1. Introduction

Industrial batch processes in food and beverage, pharmaceuticals, and wastewater treatment depend critically on cleaning-in-place (CIP) operations and similar multi-stage procedures to guarantee hygiene, product quality, and regulatory compliance [

1,

2]. These cycles typically execute multi-stage programs—for example, pre-rinse, alkaline wash, intermediate rinse, acid wash, sanitising and final rinse— under tight constraints on temperature, flow, conductivity and contact time [

2,

3]. In current practice, such sequences are orchestrated by programmable logic controllers (PLCs) and supervised through SCADA systems, where operators monitor trends, acknowledge alarms and manually interpret complex process conditions. While this architecture is robust and widely adopted, it offers limited support for proactive decision making, root-cause analysis or flexible what-if exploration over historical and real-time data—limitations that become increasingly problematic as plants grow in complexity and product portfolios diversify [

3,

4].

To address the need for flexibility and scalability, recent Industry 4.0 frameworks advocate modular, component-based and microservice-oriented architectures for industrial automation [

5,

6]. These approaches promote loose coupling between control, monitoring, data management and higher-level applications, enabling incremental deployment and technology heterogeneity. Previous work on component-based microservices for bioprocess automation has shown that containerised services and publish/subscribe communication can decouple control and supervision across heterogeneous equipment, including bioreactors and CIP systems, while meeting industrial real-time and robustness requirements [

6]. Complementary contributions in bioprocess monitoring and control have proposed advanced observers, model predictive controllers and fault-detection schemes, but typically focus on algorithmic performance rather than on how human operators interact with increasingly complex automation stacks in day-to-day operation [

1].

In parallel, large language models (LLMs) and conversational agents have emerged as powerful tools for making complex data and models more accessible to domain experts, enabling natural-language querying, explanation and guidance [

7,

8]. Early studies in industrial settings indicate that LLM-based assistants can help operators explore process histories, retrieve relevant documentation and reason about abnormal situations using free-form queries [

8]. However, integrating LLMs into safety-critical environments remains challenging: LLM outputs are non-deterministic, may hallucinate and must coexist with hard safety constraints, deterministic interlocks and real-time requirements [

7,

8]. Existing architectures rarely combine deterministic rule-based supervision, continuous analytics and LLM-based conversational interfaces in a way that preserves safety while providing meaningful assistance for CIP operations and other multi-stage cleaning or batch processes.

1.1. From Reactive Alarms to Diagnostic Intelligence

Modern food and beverage facilities equipped with advanced control strategies— including model-based flow optimisation and automated parameter regulation— have achieved significant process stability. In such environments, catastrophic process failures are rare, and traditional alarm systems designed to detect imminent faults often generate excessive nuisance alerts that operators learn to ignore or dismiss [

9]. The supervisory challenge has consequently evolved from

detecting failures to

interpreting operational signals: distinguishing between acceptable process variability and subtle patterns indicating emerging maintenance needs before they impact production [

10,

11].

Consider a CIP execution where flow rates are 10% below optimal but still within regulatory acceptance bounds. A traditional threshold-based alarm system remains silent, yet this pattern—if consistent across multiple cycles—may signal gradual pump wear requiring scheduled maintenance. Similarly, slight temperature deviations that do not compromise product safety may indicate boiler efficiency degradation, and conductivity variations within specification may reflect dosing pump calibration drift. In all cases, individual executions complete successfully by specification, but

trend analysis across execution cycles reveals actionable maintenance opportunities that can prevent unplanned downtime and extend equipment lifespan [

11].

Extracting these diagnostic insights currently depends on expert operator knowledge and time-intensive manual log analysis—a process that scales poorly as facilities expand and product portfolios diversify. Moreover, the high dimensionality of sensor data (dozens of variables sampled at sub-second intervals) makes it difficult for operators to recognise subtle patterns amid normal process variability [

9].

In well-optimised plants where CIP executions routinely meet specifications, failures are rare but emerging equipment degradation must be identified through longitudinal trend analysis rather than catastrophic fault detection. A system that monitors 100 consecutive successful CIP runs provides no evidence of diagnostic capability; conversely, analysing executions that span the operational spectrum—from nominal baseline to preventive warning patterns to diagnostic alert regimes—demonstrates the architecture’s ability to distinguish acceptable process variability from systematic equipment drift requiring maintenance intervention before operational impact occurs.

1.2. Proposed Architecture and Evaluation Approach

This paper proposes a generic, process-agnostic multi-agent architecture for AI-assisted monitoring and decision support in industrial batch processes. The architecture is instantiated and evaluated following a case-study design in the Clean-in-Place (CIP) system of an industrial beverage plant, aimed at demonstrating architectural feasibility and diagnostic capabilities under realistic operating conditions rather than statistical generalization across populations of plants. While tailored here to CIP, the architectural components—process-aware context management, hybrid deterministic/LLM supervision, and incremental agent deployment—transfer to other multi-stage batch operations (fermentation, distillation, pasteurisation) by reconfiguring process-specific rules and ontologies [

6,

12].

Unlike existing LLM-based assistants that typically operate as generic chatbots over manuals, historical databases or SCADA tags, the proposed architecture treats CIP executions as first-class contexts. A set of CIP-aware agents load their context on demand according to the active programme and stage, subscribe to enriched data streams and produce supervisory states, alerts and explanations that are aligned with the lifecycle of real CIP runs. This process-centric view of context enables new decision-support agents (LLM-based or otherwise) to be added incrementally, without modifying the underlying CIP programmes. This process-centric abstraction—treating batch executions as first-class contexts—constitutes the main architectural innovation, enabling heterogeneous AI components to operate over a shared process lifecycle without coupling to specific control logic.

The architecture is instantiated and evaluated on real CIP cycles executed in an industrial beverage plant over a six-month deployment period. From 24 complete executions monitored during this period, three representative cases are purposively selected to provide architectural and operational validation evidence across the diagnostic spectrum observed during deployment: (i) a nominal baseline execution demonstrating routine equipment health, (ii) a preventive-warning case exhibiting subtle operational signals (flow reduction, temperature drift) that do not violate safety thresholds but indicate emerging equipment degradation requiring scheduled maintenance, and (iii) a diagnostic-alert regime capturing multiple concurrent deviations (pump wear, boiler efficiency loss, dosing drift) requiring prioritised maintenance review.

Rather than pursuing large-scale statistical generalisation—which would be infeasible given the operational frequency of CIP cycles (1–3 executions per day) and the stable baseline achieved through prior control optimisation—this case-study evaluation demonstrates how the decision-support layer interprets operational signals, issues contextualised alerts, and generates natural-language diagnostic summaries that inform preventive maintenance decisions, while preserving the determinism required for safety-critical alarm handling. The focus is on proving architectural feasibility and showing that the diagnostic patterns identified by the system align with maintenance needs confirmed by plant operators and maintenance logs.

1.3. Contributions

The main contributions of this paper are:

A batch-process-aware, multi-agent decision-support architecture that treats batch executions (such as CIP cycles) as first-class contexts. Agents load their context on demand according to the active programme and stage, subscribe to enriched data streams and produce supervisory states, alerts and explanations aligned with the lifecycle of real batch runs.

A process-centric context management approach that allows heterogeneous AI components (rule-based agents, fuzzy logic, neural networks, LLM-based assistants) to be added incrementally. New agents can reuse the same process context and message bus without modifying the underlying control programmes or restarting the supervision layer.

A set of process-level evaluation metrics that quantify the behaviour of the decision-support layer over real executions, including compliance with stage specifications, consistency with state specifications, and stability of state labelling, complemented by spot checks of the numerical consistency between language-based summaries and enriched logs.

An experimental study on three complete CIP runs that instantiates the architecture in a real cleaning-in-place application, demonstrating its ability to maintain high specification compliance across nominal, preventive and diagnostic scenarios, provide coherent and stable supervisory states, and generate data-grounded natural-language explanations in real time without altering the existing CIP control logic. The case studies collectively illustrate how diagnostic interpretation of alert patterns across execution cycles can inform preventive maintenance scheduling—addressing pump wear, boiler degradation and dosing system calibration—before operational impact occurs.

Collectively, these contributions advance the state of knowledge by demonstrating— through a real industrial deployment—that hybrid deterministic/LLM architectures can be integrated into safety-critical batch supervision to support maintenance-oriented decision-making, and by providing a reproducible architectural pattern and evaluation methodology that can guide future implementations in other batch process domains.

The architecture has been implemented and deployed in a real industrial environment, supporting CIP operations at the VivaWild Beverages plant over a six-month validation period, which provides the basis for the experimental evaluation reported in this paper.

1.4. Paper Organisation

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows. Section 2 reviews related work on bioprocess monitoring, Industry 4.0 architectures, LLMs in industrial settings, and task planning. Section 3 presents the generic batch process supervision architecture, including the rationale for a layered, agent-based design and the process-agnostic instantiation pattern. Section 4 details real-time data management and LLM integration strategies. Section 5 describes the experimental methodology, including the industrial deployment, selection rationale for representative execution cases, data collection procedures and evaluation metrics. Section 6 presents results from three representative CIP executions, quantifying compliance, state consistency, stability and LLM fidelity. Section 7 discusses the findings, positions the work relative to existing approaches, addresses limitations and outlines directions for future longitudinal analysis. Section 8 concludes the paper.

2. Related Work

2.1. Bioprocess and CIP Monitoring and Control

Monitoring and control of industrial bioprocesses has been extensively studied, with a strong emphasis on state estimation, soft sensors, fault detection and advanced control strategies such as model predictive control [

1]. Recent advances in soft sensor modeling have explored multiple paradigms: interval type-2 fuzzy logic systems for uncertainty handling [

13], deep learning approaches for feature representation in high-dimensional data [

14], fuzzy hierarchical architectures that combine rule-based reasoning with adaptive learning for improved interpretability [

15], and deep neural network-based virtual sensors for retrofitting industrial machinery without additional physical instrumentation [

16]. Within this broader context, cleaning-in-place (CIP) systems are recognised as critical operations that ensure hygienic conditions and prevent cross-contamination between batches [

2], but also as major contributors to water, chemical and energy consumption [

4].

Reported approaches for CIP focus mainly on sequence design, parameter optimisation and endpoint detection, including improved scheduling of cleaning cycles, optimisation of temperature and flow profiles, and rule-based supervision to guarantee that each stage meets predefined set-points [

2,

3,

4]. In most cases, the supervisory logic is implemented directly in PLCs and SCADA systems, with alarm rules defined as static thresholds or simple logical combinations, providing limited support for richer situation awareness, multi-variable diagnostics, cross-cycle trend analysis or operator guidance for preventive maintenance beyond trends and alarm lists in production environments.

While these approaches successfully detect threshold violations and ensure regulatory compliance, they typically operate on a per-execution basis and do not explicitly support the interpretation of subtle operational signals that may indicate emerging equipment degradation (for example, gradual pump wear, boiler efficiency drift or dosing system calibration errors) before they impact process outcomes. Recent soft sensor frameworks have demonstrated improved handling of uncertainty [

13], nonlinear pattern recognition [

14], and rule-based feature processing with fuzzy reasoning [

15], yet their integration with conversational interfaces for maintenance-oriented decision support remains unexplored. The supervisory challenge has consequently shifted from detecting imminent failures to identifying preventive maintenance opportunities through longitudinal trend analysis and diagnostic pattern recognition across multiple CIP cycles.

2.2. Industry 4.0 Architectures and Microservice-Based Automation

The move towards Industry 4.0 has motivated a variety of reference architectures and frameworks that aim to increase modularity, interoperability and scalability in industrial automation [

5]. These frameworks typically distinguish between physical assets, edge computing resources and higher-level information systems, and promote the use of standard communication protocols and service-oriented designs as enablers of flexible, connected production environments [

17]. Building on these ideas, previous work has proposed component-based microservice frameworks for bioprocess automation, in which control, monitoring, HMI, data logging and higher-level coordination are implemented as independent, containerised components interconnected through a message bus [

6,

12]. These frameworks have demonstrated how microservices can satisfy real-time and robustness requirements in bioprocess applications while supporting flexible reconfiguration and reuse across equipment such as bioreactors and CIP units. Other approaches have explored multi-agent reinforcement learning for optimizing manufacturing system yields through coordinated agent contributions [

18], demonstrating the value of distributed intelligence in complex production environments. However, these and other microservice-oriented approaches largely focus on structural and communication concerns; they do not detail how hybrid deterministic and LLM-based agents can be embedded into the automation stack to support real-time supervision, diagnostic interpretation and preventive maintenance decision-making for concrete operations such as CIP.

The present paper retains a microservice-style architecture but shifts the focus from structural aspects to decision support, diagnostic interpretation and explanation: the agents, reasoning layer and conversational interface are implemented as loosely coupled services that subscribe to enriched data streams and publish supervisory states, diagnostic alerts, maintenance-oriented reports and trend analyses. The evaluation presented here therefore complements prior architectural studies by quantifying how such a service-based, multi-agent layer behaves when deployed over real CIP executions, and by demonstrating its ability to differentiate nominal equipment health, preventive warning patterns and diagnostic alert regimes that are meaningful for maintenance planning.

2.3. LLMs and Conversational Assistants in Industrial and CPS Settings

The emergence of large language models (LLMs) has motivated a growing body of work on industrial and cyber-physical applications. Recent surveys discuss cross-sector industrial use cases of LLMs, including maintenance support, incident analysis and internal knowledge management, and highlight both opportunities and risks in terms of robustness and governance.[

19,

20,

21] Several authors propose architectures where on-premise LLMs are integrated with IoT and cyber-physical systems in Industry 4.0, typically acting as a semantic layer or conversational front-end for heterogeneous data sources.[

22,

23,

24,

25]

Lim et al. propose frameworks in which LLMs are embedded into industrial automation systems as intelligent orchestration components, enabling multi-agent coordination, natural-language task interpretation and adaptive manufacturing execution [

26]. These contributions demonstrate a clear interest in bringing LLMs closer to operational technology, but most remain at the level of high-level frameworks or generic use cases rather than detailed, domain-specific instantiations that operate continuously on live process data, track equipment health trends across multiple execution cycles and interact directly with plant operators for maintenance-oriented decision-making.

Existing work on LLM-based assistants for industrial systems largely focuses on providing conversational access to documentation, historical data or SCADA/IoT tags in real time, often evaluating performance in terms of question answering precision and response generation [

27]. Recent applications have demonstrated how LLMs can facilitate natural language queries over complex manufacturing process data and real-time sensor streams, enabling production personnel to interact with high-dimensional datasets without requiring specialized analytical expertise [

28]. Retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) approaches in industrial settings have shown significant improvements in domain-specific knowledge retrieval, achieving recall rates above 85% for technical service and regulatory documentation [

29]. Complementary work on multimodal LLM-based fault detection has shown how GPT-4-based frameworks can improve scalability and generalizability across diverse fault scenarios in Industry 4.0 settings [

30], though these approaches primarily target fault classification rather than continuous process supervision and preventive maintenance planning. However, existing LLM-based approaches for manufacturing data exploration typically focus on real-time visualization and anomaly detection in continuous production environments [

28], rather than providing lifecycle-aligned supervision for multi-stage batch processes with preventive maintenance decision support. In contrast, this work targets a concrete batch process (CIP) and evaluates a decision-support architecture that integrates rule-based supervision, enriched data streams and language-based interaction within a process-centric context aligned with the lifecycle of CIP executions.

2.4. LLMs for Robotics, Task Planning and Control Logic

A substantial portion of applied LLM research in industry-related domains comes from robotics and task planning. Concrete implementations show LLM-based task and motion planning for construction robots, [

31] as well as frameworks such as DELTA that decompose long-term robot tasks into sub-problems and translate them into formal planning languages [

32]. Recent work on embodied intelligence in manufacturing has demonstrated how LLM agents such as GPT-4 can autonomously design tool paths and execute manufacturing tasks, achieving success rates above 80% in industrial robotics simulations [

33], while parallel work on LLM-based mobile robot navigation has shown that models such as Llama 3.1 can dynamically generate collision-free waypoints in response to natural language commands and environmental obstacles [

34]. Complementary work on LLM-based digital intelligent assistants in assembly manufacturing has demonstrated significant improvements in operator performance, user experience, and cognitive load reduction [

35].

Recent work on human-centric smart manufacturing has shown how LLM-based conversational interfaces can lower the digital literacy barrier for operators by enabling natural-language access to real-time machine data, as demonstrated by the ChatCNC framework for CNC monitoring [

36]. Complementarily, Xia et al. propose an LLM-driven industrial automation framework where multi-agent structures, structured prompting, and event-driven information models enable end-to-end control, from interpreting real-time events to generating production plans and issuing control commands [

37]. These works focus primarily on code generation, configuration, and verification of control logic

prior to deployment, rather than on continuous supervision, diagnostic interpretation, and operator support

during runtime. Critically, none of these contributions address the integration of LLM-based analytics with deterministic supervisory logic for preventive maintenance planning through cross-cycle trend analysis and equipment health monitoring—the focus of the present work.

2.5. Positioning of the Present Work

Overall, existing literature shows intense activity around LLMs for documentation retrieval, maintenance support, robotics and control-code generation in industrial and CPS environments. However, there is a noticeable gap regarding batch processes and safety-critical cleaning operations such as CIP, particularly in terms of architectures that combine deterministic supervision with LLM-based diagnostic interpretation to support preventive maintenance decision-making. To the best of our knowledge, no prior work reports an architecture that simultaneously: (i) integrates deterministic agents for state estimation and safety monitoring with LLM-based analytics operating over live process buffers; (ii) supports cross-cycle trend analysis for preventive maintenance through enriched data streams; (iii) combines structured process rules with LLM reasoning to ensure process adherence while minimizing hallucinations [

38]; and (iv) quantitatively evaluates the system’s ability to differentiate nominal equipment health, preventive warning patterns and diagnostic alert regimes across real industrial executions.

The present work addresses this gap by proposing, implementing and evaluating such an architecture in a real CIP deployment, showing that it is feasible to combine rule-based supervision and language-based assistance in safety-critical batch processes while maintaining coherent supervisory states, data-grounded explanations and actionable diagnostic patterns that support preventive maintenance planning and equipment health monitoring. The case-study evaluation demonstrates that the architecture can distinguish between nominal baseline operation, preventive maintenance signals and diagnostic alert conditions, providing operators with contextualised, maintenance-oriented decision support that goes beyond traditional threshold-based alarm systems.

3. Generic Batch Process Supervision Architecture

The proposed system provides a generic, layered architecture for AI-assisted supervision and diagnostic interpretation of industrial batch processes. While the architecture is instantiated and evaluated here in the context of Clean-in-Place (CIP) operations in a beverage plant, its design is process-agnostic: the same pattern applies to fermentation, distillation, pasteurisation, chemical synthesis and other multi-stage batch procedures by reconfiguring process-specific rules, ontologies and enrichment logic. The architecture spans from operator-facing interfaces down to physical process equipment, with intermediate layers that handle orchestration, agent coordination, diagnostic pattern recognition for equipment health monitoring, and shared data management.

At its core, an event bus exposes a global data space where agents, user interfaces and the control layer exchange events and enriched data streams, while an intermediate orchestration layer routes operator requests to specialised agents according to user intention and process context.[

6,

17]

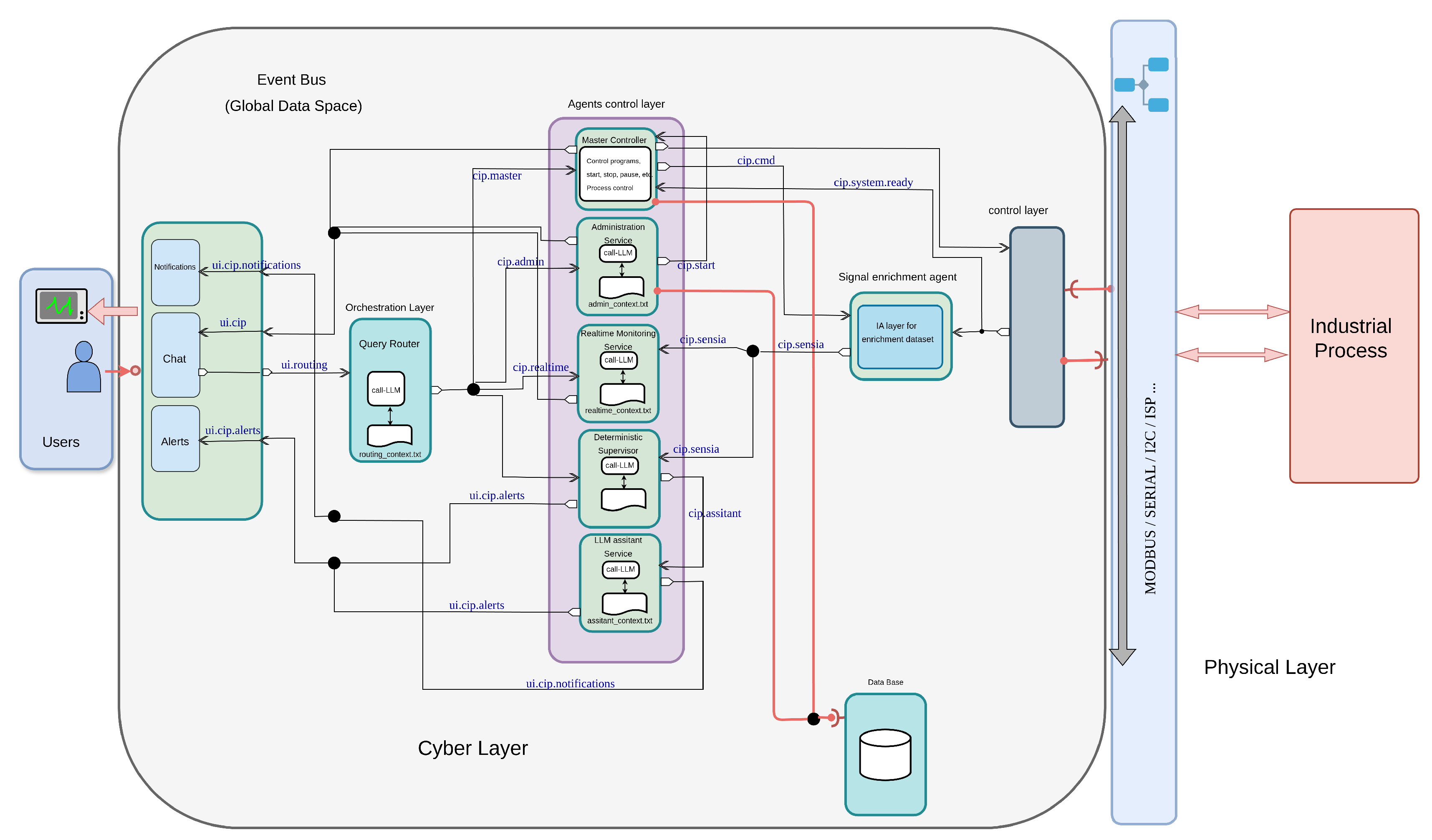

Figure 1 illustrates the main layers: (i) the operator interaction layer, (ii) the orchestration and intent-routing layer, (iii) the agent layer (control, configuration and analysis), (iv) the data and event hub, and (v) the physical execution layer.

A key advantage of adopting an orchestrator-based, service-oriented architecture is that new decision-support agents can be added incrementally, without modifying the underlying batch programmes or restarting the supervision layer. Each agent subscribes to the same enriched data streams and loads its context according to the active batch execution and stage, producing additional supervisory states, diagnostics, preventive maintenance recommendations or trend analyses. This design makes it possible to combine heterogeneous AI techniques (for example, rule-based agents, fuzzy logic, neural networks, LLM-based assistants) within a common framework, and to evolve the decision-support and diagnostic capabilities over time as new agents are deployed [

5,

6].

In this sense, the architecture does not assume a single monolithic AI component, but rather a distributed set of process-aware agents coordinated by an orchestrator. The evaluation presented in this work focuses on one such configuration, where rule-based supervision and a language model assistant share the same batch context for CIP operations; however, the same pattern can be used to integrate further agents (for example, predictive models or optimisation modules) without disrupting existing services or batch control programmes [

6,

12]. In the deployed configuration, operators interact through a web interface that sends normalised events to a query router, which dispatches them to a set of process-aware agents—all connected through the shared event bus and enrichment layer.

The proposed decision-support layer has been implemented as a set of microservices and agents deployed alongside an existing automation system at an industrial plant. The agents subscribe to the plant’s real-time data streams and batch execution events, and publish supervisory states, diagnostic alerts, preventive maintenance recommendations and reports to the same infrastructure used in day-to-day operation. The evaluation in Section 6 is based on logs collected from this deployment during normal production runs, demonstrating the architecture’s ability to differentiate nominal, preventive and diagnostic operational regimes.

3.1. Process-Agnostic Design and Instantiation Examples

Table 1 illustrates how the same architectural components map to different batch process types, with process-specific parameters configured at deployment. The CIP case study discussed in this paper corresponds to the first instantiation column; analogous deployments for fermentation or distillation would reuse the same components with different recipes, variables and rules.

This abstraction enables the same codebase and agent logic to supervise multiple process types, with only rules, ontologies and variable mappings reconfigured per application. The CIP evaluation in

Section 6 demonstrates this pattern in production; fermentation and distillation deployments would follow the same architecture with domain-specific enrichment and diagnostic rules.

3.2. Rationale for a Layered, Agent-Based Design

Instead of deploying a single, monolithic large language model (LLM) with access to all plant data and control interfaces, the proposed architecture adopts a layered, agent-based design. This choice is motivated by several considerations:

Context management and efficiency: Industrial environments produce high-volume, heterogeneous data across multiple batch lines and equipment. Concentrating all information into a single LLM context would be inefficient and difficult to control. By separating operator interaction, orchestration and specialised agents, each component only handles the subset of data and functions relevant to its role, enabling smaller, faster contexts and more predictable behaviour [

37].

Safety and decentralisation of intelligence: Safety-critical logic (e.g., interlocks, sequence enforcement, hard alarms) remains in deterministic agents and PLC/SCADA systems, while LLM-based components are confined to explanatory and analytical roles. This decentralisation avoids granting a single LLM direct authority over control actions and supports explicit validation paths for any recommendation before it affects the process.

Flexibility and evolution: Food, beverage and chemical plants often operate under maquila-like conditions, with frequent product changes, contract manufacturing and evolving cleaning or processing requirements. A layered architecture with loosely coupled agents and a generic data hub allows new analysis functions, additional lines or updated recipes to be introduced without redesigning the entire system, supporting continuous adaptation and incremental deployment [

6,

17].

Scalability across services and sites: As production scales to multiple lines, services or sites, the same pattern can be replicated: interaction and orchestration remain similar, while additional agent instances are deployed per line or plant. This aligns with microservice and Industry 4.0 principles, enabling horizontal scale-out and reuse of components across different customers and service contracts [

5,

6].

In summary, the layered architecture decentralises intelligence across specialised agents optimised for specific intentions (control, configuration, deterministic supervision, real-time analytics and offline analysis), reduces the need for large, global LLM contexts, and preserves safety and scalability in settings where processes, products and cleaning or conversion requirements evolve continuously.

3.3. Process-Aware Context Management

The decision-support layer is implemented as a set of loosely coupled agents coordinated by an orchestrator. Each agent is process-aware: upon receiving a request or detecting a new batch execution (for example, a CIP cycle, fermentation batch or distillation run), it loads the corresponding context (programme, equipment configuration, current stage, enriched variables and rule-based specifications) and subscribes to the relevant data streams. Within this context, the agent produces supervisory states, notifications, reports or language-based explanations that are specific to the active batch run.

In the CIP deployment, the context includes cleaning circuit, tank, programme, stage and key variables such as temperature, flow and conductivity. In a fermentation deployment, it would instead comprise vessel, recipe, inoculum, growth phase and variables such as pH, dissolved oxygen and biomass proxies. In distillation, it would include column configuration, feed composition and reflux schedule. This process-centric abstraction enables agents to be added or updated incrementally: new agents—whether based on rules, fuzzy logic, neural networks or large language models—can subscribe to the same process contexts and publish their outputs to the common message bus, without requiring changes to the underlying control logic or to other agents. In this sense, the architecture supports a distributed ecosystem of AI components that can evolve over time while sharing a consistent, process-centric view of the system.

3.4. Operator Interaction Layer

At the top, a web-based operator interface provides multiple interaction modalities: natural-language chat, structured alarm panels and visual summaries of process status. Operators can ask questions in free text (e.g., about current batch progress, recent anomalies or historical comparisons), request specific functions (e.g., remaining time for a stage, list of active batch executions) or issue management actions (e.g., creating or starting batch requests). The interface normalises these inputs and forwards them to the orchestration layer as high-level events containing the user query, role and context.

The same interaction layer can be used across different process types by exposing a unified vocabulary (e.g., “current batch”, “last stage”, “previous run”) that is resolved internally to process-specific concepts (CIP cycle, fermentation batch, distillation campaign). This abstraction reduces training effort for operators who work across multiple units or services.

3.5. Orchestration and Intent-Routing Layer

The orchestration layer acts as a mediator between user intents and the underlying agents. It receives normalised requests from the interaction layer and classifies them into intent categories such as: control (start/stop batch, interact with the master process), configuration (programmes, equipment, permissions), deterministic analysis (current state, diagnostics, time estimates), real-time free analysis (ad hoc queries over the live buffer) and offline analysis (post-run reports over stored data).Based on this intent and the user role, the orchestrator dispatches the request to the appropriate agent via the data and event hub, and later aggregates or reformats the response into a coherent message for the operator interface.

3.6. Agent Layer: Control, Configuration and Analysis

Below the orchestrator, a set of specialised agents implement the core system functions. These agents are defined generically for batch processes, with process-specific parameters configured at deployment:

Batch Master Controller: coordinates the execution of batch cycles at the physical layer, interacting with PLCs or SCADA to start, stop or pause programmes on specific equipment. In the CIP deployment, this agent manages cleaning circuits and stages; in fermentation, it would orchestrate inoculation, feeding and harvesting phases.

Administration Service: manages configuration and governance, including batch recipes (programmes), equipment definitions, resource states and role-based permissions. It exposes CRUD-style operations and workflow support for batch execution requests, ensuring that only authorised actions are propagated and that equipment availability constraints are respected. The same service structure applies to CIP circuits, fermentation vessels or distillation columns.

Deterministic Supervisor: performs deterministic, rule-based supervision and diagnostics in real time. It consumes pre-processed sensor streams, maintains sliding windows of recent data and periodically computes state summaries, diagnostics and hard safety alerts (NORMAL/WARNING/CRITICAL), which are published as structured notifications and alarms for the operator interface. Rules and thresholds are defined per process type (for example, temperature and flow envelopes for CIP stages, or pH and dissolved oxygen bounds for fermentation phases).

Realtime Monitoring Service: focuses on flexible, operator-driven analysis over the live process buffer. It maintains a rolling data-frame representation of the active batch trajectory and answers ad hoc queries using deterministic computations and an LLM-backed analytics layer. In the deployed configuration, the LLM component uses Qwen 2.5 (7 billion parameters) running locally via Ollama on NVIDIA GPU infrastructure, providing sub-second inference times for diagnostic queries while maintaining data sovereignty and avoiding cloud dependencies This enables correlations, aggregate statistics and narrative explanations during the run without introducing external API latency or compliance concerns. The same agent structure applies to any batch process with time-series sensor data.

Offline Analysis Service: operates on persisted historical data after batch completion, generating post-run reports, comparative analyses across cycles and higher-level insights that are not subject to strict real-time constraints. Its outputs can be requested by operators via the same orchestrated interface, but are computed over archived time-series rather than the live buffer.

This agent layer separates safety-critical control and supervision from exploratory analytics: the master and deterministic agents enforce strict rules and temporal constraints, while the real-time and offline analysis agents provide more flexible, LLM-enhanced insights without affecting core control logic.[

37]

3.7. Data and Event Hub

The data and event hub underpins communication between all agents and the physical layer. In the deployed system, this hub is implemented using Redis (version 7.2), which provides:

publish/subscribe channels (via SUBSCRIBE/PUBLISH commands) for real-time events and sensor data (for example, batch start/stop, stage transitions, time-stamped readings);

Redis Streams (XADD/XREAD) for time-series storage of per-batch trajectories of key variables, enabling efficient temporal queries; and

hash structures (HSET/HGET) for configuration (recipes, equipment), resource status and the state of batch execution requests.

In the CIP deployment, these structures store cleaning circuits, programmes and sensor readings (temperature, flow, conductivity). In fermentation, they would store vessels, recipes and process variables (pH, dissolved oxygen, biomass proxies); in distillation, they would track columns, feed schedules and reflux ratios. The hub interface remains identical across process types, decoupling producers (PLCs, sensors) from consumers (agents, UI), supporting multiple concurrent batch processes, and allowing analytical and diagnostic capabilities to be extended without changes to the underlying control hardware.

4. Real-Time Data Management and LLM Integration

The proposed architecture explicitly balances memory usage, query latency and quality of assistance by combining compact, enriched data buffers with decentralised analysis agents that support both immediate supervisory decisions and longitudinal trend analysis for preventive maintenance.

4.1. Bounded In-Memory Buffers and Latency

Each active CIP instance maintains an in-memory buffer with a fixed maximum number of records, corresponding to a few hours of operation at the given sampling rate, instead of persisting the entire plant history in the LLM context. This rolling dataset is exposed through multiple logical windows: a short horizon (e.g., last 2 minutes) for real-time state estimation, a medium horizon (e.g., last 5–10 minutes) for periodic diagnostics and preventive warning detection, and a full-cycle view for exploratory real-time queries, cross-cycle trend analysis and offline post-run analysis. By keeping buffer size bounded, deterministic statistics and LLM prompts can be computed with near-constant time and memory, even as the plant scales to more CIP circuits or higher sampling frequencies.

4.2. Enriched, Decentralised Data Views

Incoming sensor records are enriched in real time with additional attributes such as CIP program and stage labels, elapsed and remaining time, progression percentage, fuzzy quality indices and short textual descriptors of detected issues, recommended actions and maintenance implications. These enriched records are partitioned per CIP instance and per agent, so that each agent only receives the subset of variables needed for its function (e.g., deterministic supervision windows for immediate alerts, real-time analytics buffers for diagnostic interpretation, offline archives for longitudinal trend correlation with maintenance records), avoiding a single centralised, monolithic dataset. This decentralisation reduces contention and enables real-time support for diagnostics, preventive warning generation and maintenance-oriented decisions at the agent level, while still allowing higher-level aggregation when required for cross-cycle trend analysis.

4.3. Compact LLM Contexts and Efficient Queries

To avoid high latency and cost, the LLM never receives raw, unfiltered streams; instead, the real-time analytics agent constructs compact prompts that combine aggregate statistics over the relevant window, a small set of representative samples (e.g., most recent records or identified outliers) and contextual metadata such as program, stage, circuit and recent alert patterns. This strategy keeps context size small and stable while preserving the information required for meaningful explanations, diagnostic pattern recognition and preventive maintenance recommendations, making it feasible to answer natural-language queries with response times compatible with operator workflows in real plants. The integration layer treats the LLM as a pluggable component accessed through a uniform API, so different on-premise or cloud models can be used without changing the surrounding data management strategy.

4.4. Lowering the Expertise Barrier for Real-Time Decisions and Maintenance Planning

Because diagnostic windows and enriched attributes are computed deterministically and exposed in structured form, operators receive interpretable summaries (e.g., state class, quality grade, main issues, suggested actions and maintenance implications) without having to interpret raw trends or write complex analytical queries.The LLM layer then builds on these structured diagnostics to provide natural-language explanations, cross-cycle trend comparisons and preventive maintenance recommendations, allowing less specialised staff to understand CIP performance, identify emerging equipment degradation patterns and take timely decisions without requiring deep training in control theory, statistical analysis or maintenance planning. This combination of bounded, enriched buffers and layered LLM integration directly supports real-time analysis, diagnostic interpretation and maintenance-oriented decision support in complex industrial environments, while keeping computational and training costs under control.

4.5. Illustrative Data Views and Query Profiles

Table 2 summarises the main data windows maintained per CIP instance and their intended use, while

Table 3 illustrates typical query types, underlying sources and expected response times.

4.6. Fuzzy Enrichment of Real-Time CIP Data

Raw CIP sensor readings alone (e.g., temperature, flow, conductivity, volume) are often difficult to interpret directly in the control room, especially when multiple variables must be considered simultaneously or when subtle degradation patterns must be distinguished from normal process variability. To provide operators and downstream agents with more actionable information, the system applies a fuzzy evaluation layer in real time, which maps continuous variables and their deviations from nominal profiles into linguistic assessments, quality indices and maintenance-oriented diagnostic labels.

For each time-stamped record, the enrichment pipeline:

normalises the raw measurements with respect to the target CIP program and current stage (e.g., expected temperature, flow and conductivity ranges for an alkaline wash);

evaluates a set of fuzzy rules that capture expert knowledge, such as “temperature slightly low but within tolerance” or “flow persistently below minimum, suggesting pump wear”, combining multiple variables and short-term trends; and

outputs a discrete state label (e.g., NORMAL, WARNING, CRITICAL), a continuous quality grade in , and short textual descriptors summarising the main issues, recommended actions and maintenance implications.

The resulting enriched record contains, in addition to the raw sensor values and timestamps, fields such as

stage,

progress_percent,

remaining_time,

state,

quality_grade,

motives and

actions, as well as equipment and circuit identifiers and auxiliary counters (e.g., number of recent warnings or critical samples).

Table 4 shows a simplified example of such a record.

From a resource perspective, the bounded-buffer design keeps the memory footprint per CIP instance relatively small: for example, a buffer of – records with a dozen numeric and categorical fields typically remains in the order of a few megabytes in memory, even when multiple CIP lines are monitored concurrently. This is modest compared to the memory requirements of the LLM itself and allows deterministic statistics and prompt construction to execute with predictable latency. At the same time, the enriched representation and pre-computed diagnostics provide enough information for operators to take online decisions directly from the generated summaries and explanations, including identification of preventive maintenance opportunities and equipment health trends, without resorting to external tools or manual data export.In practice, this combination of low in-memory cost and high decision support value—spanning immediate supervisory needs and longer-term diagnostic interpretation—is essential for deploying AI-assisted supervision in industrial environments where hardware resources and real-time constraints are non-negotiable.

4.7. Computational Resource Profile

Table 5 summarises the computational footprint of the main system components in the deployed configuration. The memory requirements per CIP instance remain modest (order of a few megabytes for the enriched buffer), while the LLM service (Qwen 2.5 7B via Ollama) operates as a shared resource across all active CIP lines, with inference latencies compatible with interactive operator workflows and real-time diagnostic queries.

Because the LLM runs locally on NVIDIA GPU infrastructure, query latencies remain predictable and do not depend on external cloud API availability or network conditions. This edge deployment strategy addresses the computational and energy constraints inherent in cloud-based LLM architectures for IIoT environments [

39], while maintaining data sovereignty and reducing communication overhead. Recent work on edge-cloud collaboration for LLM task offloading in industrial settings has demonstrated that local inference can reduce latency by 60–80% compared to cloud-based alternatives [

39], supporting the architectural decision to deploy Qwen 2.5:7B on dedicated GPU infrastructure rather than relying on external API services.

5. Evaluation Methodology

5.1. Evaluation Objectives

This study evaluates the architectural feasibility and operational capability of the proposed hybrid AI framework in a real industrial environment, rather than pursuing large-scale statistical validation of process performance improvements.

Accordingly, the evaluation focuses on how the decision-support layer behaves when exposed to authentic CIP executions, and whether it fulfils its intended role as a real-time, operator-oriented supervisory layer that supports diagnostic interpretation and preventive maintenance planning. The study addresses the following research questions:

RQ1: Can the architecture maintain coherent supervisory states across diverse CIP conditions?

RQ2: Do the agents respond within application-level real-time constraints during production operation?

RQ3: Does the LLM-based analytics layer provide grounded, numerically consistent explanations over enriched process data?

RQ4: Is the system deployable and operable in an actual CIP installation without disrupting existing PLC/SCADA programmes?

RQ5: Can the architecture differentiate nominal, preventive and diagnostic alert patterns in a way that is meaningful for maintenance decision-making?

The primary goal is thus to demonstrate that the architecture can be instantiated, operated and queried in a working plant, and that its supervisory outputs remain coherent, stable, data-grounded and diagnostically useful over complete CIP executions.

5.2. Case Selection Rationale

Rather than sampling a large number of nearly identical cycles, the evaluation adopts a case-study approach using three representative CIP executions drawn from ongoing production at the VivaWild Beverages plant. These executions were selected to span the typical operational envelope observed in day-to-day operation and to illustrate complementary diagnostic scenarios: (a) a fully nominal baseline, (b) executions with preventive warnings that do not compromise stage success, and (c) executions with more pronounced deviations that generate diagnostic alerts under operational stress.

Table 6.

Selected CIP executions and rationale.

Table 6.

Selected CIP executions and rationale.

| Case |

Type |

Rationale |

| CIP1 |

Nominal baseline |

Baseline behaviour under standard

operating conditions, with variables close to their nominal

profiles and no warnings or alerts. Serves as a reference

for normal equipment health and operator performance. |

| CIP2 |

Preventive warnings |

Typical process variations in

alkaline and rinsing stages (e.g., slightly reduced flow or

temperature excursions that remain within specification)

that trigger WARNING-level diagnostics. These runs

complete successfully but indicate emerging maintenance needs

(e.g., pump wear, boiler efficiency drift). |

| CIP3 |

Diagnostic alerts |

Presence of more pronounced deviations,

including clusters of alerts related to flow or conductivity,

used to stress-test alert generation and diagnostic

capabilities under more demanding conditions that remain

operationally successful but call for prioritized maintenance. |

These cases are representative of normal plant operation. The CIP process at VivaWild is governed by standard operating procedures, automated recipe management and regulatory constraints, and exhibits high repeatability across executions in terms of temperature, flow and conductivity profiles.

In optimised industrial plants, CIP failures are rare by design; most executions complete successfully within specifications. The diagnostic challenge is therefore not detecting catastrophic faults—which traditional threshold-based alarms handle effectively—but rather identifying subtle, longitudinal degradation patterns in executions that still meet regulatory specifications. For example, flow rates declining 2% per cycle over five consecutive executions due to gradual pump wear may generate no critical alarms (each execution remains above the minimum regulatory threshold), yet this pattern signals actionable maintenance opportunities that can prevent unplanned downtime.

From this perspective, analysing 100 consecutive nominally successful CIP runs would provide strong evidence of system stability and low false-alarm rates, but no evidence of diagnostic capability—it would merely confirm that the system does not fail when the process does not fail. Conversely, analysing a small number of carefully chosen executions spanning nominal baseline, preventive warning scenarios and diagnostic alert regimes provides meaningful evidence about the architecture’s ability to differentiate operational conditions that are relevant for maintenance decision-making, extract equipment health insights from executions that meet specifications, and distinguish acceptable process variability from systematic equipment drift requiring intervention before operational impact occurs. This case-study validation approach is appropriate for establishing architectural feasibility and diagnostic behaviour in real industrial conditions.

Importantly, the system is deployed continuously and monitors all CIP executions; the three cases are used for detailed analysis and illustration of the architecture’s diagnostic behaviour. In routine operation, the value of the system emerges from the accumulation and inspection of alert patterns across multiple cycles (e.g., repeated flow warnings indicating pump degradation, recurring temperature deviations suggesting boiler maintenance). Extending the present analysis to longitudinal trend quantification and correlation with maintenance records is left for future work.

The objective of this evaluation is therefore architectural and operational validation of the decision-support layer, not statistical inference about long-term process improvements across all historical CIP data.

5.3. Evaluation Setup

The evaluation concentrates on the behaviour of the multi-agent decision-support architecture on top of the existing PLC/SCADA control layer, which remains unchanged. For each of the selected CIP executions, the agents subscribe to the live data streams and CIP events, maintain their internal contexts, and produce supervisory states, alerts, diagnostics and language-based explanations as they would during routine plant operation.

The study examines whether the architecture:

tracks the progression of each CIP stage and maintains coherent discrete supervisory labels;

provides timely detection of out-of-spec situations at the supervisory level, and differentiates nominal operation from conditions that warrant preventive or more urgent maintenance; and

generates natural-language diagnostics and summaries that remain consistent with the enriched data seen by the agents and are usable for maintenance-oriented decision-making.

No changes are made to the underlying low-level controllers, so any deviations in stage-specification compliance reflect actual plant behaviour rather than experimental manipulation.

5.4. Datasets

The experiments use logs collected from complete CIP runs covering alkaline, sanitising and final rinse stages. Each second, the system records:

process variables such as instantaneous and windowed flow, temperature, conductivity, pH and accumulated volume;

stage-level information (CIP programme, circuit, tank, current stage and progression);

supervisory outputs, including discrete labels (NORMAL, WARNING, CRITICAL), fuzzy quality indices and structured reasons describing the current situation (e.g., parameters within range, low flow conditions, insufficient volume); and

selected responses from the LLM-based analytics agent, including numerical summaries and narrative explanations.

For each run, the enriched records thus combine raw sensor values with derived features such as moving averages, diagnostic counters (e.g., recent warnings or critical samples) and identifiers of the active CIP programme, circuit and tank. This representation allows the evaluation to relate the behaviour of the decision-support layer to concrete process trajectories and stage-level specifications, and to verify the numerical consistency of language-based outputs.

5.5. Evaluation Metrics

On top of these logs, the methodology defines a set of quantitative metrics that capture complementary aspects of the decision-support behaviour of the architecture. The metrics considered in this work cover:

stage-specification compliance (time spent within prescribed operating ranges);

consistency between supervisory labels and process conditions;

temporal stability of the labels; and

consistency between language-based explanations and the underlying enriched data.

Additional metrics such as alert sensitivity, specificity, reaction time and anticipation window are formally defined as part of the framework to support future, larger-scale evaluations. In the present case-study campaign, quantitative results focus on compliance, label consistency and stability, while sensitivity-related metrics are inspected qualitatively in the three selected executions.

5.5.1. Stage Specification Compliance

This metric quantifies to what extent each CIP stage operates within its predefined process specification (e.g., flow, temperature and pH ranges). It measures the proportion of time during which the relevant variables remain inside their acceptable bands, providing a stage-level quality indicator that is independent of the underlying controller implementation.

Let a stage

s be sampled at discrete time instants

, and let

denote the vector of monitored variables at time

t. For each stage, a specification function

returns 1 if all relevant variables lie within their prescribed ranges at time

t, and 0 otherwise. The stage specification compliance is then defined as

In the experiments, this metric is computed separately for alkaline, sanitising and final rinse stages for each of the three representative executions, and then discussed on a case-by-case basis to characterise how the decision-support layer behaves under nominal, variable and more demanding conditions.

5.5.2. Alert Sensitivity and Specificity

This metric assesses how accurately the architecture detects out-of-spec situations by comparing generated alerts against process conditions derived from the logged variables, in terms of sensitivity (recall) and specificity.

Let each time instant t within a stage be associated with: (i) a binary ground-truth anomaly label , obtained by applying stage-specific rules to the process variables (e.g., low flow, out-of-range temperature or pH); and (ii) a binary alert decision , where if the architecture issues a WARNING or CRITICAL label and otherwise.

Over a set of time instants

, the sensitivity and specificity are defined as

where

denotes the indicator function.

1 These metrics are included to define a complete evaluation framework, but their systematic quantification is left to future work once larger cohorts of CIP executions and annotated events become available.

5.5.3. Reaction Time to Anomalies

This metric quantifies how quickly the architecture reacts once a process variable crosses an out-of-spec threshold, by measuring the delay between the onset of an anomaly and the first alert (WARNING or CRITICAL) raised by the system.

Let each anomaly episode k be characterised by: (i) an onset time , when a ground-truth condition becomes true (e.g., flow drops below a minimum threshold and remains there); and (ii) an alert time , corresponding to the first instant for which .

The reaction time for episode

k is defined as

Over a set of episodes

, the average reaction time can be computed as

In the present study, reaction times are inspected qualitatively for the selected cases; a systematic computation across larger datasets is left for future work.

5.5.4. Anticipation Window

This metric evaluates how early the architecture warns about conditions that may compromise the success of a CIP stage, such as insufficient final rinse volume or prolonged low-flow operation. It is defined as the time margin between the first relevant alert and the occurrence of a stage-level failure or constraint violation.

For each stage-level failure event j, let: (i) denote the time at which the failure or constraint violation is detected (e.g., the stage ends without meeting minimum volume or quality criteria); and (ii) denote the earliest time at which the architecture issues a WARNING or CRITICAL alert related to that failure mode.

The anticipation window for event

j is defined as

Over a set of failure events

, the average anticipation window can be expressed as

As with reaction time, this metric is defined to complete the evaluation framework, but its systematic quantification is outside the scope of the present case-study campaign.

5.5.5. State–Specification Consistency

While stage specification compliance focuses on whether the process variables remain within their target ranges, a complementary aspect is whether the discrete supervisory labels (NORMAL, WARNING, CRITICAL) are coherent with those ranges. Intuitively, the architecture should report NORMAL when all monitored variables are within specification, and should only escalate to WARNING or CRITICAL when at least one relevant variable leaves its acceptable band.

Let

s be a CIP stage sampled at times

, and let

and

be defined as above, with

indicating that all variables are within specification and

otherwise. Let

denote the discrete label produced by the supervisory layer at time

t. A sample is considered

label–consistent if

Defining the indicator

the state–specification consistency for stage

s over a run is given by

Values close to 1 indicate that the discrete supervisory state almost always matches the underlying process conditions, whereas lower values reveal mismatches between labels and actual operation. In the experiments, this metric is computed per stage and per execution, and then analysed qualitatively across the three cases.

5.5.6. Stability of State Labelling

In addition to being semantically coherent, the supervisory labels should exhibit a reasonable degree of temporal stability. Excessive oscillations between NORMAL, WARNING and CRITICAL states, especially in the absence of large changes in the process variables, can overload operators and reduce trust in the system.

For each stage

s, let

denote the sequence of discrete labels along the execution, and let

be the number of state changes within that sequence, i.e.,

where

is the indicator function. Let

be the duration of the stage in minutes. The stability of state labelling for stage

s is then quantified as

Low values of indicate stable supervisory behaviour (few label transitions per minute), whereas high values highlight stages where the decision layer oscillates frequently between states, signalling either genuinely unstable conditions or overly sensitive thresholds in the supervision logic. In the evaluation, this metric is interpreted in conjunction with the underlying process trajectories for each case.

5.5.7. Consistency of Language-Based Outputs

To assess whether the language-based explanations remain faithful to the underlying enriched data, the evaluation performs spot checks of numerical summaries and counts reported by the conversational interface. For selected responses, the averages and counts stated in the explanation are compared against the statistics computed directly from the corresponding windows of enriched records. This provides qualitative evidence of data-grounded behaviour and helps identify potential hallucinations or inconsistencies in the LLM layer.

5.6. Experimental CIP Runs

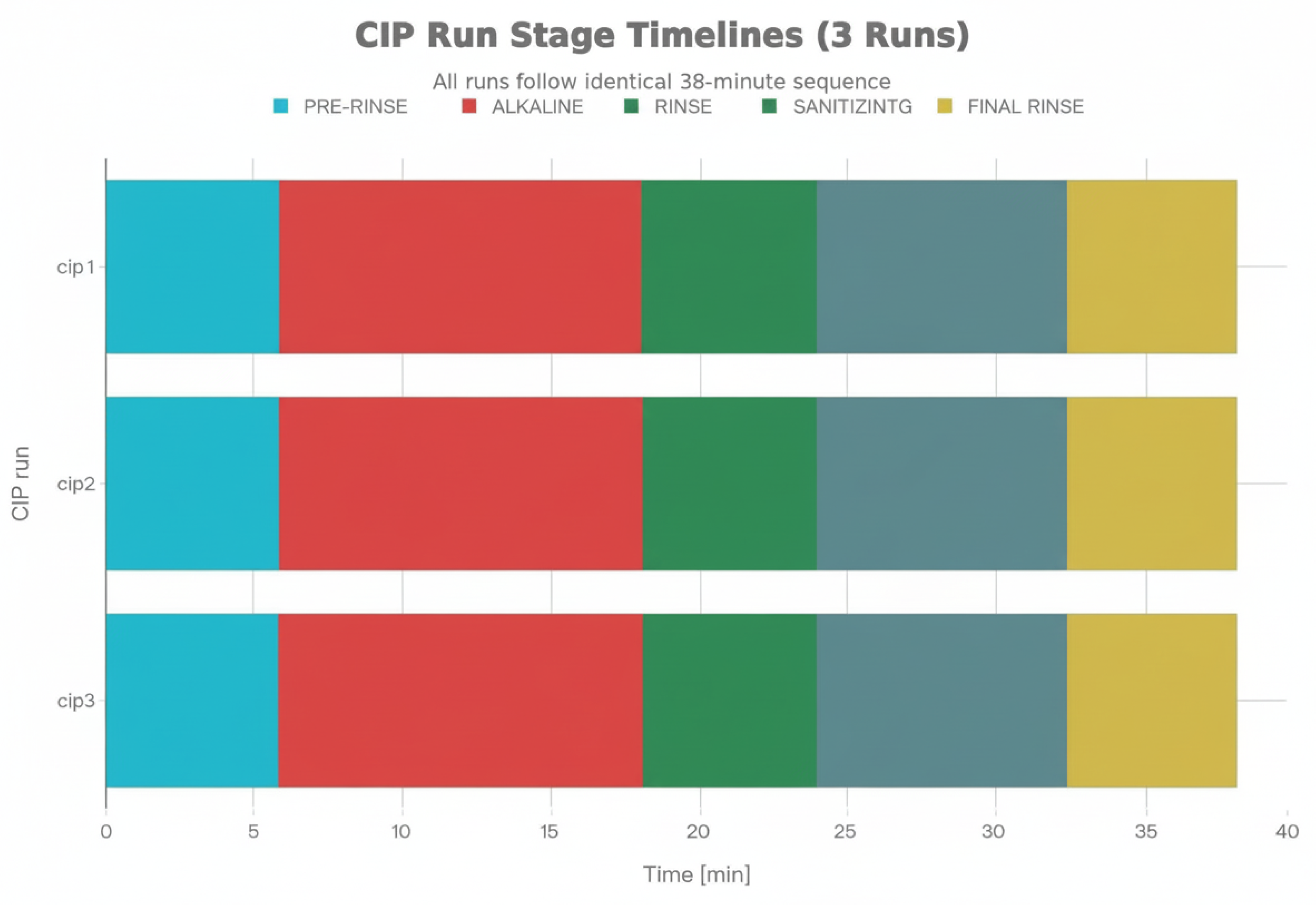

Figure 2 provides an overview of the three experimental CIP runs used for evaluation. Each run comprises the same sequence of stages (pre-rinse, alkaline, intermediate rinse, sanitising and final rinse), executed by the existing CIP programmes with their configured timings. The figure illustrates the relative duration of each stage and shows that, from a timing perspective, all runs follow the expected pattern, with alkaline and sanitising stages occupying the largest fraction of the cycle. The three runs thus provide complementary views of the same programme executed under different operational conditions, highlighting how the architecture’s supervisory and diagnostic outputs evolve from nominal baselines to preventive warnings and more pronounced alert patterns.

6. Results

This section reports the behaviour of the proposed decision-support architecture over three representative CIP executions, using the evaluation metrics defined in

Section 5.5. The analysis is organised by CIP stage (alkaline, sanitising and final rinse) and focuses on stage-level compliance, label coherence, temporal stability, temporal response of alerts and notifications, and the consistency of language-based explanations with the underlying data.

As summarised in

Figure 2, all evaluated runs follow the same five-stage structure with comparable stage durations. The subsequent analysis concentrates on how the decision-support architecture behaves within these fixed programmes, under nominal conditions (baseline equipment health), preventive warning scenarios (subtle deviations indicating emerging maintenance needs) and diagnostic alert regimes (more pronounced patterns requiring prioritised attention), rather than on extrapolating statistical properties to large cohorts of executions.

6.1. Stage-Level Performance

Table 7 summarises the main evaluation metrics for each CIP stage, reporting mean and standard deviation across the three executions to provide a compact overview. Given the small number of runs and their deliberately contrasting conditions, these aggregates are interpreted qualitatively, as descriptors of the examined cases rather than as statistically representative estimates.

Table 8 and

Table 9 detail the stage-specification compliance per execution and the corresponding aggregates. In the sanitising stage, all three runs operate entirely within their predefined bands, yielding a compliance of

. In contrast, the alkaline stage exhibits markedly different behaviours across the three cases: CIP 1 (nominal baseline) remains fully within specification, CIP 2 (preventive warnings) spends 75% of the time within acceptable ranges with occasional excursions signalling pump or temperature regulation drift, and CIP 3 (diagnostic alerts) spends virtually no time inside the prescribed bands due to sustained flow and temperature deviations requiring prioritised maintenance review.

The alkaline spread is therefore intentional: it exposes the decision-support layer to both optimal equipment performance and degraded operational regimes that remain within regulatory safety margins but signal maintenance opportunities. This makes the alkaline stage particularly useful for evaluating whether the supervisory logic and explanations remain coherent when process conditions transition from baseline health to preventive and diagnostic alert patterns.

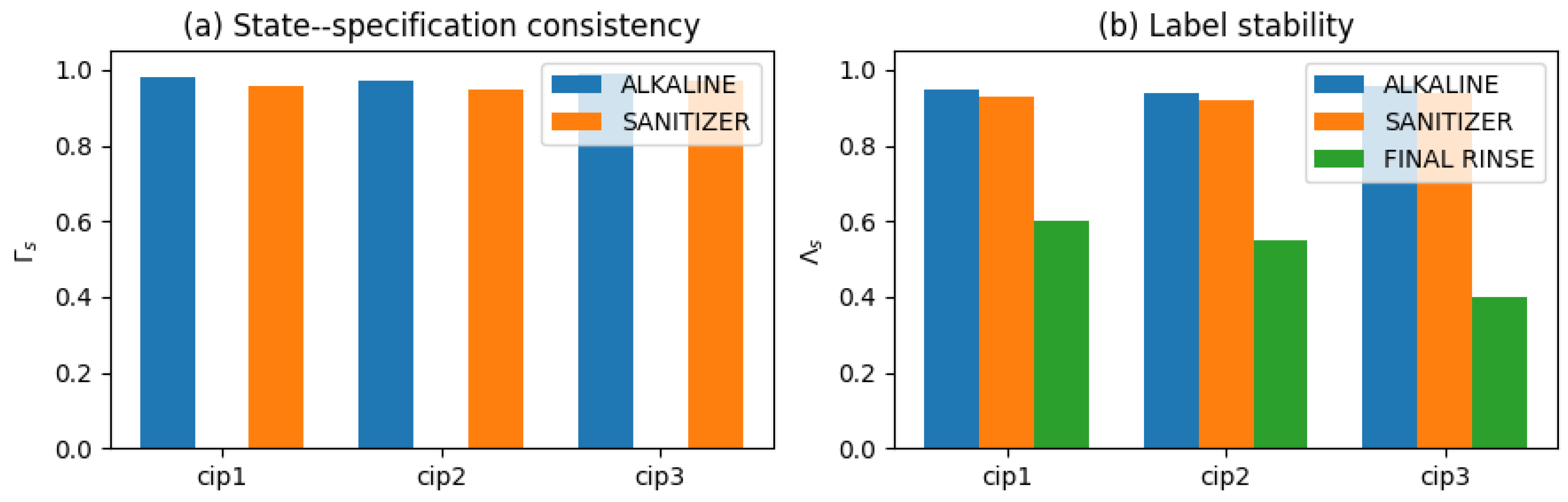

Beyond the raw time within specification, the state–specification consistency metric captures how often the discrete supervisory labels agree with the process conditions. For the alkaline stages across the three executions, attains a mean value of approximately with a small dispersion, while the sanitising stages achieve . In other words, even when the alkaline stage spends little or no time within its specification (as in CIP 3), the supervisory layer almost never reports NORMAL when key variables are outside their prescribed bands, nor WARNING/CRITICAL when they remain within target ranges. This reinforces the internal coherence of the rule-based monitoring and labelling logic across contrasting equipment health states and operating regimes.

The stability metric further characterises how these labels evolve over time. For pre-rinse, alkaline and sanitising stages, the number of label transitions per minute is either zero or very small, with alkaline stages exhibiting on the order of changes per minute. This suggests that, under nominal or preventive warning conditions, the supervisory state does not oscillate excessively and remains easy to interpret by operators as meaningful diagnostic trends rather than spurious noise. An interesting outlier appears in the final-rinse stage of CIP 3, where reaches the order of 10 changes per minute, yielding a stage-level mean of roughly changes per minute with a large standard deviation. This behaviour corresponds to the deliberately stressed diagnostic scenario with highly variable conditions, in which the supervision layer reacts aggressively as the process repeatedly crosses specification boundaries. While this confirms that supervision remains responsive, it also points to the need for additional hysteresis or smoothing mechanisms in future iterations, to avoid overwhelming operators with rapid state changes in known unstable regimes.

Figure 3 illustrates these patterns per execution and per stage. Even in the alkaline run with virtually no time within specification (CIP 3, diagnostic alerts), the state–specification consistency remains close to one, whereas label instability is confined to the stressed final-rinse stage of the same diagnostic execution. This case-by-case view supports the interpretation that the architecture preserves coherent supervisory states across nominal baseline, preventive warning and diagnostic alert regimes, and that observed instabilities are localised, interpretable and correspond to genuinely unstable process conditions rather than algorithmic artifacts.

6.2. Alert and Notification Timing

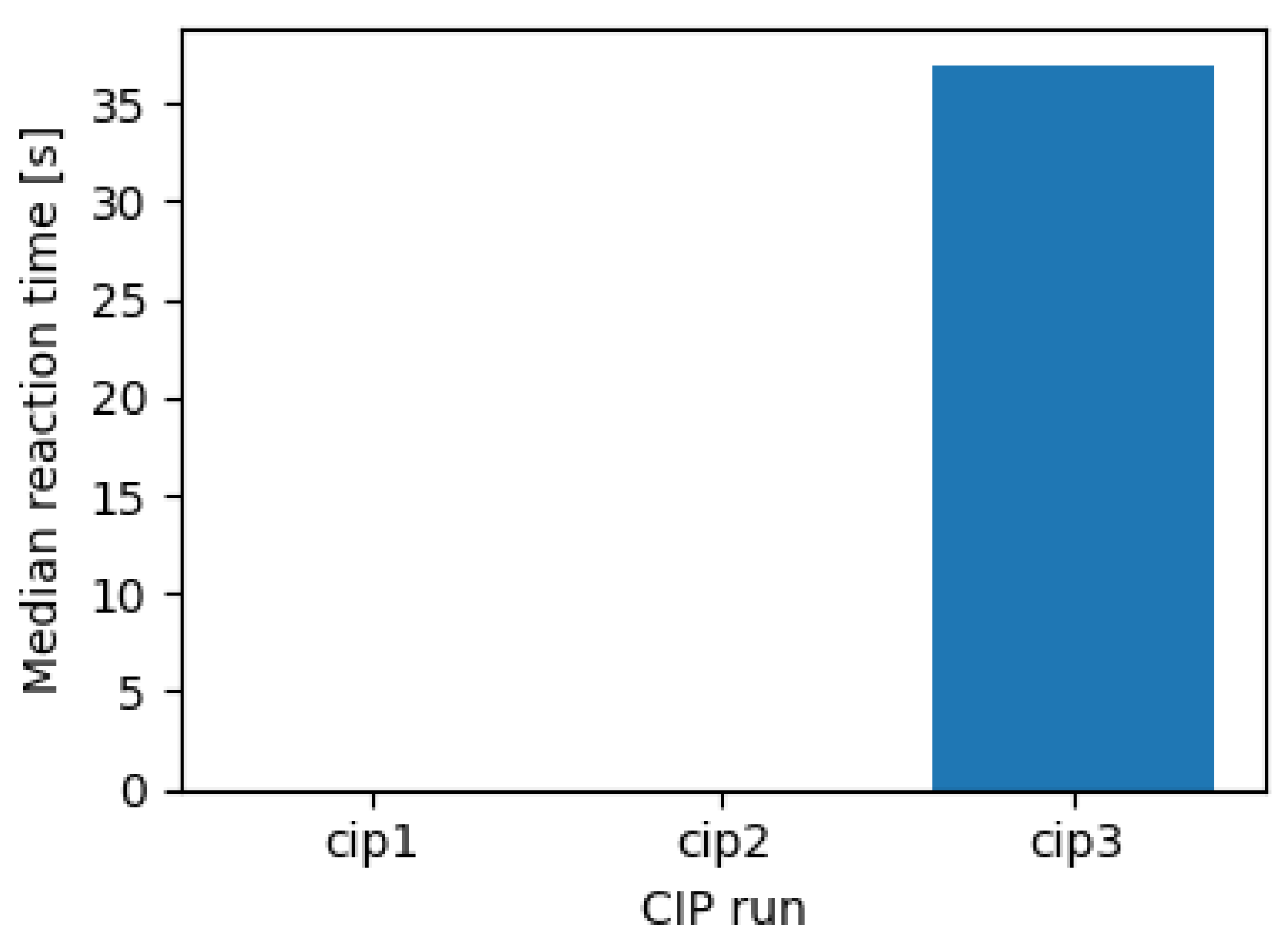

The architecture not only classifies supervisory states in real time, but also timestamps alert and notification events, which enables an initial characterisation of temporal behaviour. Among the three representative executions, only CIP 3 (diagnostic alerts) exhibits sustained critical episodes according to the discrete supervisory state, so quantitative reaction times can only be meaningfully computed for that case.

Figure 4 summarises the median reaction time between the onset of a critical episode and the corresponding alert for each execution. In CIP 3, the median reaction time is approximately 35–36 s. For the considered CIP application, this delay is acceptable: it reflects end-to-end supervisory filtering over slow hydraulic dynamics, rather than the latency of LLM inference, and still leaves sufficient time for corrective actions within the process safety margins while avoiding spurious alerts on transient sensor spikes.

In practice, this reaction time incorporates both the time needed to accumulate enough evidence from noisy process data and the filtering performed by the supervisory logic to ensure that alerts correspond to persistent deviations rather than acceptable process variability. As a result, critical alerts are raised only for sustained equipment degradation or operational stress patterns, and the LLM-based supervisor can generate coherent, context-aware explanations that support maintenance prioritisation, instead of reacting to short-lived fluctuations.

The same framework was used to inspect the anticipation window of warning notifications and the LLM response latency. In CIP 2 (preventive warnings), warnings appeared tens of seconds before any escalation to critical states (when such escalation occurred), providing early visibility of deteriorating conditions and actionable lead time for preventive interventions. End-to-end LLM response times for diagnostic queries remained in the order of a few seconds across all executions. Although these measurements are limited to a small number of episodes, they indicate that language-based explanations do not become a bottleneck in the supervisory loop and that the architecture can provide operators with timely, actionable diagnostic information suitable for maintenance planning.

6.3. Diagnostic Pattern Characterisation Across Executions

To illustrate how the architecture differentiates nominal, preventive and diagnostic regimes,

Table 10 summarises the distribution of supervisory states and alert patterns across the three representative executions.

CIP 1 serves as the reference baseline: all process variables remain within nominal bands, no warnings are issued, and the conversational interface confirms normal operation. CIP 2 exhibits intermittent WARNING-level diagnostics in the alkaline stage (e.g., slightly reduced flow, minor temperature excursions) that do not compromise product quality or regulatory compliance but indicate emerging equipment drift. These warnings complete successfully without escalating to critical states, and the architecture provides natural-language summaries highlighting the trend (e.g., “flow is 10% below optimal across the last three cycles, consider pump inspection”). CIP 3 presents sustained warnings and clusters of CRITICAL labels in alkaline and final-rinse stages, corresponding to more pronounced flow and conductivity deviations. While the execution still completes within regulatory bounds, the alert density and LLM-generated diagnostics signal equipment conditions that warrant prioritised maintenance review to prevent unplanned downtime.

This progression demonstrates that the architecture can distinguish between normal process variability (CIP 1), conditions that benefit from scheduled preventive maintenance (CIP 2), and patterns that call for more urgent diagnostic attention (CIP 3), addressing the supervisory challenge outlined in the introduction: interpreting operational signals rather than merely detecting catastrophic failures.

6.4. Semantic Behaviour and Language-Based Outputs

Beyond numeric metrics, the logs capture the natural-language explanations and summaries generated by the conversational interface. Spot checks were performed to verify consistency between language-based outputs and enriched data, focusing on numerical summaries (average temperatures, flow rates, warning counts) reported by the LLM during diagnostic queries. When the corresponding windows of enriched records were extracted from the buffer, the computed values matched those stated in the explanations within small relative tolerances, with median errors below 3% for the audited samples.

For instance, during the alkaline stage of CIP 3 (diagnostic alerts), the assistant reported average values for temperature, pH and flow over a recent time window (e.g., temperature around 73 °C and flow close to

), as well as the number of warning and critical samples. Representative examples of these checks are summarised in

Table 11, confirming that the conversational interface grounds its summaries on actual buffered data rather than hallucinating numerical figures.

Representative examples of these checks are summarised in

Table 11, which illustrates the close match between temperatures, flows and warning counts reported by the conversational interface and those computed directly from the enriched logs.

Beyond answering isolated diagnostic queries, the conversational layer can also generate compact reports that summarise recent CIP behaviour based on the enriched data streams, including trend analysis across multiple cycles. In the present experiments, such reports were compared against statistics computed directly from the logs, checking that key figures such as average temperatures, flows, stage durations and warning counts remained within small tolerances. A simple fidelity indicator can be defined as the proportion of numeric quantities in a report that fall within a predefined tolerance (for example, less than 1% relative error or within a small absolute band) with respect to the values recomputed from the logs. Under this indicator, all audited reports in the current case study achieved perfect or near-perfect fidelity for the checked quantities, supporting the use of LLM-generated reports as trustworthy, data-grounded views of recent CIP operation suitable for maintenance decision-making.

Similarly, in another interaction during CIP 3, the assistant answered that the current alkaline stage had accumulated dozens of warning states, and explicitly reported the number of warnings observed up to that point. Counting the samples flagged as warnings and critical in the corresponding enriched log around the response timestamp yielded counts that were consistent with the reported figures within the temporal window under inspection. These checks, combined with the high state–specification consistency and the low rate of spurious label transitions in nominal and preventive regimes, provide convergent evidence that the multi-agent architecture not only maintains coherent discrete supervision but also exposes that supervision through language in a way that remains faithful to the underlying data and actionable for preventive maintenance planning.

6.5. Operational Supervision Capabilities

Beyond numeric performance metrics, the architecture changes how CIP supervision and decision making can be carried out in real time.

Table 12 contrasts typical capabilities of traditional CIP supervision with those provided by the proposed multi-agent architecture.

Across the three evaluated runs, the conversational interface handled several dozen real-time queries, including requests to inspect ongoing stages, generate charts, compute numerical diagnostics and compare recent executions against historical baselines. Each diagnostic response was based on hundreds to thousands of recent enriched records, effectively externalising ad-hoc analysis that would otherwise require manual navigation of HMI screens, offline tools and cross-referencing of maintenance logs. In combination with the stage-level metrics, alert timing observations, diagnostic pattern characterisation and semantic consistency checks, these interactions suggest that the architecture not only preserves a coherent and stable supervisory view of the CIP process, but also makes that view more accessible, actionable and maintenance-oriented for human operators in real time.

7. Discussion