1. Introduction

Cutaneous melanoma is one of the most aggressive cancers, whose aggressiveness depends on important morphological parameters with prognostic value. In this category, we include the Breslow index (maximum depth of the tumor), the Clark level of cutaneous invasion, and the presence of ulceration (either described as destruction of the overlying epithelia or narrowing of the epithelia associated with granulocytic inflammatory infiltrate). Of great importance, there used to be the mitotic count, which was downgraded as an independent prognostic factor in the least recent AJCC (American Joint Committee on Cancer) and WHO (World Health Organization) guidelines; yet it remains valuable for estimating the tumor’s aggressiveness. Along with these tumor particularities, the cytology of the malignant melanocytes is also essential, as the majority of cases present epithelioid appearance, a subtype that correlates with poor prognosis. The tumor can also present spindle cells or, very rarely, rhabdoid cells. Of great prognostic importance is the presence of satellites or microsatellites (groups of tumor cells located within 2 cm of the primary tumor, first identified on gross examination and the second detected under the microscope). Identifying these aspects changes the pTNM stage of the tumor, placing the patient in the Nc category, independent of lymph node status. Such a change in the pTNM also occurs if the tumor nodules are detected at a distance greater than 2 cm from the primary tumor, indicating the presence of in-transit metastasis. [

1,

2,

3]

Due to the tumor’s prognosis and continuously increased incidence in the general population all around the Globe, various therapies have been developed in the past decades. A major discovery was made in the early 2000s, when BRAF (B-Raf proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase) and its role in melanoma development were described. Thus, based on the data gathered at the time, targeted therapy was invented. [

4]

Metastatic melanoma has a very poor prognosis. This form is very resistant to chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or targeted therapy and represents a constant challenge for oncologists. [

5]

This narrative is based on literature from PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science. The research included combinations of keywords such as: ABCB5, melanoma, melanoma stem cells, immunotherapy, and tumor microenvironment. Priority was given to peer-reviewed original articles and systematic reviews regarding these topics, with a focus on the past five years. However, relevant studies published before this time interval were also included, since significant findings extended beyond the specified time frame. Thus, the total number of articles included is 90.

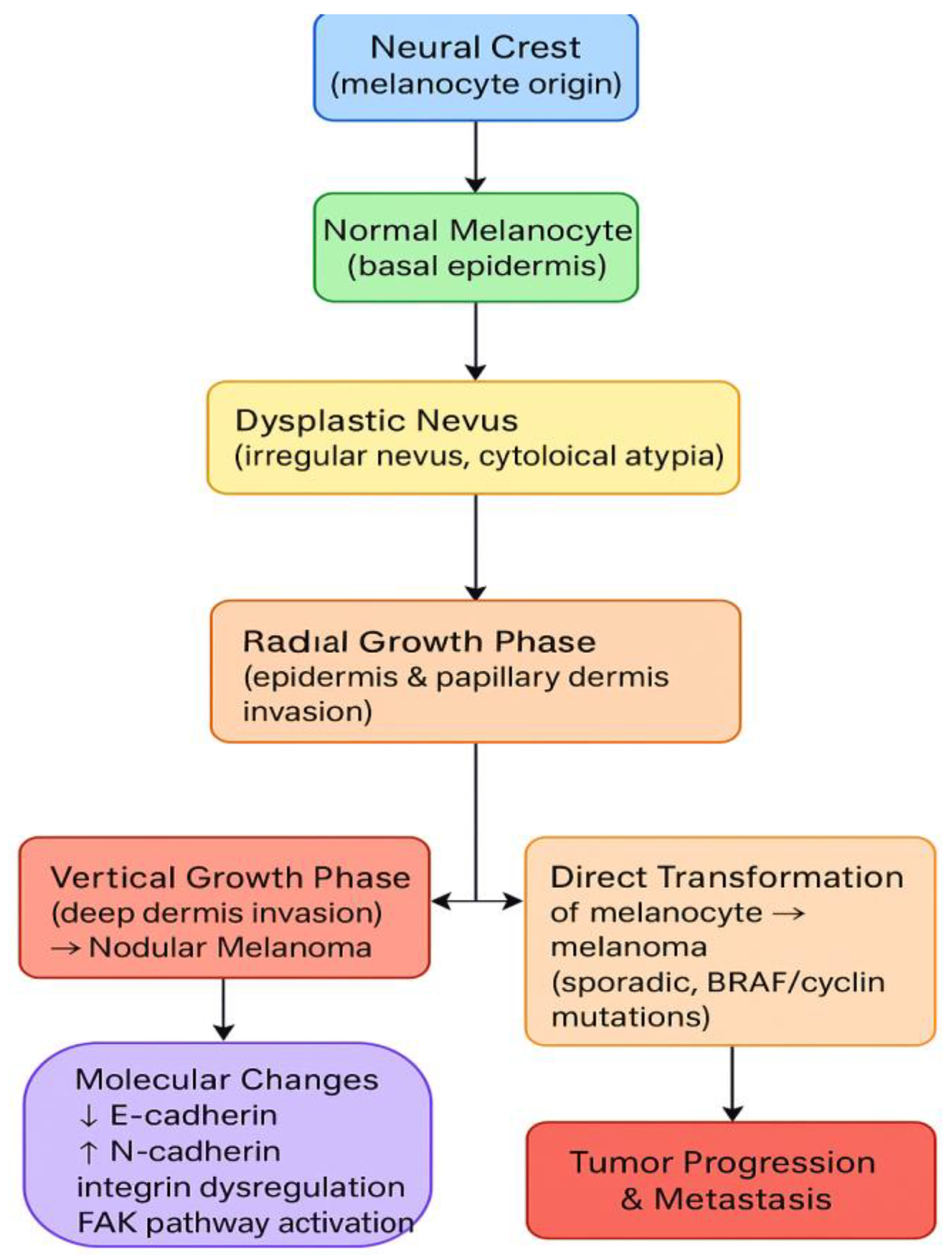

2. Tumor Development

Melanoma originates in melanin-producing cells called melanocytes. These cells form in the neural crest and undergo a long migratory trajectory during embryonic development. When homeostasis is maintained, melanocytes are distributed in the basal layer of the epidermis, where they interact with adjacent keratinocytes via various molecules and factors. There are two pathways through which melanoma can develop. [

6]

The first one represents the genesis of a dysplastic nevus, characterized by irregular architecture and cytological atypia. Distinct tumor growth patterns follow this. The first phase is the radial growth phase, during which the tumor invades the overlying epithelium and extends into the papillary dermis. The second phase is the vertical growth phase, during which the tumor cells extend into the deeper layers of the dermis. The outcome of the vertical growth phase is nodular melanoma, which is not a distinct subtype but rather a consequence of tissue invasion. [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]

In the second pathway, the mechanisms by which normal melanocytes transform into melanoma are not fully understood. The genetic background is significant, as BRAF mutations are common. The most common mutation identified is BRAF V600E; however, BRAF V600K has also been described. These lead to MAPK activation, which promotes tumor growth and invasion. Sporadic melanoma has also been associated with various mutations, notably those of cyclin D1, the cyclin-dependent kinases cdk4/cdk6, and cdk2. (

Figure 1) [

6,

11]

As described earlier, keratinocytes and melanocytes interact continuously via various molecules. This indicates that melanocyte proliferation is under the control of keratinocytes. This process is disrupted in melanoma, as E-cadherin is downregulated. In the meantime, N-cadherin (a preferred cell adhesion molecule in this tumor) is upregulated, replacing E-cadherin and allowing tumor cells to escape apoptosis. Along with E-cadherin downregulation, integrin dysfunction also promotes tumor growth and metastasis. Integrins can regulate cellular responses to signals from the microenvironment and surrounding cells. Stressor factors can enhance the activation of pathways that disrupt the mechanism, such as FAK (a protein kinase that regulates integrin-mediated signaling and enhances melanocytic proliferation). [

12,

13,

14]

3. Tumor Microenvironment

The tumor microenvironment is essential in tumorigenesis. This is defined as the total number of molecules and cells that form a soil-like environment for the tumor cells. This phenomenon was described over a century ago and explains the necessity for tumor cells to grow in an environment that provides the nutrients they require. The tumor foundation and its microenvironment are the stroma, composed of fibroblasts, extracellular matrix, blood vessels, proteins, and inflammatory cells. The microenvironment is crucial to the success of immunotherapy. This relies on T cell activity and their interactions. The tumor cells in melanoma exhibit marked heterogeneity, characterized by variable expression of HLA class I molecules and immune regulators, such as PD-L1. Such molecular diversity, both within individual tumors and between anatomically distinct lesions, significantly influences tumor behavior and therapeutic resistance. [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]

A key transcription factor in melanoma is MITF (Microphthalmia-associated transcription factor). This regulates cell proliferation, invasion, and cell behavior. Cells with high MITF expression have a higher proliferation rate and a greater risk of invasion than cells with negative or low expression levels. [

21,

22]

Multiple factors regulate the expression of the MITF gene. The transcription factor CREB (cAMP Response Element-Binding protein) recognizes a motif within the MITF promoter. It is responsive to elevated intracellular cAMP levels, which occur downstream of melanocortin 1 receptor (MC1R) signaling. This pathway controls the pigmentation of hair and skin. The ability of CREB to activate MITF-M transcription is dependent on the presence of SOX10 (SRY- Sex-determining Region Y-Box 10), another regulator of MITF expression. (

Figure 2) [

20,

23]

PAX3, a paired box homeodomain transcription factor, is essential for melanocyte development and for the activation of melanocyte stem cells. It regulates MITF-M both at the level of transcription and activity. [

24,

25] PAX3 expression is negatively regulated by TGFβ and interleukin-6 receptor signaling in the skin. Additionally, PAX3 has been shown to activate the BRN2 promoter via PI3K signaling, and it may mediate similar signaling effects on the MITF-M promoter. PAX3 is downstream of the Hippo signaling pathway, which regulates organ size and cellular responses to mechanical stress. The Hippo effectors YAP and TAZ function as transcriptional cofactors for PAX3, and their deletion in neural crest cells results in developmental defects and reduced MITF expression. [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]

The Hippo–PAX3–MITF axis plays a prominent role in melanoma. In cutaneous melanoma, collagen-induced stiffness has been shown to activate YAP/PAX3 signaling, resulting in increased MITF expression. However, this mechanotransduction-driven upregulation of MITF can be disrupted by TGFβ, which redirects YAP to form a complex with TEAD and SMAD proteins, thereby diverting its transcriptional activity away from MITF regulation. This TGFβ-mediated mechanism is also believed to be necessary for establishing quiescent melanocyte stem cells, which are characterized by low MITF expression. [

31,

32,

33,

34]

Another regulator of MITF is FOXD3, a transcription factor that represses MITF by blocking PAX3 binding to its promoter. During development, FOXD3 helps direct cells away from a melanoblast fate toward neural or glial lineages by downregulating MITF. In melanoma, FOXD3 is widely expressed and contributes to resistance to BRAF inhibitors, likely by suppressing MITF expression and concurrently upregulating ERBB3 (HER3). [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39]

SOX10, a key transcription factor in neural crest development and melanocyte biology, also directly binds the MITF promoter in cooperation with PAX3 to activate its expression. SOX10 is highly expressed in melanoma and is essential for tumor initiation and maintenance. [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44] Importantly, in BRAFV600E-mutant melanomas, ERK signaling inhibits SOX10 function by preventing its SUMOylation, a post-translational modification necessary for its transcriptional activity. This results in reduced MITF expression and may contribute to phenotype switching and therapeutic resistance. [

45]

SOX10 interacts with PGC1α (PPARGC1A), a transcriptional coactivator that itself is a target of MITF and is stabilized by cAMP signaling downstream of α-MSH. PGC1α can also activate MITF expression, suggesting the existence of a positive feedback loop that reinforces MITF activity under conditions of elevated cAMP. The coordinated action of CREB, SOX10, and PGC1α ensures activation of the MITF promoter, integrating environmental signals with transcriptional control of melanocyte identity and melanoma behavior. [

46,

47,

48]

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) are essential for modulating the melanoma microenvironment. Ever since 1989, Clark has defined the inflammatory infiltrate as absent, brisk, or non-brisk. Brisk inflammation is characterized by the presence of lymphocytes diffusely within the tumor or surrounding it, whereas focal aggregates of lymphocytes, distributed irregularly, represent non-brisk inflammation. The distribution of the lymphocytes is important in the vertical growth phase, and it is described to have prognostic significance. A decrease in the count of lymphocyte infiltrate is correlated with the immune system's inability to fight the tumor and with alterations in defense mechanisms. Therefore, cases with a brisk inflammatory infiltrate have a better prognosis than those without. [

49,

50,

51]

4. Metastatic Melanoma

Metastatic melanoma, which most often arises from nodular or superficial spreading melanoma, carries a poor prognosis. Despite nodular melanoma accounting for most metastatic cases, some studies describe superficial spreading melanoma as the leading cause. Therefore, despite the Breslow index being the most important prognostic parameter for tumor morphology, thin melanomas and melanomas with radial growth also have a high metastatic potential. Among melanoma subtypes associated with a high risk of progression, we encounter lentigo maligna melanoma and acral melanoma. [

52,

53]

From a clinical perspective, the patients can present with cutaneous lesions, solitary or multiple. Metastases to internal organs can present various symptoms, such as bleeding or organ dysfunction. The risk factors associated with metastatic melanoma are the male gender, the location of the tumor (head and neck tumors), lymphatic and vascular invasions, and the presence of BRAF mutation. [

54]

From a histological point of view, metastatic melanoma can present with a high morphological variation. Cells can present with characteristics similar to those of the primary tumor, which is more commonly composed of epithelioid cells, or with spindle cells, pleomorphic cells, small cells, clear cells, plasmacytoid cells, rhabdoid cells, or even signet cells. In these cases, the differential diagnosis is challenging, and a variety of immunohistochemistry markers must be performed for confirmation. Melanoma is an excellent mimic of other entities, sometimes resembling poorly differentiated carcinomas and various sarcomas. Melanoma typically expresses markers such as SOX10 [

Figure 4], S100, HMB45, MelanA, MITF, or PRAME and is negative for myogenic or epithelial markers. (

Figure 3) The challenge arises when the tumor is dedifferentiated and loses its classic positivity for these markers. One of the most specific markers is SOX10, which is widely used to confirm the diagnosis and for sentinel lymph node protocols. This marker is not specific to melanoma, but it is susceptible and shows higher specificity than other markers. The use of multiple melanocytic markers together can significantly increase diagnostic accuracy. Lately, PRAME has been tested and used for primary and metastatic melanoma and is thought to have a good sensitivity to the tumor. However, this new marker alone is not the most reliable for distinguishing primary malignant melanocytic neoplasms and should be combined with other markers. For metastatic melanoma, PRAME can be expressed even in certain dedifferentiated areas, aiding significantly in revealing the tumor’s origin. [

55,

56,

57,

58]

Dedifferentiated metastatic melanoma can present a part of the tumor that still preserves the classic aspect of melanoma, but most of the neoplasm can be far from the conventional aspect. This dedifferentiated component can resemble an undifferentiated sarcoma or pleomorphic sarcoma. In cases where all IHC markers, including PRAME, are negative, molecular analysis is mandatory. The most common mutation is BRAF V600E or V600K, being identified in half of melanoma cases. Other mutations that can be encountered include NRAS Q61, especially in desmoplastic melanoma or in cases without a BRAF mutation. KIT mutations on exons 11 or 13 can be encountered, especially in acral melanoma. NF1 can also be identified, and it is most seen in triple-negative melanoma (negative BRAF, NRAS, and KIT). The most helpful tool is NGS (Next Generation Sequencing), which can analyze multiple mutations, fusions, or amplifications. Other techniques that can be useful are FISH (Fluorescent in situ hybridization) and mutational signatures. Mutational signatures are determined from tumor DNA, which undergoes whole-genome sequencing with identification of somatic mutations compatible with UV exposure. This method is essential and innovative, but it also holds several limitations and lacks clinical standardization; therefore, it is used mainly in research. [

59,

60,

61]

Figure 3.

Regulation of the tumor microenviroment.

Figure 3.

Regulation of the tumor microenviroment.

Figure 4.

Metastatic melanoma. Proliferation of malignant melanocytes located in the connective tissue (HE), Immunohistochemistry reaction for antibody SOX10. Personal collection.

Figure 4.

Metastatic melanoma. Proliferation of malignant melanocytes located in the connective tissue (HE), Immunohistochemistry reaction for antibody SOX10. Personal collection.

5. Current Therapeutic Options

For early-stage melanoma (pT1, pT2), the primary treatment is surgical wide excision with negative margins. Surgery is mandatory not only as a therapeutic option but also as a diagnostic tool, as histopathological examination is the gold standard for diagnosis. The guidelines emphasize the importance of lymph node status, and thus sentinel lymph node excision and examination usually follow surgery. The systemic melanoma treatment landscape has undergone significant changes since the beginning of the century, when BRAF was discovered. The previous therapeutic options for advanced stages mainly consisted of chemotherapy and sometimes radiation therapy. Dacarbazine played an important role despite its numerous side effects. Platinum-based drugs like carboplatin were also used in combination with multiple other medicines, including alkylating agents or dacarbazine. Radiation therapy could also be an option, being reserved for cases with extended lymph node involvement. [

63]

The discovery of BRAF in 2002 led to the development of targeted therapy. Of the most common drugs used, Vemurafenib has held the spotlight for the longest. However, the resistance to this type of treatment has been reported in many cases. This is observed in nearly half of patients and is primarily attributable to intratumoral heterogeneity. Cases that do not present with BRAF mutation also benefit from therapy, but with a less pronounced response. [

64,

65,

66]

The treatment of metastatic melanoma has also changed significantly in the last decade, with the development of targeted therapy and immunotherapy. Without modern treatment, the overall survival used to be 6 to 9 months, and less than 10% of the patients survived for 5 years. Following the development of immunotherapy, the survival rate has increased to over 50 months in the first 5 years, and some studies report a 6-year survival rate. The first line of treatment in patients with high LDH levels and visceral metastases is represented by anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-L1 medication, such as ipilimumab and nivolumab. These options can significantly increase the survival rate; in half of the patients, this is estimated at 7 years. [

68]

A possible combination is nivolumab and relatlimab, an anti-LAG-3 agent that is thought to be better tolerated. Patients who present BRAF mutations can be treated with BRAF inhibitors and can obtain a fast response, yet in the long term, resistance is common. In such cases, immunotherapy is preferred or various combinations of agents are used. When patients do not respond to these therapies, innovative options are considered. One of these is lifileucel, a therapy that uses isolated infiltrating T lymphocytes (TIL) from the patient’s tumor. These lymphocytes are then reinfused to attack the tumor cells. The steps include the excision of the metastatic tumor, the isolation and cultivation of lymphocytes, the administration of chemotherapy to suppress the immune response, and the reinfusion of the lymphocytes. The method was approved in 2022 for advanced metastatic melanoma that does not respond to PD-1 inhibitors or targeted therapy. The key to a therapeutic success is based on the ability of the cells to recognize the tumor antigens and attack the tumor cells. Available studies showed increased survival beyond 2 years in this category of cases. [

64,

65,

69,

70]

Other options are currently being explored, such as toll-like receptors 9, 7/8, stimulators of interferon genes, and agonists. These studies aim to modulate, prevent and regulate the immune system response to the tumor. [

71]

6. Stem Cells in Melanoma

Melanoma stem cells (MSCs) are a particular population of cells that can self-renew and are directly involved in the progression of the disease. Their existence has been a hot topic for a while in the dermatopathology and oncology fields, but they have been identified eventually with the help of various markers. These specialized cells are considered to express CD271 (NGFR), CD133, ALDH1, Nestin, CD44, and ABCB5. The plasticity of these stem cells is remarkable, as they can be present in a proliferative state or a stem-like state. The cells are activated especially by factors such as hypoxia, ischemia, inflammation, oxidative stress, and chemotherapy. Thus, MSCs are not a rigid population; they are cells in a constant reprogramming state that can change according to the environment. Functionally, the cells present high resistance to chemotherapy and immunotherapy, and they express efflux transporters, checkpoint molecules (e.g., PD-L1), and synthesize immunomodulating factors that interfere with the T cell response in the microenvironment. (figure 4) [

72,

73]

7. ABCB5

The ABCB5 gene was discovered in 1996. This gene encodes ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter family, subtype B, member 5, a special protein that has multiple isoforms. From a pathophysiological perspective, the focus on ABCB5 was maintained on its role as a marker in tumors, more specifically as a stem cell marker, and in cancer biology. [

74]

Mesenchymal cells can differentiate into multiple lineages of the connective tissue. These cells are essential for creating the extracellular matrix, for the interaction with the immune system, and for synthesizing various molecules that are important for homeostasis. [

75]

The isoform that is more studied and predominantly expressed in melanoma is ABCB5α, while other isoforms are primarily associated with different processes, such as glycolysis or atherosclerosis. ABCB5 has been identified on MSCs and it is expressed in tumor cells with stem-like features. It is believed that ABCB5 can reduce drug accumulation within cells. Some studies describe that ABCB5-expressing cells persist after treatment with temozolomide, dacarbazine, and vemurafenib, both in vitro and in vivo, while the overall tumor burden decreases. These cells are also more frequent in tumor samples from treated patients. Together, this suggests that ABCB5+ cells are more resistant to therapy and may contribute to disease recurrence. [

76]

Melanoma exhibits high intratumoral heterogeneity, and ABCB5 contributes to the formation of distinct cell subpopulations, with differential proliferative and invasive capacities. ABCB5-positive cells can coexist with ABCB5-negative cells, a heterogeneity that influences therapeutic response, as the positive clones can persist after treatment and repopulate the tumor. [

74,

75,

76]

The pathophysiological mechanisms regarding the ability of ABCB5 to change the response to treatment are closely related to the plasticity of MSCs. The cells that express ABCB5 present a well-controlled differentiation and high renewal rate; thus, recurrence and long-term survival of the tumor cells are enhanced. The primary molecular mechanism by which ABCB5 ensures the survival of the cells is the active efflux of the drugs. In addition, ABCB5 regulates the homeostasis of the cells and helps the tumor cells avoid cell death induced by therapy. This is achieved by influencing the expression of antioxidants and pathways like PI3K/Akt.

High expression of ABCB5 is also associated with low apoptosis, a phenomenon resulting from changes in BCL-2 protein expression. Recent studies have shown that ABCB5 is regulated by miRNA, which can alter the phenotype of tumor resistance. When miR-145 is expressed in normal amounts, it can suppress ABCB5, reducing its level in cells. This is associated with the tumor cells' inability to extrude the drugs. However, in advanced melanoma, miR-145 levels are often decreased, leading to ABCB5 overexpression and increased therapy resistance. Restoring miR-145 to its normal level could increase sensitivity to standard treatment. [

77,

78]

ABCB5-positive cells can influence the microenvironment by synthesizing angiogenic and inflammatory factors that support tumor growth. These factors are VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor), IL-6 (interleukin 6), IL-8 (interleukin 8), TGF-B (tumor growth factor Beta). The interaction between these cells, T cells and macrophages, favors immune suppression and a lack of antigen recognition. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) will present an M2 phenotype due to cytokines secreted by ABCB5-positive cells. This phenotype is associated with suppression of adaptive immune response, further promotion of angiogenesis, and remodeling of the extracellular matrix. The interaction with T cells, especially T cells CD8+, leads to overexpression of PD-L1 and suppression of T cell function. [

79]

Figure 6.

Role of ABCB5 in melanoma.

Figure 6.

Role of ABCB5 in melanoma.

Recent data suggest that ABCB5 expressions may be linked to epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Positive ABCB5 cells exhibit enhanced matrix remodeling and upregulation of MMPs and integrins.

Some studies report that ABCB5 is overexpressed in BRAF inhibitor-resistant melanoma cell lines. Expression patterns varied by drug type and treatment stage, highlighting inter-cell-line heterogeneity. However, ABCB5 knockdown did not restore vemurafenib sensitivity, suggesting it is not a primary driver of BRAF resistance. ABCB5 expression correlated with increased phosphorylated ERK levels (protein in the MAPK pathway), but inhibition of p-ERK, not ABCB5, reversed resistance. These findings, along with previous studies showing variable ABCB5 expression and its co-regulation with other resistance genes, suggest that ABCB5 contributes to chemoresistance and tumor heterogeneity but may not be essential for BRAF inhibitor resistance. [

80,

81,

82]

In melanoma, ABCB5 expression cooperates with other transporters, such as ABCB1 and ABCG2. This co-expression has been associated with multidrug-resistant phenotypes and metabolic reprogramming. The understanding of these cooperative networks is essential for developing combination therapies that can overcome resistance. [

80,

81,

82]

Studies have shown that high expression of ABCB5 has been a reliable indicator of an aggressive form of disease. These patients experienced decreased overall survival, frequent recurrence, and an increased risk of distant metastases. Besides being a prognostic marker, ABCB5 is also a marker of chemotherapy resistance and shows the ability of the tumor to evade the immune response. Detecting the expression of ABCB5 allows risk stratification by identifying populations with a high risk of progression. Also, it helps the selection of patients for clinical studies and highlights the individuals that require closer monitoring. [

83,

84]

Table 1.

Role of ABCB5 in melanoma.

Table 1.

Role of ABCB5 in melanoma.

| Mechanism |

Effect |

Clinical Relevance |

| Drug efflux |

↘ intracellular drug concentration |

Chemoresistance |

| PI3K/Akt pathway activation |

↗tumor cell survival, ↘ apoptosis |

Promotes tumor progression |

| BCL-2 modulation |

Anti-apoptotic shift |

Promotes tumor progression |

| miR-145 suppression |

↗ ABCB5 expression |

Resistance in advanced melanoma |

| Cytokine secretion |

Immunosuppressive microenvironment |

Poor prognosis, enhanced angiogenesis |

| PD-L1 upregulation |

T-cell inhibition |

Immune evasion |

| Association with aggressive phenotype |

↗ recurrence, ↘overall survival |

Prognostic biomarker |

| Potential therapeutic target |

Monoclonal antibodies, inhibitors |

Preclinical studies ongoing |

Understanding ABCB5 and its implications in melanoma opened the way for new therapeutic perspectives. Because ABCB5 is an essential regulator of MSCs and plays a role in drug efflux, this protein is a promising therapeutic target. Inhibiting ABCB5 could increase drug concentration inside the cell and reduce the cells' ability to escape both treatment and the immune response. Monoclonal antibodies targeting ABCB5 could be a great option. These antibodies could recognize the epitope, allowing selective removal of stem cells that express ABCB5 and thus reducing recurrence and metastatic risk. Preclinical studies regarding both inhibitors and monoclonal antibodies are ongoing. [

85,

86,

87]

Combined therapy is the most promising direction regarding new treatments. Chemotherapy, together with ABCB5 inhibitors, could maintain the intracellular concentration of the drugs and lead to tumor death. Immunotherapy could reduce the immunomodulatory capacity of ABCB5+ cells, making the tumor more susceptible to immune attack. Combinations of known targeted therapies, such as anti-BRAF medications, could prevent the proliferation of resistant cells and recurrences. Future studies should follow the direction of developing targeted therapy, exploring ABCB5 in liquid biopsies and integrating immunotherapy with agents that regulate ABCB5 expression (such as miRNA). [

88,

89,

90]

8. Conclusions

Melanoma progression and therapy resistance are driven by complex and dynamic interactions between tumor cells and the microenvironment, involving molecular heterogeneity, tumor cell plasticity and immune modulation. These emchanisms contribute to disease aggressiveness, reccurence and resistance to targeted therapy and immunotherapy. Within this biological context, ABCB5 emerged has been associated with stem-like tumor cell populations, chemoresistance and unpredictable clinical outcomes for the patients. This molecule participates in drug efflux, modulation of apoptosis and promoting tumor growth. Targetting ABCB5 may complement existing therapeutic strategies and contribute to overcoming resistance mechanisms in advanced melanoma stages.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C.T. and O.S.C.; methodology, A.H.S and A.R.C.S.; software, I.G.C., B.I.K.; validation, A.C.T, B.I.K, A.H.S; formal analysis, D.M.C, R.D.H, R.N.; investigation, D.M.C., R.D.H. S.T.M,.; resources, A.C.T, B.I.K. R.D.H.; data curation, S.G.T., S.T.M., B.A.L.,.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C.T., I.G.C., R.N., B.A.L.; writing—review and editing, B.A.L., A.R.C.S, S.T.M, ; visualization, A.C.T., B.A.L, S.G.T.; supervision, D.M.C, A.C.T.; project administration, A.C.T., O.S.C.; funding acquisition, A.C.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

none to declare.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AJCC |

American Joint Committee on Cancer |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

| BRAF |

B-Raf proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase |

| MSCs |

Melanoma stem cells |

References

- WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Skin Tumours. WHO Classification of Tumours, 5th ed. Vol. 12. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2024. Available from: https://publications.iarc.fr.

- Amin, MB; Greene, FL; Edge, SB; Compton, CC; Gershenwald, JE; Brookland, RK; et al. The Eighth Edition AJCC Cancer Staging Manual: Continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more “personalized” approach to cancer staging. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017, 67(2), 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Cancer Observatory. Cancer Today. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2024. Available from: https://gco.iarc.fr/en.

- Ascierto, P.A.; Kirkwood, J.M.; Grob, J.J.; Simeone, E.; Grimaldi, A.M.; Maio, M.; Palmieri, G.; Testori, A.; Marincola, F.M.; Mozzillo, N. The role of BRAF V600 mutation in melanoma. J. Transl. Med. 2012, 10, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, P.F.; Wei, W.; Smithy, J.W.; Acs, B.; Toki, M.I.; Blenman, K.R.M.; Zelterman, D.; Kluger, H.M.; Rimm, D.L. Multiplex Quantitative Analysis of Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes and Immunotherapy Outcome in Metastatic Melanoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 2442–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villanueva, J; Herlyn, M. Melanoma and the tumor microenvironment. Curr Oncol Rep. 2008, 10(5), 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcone, I.; Conciatori, F.; Bazzichetto, C.; Ferretti, G.; Cognetti, F.; Ciuffreda, L.; Milella, M. Tumor Microenvironment: Implications in Melanoma Resistance to Targeted Therapy and Immunotherapy. Cancers 2020, 12, 2870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billottet, C; Jouanneau, J. La relation tumeur-stroma [Tumor-stroma interactions]. Bull Cancer 2008, 95(1), 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrousse, AL; Ntayi, C; Hornebeck, W; Bernard, P. Stromal reaction in cutaneous melanoma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2004, 49(3), 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazurkiewicz, J; Simiczyjew, A; Dratkiewicz, E; Ziętek, M; Matkowski, R; Nowak, D. Stromal Cells Present in the Melanoma Niche Affect Tumor Invasiveness and Its Resistance to Therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22(2), 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Valk, M.J.M.; Marijnen, C.A.M.; van Etten, B.; Dijkstra, E.A.; Hilling, D.E.; Kranenbarg, E.M.; Putter, H.; Roodvoets, A.G.H.; Bahadoer, R.R.; Fokstuen, T.; et al. Compliance and tolerability of short-course radiotherapy followed by preoperative chemotherapy and surgery for high-risk rectal cancer - Results of the international randomized RAPIDO-trial. Radiother. Oncol. 2020, 147, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharouf, N; Flanagan, TW; Hassan, SY; et al. Tumor Microenvironment as a Therapeutic Target in Melanoma Treatment. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15(12), 3147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sil, H.; Sen, T.; Chatterjee, A. Fibronectin-integrin (alpha5beta1) modulates migration and invasion of murine melanoma cell line B16F10 by involving MMP-9. Oncol. Res. 2011, 19, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gargalionis, A.N.; Papavassiliou, K.A.; Papavassiliou, A.G. Mechanobiology of solid tumors. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. Mol. Basis Dis. 2022, 1868, 166555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biffi, G.; Tuveson, D.A. Diversity and Biology of Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts. Physiol. Rev. 2021, 101, 147–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, R.L.; Puré, E. Cancer-associated fibroblasts and their influence on tumor immunity and immunotherapy. Elife 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Xu, J.; Wang, W.; Liang, C.; Hua, J.; Liu, J.; Zhang, B.; Meng, Q.; Yu, X.; Shi, S. Crosstalk between cancer-associated fibroblasts and immune cells in the tumor microenvironment: New findings and future perspectives. Mol. Cancer 2021, 20, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinshaw, D.C.; Shevde, L.A. The Tumor Microenvironment Innately Modulates Cancer Progression. Cancer Res. 2019, 79, 4557–4566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugdahl, E; Aziz, S; Klingen, TA; Akslen, LA. Prognostic value of immune biomarkers in melanoma loco-regional metastases. PLoS One 2025, 20(1), e0315284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, DF; Atkins, MB. PD-1 as a potential target in cancer therapy. Cancer Med. 2013, 2(5), 662–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed Central]

- Hartman, ML; Czyz, M. MITF in melanoma: mechanisms behind its expression and activity. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2015, 72(7), 1249–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roider, E.; Lakatos, A.I.T.; McConnell, A.M.; et al. MITF regulates IDH1, NNT, and a transcriptional program protecting melanoma from reactive oxygen species. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 21527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, SR; Tiago, M; Caksa, S; et al. SOX10 requirement for melanoma tumor growth is due, in part, to immune-mediated effects. Cell Rep. 2021, 37(10), 110085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, D.; Lu, M.; Huang, L.; et al. Pax3 functions at a nodal point in melanocyte stem cell differentiation. Nature 2005, 433, 884–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medic, S; Ziman, M. PAX3 expression in normal skin melanocytes and melanocytic lesions (naevi and melanomas). PLoS One 2010, 5(4), e9977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustakas, A. TGF-beta targets PAX3 to control melanocyte differentiation. Dev Cell. 2008, 15(6), 797–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y; Cui, S; Li, W; Zhao, Y; Yan, X; Xu, J. PAX3 is a biomarker and prognostic factor in melanoma: Database mining. Oncol Lett. 2019, 17(6), 4985–4993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonvin, E; Falletta, P; Shaw, H; Delmas, V; Goding, CR. A phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-Pax3 axis regulates Brn-2 expression in melanoma. Mol Cell Biol. 2012, 32(22), 4674–4683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z; Moroishi, T; Guan, KL. Mechanisms of Hippo pathway regulation. Genes Dev. 2016, 30(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rastrelli, M; Tropea, S; Rossi, CR; Alaibac, M. Melanoma: epidemiology, risk factors, pathogenesis, diagnosis and classification. In Vivo 2014, 28(6), 1005–1011. [Google Scholar]

- Miskolczi, Z; Smith, MP; Rowling, EJ; Ferguson, J; Barriuso, J; Wellbrock, C. Collagen abundance controls melanoma phenotypes through lineage-specific microenvironment sensing. Oncogene 2018, 37(23), 3166–3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu, HJ; Kim, C; Jang, H; et al. Nuclear Localization of Yes-Associated Protein Is Associated With Tumor Progression in Cutaneous Melanoma. Lab Invest. 2024, 104(5), 102048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, JH; Fisher, DE. Melanocyte stem cells as potential therapeutics in skin disorders. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2014, 14(11), 1569–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrowski, SM; Fisher, DE. Biology of Melanoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2021, 35(1), 29–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, AJ; Erickson, CA. The making of a melanocyte: the specification of melanoblasts from the neural crest. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2008, 21(6), 598–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F; Ma, W; Fan, D; Hu, J; An, X; Wang, Z. The biochemistry of melanogenesis: an insight into the function and mechanism of melanogenesis-related proteins. Front Mol Biosci. 2024, 11, 1440187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornish, D; Holterhues, C; van de Poll-Franse, LV; Coebergh, JW; Nijsten, T. A systematic review of health-related quality of life in cutaneous melanoma. Ann Oncol. 2009, 20 (Suppl 6), vi51–vi58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, EV; Basile, KJ; Kugel, CH, 3rd; et al. Melanoma adapts to RAF/MEK inhibitors through FOXD3-mediated upregulation of ERBB3. J Clin Invest. 2013, 123(5), 2155–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alver, TN; Lavelle, TJ; Longva, AS; Øy, GF; Hovig, E; Bøe, SL. MITF depletion elevates expression levels of ERBB3 receptor and its cognate ligand NRG1-beta in melanoma. Oncotarget 2016, 7(34), 55128–55140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letsch, A.; Keilholz, U.; Schadendorf, D.; Nagorsen, D.; Schmittel, A.; Thiel, E.; Scheibenbogen, C. High frequencies of circulating melanoma-reactive CD8+ T cells in patients with advanced melanoma. International Journal of Cancer 2000, 87(5), 659–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerdahl, J; Ingvar, C; Måsbäck, A; Jonsson, N; Olsson, H. Risk of cutaneous malignant melanoma in relation to use of sunbeds: further evidence for UV-A carcinogenicity. Br J Cancer 2000, 82(9), 1593–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, JC; Wunderlich, J; Loftus, SK; et al. Frequent mutations in the MITF pathway in melanoma. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2009, 22(4), 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakhova, O; Zingg, D; Schaefer, SM; et al. Sox10 promotes the formation and maintenance of giant congenital naevi and melanoma. Nat Cell Biol. 2012, 14(8), 882–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d'Ischia, M; Wakamatsu, K; Napolitano, A; et al. Melanins and melanogenesis: methods, standards, protocols. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2013, 26(5), 616–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haenssle, HA; Fink, C; Schneiderbauer, R; et al. Man against machine: diagnostic performance of a deep learning convolutional neural network for dermoscopic melanoma recognition in comparison to 58 dermatologists. Ann Oncol. 2018, 29(8), 1836–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haq, R; Shoag, J; Andreu-Perez, P; et al. Oncogenic BRAF regulates oxidative metabolism via PGC1α and MITF. Cancer Cell. 2013, 23(3), 302–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vazquez, F; Lim, JH; Chim, H; et al. PGC1α expression defines a subset of human melanoma tumors with increased mitochondrial capacity and resistance to oxidative stress. Cancer Cell. 2013, 23(3), 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, S; Wang, J; Gong, H; et al. PGC-1α-Coordinated Hypothalamic Antioxidant Defense Is Linked to SP1-LanCL1 Axis during High-Fat-Diet-Induced Obesity in Male Mice. Antioxidants (Basel) 2024, 13(2), 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, SM; Eccles, MR. Phenotype Switching and the Melanoma Microenvironment; Impact on Immunotherapy and Drug Resistance. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24(2), 1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goding, CR; Arnheiter, H. MITF-the first 25 years. Genes Dev. 2019, 33(15-16), 983–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, WH; Elder, DE; Guerry, D; Braitman, LE; Trock, BJ; Schultz, D; Synnestvedt, M; Halpern, AC. Model predicting survival in stage I melanoma based on tumor progression. J Natl Cancer Inst 1989, 81, 1893–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richtig, G; Richtig, E; Massone, C; Hofmann-Wellenhof, R. Analysis of clinical, dermoscopic and histopathological features of primary melanomas of patients with metastatic disease--a retrospective study at the Department of Dermatology, Medical University of Graz, 2000-2010. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2014, 28(12), 1776–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massone, C; Hofman-Wellenhof, R; Chiodi, S; Sola, S. Dermoscopic Criteria, Histopathological Correlates and Genetic Findings of Thin Melanoma on Non-Volar Skin. Genes (Basel) 2021, 12(8), 1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundararajan, S; Thida, AM; Yadlapati, S; et al. Metastatic Melanoma. StatPearls [Internet]. 17 Feb 2024. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470358/?utm.

- Lowe, L. Metastatic melanoma and rare melanoma variants: a review. Pathology 2023, 55(2), 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carey, AE; Weeraratna, AT. Entering the TiME machine: How age-related changes in the tumor immune microenvironment impact melanoma progression and therapy response. Pharmacol Ther. 2024, 262, 108698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wick, MR; Gru, AA. Metastatic melanoma: Pathologic characterization, current treatment, and complications of therapy. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2016, 33(4), 204–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, ML. Histopathologic and Molecular Diagnosis of Melanoma. Clin Plast Surg. 2021, 48(4), 587–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrov, LB; Nik-Zainal, S; Wedge, DC; et al. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature 2013, 500(7463), 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmons, C; Morris, Q; Harrigan, CF. Regional mutational signature ac-tivities in cancer genomes. PLoS Comput Biol. 2022, 18(12), e1010733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fröhlich, F; Ramelyte, E; Turko, P; et al. Clock-like Mutation Signature May Be Prognostic for Worse Survival Than Signatures of UV Damage in Cutaneous Melanoma. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15(15), 3818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maul, LV; Ramelyte, E; Dummer, R; Mangana, J. Management of metastatic melanoma with combinations including PD-1 inhibitors. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2025, 25(5), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinca, AC; Raicea, A; Szőke, AR; et al. Morphological aspects and therapeutic options in melanoma: a narrative review of the past decade. Rom J Morphol Embryol 2023, 64(2), 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, D. B. Updates to the management of cutaneous melanoma. JNCCN: Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2024, 22, e245015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodde, G; Albrecht, LJ; Schadendorf, D. Behandlung des metastasierten Melanoms – Update 2025 [Treatment of metastatic melanoma: update 2025]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 2025, 150(10), 562–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R; Zhang, X; Li, X; Wan, X. Circ_0016418 promotes melanoma development and glutamine catabolism by regulating the miR-605-5p/GLS axis. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2020, 13(7), 1791–1801. [Google Scholar]

- Castellani, G; Buccarelli, M; Arasi, MB; et al. BRAF Mutations in Melanoma: Biological Aspects, Therapeutic Implications, and Circulating Biomarkers. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15(16), 4026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaliq, M.; Fallahi-Sichani, M. Epigenetic Mechanisms of Escape from BRAF Oncogene Dependency. Cancers 2019, 11, 1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solit, D.; Rosen, N. Oncogenic RAF: A brief history of time. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2010, 23, 760–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menzer, C; Hassel, JC. Targeted Therapy for Melanomas Without BRAF V600 Mutations. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2022, 23(6), 831–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, A; Karapetyan, L; Kirkwood, JM. Immunotherapy in Melanoma: Recent Advances and Future Directions. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15(4), 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabău, A.-H.; Tinca, A.-C.; Niculescu, R.; Cocuz, I. G.; Cozac-Szöke, A. R.; Lazar, B. A.; Chiorean, D. M.; Budin, C. E.; Cotoi, O. S. Cancer Stem Cells in Melanoma: Drivers of Tumor Plasticity and Emerging Therapeutic Strategies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2025, 26(15), 7419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, X; Zhou, Y; Yu, Y; Zhang, M; Liu, J. The roles of cancer stem cells and therapeutic implications in melanoma. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1486680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerard, L; Gillet, JP. The uniqueness of ABCB5 as a full transporter ABCB5FL and a half-transporter-like ABCB5β. Cancer Drug Resist 2024, 7, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z; Starkuviene, V; Keese, M. The Differentiation and Regeneration Potential of ABCB5+ Mesenchymal Stem Cells: A Review and Clinical Perspectives. J Clin Med. 2025, 14(3), 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chartrain, M; Riond, J; Stennevin, A; et al. Melanoma chemotherapy leads to the selection of ABCB5-expressing cells. PLoS One 2012, 7(5), e36762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y; Ding, Q; Zhang, M; et al. miR-145 targets ABCB5 to regulate chemosensitivity in melanoma. Oncotarget 2016, 7(35), 57317–57328. [Google Scholar]

- Jilaveanu, LB; Aziz, SA; Kluger, HM. Chemotherapy and biologic therapies for melanoma: do they work? Clin Dermatol 2009, 27, 614–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, NY; Pendse, SS; Lapchak, PH; et al. Regulation of progenitor cell fusion by ABCB5 in human malignant melanoma. Cancer Res 2011, 71(4), 1274–83. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xiao, J.; Egger, M.E.; McMasters, K.M.; et al. Differential expression of ABCB5 in BRAF inhibitor-resistant melanoma cell lines. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straussman, R; et al. Tumour micro-environment elicits innate resistance to RAF inhibitors through HGF secretion. Nature 2012, 487(7408), 500–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perna, D; Karreth, FA; Rust, AG; Perez-Mancera, PA; Rashid, M; Iorio, F; Alifrangis, C; Arends, MJ; Bosenberg, MW; Bollag, G; Tuveson, DA; Adams, DJ. BRAF inhibitor resistance mediated by the AKT pathway in an oncogenic BRAF mouse melanoma model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015, 112(6), E536–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mühlbauer, D; Schatton, T; Schütte, U; et al. Expression of ABCB5 as a molecular marker for poor prognosis in melanoma. Journal of Investigative Dermatology 2016, 136(3), 666–676. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, J; Wang, J; Tang, B; et al. Expression and clinical significance of TYRP1, ABCB5, and MMP17 in sinonasal mucosal melanoma. Cancer Biomark. 2022, 35(3), 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, BJ; Schatton, T; Zhan, Q; et al. ABCB5 identifies a therapy-refractory tumor cell population in colorectal cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2011, 71(15), 5307–5316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kugimiya, N; Nishimoto, A; Hosoyama, T; et al. The c-MYC-ABCB5 axis plays a pivotal role in 5-fluorouracil resistance in human colon cancer cells. J Cell Mol Med. 2015, 19(7), 1569–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duvivier, L; Gillet, JP. Deciphering the roles of ABCB5 in normal and cancer cells. Trends Cancer 2022, 8(10), 795–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapanotti, MC; Cugini, E; Campione, E; et al. Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition Gene Signature in Circulating Melanoma Cells: Biological and Clinical Relevance. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24(14), 11792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusienicka, A; Bukowska-Strakova, K; Cieśla, M; et al. Heme Oxygenase-1 Has a Greater Effect on Melanoma Stem Cell Properties Than the Expression of Melanoma-Initiating Cell Markers. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23(7), 3596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerard, L; Duvivier, L; Fourrez, M; et al. Identification of two novel heterodimeric ABC transporters in melanoma: ABCB5β/B6 and ABCB5β/B9. J Biol Chem. 2024, 300(2), 105594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).