1. Introduction

In recent years, the development of advanced coatings for bone implants has attracted considerable interest in the field of orthopaedic surgery and biomedical engineering [

1]. Bone implant coatings are designed to optimize the process of osseointegration; i.e., forming a stable integration of implants with the surrounding bone tissue. This process involves a series of biological events that allow the implant to merge organically with the surrounding bone, creating a solid and durable connection. Since the interaction at the interface between bone and implant plays a crucial role in this process, coatings and surface treatments are used to improve cell adhesion and promote osteointegration [

2].

Many studies were devoted to prove the capability of advanced materials (such as hydroxyapatite, bioactive glasses, or bioactive polymers), to promote the formation of new bone tissue around the implant. Furthermore, by incorporating specific growth factors and biomolecules it is possible to tune the properties of the coating and enrich its functionalities to stimulate tissue regeneration and to accelerate the healing process [

3]. Among deposition techniques, electrophoretic deposition (EPD) has emerged as promising room temperature method to achieve precise control over coating properties [

4]. EPD offers a versatile approach to accurately deposit uniform and adherent coatings with controlled thickness and composition. Through EPD, the coating process can be adapted to accommodate various implant geometries and materials, facilitating the customization of implants based on specific patient requirements [

5].

EPD also allows to deposit nanocomposite films obtaining coatings that possess the properties of both organic components, such as polymers, and inorganic compounds, such as metals or metal oxides [

6]. Among natural polymer, Chitosan (Cs), derived from chitin, has favourable characteristics such as biodegradability, biocompatibility and low immunogenicity, making it an attractive candidate for biomedical applications [

7]. The ability of Cs to promote adhesion, proliferation and cellular differentiation further increases its suitability for bone tissue engineering [

8]. The main source of Cs is waste from the fishing industry, but alternative sources of Cs have recently been considered, of which insects seem to be the most promising [

9]. Extracting Cs from insects emerges as a more advantageous process than alternative sources, in terms of extraction method, chemical consumption, time and yield. [

10]. Moreover, it was shown that the integration of Cs and silver nanoparticles (Ag NPs) through electrophoretic deposition has an immense potential to improve the biocompatibility and antimicrobial properties of bone implants [

11]. In fact, the presence of Ag NPs enrich the Cs matrix with antimicrobial properties, addressing the widespread problem of implant-related infections, which significantly affect the outcomes of surgical operations in patients [

12,

13].

Recently the attention of researchers has been focused on the development of green methodologies for the preparation of Ag NPs. Several studies report the use of biological reducing agents such as microorganisms or plant extract for nanoparticles production [

14,

15]. Laser Ablation in Liquid (LAL) can be considered a sustainable technique and has proven to be a suitable strategy to prepare NPs of metals, oxides and alloys with a composition and morphology depending on the physical-chemical properties of the target and the liquid and on the laser source parameters [

16].

LAL is based on the ablation of a solid target in a liquid environment. When an intense laser pulse hits the solid surface, the local evaporation of the target takes place with the formation of a laser-induced hot plasma that is confined in the liquid environment. The evaporation of the surrounding liquid leads to the formation of a Cavitation Bubble (CB), characterized by an oscillating dynamics. The NPs nucleate and grow in the CB and are released into the liquid at the bubble collapse [

17].

This study reports on the production and characterisation of coatings for metallic bone implants using EPDs. The physico-chemical and functional properties of films obtained by depositing Ag@Cs and Cs from insects were compared with those of films obtained by depositing commercial Cs under the same experimental conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Processing

Cs solutions (1g/l) were prepared by dissolving low MW Cs (100-300 kDa, 70% deacetylation degree, purchased from Acros) in 0.1% acetic acid (pH=4.2). The solutions were kept under agitation at a temperature of 35°C for 4 hours until a complete Cs dissolution. The same procedure was followed to prepare the 1g/l solution by using Cs obtained from

Hermetia illucens exuviae (35-40 kDa, 90 % deacetylation degree) (CsE) [

18].

Ag Nps were prepared by LAL technique. A nanosecond Nd:YAG laser source, (wavelength of 532 nm, a pulse duration of 7 nm, a repetition frequency of 10 Hz, and power of 150 mW) was focused vertically on the Ag target (Goodfellow) by a 5 mm lens. The column of liquid above the target surface was fixed at 2 cm. Colloidal solutions (AgNPs@Cs) with a concentration of Ag NPs of 8 μg/ml were obtained for ablation time of 45 min.

316L stainless steel foils of 0.2 mm thickness were used as electrodes for the EPD process. The electrodes (3 × 1,5 cm) were cleaned with acetone and isopropanol mixture before the deposition. 1g/l Cs, 1g/E-Cs and AgNPs@Cs solutions were kept in agitation for about one hour before deposition. Direct current EPD has been used at the voltage of 10 V using a TTi power supply (EX752M Multi-mode PSU, UK) for different deposition times. The experimental conditions used for the depositions are reported in

Table 1.

2.2. Physic-Chemical Characterization

The morphology and size distribution of Ag NPs were determined using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) by using a G2 20 FEI Tecnai instrument. For this, some drops of the AgNPs@Cs solution were dropped on a Holey carbon-coated copper grid (Agar Scientific). Uv-vis absorption spectra were obtained by a Specord 50/PLUS Analytic Jena spectrophotometer. All spectra were acquired in the 200 to 800 nm range. IR characterization of the coatings was carried out by a Nicolet 6700 spectrometer operating in ATR mode, in the 4000 to 400 cm-1 range. The XRD diffrectograms were obtained using the Rigaku, (MiniFlex 600) diffractometer, using Cu-Kα radiation at 40 kV and 32 mA. Diffraction patterns were acquired in the 2θ range of 5°-60°, with a step size of 0.040° and a time per step of 4 s. The wetting properties were evaluated by contact angle measurement for each coating using the KRÜSS DSA30 drop shape analyser. Five drops of distilled water with a volume of 3 μl were dropped on the centre of each sample to avoid any effects from the edges. Then the mean value and the standard deviation of the contact angle were calculated. A scanning electron microscopy (SEM) equipped with an energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) analyser (SEM Carl Zeiss Auriga with EDS, X-MaxN Oxford Instruments) was used to study the surface morphology and elemental composition of coatings. The mechanical properties of the coating were evaluated qualitatively through cyclic bending test. During this test, the coated substrate was bent around an axis of 180° until the coated surface became parallel to the other half of the substrate. Subsequently, the substrate was folded back to its original position before starting the next bending cycle. Over the entire process, the distance between the two halves of the folded substrate was maintained constantly less than 2 mm [

19].

2.3. Antibacterial Activity

The antibacterial activity of coatings against the gram-positive bacteria Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) and gram-negative Escherichia coli (E. coli) was evaluated. A suspension of S. aureus and E. coli bacteria was inoculated into a sterile Lysogeny broth (LB) medium overnight. The optical density was then adjusted to 0.015. Aliquots of the bacterial suspensions were added to the samples, previously sterilized by UV and immersed in sterile LB; the stainless steel uncoated that was used as a control group. After a 24-hour incubation at 37 °C, these extracts were completely homogenised then 100 μl were collected from each and placed in a 96-well plate for the analysis. A second test has been performed by incubating the coating for 24 h at 37 °C in sterile culture medium before the inoculation of bacterial strains. A microplate reader (PHOmo, anthos Mikrosysteme GmbH, Germany) was used for the optical density measurements at 600 nm.

2.4. Cell Viability Test

For the viability test, MG63 cells (human osteosarcoma cell line) were use as model cell. This cell line is commonly used to characterize biomaterials intended to be in contact with bone, as MG-63 cells express many of the characteristics of normal osteoblasts [

20]. Cells were cultured in cell culture polystyrene flasks using Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Gibco, Schwerte, Germany), supplemented with 10 vol. % fetal bovine serum (FBS, Sigma-Aldrich) and 1 vol.% penicillin/streptomycin (Pen-Strep; Sigma-Aldrich). After UV sterilization, the coatings were placed in a 24-well plate, 1x10

4 cells were seeded in each well on the sample surface and incubated at 37.5% CO

2 for 24 h, 48 h and 72 h. Each coating has been tested in triplicate. At the end of the incubation time, the culture medium was removed and washed with phosphate buffer solution (PBS), then 300 µl of WST-8 reagent (1% reagent solution WST-8 (Sigma-Aldrich) and 99% complete fresh medium) have been added to each well and the cells have been incubated for ~2 hours at 37 °C and 5% CO

2. After incubation, 100 μl of the solution was transferred from each well to a 96-well plate. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm using an Omega FLUO star microplate reader (BMG Labtech) UV-Vis spectrometer.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The experimental results are represented as the mean value ± standard deviation (SD) for each group of samples. The statistical significance between control and samples was analysed using OriginLab 2018 software (OriginLab Corporation). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA test with Tukey’s post hoc tests, with a probability of p<0.05 considered as being statistically significant.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. AgNPs@Cs Composite

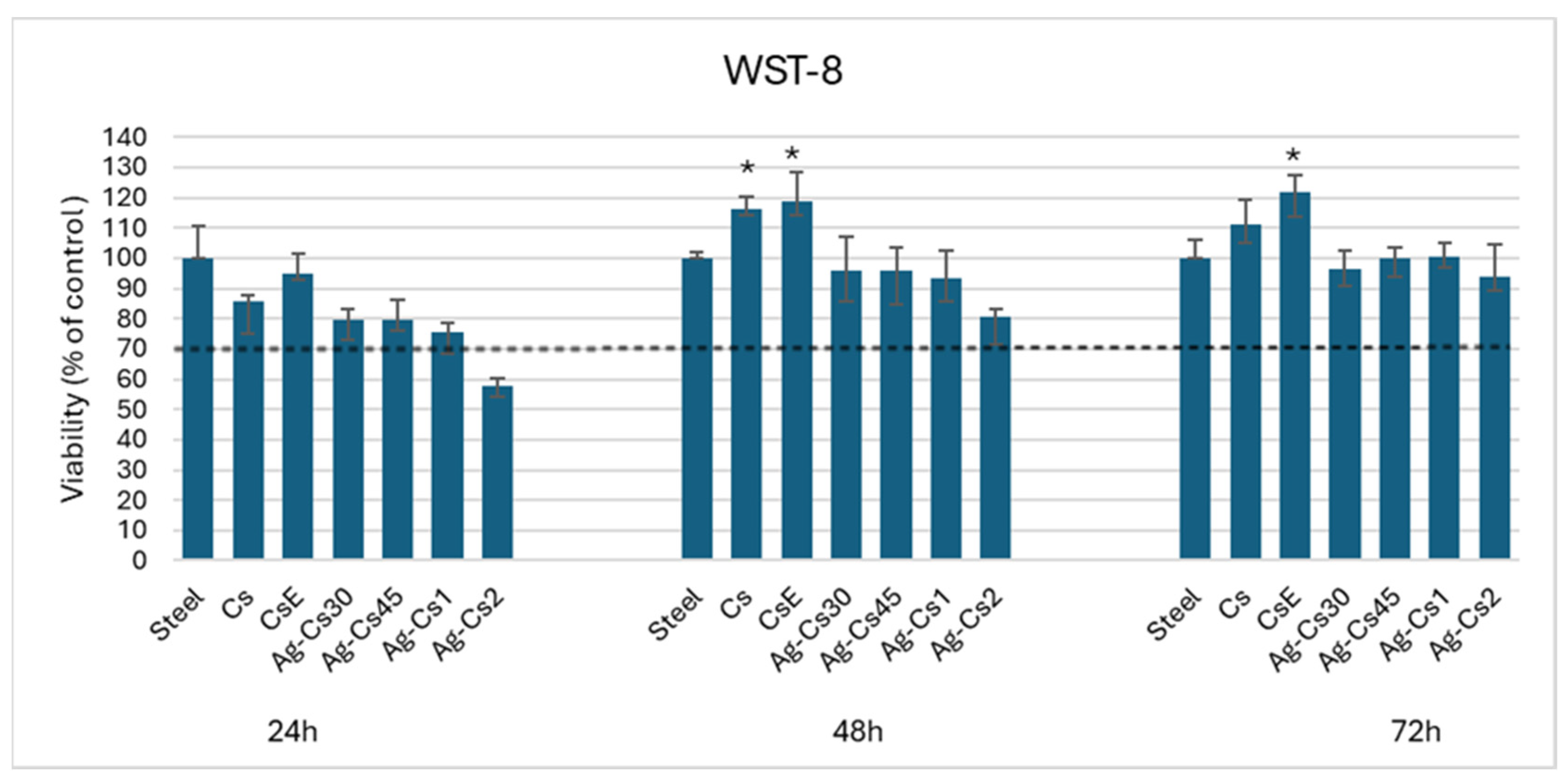

Nanosecond LAL technique has been used to directly generate Ag NPs in the polymer solution. The presence of Ag NPs in the Cs solution was confirmed by surface plasmon resonance (SPR), where the band of silver is centred at 403 nm, as reported in

Figure 1a.

TEM analysis allows to observe spherical NPs with a mean diameter of 30±13 nm, as shown in

Figure 1b,c. The presence of few larger particles (with a diameter of several tens nanometres) can be related to secondary melting effects due to the re-irradiation of the colloidal solution [

21]. Crystalline domains are clearly visible in larger edge shaped particles. The lattice distance of 0.24 nm, evaluated by Fast Fourier Transformation (FFT), matches the (111) lattice distance of the fcc crystal structure of silver (

Figure 1d).

3.2. Coatings

3.2.1. Physic-Chemical Characterizations

All coatings were prepared by EPD as described in

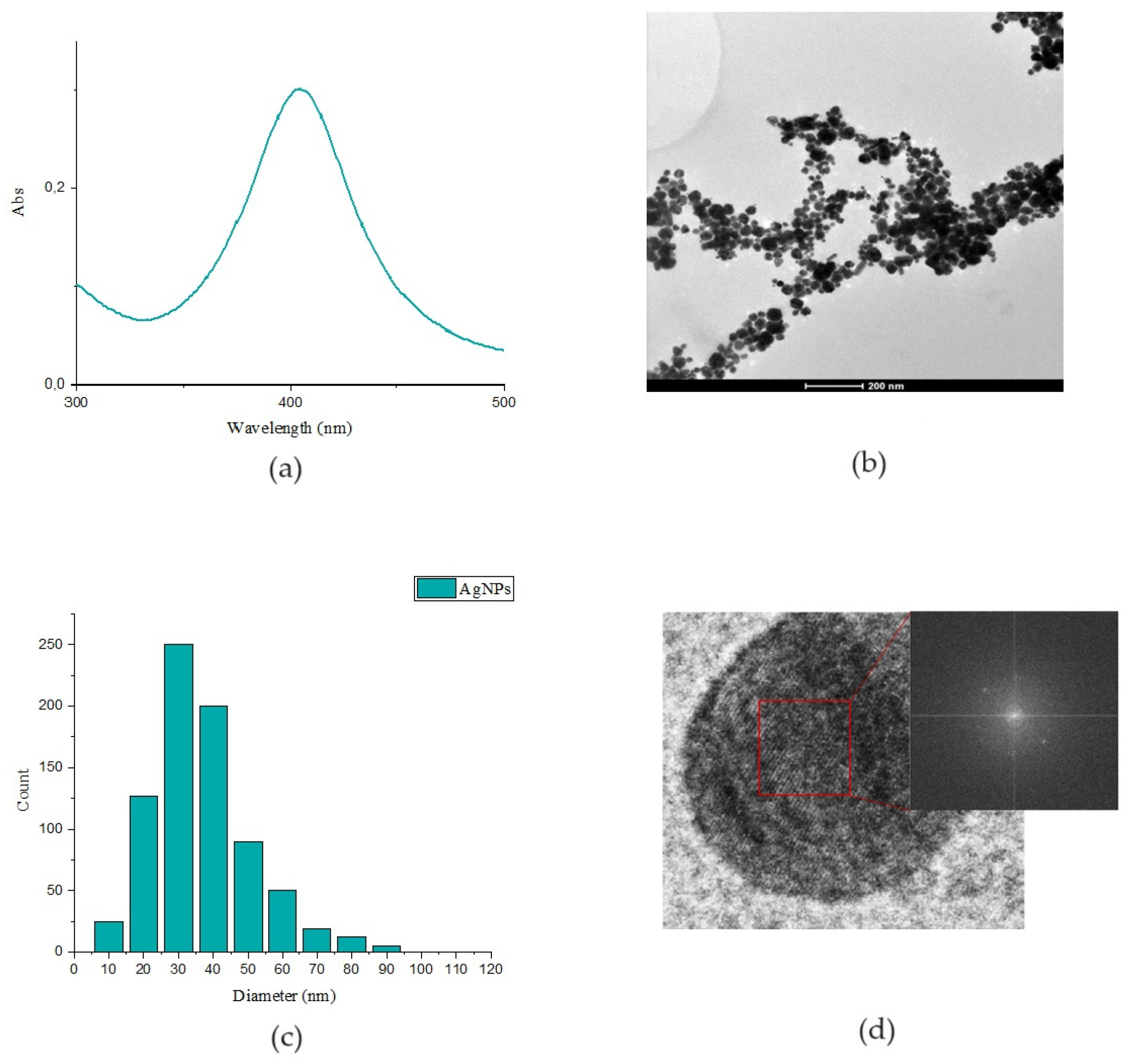

Table 1 and were characterized by FTIR, XRD, and SEM techniques. The FTIR spectra of Cs, CsE, Ag-Cs1 and Ag-Cs2 are reported in

Figure 2 (a). All coatings present all the signals characteristic of the Cs functional groups. In particular, the broad band at 3400 cm

-1 is associated with the stretching vibrations of O-H and N-H groups. The peaks at 2870 cm

-1 and 1374 cm

-1 correspond to the asymmetric stretching vibrations of the aliphatic CH groups and the symmetric deformation vibrations of the CH

3 groups, respectively. Other distinctive peaks are the OH bending vibration at 1430 cm

-1 and the C=O stretching peaks of amides I and II at 1673 cm

-1 and 1590 cm

-1, respectively [

22].

The X-ray diffraction patterns of Cs, CsE, Ag-Cs1 and Ag-Cs2, are reported in

Figure 2 (b). All coatings present a broad band centered at 20° that can be related to Cs [

23]. Moreover, in XRD spectra of Ag-Cs1 and Ag-Cs2, it can be observed a weak signal at 2θ 37.8°, that can be associated to fcc Ag (JPD 01-089-3722). The intensity of this peak increases with the increasing of the deposition time.

The wetting and hydrophobicity properties of coatings were evaluated through water contact angle measurement. Usually, lower contact angles indicate lower hydrophobicity or better wettability. The stainless steel used as substrate has a contact angle ranging from 90° to 100°, the presence of the coatings improves wettability by lowering the contact angle. More specifically, Cs and CsE have a contact angle between 60° and 70°. As shown in

Figure 2 (c), the deposits obtained from Ag NPs@Cs solution show a trend in agreement with the deposition time: as time increases there is a lowering of the contact angle values, ranging from 80°±5° to 70°±7° to 65°± 5° for depositions of time of 30s, 45s and 1 and 2 min, respectively. Several studies indicate that to achieve the best cellular adhesion, the contact angle of the coatings should be within the range of 40° to 70° [

24]. However, it is important to note that this range may vary depending on the type of cell considered [

25]. In the context of bone cells, specifically, it has been suggested the ideal range is between 35° and 85°, with an optimal value of 55° [

26]. As a result, while the contact angle of all coatings is within the suitable range, it emerged that Ag-Cs coatings tend to approach the upper limit of this value.

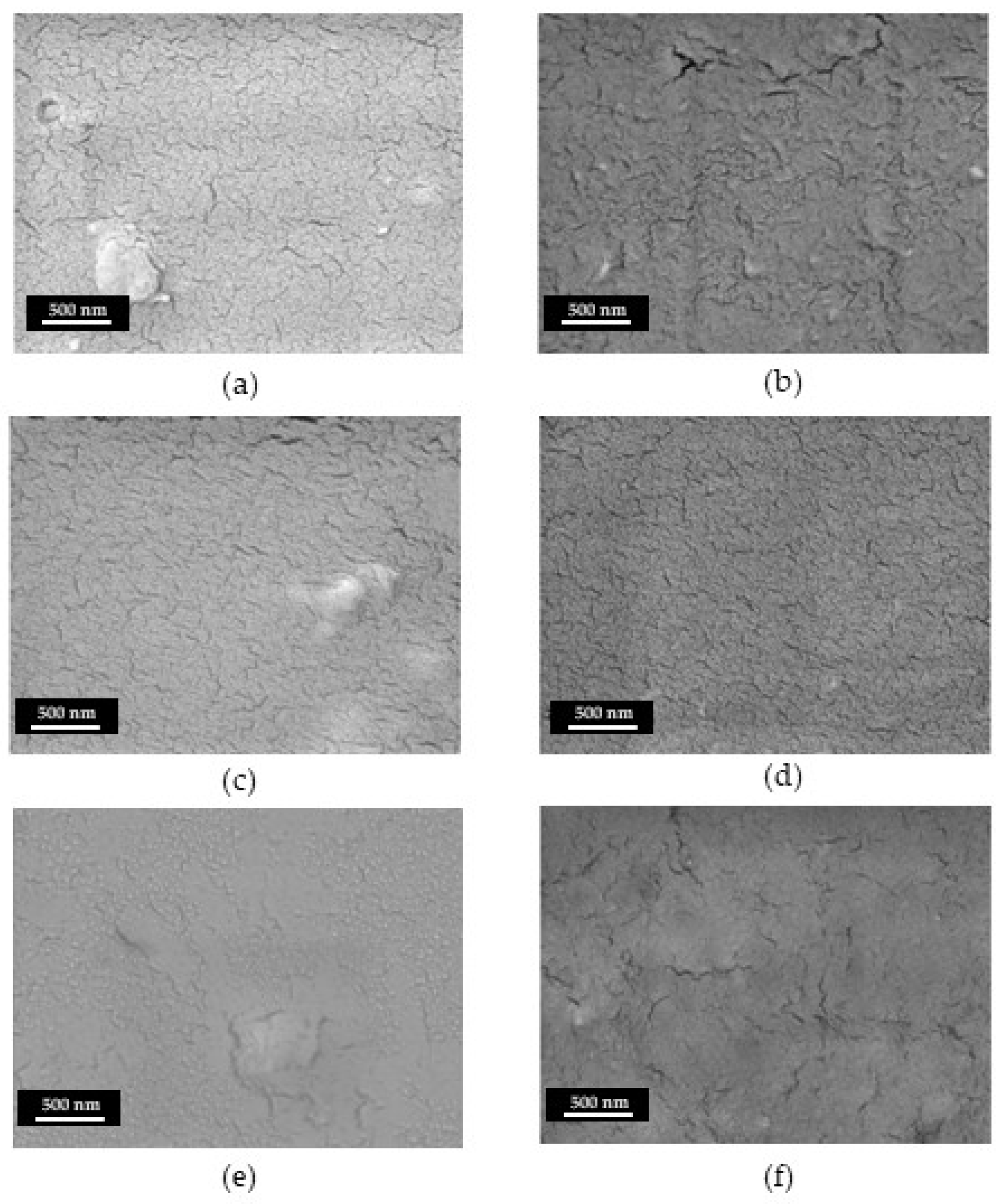

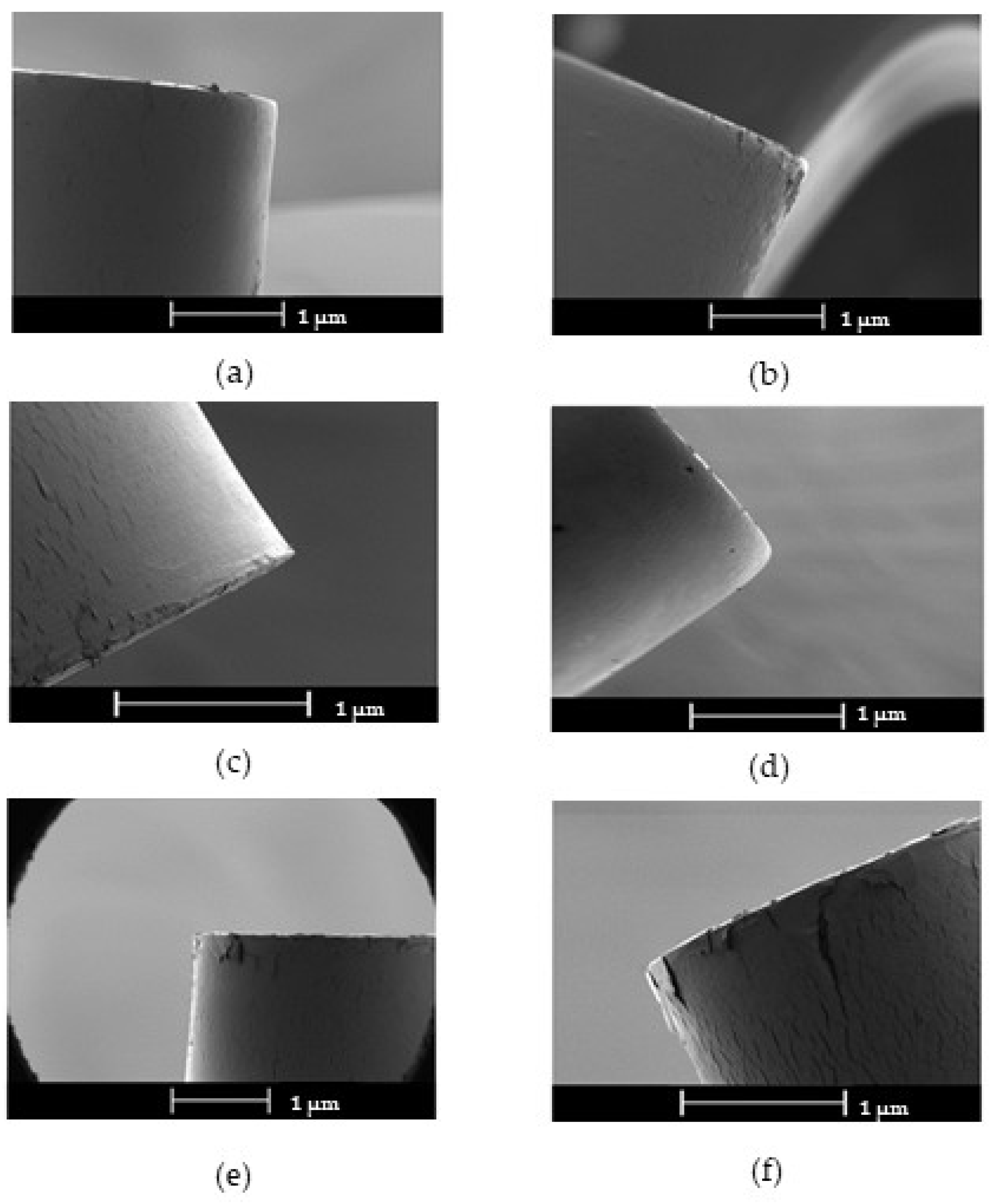

All coatings present a similar compact and homogeneous surface morphology, as can be observed in SEM images reported in

Figure 3a-f. Some shallow cracks are present of in all deposits, these cracks became sharper and deeper for CsE and Ag-Cs2. By SEM cross-section analysis it was possible to evaluate the thicknesses of the various coatings, (

Table 2). A direct correlation between deposition time and thickness can be argued. EDX analysis confirm that Ag NPs have been successfully transferred during the EPD process with an Ag w/w% of about 0.8%, irrespective from the deposition time.

To assesses the adhesion of the coatings the cyclic bending test was used [

19]. In

Figure 4a-f are reported the cyclically bent coatings in the region where the tensile strength is at the maximum. After 10 bending cycles, Cs and CsE samples show a relatively compact surface with few micro-cracks and loose areas on the edge of the coating. No visible cracks or detachments were observed after 10 bending cycles for Ag-Cs45 coating and few cracks and some slight lifting are present for Ag-Cs30 and Ag-Cs1. On the other hand, Ag-Cs2 coating clearly shows many cracks and lifting after 10 bending cycles. Detachment of the coating during the cyclic bending test can be attributed to the thickness of the polymer leading to less flexibility of the coating. Therefore, the Ag-Cs1 coating seems to be ideal compromise to achieve compact and homogeneous films with high adhesion to the substrate.

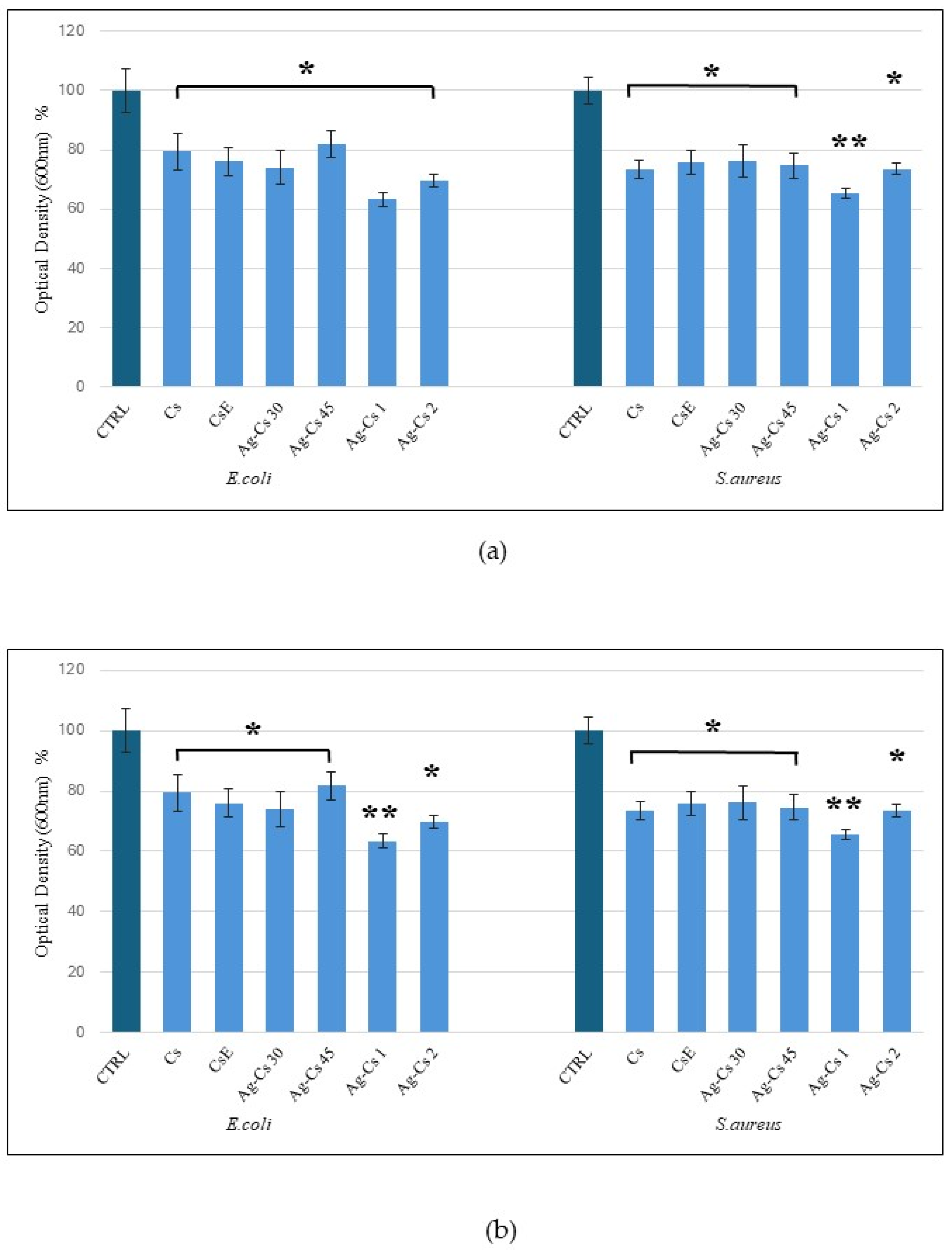

3.3. Antibacterial Activity

The results of the antimicrobial test showed that all coatings tested exhibited an inhibitory effect on bacterial proliferation, both on

S. Aureus gram-positive and on

E. Coli gram-negative bacteria. All coatings present antimicrobial activity against both bacterial strains as reported in

Figure 5a, with a decrease in growth of 15% for all coatings except for Ag-Cs1 showing 25% inhibitory activity. The results are in accordance with those reported in similar works [

11,

27]. After 24-hour incubation in the culture medium, an increase in the limitation of proliferation that exceeds 20% for all coatings is evident, except for the coating Ag-Cs1 that gave the best result by showing an inhibition of 35% (

Figure 5b).

It appears, therefore, that a more prolonged contact between coating and medium allows a stronger inhibitory action against the bacterial strains tested. The Ag-Cs1 sample proves to have the best bactericidal performance in both tests. CsE and Cs samples showed comparable antimicrobial activity in both tests, confirming that the antibacterial activity of commercial chitosan and chitosan obtained from

Hermetia Illucens exuviae is comparable. [

28,

29].

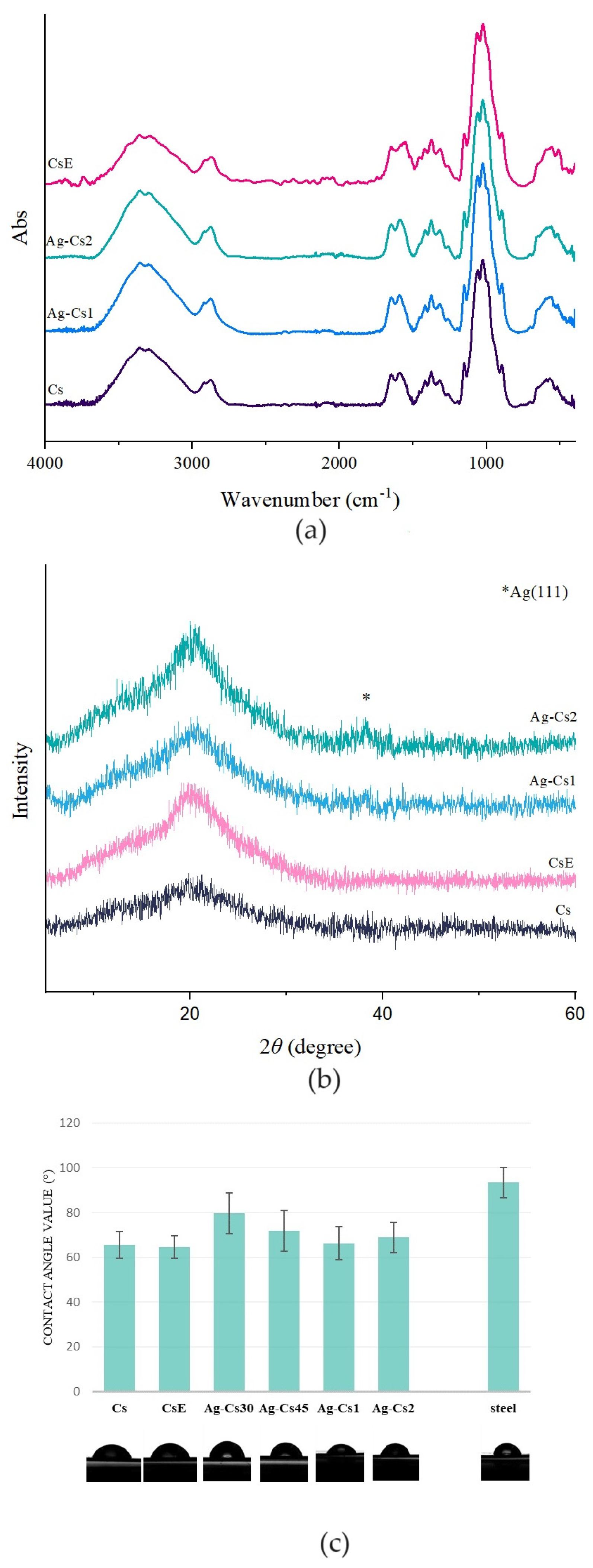

3.4. Viability Test

The cell viability test was performed on human osteoblasts like cells (MG-63) at three different times; 24 h, 48 h and 72 h and by using uncoated stainless steel as control. In the 24 h test, the data show reductions of 10-15% in mitochondrial cell activity in samples Cs and CsE compared to the control. Chitosan has been shown not to be toxic to MG-63 cells [

30], so it is assumed that the reason for this decrease in viability may be related to the relatively low number of cells attached. It is known that cellular adhesion first involves non-specific forces, such as electrostatic or van der Waals forces, followed by specific interactions with the substrate, which are mediated by cell receptors [

31]. However, chitosan lacks specific domains to integrate with receptors or cell recognition sequences (such as RGD) that promote cellular adhesion [

32]. As a result, fewer cells are likely to attach to the coating surfaces only through non-specific electrostatic interactions between the protonated amine groups of the glucosamine unit in chitosan and the negatively charged groups of the carboxylate and sulphate in proteoglycans on the cell surface [

33]. Ag-Cs30, Ag-Cs45, and Ag-Cs1 coatings show values of viability ranging from 80% to 75%, these deposits prove not to be toxic to the MG-63 cell line. Ag-Cs2 shows a cellular viability below 60%. This is probably due to an excessive release of silver ions in the culture medium that by interaction with cellular metabolism could slow down cell proliferation [

34].

In the 48h test, Cs and CsE coatings provide a substrate of adhesion and proliferation that is slightly better than the control with a cell viability value of about 117% and 119%, respectively. On the other hand, the Ag-Cs30, Ag-Cs45, and Ag-Cs1 deposits show values comparable to the control, and the Ag-Cs2 coating shows a cell viability value of around 80%. Finally, in the 72h test, Cs and CsE samples show cell proliferation with viability values of 110% and 120%, respectively. At the same time, the deposits of Ag-Cs30, Ag-Cs45, Ag-Cs1, and Ag-Cs2 show values comparable to the control.

The Cs and CsE coatings at times 48 h and 72 h show to be suitable substrates for cell growth, compared to the control. This is partly due to the fact that their contact angles are within the optimal range for cellular adhesion; i.e., from 40° to 70° [

24], and also by considering the ability of chitosan to stimulate cell growth [

35]. The comparison also shows how the CsE deposit stimulates proliferation more strongly than Cs at all time-points. This is probably linked to the degree of acetylation. In a previous study it has been shown that the degree of acetylation affects cell adhesion and proliferation; low degrees of acetylation are the best substrates for the proliferation of the MG-63 cell line [

36].

Figure 6.

Cell viability of osteoblast-like cells (MG-63) cultured on coatings after 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h of incubation. Stainless steel was used as a control. Asterisks (*) denote significant differences (p < 0.05).

Figure 6.

Cell viability of osteoblast-like cells (MG-63) cultured on coatings after 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h of incubation. Stainless steel was used as a control. Asterisks (*) denote significant differences (p < 0.05).

4. Conclusions

Commercial chitosan (from maritime origin), chitosan from an alternative source (Hermetia illucens exuviae), and chitosan enriched with silver NPs obtained by laser synthesis in the polymeric solution (AgNPs@Cs) were considered to coat 316 L stainless steel substrates by EPD method. The optimization of the deposition parameters allowed the deposition of adherent and uniform coatings with controlled thicknesses. All the coatings showed antibacterial properties that resulted in an effective limiting of bacterial growth on both gram-positive and gram-negative strains, with the Ag-Cs1 coating showing the highest antibacterial activity. All coatings led to effective interaction with osteoblast-like cells, being non-cytotoxic. Furthermore, Cs and CsE revealed not only the lack of toxicity but also the ability to promote cells proliferation compared to stainless steel, the CsE has also shown a better cellular compatibility profile at all incubation times compared to the commercial Cs. This study paves the way for the use of alternative source of chitosan and chitosan enriched with silver nanoparticles as antibacterial coatings for biomedical implants.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M, M.C, A.D. and A.R.B; methodology, M.M, M.C and R.A.; validation, A.D., M.T. and P.F.; investigation, M.M; resources, M.T., P.F. and A.D.; data curation, M.M., M.C., A.D.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M., M.C., A.D.; writing—review and editing, R.A.,A.R.B.; supervision, A.R.B., R.T., A.D.; project administration, A.D. and A.R.B.; funding acquisition, A.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Rezvan Azari would like to thank the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) for granting a scholarship to pursue doctoral studies.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhang BGX, Myers DE, Wallace GG, Brandt M, Choong PFM. Bioactive coatings for orthopaedic implants-recent trends in development of implant coatings. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15(7):11878-11921. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohara S, Suthakorn J. Surface coating of orthopedic implant to enhance the osseointegration and reduction of bacterial colonization: a review. Biomater Res. 2022;26(1):1-17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi MU, Kulkarni SP, Choppadandi M, Keerthana M, Kapusetti G. Current state of art smart coatings for orthopedic implants: A comprehensive review. Smart Mater Med. 2023;4(1):661-679. [CrossRef]

- Long S, Zhu J, Jing Y, He S, Cheng L, Shi Z. A Comprehensive Review of Surface Modification Techniques for Enhancing the Biocompatibility of 3D-Printed Titanium Implants. Coatings. 2023;13(11):1917-1946. [CrossRef]

- Boccaccini AR, Keim S, Ma R, Li Y, Zhitomirsky I. Electrophoretic deposition of biomaterials. J R Soc Interface. 2010;(7):581-613. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhitomirsky I. Electrophoretic deposition of organic-inorganic nanocomposites. J Mater Sci. 2006;41(24):8186-8195. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Gómez CP, Cecilia JA. Chitosan: A Natural Biopolymer with a Wide and Varied Range of Applications. Molecules. 2020;25(17):3981-4024. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam MM, Shahruzzaman M, Biswas S, Nurus Sakib M, Rashid TU. Chitosan based bioactive materials in tissue engineering applications-A review. Bioact Mater. 2020;5(1):164-183. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehman K ur, Hollah C, Wiesotzki K, et al. Insect-Derived Chitin and Chitosan: A Still Unexploited Resource for the Edible Insect Sector. Sustain. 2023;15(6):4864-4898. [CrossRef]

- Mohan K, Ganesan AR, Muralisankar T, et al. Recent insights into the extraction, characterization, and bioactivities of chitin and chitosan from insects. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2020;105:17-42. [CrossRef]

- Ghalayani Esfahani A, Sartori M, Bregoli C, et al. Bactericidal Activity of Silver-Doped Chitosan Coatings via Electrophoretic Deposition on Ti6Al4V Additively Manufactured Substrates. Polymers (Basel). 2023;15(20):4130-4146. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramezani M, Ripin ZM. An Overview of Enhancing the Performance of Medical Implants with Nanocomposites. J Compos Sci. 2023;7(5):199-223. [CrossRef]

- Barabadi H, Jounaki K, Pishgahzadeh E, et al. Antiviral potential of green-synthesized silver nanoparticles. Handb Microb Nanotechnol. International Journal of Nanomedicine 2022;14:285-310.

- Nie P, Zhao Y, Xu H. Synthesis, applications, toxicity and toxicity mechanisms of silver nanoparticles: A review. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2023;253:114636-114648. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srikar SK, Giri DD, Pal DB, Mishra PK, Upadhyay SN. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles: A Review. Green and Sustainable Chemistry. Green Sustain Chem. 2016;6(1):34-56. [CrossRef]

- Jiang Z, Li L, Huang H, He W, Ming W. Progress in Laser Ablation and Biological Synthesis Processes: “Top-Down” and “Bottom-Up” Approaches for the Green Synthesis of Au/Ag Nanoparticles. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(23):14658-14592.

- Zeng H, Du XW, Singh SC, et al. Nanomaterials via laser ablation/irradiation in liquid: A review. Adv Funct Mater. 2012;22(7):1333-1353. [CrossRef]

- Triunfo M, Tafi E, Guarnieri A, et al. Characterization of chitin and chitosan derived from Hermetia illucens, a further step in a circular economy process. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):1-17. [CrossRef]

- Chen Q, Cabanas-Polo S, Goudouri OM, Boccaccini AR. Electrophoretic co-deposition of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) reinforced alginate-Bioglass® composite coating on stainless steel: Mechanical properties and in-vitro bioactivity assessment. Mater Sci Eng C. 2014;40:55-64. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dvorakova J, Wiesnerova L, Chocholata P, et al. Human cells with osteogenic potential in bone tissue research. Biomed Eng Online. 2023;22(1):1-28. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Arias M, Boutinguiza M, del Val J, et al. RE-irradiation of silver nanoparticles obtained by laser ablation in water and assessment of their antibacterial effect. Appl Surf Sci. 2019;473:548-554. [CrossRef]

- Kumirska J, Czerwicka M, Kaczyński Z, et al. Application of spectroscopic methods for structural analysis of chitin and chitosan. Mar Drugs. 2010;8(5):1567-1636. [CrossRef]

- Naito PK, Ogawa Y, Kimura S, Iwata T, Wada M. Crystal transition from hydrated chitosan and chitosan/monocarboxylic acid complex to anhydrous chitosan investigated by X-ray diffraction. J Polym Sci Part B Polym Phys. 2015;53(15):1065-1069. [CrossRef]

- Arima Y, Iwata H. Effect of wettability and surface functional groups on protein adsorption and cell adhesion using well-defined mixed self-assembled monolayers. Biomaterials. 2007;28(20):3074-3082. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heise S, Forster C, Heer S, et al. Electrophoretic deposition of gelatine nanoparticle/chitosan coatings. Electrochim Acta. 2019;307:318-325. [CrossRef]

- Pawłowski Ł, Bartmański M, Strugała G, Mielewczyk-Gryń A, Jazdzewska M, Zieliński A. Electrophoretic deposition and characterization of chitosan/eudragit E 100 coatings on titanium substrate. Coatings. 2020;10(7):607-625. [CrossRef]

- Cometa S, Bonifacio MA, Baruzzi F, et al. Silver-loaded chitosan coating as an integrated approach to face titanium implant-associated infections: analytical characterization and biological activity. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2017;409(30):7211-7221. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guarnieri A, Triunfo M, Scieuzo C, et al. Antimicrobial properties of chitosan from different developmental stages of the bioconverter insect Hermetia illucens. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):1-12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohan K, Ganesan AR, Muralisankar T, et al. Recent insights into the extraction, characterization, and bioactivities of chitin and chitosan from insects. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2020;105:17-42. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirosaki Y, Tsuru K, Hayakawa S, et al. In vitro cytocompatibility of MG63 cells on chitosan-organosiloxane hybrid membranes. Biomaterials. 2005;26(5):485-493. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalili AA, Ahmad MR. A Review of cell adhesion studies for biomedical and biological applications. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(8):18149-18184. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Z, Cheng X, Yao Y, et al. Electrophoretic deposition of chitosan/gelatin coatings with controlled porous surface topography to enhance initial osteoblast adhesive responses. J Mater Chem B. 2016;4(47):7584-7595. [CrossRef]

- Souza PR, de Oliveira AC, Vilsinski BH, Kipper MJ, Martins AF. Polysaccharide-based materials created by physical processes: From preparation to biomedical applications. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13(5):621-668. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie H, Wang P, Wu J. Effect of exposure of osteoblast-like cells to low-dose silver nanoparticles: uptake, retention and osteogenic activity. Artif Cells, Nanomedicine Biotechnol. 2019;47(1):260-267. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul W, Sharma CP. Chitosan and Alginate Wound Dressings: A Short Review. Trends Biometerials Artif Organs. 2004;18(1):18-23.

- Amaral IF, Cordeiro AL, Sampaio P, Barbosa MA. Attachment, spreading and short-term proliferation of human osteoblastic cells cultured on chitosan films with different degrees of acetylation. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2007;18(4):469-485. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).