1. Introduction

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development established gender equality and women's empowerment (SDG 5) as both a fundamental human right and an essential enabler of progress across all 17 Sustainable Development Goals [

1,

2]. Women's empowerment directly influences poverty reduction (SDG 1), health outcomes (SDG 3), quality education (SDG 4), economic growth (SDG 8), and climate action (SDG 13)[

3,

4,

5]. Recent research demonstrates that countries with higher gender equality consistently outperform on multiple sustainability indicators [

6,

7].

In Sub-Saharan Africa, women's empowerment presents both extraordinary opportunity and persistent challenge. African women comprise the majority of smallholder farmers, informal sector workers, and community leaders, positioning them as critical agents for sustainable development [

8,

9]. Yet structural barriers, including discriminatory legal frameworks, limited access to education and healthcare, economic marginalization, and political underrepresentation—constrain women's capacity to contribute fully to development processes [

10,

11]. The COVID-19 pandemic further exacerbated these inequalities, reversing decades of progress across the continent [

12,

13].

Nigeria, as Africa's most populous nation (over 220 million people) and largest economy, occupies a pivotal position in continental development trajectories [

14]. Yet Nigeria exhibits one of Africa's poorest women's empowerment records, ranking 99th globally out of 114 countries and 18th out of 28 Sub-Saharan African nations on the 2022 Women's Empowerment Index [

14]. Nigerian women hold only 4.5% of parliamentary seats—among the world's lowest rates—less than 15% of corporate board positions, and fewer than 8% of university leadership roles [

15,

16]. Educational gender gaps persist, particularly in northern regions where girls' primary school enrollment lags boys' by over 20 percentage points [

17,

18]. Women face 30-40% wage gaps, limited access to credit and land, and disproportionate responsibility for unpaid care work [

19,

20].

This systematic marginalization represents not merely a rights violation but a critical impediment to achieving Nigeria's Sustainable Development Goals [

21,

22]. With over 60% of Nigeria's population under age 25, decisions made today about girls' education and women's participation will shape national development trajectories for decades [

23].

Despite growing recognition of women's empowerment as a development priority, African policymakers often lack actionable, evidence-based guidance for accelerating progress [

24,

25]. Existing research has documented gender inequalities through qualitative case studies and critiqued policy implementation gaps [

26,

27,

28]. However, systematic comparative analysis employing predictive modeling to forecast realistic empowerment trajectories and identify high-leverage interventions remains limited [

29,

30].

Recent studies emphasize the need for data-driven approaches to sustainable development planning, utilizing machine learning and predictive analytics to identify intervention priorities and forecast policy impacts [

29,

30,

31]. Machine learning offers particular advantages: pattern recognition across large datasets reveals relationships not apparent from traditional methods, clustering algorithms identify peer groups for South-South learning, and predictive models enable scenario analysis [

32,

33,

34]. Yet applications of machine learning to gender empowerment in African contexts remain nascent [

35,

36].

This study addresses these gaps by applying machine learning to forecast women's empowerment trajectories across 114 countries, with particular focus on identifying evidence-based pathways for Nigeria's advancement toward SDG 5 targets. Our forecasting approach integrates K-means clustering for peer group identification, linear regression for quantifying determinants of empowerment, and scenario modeling for projecting impacts of alternative policy approaches. By grounding projections in actual peer country achievements rather than theoretical possibilities, we provide policymakers with realistic, time-bound benchmarks for accelerating progress.

Research Objectives:

Forecast global and regional patterns in women's empowerment, quantifying the strength of relationships between gender parity and empowerment outcomes

Benchmark Nigeria's empowerment performance comparatively within Africa and globally

Identify African peer countries that have achieved superior empowerment outcomes through deliberate policy interventions

Generate evidence-based forecasts of Nigeria's potential empowerment improvements under alternative policy scenarios aligned with SDG planning horizons (2030, 2035, 2040)

The study makes several contributions.

Methodologically, it demonstrates how accessible machine-learning techniques can enhance comparative policy analysis for SDG monitoring in African contexts [

37,

38].

Empirically, it provides comprehensive benchmarking of Nigeria within global and regional contexts.

Theoretically, it validates gender parity as a universal predictor of empowerment outcomes, with gender parity explaining 70.5% of variance globally [

39,

40].

For policy, it generates evidence-based forecasts with specific targets, timelines, and intervention packages grounded in African peer achievements [

41].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

This study draws on the 2022 Women's Empowerment Index (WEI) dataset compiled by the United Nations Development Programme, covering 114 countries across six global regions [

14,

42]. The WEI tracks progress toward SDG 5 by aggregating indicators across four domains: political participation and decision-making (SDG 5.5), economic opportunity and participation (SDG 5.a, 5.4), educational attainment (SDG 4.5), and health and wellbeing (SDG 3.7, 5.6). Scores range from 0 (lowest empowerment) to 1 (highest empowerment). The 2022 global distribution spans from 0.141 (Yemen) to 0.828 (Sweden), with mean 0.607, median 0.583, and standard deviation 0.152.

The dataset also includes the Global Gender Parity Index (GGPI), which measures women's representation relative to men in political, economic, and educational spheres on a 0–1 scale [

43]. Additional contextual variables comprise Human Development Index categories [

42], SDG regional groupings, and World Bank income classifications.

2.2. Analytical Approach

The analysis followed a four-stage empirical framework designed to provide comprehensive insight into Nigeria's empowerment position and potential improvement pathways. First, descriptive statistics were used to summarize global, regional, and country-level empowerment patterns, establishing baseline comparisons. Second, K-means clustering was applied to group countries with similar empowerment profiles, enabling peer comparison beyond conventional income-based classifications [

37,

44]. This unsupervised machine-learning technique partitions countries into homogeneous groups based on their empowerment characteristics, revealing natural groupings that may not align with traditional regional or economic categories. Prior to clustering, WEI and GGPI values were standardized using z-score normalization, and the optimal number of clusters was identified using the elbow method to balance model parsimony with explanatory power.

Third, a linear regression model was employed to quantify the relationship between gender parity and women's empowerment:

where β₀ represents the intercept, β₁ captures the marginal effect of gender parity on empowerment outcomes, and ε denotes the error term. Parameters were estimated using ordinary least squares regression. Model performance was assessed using standard goodness-of-fit measures, including R² (proportion of variance explained), root mean squared error (RMSE) for prediction accuracy, and 10-fold cross-validation to evaluate model stability [

38]. The linear specification prioritizes interpretability for policy communication—each 0.1-point increase in GGPI predicts an 8.8-point increase in WEI—while providing robust predictions across the observed range of values.

Finally, scenario-based forecasting was conducted to project Nigeria's potential empowerment trajectories under alternative policy approaches. Rather than theoretical projections, scenarios were grounded in empirically observed achievements of African peer countries—Ghana, Kenya, and Rwanda—which represent education-focused, multi-sectoral, and transformative governance pathways, respectively. Each scenario specifies: (1) target GGPI levels based on actual peer achievement, (2) projected WEI derived from the validated regression model with 95% confidence intervals, (3) realistic implementation timelines (2030, 2035, 2040) aligned with SDG planning horizons, and (4) key policy interventions synthesized from documented peer experiences. This approach provides policymakers with actionable, evidence-based benchmarks grounded in demonstrated feasibility rather than aspirational possibilities.

2.3. Analytical Implementation

The analytical procedures were implemented using established statistical and machine-learning techniques commonly applied in comparative development research. All analyses were conducted using Python 3.x with scikit-learn for machine learning algorithms, pandas for data manipulation, and standard scientific computing libraries [

45]. The focus of the implementation was on ensuring transparency, replicability, and interpretability of results for policy-relevant analysis, rather than algorithmic complexity. The complete analytical workflow follows reproducible research principles, enabling validation and extension by other researchers.

2.4. Limitations

This study has several limitations that warrant acknowledgment. The use of cross-sectional data from 2022 restricts causal inference and limits analysis of temporal dynamics and long-term trajectories [

46]. Country-level indicators may mask substantial subnational inequalities, particularly relevant in the Nigerian context given documented north-south disparities in educational access, economic opportunity, and cultural norms. As composite measures, empowerment indices are subject to methodological choices regarding indicator selection, weighting schemes, and aggregation procedures that can influence country rankings and comparisons. In addition, scenario projections assume that Nigeria can adapt peer-country pathways despite unique contextual factors including political economy dynamics, institutional capacity constraints, cultural specificities, and resource availability. While the linear model prioritizes interpretability and provides robust predictions across observed ranges, it may not fully capture non-linear relationships, threshold effects, or interactive dynamics between different dimensions of empowerment. Nonetheless, the combined analytical approach—integrating descriptive statistics, machine learning clustering, regression modeling, and scenario analysis—provides a robust empirical basis for comparative assessment and policy-oriented insight into Nigeria's empowerment challenges and opportunities.

3. Results

3.1. Global Patterns: Gender Parity as Universal Predictor

Analysis of 114 countries reveals systematic variation in women's empowerment outcomes closely linked to broader sustainable development indicators. Regional averages range from Europe/Northern America (0.739) to Central/Southern Asia (0.487), reflecting substantial differences in economic development, governance quality, educational systems, cultural norms regarding women's roles, and explicit policy commitments to gender equality as a sustainable development priority (

Figure 1).

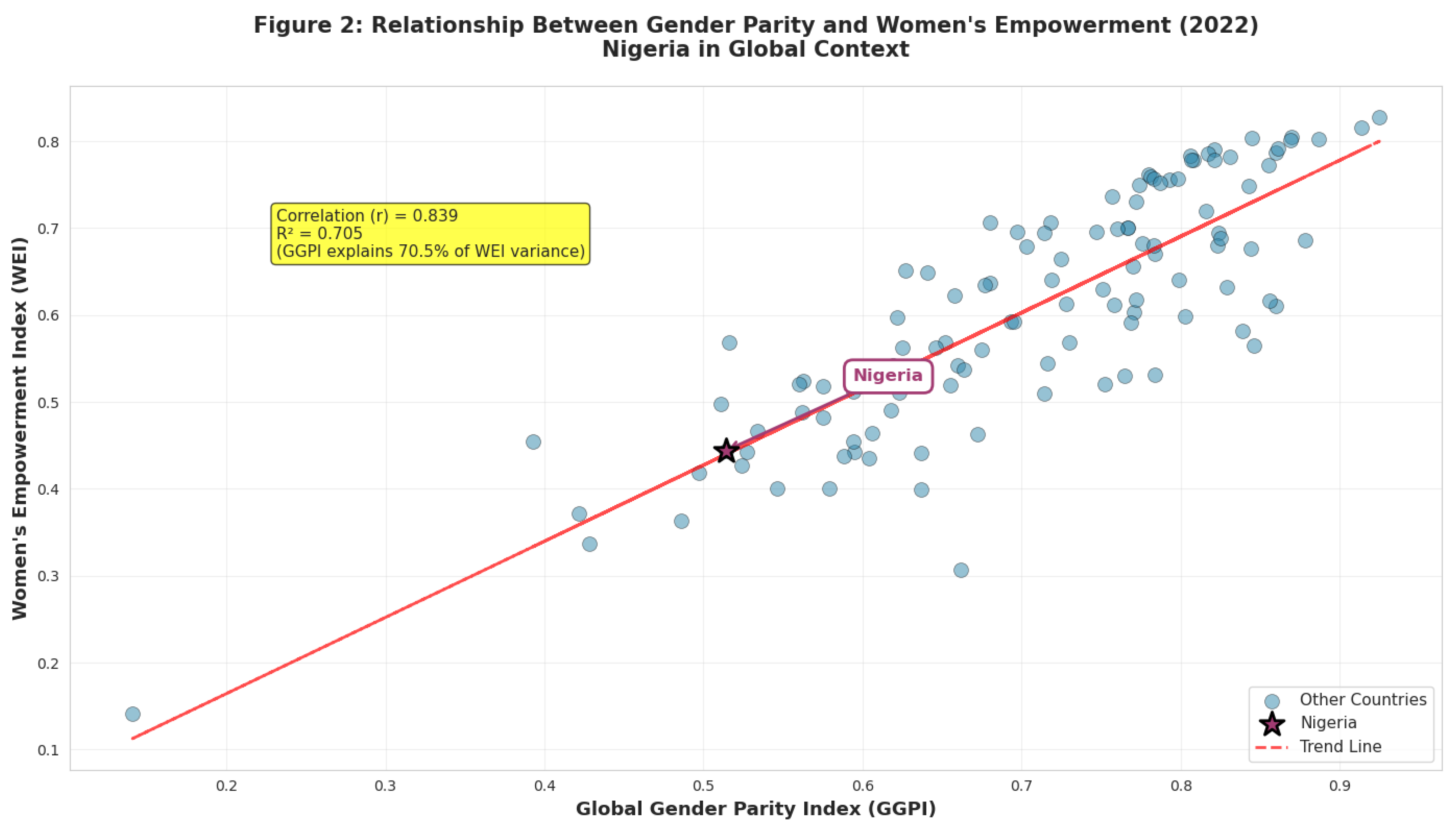

Examining the GGPI-WEI relationship reveals strong positive correlation: r = 0.839 (p < 0.001), with gender parity explaining 70.5% of variance in empowerment (R² = 0.705). This remarkably strong relationship suggests gender parity functions as a universal predictor of empowerment.

Figure 2.

Relationship Between Gender Parity and Women's Empowerment—Nigeria in Global Context. Scatter plot displaying the relationship between GGPI (x-axis) and WEI (y-axis) for all 114 countries. Nigeria is highlighted as a magenta star. The red dashed trend line represents the linear regression model (WEI = -0.0110 + 0.8768 × GGPI, R² = 0.705). The strong positive correlation (r = 0.839) demonstrates that gender parity explains 70.5% of variance in empowerment outcomes globally. Nigeria's position below the trend line indicates underperformance relative to its gender parity level. Yellow text box displays correlation statistics.

Figure 2.

Relationship Between Gender Parity and Women's Empowerment—Nigeria in Global Context. Scatter plot displaying the relationship between GGPI (x-axis) and WEI (y-axis) for all 114 countries. Nigeria is highlighted as a magenta star. The red dashed trend line represents the linear regression model (WEI = -0.0110 + 0.8768 × GGPI, R² = 0.705). The strong positive correlation (r = 0.839) demonstrates that gender parity explains 70.5% of variance in empowerment outcomes globally. Nigeria's position below the trend line indicates underperformance relative to its gender parity level. Yellow text box displays correlation statistics.

This validates theoretical frameworks emphasizing gender parity's role [

39,

40,

47]. Politically, women's representation enhances attention to gender issues and challenges leadership stereotypes [

48,

49,

50]. Economically, women's participation enables autonomous decision-making and reduces patriarchal dependency [

3,

22]. Educationally, gender parity develops human capital and credentials women for advancement [

51,

52,

53]. The empirical evidence confirms these mechanisms operate consistently across contexts [

54,

55].

3.2. Nigeria's Position: Comparative Underperformance

Nigeria scores 0.444 on the WEI, ranking 99th out of 114 countries globally—placing it in the bottom 15 countries measured. This absolute positioning indicates severe underperformance, but comparative context reveals the deficit's magnitude more clearly. Nigeria scores 26.9% below the global average (0.607) and 9.5% below even its Sub-Saharan African regional average (0.491). Within Sub-Saharan Africa's 28 countries in the dataset, Nigeria ranks 18th—bottom third of its own region despite possessing advantages including substantial oil revenues, absence of active nationwide conflict, and constitutional democracy.

Nigeria's GGPI score of 0.514 ranks among the world's lowest, indicating severe gender parity deficits across political, economic, and educational domains. Nigerian women's parliamentary representation of 4.5% ranks 181st globally, far below the global average of 26% and Sub-Saharan African average of 25% [

15]. Educational gender gaps persist particularly in northern regions where only 47% of girls attend primary school compared to 69% of boys, reflecting intersecting barriers including poverty, cultural norms, early marriage, inadequate infrastructure, and insurgency impacts [

17,

18,

56]. Economically, women face gender wage gaps estimated at 30-40%, limited access to credit, and disproportionate unpaid care work [

19,

20,

57].

Nigeria's clustering with severely disadvantaged countries experiencing active conflict (Yemen: 0.141), extreme poverty (Niger: 0.307), or severe repression (Pakistan: 0.337) is particularly striking given Nigeria's relative advantages [

42]. This suggests Nigeria's underperformance reflects policy failures and weak institutional implementation rather than insurmountable structural barriers [

27,

58]. The comparison is humbling: Bangladesh (0.443, rank 100) performs essentially identically to Nigeria despite lower per capita income; several conflict-affected countries including Burundi (0.530) substantially exceed Nigeria despite facing more severe challenges.

3.3. Machine Learning Clustering: Nigeria's Peer Group

K-means clustering partitioned 114 countries into four clusters based on empowerment characteristics. Nigeria belongs to Cluster 2, the low-empowerment cluster (WEI: 0.307-0.530, GGPI: 0.428-0.765), containing 42 countries including Bangladesh, Burkina Faso, Benin, Gambia, and Côte d'Ivoire from Sub-Saharan Africa; Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras from Latin America; and Egypt, Iraq, and Jordan from Northern Africa and Western Asia.

However, Rwanda (WEI 0.565, GGPI 0.846) demonstrates that deliberate intervention can rapidly improve gender parity even in resource-constrained contexts. The clustering reveals shared challenges across diverse contexts while identifying outliers offering instructive lessons.

3.4. Peer Comparisons: Learning from Success

Comparative analysis identifies several peer and aspirational countries offering replicable lessons for Nigeria:

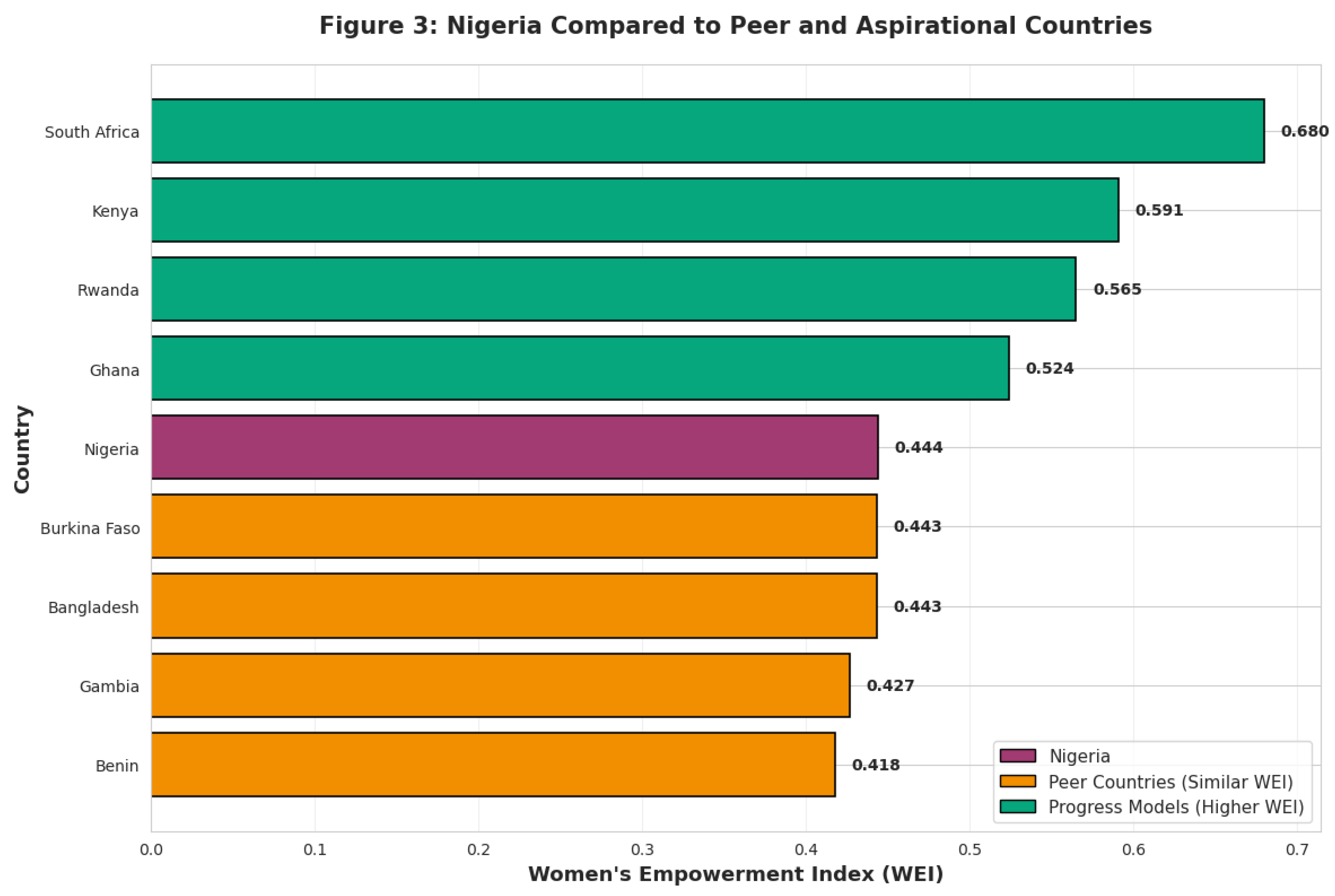

Figure 3.

Nigeria Compared to Peer and Aspirational Countries. Horizontal bar chart comparing Nigeria (magenta) with peer countries having similar WEI scores (orange: Bangladesh, Burkina Faso, Benin, Gambia) and progress models with higher empowerment (green: Ghana, Rwanda, Kenya, South Africa). WEI scores are displayed to the right of each bar. The visualization demonstrates achievable gaps: Ghana (+18.0%), Rwanda (+27.3%), Kenya (+33.1%), and South Africa (+53.2%) provide replicable models at different ambition levels.

Figure 3.

Nigeria Compared to Peer and Aspirational Countries. Horizontal bar chart comparing Nigeria (magenta) with peer countries having similar WEI scores (orange: Bangladesh, Burkina Faso, Benin, Gambia) and progress models with higher empowerment (green: Ghana, Rwanda, Kenya, South Africa). WEI scores are displayed to the right of each bar. The visualization demonstrates achievable gaps: Ghana (+18.0%), Rwanda (+27.3%), Kenya (+33.1%), and South Africa (+53.2%) provide replicable models at different ambition levels.

Ghana (WEI: 0.524, GGPI: 0.563, Rank: 81): Most directly relevant comparator given similar West African context, comparable development level (both Medium HDI), shared colonial history, and comparable population size. Ghana's 18.0% empowerment advantage reflects sustained investment in girls' education through Free Compulsory Universal Basic Education, scholarship programs targeting vulnerable girls, community mobilization campaigns involving traditional leaders, and incremental political reforms [

9,

53]. Ghana demonstrates that steady, pragmatic approaches without dramatic institutional transformation can produce meaningful progress within 10–15-year timeframes.

Rwanda (WEI: 0.565, GGPI: 0.846, Rank: 71): Despite lower HDI than Nigeria, Rwanda achieves 27.3% higher empowerment through deliberate post-genocide political commitment. Rwanda's constitution mandates 30% minimum female representation in all decision-making bodies, implemented through reserved seats and party list requirements [

50,

59,

60]. Parliament currently contains 61% women—world's highest proportion—demonstrating how political will can overcome severe resource constraints. Rwanda's trajectory proves transformative change is possible even in challenged contexts if leadership commits authentically [

9].

Kenya (WEI: 0.591, GGPI: 0.769, Rank: 66): East African regional leader achieving 33.1% higher empowerment than Nigeria through combination of educational expansion (achieving near-universal primary enrollment), economic liberalization creating opportunities for women entrepreneurs, civil society activism pressuring for reforms, and incremental political gains with women holding approximately 25% of parliamentary seats [

9,

61]. Kenya's trajectory represents significant but not transformative progress, balancing reform with political pragmatism—achievable for Nigeria within 10-year timeframe.

South Africa (WEI: 0.680, GGPI: 0.823, Rank: 40): Regional leader achieving 53.2% higher empowerment than Nigeria, representing longer-term aspirational target. South Africa's comprehensive post-apartheid constitutional settlement embedded gender equality provisions, proportional representation electoral systems facilitate women's inclusion, strong civil society and women's movements maintain pressure for implementation, and relatively developed economy provides opportunities [

9,

62]. However, South Africa also reveals implementation challenges—gender-based violence remains severe despite strong legal frameworks, and economic empowerment lags political gains—cautioning that legislation alone proves insufficient without cultural transformation and enforcement [

62].

These comparisons validate several critical insights:

structural constraints do not predetermine outcomes (Rwanda and Ghana achieved superior results despite comparable or worse starting conditions);

multiple pathways exist (Rwanda's quota-driven transformation vs. Ghana's education-focused incrementalism);

progress requires sustained commitment (all successful countries maintained focus across electoral cycles); and

comprehensive approaches work better (South Africa's multi-sectoral strategy achieved highest outcomes despite implementation challenges) [

9,

50].

3.5. Evidence-Based Scenario Projections

Drawing on peer country experiences and our validated linear regression model, we developed three evidence-based policy scenarios projecting Nigeria's potential improvement under different intervention approaches. Each scenario specifies target GGPI levels based on actual peer achievements, uses our model to project corresponding WEI outcomes, and identifies key policy interventions.

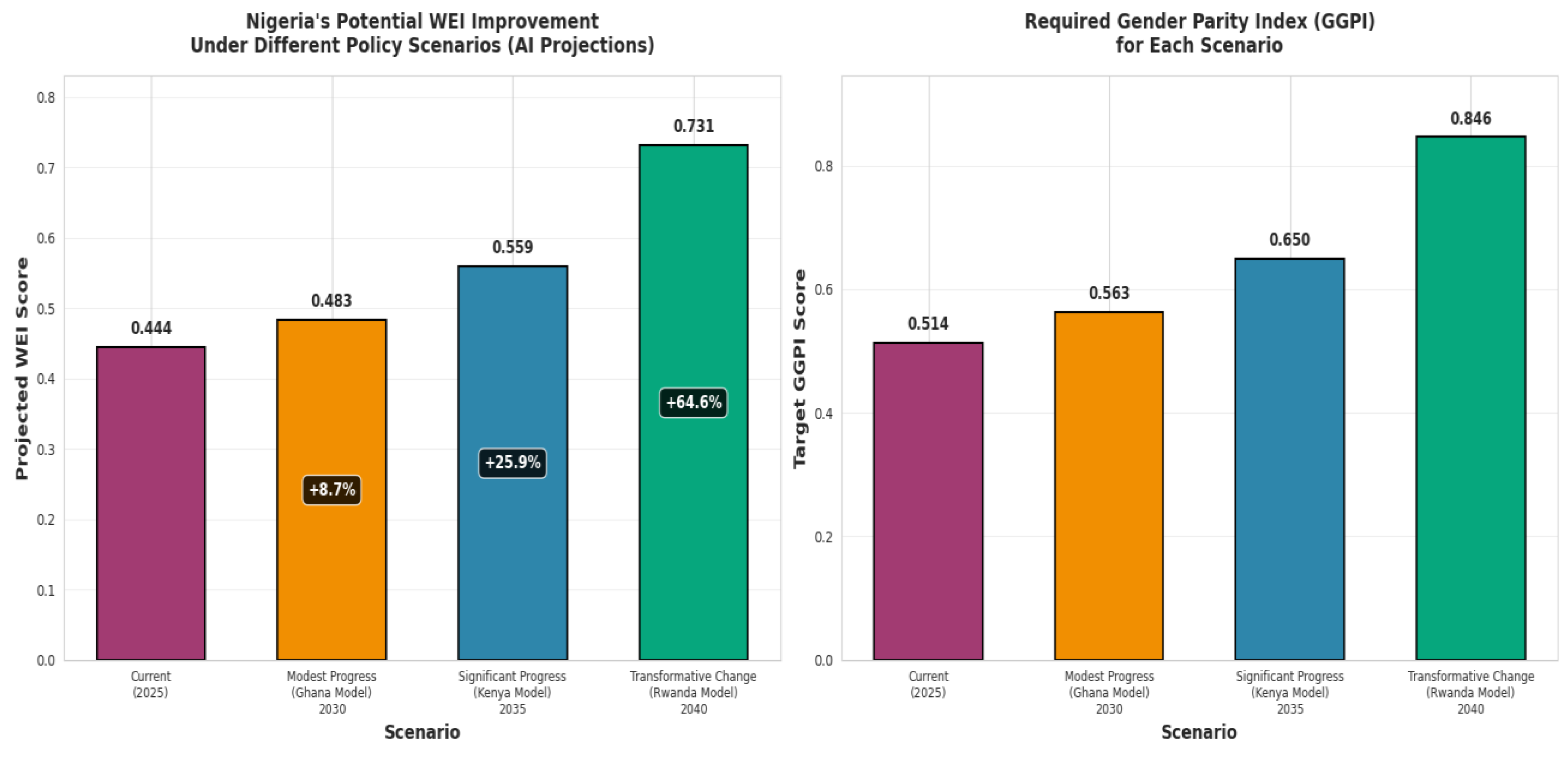

Figure 4.

Evidence-Based Policy Scenario Projections for Nigeria. Dual-panel visualization showing Nigeria's potential improvement pathways. Left panel displays projected WEI scores under four scenarios with improvement percentages: Current 2025 (0.444), Modest Progress/Ghana Model 2030 (0.483, +8.7%), Significant Progress/Kenya Model 2035 (0.559, +25.9%), and Transformative Change/Rwanda Model 2040 (0.731, +64.6%). Right panel shows corresponding target GGPI levels required for each scenario. Color-coding distinguishes intervention levels from modest (orange) to transformative (green). All projections are generated using the validated linear regression model based on actual peer country achievements.

Figure 4.

Evidence-Based Policy Scenario Projections for Nigeria. Dual-panel visualization showing Nigeria's potential improvement pathways. Left panel displays projected WEI scores under four scenarios with improvement percentages: Current 2025 (0.444), Modest Progress/Ghana Model 2030 (0.483, +8.7%), Significant Progress/Kenya Model 2035 (0.559, +25.9%), and Transformative Change/Rwanda Model 2040 (0.731, +64.6%). Right panel shows corresponding target GGPI levels required for each scenario. Color-coding distinguishes intervention levels from modest (orange) to transformative (green). All projections are generated using the validated linear regression model based on actual peer country achievements.

Scenario 1: Modest Progress—Ghana Model (Target: 2030)

This scenario assumes Nigeria emulates Ghana's pragmatic approach emphasizing sustained investment in girls' education without dramatic institutional reforms. If Nigeria achieves Ghana's current GGPI level (0.563) through scholarship programs, infrastructure improvements (particularly separate sanitation facilities encouraging girls' attendance), community mobilization challenging norms against girls' education, and incremental political reforms including voluntary party quotas, our model projects Nigeria's WEI would improve to 0.483—an 8.7% gain from current 0.444.

Timeline: Five-year timeframe (2025-2030) aligns with typical education policy impact cycles—interventions implemented now show measurable effects by decade's end. However, success requires overcoming current policy inertia, allocating adequate budgets (minimum 5% of national budget to gender programs), and sustaining implementation despite political transitions.

Key Interventions: Eliminate school fees at basic education level; construct schools in underserved rural areas particularly northern states; recruit and deploy female teachers to regions with severe shortages; implement menstrual hygiene management programs; launch community engagement campaigns involving traditional and religious leaders; pass and enforce child rights legislation prohibiting marriage under age 18 nationally.

Scenario 2: Significant Progress—Kenya Model (Target: 2035)

This scenario assumes comprehensive interventions combining educational expansion with economic empowerment programs, moderate political reforms, strengthened legal frameworks, and enhanced institutional capacity. If Nigeria achieves GGPI of 0.650 (Kenya's approximate level) through these combined approaches, our model projects WEI improvement to 0.559—a 25.9% gain.

Timeline: Ten-year timeframe (2025-2035) reflects longer implementation cycles required for comprehensive reforms affecting multiple sectors simultaneously. Success requires political coalition-building spanning electoral cycles, substantial resource mobilization, and capacity strengthening across government institutions.

Key Interventions: All Scenario 1 interventions plus: establish legislative gender quotas requiring minimum 30% female representation in National Assembly, state legislatures, and local government councils; strengthen Violence Against Persons Prohibition Act implementation across all states through specialized courts, trained prosecutors, and victim support services; launch national economic empowerment programs including microfinance, skills training, and entrepreneurship support; reform corporate governance requiring gender diversity in boards of publicly listed companies; expand girls' participation in STEM education through targeted programs; strengthen women's organizations and civil society capacity for advocacy and monitoring.

Scenario 3: Transformative Change—Rwanda Model (Target: 2040)

This scenario assumes adoption of Rwanda's transformative approach with constitutional gender quotas, aggressive educational expansion achieving full gender parity, comprehensive legal reforms, and sustained political commitment over extended period. If Nigeria achieves GGPI of 0.846 (Rwanda's current level), our model projects WEI improvement to 0.731—a 64.6% gain approaching South Africa's regional leadership position.

Timeline: Fifteen-year timeframe (2025-2040) acknowledges that transformative institutional change requires generational commitment spanning multiple presidential and gubernatorial terms. Rwanda's transformation occurred over approximately 20 years post-genocide, with constitutional provisions adopted early but full implementation requiring sustained effort.

Key Interventions: All Scenario 1 and 2 interventions plus: constitutional amendment establishing gender quotas across all government levels with strong enforcement mechanisms and penalties for non-compliance; comprehensive education reform achieving universal gender parity with particular focus on northern regions; economic policies promoting women's access to credit, land ownership, and entrepreneurship at scale; cultural transformation campaigns through media, education, and community engagement challenging patriarchal norms; security sector reforms addressing gender-based violence systematically; establishment of strong accountability mechanisms including independent Gender Equality Commission with investigative and enforcement powers.

Comparative Analysis: The scenarios represent progressively ambitious interventions with correspondingly greater potential gains but higher implementation requirements. The modest Ghana model offers realistic near-term progress (8.7% by 2030) through focused interventions requiring moderate political commitment. The significant Kenya model achieves substantial transformation (25.9% by 2035) through comprehensive approaches requiring strong coalitions and sustained resources. The transformative Rwanda model approaches regional leadership (64.6% by 2040) but demands generational commitment, constitutional reforms, and cultural transformation—feasible but requiring prioritization across multiple electoral cycles.

Critically, these projections are grounded in actual peer country achievements rather than theoretical possibilities, demonstrating feasibility through existence proof. If Rwanda, despite genocidal conflict and extreme poverty, achieved GGPI of 0.846, and if Ghana, with comparable resources to Nigeria, achieved 0.563, Nigeria can realistically target these outcomes given political will and sustained implementation.

4. Policy Implications and Recommendations

4.1. Key Insights

The strong GGPI-WEI correlation (r = 0.839, R² = 0.705) validates investing in gender equality as development strategy. Gender parity explains 70.5% of empowerment variance, indicating that interventions improving women's representation and participation translate directly into development gains [

22,

54].

Nigeria's 99th ranking globally and 18th within Sub-Saharan Africa—9.5% below regional average—indicates policy failure rather than structural inevitability. Peer countries facing comparable constraints (Rwanda, Ghana) substantially exceed Nigeria's performance, proving progress is achievable [

9,

59].

Machine learning clustering identifies realistic progression pathways: Ghana-level (0.524) within five years, Kenya-level (0.591) within ten years, South Africa-level (0.680) within fifteen years. Scenario modeling demonstrates 8.7% improvement by 2030, 25.9% by 2035, and 64.6% by 2040 under different intervention approaches.

4.2. Priority Recommendations

Immediate (2025-2027):

Medium-Term (2027-2032):

Long-Term (2032-2040):

Constitutional amendment embedding gender equality without exemptions [

9]

National dialogue convening traditional leaders, religious leaders, and civil society

Establish National Gender Equality Commission as independent accountability body

4.3. Stakeholder Actions and Monitoring

Federal Government: Demonstrate political will through appointments to "hard" portfolios, allocate minimum 5% of budget to gender programs, enact reforms, coordinate federal-state action [

21,

58].

State Governments: Progressive states pilot programs, adopt quotas, eliminate child marriage, invest in education infrastructure [

9].

Civil Society: Sustain advocacy, scale effective programs, provide services including legal aid and scholarships [

10,

62].

Private Sector: Implement workplace equality policies, adopt 30% board diversity targets, fund girls' education [

22].

Monitoring Framework:

KPIs: WEI targets (0.483 by 2030, 0.559 by 2035, 0.731 by 2040); female parliamentary representation (30% by 2030, 50% by 2040); educational gender parity (0.95+ by 2030)

Mechanisms: Annual progress reports, independent audits, civil society scorecards, international benchmarking

5. Conclusions

This study employed machine learning and predictive analytics to systematically analyze women's empowerment patterns across 114 countries, generating evidence-based insights for Nigeria's gender policy advancement. Our analysis reveals that Nigeria, ranking 99th globally with WEI score of 0.444, substantially underperforms relative to both the global average (0.607) and its Sub-Saharan African regional average (0.491). This 9.5% deficit below regional peers indicates Nigeria-specific policy failures beyond structural challenges common across developing contexts.

The analysis demonstrates strong positive correlation (r = 0.839) between gender parity and empowerment globally, with gender parity explaining 70.5% of variance in empowerment outcomes. This empirical finding validates that interventions improving women's political representation, economic participation, and educational attainment directly translate into broader empowerment gains, making the economic case for gender equality investments as development strategy rather than merely moral imperative. Machine learning clustering grouped Nigeria with 41 other countries sharing similar low-empowerment characteristics, while also revealing which countries represent achievable next-tier targets.

Critically, comparative analysis reveals that peer countries with similar or even more severe structural constraints achieved substantially higher empowerment through deliberate policy interventions. Ghana scores 18.0% higher through sustained educational investment and incremental reforms. Rwanda achieves 27.3% higher empowerment through constitutional gender quotas despite lower economic development. Kenya reaches 33.1% higher through comprehensive multi-sectoral approaches. South Africa leads the region at 53.2% above Nigeria through post-apartheid constitutional commitments and strong legal frameworks. These comparative cases validate that Nigeria's empowerment deficit, while substantial, is amenable to policy intervention rather than structurally predetermined.

Evidence-based scenario modeling, grounded in actual peer country achievements and our validated linear regression model, projects that Nigeria could realistically improve its WEI score by 8.7% by 2030 through modest Ghana-style educational reforms, 25.9% by 2035 through comprehensive Kenya-model interventions combining educational, economic, and political reforms, or 64.6% by 2040 through transformative Rwanda-model constitutional and institutional change. These projections provide policymakers with actionable benchmarks and realistic timelines, moving beyond aspirational rhetoric to concrete, achievable targets.

The study makes several scholarly contributions. Methodologically, it demonstrates how machine learning techniques including K-means clustering and linear regression modeling can enhance comparative policy analysis, generating insights difficult to obtain through traditional qualitative or statistical methods alone. The analytical workflow prioritizes transparency and interpretability, enabling replication by other scholars and adaptation to different country contexts. Empirically, it provides systematic evidence benchmarking Nigeria against 114 countries globally, identifying specific empowerment deficits, quantifying the gender parity-empowerment relationship, and modeling realistic improvement scenarios. Theoretically, it validates linkages between gender parity interventions and broader empowerment outcomes, demonstrating that political agency—manifested through institutional design, resource allocation, and policy implementation—determines outcomes within structurally defined possibility spaces. Practically, it translates abstract policy recommendations into concrete scenarios with specific targets, timelines, and intervention packages based on proven approaches rather than theoretical possibilities.

While our analysis is subject to limitations inherent in cross-sectional data and country-level aggregation, and while scenario projections necessarily assume adaptability of peer-country pathways to Nigeria's unique context, the combined analytical approach—integrating descriptive statistics, machine learning clustering, regression modeling, and comparative scenario analysis—provides robust evidence for policy action. The consistency of findings across multiple analytical methods strengthens confidence in the core insight: Nigeria's empowerment deficit is policy-responsive rather than structurally predetermined.

However, translating evidence into practice confronts political economy challenges. Nigeria's gender equality deficit persists not from ignorance of solutions but from political resistance by male elites threatened by women's inclusion, resource constraints and competing priorities in contexts of limited state capacity, implementation weaknesses undermining even well-designed policies, and cultural conservatism viewing gender equality as Western imposition incompatible with African values. Overcoming these obstacles requires sustained political mobilization, strategic coalition-building spanning diverse stakeholders, evidence-based advocacy leveraging comparative benchmarks, and persistent pressure from civil society, women's movements, and international partners.

Nigeria stands at a critical juncture. One path continues the current trajectory of slow, inadequate progress perpetuating gender inequality, squandering human capital, and falling short of development aspirations. The alternative path embraces evidence-based transformation through deliberate, sustained, coordinated action producing measurable empowerment gains within realistic timeframes. The comparative evidence demonstrates feasibility—peer countries achieved dramatic improvements through political commitment and strategic interventions. The scenario modeling provides a roadmap with specific benchmarks, timelines, and intervention packages based on proven approaches. The statistical analysis quantifies relationships and projections with empirical rigor.

The critical question is not whether Nigeria can improve—the evidence unequivocally demonstrates it can—but whether Nigerian leadership, institutions, civil society, and citizens will commit to the necessary sustained effort. With over 60% of Nigeria's population under age 25, decisions made today about girls' education, women's economic participation, and female political representation will shape national trajectories for decades. Educated, empowered young women can drive development and democratic consolidation; marginalized, uneducated young women become a lost generation perpetuating intergenerational disadvantage.

The path forward requires both urgency and realism. Urgency because Nigeria's demographic trajectory creates both opportunity and risk, and because time remaining to achieve SDG 2030 commitments shrinks rapidly. Realism because transformation requires sustained effort spanning electoral cycles, resources currently inadequate requiring mobilization, and capacity development enabling effective implementation. But the evidence from Rwanda, Ghana, Kenya, and South Africa—countries that faced comparable or more severe challenges yet achieved substantially higher empowerment—proves that progress is possible when political will meets evidence-based strategy.

This study's evidence, analysis, and recommendations provide the knowledge base for stakeholders choosing transformation. The ultimate measure of success lies not in academic citations but in real-world impacts: more girls completing quality education, more women occupying leadership positions, more equitable distribution of power and opportunities, and a more just society where gender determines neither life chances nor leadership possibilities. Achieving this vision requires action translating evidence into policy, policy into implementation, and implementation into transformed realities for millions of Nigerian girls and women. The data demonstrates the destination is reachable; political will must chart the course.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.A.K. and A.G.; methodology, P.A.K.; formal analysis, P.A.K.; writing original draft preparation, P.A.K.; writing—review and editing, P.A.K. and A.G.; supervision, A.G.; validation, A.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The Women's Empowerment Index (2022) dataset analyzed in this study is publicly available from the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Derived data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2015.

- African Union. Agenda 2063: The Africa We Want; AU: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2015.

- Duflo, E. Women Empowerment and Economic Development. J. Econ. Lit. 2012, 50, 1051–1079. [CrossRef]

- Kabeer, N.; Natali, L. Gender Equality and Economic Growth: Is There a Win-Win? IDS Work. Pap. 2013, 417, 1–58.

- Htun, M.; Weldon, S.L. The Civic Origins of Progressive Policy Change. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 2012, 106, 548–569. [CrossRef]

- Dempere, J.; Abdalla, S. The Impact of Women's Empowerment on the Corporate Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Disclosure. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8173. [CrossRef]

- Mavisakalyan, A.; Tarverdi, Y. Gender and Climate Change: Do Female Parliamentarians Make Difference? Eur. J. Polit. Econ. 2019, 56, 151–164. [CrossRef]

- Mama, A. What Does It Mean to Do Feminist Research in African Contexts? Fem. Rev. 2011, 98, e4–e20. [CrossRef]

- Tripp, A.M.; Casimiro, I.; Kwesiga, J.; Mungwa, A. African Women's Movements: Transforming Political Landscapes; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009.

- Imam, A.; Mama, A.; Sow, F. Engendering African Social Sciences; CODESRIA: Dakar, Senegal, 2017.

- Pereira, C. Configuring "Global," "National," and "Local" in Governance Agendas and Women's Struggles in Nigeria. Soc. Res. 2002, 69 (3), 781–804.

- UN Women. COVID-19 and Women in Africa; UN Women: New York, NY, USA, 2021.

- Alon, T.; Doepke, M.; Olmstead-Rumsey, J.; Tertilt, M. The Impact of COVID-19 on Gender Equality. NBER Work. Pap. 2020, 26947. [CrossRef]

- UNDP. Women's Empowerment Index 2022: Measuring Gender Equality Globally; UNDP: New York, NY, USA, 2022.

- Inter-Parliamentary Union. Women in National Parliaments: World and Regional Averages; IPU: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. Available online: https://www.ipu.org/our-impact/gender-equality/women-in-parliament (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- National Universities Commission. Nigerian University System Statistical Digest; NUC: Abuja, Nigeria, 2019.

- UNICEF. Nigeria Education in Emergencies: Working Document; UNICEF: Abuja, Nigeria, 2020.

- UNESCO. Global Education Monitoring Report 2020: Gender Report—A New Generation; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2020.

- Anyanwu, J.C. Analysis of Gender Equality in Youth Employment in Africa. Afr. Dev. Rev. 2016, 28 (4), 397–415. [CrossRef]

- Mordi, C.; Simpson, R.; Singh, S.; Okafor, C. The Role of Cultural Values in Understanding Challenges Faced by Female Entrepreneurs in Nigeria. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2010, 25, 5–21. [CrossRef]

- Okonjo-Iweala, N. Reforming the Unreformable: Lessons from Nigeria; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012.

- World Bank. World Development Report 2012: Gender Equality and Development; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2012.

- National Bureau of Statistics. 2019 Poverty and Inequality in Nigeria; NBS: Abuja, Nigeria, 2020.

- Cornwall, A.; Harrison, E.; Whitehead, A. Gender Myths and Feminist Fables: The Struggle for Interpretive Power in Gender and Development. Dev. Change 2007, 38 (1), 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Kabeer, N. Gender Equality, Economic Growth, and Women's Agency: The 'Endless Variety' and 'Monotonous Similarity' of Patriarchal Constraints. Fem. Econ. 2016, 22, 295-321. [CrossRef]

- Agbalajobi, D.T. Women's Participation and the Political Process in Nigeria: Problems and Prospects. Afr. J. Polit. Sci. Int. Relat. 2010, 4, 75–82.

-

Olubela, A. Nigerian Women's Participation in Politics: Historical and Social Acceptance Issues. Afr. Soc. Sci. Rev. 2021, 12 (1).

- Okome, M.O. Domestic, Regional, and International Protection of Nigerian Women Against Discrimination: Constraints and Possibilities. Afr. Stud. Q. 2003, 6, 33–65.

- Vinuesa, R.; Azizpour, H.; Leite, I.; et al. The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 233. [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.D.; Schmidt-Traub, G.; Mazzucato, M.; et al. Six Transformations to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 805–814. [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, M.; Griggs, D.; Visbeck, M. Policy: Map the Interactions Between Sustainable Development Goals. Nature 2016, 534, 320–322. [CrossRef]

- Ametepey, S.O.; Aigbavboa, C.; Thwala, W.D.; Addy, H. The Impact of AI in Sustainable Development Goal Implementation: A Delphi Study. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3858. [CrossRef]

- Kaddoura, S.; Popescu, D.E.; Hemanth, J.D.; Kose, U. A Systematic Review on Machine Learning Models for Online Learning and Examination Systems. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2022, 8, e986. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Yang, J.; Fu, X.; Zheng, Q.; Song, X.; Fu, Z.; Wang, J.; Liang, Y.; Yin, H.; Liu, Z.; et al. Water Quality Prediction Based on LSTM and Attention Mechanism: A Case Study of the Burnett River, Australia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13231. [CrossRef]

- Kedir, A.; Elhiraika, A.; Chinzara, Z.; Sandjong, D. Growth and Development Finance Required for Achieving Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in Africa. Afr. Dev. Rev. 2017, 29 (S1), 15–26. [CrossRef]

- Asongu, S.A.; Odhiambo, N.M. Governance and Social Media in African Countries: An Empirical Investigation. Telecommun. Policy 2019, 43, 411–425. [CrossRef]

- MacQueen, J. Some Methods for Classification and Analysis of Multivariate Observations. In Proceedings of the Fifth Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability; Le Cam, L.M., Neyman, J., Eds.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1967; Volume 1, pp. 281–297.

- James, G.; Witten, D.; Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R. An Introduction to Statistical Learning: With Applications in Python; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2021.

- Sen, A. Development as Freedom; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999.

- Kabeer, N. Resources, Agency, Achievements: Reflections on the Measurement of Women's Empowerment. Dev. Change 1999, 30, 435–464. [CrossRef]

- Gertler, P.J.; Martinez, S.; Premand, P.; Rawlings, L.B.; Vermeersch, C.M.J. Impact Evaluation in Practice, 2nd ed.; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016.

- UNDP. Human Development Report 2020: The Next Frontier—Human Development and the Anthropocene; UNDP: New York, NY, USA, 2020.

- World Economic Forum. Global Gender Gap Report 2022; WEF: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- Jain, A.K. Data Clustering: 50 Years Beyond K-means. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2010, 31, 651–666. [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; et al. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830.

- Angrist, J.D.; Pischke, J.S. Mostly Harmless Econometrics: An Empiricist's Companion; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2009.

- Nussbaum, M.C. Women and Human Development: The Capabilities Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000.

- Phillips, A. The Politics of Presence; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1995.

- Mansbridge, J. Should Blacks Represent Blacks and Women Represent Women? A Contingent "Yes". J. Polit. 1999, 61, 628–657. [CrossRef]

- Dahlerup, D.; Freidenvall, L. Quotas as a 'Fast Track' to Equal Representation for Women: Why Scandinavia Is No Longer the Model. Int. Fem. J. Polit. 2005, 7, 26–48. [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, C.B.; Young, J. New Lessons: The Power of Educating Adolescent Girls; Population Council: New York, NY, USA, 2009.

- Psaki, S.R.; McCarthy, K.J.; Mensch, B.S. Measuring Gender Equality in Education: Lessons from Trends in 43 Countries. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2018, 44, 117–142. [CrossRef]

- Aikman, S.; Unterhalter, E. Beyond Access: Transforming Policy and Practice for Gender Equality in Education; Oxfam: Oxford, UK, 2005.

- King, E.M.; Mason, A.D. Engendering Development Through Gender Equality in Rights, Resources, and Voice; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2001.

- Klasen, S. Low Schooling for Girls, Slower Growth for All? Cross-Country Evidence on the Effect of Gender Inequality in Education on Economic Development. World Bank Econ. Rev. 2002, 16, 345–373. [CrossRef]

- Matfess, H. Women and the War on Boko Haram: Wives, Weapons, Witnesses; Zed Books: London, UK, 2017.

- Onyishi, C.J.; Ejike-Alieji, A.U.P.; Ajaero, C.K.; Mbaegbu, C.C.; Ezeibe, C.C.; Onyebueke, V.U.; Mbah, P.O.; Nzeadibe, T.C. COVID-19 Pandemic and Informal Urban Governance in Africa: A Political Economy Perspective. J. Asian Afr. Stud. 2021, 56 (6), 1226–1250. [CrossRef]

- Federal Republic of Nigeria. National Gender Policy: Situation Analysis; Federal Ministry of Women Affairs and Social Development: Abuja, Nigeria, 2006.

- Powley, E. Rwanda: The Impact of Women Legislators on Policy Outcomes Affecting Children and Families. Background Paper for The State of the World's Children 2007; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2007.

- Burnet, J.E. Gender Balance and the Meanings of Women in Governance in Post-Genocide Rwanda. Afr. Aff. 2008, 107, 361–386. [CrossRef]

- Unterhalter, E.; North, A.; Arnot, M.; et al. Interventions to Enhance Girls' Education and Gender Equality: Education Rigorous Literature Review; DFID: London, UK, 2014.

- Hassim, S. Women's Organizations and Democracy in South Africa: Contesting Authority; University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, USA, 2006.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).