Submitted:

20 December 2025

Posted:

22 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

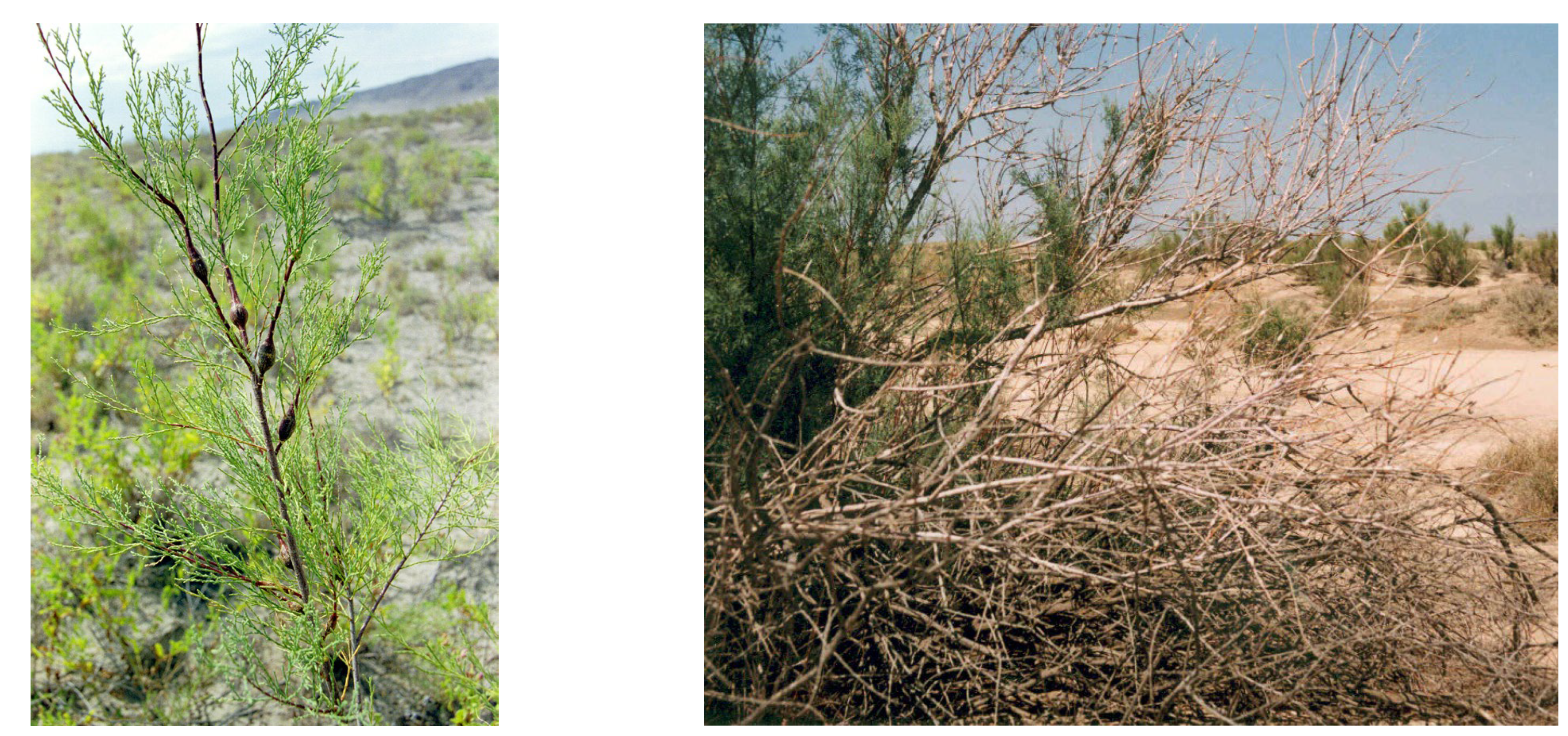

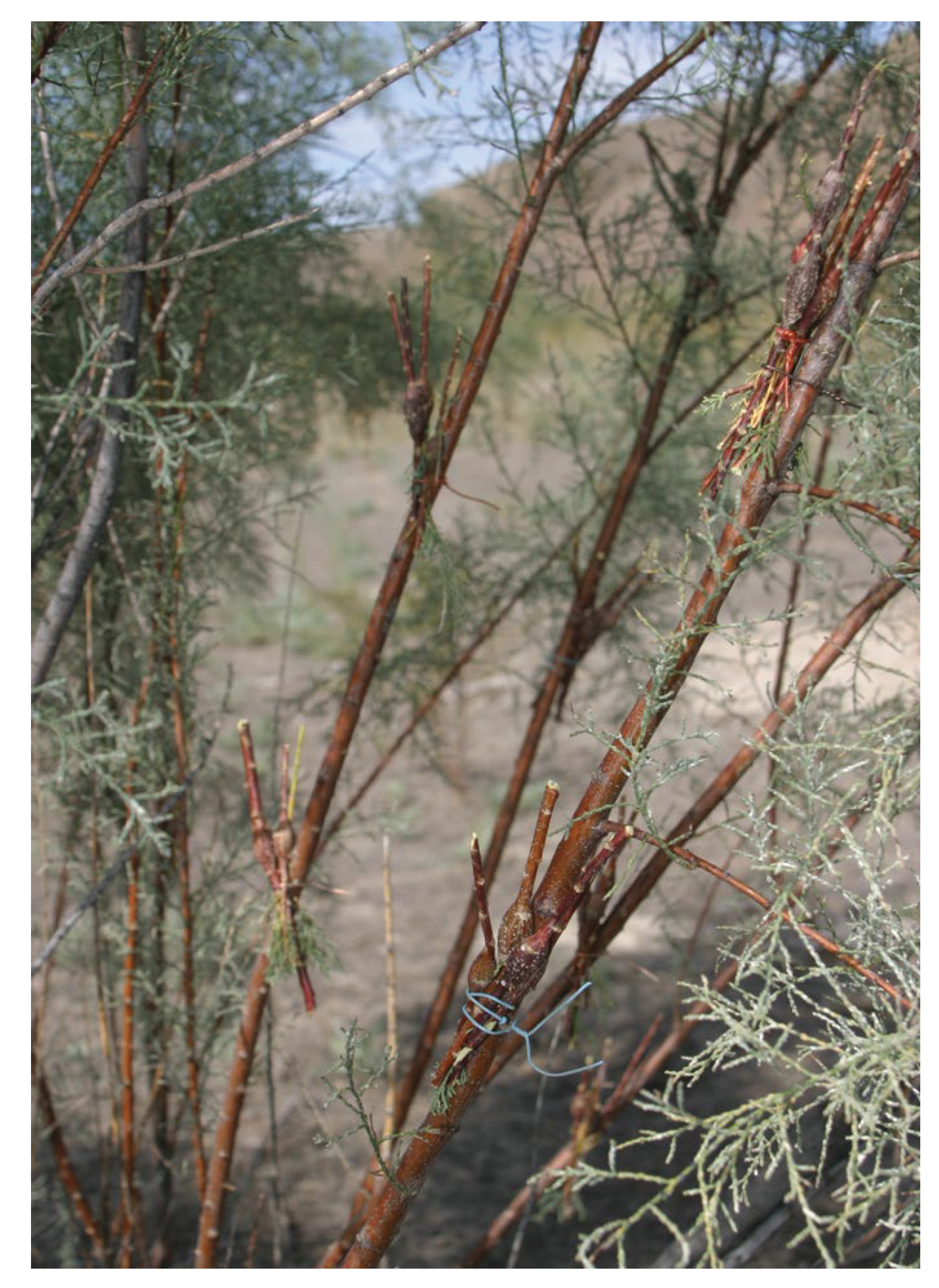

The narrow oligophagous gall-forming moth, Amblypalpis tamaricella Danilevsky, 1955, which causes severe damage to tamarisk in the wild, is one of the most promising biological agents for the biological control of saltcedars in the United States. The species is known from the deserts of Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan (southeastern Kyzylkum), southern and southeastern Kazakhstan, and Mongolia (Altai Gobi). The species develops in a single generation per year, with eggs overwintering. In many bushes, not only individual branches but the entire crown is affected, and by the following spring, such plants die. Studies of the biological characteristics of this species across seven moth populations in Kazakhstan have shown a high degree of conservatism in host-plant use: females typically lay their eggs on the same plant on which they hatched. The introduction of the moth into the United States should ideally occur during the pupal stage, before it emerges as an adult in late September to early October.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Biological and Phenological Peculiarities

3.1.1. General Life Cycle and Phenology

3.1.2. Phenology

3.1.3. Population Number and Harmful Effect

3.1.4. Parasites and Predators

3.2. Testing of Amblypalpis Tamaricella on American and Local Biotypes of Tamarix

3.3. Techniques of Transportation and Breeding of Amblypalpis tamaricella

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- DeLoach, C.J.; Carruthers, R.I.; Lovich, J.E.; Dudley, T.L.; Smith, S.D. Ecological Interactions in the Biological Control of Saltcedar (Tamarix spp.) in the United States: Toward a New Understanding. In Proceedings of the X International Symposium on Biological Control of Weeds, Bozeman, MT. Montana State University, MT, 2000; pp. 819–873. [Google Scholar]

- Baum, B.R. The Genus Tamarix; Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities: Jerusalem, Israel, 1978; pp. 1–209. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, T.W. Introduction, spread, and areal extent of saltcedar (Tamarix) in the western states. USDI Geol. Surv. Professional Paper 1965, 491-A, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Baum, B.R. Introduced and naturalized tamarisks in the United States and Canada (Tamaricaceae). Baileya 1967, 15, 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Crins, W.L. The Tamaricaceae in the southeastern United States. J. Arnold Arboretum 1989, 70, 403–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaskin, J.F.; Schaal, B.A. Hybrid Tamarix widespread in U.S. invasion and undetected in native Asian range. Proc. of the Nat. Acad. of Sci. 2002, 99, 11256–11259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaskin, J.F.; Schaal, B.A. Molecular phylogenetic investigation of U.S. invasive Tamarix. Systematic Botany 2003, 28, 86–95. [Google Scholar]

- Gaskin, J.F.; Shafroth, P.B. Hybridization of Tamarix ramosissima and T. chinensis (saltcedars) with T. aphylla (athel) (Family Tamaricaceae) in the southwestern USA determined from DNA sequence data. Madroño 2005, 52, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A dictionary of the following plants and ferns. (Eighth Edition); Willis, J.C., Shaw, H.K Airy, Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1993; pp. 1–1245. [Google Scholar]

- Mityaev, I.D.; Jashenko, R.V. Nasekomye vrediteli tamariska v Yugo-Vostochnom Kazakhstane (=Insects—pests of Saltcedar in South-East Kazakhstan); Tethys: Almaty, Kazakhstan, 2007; pp. 1–180. [Google Scholar]

- DeLoach, C. Jack; Carruthers, Raymond I.; Dudley, Tom L.; Eberts, Debra; Kazmer, David J.; Knutson, Allen E.; Bean, Daniel W.; Knight, Jeff; Lewis, Phil A.; Milbrath, Lindsey R.; Tracy, James L.; Tomic-Carruthers, Nada; Herr, John C.; Abbott, Gregory; Prestwich, Sam; Harruff, Glenn; Everitt, J. H.; Thompson, David C.; Mityaev, Ivan; Jashenko, Roman; Li, Baoping; Sobhian, Rouhollah; Kirk, Alan; Robbins, Thomas O.; Delfosse, Ernest S. First results for control of saltcedar (Tamarix spp.) in the open field in the western United States. In Proceedings of the XI International Symposium on Biological Control of Weeds. Canberra, Australia, CSIRO Entomology, 2004; pp. 505-513.

- Jashenko, R.V.; Mityaev, I.D.; DeLoach, C.J. New potential agents for tamarisk biocontrol in US. 2006 Tamarisk Research Conference: Current Status and Future Directions, Ft. Collins, Colorado, USA, 3-4 October 2006; p. 75. [Google Scholar]

- Jashenko, R.V.; Mityaev, I.D.; DeLoach, C.J. Tamarix biocontrol in US: new biocontrol agents from Kazakhstan. In Proceedings of the XII International Symposium on Biological Control of Weeds, Le Grand Motte, France, 22–27 April 2007; p. 253. [Google Scholar]

- Fasulati, K.K. Polevoe Izuchenie Nazemnykh Bespozvonochnykh; (=Field study of terrestrial invertebrates); Vyshaya shkola: Moscow, Russia, 1961; pp. 1–304. [Google Scholar]

- Marikovskiy, P.I. Tamariskovaya moli — Amblypalpis tamaricella Dan. i yavlenie sopryazhennoy diapausy eiyo parazita (=Tamarix gall moth Amblypalpis tamaricella Dan and phenomen of conjugated diapauses of its parasite). Zool. Zhurnal 1952, 31(5), 673–675. [Google Scholar]

- Danilevsky, A.S. Novye vidy nizshikh cheshuekrylykh (Lepidoptera, Microheterocera), vredyaschie drevesnym I kustarnikovym porodam v Sredney Azii (=New species of lepidopterans (Lepidoptera, Microheterocera) harming trees and bushes in Middle Asia). Entomol. Obozr. 1955, 34, 108–123. [Google Scholar]

- Mityaev, I.D. Obzor nasekomukh—vrediteley tamariskov Balkhash-Alakulskoy vpadiny (=Review of insects harming tamarisks of Balkhash-Alakol depression). In Trudy of Instituta Zoologii Akademii Nauk Kazakhskoy SSR; Institute of Zoology: Alma-Ata, Kazakhstan, 1958; pp. 74–97. [Google Scholar]

- Daricheva, M.A. K biologii nekotorykh cheshuekrylykh, vredyaschikh rastitelinosti nizoviy Murgaba (=On the biology of some lepidopteran insects that damage vegetation in the lower reaches of the Murghab River). Izv. Akad. Nauk. Turkm. SSR Ser. Biol. Nauk. 1963, 1, 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Lvovskiy, A.L.; Piskunov, V.I. Gelekhiidnye moli (Lepidoptera, Gelechiidae) Altaiskogo Gobi (=Gelechiid’s moths (Lepidoptera, Gelechiidae) of Altai Gobi). Nasekomye Mongolii 1989, 10, 521–571. [Google Scholar]

- Marikovskiy, P.I. Muravii pustyn Semirechiya (=Ants of desert of Semirechie); Gylym: Alma-Ata, Kazakhstan, 1979; pp. 1–264. [Google Scholar]

| April | May | June | July | August | September | October | November | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decades | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||||||

| we | we | we | e | C1 | C1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| C2 | C2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gl | Gl | Gl | Gl | Gl | Gl | Gl | Gl | Gl | Gl | Gl | Gl | Gl | Gl | Gl | Gl | |||||||||||||||

| C3 | C3 | C3 | C3 | C3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| C4 | C4 | C4 | C4 | C4 | C4 | C4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| C5 | C5 | C5 | C5 | C5 | C5 | C5 | C5 | C5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| p | p | p | p | p | p | p | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| b | b | b | b | b | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| e | e | we | we | we | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).