1. Introduction

The unabating effects of global climate change on agriculture production require a continuous search into sustainable ways to stem the tide, and birth a food-secured planet, free from hunger. Agriculture contributed about 4.3% to the global GDP and employed about 866 million (27% of the population) of the world’s workforce in 2021 [

1]. In most developing countries where Guinea-Savannah regions are predominant, the agriculture sector has remained the lifeblood of rural communities, providing income and sustaining livelihood. Rural dwellers are home to over half of the world’s poor, and these communities, are largely in the developing world, and most earn their living from farming. Here, the livelihoods of millions anchor on the successful cultivation of staple crops, particularly maize and sorghum. Enhancing agricultural productivity is thus essential to achieving poverty reduction.

A semi-arid climate characterizes the Guinea-Savannah region, which is predominantly rain-fed agriculture. As a critical agricultural zone in Sub-Saharan Africa, it is vulnerable to changing climatic variability patterns, hugely impacting staple crops such as maize and sorghum. As the climate continues to change, understanding the effects of climate thresholds on producing these essential cereals is crucial for devising adaptive strategies that ensure food security in this region. This is particularly crucial in Nigeria, where the Guinea-Savannah region is pivotal in the nation's food production. As major staples of a larger population within the guinea-savannah belt, sustained production of maize and sorghum is threatened by weather vagaries, including temperature extremes, erratic rainfall, and prolonged drought. As climate scientists project an increase in the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events, it becomes imperative to investigate the specific climatic thresholds that may trigger adverse effects on the growth and yield of maize and sorghum.

Climate change poses significant challenges to global agricultural systems, affecting crop yields, food security, and the livelihoods of millions of people. Despite the integration of precision agriculture [

2] by many developed countries in mitigating the global climate challenge, the developing world still gropes under the biting effects of climate change. Rising temperatures, variations in precipitation patterns, and extreme weather events are becoming more frequent, posing significant challenges to crop productivity worldwide. Among the regions most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change is the Guinea-Savannah, a crucial agricultural zone in Sub-Saharan Africa. More important is that this challenge has further revealed the fragility of the agriculture sector, its inherent production risks occasioned by climate variability and other natural disasters which have led to low agricultural yields, and the lack of commensurate mitigants characteristic of it [

3,

4,

5]. In this context, maize and sorghum, fundamental to global food security, are under increasing scrutiny for their vulnerability to climate variability.

Several studies have underscored the implications of climate change on staple crops. In the global space, for instance, the work of [

6] provides a comprehensive assessment of how changing climate conditions affect major cereal crops and emphasise the need for region-specific studies to capture the nuances of diverse agroecosystems. Also, [

7] in their study demonstrated a correlation between rising temperatures and decreased maize yields. Similarly, the works of [

8] underscored the sensitivity of sorghum to shifts in precipitation patterns, indicating potential implications for food security. At the national level, [

4] reviewed various works of literature and opined that climate change including unpredictable weather, and rainfall variability patterns, adversely impacts crop productivity. [

9] considered climate effect on crop production at a localised level and avowed that maize production correlated highly with rainfall and that rainfall, maximum and minimum temperature affect the yield of maize and sorghum in Kwara State, Nigeria. In a similar study, [

10] asserted that the climate suitability level for maize, yam, and cassava will drastically reduce with time. More still, [

11] equally recorded a significant decline in maize yield occasioned by climate variability. The 2022 National Bureau of Statistics report highlighted the notable contribution of the agricultural workforce to Nigeria's Gross Domestic Product (GDP). It emphasised the need for climate threshold research on maize and sorghum, and evidence-based policy for sustainable agricultural practices.

This study investigated climate thresholds affecting maize and sorghum productivity in the Guinea-Savannah region, by establishing maize and sorghum tolerance levels to harmful climate extremes. This research contributes to the body of knowledge already in existence enhancing understanding of their resilience to climate variability. Specifically, this study investigates the effects of climate change on the productivity of maize and sorghum in Guinea-Savannah Nigeria. It also assesses the specific climate thresholds (temperature and precipitation) that significantly impact the growth and yields of maize and sorghum. It further examines the drivers of yield variances in maize and sorghum, while identifying potential adaptive mechanisms, including climate-resilient agriculture practices that mitigate the effects of extreme climatic conditions on crop yields. Therefore, this study seeks to find critical temperature and precipitation thresholds that may act as early warning signs of decreased crop yield using a combination of field surveys, climate data, and statistical studies. While there is a wealth of literature on the impact of climate change on agriculture, these studies overlook the distinct responses of crops like maize and sorghum to climatic factors. There is a notably limited understanding of the specific climate thresholds that trigger adverse effects on maize and sorghum production, thus, the lack of precision in identifying climate thresholds for selected crops. Besides, region-specific studies that capture the intricacies of diverse agroecosystems, particularly in the context of the world’s guinea-savannah regions, barely exist. Furthermore, the need for empirical data sufficiently linking climate variables and socioeconomic directly to crop yields, especially in developing and underdeveloped worlds, spurred this study. This study therefore contributes to global efforts to create resilient agricultural techniques to climate change and lessen its effects on food systems, making it pertinent and topical. Specifically, it identifies critical temperature and precipitation thresholds that serve as early warning signs for decreased crop yields, enhancing understanding of climate impacts on agriculture. By focusing on maize and sorghum, this research underscores the vulnerability of these staples to climate variability, reinforcing their importance in global food security discussions.

This study reinforces existing literature and aligns with global concerns about climate change impacting agricultural production in the following ways. Firstly, it highlights rainfall and temperature as critical components affecting the patterns of crop yields globally. The research revalidates the notion that severe climate variability is a major threat to food security. Secondly, this research examines the specific climatic factors influencing maize and sorghum yields. Thirdly, this study lays the groundwork for developing targeted strategies by modeling optimal performance thresholds for maize and sorghum in the guinea-savannah region of Nigeria. It also recommends investments in climate-resilient agricultural practices, including weather-based insurance schemes to mitigate the adverse effects of a changing climate.

2. Materials and Methods

This section of the study provides information on the data collection methods, the data analytical methods, and model specifications, including the Just-Pope production model, which assessed production risks, and Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) co-integration model, which analysed the long-run relationships between crop yield and climate factors. ADF tests were used to ensure stationarity and optimal lag selection following the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). A flowchart detailing the methodology is available in

Figure 1.

2.1. Sources of Data

Both primary and secondary data were utilised in this research work. Primary data were collected through a semi-structured questionnaire. The questionnaire solicited information about the respondents’ socioeconomic attributes, crop production factors, awareness of climatic change, and the intended or autonomous strategy for addressing climate change problems. Secondary data about maize and sorghum yield, temperature, rainfall, area cultivated, and relative humidity were sourced from the Nigerian Meteorological Agency (NIMET), National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), Agricultural Development Programme (ADP) of Niger State, and ADP of Kwara State.

2.2. Sampling Procedure and Sample Size

A four-stage sampling was followed to come up with the respondents. The initial stage entailed the random picking of two states within the Guinea Savannah area, specifically Niger and Kwara. Subsequently, the second stage comprised the purposive selection of five Local Government Areas (LGAs) apiece from the aforementioned states notable for the growing of arable crops, specifically maize and sorghum. The selected LGAs are Offa, Irepodun, Ifelodun, Baruten, and Patigi, LGAs of Kwara State. Mokwa, Lapai South, Borgu, Gbako and Kontangora LGAs of Niger State were chosen.

In the third stage, four communities were chosen at random from each previously chosen LGAs, resulting in a total of 40 communities. Farmers’ lists in these States who grow maize and sorghum, were obtained from the ADP office. In the fourth stage, four sorghum and maize producers were chosen at random out of each of the communities, using the obtained lists culminating in 320 respondents. Additionally, time-series weather data spanning from 1971-2022 were sourced from multiple reports of ADP, NIMET, and NBS.

2.3. Data Analytical Techniques

2.3.1. Just-Pope Production Model

The Just and Pope (J-P) production function assesses the risk associated with production functions by relaxing certain restrictions on production variance [

12]. This model operates based on the production function error variance estimation and can be linked to one or entire explanatory variables, characterising it as a heteroskedasticity multiplicative model [

13,

14].

Following [

15], production functions will be estimated in this form:

Here, Y represents maize and sorghum yields, f (≅) denotes production function mean, and X consists of a group of explanatory variables like climate, time duration, and location. The parameter estimates of f (≅) explain how independent variables impact average yield, while h(≅) captures each independent variable effect on yield variance. The functional form h(≅) for the error term ui, explicitly accounts for heteroskedasticity, permitting variance effects estimation. The parameter signs of h(≅) are uncomplicated: any independent variable’s positive marginal effect on output variance signifies an increase in the output standard deviation, while a negative sign depicts a reduction in output variance due to increased variance.

We specify the fundamental model as:

Where

yit is the crop yield in the region

i at the time

t;

xkit is the input quantity of factor

k in the region

i at the time

t, and

αj,

j = 0,1……

k, are the parameters for evaluation

xmit signifies a factor that influences the degree of risk and

βm serves as the associated coefficient, while

ε represents the stochastic disturbance term following a standard normal distribution. Consequently, the variance and the expected (or mean value) output are derived through distinct functions, algebraically denoted as:

Within this framework, if production risk manifests as heteroskedasticity in the production function, the second term in equation (2) represents an error term exhibiting heteroscedastic for estimation purposes.

The model was evaluated for each crop, with coefficient estimates reflecting output elasticities relative to input factors, given the log-linear specification. Production risks as it concerns heteroskedasticity error structure, are typically present in various aspects of farming output [

15].

The model explanatory variables are:

(X1) = Rainfall amount (mm)

(X1)2 = Square of rainfall amount,

(X2) = Temperature (0C)

(X2)2 = Temperature squared,

(X3) = Relative humidity (%)

(X3)2 = Relative humidity squared.

(X4) = Location

(X5) = Time period

2.3.2. Co-Integration Model: A Bounds Approach

To ensure an empirical analysis of the dynamic relationship among key variables, including maize and sorghum production, yearly temperature, relative humidity, rainfall, and long-run relationships., the study employed the bounds testing (ARDL) co-integration approach.

While this approach bypasses unit root test, it is crucial to perform a stationarity test to ensure ARDL assumptions are not violated, particularly as regressors are integrated of

I(1), I(0) or mutually). This assumption is essential because the model will fail in the presence of

I(2) series. Hence, Augmented Dickey Fuller (ADF) test was applied to determine the stationarity status of all the variables. The model is given as follows:

Where

Pit is variables examined for stationarity; Δ is the first difference operator;

n is the number of lags of the included variables;

α,

φ,

θ are estimated parameters;

is the error term.

The Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) unit root test evaluates series stationarity. The null hypothesis,

, posits that the series exhibits non-stationary in contrast to the alternative,

, which suggests stationarity. The null is rejected if the absolute value of the calculated ADF statistic exceeds that of the critical values, signifying stationarity. However, if the absolute ADF statistical value falls short of the critical values, the null hypothesis cannot be rejected, implying the time series remains non-stationary [

16,

17].

To test the hypothesis of no co-integration among the variables versus the existence of co-integration, an F-test was conducted to assess the joint significance of the coefficients of the lagged levels of the variables. The null hypothesis stating that there is no co-integration among the variables, implying the non-existence of a long-run relationship for crop production, rainfall, temperature, and relative humidity, is expressed as:

The alternate hypothesis, of long-run relationship or co-integration, was stated as:

The F-statistics, used to test for co-integration within the ARDL framework, exhibit a nonstandard distribution regardless of whether the variables are

1 or

1. [

18] proposed two sets of adjusted critical values, establishing the lower and upper bounds used for inference: one assuming all variables are

1 and the other assuming

1. The null hypothesis of no co-integration is rejected if the estimated F-statistics exceeds the upper bound critical value, accepted if it is below the lower bound, and inconclusive if it falls between the two bounds. Optimal lag length for ARDL model given was determined using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC).

The models employed in this study are outlined as follows.

Following [

19,

20,

21] crop yields were linked to climate variables like rainfall and temperature.

Also, following the approach of [

22], the variables were converted into their natural logarithm (ln) to facilitate the interpretation of coefficients in the standardized percentage form. The unrestricted error correction model (UECM) as outlined by [

18] within the ARDL framework, is utilised to test co-integration among the variables under investigation as:

The conditional ARDL model evaluates the long-run relationship after establishing and specifying co-integration as follows:

An error correction model evaluated the short-run dynamic relationship thus:

Where:

CP = Annual Arable Crop Yield (kg/ha)

Temp = Temperature (degree Celsius)

Rain = Rainfall (mm)

Hum = Relative humidity (%)

β0 = Constant term

ln = Natural log

et = White noise

= Short-run elasticities (coefficients of the first-differenced explanatory variables)

= Long-run elasticities (coefficients of the independent variables)

Error correction term lagged for a period

Speed of adjustment

Δ = First difference operator

q = Lag length

3. Results

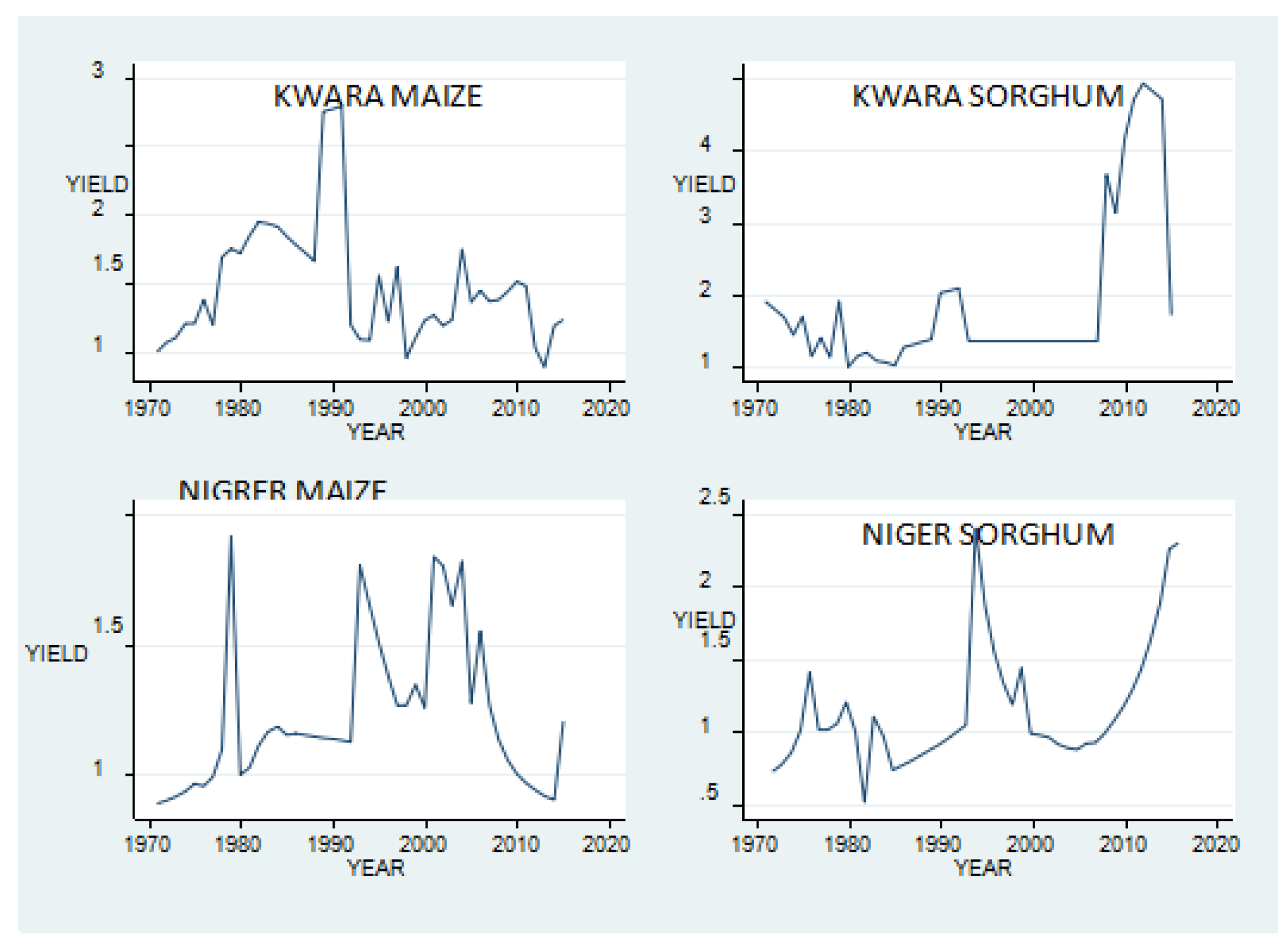

The pooled time-series cross-sectional data collected from 1971 to 2022 was used to estimate the effects of weather variables on maize and sorghum yield in two Nigerian states. The crop output data in each of the two States were obtained from the Federal Ministry of Agriculture and the Agricultural Development Programme. Day-to-day activity data on temperature and precipitation were collected from the Nigeria Meteorological Station (NIMET). The daily minimum and maximum outcome over the growing season for each crop is contained in the temperature data. The summary statistics of data are reported in

Figure 1.

From

Figure 1, maize yield rose from 0.57 tons ha

-1 to a peak of 3.8 tons ha

-1, while sorghum yield increased from 0.6 to 2.4 tons ha

-1. The rises in yield could be credited to combined incentives via improved technology and Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs). However, the yield growth has yet to meet the expectations of policymakers and researchers. Although these figures outperform and almost double the 2 tons ha

-1 maize and more than doubles the 1 ton ha

-1 sorghum statistics for sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), it however remains significantly lower when compared to global standards, particularly with countries with advanced agricultural technologies and practices such as United States maize yields, which exceeds 10 tons ha

-1 [

23]. Nigeria’s maize yield is <2 tons ha

-1 relative to 4.9 tons ha

-1 and 4.2 tons ha

-1 in South Africa and Ethiopia respectively [

24]. This report attributes relatively low yields to drought, irregular rainfall, insect pests, and diseases, and declining soil fertility. The rise might be due to the government’s interest in encouraging value chain development via the Agricultural Transformation Agenda. Serious crop damage can occur if daily temperature surpasses a specific threshold at a specific developmental stage [

25].

The Quadratic equations in time variables were estimated to ascertain growth patterns in Maize and Sorghum yield. From

Table 1 and

Table 2, the negative significant coefficient of maize and sorghum at 1% probability level depicts a decrease in growth not as quickly as expected though. This could be a result of instability of government policies and poor implementation as well as inadequate monitoring of agricultural extension programs in the study area.

3.1. Estimates of the Sorghum Yield and Variance Response Functions

Table 3 shows positive and significant relationships between maize yield and farm size, maize seed, labour, and family labour, implying that any additional increase in any of these significant variables inputs resulted in increased maize yield.

The negative but significant relationship of fertilizer with maize implies that a unit increase in the fertilizer quantity resulted in a 0.003 decrease in maize yield. This could be due to overutilization of the input in the production processes. Also, the significant relationship of proportion of family labour used squared, farm size squared, and maize seed square with maize yield indicates that maize yield increases as any of these variables increases. However, at the higher quantities, maize yield would increase at a decreasing rate and later start reducing.

The negatively significant relationship between the variance of maize yield, farm size, and quantity of maize seed, labour, and fertilizer implies that an increase in any of these variables would result in a decrease in the variance of maize yield.

3.2. F-Test Results of the Hypothesis for Maize Yield with the Use of Climate Variables

As shown in

Table 4, the joint F-value of 8.36 indicates that the variance of maize yield was affected by temperature; thus, we fail to accept the hypothesis (b3=b4=0, i.e., Variance is not influenced by temperature).

The findings indicate that fluctuations in temperature can negatively impact maize yield variability. The hypotheses for rainfall and relative humidity were not rejected since they did not affect the variance of maize yield in the study area. The interplay between temperature and rainfall significantly impacts plant growth and development, leading to yield variability. Understanding these mechanisms is essential, therefore for developing adaptation strategies that mitigate the adverse climate change impacts on agriculture. It is important to say that temperature affects plant growth and development at various stages along germination, flowering, and maturation. Just as high temperatures can accelerate growth rates, it may also lead to heat stress, which negatively impacts yield. For instance, extreme temperatures can disrupt pollination and reduce grain filling, leading to lower yields. Studies have shown that as temperatures rise, the tendency of yield reduction increases, particularly for sensitive crops like sorghum and maize [

26]. Similarly, adequate and timely rainfall directly impacts soil moisture levels, essential for nutrient uptake, overall plant health, and optimal growth. Insufficient rain can lead to drought stress, which severely impairs crop productivity. Conversely, extreme rain can cause waterlogging, reduce oxygen availability in the soil, and root diseases, further limiting plant growth. [

27] reported adopting a machine learning approach to simulating farmers’ crops for drought-prone areas.

The result from

Table 5 connotes that an increase in fertilizer quantity, farm size, and labour increases sorghum yield in the study area. As well, family labour squared, and farm size squared significantly increase yield at a higher quantity but at a decreasing rate.

3.3. F-Test Results of the Hypothesis for Sorghum Yield with the Use of Climate Variables

The joint F-value (6.14) from the F-test reflects that the variance of sorghum was affected by temperature; thus, we fail to accept the hypothesis (b

3 = b

4 = 0, i.e., variance is not influenced by Temperature). This implies that temperature affected the variance of sorghum yield (

Table 6). The F-tests were not rejected for other climate variables since they did not influence the variance of sorghum yield in the area of study.

3.4. Estimates of the Variance Response Functions with Climate Variable

The inverse relationship of rainfall implies that as rainfall increases, the variance of maize yield will decrease, probably because of the cooling effect it has on the surface of the earth (see

Table 7). Conversely, the direct relationship of temperature squared suggests that as the Earth's surface is heated up, maize production risk increases.

Sequel to a marginal change in climate, this study measures the change in agricultural yield from a policy perspective. Based on the mean yield function, a significant annual loss in value for the crops studied will result from a 1oC increase in HDD. For crops that are not resistant to drought, a 10C increase in severe temperatures will result in little loss in production value per hectare.

The results of the Just and Pope stochastic production function obtained from

Table 8 reveal the Adjusted R-square of 0.64 for maize and 0.72 for sorghum.

Temperature, rainfall, and Harmful Degree Day (HDD) increase the yield risk for maize and sorghum, while the Growing Degree Day (GDD) reduces the risk in yield for maize and sorghum. By implication, if GDD increases by one unit, there is a corresponding increase in yield in these two states. The effect of an increase in severe temperature, estimated with HDD on maize and sorghum yield, is theoretically expected to be negative. This result reaffirms the hypothesis that severe weather is a major limitation of crop growth, especially in North Central, Nigeria. The technological advancements, including mobile technologies and biotechnology, in sorghum production in the states can account for the positive coefficient of time trend. However, a negative time trend is observed in maize production because of a positive correlation between cloud cover and increased rainfall, which contributes to less sun radiation. Such an event may lower photosynthesis and thus decrease output.

Table 8 describes the state-after-state regression results of variance in maize and sorghum yield as a result of the risk function due to variability in weather. Rainfall for maize was discovered to increase the risk in Kwara state. Maize is most affected in Niger state with a coefficient of 2.52. GDD was found to increase the yield risk of maize in Kwara and more severe in Niger states. HDD is seen to raise the yield risk in both Kwara and Niger States. A unit increase in HDD will raise the yield risk of both maize and sorghum in the two states.

The vector error regression result is represented in

Table 9 and

Table 10. The estimated coefficients of the impacts of climate variables on crop yields suggest a positive relationship between maize and sorghum yields and GDD in model 1. Just as a high temperature above 34°C was found to be hazardous to maize yields, it was insignificant for sorghum yields. Rainfall coefficients for the two crops indicated similar nonlinear effects over their growing seasons. To attain maximum outputs, maize requires a significantly higher rainfall (174 cm) than sorghum (94 cm) over the same growing season. The nonlinear relationship between precipitation and crop yields is an indication that rainfall increases crop yields, but at a decreasing rate.

The addition of temperature variables does not significantly change coefficient estimates of GDD, time, and rainfall relative to those in model (1). However, the coefficients of temperature are statistically significant at the 1% level, indicating that temperature affects maize and sorghum yields. High temperatures (over 34°C) negatively impact sorghum yields.

The inclusion of economic variables in model (2) suggests that the labour coefficient negatively impacted sorghum yield but had no significance on maize yield. This may be due to higher wages that led to decreased use of labour. Likewise, the fertilizer coefficients in both yield equations have expected signs but are not statistically significant. The result aligns with the observation of [

28,

29,

30,

31], that the inclusion of economic variables does not change the coefficient estimates for climate variables significantly.

Farmers can use adaptation mechanisms like the use of available cropland for irrigation and modification of farming practices to alleviate the external impacts of climate change amidst the negative effects of change in climate change on crop yields [

32,

33,

34]. As irrigation can have an effective impact on crop yields and irrigation requirements rely largely on local climate conditions, excluding this variable may have biased effects on crop yields from climate variables.

3.5. Unit Root Tests Analysis

Akaike Information Criteria (AIC) was employed to choose the suitable lag length, ranging from lag zero to lag four as dsiplayed in

Table 11. The results of ADF were obtained from a regression analysis that maximized the AIC. To check how these variables are integrated, the standard ADF unit root test was used. The ADF test statistic showed that just as Rainfall and Temperature were stationary at level

I(0), Maize and Sorghum yield were stationary at the first difference

I(1). Quite unlike the Johansen procedure, the combined

I(1) and

I(0) may be used under ARDL, thus justifying the use of the bounds test approach in this study.

The results did not provide enough evidence to reject the null hypothesis of non-stationarity for maize and sorghum; however, the hypothesis was rejected when applied to the differenced series, indicating that all series of maize and sorghum yield are integrated of order one - I(1). The unit root tests for maize and sorghum are found to be I(0) while those of climate variables are I(1). The null hypothesis (presence of unit root) was also rejected for daily mean temperature and rainfall.

Table 12.

Autoregressive Distribution Lag for Maize.

Table 12.

Autoregressive Distribution Lag for Maize.

| Variable |

Coefficient |

T-ratio |

Probability |

| Lnmaize |

0.629 |

5.220 |

0.000 |

| Lntemp |

0.748 |

-3.201 |

0.000 |

| Lnrain |

-0.491 |

2.603 |

0.033 |

| Lnhum |

0.032 |

0.773 |

0.438 |

| Lnmaxtemp |

0.814 |

3.101 |

0.000 |

| Lnmintemp |

0.626 |

0.383 |

0.852 |

| Lnmaxrain |

0.217 |

2.690 |

0.031 |

| Lnmixrain |

0.033 |

1.040 |

0.421 |

| Constant |

6.04 |

2.690 |

0.031 |

| R2= 0.8253 Adjusted R2= 0.8216 F-stat =641.4204 DW= 1.973 |

ARDL results for maize and sorghum yield in

Table 13 and

Table 14 reveal a significant influence of temperature and rainfall.

A 1% increase in temperature and rainfall results in a 0.63% decrease and a 1.5% increase in sorghum output, respectively. Unfriendly rainfall negatively affects maize yield due to erosion, flood, and leaching resulting in reduced maize yield. Temperature's positive impact on sorghum yield may be due to its importance in sorghum growth and high tolerance to weather stress. However, high-temperature thresholds can harm sorghum yield in the long run. The outcome of this study is in consonance with [

36] that an increase or decrease in the rainfall pattern leads to a rise or fall in output.

A 1% rise in temperature and rainfall leads to a 0.75% increase and a 0.49% reduction in maize output, respectively. The inverse relationship between precipitation and maize yield can be attributed to excess precipitation resulting in erosion and leaching, thus reducing access to soil nutrients and eventual decrease in maize yield. This is in line with [

21], who found a negative but significant long-term relationship between rainfall and agricultural output. The direct association between temperature and maize yield may be related to its usefulness in growing maize crops, but a high-temperature threshold can be detrimental to maize yield in the long run.

3.6. Co-Integration Test on the Basis of ARDL Bounds Test Approach

An analysis of Co-integration which focused on the ARDL Bounds Approach of OLS regression was evaluated and when added to the regression analysis, the combined significance of the parameters of the lagged level variables was tested (see

Table 14). The F-statistic tests the null hypothesis of no long-run co-integration, implying that the lagged level variables have no combined significance. Wald Test of coefficients in the ARDL-OLS regression was used to estimate the F-statistic. The result shows the value of the computed F-statistic for FMAIZE (MAIZ | TEMP, RAIN, RHUM) to be 7.41. The null hypothesis of no co-integration was rejected because the value is greater than the upper bound critical value of 5.49 at the 5% level.

This result suggests a long-run co-integration association between the variables when maize yield and sorghum yield were regressed separately against average temperature, relative humidity, and rainfall. This result is in tandem with the findings of [

37] using Johansen test of co-integration between temperature and rainfall variables and Nigeria’s crop productivity, a long-run association.

Table 15 presents results from a general-to-specific modeling approach to determine the maximum lag order for maize and sorghum yield.

OLS regression from the equation was measured and tested when added to the regression analysis, for the combined significance of parameters of the lagged level variables. The F-statistic tests the combined null hypothesis that the coefficients of the lagged level variables are zero which means there is no long-run relationship among the variables. The F-statistic was evaluated with the use of the Wald Test of coefficients in the ARDL-OLS regressions.

The null hypothesis for no co-integration was rejected for both crops, indicating a long-run co-integration association among the variables when maize and sorghum yield were regressed separately against explanatory variables of rainfall and average temperature. This is in line with the report of [

38] who opined a long-run relationship between temperature and rainfall variables and Nigeria’s crop productivity using the Johansen co-integration test.

In

Table 16, the ADF test statistic shows that at the initial difference

I(1), Maize and Sorghum yield were stationary, while at level

I(0), temperature, relative humidity, and rainfall were stationary.

Unlike the Johansen procedure, the combined

I(0) and

I(1) can be utilized under ARDL and this justifies the use of the bounds test approach for this study. The application of unit root tests remains imperative so that the assumption of [

18] is not infringed despite that pre-testing of variables contained in the empirical model for the order of integration, is not required for ARDL co-integration technique [

39]. Unit root test results give key information that justifies the use of the ARDL framework for co-integration analysis as the suitable technique for the evaluation. The standard Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) unit root test was employed to examine the order of integration of these variables.

Because cointegration occurs in the series, that means they exhibit a long run relationship. That also means the series can be combined in a linear function and are related. Even though there is a shock that can influence movement in each short run series, they can converge (in the long run) with time. Hence both short and long run model must be estimated. We cannot estimate VAR in this situation because we are having combined variables with I(0) and I(1) integration.

The ARDL model’s short-run coefficients for maize and sorghum, presented in

Table 17, indicate that rainfall had a positive significant effect, while temperature had, in the short run, significantly negative effect on maize output.

The results confirm a long-run relationship among variables in maize and sorghum, with significant negative coefficients for Error Correlation Model (ECM) indicating gradual adjustment Additionally, the ECM is statistically significant at the 1% level, with values of -0.0511 and -0.0701 for maize and sorghum yield, respectively, implying that about 5.11% and 7.01% of disequilibria in maize and sorghum respectively from the preceding year’s shock intersect with long-run equilibrium in the present year.

The relationships that existed among these variables imply a unit increase in temperature resulted in a 1.65 and 0.52 decrease in maize and sorghum output respectively in the short run. This could be attributed to extreme temperatures that are hazardous to maize plants. The existence of an inverse relationship between maize output and rainfall could be caused by heavy rainfall from erosion, leaching, and storms. This conforms with [

38] who opined that a significant but negative impact of rainfall on agricultural productivity.

3.7. ARDL Diagnostic Tests Analysis

The diagnostic tests detailed in

Table 18 at the 5% significance level did not reject the null hypotheses of normal distribution, non-serial correlation, and homoscedasticity.

Furthermore, stability tests using the cumulative sum of recursive residuals and cumulative sum of squares of recursive residuals, following [

40] for the ARDL model indicated movement within the critical lines of a 5% significance level reflecting parameter stability or instability. The Table reveals short-run stability in the coefficients of the ARDL model for maize and sorghum with slight long-run instability for maize and sorghum farming.

Graph of the Cumulative Sum of Recursive Residuals of Square (CUSUMsq) Tests and Cumulative Sum of Recursive Residuals (CUSUM) for ARDL Model for Maize Yield

Figure 2.

(a,b) Test of ARDL model for Maize Yield.

Figure 2.

(a,b) Test of ARDL model for Maize Yield.

Graph of the Cumulative Sum of Recursive Residuals of Square (CUSUMsq) Tests and Cumulative Sum of Recursive Residuals (CUSUM) for ARDL Model for Sorghum Yield

Figure 3.

Test of ARDL model for Sorghum Yield.

Figure 3.

Test of ARDL model for Sorghum Yield.

Conclusion

The trend analysis and growth rate of maize and sorghum yield indicated a positive trend over the study period, with maize yield rising from 0.57 to 3.8 tons ha-1 and sorghum yield increasing from 0.6 to 2.4 tons ha-1. The Just and Pope Production model revealed that various factors had a positive and significant relationship with maize and sorghum yield. The estimated response parameters for the variance of sorghum yield showed that rainfall and temperature had significant impacts on the variance of maize yield, with rainfall having an inverse relationship and temperature having a direct relationship.

The results also demonstrated a degree of variation in production of crops and risk response to severe weather across the states, with extreme temperatures having a negative association with maize yields and a positive association with sorghum. Climate variability was found to possibly impact agriculture in Nigeria as a whole, with the impact on yield varying with crop and geography. The state-level analysis revealed that severe temperatures were a major limitation for crop growth in the two states under study, and the results suggested that increases in temperature affect both the mean yield and yield risk in each state. The possible adaptive measures to be taken in order to reduce negative effects include the establishment of weather-based insurance schemes and improved irrigation.

These findings are implicative for policymakers if agricultural productivity must be enhanced, while thresholding climate change excesses. Policymakers, of essence, should prioritise investments in climate-resilient agricultural practices, focusing on drought-resistant crop varieties and providing targeted subsidies for input and advanced irrigation techniques. This is particularly important in regions vulnerable to erratic rainfall, to stabilise yields amid climate variability effects. The need to establish weather-based insurance schemes to protect farmers from climate-related risks, which would enable sustainable practices, should be underway. Precision in early warning systems by agricultural extension on impending climate vagaries such as heatwaves, needs be enshrined to help farmers implement timely mitigative decisions, including adjusting planting dates. Continued investment in agricultural research focusing on climate-resilient agricultural technologies such as precision farming, should be promoted. Policymakers should also implement sustainable land management practices, including agroforestry and soil conservation to improve soil health and crop yields. Finally, robust monitoring and evaluation frameworks that assess agricultural policy effectiveness should be put in place. This will ensure responsiveness to climate challenges.

This study is limited in geographic scope and suggests that future research directions address this limitation.

References

- FAO. World Food and Agriculture – Statistical Yearbook 2022. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations 2022.

- Nafees Akhter Farooqui; Mohd. Haleem; Wasim Khan; Mohammad Ishrat. Precision Agriculture and Predictive Analytics. IEEE 2024, pp. 171–188.

- Ayojimi, W.; Bamiro, O.M.; Otunaiya, A.O.; Shoyombo, A.J.; Matiluko, O.E. Sustainability of poultry egg output and efficiency: a risk-mitigating perspective. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1195218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, A.I.; Nzechie, O.; Obiorah, J.; Ehi, O.E.; Idakwoji, A.A. Analyzing the Critical Impact of Climate Change on Agriculture and Food Security in Nigeria. Int. J. Agric. Earth Sci. 2023, 9, 42023. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Enhancing Climate Change Mitigation through Agriculture; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzweig, C.; McDermid, S.S.; Mencos-Contreras, E.; Asseng, S.; Chattha, A.A.; Li, T.; Vellingiri, G. Integrated climate change assessments on selected farming systems in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Viet Nam. In Fostering Resilient Global Supply Chains Amid Risk and Uncertainty; ADBI Series on Asian and Pacific Sustainable Development; ADBI 2023, pp. 67–95.

- Waongo, M.; Laux, P.; Coulibaly, A.; Sy, S.; Kunstmann, H. Assessing the Impacts of Climate Change on Rainfed Maize Production in Burkina Faso, West Africa. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdisa, T.B.; Diga, G.M.; Tolessa, A.R. Impact of climate variability on rain-fed maize and sorghum yield among smallholder farmers. Cogent Food & Agriculture 2022, 8, 2057656. [Google Scholar]

- Tunde, A.M.; Usman, B.A.; Olawepo, V.O. Effects of climatic variables on crop production in Patigi LGA, Kwara State, Nigeria. J. Geography Reg. Plann. 2011, 4, 708. [Google Scholar]

- Oriola, O.; Oyeniyi, S. Changes in Climatic Characteristics and Crop Yield in Kwara State (Nigeria). Geogr. Environ. Sustain. 2017, 10, 74–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajudeen, T.T.; Omotayo, A.; Ogundele, F.O.; Rathbun, L.C. The Effect of Climate Change on Food Crop Production in Lagos State. Foods 2022, 11, 3987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lien, G.; Kumbhakar, S.C.; Mishra, A.K. Production Function and Farmers’ Risk Aversion: A Certainty Equivalent-adjusted Production Function. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 2023, 55, 324–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, A.C. Estimating Regression Models with Multiplicative heteroscedasticity. Econometrica 1976, 44, 461–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, G.; Griffiths, W.; Hill, C.; Lee, T. The Theory and Practice of Econometrics; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Just, R.E.; Pope, R.D. Production Function Estimation and Related Risk Considerations. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 1979, 61, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkoro, E.; Uko, A.K. Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) cointegration technique: application and interpretation. J. Stat. Econom. Models 2016, 5, 63–91. [Google Scholar]

- Gujarati, N.D. Basic Econometrics, 4th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Pesaran, M.H.; Shin, Y.; Smith, R.J. Bounds Testing Approaches to the Analysis of Level Relationships. J. Appl. Econom. 2001, 16, 289–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udeh, E.L.; Abdullahi, T.Y.; Balama, L. Analysis of Rainfall and Temperature Variability on Crop Yield in Lere Local Government Area of Kaduna State, Nigeria. Br. J. Earth Sci. Res. 2024, 12, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirazu, A.; Doke, D.A.; Yahaya, A. Perceived Effects of Rainfall and Temperature Variability on Yields of Cereal Crops in the Mion District of Northern Ghana. (Note: missing publication details).

- Idumah, F.O.; Mangodo, C.; Ighodaro, U.B.; Owombo, P.T. Climate Change and Food Production in Nigeria: Implication for Food Security in Nigeria. J. Agric. Sci. 2016, 8, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhassan, A.L.; Fiador, V. Insurance-Growth Nexus in Ghana: An Autoregressive Distributed Lag Bounds Cointegration Approach. Rev. Dev. Finance. [CrossRef]

- Erenstein, O.; Jaleta, M.; Sonder, K.; et al. Global maize production, consumption and trade: trends and R&D implications. Food Sec. 2022, 14, 1295–1319. [Google Scholar]

- PricewaterhouseCoopers Nigeria. Positioning Nigeria as Africa’s Leader in Maize Production for AfCFTA 2021. Available online: https://www.pwc.com/ng/en/.

- Parthasarathi, T.; Firdous, S.; Mariya David, E.; Lesharadevi, K.; Djanaguiraman, M. Effects of High Temperature on Crops; IntechOpen, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Dong, X.; Zhang, Y.; Gu, M.; Yu, Y.; Xie, H.; Yang, H.; Yu, X.; Huang, S. Heat Stress on Maize with Contrasting Genetic Background: Differences in Flowering and Yield Formation. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2022, 319, 108934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooqui, N.A.; Mishra, A.K.; Mehra, R. IOT based Automated Greenhouse Using Machine Learning Approach. Int. J. Intell. Syst. Appl. Eng. 2022, 10, 226–231. [Google Scholar]

- Adeagbo, O.A.; Ojo, T.O.; Adetoro, A.A. Understanding the determinants of climate change adaptation strategies among smallholder maize farmers in South-west, Nigeria. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalkuhl, M.; Wenz, L. The impact of climate conditions on economic production. Evidence from global panel of regions. J. Environ. Econ. Manage. 2020, 103, 102360. [Google Scholar]

- Animashaun, J.O.; Ajibade, T.B. Climate variability, absorptive capacity and economic performance in Sub-Saharan Africa. J. Agribus. Rural Dev. 2020, 1, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, J.R.; Vincent, J.R.; Auffhammer, M.; Moya, P.F.; Dobermann, A.; Dawe, D. Rice yield in tropical/subtropical Asia exhibit large but opposing sensitivities to minimum and maximum temperatures. PNAS 2010, 107, 14562–14567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obaniyi, K.S.; Aremu, C.O.; Adeyonu, A.G.; Chibueze, M.K. Effects of climate change on the health of rural farming households in Oyun Local government Area of Kwara State Nigeria. Journal of Agricultural Extension 2023, 28, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olagunju, I.F.; Adeojo, R.J.; Ayojimi, W.; Awe, T.E.; Oriade, O.A. Causal nexus between agricultural credit rationing and repayment performance: A two-stage Tobit regression. AIMS Agric. Food 2023, 8, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calmon, M.; Feltran-Barbieri, R. 4 ways farmers can adopt to climate change and generate income; World Resources Institute, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon, J.G. Numerical Distribution Functions for Unit Root and Cointegration Tests. J. Appl. Econom. 1996, 11, 601–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shittu, A.; Kehinde, M.; Adeyonu, A.; Ojo, O. Willingness to Accept Incentives for a Shift to Climate-Smart Agriculture among Smallholder Farmers in Nigeria. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 2021, 53, 531–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayinde, O.E.; Ajewole, O.O.; Ogunlade, I.; Adewumi, M.O. Empirical Analysis of Agricultural Production and Climate Change: A Case Study of Nigeria. J. Sustain. Dev. Afr. 2010, 12, 275–283. [Google Scholar]

- Gershon, O.; Mbajekwe, C. Investigating the nexus of climate and agricultural production in Nigeria. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2020, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kripfganz, S.; Schneider, D.C. ardl: Estimating autoregressive distributed lag and equilibrium correction models. Stata J. 2023, 23, 983–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.L.; Durbin, J.; Evans, J.M. Techniques for Testing the Constancy of Regression Relations Over Time. J.R. Stat. Soc. 1975, 3, 149–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).