1. Introduction

Noncontact ACL injury is common in pivoting and landing sports and is disproportionately observed in girls and women, with sex differences emerging during adolescence. ACL rupture is not only a season-ending injury but also a potential inflection point for long-term knee symptoms and osteoarthritis risk. For adolescent athletes, an ACL tear may also alter athletic identity, scholarship trajectories, and lifetime physical activity (Silvers-Granelli, 2021).

Contemporary prevention has strong evidence for multi-component NMT programs, typically combining landing and cutting technique coaching, plyometrics, balance and perturbation tasks, and lower-limb strengthening. Prospective biomechanical work indicates that landing mechanics and valgus loading patterns can predict ACL injury risk in female athletes, supporting the emphasis on coached movement skill development (Hewett et al., 2005). Meta-analyses suggest meaningful risk reductions in female athletes when programs are delivered with adequate frequency, duration, and coaching quality. In broader sports injury prevention literature, strength training is among the most effective exercise modalities for reducing injury risk, reinforcing the value of progressive resistance training within prevention packages (Lauersen et al., 2014). However, even in well-resourced environments, ACL injuries persist, and at the community level, adherence and dose are often insufficient. These realities motivate two parallel aims: (i) improve implementation of what already works, and (ii) identify high-yield, modifiable targets that can be added to existing programs without destabilizing feasibility (Myer et al., 2013; Sugimoto et al., 2016).

The hamstrings are a biologically plausible candidate target because they can generate posterior tibial shear and contribute to dynamic knee stability. In cadaveric and model-based work, hamstring loading can reduce anterior tibial translation and ACL force across clinically relevant flexion angles. Yet the specific hamstring quality that matters most for ACL protection in real-world tasks is uncertain. In many injury situations, the knee is near extension and the hip is flexed, creating long hamstring muscle lengths while the limb experiences rapid loading. This suggests that eccentric capacity at long muscle lengths may be a more task-relevant descriptor than generic peak torque measured at mid-range angles (Li et al., 1999; Shimokochi and Shultz, 2008; Yu and Garrett, 2007).

The current manuscript synthesizes evidence across biomechanics, prospective risk factor studies, and eccentric training adaptations to motivate a testable hypothesis: improving hamstring eccentric capacity at long muscle lengths could reduce hazardous knee loading and, ultimately, ACL injury risk in adolescent female athletes. We then translate this hypothesis into a practical assessment and training framework and outline a research agenda for falsification.

2. Methods: Narrative Evidence Synthesis

This manuscript is a narrative evidence synthesis with an explicit translational aim. To improve transparency and rigor, the narrative review was developed using the principles of the Scale for the Assessment of Narrative Review Articles (SANRA), emphasizing a clear justification, a stated objective, a described literature search, appropriate referencing, and coherent scientific reasoning (Baethge et al., 2019).

We performed a targeted search of PubMed and Google Scholar (last updated December 2025) using combinations of the following terms: “ACL injury” OR “anterior cruciate ligament”; “female” OR “adolescent”; “hamstring”; “eccentric”; “Nordic”; “muscle length” OR “fascicle” OR “architecture”; and “hamstring-to-quadriceps” OR “H/Q ratio”. We prioritized: (i) systematic reviews and meta-analyses, (ii) prospective cohort studies examining intrinsic risk factors, and (iii) mechanistic studies quantifying ACL force/strain or knee kinematics under controlled loading. Because the focal construct (long-length hamstring eccentric capacity) is not yet a standard risk factor, we also included high-quality training studies that directly compared eccentric hamstring loading across muscle lengths.

Evidence was synthesized qualitatively. Given heterogeneity in measurement methods, populations, and outcomes, we did not attempt a de novo meta-analysis. Where evidence was indirect, we explicitly frame statements as mechanistic plausibility or hypothesis rather than established causal fact.

AI assistance statement: A large language model (ChatGPT, OpenAI) was used to assist with language polishing and structural editing. The author is solely responsible for the content, interpretation, and accuracy of citations, and verified all statements and references.

3. Evidence Base

3.1. Epidemiology and Developmental Considerations

Female athletes experience higher ACL injury rates than males in comparable sports, and the sex disparity becomes prominent during adolescence. This timing is consistent with the intersection of rapid growth, changes in body composition, and evolving neuromuscular control strategies. From a prevention perspective, adolescence is both a period of heightened vulnerability and a period of high trainability for movement skills and strength (Silvers-Granelli, 2021).

3.2. Mechanisms of Noncontact ACL Loading and the Role of the Hamstrings

Noncontact ACL injuries most commonly occur during rapid deceleration, landing, and cutting. Mechanistically, ACL loading is driven by a combination of anterior tibial shear, axial compressive forces, and multiplanar moments (valgus and internal rotation) depending on the task. Quadriceps contraction near knee extension increases anterior tibial shear, while hamstring activation can generate posterior tibial shear that partially counteracts this tendency (Shimokochi and Shultz, 2008; Yu and Garrett, 2007).

In vitro evidence supports this antagonistic role. For example, when knee extension is simulated under quadriceps loading, adding a hamstring load reduces anterior tibial translation, internal rotation, and in situ ACL force across flexion angles that overlap with common injury configurations (approximately 15 to 60 degrees), although protection appears reduced at full extension. This angle dependence matters because many injury events occur at relatively shallow knee flexion (Li et al., 1999).

3.3. Prospective Evidence on Strength Balance and ACL Injury Risk

Prospective cohort studies and systematic reviews have examined whether knee flexor strength or H:Q ratios predict ACL injury. Overall, the prognostic evidence is mixed. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis suggests that existing studies are heterogeneous and that the H:Q ratio has, at best, modest predictive value when considered in isolation. However, select cohorts report associations between lower H:Q ratios and subsequent noncontact ACL injury, including in young female soccer players. These findings support the general premise that relative hamstring weakness, particularly when paired with high quadriceps strength, may be a risk signature in some contexts (Kellis et al., 2023; Taketomi et al., 2024; Myer et al., 2009).

Crucially, most studies quantify strength in ways that may not reflect the joint angles and contraction modes relevant to injury. Conventional isokinetic testing often uses mid-range angles, and field devices frequently emphasize peak Nordic force. Neither necessarily captures the ability to generate eccentric knee flexor torque at shallow knee flexion while the hip is flexed. If ACL injury risk is driven by failure to control tibial motion during rapid loading near extension, then angle-specific and position-specific hamstring capacity may be the more relevant construct.

3.4. Hamstring Adaptations to Eccentric Training and the Special Case of Long Muscle Lengths

Eccentric hamstring training reliably increases eccentric strength and can alter muscle architecture, including increases in biceps femoris fascicle length. These adaptations are frequently discussed in the context of hamstring strain prevention, but they may also be relevant to knee stabilization because longer fascicles and greater eccentric capacity could permit higher force production at longer lengths and higher lengthening velocities (Gérard et al., 2020).

Importantly, eccentric training effects depend on how and where in the range of motion the muscle is loaded. Studies that compare eccentric training performed at long versus short muscle lengths show larger or more functionally relevant architectural and strength adaptations when training emphasizes longer lengths. For the hamstrings, long-length protocols typically combine hip flexion with knee extension or otherwise bias the hamstrings toward longer fascicle operating lengths during peak loading (Marušič et al., 2020).

The Nordic hamstring exercise is a practical and well-studied knee-dominant eccentric that can be implemented in teams. Meta-analytic evidence supports a substantial reduction in hamstring strain injuries when Nordic programs are performed with adequate compliance. However, the Nordic is performed with relatively extended hip positions, and therefore may not fully replicate the hip-flexed, long-length hamstring conditions observed during high-risk deceleration tasks. This motivates the inclusion of hip-dominant long-length eccentrics (e.g., Romanian deadlift variations and hip extension eccentrics) alongside knee-dominant eccentrics (van Dyk et al., 2019).

3.5. Evidence for Neuromuscular Training and Implications for Integration

Exercise-based NMT programs remain the most evidence-supported approach to reducing ACL injury risk in young female athletes. Successful programs share a common profile: they are multi-component, coached, and dosed sufficiently (frequency and total weeks) to drive adaptation. From an intervention design perspective, the hamstring-strength hypothesis should not be treated as a replacement for NMT, but as a candidate modular addition. The practical question is whether explicitly targeting long-length hamstring eccentric capacity improves biomechanical surrogates beyond standard NMT and whether any such improvements translate to fewer injuries (Myer et al., 2013; Sugimoto et al., 2016).

4. Working Hypothesis and Conceptual Model

Working hypothesis: In adolescent female athletes, insufficient hamstring eccentric capacity at long muscle lengths may be a modifiable contributor to hazardous anterior tibial shear and coupled multiplanar knee loading during rapid deceleration, landing, and cutting. Improving this capacity through progressive long-length eccentric training, integrated within an NMT package, is hypothesized to improve surrogate markers of knee loading and may reduce ACL injury incidence compared with standard NMT alone.

This hypothesis rests on four propositions that can be empirically tested:

1) ACL loading during common injury tasks is highest at shallow knee flexion and under rapid loading.

2) Hamstring co-contraction can reduce anterior tibial translation and ACL force at these angles, but only if sufficient force is produced quickly and at long muscle lengths.

3) Adolescent females, on average, have lower hamstring strength (and often lower H:Q ratios) than males and may display neuromuscular strategies that increase knee loading.

4) Long-length eccentric training can increase hamstring strength and alter architecture in ways that plausibly increase force capacity at long lengths.

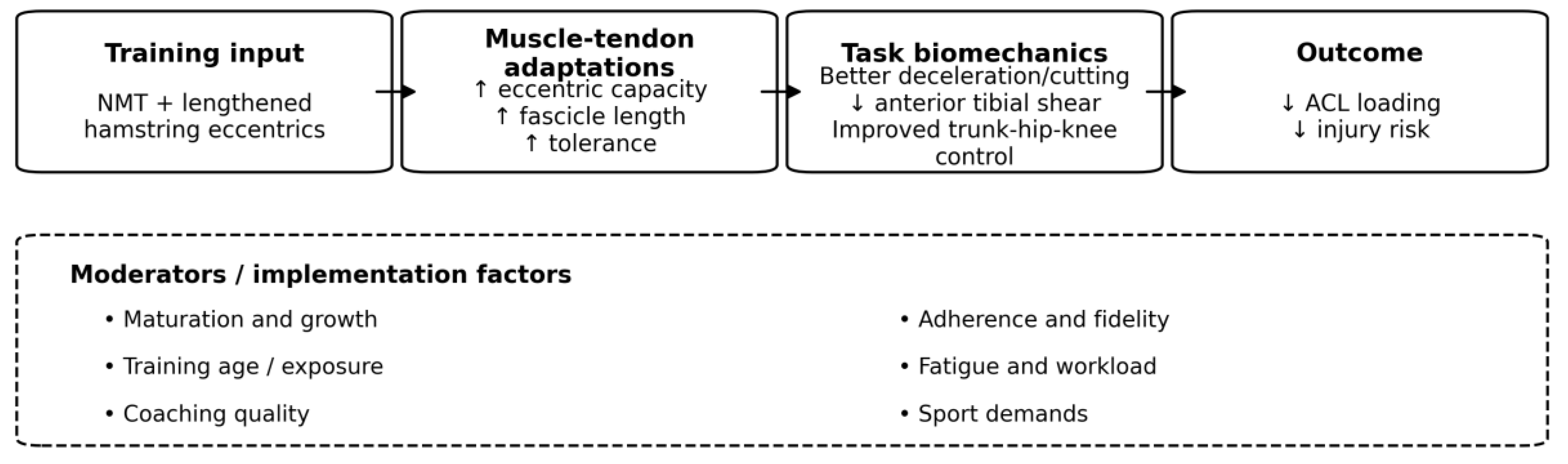

Figure 1.

Conceptual pathway linking long-length hamstring eccentric capacity to reduced ACL loading and injury risk (hypothesized).

Figure 1.

Conceptual pathway linking long-length hamstring eccentric capacity to reduced ACL loading and injury risk (hypothesized).

5. Translational Prevention Framework

5.1. Assess: What to Measure (and What not to Overinterpret)

A credible prevention target must be measurable, modifiable, and actionable. For long-length hamstring eccentric capacity, the ideal assessment would quantify eccentric knee flexor torque near knee extension while the hip is flexed, with acceptable reliability in the field. In practice, teams may combine complementary measures rather than relying on a single number.

Recommended assessment domains:

A) Strength: eccentric knee flexor strength (Nordic device if available), and if feasible, angle-specific isokinetic knee flexor torque at shallow knee flexion.

B) Architecture (optional): ultrasound-derived fascicle length of the biceps femoris long head, when expertise is available.

C) Movement: landing and cutting tasks emphasizing trunk control, knee valgus, and braking strategy.

D) Capacity and exposure: sprint and deceleration volumes, training load, and recent changes in workload.

5.2. Prescribe: Exercise Selection and Progression

The goal is not to add random hamstring exercises but to deliberately load the hamstrings eccentrically in positions that bias long muscle lengths. This typically requires a blend of knee-dominant eccentrics (for practical eccentric overload) and hip-dominant eccentrics (to incorporate hip flexion and lengthen the hamstrings further). For adolescents, progression must be conservative enough to manage soreness and technique but aggressive enough to drive adaptation.

Table 1.

Examples of exercise options that emphasize long-length hamstring eccentrics.

Table 1.

Examples of exercise options that emphasize long-length hamstring eccentrics.

| Category |

Exercise |

Long-length bias |

Notes for adolescent females |

| Knee-dominant |

Nordic hamstring (assisted if needed) |

High knee extension range |

Use assistance early; progress gradually. |

| Knee-dominant |

Sliding leg curl (eccentric focus) |

Knee extension with hip elevated |

Lower entry barrier than Nordic; good for home and team settings. |

| Hip-dominant |

Romanian deadlift (bilateral and single-leg) |

Hip flexion plus near-extended knee |

Technique coaching critical; controlled eccentrics. |

| Hip-dominant |

45-degree hip extension (eccentric emphasis) |

Hip flexion with hamstring load |

Start bodyweight; avoid lumbar extension. |

| Mixed |

Long-lever bridge variations (eccentric lowering) |

Hip extension demand with long lever |

Early progression option. |

| Plyometric integration |

Deceleration drills with coached braking |

Task-specific lengthening under load |

Dose carefully; prioritize quality and gradual exposure. |

5.3. Periodize: Minimal Effective Dose and Season Planning

Eccentric hamstring loading must be periodized around the sport calendar and the athlete’s overall training load. For most adolescent team settings, a practical template is: 8 to 12 weeks of progressive loading in pre-season or early season, followed by 1 to 2 maintenance exposures per week in-season. A key implementation constraint is delayed-onset muscle soreness (DOMS), which can be substantial after Nordic and other high-tension eccentrics, particularly in novices (van Dyk et al., 2019).

Table 2.

Example weekly microcycle integration (illustrative, not prescriptive).

Table 2.

Example weekly microcycle integration (illustrative, not prescriptive).

| Phase |

Frequency |

Hamstring eccentric focus |

Integration with NMT |

| Foundation (weeks 1-3) |

2x/week |

Assisted Nordic or sliders; 2-3 sets of 4-6 slow ecc reps |

Pair with basic landing mechanics and balance tasks. |

| Build (weeks 4-8) |

2x/week |

Nordic progression + hip-dominant eccentrics; 3-4 sets of 4-8 reps |

Add plyometrics and cutting drills with feedback. |

| Performance (weeks 9-12) |

1-2x/week |

Heavier hip hinge eccentrics + Nordic maintenance; 2-3 sets |

Emphasize sport-specific deceleration and reactivity. |

| In-season maintenance |

1x/week |

Low-volume high-quality eccentrics; 1-2 sets |

Embed into warm-up or strength session; protect total load. |

5.4. Implementation: The Boring Details that Determine Success

Injury prevention fails in practice far more often because of implementation than because of physiology. For adolescent female athletes, the highest-yield implementation levers are: qualified coaching, consistent scheduling, and progressive loading that avoids excessive soreness early. Minimum standards include: (i) explicit coaching cues, (ii) objective progression criteria, and (iii) tracking adherence (sessions completed, not sessions planned) (Sugimoto et al., 2016).

Practical implementation recommendations:

1) Start with assisted variations and low volume in week 1; progress only when soreness is manageable and technique is stable.

2) Place high-eccentric sessions away from the highest-speed and highest-volume sport sessions when possible.

3) Treat the program as a system: hamstring eccentrics complement, but do not replace, landing and cutting technique coaching.

4) Track growth-related changes (rapid height increases) and adjust loading accordingly.

6. Research Agenda: How to Test (or Falsify) the Hypothesis

The central limitation of the current evidence base is that direct causal evidence linking long-length hamstring eccentric capacity to ACL injury reduction is sparse. Therefore, the hypothesis should be treated as provisional and subjected to falsifiable tests (Kellis et al., 2023).

6.1. Observational Studies

Prospective cohort studies should quantify hamstring eccentric capacity with joint-angle specificity and track ACL injuries with verified diagnoses. Key design priorities include: adequate sample size (given low incidence), standardized exposure measurement, and multivariable models that adjust for age, maturation, sport, prior injury, and workload.

6.2. Mechanistic Studies

Laboratory studies can test whether improvements in long-length hamstring eccentric strength change surrogate biomechanical outcomes during high-risk tasks, such as peak anterior tibial translation proxies, knee abduction moment, trunk positioning, and braking strategy. Importantly, these studies should include adolescent females and should report reliability and minimal detectable change for the chosen measures.

6.3. Pragmatic Intervention Trials

The decisive test is a pragmatic cluster randomized trial in youth female teams comparing standard NMT versus NMT plus a structured long-length hamstring eccentric module. Primary outcomes should include ACL injury incidence (when feasible) and a priori selected surrogate outcomes when injury counts are insufficient. Implementation outcomes (adherence, fidelity, time cost, and adverse events such as excessive DOMS) should be reported alongside efficacy outcomes.

7. Limitations

This manuscript is a narrative synthesis and therefore inherits the limitations of narrative review, including the risk of incomplete retrieval and selection bias. The proposed target (long-length hamstring eccentric capacity) is supported by mechanistic plausibility and converging evidence, but direct causal evidence for ACL injury reduction is not yet established. Additionally, field-based assessments may not perfectly capture the relevant joint positions and contraction dynamics, and training responses may vary with maturation status.

8. Conclusions

ACL injury prevention for adolescent female athletes has strong evidence for neuromuscular training, but persistent injury rates justify targeted refinement. We propose that long-length hamstring eccentric capacity is a plausible, modifiable target that may complement standard prevention packages by improving posterior shear capacity and deceleration control in joint configurations associated with noncontact injury. The hypothesis is testable and should be evaluated in prospective cohorts and pragmatic trials. In the meantime, integrating progressive long-length hamstring eccentrics within NMT is a rational, low-cost adjustment provided it is implemented with appropriate progression and coaching.

Ethics

Not applicable (no new human or animal data were collected).

Data availability

Not applicable.

Conflicts of interest

The author declares no competing interests.

Abbreviations

ACL, anterior cruciate ligament; NMT, neuromuscular training; H:Q, hamstring-to-quadriceps strength ratio; BF, biceps femoris; RDL, Romanian deadlift.

References

- Baethge, C; Goldbeck-Wood, S; Mertens, S. SANRA-a scale for the assessment of narrative review articles. Research Integrity and Peer Review 2019, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gérard, R; Gojon, L; Decleve, P; Van Cant, J. The effects of eccentric training on biceps femoris architecture and strength: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Journal of Athletic Training 2020, 55(5), 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hewett, TE; Myer, GD; Ford, KR; et al. Biomechanical measures of neuromuscular control and valgus loading of the knee predict anterior cruciate ligament injury risk in female athletes: a prospective study. The American Journal of Sports Medicine 2005, 33(4), 492–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kellis, E; Katis, A; et al. Hamstrings-to-quadriceps strength ratio and anterior cruciate ligament injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Sport and Health Science 2023, 12(3), 343–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G; Rudy, TW; Sakane, M; et al. The importance of quadriceps and hamstring muscle loading on knee kinematics and in-situ forces in the ACL. Journal of Biomechanics 1999, 32(4), 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauersen, JB; Bertelsen, DM; Andersen, LB. The effectiveness of exercise interventions to prevent sports injuries: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2014, 48(11), 871–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marušič, J; Vatovec, R; Marković, G; Šarabon, N. Effects of eccentric training at long-muscle length on architectural and functional characteristics of the hamstrings. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports 2020, 30(11), 2130–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myer, GD; Ford, KR; Barber Foss, KD; Liu, C; Nick, TG; Hewett, TE. The relationship of hamstrings and quadriceps strength to anterior cruciate ligament injury in female athletes. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine 2009, 19(1), 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myer, GD; Sugimoto, D; Thomas, S; Hewett, TE. The influence of age on the effectiveness of neuromuscular training to reduce anterior cruciate ligament injury in female athletes: a meta-analysis. The American Journal of Sports Medicine 2013, 41(1), 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimokochi, Y; Shultz, SJ. Mechanisms of noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injury. Journal of Athletic Training 2008, 43(4), 396–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvers-Granelli, H. Why female athletes injure their ACL’s more frequently? What can we do to mitigate their risk? International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy 2021, 16(4), 971–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, D; Myer, GD; McKeon, JM; Hewett, TE. Critical components of neuromuscular training to reduce ACL injury risk in female athletes: meta-regression analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2016, 50(20), 1259–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taketomi, S; Kawaguchi, K; Mizutani, Y; et al. Intrinsic risk factors for noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injury in young female soccer players: a prospective cohort study. The American Journal of Sports Medicine 2024, 52(12), 2972–2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Dyk, N; Behan, FP; Whiteley, R. Including the Nordic hamstring exercise in injury prevention programmes halves the rate of hamstring injuries: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 8459 athletes. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2019, 53(21), 1362–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, B; Garrett, WE. Mechanisms of non-contact ACL injuries. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2007, 41 Suppl 1, i47–i51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).