Submitted:

23 December 2025

Posted:

23 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

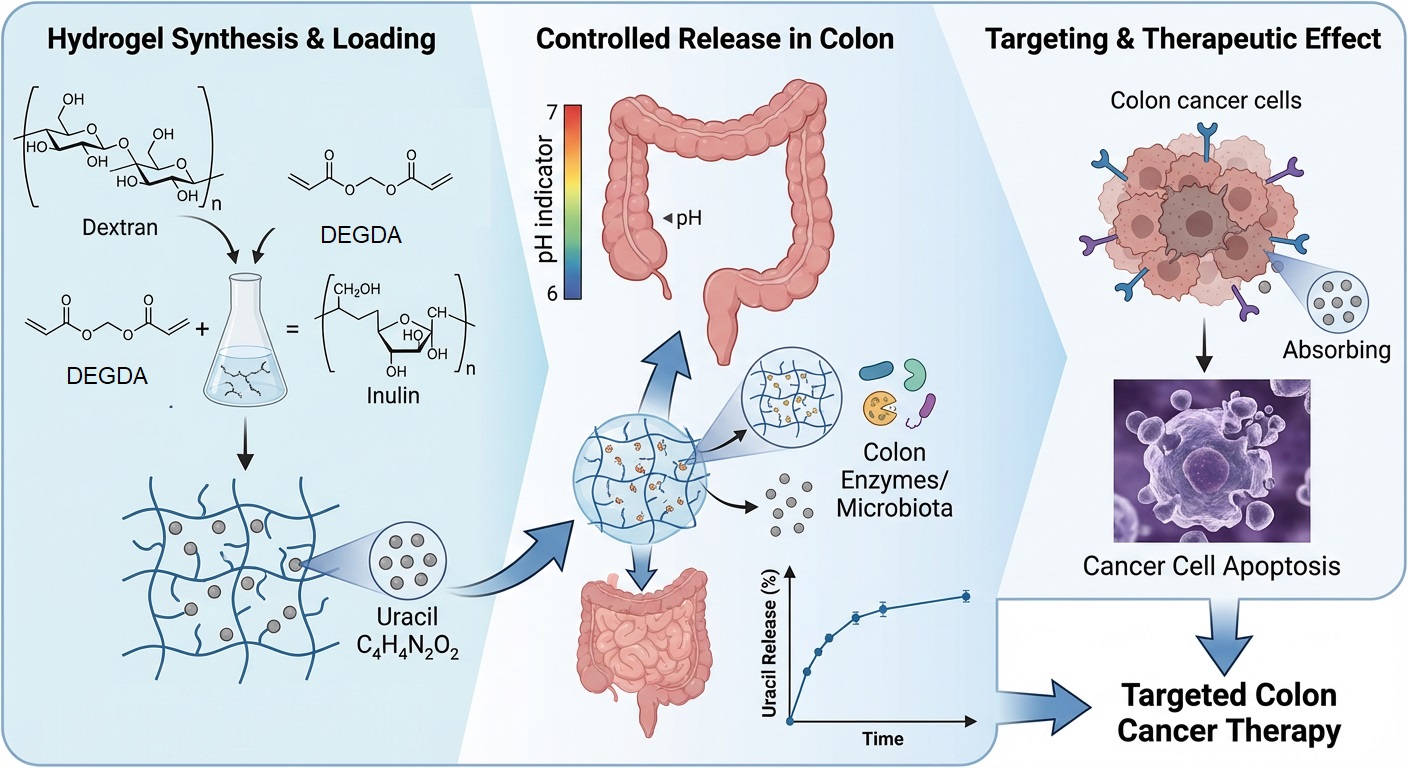

Colon-targeted drug delivery systems are of considerable interest for improving the therapeutic efficacy of anticancer agents while minimizing systemic side effects. In this study, semi-interpenetrating polymer network (semi-IPN) hydrogels based on methacrylated dextran and native inulin were designed as biodegradable carriers for the colon-specific delivery of uracil as a model antitumor compound. The hydrogels were synthesized via free-radical polymerization, using diethylene glycol diacrylate (DEGDA) as a crosslinking agent at varying concentrations (5, 7.5, and 10 wt%), and their structural, thermal, and biological properties were systematically evaluated. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) confirmed successful crosslinking and physical incorporation of uracil through hydrogen bonding. At the same time, differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) revealed an increase in glass transition temperature (Tg) with increasing crosslinking density (149, 153, and 156 °C, respectively). Swelling studies demonstrated relaxation-controlled, first-order swelling kinetics under physiological conditions (pH 7.4, 37 °C), and high gel fraction values (84.75, 91.34, 94.90%, respectively) indicated stable network formation. All formulations exhibited high encapsulation efficiencies (>86%), which increased with increasing crosslinker content, consistent with the observed gel fraction values. Simulated in vitro gastrointestinal digestion showed negligible drug release under gastric conditions and controlled release in the intestinal phase, primarily governed by crosslinking density. Antimicrobial assessment against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus epidermidis, used as an initial or indirect indicator of cytotoxic potential, revealed no inhibitory activity, suggesting low biological reactivity at the screening level. Overall, the results indicate that DEGDA-crosslinked dextran/inulin semi-interpenetrating polymer network (semi-IPN) hydrogels represent promising carriers for colon-targeted antitumor drug delivery.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Results of Infrared spectroscopy with Fourier transformation (FTIR) analysis

2.2. Results of DSC analysis

2.3. Results of swelling properties analysis

2.4. Results of gel fraction (GF) determination

2.5. Results of encapsulation efficiency (EE) determination

2.6. Results of simulated in vitro gastrointestinal digestion (GID)

2.7. Results of antimicrobial assessment

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Preparation of hydrogels

4.3. Infrared spectroscopy with Fourier transformation (FTIR) analysis

4.4. DSC analysis

4.5. Analysis of swelling properties

4.6. Gel fraction determination

4.7. Determination of encapsulation efficiency

4.9. Simulated in vitro gastrointestinal digestion (GID)

4.8. Antimicrobial assessment

4.9. Statistical analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DMF | Dimethylformamide |

| BMAAM | Bis(methacryloylamino)azobenzene |

| HEMA | 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate |

| MA | Methacrylic acid |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| 4-DMAP | 4-Dimethylaminopyridine |

| AIBN | Azobisobutyronitrile |

| DEGDA | Diethylene glycol diacrylate |

| Dex–MA | Dextran-methacrylate |

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global Cancer Statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, Q.; Xia, G.; Adilijiang, N.; Li, Y.; Hou, Z.; Fan, Z.; Li, J. Recent Advances in Targeted Drug Delivery Strategy for Enhancing Oncotherapy. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Tummala, H. Development of Soluble Inulin Microparticles as a Potent and Safe Vaccine Adjuvant and Delivery System. Mol. Pharm. 2013, 10, 1845–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getachew, M.; Atnaf, A.; Kiflu, M.; 1, A.B.; et al. Inulin-based colon targeted drug delivery systems: advancing site-specific therapeutics. Title of Thesis. Level of Thesis;Discov Mater., Degree-Granting University, Location of University, Date of Completion, 2025; p. 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala-Fuentes, J.C.; Gallegos-Granados, M.Z.; Villarreal-Gómez, L.J.; Antunes-Ricardo, M.; Grande, D.; Chavez-Santoscoy, R.A. Optimization of the Synthesis of Natural Polymeric Nanoparticles of Inulin Loaded with Quercetin: Characterization and Cytotoxicity Effect. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, H.; Liu, M.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, Y. Polysaccharide-based Drug Delivery Targeted Approach for Colon Cancer Treatment: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 302, 139177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultin, E.; Nordström, L. Investigations on Dextranase. I. On the Occurrence and the Assay of Dextranase. Acta Chem. Scand. 1949, 3, 1405–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hehre, E.J.; Sery, T.W. Dextran-Splitting Anaerobic Bacteria from the Human Intestine. J. Bacteriol. 1952, 63, 424–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drasar, B.S.; Hill, M.J. Human Intestinal Flora; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1974; pp. 15–43. [Google Scholar]

- Sery, T.W.; Hehre, E.J. Degradation of Dextrans by Enzymes of Intestinal Bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 1956, 71, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensink, M.A.; Frijlink, H.W.; van der Voort Maarschalk, K.; Hinrichs, W.L.J. Inulin, a Flexible Oligosaccharide. I: Review of Its Physicochemical Characteristics. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 130, 405–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giri, S.; Dutta, P.; Giri, T.K. Inulin-Based Carriers for Colon Drug Targeting. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2021, 64, 102595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flint, H.J.; Scott, K.P.; Duncan, S.H.; Louis, P.; Forano, E. Microbial Degradation of Complex Carbohydrates in the Gut. Gut Microbes 2012, 3, 289–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hovgaard, L.; Brøndsted, H. Dextran Hydrogels for Colon-Specific Drug Delivery. J. Control. Release 1995, 36, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.S.; Oh, I.J. Drug Release from the Enzyme-Degradable and pH-Sensitive Hydrogel Composed of Glycidyl Methacrylate Dextran and Poly(acrylic Acid). Arch. Pharm. Res. 2005, 28, 983–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Mooter, G.; Vervoort, L.; Kinget, R. Characterization of Methacrylated Inulin Hydrogels Designed for Colon Targeting: In Vitro Release of BSA. Pharm. Res. 2003, 20, 303–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afinjuomo, F.; Barclay, T.G.; Song, Y.; Parikh, A.; Petrovsky, N.; Garg, S. Synthesis and Characterization of a Novel Inulin Hydrogel Crosslinked with Pyromellitic Dianhydride. React. Funct. Polym. 2019, 134, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maris, B.; Verheyden, L.; Van Reeth, K.; Samyn, C.; Augustijns, P.; Kinget, R.; Van den Mooter, G. Synthesis and Characterisation of Inulin-Azo Hydrogels Designed for Colon Targeting. Int. J. Pharm. 2001, 213, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erceg, T.; Radosavljević, M.; Miljić, M.; Cvetanović Kljakić, A.; Baloš, S.; Špoljarić, K.M.; Ćorić, I.; Glavaš-Obrovac, L.; Torbica, A. The Influence of Synthesis Parameters on the Properties of Dextran-Based Hydrogels for Colon-Targeted Antitumor Drug Delivery Part I: Room Temperature Synthesis of Dextran/Inulin Hydrogels for Colon-Targeted Antitumor Drug Delivery. Gels 2025, 11, 1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erceg, T.; Radosavljević, M.; Miljić, M.; Cvetanović-Kljakić, A.; Baloš, S.; Mišković Špoljarić, K.; Ćorić, I.; Glavaš-Obrovac, L.; Torbica, A. Part II: The Influence of Crosslinking Agents on the Properties of Dextran-Based Hydrogels for Targeted Antitumor Drug Delivery to the Colon. Gels 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erceg, T.; Vukić, N. Architecture of Hydrogels. In Fundamentals to Advanced Energy Applications; Kumar, A., Gupta, R., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erceg, T.; Brakus, G.; Stupar, A.; et al. Synthesis and Characterization of Chitosan–Acrylic Acid-Based Hydrogels and Investigation of the Properties of a Bilayered Design with Incorporated Alginate Beads. J. Polym. Environ. 2022, 30, 3737–3760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, W.; Gebert, B.; Altinpinar, S.; Mayer-Gall, T.; Ulbricht, M.; Gutmann, J.S.; Graf, K. On the Potential of Using Dual-Function Hydrogels for Brackish Water Desalination. Polymers 2018, 10, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISO 10993-5:2009; Biological Evaluation of Medical Devices—Part 5: Tests for In Vitro Cytotoxicity. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- Ghegoiu, L.; Predoi, D.; Iconaru, S.L.; Ciobanu, S.C.; Trusca, R.; Motelica-Heino, M.; Badea, M.L.; Stefanescu, T.F. Development of dextran-coated zinc oxide nanoparticles with antimicrobial properties. J. Compos. Biodegrad. Polym. 2024, 12, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostić, A.Ž.; Milinčić, D.D.; Stanisavljević, N.S.; Gašić, U.M.; Lević, S.; Kojić, M.O.; Tešić, Ž.Lj.; Nedović, V.; Barać, M.B.; Pešić, M.B. Polyphenol Bioaccessibility and Antioxidant Properties of In Vitro Digested Spray-Dried Thermally-Treated Skimmed Goat Milk Enriched with Pollen. Food Chem. 2021, 351, 129310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodkorb, A.; Egger, L.; Alminger, M.; Alvito, P.; Assunção, R.; Ballance, S.; Bohn, T.; Bourlieu-Lacanal, C.; Boutrou, R.; Carrière, F.; et al. INFOGEST Static In Vitro Simulation of Gastrointestinal Food Digestion. Nat. Protoc. 2019, 14, 991–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khajehsharifi, H.; Soleimanzadegan, S. Partial Least Squares Method for Simultaneous Spectrophotometric Determination of Uracil and 5-Fluorouracil in Spiked Biological Samples. Appl. Chem. Today 2013, 7, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šuput, D.; Pezo, L.; Rakita, S.; Spasevski, N.; Tomičić, R.; Hormiš, N.; Popović, S. Camelina sativa Oilseed Cake as a Potential Source of Biopolymer Films: A Chemometric Approach to Synthesis, Characterization, and Optimization. Coatings 2024, 14, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Hydrogels | K1, pH 7.4, 37 °C | R2 |

| S5 | 0.97 | 0.99 |

| S7.5 | 1.24 | 0.98 |

| S10 | 1.55 | 0.97 |

| Hydrogels | GF (%) |

| S5 | 84.75a ± 1.12 |

| S7.5 | 91.34b ± 1.42 |

| S10 | 94.90c ± 0.60 |

| Uracil–loaded hydrogels | Encapsulation efficiency (%) |

| S5 | 86.13 ± 0.88a |

| S7.5 | 89.67 ± 1.15b |

| S10 | 92.45 ± 1.12c |

| Uracil–loaded hydrogels | Gastric phase release, µg/ml | Intestinal phase release, µg/ml | Gastric phase release, % | Intestinal phase release, % | Total released amount of drug, % |

| S5, U | 6.17 ± 0.22a | 91.82 ± 3.78a | 4.93 ± 0.21a | 78.79 ± 2.97a | 83.73a ± 3.02a |

| S7.5, U | 4.50 ± 0.19b | 65.91 ± 2.63b | 3.60 ± 0.15b | 52.73 ± 2.11b | 56.33 ± 2.62b |

| S10, U | 0.00c | 57.24c ± 2.86c | 0.00c | 45.79 ± 2.29c | 45.79 ± 2.29c |

| Inhibition zone (mm) | ||

| Sample number: | Escherichia coli ATCC 8739 | Staphylococcus epidermidis ATCC 12228 |

| Ampicilin 10 mcg | 10 | 15 |

| S5 | - | - |

| S7.5 | - | - |

| S10 | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).