1. Introduction

Polyether-based urethanes (PEUs) are thermoplastic elastomers widely used in implantable medical devices due to their favorable mechanical properties, biocompatibility,[

1,

2,

3] and ease of processing. Among these, Pellethane

®, a medical grade polyurethane,[

4] has been extensively applied in cardiovascular applications such as pacemaker leads,[

5,

6] vascular grafts, catheters, and delivery sheaths. Its well-established hydrolytic stability under physiological conditions makes it suitable for long-term use in intravascular and subcutaneous environments, where long-term chemical and mechanical stability is critical.[

7,

8]

Despite its clinical history, limited data exist on the long-term in vivo performance of PEUs under dynamic, blood-contacting environments like the heart. Although PEUs are resistant to hydrolysis,[

9,

10] they are susceptible to oxidative degradation, particularly via reactive oxygen species generated during chronic inflammation. Hydrolysis typically leads to bulk degradation, whereas oxidation affects the surface, potentially compromising structural integrity. These degradation modes are influenced by local physiological conditions and the material’s morphology, making the implantation site and duration key factors in predicting material stability.[

11,

12,

13,

14]

Previous studies have explored the chemical stability and degradation behavior of PEUs using in vitro accelerated aging models.[

15,

16] However, there remains a lack of comprehensive data regarding the long-term chemical and morphological integrity of these materials following implantation in dynamic biological environments such as the heart. In particular, hydrolytic and oxidative stress factors in vivo need to be evaluated separately from previous devices,[

9] as they may be affected differently by the surrounding environment, such as blood flow, pulsatile shear stress, and inflammatory responses, as well as by the type of device manufactured.[

17,

18]

In this study, the polyether-based urethane implantable device (PUID) composed of Pellethane

® was chronically implanted adjacent to the tricuspid valve annulus, maintaining continuous contact with the right atrial wall under physiological cardiac motion.[

19,

20] The study evaluated thrombosis, inflammation, and material degradation, along with histological analysis of adjacent cardiac tissues.

To further assess the material’s long-term biostability, the recovered Pellethane

® component 24 weeks after implantation was analyzed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), gel permeation chromatography (GPC), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), and nuclear magnetic resonance (¹H-NMR) according to ISO 5910:2024[

28]

Additional supporting data were obtained through extended chemical characterization, ISO10993 biocompatibility [

21,

22,

23,

24], hemocompatibility, extraction and leaching toxicological assessment.[

25,

26,

27]

The integrated evaluation combining biological assessment and material biostability aims to establish comprehensive performance data for Pellethane® based devices in long-term, blood-contacting, catheter delivered applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

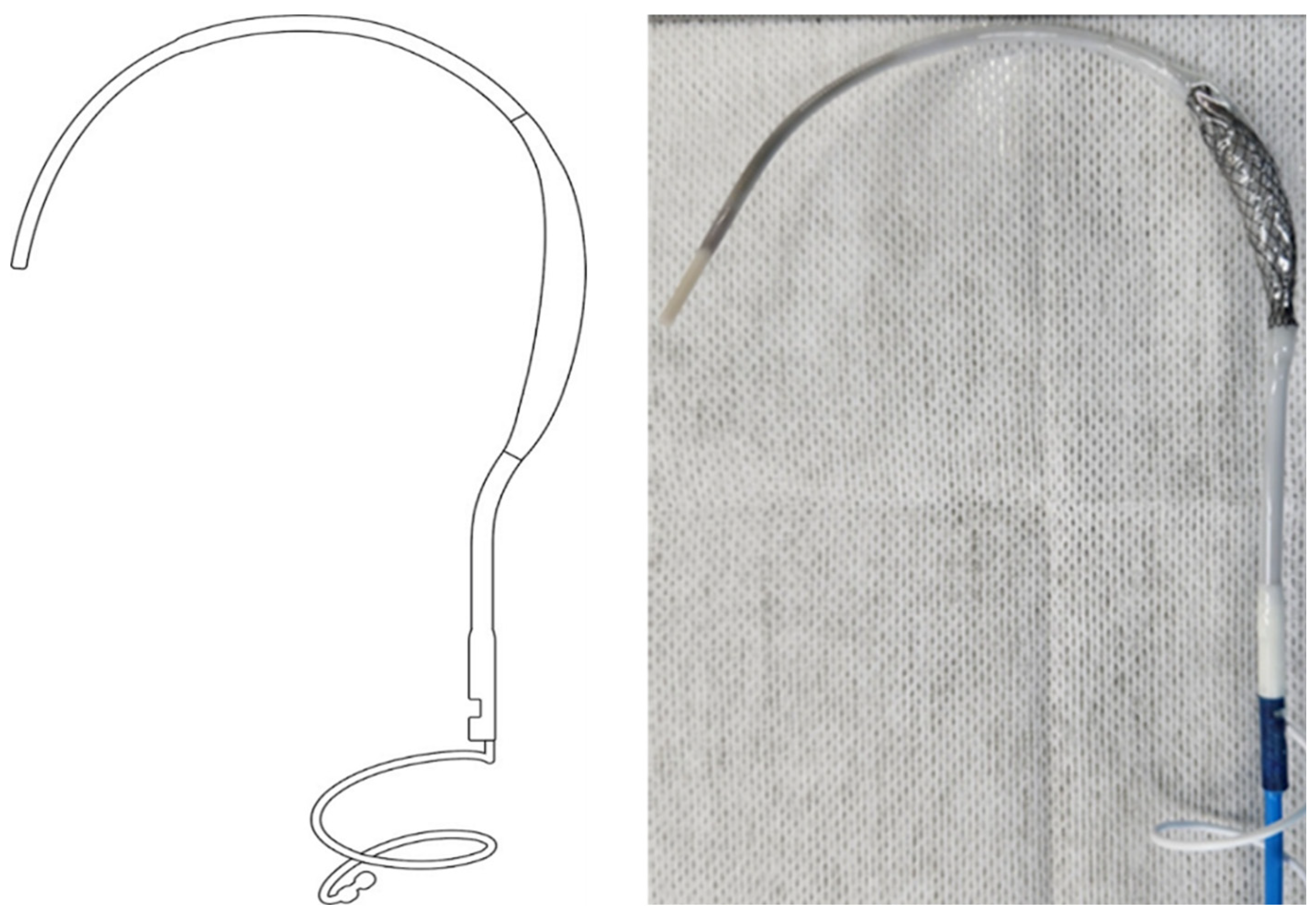

The balloon spacer and shaft components of the

PUID were made from Pellethane

® and thermoformed following a controlled fabrication process to ensure dimensional consistency. Although the PUID includes other components, the analysis in this study focused specifically on the Pellethane

®-based elements. Control samples were prepared using the same fabrication process, and all specimens were EO-sterilized prior to testing.

(Figure 1)

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Animal Study Design

Seven farm pigs (mean weight 38.8 ± 0.8 kg) underwent femoral vein catheterization for PUIDs implantation at the tricuspid annulus under fluoroscopic guidance (Integris H5000F; Philips Medical Systems, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). PUIDs positioning was continuously monitored using fluoroscopy and echocardiography[

19]. During the 24-week survival period, animals received daily oral rivaroxaban (20 mg) to reduce thrombotic risk. At the end of the study, all animals were euthanized, and their hearts and surrounding tissues were explanted for comprehensive histopathological and material analysis. All procedures were conducted in accordance with NIH guidelines and the Animal Care and Use Committee policies of Pusan National Yangsan University Hospital (PNUYH), with study protocols approved by the PNUYH IRB (No. 2021-007-A1C0[0]).

2.2.2. Histological Analysis

Cardiac tissues were fixed, paraffin-embedded, and sectioned (5 µm) for H&E staining. Parameters assessed included fibrosis, histiocytic infiltration, hemorrhage, and inflammation.

2.2.3. Analytical Methods

To evaluate the in vivo chemical and morphological stability of the balloon spacer component of the PUID, which was fabricated from Pellethane® 80A, samples were subjected to a series of standardized analytical techniques. Devices retrieved after 24 weeks of implantation were rinsed with physiological saline, air-dried for 48 hours, and the balloon spacer component was sectioned into approximately 1 cm × 1 cm pieces (T1: implanted samples for 24 weeks). For comparison, non-implanted control specimens of the same PEU balloon spacer, fabricated using an identical manufacturing process, were prepared (T0: non-implanted controls). All analytical evaluations, including surface imaging, chemical structure analysis, and molecular weight determination, were conducted using both T0 and T1 samples.

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) was performed using a Sigma 300VP (Carl Zeiss Microscopy Ltd., UK) after platinum (Pt) coating to evaluate surface morphology and identify signs of microcracking, delamination, or general surface degradation. Imaging was conducted at magnifications of ×500 and ×1000 across three predefined regions of each sample: immediate, proximal, and distal sections.

Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR) was performed in attenuated total reflectance (ATR) mode using a Nicolet iS50 spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) to assess the chemical structural integrity. Absorbance spectra were collected in the range of 600–4000 cm⁻¹ with a resolution of 4 cm⁻¹. Comparative analysis between implanted and non-implanted samples was conducted to identify potential oxidative or hydrolytic modifications, with particular attention to characteristic peaks corresponding to urethane, ether, and alkyl groups.

Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) was employed to evaluate changes in molecular weight distribution. The analysis was performed using a Waters ACQUITY APC System with dimethylformamide (DMF) as the eluent at a flow rate of 0.3 mL/min. The column temperature was maintained at 40 °C, and detection was carried out using a refractive index (RI) detector. The injection volume was 50 μL, with a total run time of 30 minutes. Calibration was conducted using polystyrene standards. The number-average molecular weight (Mₙ) and weight-average molecular weight (Mw) were calculated to assess potential polymer chain scission or crosslinking induced by in vivo exposure.

1H-NMR spectroscopy was performed using a Bruker Avance Neo 600 MHz solid-state ¹H-NMR spectrometer with deuterated tetrahydrofuran (THF-d₈) as the solvent. Spectra were acquired for both implanted and control samples to evaluate urethane bond stability, detect any new chemical shifts, and assess the overall integrity of the molecular structure.

All procedures were conducted under consistent conditions using both qualitative and quantitative chemical characterization methods, as outlined in ISO 10993-18:2020. In addition, literature-based information was incorporated, where appropriate, to complement the experimental data in accordance with ISO 10993-18:2020.

2.2.4. Biocompatibility Testing Method

Biocompatibility testing was conducted using a fully sterilized device featuring a balloon structure composed of Pellethane®. The PUID was manufactured using the company’s proprietary production process to accurately represent actual patient exposure. All biocompatibility testing was conducted in accordance with ISO 10993-1:2018 and Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) standards. The studies were performed by GLP-certified laboratories NAMSA (North American Science Associates, LLC) and Nelson Laboratories ensuring both data reliability and compliance with relevant regulatory requirements.

A comprehensive suite of biocompatibility evaluations was carried out, and the results are summarized in

Table 2.

2.2.5. Chemical Characterization

Chemical characterization was conducted by Eurofins Munich, in accordance with [

27] ISO 10993-17:2023 and ISO 10993-18:2020, to assess potential toxicological risks. In accordance with ISO 10993-12: Sample preparation and reference materials and ISO 10993-18:2020, chemical characterization was conducted to evaluate the release of extractable substances, including nonvolatile residues (NVR) and semi-volatile organic compounds, from PUIDs.

Extractions were performed from the implant site of the device at a surface area-to-extraction volume ratio of 1 cm²/mL, following the protocol outlined in ISO 10993-12. To simulate physiological and clinically relevant conditions, five consecutive extractions were carried out in water (polar), isopropanol (semi-polar), and n-hexane (nonpolar) at 50 °C for 24 hours each. The test materials were agitated during extraction to enhance release. The procedure was repeated until the complete removal of nonvolatile residues was confirmed gravimetrically. The resulting extracts were then analyzed using the techniques recommended in ISO 10993-18:2020 (Chemical characterization of medical device materials within a risk management process), specifically those listed below. Test methods for establishing the material composition of medical device materials of the standard :

Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS): Used to analyze semi-volatile organic compounds. Semi-quantitative analysis was performed by external calibration using surrogate standards with retention times closest to the detected analytes.

Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS): Applied to the final extracts in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to quantify elemental and inorganic constituents.

Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS): Employed to detect polar and thermally labile compounds not amenable to GC-MS analysis. LC-MS results complemented the GC-MS data by identifying additional low-volatility substances.

Substance identification was supported by spectral matching using both the NIST mass spectral library and the proprietary internal database of Eurofins Munich. The highest intensity peaks observed in each solvent system were prioritized for identification.

Threshold-based evaluations were conducted using AET, PDE, and TTC approaches, and Margin of Safety (MoS) values were calculated for substances with established exposure limits. Unidentified substances were assumed to be polymer degradation products and evaluated accordingly. Pooled extract results were used to estimate worst-case exposures.

This multi-technique analytical approach ensured comprehensive profiling of extractable chemical constituents in compliance with international standards, supporting the risk assessment of the material’s suitability for prolonged or permanent contact with human tissues and body fluids.

2.2.6. Statistical Analysis

All quantitative data obtained from animal experiments and material characterization were summarized using descriptive statistics, including mean ± standard deviation. Given the exploratory nature of the porcine study and the limited sample size (n=6), no formal hypothesis testing or inferential statistical comparisons were performed. Instead, reproducibility and consistency across animals were assessed by evaluating variability trends for device positioning, histological scoring, and analytical measurements (SEM, FT-IR, GPC, and ¹H-NMR). All statistical analyses and data tabulations were conducted using standard spreadsheet-based tools, and results were interpreted qualitatively to determine whether implanted samples deviated meaningfully from non-implanted controls. This statistical approach is consistent with preclinical large-animal studies focused on biostability and material integrity rather than hypothesis-driven comparative testing.

3. Results

3.1. Device Stability and Positioning

All seven farm pigs underwent successful implantation of PUIDs via a percutaneous femoral vein approach. Correct positioning of the devices at the tricuspid annulus within the right atrium was verified by both fluoroscopy and echocardiography. Over the 24-week observation period, the implants remained stable without evidence of migration, displacement, rupture, or mechanical failure. One animal was excluded from the final analysis due to a procedure-related infection; the remaining six animals maintained consistent device integrity and positioning throughout the study.

3.2. Histological Findings

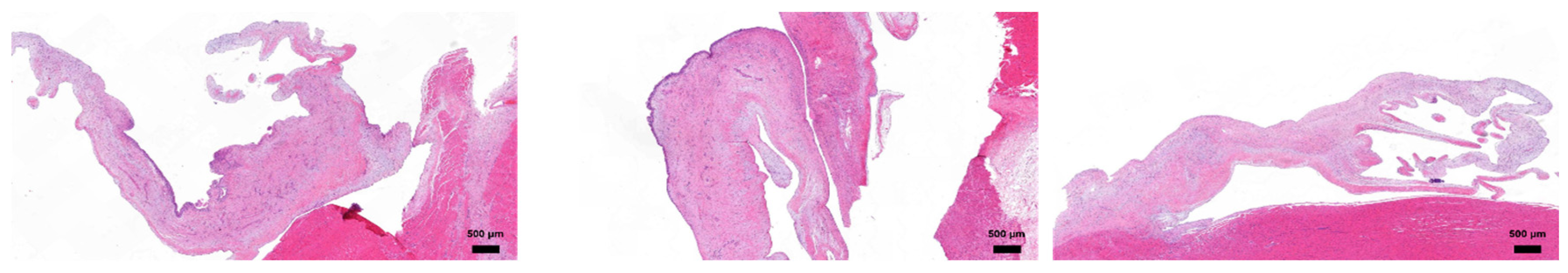

Histological examination of explanted heart tissues at the 24-week endpoint revealed favorable biocompatibility of the PUID.

Figure 2

Histopathological evaluation was conducted on explanted porcine hearts 24 weeks post-implantation of PUIDs. The anterior tricuspid leaflet exhibited preserved overall architecture with areas of moderate thickening. Occasional cellular responses, including histiocytic activity, were observed in localized regions, consistent with a mild host tissue response. The posterior leaflet generally maintained structural integrity, with only minor focal thickening near the implant interface. Inflammatory or foreign body reactions were limited and confined to specific sites, indicating stable tissue compatibility over time. The septal leaflet appeared structurally intact without signs or architectural distortion. No notable chronic inflammation or adverse remodeling was observed in this region, suggesting stable interaction with the surrounding cardiac tissue.

3.3. Biocompatibility

The medical device, the PUID manufactured in accordance with internal process protocols, was subjected to extraction testing based on surface area to reflect patient exposure. A biological safety assessment was conducted in compliance with ISO 10993 standards and Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) regulations. A summary of each test is presented in

Table 1. below.

The biological safety and chemical characterization assessments are essential to confirm patient safety prior to clinical evaluation and to ensure the in vivo biocompatibility of the implantable medical device.

Table 1.

Biocompatibility test Summary.

Table 1.

Biocompatibility test Summary.

| Test description |

Relevant std |

Results |

Test institute |

| Cytotoxicity with Quantitative Evaluation (MTT) |

ISO 10993-5:2009 |

No significant cytotoxicity observed; cell viability exceeded 70% compared to control, meeting ISO 10993-5 criteria. (PASS) |

Nelson labs |

| Intracutaneous Reactivity test |

ISO 10993-23:2021 |

No significant intracutaneous irritation observed in rabbits, meeting ISO 10993-10 and ISO 10993-23 criteria. (PASS) |

Nelson labs |

| Hemolysis test |

ISO 10993-4:2017, ASTM F756-17 |

No significant hemolytic activity observed; hemolysis levels were well below 2%, meeting ASTM criteria. (PASS) |

Nelson labs |

| Partial Thromoboplastin time test |

ISO 10993-4:2017, ASTM F2382-18 |

No significant effect on plasma coagulation time observed, meeting ASTM F2382 requirements. (PASS) |

NAMSA |

| Platelet and Leucocyte count test |

ISO 10993-4:2017 |

No significant effect on platelet count observed, meeting ASTM and ISO hemocompatibility criteria. (PASS) |

NAMSA |

| Complement Activation test |

ISO 10993-4:2017 |

No significant complement activation observed compared to controls, meeting ISO 10993-4 requirements. (PASS) |

Nelson labs |

| Sensitization test |

ISO 10993-10:2021 |

No sensitization reactions observed in guinea pigs, meeting ISO 10993-10 requirements. (PASS) |

Nelson labs |

| Pyrogen test |

ISO 10993-11:2017

USP-NF-<151>(2017) |

No significant pyrogenic response observed, meeting ISO 10993-11 acceptance criteria. (PASS) |

Nelson labs |

| Acute systemic toxicity test |

ISO 10993-11:2017 |

No acute systemic toxicity observed over 72 hours; all animals survived with no significant clinical or necropsy findings. (PASS) |

Nelson labs |

| Sub Chronic toxicity test |

ISO 10993-11:2017 |

No subacute or subchronic systemic toxicity observed; findings related to administration, not test article. (PASS)” |

Nelson labs |

| Subcutaneous 13week Implant test |

ISO 10993-6:2016 |

Acceptable local tissue compatibility demonstrated; minimal inflammation, normal capsule formation, and no significant pathology observed. (PASS) |

NAMSA |

Reverse mutation

(AMES) test |

ISO 10993-3:2014 |

No mutagenic activity observed in bacterial reverse mutation assay, with or without metabolic activation. (PASS) |

Nelson labs |

| Chromosome Aberration test |

ISO 10993-3:2014 |

No significant chromosomal aberrations observed in mammalian cells, indicating no clastogenicity. (PASS) |

Nelson labs |

| Chronic Toxicity test |

ISO 10993-11:2006 |

No evidence of chronic toxicity based on risk assessment and study data, supporting waiver of chronic toxicity testing per ISO 10993-1 and FDA guidance. (PASS) |

Eurofins |

| Carcinogenicity test |

ISO 10993-3:2003 |

No evidence of carcinogenicity based on genotoxicity results, chemical characterization, literature, and implantation data, in line with ISO 10993-1 and FDA guidance. (PASS) |

Eurofins |

3.4. Toxicological Assessment

In this study, the release of nonvolatile residues (NVRs) and semi-volatile organic extractables from the test article specifically, the PUID was analyzed following liquid extraction.

The highest detected peaks in each of the three solvents were characterized using the NIST mass spectral library and Eurofins Munich’s internal material library. Chemical analysis of the test article extracts identified semi-volatile, nonvolatile, and elemental substances that may be released under laboratory conditions. Most of the detected compounds were found at levels below the Analytical Evaluation Threshold (AET) or the Permitted Daily Exposure (PDE) limits and therefore did not require further toxicological assessment.

Due to the consistent patterns observed in the chromatographic profiles, the 50 most prominent peaks in each extractables study were selected for characterization. These peaks were shown to represent structurally related compounds, primarily consisting of monomeric or oligomeric derivatives. Among them, four distinct compounds were detected at concentrations exceeding the AET and were therefore subjected to a comprehensive toxicological risk assessment in accordance with ISO 10993-17:2023.

Each of the four substances was fully identified and associated with a CAS number, enabling toxicological reference checks in established databases such as PubChem, ECHA, GESTIS, and INCHEM. Following identification, toxicological limit values were retrieved from the literature, with preference given to studies closely aligned with the clinical use of the medical device particularly in terms of exposure route, duration, and species. Oral or parenteral thresholds were prioritized when available.

Subsequently, tolerable intake (TI) values were calculated for each substance using reference points such as NOAEL, LOAEL, DNEL, or TDI. A default uncertainty factor of 10 was applied to account for differences between the experimental conditions in the literature and the intended clinical application of the device. These TI values were then compared to the estimated worst-case exposure levels to derive the Margin of Safety (MoS). In all cases, the MoS values exceeded 1, indicating an acceptable safety margin.

The derived values for TI and EEDmax for the four substances are presented in the

Table 2.

Table 2.

Determination of the tolerable Intake (TI) and the estimation exposure dose (EEDmax).

Table 2.

Determination of the tolerable Intake (TI) and the estimation exposure dose (EEDmax).

| |

Substance (Solvent) |

TI

[µg/kg BW/day]

|

EEDmax

[µg/kg Bw/day]

|

| Isopropanol (GC-MS) |

Butylated Hydroxytoluene |

25 |

0.47 |

| Erucamide |

1000 |

0.02 |

| Octadecyl 3-(3,5-di-tert-butyl-4-hydroxyphenyl) propionate |

64 |

0.97 |

| n-Hexane (GC-MS) |

Butylated Hydroxytoluene |

25 |

0.20 |

| Erucamide |

1000 |

0.01 |

| Octadecyl 3-(3,5-di-tert-butyl-4-hydroxyphenyl) propionate |

64 |

0.32 |

| n-Hexane (HPLC-MS) |

Irganox 1076 (Octadecyl 3-(3,5-di-tert-butyl-4-hydroxyphenyl) propionate) |

64 |

43.46 |

Additionally, unidentified extractables primarily hydrolysis products of polymeric materials were not considered toxicologically relevant. These substances were further assessed through implantation and biocompatibility studies, all of which showed no signs of toxicity or mutagenicity. Taken together, both the four AET-exceeding substances and all other extractables were determined to pose no toxicological risk under the tested conditions.

3.5. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

High-resolution images of the material surface were used to assess the presence of brittleness and surface cracking. SEM analysis showed that the surface morphology of T1 samples was well maintained after 24 weeks of implantation. The surface appeared smooth and intact, with no evidence of cracking, brittleness, or severe erosion, closely resembling that of the T0 samples. No signs of oxidative or hydrolytic degradation were observed in the T1 samples during the implantation period

(Figure 3).

3.6. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR)

Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy of the implanted PEU grafts demonstrated that the chemical structure of the material was preserved after 24 weeks of intracardiac implantation. The C=O stretching vibration around 1700 cm⁻¹ and the combined N–H bending and C–N stretching near 1530 cm⁻¹ were well maintained in T1 samples, showing strong similarity to T0 samples, indicating that the core urethane structure remained intact after implantation. In addition, peaks in the 1100–1300 cm⁻¹ region, corresponding to ether (C–O–C) and C–N vibrations, showed minimal variation, supporting the stability of the polymer backbone.

The characteristic absorption bands associated with urethane (-NH, -C=O), ether (C-O-C), and alkyl (C-H) groups remained stable, with no significant peak shifts or formation of new bands. Moreover, no additional changes were observed in T1 samples compared to the spectra obtained from T0 samples (

Figure 4).

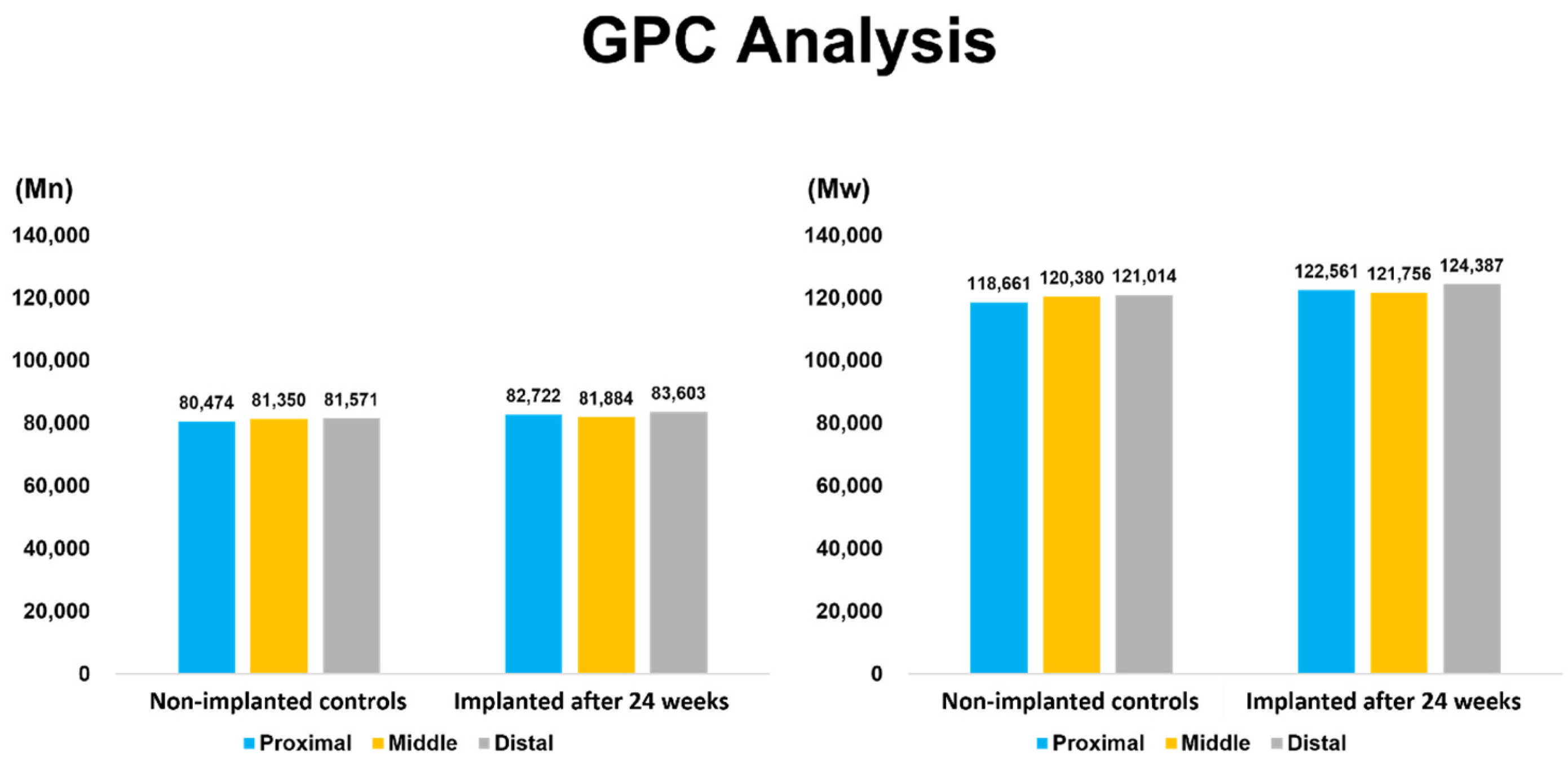

3.7. Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC)

Gel permeation chromatography (GPC) analysis demonstrated that the number-average molecular weight (Mₙ) and weight-average molecular weight (Mₚ) of T1 samples after 24 weeks of implantation were comparable to those of T0 Samples. The molar mass distribution remained consistent, with no indication of polymer chain scission or bulk degradation, indicating that the material maintained its molecular stability under in vivo conditions (

Figure 5).

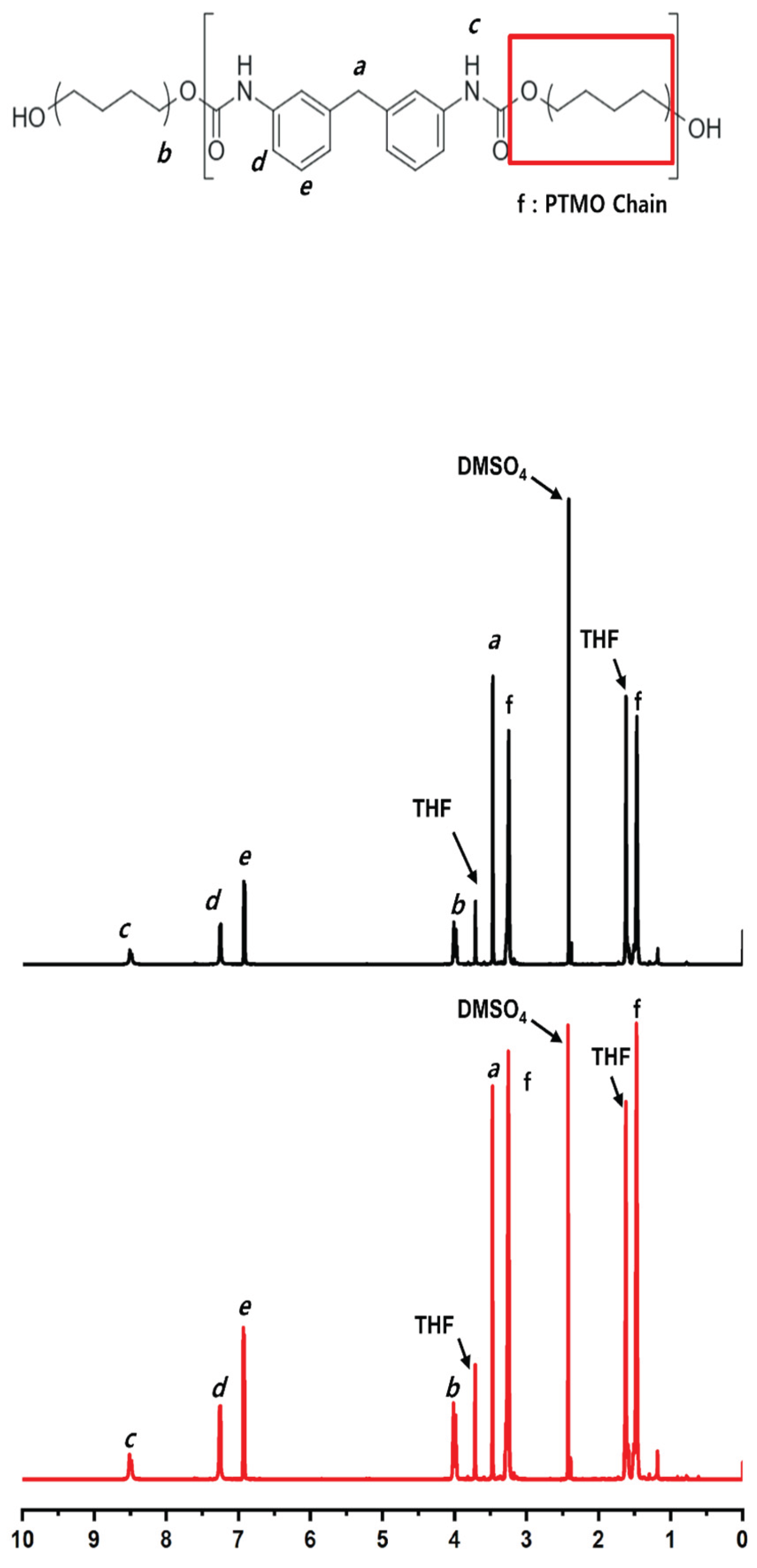

3.8. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (¹H-NMR)

Nuclear magnetic resonance (¹H-NMR) spectroscopy of T1 samples after 24 weeks of implantation exhibited well-resolved signals assignable to distinct proton environments within the polymer. Aromatic protons appeared at 7.2–7.6 ppm, with para- and meta-substituted protons assigned to 7.2–7.4 ppm and 7.4–7.6 ppm, respectively. Methylene protons adjacent to the urethane linkage (–CH₂–NH–COO–) were observed at approximately 4.0 ppm. Signals in the range of 3.4–3.8 ppm were attributed to ether-linked methylene groups or methylene units within the polytetramethylene oxide (PTMO) backbone. The urethane N–H proton was observed at 8.1–8.4 ppm.

These characteristic signals showed no significant chemical shift changes or appearance of new peaks. The spectral profiles of T1 samples were comparable to those of T0 samples, with no additional signals indicating chemical alteration

(Figure 6).

4. Discussion

This study aimed to assess the long-term in vivo biostability of Pellethane® used specifically in the balloon spacer component, as well as the overall biocompatibility of the fully assembled PUID device following implantation. The design rationale centered on the need for a robust, durable, and inert spacer material that could maintain performance without requiring surface coatings.

Informed by prior studies on the original Pivot Mandu device, which featured a three-layered structure composed of an inner polyurethane balloon, a nitinol mesh support, and an outer ePTFE coating, we implemented a key design modification in this study: the removal of the outer ePTFE layer. This change allowed us to evaluate the long-term durability and chemical stability [

5,

7,

8]of Pellethane

® as the sole exposed balloon material, thereby simplifying the device structure and focusing on the critical performance of the polyurethane membrane under physiological conditions. Moreover, the removal of the ePTFE layer resolved the elastic mismatch issue that could otherwise create interlayer gaps, providing a justification for the design change and ensuring consistent conformity to the intended target size.

Through a comprehensive 24-week preclinical study in a porcine model, we combined histological evaluation with analytical techniques to evaluate the biological and physicochemical responses to the implanted device. The device remained stably positioned in all animals (excluding one excluded due to procedural infection), without evidence of structural failure, migration, or mechanical compromise. This is particularly important because intracardiac devices are continuously subjected to cyclical mechanical stress from cardiac motion. Fluoroscopic and echocardiographic assessments confirmed stable positioning throughout the implantation period, demonstrating mechanical compatibility with dynamic intracardiac anatomy.

Histological analysis showed only mild and localized tissue responses. H&E staining revealed limited fibrotic encapsulation, minimal histiocytic infiltration, and localized inflammation at the tissue implant interface. Notably, endothelialization was observed in several specimens, suggesting integration potential without inducing excessive inflammatory or foreign body responses. These results support the biological inertness of the single layer Pellethane® balloon spacer in a high-shear blood-contacting environment.

Parallel to tissue-level evaluation, material degradation was assessed using a series of orthogonal analytical techniques. SEM analysis showed no evidence of microcracking, delamination, or surface embrittlement, indicating minimal surface-level oxidative degradation.[

5,

29]FT-IR spectra of explanted samples confirmed the preservation of characteristic urethane and ether peaks, with no appreciable loss in absorption intensity. These findings confirm that the polymer’s chemical structure remained intact after 24 weeks of implantation.

GPC analysis revealed stable number-average and weight-average molecular weights (Mn and Mw), indicating no detectable bulk degradation, and confirming the polymer’s resistance to hydrolysis[

5,

9] over the study period. ¹H-NMR analysis showed no chemical shift changes or signal pattern alterations, reinforcing the absence of chain scission or chemical rearrangement.

These findings are consistent with previous reports on the biostability of Pellethane

®. Polyether based urethanes (PEUs), such as Pellethane

®, are well recognized for their strong resistance to hydrolytic degradation a property supported by long-term clinical data showing no significant molar mass reduction even after more than a decade of implantation [

5]. This hydrolytic stability is particularly critical for long-term implantable devices, as bulk degradation driven by hydrolysis can severely compromise mechanical performance [

29]. Although oxidative degradation has been observed in clinically retrieved PEU-based devices, its effects are largely limited to the surface and do not significantly impact overall device function. The absence of substantial chemical or mechanical degradation over time supports the design decision to simplify the original Pivot Mandu configuration by removing the outer ePTFE layer.

In addition to material biostability evaluation, biocompatibility testing was performed in accordance with ISO 10993-1 and ISO 10993-18 standards. No cytotoxicity, genotoxicity, or systemic toxicity was observed, and all extractables remained within acceptable analytical evaluation threshold (AET) and permitted daily exposure (PDE) limits.

Collectively, this study provides strong evidence that the modified Pellethane® based PUID maintains structural and chemical stability under chronic intracardiac conditions. By integrating histopathological, mechanical, and chemical analyses, we offer a comprehensive perspective on the in vivo behavior of polyurethane-based materials in long-term blood-contacting applications. This simplified design, eliminating surface coatings while preserving biocompatibility and durability, supports the future use of PEUs in catheter-delivered, permanent cardiac implants.

5. Conclusions

The 24 weeks preclinical study of the PUID demonstrated excellent in vivo biostability and biocompatibility when used as an intracardiac spacer for transcatheter tricuspid valve intervention. The device maintained its molecular integrity, structural morphology, and surface characteristics, with no significant degradation or adverse host tissue response. These findings support the use of Pellethane® as a durable material platform for future catheter-based cardiovascular devices.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to this work as follows: Conceptualization, M.-G.K. and M.-K.C.; Methodology and Investigation, M.-G.K., J.-Y.S. and M.-K.C.; Validation, Formal Analysis, Data Curation, and Resources, M.-G.K., J.-Y.S., J.-C.K. and K.-D.S.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation and Visualization, M.-G.K., J.-Y.S. and M.-K.C.; Writing—Review and Editing, Supervision, and Project Administration, J.-H.K.; Funding Acquisition, J.-H.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a 2-Year Research Grant of Pusan National University.

References

- Vermette, P; Wang, GB; Santerre, JP; Thibault, J; Laroche, G. Commercial polyurethanes: the potential influence of auxiliary chemicals on the biodegradation process. Journal of Biomaterials Science, Polymer Edition 1999, 10(7), 729–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, GT. Biodegradation of polyurethane: a review. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation 2002, 49(4), 245–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterman, KC; Adami, RC; Alsante, KM; Antipas, AS; Arenson, DR; Carrier, R; et al. Hydrolysis in pharmaceutical formulations. Pharmaceutical development and technology 2002, 7(2), 113–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K; Feng, Q; Fang, Z; Gu, L; Bian, L. Structurally dynamic hydrogels for biomedical applications: pursuing a fine balance between macroscopic stability and microscopic dynamics. Chemical Reviews 2021, 121(18), 11149–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, R; Chaffin, K; Shah, A; Westerman, S; Lloyd, M; Bhatia, N; et al. Evaluation of the in vivo chemical reactivity of a novel copolymer insulation on cardiac leads in a single-center study. Heart Rhythm 2024, 21(8), 1334–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, K; Cobian, K. Polyether polyurethanes for implantable pacemaker leads. Biomaterials 1982, 3(4), 225–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaffin, KA; Buckalew, AJ; Schley, JL; Chen, X; Jolly, M; Alkatout, JA; et al. Influence of water on the structure and properties of PDMS-containing multiblock polyurethanes. Macromolecules 2012, 45(22), 9110–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaffin, K. Longevity expectations for polymers in medical devices demand new approaches to evaluating their biostability. ACS Macro Letters 2020, 9(12), 1793–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, S; Untereker, D. Degradability of polymers for implantable biomedical devices. International journal of molecular sciences 2009, 10(9), 4033–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stokes, K; McVenes, R; Anderson, JM. Polyurethane elastomer biostability. Journal of biomaterials applications 1995, 9(4), 321–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanna, V. Adhesion–delamination phenomena at the surfaces and interfaces in microelectronics and MEMS structures and packaged devices. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics 2010, 44(3), 034004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, CC; Cheacharoen, R; Leijtens, T; McGehee, MD. Understanding degradation mechanisms and improving stability of perovskite photovoltaics. Chemical reviews 2018, 119(5), 3418–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B; Martín, C; Kurapati, R; Bianco, A. Degradation-by-design: how chemical functionalization enhances the biodegradability and safety of 2D materials. Chemical Society Reviews 2020, 49(17), 6224–47. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, Q; Zhou, Q; Shi, L; Chen, Q; Wang, J. Recent advances in oxidation and degradation mechanisms of ultrathin 2D materials under ambient conditions and their passivation strategies. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2019, 7(9), 4291–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaffin, KA; Chen, X; McNamara, L; Bates, FS; Hillmyer, MA. Polyether urethane hydrolytic stability after exposure to deoxygenated water. Macromolecules 2014, 47(15), 5220–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langueh, C; Changotade, S; Ramtani, S; Lutomski, D; Rohman, G. Combination of in vitro thermally-accelerated ageing and Fourier-Transform Infrared spectroscopy to predict scaffold lifetime. Polymer Degradation and Stability 2021, 183, 109454. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, JA; Uryash, A; Lopez, JR. Non-invasive pulsatile shear stress modifies endothelial activation; a narrative review. Biomedicines 2022, 10(12), 3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girdhar, G; Bluestein, D. Biological effects of dynamic shear stress in cardiovascular pathologies and devices. Expert review of medical devices 2008, 5(2), 167–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chon, M-K; Lee, S-W; Hahn, J-Y; Park, Y-H; Kim, H-S; Lee, S-H; et al. A novel device for tricuspid regurgitation reduction featuring 3-dimensional leaflet and atraumatic anchor: Pivot-TR system. Basic to Translational Science 2022, 7(12), 1249–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chon, M-K; Jung, S-J; Seo, J-Y; Shin, D-H; Park, J-H; Kim, H-S; et al. The Development of a Permanent Implantable Spacer with the Function of Size Adjustability for Customizing Treat Regurgitant Heart Valve Disease. Bioengineering 2023, 10(9), 1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funk, KA; Hampshire, VA; Schuh, JC. Nonclinical safety evaluation of medical devices; Toxicologic Pathology: CRC Press, 2018; pp. 95–152. [Google Scholar]

- Fadilah, NIM; Ahmat, N; Hao, LQ; Maarof, M; Rajab, NF; Idrus, RBH; et al. Biological safety assessments of high-purified ovine collagen type I biomatrix for future therapeutic product: International Organisation for Standardisation (ISO) and Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) settings. Polymers 2023, 15(11), 2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

ISO 10993-17; Biological evaluation of medical devices — Part 17: Toxicological risk assessment of medical device constituents. 2023.

-

ISO 10993-18; 2020 Biological evaluation of medical devices — Part 18: Chemical characterization of medical device materials within a risk management process.

- Albert, D. Material and chemical characterization for the biological evaluation of medical device biocompatibility; Biocompatibility and performance of medical devices: Elsevier, 2012; pp. 65–94. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H-MD; Thakur, P; Thakur, A. Biocompatibility, bio-clearance, and toxicology; Integrated nanomaterials and their applications: Springer, 2023; pp. 201–21. [Google Scholar]

- Sussman, EM; Oktem, B; Isayeva, IS; Liu, J; Wickramasekara, S; Chandrasekar, V; et al. Chemical characterization and non-targeted analysis of medical device extracts: a review of current approaches, gaps, and emerging practices. ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering 2022, 8(3), 939–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

ISO 5910:2024; Cardiovascular implants and extracorporeal systems — Cardiac valve repair devices.

- Goetjes, V; Zarges, J-C; Heim, H-P. Differentiation between hydrolytic and thermo-oxidative degradation of poly (lactic acid) and poly (lactic acid)/starch composites in warm and humid environments. Materials 2024, 17(15), 3683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).