Submitted:

22 December 2025

Posted:

23 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

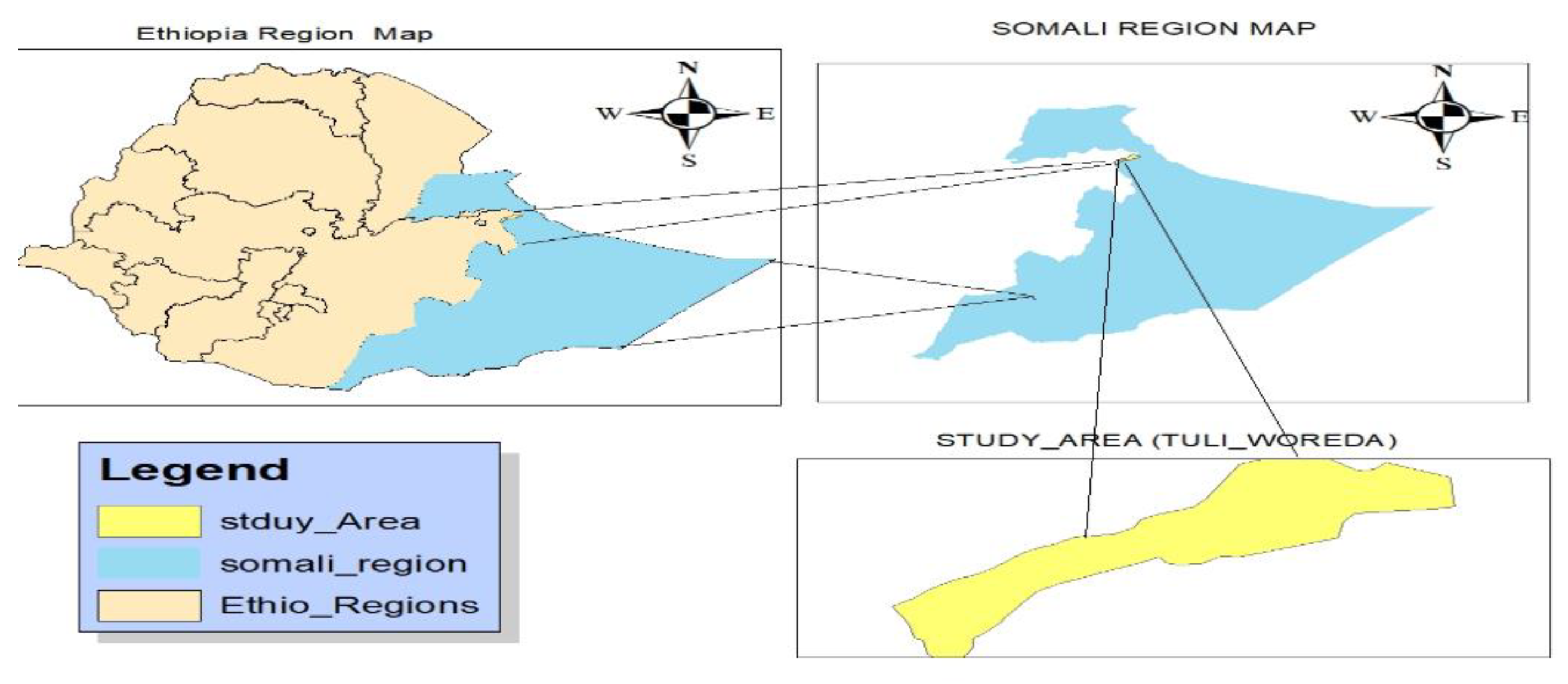

2.1. Description of the Study Area

2.2. Sampling Procedure and Sample Size

| Kebele Name | Total Household Heads (HHs) | Sample Proportion | Total Sample | Percent % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sarir | =300 | 109 | 42.75% | |

| Koralay | =200 | 73 | 28.63% | |

| Kulula | =200 | 73 | 28.63% | |

| Totals | 255 | 100.0 |

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Consideration

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Demographic and Socio-Economic Characteristics of Household Head

3.1.1. Gender and Age of SAMPLE Household Head

3.1.2. Marital Status of Sample Respondents

3.1.3. Education Status of Respondents

3.1.4. Family Size

| Variables | Categories’ | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 153 | 60.0% |

| Female | 102 | 40.0% | |

| Total | 255 | 100.0% | |

| Age | under 18 years | 25 | 9.8% |

| 20-30 years | 26 | 10.2% | |

| 31-49 years | 116 | 45.5% | |

| >50% years | 88 | 34.5% | |

| Total | 255 | 100.0% | |

| Marital status | Single | 42 | 16.1% |

| Married | 189 | 74.1% | |

| Divorced | 18 | 7.1% | |

| Widowed | 6 | 2.4% | |

| Total | 255 | 100.0% | |

| Education status | Illiterate | 210 | 82.4% |

| Literate | 35 | 13.7% | |

| Primary | 10 | 3.9% | |

| Total | 255 | 100.0% | |

| Family size | No children | 21 | 8.2% |

| <3childern | 20 | 7.8% | |

| 3-5 | 76 | 29.8% | |

| 6-8 | 92 | 36.1% | |

| >8 | 48 | 18.1% | |

| Total | 255 | 100.0 |

3.1.5. The Respondents’ Farming Experience

3.1.6. Farm Size of the Sample Respondents

3.1.7. Respondents of Climate Change Affected the Way of Life

3.1.8. Perceived Impact of Climate Change on Households’ Income

3.1.9. Respondents of Farmers Household Migrating Due to Climate Related Impact on Farming

| Variables | Indicator | Frequency | Present |

|---|---|---|---|

| How many years of experience do you have in crop production? | 10-20 years | 42 | 16.5% |

| 21-30 years | 124 | 49.0% | |

| more than 31 years | 88 | 34.5% | |

| Total | 255 | 100.0% | |

| Farm size | less than 1 hectare | 54 | 21.2% |

| 1-5 hectare | 147 | 57.6% | |

| 6-10 hectare | 51 | 20.0% | |

| More than 10 hectares | 3 | 1.2% | |

| Total | 255 | 100.0% | |

| Total | 255 | 100.0% | |

| How has climate change affected your way of life? | No change | 31 | 12.2% |

| slightly worsened | 71 | 27.8% | |

| Significance worsened | 153 | 60.0% | |

| Total | 255 | 100.0% | |

| is there any one in your household considered migrating due to climate related impact on farming? |

Yes | 222 | 87.1% |

| No | 33 | 12.9% | |

| Total | 255 | 100.0 | |

| Have there been changes in your household income due to climate impact on crop production? |

No change | 70 | 27.5% |

| Slightly decreased | 14 | 5.5% | |

| Significantly decreased | 171 | 67.0% | |

| Total | 255 | 100.0% |

3.1.10. Cultivated Crops by Respondent

| Variables | Indicators | Frequency | Present |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crop type | Maize | 49 | 19.2% |

| Sorghum | 76 | 29.8% | |

| Wheat | 130 | 51.0% | |

| Total | 255 | 100% | |

| what type agriculture activities you depend on | Irrigation | 39 | 15.3% |

| Rain fed | 216 | 84.7% | |

| Total | 255 | 100% |

3.1.11. Frames Perception of Impact Climate Change on Crop Production

3.1.12. The Causes of Climate Change

3.1.13. Respondent Awareness of Climate Change and Its Impact on Crop Production

3.1.14. Respondents’ Perception of Local Climate Trends over the Past 30 Years

3.1.15. Respondents’ Perception About the Frequency of Extreme Weather Events

3.1.16. The Effect of Climate Change Crop Production

| Variable | Indicator | Frequency | Present |

|---|---|---|---|

| What are the causes of climate change? | Human action | 80 | 31.4% |

| Natural process | 54 | 21.2% | |

| the act of God | 105 | 41.2% | |

| Both God and natural | 16 | 6.3% | |

| Total | 255 | 100.0% | |

| How aware are you of climate change and its potential impacts on agriculture? |

very aware | 206 | 84.8% |

| some aware | 26 | 10.2% | |

| Not very aware | 23 | 9% | |

| Total | 255 | 100.0% | |

| Total | 255 | 100.0% | |

| How frequently have extreme weather events drought occurred in your area |

more frequent | 195 | 76.5% |

| less frequent | 23 | 9.0% | |

| No changes | 37 | 14.5% | |

| Total | 255 | 100.0% | |

| Which climate factors have effected crop production? |

temperature increases | 38 | 14.9% |

| Changin precipitation Pattern |

111 | 43.5% | |

| increases frequency of extreme weather events |

16 | 6.3% | |

| changes in growing seasons |

90 | 35.3% | |

| Total | 255 | 100.0% |

3.1.17. Likert Scale Result of Climate Change Impact of Crop Production Farmers

| No | Statement | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | the changes in weather pattern have negatively affected crop yields |

1.2% | 1.2% | 16.1% | 18.4% | 63.1% |

| 2 | Decrease of Rainfall would impact the crop growth. | 4% | 18.4% | 18.0% | 4% | 55.6% |

| 3 | Crop diseases and pest infection increases and become problem than earlier |

1.2% | 1.3 | 15.0% | 19.0% | 63.5% |

| 4 | change in temperature and precipitation pattern have affected the growth cycles of crops |

1.6% | 0% | 12.5% | 21.6% | 64.3% |

| 5 | the community is migrating to cities due to inability of agriculture | 1% | 8% | 12% | 17% | 62.0% |

3.2. Climate Change Adaptation Strategies Adopted by Farmers

3.2.1. Respondent of Farmers Support Received to Adapt the Climate Change

3.2.2. Farmers Respondent for Challenges Implementing Adaptation Strategies

| Variable | Indicator | Frequency | Present |

|---|---|---|---|

| what strategies have you adopted to cope with the impact of climate change on your framing |

crop production diversified | 105 | 37.2% |

| using improved seed | 131 | 48.4% | |

| Irrigation | 2 | 8% | |

| soil conservation techniques | 5 | 2.0% | |

| Diversifying in come Source |

12 | 4.4% | |

| Total | 255 | 100.0% | |

| what support do you received to adapt the climate change? |

government support | 185 | 74% |

| NGO support | 43 | 16.% | |

| Agriculture extension | 26 | 10.% | |

| Total | 255 | 100.0% | |

| what challenges have you faced while implementing adaptation strategies? |

lack of knowledge | 180 | 71.0% |

| limited access to resource | 74 | 29.0% | |

| Total | 255 | 100.0% |

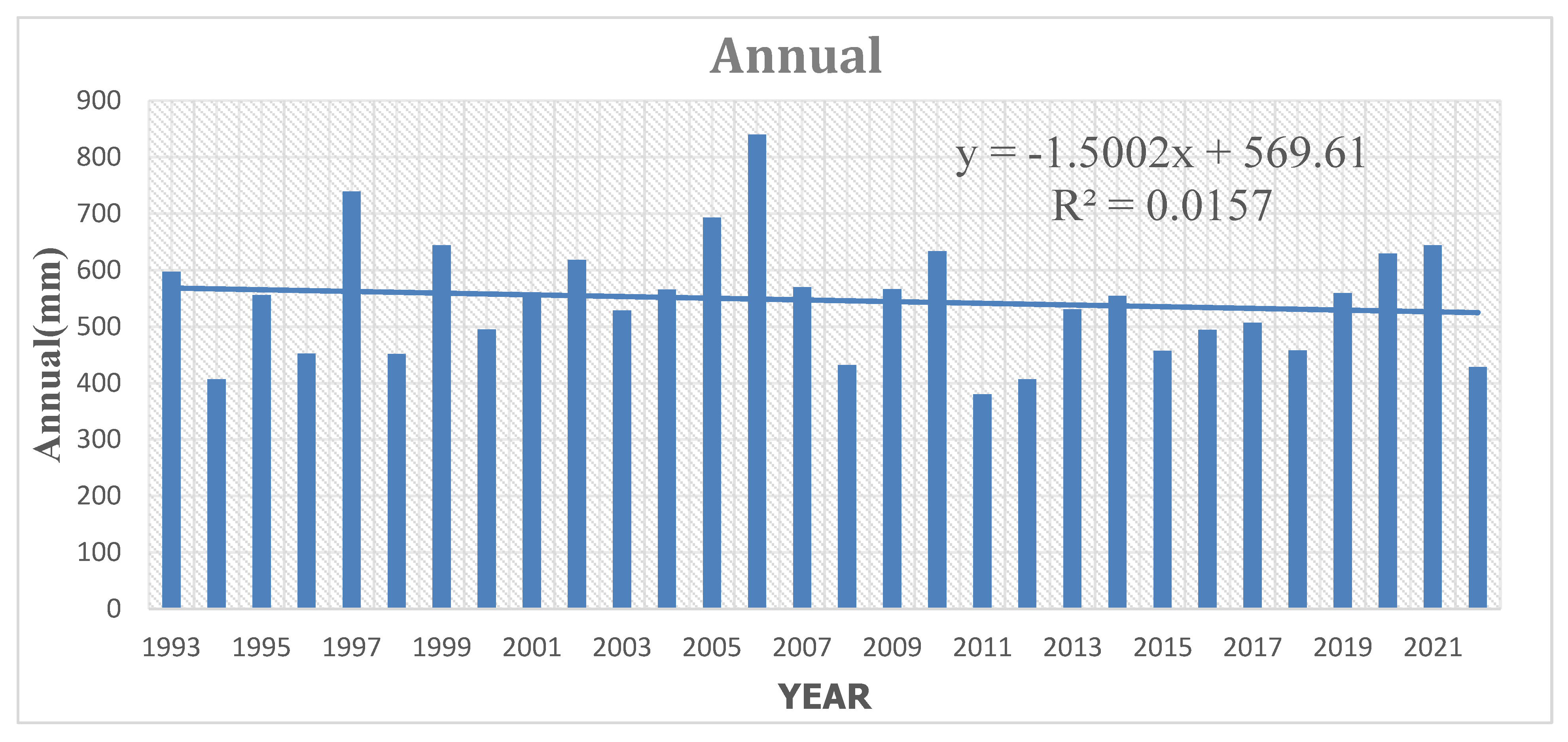

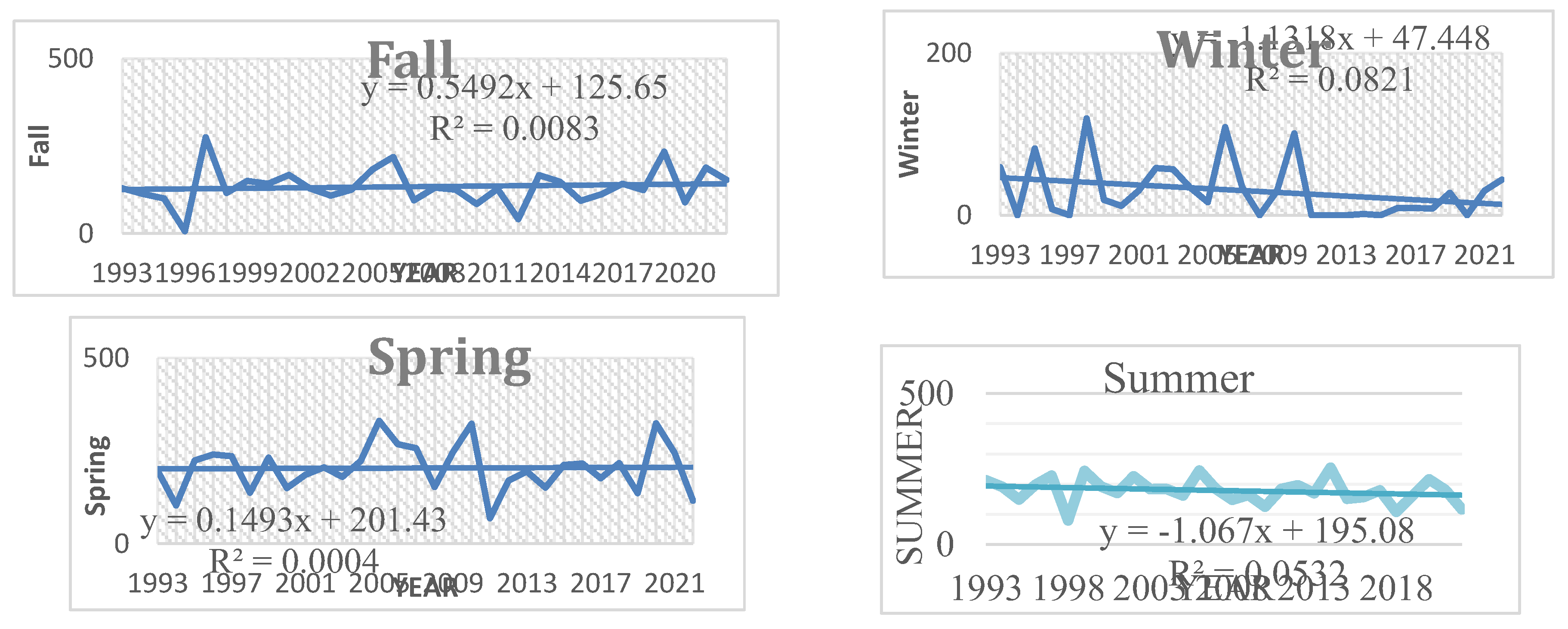

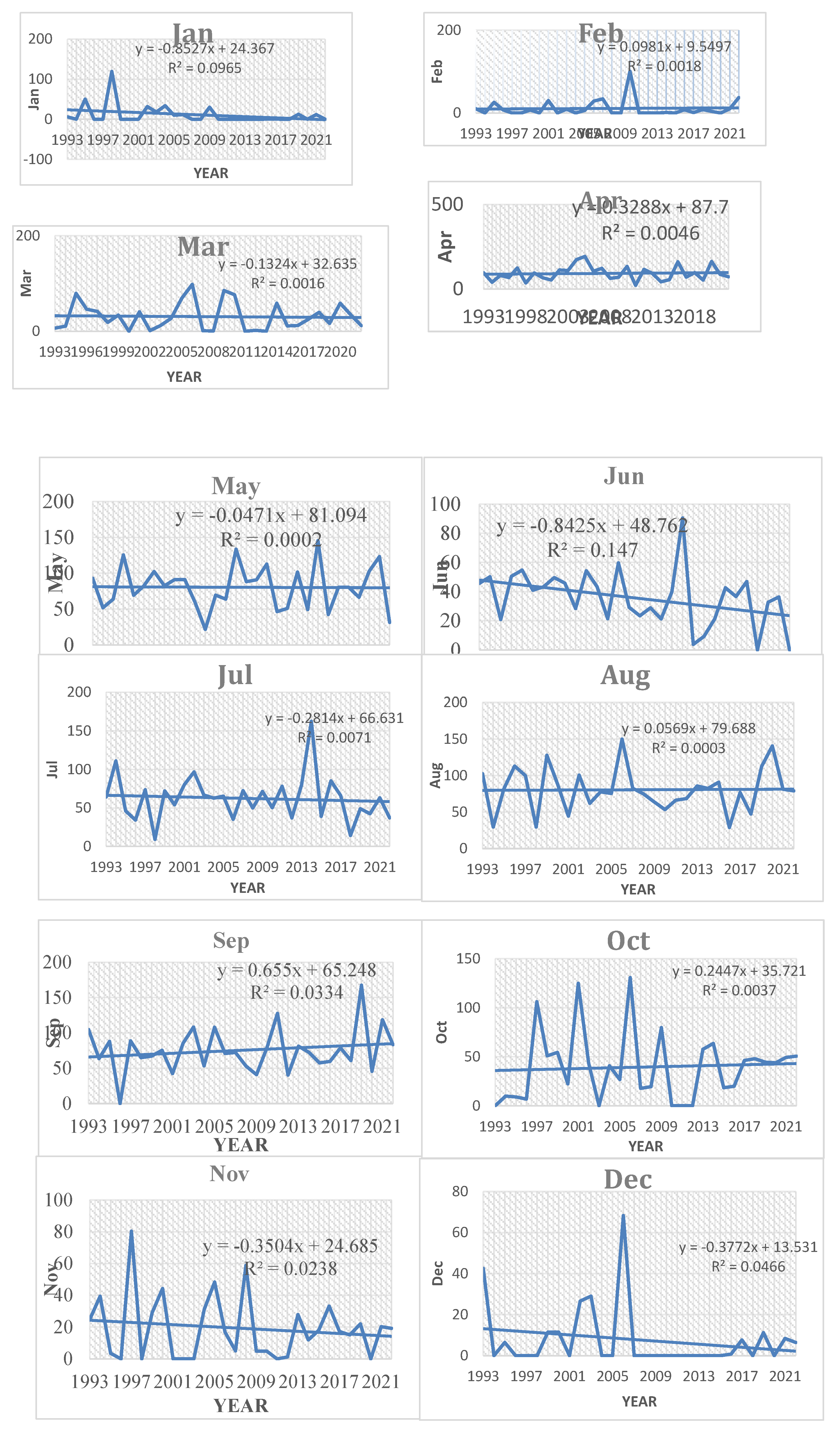

3.3. Rainfall and Temperature Trends of Tuliguled Woreda (1993-2022)

3.3.1. Mann-Kendall Monotomic Trend Analysis

3.3.2. Annual Rainfall Trend Analysis

3.3.3. Seasonal Rainfall Trend Analysis

3.3.4. Monthly Rainfall Trend Analysis

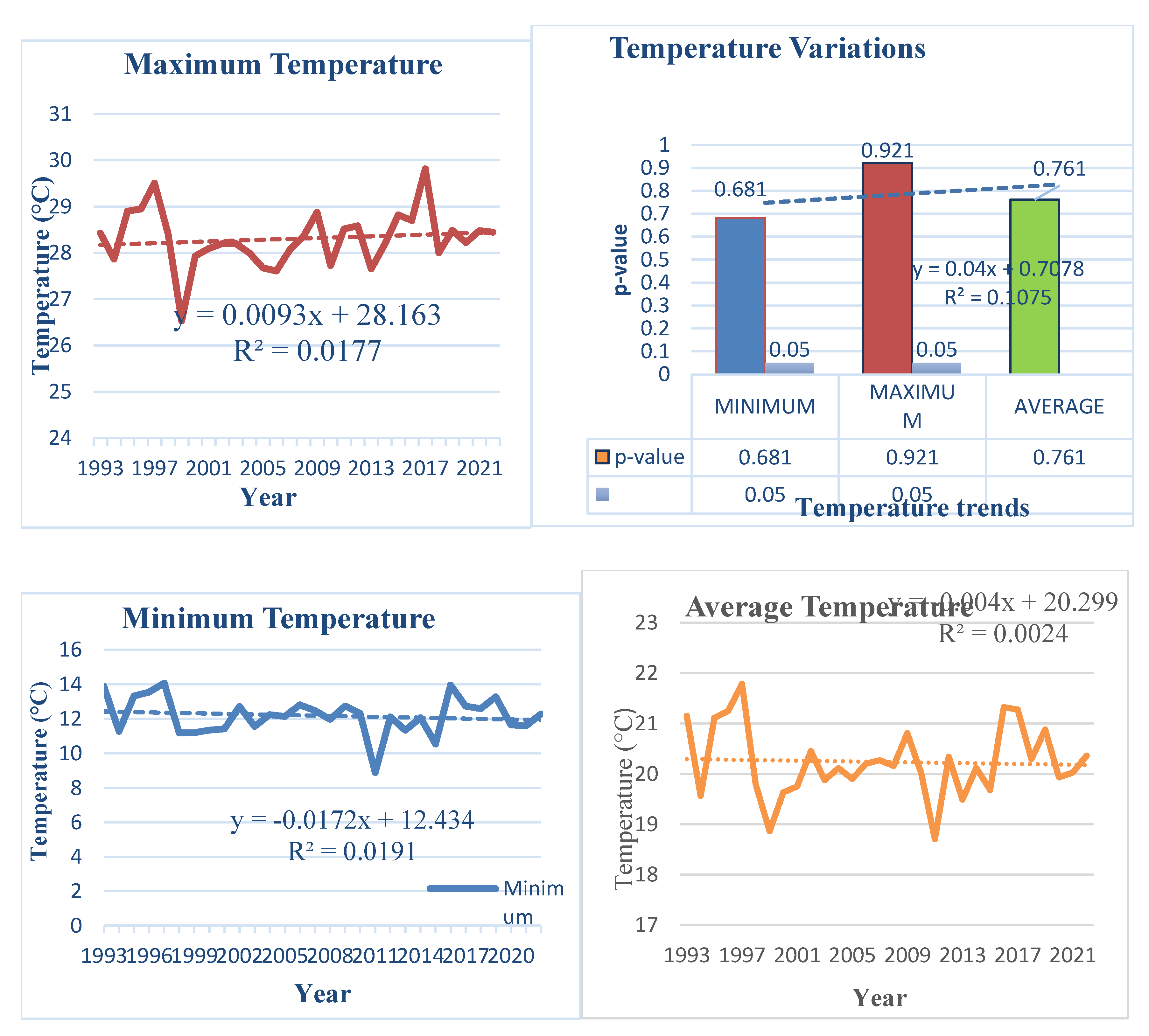

3.3.5. Temperature Trend Analysis

| Observation | Trend Direction and Magnitude | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Z-Statistic | Sen’s Slope | ||

| Monthly Rainfall Trend | Decreasing in Jan, Mar, May, Jun, Jul, Aug, Dec; Increasing in Feb, Apr, Sept, Oct, Nov | Varies | Varies increasing slope magnitude (Feb, Apr, Sep, Oct and Nov) decrease slope magnitude (Jan, Mar, May, Jun, Jul, Aug and Dec) |

| Seasonal Rainfall Trend | Winter (Dec-Feb): moderate decrease; Spring (Mar-May): low Decline; Summer (Jun-Aug): Steep decline; Fall (Sep-Nov): Slight increase | Negative/ Positive | Winter: -0.407 mm/year Spring: -0.038 mm/year Summer: -1.371mm/year Fall: +0.50 mm/year |

| Annual Rainfall Trend | Decreasing significantly | -1.371 | -0.407 mm/year |

| Temperature Trend | increasing sharply | Positive | +0.5 °C per decade |

3.3.5. Descriptive Summery of Average Crop Yield of Last Two Years

| N | Range | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std. Deviation | Variance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average crop yield of last two years |

255 | 101.0 | 19.0 | 120.0 | 52.209 | 20.3813 | 415.396 |

| Valid N (listwise) | 255 |

3.3.6. Multiple Regression Model Output

3.3.7. Model Summery

| Model | R –Square | Adjust R- Square | Std. Error | Df1 | Df2 | F -Value | Sig |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.213 | 0.095 | 19.3867 | 33 | 221 | 1.810 | 0.007* |

| Model | Sum of Squares | Df | Mean Square | F | Sig |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression Residual Total |

22443.922 83066.679 105510.601 |

33 221 254 |

680.119 375.867 |

1.809 | 0.007* |

3.3.8. Multiple Linear Regression Model Output

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

4.1. Conclusions

4.2. Recommendations

- ⮚

- Since there is a significant impact of maximum temperature on crop yield, farmers should have explored heat-tolerant crop varieties or considered adjusting planting schedules to mitigate the adverse effects of high temperatures on crop production.

- ⮚

- Since rainfall precipitation directly affects crop growth and yield, farmers should implement water conservation techniques such as rainwater harvesting and irrigation systems to ensure adequate water supply for crops, especially during periods of erratic rainfall.

- ⮚

- Small-scale farmers should be supported with access to resources, training, and technology to optimize their land use efficiency and productivity, ensuring that farm size does not limit their ability to adapt to changing climatic conditions.

- ⮚

- Empowering farmers with the knowledge, resources, and support systems needed to adapt to changing climatic conditions is essential for ensuring sustainable crop production and food security in the face of evolving environmental pressures.

- ⮚

- Farmers of Tuliguled woreda should diversify agricultural activities by incorporating resilient crops or adopting mixed cropping systems, which can help buffer against the effects of climate change on specific crops, thereby enhancing overall crop yield stability.

- ⮚

- Further research and monitoring are essential to assess the long-term impacts of climate change on crop production in the woreda at large in the region and to evaluate the effectiveness of adaptation measures implemented.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abawa, M.; Aynalem, M.; Fentahun, G.; Scholar, G. Impacts of climate change on crop yield in Ethiopia1653. 2023, v1. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas, S. Climate change and major crop production: evidence from Pakistan. In Fao 2020; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Abdisa, T.B.; Diga, G.M.; Tolessa, A.R. Impact of climate variability on rain-fed maize and sorghum yield among smallholder farmers Impact of climate variability on rain-fed maize and sorghum yield among smallholder farmers. Cogent Food and Agriculture 2022, 8(1). [Google Scholar]

- Abdullahi Musa, S. impacts of climate variability on maize (zea mays l.) yield and farmers’adaptation strategies in kurfa chele district of east hararghe zone, oromia, ethiopia; Haramaya university, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Abegaz, W.B. Temperature and Rainfall Trends in North Eastern Ethiopia. International Journal of Environmental Sciences and Natural Resources 2020, 25(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omer, A.A. Climate Change Effects on Subsistence Agriculture: Constraints and Opportunities for Adaptation in Tuli-Guled Woreda, Faafen Zone of Somali Region Ethiopia 2018, 1–104.

- Alotaibi, M. Climate change, its impact on crop production, challenges, and possible solutions. Notulae Botanicae Horti Agrobotanici Cluj-Napoca 2023, 51(1), 13020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, A.; Salamon, T.; Bogale, A. climate variability and adaptation strategies by small holder agropastoralists in boke district, west hararghe zone, oromia regional state, eastern ethiopia. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Debela, C.M.; Aweke, C.S.; Tefera, T.L. Farmers resilience to climate variability and perceptions towards adoption of climate smart agricultural practices: evidence from Kersa district, East Hararghe of Ethiopia. In Environment, Development and Sustainability; 2024; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- District, A.; Lalego, B.; Ayalew, T.; Kaske, D. Impact of climate variability and change on crop production and farmers ’ adaptation strategies in Lokka. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dhugomsa, J.A. impacts of climate variability on maize (Zea mays L.) yield and household adaptation strategies; the case of kersa district of east hararge zone, oromia regional state, ethiopia; Haramaya University, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Emran, S.A. Achieving food security and sustainability in a changing climate: assessing the performance of smallholder rice-based cropping systems in southern Bangladesh; University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Flaig, H. Effects of climate change on agriculture in Baden-Wurttemberg. WasserWirtschaft 2021, 111(6), 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuertes, M.Á.; Andrés, S.; Corrochano, D.; Delgado, L.; Herrero-Teijón, P.; Ballegeer, A.M.; Ferrari-Lagos, E.; Fernández, R.; Ruiz, C. Educación sobre el Cambio Climático: una propuesta de una herramienta basada en categorías para analizar la idoneidad de un currículum para alcanzar la competencia climática. Education in the Knowledge Society (EKS) 2020, 21(0), 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, G. Assessment of changes in climate extremes of temperature over Ethiopia Assessment of changes in climate extremes of temperature over Ethiopia. Cogent Engineering 2023, 10(1). [Google Scholar]

- Gemeda, D.O.; Korecha, D.; Garedew, W. Climate Change Perception and Vulnerability Assessment of the Farming Communities in the Wettest Parts of Ethiopia. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Males, G. Farmer ’ s response to climate change and variability in Ethiopia: A review Farmer ’ s response to climate change and variability in Ethiopia: A review. Cogent Food and Agriculture 2019, 5(1). [Google Scholar]

- Fano, D.G. Climate Change Risk Management and Coping Strategies for Sustainable Camel Production in the Case of Somali Region, Ethiopia. 2020, 4, 66–75. [Google Scholar]

- Haokip, S.W.; Shankar, K.; Lalrinngheta, J. Climate change and its impact on fruit crops. 2020, 9(1), 435–438. [Google Scholar]

- Hussein, M.A.; Antille, D.L.; Kodur, S.; Chen, G.; Tullberg, J.N. Controlled traffic farming effects on productivity of grain sorghum, rainfall and fertiliser nitrogen use efficiency. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research 2021, 3, 100111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassaye, A.Y.; Shao, G.; Wang, X.; Shifaw, E.; Wu, S. Impact of climate change on the staple food crops yield in Ethiopia: implications for food security. Theoretical and Applied Climatology 2021, 145(1–2), 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketema, A.M.; Negeso, K.D. Effect of climate change on agricultural output in Ethiopia. 2020, 8(3), 195–208. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, T.; Anderegg, W.R. Global warming and urban population growth in already warm regions drive a vast increase in heat exposure in the 21st century. Sustain. Cities Soc 2021a, 73, 103098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, T.; Anderegg, W.R.L. A vast increase in heat exposure in the 21st century is driven by global warming and urban population growth. Sustainable Cities and Society 2021b, 73, 103098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, J.; Daccache, A.; Hess, T.; Haro, D. Meta-analysis of climate impacts and uncertainty on crop yields in Europe. Environmental Research Letters 2016, 11(11), 113004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makuvaro, V.; Walker, S.; Phillip, T.; Dimes, J. Smallholder farmer perceived e ff ects of climate change on agricultural productivity and adaptation strategies. Journal of Arid Environments 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhi, G.S.; Kaur, M.; Kaushik, P. Impact of Climate Change on Agriculture and Its Mitigation Strategies: A Review 2021, 1–21.

- Mandel, I.; Lipovetsky, S. Available at SSRN 3913788; Climate Change Report IPCC 2021–A Chimera of Science and Politics. 2021.

- Bewuketu minwuye, B. farmers’ perception and adaptation strategies to climate change: the case of woreillu district of amhara region, northeastern ethiopia. Thesis, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ochieng, J.; Kirimi, L.; Mathenge, M.; Ochieng, J.; Kirimi, L.; Mathenge, M. Effects of climate variability and change on agricultural production: The case of small scale farmers in Kenya The case of small scale farmers in Kenya. NJAS - Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences 2021, 77, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoronkwo, D.J.; Ozioko, R.I.; Ugwoke, R.U.; Nwagbo, U.V.; Nwobodo, C.; Ugwu, C.H.; Okoro, G.G.; Mbah, E.C. Climate smart agriculture? Adaptation strategies of traditional agriculture to climate change in sub-Saharan Africa. Frontiers in Climate 2024, 6, 1272320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, J.; Tek, A.; Ritika, B.S. Climate change and agriculture in South Asia: adaptation options in smallholder production systems. In Environment, Development and Sustainability; Springer Netherlands, 2020; Vol. 22, Issue 6. [Google Scholar]

- Praveen, B. A review of literature on climate change and its impacts on agriculture productivity; 2019; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Priya, P.D. The Impact of Climate Change on Global Agriculture: Challenges and Adaptation Strategies. Siddhanta’s International Journal of Current Issues 2025, 1(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S.N. Climate Change and Agriculture in Ethiopia: A Case Study of Mettu Woreda. 2019, 3(3), 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinore, T.; Wang, F. Heliyon Impact of climate change on agriculture and adaptation strategies in Ethiopia: A meta-analysis. Heliyon 2024a, 10(4), e26103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinore, T.; Wang, F. Impact of climate change on agriculture and adaptation strategies in Ethiopia: A meta-analysis. Heliyon 2024b, 10(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambol1, T.; Derbile, E.K.; Soulé, M. Use of Climate Smart Agricultural Technologies in dry-season peri-urban agriculture in West Africa Sahel: A case study from Saga, Niger 2024, 1–24.

- Teshome, H.; Tesfaye, K.; Dechassa, N.; Tana, T.; Huber, M. Smallholder farmers’ perceptions of climate change and adaptation practices for maize production in eastern Ethiopia. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2021, 13(17), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halen tessema, I. Smallholder Farmers ’ perception and adaptation to climate variability and change in Fincha sub-basin of the Upper Blue Nile River Basin of Ethiopia. GeoJournal 2021, 86(4), 1767–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeratsion, B.T.; Manaye, A.; Gufi, Y.; Tesfaye, M.; Werku, A.; Anjulo, A. Agroforestry practices for climate change adaptation and livelihood resilience in drylands of Ethiopia. Forest Science and Technology 2024, 20(1), 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zigale, T.T. climate change, pastoral livelihood vulnerability and adaptation strategies: a case study of sitti zone, somali regional state in eastern ethiopia university of south africa supervisor: dr. busani mpofu December 2021; December, 2021; pp. 1–290. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.