Submitted:

22 December 2025

Posted:

22 December 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Newtonian Gravity and Its Explanatory Domain

3. Desmos Theory and the Interaction Functional

4. Newtonian Gravity as a Special Case of Desmos Theory

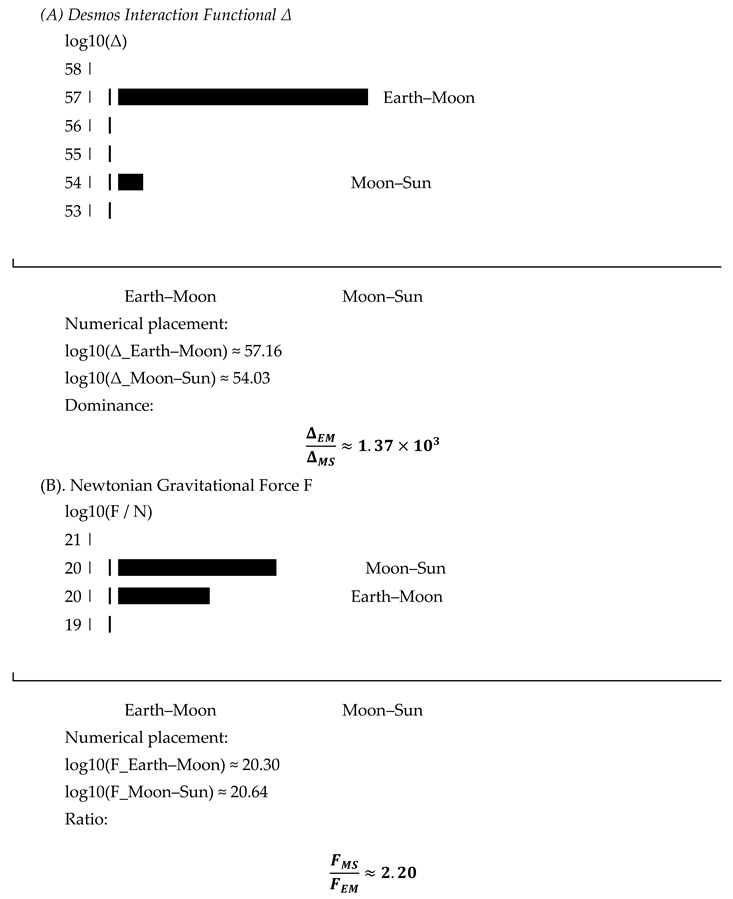

5. The Moon Case

6. Axiomatic Status of Binding Dominance

7. Desmos as a Connection Theory: A Holistic View of Causality

7.1. Desmos to General Relativity

7.2. Energetic and Quantum Correspondence

8. Conclusions

Appendix A

Appendix B

| Symbol | Physical meaning | SI unit |

|---|---|---|

| Mass of body | kg | |

| Source mass generating gravitational field | kg | |

| Distance between bodies and | m | |

| Radial distance from source mass | m | |

| Newtonian gravitational constant | m3 kg−1 s−2 | |

| Speed of light in vacuum | m s−1 | |

| Newtonian gravitational force | N (kg m s−2) | |

| Acceleration of body | m s−2 | |

| Newtonian gravitational potential | m2 s−2 | |

| Desmos potential proxy () | m2 s−2 | |

| Desmos energy variable () | J (kg m2 s−2) | |

| Desmos binding-dominance functional | J2 m−n | |

| Desmos interaction scaling constant | mn J−2 | |

| Desmos interaction exponent | dimensionless | |

| Time–time metric component (GR) | dimensionless | |

| Relativistic Desmos potential proxy | m2 s−2 | |

| Reduced Planck constant | J s | |

| Angular frequency (quantum correspondence) | s−1 | |

| Quantum occupation number (formal correspondence) | dimensionless | |

| GR-consistent Desmos interaction | J2 m−n |

Appendix C

References

- Aguilera, M.; Moosavi, S.; Shimazaki, H. A unifying framework for mean-field theories of asymmetric kinetic Ising systems. Nature Communications. 2020, 12. [CrossRef]

- Alazard, D.; Sanfedino, F.; Kassarian, E. Non-linear dynamics of multibody systems: a system-based approach. abs/2505.03248; ArXiv. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babichev, E.; Izumi, K.; Noui, K.; Tanahashi, N.; Yamaguchi, M. Generalization of conformal-disformal transformations of the metric in scalar-tensor theories. Physical Review D 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bini, D.; Damour, T.; Geralico, A. Novel Approach to Binary Dynamics: Application to the Fifth Post-Newtonian Level. Physical Review Letters Retrieved from. 2019, 123 23, 231104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bini, D.; Damour, T.; Geralico, A. Sixth post-Newtonian local-in-time dynamics of binary systems. Physical Review D 2020, 102, 24061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blümlein, J.; Maier, A.; Marquard, P.; Schäfer, G. Fourth post-Newtonian Hamiltonian dynamics of two-body systems from an effective field theory approach. Nuclear Physics B. 2020a. [CrossRef]

- Blümlein, J.; Maier, A.; Marquard, P.; Schäfer, G. The fifth-order post-Newtonian Hamiltonian dynamics of two-body systems from an effective field theory approach: Potential contributions. Nuclear Physics B 2020b, 965, 115352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, A.; Walters, P. A multisite decomposition of the tensor network path integrals. The Journal of Chemical Physics 2021, 156 2, 24101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Z.-T.; Li, H.-D.; Chen, W. Quantum-Classical Correspondence of Non-Hermitian Symmetry Breaking. Physical Review Letters 2024, 134 24, 240201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Challoumis, C. Panphysics Enopiisis. Edelweiss Applied Science and Technology 2024, 8(6), 9356–9375. Available online: https://learning-gate.com/index.php/2576-8484/article/view/3999/1519. [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Sun, H.; Zheng, Y. Quantization of Carrollian conformal scalar theories. Physical Review D. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.-Q.; Ni, R.-H.; Song, Y.; Huang, L.; Wang, J.; Casati, G. Correspondence Principle, Ergodicity, and Finite-Time Dynamics. Physical Review Letters Retrieved from. 2025, 134 13, 130402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cun, Y. A Theoretical Framework for Back-Propagation. 1988. Available online: https://consensus.app/papers/a-theoretical-framework-for-backpropagation-cun/a73d81505d9459b9851c580c9288ec9f/.

- D’Ambrosio, F.; Heisenberg, L.; Kuhn, S. Revisiting cosmologies in teleparallelism. Classical and Quantum Gravity. 2021, 39. [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Fridman, M.; Lambiase, G. Testing the quantum equivalence principle with gravitational waves. Journal of High Energy Astrophysics 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A. The Meaning of Relativity. 1946. [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A. Einstein’s 1912 manuscript on the special theory of relativity : a facsimile. 2004. Available online: https://consensus.app/papers/einsteins-1912-manuscript-on-the-special-theory-of-einstein/65d18c179b09570a94db7c37b14d39cc/.

- Einstein, A. Albert Einstein to Michele Besso. Physics Today 2005, 58, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A. On the Relativity Problem. Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science 2007, 250, 1528–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A. Relativity: The Special and the General Theory, 100th Anniversary Edition. 2015a. Available online: https://consensus.app/papers/relativity-the-special-and-the-general-theory-100th-einstein/b27c2697bb9559cf98df9843d3bdcd00/.

- Einstein, A. Relativity: The Special and the General Theory. 2015b. [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A; Hawking, S. The Essential Einstein: His Greatest Works. 1995. Available online: https://consensus.app/papers/the-essential-einstein-his-greatest-works-einstein-hawking/47961fe0f91f548ba3742c11f0a7e70b/.

- Einstein, A; Rosen, N. The Particle Problem in the General Theory of Relativity. Physical Review 1935, 48, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einstein, Albert. The Bianchi Identities in the Generalized Theory of Gravitation. Canadian Journal of Mathematics 1950, 2, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fields, C.; Friston, K.; Glazebrook, J.; Levin, M. A free energy principle for generic quantum systems. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Gielen, S. Frozen formalism and canonical quantization in group field theory. Physical Review D 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, K.; Sugishita, S.; Tanaka, A.; Tomiya, A. Deep learning and the AdS/CFT correspondence. Physical Review D. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Heisenberg, L. A systematic approach to generalisations of General Relativity and their cosmological implications. Physics Reports. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Hess, P. Alternatives to Einstein’s General Relativity Theory. Progress in Particle and Nuclear Physics 2020, 114, 103809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Järv, L.; Kuusk, P.; Saal, M.; Vilson, O. Transformation properties and general relativity regime in scalar–tensor theories. Classical and Quantum Gravity. Retrieved from. 2015, 32. [CrossRef]

- Jarv, L.; Runkla, M.; Saal, M.; Vilson, O. Nonmetricity formulation of general relativity and its scalar-tensor extension. Physical Review D. Retrieved from. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, J. B.; Heisenberg, L.; Koivisto, T. The Geometrical Trinity of Gravity. Universe. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Leigh, N.; Wegsman, S. Illustrating chaos: a schematic discretization of the general three-body problem in Newtonian gravity. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society Retrieved from. 2018, 476, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi, M. Effective field theories of post-Newtonian gravity: a comprehensive review. Reports on Progress in Physics. 2018, 83. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lyu, S.-X.; Wang, Y.; Xu, R.; Zheng, X.; Yan, Y. Toward quantum simulation of non-Markovian open quantum dynamics: A universal and compact theory. Physical Review A. Retrieved from. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Liu, H.-Y.; Nguyen, D.; Tran, N. T. T.; Pham, H.; Chang, S.-L.; Lin, M.-F. The theoretical frameworks. 2020. [CrossRef]

- McTague, J.; Foley, J. Non-Hermitian cavity quantum electrodynamics-configuration interaction singles approach for polaritonic structure with ab initio molecular Hamiltonians. The Journal of Chemical Physics 2021, 156 15, 154103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mocz, P.; Lancaster, L.; Fialkov, A.; Becerra, F.; Princeton, P.-H. C.; Harvard, Toulouse. Schrödinger-Poisson–Vlasov-Poisson correspondence. Physical Review D Retrieved from. 2018, 97, 83519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, R.; Orr, B.; Al-Khateeb, S.; Agarwal, N. Constructing a multi-theoretical framework for mob modeling. Soc. Netw. Anal. Min. 2025, 15, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naruko, A.; Saito, R.; Tanahashi, N.; Yamauchi, D. Ostrogradsky mode in scalar-tensor theories with higher-order derivative couplings to matter. Progress of Theoretical and Experimental Physics. Retrieved from. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Nashed, G.; Bamba, K. Properties of compact objects in quadratic non-metricity gravity. Annals of Physics. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Ovalle, J. Decoupling gravitational sources in general relativity: The extended case. Physics Letters B. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Palariev, V.; Shtirbu, A. Theoretical framework of grape irrigation: a review. Collected Works of Uman National University of Horticulture. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.; Naseer, T.; Dayanandan, B. Interpretation of complexity for spherically symmetric fluid composition within the context of modified gravity theory. Nuclear Physics B. Retrieved from. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Sasmal, S.; Vendrell, O. Non-adiabatic quantum dynamics without potential energy surfaces based on second-quantized electrons: Application within the framework of the MCTDH method. The Journal of Chemical Physics 2020, 153 15, 154110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vacaru, S. Inconsistencies of Nonmetric Einstein–Dirac–Maxwell Theories and a Cure for Geometric Flows of f(Q) Black Ellipsoid, Toroid, and Wormhole Solutions. Fortschritte Der Physik. 2025, 73. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.-X.; Yan, Z. General theory for infernal points in non-Hermitian systems. Physical Review B. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Wiese, U.-J.; Einstein, A. Statistical Mechanics. Manual for Theoretical Chemistry. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ren, X.; Wang, Q.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, D.; Cai, Y.-F.; Saridakis, E. Quintom cosmology and modified gravity after DESI 2024. Science Bulletin. 2024. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).