1. Introduction

In the 1970s, developed countries faced a complex of socio-economic problems in rural areas: agricultural overproduction, declining farmer incomes, and an exodus of people to cities, which marked the end of the era of old strategies for developing rural communities and finding new ways to provide for themselves [

1]. This coincided chronologically with a surge of eco-alarmism and nature-centric sentiments in society, as well as a conceptual reevaluation and recognition of the true value of natural resources. A simple answer to the difficult question of socio-economic development of rural areas while maintaining the sustainability of natural complexes was rural tourism [

2], which became a multiplier for the development of rural areas and triggered additional economic and social benefits for farmers and rural communities [

3]. One of its key advantages is the diversity of natural, agricultural, and socio-economic resources in rural areas, as well as the easy interchangeability and complementarity of tangible and intangible assets based on a balance of tradition and innovation, and the ability to adapt to the changing needs of travellers. Since then, there has been a significant transformation in rural tourism, from the simple exploration of rural attractions to the development of niche tourism products for a new generation [

4]. The development of rural tourism in Western countries was rapid, and its popularity among travellers was so high that the issue of its sustainability became systemic [

5]. The Covid-19 pandemic has become a global trigger for the diversification of rural economies and the elimination of the agrarian invariant. Many countries have taken advantage of the opportunities created by the pandemic, including the closure of borders and foreign tourist destinations, to develop sustainable domestic tourism, particularly rural tourism [

6]. China's successful experience highlights the unprecedented role of the government in promoting rural tourism, which is based on both institutional measures and the strengthening of social capital in rural areas [

7]. Researchers have noted a twofold increase in employment outside of agriculture, and the profitability of rural tourism has increased tenfold compared to the value of agricultural products [

8]. At the same time, some developing and transition economies continue to show rejection of alternative ways of developing rural economies, while maintaining their traditional agricultural profile, which is growing stronger every year, not because of objective circumstances, but due to government intervention and support.

The purpose of this article is to identify the reasons for the absolute underdevelopment of rural tourism in the agricultural regions of Kazakhstan. The article tests the hypothesis that the objective prerequisites for activating the potential of rural tourism are not the availability of natural, agricultural, and socio-economic resources, but the lack of interest on the part of the actors: the government, farmers, and members of rural communities. The additional value of the study lies in highlighting the importance of often-ignored socio-historical factors that directly influence the transformation of the production sector in rural areas of former communist countries with planned economies. An analysis of changes and the state of agricultural development in post-Soviet Kazakhstan can help assess the negative impact of continued government support for the agricultural sector on the diversification of the rural economy and the development of the services sector.

When implementing the research design, we used the methods of desk research, which include 4 groups of methods (content analysis, historical and genetic analysis, statistical and factual data analysis, and observation methods), and semi-structured individual interviews. For the survey, which was conducted between June and August 2025, 400 respondents (residents of Petropavlovsk) were selected, represented by people of different age groups: young (18), middle (98) and elderly (284), who use suburban gardens (the so-called dachas), and the purpose of the survey was to identify their motives for visiting dachas. In addition, the article uses the results of the authors' own research in rural areas of the North Kazakhstan region (1994-2025).

The study faced a number of limitations:

1. The complete lack of statistical data on rural tourism both in Kazakhstan as a whole and in the North Kazakhstan region;

2. The lack of freely available information on qualitative (crop structure) and quantitative (average area of arable land) characteristics of land use, as well as income levels of both large and small farmers in the region. This information is also not provided by the Department of Agriculture and Land Relations;

3. The reluctance of farmers to participate in the discussion of preliminary conclusions.

2. The Development Potential of Kazakh Agritourism

A review of publications by Kazakhstani and foreign authors covering the issues of rural (agricultural) tourism in Kazakhstan has demonstrated that, due to its underdevelopment, all of them are rather declarative in nature: they assess its potential or point out the significant advantages of this service sector. In reality, however, Kazakhstan, including Northern Kazakhstan, offers many tourist attractions, both natural and cultural (

Table 1).

Today, rural tourism in Kazakhstan is not even at the stage of its inception, but only at the stage of understanding its role and recognizing its potential for regional development. An analysis of foreign models of rural tourism development and areas of specialization showed the complexity of their implementation in Kazakhstan, as there is no institutional framework, except for the mention in the Concept for the Development of the Tourism Industry [

19]. Some researchers associate the development of rural tourism exclusively with agriculture. Given the high degree of government regulation of the agro-industrial complex, it is proposed to include rural tourism in the list of state support measures for the industry by integrating agricultural activities with tourism through intersectoral cooperation [

20], especially in the capital region as the most promising [

21]. On the contrary, other authors have identified and evaluated the potential of natural and climatic, cultural and historical, socio-geographical, and other factors in addition to agriculture. The article identifies the subtypes of rural tourism, identifies the factors hindering its development in Kazakhstan, and provides recommendations based on the best foreign practices [

12].

Weak development of the transport network and poor quality of transport infrastructure limit the tourist accessibility of rural areas and undermine their competitiveness in the tourism market [

22]. The underdevelopment of social infrastructure (healthcare, public services, etc.) also hinders the development of tourism in rural areas. An audit of all types of resources is necessary to understand the potential of rural tourism, which can contribute to the diversification of the rural economy, the slowdown of urbanization, and the revival of rural areas [

23].

Tleubayeva and the co-authors consider weak digitalization to be a key limiting factor in activating the potential of rural tourism. Its current level is not capable of fully contributing to the renewal of tourism infrastructure and the full-fledged year-round operation of rural tourism facilities. At the same time, the use of information and communication technologies will improve the quality of agritourism services, increasing their accessibility [

24]. Uglis et al. [

25] and Uglis [

26] also point to the importance of internet access as a key factor in choosing agritourism services. First and foremost, based on the example of Poland, these authors point out that the key factors influencing the choice of rural tourism and agritourism offers are the opportunity to spend time with family, regional cuisine and homemade products, the attractive cultural heritage of the region, distance from large cities, and the opportunity to practice sports. In this context, the location of tourist facilities in rural areas, away from large cities, is their main advantage.

The monetization of the material and intangible cultural objects of the Kazakh people is an important tool for the development of rural tourism, which can revive some forgotten crafts, dishes, sports, and games. The synergy of rural ethno-tourism with other types of tourism can have a propulsive effect on the formation of a tourist cluster in rural areas [

13].

According to Ostapenko, in Kazakhstan, agritourism is only a way to reduce social tension and poverty in rural areas, but if its full potential is realized, it can help overcome the country's economic, social, and spiritual crisis [

27].

Long-term sustainable development of Kazakhstan's northern agricultural regions in the context of resource-depleting agriculture and continuous depopulation is impossible without moving away from the agrarian invariant of the rural economy, diversifying the population's income, and developing the service sector. The most preferable option for the service economy is the development of rural tourism, which is the most underestimated segment of the country's tourism market. It is capable of forming sustainable network connections between the economic, environmental, and sociocultural resources of rural areas [

28]

, becoming an alternative to agricultural development in rural areas, and consolidating members of rural communities in solving their accumulated problems (Table 2).

3. Research Area

The North Kazakhstan Region (NKR), a typical agricultural region within Northern Kazakhstan, a large natural and economic region that received a powerful impetus for the development of productive forces during the virgin lands campaign of the 1950s, was chosen for the study. The share of agricultural land is 74%, including 50% of arable land, making it the most developed region in Kazakhstan. Although it ranks second to last in the country in terms of both area (98,000 square kilometres) and population (516,650 people as of September 1, 2025) [

29], NKR is one of the key producers of agricultural products. The agricultural sector accounts for up to 50% of the region's gross regional product and is a monopoly in the rural economy and labour market. However, in the post-Soviet period, the NKR faced an unprecedented depopulation: the change in the socio-economic structure and the decline in production due to a lack of experience in market economy led to a massive outflow of people from rural areas, an increase in the proportion of elderly people (the aging index is the highest in the country at 81), and a decrease in the birth rate (-13.8% compared to 2024) [

29]. As a result, the rural population decreased by 65%, and in the most peripheral areas, it decreased by 3.5 times, while the average density decreased to 2.65 people per square kilometre. The only exceptions are the suburban areas within a 10-15 km radius of the regional centre, which are deeply integrated into the urban labour market. This threatens not only the depopulation of rural areas, but also the acute shortage of labour resources in the agricultural sector and the decline in agricultural production in the foreseeable future.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Post-Soviet Trends in Tourism Development in Kazakhstan

The development of tourism during the Soviet period was limited by the centralized planned economy, which set the direction for the development of the service sector. Mass health and wellness tourism was dominated, supported by a large-scale network of departmental sanatoriums managed by the relevant trade unions. Trade union members (who were automatically all employees) were provided with discounted travel packages for a nominal fee, making this type of tourism accessible and popular among urban residents. With the acquisition of independence and the denationalisation of all service sector institutions, the system of sanatorium and resort treatment has degraded and fallen into decline, while new infrastructure facilities have emerged and tourism patterns have changed. Beach and religious tourism have become the most popular types of tourism in modern Kazakhstan [

30,

31]. Unfortunately, the expected deconcentration of tourism did not occur, on the contrary, the contribution of the three main (and in fact, the only) destinations – the Almaty mountain cluster, Aktau and Shchuchinsk-Borovskaya resort areas – to the national tourist product is regularly growing. In 2024, the share of visits these areas exceeded 79%, and the volume of services provided amounted to 87% of the national level [

29]. Nevertheless, recently, the development of the industry has been characterized by the emergence of premium niche destinations, such as space tourism [

32], social and environmental tourism [

33], and gambling tourism [

34]. At the same time, the lack of competition, outdated infrastructure, and overtourism, which lead to a paradoxical prevalence of the cost of domestic tourism services over outbound tourism [

35], have resulted in the low popularity and minimal demand among Kazakhstan citizens for sustainable local tourism. The development of tourism in the NKR is also characterized by excessive concentration, with over 90% of visits and services provided in the Shalkar-Imantau Resort Zone.

4.2. Tourist and Transport Accessibility of NKR

The transport factor plays a key role in the development of rural tourism, especially considering the vast expanses of Kazakhstan [

22]. In order to confirm or refute the transport-related underdevelopment of rural tourism in NKR, we have analyzed its transport network, which consists of roads and railways. The railway network includes sections of three sub-latitudinal (Trans-Siberian and Central Siberian) and sub-meridional (Trans-Kazakhstan) highways, with a total length of 882 km. They pass through 11 of the 13 administrative districts, as well as the regional centre, Petropavlovsk, connecting NKR with Russia and the neighbouring regions of Northern Kazakhstan. At the same time, the largest resort and recreational area of NKR, the Shalkar-Imantau resort zone, is directly connected to the capital and the nearby regional centers of Kokshetau and Kostanay. However, the backbone of the NKR's transportation network consists of national, regional, and district-level roads. These roads were primarily constructed during the period of active virgin land development, and the region ranks second in terms of road length and first in terms of road density in the country (

Table 3). However, the base of the NKR transportation network consists of national, regional, and district-level roads.

The analysis of the density of the highway network in the North Kazakhstan region demonstrated significant spatial differentiation in the context of administrative districts. However, even in the peripheral Ualikhan district, which has the least developed network, it turned out to be higher than the average Kazakh indicator (

Table 4).

Thus, the region is characterized by high tourist and transport accessibility; therefore, transport is not a limiting factor in the development of rural tourism.

4.3. Causes of the Depressive Development of Kazakhstan's Agricultural Regions

Due to the monofunctional nature of the rural economy in Kazakhstan's agricultural regions, which has been continuously shaped over 270 years of agricultural development, it is crucial to analyze the determinants of rural development based on the phenomenon of agrarianism. The extensive farming practices established in the 20th century and the shift in socioeconomic conditions have not only led to the depressed development of rural areas but also created a negative image and aversion towards rural areas as tourist and recreational destinations.

4.3.1. Bi-Directional Relationship Between Agriculture and Rural Areas in Northern Kazakhstan

The rural area of Northern Kazakhstan began to form in the second half of the 18th century, immediately after the accession of the Kazakhs of the Middle and Younger Zhuzes to the Russian Empire and the beginning of the development of new lands by Cossacks and peasants from the Tobolsk province. However, the institution of nomadic farming of the indigenous population did not undergo major changes until the October Revolution of 1917, despite the gradual withdrawal of pasture lands in favour of wave-like migrating Russian and Ukrainian peasant farmers. The economic and bioecological foundations of nomadic cattle breeding and the traditional way of life of the Kazakh village were undermined by the reduction of pastures and the transfer of their most productive part to the arable land category. This led to the famine of 1930-1932, which caused the death of more than 2 million people [

36] and the mass exodus of 1.3 million people outside the republic, exclusively rural residents [

37]. At the same time, repressed Ukrainians, Poles, and later Germans were massively exiled to Northern Kazakhstan [

38]. The deportees were located only in rural areas, thus creating excessive labour resources, which led to a high proportion of manual labour in organized collective farms, and the extensive nature of agriculture remained from then until the collapse of the USSR.

The virgin land campaign of 1954-1959, due to the massive influx of labor resources from the central regions of the country, completed the formation of Kazakhstan as the grain base of the USSR, but the frontal plowing of 25 million hectares of pastures led to progressive wind erosion and dehumification of arable land [

39]. Agriculture of the steppe frontier with its wheat invariant has been hostage to the arid climate ever since [

40]. Animal husbandry also continued to regress due to administrative intervention: cattle from private subsidiary farms were forcibly withdrawn by the state machine to fulfil the meat harvesting plan, and the number of horses sharply decreased due to mass plowing of pastures. By the end of the virgin land campaign, the formation of a dense network of rural settlements in the north of the country, populated exclusively by migrants, was almost completed [

41]. Thanks to government support, not so much in the form of fixed purchase prices as continuous subsidies to unprofitable farms at the expense of oil revenues, in the 60s and 70s the village's infrastructure flourished, the decline in grain production during lean years was tirelessly dampened by the authorities, tirelessly supporting the trompley of virgin abundance. Thus, a model of extensive farming was formed and implemented, in which, however, peasants were guaranteed a steady income, regardless of the profitability of production.

The collapse of the USSR and independence led to the denationalization of collective farms and state farms. Each resident of the village became the nominal owner of 5 hectares of arable land at his place of residence, which, for objective reasons, he is unable to process and sell due to amendments to the Land Code introduced in 2016 [

42]. As a result, he leases this land share to a local farmer, in return receiving a floating rent (depending on the value of the harvest) in cash or in kind. The breakdown of cooperative ties and the subsequent decline in agricultural production, as well as the technological re-equipment of the industry, provoked large-scale unemployment in rural areas, which is much higher than the official 4.9% [

29], since it does not take into account the self-employed (with a personal subsidiary farm) and seasonal workers.

During the years of independence, due to the financial instability of agricultural enterprises and the reduction of state aid, the village's infrastructure has seriously deteriorated. In addition, living conditions have seriously deteriorated: stove heating of houses remains widespread, central water supply in most rural areas has been disrupted, there is no gas network and organized collection of household waste, mobile communications and the Internet are unavailable in peripheral villages. As a result of population migration, many villages were depopulated [

43], and abandoned houses became a familiar element of the rural landscape. These are serious barriers to the development of agritourism and rural tourism. Uglis and Jęczmyk [

44], using the example of one of the Polish regions, pointed out that today's consumers of agritourism services require a range of attractions, the most important of which are beautiful landscapes and a clean environment.

All of the above processes and phenomena integratively caused the decline of rural areas and naturally formed in the collective consciousness of the townspeople an acute hostility to the countryside and rural lifestyle, given the high degree of contrast [

45]. Rural areas, especially its peripheral areas, are now strongly associated with a zone of discomfort: low-paid agricultural work, unsettled territory, unsatisfactory leisure and living conditions, and limited access to basic goods. This, in turn, completely devalues in the eyes of travellers the tourist and recreational value of the natural resources of interuniverse territories (mountains, forests, lakes, rivers). The problem is all more serious because agritourism can be an important aspect of economic diversification in rural areas. According to Uglis and Jęczmyk [

44], its development can contribute to the creation of new jobs, diversification and stabilization of the local economy, the emergence of an additional market for food products, and improvement of the infrastructure and aesthetics of rural areas. On the other hand, it is the level of local development itself that influences tourist attractiveness, as pointed out by Kosmaczewska [

46]. A poor and neglected village will not be attractive to tourists.

In addition, due to their general accessibility, they are a priori perceived as elementary goods and are considered as an independent resource, abstracted from potential tangible and intangible recreational assets of rural ekistic space, which isn’t interesting for travellers. With regard to Polish conditions, a similar problem was noted by [

47], who states that the low interest in agritourism is because a significant proportion of the population has rural roots and still has relatives and friends in the countryside.

4.4. Multifactorial Underdevelopment of Rural Tourism

4.4.1. Farmers' Conservatism as a Pattern of Behavioural Model of Unwillingness to Restructure the Agricultural Economy

One of the underlying reasons for the stability of the agricultural invariant of the rural economy over the three post-Soviet decades in most post-Soviet countries, including Kazakhstan, was the phenomenon of "red directors" [

48]. This refers to the heads of state farms and collective farms, experienced party officials who held their positions during the Soviet era due to their loyalty to the ideological dogmas of the ruling party rather than their professionalism or business acumen. Moreover, any initiative at the local level that went against the principles of the planned economy and the directives of the party leadership was hypothetically impossible and was suppressed by centralized management and top-down planning. The vast majority of the "Red directors" successfully retained their position after Kazakhstan gained independence, which allowed them to privatize an agricultural enterprise (for a song or even free of charge - for privatization investment coupons of employees of former state farms) in the context of a change in socio–economic formation within the framework of a large-scale national denationalization program [

49]. However, along with the position, they fully inherited and transferred to the new realities the managerial traits and style formed by the command-and-control economy and typical of Soviet managers: authoritarianism in decisions, inertia and rigidity of thinking, and hence the rejection of any ideas, but most importantly, the unpreparedness and inability to market transformations. Heredity is inherent in agribusiness in independent Kazakhstan, so children or relatives, heading an agricultural enterprise, as a rule, also retain the continuity of conservative views alien to the principles of a liberal economy. All of this is fueled by the ongoing government support for agriculture, as the industry continues to play a crucial economic and social role (11% of employment, 5% of GDP). Additionally, strengthening the country's food security is a significant reason for the extensive support provided to the agricultural sector. However, despite the significant investments in agricultural production, Kazakhstan remains highly dependent on imports for a range of livestock products (cheese, cottage cheese, and poultry meat) and plant-based products (sugar, sunflower oil, and cereals) [

50]. The main reasons are low labor productivity due to technological backwardness, a negligible share of innovation in the industry, and a lack of qualified personnel, which forces the government to regularly increase agricultural subsidies [

51], as was the case during the Soviet era, using the same oil revenues. However, these measures are palliative, not solving the problem but rather reinforcing the dependence on subsidies and creating serious corruption risks in the industry [

52]. By damping out negative processes and contributing huge amounts of money into the industry in the form of subsidies and grants, the government is supporting the structure of crops and livestock that is beneficial to it, while preserving and strengthening the Soviet-era regulatory system of government-farmer relations, which can be described as agrarian-conservative paternalism. Thanks to this, farmers have a guaranteed basic income based on the size of their farmland or livestock, and they don't have to engage in non-agricultural activities, diversify their income, or even increase the value added to their agricultural products. The issue of social capital is crucial for the development of agritourism and rural tourism for several reasons. Firstly, agritourism service providers are private enterprises, so their owners must have entrepreneurial skills. Secondly, modern tourists require more than just accommodation. They also want to participate in local attractions, such as bonfires or safe fun with animals. Uglis and Jęczmyk [

44] list the following characteristics that a person running an agritourism farm should have: diligence, self-confidence, commitment, and problem-solving skills.

If we disregard the conservatism of farmers' behavior described above and focus on the agrarian structure (

Table 5), it can be seen that it indicates moderate opportunities for the development of rural tourism in Northern Kazakhstan. It should be assumed that small farms in particular may be potentially interested in providing agritourism services. Of course, under certain conditions, also big farmers show increasing interest in agritourism because it diversifies income, strengthens branding, and uses their large assets effectively. However, interest varies, and some prefer to avoid the complexity and risk of mixing tourism with large-scale production. Therefore, concerning the situation in Kazakhstan, where large entities are encouraged by the government to produce food, it can be assumed that they are unlikely to be interested in diversifying their activities. Small farms, on the other hand, predominate in terms of numbers (75.8%), although they occupy only 21.0% of the UAA. This is not a major problem, because the provision of tourist services does not require large areas, but rather the aesthetics inside and attractions outside the farm. The structure of livestock farming also has the potential to support the development of agritourism. Animals such as pigs and poultry are kept almost entirely on large farms. Horses, which can be an attraction in themselves, are predominant on small farms.

4.4.2. The Reasons for the Community's Disinterest in Restructuring the Rural Economy

Despite the obvious interest in the sustainability of livelihoods, income diversification, transformation of a low-functioning economy and the development of its non-productive sector [

53], members of the rural community demonstrate minimal social activity and involvement in the work of local governments. Such alienation is largely due to the Soviet background of centralization of power and suppression of any kind of initiatives under authoritarian governance. Indirect, but in fact formal participation in government (through the election of deputies of district and regional executive authorities), the exclusion from the elections of the head of the local executive authority (akim), gave rise to the indifference of community members. Until recently, the appointment of the head of the community (rural district) took place directionally from the district center, with the approval of the regional leadership, and it was not always a member of this community; often, the decisive factor was membership in the ruling party (CPSU – Otan – Nur-Otan –Amanat). The direct election of the heads of rural districts (akims) was initiated by President K. Tokayev after his announced policy of liberalizing the political system and electoral legislation in order to develop local self-government [

54]. The program of direct elections of rural district mayors was launched in a pilot mode in 2021, and it was only in 2025 that it became widespread. However, even now, the akim is functionally limited in the institutional and financial tools for effective management and support of entrepreneurial initiatives of rural residents. His role as a manager is formalized and comes down to the enforcement of laws and regulations, the regulation of non-agricultural land relations within the boundaries of the village.

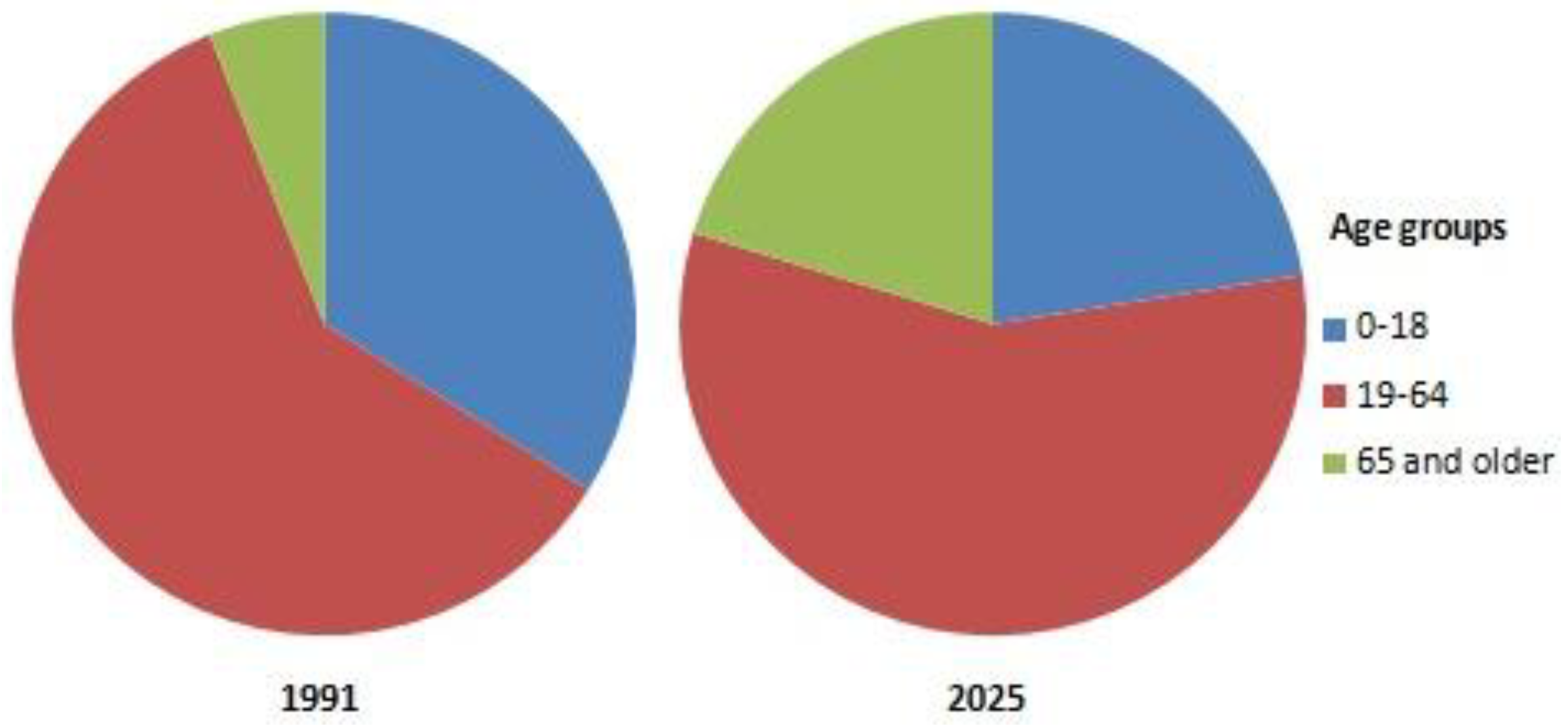

The social activity of the rural community has significantly degraded in the post-Soviet period, and the age structure of the rural population has undergone major changes due to mass migration (

Figure 1).

One of the most significant manifestations of rural depopulation was a three-fold increase in the number of elderly and senior citizens, while the proportion of young people (19-35 years old), the most proactive and creative part of the community, decreased by 60% in the economically active rural population. The Billeter Index [

55] of rural areas reached -38, and the average age of residents exceeded 42 years, compared to the national average of 32.3 years [

56]. The mass closure or reduction of schools, libraries, cultural houses, and cultural centres in small villages has led to the outflow of rural intellectuals, who are active members of the rural community. This has not only severely disrupted the direct communication of community members but has also undermined their already limited opportunities for personal and spiritual growth. The limited (seasonal) employment of hired workers in agricultural production, unemployment, and the isolation of household farming have also led to the disunity of rural community members and a decrease in emotional and personal contact, thereby narrowing the socio-cultural space of the village [

57]. In addition, the post-Soviet shift in the socio-economic formation has led to an increase in the isolation and segregation of the rural population based on ethnicity [

58]. This has resulted in a sharp decline in social capital, which is a crucial factor in rural development [

7,

59]. While in neighboring China, the solution to this problem has been elevated to the status of a national task and is the focus of a national program [

60], in Kazakhstan, it is currently being ignored by the government, and the aforementioned Concept [

61] is a set of non-functional declarative norms in the absence of bylaws. As a result, the community, which is de jure the most interested actor in diversifying income and increasing material well-being, is de facto socially disintegrated and demonstrates absolute indifference to the development of the diversified rural economy and its future. In many cases, the community itself creates narratives of rejection of socio-economic transformation.

4.5. Institutional Development of Rural Tourism in Kazakhstan

The main obstacle to the development of rural tourism in Kazakhstan is the lack of its institutionalization, which is based on the prohibition of private ownership of land and any other activities on agricultural land [

62] and its transfer to other categories [

61]. The formal presence of rural tourism (agritourism) in the list of priority areas of development from the previous State Program for the Development of the Tourism Industry [

63] has been smoothly transferred to the current Concept [

64], with only a brief mention of the potential of this segment of the service economy. Because of this, the activities of the Kazakhstan Association of Agri- and Rural Tourism are fundamentally different from those of similar foreign organizations and are symbolic in nature: instead of being a central coordinating structure for service providers, it acts as a consulting service, limited to providing information and educational services such as training seminars, workshops, and roundtables. Educational activities are, of course, valuable, especially in the context of the aforementioned social capital deficiencies in rural areas of Kazakhstan. Nevertheless, the activities of these organizations should be significantly expanded to include, for example, the promotion of specific areas both at home and abroad. Both the financial costs involved and the marketing skills required exceed the capabilities of individual tourism service providers. The official documents on the development of rural areas [

61] establish the agricultural profile of the rural economy, and the authorities see the increase in their contribution to the socio-economic development of Kazakhstan exclusively through the lens of agricultural intensification. Unlike the Eastern European countries that were satellites of the USSR and also developed under a centralized and planned economy, but successfully implemented the main EU norms in the rural economy services sector [

65], the processes of agricultural economy transformation in the post-Soviet space became more active much later, facing active resistance from agricultural lobbies [

66]. Despite this, a number of countries that have adopted the principle of developing rural tourism (agritourism) have accumulated significant experience in institutionalizing it, taking into account the best foreign practices of its positive impact on the improvement of rural areas (

Table 6).

Analyzing the above-mentioned institutionalization measures, the successful experience of two countries deserves special attention. The active development of rural tourism (agritourism) in Belarus is due to the highest level of urbanization in the CIS and Eastern Europe (82%) and the high-intensity agriculture with its agro-towns phenomenon [

76]. Their well-developed transport and social infrastructure was easily adapted to the needs of agritourism [

77], creating agro-ecological farms that are successfully developing around major cities and are popular not only in the country but also among residents of Russia's border regions. At the same time, the rapid development of rural tourism in Georgia has been made possible by the country's unique tourism and recreational resources, rich traditions of their use, and the synergy of efforts made by the government, urban entrepreneurs, local communities, and non-governmental associations, with the participation of European organizations under the Association Agreement between Georgia and the EU [

78]. The institutional framework regulates the activities of rural tourism businesses in order to stimulate non-agricultural initiatives by all actors. In order to institutionalize rural tourism in Kazakhstan, it is necessary to clarify its definition, as the current definition differs significantly from the one commonly accepted in foreign countries:

1. In legal acts [

61,

64] the term "rural tourism" is always used in conjunction with agritourism in the context of using agricultural assets in rural areas, although there are significant differences between them [

79,

80,

81]. At the same time, other important subtypes of rural tourism are overlooked, such as ethno-tourism, ecotourism, gastronomic tourism, and others. Thus, in the Concept for the Development of the Tourism Industry [

64], ecotourism is considered as an independent area, but only from the perspective of using the potential of specially protected natural areas in the context of environmental protection activities.

2. Rural tourism is positioned by domestic authorities and researchers as a soft power tool for popularizing the everyday life and traditions of the Kazakh village, rather than as a promising mechanism for diversifying the agricultural economy and increasing the income of rural communities. As a result, the economic aspect of rural tourism is not taken seriously.

Institutionalization based on the best practices of Western and CIS countries will help to establish rural tourism as a sustainable business with well-defined products, which can then be integrated into the Kazakhstani and international tourism landscape.

4.6. Determinants of the Unpopularity of Rural Tourism Among the Local Population in the Agrarian Regions of Kazakhstan

For the population of the NKR, the natural, economic, cultural and historical resources of rural areas do not represent any tourist and recreational value. This is due to historical experience, since the socio-economic difficulties of rural life have always negated the attractiveness of the natural and cultural sites of the place of residence. On the contrary, guest, cultural, and business trips to a city (district or regional centre) are invariably perceived not only as entertainment, but also as a form of recreation. The urban population of the region, since the 50s of the last century has overwhelmingly owned land plots with an area of 0.06 hectares. These plots, called dachas, were allocated free of charge by the state in the suburban area, as a rule, near picturesque places (rivers, lakes, birch spikes), for growing vegetables and berries. Subsequently, the owners built small houses for recreation and storage of gardening equipment, and the authorities supplied engineering networks and transport infrastructure. Some townspeople, nostalgic for their rural childhood, visit them not only on weekends and holidays, but also seasonally relocate there during the summer and autumn holidays. In addition to gardening, they also keep farm animals (most often rabbits and chickens). However, in recent decades, due to the increased rhythm of urban life, as well as the year-round availability of high-quality vegetables and fruits, there has been an intensive socio-economic transformation of rural farming. Plots are increasingly being used for the construction of houses directly for recreation and picnics, fruit trees are being planted instead of beds, using landscaping, flower beds, and lawns are being laid out [

82,

83], and barbecue areas are being equipped. The phenomenon of cottage farming, which has formed a suburban subculture characteristic only of the territory of the former USSR with its regional values and established practices, is unique primarily in that each citizen determines the nature of the use of cottages, building a balance of work and leisure. According to the interview results, respondents of retirement age visit dachas mainly to work on the site (90.1%), and some of them sell surplus products in urban markets or among friends (8.8%), representatives of the middle generation prefer to maintain a balance between work on the site and recreation (78.6%), while young people visit exclusively for picnics (94.4%), sometimes together with friends who do not have dachas (22.2%). Thus, the dacha phenomenon is increasingly moving away from its original purpose – gardening, turning into an affordable and high–quality alternative to rural recreation, using the main advantages - proximity to the city (up to 10 km), the availability of utilities and accessibility of natural sites.

Among the urban Kazakh community, the presence of dacha plots is extremely rare (0.75% of the respondents), but due to national traditions, it is common and therefore frequent to travel to ancestral villages (the place of birth of the traveller or their parents) to visit relatives, including distant ones. The purpose of these trips is to participate in numerous family events, most often rituals, such as celebrating the birth of a child, celebrating their coming of age, attending weddings, and participating in funerals, memorial services, and visits to the graves of deceased ancestors. Thus, such visits not only strengthen family ties and maintain the connection between urban Kazakhs and those who remain in the countryside but have also become an alternative to rural recreation.

Given the dominance of domestic tourism overall in Kazakhstan, it is likely that a non-negligible share of domestic travellers — especially those interested in nature, lower costs, or authentic rural experiences — choose rural/agrarian regions. However, due to the lack of consistent national data categorizing trips as “rural tourism,” it is impossible with publicly available sources to state what percentage of domestic or foreign tourists opt for rural/agrarian-region tourism specifically. Thus rural tourism can be described as emerging and an expanding segment, even if its precise share is unclear.

5. Conclusions

Unfortunately, there are currently no objective prerequisites for the development of rural tourism in Kazakhstan. The underdevelopment of rural tourism in agricultural areas is due to a combination of factors, including:

The state's lack of interest: rural tourism is not recognized as a form of non-agricultural economy in the strategic documents for the development of tourism and rural areas. The absolute investment unattractiveness of the rural services sector is exacerbated by the prohibition of private ownership of land and its use for non-agricultural purposes, as well as the prohibitively high interest rates on loans for small businesses (up to 38%). In contrast, basic agricultural production is supported by government incentives. In addition to affordable preferential loans (2.5% at the National Bank's base rate of 18%), there are also numerous subsidies for the purchase of agricultural machinery, pedigree livestock, mineral fertilizers and pesticides, the production of technical crops, milk, meat, and others.

The lack of motivation among farmers: large agricultural holdings, which own ¾ of the cultivated land, are focused on producing export crops such as wheat and oilseeds, as well as profitable (in our case, highly subsidized) dairy farming. At the same time, small-scale farms, which are fragmented, low-budget, and critically dependent on subsidies, are unable to become the founders of promising rural tourism projects due to their lack of resources and personnel for developing the tourism and hospitality economy. In addition, in both cases, the conservatism of farmers, who perceive the rural economy as exclusively agrarian and perform the strategically important function of "feeding" the country, plays an extremely important role. Thus, the agricultural model of the economy and labour market in rural areas, which has persisted since Soviet times, is explained by the coincidence of interests between the state and farmers, as the stable subsidies are fully satisfactory for both forms of production organization, despite the polarity of causal relationships.

Lack of demand among the population: the region is one of the most "rural" in Kazakhstan and the least urbanised in Northern Kazakhstan (50%). Taking into account small towns (up to 10,000 people), whose population lives in the private sector and mostly keeps a household farm, the circle of potential travellers is narrowed to 40% (residents of the regional centre). However, they also own large numbers of dacha plots, which are increasingly used for recreation in the countryside. Given the negative experiences of living in the countryside [

84] and/or subsequent visits to the countryside, which have interfered with many people's nostalgia and idealization of their childhood there, as well as the persistent negative stereotypes of the countryside that have been formed in society, they completely reject the natural, agricultural, and cultural-historical resources of rural areas as recreational resources.

We come to the conclusion that in the current conditions of the lack of institutional regulation and support for the rural services sector, and, on the contrary, the ever-increasing subsidization of agricultural production, neither the government, nor farmers, nor rural communities are interested in a multi-sectoral economy in agricultural areas.

The monopolization of Kazakhstan's agricultural market, characterized by an excessive concentration of land and resources in the hands of large agricultural holdings, has led to unfair competition due to limited access of small farms to agricultural land (primarily arable land) and new technologies. This has resulted in a distorted rural labour market, leading to a slowdown in average wages, a decrease in income and quality of life, and, consequently, a migration of skilled workers to urban areas.

The most preferred for the domestic consumer is a combined tourist product (tour) with a predominance of natural and socio-cultural, and to a lesser extent, agricultural facilities. Rural tourism implies short-term visits, which makes it a priority for its development, given the main preferences of Kazakhstani travellers [

85], transport accessibility, and glamping in suburban areas. Inspired by the best practices in rural tourism development and taking into account the specificities of agricultural production in Kazakhstan, the potential actors in the rural tourism business in agricultural regions are small-scale farmers who are most interested in diversifying and increasing both their own income and that of their rural community members. The interest of small farmers in rural tourism is largely due to their understanding of the looming threat of labour resource loss and the risk of changes (reductions) in agricultural subsidies.

Based on the above, the following measures should be taken to develop rural tourism in Kazakhstan:

1. Institutionalization of rural tourism as a form of rural economy, taking into account the best practices of foreign countries;

2. Touristification of suburban agricultural areas with maximum natural, economic, and social potential, based on public-private partnerships, with the aim of piloting the restructuring of the rural economy, increasing the role of the service sector, and subsequently branding the established tourist destinations;

3. Financial support by the government of initiatives of non-governmental organizations and rural communities in the form of grants, subsidizing farmers' interest rates for rural tourism projects, as well as partial reimbursement of costs in proportion to the volume of services provided;

4. Restart of the Association of Rural Tourism (Agritourism), de facto coordinating the interaction of all stakeholders in the field of tourism and the economy of rural hospitality, as an aggregator of training and professional development in the planning, administration, and marketing of rural tourism business projects at the regional and national levels.

5. Conducting a detailed inventory of natural and cultural attractions in Northern Kazakhstan, including mainly the location of forests, lakes, open areas (valuable for horse riding tourism) and historical monuments. It is important to find attractions that are unique and not found in other places.

6. Long-term activities aimed at shaping entrepreneurial attitudes among the population in rural areas, as well as advisory services on running one's own business, marketing and accounting.

7. Change in agricultural policy. Moving away from unilateral subsidies for production towards multifunctional rural development. Public support for non-agricultural economic activity (including tourism) is important, particularly because of the lack of capital among the rural population.

8. Promotion of rural areas (and their natural and cultural attractions) of Northern Kazakhstan in other regions of the country (especially in large cities such as Astana and Almaty) and abroad. The reluctance of the urban population of Northern Kazakhstan to spend their holidays in the countryside, resulting from recent migration processes, as mentioned in the study, makes it necessary to look for potential tourists in other places.

In conclusion, measures should be taken both to increase the supply of tourist services in rural areas and to create demand for them. However, it should be realised that tourist activity in the countryside will not be an antidote to current shortages everywhere, but only where there are suitable attractions.

The implementation of these measures will not only help to achieve the recovery and sustainability of the rural economy through the monetization of unique natural, agricultural, and socio-economic assets, but also serve as an eventual tool for reframing rural areas.

It should also be noted that these activities, which aim not only to develop rural tourism but also to promote the multifunctional development of rural areas, are essential. Due to the ongoing process of modernization, contemporary agriculture requires increasingly fewer labour resources. This is particularly evident in Kazakhstan, where large farms dominate. In order to maintain the vitality of rural areas, it is therefore necessary to take measures to create non-agricultural workplaces, but also to take care of infrastructure, aesthetics and social capital. The last point is especially important because of the need to overcome the passive attitude that comes from the still-present post-Soviet legacy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.P., A.S. (Arkadiusz Sadowski) and L.P.-S.; Methodology, S.P., A.S. (Arkadiusz Sadowski) and S.G.; Validation, S.S., M.U. and D.W.; Formal analysis, S.P., L.P.-S and D.W.; Investigation, A.S. (Arkadiusz Sadowski); Resources, S.P., S.S. and A.S. (Arkadiusz Sadowski); Data curation, A.S. (Armanay Savanchiyeva), D.W. and S.G.; Writing—original draft, A.S. (Armanay Savanchiyeva) and M.U.; Writing—review and editing, A.S. (Armanay Savanchiyeva),, M.U., and S.G.; Visualization, S.P., S.S. and S.G.; Supervision, S.P. and L.P.-S.; Project administration, A.S. (Arkadiusz Sadowski); Funding acquisition, L.P.-S.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wilson, S.; Fesenmaier, D.R.; Fesenmaier, J.; Van Es, J.C. Factors for success in rural tourism development, Journal of Tourism Research, 2001, 40(2), 132-138. [CrossRef]

- Kataya, A. The Impact of Rural Tourism on the Development of Regional Communities. Journal of Eastern Europe Research in Business and Economics, 2021, 652463. [CrossRef]

- Chiran, A.; Jităreanu, A.F.; Gîndu, E.; Ciornei, L. Development of rural tourism and agrotourism in some european countries. Lucrări Științifice Management Agricol, 2016, 18, 225.

- Lane, B.; Kastenholz, E. Rural tourism: the evolution of practice and research approaches – towards a new generation concept? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 2015, 23(8–9), 1133–1156. [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B. Rural tourism and sustainable rural tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1994, 2(1–2), 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Vaishar, A.; Šťastná, M. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on rural tourism in Czechia preliminary considerations. Curr. Issues Tour., 2022, 25(2), 187-191. [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Liu, L. Social capital for rural revitalization in China: A critical evaluation on the government’s new countryside programme in Chengdu. Land Use Policy, 2020, 91, 104268. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Yang, R.X.; Chen, M.H.; Su, C.H.; Zhi, Y.; Xi, J.C. Effects of rural revitalization on rural tourism. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag., 2021, 47, 35–45. [CrossRef]

- Dłużewska, A.; Giampiccoli, A.; Mergalieva, L.; Yegzalieyeva, A.; Sharafuidinova, A. Aims & reviews: Tourism Development in Kazakhstan – Issues and Ways Forward. Annales Universitatis Marie Curie Skłodowska Lublin – Polonia, 2022, 77, 55-71, section B. [CrossRef]

- Iskakova, K.; Bayandinova, S.; Aliyeva, Z.; Aktymbayeva, A.; Baiburiyev, R. (eds.). Ecological Tourism in the Republic of Kazakhstan. Springer, 2021.

- Pashkov, S.V.; Mazhitova, G.Z. Agritourism as an Alternative Form of Development of Rural Area. Bull. Irkutsk St. Univ. Ser. Earth Sci,, 2021, 36, 75-87. (in Russian). [CrossRef]

- Seken, A.; Duissembayev, A.; Tleubayeva, A.; Akimov, Z.; Konurbaeva, Z.; Suieubayeva, S. Modern potential of rural tourism development in Kazakhstan. J. of Environ. Manag. and Tour., 2019, 10, 1211–1223. [CrossRef]

- Tleubayeva, A. Ethno-Cultural Factors Influencing the Development of Rural Tourism in Kazakhstan. J. Environ. Manag. Tour., 2019, 04(36), 772-787. [CrossRef]

- Nurasheva, K.K.; Ageleuova A.T.; Abenova, E.A. Creation of agro-tourism cluster in Kazakhstan as a new trend in development of domestic tourism. Central Asian Economic Review, 2024, 6, 110-126. [CrossRef]

- Saparov, K.; Omirzakova, M.; Yeginbayeva, A.; Sergeyeva, A.; Saginov, K.; Askarova, G. Assessment for the Sustainable Development of Components of the Tourism and Recreational Potential of Rural Areas of the Aktobe Oblast of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Sustainability, 2024, 16(9), 3838. [CrossRef]

- The development strategy of JSC NC Kazakh Tourism for 2022-2031 was approved by the Decree of the Government of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Available online: https://qaztourism.kz/en/about-company/our-work/mission/ (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- UNESCO. World Heritage Centre. Petroglyphs within the Archaeological Landscape of Tanbaly. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1145/ (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Mazhitova, G.Z.; Pashkov, S.V.; Wendt J.A. Assessment of Landscape-Recreational Capacity of North Kazakhstan Region. GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites, 2018, 23(3), 731–737. [CrossRef]

- Mamraeva, D. G.; Borbasova, Z. N.; Tashenova, L. V. World experience in the development of rural tourism. Problems of AgriMarket, 2019, 2, 108–115. (in Russian).

- Aimurzina, B.; Yertargyn, S.; Nurmaganbetova, A.; Narynbayeva, A.; Abdramanova, G.; Mizambekova, Z. State Policy Regulations of Agriculture for Sustainable Development of Rural Tourism. J. of Envir. Manag. and Tour., 2023, 4(68), 2004-2014. [CrossRef]

- Tleubayeva, A. Rural tourism as one of the priority factors for sustainable development of rural territories in Kazakhstan. J. Environ. Manag. Tour., 2018, 9, 1312–1326. [CrossRef]

- Omirzakova, M.; Wendt, J.A. Transport as a factor in the development of rural tourism in Aktobe region, Republic of Kazakhstan. Geojournal of Tourism and Geosites, 2025, 59(2), 952–964. [CrossRef]

- Tleuberdinova, A.; Kulik, X. V.; Pratt, S.; Kulik, V. B. Exploring the Resource Potential for the Development of Ecological Tourism in Rural Areas: the Case of Kazakhstan. Tour. Rev. Inter., 2022, 26(4), 321-336. [CrossRef]

- Tleubayeva, А.; Rsaldin, Y.; Zhakupov, А. Rural tourism in the Republic of Kazakhstan: the use of digital. Problems of AgriMarket, 2024, 4, 55-68. [CrossRef]

- Uglis, J.; Jęczmyk, A.; Wojcieszak-Zbierska A. Consumer expectations of agritourism offerings. Annals PAAAE, 2023, XXV, 4, 422-437. [CrossRef]

- Uglis, J. Oczekiwania turystów względem oferty agroturystycznej (Tourists' expectations regarding agritourism offers). Studia Oeconomica Posnaniensia, 2018, 6(10), 137-148. [CrossRef]

- Ostapenko, I. I. Agrotourism: foreign experience and prospects. Actual problems of humanities and natural sciences, 2011, 33, 289-291. (In Russian).

- Saxena, G.; Clark, G.; Oliver, T.; Ilbery, B. Conceptualizing Integrated Rural Tourism. Tour. Geogr., 2007, 9, 347–370.

- Bureau of National Statistics of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Statistics of Bureau of National Statistics of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Available online: https://stat.gov.kz/ru/ (accessed on 01 December 2025).

- Kuralbayev, A.; Abishov, N.; Abishova, A.; Urazbayeva, G. The measurement of the spiritual tourism in regions of south Kazakhstan. European Research Studies Journal, 2017, 20(3A), 115-133.

- Omarkozhayeva, A.N.; Zhunusova, А.А.; Tercan, T. Development of Tourism Services through Sacred Sites in Kazakhstan. Migration Letters, 2023, S6(20), 657-669.

- Kazakhstan is turning a Soviet-era cosmodrome into a tourist center. Available online: https://ru.euronews.com/culture/2025/09/10/kazahstan-prevrashaet-kosmodrom-sovetskoj-epohi-v-turisticheskij-centr (accessed on 15 October 2025). (In Russian).

- How tourism is developing in Aralsk and why the first Geopark in Central Asia, the Aral, was opened at the bottom of the lake. Available online: https://www.zakon.kz/stati/6450626-kak-v-aralske-razvivayut-turizm-i-zachem-na-dne-ozera-otkryli-pervyy-v-tsentralnoy-azii-Geopark-Aral.html (accessed on 15 October 2025). (In Russian).

- Ismailova, R.A.; Shainazarova, A. The influence of gambling on the development of the tourism industry: the experience of China and Kazakhstan. In Proceedings of the International Research Conference "State of the Future: New Technologies and Public Administration", 2019, 41-48. (In Russian).

- Kazakhstanis travel abroad more often than they do within the country. Available online: https://ranking.kz/digest/kazahstantsy-chasche-vyezzhayut-na-otdyh-za-rubezh-chem-otdyhayut-vnutri-strany.html (accessed on 05 December 2025). (In Russian).

- Pianciola, N. The collectivization famine in Kazakhstan, 1931–1933. Harvard Ukrainian Studies, 2001, 25(3/4), 237-251.

- Ivnitskiy, N.A. The famine of 1932–1933 in the USSR: Ukraine, Kazakhstan, the North Caucasus, the Volga region, the Central Black Earth Region, Western Siberia, the Urals. Sobranie Publ., Moscow, Russia, 2009. (In Russian).

- Wyszyński, W. Deportacje Ludności Polskiej do Kazachstanu w 1936 Roku; Opinie i Ekspertyzy, Kancelaria Senatu RP: Warsaw, Poland, 2016.

- Mazhitova, Z.; Zhalmurzina, A.; Kolganatova, S.; Orazbakov, A.; Satbai, T. Environmental consequences of Khrushchev's Virgin Land Campaign in Kazakhstan (1950s−1960s). E3S Web of Conferences, 2021, 258, 05036, 1–12.

- Pashkov, S.V. Evolution of Virgin Agriculture in Northern Kazakhstan: Determinants of Regional Development. Bull. Irkutsk St. Univ. Ser. Earth Sci., 2022, 42, 68–89. (in Russian). [CrossRef]

- Buktugutova, R.S.; Zhanaeva, G.K. Demographic consequences of the development of virgin and fallow lands in Kazakhstan (some aspects). Science & reality, 2021, 2(6), 154-157. (in Russian).

- On the suspension of certain provisions of the Land Code of the Republic of Kazakhstan and the enactment of the Law of the Republic of Kazakhstan dated November 2, 2015 "On Amendments and Additions to the Land Code of the Republic of Kazakhstan". The Law of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Available online: https://adilet.zan.kz/rus/docs/Z1600000005 (accessed on 15 October 2025). (In Russian).

- Big purge: 45 villages to be abolished in North Kazakhstan region at once. (2024). Available online: https://pkzsk.info/bolshaya-chistka-srazu-45-sjol-uprazdnyat-v-severo-kazakhstanskojj-oblasti/ (accessed on 15 October 2025). (In Russian).

- Uglis, J.; Jęczmyk, A. Agritourism as a chance for rural areas boom. Annals PAAAE, 2009, XI, 4, 341-346.

- How different is life in cities and villages in Kazakhstan. Available online: https://news.mail.ru/society/66207625/ (accessed on 15 October 2025). (In Russian).

- Kosmaczewska, J. Social and economic development of a rural commune versus the performance of tourist functions – methodological concept of empirical research. Folia Pomer. Univ. Technol. Stetin – Oeconomica, 2011, 288(64), 103-112.

- Przezbórska-Skobiej., L. Uwarunkowania rozwoju rynku turystyki wiejskiej w Polsce [Conditions for the development of the rural tourism market in Poland]. Journal of Tourism and Regional Development, 2015, 3, 101-115. (In Polish).

- Rothacher, A. Post-Soviet industrial policy: From the red directors to the new state oligarchs. In: Putinomics. Cham, Switzerland. Springer Nature. Switzerland, 2021, 43–104.

- On the National Program of Denationalization and Privatization in the Republic of Kazakhstan for 1993-1995 (Stage II). Available online: https://zakon.uchet.kz/rus/history/U930001135_/18.06.2009 (accessed on 15 October 2025). (In Russian).

- Food addiction: how imports affect prices in Kazakhstan. Available online: https://dknews.kz/ru/ekonomika/357983-prodovolstvennaya-zavisimost-kak-import-vliyaet-na (accessed on 15 October 2025). (In Russian).

- Food security was discussed at parliamentary hearings. Available online: https://mtrk.kz/ru/2024/12/06/obespechenie-prodovolstvennoy-bezop/ (accessed on 15 October 2025). (In Russian).

- Tampering of 2 million head of cattle and 3 million tons of milk were found in Kazakhstan. Available online: https://eldala.kz/novosti/zhivotnovodstvo/19510-pripiski-2-mln-golov-skota-i-3-mln-tonn-moloka-vyyavili-v-kazahstane (accessed on 15 October 2025). (In Russian).

- Liu, Y.L.; Chiang, J.T.; Ko, P.F. The benefits of tourism for rural community development. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun, 2023, 10, 137.

- On amendments and additions to certain legislative acts of the Republic of Kazakhstan on the implementation of certain instructions of the Head of State. The Law of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Available online: https://adilet.zan.kz/rus/docs/Z2200000177 (accessed on 15 October 2025). (In Russian).

- Billeter, E.P. Eine Masszahl zur Beurteilung der Altersversteilung einer Bevölkerung. Swiss Journal of Economics and Statistics, 1954, 90(IV), 496-505. (In German).

- Ilyasova, G.S.; Sadykov, T.S. Сhanges in the Age Structure of the Northern Region of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Proc. of the Komi Sci. Centre, Ural Branch, RAS, 2022, 1(53), 98-104. (In Russian). [CrossRef]

- Yeszhanova, Z.; Abdykadyr, T. Сomparative Analysis of Socio-Cultural Environment Development of Kazakhstan’s Regions. Eurasian Journal of Economic and Business Studies, 2024, 68(2), 20–34. [CrossRef]

- Berezina, G.M. The genetic structure of rural populations in Kazakhstan. Medical Genetics, 2005, 2(4). 50-55. (In Russian).

- Bulhairova, Zh.S.; Balkibayeva, A.M.; Aydinov, Z.P. Human Capital in Agriculture of Kazakhstan: Contemporary Trends. Problems of ArgiMarket, 2017, 4, 180-184.

- Liu, C.Y.; Doub, X.T.; Lia, J.F.; Caib, L.A. Analyzing government role in rural tourism development: an empirical investigation from China. J. Rural Stud., 2020, 79, 177–188. [CrossRef]

- On approval of the Concept of Rural Development of the Republic of Kazakhstan for 2023-2027. Resolution of the Government of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Available online: https://adilet.zan.kz/rus/docs/P2300000270 (accessed on 15 October 2025). (In Russian).

- Land Code of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Available online: https://adilet.zan.kz/rus/docs/K030000442 (accessed on 15 October 2025). (In Russian).

- On approval of the State Program for the development of the tourism industry of the Republic of Kazakhstan for 2019-2025. Decree of the Government of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Available online: https://adilet.zan.kz/rus/docs/P1900000360 (accessed on 15 October 2025). (In Russian).

- On approval of the Concept of development of the tourism industry of the Republic of Kazakhstan for 2023-2029. Resolution of the Government of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Available online: https://adilet.zan.kz/rus/docs/P2300000262 (accessed on 15 October 2025). (In Russian).

- Ibanescu, B.C.; Stoleriu, O.M.; Munteanu, A.; Iaţu, C. The impact of tourism on sustainable development of rural areas: Evidence from Romania. Sustainability, 10(10), 2018, 3529. [CrossRef]

- Visser, O.; Mamonova, N.; Spoor, M. Oligarchs, megafarms and land reserves: Understanding land grabbing in Russia. J. Peasant Stud., 2012, 39, 899–931.

- A program to promote rural tourism has been launched in Armenia. Available online: https://www.ekhokavkaza.com/a/27972178.html (accessed on 15 October 2025). (In Russian).

- About personal farming. The Law of Ukraine. Available online: https://online.zakon.kz/Document/?doc_id=31403893 (accessed on 15 October 2025). (In Russian).

- About the development of agriecotourism. Decree of the President of the Republic of Belarus. Available online: https://president.gov.by/ru/documents/ukaz-no-351-ot-4-oktyabrya-2022-g (accessed on 15 October 2025). (In Russian).

- About the organization and implementation of tourism activities in the Republic of Moldova. Law of the Republic of Moldova. Available online: https://base.spinform.ru/show_doc.fwx?rgn=18582# (accessed on 15 October 2025). (In Russian).

- According to the Government's strategy, by 2030 Georgia will become the leading ecotourism country in the Caucasus region. Available online: https://1tv.ge/lang/ru/news/soglasno-strategii-pravitelstva-k-2030-godu-gruzija-stanet-vedushhej-stranoj-jekoturizma-v-kavkazskom-regione/ (accessed on 15 October 2025). (In Russian).

- On amendments to Article 19 of the Federal Law "On Peasant (Farmer) Farming" and the Federal Law "On the Development of Agriculture". Federal Law. Available online: https://rg.ru/documents/2024/06/25/160fz.html (accessed on 15 October 2025). (In Russian).

- The State program of the Kyrgyz Republic "Development of tourism in rural areas until 2010". Available online: https://online.zakon.kz/Document/?doc_id=30301806&pos=6;-108#pos=6;-108 (accessed on 15 October 2025). (In Russian).

- The state will support the development of agritourism and ecotourism in the regions of Georgia. Available online: https://spress.ge/57729/ (accessed on 15 October 2025). (In Russian).

- The Strategy of the Main Directions Ensuring Economic Development in Agricultural Sector of the Republic of Armenia for 2020-2030”. Available online: https://mineconomy.am/en/page/1467# (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Slivinskaya, L. Rural development in Belarus: the “agrogrodok”: between rural and urban? Web of Conf., 2019, 63, 05001. [CrossRef]

- Klitsounova, V. Networking, Clustering, and Creativity as a Tool for Tourism Development in Rural Areas of Belarus. In: Tourism Development in Post-Soviet Nations, Palgrave Macmillan, Cham., 2020, 155-173. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007%2F978-3-030-30715-8.

- Khartishvili, L.; Muhar, A.; Dax, T.; Khelashvili, I. Rural Tourism in Georgia in Transition: Challenges for Regional Sustainability. Sustainability, 2019, 11, 410. [CrossRef]

- Fleischer A.; Tchetchik A. Does rural tourism benefit from agriculture? Tour. Manag., 2005, 4(26), 493-501. [CrossRef]

- Lane, B. What is rural tourism? J. of Sustain. Tour., 1994, 2(1–2), 7–21. [CrossRef]

- Oppermann, M. Rural tourism in Southern Germany. Annals of Tourism Research, 1996, 1(23), 86-102. [CrossRef]

- Lovell, S. Summerfolk. A History of the Dacha. 1710-2000. Publishing house DNK: Saint Petersburg, Russia, 2008. [in Russian).

- Potapchuk, E. Yu. The meaning of luck in the life of a modern citizen. International Scientific Research Journal, 2021, 2-3(104), 152–158. (in Russian). [CrossRef]

- Wojciechowska, J.; Uaisova, A. Możliwości rozwoju agroturystyki w Kazachstanie (Opportunities for the development of agritourism in Kazakhstan). Warsztaty z Geografii Turyzmu, 2014, 5, 313–327. (In Polish).

- Shaken, A.; Mika, M.; Plokhikh, R.V. Exploring the social interest in agritourism among the urban population of Kazakhstan. Misc. Geogr., 2020, 24, 16–23. 10.2478/mgrsd-2019-0026.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).