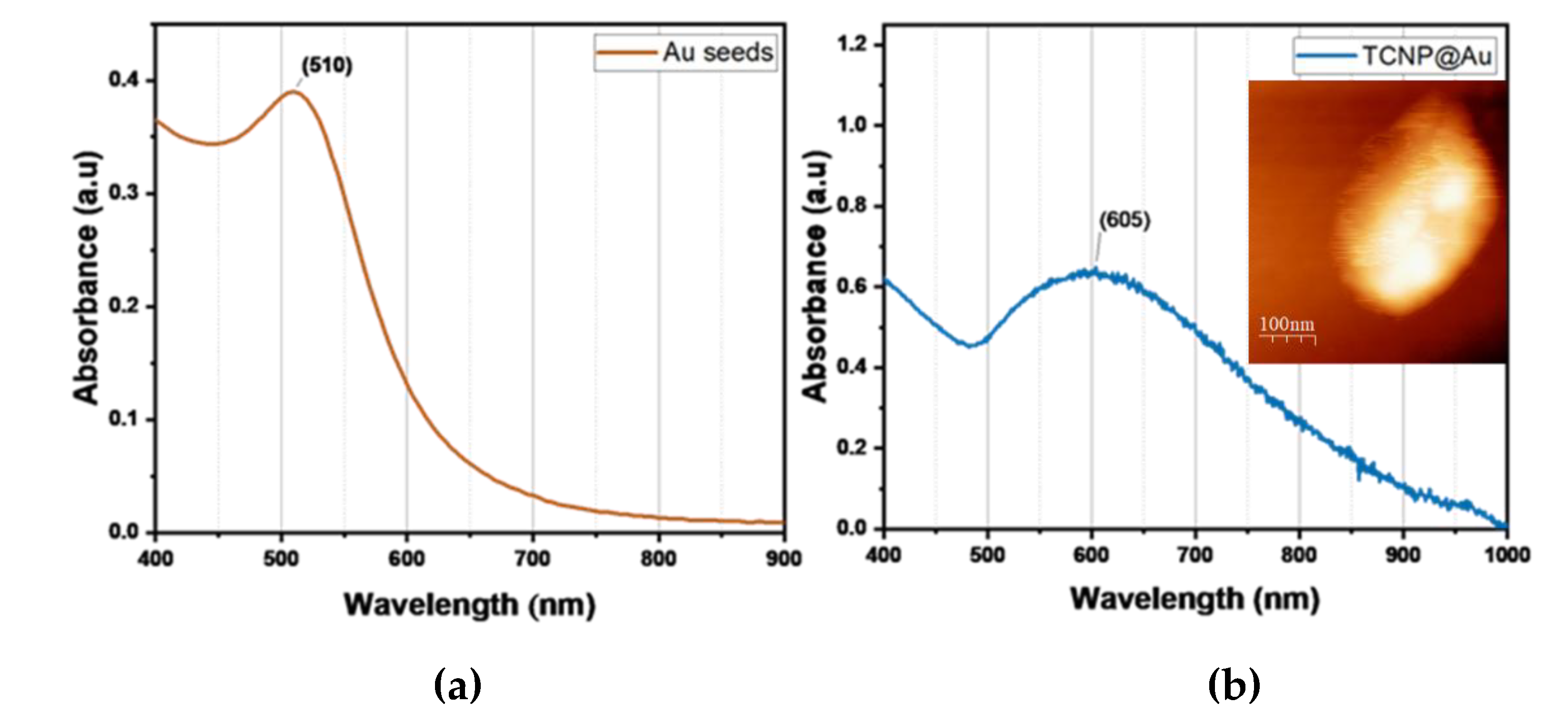

Figure 3 shows the characteristic SPR of TCNP core-gold shell nanoparticles (TCNP@Au), with the SPR absorption band appearing in the NIR region, showing a maximum wavelength of approximately 605 nm. The particle size and zeta potential of TCNP@Au were measured as 415±15 nm (PDI = 0.380) and 7±2 mV, respectively. These results are consistent with previous reports [

24,

28,

29,

30]. The morphology of TCNP@Au, recorded using AFM, showed an ovoidal shape (inset in

Figure 3b), with a size comparable to that observed by DLS.

2.2.1. Photothermal Conversion Efficiency of TCNP@Au

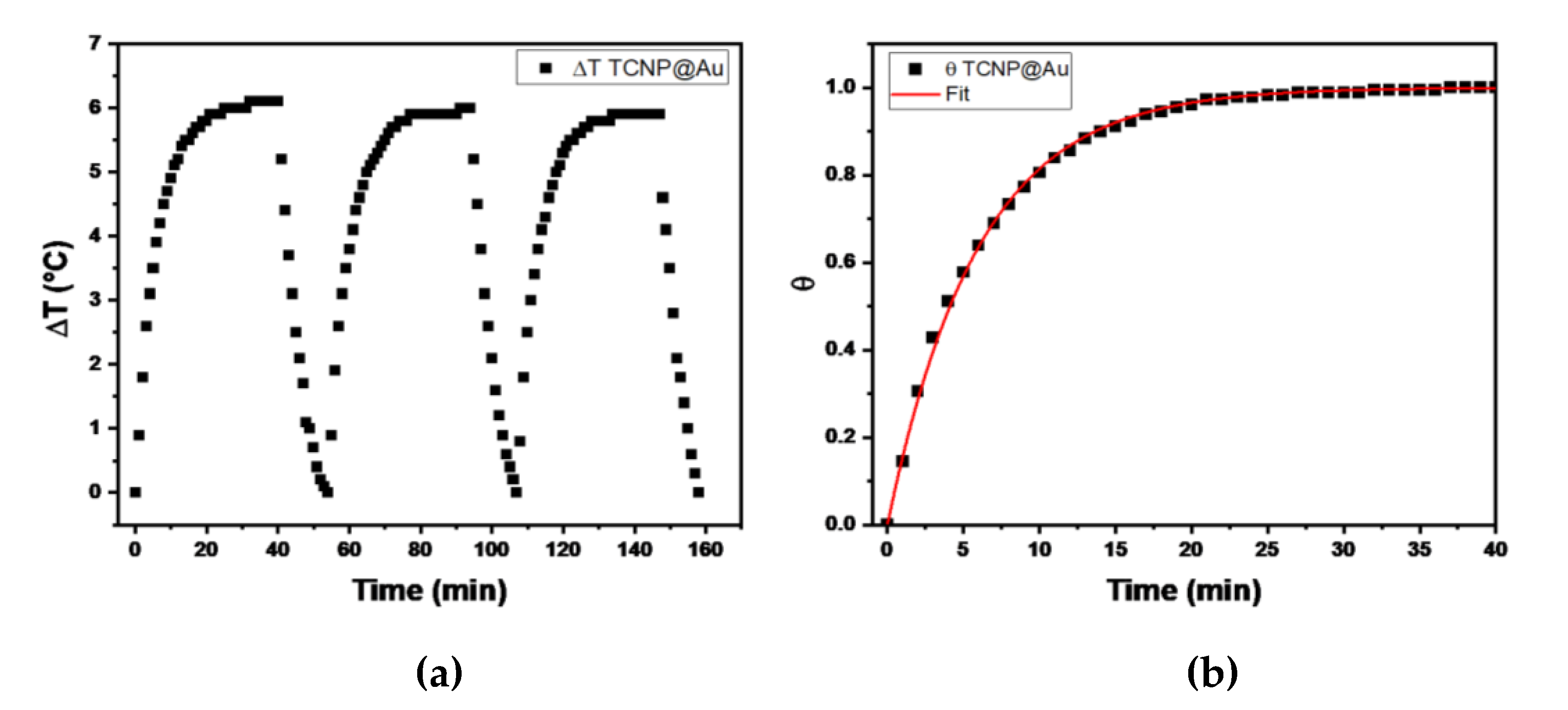

The temperature changes profiles are shown in

Figure 4. It can be observed that the maximum temperature increase (ΔT) during the three irradiation cycles was 6 C°, above room temperature, indicating the thermal stability of TCNP@Au throughout the irradiation process. Then, the photothermal conversion efficiency (η), determined by equation 1, was approximately 31%, a value comparable with previously reported results [

31,

32,

33]. These findings suggest that the photothermal properties of TCNPs@Au hold promise for biological applications.

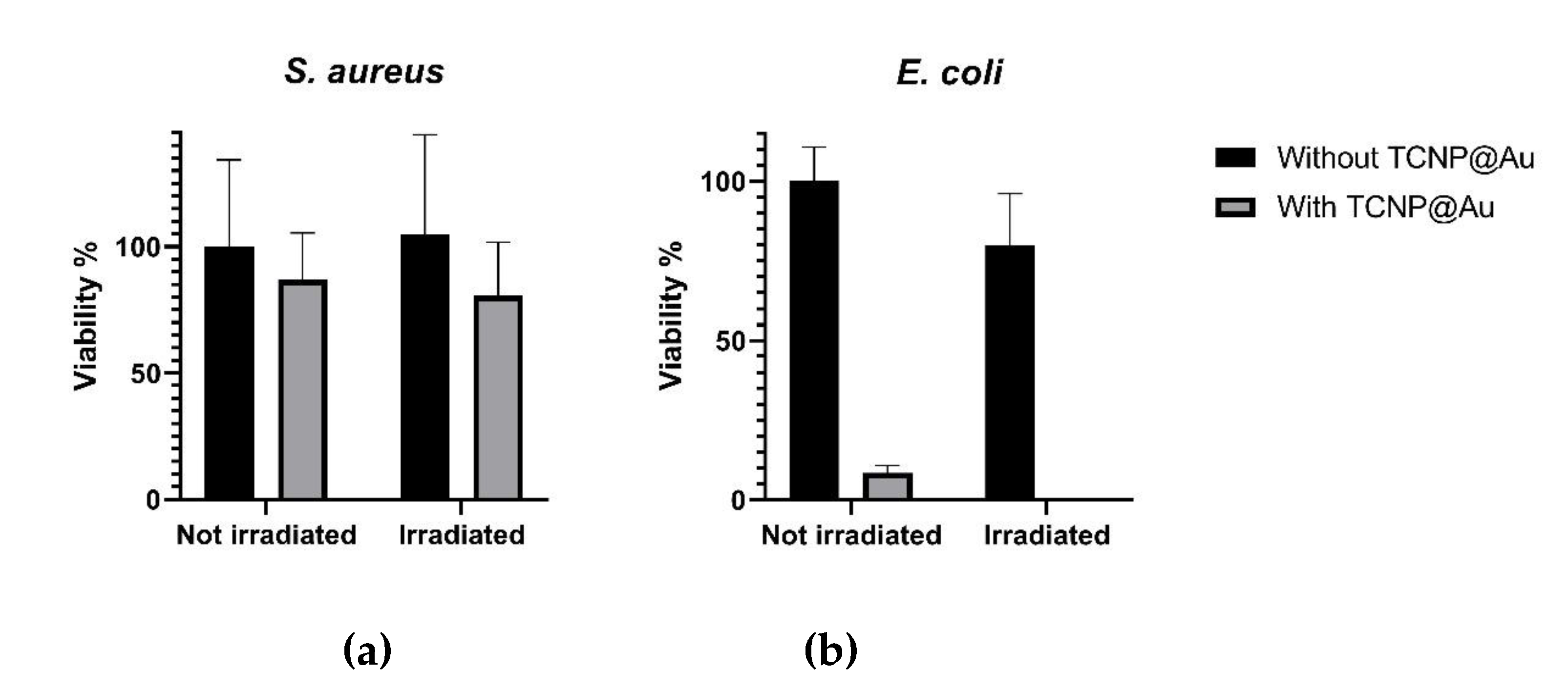

2.3. Photothermal Effect of TCNP@Au on the Viability of Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Bacteria

The potential of TCNP@Au as a photothermal agent for bacterial clearance was evaluated against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, using

Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 25923) and

Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922). The photothermal effect on bacterial viability was assessed after 15 minutes of laser irradiation (1 W, 808 nm) in the presence of TCNP@Au. Bacterial viability following irradiation was compared to controls samples incubated under the same conditions but without laser irradiation, as shown in

Figure 5.

Figure 5a shows the effect of TCNP@Au on the viability of

S. aureus under both non-laser irradiated and laser-irradiated conditions. As observed, the presence of TCNP@Au alone slightly affected

S. aureus viability reducing it to 86.8 %. Upon laser irradiation, viability further decreased to 76.8 %, although this reduction was not statistically significant (

p >0.05). The resilience of

S. aureus to photothermal treatment can be attributed to its intrinsic tolerance to adverse conditions, including high temperatures, high salt concentrations, and osmotic pressure. Notably,

S. aureus can grow within a temperature range of 7–48 °C, with an optimum at 37 °C. Moreover, it has been shown to withstand heat treatments exceeding 60 °C for up to 30 minutes [

34]. The survival of

S. aureus post-irradiation can be due to its thick peptidoglycan layer, which forms a robust structural barrier around the lipid membrane. This peptidoglycan layer serves as a protective shield against the photothermal action of TCNP@Au. These findings suggest that further optimization of photothermal treatment is necessary for effective

S. aureus eradication. Potential strategies include increasing laser irradiation time or incorporating antibiotic compounds into the TCNP core to create a synergistic effect with photothermal therapy. On the other hand,

Figure 5b shows that

E. coli viability was significantly affected by the presence of not irradiated TCNP@Au (viability: 8.5 %). Upon laser irradiation, the bacterial population was nearly eradicated, with only 0.1 % viability remaining. This heightened susceptibility of

E. coli to photothermal treatment can be attributed to the structural differences between Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. At difference to

S. aureus,

E. coli possess a lipid bilayer with a thin peptidoglycan layer, making them more vulnerable to thermal damage induced by TCNP@Au [

35,

36,

37].

3. Materials and Methods

The Chitosan (CS, low molecular weight, average 120 kDa), sodium triphosphate pentabasic (TPP), 3-mercaptopropionic acid (3-MPA), acetic acid, gold (III) chloride trihydrate, L-ascorbic acid, sodium borohydride, all where from Sigma Aldrich. Sodium citrate dihydrate granular from J.T. Barker. Bacteria stains (Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus) were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC).

3.1. Thiolated Chitosan (TCs)

Thiolated chitosan was synthesized following the method described by Ko et. al., with slight modifications, involving a two-step reaction. First, solutions for EDAC, 3-MPA and NHS were prepared in DMF (2.0 mmol). 2.0 mL of EDAC was added to 2.0 mL of 3-MPA solution and the mixture was stirred magnetically for 1 hour. After this period, 2.0 mL of NHS was gradually added to the EDAC-3-MPA mixture and stirred at room temperature overnight (solution-1). In the second step, a chitosan (CS) solution (0.02% w/v) was prepared using HCl solution (0.1 M). The pH of the CS solution was then adjusted to 4.0 using NaOH solution (1 M), and solution-1 was immediately added dropwise to the CS solution under magnetic stirring. The mixture was continuously stirred for 12 hours at room temperature. The thiolated chitosan (TCS) was purified through an exhaustive dialysis process using deionized water. Then, the purified product was lyophilized and characterized by spectroscopic techniques.

3.1.1. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy-Attenuated Total Reflectance (FTIR-ATR)

FTIR-ATR spectroscopy was used to confirm the successful modification of chitosan with 3-MPA. The FTIR-ATR spectra were recorded using PerkinElmer spectrophotometer (Connecticut, USA). The spectral range was scanned from 4000 to 400 cm-1 with a resolution of 2 cm-1.

3.2. Synthesis of Thiolated Chitosan Nanoparticles (TCsNp)

Thiolated chitosan nanoparticles (TCSNPs) were synthesized using the well-established ionic gelation method, with TPP as a crosslinker. To obtain spherical TCSNPs with a size below 200 nm, different TCS solutions were adjusted to various pHs (4.5, 4.8, 5.0 and 5.2) and tested different TPP:C ratio (1.2:1, 1:1, 0.8:1 and 0.6:1 w/w). Under these conditions, 10 mL of TCS solution (0.5mg/mL, in 50 mM acetic acid) was heated in a water bath at 60°C for 10 minutes under constant stirring. The solution was then rapidly cooled in an ice bath (4°C), and 2 mL TPP solution (2mg/mL) was immediately added to the CS solution, followed by stirring for an additional 15 minutes. The resulting colloidal suspension was centrifuged at 9000 rpm for 30 min at 15°C. After the centrifugation, the supernatant was discarded, and the sediment was resuspended in 5 mL in Milli-Q water.

3.3. Synthesis of Gold-Shell on TCSNPs

The gold-shell on the surface of TCSNPs (Np TCs@Au) was synthesized using an in-situ seed-growth mediated method, consisting into consecutive steps. First, the gold seeds were synthesized following the method described by Topete et al. lightly modified. Briefly, an HAuCl4 (14.7 mM) and sodium citrate solution (1 mM) were prepared. Then 0.102 mL of gold solution was mixed with 2.25 mL of citrate solution and 2.6 ml of pure water was added to get a total volume solution of 5 mL, stirring constantly at room temperature. The gold seed was attained once of the addition of 50 μL of cold NaBH4 solution (0.1M). The seeds were diluted 1:4 in sodium citrate before the second step.

20 μL of the diluted gold seed was added to the TCSNP solution, and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 16-hrs. After this period, 50 μL of the Au3+ (1.47 mM) added to TCSNP suspension, followed immediately by the addition of 20 μL of ascorbic acid (10 mM), maintaining continuous stirring. After 90 minutes of reaction, an additional 50 μL of Au3+ and 20 μL of ascorbic acid were added. This procedure was repeated four times. Then, the colloidal suspension gradually changed from an opalescent to blue-green color. Finally, the mixture was purified by dialysis for four days in deionized water.

3.4. Characterization

3.4.1. Nanoparticles Size Analysis by Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS)

The hydrodynamic size of nanoparticles was determined using a Zetasizers Nano ZS (Malvern Instruments, UK). The instrument is equipped with a red He-Ne laser (4mW) at a wavelength of 633 nm. Samples were placed in the measurement cell, and measurements were performed in triplicate at temperature of 25 °C.

3.4.2. Atomic Force Microscopy

The morphology of TCSNPs and TCNP@Aus was analyzed by AFM (JSPM-4210, JEOL, Japan). Samples were prepared as follow: an aliquot of the nanoparticle suspension was placed onto the surface of freshly cleaved mica. After a minute, the excess water was adsorbed with paper and then left until the sample dries.

3.4.3. UV-Vis Spectroscopy

The gold-shell growth was followed using UV-Vis spectroscopy (Lambda 365 Perkin Elmer). The spectra were recorded on the wavelength range of 400-1000 nm.

3.5. Photothermal Conversion of TCNP@Au

The photothermal conversion of TCNP@Au was evaluated under laser irradiation (1 W, λ = 808 nm). Samples were subjected to on/off cycles irradiation for 40 minutes and the temperature increase was recorded using a thermocouple every 60 seconds. Each experiment was performed in triplicate for reproducibility.

To determine the photothermal conversion efficiency (η), the temperature data were plotted as a function of time to the theoretical Roper equation [

38]:

(1)

were

h is the heat transfer coefficient,

A is the quartz cell area,

Aλ is the absorbance value of the TCNP@Au suspension at 808 nm,

Q0 is the system represents the system heat contribution (considering, water, TCNP@Au, and quartz), and

I is the laser power. The value of

h is calculated using the following equation [

9]:

, (2)

where is the total heat capacity of the system (Q0), A is the quartz cell area, and τs is the cooling rate constant. The parameter τs is determined from the increase temperature during the laser turn-on period. The temperature data are fitted to the following equation:

(3)

where

, a dimensional driving force temperature,

T0 and

Tmax, represent the room temperature and the maximum temperature, respectively.

Tt is the temperature at time t [

38].

4.5. Photothermal Effect on the Bacterial Growth

The photothermal effect on bacterial growth inhibition was evaluated using Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922) and Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC25923) as Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacterial models, respectively. The antibacterial activity of TCNP@Au was assessed using the macrodilution method, following the guidelines of Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Briefly, a bacterial suspension at a concentration of 500,000 CFU/mL was added to 5 mL of suspension of the TCNP@Au in a test tube. The upper part of the test tube was then irradiated for 15 minutes with a CW laser (808 nm, 1 W). After irradiation, serial dilutions (1:10, 1:100, 1:1000) were prepared, and 100 μL of each diluted samples were plated onto agar petri dishes. Bacterial viability was determined by counting the CFUs after 18 h of incubation at 37°C.

5. Conclusions

In summary, TCNPs with sizes under 200 nm were successfully prepared using a reproducible and straightforward approach, in which the solution pH and TPP:TCS ratio were systematically varied. The optimal experimental formulation was obtained at pH 4.8 with a TPP:TCS ratio of 0.8:1.0. Importantly, the resulting TCNPs can serve as effective templates for anchoring gold seeds due to the presence of surface-exposed -SH groups, which acted as nucleation sites for the growth the gold nanoshells. TCNP@Au showed excellent values η, reaching values comparable to previously reported one making them promising photothermal agent for the eradication of Gram-negative bacteria. E. coli, a Gram-negative bacterium, was strongly affected by the presence of TCNP@Au, with bacterial viability decreasing to 8.5%. Furthermore, after laser irradiation, E. coli was effectively eradicated from the culture medium. Interestingly, S. aureus, a Gram-positive bacterium, exhibited resistance to photothermal treatment, highlighting its ability to withstand harsh environmental conditions. This finding underscores the need to reassess strategies for combating S. aureus to achieve effective bacterial elimination. Despite this limitation, TCNP@Au demonstrate promising potential as photothermal agents and for the design of novel devices with applications in antibacterial biomaterials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Josue Juarez and Patricia Dolores Martinez Flores.; methodology, Patricia Dolores Martinez Flores., Manuel Gerardo Ballesteros Monrreal.; Pablo Mendez-Pfeiffer and Marisol Gastelum Cabrera; validation, Patricia Dolores Martinez Flores., Marco Antonio Lopez Mata., Gerardo García González., Gerardo Erbey Rodea Montealegre. and Manuel Gerardo Ballesteros Monrreal.; formal analysis, Josue Juarez; investigation, Josue Juarez; resources, Josue Juarez; data curation, Josue Juarez; writing—original draft preparation, Josue Juarez. Patricia Dolores Martinez Flores; writing—review and editing Josue Juarez. Marco Antonio Lopez Mata., Gerardo García González. and Gerardo Erbey Rodea Montealegre.; visualization, Josue Juarez; supervision, Josue Juarez. Marco Antonio López Mata., Gerardo García González. and Gerardo Erbey Rodea Montealegre.; project administration, Josue Juarez; funding acquisition, Josue Juarez. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

Project CF-2023-G-41 and CV SECIHTI 1009922.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the finding of this study are included in the present manuscript. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Acknowledgments

To Universidad de Sonora for infrastructure support and to SECIHTI for economic support under the project CF-2023-G-41.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Cs |

Chitosan |

| TPP |

Sodium Triphosphate Pentabasic |

| 3-MPA |

3-mercaptopropionic acid |

| TCs |

Thiolated Chitosan |

| FTIR-ATR |

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy-Attenuated Total Reflectance |

| TCsNPs |

Thiolated Chitosan Nanoparticles |

| TCs@AuNp |

Core-Shell Chitosan-Gold Nanoparticles |

| AFM |

Atomic Force Microscopy |

| AuSD |

Gold Seeds |

| AA |

Ascorbic Acid |

| LSPR |

Localized Surface Plasmonic Resonance |

| PDI |

Polydispersity Index |

References

- A. Karnwal, A. Y. A. Karnwal, A. Y. Jassim, A. A. Mohammed, A. R. Mohammad Said Al-Tawaha, M. Selvaraj, and T. Malik, “Addressing the global challenge of bacterial drug resistance : insights, strategies, and future directions,” no. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Ajulo and B. Awosile, “Global antimicrobial resistance and use surveillance system ( GLASS 2022 ): Investigating the relationship between antimicrobial resistance and antimicrobial consumption data across the participating countries,” no. Glass 2022, pp. 2024; 21. [CrossRef]

- A. McDonnell et al. E: “Forecasting the Fallout from AMR, 2024. [CrossRef]

- X. Hu, Y. X. Hu, Y. Zhang, T. Ding, J. Liu, and H. Zhao, “Multifunctional Gold Nanoparticles: A Novel Nanomaterial for Various Medical Applications and Biological Activities,” Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol., vol. 8, no. August, pp. 2020; 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Hassan, P. H. Hassan, P. Sharma, M. R. Hasan, S. Singh, D. Thakur, and J. Narang, “Gold nanomaterials – The golden approach from synthesis to applications,” Mater. Sci. Energy Technol., vol. 5, pp. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. P. P. Kumar and D. K. Lim, “Photothermal Effect of Gold Nanoparticles as a Nanomedicine for Diagnosis and Therapeutics,” Pharmaceutics, vol. 15, no. 2023; 9. [CrossRef]

- J. Milan, K. J. Milan, K. Niemczyk, and M. Kus-Liśkiewicz, “Treasure on the Earth—Gold Nanoparticles and Their Biomedical Applications,” Materials (Basel)., vol. 15, no. 2022; 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O. Tatsuno, Y. O. Tatsuno, Y. Niimi, M. Tomita, H. Terashima, T. Hasegawa, and T. Matsumoto, “Mechanism of transient photothermal inactivation of bacteria using a wavelength-tunable nanosecond pulsed laser,” Sci. Rep., vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 2021; 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. R. Cole, N. A. Mirin, M. W. Knight, G. P. Goodrich, and N. J. Halas, “Photothermal efficiencies of nanoshells and nanorods for clinical therapeutic applications,” J. Phys. Chem. C, vol. 113, no. 28, pp. 12090–1 2094, 2009. [CrossRef]

- A. Topete et al., “Simple control of surface topography of gold nanoshells by a surfactant-less seeded-growth method,” ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, vol. 6, no. 14, pp. 11142–1 1157, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liu et al., “Photothermal conversion of gold nanoparticles for uniform pulsed laser warming of vitrified biomaterials,” Nanoscale, vol. 12, no. 23, pp. 12346–1 2356, 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. De Torre-miranda, L. N. De Torre-miranda, L. Reilly, P. Eloy, C. Poleunis, and S. Hermans, “Thiol functionalized activated carbon for gold thiosulfate recovery, an analysis of the interactions between gold and sulfur functions,” Carbon N. Y., vol. 204, no. 22, pp. 20 December 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. S. Inkpen, Z. M. S. Inkpen, Z. –F Liu, H. Li, L. M. Campos, J. B. Neaton, and L. Venkataraman, “Non-chemisorbed gold–sulfur binding prevails in self-assembled monolayers,” Nat. Chem., vol. 11, no. 4, pp. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. A. M. Hussein, M. Grinholc, A. S. A. Dena, I. M. El-Sherbiny, and M. Megahed, “Boosting the antibacterial activity of chitosan–gold nanoparticles against antibiotic–resistant bacteria by Punicagranatum L. extract,” Carbohydr. Polym., vol. 256, no. December 2020, p. 11 7498, 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. Pan, J. Qian, C. Zhao, H. Yang, X. Zhao, and H. Guo, “Study on the relationship between crosslinking degree and properties of TPP crosslinked chitosan nanoparticles,” Carbohydr. Polym., vol. 241, no. April, p. 11 6349, 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. Hahn, E. Tafi, A. Paul, R. Salvia, P. Falabella, and S. Zibek, “Current state of chitin purification and chitosan production from insects,” J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol., vol. 95, no. 11, pp. 2775– 2795, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. A. Algharib et al., “Preparation of chitosan nanoparticles by ionotropic gelation technique: Effects of formulation parameters and in vitro characterization,” J. Mol. Struct., vol. 1252, p. 13 2129, 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. J. Sullivan, M. D. J. Sullivan, M. Cruz-Romero, T. Collins, E. Cummins, J. P. Kerry, and M. A. Morris, “Synthesis of monodisperse chitosan nanoparticles,” Food Hydrocoll., vol. 83, pp. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Mudalige, H. T. Mudalige, H. Qu, D. Van Haute, S. M. Ansar, A. Paredes, and T. Ingle, Characterization of Nanomaterials : Tools and Challenges. Elsevier Inc., 2019.

- P. Yadav and A. B. Yadav, “Preparation and characterization of BSA as a model protein loaded chitosan nanoparticles for the development of protein-/peptide-based drug delivery system,” Futur. J. Pharm. Sci., vol. 7, no. 2021; 1. [CrossRef]

- T. T. Ha Pham et al., “The structural transition of bimetallic Ag-Au from core/shell to alloy and SERS application,” RSC Adv., vol. 10, no. 41, pp. 24577–2 4594, 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. S. Dikkumbura et al., “Growth Dynamics of Colloidal Silver-Gold Core-Shell Nanoparticles Studied by in Situ Second Harmonic Generation and Extinction Spectroscopy,” J. Phys. Chem. C, vol. 125, no. 46, pp. 25615–2 5623, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Alwhibi, K. M. O. Ortashi, A. A. Hendi, M. A. Awad, D. A. Soliman, and M. El-Zaidy, “Green synthesis, characterization and biomedical potential of Ag@Au core–shell noble metal nanoparticles,” J. King Saud Univ. - Sci., vol. 34, no. 4, p. 10 2000, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Gordel-Wójcik, M. M. Gordel-Wójcik, M. Pietrzak, R. Kołkowski, and E. Zych, “Silica-coated gold nanoshells: Surface chemistry, optical properties and stability,” J. Lumin., vol. 270, no. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Lee, S. S. Lee, S. Lee, S. Hwang, and S.-J. Park, “Gold nanoshells with varying morphologies through templated surfactant-assisted.pdf. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. A. Dheyab, A. A. M. A. Dheyab, A. A. Aziz, M. S. Jameel, O. A. Noqta, and B. Mehrdel, “Synthesis and coating methods of biocompatible iron oxide/gold nanoparticle and nanocomposite for biomedical applications,” Chinese J. Phys., vol. 64, no. 19, pp. 20 November 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O. Sci. Instrum. 2007.

- H. Liu et al., “Photothermal therapy of Lewis lung carcinoma in mice using gold nanoshells on carboxylated polystyrene spheres,” Nanotechnology, vol. 19, no. 2008; 45. [CrossRef]

- A. Sood, V. A. Sood, V. Arora, J. Shah, R. K. Kotnala, and T. K. Jain, “Ascorbic acid-mediated synthesis and characterisation of iron oxide/gold core–shell nanoparticles.,” J. Exp. Nanosci., vol. 11, no. 5, pp. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Grabowska-Jadach, D. Kalinowska, M. Drozd, and M. Pietrzak, “Synthesis, characterization and application of plasmonic hollow gold nanoshells in a photothermal therapy—New particles for theranostics,” Biomed. Pharmacother., vol. 111, no. January, pp. 1147– 1155, 2019. [CrossRef]

- V. P. Pattani and J. W. Tunnell, “Nanoparticle-mediated photothermal therapy: A comparative study of heating for different particle types,” Lasers Surg. Med., vol. 44, no. 8, pp. 2012. [CrossRef]

- O. A. Savchuk, J. J. O. A. Savchuk, J. J. Carvajal, J. Massons, M. Aguiló, and F. Díaz, “Determination of photothermal conversion efficiency of graphene and graphene oxide through an integrating sphere method,” Carbon N. Y., vol. 103, pp. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Ayala-orozco et al., “Au Nanomatryoshkas as E ffi cient Transducers for Cancer Treatment : Benchmarking against Nanoshells,” no. 6, pp. 6372–6381, 2014.

- H. Hassan, C. F. Iskandar, R. Hamzeh, N. J. Malek, A. El Khoury, and M. G. Abiad, “Heat resistance of Staphylococcus aureus, Salmonella sp., and Escherichia coli isolated from frequently consumed foods in the Lebanese market,” Int. J. Food Prop., vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 2435– 2444, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liu et al., “Multifunctional Magnetic Copper Ferrite Nanoparticles as Fenton-like Reaction and Near-Infrared Photothermal Agents for Synergetic Antibacterial Therapy,” ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, vol. 11, no. 35, pp. 31649–3 1660, 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Zhang et al., “Gold-Platinum Nanodots with High-Peroxidase-like Activity and Photothermal Conversion Efficiency for Antibacterial Therapy,” ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, vol. 13, no. 31, pp. 37535–3 7544, 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. Mao et al., “Local Photothermal/Photodynamic Synergistic Therapy by Disrupting Bacterial Membrane to Accelerate Reactive Oxygen Species Permeation and Protein Leakage,” ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, vol. 11, no. 19, pp. 17902–1 7914, 2019. [CrossRef]

- D. K. Roper, W. Ahn, and M. Hoepfner, “Microscale heat transfer transduced by surface plasmon resonant gold nanoparticles,” J. Phys. Chem. C, vol. 111, no. 9, pp. 3636– 3641, 2007. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).