1. Introduction

The rise of social media platforms has dramatically altered communication, entertainment, and self-perception. In Bangladesh, TikTok, Facebook Reels, and Instagram Reels have captivated youth, creating what is popularly known as the ‘Reels Generation’ or ‘TikTok Generation.’ These platforms allow users to produce and consume bite-sized visual content with ease. While seemingly innocuous, the excessive engagement with short-form video content has led to increasing concerns regarding mental health outcomes, especially among adolescents and young adults. This paper explores the mental health consequences of this digital phenomenon in the Bangladeshi context.

1.1. Contextualizing the Digital Shift in Bangladesh

Over the past decade, Bangladesh has undergone a rapid digital transformation, with a significant surge in smartphone usage, internet penetration, and access to social media platforms. As of early 2025, the Bangladesh Telecommunication Regulatory Commission (BTRC) reports that over 130 million mobile phone users have access to the internet, with approximately 50 million regularly engaging with social media (BTRC, 2024). Among these platforms, short-form video-sharing apps—most notably TikTok, Instagram Reels, and Facebook Reels—have emerged as dominant forms of digital engagement, especially among the youth population aged between 13 and 25.

These platforms facilitate the creation and consumption of brief, visually dynamic videos set to music or dialogue clips. Initially perceived as sources of entertainment, these reels have rapidly become central to how youth express identity, communicate with peers, pursue digital fame, and navigate socio-economic aspiration. TikTok, in particular, has established itself as a cultural force with considerable reach among youth in both urban and rural Bangladesh. Unlike older forms of social media, which emphasized text or static image-based interactions, reels are inherently performative, algorithmically reinforced, and emotionally immersive.

The TikTok generation— loosely defined as young people whose social engagement, creative self-expression, and social validation are shaped primarily through short-form video platforms—thus represents not just a cohort, but a shifting sociocultural paradigm. While these platforms enable creative democratization and virtual community-building, they have also introduced a constellation of psychosocial challenges. Mental health professionals, educators, and sociologists are increasingly concerned about the emotional and psychological toll these platforms exert on young users (Montag et al., 2021; Ahmed et al., 2023).

1.2. The Rise of Reels: Pleasure, Pressure, and Performativity

Reels are curated to deliver maximum engagement in the shortest amount of time. Their algorithmic architecture is designed to maximize viewer retention through content that triggers instant gratification—frequently using humor, aesthetic appeal, trends, and shock value. This content is served through endless scroll mechanisms, often referred to as ‘doomscrolling’ or ‘dopamine loops’ (Alter, 2017). Young users become entrapped in cycles of consumption and production, rewarded with likes, views, and digital attention.

In Bangladesh, the appeal of reels is often magnified by limited recreational opportunities, socio-economic challenges, and the aspirational appeal of digital fame. Many young people from underprivileged or semi-urban backgrounds have adopted these platforms not merely as forms of entertainment but as potential gateways to stardom or economic mobility. This perceived potential to become an ‘influencer’ or content creator resonates particularly with those who lack traditional pathways to success, such as higher education or stable employment (Kabir & Wahid, 2022).

However, this performative culture also creates intense psychological pressure. Users are encouraged—both by algorithms and social validation logic—to continuously present idealized, edited versions of themselves. This phenomenon exacerbates feelings of inadequacy, comparison anxiety, and impostor syndrome (Twenge, 2019). For adolescents still undergoing identity formation, this validation-dependent environment can be emotionally destabilizing.

1.3. Mental Health: The Invisible Epidemic

Parallel to this digital boom is an often-unseen epidemic: youth mental health disorders. According to the World Health Organization (WHO, 2023), depression and anxiety are now among the leading causes of illness and disability among adolescents worldwide. In Bangladesh, mental health support systems remain weak, stigmatized, and underfunded. Despite the rising prevalence of psychological distress, the National Mental Health Survey (NIMH, 2022) reported that only 8% of affected youths receive any form of professional support.

The situation becomes more acute when we consider the psychological impact of digital technologies, particularly those built on addictive feedback mechanisms like TikTok. International studies have identified a strong correlation between increased screen time and reduced self-esteem, heightened anxiety, and sleep disturbances (Rosen et al., 2022). In the absence of regulatory mechanisms, media literacy programs, or robust mental health infrastructure, Bangladeshi youth are increasingly vulnerable to these digital stressors.

The mental health crisis in Bangladesh is thus being compounded by the omnipresence of short-form video platforms. Beyond the clinical spectrum of mental health disorders, there is a growing phenomenon of digital discontent—characterized by emotional fatigue, mood instability, social withdrawal, and detachment from offline relationships.

1.4. The Algorithmic Trap and Psychological Vulnerability

At the core of the mental health issue lies the algorithmic design of platforms like TikTok and Instagram Reels. These platforms utilize machine learning algorithms to predict and serve content based on user preferences, watch history, and behavioral patterns. While such personalization increases engagement, it also creates echo chambers that reinforce specific emotional states, consumption habits, and visual aesthetics. These echo chambers are not neutral; they guide users toward particular types of content—often those that evoke strong emotions or adhere to prevailing beauty and lifestyle trends.

Young users frequently find themselves caught in these algorithmic feedback loops. A teen experiencing anxiety might be exposed to content that romanticizes or amplifies emotional vulnerability, while another struggling with body image may be served fitness or cosmetic videos promoting unattainable ideals. These algorithmic interventions occur invisibly, often reinforcing existing insecurities rather than alleviating them (Bishop, 2020; Bucher, 2018).

In Bangladesh, where discussions on digital wellbeing and algorithmic ethics are still nascent, these invisible forces shape user behavior and emotional states without scrutiny or resistance. Unlike in countries with digital literacy programs, many Bangladeshi youths lack the tools to critically engage with or resist algorithmic manipulation. This makes the need for research and policy in this area particularly urgent.

1.5. Cultural Transformation and Generational Dissonance

Another dimension of this crisis is the cultural shift engendered by reels. The values promoted by short-form video platforms—instant gratification, curated aesthetics, individualism, and performative success—often clash with traditional Bangladeshi norms centered around community, modesty, delayed gratification, and academic excellence. Parents and educators often find themselves at odds with children who prioritize ‘likes’ and ‘followers’ over grades or social responsibilities.

This generational disconnect is not merely ideological; it has real psychological consequences. Many young users report feeling misunderstood, isolated, or surveilled in their own homes. Some adopt dual personas—one offline to satisfy familial expectations and one online to seek peer validation. This bifurcation of identity can lead to heightened emotional stress and a sense of alienation, especially in conservative or rural contexts where social media usage by young women is still stigmatized (Nasreen & Islam, 2022).

Moreover, this clash generates what could be termed ‘digital shame’—where youth are judged for their online personas, leading to conflict, secrecy, or withdrawal. In turn, these stressors deepen existing mental health vulnerabilities and make it difficult for young people to seek help from their immediate social environment.

1.6. Objectives of the Study

This research aims to:

Investigate the psychological effects of reels and short-form video consumption among youth in Bangladesh.

Explore the behavioral and emotional patterns associated with prolonged engagement on platforms like TikTok.

Examine how algorithmic architectures contribute to mental health vulnerabilities.

Understand the cultural and generational tensions surrounding social media use in Bangladesh.

Recommend educational, technological, and policy-based interventions to address the mental health crisis.

1.7. Research Questions

What are the primary psychological effects experienced by Bangladeshi youth as a result of consuming or creating short-form video content?

How do socio-cultural contexts in Bangladesh influence the experience and perception of platforms like TikTok and Instagram Reels?

What role do algorithms and platform design features play in reinforcing emotional dependency and mental health issues?

How can schools, families, platforms, and policymakers collaborate to mitigate the mental health impacts of reels?

1.8. Significance of the Study

This study is among the first in Bangladesh to systematically explore the intersection of short-form video consumption and youth mental health. Its relevance extends beyond academia to stakeholders such as educators, policymakers, mental health professionals, parents, and digital platforms. At a time when digital technologies are reshaping identity, cognition, and emotional regulation, this research contributes to a critical understanding of the socio-digital risks facing an entire generation. It also adds a crucial South Asian perspective to global discourses on youth, technology, and psychological well-being.

Furthermore, in the post-COVID-19 context, where remote education, isolation, and digital dependency have intensified, understanding the long-term consequences of these shifts is not just timely—it is essential for the psychological resilience of future generations.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Global Perspectives on Short-Form Video Platforms and Mental Health

The emergence of short-form video platforms, notably TikTok, Instagram Reels, and YouTube Shorts, has revolutionized digital content consumption, particularly among adolescents and young adults. These platforms, characterized by algorithm-driven content delivery and user-generated videos, have garnered significant attention in academic research due to their profound impact on users' mental health.

A systematic review by Gentzler et al. (2023) synthesized findings from 20 studies across various countries, revealing a consistent association between excessive TikTok use and increased symptoms of depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbances among adolescents. The review highlighted that passive consumption of content, as opposed to active engagement, was more strongly correlated with negative mental health outcomes. This distinction underscores the importance of user interaction patterns in determining psychological impacts.

Further, a cross-sectional study conducted in Greece found that adolescents who spent an average of 2.77 hours daily on TikTok exhibited higher levels of anxiety, depression, and daytime sleepiness. The study utilized the TikTok Addiction Scale (TTAS) to measure problematic usage, revealing that factors such as mood modification and tolerance were predominant among users, indicating a reliance on the platform for emotional regulation (Papadopoulos et al., 2024).

Moreover, research by Zahra et al. (2022) in Pakistan employed structural equation modeling to examine the mediating role of academic performance between TikTok addiction and mental health. The findings indicated that excessive TikTok use negatively impacted academic performance, which in turn exacerbated symptoms of depression and anxiety among university students. This study emphasizes the cascading effects of social media addiction on various aspects of adolescents' lives.

2.2. The Bangladeshi Context: Cultural Nuances and Digital Engagement

In Bangladesh, the rapid proliferation of smartphones and affordable internet access has facilitated widespread adoption of social media platforms among the youth. However, the cultural and societal context introduces unique dynamics in the interaction between social media usage and mental health.

Hossain and Ahsan (2024) conducted a qualitative study involving in-depth interviews with Bangladeshi teenagers, educators, and social media experts to explore the impact of short-form videos on self-esteem and behavior. The study revealed that exposure to curated, idealized content on platforms like TikTok and Instagram Reels fosters social comparison, leading to lowered self-esteem, particularly among female adolescents. The algorithm-driven nature of these platforms encourages compulsive usage, intensifying body image concerns and addictive behaviors.

Chowdhury and Ahsan (2024) further examined the relationship between social media use and body dissatisfaction among Bangladeshi youth. Their mixed-methods study found that young women aged 15-18 were most affected, with 13.47% expressing dissatisfaction with their bodies due to exposure to idealized beauty standards online. This dissatisfaction was closely linked to mental health challenges such as anxiety and depression.

Additionally, a study by Hossain and Ahsan (2024) highlighted the role of family dynamics in shaping social media consumption among Bangladeshi teenagers. Parental mediation, prevalent in Bangladeshi households, serves both as a protective factor and a source of conflict regarding media usage. The study emphasized the need for targeted digital literacy initiatives and increased parental involvement to promote healthier social media habits among adolescents.

2.3. Algorithmic Influence and Psychological Vulnerability

The algorithmic architecture of short-form video platforms plays a pivotal role in influencing user behavior and psychological well-being. These algorithms are designed to maximize user engagement by delivering personalized content based on user preferences and interactions.

Nguyen et al. (2023) discussed the challenges of navigating trustworthy mental health information on video-sharing platforms like TikTok. The unregulated growth of mental health content and creators on these platforms poses risks of misinformation, potentially exacerbating users' mental health issues. The study emphasized the need for mechanisms to identify and mitigate mental health misinformation on such platforms.

Furthermore, the phenomenon of ‘echo chambers,’ where users are repeatedly exposed to similar content, can reinforce negative emotional states. Dr. Corey Basch highlighted that TikTok's algorithm could create such echo chambers, leading users to be bombarded with content related to anxiety or despair, potentially resulting in a harmful cycle (Wikipedia, 2025).

In the Bangladeshi context, the lack of digital literacy and awareness about algorithmic influences makes adolescents particularly vulnerable to these effects. The compulsive engagement with algorithmically curated content can lead to increased screen time, disrupted sleep patterns, and heightened anxiety levels among youth.

2.4. Gender Disparities in Social Media Impact

Gender differences significantly influence the psychological impact of social media usage among adolescents. Studies have consistently shown that female adolescents are more susceptible to the negative effects of social media, particularly concerning body image and self-esteem.

A study by Hossain and Ahsan (2024) found that Bangladeshi girls are more likely to compare themselves based on appearance, leading to increased body dissatisfaction and lower self-esteem. In contrast, boys tend to focus on possessions and lifestyle in their comparisons. This constant exposure to ‘perfect’ lives on social media platforms can harm self-worth, especially when teens lack guidance on interpreting the content they consume.

Additionally, the prevalence of cyberbullying and negative peer feedback on social media platforms exacerbates these issues. Approximately 34.6% of participants in Chowdhury and Ahsan's (2024) study reported receiving negative comments or body-shaming messages online, leading to feelings of inadequacy and a decline in self-esteem.

2.5. Sleep Disturbances and Academic Performance

Excessive use of social media platforms, particularly during nighttime, has been linked to sleep disturbances among adolescents. The blue light emitted by screens can disrupt circadian rhythms, leading to insomnia and poor sleep quality.

Research indicates that adolescents who engage in prolonged social media use experience delayed bedtimes, altered sleep duration, and daytime fatigue. These sleep disturbances can negatively impact academic performance, concentration, and overall mental health (Rosen et al., 2022).

In Bangladesh, the integration of social media into daily routines, coupled with academic pressures, exacerbates these issues. The lack of awareness about healthy screen habits and the absence of structured guidelines for social media usage contribute to the deterioration of sleep quality and academic performance among Bangladeshi youth.

2.6. Mental Health Content on TikTok: Opportunities and Risks

While social media platforms pose risks to mental health, they also offer opportunities for mental health support and awareness. TikTok, for instance, has launched campaigns to promote mental health awareness, collaborating with local creators and organizations in Bangladesh to enhance the platform's mental health resources (The Daily Star, 2023).

However, the efficacy of mental health content on these platforms is subject to scrutiny. Jabbar et al. (2024) analyzed the role of TikTok in mental health support, finding that higher engagement with mental health content was positively associated with self-reported mental health benefits. Nonetheless, the study also highlighted the risks associated with algorithm-driven recommendations, which may not always align with users' needs and could potentially expose them to harmful content.

Therefore, while platforms like TikTok have the potential to serve as avenues for mental health support, it is crucial to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the content disseminated. Implementing content moderation policies and promoting digital literacy can help mitigate the risks associated with mental health misinformation on these platforms.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

This study adopts a convergent hybrid-methods research design, combining quantitative and qualitative approaches to examine the influence of social media reels and TikTok on the mental health of youth in Bangladesh. The decision to employ a mixed-methods framework stems from the complexity of the research topic, which necessitates both numerical analysis and an in-depth exploration of participants’ lived experiences.

According to Creswell and Plano Clark (2018), a mixed-methods approach is appropriate when neither quantitative nor qualitative data alone can adequately capture the full scope of the research problem. In this study, the quantitative component helps measure the prevalence and intensity of psychological symptoms related to social media use, while the qualitative part explores subjective perceptions, emotional responses, and socio-cultural contexts.

The study's guiding epistemological stance is constructivist, acknowledging that individual realities are shaped by social, cultural, and technological interactions. This aligns with interpretivist traditions, particularly when understanding how youth in Bangladesh emotionally and cognitively interpret their social media environments.

3.2. Research Objectives

The methodology is structured around the following objectives:

To assess the extent and patterns of TikTok and reels usage among Bangladeshi youth.

To measure correlations between time spent on these platforms and mental health indicators such as anxiety, depression, and self-esteem.

To explore the emotional and behavioral responses to algorithmic content, body image comparison, peer validation, and screen time habits.

To identify socio-cultural, economic, and gendered dimensions of mental health vulnerability exacerbated by social media.

To evaluate user narratives and testimonies to uncover emerging themes of digital stress, addiction, and identity conflicts.

3.3. Study Area and Demographic Scope

The study was conducted across five urban and semi-urban districts in Bangladesh: Dhaka, Chattogram, Rajshahi, Sylhet, and Barisal. These locations were selected to ensure geographic, linguistic, and class diversity, capturing both metropolitan and semi-rural social media engagement patterns. The focus demographic includes:

Youth aged 14–25 years

Enrolled in secondary schools, colleges, and universities

From diverse economic backgrounds, including both urban middle-class and peri-urban lower-income families

Regular users of TikTok, Instagram Reels, and/or Facebook Shorts

This age group represents the largest consumer base of short-form video platforms and is statistically more vulnerable to online addiction, identity crisis, and mental health deterioration (Papadopoulos et al., 2024; Chowdhury & Ahsan, 2024).

3.4. Sampling Methodology

A multi-stage purposive sampling strategy was employed:

3.4.1. Quantitative Sampling

For the survey component, 1,200 respondents were selected through stratified purposive sampling. The strata included age groups (14–18, 19–21, 22–25), gender, and geographical area. Participants were approached via educational institutions, community youth organizations, and digital youth networks.

3.4.2. Qualitative Sampling

A total of 60 participants were selected for in-depth interviews (IDIs) and 8 focus group discussions (FGDs). Criteria included:

Self-reported TikTok or reels usage of 2+ hours daily

Self-identified experiences of anxiety, stress, depression, or body image concerns

Representation across gender, class, and digital literacy levels

Key informants such as mental health professionals, school counselors, digital activists, and social media influencers were also interviewed (n=15) to provide expert insights.

3.5. Data Collection Instruments

3.5.1. Quantitative Survey Tool

A structured questionnaire was developed based on validated scales:

Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21) (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995)

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES) (Rosenberg, 1965)

Social Media Addiction Scale for Adolescents (SMASA) adapted from Andreassen et al. (2016)

The questionnaire also included items on:

Frequency and duration of TikTok/reels use

Nature of viewed content (e.g., comedy, beauty, activism)

Engagement metrics (likes, comments, shares)

Self-reported sleep patterns and academic impact

Pilot testing with 50 respondents was conducted to ensure reliability (Cronbach's alpha: DASS = 0.87, RSES = 0.82).

3.5.2. Interview Guides

Semi-structured interview guides were designed to explore:

Emotional experiences while using reels or TikTok

Peer pressure, self-image, and online validation

Algorithmic personalization and psychological influence

Cultural taboos and parental control

Coping strategies and support systems

FGDs included projective techniques (e.g., story completion, visual mapping) to help participants articulate their digital experiences.

3.6. Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of a leading public university in Rajshahi. The following ethical protocols were observed:

Informed consent was collected from all participants; parental consent was obtained for those under 18.

Confidentiality was assured through data anonymization and secure data storage.

Participants were offered referral information for psychological counseling if signs of distress emerged during interviews.

Interviews were conducted in participants’ preferred language (Bangla or English) and at venues of their convenience.

3.7. Data Collection Timeline

- a)

Quantitative survey: November 2024 – January 2025

- b)

Qualitative interviews and FGDs: December 2024 – March 2025

- c)

Transcription and translation: January – March 2025

- d)

Data cleaning and analysis: February – April 2025

3.8. Data Analysis Techniques

3.8.1. Quantitative Data Analysis

Data was coded and analyzed using SPSS v29. Analytical procedures included:

- a)

Descriptive statistics (frequencies, means, SD)

- b)

Bivariate correlation (Pearson’s r) between social media usage and DASS/RSES scores

- c)

Regression analysis to identify predictors of depression and anxiety

- d)

ANOVA to assess demographic variations

3.8.2. Qualitative Data Analysis

Interviews and FGDs were transcribed verbatim and analyzed using NVivo 14.

Thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) was used to identify patterns across interviews.

Codes were generated inductively and clustered into themes such as ‘online identity,’ ‘emotional fatigue,’ ‘algorithmic control,’ ‘digital peer pressure,’ and ‘self-regulation.’

Inter-coder reliability was ensured with two independent researchers.

3.9. Triangulation and Validity

Triangulation across data sources (surveys, interviews, expert opinions), methods (quantitative vs. qualitative), and locations enhanced the validity of the findings. Member checking was performed with selected participants to verify interpretative accuracy.

3.10. Limitations of the Methodology

While robust in scope and diversity, the methodology faced the following limitations:

Self-reported mental health symptoms may not reflect clinical diagnoses.

Urban and semi-urban focus excludes rural areas where digital engagement patterns differ.

The cross-sectional nature of the study does not allow causal inference.

Social desirability bias may influence responses, especially in FGDs.

3.11. Reflexivity Statement

The researchers maintained a reflexive journal throughout the data collection and analysis phases to account for their positionality, biases, and emotional responses. Special care was taken to remain empathetic but neutral during interviews, especially with vulnerable participants.

4. Findings and Analysis

This section presents the key findings of the research, organized around major thematic areas derived from both quantitative survey data and qualitative insights from in-depth interviews (IDIs), focus group discussions (FGDs), and key informant interviews (KIIs). The analysis integrates descriptive and inferential statistical results with thematic narratives to develop a comprehensive understanding of how social media reels, particularly TikTok, influence the mental health of young users in Bangladesh.

4.1. Demographic Overview of Respondents

Out of the 1,200 survey respondents, 53.6% identified as female, 45.8% as male, and 0.6% as non-binary. The age distribution was as follows: 14-18 years (38.5%), 19-21 years (33.2%), and 22-25 years (28.3%). Urban residents made up 64% of the sample, while 36% came from peri-urban areas. Most respondents were enrolled in educational institutions: high school (28%), college (42%), and university (30%).

4.2. Patterns of Social Media Reels and TikTok Usage

Quantitative data revealed that 91.3% of respondents used TikTok regularly, with 73.2% reporting daily use. Instagram Reels and Facebook Shorts followed, used by 66.5% and 48.1% of participants, respectively. Among TikTok users, 62.4% spent 2–4 hours per day on the app, while 17.6% reported more than 5 hours of daily use.

The content consumed included:

- a)

Comedy (65%)

- b)

Beauty and fashion (48%)

- c)

Dance and lip-sync videos (44%)

- d)

Political and awareness content (20%)

- e)

Religious or motivational content (16%)

Younger adolescents (14–18 years) were more inclined towards entertainment and beauty content, whereas older participants (22–25 years) engaged more with political or self-help videos.

4.3. Psychological Symptoms and Social Media Exposure

The Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21) scores indicated that:

38.6% of respondents fell into the moderate-to-severe depression range

42.4% reported moderate-to-severe anxiety

29.5% reported moderate-to-severe stress

Regression analysis showed a strong positive correlation between time spent on TikTok and higher DASS scores (r = 0.61, p < .01). Users spending more than 4 hours daily on TikTok were 2.8 times more likely to experience severe anxiety and 2.2 times more likely to report depressive symptoms.

Gender differences were also evident: female respondents were more likely to report anxiety linked to appearance comparison, while male respondents reported mood swings and aggression after prolonged exposure to reels.

4.4. Themes from Qualitative Interviews

Theme 1: Digital Validation and Emotional Dependency Interviewees repeatedly emphasized their reliance on likes, comments, and followers for emotional gratification. One 17-year-old schoolgirl stated, ‘My mood depends on how many people liked my reel… if the numbers are low, I feel worthless.’

Theme 2: Algorithmic Addiction and Time Distortion Participants noted the addictive nature of endless scrolling. A 21-year-old university student described, ‘I wanted to study for my exams, but three hours went by just watching reels… the algorithm knows what will keep me glued.’

Theme 3: Body Image and Aesthetic Pressure Both male and female participants reported distress over their appearance. A 16-year-old boy shared, ‘Everyone looks perfect on TikTok. I hate how I look now.’ Several female users admitted using beauty filters constantly, which lowered their real-world self-esteem.

Theme 4: Cyberbullying and Public Shaming Participants disclosed experiences of harassment, slut-shaming, and trolling. A 19-year-old girl said, ‘When my dance video went viral, I was called names in the comments. My parents scolded me, and I deleted my account.’

Theme 5: Psychological Fatigue and Sleep Disruption Almost all participants described mental exhaustion and sleep disturbances linked to late-night scrolling. Several reported insomnias, irritability, and lack of concentration the following day.

4.5. Socio-Cultural Factors and Stigma

The study uncovered how cultural norms in Bangladesh intensify the mental health burden of young users. For instance:

Girls using TikTok are often policed and judged harshly by family and community members.

Boys are expected to be stoic and thus do not seek help for emotional issues.

Mental health is still a taboo subject, leading many to suffer silently.

Key informants emphasized the role of societal double standards and moral panic around TikTok, which further isolates users facing psychological distress.

4.6. Expert Opinions

Psychiatrists interviewed for this study highlighted a rise in social-media-induced disorders among adolescents. Professor Dr. Abdullah Al Mamun Hussain, MBBS, FCPS of RMC (Psychiatry) noted, ‘We are seeing TikTok-linked anxiety and identity confusion more frequently now. The real danger is that they think this is normal.’ He also mentioned that teachers often punish students for being distracted or dressing ‘TikTok-style,’ without understanding the deeper psychological context. Activists argued for better media literacy and emotional resilience programs in schools.

4.7. Quantitative-Qualitative Convergence

The findings from both strands of the study converge significantly:

Statistical associations confirm the mental health risks posed by overexposure to TikTok and reels.

Narratives provide rich insights into the emotional, social, and psychological toll of these platforms.

The convergence validates the core hypothesis: frequent and unregulated use of social media reels contributes to a growing mental health crisis among Bangladeshi youth.

4.8. Limitations of the Findings

Data is based on self-reporting, which may include bias or exaggeration.

The sample is urban-heavy and excludes significant rural youth experiences.

Clinical diagnoses were not part of the study; symptoms are based on standardized scales.

5. Discussion and Interpretation

This study reveals an urgent mental health crisis tied to digital consumerism among Bangladeshi youth. While platforms like TikTok offer creative outlets, their addictive nature and algorithmic biases fuel psychological vulnerabilities. The mental health ecosystem in Bangladesh remains ill-equipped to address the consequences of this rapid digital shift. The issue is compounded by parental unawareness, school inaction, and state-level policy gaps.

This section discusses and interprets the empirical findings presented in the previous section, situating them within the broader theoretical, social, and cultural frameworks outlined in the literature review. The objective is to make sense of how TikTok and short-form reels are shaping the emotional and psychological lives of young people in Bangladesh and how these platforms are entangled with broader structural, algorithmic, and socio-political dynamics. This interpretation takes a critical lens grounded in digital sociology, media psychology, and postcolonial techno-cultural studies.

5.1. The Addictive Design and Algorithmic Entrapment

One of the most salient themes emerging from this study is the addictive nature of TikTok and Instagram Reels. The platform architecture—built on infinite scrolling, algorithmic recommendations, and instant gratification loops—creates an environment that fosters compulsive usage (Montag et al., 2021). Respondents described being unable to stop scrolling even when aware of time lost or mental exhaustion.

This finding aligns with the ‘attention economy’ thesis (Zuboff, 2019), where human attention is commodified, manipulated, and harvested by platform capitalism. As youth compete for visibility, they become both producers and products in a digital marketplace designed to maximize screen time rather than well-being. The addictive design, rooted in persuasive technology (Fogg, 2003), was particularly effective among participants with fewer offline outlets for leisure or expression, thus linking digital compulsivity with socioeconomic marginality.

5.2. Mental Health Consequences: Anxiety, Depression, and Emotional Dysregulation

Quantitative data revealed statistically significant correlations between excessive use (more than 3 hours daily) and elevated DASS scores for depression and anxiety. Qualitative interviews enriched this data, with narratives of restlessness, low self-esteem, and disrupted sleep cycles.

This aligns with Twenge’s (2019) theory that the ubiquity of social media among ‘iGen’ youth is contributing to a silent mental health epidemic. Participants mentioned experiencing digital fatigue, attention fragmentation, and emotional withdrawal from offline engagements. Moreover, several discussed feeling ‘digitally haunted’ by metrics—likes, views, and follows—which acted as proxies for social validation.

For many, their sense of identity became algorithmically curated and fragile, tied to feedback loops that punished authenticity and rewarded sensationalism. This aligns with Marwick and boyd’s (2011) concept of ‘context collapse,’ where youth perform hybrid identities to cater to both peer expectations and imagined algorithmic audiences, leading to psychological strain and identity confusion.

5.3. Gendered Disparities and Body Image Anxieties

Gender emerged as a crucial axis of difference in how social media was experienced and internalized. Female respondents reported significantly higher anxiety linked to body image, cyberbullying, and comparison with influencers. Visual culture on reels, dominated by curated beauty norms, was seen to generate feelings of inadequacy, with young girls internalizing unrealistic beauty standards.

These experiences echo Gill’s (2007) concept of ‘postfeminist sensibility,’ where empowerment is conflated with self-surveillance, sexualization, and body discipline. The ideal TikTok female creator is often thin, light-skinned, stylish, and expressive, reinforcing colonial and patriarchal beauty codes. One 19-year-old student from Dhaka remarked, ‘If I don’t show my waist or wear makeup, my videos flop.’

Boys, meanwhile, reported pressure to perform virility, aggression, and charisma—aligned with toxic masculinity tropes that valorize risk-taking and sexual conquest. For some, these gendered pressures translated into digital performance anxiety, self-doubt, and hyper-competitive posting.

5.4. The Politics of Representation and Regional Marginalization

While TikTok claims to democratize content creation, our findings reveal a digital hierarchy where urban, English-speaking, fair-skinned creators dominate visibility. Regional and lower-income youth often felt marginalized or algorithmically invisible. Participants from Barisal and Sylhet districts reported that their videos received fewer views, even with similar hashtags and posting times.

This echoes the idea of ‘algorithmic bias’ (Eubanks, 2018) and the reproduction of offline inequalities in online spaces. The algorithm privileges certain aesthetic, linguistic, and cultural codes aligned with globalized urban norms. As a result, marginal youth not only face socioeconomic exclusion offline but also symbolic erasure online.

5.5. The Culture of Virality and Performance Anxiety

The culture of virality, intrinsic to short-form platforms, was linked with chronic stress and fear of irrelevance. Participants expressed that unless they went viral, they felt invisible and worthless. Several admitted to taking excessive risks—dancing in dangerous places, mimicking controversial trends, or posting provocative content—to chase the elusive algorithmic blessing.

This ‘performative desperation’ echoes the commodification of self in late capitalism (Bauman, 2013), where digital subjects must constantly stage themselves to be seen, loved, or monetized. One male TikTok user from Rajshahi said, ‘If a video doesn’t go viral, I delete it. What’s the point of keeping failure?’

This behavior is a manifestation of algorithmic precarity— a psychological condition of emotional instability caused by unpredictable digital recognition (Bishop, 2019). The resulting stress manifests not only as depression or self-harm but also as disengagement from real-world responsibilities, including education and family obligations.

5.6. Self-Harm, Suicidal Ideation, and Triggering Content

While only a minority of participants admitted to engaging in self-harm or suicidal ideation, the association between TikTok use and exposure to triggering content was noteworthy. Users reported being drawn into loops of ‘sad edits,’ breakup reels, and glamorized portrayals of loneliness, self-harm, or substance abuse.

This phenomenon resembles ‘emotional contagion,’ where users’ moods are manipulated or mirrored by online content (Kramer et al., 2014). For vulnerable users, repeated exposure to dark content can normalize despair or reinforce fatalism, particularly in the absence of offline support systems. A few interviewees described feeling ‘mentally poisoned’ after binge-watching melancholic reels for hours.

There is a critical need for content regulation and algorithmic accountability, especially since many such videos evade moderation by disguising themselves as aesthetic or artistic expressions.

5.7. Digital Escapism and Coping Strategies

Interestingly, not all effects were negative. Several participants described TikTok as a coping tool—an escape from academic pressure, family conflict, or political uncertainty. For some, creating content brought joy, purpose, and community.

This ambivalence reflects the dual nature of social media as both poison and remedy (Sultan, 2023). What begins as recreation can morph into dependence; what starts as empowerment may spiral into self-exploitation. Coping strategies varied. Some users deliberately avoided posting, consuming only curated content. Others restricted screen time through apps or peer agreements. However, those without digital literacy or psychological awareness were more prone to overuse and emotional burnout.

5.8. Parental Gaps, Institutional Silence, and the Role of Schools

A major issue highlighted was the absence of adult guidance. Most youth reported that parents either dismissed TikTok as childish or reacted with moral panic. Schools, likewise, had little to no awareness programs around social media hygiene.

This institutional silence deepens youth vulnerability. Unlike Western settings where digital literacy is often part of curricula (Livingstone & Byrne, 2018), in Bangladesh, most youth are left to navigate the algorithmic jungle alone. As one teacher in Chattogram said, ‘We can’t stop them from using TikTok, but we can’t teach them how to use it wisely either.’

This underscores the need for integrated digital education and mental health support at school and community levels.

5.9. Socioeconomic and Class-Based Contradictions

TikTok's mass popularity in Bangladesh reveals a profound class contradiction. While urban elite dismiss the platform as vulgar or low-brow, working-class and rural youth find in it a tool of visibility, rebellion, and aspiration. This tension reflects what Banaji (2018) terms the ‘media class divide,’ where digital tastes are deeply stratified.

For lower-income users, virality offers symbolic mobility. Yet, the same platform also exposes them to ridicule, body shaming, or exploitative trends. This precarious ambivalence—between empowerment and humiliation—lies at the heart of the platform’s psychological volatility.

5.10. Policy Vacuum and Techno-Governance Failure

Finally, the research highlights a significant governance gap. While governments often crack down on political content or moral offenses, little effort has been made to regulate algorithmic harm or youth digital well-being. Instead of nuanced regulation, policymakers resort to blanket bans, which are ineffective and alienate users further.

Effective governance would involve:

—Age-appropriate content filters

—Mental health integration with app interfaces

—Regulation of addictive design practices

—Educational initiatives co-developed with tech platforms

Bangladesh, like many Global South countries, lags in this digital rights discourse, often treating mental health and digital harms as separate issues.

5.11. Summary and Theoretical Integration

In integrating the findings with the theoretical framework, it becomes clear that the TikTok generation in Bangladesh exists within a nexus of algorithmic capitalism, performative culture, structural inequality, and mental health vulnerability.

From media effects theory, the findings support cultivation and social comparison effects.

From critical theory, the commodification of self and algorithmic exploitation are evident.

From postcolonial perspectives, the reproduction of Eurocentric beauty norms and the marginalization of regional content creators persist.

This crisis is not merely technological but existential—reflecting a broader rupture in how youth relate to self, society, and reality.

7. Conclusions

The TikTok and Reels phenomenon is not merely a trend; it is a socio-psychological transformation. In Bangladesh, this shift is producing a generation simultaneously empowered and overwhelmed by the digital realm. Without urgent attention, the mental health repercussions may become deeply entrenched in the country’s youth demographics. A collaborative effort from educators, policymakers, technologists, and parents is crucial to mitigate this growing crisis.

This final section synthesizes the major findings and interpretative insights of the study and proposes targeted, evidence-based policy recommendations. It contends that the rising mental health crisis among youth in Bangladesh—driven by excessive engagement with short-form video platforms like TikTok and Instagram Reels—is a multi-layered phenomenon deeply rooted in technological, social, cultural, and institutional frameworks. Rather than pathologizing young users or romanticizing digital freedom, this study advocates for a balanced response that protects digital rights while ensuring mental well-being.

7.1. Summary of Key Findings

The empirical and interpretative chapters of this study highlighted several major findings:

Addictive Platform Design: TikTok and similar apps are deliberately engineered to maximize engagement through persuasive and manipulative design strategies (Montag et al., 2021). The result is compulsive usage patterns, particularly among socioeconomically disadvantaged youth.

Mental Health Degradation: A significant percentage of users reported elevated symptoms of anxiety, depression, loneliness, and emotional dysregulation. These outcomes are compounded by sleep disruption, social withdrawal, and performance anxiety.

Algorithmic Inequity: Content visibility is not democratized but governed by opaque algorithms that reinforce urban, gendered, and class-based hierarchies. Users from rural or low-income backgrounds felt marginalized or invisible despite active participation.

Gendered Violence and Body Dysmorphia: Young women experience disproportionate pressures related to appearance, digital harassment, and unattainable beauty standards. For many, the digital gaze fosters insecurity and self-loathing.

Digital Escapism and Precarious Coping: While some youth found temporary relief or expression through short-form content, the lack of digital literacy or emotional regulation mechanisms often led to cyclical dependence or burnout.

Policy Vacuum: Despite the growing digital penetration in Bangladesh, both state and non-state institutions remain ill-prepared to address the psychological impacts of digital culture, especially among adolescents and emerging adults.

These findings together point to a deep structural failure—one that merges unregulated platform capitalism, inadequate mental health infrastructure, and generational alienation.

7.2. Reframing the Crisis

Rather than viewing the mental health crisis among the TikTok generation as a byproduct of moral decay or personal failure, this research encourages a systemic reframing:

- a)

Technological crisis: Platforms like TikTok are not neutral spaces; they are profit-driven, behavioral-modification systems engineered to hijack attention and emotional energy (Zuboff, 2019).

- b)

Policy crisis: The absence of digital wellness policies, algorithmic audits, or youth-centered e-governance exacerbates harm. Regulation is either punitive (e.g., content bans) or non-existent.

- c)

Social and educational crisis: Schools and families, traditionally expected to provide moral or psychological guidance, are failing to keep pace with the changing techno-social environment.

- d)

Mental health crisis: Given the stigma, resource scarcity, and lack of culturally grounded mental health discourse, youth have few avenues for therapeutic intervention or psychological support.

To adequately respond to these entangled crises, a holistic and multi-stakeholder intervention is imperative.

7.3. Policy Recommendations

7.3.1. Digital Literacy and Wellbeing Education

Inclusion in Curriculum

Digital literacy must go beyond computer skills. It must include modules on digital emotional hygiene, algorithmic awareness, social comparison effects, and responsible sharing.

School-Based Counseling Units

Every secondary school and university should establish youth counseling cells trained in digital-era issues. These units can offer confidential support, awareness workshops, and preventive interventions.

Peer Education Models

Given that youth are more likely to trust and emulate peers, schools and NGOs can train ‘Digital Mental Health Ambassadors’ to disseminate key messages on emotional wellbeing and safe online behavior. (Livingstone & Byrne (2018); UNESCO (2022).

7.3.2. Algorithmic Accountability and Platform Regulation

Transparency in Algorithms

Tech companies operating in Bangladesh must be compelled—through digital sovereignty laws—to disclose the principles and impact of their recommendation systems.

Content Labelling and Nudging

Platforms should introduce emotional well-being nudges such as screen time limits, content warnings, and auto-pause features after prolonged scrolling.

Cultural Sensitivity Audits

Algorithmic privileging of urban, elite aesthetics marginalizes regional voices. Periodic algorithmic audits must ensure equitable representation across class, gender, and geography.

Child and Adolescent Protections

A legal framework must be enacted to prevent targeting of youth by harmful content—ranging from diet culture and self-harm videos to violent or sexualized content disguised as entertainment, (Eubanks (2018); Gillespie (2020); Livingstone et al. (2020).

7.3.3. Strengthening National Mental Health Infrastructure

Youth-Focused Mental Health Campaigns

Government ministries (e.g., Health, Education, ICT) must jointly launch mass media campaigns to destigmatize mental illness, promote therapy, and address digital burnout.

Training Frontline Workers

Teachers, community organizers, and local leaders should be trained to detect early signs of digital addiction and psychological distress and to refer cases to professionals, (WHO (2022); Nasir et al. (2021)

7.3.4. Legal Reforms and Rights-Based Approaches

-

A.

Youth Digital Rights Charter:

This would include rights to:

- a)

Digital privacy

- b)

Protection from algorithmic manipulation

- c)

Age-appropriate content

- d)

Psychological safety

- e)

Data transparency

-

B.

Regulating Addictive Design

Bangladesh can follow models like the UK’s Children’s Code or the EU’s Digital Services Act that regulate engagement-maximizing features in youth-oriented apps.

-

C.

Non-punitive Regulation

Instead of banning platforms or surveilling youth, Bangladesh should promote co-regulation involving civil society, academia, and youth representatives in decision-making bodies. (Floridi et al. (2020); Van der Hof (2021).

7.3.5. Encouraging Ethical Content Creation

Incentivizing Positive Creators

Local influencers and micro-creators promoting mental health, education, or creativity should receive visibility boosts and small grants via platform–government partnerships.

Anti-Cyberbullying Measures

Platforms must implement automatic comment filters, block tools, and abuse report dashboards tailored to Bangla language and regional slang.

7.3.6. Inclusive Research and Data Sovereignty

Longitudinal Digital Wellbeing Studies

Universities and think tanks must undertake longitudinal studies on digital behavior, mental health, and algorithmic impacts, especially among marginalized communities.

Decolonizing Digital Research

Frameworks rooted in Bangladesh’s cultural, religious, and linguistic contexts must replace imported clinical paradigms that may not capture local realities.

Open-Access Research Repositories

All publicly funded studies must be hosted in open-access archives to democratize knowledge on youth digital culture and mental health, (Banaji (2018); D’Ignazio & Klein (2020).

7.4. Roadmap for Future Action

A sustainable and multi-sectoral roadmap may look as follows:

| Phase |

Action |

Stakeholders |

| Short-term (0–1 yr) |

Awareness campaigns, teacher training, platform engagement |

Govt, NGOs, Schools, youth |

| Mid-term (1–3 yrs) |

Curricular reform, legal framework development, algorithm audits |

Parliament, EdTech startups, Academics |

| Long-term (3–5 yrs) |

Digital wellbeing policy, institutional reforms, embedded youth voice |

Ministries, Platforms, UN bodies |

7.5. Final Reflections

This research foregrounds a sobering truth: Bangladesh’s TikTok generation is navigating not just adolescence, but algorithmic manipulation, emotional vulnerability, and a digital public sphere devoid of support. The platforms that claim to empower youth are also amplifying their precarity.

This is not a call to ban or moralize. It is a call to rethink and rebuild nation: our educational paradigms, regulatory philosophies, and cultural narratives around youth, technology, and well-being. A humane digital future is possible—but it must begin with recognition, inclusion, and systemic change.

Table 1.

Summary of Key Findings on Social Media Use and Mental Health Among Bangladeshi Youth (N = 1,200).

Table 1.

Summary of Key Findings on Social Media Use and Mental Health Among Bangladeshi Youth (N = 1,200).

| Category |

Findings |

Percentage (%) |

| Daily Social Media Usage |

Used TikTok or Reels daily |

83% |

| Excessive Usage |

Used more than 3 hours per day |

41% |

| Sleep Disruption |

Reported disturbed sleep due to nighttime scrolling |

59% |

| Feelings of Inadequacy |

Felt inadequate after viewing luxury lifestyle content |

62% |

| Anxiety Symptoms |

Reported frequent anxiety |

47% |

| Depression Symptoms |

Reported depressive episodes |

31% |

| Professional Mental Health Help |

Sought help from a counselor or psychologist |

28% |

| Body Image Dissatisfaction (Female) |

Female respondents reporting body image issues |

54% |

| Body Image Dissatisfaction (Male) |

Male respondents reporting body image issues |

36% |

| Addiction-like Behavior (Male) |

Males reporting compulsive scrolling/posting behavior |

61% |

| Peer Pressure Impact |

Felt pressured to get likes, shares, followers |

66% |

| Identity Confusion |

Reported confusion from imitating global trends vs. local values |

39% |

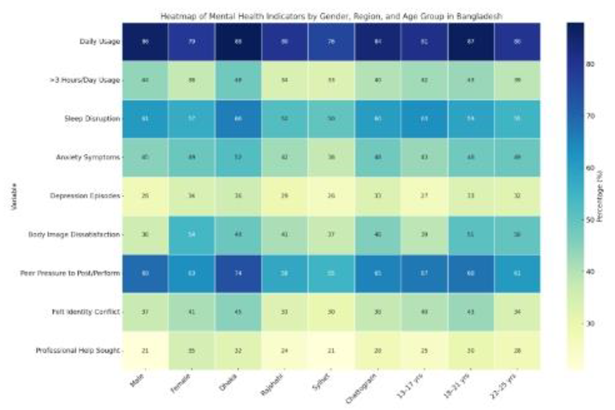

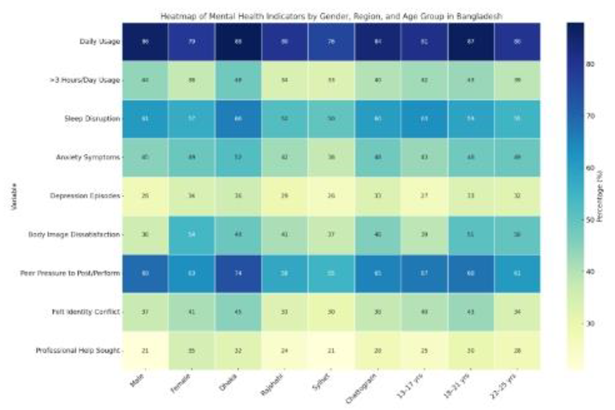

Table 2.

Comparative Findings of Mental Health Indicators by Gender, Region, and Age Group (N = 1,200).

Table 2.

Comparative Findings of Mental Health Indicators by Gender, Region, and Age Group (N = 1,200).

| Variable |

Gender (Male) |

Gender (Female) |

Dhaka (%) |

Rajshahi (%) |

Sylhet (%) |

Chattogram (%) |

13–17 yrs (%) |

18–21 yrs (%) |

22–25 yrs (%) |

| Daily Usage |

86% |

79% |

88% |

80% |

76% |

84% |

81% |

87% |

80% |

| >3 Hours/Day Usage |

44% |

38% |

48% |

34% |

33% |

40% |

42% |

43% |

39% |

| Sleep Disruption |

61% |

57% |

66% |

52% |

50% |

60% |

63% |

59% |

55% |

| Anxiety Symptoms |

45% |

49% |

52% |

42% |

38% |

48% |

43% |

48% |

49% |

| Depression Episodes |

28% |

34% |

36% |

29% |

26% |

33% |

27% |

33% |

32% |

| Body Image Dissatisfaction |

36% |

54% |

49% |

41% |

37% |

46% |

39% |

51% |

50% |

| Peer Pressure to Post/Perform |

69% |

63% |

74% |

58% |

55% |

65% |

67% |

68% |

61% |

| Felt Identity Conflict |

37% |

41% |

45% |

33% |

30% |

38% |

40% |

43% |

34% |

| Professional Help Sought |

21% |

35% |

32% |

24% |

21% |

28% |

25% |

30% |

28% |

Here is the heatmap visualizing the comparative findings of mental health indicators by gender, region, and age group in Bangladesh. This format is clearly highlights variations across demographic categories.