1. Introduction

The availability of new multifunctional (nano)materials and optoelectronic components has resulted in much research on novel colourimetric sensors for the detection and monitoring of analytes, especially for use at the Point-of-Need (PoN) [

1,

2,

3,

4]. The applications of colourimetric sensors range from biomedicine, Point-of-Care (PoC) diagnostics, wearable devices, to food safety, agricultural and environmental monitoring, so there is a broad demand for functional sensors from these markets. Despite recent advances in rapid manufacturing technologies and ease of miniaturisation to micron scale features, the functional design of colourimetric materials that are both reversible and selective remains a challenge to the realisation of real-time optical chemical sensors as integrated analytical devices. Here, we address some of the functional challenges with the introduction of a biocompatible and flexible colourimetric thin-film sensor with fully reversible response to magnesium ions and pH.

Metal ions play a vital role in the regulation of biological and environmental processes [

5,

6], so monitoring of their presence and concentration is important across many application areas. Magnesium ion is vital to physiological processes and organisms [

7], and for environmental [

8] and agricultural balance in natural systems [

9]. Besides the use of established ion-selective electrodes for the detection and quantification of Mg

2+ [

10], various optical sensors have been reported [

11]. These include colourimetric [

12,

13], fluorescent [

14,

15,

16] and surface plasmon-based devices [

17]. The advantages of the simpler colourimetric sensors include a visible colour change that may be interpreted by the naked eye, operation with low-cost and portable instrumentation such as colour meters and photometers, may be mass produced on sustainable/green substrate materials such as paper and textiles, and may be used with commonly available mobile phone cameras [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. Metal ion sensors can suffer from irreversible binding to the target ion and cross-sensitivity to interferent ions present in the sample due to strong binding constants. Reversibility may nonetheless be achieved with the right combination of substrate, indicator, analyte and immobilisation technique [

23]. Choice of substrate material is therefore important and influences the ultimate reversibility of the sensor, its biocompatibility and wearability. Lastly, it is known that

Mg2+ ion sensors often suffer from cross-sensitivity and interference to Ca2+ that is present in body fluids and environmental samples which is problematic for calibration [

11]

.

Colourimetric sensors for metal ions may utilise established reversible ionophore systems like ion-selective optodes [

24], gold and silver nanoparticle platforms [

25], and organic chromophores [

26]. Organic chromophores for pH and metal ion-sensing are typically Brønsted acidic/basic dyes or Lewis acid/base dyes, respectively, that change their absorption properties upon (de)protonation or complexation with metal ions. Ionochromic dyes are strong coordination ligands for colourimetric complexation of metal ions, and their immobilisation into polymer substrates is crucial in the design of stable sensing materials. Of the available immobilisation methods, covalent immobilisation of indicator dye directly to the solid substrate provides the greatest stability and durability and minimises leaching of the dye [

27,

28].

One of the most biocompatible and biodegradable sensor substrate materials is cellulose [

29,

30], although many biopolymers and their hydrogels are known to be suitable [

31,

32,

33,

34]. But the natural abundance, surface hydrophilicity, enhanced analyte diffusion, and high density of surface hydroxyls make cellulose a primary choice of substrate material [

35,

36]. Cellulose can be used in a variety of forms, including paper, film and nanofibers, moreover regenerated cellulose-based substrates like cellophane have good transparency, mechanical strength and are likely compatible with microfluidics - all of which are prerequisites for next-generation wearable sensors and continuous real-time monitoring [

37].

Established metal-ion indicators containing an

o,o’ dihydroxy azobenzene complexation moiety, such as Eriochrome Black T (EBT) and Eriochrome Blue Black R (EBB), have been reported for the determination of transition metal ions, for Mg

2+ and Ca

2+ and for water hardness testing [

38,

39,

40,

41]. The structurally similar, but less well explored chelator, Hyphan I [

42] has previously been used for the extraction of transition metal ions from complex mixtures [

43]. Here, Hyphan I, 1-(2-hydroxy-5-ß-hydroxyethylsulfonyl-phenyl-azo)-2-naphthol, is used as a precursor for covalent immobilisation on cellulose. We anticipated that the combination of Hyphan I, a multifunctional chelating molecule, with a cellulose substrate would result in a new sensing material with enhanced optical properties and appropriate p

Ka and binding constants for reversible response. Hyphan I was therefore grafted onto cellulose in a simple one-pot vinylsulfonyl process to form a transparent, biocompatible and highly flexible thin-film colourimetric sensing material (Cellulose Film with Hyphan - CFH). The characterisation of CFH as an ion sensor shows a fast and fully reversible response to pH and Mg

2+ in physiologically relevant ranges without cross-sensitivity to Ca

2+. This work demonstrates the future potential of CFH-based sensors to function as wearable and in-line microfluidic analytical devices for biofluid monitoring.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

Chemicals for the synthesis of the dye were of reagent grade while chemicals for the immobilisation of the dye to cellulose (concentrated sulphuric acid, sodium hydroxide, sodium carbonate), buffers and chloride salts of alkali and alkaline earth metal ions for spectral evaluation (tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane (Tris), sodium dihydrogen phosphate, sodium acetate, sodium sulphate, boric acid, magnesium chloride hexahydrate, calcium chloride dihydrate, sodium chloride and potassium chloride) were all of analytical reagent grade. 2-Amino-4-(2-hydroxyethylsulfonyl)-phenol was obtained from Merck. The regenerated cellulose layers with a thickness of 35 µm were from Innovia (NatureFlexTM 35 NP), Futamura Chemical Co. Ltd.

2.2. Synthesis of the Chromoionophore Hyphan I

The synthesis was performed according to a procedure described by Burba

et al. [

42]. Here, 1.47 g (6.8 mmol) of 2-amino-4-(2-hydroxyethylsulfonyl)-phenol was suspended in 2.2 mL (13.2 mmol) of 6 N hydrochloric acid and an additional 1.4 mL of distilled water and cooled to below 5 °C. To this, a solution of 0.28 g (4.1 mmol) of sodium nitrite in 2 mL of distilled water was added, and the resulting orange-brown suspension was stirred for 20 minutes at 5 °C and filtered. This filtrated diazotisation solution was slowly added to an ice-cooled solution of 0.58 g (4.0 mmol) of 2-naphthol previously dissolved in 2 mL of ethanol, and added to 0.2 g (5.0 mmol) of sodium hydroxide and 1.0 g (9.4 mmol) of sodium carbonate in 20 mL of distilled water. The resulting mixture was stirred for 3 hours. Then, it was acidified with 5 mL of 6 N hydrochloric acid to precipitate the red-brown dye. Column chromatography using dichloromethane/acetone (2:1) as the eluent gave red crystals.

1H-NMR (DMSO): d (ppm) 16.24 (s, 1H, -OH),

11.85 (s, 1 H, -OH), 8.43 (d, 1 H, =CH-), 8.32 (s, 1 H, =CH-), 7.93 (d, 1 H, =CH-), 7.67 (m, 3 H, =CH-), 7.47 (d, 1 H, =CH-), 7.20 (d, 1 H, =CH-), 6.78 (d, 1 H, =CH-), 4.93 (s, 1 H, -OH), 3.73 (t, 2 H, -CH

2-), 3.52 (t, 2 H, -CH

2-). Mass spectral analysis: 373,0 Da [MH+]. Yield: 20%.

2.3. Fabrication of Sensor Layers

Hyphan I indicator molecules were immobilised on transparent cellulose film (CFH) following the common procedure used for transparent cellulose, textiles and wipes [

44]. In a typical immobilisation procedure, 50 mg of the dye was treated with 0.5 mL of concentrated sulfuric acid for 30 min at room temperature. This converts the hydroxyethylsulfonyl group of the indicator dye into the corresponding sulfonate. The sulfonated mixture was then poured into 400 mL of distilled water, and 1 mL of 32% sodium hydroxide solution was added to it for neutralisation. After placing the cellulose film for 5 minutes in this solution, 12.5 g of sodium carbonate in 100 mL of water was added to it, followed by the addition of 2.5 mL of 32% sodium hydroxide solution after 5 minutes. The sulfonated dye was converted into the chemically reactive vinylsulfonyl derivative in the prevailing basic condition, and in turn, vinylsulfonyl groups underwent Michael addition with the hydroxyl groups of the cellulose film. After 30 min, the indicator immobilised cellulose layers were removed from the dyeing bath and washed with distilled water.

2.4. Measurements

For the pH-dependent sensing studies, Britton Robinson and Tris buffer solutions were used. The wide pH range Britton Robinson buffer was prepared using 0.04 M sodium acetate, 0.04 M boric acid, 0.04 M sodium dihydrogen phosphate, and 0.1 M sodium sulphate. For the interference-specific studies at pH 7.4 and 8.0, 50 mM Tris buffer was employed. 1.0 M aqueous sodium hydroxide and 1.0 M aqueous hydrochloric acid were used for pH adjustments of the buffer solutions. pH measurements were carried out using a WTW pH electrode SenTix 62. The optical responses of the Hyphan I immobilised cellulose (CFH) film corresponding to various pH and metal ion concentrations were collected using a Shimadzu UV-1280 UV-visible spectrometer in the absorbance mode. For this, the CFH film was cut according to the cuvette dimensions and placed against the cuvette wall, followed by the addition of different pH buffer solutions and metal ion concentrations into the cuvette. The sensing responses were then gathered by collecting the absorbance spectra.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Choice of Sensing Material

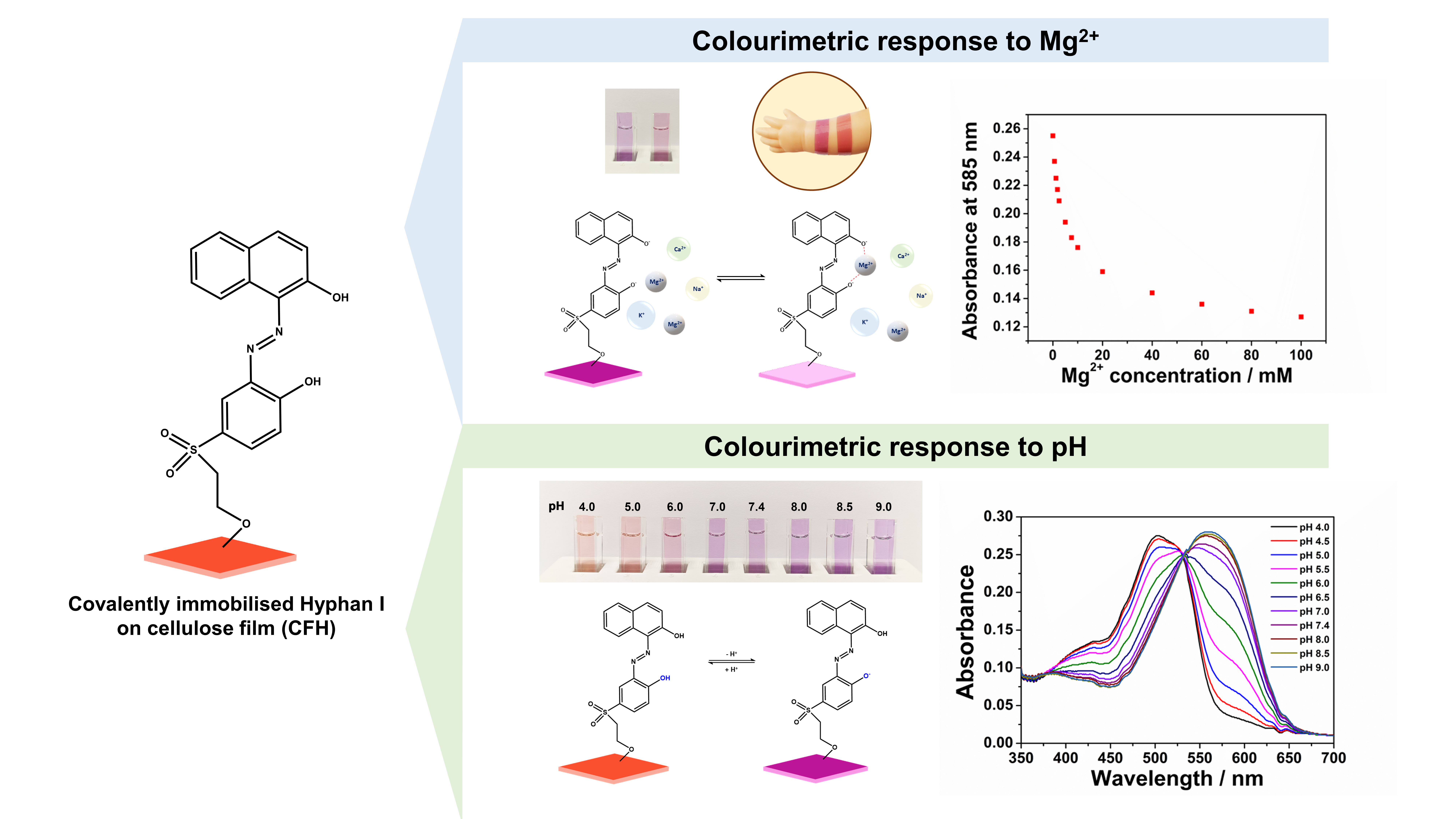

The colourimetric sensing material designed for this study was fabricated by covalent immobilisation of the azo indicator dye Hyphan I, 1-(2-hydroxy-5-ß-hydroxyethylsulfonyl-phenyl-azo)-2-naphthol, onto transparent cellulose films,

Figure 1.

The dye contains naphtholic and phenolic hydroxyl groups, providing pH and metal ion complexation sites, while the hydroxyethylsulfonyl group at the end of the molecule can be used for grafting onto a cellulose film. Hyphan I is the same class of naphthol-type pH indicator dye together with Nitrazine Yellow and Naphthol Orange. It can serve as a pH indicator due to its ability to change colour with varying pH conditions. The dye molecule contains an

o,o’-dihydroxy azobenzene moiety, similar to Erichrome Black T (EBT) and Erichrome Blue Black R (EBB) indicators, that are known for complexation of heavy metal and alkaline earth metal ions and which are used in various applications, including the removal of heavy metal ions from drinking water [

38,

40,

42].

The covalent immobilisation of the dye is based on a simple one-pot vinylsulfonyl chemistry, schematically shown in

Figure 1 [

44,

45,

46]. Typically, the molecule is first converted to a sulfonate in acidic conditions, followed by conversion to a chemically reactive vinylsulfonyl derivative under basic conditions. The vinylsulfonyl groups react with hydroxyl groups of the cellulose via Michael addition, providing a covalent attachment of the molecule onto the cellulosic material.

The resulting sensing material, CFH, is a 35 μm thick, transparent, biocompatible and highly flexible cellulose film covalently functionalised with Hyphan I colourimetric indicator. It is known that in most cases, indicators retain their complexation properties upon immobilisation, however, with altered selectivity, sensitivity, reversibility and response times - characteristics also strongly related to the physical and chemical properties of the substrate [

23,

29]. Cellulose films are particularly compatible with wearable, epidermal monitoring applications [

47,

48,

49], and the following steps of this study included characterisation of CFH as a potential pH and metal ion sensing material.

3.2. pH Sensitivity of the CFH Sensing Layer

The spectral pH sensing performance of the cellulose film CFH was tested in pH buffers over the pH range 4.0-9.0,

Figure 2.

The UV-visible absorption spectra show a bathochromic shift upon deprotonation of the hydroxyl group in Hyphan I, from 502 nm to 560 nm with a clear isosbestic point at 532 nm. This is manifested as a visible colour change of the sensor layer from orange-red to purple, as proposed by the equilibrium,

Figure 3. It is known that both phenolic groups in a similar molecule, EBT, are protonated at pH < 6 [

39]. Given their similar structure, deprotonation of the Hyphan I molecule most likely follows the same deprotonation scheme, as shown in

Figure 3. However, it is known that both the acid-base and the tautomeric azo-hydrazone equilibria occur within the

o,o’-dihydroxy azobenzene moieties in aqueous solutions, which additionally may affect the indicator properties when in immobilised form.

Deprotonation of the hydroxyl group causes a shift of the absorption peak to a longer wavelength (from 502 nm to 560 nm), which is expected and can be explained by the enhanced electron donor strength of the anionic -O

- phenolate group relative to the phenolic hydroxyl group -OH [

50]. The film responds to pH changes reversibly, with a response time of less than 1 minute. The corresponding pH equilibrium constant, p

Ka = 5.84, is calculated from the calibration curve fitted with the Boltzmann model, for six repetitive cycles of pH measurements using the same film,

Figure 2b and

ESI Figure S1. The standard deviations and relative standard deviations corresponding to each pH were found to be less than 0.0058 and 4.0%, respectively. The regression coefficient,

R2 = 0.9999, confirmed good fit of the experimental data to the theoretical Boltzmann model.

The spectral response of the CFH film in the range pH 7.0-9.0 was also tested in Tris buffer,

Figure 2c. Tris buffer is used in biological analysis due to its minimal ion content. The corresponding pH titration plots in Britton-Robinson and Tris buffers are shown,

Figure 2d. The optical responses observed in the two buffers are in good agreement, with the small differences ascribed to the different ionic compositions. It is interesting to note that at pH 7.4, which corresponds to physiological pH, the optical response of CFH in each buffer coincides.

3.3. Response to Metal Ions

Eriochrome Blue Black R is a structurally equivalent ligand to Hyphan I and forms complexes with different transition metals, amongst which Zn

2+, Cu

2+ and Fe

3+ show the highest formation constants [

41]. The response of CFH towards these ions was investigated in a flow-through cell at pH 7.4,

Figure 4a and

Figure 4b.

Figure 4a shows the change in absorbance with increasing Zn

2+ concentration from 0.1 to 0.4 mM. The response is not reversible, and after 2 hours, the initial signal of the CFH could not be recovered with buffer at pH 7.4. However, complete recovery of the initial baseline signal was achieved with 0.1 M HCl. A similar trend in reversibility was observed for Cu

2+ and Fe

3+ ions too,

Figure 4b. The flow-through cell experiments confirmed the strong, irreversible binding of transition metal ions to the CFH film.

Unlike the transition metal ions, Mg

2+ exhibited a fully reversible response in a concentration range from 2.50 mM to 100 mM over two consecutive reversible cycles lasting 6 hours,

Figure 4c. This unique reversible binding affinity of the CFH towards Mg

2+ ions can be partially attributed to its smaller ionic size, higher charge density and higher hydration energy [

51,

52]. Reversibility and stability in continuous use are essential requirements for real-time monitoring applications.

3.4. Response to Mg2+

3.4.1. Effect of pH on Mg2+ Response

The absorbance of CFH film at Mg

2+ concentrations of 1.25, 5.00 and 20.0 mM was studied at pH 7.4 and 8.0. The measured change in absorbance is shown,

Figure 5.

Greater changes in absorbance were observed at pH 8.0 compared to pH 7.4 for all three Mg2+ concentrations. The increased response to Mg2+ at pH 8.0 is the result of deprotonation of the Hyphan I phenolic -OH groups, which in turn increases the fraction of coordination sites available for Mg2+. Therefore, further Mg2+ sensing studies were carried out under the optimum pH of 8.0. Additionally, to evaluate the sensing performance of CFH under physiological pH conditions, the latter sections also include sensing studies at pH 7.4.

3.4.2. Effect of Na+, K+, Ca2+ on Mg2+ Response

Three known interferent alkali and alkaline earth metal ions commonly present in physiological environments (Na

+, K

+, Ca

2+) were tested together with Mg

2+, in Tris buffer at pH 7.4 and 8.0, and the corresponding optical responses were measured,

Figure 6a and

Figure 6b.

For each alkali/alkaline earth metal ion, the optical absorbance was determined at three different concentrations: 1.25, 5.00, and 20.0 mM. The responses generated by Na+, K+ and Ca2+ were compared to those of Mg2+. At pH 8.0, the measured absorbance change for 20 mM of Mg2+ was found to be -36.6% of the initial blank, while Na+, K+ and Ca2+ showed changes of +0.38%, +1.92% and -0.77%, respectively.

The lack of a response to Ca

2+ was unexpected, given its strong complexation with the structurally related Eriochrome indicators. The high selectivity to magnesium over calcium ion is a considerable advantage of the CFH material in comparison with similar colourimetric, indicator-based systems, especially for application in biofluids where the typical concentration of these ions is usually similar [

11].

3.4.3. Dynamic Range and Calibration Plots

The UV-visible absorbance spectra of CFH film in Mg

2+ solutions (0 to 100 mM) were measured,

Figure 7a. The absorbance around 585 nm decreases with increasing Mg

2+ concentration,

Figure 7b. The absorbance values at 585 nm were fitted to a Boltzmann model with a regression coefficient

R2 = 0.9998,

Figure 7c.

Even though the CFH exhibited a dynamic range up to 100 mM for Mg2+, the most sensitive and more physiologically relevant range is to 20 mM. The choice of working range depends on various factors such as required accuracy, reproducibility, reversibility and the field of application. Based on these considerations, the CFH was evaluated from 0 to 5 mM of Mg2+. This has physiological relevance since Mg2+ in human sweat typically lies in this concentration range.

The repeatability of the CFH is shown,

Figure 8a. Here, the absorbance was measured over 6 repeated cycles (

n=6) in increments from 0, 0.625, 1.25, 1.875, 2.5 to 5.0 mM Mg

2+ ion concentration (

ESI Figure S2). The standard deviation and relative standard deviation corresponding to each Mg

2+ concentration were found to be less than 0.0021 and 0.93%, respectively. Upon fitting the data to a Boltzmann model, a calibration plot was obtained with a regression coefficient

R2 = 0.9984,

Figure 8b. The calibration function is given by

equations 1 and

2

3.4.4. Reversibility

Reversibility of ion sensors is necessary for continuous real-time monitoring applications and is an important feature required of wearable sensors. The reversibility of the CFH to Mg

2+ ion under dynamic flow conditions was described in

Section 3.3. In addition, the reversibility of the CFH was evaluated in static cuvette tests. The CFH was alternately exposed to 0 and 5 mM Mg

2+ solutions in Tris buffer at pH 8.0 over 5 repeated cycles, and the corresponding UV-visible absorption spectra measured,

Figure 9a. The absorbance at 585 nm obtained over the five alternating cycles is shown,

Figure 9b. The CFH was observed to be reversible in the static cuvette tests, with a relative standard deviation of less than 0.57% at 0 mM and 5 mM.

The LOD and LOQ of the CFH for Mg

2+ at pH 8.0 are 0.089 mM and 0.318 mM, respectively, with an RSD of 0.93% (

ESI S3). The CFH exhibits a response time < 2 minutes to Mg

2+ ions in solution and has a stable and reversible response over 6-hour duration in a flow-through cell,

Figure 4c. In addition, we found that CFH remains functional over several years when stored in the dark under room temperature conditions, indicating it has a good shelf-life.

3.4.5. Real Sample Measurements

To evaluate the analytical performance of the CFH, three samples containing Mg

2+ were tested. The first sample was a laboratory-prepared solution having 0.625 mM Mg

2+ along with 5 mM of each Na

+, K

+ and Ca

2+ ions. The other two samples were commercially available mineral water samples: Rommerquelle

® and Mg

++ Mivela

®. All three samples were tested for Mg

2+ after adjusting the pH to 8.0. The absorption at 585 nm was converted to concentration using the calibration function,

Table 1. The colourimetric response of the CFH in mineral water Mg

++ Mivela

® is shown in

ESI Figure S1, and the Mg

2+ concentrations corresponding to the observed optical responses were found to agree with the declared values with a maximum relative error of 5.6%.

4. Conclusion

In this work, a new and fully reversible optical sensor for pH and Mg2+ ions is demonstrated. Optical detection is based on a novel colourimetric responsive material, cellulose film with Hyphan I (CFH). To fabricate the CFH film, Hyphan I indicator is covalently immobilised on cellulose through the vinylsulfonyl group to hydroxyl groups present on the cellulose via a Michael addition. The resulting colourimetric film is transparent, thin, flexible and biocompatible with good optical properties. The CFH has a colourimetric response to pH and Mg2+ ions in solution, with an LOD and LOQ to Mg2+ of 0.089 and 0.318 mM, respectively, over a sensing range of 4.0-9.0 pH units with a response time of < 60s. The fast reversible colourimetric response and high selectivity to Mg2+ compared to Ca2+ and other common physiological ions make the CFH suitable for Mg2+ sensing in biomedical applications. However, CFH also shows strong irreversible binding to Zn2+, Cu2+ and Fe3+, and this should be taken into account in applications where transition metal ions might be present in the sample. Unlike many chelation-based sensors, where strong binding results in an irreversible response to metal ions, the CFH is fully reversible to Mg2+ in the physiological range up to 5 mM. This is the result of a synergistic combination of the covalently immobilised Hyphan I with the cellulose film microenvironment, where cellulose characteristics such as hydrophilicity, ion diffusion rate and surface hydroxyl density influence the optical properties and sensing performance of the indicator. The covalent immobilisation strategy ensures long-term stability of the sensor by preventing indicator leaching, and the simple vinylsulfonyl fabrication process is suitable for industrial scale-up. The CFH film demonstrates the necessary characteristics of a pH and Mg2+ ion-responsive optical sensor for continuous real-time monitoring and is suitable for incorporation into wearable devices.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: pH repetitive sensing cycle responses. Table S2: Mg2+ repetitive sensing cycle responses. Section S3: Calculation of LOD and LOQ. Figure S1: Colourimetric response of the CFH towards commercially available mineral water Mg++ Mivela®.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation GJM and IMS; methodology GJM, MDS, IMS; investigation IK, DJ, GJM, IMS; data curation IK, DJ, CS, GJM; writing—original draft preparation IK, DJ, IMS; writing—review and editing GJM, MDS, IMS; funding acquisition GJM and IMS.

Funding

This work was supported by the Croatian Science Foundation under the project WearSense HRZZ IP-2022-10-2595. CS and GJM are grateful for the financial support by the projects “MicroTex” (FO999915125) and “NanoFlow” (FO999899045) funded by the Austrian Research Promotion Agency (FFG), and by the project “NanoSensTex” under grant agreement n°825051 funded by the European Union Horizon 2020 program ACTPHAST 4R.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jin, Z.; Yim, W.; Retout, M.; Housel, E.; Zhong, W.; Zhou, J.; Strano, M. S.; Jokerst, J. V. Colorimetric sensing for translational applications: from colorants to mechanisms. Chemical Society Reviews 2024, 53(15), 7681–7741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnan, S.; Syed, Z. u. Q. Colorimetric Visual Sensors for Point-of-needs Testing. Sensors and Actuators Reports 2022, 4, 100078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Feng, J.; Hu, G.; Zhang, E.; Yu, H.-H. Colorimetric Sensors for Chemical and Biological Sensing Applications. Sensors 2023, Vol. 23, 2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnaghi, L. R.; Zanoni, C.; Alberti, G.; Biesuz, R. The colorful world of sulfonephthaleins: Current applications in analytical chemistry for “old but gold” molecules. Analytica Chimica Acta 2023, 1281, 341807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Shi, Q.; Song, N.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, L.; Chen, Z.; James, T. D. Current trends in the detection and removal of heavy metal ions using functional materials. Chemical Society Reviews 2023, 52(17), 5827–5860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Lai, Q. T.; Fan, W.; Zhang, Y. K.; Liu, Z. C., Advances in Portable Heavy Metal Ion Sensors. Sensors 2023, 23, (8).

- Maier, J. A.; Castiglioni, S.; Locatelli, L.; Zocchi, M.; Mazur, A. Magnesium and inflammation: Advances and perspectives. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology 2021, 115, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mousavi, S. A.; Khodadoost, F. Effects of detergents on natural ecosystems and wastewater treatment processes: a review. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2019, 26(26), 26439–26448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Zhang, B.; Bozdar, B.; Chachar, S.; Rai, M.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Hayat, F.; Chachar, Z.; Tu, P., The power of magnesium: unlocking the potential for increased yield, quality, and stress tolerance of horticultural crops. 2023, Volume 14 - 2023.

- Shao, Y.; Ying, Y.; Ping, J. Recent advances in solid-contact ion-selective electrodes: functional materials, transduction mechanisms, and development trends. Chemical Society Reviews 2020, 49(13), 4405–4465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lvova, L.; Gonçalves, C. G.; Di Natale, C.; Legin, A.; Kirsanov, D.; Paolesse, R. Recent advances in magnesium assessment: From single selective sensors to multisensory approach. Talanta 2018, 179, 430–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majidi, B.; Amiri, A.; Badiei, A.; Shayesteh, A. Dual mode colorimetric-fluorescent sensor for highly sensitive and selective detection of Mg2+ ion in aqueous media. Journal of Molecular Structure 2020, 1213, 128156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-Y.; Shinde, S.; Ghodake, G. Colorimetric detection of magnesium (II) ions using tryptophan functionalized gold nanoparticles. Scientific Reports 2017, 7(1), 3966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brady, M.; Shchepetkina, V. I.; González-Recio, I.; Martínez-Chantar, M. L.; Buccella, D. Ratiometric Fluorescent Sensors Illuminate Cellular Magnesium Imbalance in a Model of Acetaminophen-Induced Liver Injury. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2023, 145(40), 21841–21850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Yu, X.; Li, M.; Liao, N.; Bi, A.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, S.; Gong, Z.; Zeng, W. Fluorescent probes for the detection of magnesium ions (Mg2+): from design to application. RSC Advances 2018, 8(23), 12573–12587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paderni, D.; Macedi, E.; Lvova, L.; Ambrosi, G.; Formica, M.; Giorgi, L.; Paolesse, R.; Fusi, V., Selective Detection of Mg2+ for Sensing Applications in Drinking Water. Chemistry-a European Journal 2022, 28, (49).

- Amirjani, A.; Salehi, K.; Sadrnezhaad, S. K. Simple SPR-based colorimetric sensor to differentiate Mg2+ and Ca2+ in aqueous solutions. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 2022, 268, 120692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kant, T.; Shrivas, K.; Tejwani, A.; Tandey, K.; Sharma, A.; Gupta, S. Progress in the design of portable colorimetric chemical sensing devices. Nanoscale 2023, 15(47), 19016–19038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zhuang, J.; Wei, G. Recent advances in the design of colorimetric sensors for environmental monitoring. Environmental Science: Nano 2020, 7(8), 2195–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N. A.; Hendricks, A.; Montoya, E.; Mayers, A.; Rajmohan, D.; Morrin, A.; McCaul, M.; Dunne, N.; O’Connor, N.; Spanias, A.; Raupp, G.; Forzani, E. New Imaging Method of Mobile Phone-Based Colorimetric Sensor for Iron Quantification. Sensors 2025, Vol. 25, 4693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Concepcion, R. S.; Sta. Agueda, J. R. H.; Marquez, J. C. Optimization of Dye and Plasticizer Concentrations in Halochromic Sensor Films for Rapid pH Response Using Bird-Inspired Metaheuristic Algorithms. Sensors 2025, Vol. 25, 3494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarara, M.; Tzanavaras, P. D.; Tsogas, G. Z. Development of a Paper-Based Analytical Method for the Colorimetric Determination of Calcium in Saliva Samples. Sensors 2023, Vol. 23, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaGasse, M. K.; Rankin, J. M.; Askim, J. R.; Suslick, K. S. J. S.; Chemical, A. B. Colorimetric sensor arrays: Interplay of geometry, substrate and immobilization. 2014, 197, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X. J.; Bakker, E. Ion selective optodes: from the bulk to the nanoscale. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry 2015, 407(14), 3899–3910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, G.; Zanoni, C.; Magnaghi, L. R.; Biesuz, R. Gold and Silver Nanoparticle-Based Colorimetric Sensors: New Trends and Applications. Chemosensors 2021, Vol. 9, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, B.; Kaur, N.; Kumar, S. Colorimetric metal ion sensors - A comprehensive review of the years 2011-2016. Coordination Chemistry Reviews 2018, 358, 13–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidgans, B. M.; Krause, C.; Klimant, I.; Wolfbeis, O. S. Fluorescent pH sensors with negligible sensitivity to ionic strength. Analyst 2004, 129(7), 645–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanjanzadeh, H.; Park, B.-D. Covalent immobilization of bromocresol purple on cellulose nanocrystals for use in pH-responsive indicator films. Carbohydrate Polymers 2021, 273, 118550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, L.; Tian, H.; Lu, A. Universal preparation of cellulose-based colorimetric sensor for heavy metal ion detection. Carbohydrate Polymers 2020, 236, 116037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, L.; Liu, H.; Peng, F.; Qi, H. Efficient and portable cellulose-based colorimetric test paper for metal ion detection. Carbohydrate Polymers 2021, 274, 118635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Li, X.; Li, J.; Xie, Z.; Chang, G. Synthesis of a “Turn-On” Mg2+ fluorescent probe and its application in hydrogel adsorption. Journal of Molecular Structure 2023, 1281, 135085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalitangkoon, J.; Monvisade, P. Synthesis of chitosan-based polymeric dyes as colorimetric pH-sensing materials: Potential for food and biomedical applications. Carbohydrate Polymers 2021, 260, 117836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, A.; Haag, R.; Schedler, U. Hydrogels and Their Role in Biosensing Applications. 2021, 10(11), 2100062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeman, N. H.; Arsad, N.; A Bakar, A. A. J. S. Polysaccharides as the sensing material for metal ion detection-based optical sensor applications. 2020, 20(14), 3924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klemm, D.; Kramer, F.; Moritz, S.; Lindström, T.; Ankerfors, M.; Gray, D.; Dorris, A. Nanocelluloses: A New Family of Nature-Based Materials. 2011, 50(24), 5438–5466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, Y.; Lucia, L. A.; Rojas, O. J. Cellulose Nanocrystals: Chemistry, Self-Assembly, and Applications. Chemical Reviews 2010, 110(6), 3479–3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigemori, H.; Maejima, K.; Shibata, H.; Hiruta, Y.; Citterio, D. Evaluation of cellophane as platform for colorimetric assays on microfluidic analytical devices. Microchimica Acta 2023, 190(2), 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diehl, H.; Lindstrom, F. Eriochrome Black T and Its Calcium and Magnesium Derivatives. Analytical Chemistry 1959, 31(3), 414–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamed, M. M. A.; Ismail, N. M.; Ibrahim, S. A. SOLVENT CHARACTERISTICS IN THE SPECTRAL BEHAVIOR OF ERIOCHROME-BLACK-T. Dyes and Pigments 1994, 26(4), 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yappert, M. C.; DuPre, D. B. Complexometric Titrations: Competition of Complexing Agents in the Determination of Water Hardness with EDTA. Journal of Chemical Education 1997, 74(12), 1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoud, M. S.; Hammud, H. H.; Beidas, H. Dissociation constants of eriochrome black T and eriochrome blue black RC indicators and the formation constants of their complexes with Fe(III), Co(II), Ni(II), Cu(II), Zn(II), Cd(II), Hg(II), and Pb(II), under different temperatures and in presence of different solvents. Thermochimica Acta 2002, 381(2), 119–131. [Google Scholar]

- Burba, P. Hyphan — ein analytischer Azo-Chelatbildner zur Extraktion von Schwermetallspuren, speziell von Cu und U. Fresenius. Zeitschrift für analytische Chemie 1981, 306(4), 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burba, P. Labile/inert metal species in aquatic humic substances: an ion-exchange study. Fresenius’ Journal of Analytical Chemistry 1994, 348(4), 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, G. J.; Wolfbeis. O. S. J. A. c. a., Optical sensors for a wide pH range based on azo dyes immobilized on a novel support. 1994, 292(1-2), 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, G. J.; Kassal, P.; Žuvić, I.; Krawczyk, K. K.; Steinberg, M. D.; Steinberg, I. M. J. M. A. Design of halochromic cellulosic materials and smart textiles for continuous wearable optical monitoring of epidermal pH. 2025, 192(7), 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, M. J.; Orbe-Payá, I. d.; Ortega-Muñoz, M.; Vilar-Tenorio, J.; Gallego, D.; Mohr, G. J.; Capitán-Vallvey, L. F.; Erenas, M. M. Capillary microfluidic platform for sulfite determination in wines. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2022, 359, 131549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Luo, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Xiao, J.; Xu, T.; Zhang, X. J. C. M. Epidermal wearable optical sensors for sweat monitoring. 2024, 5(1), 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavrinsky, E.; Esfahani, N. E.; Hausner, M.; Kuzma, A.; Rezo, V.; Donoval, M.; Kosnacova, H. The Current State of Optical Sensors in Medical Wearables. 2022, 12(4), 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yetisen, A. K.; Martinez-Hurtado, J. L.; Ünal, B.; Khademhosseini, A.; Butt, H. Wearables in Medicine. 2018, 30(33), 1706910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansch, C.; Leo, A.; Taft, R. W. A survey of Hammett substituent constants and resonance and field parameters. Chemical Reviews 1991, 91(2), 165–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, I. J. P.; Chemistry, A. Hydrated metal ions in aqueous solution: How regular are their structures? 2010, 82(10). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, R. D. J. F. o. C. Revised effective ionic radii and systematic studies of interatomic distances in halides and chalcogenides. 1976, 32(5), 751–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).