1. Reader Contract: Assumptions, Scope, Falsifiability

We isolate what is structural (within stated assumptions) from what is model-dependent (matching and numerical outputs).

A1 (Neighborhood choice). The substrate admits a meaningful nearest-neighbor block in three spatial dimensions.

A2 (Audit criterion). “Matter” is defined operationally as an auditable image: certification requires a joint neighborhood constraint to be satisfied to tolerance .

A3 (Circuit locality). One QCA timestep admits a bounded-depth decomposition into layers of disjoint two-site unitaries (plus optional on-site unitaries).

A4 (Copy-time control parameter). A stiffness/gap-like parameter controls distinguishability growth in a gapped/stiff sector, enabling a conditional bound (constants depend on tolerance and model class).

A5 (UV/IR matching). Any Planck calibration and any RG/FRG flow mapping UV scales to IR masses is model-dependent and must be stated as an ansatz or computed explicitly.

Falsifiable content here. Under (A1–A3) the bound is structural. Under (A2–A4) the inequality is structural. Any specific IR mass value requires (A5).

2. Model Definition: QCA Dynamics and Audit Closure

2.1. Lattice, Local Degrees of Freedom, and Global Update

Let the lattice be

with nearest-neighbor adjacency. Each site

x carries a finite-dimensional Hilbert space

A single QCA timestep is a translation-invariant, causal (locality-preserving) unitary

U acting on

[

1,

2,

3]. We assume a depth-

D circuit representation

where each layer

is a product of commuting two-site unitaries on disjoint edges (a matching), optionally interleaved with on-site unitaries.

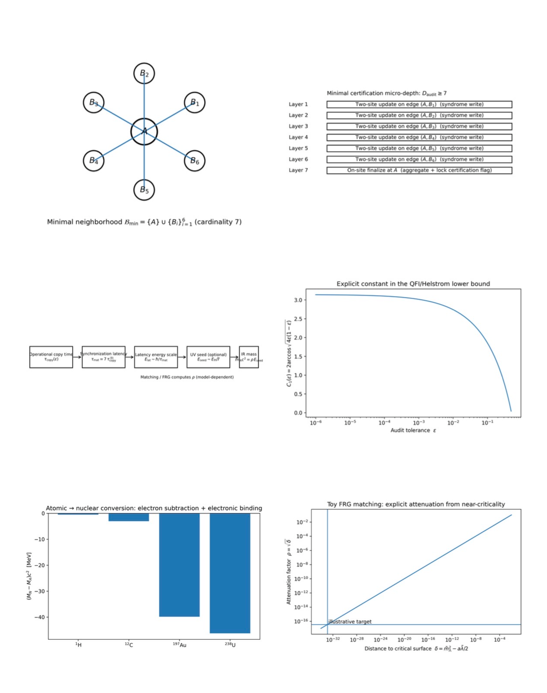

2.2. Minimal Neighborhood Block

Define the

neighborhood

where

A is central and

are its six axis neighbors.

2.3. Formal Audit Closure

Let be a projector acting on defining the set of configurations judged auditable. One concrete choice is “six link constraints” between A and each neighbor (e.g. agreement of syndrome bits or stabilizer eigenvalues).

3. Why the Minimal Certification Depth is Micro-Steps

This is the first reinforcement brick: the factor 7 is a depth lower bound from locality scheduling.

3.1. Scheduling Constraint: One Edge per Layer per Site

In a layer made of disjoint two-site unitaries, any site can participate in at most one two-site gate. The central site A has six incident edges that must be incorporated if audit closure depends on all six neighbor relations.

3.2. Proposition (Minimal Certification Depth)

Proposition. Assume (A1–A3) and that audit closure requires incorporating information from each link

into a joint certification (so that all six link constraints are checkable). Then

where

corresponds to an on-site “audit finalization” step (writing/locking a certification flag at

A).

Proof sketch. Each layer is a matching; site A can interact with at most one neighbor per layer. Covering the six incident edges requires at least six two-site layers. A final on-site layer aggregates/locks the audit result, hence . □

4. Operational Definition of Copy Time via Distinguishability (Helstrom)

This is the second reinforcement brick: is operational.

4.1. Distinguishability and Minimal Decision Error

Let

be a reference state and

the state after

t micro-layers. Define the trace distance

For binary hypothesis testing with equal priors, the Helstrom bound gives

[

6]. Therefore a tolerance

can be implemented as a distinguishability threshold:

4.2. Definition (copy time)

Definition. For specified

, define the copy time as

5. Quantum-Speed-Limit Style Lower Bound and the Scaling

This is the third reinforcement brick: admits a principled lower bound tied to information geometry.

5.1. Fidelity/Bures and Quantum Fisher Information

Let

be the fidelity. The Bures angle is

. Quantum speed-limit (QSL) inequalities relate the rate of state change to generators and information metrics [

7]. In unitary families, quantum Fisher information (QFI) controls distinguishability rates; in many settings one can write a speed-limit form (schematically)

and for approximately constant QFI this yields

.

5.2. Mini-Section: in This Model (Definition, Dimension, How to Compute)

We now make concrete for the toy-QCA setting.

Definition (effective local generator).

Associate each micro-layer with an effective local generator

K via a discrete-to-continuous parametrization:

Here

is dimensionless and

has dimensions of energy.

Definition (stiffness parameter ).

For a chosen reference state

(e.g. the pre-audit local vacuum/ready state), define

where

. With this choice,

has units of (because

has units of energy

2 and

converts it to

).

How to compute in the toy QCA.

Once the explicit gate set is chosen (

Appendix A), one can:

Concrete example (controlled-phase).

If the edge-interaction in layers 1–6 uses a two-qubit controlled-phase / Ising form

puis

, et pour la référence

, on obtient :

. D’où :

So is the natural “rate” set by the gate angle per micro-time.

5.3. Copy-Time Bound in Terms of

Assume (A4) that

controls distinguishability growth in the relevant sector so that QFI is bounded as

(constants depend on the audit protocol and model class). Combining (

10) with the certification threshold (

8) yields the conditional lower bound

6. Synchronization Latency as an Operational Timescale

Define the matter certification time

Combining (

16) with (

15) yields the reinforced (conditional) inequality

7. Locality Reinforcement: Lieb–Robinson and Why Synchronization is Meaningful

Locality-preserving dynamics supports an emergent causal cone; in lattice systems this is formalized by Lieb–Robinson bounds [

4,

5]. This supports treating audit closure as a finite-time synchronization over

: influence from outside

is suppressed at short times relative to the effective light-cone.

8. Reproducible Mapping: Latency → Energy → Mass

8.1. Latency Energy Scale

Use the heuristic

If (only if) one chooses

as a UV boundary condition, then

with Planck conventions from CODATA/NIST [

14,

15].

8.2. Explicit UV-to-IR Attenuation Factor

To connect

to an IR mass

, define

where

is computed by a specified matching/flow scheme (e.g. FRG) [

8,

9].

Context: Higgs-portal singlet scalar.

A real singlet scalar in the Higgs portal is a standard benchmark; the resonant region

is phenomenologically special [

10,

11,

12]. Any specific value (e.g.

) must be presented as a model-dependent output of an explicit

computation.

9. Reproducibility and Audit Trail (“Data vs Priors” Hard Separation)

Rule R1 (freeze priors). Fix before any comparison: neighborhood choice, audit threshold , data sources (PDG/NIST/AME), and calibration convention.

Maintain a minimal audit log:

AUDIT_RUN:

script_sha256: <hash>

inputs_sha256: <hash>

conventions: {Planck: "reduced/unreduced", eps: 1e-6, u_to_MeV: 931.49410242}

outputs:

table_atomic_to_nuclear_sha256: <hash>

10. Mass-Data Hygiene: PDG vs NIST vs AME

We separate:

Particle masses (PDG) [

13],

Atomic/isotopic masses (NIST) [

18,

19,

20,

21],

Nuclear masses derived from atomic masses (AME practice) [

16,

17].

10.1. Atomic-to-Nuclear Conversion

Given a neutral-atom mass

, the nuclear mass is [

17]

with electronic binding energy

. A widely used approximation is [

17]

11. Interpretive Summary (Reinforced)

Matter is a waiting time: a stable “image” is certified only after an audit closes over a minimal neighborhood.

Reinforcement comes from:

- 1.

Geometry + locality scheduling: implies

(

5).

- 2.

Operational measurability: via Helstrom distinguishability (

9).

- 3.

Lower-bound control: admits a QSL/QFI lower bound (

15), hence

obeys (

17).

- 4.

Auditability: priors/validation separation and hash-logged artifacts prevent post-hoc tuning.

12. Outlook: Superheavy Stability as Conjecture (Scoped)

Conjecture (coherence-volume bound). If audit latency enforces an upper bound on sustainable coherence volume, then beyond a critical complexity the certification time may exceed relevant decoherence times, yielding systematically shortened lifetimes for sufficiently heavy nuclei.

Appendix A. Explicit 7-Layer Toy Gate Set (One Certified Neighborhood)

This appendix gives a minimal, explicit gate schedule that realizes a audit closure in exactly 7 micro-layers.

Appendix A.1. Registers

For the central site A and each neighbor (with ), assume:

field qubits: at A, and at ;

audit bits at A: a 6-bit register (one bit per neighbor link) and a 1-bit certification flag .

Initialize and .

Appendix A.2. Edge-Syndrome Writing Layers (Layers 1–6)

For each neighbor

i, define a reversible unitary

that writes the link syndrome

into the corresponding audit bit

:

leaving all other bits unchanged. This is a permutation on the computational basis and hence unitary.

One decomposition uses two CNOT-type updates:

- 1.

on-site at A: ,

- 2.

two-site across the edge : .

Because only one neighbor edge touches A per micro-layer (by scheduling), this respects (A3).

Appendix A.3. Audit Finalization Layer (Layer 7)

Define an on-site reversible gate

that sets the certification flag if and only if all six syndromes are zero:

This is implementable by standard reversible logic (multi-controlled Toffoli decompositions) but the explicit decomposition is not required for the conceptual point: the finalization is an

on-site aggregation step.

Appendix A.4. Audit Projector for This Toy Construction

A natural audit projector is

(tensored with identity on unused degrees of freedom). In the noiseless toy setting, certification is exact on the computational basis; in noisy settings one uses tolerance

as in (

4).

Appendix B. Atomic → Nuclear Conversion Table (Computed for H, C-12, Au-197, U-238)

We apply (

21) with electronic binding energy approximation (

22). Constants/conventions used:

atomic masses

from NIST isotopic composition tables [

19,

20,

21];

12C mass is exact by definition of the atomic mass scale [

18];

conversion

(CODATA 2018) [

14];

electron mass in u:

(CODATA 2018) [

14].

Table A1.

Computed nuclear masses using

with

from (

22). Values are rounded to the MeV level in energy. The

formula is an approximation used in atomic-mass practice; it is included to make the correction explicit.

Table A1.

Computed nuclear masses using

with

from (

22). Values are rounded to the MeV level in energy. The

formula is an approximation used in atomic-mass practice; it is included to make the correction explicit.

| Isotope |

Z |

(u) |

(MeV) |

(u) |

(GeV) |

(GeV) |

|

1H |

1 |

1.00782503223 |

0.000014 |

1.00727646782 |

0.938783 |

0.938272 |

|

12C |

6 |

12 (exact) |

0.001045 |

11.99671052055 |

11.177929 |

11.174864 |

|

197Au |

79 |

196.96656879 |

0.517344 |

196.92378636837 |

183.473197 |

183.433346 |

|

238U |

92 |

238.0507884 |

0.762670 |

238.00113780810 |

221.742905 |

221.696656 |

Appendix C. Toy FRG Matching That Computes the Attenuation Factor ρ

This appendix provides a minimal, reproducible toy example showing how an explicit UV→IR matching can yield a concrete attenuation factor

in

The goal is not realism (we do

not claim to reproduce the full SM+portal system here), but to make the logical step “UV seed ⇒ IR mass” mathematically explicit and auditable.

Appendix C.1. Set-Up: Scalar Toy model and Wetterich Flow in LPA

Consider a single real scalar field in four Euclidean dimensions with an effective average action in Local Potential Approximation (LPA),

The Wetterich equation reads [

8,

9]

with IR regulator

. Using the Litim regulator

yields closed-form threshold functions [?].

Define the standard dimensionless couplings

(with

dimensionless in

). In a minimal toy truncation, keep

approximately constant over the flow window (this is the

toy simplification), and approximate the mass flow by the one-loop/LPA form (Litim threshold)

In the regime

, one can approximate

and obtain the linearized flow

Appendix C.2. Analytic Solution and Explicit ρ

Solve (

A9) with UV boundary condition at

(i.e.

):

The corresponding dimensionful mass is

, hence

Taking the IR limit

gives

Now identify the UV matching scale with the seed energy:

Then (

A4) and (

A12) yield an explicit attenuation factor

Interpretation (why ρ can be tiny).

Equation (

A14) shows that a very small

corresponds to UV parameters lying close to the critical surface

i.e. near criticality. This is not a “free lunch”; it is a precise statement of what must hold in the UV to generate a much smaller IR mass in this toy truncation.

Appendix C.3. Numerical Illustration Consistent with a Higgs-Resonant Scale (Order of Magnitude)

If one uses the seed scale

(as a

boundary-condition choice) and targets

, then

In the toy formula (

A14), choosing for instance

gives

, so one must set

The point of the example is the

mechanism: the UV parameters must be fixed to (or dynamically attracted to) a near-critical surface to generate huge scale separation. In a full model, the FRG computation of

would be replaced by a specified truncation, regulator choice, and flow integration (and the Higgs-portal sector would be included explicitly).

Appendix D. Detailed Derivation: QFI/Bures ⇒ a Lower Bound on τ

This appendix provides a self-contained derivation (with explicit constants) of a speed-limit-type bound implying

under the definitions used in the main text.

Appendix D.1. Step 1: Certification Threshold in Trace Distance

Let

be a reference state and

the state after time

t (continuous) or after

n micro-layers (discrete). Define trace distance

. For binary hypothesis testing with equal priors, the Helstrom bound states [

6]

Requiring

is equivalent to the threshold

Appendix D.2. Step 2: Relate Trace Distance to Fidelity (Fuchs–van de Graaf)

Let

be the fidelity. The Fuchs–van de Graaf inequalities [??] state

Using the upper bound in (

A21) together with (

A20) implies

Appendix D.3. Step 3: Bures Angle Target

Define the Bures angle

From (

A22), certification implies

Appendix D.4. Step 4: QFI Speed-Limit Inequality

Quantum speed-limit results relate the rate of change of the Bures angle to the quantum Fisher information (QFI) [

7]. A convenient form is

If

for

, then (

A25) yields

Appendix D.5. Step 5: Specialize to Unitary Families and Define χ

For a unitary family

generated by a time-independent Hamiltonian

H, for pure

one has [??]

Motivated by this, define the stiffness parameter (as in the main text)

which has dimensions of

. In this pure/unitary case,

exactly, so we can take

.

Appendix D.6. Conclusion: Explicit Constant C 1 (ε)

Combine (

A24) with (

A26) and

:

Thus, for the operational copy-time definition as the minimal time to reach the certification threshold,

Discrete micro-layer version.

If time is discrete in micro-layers of duration

, so

, then

Scope note (mixed states / time-dependent generators).

For mixed states or time-dependent generators, one uses

along the path and (

A25); the same structure holds with

interpreted as a suitable bound on QFI over the relevant interval. The constant

remains fixed by the certification threshold via (

A24).

References

- P. Arrighi, V. Nesme, and R. F. Werner, Unitarity plus causality implies localizability, J. Comput. Syst. Sci. 77, 372–378 (2011). [CrossRef]

- B. Schumacher and R. F. Werner, Reversible quantum cellular automata, arXiv: quant-ph/0405174 (2004).

- D. A. Meyer, From quantum cellular automata to quantum lattice gases, J. Stat. Phys. 85, 551–574 (1996). [CrossRef]

- E. H. Lieb and D. W. Robinson, The finite group velocity of quantum spin systems, Commun. Math. Phys. 28, 251–257 (1972). [CrossRef]

- M. B. Hastings and T. Koma, Spectral gap and exponential decay of correlations, Commun. Math. Phys. 265, 781–804 (2006). [CrossRef]

- C. W. Helstrom, Quantum Detection and Estimation Theory, Academic Press (1976).

- S. Deffner and S. Campbell, Quantum speed limits: from Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle to optimal quantum control, J. Phys. A: Math. Theor. 50, 453001 (2017). [CrossRef]

- C. Wetterich, Exact evolution equation for the effective potential, Phys. Lett. B 301, 90–94 (1993). [CrossRef]

- J. Berges, N. Tetradis, and C. Wetterich, Non-perturbative renormalization flow in quantum field theory and statistical physics, Phys. Rep. 363, 223–386 (2002). [CrossRef]

- V. Silveira and A. Zee, Scalar phantoms, Phys. Lett. B 161, 136–140 (1985). [CrossRef]

- J. McDonald, Gauge singlet scalars as cold dark matter, Phys. Rev. D 50, 3637–3649 (1994). [CrossRef]

- J. M. Cline, K. Kainulainen, P. Scott, and C. Weniger, Update on scalar singlet dark matter, Phys. Rev. D 88, 055025 (2013). [CrossRef]

- S. Navas et al. (Particle Data Group), Review of Particle Physics, Phys. Rev. D 110, 030001 (2024). [CrossRef]

- E. Tiesinga, P. J. Mohr, D. B. Newell, and B. N. Taylor, CODATA recommended values of the fundamental physical constants: 2018, Rev. Mod. Phys. 93, 025010 (2021). [CrossRef]

- NIST, CODATA Recommended Values of the Fundamental Physical Constants: 2018 (NIST SP 961, May 2019), PDF: https://physics.nist.gov/cgi-bin/cuu/Info/pdf/wall_2018.pdf.

- M. Wang, W. J. Huang, F. G. Kondev, G. Audi, and S. Naimi, The AME 2020 atomic mass evaluation (II). Tables, graphs and references, Chin. Phys. C 45, 030003 (2021). [CrossRef]

- G. Audi et al., The AME2012 atomic mass evaluation (II). Tables, graphs and references, Chin. Phys. C 36, 1603–2014 (2012). [CrossRef]

- NIST, Atomic Weights and Isotopic Compositions – Column Descriptions, https://www.nist.gov/pml/atomic-weights-and-isotopic-compositions-column-descriptions.

- NIST, Atomic Weights and Isotopic Compositions for Hydrogen, https://physics.nist.gov/cgi-bin/Compositions/stand_alone.pl?ascii=ascii&ele=H.

- NIST, Atomic Weights and Isotopic Compositions for Gold, https://physics.nist.gov/cgi-bin/Compositions/stand_alone.pl?ascii=ascii&ele=Au.

- NIST, Atomic Weights and Isotopic Compositions for Uranium, https://physics.nist.gov/cgi-bin/Compositions/stand_alone.pl?ele=U.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).