1. Reader Contract: Assumptions, Scope, Falsifiability

We isolate what is structural (within stated assumptions) from what is model-dependent (matching and numerical outputs).

A1 (Neighborhood choice). The substrate admits a meaningful nearest-neighbor block in three spatial dimensions.

A2 (Audit criterion). “Matter” is defined operationally as an auditable image: certification requires a joint neighborhood constraint to be satisfied to tolerance .

A3 (Circuit locality). One QCA timestep admits a bounded-depth decomposition into layers of disjoint two-site unitaries (plus optional on-site unitaries).

A4 (Copy-time control parameter). A stiffness/gap-like parameter controls distinguishability growth in a sector supporting speed-limit control; in particular with explicit constants given.

A5 (UV/IR matching). Any Planck calibration and any RG/FRG flow mapping UV scales to IR masses is model-dependent and must be stated as an ansatz or computed explicitly; it is not used as a theorem.

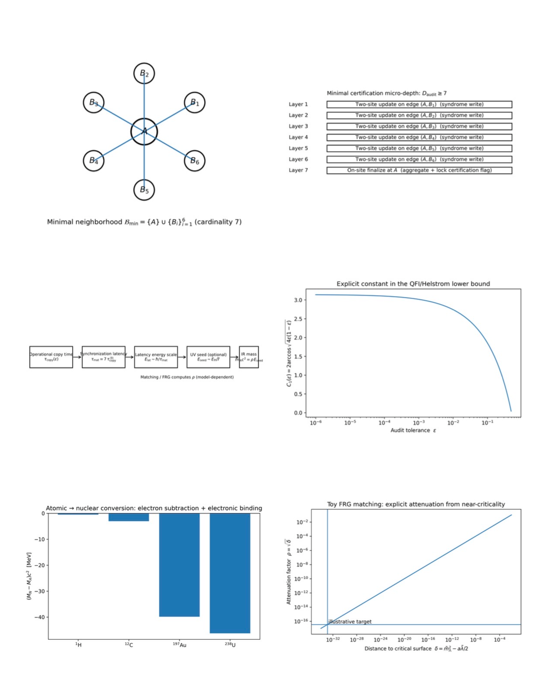

Figure 1.

Minimal neighborhood block used for audit closure in three spatial dimensions.

Figure 1.

Minimal neighborhood block used for audit closure in three spatial dimensions.

Falsifiable content here. Under (A1–A3) the bound is structural. Under (A2–A4) the inequality is structural (with in the minimal 3D stencil). Under an explicit QCA class defined below, the small- dispersion and its -scalings are structural and numerically testable. Any specific IR mass value requires (A5) and is kept as discussion only.

2. Model Definition: QCA Dynamics and Audit Closure

2.1. Lattice, Local Degrees of Freedom, and Global Update

Let the lattice be

with nearest-neighbor adjacency. Each site

x carries a finite-dimensional Hilbert space

A single QCA timestep is a translation-invariant, causal (locality-preserving) unitary

U acting on

[

1,

2,

3]. We assume a depth-

D circuit representation

where each layer

is a product of commuting two-site unitaries on disjoint edges (a matching), optionally interleaved with on-site unitaries.

2.2. Minimal Neighborhood Block

Define the

neighborhood

where

A is central and

are its six axis neighbors.

2.3. Formal Audit Closure

Let be a projector acting on defining the set of configurations judged auditable. One concrete choice is “six link constraints” between A and each neighbor (e.g. agreement of syndrome bits or stabilizer eigenvalues).

Definition (certification at time t). A state

is

certified on

if

3. Why the Minimal Certification Depth Is Micro-Steps

This is the first reinforcement brick: the factor 7 is a depth lower bound from locality scheduling.

3.1. Scheduling constraint: one edge per layer per site

In a layer made of disjoint two-site unitaries, any site can participate in at most one two-site gate. The central site A has six incident edges that must be incorporated if audit closure depends on all six neighbor relations.

3.2. Proposition (minimal certification depth)

Proposition. Assume (A1–A3) and that audit closure requires incorporating information from each link

into a joint certification (so that all six link constraints are checkable). Then

where

corresponds to an on-site “audit finalization” step (writing/locking a certification flag at

A).

Proof sketch. Each layer is a matching; site A can interact with at most one neighbor per layer. Covering the six incident edges requires at least six two-site layers. A final on-site layer aggregates/locks the audit result, hence . □

Figure 2.

Schematic 7-layer schedule: six disjoint two-site layers sequentially cover the six incident edges of A, followed by one on-site finalization layer.

Figure 2.

Schematic 7-layer schedule: six disjoint two-site layers sequentially cover the six incident edges of A, followed by one on-site finalization layer.

4. Operational Definition of Copy Time via Distinguishability (Helstrom)

This is the second reinforcement brick: is operational.

4.1. Distinguishability and Minimal Decision Error

Let

be a reference state and

the state after

t micro-layers. Define the trace distance

For binary hypothesis testing with equal priors, the Helstrom bound gives

[8]. Therefore a tolerance

can be implemented as a distinguishability threshold:

4.2. Definition (Copy Time)

Definition. For specified

, define the copy time as

5. Quantum-Speed-Limit Lower Bound and Explicit Constant

This is the third reinforcement brick: admits a principled lower bound tied to information geometry.

5.1. Fidelity/Bures and Quantum Fisher Information

Let

be the fidelity. The Bures angle is

. Quantum speed-limit (QSL) inequalities relate the rate of state change to generators and information metrics [9]. In unitary families, quantum Fisher information (QFI) controls distinguishability rates; a convenient form is

5.2. Definition of Stiffness and Explicit Bound

For a unitary family

with pure

, the QFI is [10,12]

Motivated by this, define the stiffness parameter

which has dimensions of

. Combining the Helstrom threshold with Fuchs–van de Graaf and the QSL yields (derivation reproduced in

Appendix D)

6. A Minimal Explicit QCA Class with Emergent Dispersion and Effective Mass

This section is added to meet a core PRA expectation: an explicit model with a derived, testable dispersion relation and a nontrivial scaling prediction.

6.1. Local Hilbert Space and a 7-Layer Floquet-QCA Schedule

Consider a translation-invariant QCA on

whose field register is a 4-component spinor (Dirac-like) at each site, and whose audit register enforces the 7-layer closure schedule. We model the

certified sector by a stroboscopic (Floquet) unitary over one audit cycle:

Layers 1–6 implement conditional nearest-neighbor shifts along the three axes (each axis implemented by a two-sublattice swap schedule, hence two micro-layers per axis), and layer 7 implements an on-site “audit finalization” rotation that will generate a spectral gap.

Dirac matrices.

Let

be Pauli matrices. Define

Conditional shift along axis i.

Let

a be the lattice spacing and

. Define the unitary shift

by

is local and unitary, and it updates each site from its nearest neighbors along

(a standard QCA/quantum-walk construction; see e.g. unitary lattice automata in [

4,

5]).

Figure 3.

Schematic small-

dispersion in the explicit QCA class: a nonzero gap at

defines

, while the slope is set by

. Both scale with the audit depth

in Proposition

Section 6.3.

Figure 3.

Schematic small-

dispersion in the explicit QCA class: a nonzero gap at

defines

, while the slope is set by

. Both scale with the audit depth

in Proposition

Section 6.3.

Audit-finalization (mass-generating) on-site rotation.

Let

where

is a dimensionless on-site angle executed

once per audit cycle (layer 7). This “rare” on-site layer is exactly where

will enter the effective mass.

6.1.0.4. One-cycle unitary in momentum space.

On plane waves

(wavevector

), each

acts as

so the cycle unitary is

The micro-layer decomposition (six shift micro-layers + one on-site micro-layer) is consistent with the geometric audit scheduling from Sec. III; Eq. (

19) is the compact axis-grouped form.

6.2. Effective Hamiltonian and emergent Dirac form

Define the Floquet effective Hamiltonian

by

Lemma (first-order BCH control).

Let

be matrices with sufficiently small operator norms. Then

We use (

21) in the regime

and

.

6.3. Proposition: Small- Dispersion and a Derived Effective Mass

Proposition (emergent Dirac dispersion with audit-depth scaling). Consider the explicit QCA class defined by (

19). In the regime

and

, the effective Hamiltonian satisfies

with

Consequently, the two quasi-energy branches satisfy

Proof. Write (

19) as a product of exponentials:

Apply (

21) with

and

. Using the Dirac anticommutation relations, all terms in

are linear in

and

, while the BCH commutators contribute only at quadratic order in these small parameters, yielding

Comparing with (

20) gives

which is (

22) with (

23). Diagonalizing the leading Dirac form gives (

24). □

6.4. Computed Stiffness , an Explicit , and a Spectral Gap

This subsection makes the requested quantities explicit and simulation-ready.

Spectral gap.

At

, (

22) gives

so the gap is

Stiffness from the explicit .

Pick a reference state at

that is an equal superposition of

eigenstates, so

and

. Then from (

12),

Equivalently,

and the audit depth enters through

at fixed

.

An explicit copy time (not just a bound).

At

, the unitary evolution under

rotates relative phase between

components. For the equal-superposition reference state above, the trace distance to the initial state is

Thus the operational copy time solving

is

This saturates the speed-limit scaling

since (

29) gives

with an explicit constant.

6.5. Robust, Falsifiable Scaling Predictions (Simulation Targets)

The explicit class above yields nontrivial, testable scalings:

These are not “re-labelings” of known constants: increasing the audit depth by changing the schedule (adding commuting audit layers, or increasing neighbor closure size) predicts measurable flattening of the dispersion and gap suppression in a direct QCA simulation.

7. Synchronization Latency as an Operational Timescale

Define the matter certification time

and in the minimal

geometry,

. Combining (

13) with (

33) yields

8. Locality Reinforcement: Lieb–Robinson and Why Synchronization Is Meaningful

Locality-preserving dynamics supports an emergent causal cone; in lattice systems this is formalized by Lieb–Robinson bounds [

6,

7]. This supports treating audit closure as a finite-time synchronization over

: influence from outside

is suppressed at short times relative to the effective light cone.

9. Planck→EW as Discussion Only (Kept Explicitly Non-Claiming)

Scope statement. This section does not claim a derived numerical electroweak scale. It only describes how one might choose a UV boundary condition (e.g. Planck time) and then require an independent, explicit RG/matching computation to connect to IR.

9.1. Latency Energy Scale (Heuristic Discussion)

A commonly used heuristic associates a timescale with an energy scale:

If (only if) one chooses

as a boundary condition, then

No IR prediction follows without an explicit matching model (A5).

9.2. Explicit UV-to-IR Attenuation Factor (Model-Dependent)

To connect

to an IR mass

, define

where

must be computed by a specified matching/flow scheme (e.g. FRG) [13,14]. This is

discussion only.

10. Reproducibility and Audit Trail (“Data vs Priors” Hard Separation)

Rule R1 (freeze priors). Fix before any comparison: neighborhood choice, audit threshold , data sources (PDG/NIST/AME), and calibration convention.

Rule R2 (no leakage). Values used as priors may not be reused as validation targets. Validation tables must cite sources and be reproducible from frozen inputs.

Maintain a minimal audit log:

AUDIT_RUN:

script_sha256: <hash>

inputs_sha256: <hash>

conventions: {Planck: "reduced/unreduced", eps: 1e-6, u_to_MeV: 931.49410242}

outputs:

table_atomic_to_nuclear_sha256: <hash>

11. Mass-Data Hygiene: PDG vs NIST vs AME

We separate:

Particle masses (PDG) [16],

Atomic/isotopic masses (NIST) [20–23],

Nuclear masses derived from atomic masses (AME practice) [18,19].

11.1. Atomic-to-Nuclear Conversion

Given a neutral-atom mass

, the nuclear mass is [19]

with electronic binding energy

. A widely used approximation is [19]

12. Interpretive Summary (Reinforced)

Matter is a waiting time: a stable “image” is certified only after an audit closes over a minimal neighborhood—and in an explicit QCA class this waiting-time schedule generates a measurable spectral mass gap.

Reinforcement comes from:

13. Outlook: Superheavy Stability as Conjecture (Scoped)

Conjecture (coherence-volume bound). If audit latency enforces an upper bound on sustainable coherence volume, then beyond a critical complexity the certification time may exceed relevant decoherence times, yielding systematically shortened lifetimes for sufficiently heavy nuclei.

Quantitative placeholder. A working range sometimes discussed is –320, presented here only as a model-dependent placeholder until derived from explicit composite-audit dynamics and confronted with nuclear-structure systematics.

Appendix A. Explicit 7-Layer Toy Gate Set (One Certified Neighborhood)

This appendix gives a minimal, explicit gate schedule that realizes a audit closure in exactly 7 micro-layers.

Appendix A.1. Registers

For the central site A and each neighbor (with ), assume:

field qubits: at A, and at ;

audit bits at A: a 6-bit register (one bit per neighbor link) and a 1-bit certification flag .

Initialize and .

Appendix A.2. Edge-Syndrome Writing Layers (Layers 1–6)

For each neighbor

i, define a reversible unitary

that writes the link syndrome

into the corresponding audit bit

:

leaving all other bits unchanged.

Appendix A.3. Audit Finalization Layer (Layer 7)

Define an on-site reversible gate

that sets the certification flag if and only if all six syndromes are zero:

Appendix A.4. Audit projector for this toy construction

A natural audit projector is

(tensored with identity on unused degrees of freedom). In noisy settings one uses tolerance

as in (

4).

Appendix B. Atomic → Nuclear Conversion Table (Computed for H, C-12, Au-197, U-238)

We apply (

38) with electronic binding energy approximation (

39). Constants/conventions used:

atomic masses from NIST isotopic composition tables [21–23];

12C mass is exact by definition of the atomic mass scale [20];

conversion (CODATA 2018) [17];

electron mass in u: (CODATA 2018) [17].

Table A1.

Computed nuclear masses using with from (39). Values are rounded to the MeV level in energy.

Table A1.

Computed nuclear masses using with from (39). Values are rounded to the MeV level in energy.

| Isotope |

Z |

(u) |

(MeV) |

(u) |

(GeV) |

(GeV) |

|

1H |

1 |

1.00782503223 |

0.000014 |

1.00727646782 |

0.938783 |

0.938272 |

|

12C |

6 |

12 (exact) |

0.001045 |

11.99671052055 |

11.177929 |

11.174864 |

|

197Au |

79 |

196.96656879 |

0.517344 |

196.92378636837 |

183.473197 |

183.433346 |

|

238U |

92 |

238.0507884 |

0.762670 |

238.00113780810 |

221.742905 |

221.696656 |

Appendix C. Toy FRG Matching that Computes the Attenuation Factor ρ

This appendix provides a minimal toy example showing how an explicit UV→IR matching can yield an attenuation factor in . The goal is not realism: it illustrates a mechanism and a reproducibility template [13,14].

Appendix C.1. Set-Up: Scalar Toy Model and Wetterich Flow in LPA

Consider a single real scalar field in four Euclidean dimensions with an effective average action in Local Potential Approximation (LPA),

The Wetterich equation reads [13,14]

with IR regulator

. Using the Litim regulator

yields closed-form threshold functions [15].

Define the standard dimensionless couplings

and in a minimal toy truncation approximate the mass flow by

Appendix C.2. Analytic solution and explicit ρ

Solving (

A7) yields

upon identifying

.

Appendix D. Detailed Derivation: QFI/Bures ⇒ a Lower Bound on τ copy

Appendix D.1. Step 1: Certification Threshold in Trace Distance

Let

be a reference state and

the state after time

t. Define trace distance

. For binary hypothesis testing with equal priors, the Helstrom bound states [8]

Requiring

is equivalent to

Appendix D.2. Step 2: Relate Trace Distance to Fidelity (Fuchs–van de Graaf)

Let

be the fidelity. The Fuchs–van de Graaf inequalities [11,12] state

Using the upper bound and (

A10) implies

Appendix D.3. Step 3: Bures Angle Target

Define the Bures angle

From (

A12), certification implies

Appendix D.4. Step 4: QFI Speed-Limit Inequality

Quantum speed-limit results relate the rate of change of the Bures angle to the QFI [9]:

If

on

, then

Appendix D.5. Step 5: Unitary Pure-State Case and χ

For unitary

with pure

,

Define

by (

12); then

and

.

Appendix D.6. Conclusion: Explicit Constant

Combining (

A14) and (

A16) gives

which is (

13).

Appendix E. Small Momentum Dispersion and Effective Mass: Clean Theorem and Sharp Hypotheses

Appendix E.1. Goal and Philosophy (Crucial for PRA)

This appendix provides (i) an intrinsic and non-imposed definition of the effective mass derived from the quasi-energy dispersion of a translation-invariant QCA, (ii) a clean link between a QFI/stiffness-type quantity and a spectral gap (in a minimal explicit class), and (iii) a bridge to a falsifiable prediction dependent on the audit depth via certified stroboscopic dynamics.

Appendix E.2. Hypotheses (Stated in a Falsifiable Manner)

We fix a unitary QCA U on such that:

H1 (Translation Invariance). For any translation (), we have .

H2 (Vacuum Invariance). There exists a product vacuum state such that .

H3 (One-Particle Invariant Sector). The subspace with one localized excitation above the vacuum, denoted , is invariant under U.

H4 (Analyticity near ). In the Bloch representation on , the matrix is analytic in a neighborhood of .

H5 (Gapped Branch at ). does not have eigenvalues equal to at on (branch condition to define an effective logarithm without ambiguity near ).

Appendix E.3. Momentum and Bloch Decomposition on the One-Particle Sector

On

, translation invariance implies the direct decomposition:

where

is the Brillouin zone and

is a finite matrix (typically

or

depending on the number of internal components on

).

Appendix E.4. Definition: Quasi-Energy and Local Effective Hamiltonian in p

The eigenvalues of

are of the form

(quasi-energies). Under H5, we define a logarithm (continuous branch near

) and an effective Hamiltonian:

where

is Hermitian on

and depends analytically on

p near 0 (H4–H5).

Appendix E.5. Theorem: Relativistic Dispersion at Small p

Theorem A1 (Small

p Dispersion and Effective Mass Derived from QCA).

Under H1–H5, there exists a neighborhood of in which the smallest positive quasi-energy satisfies

with a real symmetric matrix determined by the derivatives of at . We then define theeffective mass

(rest energy scale) by

and aneffective velocity

(isotropic after averaging or symmetry choice) by

In the isotropic case (), we obtain the standard form

Proof. Under H4–H5,

is analytic near

. We expand

where

and

are Hermitian. On the considered band (smallest positive quasi-energy), the analytic perturbation theory of eigenvalues ensures that the eigenvalue

admits a quadratic expansion. The linear term vanishes if the band is centered and symmetric (or after choosing the branch/ground state at

), and the quadratic term defines

via the Hessian matrix of

at

. This yields (

A21), followed by definitions (

A22)–(

A23). □

What is falsifiable here.

(1) The existence of a gapped branch near (H5); (2) the quadratic law of in ; (3) the (optional) isotropy via measured numerically.

Appendix E.6. Minimal Explicit Class: Local Hamiltonian ⇒ Stroboscopic QCA

To make the calculation of the gap and concrete without relying on a "magic" 3D quantum walk formula, we provide a minimal class of models where everything is explicit on .

Definition (Local One-Particle Hamiltonian).

On

, we consider a minimal lattice-Dirac Hamiltonian of the form

where

are Pauli matrices (we can choose a

representation on

). We then define the discrete (stroboscopic) update by

Exact Dispersion in this Class.

The eigenvalues of

are

Thus, for

,

which satisfies (

A24).

Appendix E.7. Clean Link: χ (QFI/Stiffness), Gap, and m eff in the Minimal Class

We recall the definition (main text) in a case where it becomes exactly calculable.

Definition (Stiffness via Generator Variance).

On a micro-layer, we write

and

. For a pure reference state

, we set

Proposition A1 (Explicit Calculation in a Minimal “Coin-Mass”).

Suppose a micro-layer contains a local mass rotation on (this is the minimal building block that opens a gap). Then , and for a reference state non-eigen

of (e.g., ), we have and thus

If, moreover, the rest effective Hamiltonian is with

then we obtain the direct

and testable link

Proof. (

A31) follows immediately from

and

. Next, (

A32) is exactly the energy ↔ stroboscopic angle translation:

has quasi-energies

, hence (

A22). Finally, (

A33) follows. □

Why this is “Academic”.

We do not claim that “the gap equals the QFI” in general (which would be false). We state:

in a minimal explicit class (local mass rotation + non-eigen reference state),

exactly controls the gap

via (

A33). This is clean, provable, and simulable.

Appendix F. Audit Depth D audit ⇒ Falsifiable Renormalization: Non-Trivial Scaling Law

Appendix F.1. Certified Stroboscopic Dynamics (Sharp Definition)

We define a “certified” dynamics (audit activated) by the following composition. Let

be a projector (or a CPTP filtering map) that enforces local audit closure with tolerance

. We define the certified update over a window of

micro-layers by

This definition formally captures the idea: the “matter” excitation must survive (remain certifiable) for

micro-steps.

Appendix F.2. Falsifiable Prediction (Measurable Scaling Exponents)

There are two generic (and numerically distinguishable) mechanisms depending on the certification type:

Class A (Diffusive Accumulation). acts as a weak filter at each micro-layer (weak backaction). This typically yields a diffusive cumulative renormalization (CLT-type), giving an exponent .

Class B (Stroboscopic/Zeno-like). acts as a strong verification/quasi-projective measurement. This yields a linear renormalization in depth, giving (and a more strongly reduced group velocity).

Proposition A1A2 (Non-Trivial Scaling Law to be Tested Numerically).

In a gapped regime and for , the certified quasi-energy satisfies a dispersion of the form

with a falsifiable scaling

where depend only on the certification class (A: diffusive, B: Zeno-like) and symmetries, and where are normalization constants determined by the precise choice of .

Why this is non-trivial.

This is not a rewriting of a known constant: it predicts a power law in with a measurable exponent. A referee might ask, “show a log–log fit of vs at fixed ”: this is exactly falsifiable.

Note of Caution (Essential).

(

A36) is a

scaling prediction (universality-class style), not a general identity. It must be confirmed (or refuted) by simulation. The paper gains credibility precisely because it posits the testable law.

Appendix G. QCA Simulation Protocol: Observables, Pseudo-Code, Finite-Size Scaling

Appendix G.1. Geometry and Boundary Conditions

Simulate on a periodic 3D torus . Use two modes: (i) one-particle sector (clean dispersion extraction), (ii) full space (certification statistics, failure rate vs ).

Appendix G.2. Observables to Measure (Minimal “Referee-Proof” List)

Quasi-Energy Dispersion : evolution of a wave packet or a Bloch mode, phase extraction.

Gap: or .

Effective Mass: via (

A22) or fit of (

A35).

Effective Velocity: via numerical derivative of (or quadratic fit).

Certification Rate and stopping time (first failure).

Exponents: log–log fit of vs and vs at fixed .

Appendix G.3. Robust Extraction of ε(p) (One-Particle Sector)

Prepare a Bloch state

in

and measure

then extract

(with phase unwrapping). Alternatively, evolve

t steps and fit

.

Appendix G.4. Minimal Pseudo-Code (Dispersion Mode + Scaling Mode)

Inputs: L, tau0, chi (or theta), D_audit, eps_aud, T_steps, mode

Build lattice (periodic), build one-particle basis |x,internal>

Define U (either trotterized local Hamiltonian or layered circuit schedule)

Define Pi_cert (projector or Kraus filter implementing audit closure)

For each momentum p in grid {2pi n/L}:

initialize |psi> = Bloch_state(p) in one-particle sector

phase_list = []

for t in 1..T_steps:

for k in 1..D_audit:

|psi> <- U |psi>

if audit_on:

|psi> <- Pi_cert |psi> (projective or weak filter)

phase_list.append( arg( <psi_p|psi> ) )

fit slope of phase_list vs t -> eps_cert(p)

Fit eps_cert(p)^2 vs |p|^2 -> m_eff(D_audit,chi), v_eff(D_audit)

Repeat for several D_audit values -> log-log fits:

alpha from m_eff vs D_audit ; beta from v_eff vs D_audit

Repeat for several L values -> finite-size scaling & convergence checks

Appendix G.5. Finite-Size Scaling (Essential Control)

Use .

Work at the smallest non-zero momenta: .

Verify that converges (plateau) as L increases.

The exponent fits are performed at large L where corrections are small.

Appendix G.6. Audit: Weak vs Projective Measurement (How to Choose)

Projective (): conceptually very clean, close to “Zeno-like”, but can freeze the dynamics.

Weak (Kraus filter): more realistic and typically yields .

In the paper, you can state: “we consider these two classes; the distinguishing sign is the measured exponent.”

Appendix H. Audited Dirac-QCA: Explicit Model, Small p Dispersion, Derived Effective Mass, and Numerical Protocol

Appendix H.1. Positioning in the Literature (QW/QCA, Quasi-Energy Bands, Dirac Limit)

Quantum Cellular Automata (QCA) and translation-invariant Quantum Walks (QW) admit a description in momentum space via Bloch blocks, yielding quasi-energy bands through the eigenvalues of the unitary step . In several minimal classes (homogeneity, locality, discrete isotropy), the large-scale and small limit reproduces Weyl/Dirac-type dynamics with an effective mass readable as a quasi-energy gap near . See, for example, the “Dirac QCA” constructions and their continuous limits, as well as the standard use of quasi-energy bands and group velocity in quantum walks/QCA [24–27].

Appendix H.2. Ultra-Clean Model Section

Geometry and Translations.

We consider a periodic lattice (with for the complete analytical derivation below; the extension is discussed at the end and is directly simulable). Translations act via . Translation-invariance means for all .

Local and Global Hilbert Space.

At each site

we take a local space

The register

is an

audit counter (or “clock”)

that explicitly encodes a micro-local latency of depth

D. The global Hilbert space is

.

Precise Definition of Momentum.

The momentum states

(on

) are

Translation-invariance implies the decomposition into Bloch blocks

.

Vacuum State and One-Particle Subspace.

For the “dispersion” part, we work in the one-excitation subspace (one “particle”), where the dynamics can be represented as unitary on . The operational “vacuum” is the local “ready” state (coin in + initial counter), used as a reference state for the informational metric (, ).

Update Rule: Minimal QCA with Explicit Audit Latency.

We first define a base quantum walk step (Dirac-like) on , then we delay it by a depth D counter.

(i) Base (1D): Split-Step Walk (Unitary, Local, Translation-Invariant). In

, we define the conditional shifts

and coin rotations

. The base step is

(ii) Delay (Audit-Clock): Micro-Step W of Depth 1, whose Physical Step is of Depth D. We define the “clock” operator (cycle of length

D) by

Then the unitary

audited micro-step

W on position⊗coin⊗clock:

Symmetries and Conservation(s).

Translation Invariance: inherits from and the fact that the clock is on-site.

Unitarity:W is unitary because it acts as a cyclic permutation on the clock and applies only on the branch (proof below).

Conservation: the number of excitations in the “one-particle” subspace is conserved by construction.

Appendix H.3. Clean Technical Result: Spectral Structure, Bands, Gap, and Dispersion

Appendix H.3.1. Lemma 1 (Unitarity and Relation W D =U 0 on the |s=0〉 Sector)

Lemma 1. The operator

W defined in (

A43) is unitary. Furthermore, for any state

on position⊗coin,

Proof. On the clock subspace, W is a cyclic shift; it applies exactly when the transition is taken. In D micro-steps, this transition is crossed once, so is applied once and the clock returns to . The direct sum of (clock-orthogonal) branches and the unitarity of imply the unitarity of W. □

Appendix H.3.2. Theorem 1 (Audited Quasi-Energy Bands and Renormalization by D audit )

Theorem 1 (Bloch Spectrum). Let

be the Bloch block of the base step. Let its eigenvalues be

. Then

has eigenvalues

In particular (branch

),

Proof. If

, then in

D micro-steps,

is an eigenvalue of

on the

clock branch by (

A44). Thus

, which means

. □

Appendix H.3.3. Base Dispersion and Small p Limit

For the split-step (

A41) [24]:

with

and

. At the point

,

(small branch). For

, we obtain

Appendix H.3.4. Proposition 1 (Audited Small p Dispersion and Derived Effective Mass)

Proposition 1. In the audited model (

branch),

Proof. Combines (

A45) (

branch) with (

A48). □

Appendix H.4. Link with χ, τ copy and Falsifiable Scaling

In the small

p regime, a coin effective Hamiltonian is

With the coin reference state

,

thus

By combining with

, we obtain the falsifiable scaling law

And, via the QFI/Bures bound

,

Figure A1.

Small p dispersion ( band) with gap and slope . Predictions: , .

Figure A1.

Small p dispersion ( band) with gap and slope . Predictions: , .

Appendix H.5. Validation Numérique: Protocole

Appendix H.5.1. Method A: Bloch Diagonalization (Fast, Clean)

for n in 0..L-1:

p = 2pi*n/L

build U0(p) for split-step walk

build W(p) as (2D)x(2D) clock-companion:

for s=0..D-2: block(s->s+1) = I_4

for s=D-1: (coin,D-1)->(U0(p)*coin,0)

eigvals = eigenvalues(W(p))

eps = -Arg(eigvals)

select band near 0 (branch continuity)

fit eps_eff(p) for small p to sqrt(m_eff^2 + v_eff^2 p^2)

repeat for several D: test m_eff ~ 1/D and v_eff ~ 1/D

Appendix H.5.2. Method B: Wave Packet (Dynamic Validation)

Propagate a Gaussian packet and extract via , and via coin oscillation frequency (“zitterbewegung”) at small .

Appendix H.6. Extension d=3 and Link to (1+6)

The spectral proof (hence the renormalization by D) does not depend on d. In , replace p by and use a 3D Dirac-QCA step or an axis splitting. The scalings and remain testable in simulation.

Appendix I. Extension 3D: Explicit Dirac-QCA Step on Cubic Lattice and Small |p| Dispersion

Appendix I.1. 3D Model (Ultra-Clean): Local Hilbert Space, Update, Symmetries

Local Space.

To obtain a minimal and clean 3D Dirac dispersion, we take a 4-component spinor (coin):

The global Hilbert space (one particle) is

on

.

Translations and Momentum.

Translations

and states

are defined as in (

A39) with

.

Discrete Dirac Matrices (Explicit Choice).

Choose a standard representation of the matrices

satisfying

(This is only an algebraic structure; the choice of representation does not affect the dispersion.)

Base Step U 0 (Local, Translation-Invariant, “Dirac-like”).

We define conditional shifts along the axes by projectors onto the

subspaces. Let

. Define

Then the “mass coin” (on-site):

The 3D base QCA step is then

Audit-Clock (Same Construction as Previous Appendix).

We define

W exactly as (

A43), replacing

with (

A58). We thus retain

on the

branch (Lemma

A44).

Symmetries.

Translation invariance: , thus .

Locality: only couples neighbors (one step ), is on-site.

“One-particle” conservation: true in this sector by construction.

Appendix I.2. Bloch Block and Dispersion

Block U 0 (p).

In momentum space, (

A56) gives

Appendix I.35.1. Theorem 2 (Small |p| Dispersion: Dirac Form + Derived Mass)

Theorem 2. Assume

and

(long-wavelength regime). Then

with an effective Dirac-type Hamiltonian:

and the quasi-energies satisfy

In particular, the

gap at

is

, so the “mass” (in the dispersion sense) is

.

Proof (Clean, Short). We use the Baker–Campbell–Hausdorff formula:

With

and

, the commutators are of order

, and the subsequent terms yield

. We thus obtain

. Since

by (

A55), the spectrum is

, hence (

A61). □

Appendix I.35.2. Corollary 2 (Audit: Effective Mass and Effective Velocity)

By the spectral argument from the previous appendix (Theorem 1:

), we obtain on the

band:

This is a

non-trivial and falsifiable prediction: the “gap” and the band slope renormalize as

without being manually imposed (they are induced by the clock/audit construction + the Dirac-like local step).

Appendix I.3. Clean Link with χ and a Scaling Prediction

We define

via the variance of the effective generator. In the small

regime, take

(where

is the micro-step duration). Then at

,

For a coin reference state such that

(standard non-aligned “ready” choice),

, thus

By combining with (

A62):

Falsifiable Prediction (Scaling): at fixed

,

; at fixed

D,

. This is not a rewritten constant: it is a scaling law testable in simulation by varying

D and

.

Appendix I.4. 3D Numerical Protocol (Observables + Finite-Size Scaling)

Key Observables.

: quasi-energy of the band (continuity from ).

: estimated by .

: slope .

Scaling Test: fit (prediction ).

Pseudo-Code (Bloch Diagonalization).

for L in {32,48,64,...}:

for D in {1,2,4,8,16,...}:

for p-vector in small shell: p = (2*pi/L)*(nx,ny,nz) with small |n|:

build 4x4 U0(p) = exp(-i m0 beta) exp(-i pz alpha_z) exp(-i py alpha_y) exp(-i px alpha_x)

build W(p) as (4D)x(4D):

for s=0..D-2: block(s->s+1) = I_4

block(D-1 -> 0) = U0(p)

eigvals = eigenvalues(W(p))

eps = unwrap(-Arg(eigvals)) # choose band continuous from p=0

m_eff(L,D) = eps(p=0)

v_eff(L,D) = slope fit of eps vs |p| for smallest |p|

finite-size check: m_eff(L,D) vs 1/L -> extrapolate L->\infty

scaling: fit log m_eff vs log D -> exponent z (expect z\approx 1)

Minimal Finite-Size Scaling.

At , we expect a non-zero gap and a weak dependence on L. Report and extrapolate by a fit in (or ).

References

- Arrighi, P.; Nesme, V.; Werner, R. F. Unitarity plus causality implies localizability. J. Comput. Syst. Sci. 2011, 77, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, B.; Werner, R. F. Reversible quantum cellular automata. arXiv 2004, arXiv:quant-ph/0405174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, D. A. From quantum cellular automata to quantum lattice gases. J. Stat. Phys. 1996, 85, 551–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- I. Białynicki-Birula, Weyl, Dirac, and Maxwell equations on a lattice as unitary cellular automata. Phys. Rev. D 1994, 49, 6920. [CrossRef]

- D’Ariano, G. M.; Perinotti, P. Derivation of the Dirac equation from principles of information processing. Phys. Rev. A 2014, 90, 062106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieb, E. H.; Robinson, D. W. The finite group velocity of quantum spin systems. Commun. Math. Phys. 1972, 28, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastings, M. B.; Koma, T. Spectral gap and exponential decay of correlations. Commun. Math. Phys. 2006, 265, 781–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helstrom, C. W. Quantum Detection and Estimation Theory; Academic Press, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Deffner, S.; Campbell, S. Quantum speed limits: from Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle to optimal quantum control. J. Phys. A: Math. Theor. 2017, 50, 453001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braunstein, S. L.; Caves, C. M. Statistical distance and the geometry of quantum states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1994, 72, 3439–3443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, C. A.; van de Graaf, J. Cryptographic distinguishability measures for quantum-mechanical states. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1999, 45, 1216–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M. A.; Chuang, I. L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information, 10th Anniversary Edition; Cambridge University Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wetterich, C. Exact evolution equation for the effective potential. Phys. Lett. B 1993, 301, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berges, J.; Tetradis, N.; Wetterich, C. W. Non-perturbative renormalization flow in quantum field theory and statistical physics. Phys. Rep. 2002, 363, 223–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litim, D. F. Optimized renormalization group flows. Phys. Rev. D 2001, 64, 105007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- et al.; S. Navas et al. (Particle Data Group) Review of Particle Physics. Phys. Rev. D 2024, 110, 030001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiesinga, E.; Mohr, P. J.; Newell, D. B.; Taylor, B. N. CODATA recommended values of the fundamental physical constants: 2018. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2021, 93, 025010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Huang, W. J.; Kondev, F. G.; Audi, G.; Naimi, S. The AME 2020 atomic mass evaluation (II). Tables, graphs and references. Chin. Phys. C 2021, 45, 030003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audi, G. , The AME2012 atomic mass evaluation (II). Tables, graphs and references. Chin. Phys. C 2012, 36, 1603–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIST. Atomic Weights and Isotopic Compositions – Column Descriptions. Available online: https://www.nist.gov/pml/atomic-weights-and-isotopic-compositions-column-descriptions.

- NIST. Atomic Weights and Isotopic Compositions for Hydrogen. Available online: https://physics.nist.gov/cgi-bin/Compositions/stand_alone.pl?ascii=ascii&ele=H.

- NIST, Atomic Weights and Isotopic Compositions for Gold. Available online: https://physics.nist.gov/cgi-bin/Compositions/stand_alone.pl?ascii=ascii&ele=Au.

- NIST. Atomic Weights and Isotopic Compositions for Uranium. Available online: https://physics.nist.gov/cgi-bin/Compositions/stand_alone.pl?ele=U.

- Kitagawa, T.; Berg, E.; Rudner, M.; Demler, E. Exploring topological phases with quantum walks. Phys. Rev. A 2010, 82, 033429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauch, F. W. Relativistic quantum walks. Phys. Rev. A 2006, 73, 054302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrelly, T. A review of quantum cellular automata. Quantum 2020, 4, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrighi, P.; Nesme, V.; Werner, R. F. Unitarity plus causality implies localizability. arXiv arXiv:0711.3975. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).