Submitted:

22 December 2025

Posted:

24 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

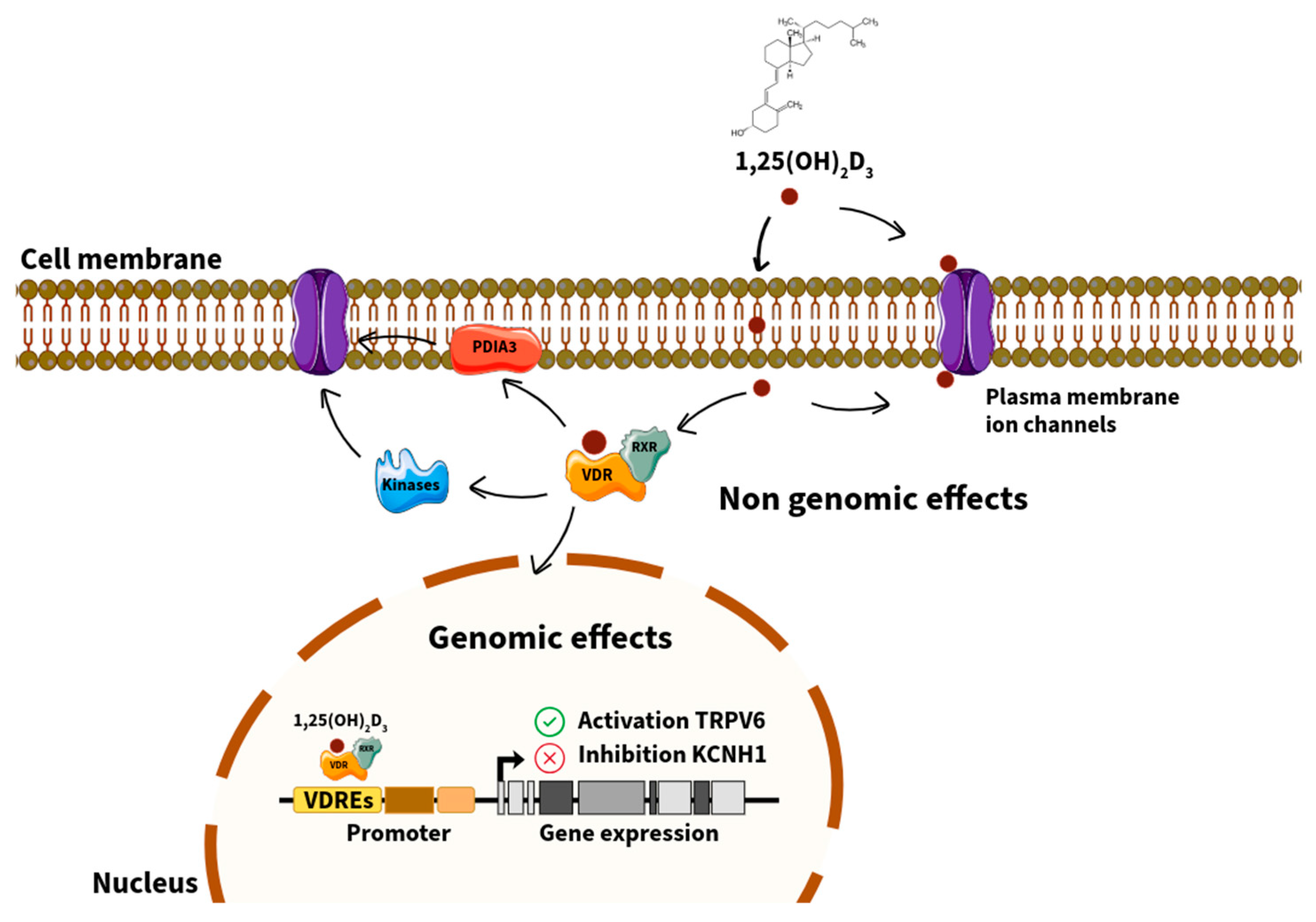

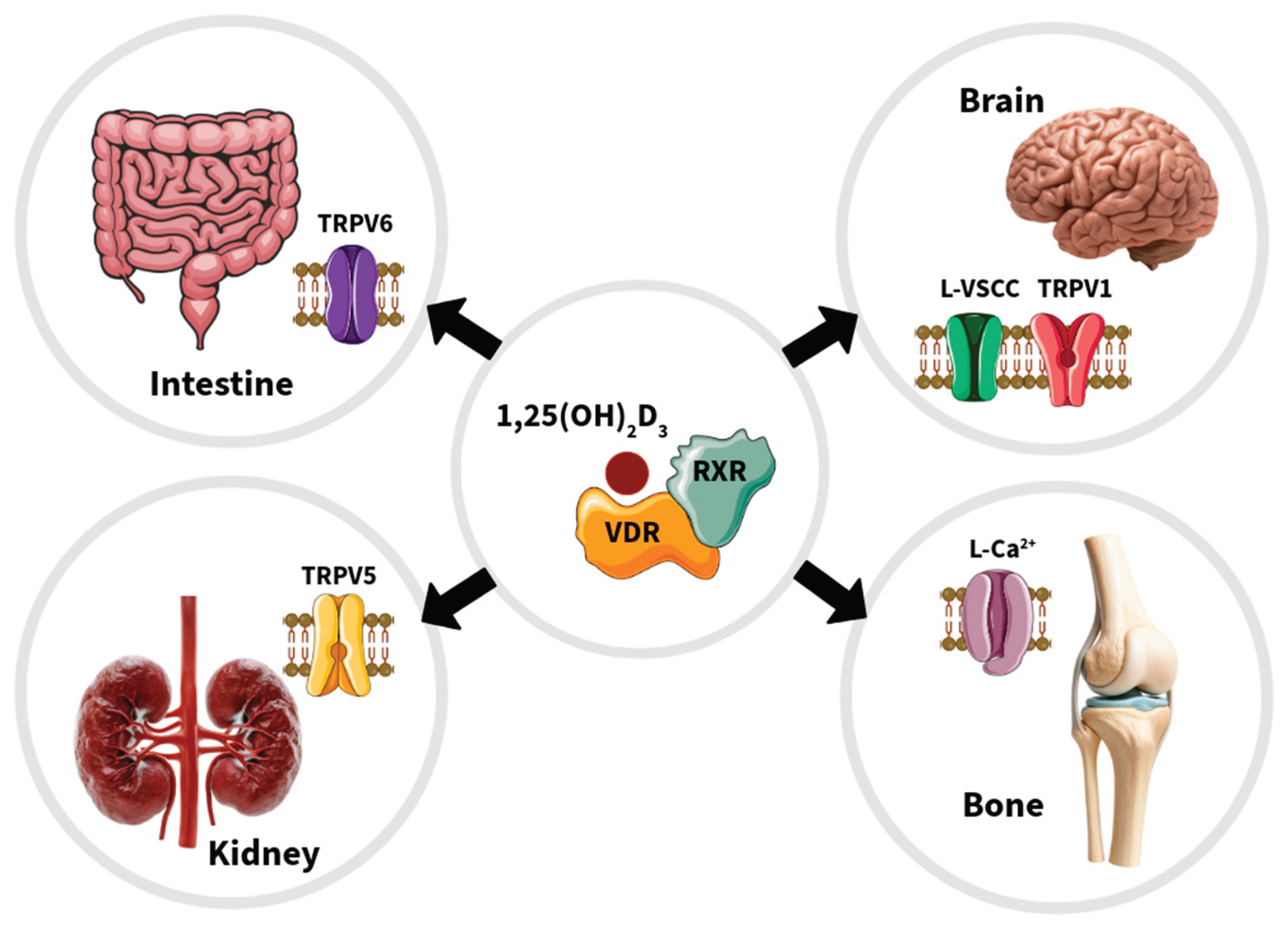

The vitamin D receptor (VDR) acts as both a nuclear transcription factor and a non-genomic mediator that regulates a broad spectrum of physiological processes beyond calcium and phosphate homeostasis. VDR plays an important role in the modulation of ion channels across multiple tissues, including osteoblasts, renal and intestinal epithelial cells, neurons, and vascular smooth muscle. These regulatory mechanisms encompass genomic actions through vitamin D response elements in target genes—such as TRPV5, TRPV6, KCNK3, and KCNH1—as well as rapid, non-genomic actions at the plasma membrane involving protein disulfide isomerase A3 and associated signaling cascades. VDR-mediated transcriptional control of calcium, potassium, and chloride channels contributes to the fine-tuning of cellular excitability, calcium transport, and mitochondrial function. Evidence also implicates VDR–ion channel crosstalk in various pathological contexts, including renal cell carcinoma, breast and cervical cancers, pulmonary arterial hypertension, and osteoporosis. Understanding the molecular interplay between VDR and ion channels provides new perspectives on the pleiotropic effects of vitamin D and offers promising therapeutic opportunities in oncology, cardiovascular disease, and skeletal disorders. This review synthesizes previous and current evidence on the genomic and non-genomic mechanisms underlying VDR–ion channel regulation and highlights novel frontiers in vitamin D signaling relevant to human health and disease.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. VDR: Genomic and Non-Genomic Mechanisms

2.1. The VDR Functions as Both a Nuclear Transcription Factor and a Non-Genomic Mediator

2.2. Structural Domains and Isoforms of VDR

2.3. Regulation by 1,25(OH)2D3 and Its Synthetic Analogs

2.4. Interactions with Co-Regulators and Membrane-Associated Signaling Proteins

3. VDR Signaling and Ion Channels: Mechanistic Insights

3.1. Transcriptional Regulation of Ion Channel Genes via VDREs

3.2. Indirect Modulation Through Second Messengers and Kinase Cascades

3.3. Epigenetic and Post-Transcriptional Regulation

4. Regulation of Ion Channel Function by VDR in Different Cellular Contexts

4.1. Osteoblast Cells

4.2. Intestinal and Kidney Cells

4.3. Neuron Cells

4.4. Ion Channels from the Plasma and Mitochondrial Membranes

5. Pathophysiological Relevance of VDR–Ion Channel Interactions

5.1. Cancer

5.2. Renal Cell Carcinoma (RCC)

5.3. Breast and Cervical Cancer

5.4. Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension

5.5. Osteoporosis

6. Conclusions and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 1,25(OH)2D3 | 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 |

| 25(OH)D3 | 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 |

| BMD | Bone mineral density |

| CYP | Cytochrome P450 |

| DRIP | Vitamin D receptor interacting protein |

| EAG | Ether-à-go-go |

| ER | Estrogen receptor |

| HAT | Histone acetyltransferase |

| KCN | Potassium channel |

| KO | knockout |

| LCA | Lithocholic acid |

| OPG | osteoprotegerin |

| PDIA3 | Protein disulfide isomerase A3 |

| PA | Pulmonary artery |

| PAH | Pulmonary artery hypertension |

| PASMC | Pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell |

| PKC | Protein kinase C |

| RANKL | Receptor activator of nuclear factor kB ligand |

| RCC | Renal cell carcinoma |

| RXR | Retinoic X receptor |

| SRC | Steroid receptor coactivator |

| TCM | Traditional Chinese medicine |

| TRP | Transient receptor potential |

| TRPV | Transient receptor potential vanilloid |

| VDR | Vitamin D receptor |

| VDRE | Vitamin D response element |

References

- Wolf, G. The Discovery of Vitamin D: The Contribution of Adolf Windaus. The Journal of Nutrition 2004, 134(6), 1299–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Duarte, RJ. Una vitamina que no es vitamina. Revista ¿Cómo ves? 2013, 174(15), 30–33. [Google Scholar]

- Voltan, G; Ceccato, F; Cannito, M; Camozzi, V; Ferrarese, M. Vitamin D: An Overview of Gene Regulation, Ranging from Metabolism to Genomic Effects. Genes 2023, 14(9), 1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanello, LP; Norman, A. 1α,25(OH) 2 Vitamin D 3 actions on ion channels in osteoblasts. Steroids 2006, 71(4), 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olszewska, AM; Zmijewski, MA. Genomic and non-genomic action of vitamin D on ion channels – Targeting mitochondria. Mitochondrion 2024, 77, 101891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcdonnell, DP; Mangelsdorf, DJ; Haussler, MR; O’Malley, BW; Pike, JW. Molecular cloning of complementary DNA encoding the avian receptor for vitamin D. Science 1987, 235(4793), 1214–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makishima, M; Whitfield, GK; Evans, RM; Xie, W; Haussler, MR; Domoto, H; et al. Vitamin D receptor as an intestinal bile acid sensor. Science 2002, 296(5571), 1313–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, CJ; Adams, JS; Bikle, DD; Black, DM; Demay, MB; Manson, JE; et al. The nonskeletal effects of vitamin D: an Endocrine Society scientific statement. Endocrine reviews 2012, 33(3), 456–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walters, MR. Newly identified actions of the vitamin D endocrine system. Endocrine Reviews 1992, 13(4), 719–764. [Google Scholar]

- Kurokawa, R; Glass, CK; Han, Z; Yu, VC; Naar, A; Silverman, S; et al. Differential orientations of the DNA-binding domain and carboxy-terminal dimerization interface regulate binding site selection by nuclear receptor heterodimers. Genes & Development 1993, 7(7b), 1423–1435. [Google Scholar]

- Donati, S; Falsetti, I; Brandi, ML; Miglietta, F; Iantomasi, T; Palmini, G; et al. Rapid Nontranscriptional Effects of Calcifediol and Calcitriol. Nutrients 2022, 14(6), 1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rochel, N; Wurtz, JM; Mitschler, A; Klaholz, B; Moras, D. The Crystal Structure of the Nuclear Receptor for Vitamin D Bound to Its Natural Ligand. Molecular Cell. 2000, 5(1), 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuno, H; Ikura, T; Morizono, D; Orita, I; Yamada, S; Shimizu, M; et al. Crystal structures of complexes of vitamin D receptor ligand-binding domain with lithocholic acid derivatives. Journal of Lipid Research 2013, 54(8), 2206–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rachez, C; Chang, CPB; Atkins, GB; Lazar, MA; Gamble, M; Freedman, LP. The DRIP complex and SRC-1/p160 coactivators share similar nuclear receptor binding determinants but constitute functionally distinct complexes. Molecular and Cellular Biology 2000, 20(8), 2718–2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, EM; Esteban, LM; Fong, C; Allison, SJ; Flanagan, JL; Kouzmenko, AP; et al. Vitamin D receptor B1 and exon 1d: functional and evolutionary analysis. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 2004, 89(1–5), 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban, LM; Fong, C; Amr, D; Cock, TA; Allison, SJ; Flanagan, JL; et al. Promoter-, cell-, and ligand-specific transactivation responses of the VDRB1 isoform. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2005, 334(1), 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebihara, K; Hasegawa, T; Masuhiro, Y; Kitamoto, T; Uematsu, Y; Ono, T; et al. Intron retention generates a novel isoform of the murine vitamin D receptor that acts in a dominant negative way on the vitamin D signaling pathway. Molecular and Cellular Biology 1996, 16(7), 3393–3400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gennari, L; Becherini, L; Falchetti, A; Masi, L; Massart, F; Brandi, ML. Genetics of osteoporosis: role of steroid hormone receptor gene polymorphisms. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 2002, 81(1), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grundberg, E; Brandstrom, H; Ljunggren, O; Ribom, E; Kindmark, A; Mallmin, H. Genetic variation in the human vitamin D receptor is associated with muscle strength, fat mass and body weight in Swedish women. European Journal of Endocrinology 2004, 150(3), 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howarth, DL; Law, SHW; Barnes, B; Hall, JM; Hinton, DE; Moore, L; et al. Paralogous Vitamin D Receptors in Teleosts: Transition of Nuclear Receptor Function. Endocrinology 2008, 149(5), 2411–2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umesono, K; Murakami, KK; Thompson, CC; Evans, RM. Direct repeats as selective response elements for the thyroid hormone, retinoic acid, and vitamin D 3 receptors. Cell 1991, 65(7), 1255–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thummel, KE; Brimer, C; Yasuda, K; Thottassery, J; Senn, T; Lin, Y; et al. Transcriptional control of intestinal cytochrome P-4503A by 1alpha,25-dihydroxy vitamin D3. Molecular Pharmacology 2001, 60(6), 1399–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubodera, N. A New Look at the Most Successful Prodrugs for Active Vitamin D (D Hormone): Alfacalcidol and Doxercalciferol. Molecules 2009, 14(10), 3869–3880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, T; Okano, T; Takeuchi, A; Nishii, Y; Kubodera, N; Tsugawa, N; et al. The binding properties, with blood proteins, and tissue distribution of 22-oxa-1 alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3, a noncalcemic analogue of 1 alpha, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3, in rats. Journal of biochemistry 1994, 115(3), 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchiyama, Y; Higuchi, Y; Takeda, S; Masaki, T; Shira-Ishi, A; Sato, K; et al. ED-71, a vitamin D analog, is a more potent inhibitor of bone resorption than alfacalcidol in an estrogen-deficient rat model of osteoporosis. Bone 2002, 30(4), 582–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, Y. Multifunctional and potent roles of the 3-hydroxypropoxy group provide eldecalcitol’s benefit in osteoporosis treatment. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 2013, 139, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, K; Takayama, H; Waku, K; Kittaka, A; Saito, N; Kishimoto, S; et al. Efficient synthesis of 2-modified 1alpha,25-dihydroxy-19-norvitamin D3 with Julia olefination: high potency in induction of differentiation on HL-60 cells. J Org Chem. 2003, 68(19), 7407–7415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, K; Ikushiro, S; Kamakura, M; Takano, M; Saito, N; Kittaka, A; et al. Human cytochrome P450-dependent differential metabolism among three 2α-substituted-1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 analogs. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 2012, 133, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y. Identification and characterization of noncalcemic, tissue-selective, nonsecosteroidal vitamin D receptor modulators. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2006, 116(4), 892–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, R; Honma, Y; Masuno, H; Kawana, K; Shimomura, I; Yamada, S; et al. Selective activation of vitamin D receptor by lithocholic acid acetate, a bile acid derivative. Journal of Lipid Research 2005, 46(1), 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishizawa, M; Matsunawa, M; Adachi, R; Uno, S; Ikeda, K; Masuno, H; et al. Lithocholic acid derivatives act as selective vitamin D receptor modulators without inducing hypercalcemia. Journal of Lipid Research 2008, 49(4), 763–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, H; Yoshihara, A; Kagechika, H; Hirata, N; Masuno, H; Kanda, Y; et al. Lithocholic Acid Derivatives as Potent Vitamin D Receptor Agonists. J Med Chem. 2020, 64(1), 516–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, TE; Zhou, J; Jenster, G; Allis, CD; O’Malley, BW; Mckenna, NJ; et al. Steroid receptor coactivator-1 is a histone acetyltransferase. Nature 1997, 389(6647), 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogryzko, VV; Schiltz, RL; Russanova, V; Howard, BH; Nakatani, Y. The Transcriptional Coactivators p300 and CBP Are Histone Acetyltransferases. Cell. 1996, 87(5), 953–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiba, N; Suldan, Z; Freedman, LP; Parvin, JD. Binding of Liganded Vitamin D Receptor to the Vitamin D Receptor Interacting Protein Coactivator Complex Induces Interaction with RNA Polymerase II Holoenzyme. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2000, 275(15), 10719–10722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savkur, RS; Bramlett, KS; Stayrook, KR; Nagpal, S; Burris, TP. Coactivation of the human vitamin D receptor by the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1 alpha. Molecular Pharmacology 2005, 68(2), 511–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baudino, TA; Kraichely, DM; Jefcoat, SC; Winchester, SK; Partridge, NC; Macdonald, PN. Isolation and Characterization of a Novel Coactivator Protein, NCoA-62, Involved in Vitamin D-mediated Transcription. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1998, 273(26), 16434–16441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagisawa, J; Miyazono, K; Masuhiro, Y; Toriyabe, T; Kato, S; Yanagi, Y; et al. Convergence of transforming growth factor-beta and vitamin D signaling pathways on SMAD transcriptional coactivators. Science 1999, 283(5406), 1317–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolón, RM; Castillo, AI; Jiménez-Lara, AM; Aranda, A. Association with Ets-1 causes ligand- and AF2-independent activation of nuclear receptors. Molecular and Cellular Biology 2000, 20(23), 8793–8802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hörlein, AJ; Heinzel, T; Glass, CK; Näär, AM; Kamei, Y; Söderström, M; et al. Ligand-independent repression by the thyroid hormone receptor mediated by a nuclear receptor co-repressor. Nature 1995, 377(6548), 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, JD; Evans, RM. A transcriptional co-repressor that interacts with nuclear hormone receptors. Nature 1995, 377(6548), 454–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perissi, V; Rosenfeld, MG; Jepsen, K; Glass, CK. Deconstructing repression: evolving models of co-repressor action. Nat Rev Genet. 2010, 11(2), 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z; Oda, Y; Chang, S; Bikle, DD. Hairless Suppresses Vitamin D Receptor Transactivation in Human Keratinocytes. Endocrinology 2005, 147(1), 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polly, P; Carlberg, C; Baniahmad, A; Moehren, U; Heinzel, T; Herdick, M. VDR-Alien: a novel, DNA-selective vitamin D3receptor-corepressor partnership. FASEB j 2000, 14(10), 1455–1463. [Google Scholar]

- Nemere, I.; Safford, S. E.; Rohe, B.; DeSouza, M. M.; Farach-Carson, M. C. Identification and characterization of 1,25D3-membrane-associated rapid response, steroid (1,25D3-MARRS) binding protein. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2004, 89-90(1-5), 281–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civitelli, R; Avioli, LV; Kim, YS; Hruska, KA; Gunsten, SL; Fujimori, A; et al. Nongenomic Activation of the Calcium Message System by Vitamin D Metabolites in Osteoblast-like Cells. Endocrinology 1990, 127(5), 2253–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemere, I; Boyan, BD; Farach-Carson, MC; Safford, SE; Rohe, B; Norman, AW; et al. Ribozyme knockdown functionally links a 1,25(OH)2D3 membrane binding protein (1,25D3-MARRS) and phosphate uptake in intestinal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004, 101(19), 7392–7397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemere, I; Garbi, N; Hammerling, G. Intestinal Cell Calcium Uptake and the Targeted Knockout Of the 1,25D3-MARRS Receptor/PDIA3/Erp57. The FASEB Journal 2010, 24(S1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y; Chen, J; Lee, CSD; Nizkorodov, A; Riemenschneider, K; Martin, D; et al. Disruption of Pdia3 gene results in bone abnormality and affects 1α,25-dihydroxy-vitamin D 3-induced rapid activation of PKC. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 2010, 121(1–2), 257–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyan, BD; Mckinney, N; Schwartz, Z; Sylvia, VL. Membrane actions of vitamin D metabolites 1alpha,25(OH)2D3 and 24R,25(OH)2D3 are retained in growth plate cartilage cells from vitamin D receptor knockout mice. J of Cellular Biochemistry 2003, 90(6), 1207–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J; Doroudi, M; Cheung, J; Grozier, AL; Schwartz, Z; Boyan, BD. Plasma membrane Pdia3 and VDR interact to elicit rapid responses to 1α,25(OH)2D3. Cellular Signalling 2013, 25(12), 2362–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J; Witonsky, D; Sprague, E; Alleyne, D; Bielski, MC; Lawrence, KM; et al. Genomic and epigenomic active vitamin D responses in human colonic organoids. Physiological Genomics 2021, 53(6), 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okano, T; Tsugawa, N; Morishita, A; Kato, S. Regulation of gene expression of epithelial calcium channels in intestine and kidney of mice by 1 α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D 3. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 2004, 89(1–5), 335–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, MB; Watanuki, M; Pike, JW; Shevde, NK; Kim, S. The Human Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid Type 6 Distal Promoter Contains Multiple Vitamin D Receptor Binding Sites that Mediate Activation by 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 in Intestinal Cells. Molecular Endocrinology 2006, 20(6), 1447–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, K; Erben, RG; Rump, A; Adamski, J. Gene Structure and Regulation of the Murine Epithelial Calcium Channels ECaC1 and 2. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2001, 289(5), 1287–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cromphaut, SJ; Van Herck, E; Collen, D; Dewerchin, M; Bouillon, R; Stockmans, I; et al. Duodenal calcium absorption in vitamin D receptor-knockout mice: functional and molecular aspects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2001, 98(23), 13324–13329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y; Peng, X; Porta, A; Takanaga, H; Peng, JB; Hediger, MA; et al. Calcium transporter 1 and epithelial calcium channel messenger ribonucleic acid are differentially regulated by 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3 in the intestine and kidney of mice. Endocrinology 2003, 144(9), 3885–3894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taketani, Y; Segawa, H; Chikamori, M; Morita, K; Tanaka, K; Kido, S; et al. Regulation of Type II Renal Na+-dependent Inorganic Phosphate Transporters by 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3: IDENTIFICATION OF A VITAMIN D-RESPONSIVE ELEMENT IN THE HUMAN NAPI-3 GENE. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1998, 273(23), 14575–14581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claro Da Silva, T; Hiller, C; Gai, Z; Kullak-Ublick, GA. Vitamin D3 transactivates the zinc and manganese transporter SLC30A10 via the Vitamin D receptor. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 2016, 163, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, TR; Higuchi, S; Bertaggia, E; Hung, A; Shanmugarajah, N; Guilz, NC; et al. Bile acid composition regulates the manganese transporter Slc30a10 in intestine. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2020, 295(35), 12545–12558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajibade, DV; Dhawan, P; Fechner, AJ; Meyer, MB; Pike, JW; Christakos, S. Evidence for a Role of Prolactin in Calcium Homeostasis: Regulation of Intestinal Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid Type 6, Intestinal Calcium Absorption, and the 25-Hydroxyvitamin D3 1α Hydroxylase Gene by Prolactin. Endocrinology 2010, 151(7), 2974–2984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, AI; Jimenez-Lara, AM; Tolon, RM; Aranda, A. Synergistic activation of the prolactin promoter by vitamin D receptor and GHF-1: role of the coactivators, CREB-binding protein and steroid hormone receptor coactivator-1 (SRC-1). Molecular Endocrinology 1999, 13(7), 1141–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishizawa, M; Akagi, D; Yamamoto, J; Makishima, M. 1α,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 enhances TRPV6 transcription through p38 MAPK activation and GADD45 expression. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 2017, 172, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X; Pramanik, R; Wang, J; Schultz, RM; Maitra, RK; Han, J; et al. The p38 and JNK Pathways Cooperate to trans-Activate Vitamin D Receptor via c-Jun/AP-1 and Sensitize Human Breast Cancer Cells to Vitamin D3-induced Growth Inhibition. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2002, 277(29), 25884–25892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurutka, PW; Hsieh, JC; Macdonald, PN; Terpening, CM; Haussler, CA; Haussler, MR; et al. Phosphorylation of serine 208 in the human vitamin D receptor. The predominant amino acid phosphorylated by casein kinase II, in vitro, and identification as a significant phosphorylation site in intact cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1993, 268(9), 6791–6799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriagada, G; Paredes, R; Olate, J; Van Wijnen, A; Lian, JB; Stein, GS; et al. Phosphorylation at serine 208 of the 1α,25-dihydroxy Vitamin D3 receptor modulates the interaction with transcriptional coactivators. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 2007, 103(3–5), 425–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, HJ; Messing, E; Sheu, TJ; Yasmin-Karim, S; Hsu, JW; Bao, BY; et al. A Positive Feedback Signaling Loop between ATM and the Vitamin D Receptor Is Critical for Cancer Chemoprevention by Vitamin D. Cancer Research 2012, 72(4), 958–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, JC; Samuels, DS; Haussler, CA; Terpening, CM; Haussler, MR; Jurutka, PW; et al. Human vitamin D receptor is selectively phosphorylated by protein kinase C on serine 51, a residue crucial to its trans-activation function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1991, 88(20), 9315–9319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, JC; Jurutka, PW; Nakajima, S; Galligan, MA; Haussler, CA; Shimizu, Y; et al. Phosphorylation of the human vitamin D receptor by protein kinase C. Biochemical and functional evaluation of the serine 51 recognition site. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1993, 268(20), 15118–15126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurutka, PW; Hsieh, JC; Haussler, MR. Phosphorylation of the Human 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 Receptor by cAMP-Dependent Protein-Kinase, In Vitro, and in Transfected COS-7 Cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 1993, 191(3), 1089–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, JC; Dang, HTL; Galligan, MA; Whitfield, GK; Haussler, CA; Jurutka, PW; et al. Phosphorylation of human vitamin D receptor serine-182 by PKA suppresses 1,25(OH)2D3-dependent transactivation. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2004, 324(2), 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khattar, V; Wang, L; Peng, JB. Calcium selective channel TRPV6: Structure, function, and implications in health and disease. Gene 2022, 817, 146192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Cromphaut, S; Dijcks, F; Ederveen, A; Carmeliet, G; Stockmans, I; Rummens, K; et al. Intestinal calcium transporter genes are upregulated by estrogens and the reproductive cycle through vitamin D receptor-independent mechanisms. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research 2003, 18(10), 1725–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, MH; Lee, GS; Jung, EM; Choi, KC; Jeung, EB. The negative effect of dexamethasone on calcium-processing gene expressions is associated with a glucocorticoid-induced calcium-absorbing disorder. Life Sciences 2009, 85(3–4), 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, J; Choi, JM; Yoshidomi, T; Sato, R; Yashiro, T. Quercetin Enhances VDR Activity, Leading to Stimulation of Its Target Gene Expression in Caco-2 Cells. JNSV 2010, 56(5), 326–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukushima, A; Aizaki, Y; Sakuma, K. Short-Chain Fatty Acids Induce Intestinal Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid Type 6 Expression in Rats and Caco-2 Cells. The Journal of Nutrition 2009, 139(1), 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sopjani, M; Kunert, A; Klaus, F; Föller, M; Lang, F; Laufer, J; et al. Regulation of the Ca2+ Channel TRPV6 by the Kinases SGK1, PKB/Akt, and PIKfyve. J Membrane Biol. 2009, 233(1–3), 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X; Wu, S; Guo, H. Active Vitamin D and Vitamin D Receptor Help Prevent High Glucose Induced Oxidative Stress of Renal Tubular Cells via AKT/UCP2 Signaling Pathway. BioMed Research International 2019, 2019(9), 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuyama, H; Macdonald, PN. Proteasome-mediated degradation of the vitamin D receptor (VDR) and a putative role for SUG1 interaction with the AF-2 domain of VDR. J Cell Biochem. 1998, 71(3), 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Y; Hong, Y; Zong, H; Wang, Y; Zou, W; Yang, J; et al. CDK11 p58 represses vitamin D receptor-mediated transcriptional activation through promoting its ubiquitin–proteasome degradation. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2009, 386(3), 493–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W; Na, T; Wu, G; Jing, H; Peng, JB. Down-regulation of Intestinal Apical Calcium Entry Channel TRPV6 by Ubiquitin E3 Ligase Nedd4-2. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2010, 285(47), 36586–36596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohri, T; Takagi, S; Yokoi, T; Nakajima, M; Komagata, S. MicroRNA regulates human vitamin D receptor. Intl Journal of Cancer 2009, 125(6), 1328–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F; Du, Y; Shi, Y; Ma, Y; Zhang, A. 1α,25-DihydroxyvitaminD3 prevents the differentiation of human lung fibroblasts via microRNA-27b targeting the vitaminD receptor. International Journal of Molecular Medicine 2015, 36(4), 967–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jena, S; Lee, WP; Doherty, D; Thompson, PD. PIAS4 represses vitamin D receptor-mediated signaling and acts as an E3-SUMO ligase towards vitamin D receptor. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 2012, 132(1–2), 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, WP; Thompson, PD; Lemau, J; Jena, S; Furmick, J; Schimdt, J; et al. Sentrin/SUMO Specific Proteases as Novel Tissue-Selective Modulators of Vitamin D Receptor-Mediated Signaling. PLoS ONE 2014, 9(2), e89506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chesnoy-Marchais, D; Fritsch, J. Voltage-gated sodium and calcium currents in rat osteoblasts. The Journal of Physiology 1988, 398(1), 291–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosling, M; Poyner, DR; Smith, JW. Characterization of a volume-sensitive chloride current in rat osteoblast-like (ROS 17/2.8) cells. The Journal of Physiology 1995, 485 Pt 3)(3, 671–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caffrey, JM; Farach-Carson, MC. Vitamin D3 Metabolites Modulate Dihydropyridine-sensitive Calcium Currents in Clonal Rat Osteosarcoma Cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1989, 264(34), 20265–20274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanello, LP; Norman, AW. Stimulation by 1α,25(OH)2-Vitamin D3 of Whole Cell Chloride Currents in Osteoblastic ROS 17/2.8 Cells: A STRUCTURE-FUNCTION STUDY. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1997, 272(36), 22617–22622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanello, LP; Norman, AW. Rapid modulation of osteoblast ion channel responses by 1alpha,25(OH)2-vitamin D3 requires the presence of a functional vitamin D nuclear receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004, 101(6), 1589–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feher, JJ. Facilitated calcium diffusion by intestinal calcium-binding protein. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology 1983, 244(3), C303–C307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasserman, RH. Intestinal absorption of calcium and phosphorus. Federation proceedings 1981, 40(1), 68–72. [Google Scholar]

- Den Dekker, E; Hoenderop, JGJ; Nilius, B; Bindels, RJM. The epithelial calcium channels, TRPV5 & TRPV6: from identification towards regulation. Cell Calcium 2003, 33(5–6), 497–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomilin, VN; Cherezova, AL; Negulyaev, YA; Semenova, SB. TRPV5/V6 Channels Mediate Ca(2+) Influx in Jurkat T Cells Under the Control of Extracellular pH. J of Cellular Biochemistry 2015, 117(1), 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleet, JC; Eksir, F; Hance, KW; Wood, RJ. Vitamin D-inducible calcium transport and gene expression in three Caco-2 cell lines. American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology 2002, 283(3), G618–G625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, RJ; Taparia, S; Tchack, L. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 increases the expression of the CaT1 epithelial calcium channel in the Caco-2 human intestinal cell line. BMC Physiol. 2001, 1(1), 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouillon, R; Carmeliet, G; Van Cromphaut, S. Intestinal calcium absorption: Molecular vitamin D mediated mechanisms. J of Cellular Biochemistry 2003, 88(2), 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubis, AM; Piwowar, A. The new insight on the regulatory role of the vitamin D3 in metabolic pathways characteristic for cancerogenesis and neurodegenerative diseases. Ageing Research Reviews 2015, 24 Pt B, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, LD; Porter, NM; Landfield, PW; Chen, KC; Thibault, V; Langub, MC. Vitamin D Hormone Confers Neuroprotection in Parallel with Downregulation of L-Type Calcium Channel Expression in Hippocampal Neurons. J Neurosci 2001, 21(1), 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caterina, MJ; Tominaga, M; Julius, D; Rosen, TA; Schumacher, MA; Levine, JD. The capsaicin receptor: a heat-activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Nature 1997, 389(6653), 816–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, LY; Gu, Q. Role of TRPV1 in inflammation-induced airway hypersensitivity. Current Opinion in Pharmacology 2009, 9(3), 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertin, S; To, K; Gwack, Y; Stanwood, SR; Dong, H; Touma, R; et al. The ion channel TRPV1 regulates the activation and proinflammatory properties of CD4+ T cells. Nat Immunol 2014, 15(11), 1055–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, W; Philippaert, K; Soni, S; Panigrahi, R; Kelly, R; Light, PE; et al. Vitamin D is an endogenous partial agonist of the transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 channel. The Journal of Physiology 2020, 598(19), 4321–4338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, W; Johnson, J; Kalyaanamoorthy, S; Light, P. TRPV1 channels as a newly identified target for vitamin D. Channels 2021, 15(1), 360–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olszewska, AM; Sieradzan, AK; Bednarczyk, P; Szewczyk, A; Żmijewski, MA. Mitochondrial potassium channels: A novel calcitriol target. Cell Mol Biol Lett 2022, 27(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeb, KK; Johnson, CS; Trump, DL. Vitamin D signalling pathways in cancer: potential for anticancer therapeutics. Nat Rev Cancer 2007, 7(9), 684–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strzykalska-Augustyniak, A; Psurski, M; Zachary, H; Filip-Psurska, B; Kłopotowska, D; Milczarek, M; et al. Calcitriol and Tacalcitol Modulate Th17 Differentiation Through Osteopontin Receptors: Age-Dependent Insights from a Mouse Breast Cancer Model. ImmunoTargets and Therapy 2025, 14(7). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Duarte, RJ; Díaz, L; Hidalgo-Miranda, A; Avila, E; Romero-Córdoba, S; Cázares-Ordoñez, V; et al. Calcitriol increases Dicer expression and modifies the microRNAs signature in SiHa cervical cancer cells. Biochem Cell Biol. 2015, 93(4), 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Duarte, RJ; Larrea, F; Avila, E; Cázares-Ordoñez, V; Díaz, L; Ortíz, V. The expression of RNA helicase DDX5 is transcriptionally upregulated by calcitriol through a vitamin D response element in the proximal promoter in SiHa cervical cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2015, 410(1–2), 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller, D; Peeters, P; Olsen, A; Katzke, V; Tumino, R; Palli, D; et al. Circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 in relation to renal cell carcinoma incidence and survival in the EPIC cohort. American Journal of Epidemiology 2014, 180(8), 810–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller, DC; Janout, V; Midttun, Ø; Zaridze, D; Brennan, P; Scelo, G; et al. Circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 and survival after diagnosis with kidney cancer. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 2015, 24(8), 1277–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomberg Jensen, M; Andersen, CB; Nielsen, JE; Bagi, P; Jørgensen, A; Juul, A; et al. Expression of the vitamin D receptor, 25-hydroxylases, 1α-hydroxylase and 24-hydroxylase in the human kidney and renal clear cell cancer. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 2010, 121(1–2), 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obara, W; Konda, R; Akasaka, S; Nakamura, S; Sugawara, A; Fujioka, T. Prognostic Significance of Vitamin D Receptor and Retinoid X Receptor Expression in Renal Cell Carcinoma. Journal of Urology 2007, 178(4), 1497–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoenderop, JGJ; Mu[Combining Diaeresis]Ller, D; Willems, PHGM; Hartog, A; Van Der Kemp, AWCM; Sweep, F; et al. Calcitriol controls the epithelial calcium channel in kidney. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN 2001, 12(7), 1342–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y; Huang, H; He, X; Wu, Y; Liu, X; Zhang, F; et al. Vitamin D receptor suppresses proliferation and metastasis in renal cell carcinoma cell lines via regulating the expression of the epithelial Ca2+ channel TRPV5. PLoS ONE 2018, 13(4), e0195844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stachowicz-Suhs, M; Łabędź, N; Milczarek, M; Kłopotowska, D; Filip-Psurska, B; Maciejczyk, A; et al. Vitamin D3 reduces the expression of M1 and M2 macrophage markers in breast cancer patients. Sci Rep. 2024, 14(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oeggerli, M; Güth, U; Kunzelmann, K; Sauter, G; Zlobec, I; Tian, Y; et al. Role of KCNMA1 in Breast Cancer. PLoS ONE 2012, 7(8), e41664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatun, A; Kito, H; Fujimoto, M; Niwa, S; Ohya, S; Suzuki, T. Down-Regulation of Ca2+-Activated K+ Channel KCa1.1 in Human Breast Cancer MDA-MB-453 Cells Treated with Vitamin D Receptor Agonists. IJMS 2016, 17(12), 2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Becerra, R; Díaz, L; Camacho, J; Barrera, D; Ordaz-Rosado, D; Morales, A; et al. Calcitriol inhibits Ether-à go-go potassium channel expression and cell proliferation in human breast cancer cells. Experimental Cell Research 2009, 316(3), 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avila, E; García-Becerra, R; Rodríguez-Rasgado, JA; et al. Calcitriol down-regulates human ether a go-go 1 potassium channel expression in cervical cancer cells. Anticancer Research 2010, 30(7), 2667–2672. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cázares-Ordoñez, V; Pardo, LA. Kv10.1 potassium channel: from the brain to the tumors. Biochem Cell Biol. 2017, 95(5), 531–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, LA; Stühmer, W; Camacho, J; Brüggemann, A. Cell Cycle–related Changes in the Conducting Properties of r-eag K+ Channels. The Journal of Cell Biology 1998, 143(3), 767–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pardo, LA. Oncogenic potential of EAG K(+) channels. The EMBO Journal 1999, 18(20), 5540–5547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toplak, Ž; Hendrickx, LA; Abdelaziz, R; Shi, X; Peigneur, S; Tomašič, T; Tytgat, J; Peterlin-Mašič, L; Pardo, LA. Overcoming challenges of HERG potassium channel liability through rational design: Eag1 inhibitors for cancer treatment. Med Res Rev. 2022, 42(1), 183–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cázares-Ordoñez, V; Avila, E; Larrea, F; Ishizawa, M; Ortíz, V; Díaz, L; et al. A cis-acting element in the promoter of human ether à go-go 1 potassium channel gene mediates repression by calcitriol in human cervical cancer cells. Biochem Cell Biol. 2014, 93(1), 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callejo, M; Mondejar-Parreño, G; Esquivel-Ruiz, S; Olivencia, MA; Moreno, L; Blanco, I; et al. Total, Bioavailable, and Free Vitamin D Levels and Their Prognostic Value in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. JCM 2020, 9(2), 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, H; Kataoka, M; Isobe, S; Yamamoto, T; Shirakawa, K; Endo, J; et al. Therapeutic impact of dietary vitamin D supplementation for preventing right ventricular remodeling and improving survival in pulmonary hypertension. PLoS ONE 2017, 12(7), e0180615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callejo, M; Serrano-Navarro, A; Perez-Vizcaino, F; Cogolludo, A; Olivencia, MA; Morrell, N; et al. Vitamin D receptor and its antiproliferative effect in human pulmonary arterial hypertension. Sci Rep. 2024, 14(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, J; Zhao, H; Li, JB; Cao, W; Hu, B; Fu, L. Low Vitamin D Status Is Associated with Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. The Journal of Immunology 2019, 203(6), 1428–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzilas, V; Bouros, E; Barbayianni, I; Karampitsakos, T; Kourtidou, S; Ntassiou, M; et al. Vitamin D prevents experimental lung fibrosis and predicts survival in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Pulmonary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2019, 55, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milani, C; Katayama, MLH; De Lyra, EC; Welsh, J; Campos, LT; Brentani, MM; et al. Transcriptional effects of 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3 physiological and supra-physiological concentrations in breast cancer organotypic culture. BMC Cancer 2013, 13(8). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shalhoub, V; Shatzen, EM; Haas, K; Pan, Z; Young, J; Martin, D; et al. Chondro/osteoblastic and cardiovascular gene modulation in human artery smooth muscle cells that calcify in the presence of phosphate and calcitriol or paricalcitol. J of Cellular Biochemistry 2010, 111(4), 911–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, LT; Brentani, H; Roela, RA; Katayama, MLH; Lima, L; Rolim, CF; et al. Differences in transcriptional effects of 1α,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3 on fibroblasts associated to breast carcinomas and from paired normal breast tissues. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 2012, 133(1), 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callejo, M; Moreno, L; Barreira, B; Olivencia, MA; Morales-Cano, D; Mondejar-Parreño, G; et al. Vitamin D deficiency downregulates TASK-1 channels and induces pulmonary vascular dysfunction. American Journal of Physiology-Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology 2020, 319(4), L627–L640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antigny, F; Humbert, M; Ruffenach, G; Tremblay, E; Hautefort, A; Fadel, E; et al. Potassium Channel Subfamily K Member 3 (KCNK3) Contributes to the Development of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Circulation 2016, 133(14), 1371–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurney, AM; Kempsill, FEJ; Tate, RJ; Osipenko, ON; Macmillan, D; Mcfarlane, KM. Two-pore domain K channel, TASK-1, in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Circulation Research 2003, 93(10), 957–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, M; Humbert, M; Michel, JB; Hautefort, A; Mendes-Ferreira, P; Kotsimbos, T; et al. Loss of KCNK3 is a hallmark of RV hypertrophy/dysfunction associated with pulmonary hypertension. Cardiovascular Research 2018, 114(6), 880–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, XJ; Wang, J; Juhaszova, M; Gaine, SP; Rubin, LJ. Attenuated K + channel gene transcription in primary pulmonary hypertension. The Lancet 1998, 351(9104), 726–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondejar-Parreño, G; Perez-Vizcaino, F; Cogolludo, A. Kv7 Channels in Lung Diseases. Front Physiol 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrese, V; Stott, JB; Greenwood, IA. KCNQ-Encoded Potassium Channels as Therapeutic Targets. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2017, 58(1), 625–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackie, AR; Byron, KL. Cardiovascular KCNQ (Kv7) potassium channels: physiological regulators and new targets for therapeutic intervention. Molecular Pharmacology 2008, 74(5), 1171–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, TT; Lallemant, B; Nagai, Y; Konstorum, A; Tavera-Mendoza, LE; Libby, E; et al. Large-Scale in Silico and Microarray-Based Identification of Direct 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 Target Genes. Molecular Endocrinology 2005, 19(11), 2685–2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivencia, MA; Paternoster, E; Villegas-Esguevillas, M; Sancho, M; Adão, R; Larriba, MJ; et al. Vitamin D Receptor Deficiency Upregulates Pulmonary Artery Kv7 Channel Activity. IJMS 2023, 24(15), 12350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, A; Rajawat, J. Skeletal Aging and Osteoporosis: Mechanisms and Therapeutics. IJMS 2021, 22(7), 3553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salari, N; Darvishi, N; Bartina, Y; Larti, M; Kiaei, A; Hemmati, M; et al. Global prevalence of osteoporosis among the world older adults: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res 2021, 16(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakkalakal, DA. Alcohol-Induced Bone Loss and Deficient Bone Repair; Clinical &: Alcoholism; Experimental Research, 1 Dec 2005; Volume 29, 12, pp. 2077–2090. [Google Scholar]

- Pedrera-Canal, M; Moran, JM; Vera, V; Roncero-Martin, R; Lavado-Garcia, JM; Aliaga, I; et al. Lack of Influence of Vitamin D Receptor BsmI (rs1544410) Polymorphism on the Rate of Bone Loss in a Cohort of Postmenopausal Spanish Women Affected by Osteoporosis and Followed for Five Years. PLoS ONE 2015, 10(9), e0138606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, CH. Osteoporosis: From Molecular Mechanisms to Therapies. IJMS 2020, 21(3), 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, Y; Yang, S; Chen, X; Sun, M; Yang, N. The role of calcium channels in osteoporosis and their therapeutic potential. Front Endocrinol 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, XH; Yang, TL; Papasian, CJ; Deng, HW; Dong, SS; Guo, Y; et al. Molecular genetic studies of gene identification for osteoporosis: the 2009 update. Endocrine Reviews 2010, 31(4), 447–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y; Zhao, P; Jiang, B; Liu, K; Zhang, L; Wang, H; et al. Modulation of the vitamin D/vitamin D receptor system in osteoporosis pathogenesis: insights and therapeutic approaches. J Orthop Surg Res. 2023, 18(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamichi, Y; Kato, S; Udagawa, N; Yamamoto, Y; Takahashi, N; Mizoguchi, T; et al. VDR in Osteoblast-Lineage Cells Primarily Mediates Vitamin D Treatment-Induced Increase in Bone Mass by Suppressing Bone Resorption. J of Bone & Mineral Res. 2017, 32(6), 1297–1308. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, Y; Yoshizawa, T; Fukuda, T; et al. Vitamin D receptor in osteoblasts is a negative regulator of bone mass control. Endocrinology 2013, 154(3), 1008–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, MGA; Wani, KA; Abdi, S; Alnaami, AM; Hussain, SD; Mohammed, AK; et al. Vitamin D Receptor Gene Variants Susceptible to Osteoporosis in Arab Post-Menopausal Women. CIMB 2021, 43(3), 1325–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, LL; Zhang, C; Zhang, Y; Ma, F; Guan, Y. Associations between polymorphisms in VDR gene and the risk of osteoporosis: a meta-analysis. Archives of Physiology and Biochemistry ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print). 2020, 1637–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. TRP Channel Classification. Advances in experimental medicine and biology 2017, 976, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- He, LH; Yang, HQ; Liu, M; Zhao, L; Xiao, E; Zhang, T; et al. TRPV1 deletion impaired fracture healing and inhibited osteoclast and osteoblast differentiation. Sci Rep. 2017, 7(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F; Yang, YO; Chen, A; Ye, T; Ni, B. Knockout of TRPV6 Causes Osteopenia in Mice by Increasing Osteoclastic Differentiation and Activity. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2014, 33(3), 796–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamoux, E; Bisson, M; Payet, MD; Roux, S. TRPV-5 Mediates a Receptor Activator of NF-κB (RANK) Ligand-induced Increase in Cytosolic Ca2+ in Human Osteoclasts and Down-regulates Bone Resorption. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2010, 285(33), 25354–25362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Eerden, BCJ; Van Der Eerden, BCJ; Van Der Eerden, BCJ; Uitterlinden, AG; Hoenderop, JGJ; Schoenmaker, T; et al. The epithelial Ca2+ channel TRPV5 is essential for proper osteoclastic bone resorption. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005, 102(48), 17507–17512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J; Zhu, L; Zhou, Z; Song, T; Yang, L; Yan, X; et al. The calcium channel TRPV6 is a novel regulator of RANKL-induced osteoclastic differentiation and bone absorption activity through the IGF–PI3K–AKT pathway. Cell Proliferation 2020, 54(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, M; Akintibu, AM; Yan, H; Oduro, PK. Modulation of the vitamin D receptor by traditional Chinese medicines and bioactive compounds: potential therapeutic applications in VDR-dependent diseases. Front Pharmacol. 2024, 15(9). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, PC; Siu, WS. Herbal Treatment for Osteoporosis: A Current Review. Journal of Traditional and Complementary Medicine 2013, 3(2), 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, SJ; Wang, YQ; Jiang, YC; Hu, NW; Dong, QP; Xu, WM; et al. Bu-Shen-Jian-Pi-Yi-Qi Therapy Prevents Alcohol-Induced Osteoporosis in Rats. American journal of therapeutics 2016, 23(5), e1135–e1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Ion Channel/ Protein |

Type of Regulation (Genomic/Non-genomic) | Functional/Physiological Effect | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| TRPV5 | Genomic. Vitamin D response elements (VDREs) present in TRPV5 promoter region; transcriptional regulation by VDR. | Maintains calcium transport in renal cells; VDR acts as a tumor suppressor in renal cell carcinoma by modulating TRPV5 to inhibit proliferation, migration, and invasion. | Van Cromphaut et al., 2001; Hoenderop et al., 2001; Chen et al., 2018. |

| KCa1.1 (BKCa, KCNMA1) | Genomic. Transcriptional repression mediated by VDR activation. | Decreases depolarization responses and inhibits cell proliferation in breast cancer cells. | Khatun et al., 2016; Oeggerli et al., 2012. |

| Kv10.1 | Genomic. Negative VDRE (E-box) identified in KCNH1 promoter. | Reduces potassium channel expression, leading to lower proliferation and oncogenic potential in breast and cervical cancer cells. | Avila et al., 2010; García-Becerra et al., 2010; Cázares-Ordoñez et al., 2015; Cázares-Ordoñez & Pardo, 2017. |

| Ion Channel/ Protein |

Type of Regulation (Genomic/Non-genomic) | Functional/Physiological Effect | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| TASK-1 | Genomic. VDRE identified in promoter. | Improves repolarization; partial antiproliferative effect. However, KCNK3 inhibition does not block 1,25(OH)2D3-induced antiproliferation. | Callejo et al., 2020; Milani et al., 2013; Shalhoub et al., 2010; Campos et al., 2013; Callejo et al., 2024. |

| Kv7 regulatory subunit 4 | Genomic. VDRE present in KCNE4 promoter | Overexpression enhances Kv7 activity and K⁺ currents, increasing PASMC relaxation. | Olivencia et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2005. |

| Kv7.x (KCNQ1, KCNQ3, Kv7.1–Kv7.5) | Genomic. Predicted VDREs | Activation causes K⁺ efflux, hyperpolarization, and relaxation with antiproliferative effects in PASMCs. | Wang et al., 2005; Barrese et al., 2018; Mondejar-Parreño et al., 2020; Mackie & Byron, 2008. |

| Kv1.5 | Non-genomic/indirect (no VDRE reported) | Loss of Kv1.5 currents favors depolarization and PASMC proliferation. | Antigny et al., 2016; Gurney et al., 2003; Lambert et al., 2018; Yuan et al., 1997. |

| TASK-1/K2P (two-pore domain K⁺ channels) | Genomic. VDRE present in KCNK3 promoter | Regulates pulmonary arterial tone and PASMC proliferation. | Callejo et al., 2020; Tanaka et al., 2017. |

| Ion Channel/ Protein |

Type of Regulation (Genomic/Non-genomic) | Functional/Physiological Effect | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| TRPV1 | Non-genomic/indirect. Ca²⁺-mediated signaling. | Increases osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption via Ca²⁺ influx. | He et al., 2017. |

| TRPV5 | Genomic. VDRE present in promoter; transcriptional activation by VDR. | Controls osteoclast size and Ca²⁺ transport; deficiency reduces calcium reabsorption and bone mineralization. | Chen et al., 2014; van der Eerden et al., 2005. |

| TRPV6 | Genomic. VDRE-dependent regulation. | Reduces osteoclast activity; TRPV6 knockdown increases bone resorption. | Chamoux et al., 2010; Ma et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2014. |

| TRP Channel Family (TRPC, TRPV, TRPM, TRPA, TRPML) | Mixed genomic and non-genomic. | Regulate Ca²⁺ influx, osteoclast differentiation, and osteocyte signaling for bone remodeling. | Li, 2017; Hao et al., 2024. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).