1. Introduction

Vitamin D plays a crucial role in maintaining calcium homeostasis, promoting skeletal health, and supporting various physiological functions. Deficiency in serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D)—defined as levels below 20 ng/mL (50 nmol/L)—is a widespread global health concern. It has been linked to increased risks of osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease, immune dysfunction, and cancer [

1,

2]. Paradoxically, despite year-round sunlight, vitamin D deficiency remains alarmingly prevalent in Qatar and the wider Middle East, underscoring a multifaceted interplay of environmental, behavioral, and genetic factors [

3,

4].

Large genome-wide association studies (GWAS) in predominantly European populations (e.g., UK Biobank) and in regional cohorts like the Qatar Biobank (QBB) have identified several loci associated with serum 25(OH)D concentrations, like

GC (Group-specific component, encodes vitamin D-binding protein),

CYP2R1 (encodes 25-hydroxylase), and

DHCR7 (encodes 7-dehydrocholesterol reductase) [

3,

5,

6]. However, many of these identified variants are common (minor allele frequency, MAF >5%), and collectively explain only a modest portion of the trait’s heritability. This leaves a significant proportion of the genetic contribution to vitamin D status unaccounted for—often referred to as the “missing heritability”[

7]. Rare variants (MAF ≤1%) have largely been overlooked in prior GWAS; however, population genetics theory suggests they may play a pivotal role, particularly due to their potential deleterious effects maintained through purifying selection [

8].

Recent studies have shown that rare, high-impact variants can substantially influence human traits and disease risk, including Mendelian disorders and monogenic forms of common diseases [

9]. For example, exome sequencing has revealed rare non-synonymous and putative loss-of-function variants in

CYP2R1—a key vitamin D 25-hydroxylase—linked to altered vitamin D metabolism and increased susceptibility to rickets [

10]. Similarly, rare variants in genes such as

AGO4 (Argonaute Component 4) and ATP-related pathways have been implicated in vitamin D regulation in Korean and European cohorts [

11,

12]. However, such findings remain underexplored in Middle Eastern populations, which possess distinct demographic histories and genetic structures.

Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) offers a powerful tool to uncover population-specific rare variants that may be absent or underrepresented in global reference panels [

3]. Leveraging the deeply characterized QBB cohort, this study aims to perform a large-scale rare variant association analysis targeting variants with MAF between 0.01 and 0.0001. By integrating quantitative 25(OH)D phenotypes and replicating key findings within the QBB dataset, we aim to identify novel rare variants that contribute to vitamin D levels and risk of deficiency in the Qatari population. Given that genetics explain up to 50% of 25(OH)D variability [

3,

5], this study will clarify the genetic basis of vitamin D regulation and support precision health approaches tailored to Middle Eastern populations and their disease burden, including cancer.

3. Discussion

This study presents the first GWAS in a Middle Eastern population to identify rare variants (MAF 0.01–0.0001) influencing continuous 25(OH)D concentrations and clinical vitamin D deficiency, leveraging high-coverage WGS data from over 13,000 QBB participants. The notably high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in our cohort (>60%), consistent with earlier QBB and regional reports [

3,

4], underscores the public health relevance of identifying genetic determinants contributing to this trait. Despite abundant sunlight, deficiency remains widespread, a paradox attributed to a combination of cultural, lifestyle, metabolic, and genetic predisposition [

1]. Most previous vitamin D GWAS have predominantly examined common variants in European cohorts [

5,

6], which may overlook ancestry-specific or low-frequency signals relevant to Middle Eastern populations. Our rare-variant analysis complements earlier QBB work on common-variant associations, identifying multiple genome-wide significant signals replicated across independent Qatari cohorts, thereby broadening the known genetic architecture of vitamin D and demonstrating the value of WGS in underrepresented groups.

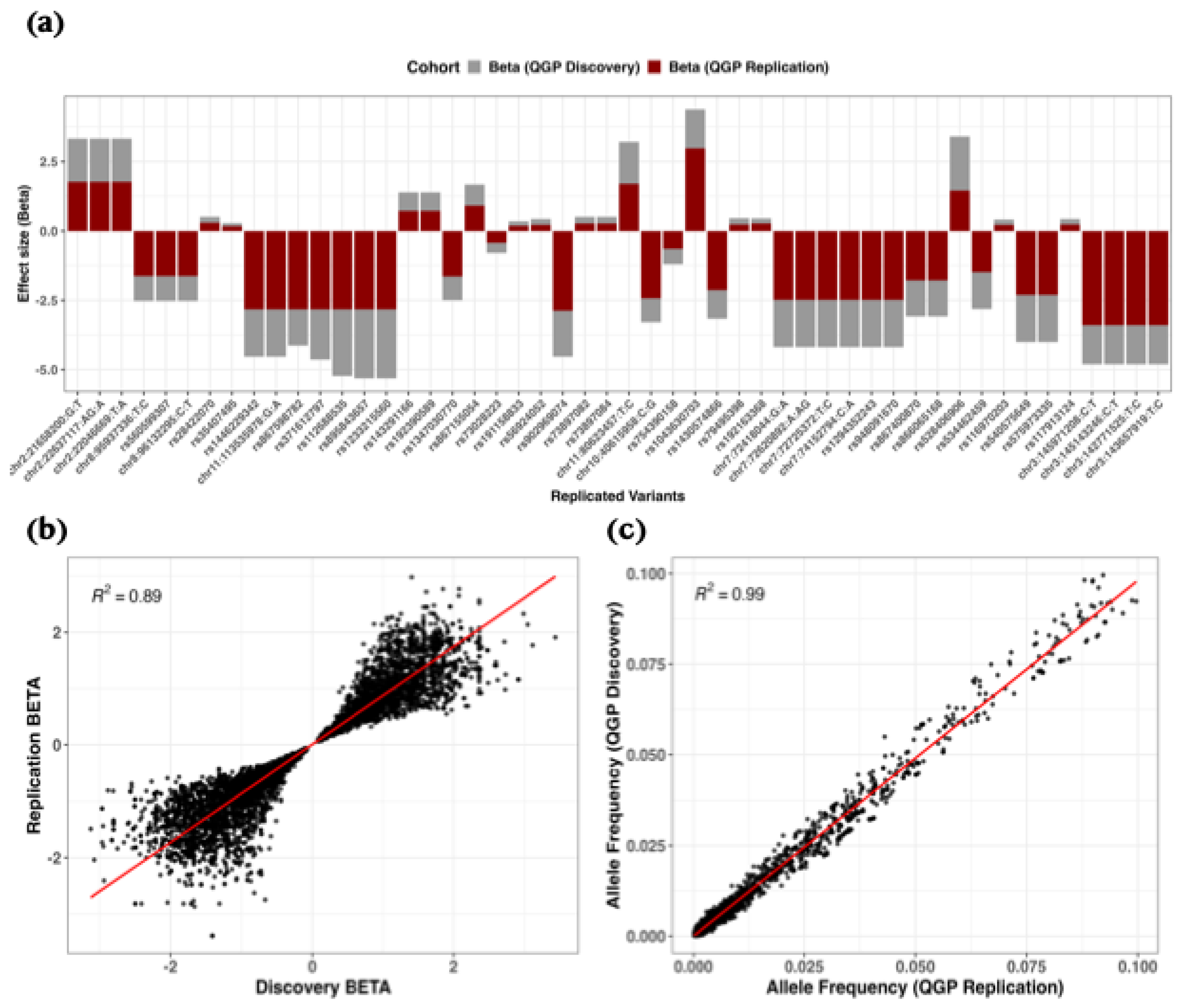

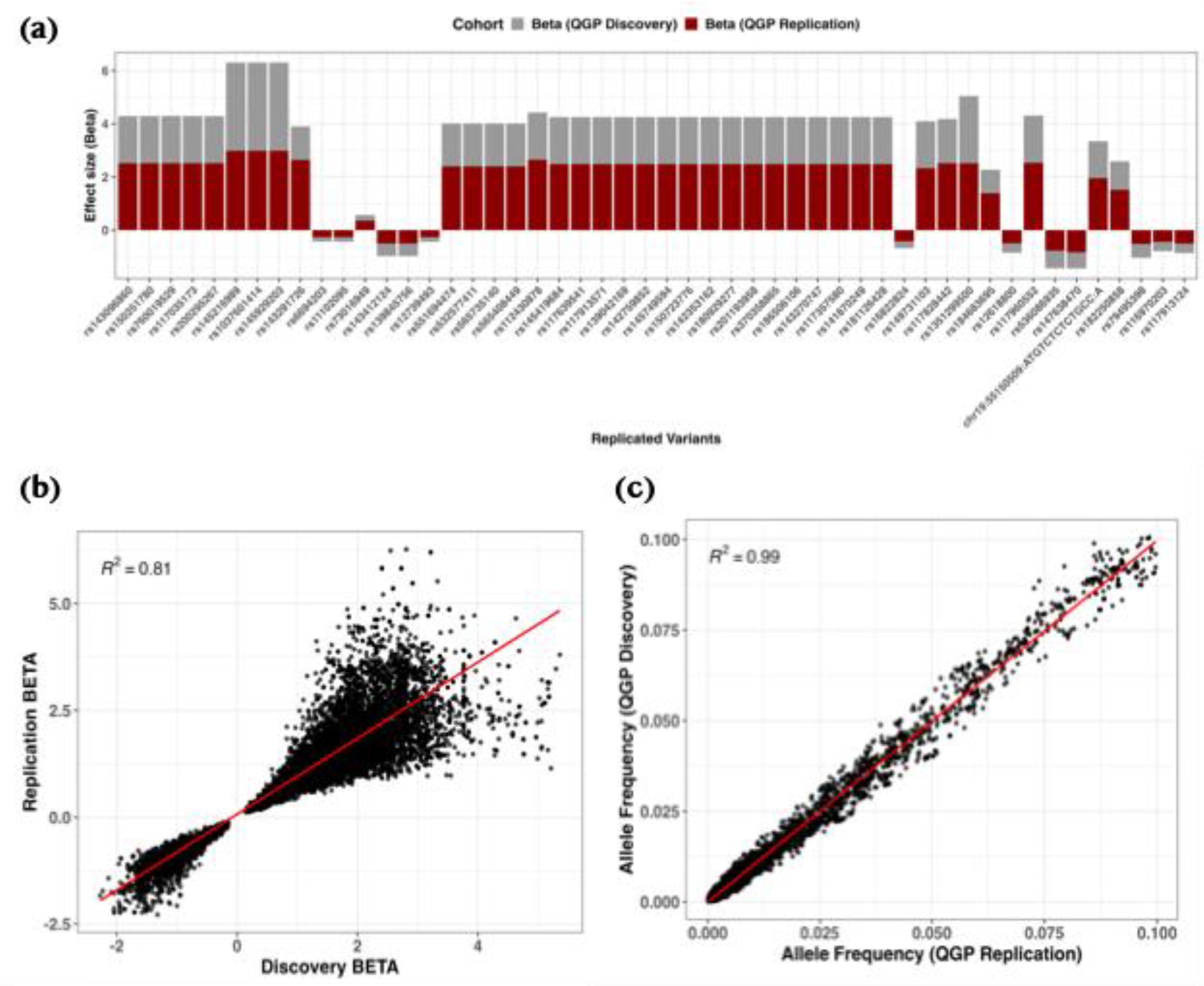

Across quantitative and binary GWAS, we observed strong concordance of allele frequencies and effect sizes between discovery and replication cohorts, with over 60% of overlapping variants showing consistent effect directions. This reproducibility underscores the robustness of association signals across independent QBB subsets, even when individual cohort analyses lacked genome-wide significance. For binary traits, the magnitude of

β estimates reflects the per-allele change in log-odds of deficiency; for rare variants, such effect sizes may correspond to substantial individual-level risk differences despite limited impact at the population level [

7]. Mapping vitamin D deficiency as a binary trait poses inherent challenges, as dichotomizing a continuous biomarker reduces statistical power and environmental influences introduce misclassification [

1,

13]. The modest yield observed in single-cohort analyses in our study is therefore more likely attributable to these methodological and biological constraints than to technical bias.

Our quantitative GWAS identified 41 and 46 genome-wide significant rare variants in the discovery and replication cohorts, respectively, with several mapping to biologically plausible genes involved in lipid metabolism and nutrient transport. For example,

CD36, a class B scavenger receptor implicated in lipid uptake, has also been linked to intestinal absorption and systemic transport of vitamin D [

14], providing a potential mechanistic link to our observed associations. The rare variant rs192198195 in CD36 was associated with a 0.86-fold lower inverse-normalized 25(OH)D concentration per effect allele, potentially reducing systemic vitamin D bioavailability.

Similarly,

SLC16A7 (rs889439631) and

TMEM135 (chr11:87081213:G:T) variants were associated with an estimated ~0.95-fold reduction in vitamin D concentration per effect allele.

SLC16A7 and

TMEM135 encode membrane transporters involved in monocarboxylate and lipid handling, pathways relevant to the intracellular trafficking of lipophilic compounds like vitamin D [

15,

16]. These mechanisms are distinct from the canonical

GC,

CYP2R1,

DHCR7,

MGAM, and

PHF2 loci [

3,

4,

5,

6], suggesting that rare variants may capture regulatory and transport processes under stronger selective constraint. The combined meta-analysis further identified strong signals in

CNTN3 (rs115651661) and

EBF1 (rs536115678), associated with ~2.1-fold higher and ~0.18-fold lower vitamin D levels per allele, respectively. While the role in vitamin D metabolism is unclear,

EBF1 may influence vitamin D via metabolic–endocrine regulation [

17], highlighting the potential impact of rare variants acting through noncanonical pathways.

In the binary deficiency analysis, no genome-wide significant variants were detected in the discovery cohort; however, replication revealed a significant association at

RAP1GAP (rs577185477), with a 67% higher odds of deficiency per risk allele.

RAP1GAP negatively regulates RAP1, a GTPase influencing endothelial integrity and cell adhesion—processes linked to vitamin D biology through vascular and immune pathways [

18]. Given evidence connecting vitamin D deficiency to endothelial dysfunction, and supplementation can improve vascular health [

19], this variant may act via endothelial stability pathways and warrants further investigation.

Meta-analysis across cohorts substantially improved power, uncovering rare-variant associations beyond single-cohort detection— paralleling European vitamin D GWAS where low-frequency variants with larger effects complement established

GC,

CYP2R1, and

DHCR7 loci [

3,

4]. Notably,

RDH13, encoding mitochondrial retinol dehydrogenase, connects retinoid metabolism to the VDR–retinoid X receptor (RXR) transcriptional complex, a core regulator of vitamin D-responsive gene expression [

20]. Additionally, rs952825245 in

SLC25A37 (Mitoferrin-1), a mitochondrial iron importer, was associated with ≥50% higher odds of deficiency per allele. Given iron’s role in immune and endocrine function, and reported interplay with vitamin D metabolism [

21], this association may reflect an indirect yet biologically relevant mechanism.

Although several PGS for vitamin D have been developed from common-variant GWAS in European cohorts [

6], no published PGS currently incorporates rare variants. In our previous work, we evaluated the performance of a European-derived PRS [

22], which demonstrated markedly reduced predictive performance in Qataris (R = 0.098) compared to the R ≈ 0.46 reported in Europeans, and achieved only modest discrimination for vitamin D deficiency [

3]. Similar findings were observed in our Lebanese cohort, where European-derived PRS performance was also diminished [

4]. In both cases, predictive power was far lower than in the original European populations, underscoring the limitations of cross-ancestry portability for common-variant PRS.

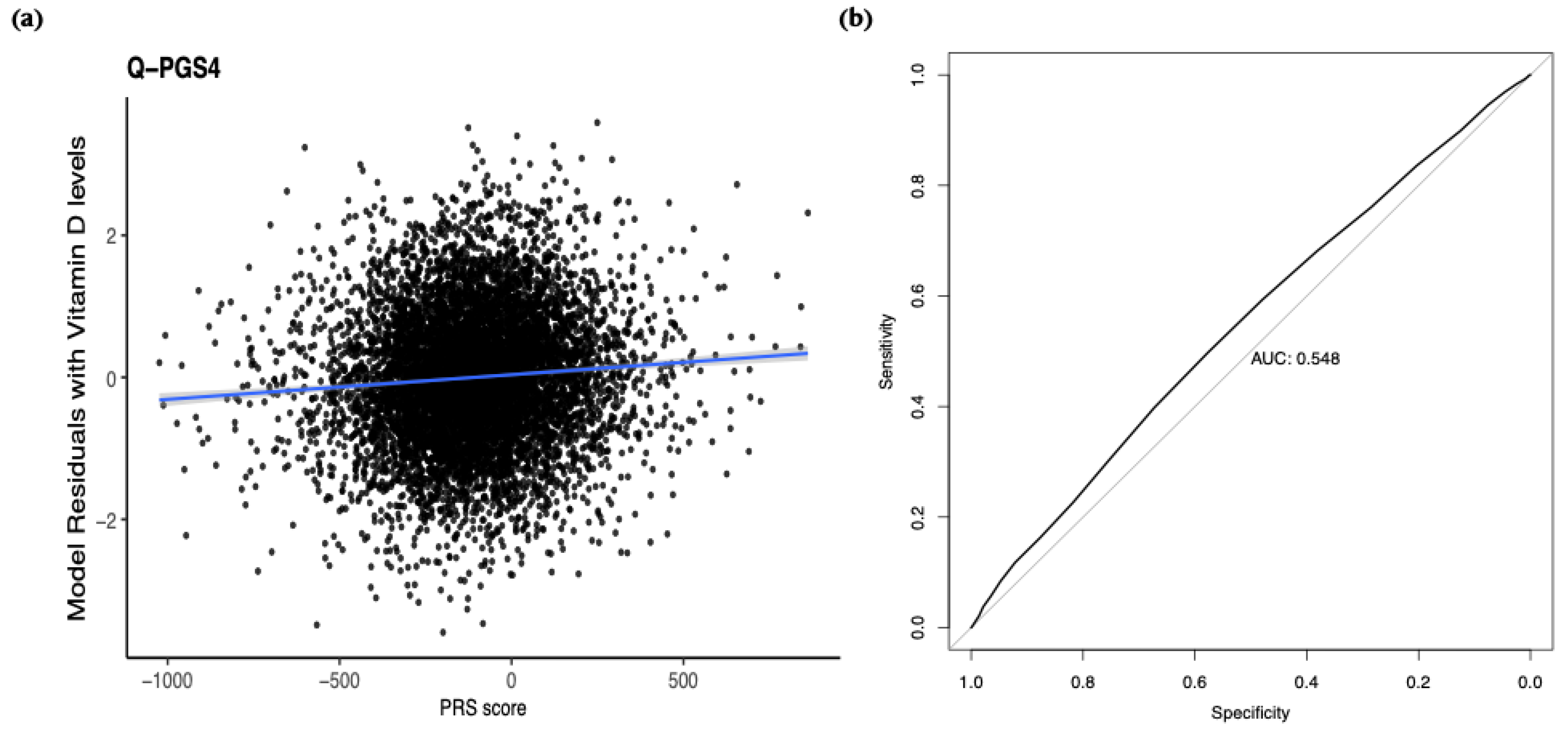

In the present study, we focused exclusively on evaluating the performance of rare-variant-based PGS derived from our Qatari discovery dataset. Using genome-wide significant and suggestive rare variants from the discovery GWAS, we constructed four population-specific PRS panels, retaining over 350,000 variants in the replication dataset. Despite the low frequency of contributing alleles, these PRS explained a ~14.6% of variance in continuous 25(OH)D levels—substantially exceeding the <2% variance explained by a European-derived PRS when applied to regional data [

3,

4]. This improvement is consistent with broader evidence that ancestry-specific models outperform those developed in other populations, largely due to differences in linkage disequilibrium (LD) structure, allele frequency, and variant architecture [

3,

23]. While predictive accuracy for binary deficiency was modest (AUC = 0.548)—consistent with European PRS studies where common variants explain most variance (AUC ≈ 0.59–0.61) [

22]—our findings demonstrate that incorporating ancestry-specific rare alleles captures meaningful genetic risk for vitamin D deficiency. Integrating these rare-variant signals with common-variant predictors may further enhance risk stratification in Middle Eastern populations.

Our findings provide novel insights into the genetic architecture of vitamin D status in a large, underrepresented Middle Eastern population, yet several avenues remain for further investigation. Further efforts should explore ultra-rare variants (MAF <0.0001), expand analyses to diverse ancestries, and incorporate detailed environmental and lifestyle data to refine estimates of genetic effects. Functional validation of key candidates, such as RAP1GAP, RDH13, and SLC25A37, will be essential to clarify causal mechanisms in vitamin D regulation. Broader cross-ancestry replication, gene–environment interaction studies, and improved polygenic models integrating rare and common variants could ultimately enhance risk prediction and guide precision strategies for preventing vitamin D deficiency.

In summary, this rare-variant GWAS in a Middle Eastern population identifies novel genetic determinants of vitamin D status, including RAP1GAP, RDH13, and SLC25A37, implicating diverse metabolic and regulatory pathways. While clinical prediction of deficiency remains challenging, these findings establish a robust genetic foundation for functional validation and for developing precision medicine strategies tailored to populations with a high burden of deficiency.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Population and Ethical Approvals

This study was conducted using data from the QBB linked to the Qatar Genome Program (QGP) WGS. QBB enrolls adult participants aged 18 years and older who are Qatari nationals or long-term residents (≥15 years). All participants undergo standardized clinical assessments, provide detailed lifestyle and medical history information through questionnaires, and contribute biological samples, including blood, urine, and saliva. QBB recruitment, sample handling, and data access procedures are described previously [

3,

24].

The current analysis focused on 13,808 Qatari individuals from the QBB cohort with high-quality whole-genome sequencing from the Qatar Genome Program, of whom 13,652 with available serum 25(OH)D measurements were included in the final analysis. This dataset was randomly split into two non-overlapping subsets for independent analysis: a discovery cohort (QGP6013, n = 5,885) and a replication cohort (QGP7795, n = 7,767), to allow internal validation of genetic findings within the same national cohort. Participants were recruited following ethical approval from the QBB Institutional Review Board (IRB project number, QF-QGP-RES-ACC-00075), and all individuals gave written informed consent before participation.

4.2. Phenotype Measurements and Related Covariates

Serum 25(OH)D levels were quantified in the diagnostic laboratories of Hamad Medical Corporation using a standardized chemiluminescent immunoassay (CLIA) platform (LIAISON, DiaSorin, Germany). Briefly, blood samples were centrifuged for serum separation and stored at −80°C before biochemical analysis. Full methodological details, including assay protocol and instrument calibration, have been previously described.

Two phenotype definitions were used in this study. First, for quantitative genetic analysis, raw serum 25(OH)D concentrations (in ng/mL) were normalized using rank-based inverse-normal transformation implemented in R (v3.4.0). This transformation normalizes the distribution, minimizes skewness, and reduces the influence of outliers in association models. Second, a binary vitamin D deficiency phenotype was defined using serum 25(OH)D concentrations, with individuals classified as deficient if 25(OH)D < 20 ng/mL and as sufficient controls if 25(OH)D > 30 ng/mL. These clinically relevant thresholds are consistent with international guidelines and have been widely adopted in nutritional epidemiology and previous vitamin D GWAS.

Anthropometric measures, including weight and height, were obtained during physical examinations using standardized equipment (Seca 284 stadiometer and balance), and BMI was calculated as weight (kg) divided by the square of height (m2).

4.3. Whole-Genome Sequencing and Quality Control

The procedures for genomic DNA extraction and WGS have been detailed in a prior publication [

25]. Concisely, DNA quantity and integrity were assessed using the Quant-iT dsDNA Assay Kit (Invitrogen, USA) and FlexStation 3 reader (Molecular Devices, USA). High-coverage WGS (30× depth) was performed at Sidra Medicine Genomics Facility, Qatar, on the Illumina HiSeq X Ten (Illumina, USA). Raw reads were quality-checked with FastQC (v0.11.2), aligned to the human reference genome GRCh38 using BWA-MEM (v0.7.12), and variants were called using GATK HaplotypeCaller (v3.4). Joint genotyping was conducted on consolidated gVCFs via GenomicsDB, and variants were filtered via GATK’s Variant Quality Score Recalibration (VQSR), retaining only “PASS” variants for analysis.

Stringent quality control (QC) procedures were applied at both the sample and variant level to ensure high confidence in genetic findings through PLINK (v2.0) [

26]. Samples were excluded if they had genotype call rates <95%, ambiguous or mismatched gender, excess heterozygosity (>±4 standard deviations from the mean), or were identified as duplicates. Population structure was assessed using multidimensional scaling (MDS) and pairwise identity-by-state (IBS) analysis, based on a pruned set of independent autosomal SNPs selected using an LD threshold of r² < 0.05 within a sliding window of 200 SNPs. Individuals deviating more than ±4 standard deviations from the first two MDS components were flagged as population outliers and excluded. Variant-level QC excluded SNPs with MAF outside the rare range of interest (i.e., <0.0001 or >0.01), genotype call rate <90%, those on the X chromosome, or those deviating from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (

P-value < 1×10⁻⁶). The final analysis comprised 49,260,795 high-quality rare variants (MAF 0.0001–0.01) in the discovery dataset and 56,600,172 in the replication dataset, analyzed separately.

4.4. Genome-Wide Association Analyses

Genome-wide association analyses were conducted using a two-stage design to identify rare genetic variants (MAF 0.0001–0.01) associated with serum 25(OH)D levels. The discovery stage included 5,884 participants from the QGP6013 cohort, while the replication stage involved 7,767 independent participants from the QGP7795 cohort. Association testing was performed separately in each cohort using the SAIGE/R package (Scalable and Accurate Implementation of GEneralized mixed model), a computationally efficient mixed-model regression framework that accounts for sample relatedness and case–control imbalance [

27].

For the quantitative trait (rank-based inverse-normalized 25(OH)D), linear mixed models were applied; for the binary trait of vitamin D deficiency, logistic mixed models were used. All models included covariates for age, sex, and the first four genetic PCs to correct for population stratification. As all samples were collected during a comparable sunny season in Qatar, seasonality was not considered a confounding factor in the analysis. Genome-wide significance was defined as P < 5×10⁻⁸, suggestive significance as P < 1×10⁻⁵, and nominal significance as P <0.05.

To evaluate replication and assess the correlation of effect sizes and allele frequencies between cohorts, we first identified loci associated with 25(OH)D that were driven by the same lead variants in both the discovery and replication datasets. We then examined variants within a ±250 kb region flanking each genome-wide significant signal from the discovery cohort to identify additional replicated associations. Variants passing genome-wide significance (P < 5 × 10⁻⁸) in discovery were considered replicated if they showed nominal significance (P < 0.05) and had a consistent direction of effect (based on beta coefficients) in the replication cohort. To assess cross-cohort concordance, we performed linear regression analyses comparing allele frequencies and effect sizes between cohorts, reporting the regression slope, 95% CI, and R².

Subsequently, a fixed-effects inverse-variance-weighted meta-analysis was implemented in PLINK (v2.0) to combine results across both datasets [

26]. Heterogeneity across cohorts was assessed using Cochran’s Q test [

28]. The impact of associated variants was evaluated based on the magnitude and direction of their beta coefficients. Q–Q plots, Manhattan plots, and

λGC were generated using R (v4.4.1). Our discovery dataset demonstrated sufficient statistical power (≥95%) to detect variants with an effect size of

β = –3.03 at the genome-wide significance threshold (

P < 5 × 10⁻⁸).

4.5. Polygenic Score Construction and Evaluation

PGS were constructed to estimate individual genetic predisposition to serum 25(OH)D levels based on the cumulative effect of associated rare variants. We derived the PGS using summary statistics from the discovery GWAS dataset, applying the clumping-and-thresholding (C+T) approach as implemented in PLINK (v1.9) [

29]. This method identifies sets of independent variants by grouping SNPs in LD around index SNPs based on a predefined LD threshold (r² = 0.2) and applying varying

P-value cutoffs to include only statistically relevant variants.

PGS were generated across a range of P-value thresholds (from 5 × 10⁻⁸ to 5 × 10⁻¹), resulting in multiple rare-variant-based PGS panels, sequentially labeled from Q-PGS1 to QGP-4 according to decreasing statistical stringency. Each PGS was tested for predictive performance in the replication cohort (QGP7795, n = 7,767) using linear regression models for the continuous trait and logistic regression for vitamin D deficiency. Models were adjusted for age, sex, and the first four PCs to account for population structure. The optimal PGS panel was identified based on the highest adjusted R² for the quantitative phenotype and AUC for the binary phenotype.

4.6. Variant Annotation and Functional Characterization

Genome-wide significant variants identified in GWAS and meta-analyses were annotated using the Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor (VEP; GRCh38, release 114) [

30]. Functional consequences (e.g., missense, intronic, intergenic), gene proximity, and regulatory annotations were also extracted.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, NNH, OA, and GN; Methodology, NNH and U-KU; Software, NNH and U-KU; Validation, NNH, OA, and GN; Formal Analysis, NNH and U-KU; Investigation, NNH, OA, and GN; Resources, OA and GN; Data Curation, NNH, U-KU; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, NNH; Writing – Review & Editing, NNH, U-KU, OA, and GN; Visualization, NNH and U-KU; Supervision, OA and GN; Project Administration, OA and GN; Funding Acquisition, OA and GN.

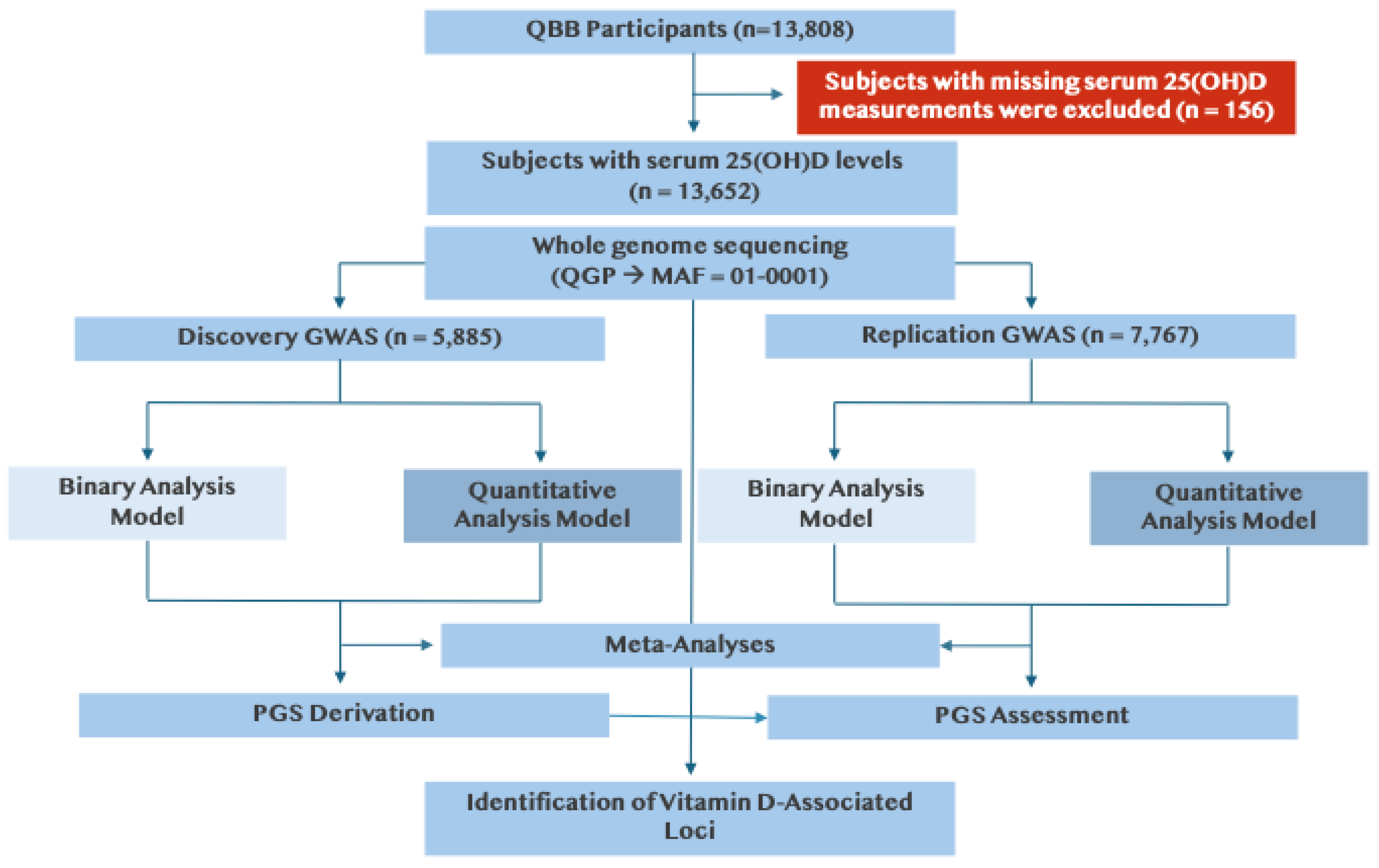

Figure 1.

Study design for rare-variant genome-wide association analysis of vitamin D. Data were obtained from 13,808 Qatar Biobank (QBB) participants, of whom 13,652 had available serum vitamin D measurements. Vitamin D deficiency was defined as serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) levels < 20 ng/mL. Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) was performed through the Qatar Genome Program (QGP). Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) were conducted separately in a discovery cohort (n = 5,885 of 6,013) and a replication cohort (n = 7,767 of 7,795) using SAIGE (Scalable and Accurate Implementation of GEneralized mixed model), under both quantitative (inverse-normal–transformed 25(OH)D) and binary (deficient vs. sufficient) models. Results were combined in fixed-effects meta-analysis using PLINK. Polygenic scores (PGS) were derived from discovery GWAS results and evaluated in the replication cohort.

Figure 1.

Study design for rare-variant genome-wide association analysis of vitamin D. Data were obtained from 13,808 Qatar Biobank (QBB) participants, of whom 13,652 had available serum vitamin D measurements. Vitamin D deficiency was defined as serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) levels < 20 ng/mL. Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) was performed through the Qatar Genome Program (QGP). Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) were conducted separately in a discovery cohort (n = 5,885 of 6,013) and a replication cohort (n = 7,767 of 7,795) using SAIGE (Scalable and Accurate Implementation of GEneralized mixed model), under both quantitative (inverse-normal–transformed 25(OH)D) and binary (deficient vs. sufficient) models. Results were combined in fixed-effects meta-analysis using PLINK. Polygenic scores (PGS) were derived from discovery GWAS results and evaluated in the replication cohort.

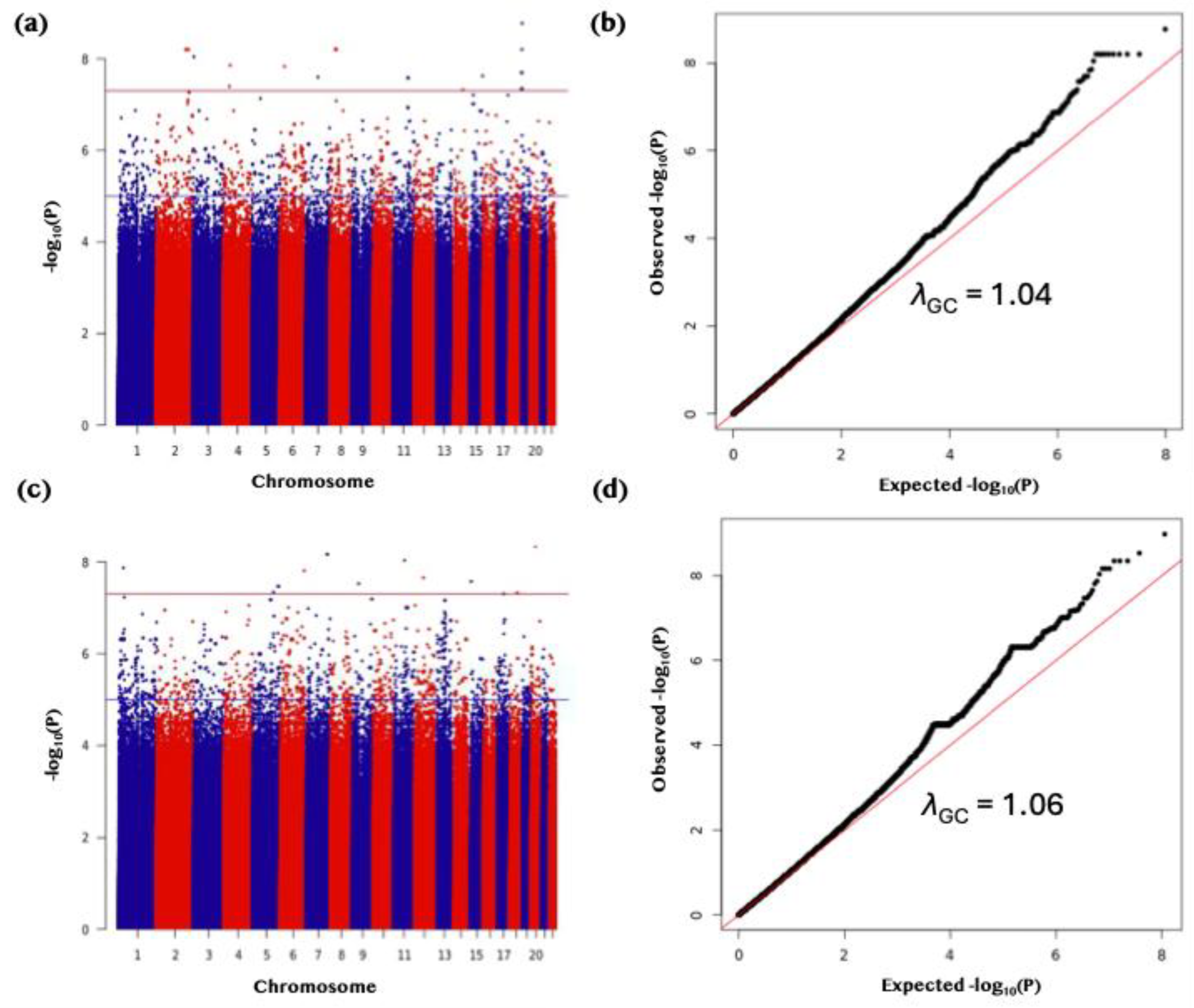

Figure 2.

Genome-wide association analysis of serum 25(OH)D concentrations in discovery and replication cohorts. (a) Manhattan plot of GWAS results for the discovery cohort (QGP6013; autosomes only) using variants with minor allele frequency (MAF) between 0.0001 and 0.1. Serum 25(OH)D concentrations were inverse-normal transformed for analysis. The red horizontal line denotes the genome-wide significance threshold (P < 5 × 10⁻⁸). (b) Quantile–quantile (Q–Q) plot for the discovery cohort GWAS showing minimal genomic inflation (λGC = 1.04). (c) Manhattan plot of GWAS results for the replication cohort (QGP7795; autosomes only) applying the same filtering and transformation as in the discovery cohort. The red horizontal line denotes the genome-wide significance threshold (P < 5 × 10⁻⁸). (d) Q–Q plot for the replication cohort GWAS showing minimal genomic inflation (λGC = 1.06).

Figure 2.

Genome-wide association analysis of serum 25(OH)D concentrations in discovery and replication cohorts. (a) Manhattan plot of GWAS results for the discovery cohort (QGP6013; autosomes only) using variants with minor allele frequency (MAF) between 0.0001 and 0.1. Serum 25(OH)D concentrations were inverse-normal transformed for analysis. The red horizontal line denotes the genome-wide significance threshold (P < 5 × 10⁻⁸). (b) Quantile–quantile (Q–Q) plot for the discovery cohort GWAS showing minimal genomic inflation (λGC = 1.04). (c) Manhattan plot of GWAS results for the replication cohort (QGP7795; autosomes only) applying the same filtering and transformation as in the discovery cohort. The red horizontal line denotes the genome-wide significance threshold (P < 5 × 10⁻⁸). (d) Q–Q plot for the replication cohort GWAS showing minimal genomic inflation (λGC = 1.06).

Figure 3.

Replication of rare variant associations for serum 25(OH)D levels in the QGP cohorts. (a) Bar plots comparing effect estimates (β) between discovery (grey) and replication (dark red) cohorts, highlighting variants meeting a suggestive significance threshold (P < 3.0 × 10⁻⁵) with consistent effect direction. (b) Scatter plot of β estimates between cohorts, with the regression line shown in red and R² indicating the coefficient of determination. (c) Scatter plot of allele frequencies between cohorts with corresponding regression statistics. Displayed variants met the nominal significance threshold (P < 0.05) and had a consistent direction of effect.

Figure 3.

Replication of rare variant associations for serum 25(OH)D levels in the QGP cohorts. (a) Bar plots comparing effect estimates (β) between discovery (grey) and replication (dark red) cohorts, highlighting variants meeting a suggestive significance threshold (P < 3.0 × 10⁻⁵) with consistent effect direction. (b) Scatter plot of β estimates between cohorts, with the regression line shown in red and R² indicating the coefficient of determination. (c) Scatter plot of allele frequencies between cohorts with corresponding regression statistics. Displayed variants met the nominal significance threshold (P < 0.05) and had a consistent direction of effect.

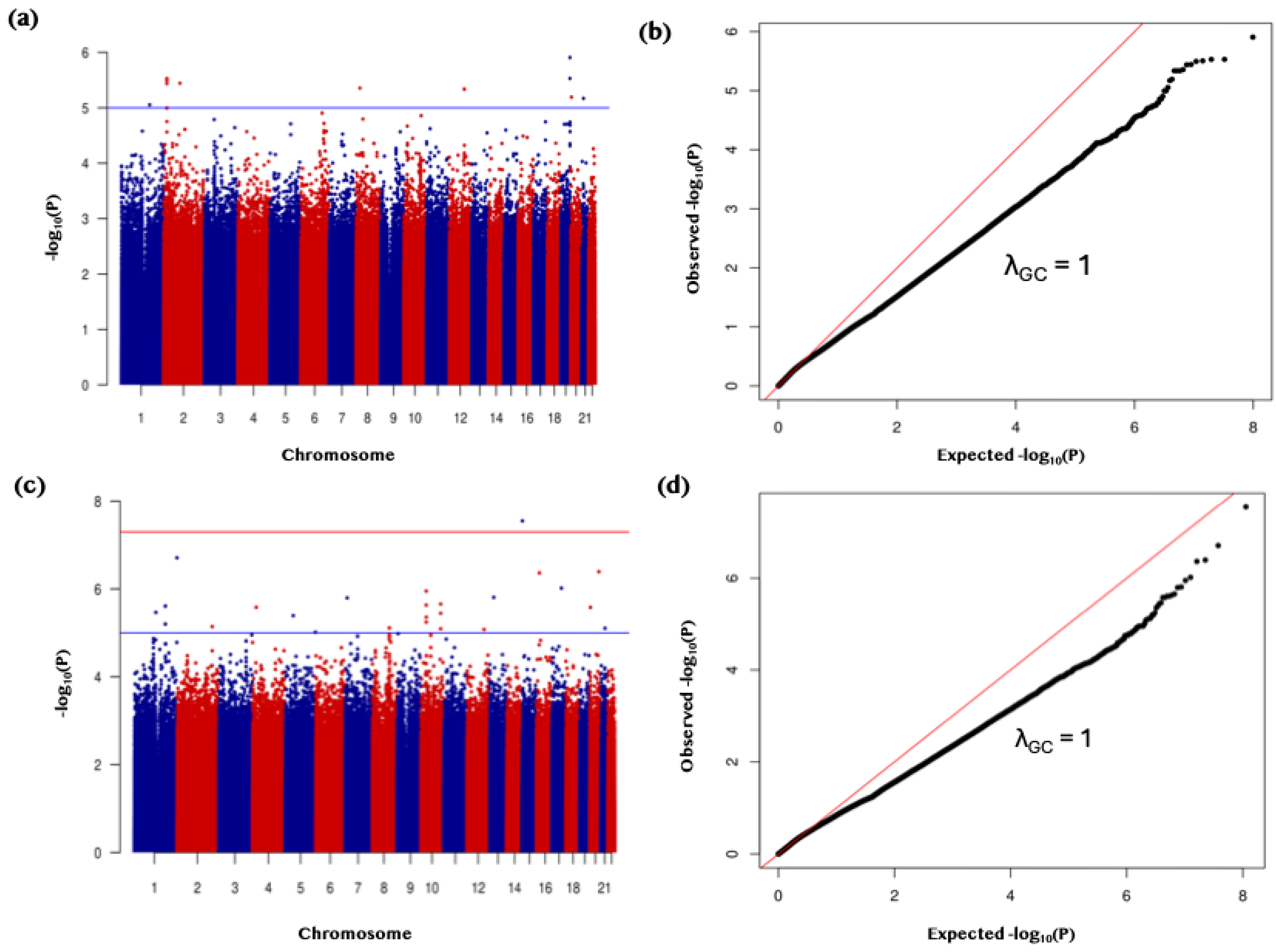

Figure 4.

Binary genome-wide association study (GWAS) of vitamin D deficiency in discovery and replication cohorts. (a) Manhattan plot of GWAS results for the discovery cohort (QGP6013; autosomes only) filtered for variants with MAF 0.0001–0.1, assessing the binary vitamin D deficiency trait. The blue horizontal line denotes the genome-wide suggestive significance threshold (P < 5 × 10⁻⁵). (b) Quantile–quantile (Q–Q) plot for the discovery GWAS, indicating minimal genomic inflation (λGC = 1.00). (c) Manhattan plot of GWAS results for the replication cohort (QGP7795; autosomes only) filtered for variants with MAF 0.0001–0.1, assessing the binary vitamin D deficiency trait. The red horizontal line denotes the genome-wide significance threshold (P < 5 × 10⁻⁸). (d) Q–Q plot for the replication GWAS, indicating minimal genomic inflation (λGC = 1.00).

Figure 4.

Binary genome-wide association study (GWAS) of vitamin D deficiency in discovery and replication cohorts. (a) Manhattan plot of GWAS results for the discovery cohort (QGP6013; autosomes only) filtered for variants with MAF 0.0001–0.1, assessing the binary vitamin D deficiency trait. The blue horizontal line denotes the genome-wide suggestive significance threshold (P < 5 × 10⁻⁵). (b) Quantile–quantile (Q–Q) plot for the discovery GWAS, indicating minimal genomic inflation (λGC = 1.00). (c) Manhattan plot of GWAS results for the replication cohort (QGP7795; autosomes only) filtered for variants with MAF 0.0001–0.1, assessing the binary vitamin D deficiency trait. The red horizontal line denotes the genome-wide significance threshold (P < 5 × 10⁻⁸). (d) Q–Q plot for the replication GWAS, indicating minimal genomic inflation (λGC = 1.00).

Figure 5.

Replication analysis of rare variant associations for a binary trait in the QGP cohorts. (a) Bar plots comparing effect estimates (odds ratios, OR) between discovery (grey) and replication cohorts (dark red), highlighting variants meeting a suggestive significance threshold (P < 3.0 × 10⁻⁵) with consistent effect direction. (b) Scatter plot of OR between cohorts, with the red line indicating the best-fit linear regression. (c) Scatter plot of allele frequencies between cohorts, with the red line representing the regression fit. R² denotes the coefficient of determination from correlation analysis, and 95% confidence intervals (CI) are shown for regression slopes. All displayed variants met the nominal significance threshold (P < 0.05) and had a consistent direction of effect.

Figure 5.

Replication analysis of rare variant associations for a binary trait in the QGP cohorts. (a) Bar plots comparing effect estimates (odds ratios, OR) between discovery (grey) and replication cohorts (dark red), highlighting variants meeting a suggestive significance threshold (P < 3.0 × 10⁻⁵) with consistent effect direction. (b) Scatter plot of OR between cohorts, with the red line indicating the best-fit linear regression. (c) Scatter plot of allele frequencies between cohorts, with the red line representing the regression fit. R² denotes the coefficient of determination from correlation analysis, and 95% confidence intervals (CI) are shown for regression slopes. All displayed variants met the nominal significance threshold (P < 0.05) and had a consistent direction of effect.

Figure 6.

Predictive performance of discovery-derived polygenic risk scores (PRS) in the replication cohort.

(a) Linear regression of inverse-normalized 25(OH)D levels on a representative PRS (

P < 5×10⁻

8), adjusted for age, sex, and the first four genetic principal components.

(b) Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for the same PRS predicting vitamin D deficiency (25(OH)D < 20 ng/mL; AUC = 0.548,

P = 9.22 × 10⁻⁶; odds ratio = 0.9995; 95% CI: 0.9993–0.9997). Results for additional PRS thresholds (

P < 5×10⁻⁶,

P < 5×10⁻⁷,

P < 5×10⁻⁸) are shown in the

Supplementary Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 6.

Predictive performance of discovery-derived polygenic risk scores (PRS) in the replication cohort.

(a) Linear regression of inverse-normalized 25(OH)D levels on a representative PRS (

P < 5×10⁻

8), adjusted for age, sex, and the first four genetic principal components.

(b) Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for the same PRS predicting vitamin D deficiency (25(OH)D < 20 ng/mL; AUC = 0.548,

P = 9.22 × 10⁻⁶; odds ratio = 0.9995; 95% CI: 0.9993–0.9997). Results for additional PRS thresholds (

P < 5×10⁻⁶,

P < 5×10⁻⁷,

P < 5×10⁻⁸) are shown in the

Supplementary Figures 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants.

| Cohort |

Discovery |

Replication |

All Subjects |

| Sample size |

5,885 |

7,767 |

13,652 |

| Male n (%) |

2,567 (43.6) |

3,508 (45.2) |

6,075 (44.5) |

| Female n (%) |

3,318 (56.4) |

4,259 (54.8) |

7,577 (55.5) |

| Mean age ± SD |

39.75 ± 12.83 |

40.38 ± 13.37 |

40.11 ± 13.14 |

| BMI (kg/m≤) |

29.38 ± 6.05 |

29.69 ± 6.14 |

29.55 ± 6.10 |

| Vit D (ng/mL) ± SD |

19.36 ± 11.12 |

19.52 ± 11.14 |

19.45 ± 11.13 |

| Normal Vit D n (%) |

675 (11.5) |

1,073 (13.8) |

1,748 (12.8) |

| Insufficient Vit D n (%) |

1,612 (27.4) |

2,053 (26.4) |

3,665 (26.8) |

| Deficient Vit D n (%) |

3,598 (61.1) |

4,641 (59.8) |

8,239 (60.4) |

| Descriptive statistics of the Qatar Biobank (QBB) cohort used in the discovery (batch 1) and replication (batch 2) analyses. Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and categorical variables are presented as number (percentage). Vitamin D status was categorized based on serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) levels as follows: normal (>30 ng/mL), insufficient (20–30 ng/mL), and deficient (<20 ng/mL). BMI = body mass index (kg/m²). The Discovery and Replication cohorts correspond to samples collected in separate batches for the genomic analysis. |

Table 2.

Rare variants significantly associated with vitamin D levels discovered from a meta-analysis of the Replication and Discovery QGP Quantitative GWAS studies.

Table 2.

Rare variants significantly associated with vitamin D levels discovered from a meta-analysis of the Replication and Discovery QGP Quantitative GWAS studies.

| SNP |

CHR |

Position (BP) |

Mapped Gene |

HGVS ID |

Consequence |

A1 |

A2 |

GWAS in Replication QGP (n = 7,767) |

GWAS in Discovery QGP (n = 5,885) |

Meta-analysis |

| MAF (A1) |

Beta (SE) |

P-value |

MAF (A1) |

Beta (SE) |

P-value |

P-value |

BETA |

P-hat |

| rs115651661 |

3 |

74272255 |

CNTN3 |

NC_000003.12:g.74272255T>C |

Intron |

C |

T |

0.0040 |

0.48 (0.12) |

0.00007 |

0.0027 |

0.73 (0.17) |

2.46E-05 |

1.48E-08 |

0.56 |

0.22 |

| rs536115678 |

5 |

158884335 |

EBF1 |

NC_000005.10:g.158884335C>A |

Intron |

A |

C |

0.0003 |

-1.84 (0.48) |

0.00013 |

0.0003 |

-1.67 (0.40) |

3.03E-05 |

1.57E-08 |

-1.74 |

0.79 |

| chr21:43954055:C:T |

21 |

43954055 |

AGPAT3 |

- |

Intron |

T |

C |

0.0004 |

1.26 (0.39) |

0.00138 |

0.0007 |

1.57 (0.34) |

6.10E-06 |

3.65E-08 |

1.43 |

0.55 |

| chr21:43790823:A:G |

21 |

43790823 |

RRP1 |

- |

Upstream gene |

G |

A |

0.0004 |

1.26 (0.39) |

0.00138 |

0.0007 |

1.57 (0.34) |

6.10E-06 |

3.65E-08 |

1.43 |

0.55 |

| rs550626115 |

15 |

63022380 |

TPM1-AS |

NC_000015.10:g.63022380C>T |

Intron |

T |

C |

0.0001 |

-2.41 (0.68) |

0.00039 |

0.0002 |

-2.9 (0.69) |

2.40E-05 |

4.07E-08 |

-2.67 |

0.59 |

| rs1014490316 |

20 |

59592010 |

PHACTR3 |

NC_000020.11:g.59592010A>G |

Intron |

G |

A |

0.0001 |

2.33 (0.68) |

0.00063 |

0.0002 |

2.98 (0.69) |

1.73E-05 |

5.04E-08 |

2.65 |

0.50 |

| Presented data are the same variants in Qatar Biobank (Vitamin D rare GWAS) with the P-het (P-value for Cochran’s Q heterogeneity statistic) > 0.05 and P-value < 7E-08 of the meta-analysis. Abbreviations: A1, effect allele; A2, reference allele; AC_Allele2, allele count for reference allele (A2); AF_A2, allele frequency of reference allele (A2); AF_A1, allele frequency of effect allele (A1); BETA, effect size of A1 allele on 25(OH)D levels; SE, standard error of BETA; Mapped Genes from ANNOVAR; HGVS ID from Ensmebl; GWAS, genome-wide association study; QGP, Qatar Genome Project. |

Table 3.

Rare variants significantly associated with binary vitamin D deficiency discovered from a meta-analysis of the Replication and Discovery QGP GWAS studies.

Table 3.

Rare variants significantly associated with binary vitamin D deficiency discovered from a meta-analysis of the Replication and Discovery QGP GWAS studies.

| SNP |

Gene Mapped |

CHR |

Position (BP) |

HGVS ID |

Consequence |

A1 |

A2 |

Binary GWAS for Vitamin D in Replication QGP (n=7795) |

Binary GWAS for Vitamin D in Discovery QGP (n=6013) |

Meta-analysis (n=2) |

| MAF (A1) |

Beta (SE) |

P-value |

MAF (A1) |

Beta (SE) |

P-value |

P-value |

OR |

P-het |

| rs140456089 |

PPP1R12C |

19 |

55096117 |

NC_000019.10:g.55096117G>A |

synonymous |

A |

G |

0.0042 |

1.55 (0.30) |

2.55E-07 |

0.0042 |

1.55 (0.30) |

2.55E-07 |

3.12E-13 |

4.70 |

1 |

| rs1268647997 |

RDH13 |

19 |

55065320 |

NC_000019.10:g.55065320G>A |

upstream gene |

A |

G |

0.0036 |

1.62 (0.33) |

6.76E-07 |

0.0830 |

0.36 (0.07) |

6.77E-07 |

2.13E-12 |

5.07 |

1 |

| rs62122090 |

HS1BP3 |

2 |

20628549 |

NC_000002.12:g.20628549C>T |

intron |

T |

C |

0.0830 |

0.36 (0.07) |

6.77E-07 |

0.0036 |

1.62 (0.33) |

6.76E-07 |

2.13E-12 |

1.44 |

1 |

| rs73916930 |

HS1BP3 |

2 |

20628921 |

NC_000002.12:g.20628921G>T |

intron |

T |

G |

0.0830 |

0.36 (0.07) |

7.21E-07 |

0.0830 |

0.36 (0.07) |

7.21E-07 |

2.41E-12 |

1.44 |

1 |

| rs4426492 |

HS1BP3 |

2 |

20633127 |

NC_000002.12:g.20633127G>A |

intron |

A |

G |

0.0823 |

0.36 (0.07) |

7.38E-07 |

0.0823 |

0.36 (0.07) |

7.38E-07 |

2.53E-12 |

1.44 |

1 |

| rs1185902565 |

ANKRD36B |

2 |

97591789 |

NC_000002.12:g.97591790del |

upstream gene |

T |

TC |

0.0022 |

2.09 (0.43) |

8.48E-07 |

0.0022 |

2.09 (0.43) |

8.48E-07 |

3.31E-12 |

8.11 |

1 |

| rs73916931 |

HS1BP3 |

2 |

20628926 |

NC_000002.12:g.20628926G>A |

intron |

A |

G |

0.0826 |

0.36 (0.07) |

8.58E-07 |

0.0826 |

0.36 (0.07) |

8.58E-07 |

3.39E-12 |

1.43 |

1 |

| rs952825245 |

SLC25A37 |

8 |

23537529 |

NC_000008.11:g.23537529C>T |

intron |

T |

C |

0.0018 |

2.30 (0.47) |

1.06E-06 |

0.0018 |

2.30 (0.47) |

1.06E-06 |

5.15E-12 |

9.95 |

1 |

| rs143947667 |

ATP2B1-AS1 |

12 |

89934704 |

NC_000012.12:g.89934704A>G |

intron, NCT |

G |

A |

0.0060 |

1.24 (0.25) |

1.11E-06 |

0.0060 |

1.24 (0.25) |

1.11E-06 |

5.68E-12 |

3.45 |

1 |

| rs150425221 |

ATP2B1-AS1 |

12 |

89951086 |

NC_000012.12:g.89951086T>C |

intron, NCT |

C |

T |

0.0060 |

1.24 (0.25) |

1.11E-06 |

0.0060 |

1.24 (0.25) |

1.11E-06 |

5.68E-12 |

3.45 |

1 |

| rs150021601 |

ATP2B1-AS1 |

12 |

90017542 |

NC_000012.12:g.90017542A>C |

intron, NCT |

C |

A |

0.0060 |

1.24 (0.25) |

1.11E-06 |

0.0060 |

1.24 (0.25) |

1.11E-06 |

5.68E-12 |

3.45 |

1 |

| rs143313202 |

- |

20 |

5666007 |

NC_000020.11:g.5666007A>G |

intergenic |

G |

A |

0.0144 |

0.81 (0.17) |

1.62E-06 |

0.0144 |

0.81 (0.17) |

1.62E-06 |

1.18E-11 |

2.25 |

1 |

| rs73195003 |

BTG3 |

21 |

17610076 |

NC_000021.9:g.17610076A>G |

intron |

G |

A |

0.0339 |

-0.52 (0.11) |

1.71E-06 |

0.0339 |

-0.52 (0.11) |

1.71E-06 |

1.32E-11 |

0.59 |

1 |

| rs140599862 |

- |

1 |

167559027 |

NC_000001.11:g.167559027T>C |

intron, NCT |

C |

T |

0.0032 |

1.71 (0.36) |

2.32E-06 |

0.0032 |

1.71 (0.36) |

2.32E-06 |

2.39E-11 |

5.53 |

1 |

| rs80111761 |

HS1BP3 |

2 |

20615440 |

NC_000002.12:g.20615440A>C |

downstream gene |

C |

A |

0.0374 |

0.50 (0.11) |

2.69E-06 |

0.0374 |

0.50 (0.11) |

2.69E-06 |

3.21E-11 |

1.65 |

1 |

| rs62125675 |

HS1BP3 |

2 |

20616068 |

NC_000002.12:g.20616068C>T |

downstream gene |

T |

C |

0.0374 |

0.50 (0.11) |

2.69E-06 |

0.0374 |

0.50 (0.11) |

2.69E-06 |

3.21E-11 |

1.65 |

1 |

| rs73776179 |

LAMA2 |

6 |

129485004 |

NC_000006.12:g.129485004A>G |

intron |

G |

A |

0.0049 |

1.39 (0.30) |

3.42E-06 |

0.0049 |

1.39 (0.30) |

3.42E-06 |

5.11E-11 |

4.01 |

1 |

| rs1454700296 |

NT5C2 |

10 |

103270756 |

NC_000010.11:g.103270756A>G |

intron |

G |

A |

0.0017 |

2.15 (0.46) |

3.85E-06 |

0.0017 |

2.15 (0.46) |

3.85E-06 |

6.45E-11 |

8.56 |

1 |

| rs1315965692 |

NT5C2 |

10 |

103270757 |

NC_000010.11:g.103270757G>A |

intron |

A |

G |

0.0017 |

2.15 (0.46) |

3.85E-06 |

0.0017 |

2.15 (0.46) |

3.85E-06 |

6.45E-11 |

8.56 |

1 |

| rs867934853 |

- |

8 |

41159441 |

NC_000008.11:g.41159441G>T |

downstream gene |

T |

G |

0.0011 |

2.42 (0.53) |

0.0000045 |

0.0011 |

2.42 (0.53) |

4.50E-06 |

8.79E-11 |

11.26 |

1 |

| rs563431181 |

PXK |

3 |

58386670 |

NC_000003.12:g.58386670A>G |

intron |

G |

A |

0.0021 |

1.89 (0.41) |

4.61E-06 |

0.0021 |

1.89 (0.41) |

4.61E-06 |

9.21E-11 |

6.64 |

1 |

| rs6708069 |

HS1BP3 |

2 |

20616814 |

NC_000002.12:g.20616814C>A |

downstream gene |

A |

C |

0.0360 |

0.50 (0.11) |

5.07E-06 |

0.0360 |

0.50 (0.11) |

5.07E-06 |

1.11E-10 |

1.64 |

1 |

| Please refer to Table 1 for parameter detalis. Abbreviations: NCT, non-coding transcript. |

Table 4.

Performance of Candidate polygenic scores (PGS) for vitamin D levels in the replication cohort.

Table 4.

Performance of Candidate polygenic scores (PGS) for vitamin D levels in the replication cohort.

| PGS Score |

PGS Name |

Available variants/Variants in score (%) |

Correlation |

| Adjusted R2

|

(95% CI) |

BETA (SE) |

P-value |

Rho |

|

P<5x10-5_r2<0.2 |

Q-PGS1 |

355,852/112,176,302 (0.32%) |

0.146 |

(0.133 - 0.162) |

0.0004 (0.0076) |

9.08E-12 |

0.0721 |

|

P<5x10-6_r2<0.2 |

Q-PGS2 |

355,852/112,176,302 (0.32%) |

0.146 |

(0.133 - 0.162) |

0.0004 (0.0076) |

9.08E-12 |

0.0721 |

|

P<5x10-7_r2<0.3 |

Q-PGS3 |

355,852/112,176,302 (0.32%) |

0.146 |

(0.133 - 0.162) |

0.0004 (0.0076) |

9.08E-12 |

0.0721 |

|

P<5x10-8_r2<0.2 |

Q-PGS4 |

355,852/112,176,302 (0.32%) |

0.146 |

(0.133 - 0.162) |

0.0004 (0.0076) |

9.08E-12 |

0.0721 |

| PGS, Polygenic Score; CI, Confidence interval; SE, Standard Error; Rho, Spearman correlation coefficient. |