1. Introduction

Global climate change, standing as one of the most pressing threats to our planet, serves as an unavoidable wake-up call, compelling every industry to transition toward sustainable practices [

1]. At the heart of this challenge lies the construction sector, heavily scrutinized for its massive energy consumption and environmental footprint [

2]. Research indicates that this sector is responsible for approximately 35% of global carbon dioxide (CO₂) emissions [

1]. The primary culprit is Portland cement, the production of which accounts for roughly 8% of global emissions [

3]. These statistics expose the unsustainable nature of traditional building materials and underscore the critical need for a fundamental shift in construction methodologies.

This urgency has driven researchers to seek viable alternatives to cement. Initially, efforts focused on reducing cement consumption by incorporating industrial by-products, such as fly ash and GGBFS, into mixtures [

4]. However, a true paradigm shift occurred with the development of entirely cement-free binders [

5]. Geopolymers, first conceptualized by Joseph Davidovits in 1991 [

6], have emerged as a groundbreaking substitute. Driven by the demand for energy-efficient materials, recent research has focused on transforming geopolymer matrices into high-performance composites through reinforcement with waste-derived or natural fibers [

7,

8].

Nevertheless, developing fiber-reinforced geopolymer composites—especially utilizing waste fibers—presents challenges. The mismatch between the hydrophilic nature of natural fibers and the highly alkaline environment (pH> 13) of the geopolymer matrix often results in weak interfacial bonding [

9]. This incompatibility can compromise internal adhesion, increasing delamination risks. Furthermore, the porous structure of natural fibers leads to dimensional instability through repeated swelling and shrinking cycles, while the highly alkaline pore solution accelerates the degradation of amorphous fiber components [

10,

11]. Long-term durability is further threatened by 'fiber mineralization,' where calcium hydroxide migrates into the fiber lumen, leading to embrittlement via alkaline hydrolysis of lignin and hemicellulose [

12,

13].

To address this, studies have explored pretreatments such as alkali processing [

14] or hot water immersion [

15]. These treatments remove surface waxes and disrupt hydrogen bonding, increasing surface roughness [

16] However, recent research suggests a 'self-treatment' mechanism, where the geopolymer's inherent alkalinity performs in-situ surface modification, potentially rendering separate pre-alkalization unnecessary [

17,

18] Although fiber reinforcement is essential for transitioning geopolymers from a brittle to a ductile state, excessive content can lead to agglomeration; achieving the right balance remains a complex optimization task [

8].

The literature highlights the superior properties of 100% GGBFS-based geopolymers due to their calcium-rich composition and fast reaction kinetics [

19]. However, their inherent brittleness necessitates reinforcement [

7]. Recent work has shown promise; Zheng et al. (2023) [

20] achieved a 25% increase in MOR using waste paper pulp in a slag-fly ash matrix. Similarly, the incorporation of wood by-products has gained traction as a viable strategy to produce lightweight construction panels. Studies have demonstrated that wood fibers or sawdust can be effectively encapsulated within the geopolymer matrix, offering a sustainable balance between reduced density and structural integrity, provided that the fiber-matrix compatibility is addressed [

21,

22]. Thermal properties are equally critical; studies have shown that incorporating natural aggregates or fibers can significantly reduce thermal conductivity, demonstrating the dual potential for structural support and insulation [

23].

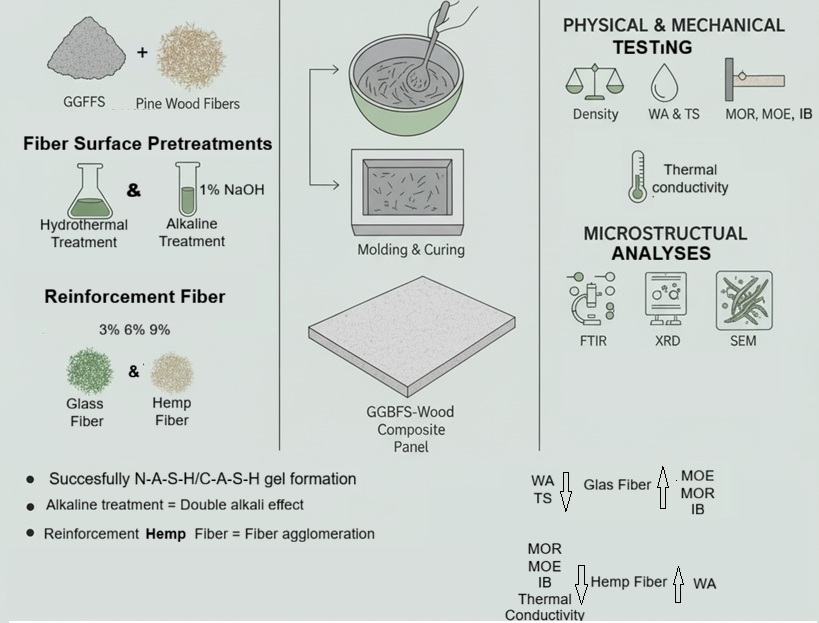

Despite these advancements, a significant gap remains. Most studies focus on fly ash or metakaolin systems reinforced with synthetic fibers. There is a scarcity of in-depth research on the interaction between natural/waste fibers and 100% GGBFS-based geopolymers—an industrial byproduct with unique reaction kinetics. This study addresses this gap by engineering a fully waste-derived, sustainable geopolymer panel. The core objective is to determine optimal curing conditions for a 100% slag-based matrix and systematically evaluate the effects of glass and hemp fiber additions (3%, 6%, 9%) on its physico-mechanical properties, thereby valorizing local byproducts for carbon-neutral construction.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Binder and Chemical Activators

GGBFS, sourced from an iron and steel plant in the Samsun region, served as the primary binder. Its chemical composition was characterized using an X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectrometer (RIGAKU-SUPERMINI 200). Consistent with high-reactivity precursors described in the literature, the slag exhibited a Blaine fineness of approximately 4250 cm²/g and a specific gravity of 2.90 g/cm³.

For alkaline activation, a combination of sodium silicate (Na₂SiO₃) and sodium hydroxide (NaOH) was employed. The commercial Na₂SiO₃ solution (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) contained 26.5% SiO₂ and 8% Na₂O by weight (pH 11.36, density 1.35 g/cm³), yielding a silica modulus (Ms) of 3.42. NaOH pellets (Merck) were dissolved in distilled water to prepare an 8 Molar (8 M) solution, which was allowed to cool to room temperature prior to use.

The activator solution was prepared by mixing the Na₂SiO₃ and 8 M NaOH at a weight ratio of 2.5:1. This mixture was stirred for 5 minutes and left to rest for 24 hours to ensure thermal equilibrium and complete depolymerization of silica species. The resulting solution possessed an effective Ms of approximately 1.55—falling within the optimal range (1.0–2.0) for high-strength geopolymers [

24].

2.2. Reinforcement Fibers and Characterization

Softwood (pine) fibers, obtained from the Kastamonu Entegre Gebze Facility, were selected as the primary reinforcement elements. To create a hybrid composite structure, hemp and glass fibers were introduced as additives at 3%, 6%, and 9% by weight of the primary binder.

The pine fibers constituted the main reinforcement network; their chemical composition (cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin) was experimentally analyzed according to standard wet chemistry protocols [

25] to assess suitability. Hemp fibers (HF), utilized as organic additives, were manually cut to a length of approximately 1.5 cm. SEM analysis confirmed an average diameter of 75 μm for the hemp fibers, and their chemical constituents were likewise determined experimentally. Commercial E-glass fibers(GF) (length 12 mm, diameter 13–15 μm) served as inorganic reference additives, with technical properties adopted as reported by the supplier [

26].

2.3. Fiber Surface Pretreatments

To mitigate the adverse effects of amorphous constituents—such as hemicellulose, pectin, and waxes—on fiber-matrix adhesion, surface pretreatments were applied specifically to the pine wood fibers. Conversely, the hemp and glass fibers were incorporated in their as-received state.

Two distinct pretreatment protocols were evaluated, both maintaining a solid-to-liquid ratio of 1:9 to ensure dispersion.

- -

Hydrothermal Treatment: Fibers were immersed in distilled water at 80°C for 24 hours to solubilize starch and water-soluble extractives.

- -

Alkaline Treatment: Fibers were subjected to a 1% NaOH solution at room temperature for 24 hours (mercerization) to strip away hemicellulose and enhance surface roughness.

Following chemical exposure, the fibers were washed with distilled water until a neutral pH (7.0 ± 0.5) was achieved. Excess water was removed via filtration, and fibers were conditioned to an equilibrium moisture content of 10–12% (20 ± 2°C, 65 ± 5% RH).

2.4. Preparation of Composite Panels

2.4.1. Mix Design and Proportions

The composite panels were designed with a target density of 1.3 g/cm³ and final dimensions of 350 × 300 × 12 mm. A fixed activator-to-binder ratio of 0.33 (1:3 by weight) was adopted for all mixtures to ensure standardization. However, the effective liquid content was inherently influenced by the residual moisture in the pretreated fibers and the external application of the 100 mL calcium chloride (CaCl₂) accelerator spray. These variables were carefully managed during fabrication to guarantee consistent workability and mat consolidation. Based on optimal parameters from preliminary trials, the primary reinforcement (pine fibers) was incorporated at a fiber-to-binder weight ratio of 1:9. For hybrid formulations, the additive fiber content was calculated relative to the weight of the GGBFS binder to ensure consistency across all batches.

2.4.2. Fabrication Process

The fabrication began by mixing the weighed GGBFS and alkaline activator solution in a mechanical mixer for 5 minutes to achieve a homogeneous paste.

Prior to their addition to the matrix, a specific interfacial modification was applied to the fibers. The wood fibers (and additive fibers, where applicable) were moistened by spraying with a CaCl₂ solution. The dosage was set at 5% CaCl₂ by weight of the GGBFS. This step aimed to strengthen the fiber-matrix bond by promoting the formation of calcium-based deposits at the interface [

27]. The total volume of the spray solution was fixed at 100 ml for all batches; this volume, along with the initial moisture content of the wood fibers (8.5%), was factored into the overall water-to-binder ratio calculation to maintain rheological stability.

Immediately following the spray treatment, the fibers were gradually added to the binder paste. Mixing continued for an additional 5 minutes until the fibers were uniformly dispersed within the matrix.

2.4.3. Molding and Curing

The fresh geopolymer-fiber mixture was manually spread into stainless steel molds to ensure uniform distribution. The filled molds were then subjected to a pressure of 3 MPa using a cold press at room temperature (23 ± 2°C) for a duration of 24 hours. This specific pressure was determined through preliminary optimization to achieve maximum compaction without compromising the cellular integrity of the wood fibers.

Following the pressing stage, the panels were demolded and transferred to an oven for final curing. The samples were cured at 40°C for 6 hours; a regime selected to facilitate strength development while preventing the micro-cracking and shrinkage often induced by higher temperatures in slag-dominated systems. After curing, the panels were stored at ambient conditions until testing.

2.5. Characterization and Testing

2.5.1. Physical Properties

- -

Density (d): The density of the composite panels was determined in accordance with the TS EN 323 [

28] standard. The mass of each specimen was measured using an analytical balance (±0.001 g precision), while volumes were calculated from dimensions taken with a digital caliper (±0.01 mm). The reported density represents the average of three specimens per panel group.

- -

Water Absorption (WA) and Thickness Swelling (TS): Dimensional stability was evaluated based on the TS EN 317 [

29] standard following 24 hours of water immersion. Prior to testing, eight replicate samples were conditioned at 20±2°C and 65±5% relative humidity. Changes in mass and thickness were recorded to calculate WA and TS, respectively. Results are presented as the arithmetic mean of the eight replicates.

- -

Thermal Conductivity: Thermal conductivity coefficients were measured using a FOX 314 Heat Flow Meter in accordance with ASTM C-518 [

30]. A constant temperature gradient was established by setting the cold and hot plates to 10°C and 30°C, respectively. Specimens (100×100×10 mm) were tested within an insulated guard area to minimize edge heat losses.

2.5.2. Mechanical Properties

- -

Modulus of Rupture (MOR) and Modulus of Elasticity (MOE): Three-point bending tests were performed according to TS EN 310 [

31]. The support span was set to 20 times the specimen thickness. A loading rate of approximately 4 mm/min was applied to ensure failure occurred within 60±30 seconds. The MOR was calculated based on the maximum load recorded at failure, while the MOE was determined from the slope of the linear elastic region of the load-deflection curve. Eight specimens were tested for each group.

- -

Internal Bond (IB) Strength: Tensile strength perpendicular to the board plane was assessed using 50×50 mm specimens in accordance with TS EN 319 [

32]. The tensile load was applied at a rate of 0.6 mm/min until failure. The maximum force was recorded, and the average of eight replicates was reported

2.5.3. Microstructural and Chemical Analyses

- -

FTIR: To identify functional groups and chemical bonding, FTIR analysis was conducted on powdered samples obtained from fracture surfaces. Prior to analysis, samples were dried at 80°C for 24 hours. Spectra were acquired using a Bruker Tensor 37 spectrometer equipped with an ATR module, scanning from 4000 to 400 cm⁻¹ at a resolution of 4 cm⁻¹ (32 scans).

- -

XRD: The crystallographic structure of the cured geopolymer binder was investigated using a Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer (Cu-Kα radiation). Fragments from fractured specimens were vacuum-dried at 80°C for 24 hours prior to analysis. Scans were performed over a 2θ range of 10°–100° at a rate of 0.5°/min.

- -

SEM: The morphology of the fiber-matrix interface and composite microstructure was examined using a Carl Zeiss/Gemini 300 SEM. Specimens (~1 mm³) were vacuum-dried at 60°C for 24 hours and sputter-coated with a gold-palladium layer (Leica ACE600; 20 mA, 30 s) to prevent charging.

2.5.4. Statistical Analysis

Data were statistically analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics 22 software. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed to assess the significance of differences between groups. For factors exhibiting statistical significance (p <0.05), Tukey’s multiple comparison test was applied to identify specific differences among group means

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chemical Characterization of Raw Materials

The chemical composition of the GGBFS, determined via XRF analysis, is presented in

Table 1. The slag is predominantly composed of calcium oxide (CaO), silica (SiO₂), and alumina (Al₂O₃), which collectively constitute the backbone of the geopolymer network.

The final performance of geopolymer systems is intrinsically linked to the mineralogical makeup of the precursor. As shown in

Table 1, the GGBFS used in this study possesses a naturally high Si/Al ratio. Theoretically, this favors the formation of a highly cross-linked N-A-S-H network. However, the substantial CaO content (38.5%) introduces a secondary reaction pathway upon alkaline activation, leading to a hybrid gel system where calcium-rich C-A-S-H gels coexist with N-A-S-H gels. This hybrid structure is critical; as noted by Haha et al. (2011) [

33], C-A-S-H gel typically comprises 70–75% of the binder volume in silicate-activated slags, providing rapid setting and high early-age strength, while the N-A-S-H network contributes to workability and long-term durability [

34].

In addition to the binder, the chemical constituents of the lignocellulosic reinforcements (Pine and Hemp fibers) play a decisive role in composite durability, particularly regarding their interaction with the alkaline matrix. The chemical composition of the fibers used in this study was experimentally determined and is summarized in

Table 2.

As seen in

Table 2, the pine fibers exhibit a typical softwood composition with a balanced lignin content (27.9%), which contributes to the rigidity of the fiber cell wall. However, the significant hemicellulose fraction (25.4%) necessitates the surface pretreatments applied in this study to prevent interfacial interference during geopolymerization.

Regarding the hemp fibers, although they possess a higher cellulose content (67.5%) compared to wood, the analysis revealed a notably high hemicellulose content (21.8%) and extractives (6.5%) for this specific batch. While high cellulose typically suggests superior tensile strength, the presence of these amorphous and hydrophilic constituents renders the fibers highly susceptible to water absorption. This chemical makeup is a critical factor explaining the performance limitations—specifically the dimensional instability and alkali degradation—observed in the hemp-reinforced groups discussed in subsequent sections.

3.2. Physical Properties

The physical characteristics of the produced geopolymer panels, including d, TS, WA, and thermal conductivity are summarized in

Table 3. The results reveal distinct trends driven by the type of fiber reinforcement and the applied pretreatments.

The physical characteristics of the produced geopolymer panels, d. TS, WA, and thermal conductivity are summarized in

Table 3. The results reveal distinct trends driven by the type of fiber reinforcement and the applied pretreatments. As a general overview, inorganic glass fibers increased the density and mechanical stability, whereas natural hemp fibers, despite causing a reduction in density due to their porous structure, offered significant advantages in thermal insulation properties.

3.2.1. Density

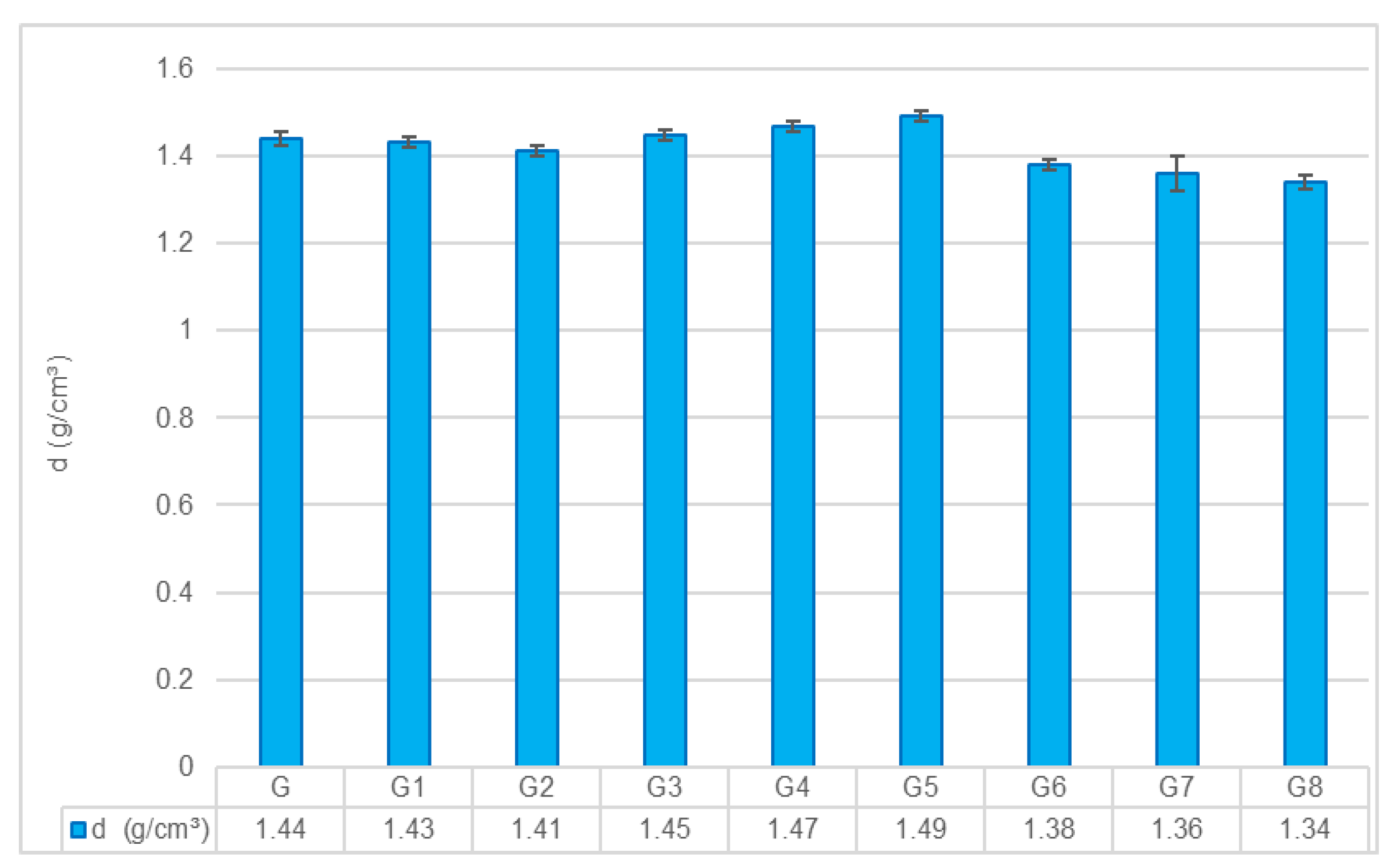

The potential of geopolymer composites as lightweight construction materials is strongly dependent on the final density, as this property directly influences both structural efficiency and handling performance. The mean density values for all groups are presented in

Figure 1.

A one-way ANOVA confirmed that the differences among groups were statistically significant (p < 0.001), indicating that both fiber type and pretreatment methods exert pronounced effects on the composite density. Tukey’s HSD post-hoc test further revealed distinct homogeneous subsets; notably, the highest-density group (G5) differed significantly from the lowest-density group (G8) (p <0.001).

The G exhibited a reference density of 1.44 g/cm³. Although the initial mix design targeted a density of 1.30 g/cm³, the experimental values ranged between 1.34 and 1.49 g/cm³. This deviation is attributed to variations in fiber dispersion within the matrix. Specifically, in natural fiber-reinforced groups, the inherent tendency of fibers to agglomerate can create micro-voids that prevent full compaction, while in glass fiber groups, the higher specific gravity of the reinforcement naturally elevates the bulk density. Similar deviations (~10%) have been reported in the literature [

8,

35], where rheological changes induced by high fiber loading were found to hinder the achievement of theoretical density targets.

Figure 1.

Variation of density values across different geopolymer composite groups (Error bars represent standard deviation).

Figure 1.

Variation of density values across different geopolymer composite groups (Error bars represent standard deviation).

Effect of Pretreatments: The G1 showed a density of 1.43 g/cm³, which was statistically indistinguishable from the Control (p = 0.999). This suggests that hot water treatment acts as a mild intervention, removing surface impurities without altering the fiber's structural integrity or the matrix compactness. In contrast, the G2 exhibited a reduced density of 1.41 g/cm³. Although the difference from the Control was not statistically significant (p = 0.332), G2 was significantly less dense than the glass fiber groups G4 and G5. This trend aligns with the "cumulative alkali degradation" hypothesis proposed in this study. The combination of the NaOH pretreatment and the highly alkaline geopolymer matrix appears to exceed the threshold for beneficial modification, triggering the dissolution of hemicellulose and the partial hydrolysis of cellulose chains. As noted by Wei and Meyer (2015) [

12], such degradation can accelerate fiber mineralization and create interfacial micro-voids, thereby reducing the overall density of the composite.

Effect of Fiber Reinforcement: GF reinforcement resulted in a monotonic increase in density, consistent with the rule of mixtures. The density rose from 1.44 g/cm³ (G3) to 1.49 g/cm³ (G5) as the fiber content increased to 9%. The G5 group was significantly denser than the Control (p = 0.003) and all natural fiber groups. This is directly attributed to the higher specific gravity of glass fibers compared to the geopolymer matrix and their ability to disperse without absorbing water from the mix.

Conversely, HF reinforcement led to a systematic reduction in density: 1.38 g/cm³ (G6), 1.36 g/cm³ (G7), and 1.34 g/cm³ (G8). All HF groups were significantly lighter than the Control (p <0.001). This "lightweighting" effect is primarily due to two factors: the naturally porous lumen structure of hemp fibers and the phenomenon of fiber agglomeration. As fiber content increased, the difficulty in achieving a homogeneous mix likely led to air entrapment within fiber bundles, fostering a more porous microstructure [

36]. While this reduction in density compromises mechanical load-bearing capacity, it offers a distinct advantage for applications requiring lighter building panels.

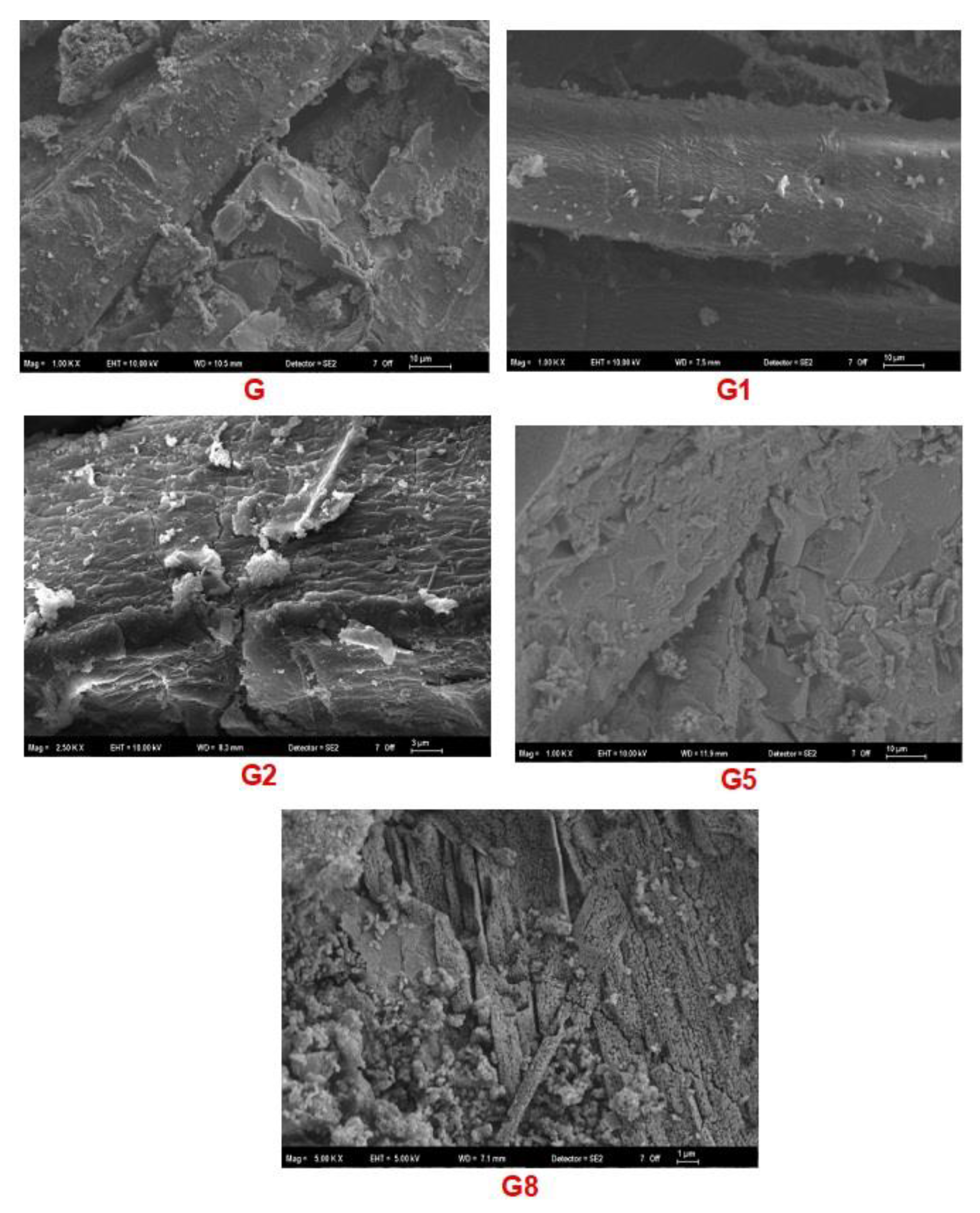

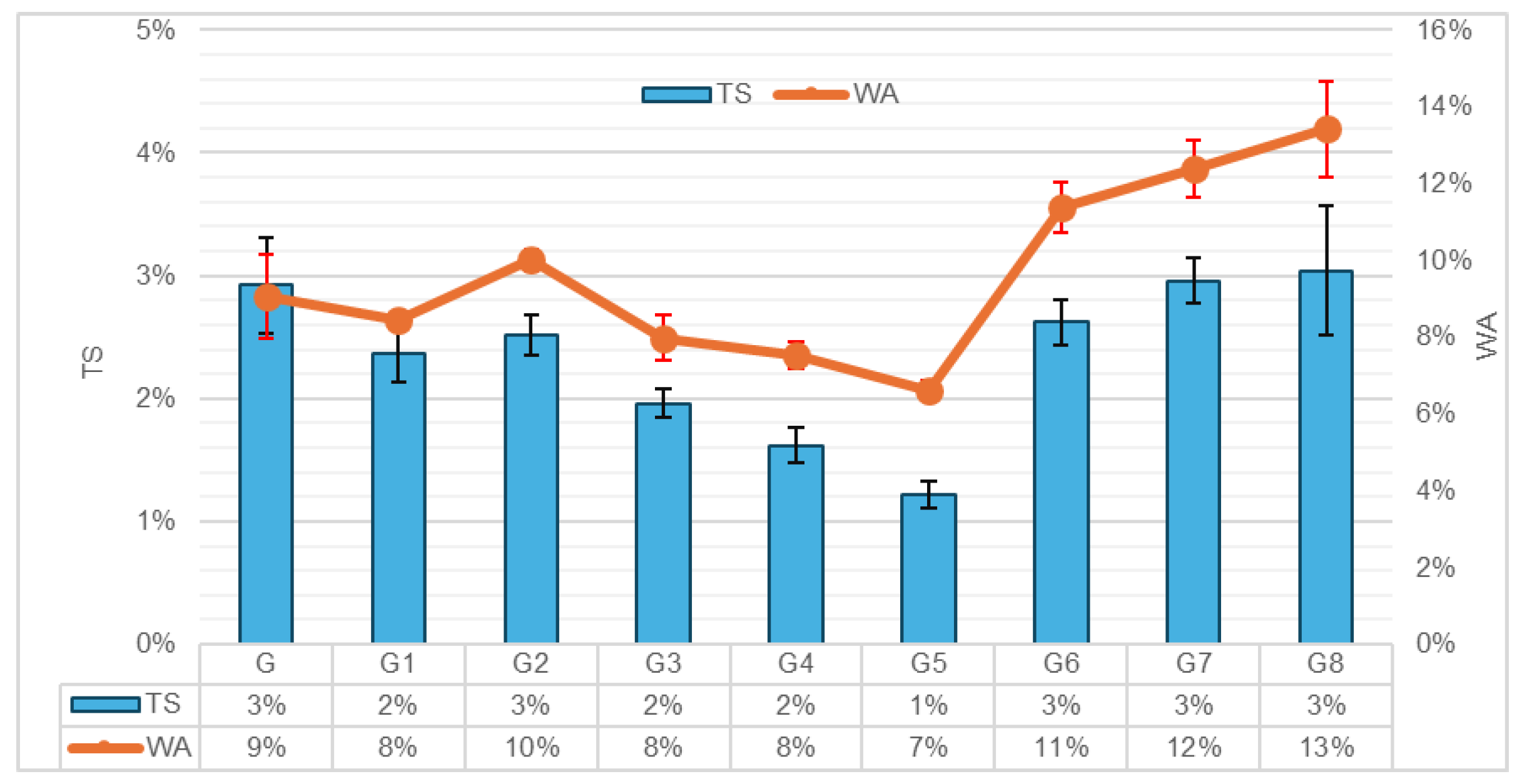

3.2.2. Dimensional Stability (Water Absorption and Thickness Swelling)

The interaction between the composite material and moisture is a defining factor for its long-term durability. The 24-hour WA and TS tests were conducted to evaluate the internal pore structure and the quality of the fiber–matrix interface. The results are summarized in

Figure 2.

The G exhibited a TS of 3.0% and WA of 9.0%, serving as the baseline. The results indicate that dimensional stability is heavily influenced by the type of reinforcement, while the effect of pretreatments remained statistically limited under the tested conditions

Effect of Pretreatments: The G1 group showed a slight improvement with 2.0% TS and 8.0% WA. However, Tukey’s post-hoc analysis revealed that these differences were not statistically significant compared to the control (p = 0.300 for TS; p = 0.905 for WA). This suggests that while hot water effectively cleans surface dust, it does not sufficiently alter the hydrophilicity of the fibers to cause a measurable shift in macro-scale dimensional stability.

Conversely, the G2 group yielded values of 3.0% TS and 10.0% WA. Although these values were statistically similar to the control (p > 0.05), the slight upward trend in water absorption corroborates the "cumulative alkali degradation" hypothesis proposed in the density analysis [

35]. The micro-structural damage and increased porosity—previously identified as the primary cause for density loss—appear to enhance the capillary network here, thereby facilitating greater water ingress.

Effect of Fiber Reinforcement: The incorporation of GF significantly enhanced moisture resistance. The G5 group achieved the best performance in the series, with TS dropping to 1.0% and WA to 7.0%. Statistical analysis confirmed significant reductions compared to the control for the G4 and G5 groups (p < 0.05). This improvement is attributed to the inorganic and non-porous nature of glass fibers. By displacing the porous matrix and creating a tortuous path for water migration, glass fibers act as an effective barrier, reducing the total capillary porosity of the composite [

35,

37].

In contrast, HF reinforcement resulted in a marked increase in water absorption. The WA values rose linearly with fiber content, reaching 13.0% in the G8 group (p < 0.001 compared to G). This behavior is driven by the intrinsic hydrophilicity of natural fibers and their hollow lumen structure, which acts as a reservoir for water storage [

18]. The observed reduction in density and increased water absorption in the wood-based matrix is consistent with the findings of Duan et al., 2016 [

21]. They attributed this behavior to the inherent porosity and hydrophilic nature of the cellulosic structure, which tends to retain moisture within the lumen channels despite the dense geopolymer network. Furthermore, the fiber agglomeration observed in the density analysis likely introduced macro-voids, creating an interconnected pore network that accelerates water uptake.

Interestingly, while WA increased significantly in hemp groups, the TS remained statistically unchanged compared to the control (p > 0.05 for G6–G8). This decoupling of absorption and swelling can be explained by the rigidity of the geopolymer matrix [

38]. While water successfully infiltrated the lumens and interfacial voids (increasing WA), the stiff geopolymer network likely constrained the fibers, preventing the physical expansion (swelling) that is typical in more flexible polymer matrices. Nevertheless, the high-water absorption in HF groups highlights the necessity for surface coatings or hydrophobic sealants if these biocomposites are intended for outdoor applications.

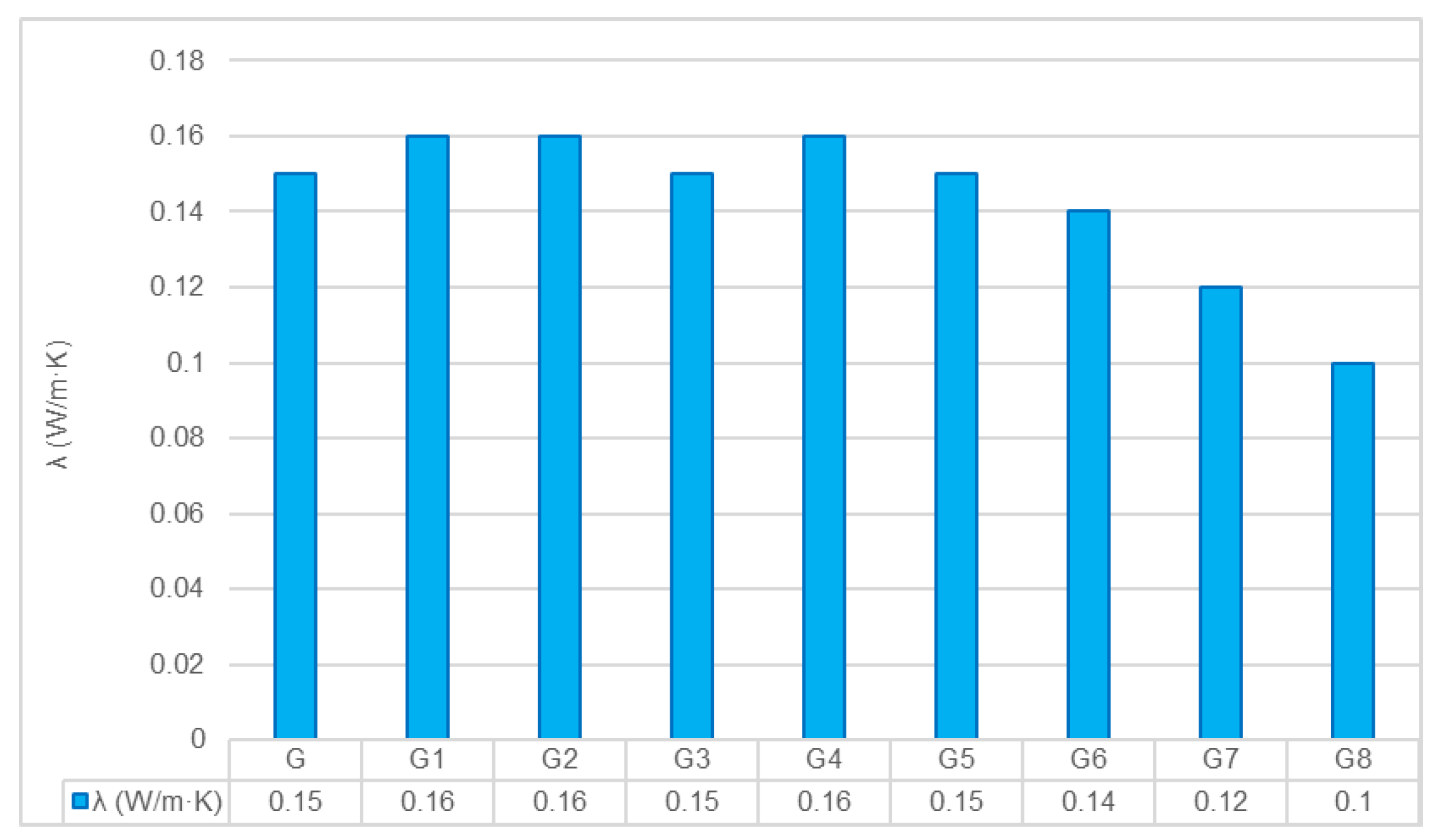

3.2.3. Thermal Conductivity (λ)

Energy efficiency in buildings is directly linked to the thermal insulation capacity of the construction materials used. In this study, the thermal conductivity of the geopolymer composites was evaluated to determine their potential as insulating panels. The results, presented in

Figure 3, highlight a clear divergence in performance driven by the reinforcement type.

Effect of Fiber Reinforcement: The most remarkable finding is the systematic improvement in insulation properties with the addition of HF. The thermal conductivity decreased linearly as the HF content increased, reaching a minimum of 0.10 W/m·K in the G8 group. This represents a substantial 33% reduction compared to the control matrix (0.15 W/m·K).

This enhancement is directly linked to the density reduction and porosity increase discussed in

Section 3.2.1. Lignocellulosic hemp fibers possess a hierarchical structure containing a hollow lumen filled with stagnant air. Since air has an extremely low thermal conductivity (~0.026 W/m·K), these fibers effectively introduce millions of insulating micro-pockets into the matrix. Furthermore, the macro-voids created by fiber agglomeration act as additional barriers to heat flux. This mechanism—where the introduction of porous bio-fillers disrupts the conductive path of the geopolymer matrix—is well-supported by recent studies on agricultural waste-based geopolymers [

35,

39].

In contrast, the inclusion of GF resulted in values ranging between 0.15 and 0.16 W/m·K, showing no improvement over the control. Unlike hemp, glass fibers are solid, dense, and inorganic materials with higher intrinsic thermal conductivity. Consequently, they facilitate heat transfer via solid-state conduction rather than impeding it. This stark contrast demonstrates that for applications where thermal insulation is the primary objective, porous natural fibers are structurally superior to dense synthetic reinforcements.

Effect of Pretreatments: An interesting observation is that both the G1 and G2 treated groups exhibited a slight increase in thermal conductivity (0.16 W/m·K) compared to the control (0.15 W/m·K). While this might initially seem contradictory to the density loss observed in the G2 group, it can be explained by the modification of the fiber–matrix interface.

Pretreatments remove surface impurities such as waxes and dust, allowing the geopolymer paste to wet the fiber surface more effectively. This improved physical contact reduces the "interfacial thermal resistance" (also known as Kapitza resistance), creating a more continuous bridge for heat flow (phonons) between the matrix and the fiber [

40]. Additionally, in the case of the G2 group, the "alkali degradation" discussed earlier likely led to the partial mineralization of the fiber walls. As the organic cellulose structure degrades and is infiltrated by geopolymer ions (Si, Al), the fiber becomes more conductive (ceramic-like) compared to a raw, air-filled organic fiber. Thus, while degradation reduces bulk density by creating voids, the remaining mineralized interface conducts heat slightly more efficiently than the control.

3.2.4. Mechanical Properties (MOE, MOR, and IB)

The mechanical performance of the composites, characterized by MOE, MOR, and IB strength, is presented in

Table 4. These parameters are critical for determining the structural suitability of the panels.

The results reveal a distinct dichotomy between the reinforcement types. While glass fibers reinforced the matrix, hemp fibers led to a reduction in mechanical strength, highlighting a clear trade-off between thermal insulation and load-bearing capacity.

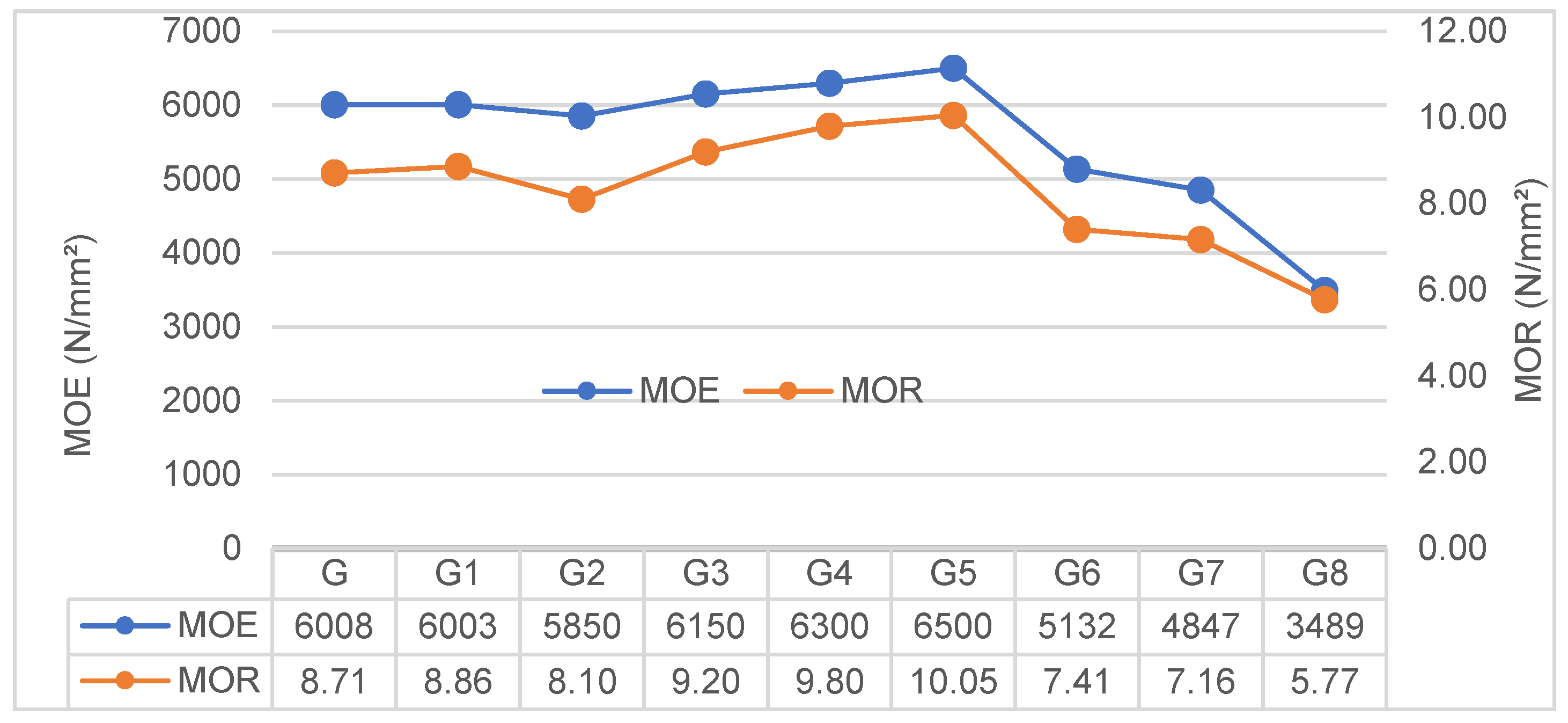

3.2.5. Flexural Performance (MOR and MOE)

The flexural behavior of the composites, characterized by MOR and MOE, is presented in

Figure 4. Since both parameters are intrinsically linked to the fiber-matrix interaction and microstructural integrity, they exhibited nearly identical trends across all code groups.

Effect of Pretreatments: The G established baseline values of 8.71 N/mm² for MOR and 6008 N/mm² for MOE. The G1 group resulted in no statistically significant deviation (p > 0.05 for both metrics), indicating that the removal of mild surface impurities with hot water was insufficient to alter the bulk mechanical stiffness or strength.

Conversely, the G2 group displayed a consistent decline, with MOR dropping to 8.10 N/mm² and MOE to 5850 N/mm². This mechanical loss directly corroborates the physical degradation observed in the previous sections. The "double alkali effect," which was identified as the cause of density loss and increased porosity, evidently compromised the intrinsic structural integrity of the fibers as well. It appears that the aggressive chemical attack went beyond surface modification, damaging the cellulose backbone and reducing the fiber's tensile capacity. This phenomenon aligns with the degradation mechanism described by Mohr et al. (2005) [

41], where high alkalinity is shown to decompose the hemicellulose and lignin, leading to fiber embrittlement.

Effect of Fiber Reinforcement: The introduction of fibers created a clear bifurcation in mechanical performance, strictly dependent on the fiber type.

Glass fiber reinforcement (G3–G5) effectively transformed the brittle geopolymer matrix into a more structural composite. The SEM observations for the GF-containing specimens (

Figure 8, G5) indicate a more compact fiber–matrix contact with fewer interfacial voids, which is consistent with improved stress transfer and crack-bridging efficiency compared with the control. The peak performance observed in G5 (MOR: 10.05 N/mm², MOE: 6500 N/mm²) can be attributed to synergistic mechanisms. First, the stiffness enhancement follows the rule of mixtures [

42], as high-modulus glass fibers carry a larger portion of the applied load. In addition, under highly alkaline conditions, partial activation of the glass fiber surface is plausible, which may promote the formation of a denser interfacial region and further enhance load transfer, delaying premature failure.

In stark contrast, the inclusion of Hemp Fiber (G6–G8) induced a precipitous drop in mechanical capacity, with the G8 group losing nearly 42% of its stiffness compared to the control. This degradation extends beyond the naturally lower stiffness of organic fibers; it is a structural consequence of the "porosity-strength trade-off." The agglomeration issues identified in the physical analysis here manifest as mechanical flaws: the fiber clusters act as stress concentrators rather than reinforcements [

43]. Consequently, the material behaves less like a dense solid and more like a cellular solid. While this porous architecture severely limits load-bearing capacity, it is the exact feature responsible for the superior thermal insulation (0.10 W/m·K) reported earlier. Thus, the mechanical loss in HF groups should be interpreted not merely as a failure, but as the functional cost of achieving high thermal resistance.

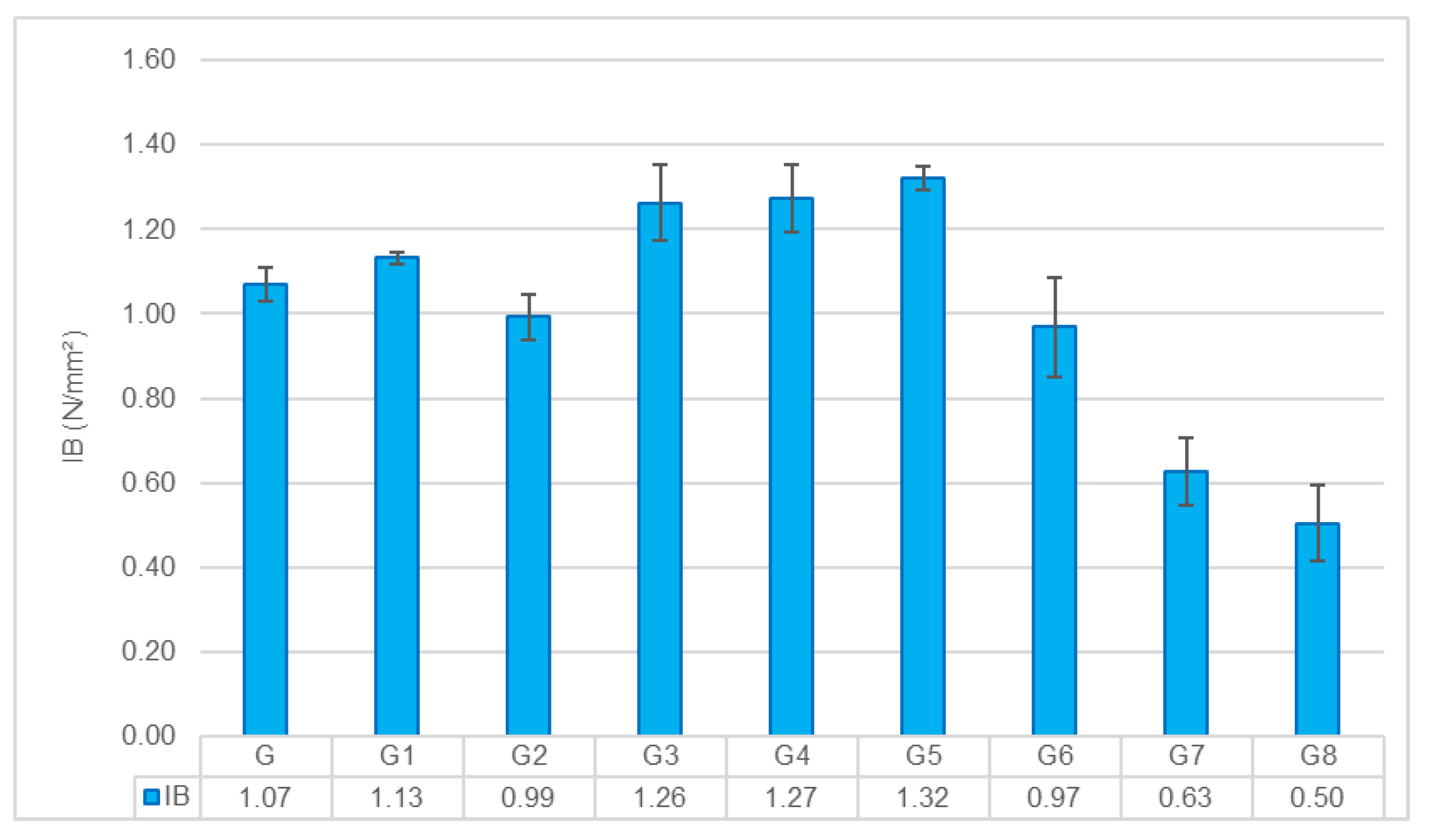

3.2.4.3. Internal Bond (IB) Strength

The IB strength acts as a litmus test for the compatibility between the reinforcement and the matrix, effectively measuring how well the composite holds together under perpendicular tension. The results in

Figure 5 reveal a stark divergence in performance, dictated largely by interfacial chemistry and physical packing.

Effect of Pretreatments: The Control group set a baseline of 1.07 N/mm². Interestingly, the G1 group provided a modest boost, raising the value to 1.13 N/mm². This suggests that simply washing away surface waxes and pectins improved the fiber's "wettability," allowing the geopolymer paste to penetrate surface micro-roughness and mechanically interlock more effectively [

44].

Conversely, the G2 group displayed a decline to 0.99 N/mm². This drop mirrors the trends seen in the flexural tests and reinforces the "double alkali degradation" hypothesis. The aggressive alkali attack likely rendered the fiber surface friable, creating a "weak boundary layer" rather than a strong interface. Instead of transferring stress, this damaged outer layer likely peeled off under tension, leading to premature failure. This phenomenon is consistent with observations in cementitious composites, where excessive alkalization degrades the fiber cell wall, weakening the fiber-matrix transition zone [

45].

Effect of Fiber Reinforcement: The fiber type created a clear bifurcation in internal cohesion. Glass Fiber reinforcement (G3–G5) demonstrated superior performance, peaking at 1.32 N/mm² in the G5 group. This robust bonding is not coincidental; it stems from the natural chemical affinity between the silica-rich glass surface and the aluminosilicate matrix. The high alkalinity of the geopolymer likely activated the glass surface, fostering the growth of hybrid C-A-S-H gels that fused the phases together [

46]. Furthermore, the CaCl₂ surface spray likely played a synergistic role; by accelerating the setting reaction at the interface, it effectively densified the contact zone, further locking the structure together [

27].

In stark contrast, the Hemp Fiber groups (G6–G8) faced significant structural challenges. As the fiber loading increased, the internal bond strength progressively deteriorated, reaching a minimum of 0.50 N/mm² in the G8 group. This drastic drop offers a clear microstructural explanation for the material's lower mechanical capacity. The issue is primarily physical: at high volumes, hemp fibers tend to agglomerate, creating "dry clusters" that the viscous geopolymer binder cannot penetrate. These clusters act as internal flaws or voids. Without a continuous matrix to bridge these gaps, the material lacks internal unity and fails easily under tension. This difficulty in wetting and infiltrating dense natural fiber bundles is a well-documented challenge in geopolymer composites [

47,

48].

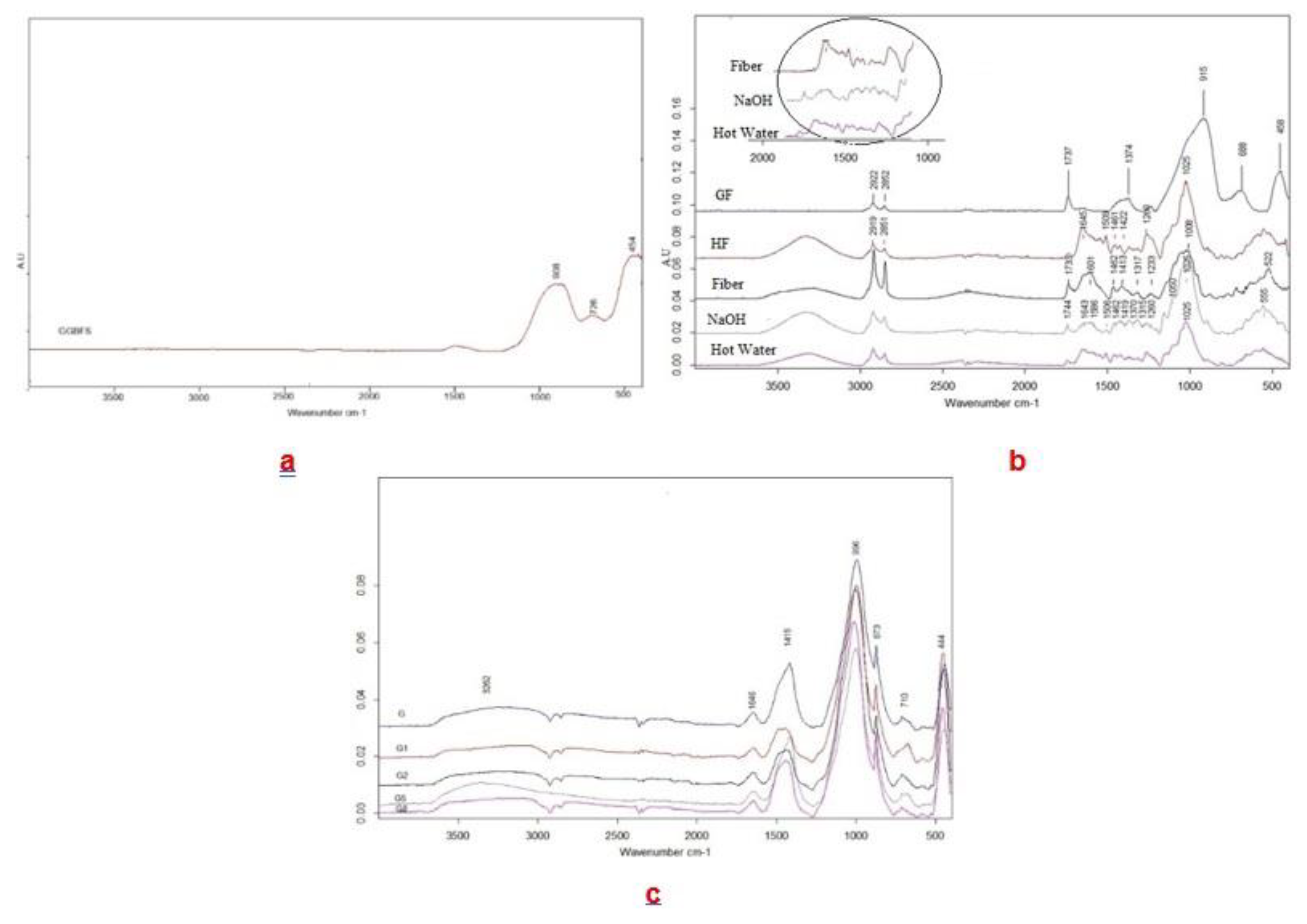

3.3. Microstructural Characterization: FTIR Analysis

FTIR was employed to provide molecular evidence underpinning the macroscopic performance observed in the physical and mechanical tests. The spectral evolution from raw precursor to final composite is detailed in

Figure 6.

Precursor Baseline: The GGBFS precursor (

Figure 6a) established the chemical baseline with a dominant band centered at 908 cm⁻¹, characteristic of the asymmetric stretching vibrations of Si–O–T (where T = Si or Al) bonds in its amorphous structure. This band serves as the primary reference point; its subsequent shift is the key indicator of the degree of geopolymerization.

Effect of Pretreatments (Figure 6b

): The impact of fiber pretreatment is clearly visible in the spectral fingerprints of the fibers. The raw hemp fiber exhibits a typical cellulosic profile, distinguished by a sharp ester carbonyl (C=O) peak at 1737 cm⁻¹, derived from hemicellulose and lignin components. The evolution of this peak offers a molecular rationale for the mechanical divergence observed between the pretreated groups.

In the NaOH-treated fibers, this peak vanishes completely. While this confirms the successful removal of non-cellulosic binders [

15], it simultaneously supports the "double alkali degradation" hypothesis proposed earlier. The aggressive stripping of these binders likely left the cellulose backbone exposed and vulnerable to further attack by the alkaline matrix, rendering the fiber surface friable and leading to the poor interfacial bonding seen in the G2 group. Conversely, the Hot Water treatment resulted in only a marginal intensity reduction of this peak, indicating a milder cleaning process. This preserved the structural integrity of the fiber while sufficiently cleaning the surface to enhance wettability, aligning with the improved performance of the G1 group.

Geopolymer Network Formation (Figure 6c): The transformation from loose precursor to hardened composite is evidenced by a definitive spectral shift. Across all groups, the main GGBFS band shifts from 908 cm⁻¹ to approximately 990–1000 cm⁻¹. This shift toward higher wavenumbers confirms the dissolution of the precursor and its re-precipitation into a more polymerized and connected aluminosilicate gel network (C-A-S-H type) [

45].

However, the quality of this gel network varied significantly depending on the reinforcement. The Glass Fiber groups (e.g., G5) displayed a clean, sharp main band, suggesting that the silica-rich glass fibers integrated seamlessly with matrix chemistry, facilitating a continuous and dense network.

In contrast, the Hemp Fiber groups (e.g., G8) exhibited broadening and intensity variations in this region. This disruption suggests a "chemical competition" mechanism. The hydrophilic nature of hemp fibers likely absorbed a portion of the activator water, locally altering the liquid-to-solid ratio and hindering the geopolymerization reaction around the fiber. Furthermore, dissolved organic compounds (such as sugars or extractives) from the natural fibers may have interfered with the nucleation of the C-A-S-H gel, a phenomenon known to retard setting and weaken the matrix structure [

48]. This molecular-level disruption explains the voids and reduced mechanical strength observed in the high-fiber composites.

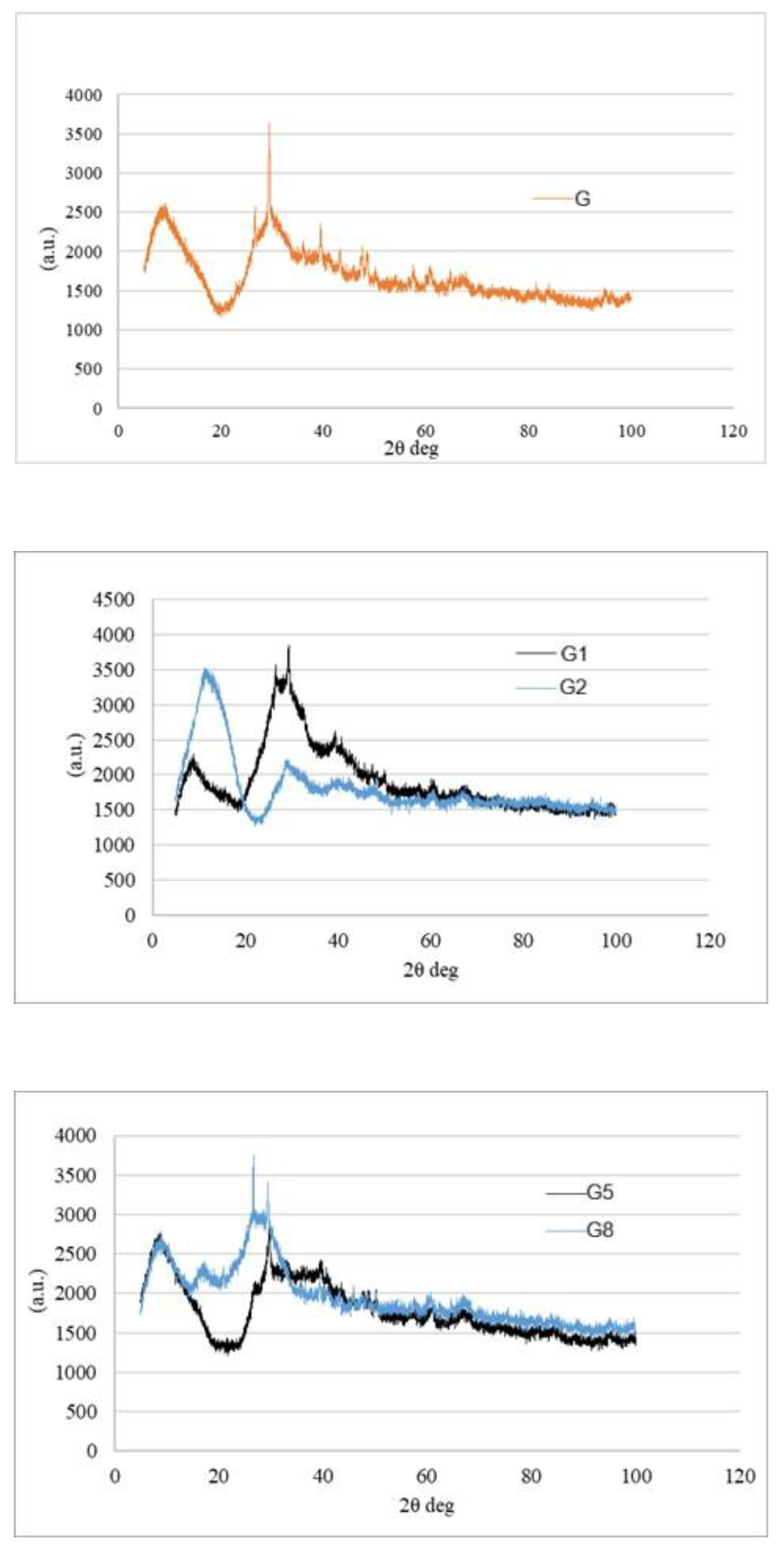

3.4. Mineralogical Characterization: XRD Analysis

X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) was employed to map the crystallographic architecture of the composites, serving as a structural cross-check for the chemical (FTIR) and mechanical findings. The diffraction patterns for all groups are presented in

Figure 7.

The unifying feature across all diffractograms is a broad, diffuse hump located between 25° and 35° (2θ). This "amorphous halo" is the signature of a successful geopolymerization, confirming that the GGBFS precursor has largely dissolved and re-precipitated into a disordered N-A-S-H or C-A-S-H gel network [

6,

7].

Effect of Pretreatments: The G and G1 groups exhibit nearly identical profiles, dominated by the amorphous geopolymer hump with minor sharp peaks attributed to residual crystalline phases (e.g., calcite or quartz) from the raw slag. The lack of new peaks in G1 confirms that the hot water treatment was a surface-level modification; it cleaned the fibers without altering the fundamental phase composition of the composite.

However, the G2 presents a distinct anomaly. Superimposed on the amorphous hump are sharp, prominent peaks at approximately 15–17° and 22–23° (2θ). These correspond to the crystalline planes of Cellulose I [

49]. Their emergence here is structurally significant. It indicates that the aggressive alkali treatment stripped away the amorphous outer layers (hemicellulose and lignin), thereby increasing the "crystallinity index" of the remaining fiber. While this suggests a purer cellulose skeleton, the sharpness of these peaks also hints at a lack of chemical integration; the fibers remain as distinct crystalline inclusions rather than participating in the geopolymer gel formation [

22].

Effect of Fiber Reinforcement: The impact of fiber type created a sharp crystallographic divergence, mirroring the mechanical results. The G5 maintained a predominantly amorphous profile, indistinguishable from the control matrix. Since glass fibers are inherently amorphous and silica-rich, they blended seamlessly into the geopolymer gel. This lack of distinct crystalline peaks is a positive indicator of homogeneity; it implies that the reinforcement and the matrix have formed a unified, continuous solid, which explains the superior load-bearing capacity (MOR/MOE) of this group [

33].

In contrast, the Hemp Fiber group (G8) mirrors the crystallographic signature of the G2 pattern, displaying the characteristic Cellulose I peaks. Here, the signal intensity is directly a function of volume and physical packing. As widely reported in natural fiber geopolymer systems, high fiber loading increases the probability of agglomeration, creating fiber bundles that the viscous binder cannot fully penetrate [

35].

These zones of "concentrated crystallinity" effectively act as interruptions in the amorphous binder. Wherever a sharp cellulose peak appears in the diffractogram, it signifies a local break in the continuous C-A-S-H gel network. Instead of a unified load-bearing matrix, the structure becomes a composite of rigid inclusions within a disrupted gel, a phenomenon known to introduce critical defects and reduce mechanical cohesion [

52]. Thus, the XRD data provides the final structural evidence for the "porosity-strength trade-off": the very features that disrupt the dense geopolymer network—crystalline cellulose clumps—are the root cause of the material's mechanical decline.

3.5. Morphological Analysis: SEM

SEM was conducted to provide the visual verification of the fiber–matrix interface and the internal microstructure. These micrographs, presented in

Figure 8, serve as the morphological proof connecting the chemical evolution (FTIR/XRD) to the macroscopic performance (Mechanical/Physical).

Figure 8.

SEM micrographs acquired in SE2 mode showing the interfacial morphology of: (G) Control, (G1) Hot-water pretreatment, (G2) Alkali pretreatment, (G5) Glass fiber reinforcement, and (G8) Hemp fiber reinforcement.

Figure 8.

SEM micrographs acquired in SE2 mode showing the interfacial morphology of: (G) Control, (G1) Hot-water pretreatment, (G2) Alkali pretreatment, (G5) Glass fiber reinforcement, and (G8) Hemp fiber reinforcement.

Effect of Pretreatments: The G micrographs reveal a baseline microstructure where the matrix appears relatively compact, yet the fiber–matrix interface is not fully optimized. Small voids and partial detachments suggest that without treatment, the natural waxes on the fiber surface hinder complete wetting by the geopolymer paste.

A subtle but critical improvement is observed in the G1 group. The fiber surfaces appear cleaner and the interface tighter compared to the control. This visual evidence supports the "enhanced wettability" hypothesis discussed earlier; by washing away water-soluble impurities like pectin, the treatment allowed the matrix to mechanically interlock more effectively with the fiber [

15]. This cleaner surface morphology explains the slight boost in IB strength observed in the mechanical tests.

In stark contrast, the G2 group exhibits signs of severe microstructural distress. The images reveal fibers with eroded surfaces, fibrillation, and significant detachment from the matrix. Large voids and cracks at the interface act as visual confirmation of the 'double alkali degradation' [

18]. The aggressive chemical attack stripped the fiber's protective layers, leaving it structurally compromised and prone to fibrillation [

53]. These wide interfacial gaps are the direct physical cause of the low density and poor load-bearing capacity recorded for this group.

Effect of Fiber Reinforcement: A significant change in morphology was observed depending on the reinforcement used. Specifically, G5 samples displayed a dense microstructure with a continuous ITZ, where the matrix completely encapsulated the glass fibers without voids. This observation confirms the chemical compatibility suggested by FTIR results and agrees with Korniejenko et al. (2016) [

54], who noted that silica-rich fibers foster a more compact geopolymer structure. The lack of voids explains why this group achieved the highest mechanical strength and water resistance; the composite behaves as a unified, monolithic solid.

Conversely, the G8 microstructure is dominated by heterogeneity. The images clearly show fiber agglomeration—clusters of fibers bundled together—surrounded by macro-voids. These 'dry clusters' prevented the viscous geopolymer paste from penetrating between individual fibers, leaving large air pockets within the composite [

35] This morphology is the visual definition of the 'porosity-strength trade-off' mentioned throughout the study. The voids seen here are responsible for the high water absorption and the material's failure to transfer stress effectively, resulting in the low MOR and MOE values [

38].

4. Conclusions

This study explored the potential of valorizing industrial GGBFS waste to produce sustainable geopolymer composites, revealing that the performance of these materials is heavily dependent on the delicate balance between matrix chemistry and reinforcement type.

One of the most significant findings concerns the fiber pretreatment methods. Contrary to the positive effects typically seen in polymer composites, aggressive NaOH pretreatment proved detrimental in this geopolymer system. Our results confirmed that the combination of alkali pretreatment and the highly alkaline geopolymer matrix leads to a "cumulative degradation" of the fibers, compromising their structural integrity rather than enhancing it. In contrast, simple hot water washing offered a mild but effective improvement by cleaning surface impurities without damaging the fiber, suggesting that less aggressive treatments are more suitable for geopolymer matrices.

Regarding the reinforcements, the study identified a clear divergence in material behavior. Glass fibers demonstrated remarkable compatibility with the geopolymer matrix; their silica-rich nature allowed them to actively participate in the geopolymerization process, creating a dense, chemically bonded structure with superior mechanical strength and water resistance. On the other hand, hemp fibers introduced a distinct trade-off. While their tendency to agglomerate and create porosity significantly reduced the load-bearing capacity, these same characteristics resulted in a material with superior thermal insulation properties.

In conclusion, this research demonstrates that GGBFS-based geopolymers are a versatile material platform.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S.A. and E.G.; methodology, E.G. and S.S.A.; validation, E.G.; formal analysis, E.G.; investigation, S.S.A.; resources, E.G.; data curation, S.S.A.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S.A.; writing—review and editing, S.S.A. and E.G.; visualization, S.S.A.; supervision, E.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript..

Funding

This research was funded by the Bursa Technical University Scientific Research Projects Coordination Unit, grant number 230D003.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the staff of the Department of Forest Industry Engineering at Bursa Technical University for their technical assistance during the experimental studies. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used AI-based tools (ChatGPT/Gemini) for English language editing and grammatical refinement. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

GGBFS: Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag

GF: Glass Fiber

HF: Hemp Fiber

NaOH: Sodium Hydroxide

Ms: Silica Modulus

D: Density

WA: Water Absorption

TS: Thickness Swelling

MOR: Modulus of Rupture

MOE: Modulus of Elasticity

IB: Internal Bond

SEM: Scanning Electron Microscopy

XRD: X-ray Diffraction

XRF: X-ray Fluorescence

FTIR: Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

References

- IPCC. Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022.

- Lehne, J.; Preston, F. Making Concrete Change: Innovation in Low-carbon Cement and Concrete; Chatham House Report; The Royal Institute of International Affairs: London, UK, 2018.

- Andrew, R.M. Global CO2 emissions from cement production. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2018, 10, 195–217.

- Mehta, P.K.; Monteiro, P.J. Concrete Microstructure, Properties, and Materials; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2006.

- Provis, J.L. Alkali-activated materials. Cem. Concr. Res. 2018, 114, 40–48. [CrossRef]

- Davidovits, J. Geopolymers: Inorganic polymeric new materials. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 1991, 37, 1633–1656. [CrossRef]

- Provis, J.L.; Bernal, S.A. Geopolymers and related alkali-activated materials. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 2014, 44, 299–327. [CrossRef]

- Ranjbar, N.; Zhang, M. Fiber-reinforced geopolymer composites: A review. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2020, 107, 103498. [CrossRef]

- Pacheco-Torgal, F.; Shasavandi, A.; Jalali, S. Eco-efficient concrete using industrial wastes: A review. Mater. Sci. Forum 2013, 730, 581–586. [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Kasal, B.; Huang, L. A review of recent research on the use of cellulosic fibres, their fibre fabric reinforced cementitious, geo-polymer and polymer composites in civil engineering. Compos. Part B Eng. 2016, 92, 94–132. [CrossRef]

- Amran, M.; Debbarma, S.; Ozbakkaloglu, T. Fly ash-based eco-friendly geopolymer concrete: A critical review of the long-term durability properties. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 270, 121857. [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Meyer, C. Degradation mechanisms of natural fiber in the matrix of cement composites. Cem. Concr. Res. 2015, 73, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Tonoli, G.H.D.; Teixeira, E.M.; Corrêa, A.C.; Marconcini, J.M.; Caixeta, L.A.; Pereira-da-Silva, M.A.; Mattoso, L.H.C. Cellulose micro/nanofibres from Eucalyptus kraft pulp: Preparation and properties. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012, 89, 80–88. [CrossRef]

- Camargo, M.M.; Taye, E.A.; Roether, J.A.; Redda, D.T.; Boccaccini, A.R. A review on natural fiber-reinforced geopolymer and cement-based composites. Materials 2020, 13, 4603. [CrossRef]

- Mwaikambo, L.Y.; Ansell, M.P. Chemical modification of hemp, sisal, jute, and kapok fibers by alkalization. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2002, 84, 2222–2234. [CrossRef]

- Venkatachalam, N.; Navaneethakrishnan, P.; Rajsekar, R.; Shankar, S. Effect of pretreatment methods on properties of natural fiber composites: A review. Polym. Polym. Compos. 2016, 24, 555–566. [CrossRef]

- Maichin, P.; Suwan, T.; Jitsangiam, P.; Chindaprasirt, P.; Fan, M. Effect of self-treatment process on properties of natural fiber-reinforced geopolymer composites. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2020, 35, 1120–1128. [CrossRef]

- Suwan, T.; Maichin, P.; Fan, M.; Jitsangiam, P.; Tangchirapat, W.; Chindaprasirt, P. Influence of alkalinity on self-treatment process of natural fiber and properties of its geopolymeric composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 316, 125817. [CrossRef]

- Lemougna, P.N.; Wang, K.T.; Tang, Q.; Nzeukou, A.N.; Billong, N.; Melo, U.C.; Cui, X.M. Review on the use of volcanic ashes for engineering applications. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 137, 177–190. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wan, Z.; Yang, X.; Lin, F.; Chen, Y.; Lu, B. Mechanochemical fabrication of geopolymer composites based on the reinforcement effect of microfibrillated cellulose. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 503–511. [CrossRef]

- Duan, P.; Yan, C.; Zhou, W.; Luo, W. Fresh properties, mechanical strength and microstructure of fly ash geopolymer paste reinforced with sawdust. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 111, 600–610. [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M.M.; Wang, H.; Lau, K.T.; Cardona, F. Chemical treatments on plant-based natural fibre reinforced polymer composites: An overview. Compos. Part B Eng. 2012, 43, 2883–2892. [CrossRef]

- Korniejenko, K.; Łach, M.; Hebdowska-Krupa, M.; Mikuła, J. Impact of flax fiber reinforcement on mechanical properties of solid and foamed geopolymer concrete. Adv. Technol. Innov. 2020, 6, 11. [CrossRef]

- Duxson, P.; Fernández-Jiménez, A.; Provis, J.L.; Lukey, G.C.; Palomo, A.; van Deventer, J.S. Geopolymer technology: The current state of the art. J. Mater. Sci. 2007, 42, 2917–2933. [CrossRef]

- TAPPI. Alpha-, Beta- and Gamma-Cellulose in Pulp; TAPPI Test Methods T 203 cm-99; TAPPI Press: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2009.

- Assaedi, H.; Alomayri, T.; Shaikh, F.; Low, I.M. Influence of nano silica particles on durability of flax fabric reinforced geopolymer composites. Materials 2019, 12, 1459. [CrossRef]

- Pan, D.; Zhang, N.; Li, J.; Ye, H.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, Y. CaCl2-induced interfacial deposition for the preparation of high-strength and flame-retardant plywood using geopolymer-based adhesive. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 33678–33686. [CrossRef]

- Turkish Standards Institution. Wood–based Panels–Determination of Density; TS EN 323; TSE: Ankara, Turkey, 1999.

- Turkish Standards Institution. Particleboards and Fibreboards—Determination of Swelling in Thickness after Immersion in Water; TS EN 317; TSE: Ankara, Turkey, 1999.

- ASTM International. Standard Test Method for Steady-State Thermal Transmission Properties by Means of the Heat Flow Meter Apparatus; ASTM C518-17; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- Turkish Standards Institution. Wood-based Panels—Determination of Modulus of Elasticity in Bending and of Bending Strength; TS EN 310; TSE: Ankara, Turkey, 1999.

- Turkish Standards Institution. Particleboards and Fibreboards—Determination of Tensile Strength Perpendicular to the Plane of the Board; TS EN 319; TSE: Ankara, Turkey, 1999.

- Haha, M.B.; Le Saout, G.; Winnefeld, F.; Lothenbach, B. Influence of activator type on hydration kinetics, hydrate assemblage and microstructural development of alkali activated blast-furnace slags. Cem. Concr. Res. 2011, 41, 301–310. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, K.; Zhang, J. A review on properties of fresh and hardened geopolymer mortar. Compos. Part B Eng. 2018, 152, 79–95. [CrossRef]

- Alomayri, T.; Shaikh, F.U.A.; Low, I.M. Synthesis and mechanical properties of cotton fabric reinforced geopolymer composites. Compos. Part B Eng. 2014, 60, 36–42. [CrossRef]

- Ku, H.; Wang, H.; Pattarachaiyakoop, N.; Trada, M. A review on the tensile properties of natural fiber reinforced polymer composites. Compos. Part B Eng. 2011, 42, 856–873. [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Ahmari, S.; Zhang, L. Utilization of sweet sorghum fiber to reinforce fly ash-based geopolymer. J. Mater. Sci. 2014, 49, 2548–2558. [CrossRef]

- Wongsa, A.; Sata, V.; Nematollahi, B.; Sanjayan, J.; Chindaprasirt, P. Mechanical and thermal properties of lightweight geopolymer mortar incorporating crumb rubber. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 195, 1069–1080. [CrossRef]

- Duan, P.; Song, L.; Yan, C.; Ren, D.; Li, Z. Novel thermal insulating and lightweight composites from metakaolin geopolymer and polystyrene particles. Ceram. Int. 2017, 43, 5115–5120. [CrossRef]

- Burger, N.; Laachachi, A.; Ferriol, M.; Lutz, M.; Toniazzo, V.; Ruch, D. Review of thermal conductivity in composites: Mechanisms, parameters and theory. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2016, 61, 1–28. [CrossRef]

- Mohr, B.J.; Nanko, H.; Kurtis, K.E. Durability of kraft pulp fiber–cement composites to wet/dry cycling. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2005, 27, 435–448. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, B.D.; Broutman, L.J.; Chandrashekhara, K. Analysis and Performance of Fiber Composites; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017.

- Assaedi, H.; Shaikh, F.U.A.; Low, I.M. Characterizations of flax fabric reinforced nanoclay-geopolymer composites. Compos. Part B Eng. 2016, 95, 412–422. [CrossRef]

- Bledzki, A.K.; Gassan, J. Composites reinforced with cellulose based fibres. Prog. Polym. Sci. 1999, 24, 221–274.

- Savastano Jr, H.; Santos, S.F.D.; Radonjic, M.; Soboyejo, W.O. Fracture and fatigue of natural fiber-reinforced cementitious composites. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2009, 31, 232–243. [CrossRef]

- Bernal, S.A.; De Gutiérrez, R.M.; Provis, J.L. Engineering and durability properties of concretes based on alkali-activated granulated blast furnace slag/metakaolin blends. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 33, 99–108. [CrossRef]

- Alzeer, M.; MacKenzie, K. Synthesis and mechanical properties of novel composites of inorganic polymers (geopolymers) with unidirectional natural flax fibres (Phormium tenax). Appl. Clay Sci. 2013, 75, 148–152. [CrossRef]

- Thakur, V.K.; Singha, A.S. Physico-chemical and mechanical characterization of natural fibre reinforced polymer composites. Mater. Phys. Mech. 2010, 10, 3–10.

- Bernal, S.A.; Provis, J.L.; Rose, V.; De Gutierrez, R.M. Evolution of binder structure in sodium silicate-activated slag-metakaolin blends. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2011, 33, 46–54. [CrossRef]

- Sedan, D.; Pagnoux, C.; Smith, A.; Chotard, T. Mechanical properties of hemp fibre reinforced cement: Influence of the fibre/matrix interaction. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2008, 28, 183–192. [CrossRef]

- French, A.D. Idealized powder diffraction patterns for cellulose polymorphs. Cellulose 2014, 21, 885–896. [CrossRef]

- Lazorenko, G.; Kasprzhitskii, A.; Kruglikov, A.; Mischinenko, V.; Yavna, V. Sustainable geopolymer composites reinforced with flax tows. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 12870–12875. [CrossRef]

- Pickering, K.L.; Efendy, M.A.; Le, T.M. A review of recent developments in natural fibre composites and their mechanical performance. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2016, 83, 98–112. [CrossRef]

- Korniejenko, K.; Frączek, E.; Pytlak, E.; Adamski, M. Mechanical properties of geopolymer composites reinforced with natural fibers. Procedia Eng. 2016, 151, 388–393. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).