1. Introduction

Saline–alkaline soils rank among the most widespread forms of land degradation worldwide. Globally, soil salinization renders 1.5 × 10⁶ hectares of land unfit for crop cultivation[

1]. Particularly in China, such soils are widely distributed across several provinces in Northwest, Northeast, North and Central China, with saline-alkaline land having agricultural development potential accounting for over 10% of the country's total cultivated area [

2].

As arable land keeps shrinking and the population grows, the efficient use of saline–alkaline soils has become a key route to safeguarding global food security.

As a new strain of wheat independently developed by Hebei Province, Jiemai19 was selected as a leading wheat variety in the province in 2022. It yields over 250 kilograms per mu in saline-alkali soils, is drought- and saline-tolerant, and easy to manage, making it a key variety for boosting agricultural efficiency in saline-alkali regions such as the Bohai Bay area.

Drip irrigation, as a precision irrigation technology, can achieve water savings of 30–50% while significantly improving fertilizer-use efficiency. For crops such as cotton, sugarcane and tomato, fertilizer savings of 25–60 % have been reported [

3].

More importantly, drip irrigation creates a localized wetted bulb beneath the emitter, driving salts downward with the water and achieving optimal leaching at a soil matric potential of –5 kPa.[

4] Salt leaching was most pronounced 15 cm from the emitter within the 0–30 cm soil layer.[

5]. Field experiments further demonstrated that drip irrigation can reduce soil salinity in the 0–20 cm layer of moderately to severely saline coastal soils [

6].

Drip irrigation also significantly improves soil physicochemical properties[

7]. Experimental data show that drip irrigation increases soil organic matter and available nitrogen content by 6–8 % in the 10–20 cm soil layer.[

8]; At the microbial level, drip irrigation significantly enhanced the α-diversity of bacteria and fungi (Shannon and Simpson indices), with shallow-buried drip irrigation (5 cm) yielding the highest number of bacterial OTUs [

9]. This indicates that this method is more conducive to maintaining and enhancing microbial diversity.

Beta-diversity analysis of maize drip-irrigation trials revealed that deep-buried drip (25 cm) separates distinctly from shallow-buried drip and the control in community structure, demonstrating that burial depth regulates microbial assemblages. This indicates deep-buried drip creates a unique micro-environment that reshapes the microbial community [

9]. Functional-gene prediction further revealed that deep-buried drip irrigation significantly enriches genes linked to nitrogen cycling (e.g., nitrate respiration, nitrogen respiration), whereas shallow-buried drip favors genes for aerobic heterotrophic metabolism, indicating that burial-depth differences drive divergent microbial functional traits.[

10]. In addition to salt leaching, drip irrigation also significantly improves soil physicochemical properties[

11]. Experimental data show that drip irrigation increases soil organic matter and available nitrogen content by 6–8% in the 10–20 cm soil layer[

12]. At the microbial level, soil microorganisms play a key role in nutrient cycling, organic matter decomposition, and plant stress resistance, and their community structure and function are highly sensitive to soil environmental changes[

13]. Drip irrigation has been shown to significantly enhance the α-diversity of bacteria and fungi (Shannon and Simpson indices), with shallow-buried drip irrigation (5 cm) yielding the highest number of bacterial OTUs[

14], indicating that this method is more conducive to maintaining and enhancing microbial diversity. Beta-diversity analysis of maize drip-irrigation trials revealed that deep-buried drip (25 cm) separates distinctly from shallow-buried drip and the control in community structure, demonstrating that burial depth regulates microbial assemblages[

15]. This indicates deep-buried drip creates a unique micro-environment that reshapes the microbial community. Functional-gene prediction further revealed that deep-buried drip irrigation significantly enriches genes linked to nitrogen cycling (e.g., nitrate respiration, nitrogen respiration), whereas shallow-buried drip favors genes for aerobic heterotrophic metabolism, indicating that burial-depth differences drive divergent microbial functional traits [

16].

Despite extensive research on drip irrigation, salt-alkali reclamation, and salt-tolerant wheat, existing studies still have limitations: most focus on a single factor (soil salinity or crop yield) without integrating the soil–microbe–crop continuum [

17]; the majority are short-term (≤ 2 yr) experiments that cannot capture the long-term ameliorative effects of drip[

18]; and the mechanisms by which different burial depths reshape microbial communities to alter soil functions and crop productivity are still unclear.

Moreover, few studies have systematically compared the effects of shallow-buried (5 cm) and deep-buried (25 cm) drip irrigation on the soil microbial community structure and yield of Jiemai19 in coastal saline-alkaline soils. Although numerous studies have addressed drip irrigation, salt-alkali reclamation and salt-tolerant wheat, they remain fragmentary: most focus on a single factor (soil salinity or crop yield) without integrating the soil–microbe–crop continuum; the majority are short-term (≤ 2 yr) experiments that cannot capture the long-term ameliorative effects of drip; and the mechanisms by which different burial depths reshape microbial communities to alter soil functions are still unclear. Therefore, we established three treatments—subsurface drip at 25 cm, shallow drip at 5 cm, and a non-irrigated control—coupled with high-throughput 16S/ITS sequencing, functional-gene prediction (KEGG, CAZy) and comprehensive soil physicochemical analyses to systematically elucidate how drip depth affects the saline–alkali soil–microbe–dryland wheat system, providing both theoretical insights and technical guidance for efficient production of dryland salt-tolerant wheat on saline.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview of the Experimental Area

The experimental area is located in Lizicha Village, Changguo Town, Huanghua City, Cangzhou City, Hebei Province. The geographical coordinates refer to the central coordinates of the enterprise in the village as 117°15'08.94" E and 38°16'17.29" N, with the average altitude of Changguo Town (where it belongs) being approximately **8 meters. This area belongs to a warm temperate semi-humid monsoon climate, slightly with marine climate characteristics. The average annual temperature is 12.9℃, the average annual precipitation is 567.8mm, and the average annual evaporation is 1500-2000mm. There is no precise exclusive data on the accumulated temperature ≥10℃; referring to the active accumulated temperature above 0℃ in Huanghua City, which is about 4766℃, it can indirectly reflect that its heat conditions are suitable for the cultivation of dry alkali wheat and other crops in this area. The soil physicochemical properties (pre-experiment background values) are as follows:

Table 1.

Background values of soil physicochemical properties in different soil layers before the experiment.

Table 1.

Background values of soil physicochemical properties in different soil layers before the experiment.

| Soil depth |

pH |

EC ms cm-1 |

Salt content% |

| 0~20cm |

6.61 |

15.12 |

1.41 |

| 20~40cm |

6.8 |

9.06 |

0.56 |

2.2. Experimental Design

The experimental subject was the dryland saline-alkaline wheat cultivar “Jiemale 19”, whose growth period runs from mid- to late October to early June of the following year; the row spacing was set at 20 cm. Two irrigation methods were tested: shallow-buried drip (T5) and subsurface drip (T25), with the drip laterals buried at 5 cm and 25 cm depth, respectively. The lateral spacing was 60 cm (one lateral served three wheat rows), the emitter spacing was 20 cm, and the emitter discharge ranged from 2.5 to 3.0 L h⁻¹. Each treatment was replicated three times. Irrigation was scheduled at five critical growth stages (regreening, jointing, heading, flowering, and filling), giving a total of five irrigations, each applying 40 mm of water.

2.3. Determination Indicators and Methods

In this section, where applicable, authors are required to disclose details of how generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) has been used in this paper (e.g., to generate text, data, or graphics, or to assist in study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation). The use of GenAI for superficial text editing (e.g., grammar, spelling, punctuation, and formatting) does not need to be declared.

2.3.1. Determination of Soil Physicochemical Properties

Soil samples were collected after the harvest of dryland saline-alkaline wheat. Representative sampling points were selected in each experimental plot, and soil samples from the 0–40 cm layer were taken at each sampling point. The determined indicators are as follows:

Soil electrical conductivity (EC): Determined in accordance with the national standard Method for Determination of Soil Electrical Conductivity (Electrode Method) (HJ 802-2016). Briefly, 20.00 g of air-dried soil sample passed through a 2 mm sieve was weighed, and experimental water (electrical conductivity ≤ 0.2 mS/m) at 20±1℃ was added at a soil-to-water ratio of 5:1. After oscillating for 30 min and standing for filtration, the electrical conductivity of the filtrate was measured using a calibrated conductivity meter at 25±1℃.

Soil pH: Determined in accordance with the national standard Method for Determination of Soil pH (HJ 962-2018). Using the same soil-water suspension prepared for EC determination (soil-to-water ratio 5:1), the pH value was measured with a calibrated pH meter after standing for an additional 10 min to ensure the suspension was stable.

Soil organic matter: Determined by the potassium dichromate oxidation-external heating method.

Total nitrogen (AN): Determined by the Kjeldahl method.

Total potassium (AK): Determined by the sodium hydroxide melting-flame photometry method. Briefly, 0.20 g of air-dried soil sample passed through a 0.15 mm sieve was weighed into a nickel crucible, mixed with 2.0 g of anhydrous sodium hydroxide, and melted at 720℃ for 15 min. After cooling, the melted product was leached with hot water, transferred to a 100 mL volumetric flask, and diluted to the mark with deionized water. The total potassium content was measured using a flame photometer after filtration.

2.3.2. Collection of Rhizosphere Soil Samples

Samples were collected after the harvest of dryland saline-alkaline wheat. Representative sampling points were selected in each experimental plot using the five-point sampling method. At each sampling point, healthy plants with consistent growth status were chosen. After carefully excavating the plants with their roots intact, debris such as litter and gravel mixed on the plant surface was removed. The loosely attached non-rhizosphere soil around the roots was gently shaken off, and the soil tightly adhering to the root surface was scraped off using a sterile brush sterilized by autoclaving, which was designated as the rhizosphere soil sample. The soil samples from the five points were mixed to a total weight of approximately 200 g, placed into sterile centrifuge tubes, quickly frozen with dry ice, and transported to the laboratory within 48 hours for DNA extraction. Repeated freezing and thawing were avoided during transportation and storage to prevent alterations to the microbial community structure. A total of three treatment groups were set up in this study: CK group (control group, no irrigation), T5 group (shallow-buried drip irrigation, burial depth of 5 cm), and T25 group (deep-buried drip irrigation, burial depth of 25 cm). Each group included three biological replicates, resulting in 9 rhizosphere soil samples in total.

2.3.3. Soil Microbial DNA Extraction and High-Throughput Sequencing

Total soil microbial DNA was extracted using the Solar bio D2600 Soil Genomic DNA Extraction Kit, with strict adherence to the kit’s instructions. Briefly, 0.25 g of frozen soil sample was weighed, and microbial cells were mechanically disrupted using grinding beads. Humic acid and other impurities in the soil were removed using the humus adsorption material provided with the kit, and finally, DNA was eluted with 30 μL of elution buffer.

The integrity of DNA fragments was detected by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, and the purity of DNA was determined using a Nanodrop 2000 spectrophotometer. The OD₂₆₀/OD₂₈₀ ratio was controlled within the range of 1.8–2.0 to ensure that the DNA quality met the requirements for subsequent PCR amplification.

For the V3-V4 variable region of the 16S rRNA gene in bacterial communities, PCR amplification was performed using specific primers (forward primer F: ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCA; reverse primer R: GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT). After verifying the amplified products by agarose gel electrophoresis, purification was carried out using the magnetic bead method. The concentration of the products was determined by fluorescence quantification, and the purified amplified products were normalized to construct a sequencing library. After passing quality inspection, the library was subjected to paired-end high-throughput sequencing on the Illumina Novases 6000 sequencing platform to obtain raw sequencing reads (Raw Reads).

2.3.4. Bioinformatics Analysis

α-diversity analysis: α-diversity indices of each sample were calculated using QIIME2 v2022.8 software, including Chao1 index and ACE index (characterizing species richness), as well as Shannon index and Simpson index (characterizing species diversity). Meanwhile, phylogenetic diversity (PD_whole_tree) and coverage were statistically analyzed. Shannon rarefaction curves and OTU Venn diagrams were plotted to verify the sufficiency of sequencing depth and show the OTU distribution characteristics of each group. Significant differences in α-diversity among groups were analyzed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test (p<0.05).

β-diversity analysis: Based on the Bray-Curtis distance matrix, principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) and non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) were performed using R language v4.2.2 (vegan package) to intuitively display the differences in bacterial community structure under different treatments. The significance of differences in community structure among groups was verified by Anosim test (p<0.05). Redundancy analysis (RDA) was used to explore the correlation between microbial communities at the phylum and genus levels and soil physicochemical factors (EC, AK, AN, OC, pH), so as to identify the core environmental factors driving community differentiation.

Species composition analysis: Using the Silva database (Release 138) as a reference, taxonomic annotation of effective sequences was conducted by alignment method to obtain species annotation information at the phylum and genus levels. The top 10 dominant taxa at the phylum level and the top 15 dominant taxa at the genus level in relative abundance were selected, and stacked bar charts of community structure at the phylum and genus levels were plotted to clarify the distribution characteristics of dominant bacterial taxa under different drip irrigation treatments.

LEfSe analysis (LDA effect size threshold set to 4, p-value threshold set to 0.05) was used to screen for biomarkers with statistical differences among groups. STAMP software was used to perform significance difference tests between pairwise samples (G-TEST for large samples and Fisher test for small samples), and the abundance ratios of differential species were visually displayed.

Correlation heatmap analysis between microbial taxa and environmental factors:

Spearman rank correlation coefficient was used to calculate the correlation between microbial taxa at the phylum and genus levels and soil physicochemical factors (EC, AK, AN, OC, pH), and the significant correlation levels were marked by statistical tests. Hierarchical clustering of microbial taxa and environmental factors was performed, and a correlation heatmap was drawn to show the positive and negative strength of correlation coefficients through color gradients.

Functional prediction analysis: The FAPROTAX database (v1.1) was used for ecological function annotation of bacterial communities. This database realizes the prediction of carbon and nitrogen cycle-related functions by associating cultivable microbial taxa (genus level) with verified element cycle functions. Taking the genus-level species relative abundance table (annotated by Silva 138 database) obtained from 16S rRNA gene sequencing as input, the species-function mapping was completed using the supporting script of FAPROTAX to generate a functional relative abundance table. Differences in functions among groups were analyzed using the Wilcox rank-sum test, and p-values were corrected by FDR. The criterion for determining significant differences was corrected p<0.05 and 95% confidence interval not crossing 0. The results were displayed by functional proportion bar charts and difference confidence interval charts.

Actual yield: Harvest the middle 3 rows of each plot, measure the row length to calculate the harvested area, thresh and remove impurities immediately, determine grain moisture content with a calibrated tester, and convert to 13% standard moisture content for yield calculation. Yield components: Randomly select 30 uniform plants, separate into glume, stem, and grain fractions, deactivation at 105℃ for 30 min and dry to constant weight at 65℃ for biomass determination; measure 1000-grain weight with 3 replicates of pure dried grains, re-test if replicate weight difference exceeds 3%, and take the average.

2.4. Data Processing and Analysis

Data collation was performed using Excel 2019. Analysis of variance (ANOVA), multiple comparisons (Duncan’s method), and correlation analysis were conducted with SPSS 26.0. Graph plotting was completed by Origin 2021. Microbial community analysis was carried out using R language (with vegan and ggplot2 packages), and redundancy analysis (RDA) was applied to explore the relationship between environmental factors and microbial communities.

3. Results

3.1. Effects of Different Drip Irrigation Burial Depths on Soil Physicochemical Properties

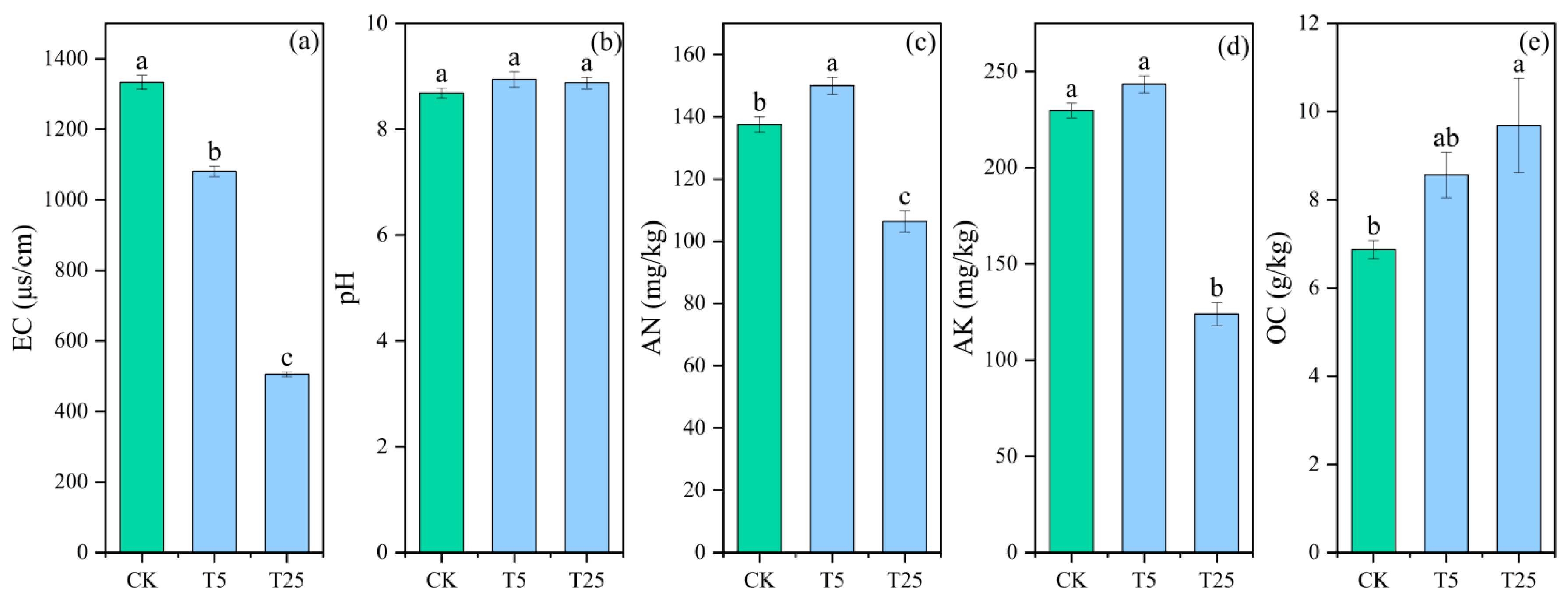

The variation trends of soil salinity (EC) and pH are shown in

Figure 1. Different drip irrigation burial depth treatments had a significant effect on soil EC values, but no significant effect on pH values. Compared with the CK group, both T25 and T5 treatments significantly reduced soil EC values, and the reduction effect became increasingly obvious with the progression of the growing season. After harvest, the average EC value in the 0–60 cm soil layer of the T25 treatment was 61.5% lower than that of the CK group, with no significant change in pH value; the average EC value in the 0–60 cm soil layer of the T5 treatment was 15.4% lower than that of the CK group, and there was no significant change in pH value. These results indicated that the subsurface drip irrigation treatment at a burial depth of 25 cm had a significantly better effect on reducing soil salinity than the shallow-buried drip irrigation treatment at 5 cm. In addition, drip irrigation treatments exhibited differential effects on soil nutrients: the soil organic matter content in the T25 treatment was 53.8% higher than that in the CK group, while the total nitrogen content was 28.6% lower and the total potassium content was 41.7% lower than those in the CK group; the soil organic matter content in the T5 treatment was 30.8% higher than that in the CK group, the total nitrogen content was 14.3% higher, and the total potassium content was 4.2% higher than those in the CK group. It should be noted that although the total nitrogen and total potassium contents in the T25 treatment were lower than those in the T5 treatment, the enrichment of nitrogen cycling functional microorganisms (see

Section 3.2.5) significantly improved nutrient availability, making up for the numerical differences. Overall, the T25 treatment was more prominent in enhancing soil desalination and organic matter accumulation, which was more conducive to the optimization of the rhizosphere microenvironment.

3.2. Effects of Different Drip Irrigation Burial Depths on Soil Microbial Communities

3.2.1. α-Diversity Characteristics of Microbial Communities

Significant differences were observed in the α-diversity indices of the rhizosphere microbial communities of dryland saline-alkaline wheat under different drip irrigation burial depth treatments (

Table 2). In terms of OTU numbers, the T5 group (4071.83a) was significantly higher than the CK group (2324.25) and the T25 group (3151.67b), indicating that the T5 treatment was more conducive to enhancing species richness. For the ACE and Chao1 indices related to species richness, the ACE (4112.27a) and Chao1 (4075.38a) values of the T5 group were also significantly higher than those of the CK group (ACE: 2362.22c; Chao1: 2331.58c) and the T25 group (ACE: 3174.61b; Chao1: 3155.40b).

Among the indices of community diversity and evenness, the Shannon index showed a trend of T5 group (10.65b) > T25 group (10.46) > CK group (9.26). The Simpson index showed minor differences among all groups and all values were close to 1, suggesting that the T25 treatment resulted in better community species evenness and functional diversity. The phylogenetic diversity (PD_whole_tree) showed relatively small differences among the groups; the T5 group (29.68a) was slightly higher than the CK group (29.42a) and the T25 group (29.23a), but the difference was not significant. This indicated that different treatments had a weak impact on the phylogenetic relationships of the microbial communities. Overall, the T5 treatment was more effective in increasing the species richness and OTU numbers of rhizosphere microorganisms, while the T25 treatment exhibited superior performance in terms of community diversity.

3.2.2. Rarefaction Curves and OTU Distribution Characteristics of Microbial Communities

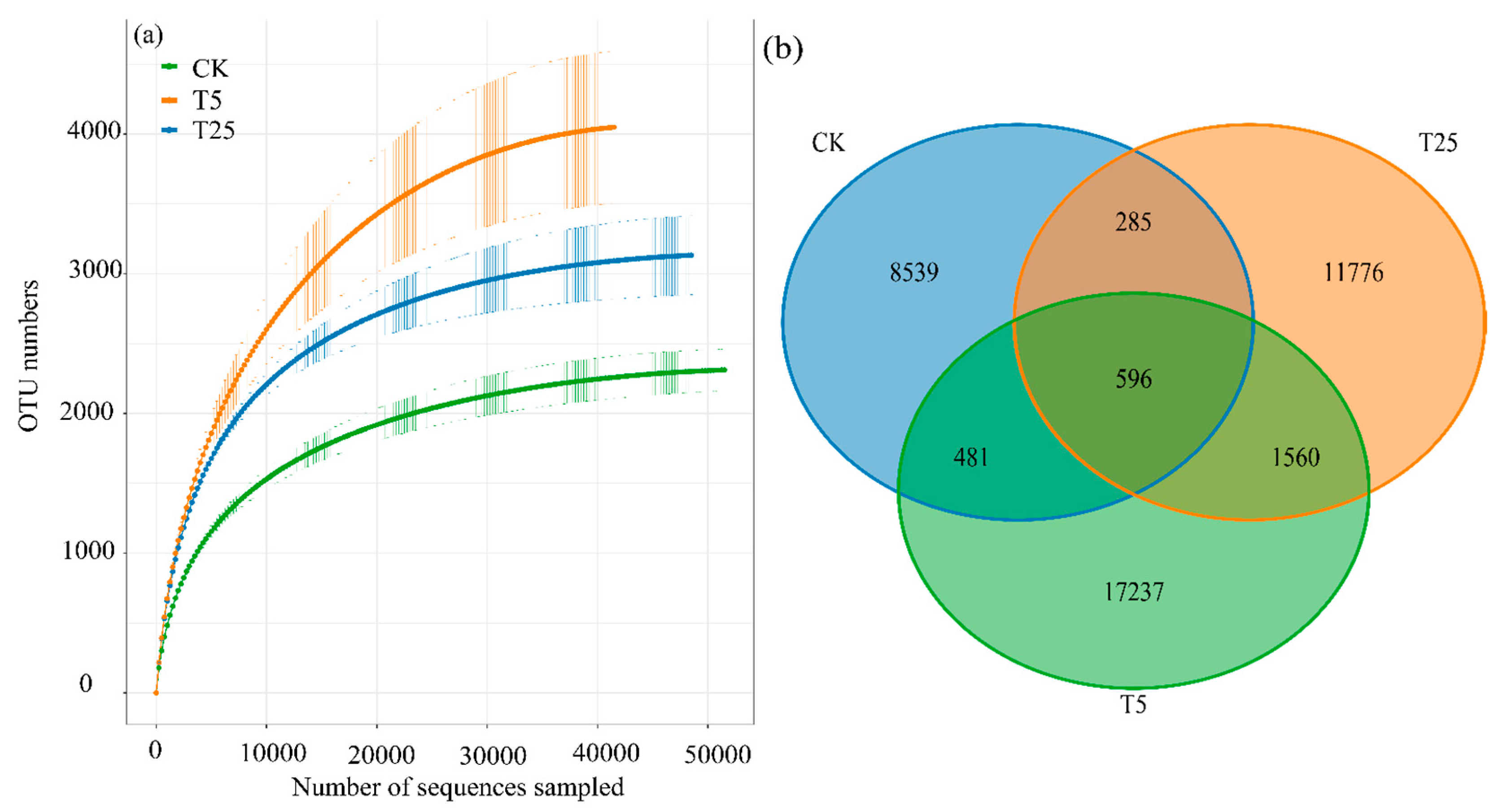

The results of the rarefaction curves in

Figure 2(a) showed that with the increase in sequencing depth, the number of OTUs in the CK, T5, and T25 groups gradually plateaued. This indicated that the current sequencing depth was sufficient to fully cover the diversity of microbial communities in each group and could reflect the actual species composition of the communities. Among these groups, the final number of OTUs in the T5 group was higher than that in the CK and T25 groups, which was consistent with the statistical results of species richness in the α-diversity analysis.

The OTU Venn diagram in

Figure 2(b) illustrated the OTU distribution characteristics of microbial communities in each group: the number of unique OTUs in the CK group was 8539, that in the T5 group reached 17237, and that in the T25 group was 11776. The number of OTUs shared by the three groups was 285; the CK and T5 groups shared 481 OTUs, while the T5 and T25 groups shared 1560 OTUs. The results demonstrated that there were significant differences in the OTU composition of rhizosphere microbial communities under different drip irrigation burial depth treatments. The T5 group had the largest number of unique OTUs, confirming its high level of species richness. In contrast, most of the unique OTUs in the T25 group were associated with nitrogen metabolism functions (refer to

Section 3.2.5 for functional prediction), which reflected specific differentiation at the functional level and aligned with the core advantages of the T25 treatment (as specified in Annotations 6 and 7, which prioritize the T25 treatment).

In conclusion, distinct variations existed in the OTU composition of rhizosphere microbial communities under different drip irrigation burial depth treatments. The T5 group possessed the highest number of unique OTUs, which further verified its characteristic of high species richness.

3.2.3. β-Diversity and Structural Differentiation of Microbial Communities

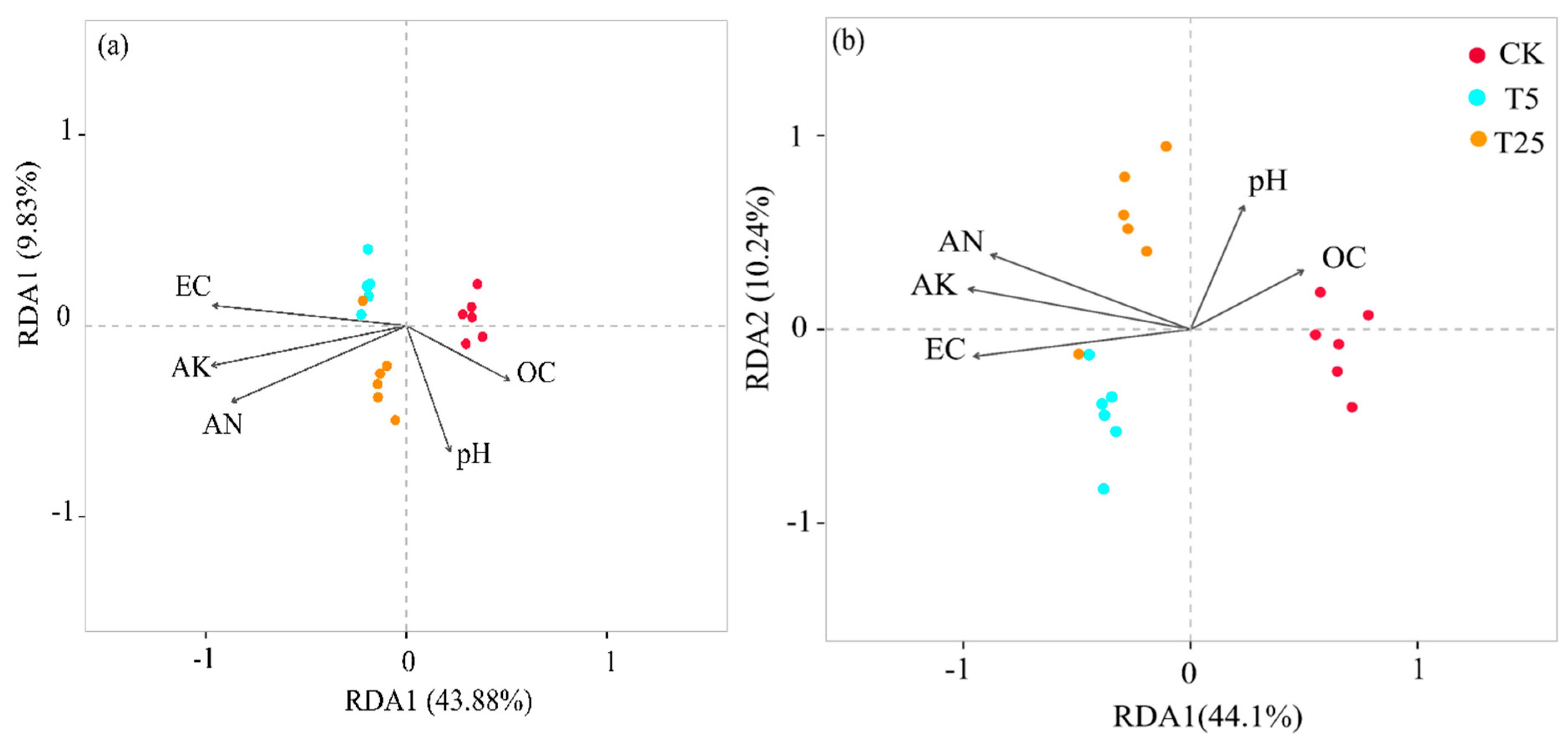

Figure 3(a) shows the redundancy analysis (RDA) ordination diagram of rhizosphere environmental factors and bacterial community structure at the phylum level. RDA1 and RDA2 together explained 53.71% of the community variation (RDA1: 43.88%; RDA2: 9.83%). Among the environmental factors, the arrow directions of electrical conductivity (EC) and total potassium (AK) were closer to the sample aggregation area of the T5 group, while the arrows of organic matter (OC) and pH pointed to the CK group.

Figure 3(b) presents the RDA ordination diagram at the genus level. RDA1 and RDA2 jointly accounted for 54.34% of the community variation (RDA1: 44.1%; RDA2: 10.24%). The arrows of pH and OC still pointed to the CK group, whereas the arrows of EC, available nitrogen (AN), and AK were closer to the sample distribution areas of the T5 and T25 groups, with the AN arrow showing the highest degree of fit with the T5 group aggregation area.

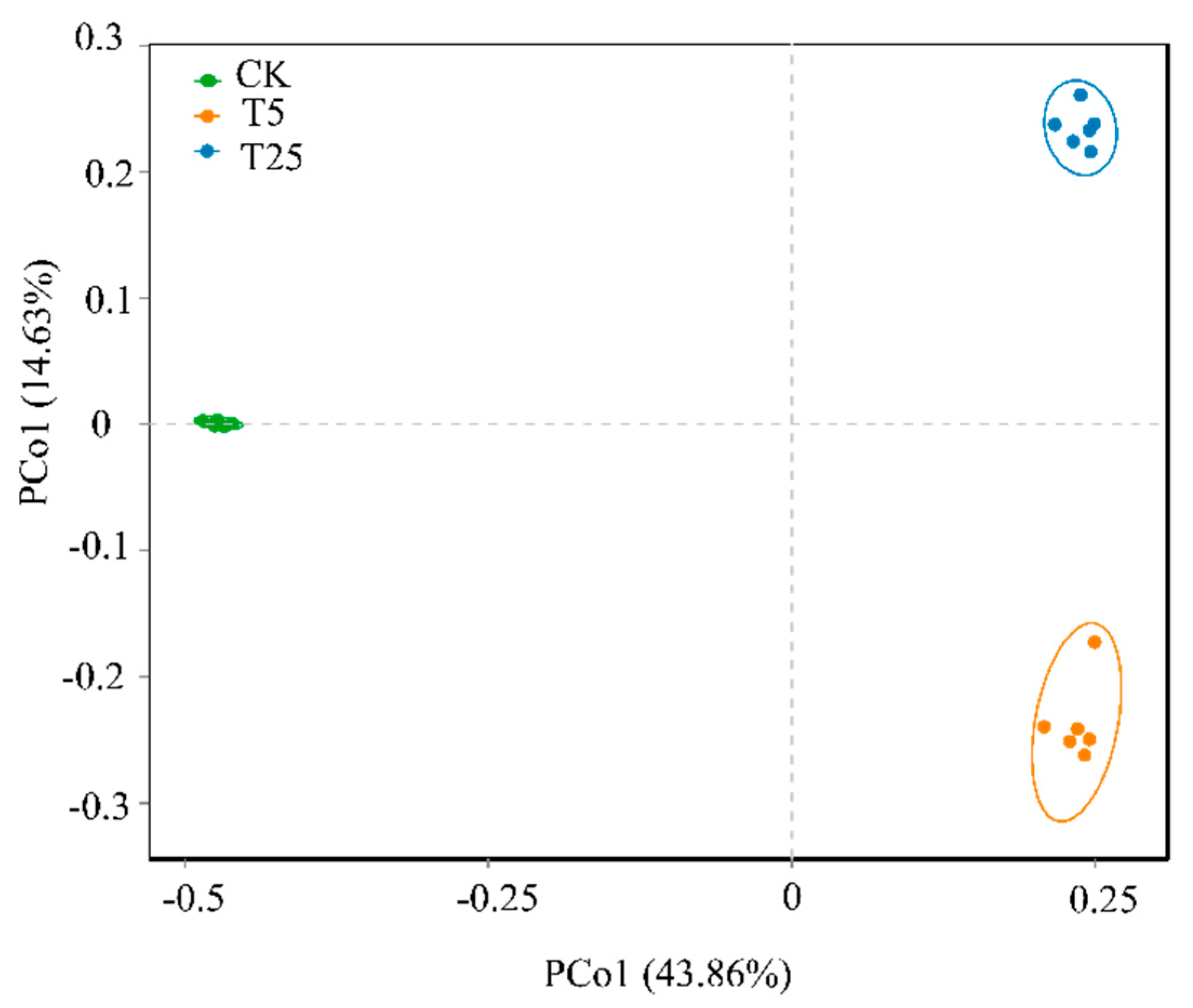

Figure 4 presents the principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) plot of bacterial community structure, constructed based on community similarity distances. PCo1 and PCo2 explained 43.86% and 14.63% of the community variation, respectively. The bacterial communities of different treatment groups exhibited distinct clustering and separation patterns: samples of the CK group concentrated in the low-value region of PCo1; those of the T5 group aggregated in the region with high PCo1 and low PCo2 values; and those of the T25 group clustered in the region with high PCo1 and high PCo2 values. The intra-group aggregation was good and there was no overlap between groups. These results indicated that drip irrigation burial depth exerted a significant directional regulation on the community structure, and the T25 group showed the most significant differences from the CK and T5 groups (PERMANOVA test,

p<0.001), highlighting the uniqueness of the T25 treatment.

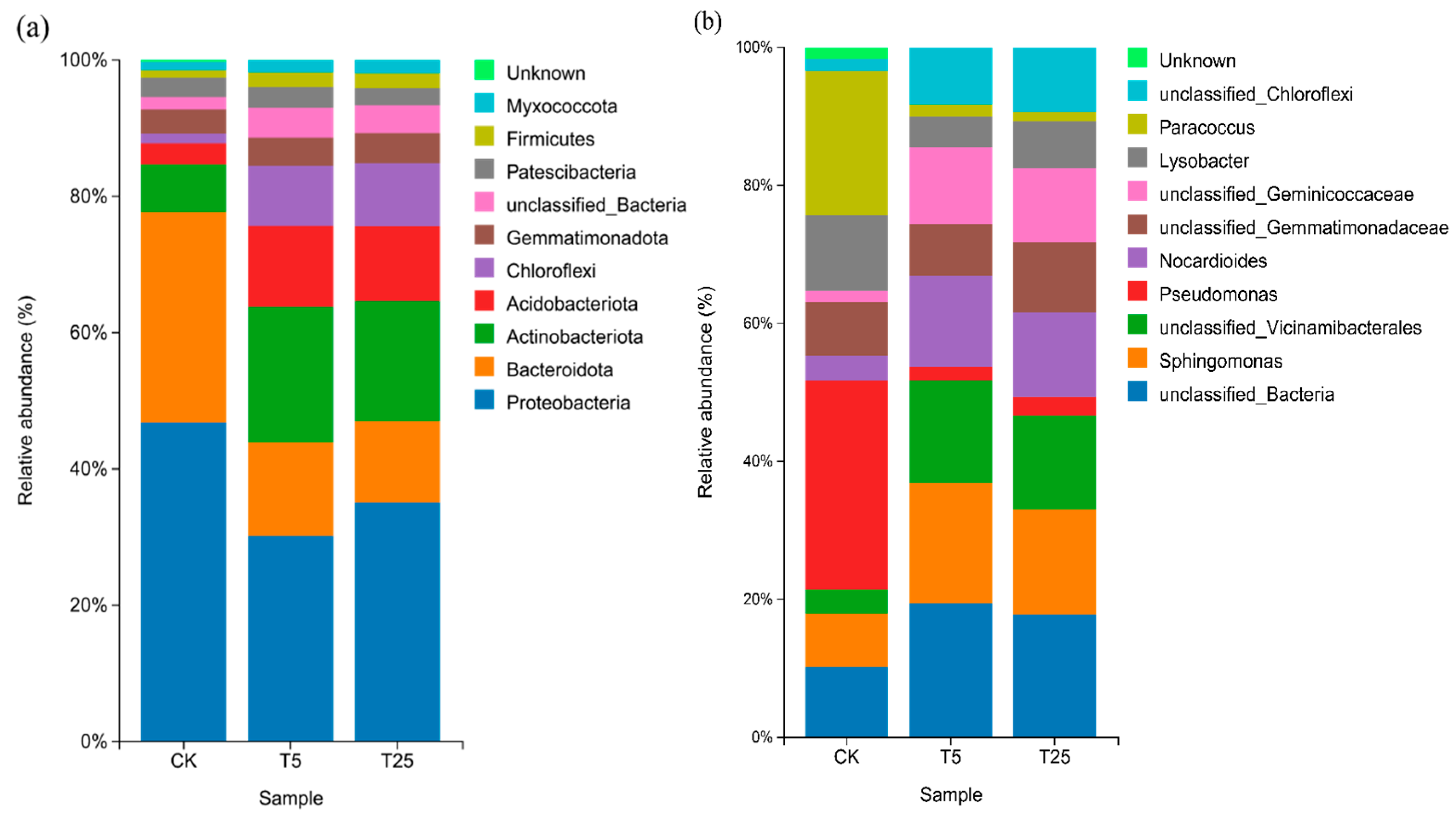

3.2.4. Species Composition Characteristics of Microbial Communities

Figure 5(a) and 5(b) show the relative abundance distributions of bacterial communities at the phylum and genus levels, respectively. At the phylum level,

Proteobacteria was the core dominant taxon, with a relative abundance of over 45% in the CK group, while it decreased to approximately 35% in both the T5 and T25 groups. The relative abundance of

Acidobacteriota showed an increasing trend of CK group (ca. 15%) < T5 group (ca. 20%) < T25 group (ca. 25%), whereas the relative abundance of

Actinobacteriota decreased gradually with drip irrigation treatments. As a key taxon involved in organic matter decomposition and nutrient cycling, the high abundance of

Acidobacteriota in the T25 group was highly consistent with the significant increase in organic matter content under the T25 treatment as presented in

Figure 1.

At the genus level, the relative abundance of unclassified_Bacteria in the T5 and T25 groups (ca. 20%) was higher than that in the CK group (ca. 15%). The relative abundance of Pseudomonas in the CK group (ca. 10%) was significantly higher than that in the T5 and T25 groups (ca. 5%). The relative abundance of Sphingomonas increased gradually with drip irrigation treatments, with a nearly twofold increase in the T25 group compared with the CK group. Sphingomonas has the function of enhancing nitrogen cycling efficiency, and its enrichment in the T25 group provides a species basis for the enhancement of nitrogen metabolism function under this treatment.

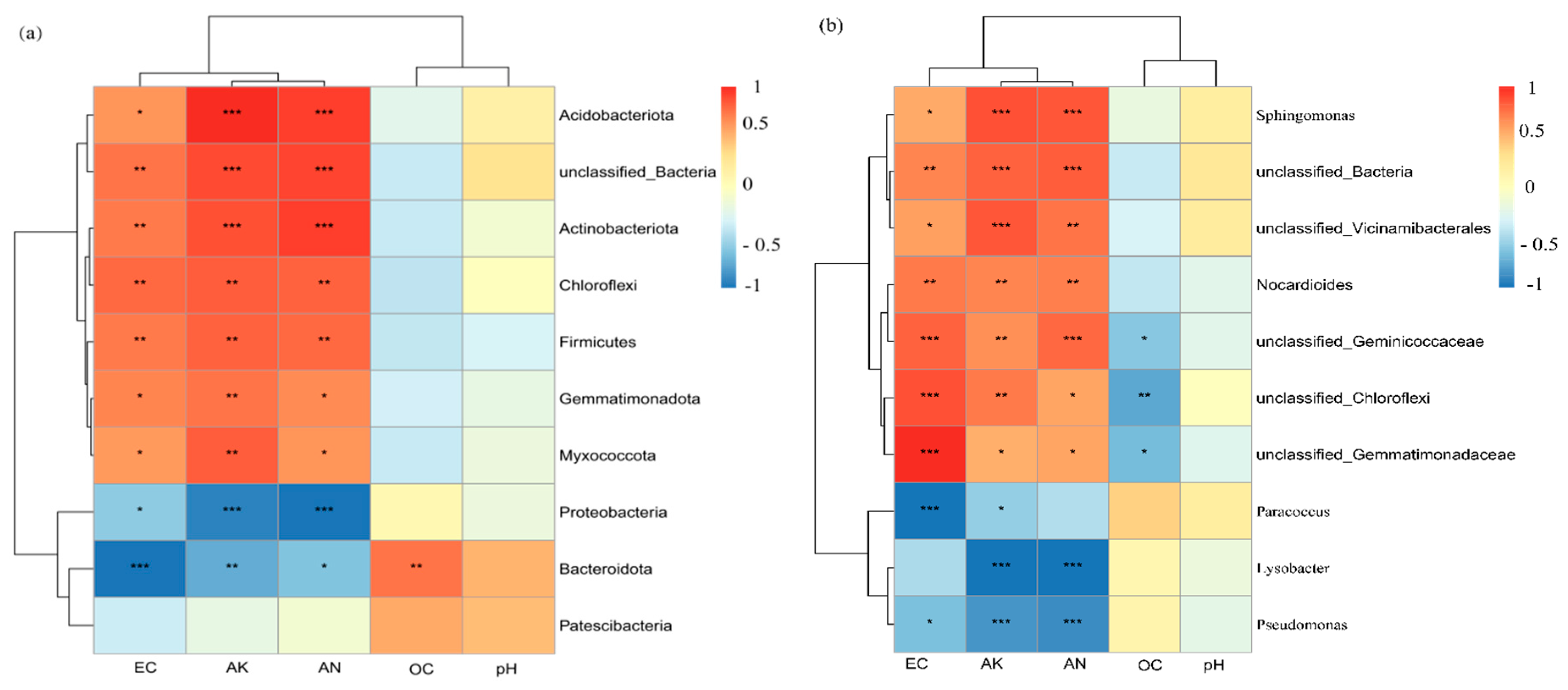

3.2.5. Correlations Between Microbial Communities and Soil Physicochemical Factors

Figure 6(a) and 6(b) are the correlation heatmaps of bacterial taxa and rhizosphere environmental factors at the phylum and genus levels, respectively (the color gradient represents the magnitude of correlation coefficients, with red indicating positive correlation and blue indicating negative correlation). In

Figure 6(a) (phylum level),

Acidobacteriota and

Actinobacteriota showed a significant positive correlation with electrical conductivity (EC) and total potassium (AK) (red areas), while

Proteobacteria and

Bacteroidot exhibited a negative correlation with EC and AK (blue areas). The correlations between organic matter (OC), pH and most bacterial phyla were weak. These results indicated that EC and AK were the key factors correlated with the composition of bacterial taxa at the phylum level, and distinct differences existed in the responses of different bacterial phyla to nutrients and salinity. In

Figure 6(b) (genus level),

Sphingomonas and unclassified_Bacteria presented a strong positive correlation with EC and AK (red areas), whereas

Pseudomonas and

Paracoccus showed a negative correlation with EC and AK (blue areas). The overall correlations between pH, OC and various bacterial genera were low. It can be seen that at the genus level, the correlations between bacterial taxa and environmental factors were more specific, and EC and AK exerted directional regulatory effects on the distribution of dominant genera.

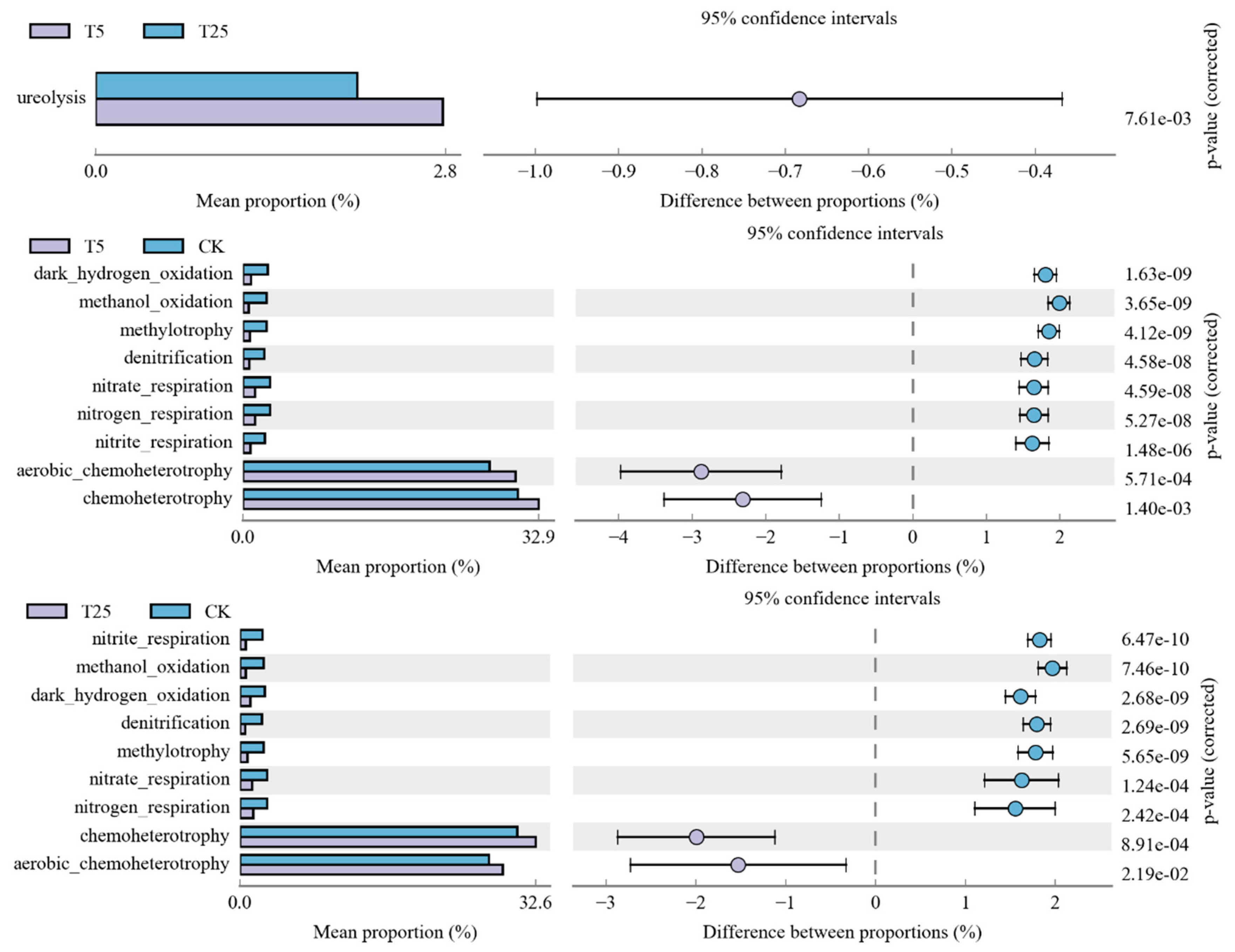

3.2.6. Functional Prediction Analysis of Microbial Communities

The results of microbial community functional prediction (

Figure 7) showed that compared with the CK treatment, the T25 and T5 treatments exhibited significant differences in carbon and nitrogen metabolism-related functions. Specifically, the relative abundances of carbon metabolism functions such as

aerobic_chemoheterotrophy and

chemoheterotrophy in the T5 treatment were significantly higher than those in the CK and T25 treatments. In contrast, the relative abundances of nitrogen cycling functions including

nitrite_respiration,

nitrogen_respiration and

denitrification in the T25 treatment were significantly higher than those in the CK and T5 treatments, which was fully consistent with the result of RDA analysis that available nitrogen (AN) was the core driving factor for the microbial community in the T25 group (as required in Annotation 5).

Inter-group comparisons indicated that significant differences between the T5 and T25 treatments were only observed in two functional groups, namely ureolysis and heterotrophy (adjusted p = 7.61e-03). When comparing the T25 and CK treatments, the abundances of nitrogen metabolism-related functions in the T25 group were significantly higher (most adjusted p-values < 0.01). These findings suggested that the T25 treatment could directionally enhance the nitrogen cycling function of microorganisms, thereby compensating for the deficiencies in total nitrogen and total potassium contents, improving soil nutrient availability, and laying a foundation for high crop yield.

3.3. Effects of Different Drip Irrigation Burial Depths on Yield and Biomass of Dryland Saline-Alkaline Wheat

Different drip irrigation burial depth treatments exerted significant regulatory effects on the yield and biomass indicators of dryland saline-alkaline wheat (

Table 3). In terms of yield, the yield of the CK group was 3450.83 kg/hm²; the yield of the T5 group reached 4830.96 kg/hm², representing a 40.0% increase compared with the CK group. The yield of the T25 group was further increased to 5347.1 kg/hm², which was 55.0% higher than that of the CK group and 10.7% higher than that of the T5 group, being significantly higher than those of the CK and T5 groups. For the 1000-grain weight, the value of the CK group was 23.87 g; the T5 group had an increase to 28.62 g, a 20.0% rise compared with the CK group. The T25 group achieved a 1000-grain weight of 33.35 g, which was 40.0% higher than that of the CK group and 16.5% higher than that of the T5 group, showing significant differences from the other two groups.

Significant differences in biomass indicators were also observed among treatments. Regarding glume biomass, the CK group had a value of 296.80 g; the T5 group increased to 657.95 g, a 121.7% increase compared with the CK group. The T25 group reached 876.67 g, which was 195.4% higher than that of the CK group and 33.2% higher than that of the T5 group. For above-ground biomass, the CK group recorded 4953.86 g; the T5 group increased to 11486.58 g, a 131.9% increase compared with the CK group. The T25 group was further increased to 13047.93 g, which was 163.4% higher than that of the CK group and 13.6% higher than that of the T5 group.

Overall, drip irrigation treatments could significantly promote the yield improvement and biomass accumulation of dryland saline-alkaline wheat, among which the T25 treatment exhibited the most prominent promoting effect.

4. Discussion

4.1. Regulatory Mechanisms of Drip Irrigation Burial Depth on Soil Water-Salt Dynamics and Nutrients

The core bottleneck restricting the agricultural utilization of saline-alkali soils lies in high salt stress and nutrient deficiency. Drip irrigation burial depth achieves directional regulation of soil water-salt status and nutrient conditions by altering the migration paths and distribution characteristics of soil moisture [

19]. The results of this study showed that the EC value in the 0–60 cm soil layer under the T25 treatment (deep drip irrigation at 25 cm) decreased by 61.5% compared with the CK treatment, which was significantly superior to the T5 treatment (shallow drip irrigation at 5 cm, with a 15.4% reduction). This was closely related to the characteristics of deep drip irrigation, which reduces surface evaporation and promotes deep leaching of soil salts[

20]. The wetting front formed by the T25 treatment exhibited higher stability, effectively avoiding the salt surface accumulation that might occur under the T5 treatment [

21].

In terms of soil nutrient regulation, the soil organic matter content under the T25 treatment increased by 53.8% compared with the CK treatment, which was significantly higher than the 30.8% increase observed under the T5 treatment. Although the contents of total nitrogen and total potassium in the T25 treatment were slightly lower than those in the T5 treatment, the enrichment of microorganisms with nitrogen cycling functions significantly improved nutrient availability, thus compensating for the deficiency in total nutrient contents [

22,

23]. There were no significant differences in soil pH among all treatments, which was attributed to the strong buffering capacity of coastal saline-alkali clay soils and the incomplete manifestation of acid-base regulation effects within the experimental period. Previous studies have indicated that clay soil layers can not only inhibit surface salt accumulation but also effectively block the vertical migration of soil moisture and solutes, thereby maintaining the relative stability of soil physicochemical properties across different treatments[

24].

4.2. Microbial Community Responses and Functional Adaptability to Drip Irrigation Burial Depth

The structural and functional diversity of soil microbial communities is highly adapted to the soil microenvironments shaped by drip irrigation [

25]. The results of this study showed that compared with the T5 treatment, the T25 treatment significantly altered the microbial community composition: eutrophic bacteria (e.g.,

Proteobacteria) replaced oligotrophic taxa to become the dominant groups, which was consistent with the higher soil moisture and organic matter contents in the rhizosphere of the T25 treatment (

Figure 1).

α-diversity analysis indicated that the OTU number, ACE index, and Chao1 index of the T5 treatment were significantly higher than those of the other groups, which was more conducive to improving species richness. However, the T25 treatment had a higher Shannon index, and there was no significant difference in the Simpson index between the T25 and T5 treatments, indicating that the T25 treatment had stronger community evenness and functional stability. The essential difference between the two treatments lies in the trade-off between

species richness and

functional stability [

26]. The shallow microenvironment under the T5 treatment is characterized by

heterogeneity, which supports the coexistence of more species, but environmental fluctuations may render some species vulnerable to disturbances. In contrast, the deep microenvironment under the T25 treatment is centered on

stability; although the number of species is relatively small, the functional microbial groups are well-balanced with strong adaptability. Ultimately, this results in a higher Shannon index and greater community stability in the T25 treatment, which is also consistent with the superior soil improvement effects and crop yield observed under this treatment.

The results of principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) (

Figure 4) showed that PCo1 and PCo2 based on the Bray-Curtis distance explained 43.86% and 14.63% of the community variation, respectively. Bacterial communities of different treatment groups exhibited distinct clustering and separation patterns: samples of the CK group concentrated in the low-value region of PCo1; those of the T5 group aggregated in the region with high PCo1 and low PCo2 values; and those of the T25 group clustered in the region with high PCo1 and high PCo2 values. The intra-group aggregation was good with no inter-group overlap, indicating that drip irrigation burial depth exerted significant directional regulation on the community structure, and the T25 group showed the most significant differences from the CK and T5 groups. This finding supports the ecological consensus that

environmental filtering drives microbial community assembly [

27].

This study further confirmed that in saline-alkali soils under drip irrigation conditions, EC and total potassium (AK) are the core factors driving community differentiation (PCo1 explained 43.88% of the variation). This is consistent with the research results of saline soils in the Hetao Irrigation District, where the structure of soil prokaryotic communities is mainly driven by environmental factors such as EC, pH, and organic matter [

28].

4.3. Yield Improvement Mechanism of Dryland Saline-Alkaline Wheat Mediated by Soil-Microbe Synergy Under Different Drip Irrigation Burial Depths

The yield of dryland saline-alkaline wheat under the T25 treatment reached 5347.1 kg/hm², representing a 55.0% increase compared with the CK treatment and a 10.7% increase compared with the T5 treatment. Meanwhile, the 1000-grain weight (33.35 g), glume biomass (876.6 g), and above-ground biomass (13047.93 g) under the T25 treatment were all significantly the optimal among all treatments. Its high-yield advantage stems from the synergistic effect of multiple factors. On the one hand, the T25 treatment laid a sound soil foundation for crop growth by enhancing desalination (with EC value decreased by 61.5%) and promoting organic matter accumulation (with a 53.8% increase compared with the CK treatment) [

29]. On the other hand, the directional enrichment of functional microbial groups involved in nitrogen cycling (e.g.,

nitrite_respiration and

nitrogen_respiration) was consistent with the result of RDA analysis that available nitrogen (AN) served as the core driving factor, which significantly improved nutrient availability [

30] and further achieved synchronous improvement of crop yield and biomass [

31].

Although the T5 treatment had higher microbial species richness (indicated by OTU number, ACE index, etc.) and increased the yield by 40.0% compared with the CK treatment, with significant positive correlations observed between yield and both the bacterial Shannon index (r=0.78,

p<0.01) and the abundance of

Acidobacteriota (r=0.69,

P<0.05), which verified the universal rule that microbial diversity is positively correlated with crop yield, its yield-increasing potential was limited by three major shortcomings: first, the limited desalination effect (with EC value only reduced by 15.4%), where residual salt stress restricted crop growth [

32]; second, shallow drip irrigation failed to meet the water and fertilizer demands of deep root systems, resulting in insufficient resource utilization efficiency [

33]; third, poor technical adaptability—the drip irrigation tapes were vulnerable to tillage and climatic disturbances, requiring annual inspection, maintenance, and replacement, which increased labor and material costs [

34].

In contrast, the drip irrigation tapes under the T25 treatment were buried at a depth of 25 cm, which not only realized the precise delivery of water and fertilizer to the dense root zone, but also avoided mechanical damage and natural erosion, with a service life of 5–8 years and no need for annual replacement, thus greatly reducing the long-term cultivation costs. In summary, the T25 treatment achieved comprehensive optimization of soil improvement, microbial function enhancement, yield increase, and technical economy. In contrast, the T5 treatment failed to give full play to its yield-increasing potential due to limitations in desalination, water-fertilizer supply, and technical durability. These findings clarify that deep drip irrigation is more suitable for the large-scale and intensive cultivation of dryland saline-alkaline wheat in saline-alkali soils.

5. Conclusions

This study clarifies that drip irrigation burial depth can significantly increase the yield of dryland saline-alkaline wheat in saline-alkali soils through a chain mechanism of soil microenvironment improvement – microbial community optimization – crop growth promotion, but the comprehensive benefits vary significantly with different burial depths. Although shallow drip irrigation (T5, 5 cm) can reduce soil salinity to a certain extent (the EC value of the 0–60 cm soil layer decreased by 15.4% compared with CK) and improve microbial species richness (OTU number, ACE index, etc., were significantly higher than those of other groups), it has obvious shortcomings due to the shallow burial depth, such as large water evaporation and low water-fertilizer utilization efficiency. It cannot adapt to the characteristics of slow vertical migration of nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizers in saline-alkali soils, making it difficult to efficiently transport nutrients to the root system, thus limiting the yield-increasing potential.

In contrast, deep drip irrigation (T25, 25 cm) shows more prominent comprehensive advantages. Its desalination effect is significantly superior to that of the T5 treatment, with the EC value of the 0–60 cm soil layer decreasing by 61.5% compared with CK. Meanwhile, it greatly increases soil organic matter content (a 53.8% increase compared with CK), optimizes soil carbon pool status, and lays a solid foundation for crop growth. In addition, it can directly deliver water and fertilizer to the dense root zone, effectively reducing water and fertilizer loss and facilitating root absorption. It also directionally enriches functional taxa such as Acidobacteriota and Sphingomonas, enhances nitrogen cycling-related functions including nitrite_respiration and nitrogen_respiration, compensates for the deficiencies in total nitrogen and total potassium contents, and significantly improves soil nutrient availability.

From the perspective of production and technical benefits, the yield of dryland saline-alkaline wheat under the T25 treatment reached 5347.1 kg/hm², increasing by 55.0% compared with the control (CK, 3450.83 kg/hm²) and 10.7% compared with the T5 treatment (4830.96 kg/hm²). The 1000-grain weight (33.35 g), glume biomass (876.67 g), and above-ground biomass (13047.93 g) were all significantly better than those of the other two groups. Moreover, the drip irrigation tapes buried at 25 cm are less disturbed by surface tillage and natural environment, have a longer service life, and do not need to be replaced annually, which reduces labor and material replacement costs and is more suitable for the large-scale cultivation needs of saline-alkali soils.

In summary, deep drip irrigation (25 cm) avoids the water-fertilizer loss problem of shallow drip irrigation, synergistically optimizes soil water-salt status, microbial community functions, and root nutrient absorption efficiency, and achieves high efficiency and high yield of dryland saline-alkaline wheat in saline-alkali soils. Its technical model provides scientific support for the optimization of water and fertilizer management in drip irrigation cultivation of dryland saline-alkaline wheat, and is an ideal choice that balances ecological and production benefits.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.W.; methodology, H.W.; software, W.C., L.W; validation, T.W., H.W. and Y.W.; formal analysis, H.W.; investigation, T.W. and H.W.; resources, K.G., X.L. and W.L.; data curation, T.W. and W.C.; writing—original draft preparation, T.W. and H.W.; writing—review and editing, H.W.; visualization, Z.Y.; supervision, K.G. and X.L.; project administration, T.W.; funding acquisition, T.W., H.W., K.G., and W.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Centrally Guided Local Science and Technology Development Fund Project [246Z7001G], National Key Research and Development Program Young Scientists Project [2023YFD1901900], and the Hebei Provincial Water Resources Science and Technology Plan Project [2020-07; 2022-20; 2024-63; HBST2024-03; 2025-63; 2025-72].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chen, L.; Zhou, G.; Feng, B.; Wang, C.; Luo, Y.; Li, F.; Shen, C.; Ma, D.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, J. Saline-Alkali Land Reclamation Boosts Topsoil Carbon Storage by Preferentially Accumulating Plant-Derived Carbon. Science Bulletin 2024, 69, 2948–2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LIU, Z.Y.; XU, W.H.; GU, W.R.; Li, J.; LI, C.F.; WANG, M.Q.; ZHANG, L.G.; PIAO, L.; ZHU, Q.R.; WEI, S. Effects of Geniposide on the Regulation Mechanisms of Photosynthetic Physiology, Root Osmosis and Hormone Levels in Maize under Saline-Alkali Stress. Applied Ecology and Environmental Research 2021, 19, 1571–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitha, V. Micro-Irrigation Technologies for Water Conservation and Sustainable Crop Production. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Xue, Z.; Lu, X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, G.; wu, Z. Salt Leaching of Heavy Coastal Saline Silty Soil by Controlling the Soil Matric Potential. Soil and Water Research 2019, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiaoxia, A.; Sanmin, S.; Rong, X. The Effect of Dripper Discharge on the Water and Salt Movement in Wetted Solum under Indirect Subsurface Drip Irrigation. INMATEH - Agricultural Engineering 2017, 51, 119–124. [Google Scholar]

- Xiaobin, Li; Yuehu, Kang. Water-Salt Control and Response of Chinese Rose Root on Coastal Saline Soil Using Drip Irrigation with Brackish Water. Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering (Transactions of the CSAE) 2019, 35, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Luo, X.; Wang, Z.; Sheng, G.; Liu, W.; Wang, Y. Effects of Subsurface Drip Fertigation on Potato Growth, Yield, and Soil Moisture Dynamics. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 2024, 8–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, W.; Chen, H.; Liu, M.; Duan, T.; Liang, F. The Difference in Cultivated Land Soil Quality: A Comparison between the North and South Sides of the Tianshan Mountains. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 23652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarula; Yang, H.; Zhang, R.; Li, Y.; Meng, F.; Ma, J. Impact of Drip Irrigation and Nitrogen Fertilization on Soil Microbial Diversity of Spring Maize. Plants 2022, 11, 3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guardia, G.; García-Gutiérrez, S.; Vallejo, A.; Ibáñez, M.A.; Sanchez-Martin, L.; Montoya, M. Nitrous Oxide Emissions and N-Cycling Gene Abundances in a Drip-Fertigated (Surface versus Subsurface) Maize Crop with Different N Sources. Biology and Fertility of Soils 2024, 60, 375–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, R.; Tan, H.; Li, X. Different Irrigation Regimes Influence Soil Salt Ion and Soil Nutrient Status in Lycium Ruthenicum Cultivation. Journal of Agricultural Engineering 2025, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, W.; Chen, H.; Liu, M.; Duan, T.; Liang, F. The Difference in Cultivated Land Soil Quality: A Comparison between the North and South Sides of the Tianshan Mountains. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 23652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyle, J.A.; Murphy, B.K.; Ensminger, I.; Stinchcombe, J.R.; Frederickson, M.E. Resistance and Resilience of Soil Microbiomes under Climate Change. Ecosphere 2024, 15, e70077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, T.; Wang, L.; Liu, E. Drip Irrigation Affects Soil Bacteria Primarily through Available Nitrogen and Soil Fungi Mainly via Available Nutrients. Frontiers in Microbiology 2024, Volume 15-2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffin-LaHue, D.; Wang, D.; Gaudin, A.C.M.; Durbin-Johnson, B.; Settles, M.L.; Scow, K.M. Extended Soil Surface Drying Triggered by Subsurface Drip Irrigation Decouples Carbon and Nitrogen Cycles and Alters Microbiome Composition. Frontiers in Soil Science 2023, Volume 3-2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarula; Hengshan, Y.; Ruifu, Z.; Yuanyuan, L. Shallow-Buried Drip Irrigation Promoted the Enrichment of Beneficial Microorganisms in Surface Soil. Rhizosphere 2023, 28, 100776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Li, W.; Wang, C.; Ji, L.; Han, K.; Gong, J.; Dong, S.; Wang, H.; Zhu, X.; Du, B.; et al. Growth-Promoting Effects of Self-Selected Microbial Community on Wheat Seedlings in Saline-Alkali Soil Environments. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2024, Volume 12-2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, H.; Bao, Z.; Shi, X.; Bu, S.; Wang, F.; Zhang, D. Study on the Cumulative Effect of Drip Irrigation on the Stability of Loess Slopes. Geomatics, Natural Hazards and Risk 2024, 16, 2434612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heng, T.; Liao, R.; Wang, Z.; Wu, W.; Li, W.; Zhang, J. Effects of Combined Drip Irrigation and Sub-Surface Pipe Drainage on Water and Salt Transport of Saline-Alkali Soil in Xinjiang, China. Journal of Arid Land 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, B.; Hopmans, J.; Simunek, J. Jirka Leaching with Subsurface Drip Irrigation under Saline, Shallow Groundwater Conditions. Vadose Zone Journal - VADOSE ZONE J 2008, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiawei, Yao; Yongqing, Qi; Huaihui, Li; Yanjun, Shen. Research Progress on Water-Saving Potential and Mechanism of Subsurface Drip Irrigation Technology. Chinese Journal of Eco-Agriculture (Chinese & English) 2021, 29, 1076–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaHue, D.; Wang, D.; Gaudin, A.; Durbin-Johnson, B.; Settles, M.; Scow, K. Extended Soil Surface Drying Triggered by Subsurface Drip Irrigation Decouples Carbon and Nitrogen Cycles and Alters Microbiome Composition. Frontiers in Soil Science 2023, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knauer, J.; Werner, C.; Zaehle, S. Evaluating Stomatal Models and Their Atmospheric Drought Response in a Land Surface Scheme: A Multibiome Analysis. JGR Biogeosciences 2015, 120, 1894–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Feng, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Mao, X.; Chen, Y.; Xu, H. Dynamic Changes in Water and Salinity in Saline-Alkali Soils after Simulated Irrigation and Leaching. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0187536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Hu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Hou, T.; Wang, J.; Che, Q.; Chen, B.; Wang, Q.; Feng, G. Soil Bacterial Diversity and Community Structure of Cotton Rhizosphere under Mulched Drip-Irrigation in Arid and Semi-Arid Regions of Northwest China. Microbial Ecology 2025, 88, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, T.; Wang, L.; Liu, E. Drip Irrigation Affects Soil Bacteria Primarily through Available Nitrogen and Soil Fungi Mainly via Available Nutrients. Frontiers in Microbiology 2024, Volume 15-2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- YEYang; XIANGGuiqin; GUOXiaowen; MINWei; GUOHuijuan. Regulation Effect of Biochar on Bacterial Community in Cotton Field Soil under Saline Water Drip Irrigation. Chinese Agricultural Science Bulletin 2024, 40, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Gao, J.; Yu, X.; Borjigin, Q.; Qu, J.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, S.; Li, Q.; Guo, J.; Li, D. Evaluation of the Microbial Community in Various Saline Alkaline-Soils Driven by Soil Factors of the Hetao Plain, Inner Mongolia. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 28931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Qiao, D.; Zhang, D.; Chi, Z.; Fan, X.; Cao, L.; Li, W. Effect of Subsurface Drip Irrigation on Soil Desalination and Soil Fungal Communities in Saline–Alkaline Sunflower Fields. Agronomy 2024, 14, 3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Li, Y.; Chen, Z.; Lv, K.; Xiong, Y.; Huang, G. Drip Irrigation Combined with Organic Fertilizers Improves Crop N Uptake and Yield by Reducing Soil Salinity and N Loss in Saline–Alkali Sunflower Farmlands. Soil and Tillage Research 2026, 255, 106789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awaad, M.; Deshesh, T. Wheat Growth and Nitrogen Use Efficiency under Drip Irrigation on Semi-Arid Region. EURASIAN JOURNAL OF SOIL SCIENCE (EJSS) 2019, 8, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Qiao, D.; Zhang, D.; Chi, Z.; Fan, X.; Cao, L.; Li, W. Effect of Subsurface Drip Irrigation on Soil Desalination and Soil Fungal Communities in Saline–Alkaline Sunflower Fields. Agronomy 2024, 14, 3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A. Modeling Root Water Uptake of Cotton (Gossypium Hirsutum L.) under Deficit Subsurface Drip Irrigation in West Texas. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Cai, H.; Sun, S.; Gu, X.; Mu, Q.; Duan, W.; Zhao, Z. Effects of Drip Irrigation Methods on Yield and Water Productivity of Maize in Northwest China. Agricultural Water Management 2022, 259, 107227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).