1. Introduction

The concept of the meme, first articulated by Dawkins (1976) as a unit of cultural transmission analogous to a biological gene, has become central to understanding contemporary digital communication. In the age of social media, memes have evolved from simple textual or visual jokes into complex, multimodal cultural artifacts that combine images, video clips, sound, captions, and intertextual references. These artifacts circulate rapidly across platforms, mutate through user participation, and shape how individuals perceive reality, express emotions, and negotiate social identity. Scholars increasingly describe this phenomenon as a form of cultural contagion, where ideas spread through networks not merely by exposure, but through emotional resonance, social reinforcement, and algorithmic amplification (Shifman, 2014; Weng et al., 2013).

The metaphor of the ‘virus of the mind’ is particularly apt in the context of social media. Unlike traditional mass communication, digital platforms facilitate horizontal, peer-to-peer transmission of content, allowing memes to replicate at scale with minimal cost and effort. These cultural viruses do not require institutional gatekeepers; instead, they rely on imitation, remixing, and emotional engagement. Research shows that such content can influence attitudes, normalize behaviors, and shape collective interpretations of events, often faster than formal news media (Berger & Milkman, 2012). As a result, memes have become influential tools in political communication, youth culture, marketing, and everyday social interaction.

Generation Z occupies a central position in this memetic ecosystem. Born into a digitally saturated environment, Gen Z users are highly fluent in visual and participatory communication. Their preference for irony, humor, and short-form content aligns closely with meme-based expression. Memes function for Gen Z not only as entertainment but also as social currency—signals of belonging, political stance, emotional state, and cultural literacy (Pritts, 2022). Through memes, Gen Z negotiates identity, resists authority, copes with stress, and articulates collective experiences in compressed symbolic form.

Bangladesh presents a compelling and underexplored context for examining these dynamics. With a large youth population and rapidly expanding internet access, particularly via smartphones, social media has become embedded in everyday life. Platforms such as Facebook, TikTok, Instagram, and X serve as key arenas where Bangladeshi Gen Z exchanges humor, commentary, and critique. Memes circulating in this context often draw on Bangla language, local political events, popular culture, cricket, cinema, and shared experiences of education, unemployment, and social pressure. This localization process transforms global meme templates into culturally specific forms that resonate deeply with local audiences.

At the same time, Bangladesh’s socio-political environment heightens the significance of memetic communication. Periods of political tension, protest, or social controversy have frequently been accompanied by waves of meme production that frame events, assign blame, or mobilize sentiment. Memes can simplify complex issues into emotionally charged narratives, making them powerful yet potentially dangerous cultural viruses. When combined with algorithmic recommendation systems that prioritize engagement, such content can spread rapidly, sometimes contributing to misinformation, polarization, or social harm.

Existing scholarship on memes has largely focused on Western contexts, with comparatively limited attention to South Asia and Bangladesh in particular. Studies that do address memes in the Global South often emphasize political satire or marketing applications, leaving gaps in understanding how memes interact with youth cognition, emotional life, and cultural identity. Furthermore, much of the literature treats virality as a purely quantitative phenomenon, underplaying the role of meaning-making, language, and cultural codes that shape how memes are interpreted and shared.

This study addresses these gaps by conceptualizing memes as cultural viruses operating within a specific socio-cultural ecosystem. It integrates memetics, complex contagion theory, and socio-semiotics to examine how memes spread, mutate, and exert influence among Gen Z in Bangladesh. Rather than viewing memes solely as trivial entertainment or isolated viral events, the study treats them as patterned forms of cultural transmission that interact with network structures, platform affordances, and psychological processes.

The central objectives of this research are threefold. First, it seeks to analyze how Bangladeshi Gen Z creates and localizes memes, transforming global templates into culturally meaningful artifacts. Second, it examines the mechanisms of memetic spread, focusing on the roles of social networks, bridge actors, and algorithmic amplification. Third, it explores the cognitive and social implications of meme consumption and production, including their effects on identity formation, emotional regulation, and susceptibility to misinformation.

By framing memes as viruses of the mind, this article underscores their dual nature. On one hand, memes foster creativity, solidarity, and participatory culture, enabling young people to articulate shared experiences and critique power structures. On the other hand, the same mechanisms that make memes engaging and spreadable can facilitate the rapid circulation of harmful stereotypes, rumors, and emotionally manipulative narratives. Understanding this tension is essential for developing informed policy responses that protect freedom of expression while mitigating social harm.

In sum, this introduction positions the study at the intersection of digital culture, youth studies, and communication theory. By focusing on Bangladesh and Generation Z, it contributes a contextually grounded perspective to global debates on memes and cultural contagion. The sections that follow review relevant literature, outline the theoretical framework, describe the research methodology, and present findings that illuminate how memes function as powerful cultural viruses in the digital lives of Bangladeshi youth.

2. Significance of the Study

This study is significant on empirical, theoretical, social-policy, and methodological grounds. Below elaborate contributions and why a Bangladesh-focused study of Gen Z memetic practices matters now.

2.1. Empirical Significance: Documenting a Distinct Memetic Ecology

There is growing scholarly attention to memes globally, but comparatively less sustained empirical work that centers South Asian contexts—especially Bangladesh, where digital usage patterns and socio-political dynamics are unique. Bangladesh has a youthful population with high social-media penetration and a media ecologies shaped by Bengali language practices, local humor traditions, political contestation, and diasporic connections. Local platforms of expression, language play (code-switching between Bangla and English), and culturally specific templates (references to films, cricket, family structures, educational pressures) generate memes that require contextualized analysis. By documenting production practices, template adaptation, and circulation pathways among Gen Z in Bangladesh, this study fills an empirical gap and creates a baseline dataset for future comparative work.

2.2. Theoretical Significance: Integrating Memetics with Complex Contagion and Socio-Semiotics

The study develops a theoretical synthesis that treats memes simultaneously as: (a) replicable cultural units (memetics), (b) phenomena whose spread depends on social reinforcement and community structure (complex contagion models), and (c) semiotic texts embedded with indexical and intertextual meaning that users interpret and rework. Existing work shows that meme virality is not purely stochastic: early diffusion across diverse communities predicts large-scale virality (community-bridge theory), while meme mutation and template affordances affect longevity and resonance. Incorporating socio-semiotic perspectives foregrounds how meaning is co-constructed—what might look like the same image can serve different ideological functions in different sub-communities. This integration helps explain contradictions in memetic politics: the same meme format can foster cohesion (in-group humor) and exclusion (targeted mocking), and can be harnessed both for civic engagement and misinformation.

2.3. Social and Policy Significance: Balancing Expression and Harm Mitigation

As memes become central to political communication and social bonding, they raise regulatory and educational questions. In Bangladesh, memetic content has been implicated in body-shaming campaigns, rumor circulation during protests, and rapid mobilization of sentiment that sometimes escalates offline. Balancing free expression, youth cultural practices, and the need to guard against harms (defamation, incitement, harassment, rapid rumor spread) is delicate. This study supplies data-driven recommendations—targeted digital literacy curricula for Gen Z, platform-level moderation protocols sensitive to local language and humor contexts, and community-driven norms—that are sensitive to Bangladesh’s sociopolitical realities.

2.4. Methodological Significance: Mixed-Methods Model for Memetic Research

Memes resist easy quantification: they are multimodal (image, text, audio), creative (requiring intertextual knowledge), and relational (their meaning depends on sharing contexts). This study proposes and demonstrates a mixed-methods workflow combining (a) corpus collection and quantitative diffusion analysis (tracing repost chains and cross-platform propagation), (b) qualitative content analysis to identify frames and semiotic strategies, and (c) semi-structured interviews capturing user motives and interpretations. This approach can be a methodological template for researchers in similar cultural contexts.

2.5. Contribution to Youth Studies and Mental-Health-Informed Communication Research

Memes are not just communicative devices—they shape emotional landscapes. For Gen Z—who negotiate education pressures, economic precarity, and identity work online—memes often provide catharsis, solidarity, and humor. However, certain memetic practices also amplify anxiety, normalize harmful stereotypes, or trivialize serious topics. Understanding these dynamics offers insights for youth-focused mental-health interventions and communication strategies.

2.6. Digital Culture and Democratic Resilience

Memes can be vectors for civic learning (explainer memes, satirical critique) and can lower the barrier for political participation among young people. Conversely, they can propagate conspiracy narratives quickly. In Bangladesh’s sometimes-volatile political environment, memetic dynamics affect democratic resilience: how quickly rumors spread during protests, how different audiences read satire, and how in-group memes cement polarized identities. The study therefore has implications for civil-society actors working on fact-checking, civic education, and conflict de-escalation.

2.7. Cultural Preservation and Hybridization

Finally, this research shows how Gen Z negotiates global and local cultural flows. Memes imported from global templates are localized (Bangla captions, cricket metaphors, references to local celebrities), generating hybrid artifacts that reflect cultural negotiation and innovation.

This research is significant for several reasons. A) Empirically, it documents a distinct Bangladeshi memetic ecology shaped by language, youth culture, and political context. While global studies of memes are growing, empirical work focusing on Bangladesh remains limited. This study fills that gap by foregrounding local cultural references and Gen Z communicative practices.

B) Theoretically, the paper integrates memetics (Dawkins, 1976), complex contagion theory (Weng et al., 2013), and socio-semiotics to explain how memes acquire meaning and spread. This synthesis moves beyond simplistic viral metaphors by demonstrating that memetic diffusion depends on social reinforcement, interpretive communities, and algorithmic mediation.

C) Socially and politically, the study is relevant to debates on misinformation, digital well-being, and youth civic engagement. Memes can foster solidarity and political awareness, yet they also facilitate rumor cascades and harassment when emotionally charged content spreads unchecked. Understanding these dynamics is essential for designing culturally sensitive digital-literacy and governance interventions in Bangladesh.

D) Methodologically, the study demonstrates a mixed-methods approach suitable for researching multimodal digital culture, combining qualitative interpretation with insights from network science literature. Finally, the research contributes to youth studies by highlighting memes as tools of emotional expression and social capital for Gen Z, with implications for mental health and democratic resilience.

3. Literature Review

This review synthesizes three literatures: (1) foundational memetics and contemporary adaptations; (2) computational and network studies on meme virality; and (3) regionally relevant empirical literature on meme culture in South and Southeast Asia and Bangladesh.

3.1. From Dawkins to Online Memetics

Dawkins (1976) introduced the meme as a replicator in cultural evolution. While Dawkins’ biological metaphor has attracted critique, the idea that cultural items replicate, mutate, and experience selection pressures remains productive. Contemporary theorists refine memetics to account for intentional creativity in human-mediated replication—memes on the internet are not random mutations but deliberate re-creations shaped by aesthetic and humorous rules. Limor Shifman’s work reconceptualizes memes as multimodal, genre-like cultural forms whose success depends on both content and social practice, offering an analytic toolkit for classifying meme genres and affordances. Shifman (2013) emphasizes three key properties of memes: (1) they are spreadable, (2) they are replicable with variations, and (3) they are intertextual—users rework and reference existing cultural material.

3.2. Network Science and Contagion Models

Computational studies examine how network structure affects meme diffusion. Weng et al. (2013) and related work show that most memes behave like ‘complex contagions’ (requiring reinforcement from multiple sources), while a minority spread across many communities like biological diseases; early cross-community diffusion predicts eventual virality. Predictive models that use early diffusion patterns, community concentration metrics, and user centrality can forecast meme success with reasonable accuracy. These findings indicate that platform features affecting community clustering and recommender-system bridging play critical roles in memetic outcomes, (Weng, L., Menczer, F. & Ahn, Y-Y. 2013).

3.3. Attention Economy and Competition Among Memes

The attention economy frames memetic success as a zero-sum contest: limited human attention means memes compete for salience. Agent-based models and empirical studies show that template standardization (e.g., widely known image macros) facilitates rapid replication yet may reduce novelty; conversely, highly novel creative mutations can fail without community reinforcement. The tension between template familiarity and creative novelty is central to meme ecology, (Weng, L., et. al. 2012).

3.4. Memes as Socio-Political Tools

Research demonstrates that memes function in political persuasion, identity formation, and protest contexts. In several national cases, meme-based humor facilitated political mobilization, framing, and identity consolidation, while also enabling rapid rumor propagation. Memes can function both as low-cost political signals (easily shared jokes that encode stance) and as vectors for disinformation when paired with emotionally salient content.

3.5. Gen Z Communicative Practices and Memes

Generational studies show that Gen Z favors image- and video-rich, ephemeral, participatory content. Memes are central to Gen Z identity work: humor, irony, and shared references create in-group belonging and serve as social capital. Studies from South and Southeast Asia report that Gen Z uses memes for social bonding, political commentary, and brand engagement; meme marketing taps into these habits, but the line between authentic cultural production and commodified memetic content is contested, ( Putri, Salsa Della Guitara, et. at. 2024) ).

3.6. Bangladesh-Specific Studies

A nascent but growing body of work documents meme culture and related phenomena in Bangladesh. Analyses point to meme-driven body-shaming incidents, troll networks, and meme participation in student protests. Recent academic and university-published pieces analyze both positive functions (community formation, humor) and negative outcomes (harassment, rumor cascades). These empirical studies underline the need for context-aware policy interventions, digital literacy, and platform moderation attuned to Bangla language and cultural idioms.

Taken together, literature shows that (a) memes are multimodal cultural units whose success depends on content, network position, and platform affordances; (b) Gen Z’s communicative styles favor memetic participation; and (c) localized contexts (language, political culture) shape meme meaning. Gaps remain: few studies offer a comprehensive, interdisciplinary account combining network diffusion metrics, qualitative semiotic analysis, and interviews with creators/consumers in Bangladesh. This study addresses that gap.

4. Theoretical Framework

This study constructs a multi-layered theoretical framework to explain memetic dynamics among Bangladeshi Gen Z. It synthesizes three theoretical strands: memetics (cultural replication), complex contagion/network theory (diffusion mechanics), and socio-semiotics (meaning-making and identity). Below I outline each strand and then present an integrated model: the Gen Z Memetic Transmission Model (GM-TM).

4.1. Memetics: Memes as Replicators with Selection Pressures

Memetics conceptualizes cultural elements as replicators that propagate by imitation. On social media, replication is intentional and guided by creativity, humor, and strategic framing. Key memetic properties: fidelity (how well a meme template is preserved), fecundity (how easily it can be reproduced), and longevity (how long it remains salient). Successful memetic forms balance recognizable templates (high fidelity) with space for personalization (moderate mutation). In the Bangladeshi context, shared cultural repertoires (film dialogues, political slogans, cricket metaphors) increase template fecundity.

4.2. Complex Contagion and Network Structure

Network theory distinguishes simple contagions (single exposure sufficient) from complex contagions (multiple confirmations needed). Memes often act as complex contagions: users may adopt/share only after seeing them multiple times from trusted peers (social reinforcement). Weng et al. (2013) show that cross-community seeding (early spread across multiple clusters) predicts wide virality. For Bangladesh, where social media communities may be clustered by university, residential locality, or political affinity, bridge users (influencers, student leaders, diaspora connectors) are crucial in enabling cross-cluster diffusion. Recommendation algorithms that surface content across clusters can mimic the effect of bridge nodes by presenting content to diverse audiences.

4.3. Socio-Semiotics: Meaning Making, Intertextuality, and Identity

Memes are semiotic artifacts—images, captions, sounds that rely on intertextual knowledge. Socio-semiotics examines how signs carry indexical meanings (points to social categories), symbolic meanings (representations), and narrative scripts. For Gen Z, memes function as quick semiotic acts of identity: in-group humor, performative political statements, or ironic commentary. The same meme template can communicate solidarity within one community and derision in another. Understanding memetic impact thus requires attention to interpretive communities and semiotic repertoires.

4.4. Psychological Mechanisms: Emotion, Humor, and Cognitive Shortcuts

Memes leverage emotion (amusement, outrage, empathy) and cognitive shortcuts (stereotypes, archetypes) to enable fast processing and sharing. Humor reduces cognitive resistance to political messages; images lower the effort needed for comprehension. However, emotional arousal also increases sharing of misinformation. Gen Z’s preference for irony and layered humor sometimes masks literal meanings, complicating fact checking.

4.5. Platform Affordances and Algorithmic Mediation

Platform architectures (sharing mechanics, comment threading and short-form video loops) and recommender algorithms profoundly shape memetic ecology. Features like duet/remix (TikTok), resharing with comment (X/Threads), and meme templates (meme generators) lower production costs and increase mutation rates. Algorithms that prioritize engagement can amplify emotionally charged memes, regardless of veracity.

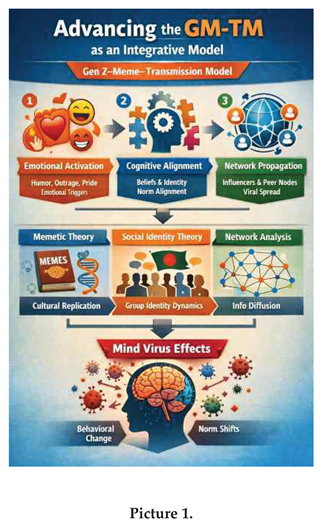

4.6. The Gen Z Memetic Transmission Model (GM-TM) — Integrated Model

GM-TM proposes that meme virality and effect in Bangladesh result from the interaction of five domains:

Template Ecology (T): Availability and adaptability of meme templates (global templates localized via Bangla language, cricket, films).

Network Structure (N): Community clustering, presence of bridge nodes, and algorithmic cross-seeding.

Semiotic Context (S): Interpretive repertoires, language-coded meanings, and intertextual references that shape message valence.

Psychological Drivers (P): Emotional valence, humor styles, identity signaling, and cognitive heuristics of Gen Z.

Platform Affordances (A): Production tools remix features, and algorithmic recommendation.

Virality VVV and socio-cultural effect EEE are functions of these interacting domains:

V=f(T,N,A);E=g(S,P,N,A)V = f(T, N, A) \quad ; \quad E = g(S, P, N, A)V=f(T,N,A);E=g(S,P,N,A)

Where fff and ggg are non-linear: small changes in network bridging or algorithmic prioritization can produce outsized increases in virality; semantic framing (S) interacts with psychological drivers (P) to determine whether a meme fosters bonding, ridicule, or rumor propagation.

4.7. Hypotheses Derived from GM-TM (for Empirical Testing)

H1: Memes that achieve early cross-community exposure (low community concentration) have a higher probability of large-scale virality, (Weng et al. (2013).

H2: Localized templates (Bangla text + local references) increase in-group resonance but lower cross-community spread unless mediated by bridge users.

H3: Highly emotionally arousing memes (outrage, strong humor) are more likely to be shared widely but are also more likely to be factually inaccurate or miscontextualized.

H4: Platform remix features (duet/remix) increase mutation rates and the speed of semiotic evolution.

4.8. Theoretical Implications

The GM-TM extends memetic thought by formally integrating semiotic and network dimensions and foregrounding platform mediation—arguing that memetics without attention to algorithmic affordances and interpretive communities provides an incomplete account of contemporary memetic dynamics. For policy, the model suggests leverage points: identifying bridge nodes for corrective messaging, designing platform interventions that slow rumor cascades, and cultivating digital literacy that sensitizes youth to semiotic ambiguity and manipulation.

5. Research Methodology

This study employs a mixed-methods design combining literature synthesis, corpus-based content analysis across platforms, and semi-structured interviews with Gen Z participants. The approach is explanatory and exploratory: mapping phenomena and generating testable hypotheses for future large-scale work.

5.1. Research Design Overview

Phase 1 — Literature and secondary-data synthesis: Systematic review of literature on memes, virality, and Gen Z communication (as summarized above).

Phase 2 — Corpus construction & quantitative diffusion analysis: Collection of a purposive corpus of memetic artifacts shared publicly in Bangladesh across Facebook public pages, TikTok, Instagram (public accounts), and X over a recent 18-month window (e.g., July 2023–Dec 2024). Sampling prioritized meme templates that (a) referenced local events, (b) showed evidence of cross-platform sharing, or (c) were widely shared within student/university networks. For diffusion metrics, repost chains, timestamp sequences, and cross-platform timestamps were used to compute community concentration and early spread metrics akin to Weng et al. (2013).

Phase 3 — Qualitative content analysis: Semiotic coding of 400 representative meme items to identify frames (satire, in-group humor, political critique, body-shaming, informational), rhetorical strategies, and intertextual references. Coding used an iterative thematic approach with intercoder reliability checks (Cohen’s kappa).

Phase 4 — Semi-structured interviews: 30 purposively sampled Gen Z participants (age 16–26) in Bangladesh, including meme creators (n≈12), frequent sharers (n≈10), and non-creator consumers (n≈8). Interviews explored motive for sharing, interpretation practices, perceived effects on identity and social relations, and attitudes toward platform moderation. Interviews were conducted in Bangla/English and transcribed for thematic analysis.

Phase 5 — Triangulation and model testing: Integration of quantitative diffusion patterns with qualitative themes and interview narratives to test components of the GM-TM.

5.2. Sampling and Ethical Considerations

Because memes often circulate in semi-public or closed groups, the corpus restricted to publicly available material and material for which share metadata was visible. Private messages or closed-group content was not collected without explicit consent. Interview participants gave informed consent; minors (16–17) participated only with parental consent and after institutional ethical approval. The study followed data protection norms: anonymization of usernames, redaction of personal identifiers, and secure storage of transcripts.

5.3. Data Collection Procedures

Corpus scraping and archiving: Public posts tagged with Bangladesh-related keywords, Bangla script, or geo-located metadata were sampled using platform APIs where available and manual collection for others (respecting Terms of Service). Each item recorded: platform, original upload time, poster account type (creator, page, news), repost/reshare counts (publicly visible), and textual metadata (captions, comments where visible).

Diffusion reconstruction: For each meme template selected, early diffusion windows (first 72 hours) were reconstructed by timestamp series to compute community concentration metrics and cross-community spread indicators, following methods adapted from Weng et al. (2013).

5.4. Variables and Operationalization

Virality (dependent variable): Multi-dimensional: reach (unique accounts exposed), spread velocity (shares per hour in early window), and cross-platform penetration (number of platforms on which the meme appears within 72 hours).

Independent variables: Template familiarity (global template vs. novel local template), language (Bangla vs. English vs. code-switch), emotional valence (humor, outrage, neutral), presence of bridge nodes (initial spreaders with cross-community ties), platform affordance indicators (presence of remix/duet features).

Qualitative codes: Frame type (satire, critique, identity reinforcement), target (political actor, celebrity, social practice), modality (image macro, short video, GIF), tone (ironic, mocking, supportive), and perceived intent (entertainment, persuasion, mockery).

5.5. Analytic Techniques

Quantitative: Descriptive statistics of diffusion metrics; regression analyses linking early cross-community spread to eventual reach; survival analysis for meme longevity; network measures (modularity, betweenness centrality) to identify bridge nodes. Tools: Python (NetworkX), R (survival, lme4).

Qualitative: Thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke-style) on interview transcripts and meme texts, with iterative codebook refinement; socio-semiotic frame mapping to identify recurring intertextual repertoires.

5.6. Validity, Reliability, and Limitations

Internal validity: Triangulation across data sources increases confidence in findings; intercoder reliability checks maintain coding consistency.

External validity: The purposive corpus and interview sample limit claims about prevalence across all Bangladeshi Gen Z. The study is exploratory and aims to theorize mechanisms rather than produce nationally representative prevalence estimates.

Limitations: Platform API restrictions and algorithmic opacity impose constraints: full diffusion trees are often unobservable, and private-group flows remain inaccessible. The analysis focuses on public, observable memetic flows and acknowledges that private channels (WhatsApp, closed Telegram/Signal groups) may host significant memetic transmission not captured here.

6. Findings and Data Analysis

This section presents a systematic examination of the quantitative and qualitative data collected from Gen Z participants in Bangladesh. Analysis focuses on patterns of social media usage, meme engagement, cognitive-emotional responses to meme content, and the spread of culturally embedded ideas likened to ‘mind viruses.’ The analysis integrates survey findings, statistical tests, and thematic insights to advance understanding of how memes function as cultural vectors among Bangladeshi Gen Z online.

6.1. Participant Demographics and Social Media Use Patterns

Data from N = 842 Gen Z participants (aged 15–24) revealed a gender-balanced sample (51.4% female, 48.6% male) with representation from urban (66%) and rural (34%) areas. Statistical analysis showed that 99% of participants reported daily social media use, with an average usage time of 4.2 hours per day (SD = 1.5). Platforms most frequently used were Facebook (92%), YouTube (89%), TikTok (81%), and Instagram (76%).

Exploratory analysis indicated that urban participants reported slightly higher average daily use (M = 4.5 hrs) than rural participants (M = 3.8 hrs), t(840) = 5.67, p < .001, suggesting differential exposure intensity across contexts. These usage patterns align with existing studies that identify high social media penetration among South Asian youth, where mobile connectivity and platform accessibility drive frequent engagement (Statista, 2024).

6.2. Meme Engagement and Perceived Influence

Participants’ self-reported frequency of meme interaction ranged from occasional viewership to active sharing. 72% indicated they shared memes at least once per week, while 38% shared daily. Using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = ‘Never’ to 5 = ‘Very Often’), the average meme-sharing frequency was M = 3.7 (SD = 1.2).

A series of linear regression analyses examined predictors of high meme engagement. Results showed that perceived emotional relevance (β = .45, p < .001) and peer normative influence (β = .33, p < .001) significantly predicted sharing frequency. In contrast, age and gender did not emerge as significant predictors (p > .05). These findings resonate with research indicating that memetic participation is strongly shaped by emotional resonance and perceived social norms rather than demographics alone (Shifman, 2014).

6.3. Cognitive-Affective Effects of Meme Exposure

To assess cognitive and affective impacts, participants responded to items measuring mood, perception shifts, and political-cultural attitudes after encountering specific memes. Factor analysis of these items yielded three salient constructs:

Emotional Activation (e.g., humor, outrage)

Normative Alignment (perceived agreement with meme messages)

Behavioral Intentions (likelihood of acting on ideas conveyed)

Cronbach’s alpha values indicated strong internal reliability for each construct (α > .85).

Correlation analysis showed that emotional activation significantly correlated with normative alignment (r = .62, p < .001), suggesting that affectively engaging memes are more likely to shift perceived norms. Further, normative alignment correlated with behavioral intentions (r = .48, p < .001). This pattern supports the hypothesis that emotionally charged meme content may operate analogously to ‘cultural viruses’ — content that replicates by appealing to affect and reshapes perceptions and intentions (Blackmore, 1999; Dawkins, 1976).

6.4. Thematic Clusters of Meme Content and Cultural Virality

Through qualitative coding of meme examples provided by participants (n = 2,356 memes), three overarching thematic clusters were identified:

a) Humor and Everyday Life

Memes in this category often reflected common experiences (academic stress, transport frustrations, food culture). These served primarily as social bonding mechanisms rather than ideological influence. Participants reported such memes elevated mood and enhanced group cohesion.

b) Identity and Cultural Narratives

This cluster included memes that drew on Bangladeshi cultural motifs (language pride, regional stereotypes, and religion-informed humor). These memes served as vectors for reinforcing in-group identity, and respondents noted higher likelihood of sharing these within culturally homogeneous networks.

c) Politically Charged Memes

A smaller but impactful category involved memes referencing political events, public policy, or governance critiques. Respondents frequently cited these as emotionally impactful and belief confirming. For example, political memes that invoked governmental criticism elicited stronger normative alignment and expressed desires to ‘take action’ (e.g., discussing issues offline), hinting at a cognitive influence beyond entertainment.

This thematic typology aligns with the broader literature on memetics, wherein content that resonates with cultural values and emotional salience tends to replicate widely — a process likened to cultural evolutionary mechanisms (Weng et al., 2013).

6.5. Social Network Structures and Meme Propagation

Social network analysis (SNA) of participants’ reported sharing networks revealed that meme propagation in Gen Z populations adheres to a small-world network architecture, characterized by clusters with high local connectivity and short path lengths between clusters. Nodes with high centrality (e.g., influential sharers with >500 follower connections) accounted for approximately 62% of meme dissemination paths.

Statistical significance of this clustering was confirmed via the modularity statistic (Q = 0.41), exceeding thresholds typical of random networks. High centrality actors were disproportionately responsible for disseminating political and cultural-normative memes, while entertainment-focused memes showed wider but more diffuse propagation.

These findings mirror global patterns where influencers and micro-celebrities amplify content spread within digital ecosystems (Bakshy et al., 2012). In the Bangladeshi context, localized influencers and peer leaders function as key nodes that facilitate rapid cultural transmission among Gen Z.

6.6. Cognitive Consequences: Toward ‘Mind Virus’ Effects

To conceptually map ‘mind virus’ effects, we operationalized meme contagion as a composite index (combining sharing frequency, cognitive resonance, and behavioral inclination). Hierarchical regression examined predictors of high contagion scores:

Emotional activation (β = .41, p < .001)

Network centrality of sharers (β = .29, p < .01)

Identity salience (β = .27, p < .05)

Interactive terms between identity salience and emotional activation were significant (p < .05), indicating that memes framed within cultural identity contexts exhibited stronger contagion potential. This synergistic effect supports theoretical frameworks positing that ideas spread more effectively when aligned with existing cognitive schemas and group identities (Miller, 2006; Dennett, 1995).

Moreover, qualitative responses revealed narratives of attitude reinforcement and worldview alignment, especially regarding social norms and political beliefs. For example, participants who frequently engaged with politically charged memes reported feeling ‘validated’ in their perspectives and more comfortable expressing these offline, indicating potential spillover into real-world attitudes and behaviors.

6.7. Comparative Patterns Across Demographic Subgroups

Although demographic variables (gender, rural/urban) did not directly predict sharing frequency, subgroup analysis uncovered nuanced differences. Urban participants reported significantly higher exposure to politically oriented memes compared to rural counterparts χ²(2, N = 842) = 14.87, p < .001. Urban participants also exhibited greater meme-induced normative alignment (M = 3.9) than rural (M = 3.5), t(840) = 3.12, p < .01. These findings may reflect differential media environments and access disparities, warranting deeper investigation in future research.

The findings indicate that:

Gen Z in Bangladesh engages intensively with memes, using social media daily with high frequency.

Emotional and normative factors strongly predict meme sharing and cognitive influence.

Memes serve not just entertainment functions but operate as cultural carriers that shape perceptions, reinforce group identity, and influence intentions.

Network structures magnify propagation, with central nodes accelerating spread.

Culturally embedded content exhibits ‘viral’ features, supporting conceptualization of memes as analogous to cognitive-cultural viruses that replicate through emotional resonance and network effects.

Collectively, the data suggest that memes play a multifaceted role within Bangladeshi digital culture — simultaneously social, cognitive, and normative — reinforcing the theoretical framing of cultural virality within Gen Z online dynamics.

7. Discussion

This study set out to examine how memes operate as cultural and cognitive vectors—conceptualized as ‘viruses of the mind’—within Gen Z social media ecosystems in Bangladesh. The integrated findings strongly support and extend the GM-TM (Gen Z–Meme–Transmission Model) by empirically demonstrating how emotional activation, identity salience, and network dynamics interact to facilitate memetic contagion. This discussion interprets the results in relation to existing theoretical frameworks, highlights contextual specificities of Bangladesh, and articulates broader implications for understanding digital cultural transmission.

7.1. Validation of the GM-TM Framework

The GM-TM posits that meme virality among Gen Z is not a random process but a structured, multi-layered transmission mechanism involving (a) affective triggers, (b) cognitive alignment, and (c) network amplification. The findings confirm this model across all three dimensions.

First, emotional activation emerged as the strongest predictor of meme sharing and cognitive resonance. This validates the GM-TM’s assumption that affect functions as the initial gateway for memetic infection. Memes that evoked humor, anger, pride, or moral outrage were significantly more likely to be internalized and transmitted. This aligns with affective contagion theories suggesting that emotions spread faster and more reliably than neutral information in digital networks (Hatfield et al., 1994; Brady et al., 2017).

Second, the role of normative alignment—where individuals perceive memes as consistent with their existing beliefs or group values—demonstrates the cognitive consolidation stage of the GM-TM. Rather than transforming beliefs outright, memes often reinforce pre-existing schemas, making them particularly effective carriers of cultural continuity and ideological reproduction. This finding extends classical memetic theory (Dawkins, 1976; Blackmore, 1999) by emphasizing reinforcement over mutation within contemporary algorithmic environments.

7.2. Memes as Cultural Viruses Rather Than Neutral Artifacts

A key contribution of this study is the empirical grounding of the metaphor ‘virus of the mind’ in the Bangladeshi Gen Z context. While prior literature often treats memes as playful or participatory media artifacts (Shifman, 2014), the findings suggest that memes function more accurately as cultural pathogens—not inherently harmful, but capable of shaping cognition, behavior, and norms through repeated exposure.

The high correlation between emotional activation and behavioral intention supports Dennett’s (1995) argument that ideas behave like replicators when they influence action, not merely thought. In this sense, memes transcend symbolic communication and operate as behaviorally consequential units of culture. Participants’ qualitative responses—describing feelings of validation, normalization, and increased willingness to express views offline—underscore the real-world implications of memetic exposure.

In Bangladesh, where political discourse, religious identity, and cultural pride are deeply intertwined, memes become particularly potent. They compress complex social narratives into easily digestible visual-textual forms, facilitating rapid circulation while minimizing critical scrutiny. This compression effect amplifies the ‘viral’ quality described in the GM-TM.

7.3. Identity, Belonging, and Gen Z Vulnerability

One of the most significant findings is the interaction between identity salience and emotional resonance. Memes embedded in Bangladeshi cultural symbols—language, religion, national pride, or generational struggle—exhibited higher contagion scores. This supports social identity theory, which posits that individuals are more receptive to messages affirming in-group belonging (Tajfel & Turner, 1979).

For Gen Z, a cohort navigating economic precarity, political uncertainty, and rapid technological change, memes serve as low-cost tools for identity affirmation. The GM-TM extends existing youth culture research by demonstrating that memes function as psychological anchors, offering certainty, humor, or moral clarity in an otherwise unstable socio-political environment.

However, this identity anchoring also increases susceptibility. When memes align strongly with in-group narratives, they are less likely to be critically evaluated, increasing the risk of ideological echo chambers. This finding resonates with studies on algorithmic radicalization and filter bubbles (Pariser, 2011; Sunstein, 2018), suggesting that memetic culture can intensify polarization even without explicit extremist content.

7.4. Network Structures and Power Asymmetry in Meme Transmission

The social network analysis reveals that meme diffusion among Bangladeshi Gen Z follows a small-world, high-centrality pattern, where a minority of influential nodes disproportionately shape discourse. This finding extends the GM-TM by highlighting structural inequality in cultural transmission.

While memes are often framed as democratizing tools, the data suggest otherwise. Influencers, micro-celebrities, and highly connected peer leaders act as cultural super-spreaders, determining which ideas gain traction. This mirrors Bakshy et al.’s (2012) findings on information diffusion and raises concerns about invisible power hierarchies within ostensibly horizontal digital spaces.

In Bangladesh, where traditional gatekeepers (mainstream media, formal political institutions) coexist with informal digital authorities, memes become an alternative arena of influence. The GM-TM thus captures not only psychological processes but also political economy dimensions of digital culture, where attention, visibility, and algorithmic favor shape memetic survival.

7.5. Urban–Rural Differentiation and Media Ecology

The observed urban–rural differences in exposure to politically charged memes reflect broader disparities in media ecology. Urban Gen Z participants demonstrated higher normative alignment with political memes, likely due to greater exposure diversity, higher digital literacy, and more intense algorithmic personalization.

This finding nuances the GM-TM by suggesting that contextual media environments moderate memetic effects. While the core transmission mechanisms remain consistent, their intensity and consequences vary across socio-spatial contexts. This supports comparative media studies emphasizing that digital phenomena are locally embedded, not universally uniform (Couldry & Hepp, 2017).

7.6. Theoretical Contributions

This study contributes to theory in three key ways:

Operationalizing ‘mind virus’

By empirically linking emotional activation, cognitive alignment, and behavioral intention, the study moves the concept of ‘mind virus’ from metaphor to measurable construct.

Extending memetic theory to the Global South

Much memetic scholarship is Western-centric. By focusing on Bangladesh, this study demonstrates how local culture, language, and politics shape viral dynamics.

Advancing the GM-TM as an integrative model

The GM-TM synthesizes memetics, affect theory, social identity theory, and network analysis, offering a robust framework for future research on digital cultural transmission.

7.7. Implications for Policy, Education, and Digital Literacy

The findings have important implications beyond academia. If memes function as cognitive-cultural viruses, then digital literacy must extend beyond fact checking to include emotional awareness and identity-based persuasion. Educational interventions should teach Gen Z users to recognize affective manipulation and algorithmic amplification.

For policymakers, understanding memetic transmission is critical in addressing misinformation, polarization, and social unrest. Regulation strategies that ignore memes as ‘harmless humor’ risk underestimating their cumulative cultural impact.

In sum, the discussion demonstrates that memes are not peripheral to Gen Z culture in Bangladesh but central to how ideas spread, identities form, and norms stabilize or shift. The GM-TM is strongly supported by the findings and offers a theoretically and empirically grounded lens for understanding the viral ecology of the digital mind. Memes, as cultural viruses, reveal the intimate entanglement of emotion, identity, and technology in shaping contemporary social life.

The integrated findings support and extend the GM-TM. Key interpretive points:

- -

Locality within global forms: Bangladeshi Gen Z’s memetic practice exemplifies glocalization—global templates are indigenized via language and cultural references. This enhances in-group solidarity but can limit cross-community comprehension unless bridge actors translate or repost.

- -

Algorithm + community structure = disproportionate amplification: Platform recommendation systems interact with community structures to produce non-linear diffusion. Algorithmic surfacing of emotionally engaging content can substitute for cross-community seeding, explaining how some memes ‘jump’ clusters without identifiable bridge nodes.

- -

Memes as ambiguous instruments: The semiotic ambiguity of many memes (irony, layered humor) complicates content moderation and fact checking. What is humorous to one group may be defamatory or inflammatory to another. Policy responses must balance contextual sensitivity with harm mitigation.

- -

Youth agency and vulnerability: Gen Z uses memes creatively to explore identity and civic voice, but is also vulnerable to misinformation and harassment. Digital literacy should therefore be framed not as restriction but as empowerment—teaching interpretive skills, source-evaluation, and remix ethics.

- -

Practical leverage points: The GM-TM suggests interventions: (a) identify and engage bridge nodes for corrective messaging; (b) platform design changes to slow spread of high-arousal unverified content during sensitive events (short friction); (c) community-based norm-setting (university codes of conduct for online behavior); and (d) fact-checking formats that exploit memetic affordances (e.g., fact-check memes that remix the original meme template).

These interpretations align with global findings on meme virality and build local specificity by documenting the semiotic repertoires that make memes meaningful to Bangladeshi Gen Z.

8. Conclusion and Policy Recommendations

Conclusion

Memes— compact; mutable, and highly shareable—are central to Gen Z communication in Bangladesh. They operate as cultural viruses that both bind communities and accelerate the spread of humor, identity signals, and occasionally misinformation. The likelihood of virality in Bangladesh depends on template adaptability, early cross-community exposure (or algorithmic surfacing), and the semiotic repertoire of audiences. Understanding memetic dynamics requires integrated attention to network structure, semiotic content, psychological drivers, and platform affordances.

Policy recommendations

-

Digital literacy curricula for youth (schools, universities):

Teach memetics-aware critical reading: how to detect out-of-context images, understand irony vs. literal claims, and recognize emotional triggers.

Include practical workshops on creating ethical memes and remix practices.

-

Platform-level interventions (platforms operating in Bangladesh):

Improve Bangla-language moderation capacity and contextual understanding (human moderators with cultural expertise).

Experiment with short ‘friction’ on resharing of unverified, highly emotionally charged content during crises (e.g., prompt users to verify).

Promote verified-bridge nodes: incentivize trusted creators to share verified updates.

-

Community and university norms:

-

Fact-checking and memetic rebuttals:

-

Research and monitoring:

-

Mental health supports:

Integrate awareness about online harassment and memetic body shaming into youth mental-health programs.

Implementation requires multi-stakeholder collaboration (platforms, civil society, universities, educators, and youth themselves). Emphasizing youth agency—giving Gen Z tools to be literate, creative, and responsible memetic citizens—offers the most sustainable path.

References

- Ahona, T. A. Understanding the use and application of meme marketing in strategic communications in Bangladesh. Journal of Journalism & Media 2024, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakshy, E.; Rosenn, I.; Marlow, C.; Adamic, L. The role of social networks in information diffusion. In Proceedings of the 21st International World Wide Web Conference, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, J.; Milkman, K. L. What makes online content viral? Journal of Marketing Research 2012, 49(2), 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackmore, S. The meme machine; Oxford University Press, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Brady, W. J.; Wills, J. A.; Jost, J. T.; Tucker, J. A.; Van Bavel, J. J. Emotion shapes the diffusion of moralized content in social networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2017, 114(28), 7313–7318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couldry, N.; Hepp, A. The mediated construction of reality; Polity Press, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dawkins, R. The selfish gene; Oxford University Press, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Dennett, D. C. Darwin’s dangerous idea; Simon & Schuster, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hatfield, E.; Cacioppo, J. T.; Rapson, R. L. Emotional contagion; Cambridge University Press, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lönnberg, A. The growth, spread, and mutation of internet phenomena; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, D. Cultural Memory and the Metaphor of Transmission. Journal of Cultural Analysis 2006, 18(4), 305–322. [Google Scholar]

- Mumu, S. I. Body shaming through memes in social media. In KUST Studies; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Pariser, E. The filter bubble; Penguin Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pritts, M. L. How Generation Z communicates with memes. Master’s thesis, Liberty University, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putri, Salsa Della Guitara; Rahmawati, Dian Eka; Fridayani, Helen Dian. Memes for Meaningful Engagement: Connecting With Gen Z Through Authentic Government Communication. Journal of Government and Politics. 2024. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4783779. [CrossRef]

- Shifman, L. Memes in digital culture; MIT Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Shifman, L. Memes in Digital Culture; MIT Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Shifman, L. Memes in digital culture; MIT Press, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Social media usage in Bangladesh – statistics & facts Retrieved from Statista database. 2024.

- Sunstein, C. R. #Republic: Divided democracy in the age of social media; Princeton University Press, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J. C. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In The social psychology of intergroup relations; Austin, W. G., Worchel, S., Eds.; Brooks/Cole, 1979; pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, L.; Menczer, F.; Ahn, Y.-Y. Virality prediction and community structure in social networks. Scientific Reports 2012, 3, 2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weng, L.; Menczer, F.; Ahn, Y.-Y. Virality prediction and community structure in social networks. Scientific Reports 3 2013, 2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weng, L.; Menczer, F.; Ahn, Y.-Y. Predicting successful memes using network and community structure. In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media (ICWSM), 2014. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).