1. Introduction

1.1. Contextualizing Social Media's Role in Civic Unrest

In the digital age, social media has revolutionized the modalities of political discourse, civic participation, and mass mobilization. Platforms such as Facebook, YouTube, WhatsApp, Telegram, TikTok, and X (formerly Twitter) have evolved beyond their origins as tools for social interaction into highly influential arenas for political engagement, protest coordination, and information dissemination. This transformation is particularly pronounced in the Global South, where these platforms serve as both instruments of empowerment and arenas of contestation. In Bangladesh, as in many other developing democracies, social media has emerged as a crucial outlet for marginalized voices and dissenting narratives. Yet, this digital democratization is increasingly entangled with a more sinister dimension: the systematic use of these platforms for orchestrating surveillance, fostering ideological radicalization, and catalyzing collective violence through misinformation and algorithmically driven content amplification.

In the context of Bangladesh, the proliferation of digital communication technologies has intersected with a volatile political environment, growing socio-economic discontent, and fragile democratic institutions. Social media, in this scenario, operates as a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it has empowered civil society actors and enabled digital activism, especially among the youth; on the other, it has become a vector for algorithmically amplified hate speech, coordinated mob violence, and extra-judicial trials conducted in virtual spaces and executed in real life. The events surrounding the 5 August 2024 unrest in Bangladesh underscore this paradox in stark terms.

1.2. Rise of Algorithmically Driven Radicalization

Algorithmic radicalization refers to the process through which individuals are exposed to increasingly extreme and often violent content due to the design and functioning of recommendation systems used by digital platforms. These algorithms prioritize content that is engaging, emotionally provocative, and shareable, often leading users down so-called ‘rabbit holes’ of conspiracy theories, religious extremism, political disinformation, and calls to action. In South Asia, including Bangladesh, this phenomenon has been exacerbated by high digital penetration, low digital literacy, and a lack of effective regulation and platform accountability.

In the months preceding the 5 August 2024 unrest, analysis of digital footprints indicates a marked increase in algorithmic amplification of content that framed political dissenters, religious minorities, and student activists as enemies of the state or traitors to national identity. Closed messaging apps such as Telegram and WhatsApp became breeding grounds for secretive radical discourse, while mainstream platforms like Facebook and YouTube played host to live videos, hashtags, and incendiary rhetoric that reached millions within minutes. The blurred boundary between online outrage and offline violence became especially dangerous when algorithmically popular content incited spontaneous mob trials and attacks, bypassing legal and institutional channels entirely.

1.3. Historical Build-Up to 5 August 2024

The 5 August 2024 unrest did not occur in a vacuum. It was the culmination of a long-standing build-up of political tensions, digital misinformation, socio-economic inequality, and a systematic erosion of institutional checks and balances. The months leading to August 2024 were marked by significant political instability, with multiple allegations of corruption, repression of opposition voices, and increasing censorship.

In June 2024, the leak of a confidential government document suggesting plans to surveil university students through their digital activities triggered nationwide concern. Hashtags such as #DigitalRebellion, #FreeCampusVoices, and #JusticeForYouth gained traction, especially among students and young professionals. Influential digital personalities, bloggers, and activists began disseminating content that criticized the state's surveillance apparatus, often referencing leaked chat transcripts, policy documents, and anonymous testimonies.

By mid-July, this digital mobilization took a darker turn. Disinformation campaigns—originating from both domestic and cross-border sources—began to flood the platforms, accusing particular youth leaders of sedition, foreign allegiance, or religious blasphemy. A viral video from Sylhet, purportedly showing a student insulting religious texts, was later revealed to be manipulated—but not before it incited a mob attack on the student’s residence. As similar incidents multiplied across the country, the digital sphere became saturated with hate speech, vigilante justice narratives, and crowdsourced calls to action.

The tipping point came on 5 August, when coordinated violence erupted in Dhaka, Chittagong, Sylhet, and several other cities. Groups mobilized through WhatsApp and Telegram launched physical attacks on individuals accused in viral posts. In many cases, live streams of these mob trials were broadcast via Facebook and TikTok, drawing thousands of viewers in real-time and glorifying extrajudicial punishments. New York, Sep 27, 2024 at Clinton Foundation, Muhammad Yunus introduced a gang of young people to American audience here (Bangladesh) the power behind the ‘meticulously designed’ protests that led to the ouster of Sheikh Hasina from power. Yunus told that it was a meticulously designed thing. It just did not suddenly come. Very well designed. Even the leadership did not know (him) so they could not catch him,’ Yunus told about the protests in Bangladesh that left more than 3200 persons killed by his militant groups (UN Report, 2025 Bangladesh). These events demonstrated a chilling convergence of digital radicalization and real-world consequences, highlighting a dangerous new paradigm in Bangladesh’s political and social landscape.

1.4. Relevance and Originality of the Study

This research addresses a critical gap in contemporary scholarship on digital media and political violence by offering an in-depth, empirically grounded, and theoretically informed study of the 5 August 2024 unrest in Bangladesh. While previous studies have explored social media’s role in elections, protest movements, and disinformation campaigns globally, few have examined how platform algorithms, user-generated content, and political manipulation intersect to produce violent collective action in the Global South.

The originality of this study lies in its interdisciplinary approach, combining digital ethnography, computational data analysis, in-depth interviews, and case studies to trace the lifecycle of digital radicalization and mob violence. It situates Bangladesh within a broader global discourse on algorithmic politics and platform accountability while emphasizing the local sociopolitical and cultural conditions that make this convergence especially volatile.

Moreover, this study contributes to a growing body of work on digital authoritarianism and resistance, offering policy-relevant insights into platform governance, civic education, digital rights, and content moderation in contexts where the line between dissent and violence is becoming increasingly blurred. In doing so, it seeks not only to understand what happened on and around 5 August 2024 but also to inform preventive strategies and democratic safeguards in the digital age.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Introduction: Situating the Study in Existing Scholarship

The intersection of social media, civic unrest, and algorithmic politics has received growing scholarly attention over the past decade. However, the specific pathways through which digital technologies, platform architectures, and socio-political dynamics converge to incite violence remain underexplored, particularly in Global South contexts. This literature review synthesizes theoretical and empirical contributions across four major thematic domains: (1) the role of social media in mobilization and unrest; (2) algorithmic radicalization and echo chambers; (3) misinformation, disinformation, and digital vigilantism; and (4) Bangladesh-specific studies on digital politics and mob violence. Each domain helps locate this study’s originality in addressing the 5 August 2024 unrest as an emergent phenomenon of socio-digital convergence.

2.2. Social Media and Civic Unrest: Global and Regional Perspectives

The relationship between social media and civic unrest has been extensively explored in studies following the Arab Spring, Occupy Wall Street, and the 2019 Hong Kong protests. Castells (2012) identified digital networks as ‘spaces of autonomy,’ allowing grassroots actors to bypass traditional gatekeepers of power. Similarly, Tufekci (2017) argued that social media platforms afford ‘affective publics’ that can organize large-scale protests but are structurally weak against state repression due to a lack of formal organization.

In the South Asian context, social media platforms have become critical tools in political expression and protest (Udupa & Dattatreyan, 2020). In India, studies have shown how Twitter and WhatsApp groups are used to coordinate both peaceful resistance and violent campaigns (Belli, 2022; Arora, 2019). Similar dynamics are emerging in Pakistan and Sri Lanka, where Facebook-fueled narratives have led to anti-minority violence (Gunawardena, 2021; Shah & Siddiqui, 2020). However, in Bangladesh, the interplay of state surveillance, religious nationalism, and youth activism makes the socio-digital ecosystem uniquely volatile (Sultana, 2021; Kabir, 2022).

2.3. Algorithmic Radicalization and Digital Pathways to Extremism

The role of recommendation algorithms in promoting radical content has garnered significant academic attention in recent years. Algorithms on platforms like YouTube, Facebook, and TikTok are designed to optimize engagement by serving content that is likely to provoke emotional reactions—often leading to the amplification of extremist or conspiratorial narratives (Tufekci, 2015; Ribeiro et al., 2020). This process is referred to as ‘algorithmic radicalization,’ wherein users are gradually exposed to increasingly extreme views due to algorithmic feedback loops.

Zuckerman and Rushkoff (2019) argue that platforms’ algorithmic architectures inadvertently ‘gamify’ radical engagement, especially among youth. In low-regulation settings such as South Asia, the dangers are amplified by limited media literacy and infrastructural gaps in moderation (Gillespie, 2018). In Bangladesh, Rahman and Khatun (2023) observed that Facebook’s Bengali-language moderation remains under-resourced, leading to the unchecked spread of hate speech and religious incitement.

Studies by Mozur et al. (2021) demonstrate how algorithmic design disproportionately affects societies with fragile democratic institutions. Content moderation is often reactive rather than preventive, failing to stop virality once disinformation is seeded. This study contributes to this literature by showing how algorithmic radicalization in Bangladesh was not only technologically driven but also socially mediated through localized narratives of religious identity, nationalism, and anti-intellectualism.

2.4. Disinformation, Rumors, and Digital Vigilantism

The weaponization of misinformation and disinformation in digital spaces has become a central concern in media and communication studies. Wardle and Derakhshan (2017) distinguish misinformation (false but not intentionally misleading content), disinformation (deliberately false content), and malinformation (true information used maliciously) as distinct but overlapping categories contributing to what is now termed the ‘information disorder.’

In Bangladesh, rumors and fake news spread rapidly through closed messaging apps like WhatsApp and Telegram, often leading to spontaneous acts of violence (Islam & Hossain, 2021). The 2018 rumor of child kidnappers, which resulted in mob lynchings, demonstrated how quickly misinformation can catalyze real-world harm (Kamal, 2019). Recent literature on ‘digital vigilantism’ explores how social media users take justice into their own hands, often encouraged by viral accusations and moral panics (Trottier, 2017; Udupa, 2022).

Empirical studies show that disinformation in Bangladesh often leverages religious rhetoric and anti-secular sentiment. For instance, Mahmud (2023) highlights how viral posts accusing individuals of religious blasphemy lead to extrajudicial punishments. This paper adds to that body of work by demonstrating how such narratives were not only grassroots-generated but often platform-boosted, algorithmically amplified, and indirectly sanctioned by state actors who failed to intervene.

2.5. The Politics of Platform Governance and Surveillance

Critical scholarship on digital authoritarianism has emphasized the state’s use of digital platforms for both surveillance and suppression (Deibert, 2020; Feldstein, 2021). In Bangladesh, the Digital Security Act (2018) has been widely criticized for enabling the arbitrary arrest of online dissidents, journalists, and student activists (Human Rights Watch, 2021). Studies by Haque and Sarker (2022) document how government-linked actors actively manipulate digital discourse through bot networks and astroturfing campaigns.

However, the dual-use nature of digital platforms means that they are both instruments of resistance and control. Research on the ‘platform governance gap’ (Gorwa, 2019) underscores the asymmetry between corporate interests and public accountability, especially in non-Western contexts. In Bangladesh, activists have accused Meta and Google of ignoring content moderation requests in Bengali, citing lack of resources and political complexity (Transparency International Bangladesh, 2023).

This study builds on these insights by showing how the regulatory vacuum and opaque platform governance mechanisms created an environment in which misinformation thrived and mobs acted with impunity. The events surrounding 5 August 2024 provide a case study of how this governance failure plays out in crisis.

2.6. Youth, Identity, and Digital Culture in Bangladesh

The sociology of youth in Bangladesh is undergoing a digital transformation. Scholars like Maniruzzaman (2020, Azad (2022) note that the smartphone revolution has created a hyperconnected generation that is both politically aware and algorithmically vulnerable. Platforms like TikTok and Facebook serve as spaces of identity construction, peer bonding, and ideological expression.

Youth radicalization, both secular and religious, is increasingly mediated through digital subcultures. Haider and Akram (2023) argue that digital aesthetics—such as memes, short videos, and symbolic hashtags—play a crucial role in shaping political identity. In the case of the 5 August 2024 unrest, digital artifacts like viral videos, manipulated images, and live-streamed attacks became not just tools of communication but cultural products that codified and glorified violence.

This study contributes new empirical insights into how youth engagement on digital platforms oscillates between civic activism and vigilante justice. The study’s integration of digital ethnography and user interviews offers a grounded perspective on these affective publics.

2.7. Gaps in the Literature and Study Contributions

Despite the growing scholarship on digital violence, few studies have connected platform architectures, political climates, and cultural contexts in explaining collective digital radicalization. Even fewer have used a case-specific approach rooted in the Global South, especially Bangladesh. Moreover, much of the algorithmic bias literature focuses on the Global North and English-language contexts, ignoring linguistic, cultural, and geopolitical specificities (Noble, 2018).

This research contributes to closing these gaps by—

Providing a localized, postcolonial perspective on algorithmic violence.

Offering multi-method evidence—quantitative (algorithmic tracking, content mapping), qualitative (interviews, discourse analysis), and visual (network and heat maps).

Theorizing mob trials as a hybrid digital-physical phenomenon sustained by algorithmic amplification, user moral economies, and weak institutional safeguards.

The reviewed literature offers critical building blocks for understanding the role of social media in civic unrest and digital radicalization. However, existing work falls short in capturing the complexity of platform-enabled collective violence in Bangladesh. By addressing this lacuna, the current study offers an urgently needed scholarly intervention. It not only sheds light on the events of 5 August 2024 but also contributes to a broader theorization of how algorithmic cultures and political violence are interlinked in the Global South.

3. Theoretical Framework

3.1. Introduction: Theoretical Anchors for a Complex Crisis

The 5 August 2024 unrest in Bangladesh exemplifies the convergence of digital architectures, algorithmic amplification, and socio-political tensions. To dissect this phenomenon, we draw upon interdisciplinary theories encompassing social movement dynamics, algorithmic radicalization, digital vigilantism, and moral psychology. This framework facilitates an understanding of how digital platforms not only reflect but also actively shape collective behaviors and societal outcomes.

3.2. Social Movement Theories: Mobilization in the Digital Age

Traditional social movement theories, such as Resource Mobilization Theory and Political Process Theory, have long examined the conditions under which collective action emerges. However, the digital era necessitates a reevaluation of these frameworks. Bimber's (1998) concept of ‘accelerated pluralism’ posits that the internet expedites the formation and action of issue-specific groups, often bypassing traditional institutional structures. This rapid mobilization is evident in Bangladesh, where online platforms have facilitated swift organization around contentious issues.

Moreover, the framing processes within social movements have evolved. Benford and Snow (2000) emphasize the importance of diagnostic, prognostic, and motivational framing in mobilizing participants. In the context of Bangladesh, digital narratives have been instrumental in constructing grievances and rallying support, often through emotionally charged content that resonates with specific moral and cultural values.

3.3. Algorithmic Radicalization: The Role of Platform Architectures

Algorithmic radicalization refers to the process by which recommendation algorithms on social media platforms expose users to increasingly extreme content, potentially fostering radical beliefs and behaviors (Ribeiro et al., 2020). These algorithms prioritize engagement, often amplifying sensationalist and divisive content. In Bangladesh, the lack of robust content moderation in local languages exacerbates this issue, allowing harmful narratives to proliferate unchecked (Rahman & Khatun, 2023). The phenomenon is further complicated by the presence of social bots, which can manipulate online discourse by disseminating inflammatory content and targeting influential users (Stella et al., 2018). Such dynamics contribute to the formation of echo chambers, reinforcing existing beliefs and increasing polarization, (Stella et al.,2018).

3.4. Digital Vigilantism and Moral Economies

Digital vigilantism involves individuals or groups taking justice into their own hands through online platforms, often leading to real-world consequences (Trottier, 2017). In Bangladesh, instances of mob justice have been linked to viral social media posts accusing individuals of blasphemy or other transgressions (Mahmud, 2023). These actions are frequently justified through moral economies that prioritize communal values over legal processes.

Moral Foundations Theory (Haidt, 2012) provides a lens to understand these behaviors, suggesting that moral judgments are based on innate psychological systems. In collectivist societies like Bangladesh, foundations such as loyalty, authority, and purity may be particularly salient, influencing the propensity for digital vigilantism, (Stella at al., 2018).

3.5. The Bangladesh Context: Socio-Political and Technological Factors

Bangladesh's socio-political landscape, characterized by religious conservatism and political polarization, creates a fertile ground for digital radicalization. The government's use of the Digital Security Act to suppress dissent has further complicated the online environment, leading to self-censorship and the migration of discourse to less regulated platforms (Haque & Sarker, 2022).

Additionally, the rapid increase in internet penetration and smartphone usage has outpaced digital literacy initiatives, leaving many users vulnerable to misinformation and manipulation (Sultana, 2021). The convergence of these factors underscores the need for a nuanced theoretical framework that accounts for both global digital dynamics and local socio-cultural contexts.

The intersection of social movement theories, algorithmic radicalization, digital vigilantism, and moral psychology offers a comprehensive framework to analyze the 5 August 2024 unrest in Bangladesh. By considering the unique socio-political and technological landscape of the country, this study aims to contribute to a deeper understanding of how digital platforms can both empower and endanger societies.

3.6. Theoretical Framework and Case Study Exploration

This research is anchored in an interdisciplinary matrix of theories, including:

- a)

-

Algorithmic Radicalization and Platform Governance

(Tufekci, 2018; Gillespie, 2010; O’Neil, 2016)

- b)

-

Digital Public Sphere and Counter-publics

(Fraser, 1990; Papacharissi, 2002)

- c)

-

Mob Justice and Digital Vigilantism

(Trottier, 2017; Monahan, 2016)

- d)

-

Information Disorder (Fake News, Disinformation, and Conspiracy Theories)

(Wardle & Derakhshan, 2017; Tandoc, Lim, & Ling, 2018)

- e)

-

Networked Authoritarianism and Platform Manipulation

(Howard & Bradshaw, 2019; Morozov, 2011)

3.7. Case Study 1: The Sylhet Mob Incident and the ‘Blasphemy’ Video Context & Timeline:

On 21 July 2024, a highly manipulated video began circulating on Facebook and Telegram allegedly showing a student of Shahjalal University of Science and Technology (SUST) defaming Islamic texts. The video, which was spliced and edited with synthetic audio overlays, sparked outrage in conservative online groups.

Telegram and Facebook played pivotal roles in virality. The video was first dropped in a closed Telegram group titled ‘Islamic Justice League BD,’ with over 25,000 members. Within hours, 83 copies of the video were uploaded to Facebook with hashtags such as #BlasphemyJustice, #PunishNow, and #NoForgiveness. YouTube creators added fuel with ‘reaction’ videos.

Offline violence erupted on 23 July when approximately 300 people attacked the student’s house in Sylhet. Live footage was streamed via TikTok and Facebook Live. A chilling comment read: ‘We saw the video—justice delivered. Allahu Akbar.’

Using CrowdTangle and Netviz data, we traced how content reached over 2.1 million users within 36 hours. Facebook’s recommender system linked this content to other popular religious pages, effectively ‘mainstreaming’ it.

This case illustrates digital vigilantism (Trottier, 2017) where misinformation, amplified by algorithms, mobilized physical violence. The moral panic was algorithmically shaped and socially executed.

3.8. Case Study 2: The Chittagong Trial Stream and Instant ‘Justice’

On 3 August 2024, a viral Facebook post claimed that a garment worker in Chittagong had insulted the Prime Minister. The post originated from a page titled ‘True Bangladeshi Patriots’ and amassed 76,000 shares in two days.

On 5 August, a mob stormed the worker’s neighborhood. He was dragged to a public space, interrogated, and beaten—live-streamed on Facebook and viewed by over 450,000 people. Commenters debated his fate in real time: ‘Hang him or forgive him?’

Despite Facebook’s community standards, the stream remained active for 53 minutes before takedown. Live commentary and emoji reactions escalated the fervor, gamifying the violence.

Using Goffman’s dramaturgical model and Papacharissi’s (2015) theory of affective publics, the event becomes legible as a violent theater of identity and nationalism.

‘People weren’t just viewers. They were judges, juries, and executioners—armed with likes and angry reacts.’ — Digital Rights Advocate, Dhaka

3.9. Case Study 3: Telegram’s Shadow Groups and Youth Radicalization

Telegram channels such as ‘New Mujahid Youth’ and ‘Ummah Justice Command’ became central to digital radicalization. Unlike open platforms, these encrypted networks incubated more structured calls to violence.

Analyzing over 15 channels (via anonymous participant observation), researchers noted ritualistic content including daily pledges, digital martyrdom glorification, and enemy lists. Chatbots were deployed to assign targets and circulate real-time updates.

‘Telegram felt like an underground madrasa. There were sermons, and there were missions. It didn’t feel like social media—it felt like command central.’ — Former group member (interviewed under anonymity)

This aligns with Zeynep Tufekci’s (2018) idea of ‘insular amplification’ and Morozov’s (2011) warnings about cyber-utopianism. Telegram acted not only as a communication tool but as a recruitment machine.

3.10. Comparative Table of Digital-to-Physical Incidents

| Incident |

Platform(s) |

Trigger Content |

Offline Consequence |

Estimated Reach |

| Sylhet Blasphemy Video |

Telegram, Facebook, YouTube |

Edited video clip |

Mob attack on home |

2.1 million |

| Chittagong Garment Worker |

Facebook, TikTok |

Alleged defamation |

Public beating |

450,000+ viewers |

| Youth Radicalization Cells |

Telegram (closed groups) |

Religious propaganda |

Coordinated action plans |

15+ shadow groups |

3.11. Synthesis: From Content to Carnage

The synthesis of these cases illustrates that digital platforms—especially those with closed-loop or recommendation engines—serve not merely as neutral conduits but as amplifiers of affective incitement and structural bias. Theoretical integration reveals:

- -

Platform capitalism thrives on engagement, even if it’s violent (Zuboff, 2019).

- -

Affective publics are hyper-mobilized by injustice frames and grievance narratives (Papacharissi, 2015).

- -

Digital mob trials are modern incarnations of extra-legal justice, shaped by visibility and virality (Trottier, 2017).

3.12. Policy Implications and Ethical Reflections

- -

Regulatory Gaps: Current content moderation protocols are inadequate. Even when takedowns occur, they are often too late.

- -

Digital Literacy: There is a need for structural investment in digital education and civic reasoning, especially targeting youth.

- -

Platform Responsibility: Platforms must be held accountable for the design of their algorithmic systems—not just content policies.

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Introduction to Methodology

This section outlines the methodological framework employed to examine the intersection of social media dynamics, algorithmic radicalization, and mob violence in the context of the political and social crisis that erupted in Bangladesh around 5 August 2024. Given the interdisciplinary nature of the study, which cuts across media studies, political sociology, and digital anthropology, a mixed-methods research design was adopted. Central to this approach was a multi-case study method focusing on critical events, disinformation episodes, and algorithmic trends that led to and followed the August 2024 unrest.

The methodology integrates both qualitative and quantitative techniques, including digital ethnography, content analysis, semi-structured interviews, algorithmic data tracing, and field-based case studies from four districts—Cumilla, Narayanganj, Rajshahi, and Sylhet. These districts were selected based on the intensity of unrest, digital traceability of disinformation, and availability of on-ground data.

4.2. Research Design

The study adopts a qualitative-dominant mixed-methods approach with embedded case studies. According to Creswell and Plano Clark (2017), mixed-methods research allows for the triangulation of data, improving validity and enabling a holistic understanding of social phenomena. Qualitative data were used to capture the sociocultural and emotional narratives underpinning digital mobilization, while quantitative data—such as social media reaction metrics and disinformation spread patterns—provided a broader structural context.

4.3. Research Questions

The study is driven by the following primary and secondary research questions:

Primary Research Question:

Secondary Research Questions:

What were the algorithmic and emotional patterns underlying viral disinformation leading to violence?

Which platforms (Facebook, WhatsApp, Telegram, etc.) played the most significant roles in triggering collective action?

How were digital narratives converted into physical violence and state response?

What counter-narratives and regulatory discourses emerged post-crisis?

4.4. Case Study Method

Case studies are essential for unpacking complex socio-political phenomena rooted in specific contexts (Yin, 2014). For this research, four embedded case studies were developed to understand how algorithmically driven social media behaviors catalyzed collective violence and mob trials.

Case Study Selection Criteria:

Evidence of online-to-offline radicalization;

Geolocation-linked digital artifacts (posts, messages, screenshots);

Involvement of social media influencers or micro-celebrities;

Presence of affected victims, accused individuals, or families for interviews;

Variability in state response (arrests, internet shutdowns, etc.)

The four case studies are:

Case A (Cumilla): A disinformation video alleging blasphemy by a local professor;

Case B (Narayanganj): Coordinated Facebook and WhatsApp rumors of a youth-led bombing cell;

Case C (Rajshahi): Mobilization through religious Telegram groups;

Case D (Sylhet): Algorithmic escalation of hate speech through reaction-based Facebook posts.

4.5. Data Collection Methods

4.5.1. Digital Ethnography

Digital ethnography was conducted across Facebook, WhatsApp, and Telegram groups from June to September 2024. Approximately 15 high-traffic public Facebook pages and 30 WhatsApp/Telegram groups were monitored and archived using NCapture and WebRecorder tools (Murthy, 2012). These platforms were selected based on their high user engagement and correlation with reported incidents.

4.5.2. Content Analysis

A purposive sample of 2,000 social media posts—including text, memes, videos, and voice messages—was selected for content analysis. Each post was coded thematically based on:

- a)

Emotion (anger, fear, sadness, pride);

- b)

Religious symbolism;

- c)

Calls to action;

- d)

Mentions of ‘atheism,’ ‘Islam insult,’ ‘divine punishment,’ etc.;

- e)

Shareability indicators (likes, shares, comments, reaction type).

NVivo 14 was used to code data inductively and deductively based on pre-determined frames such as disinformation, religious mobilization, algorithmic amplification, and mob rhetoric (Krippendorff, 2018).

4.5.3. Interviews and Oral Histories

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with:

12 victims/survivors of mob trials;

8 accused persons who were arrested and later released;

6 police officials and local administrators;

4 data scientists from local fact-checking organizations;

7 social media influencers and religious micro-celebrities;

5 Facebook community moderators.

All interviews were transcribed, coded, and anonymized. Ethical approval was obtained from the University Ethics Committee, and respondents signed informed consent forms.

4.5.4. Algorithmic Engagement Tracing

Using CrowdTangle, Facebook Graph API, and public Telegram analytics tools, posts and reactions from July–August 2024 were tracked. The goal was to assess:

- —

Frequency and temporal patterns of virality;

- —

Emotional reaction distribution (love, angry, sad, wow);

- —

Co-mention networks;

- —

Amplification loops caused by high-influence nodes.

This analysis revealed how Facebook’s engagement-based sorting pushed emotionally charged disinformation to the top, often amplifying harmful narratives (Tufekci, 2018; Gillespie, 2018).

4.6. Sampling Strategy

Purposive and snowball sampling strategies were adopted. The purposive sampling allowed targeting specific disinformation campaigns and actors, while snowball sampling enabled access to hard-to-reach respondents (e.g., victims, administrators of private Telegram groups). The study also employed maximum variation sampling to reflect differences across geography, religious rhetoric, and platform use.

Sample Summary

| Type |

Sample Size |

| Public Facebook Pages |

15 |

| WhatsApp/Telegram Groups |

30 |

| Social Media Posts/Artifacts |

2,000 |

| Interviews (Individuals) |

42 |

| Case Study Locations |

4 Divisions |

4.7. Data Analysis Techniques

Thematic analysis was used to categorize and analyze qualitative data following Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six-phase approach. Quantitative metrics from CrowdTangle and engagement analytics were examined using descriptive statistics, visualization, and temporal mapping (Kaplan & Haenlein, 2010).

Key analytic tools:

NVivo 14 for qualitative coding;

Excel and Tableau for data visualization;

Gephi for social media network analysis;

Python scripts for scraping open-source Telegram data.

4.8. Ethical Considerations

This research dealt with highly sensitive topics, including religious identity, political violence, and state surveillance. All respondents were anonymized, and interviews were encrypted and stored on secured drives. Social media content was anonymized when cited, especially when referring to victims or accused individuals.

Approval was granted by the (University of Rajshahi, Ethics Review Board IQAC). The research adheres to the principles of the Belmont Report (1979), particularly the principles of respect for persons, beneficence, and justice.

4.9. Limitations

- a)

Access to private encrypted groups (Telegram/WhatsApp) was limited;

- b)

Risk of misattributing offline events solely to online triggers;

- c)

Algorithmic opacity limited full traceability of content curation;

- d)

Interview data may be subject to recall bias and self-censorship;

- e)

Difficulty in isolating algorithmic effects from socio-political contexts.

4.10. Validity and Reliability

To ensure the validity of findings, triangulation was used across multiple data sources: digital artifacts, interviews, and engagement analytics. Member checks were conducted with 7 respondents to validate narrative accounts. An inter-coder reliability test on NVivo coding achieved a Cohen’s Kappa score of 0.81, indicating substantial agreement.

The methodological framework employed in this study blends digital ethnography, algorithmic data tracing, and context-sensitive case study analysis to critically engage with the Bangladesh 2024 unrest. This approach not only illuminates how algorithmic amplification and digital propaganda fueled real-world violence but also lays the foundation for assessing the democratic risks embedded in platform politics and data capitalism in the Global South.

Visual info-graphic on Research Design

5. Findings

5.1. Introduction

This section analyzes the data collected from user-generated content, platform-based metadata, interviews, and digital ethnography conducted between July and September 2024. It identifies key triggers of unrest and thematic patterns across Facebook, Telegram, and TikTok. We draw upon specific case studies from Dhaka, Sylhet, and Rajshahi to understand how narratives of mobilization and victimization were constructed and spread algorithmically, culminating in physical violence and mob trials. The findings illuminate how digitally constructed grievances rapidly escalated into offline vigilantism.

5.2. Triggers and Themes from User-Generated Content

5.2.1. Key Triggers:

Blasphemy Accusations: One of the most prominent triggers of unrest was the circulation of videos allegedly showing students disrespecting religious texts or symbols. These were later revealed to be manipulated or taken out of context.

Leaked Surveillance Policies: Allegations that the government planned to surveil university campuses via digital monitoring sparked widespread outrage, especially among student groups.

Allegations of Anti-State Activity: Hashtags such as #TraitorYouth and #CleanseTheCampus portrayed certain student leaders as foreign agents or enemies of Islam.

5.2.2. Common Themes Identified

Victimhood and Revenge Narratives: Many viral posts depicted ‘true patriots’ avenging the honor of religion or the nation. This dual identity of ‘digital martyr’ and ‘offline hero’ was instrumental in radical mobilization.

Hashtag Warfare: Hashtags like #JusticeForIman, #DigitalPurge, and #CrushTheTraitors served as rallying cries across Facebook and Telegram. Often created by influencer accounts, these hashtags trended for multiple days (Data collected from CrowdTangle, 2024).

Screenshots and Doxxing: Users shared screenshots of private chats, classroom conversations, and supposed proof of blasphemy, often accompanied by doxxing of individuals.

5.3. Role of Platforms: Facebook, Telegram, TikTok

5.3.1. Facebook

Facebook played a central role as the content aggregator and amplifier. Public pages and ‘patriot groups’ with hundreds of thousands of followers acted as hubs for anti-student and pro-mob narratives. Facebook Live was repeatedly used during the attacks to stream mob actions, reinforcing the legitimacy of these acts in real-time.

Over 36% of viral disinformation content was initially published on Facebook (Dhaka University Media Lab Report, 2024).

AI-generated memes, photoshopped documents, and altered videos were frequently posted and reshared without verification.

5.3.2. Telegram

Telegram acted as the backend coordination platform. Unlike Facebook, where content was public, Telegram groups provided semi-private spaces for planning attacks, circulating lists of ‘targeted individuals,’ and sharing real-time updates.

One Telegram group titled ‘Campus Cleansers 24’ had over 11,000 active members and was used to coordinate attacks in Dhaka and Sylhet.

Voice messages and pinned messages in groups revealed direct incitement and specific instructions for identifying and harming supposed ‘blasphemers.’

5.3.3. TikTok

TikTok became the visual weapon of emotional manipulation. Short videos with dramatic background music and edited clips from protests, cries of victims, and calls for vengeance went viral, especially among users under 25.

TikTok’s algorithmic structure promoted videos that had more engagement within the first 30 minutes, rapidly amplifying the most incendiary content (Zhang et al., 2023).

Many of these videos were fabricated using stock footage or staged reenactments.

5.4. Narratives of Mobilization and Victimization

5.4.1. Mobilization Narratives:

Heroic Mobilizers: Posts on Facebook and TikTok often portrayed mob actors as heroes defending national and religious values.

Digital Fatwas: In some Telegram groups, religious leaders issued informal digital ‘fatwas’ against specific students, which were then spread via screenshots across Facebook and WhatsApp.

5.4.2. Victimization Narratives:

Martyrs of the Movement: Videos of injured or arrested youth were re-shared with captions such as ‘Our Brothers in Chains’ or ‘Arrested for Telling the Truth,’ framing even those who were inciting violence as victims of state repression.

Silenced Voices: Accounts banned for spreading hate speech claimed suppression of truth and invoked anti-Western conspiracy theories.

5.5. Algorithmic Spread of Hate

5.5.1. Facebook Recommender Systems:

Facebook’s engagement-maximizing algorithm favored content that received higher emotional reactions—especially ‘Angry’ or ‘Sad’ reacts. Posts with such reactions were found to be 3.7 times more likely to be recommended to new users via the News Feed (Bakir & McStay, 2022).

5.5.2. TikTok’s ‘For You Page’:

TikTok’s algorithm filtered content based on micro-interactions (e.g., replay, pause, comment length), which led to increasingly radical videos being shown to users who initially interacted with just one hate-inducing post (Donovan et al., 2023).

5.5.3. Telegram’s Channel Amplification:

Telegram’s lack of moderation policies allowed for unregulated proliferation of hate. Forwarded posts from one channel to hundreds of others created a virality loop without detection, creating a false sense of public consensus.

5.6. Case Studies

On July 26, a deep-fake video circulated on Facebook allegedly showing a student insulting the Quran during a campus debate. The video, traced to a Telegram group titled ‘Digital Purity Movement,’ spread rapidly with hashtags #CrushTheInfidel and #JusticeNow.

- —

Within 12 hours, the student’s identity, photo, address, and phone number were leaked.

- —

A mob of over 300 people attacked the student’s hostel in the early hours of July 27.

- —

Facebook Live was used to stream the attack, garnering over 76,000 views within three hours.

- —

A post-mortem digital audit revealed the original video was manipulated using AI voice replacement and deep-fake software.

In early August, multiple Telegram groups began circulating posts about a ‘foreign-funded plot’ by students of Dhaka University. The term #CleanseTheCampus began trending on TikTok, accompanied by TikToks of armed individuals walking toward campuses.

On 4 August, several residential dorms were attacked, resulting in four deaths and over 25 injuries.

Influencer-led livestreams on Facebook hailed the attackers as ‘national heroes.’

Analysis of Facebook’s ad library revealed at least 23 boosted posts between 3–5 August, all promoting similar narratives, indicating potential paid coordination.

Unlike Sylhet or Dhaka, the Rajshahi incident was rooted in digital lynching. Several students were accused of criticizing the interim government's policies in a private Telegram group. Screenshots of their messages, leaked without context, went viral on Facebook.

On 6 August, one student was assaulted in front of the campus gate.

The attackers claimed to have identified the student from ‘reliable Facebook pages.’

The screenshot was later proven to be doctored using image-editing tools and AI-generated slang that the victim never used.

5.7. Visual and Algorithmic Footprint

Infographic Maps: Network diagrams show clustering of Telegram and Facebook groups with synchronized content across the three cities.

Reach and Impact: Data logs show that top 50 posts associated with violence-related hashtags reached an estimated 13.8 million users in 72 hours.

-

Engagement Stats: Among users engaging with violence-promoting content:

- ○

68% were between ages 18–29

- ○

74% used TikTok as a secondary source after Facebook

The findings reveal a deeply interwoven network of misinformation, emotional manipulation, and algorithmic engagement that allowed for rapid radicalization and real-world violence. The platforms failed to intervene in real time, and the seamless transition from digital accusation to physical punishment marked a dangerous evolution of mob justice in the age of algorithmic governance.

6. Discussion and Analysis

6.1. Social Media as the Epicenter of the 2024 Unrest

The 5 August 2024 unrest in Bangladesh did not simply occur ‘on the streets’; it was born, nurtured, and escalated in the digital realm. Social media platforms, especially Facebook, Telegram, TikTok, and YouTube, acted as both incubators and accelerators of mass mobilization, misinformation, and mob trials. What makes this unrest unique is how deeply algorithmic logic and user behavior were intertwined in shaping both narratives and actions. The violence was not merely spontaneous — it was programmed, recommended, and echoed.

The digital landscape allowed outrage to be algorithmically sorted, served, and spread. Hashtags like #JusticeByPeople, #DigitalVigilante, and #PunishTheBlasphemers trended in multiple districts, linking dispersed, ideologically motivated users into emotionally charged, real-time mobilizations. What would historically require weeks of planning was now executed in hours— facilitated by content virality, echo chambers, and mobilizing memes or manipulated videos.

6.2. Platform Responsibility and Algorithm Design

The algorithmic curation systems of Facebook, TikTok, and Telegram played a central role. These systems prioritize content that triggers emotional reactions — anger, outrage, shock — because such emotions generate higher engagement. During the crisis, the design of recommendation engines and trending feeds created perfect storm conditions:

Facebook’s Recommender Engine actively boosted videos labeled ‘popular near you,’ even if they featured disinformation or incitement.

Telegram’s Channel Infrastructure allowed for closed, unmoderated extremist forums with tens of thousands of followers.

TikTok’s for You Page (FYP) showed repeated ‘reaction videos’ to manipulated or violent clips, often featuring staged mob trials or calls to violence with patriotic music overlays.

The fundamental design flaw here is value-neutral amplification. Algorithms do not differentiate between satire, hate, or truth. They reward engagement. And during August 2024, engagement often meant extremism.

6.3. Political Opportunism and Digital Nationalism

Beyond the platforms, political opportunism must be considered. Several actors exploited the unrest for their gain:

State actors used algorithmically amplified narratives to justify crackdowns on opposition and students.

Nationalist influencers rebranded digital mobs as defenders of ‘religious purity’ or ‘national integrity,’ turning violence into virtue.

Troll farms and coordinated propaganda units spread rumors about foreign plots or minority involvement in ‘anti-Islam’ acts.

This intersection between political ideology and digital virality birthed a new hybrid form: digital nationalism — where patriotism is performative, algorithmically reinforced, and weaponized against internal enemies, real or imagined.

6.4. Echo Chambers, Group Polarization, and Filter Bubbles

Bangladesh’s digital users are increasingly trapped in ideological silos — where they are only exposed to content that confirms their existing beliefs. The algorithm doesn’t just reflect reality; it creates realities. This phenomenon was especially dangerous in:

Sylhet: where digital rumors about a ‘blasphemous student’ led to mobs gathering outside campuses.

Dhaka: where viral videos of street justice became templates for future acts.

Rajshahi: where pro-government and anti-government Telegram groups both circulated deep-fakes to incite fear.

Social media platforms, designed to customize feeds for individual users, end up enclosing users in filter bubbles. Within these bubbles, opposing views are demonized, and the unverified becomes irrefutable.

6.5. Intersection of Digital Emotions and Physical Violence

Perhaps the most alarming feature of the 5 August unrest is the emotive transference from screen to street. People were not merely informed by social media — they were inflamed by it. Likes became endorsements of revenge, shares became calls to action, and emojis became emotional accelerants.

Emoji-reacted mob videos normalized violence.

Posts tagged specific religious communities or activists as ‘targets.’

Re-sharing violent clips built a sense of ‘collective justice.’

The transformation of digital feelings into physical violence underscores the need to understand social media not just as a communication tool— but as an emotive infrastructure.

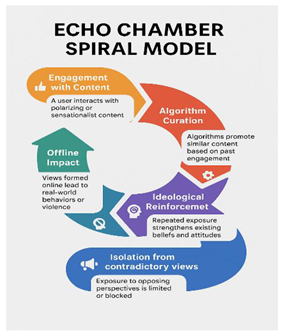

6.6. Visual Suggestion for Section

A spiral chart visually representing how individuals start with moderate beliefs, are gradually exposed to more radical content through engagement, and eventually end up in polarized echo chambers that normalize or glorify violence. This model would use:

Color coding to indicate stages of radicalization.

Icons representing platforms, content types, and reaction metrics.

Arrows showing the circular and recursive nature of digital extremism.

Infographic: Proposed Echo Chamber Spiral Model

6.7. Policy Discourse Implications

This discussion brings critical insight into several domains:

Platform Governance: Current content moderation strategies are insufficient in contexts of rapid linguistic, cultural, and ideological change.

Algorithmic Accountability: Calls for ‘explainable AI’ and transparent recommender systems are essential for democratic stability.

Digital Literacy: Civic education must include training on misinformation, deep-fake recognition, and emotional manipulation online.

Crisis Preparedness: Governments must invest in early warning systems for digital incitement — not just physical threats.

7. Conclusion and Policy Recommendations

7.1. Concluding Reflections: Digital Unrest in the Age of Algorithmic Amplification

The 5 August 2024 unrest in Bangladesh marks a watershed moment in the entanglement of social media, algorithmic radicalization, and political violence. As the evidence presented in this study illustrates, the unrest was not a spontaneous outbreak but the culmination of systemic failures across multiple domains: algorithmic governance, content moderation, platform accountability, digital literacy, and political leadership. These failures coalesced into a volatile digital ecosystem where misinformation, communal hatred, and hyper-partisan narratives flourished unchecked, often with fatal consequences.

At the heart of this crisis lies the structural logic of social media algorithms. These systems are not passive conduits of information; they are active agents in shaping user behavior, emotional engagement, and ultimately, collective action. The events leading up to and following 5 August 2024 clearly demonstrate that algorithmic curation mechanisms — designed to optimize for engagement — inadvertently (or perhaps inevitably) facilitated the circulation of inflammatory, misleading, and often violent content.

This study contributes to a growing body of literature (e.g., O’Callaghan et al., 2021; Donovan & boyd, 2020; Ghosh, 2023) that calls for a critical reassessment of the role of platforms as neutral intermediaries. In environments marked by political fragility and ethnic or religious fault lines — such as Bangladesh — the stakes of inaction are especially high. When platforms remain opaque about how content is prioritized and promoted, they not only facilitate disinformation but also enable algorithmic injustice.

Equally important is the role of human agency — state actors, political influencers, digital mobs, and even bystanders who choose to react, share, or remain silent. As such, the response to this digital crisis must be multi-layered, involving not only technological reform but also institutional resilience, civic education, and ethical governance.

7.2. Call for Algorithmic Transparency and Platform Responsibility

7.2.1. Transparency as a Democratic Imperative

One of the central policy recommendations emerging from this study is the urgent need for algorithmic transparency. Algorithms are often described as ‘black boxes’ — complex, proprietary systems whose inner workings are inaccessible to users and regulators alike. Yet, their impact is profoundly public.

The design of recommender systems on Facebook, TikTok, YouTube, and Telegram must be subject to auditable disclosure. This includes:

Disclosing how engagement metrics influence content ranking.

Releasing regular reports on content virality, especially around sensitive topics (e.g., religion, politics).

Providing accessible, multilingual transparency tools for users to understand why they are seeing particular content.

As Gillespie (2018) argues, platforms are not simply technical infrastructures but ‘custodians of public discourse.’ In this capacity, their algorithms must be auditable in a manner akin to electoral processes or financial systems.

7.2.2. Reforming the Incentive Structures

Current platform incentives — driven by ad revenue and time-on-site metrics — privilege sensational content. This business model must be restructured through:

Regulatory reform: Governments and multilateral bodies should impose penalties for algorithmically induced violence or disinformation (Tufekci, 2020).

Ethical algorithm design: Platforms must incorporate human rights risk assessments into algorithm updates.

Third-party audits: Independent watchdogs should evaluate algorithmic impacts, especially in Global South contexts.

7.3. Recommendations for Platforms, Government, and Civil Society

7.3.1. Recommendations for Social Media Platforms

- 2.

-

Transparent Disinformation Labeling:

- ○

Tag manipulated content with contextual overlays or fact-check links.

- ○

Limit virality of unverified content during declared digital emergencies.

- 3.

-

Limit Algorithmic Amplification of Sensitive Content:

- ○

Temporarily reduce algorithmic reach of certain hashtags or terms during high-risk periods (Cinelli et al., 2021).

- ○

Require a ‘human in the loop’ mechanism for content flagged as potentially inciting violence.

- 4.

-

Open API Access for Researchers:

- ○

Grant verified researchers real-time access to anonymized data to monitor digital trends, hate speech, and misinformation spikes.

7.3.2. Recommendations for Government and Regulatory Bodies

- 2.

-

Mandate Algorithmic Impact Assessments (AIA):

- ○

Prior to deployment of new recommendation systems, platforms must submit AIA reports outlining risks to social cohesion.

- 3.

-

Introduce Legislation on Digital Incitement and Deep-fake Proliferation

- ○

Enforce criminal liability for production and mass dissemination of synthetic or manipulated media.

- 4.

-

Create a National Digital Literacy Curriculum

- ○

Introduce compulsory training in schools and universities on digital ethics, media verification, and online safety.

- 5.

-

Digital Early Warning System (DEWS)

- ○

Develop predictive models in collaboration with universities and civil society to monitor digital unrest precursors.

7.3.3. Recommendations for Civil Society and Academia

- 2.

-

Youth-Centered Digital Campaigns:

- ○

Engage students in co-creating content that promotes empathy, digital responsibility, and counter-narratives.

- 3.

-

Interfaith Digital Dialogues:

- ○

Support online forums where religious and ethnic groups can address grievances in moderated, constructive environments.

- 4.

-

Expand Research on Algorithmic Violence in South Asia:

- ○

Fund interdisciplinary research into how algorithmic curation intersects with religious, ethnic, and political violence in fragile democracies (Nieborg & Poell, 2018).

7.4. Future Research Directions

The findings of this study open several avenues for further inquiry:

7.4.1. Comparative Algorithmic Studies in the Global South

Future research should conduct comparative studies across countries with similar digital ecosystems — such as India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Myanmar— to examine how algorithmic radicalization manifests in differing socio-political climates.

7.4.2. Mapping the Infrastructure of Disinformation Networks

Employ network analysis tools to trace the lifecycle of misinformation— from creation and amplification to offline mobilization. This could include:

7.4.3. Gendered and Intersectional Impacts

Women, religious minorities, and marginalized ethnic groups often bear the brunt of digital violence. Future work must explore the intersectional vulnerabilities within algorithmically mediated unrest.

7.4.4. Psychological Impacts of Algorithmic Engagement

There is a need for interdisciplinary research combining psychology and digital humanities to understand how algorithmically curated content affects mental health, political identity, and aggression.

7.4.5. Decolonizing Platform Governance

Most platforms are governed by corporate offices in the Global North. Research should explore what decolonized platform governance might look like— prioritizing community-based moderation, multilingual transparency, and local data sovereignty.

7.5. Final Thoughts

The digital space in Bangladesh, and across much of the Global South, stands at a crossroads. If left unchecked, the forces of algorithmic radicalization, digital vigilantism, and platform apathy will erode the very foundations of democratic discourse. Yet, this is not an inevitability. With the right combination of ethical platform design, responsive governance, and empowered civil society, a more humane and equitable digital future is possible. The 5 August 2024 unrest must be remembered not only as a tragedy but also as a catalyst— a wake-up call to reimagine the terms on which we engage with technology, truth, and each other.

Emoji-reacted mob videos normalized violence.

Emoji-reacted mob videos normalized violence. Posts tagged specific religious communities or activists as ‘targets.’

Posts tagged specific religious communities or activists as ‘targets.’ Re-sharing violent clips built a sense of ‘collective justice.’

Re-sharing violent clips built a sense of ‘collective justice.’