Submitted:

27 May 2025

Posted:

28 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1:. Introduction

1.1. Background of the Study

1.2. Contextualizing Generation Z in Bangladesh

1.2.1. Introduction

1.2.2. Demographic Profile of Generation Z in Bangladesh

1.2.3. Mobile-first Digital Natives

1.2.4. Education and Digital Literacy

1.2.5. Cultural Pressures and Digital Norms

1.2.6. Political Landscape and Civic Engagement

1.2.7. Platform-specific Trends

- a)

- Facebook remains the most widely used platform for communication, content sharing, and community formation.

- b)

- YouTube serves as a major avenue for infotainment and tutorial-based learning.

- c)

- TikTok has emerged as a performance-centric space that allows youth—particularly from lower-income and rural backgrounds—to express themselves creatively, though not without facing moral backlash.

- d)

- WhatsApp, Telegram, and Signal are used for private group communication, often becoming spaces for memes, political chatter, or information exchange.

- e)

- Instagram is seen as aspirational, associated with lifestyle branding, influencer culture, and aesthetic expression, mostly among upper-middle-class youth.

1.2.8. Gender, Class, and Identity Politics

1.2.9. Digital Mental Health

1.2.10. The Role of Family and Religion

1.3. Problem Statement

1.4. Research Objectives

1.4.1. To Examine Gen Z’s Attitudes Toward Social Media Usage

1.4.2. To Investigate Behavioral Patterns in Online Communication and Engagement

1.4.3. To Analyze the Influence of Social Norms on Digital Behavior and Identity

1.4.4. To Assess the Role of Algorithmic Platforms in Shaping Perceptions and Trends

1.4.5. To Explore the Impacts of Social Media Engagement on Mental Health, Peer Relationships, and Offline Behavior

1.4.6. To Understand Digital Literacy and Awareness Among Gen Z Users

1.4.7. To Provide Policy Recommendations for Educators, Policymakers, and Technology Platforms

1.5. Research Questions

- What are the dominant attitudes of Gen Z in Bangladesh toward social media use?

- How do Gen Z users in Bangladesh behave on social media platforms in terms of content creation, interaction, and engagement?

- What social norms are emerging among Gen Z as a result of social media use, and how are they internalized?

- How do factors such as gender, socio-economic background, and educational access mediate these digital behaviors and norms?

- What are the implications of these findings for digital education, youth mental health, and social cohesion in Bangladesh?

1.6. Significance of the Study

1.7. Conceptual Framework

- Social Norms Theory (Cialdini & Trost, 1998): Helps explain how perceived norms influence individual behavior on social platforms.

- Goffman’s Presentation of Self (1959): Provides a lens through which to analyze how Gen Z performs identity online.

- Uses and Gratifications Theory (Katz, Blumler, & Gurevitch, 1973): Offers insights into the motivations driving social media usage among young users.

- Networked Individualism (Rainie & Wellman, 2012): Captures the shift from group-based interactions to individual-centered digital networking.

1.8. Scope and Limitations

2. Literature Review

2.1. Introduction to the Literature Landscape

2.2. Global Perspectives on Social Media and Youth Behavior

2.2.1. Digital Native Identity and Socialization

2.2.2. Behavioral Trends and Algorithmic Influences

2.2.3. Social Norms in Online Spaces

2.3. Theoretical Contributions on Social Norms and Digital Behavior

2.3.1. Social Norms Theory

2.3.2. Goffman’s Presentation of Self

2.3.3. Uses and Gratifications Theory

2.3.4. Networked Individualism

2.4. Regional Insights from South Asia

2.4.1. Social Media and Youth in South Asia

2.4.2. Online Norms and Social Sanctions

2.5. National Studies on Users of Bangladesh Youth and Digital Culture

2.5.1. Digital Expansion in Bangladesh

2.5.2. Identity Performance and Gendered Use

2.5.3. Digital Norms and Behavioral Regulation

2.6. Gaps in the Literature

- a)

- Limited empirical data: There is a scarcity of large-scale empirical studies that analyze the interaction of attitudes, behaviors, and norms among Users of Bangladesh Gen Z users.

- b)

- Gender-focused insights: While gender is often cited, few studies deeply explore how normative pressures differ across male, female, and non-binary youth in Bangladesh.

- c)

- Platform-specific analysis: Most studies examine Facebook and TikTok; little is known about newer platforms like Instagram Reels, Snapchat, or Telegram.

- d)

- Psychological outcomes: More research is needed on how internalized digital norms affect self-esteem, anxiety, and interpersonal relationships.

- e)

- Intersectionality: The role of class, language, religion, and urban-rural divides in shaping digital norms among Gen Z is under-researched.

3. Study Methodology

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Research Objectives

- To investigate the extent to which users in Bangladesh and other global contexts perceive social media as a toxic environment.

- To identify key psychological, emotional, and social impacts associated with prolonged social media exposure.

- To analyze the influence of digital algorithms, content moderation, and political interventions on the circulation of toxic content.

- To compare the experiences of users in Bangladesh with global and regional trends, especially in South Asia.

3.3. Research Questions

- How do users in Bangladesh experience and define toxicity on social media?

- What types of toxic content (e.g., misinformation, cyberbullying, hate speech) are most prevalent?

- What psychological and behavioral consequences are associated with exposure to toxic social media environments?

- How do global and regional patterns of social media toxicity compare with those observed in Bangladesh?

3.4. Population and Sampling

3.4.1. Study Population

3.4.2. Sampling Method

3.5. Data Collection Methods

3.5.1. Quantitative Data Collection

- Demographic Information

- Patterns of Social Media Usage

- Perceptions of Toxic Content

- Emotional and Psychological Impact Assessment

- Algorithmic Awareness and Content Moderation Perception

3.5.2. Qualitative Data Collection

3.6. Data Analysis Techniques

3.6.1. Quantitative Data Analysis

3.6.2. Qualitative Data Analysis

3.7. Ethical Considerations

- a)

- Informed Consent: All participants provided informed consent after receiving a detailed explanation of the research objectives, methods, and their right to withdraw.

- b)

- Confidentiality: Data were anonymized, and any identifiers removed during analysis and reporting.

- c)

- Ethical Approval: The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Institutional Review Board.

- d)

- Digital Ethics: For content analysis, only publicly available posts were used. No private or encrypted data were accessed.

3.8. Validity and Reliability

- a)

- Triangulation: Used multiple data sources (surveys, interviews, content analysis) to cross-verify findings.

- b)

- Member Checking: Participants in interviews were asked to review transcripts for accuracy.

- c)

- Peer Debriefing: Regular discussions with colleagues and supervisors helped refine categories and interpretations.

- d)

- Pilot Testing: The survey instrument was piloted with 50 participants to test clarity, internal consistency, and technical operability.

3.9. Limitations of the Study

- Self-report Bias: Participants may underreport or over-report experiences due to social desirability.

- Digital Access: Rural populations with limited internet access may be underrepresented.

- Platform Constraints: The focus was primarily on Facebook, TikTok, and X, potentially omitting platform-specific phenomena on Reddit, Instagram, or Discord.

- Temporal Limitation: The data reflects patterns up to 2024; new trends emerging post-2025 may not be captured.

3.10. Comparative Framework

- United States (high HDI, high freedom, high toxicity visibility)

- United Kingdom (high HDI, medium moderation policies)

- India (medium HDI, high digital population, medium censorship)

- Sri Lanka (low-medium HDI, political instability)

- Bangladesh (medium HDI, rising censorship, high platform dependence)

3.11. Justification for Methodology

- Holistic Perspective: Mixed methods allow for a 360-degree view of toxicity across psychological, technological, and sociopolitical dimensions.

- Contextual Relevance: In-depth, context-sensitive qualitative data are essential for understanding nuances in Users of Bangladesh digital culture.

- Scalability: Quantitative data provides population-level insights, which can inform platform governance and public policy.

3.12. Timeline

| Phase | Duration | Activities |

| Phase 1 | Jan–Feb 2024 | Literature Review, Instrument Design |

| Phase 2 | Mar–Apr 2024 | Pilot Testing, Ethical Approval |

| Phase 3 | May–July 2024 | Data Collection (Surveys + Interviews + FGDs) |

| Phase 4 | Aug–Oct 2024 | Data Analysis |

| Phase 5 | Nov–Dec 2024 | Comparative Analysis, Drafting |

| Research Component | Details |

| Research Design | Hybrid-Methods Design (Quantitative and Qualitative |

| Sampling Techniques | Stratified random Sampling Across Regions and Institutions |

| Sample Size and Demographics | 1200 Participants; aged 18-25, Urban and Rural Gen Z respondents |

| Data Collection Tools | Online Survey questionnaire and semi-structured interviews |

| Data Analysis Approach | Descriptive stats, thematic coding, SPSS for quant. NVivo for qualitative analysis |

| Ethical Considerations | Informed consent, anonymity, URB clearance |

4:. Findings

4.1. Introduction

4.2. Attitudes Toward Social Media

4.2.1. General Sentiment

4.2.2. Platform-Specific Perceptions

4.3. Behavioral Patterns of Gen Z Users

4.3.1. Frequency and Time Spent

| Platform | Mean Daily Time (hours) | SD |

|---|---|---|

| 1.4 | 0.9 | |

| 1.1 | 0.7 | |

| TikTok | 0.8 | 0.6 |

| YouTube | 1.2 | 0.8 |

| Twitter/X | 0.3 | 0.5 |

4.3.2. Online Behaviors and Trends

4.3.3. Surveillance and Self-Censorship

4.4. Emerging Social Norms

4.4.1. Norms of Visibility and Performance

4.4.2. Cancel Culture and Digital Shaming

4.5. Gendered Experiences and Digital Inequality

4.6. Algorithmic Influence and Perceived Manipulation

4.6.1. Echo Chambers and Political Manipulation

4.6.2. Virality and Validation

4.7. Psychological Impacts and Coping Mechanisms

4.7.1. Anxiety, FOMO, and Burnout

4.7.2. Coping Strategies

4.8. Summary of Key Quantitative Findings

- a)

- 87.6% consider social media essential to daily life.

- b)

- 63.4% frequently encounter toxic behavior, especially on Facebook.

- c)

- Average social media use: 3.9 hours/day.

- d)

- 41.2% feel pressured to maintain a ‘perfect’ digital persona.

- e)

- Female and queer users report higher rates of harassment and self-censorship.

- f)

- 72.5% experience algorithmic echo chambers.

- g)

- 61.3% suffer from FOMO, yet only 17.4% practice digital detoxing.

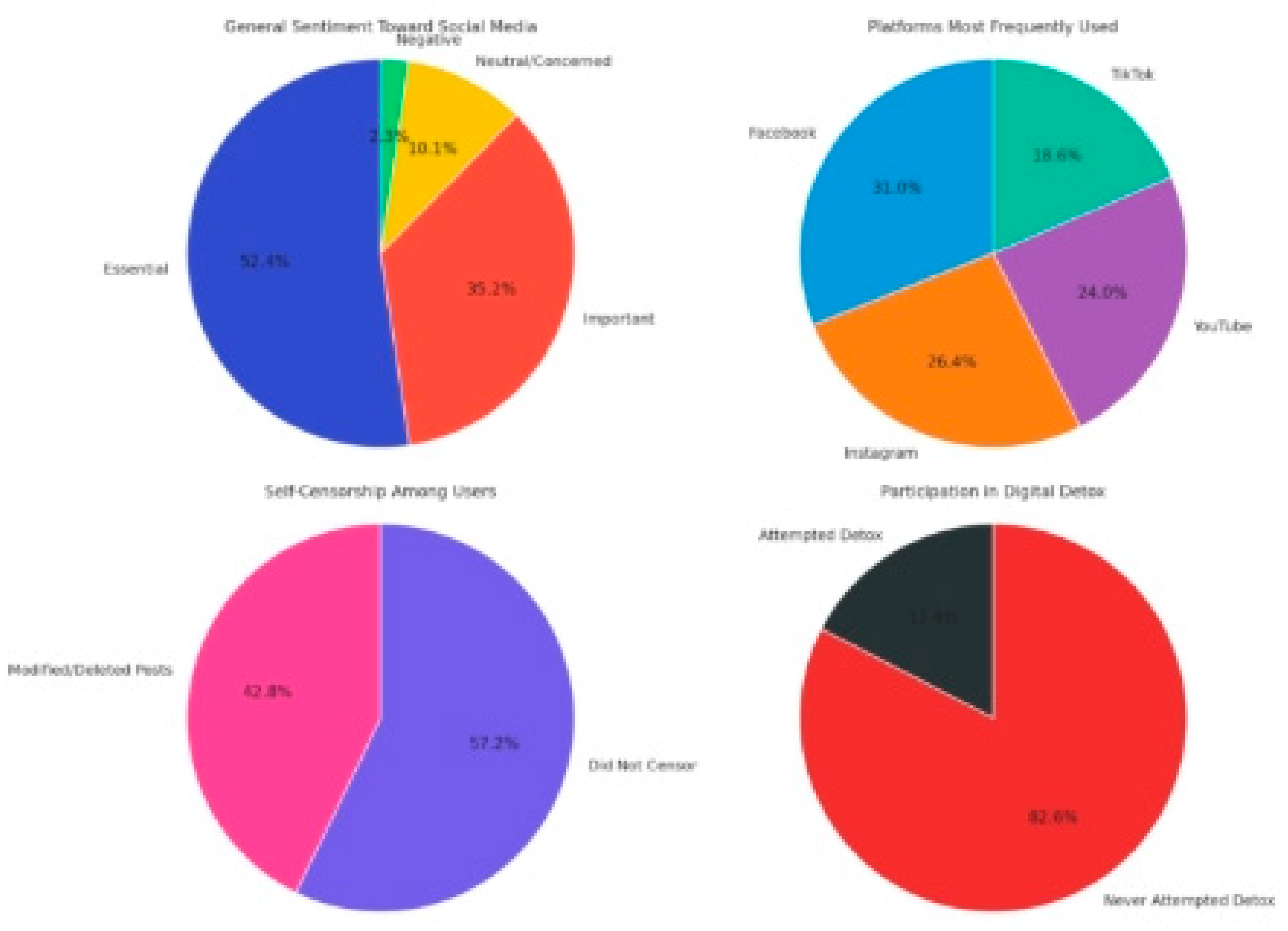

- General Sentiment Toward Social Media – Shows that a majority of Gen Z users in Bangladesh view social media as essential or important.

- Platforms Most Frequently Used – Facebook and Instagram dominate, followed by YouTube and TikTok.

- Self-Censorship Among Users – Indicates that a notable portion of users have modified or deleted content due to social norms or peer pressure.

- Participation in Digital Detox – Reveals that while digital detox is discussed, most users have not engaged in it.

5:. Discussion and Interpretation

5.1. Introduction to Discussion

5.2. Revisiting the Theoretical Framework

- Goffman’s dramaturgical model emphasizes identity construction in virtual settings akin to stage performances. Social media profiles are ‘front stage’ performances, managed through strategic impression formation (Goffman, 1959).

- Bandura’s Social Learning Theory suggests that behaviours, especially those mediated by digital environments, are learned through observation, imitation, and reinforcement (Bandura, 1977). Social media influencers, peer behavior, and feedback mechanisms (likes, shares, comments) serve as models and reinforcers.

- Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behavior (1991) provides a valuable lens to interpret how attitudes toward digital life, perceived social norms, and behavioural control determine Gen Z’s social media actions (Ajzen, 1991).

5.3. Interpretation of Key Findings in Light of the Framework

5.3.1. Identity Curation and Performative Behaviour (Goffman)

5.3.2. Behavioural Reinforcement and Social Learning (Bandura)

5.3.3. Attitude-Norm-Behaviour Relationships (Ajzen)

5.4. Connecting with Research Questions

5.5. Implications for Social Norms, Digital Behaviour, and Identity

- Digital platforms are increasingly shaping what is seen as ‘normal,’ thus affecting identity construction at formative life stages.

- Gendered implications are stark. Female respondents face stricter surveillance and often resort to anonymous or encrypted communication.

- Rural-urban divides persist in digital fluency, with rural respondents reporting lower digital literacy and higher exposure to cyber-harassment.

5.6. Generational Patterns and Cultural Nuances

5.7. Limitations and Future Research Directions

6:. Conclusions and Recommendations

6.1. Introduction

6.2. Summary of Key Findings

6.2.1. Duality of Attitudes

6.2.2. Behavioural Patterns Governed by Social Norms

6.2.3. Algorithmic Conditioning of Habits

6.2.4. Gendered and Classed Dimensions of Digital Engagement

6.3. Theoretical and Practical Implications

6.3.1. Reframing Digital Citizenship

6.3.2. Implications for Media Literacy Policies

- Critical thinking about content sources and algorithmic biases

- Ethical norms of online behavior

- Tools for mental health management and digital well-being

- Gender-sensitive training for safe navigation

6.3.3. Platform Governance and Algorithmic Accountability

6.4. Policy Recommendations

6.4.1. National Digital Literacy Framework

6.4.2. Gender-Inclusive Digital Policies

6.4.3. Algorithmic Transparency Legislation

6.4.4. Decentralized Content Moderation

6.4.5. Youth Participation in Policy Formulation

6.5. Suggestions for Future Research

6.5.1. Longitudinal Studies on Digital Identity Formation

6.5.2. Comparative Studies across South Asia

6.5.3. Intersectional Digital Studies

6.5.4. Impact of AI and Emerging Technologies

6.5.5. Role of Vernacular Languages in Digital Norms

6.6. Concluding Reflections

References

- Ahmed, S.; Rabbani, G. Digital surveillance, agency, and gendered spaces: Understanding young women’s use of pseudonyms on Users of Bangladesh social media. Media, Culture & Society 2022, 44, 1254–1273. [Google Scholar]

- Akter, F.; Rahman, M. Adolescents and digital behavior in urban Bangladesh. Journal of Youth and Media 2022, 10, 101–117. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, R.; Jahan, F. Digital inequality and youth access in Bangladesh: A comparative study of urban and rural students. Information Technology for Development 2022, 28, 59–75. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, M.; Jiang, J. (2018). Teens, social media & technology 2018. Pew Research Center.

- Arora, P.; Rangaswamy, N. Digital leisure for development: Rethinking new media practices from the Global South. Media, Culture & Society 2013, 35, 998–1011. [Google Scholar]

- Azim, M.E.; Rashid, M.M. The duality of Youth Identity in Bangladesh’s Digital Culture. Journal of Youth Studies 2021, 24, 1183–1198. [Google Scholar]

- Banaji, S. Youth and The Politics of the Internet in South Asia. International Communication Gazette 2017, 79, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Banaji, S.; Bhat, R.; Agarwal, A. Youth civic engagement in the digital age: A South Asian perspective. Information, Communication & Society 2018, 21, 1232–1248. [Google Scholar]

- Baulch, E. Digital Moralism and Youth Expression in Indonesia. New Media & Society 2019, 21, 1547–1562. [Google Scholar]

- BBS. (2022). Population and Housing Census 2021. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics.

- Binns, A. Don’t feed the trolls! Managing troublemakers in magazines' online communities. Journalism Practice 2012, 6, 547–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, D. (2010). Social network sites as networked publics: Affordances, dynamics, and implications. In Z. Papacharissi (Ed.), Networked Self: Identity, Community and Culture on Social Network Sites (pp. 39–58). Routledge.

- Boyd, D. (2014). It's complicated: The Social Lives of Networked Teens. Yale University Press.

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BTRC. (2024). Internet subscribers in Bangladesh. February 2024. Bangladesh Telecommunication Regulatory Commission.

- Bucher, T. (2018). If… Then: Algorithmic Power and Politics. Oxford University Press.

- Chua, T.H.H.; Chang, L. Follow me and like my beautiful selfies: Singapore teenage girls’ engagement in self-presentation and peer comparison on social media. Computers in Human Behavior 2016, 55, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Trost, M.R. (1998). Social influence: Social norms, conformity and compliance. In D. Gilbert, S. Fiske & G. Lindzey (Eds.), The Handbook of Social Psychology (pp. 151–192). McGraw-Hill.

- Cialdini, R.B.; Reno, R.R.; Kallgren, C.A. A focus theory of normative conduct. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1990, 58, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couldry, N.; Hepp, A. (2017). The Mediated Construction of Reality. Polity Press.

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches (5th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Dhir, A.; Yossatorn, Y.; Kaur, P.; Chen, S. Online social media fatigue and psychological wellbeing—A study of compulsive use, fear of missing out, fatigue, anxiety and depression. International Journal of Information Management 2018, 40, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedom House. (2023). Freedom on the Net 2023: The Repressive Power of Artificial Intelligence. https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net/2023.

- Gillespie, T. The Politics of ‘platforms’. New Media & Society 2010, 12, 347–364. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie, T. (2014). The relevance of algorithms. In T. Gillespie, P. Boczkowski, & K. Foot (Eds.), Media technologies (pp. 167–194). MIT Press.

- Goffman, E. (1959). The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Doubleday.

- GSMA. (2023). The Mobile Economy Asia Pacific 2023. GSMA Intelligence.

- Haque, M.; Kabir, M. The changing dynamics of youth digital culture in Bangladesh. Media Asia 2021, 48, 187–200. [Google Scholar]

- Haque, M.; Murshed, S. Informal digital learning among university students in Bangladesh: Aspirations and constraints. Asian Journal of Communication 2022, 32, 410–426. [Google Scholar]

- HRW. (2024). Bangladesh: Digital Security Act Used to Suppress Dissent. Human Rights Watch.

- Hunt, M.G.; Marx, R.; Lipson, C.; Young, J. No more FOMO: Limiting social media decreases loneliness and depression. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 2018, 37, 751–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, E.; Blumler, J.G.; Gurevitch, M. Uses and gratifications research. The Public Opinion Quarterly 1973, 37, 509–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.A.; Mitu, N.J. Digital youth: Exploring Users of Bangladesh students’ engagement with new media. Journal of Youth Studies 2021, 24, 355–372. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, N.; Alam, M.; Jahan, T. Social media and mental health among adolescents in Bangladesh: A qualitative study. South Asian Journal of Psychiatry 2023, 15, 67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Kuss, D.J.; Griffiths, M.D. Social networking sites and addiction: Ten lessons learned. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2017, 14, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanier, J. (2018). Ten Arguments for Deleting Your Social Media Accounts Right Now. Henry Holt and Company.

- Livingstone, S.; Sefton-Green, J. (2016). The class: Living and learning in the digital age. NYU Press.

- Livingstone, S.; van der Graaf, S.; Kotilainen, S. Media education and digital literacy: Narratives of empowerment across Europe. International Journal of Media & Cultural Politics 2014, 10, 7–20. [Google Scholar]

- Madianou, M. Digital inequality and second-order disasters. Media, Culture & Society 2015, 37, 885–900. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmud, S.; Hossain, T. Social media identity performance among Users of Bangladesh University Students. South Asian Journal of Social Studies 2021, 4, 87–104. [Google Scholar]

- Marwick, A.; Boyd, D. I tweet honestly, I tweet passionately: Twitter users, context collapse, and the imagined audience. New Media & Society 2011, 13, 114–133. [Google Scholar]

- Marwick, A.; Boyd, D. Social media and the imagined audience. New Media & Society 2011, 13, 115–133. [Google Scholar]

- Mozur, P.; Zhong, R.; Krolik, A. (2019). A genocide incited on Facebook. The New York Times.

- Nakamura, L. Afterword: Blaming, shaming, and the feminization of digital labor. Ada: A Journal of Gender, New Media, and Technology 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nesi, J. The impact of social media on youth mental health: Challenges and opportunities. North Carolina Medical Journal 2020, 81, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesi, J.; Prinstein, M.J. Using social media for social comparison and feedback-seeking. Journal of Adolescence 2015, 41, 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Papacharissi, Z. (2012). A networked self: Identity, community, and culture on social network sites. Routledge.

- Papacharissi, Z. (2015). Affective publics: Sentiment, Technology, and Politics. Oxford University Press.

- Rahman, M.; Islam, S. Gender, religion and digital surveillance in Bangladesh. Media Asia 2022, 49, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins, H.W. (2003). The social norms approach to preventing school and college age substance abuse. Jossey-Bass.

- Prensky, M. Digital natives, digital immigrants. On the Horizon 2001, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.A.; Sultana, F. TikTok and Users of Bangladesh youth: Creativity, risk, and class performance. Media Asia 2023, 50, 95–112. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.; Haque, S. Facebook and the politics of fake news in South Asia: Bangladesh in focus. Asian Journal of Communication 2022, 32, 102–120. [Google Scholar]

- Rainie, L.; Wellman, B. (2012). Networked: The New Social Operating System. MIT Press.

- Seemiller, C.; Grace, M. (2016). Generation Z Goes to College. Jossey-Bass.

- Sundar, S.S.; Limperos, A.M. Uses and gratifications 2.0. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 2013, 57, 504–525. [Google Scholar]

- Syeed, A.; Munni, N. Youth, social media and digital protest in Bangladesh. Asian Politics & Policy 2020, 12, 101–119. [Google Scholar]

- Tandon, A.; Dhir, A.; Talwar, S.; Kaur, P.; Mäntymäki, M. Dark consequences of social media-induced fear of missing out (FoMO): Social anxiety and academic performance. Current Psychology 2021, 40, 3077–3086. [Google Scholar]

- Trottier, D. Digital vigilantism as Weaponisation of Visibility. Philosophy & Technology 2017, 30, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turel, O.; He, Q.; Xue, G.; Xiao, L.; Bechara, A. Examination of neural systems sub-serving Facebook ‘addiction’. Psychological Reports 2014, 115, 675–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M. (2017). iGen: Why Today’s Super-Connected Kids Are growing Up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy—and Completely Unprepared for Adulthood. Atria Books.

- Twenge, J.M. (2017). iGen: Why today's super-connected kids are growing up less rebellious, more tolerant, less happy—and completely unprepared for adulthood. Atria Books.

- UNDP Bangladesh. (2023). Digital Literacy and Youth Engagement in Bangladesh. UNDP Policy Brief.

- UNDP. (2022). Human Development Report 2022. United Nations Development Programme. https://hdr.undp.org/.

- UNESCO. (2021). Guidelines on Gender-responsive Digital Education. Paris: UNESCO.

- Walther, J.B. Computer-mediated communication. Communication Research 1996, 23, 3–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.L.; Hamm, M.P.; Shulhan-Kilroy, J. Social media and adolescent well-being: A narrative review. Current Pediatrics Reports 2021, 9, 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. (2023). Bangladesh Urbanization Review.

- Zubair, M.; Fazal, M. (2021). Youth, digital surveillance, and online harassment in Pakistan.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).