Introduction

Autonomic regulation in humans emerges from the dynamic interaction of multiple subsystems operating across different temporal and organizational scales. Traditional models have often described this regulation through linear, branch-based frameworks, emphasizing antagonistic balance between sympathetic and parasympathetic activity. While such approaches have contributed substantially to physiological understanding, they struggle to account for nonlinear dynamics, state transitions, and emergent patterns that characterize complex biological systems [

1,

2,

3].

Heart rate variability (HRV) has become a central observational window into autonomic regulation precisely because it reflects the integrated output of multiple regulatory processes rather than isolated neural pathways [

4,

5]. However, conventional interpretations of HRV frequently rely on single-domain metrics or simplified ratios, which may obscure the multiscale and context-dependent nature of autonomic organization [

6,

7,

8]. As a result, distinct physiological states can produce superficially similar HRV profiles, while meaningful transitions may remain undetected.

The Polyvagal Theory introduced an important evolutionary and functional perspective by emphasizing the hierarchical organization of vagal pathways and their role in adaptive behavior and social engagement [

9,

10,

11]. This framework highlighted the relevance of phylogeny, neuroanatomy, and context-sensitive regulation, expanding the conceptual landscape beyond simple autonomic balance. Nevertheless, its application has often remained focused on categorical interpretations or binary distinctions that do not fully capture the continuous and emergent properties of physiological regulation [

12,

13].

Recent advances in complexity science, nonlinear dynamics, and multiscale physiology suggest that autonomic regulation is better understood as a trajectory within a constrained state space rather than as oscillation around a fixed equilibrium [

3,

14,

15,

16]. Within this perspective, stability, flexibility, and adaptability arise from coordinated interactions across subsystems and temporal scales, giving rise to metastable configurations and state-dependent responses. Entropy-based and multiscale approaches have been particularly informative in revealing long-range organization and complexity loss in health and disease [

17,

18,

19].

The Expanded Polyvagal Theory (TPE) is presented in this manuscript as an interpretative and non-diagnostic theoretical framework designed to organize existing knowledge on autonomic regulation through a state-based and multiscale perspective. Although termed a “theory,” it does not propose new physiological mechanisms nor claim explanatory primacy over established models; rather, it functions as a conceptual framework grounded in complexity science, developmental biology, and entropy-oriented principles.

Rather than replacing existing physiological knowledge, the TPE seeks to synthesize evolutionary, developmental, and dynamical perspectives within a coherent framework compatible with complex systems theory [

3,

11,

16]. Its primary aim is to support structured interpretation of autonomic patterns, facilitate longitudinal analysis, and generate testable hypotheses regarding stability, adaptability, and dysregulation across diverse physiological and clinical contexts.

This manuscript is presented as a conceptual and hypothesis-generating preprint. Its primary purpose is to stimulate interdisciplinary discussion and theoretical refinement regarding autonomic regulation within a complex systems framework, rather than to report experimental findings or to propose diagnostic or clinical decision-making tools.

Scope and Conceptual Boundaries

The Expanded Polyvagal Theory (TPE) is proposed as an interpretative, non-diagnostic theoretical framework designed to organize existing knowledge on autonomic regulation through a state-based and multiscale perspective. It does not introduce new physiological mechanisms nor does it replace established models; instead, it offers a coherent interpretative scaffold grounded in complexity theory, developmental biology, and entropy-oriented principles [

3,

14,

15,

16]. Its scope is explicitly theoretical and interpretative, aiming to reorganize autonomic regulation in terms of emergent states, multiscale interactions, and developmental constraints. The framework does not introduce new physiological mechanisms, nor does it redefine established autonomic pathways. Instead, it provides a structured lens through which existing physiological knowledge can be coherently integrated and interpreted [

1,

2,

11].

A central boundary of the TPE concerns its non-diagnostic nature. General States and autonomic subtypes are not conceived as clinical categories, disease entities, or predictive labels. They represent abstract constructs inferred from convergent physiological patterns, particularly heart rate variability analyzed across multiple domains [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Consequently, the framework does not propose thresholds, cut-off values, or deterministic mappings between physiological signals and clinical outcomes. Any clinical relevance emerges indirectly, through hypothesis generation and longitudinal interpretation rather than categorical classification [

16,

19].

The TPE is also distinct from algorithmic or machine-learning approaches. Although it integrates information from diverse analytical domains, it does not operate as an automated classifier or optimization model. Interpretation within the framework depends on pattern convergence, contextual coherence, and temporal consistency, preserving the role of expert judgment and avoiding reduction of complex dynamics to single metrics or composite scores [

6,

14,

17].

Another defining boundary relates to the interpretation of heart rate variability. Within the TPE, HRV is understood as a projection of a high-dimensional regulatory system rather than a direct measure of isolated neural activity [

4,

5,

8]. Accordingly, associations between HRV patterns and specific autonomic subsystems are interpreted as signatures of coupling, constraint, or dominance, not as direct physiological measurements [

11,

12].

Finally, the Expanded Polyvagal Theory is intended to be open, adaptive, and empirically testable. Its constructs are expected to evolve as new data, modalities, and analytical techniques become available. The framework explicitly invites validation, refinement, and potential revision through longitudinal studies, perturbation-based designs, and multimodal integration [

14,

15,

16,

19]. Within these boundaries, the TPE aims to function as a flexible scaffold for organizing autonomic knowledge rather than as a closed or prescriptive theory.

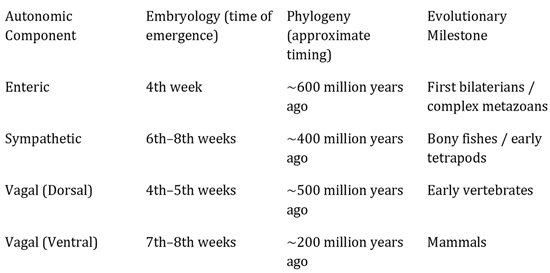

To facilitate a synthetic overview of the Expanded Polyvagal Theory,

Table 1 summarizes the embryological and phylogenetic emergence of its major autonomic components, integrating developmental timing, evolutionary hierarchy, and functional organization within a unified systems perspective [

9,

10,

11,

14]. This developmental mapping provides the structural foundation for the state-based organization proposed in the TPE, emphasizing that autonomic regulation emerges from temporally constrained and evolutionarily layered subsystems rather than from simultaneous or interchangeable components.

General States (GS): Emergent Autonomic Configurations

Within the Expanded Polyvagal Theory, General States are conceptualized as emergent and metastable configurations arising from the coordinated interaction of multiple autonomic subsystems, remaining sensitive to contextual modulation and perturbation. Rather than providing an explanatory or normative model of regulation, the framework offers an interpretative approach to autonomic organization, emphasizing relational patterns, state-space trajectories, and multiscale integration [

3,

14,

15,

16].

Transitions between states are understood as nonlinear processes, often marked by shifts in variability structure, entropy, and pattern coherence and not by simple changes in mean physiological values [

16,

17,

18]. This perspective aligns with contemporary views of biological regulation as a dynamic process governed by constraint, coupling, and multiscale integration.

In the TPE, General States emerge from the interaction of four structural autonomic subsystems: the enteric nervous system, vagal dorsal, vagal ventral, and sympathetic components. Each subsystem contributes distinct temporal signatures and functional constraints, and their coordinated activity gives rise to characteristic global configurations. Importantly, no single subsystem defines a General State in isolation; state identity arises from the relational pattern among subsystems rather than from dominance of any one branch [

9,

10,

11,

20].

Heart rate variability serves as a central observational window for inferring General States, particularly when analyzed through convergent multiscale approaches. Time-domain, frequency-domain, geometric, symbolic, and entropy-based measures each capture complementary aspects of autonomic organization, reflecting short-term responsiveness, oscillatory coupling, dispersion geometry, pattern diversity, and long-range complexity [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

17,

18,

19]. General State inference depends on coherence and consistency across these domains rather than on isolated metrics.

A defining feature of General States is their relevance to longitudinal interpretation. Changes in GS over time may reflect adaptation, recovery, deterioration, or compensatory reorganization, even when individual HRV metrics remain within conventional ranges. This state-based perspective allows for the identification of subtle transitions and early organizational shifts that may precede overt clinical manifestations [

14,

15,

16,

19].

Crucially, General States are interpretative constructs rather than diagnostic entities. They do not correspond to specific diseases, syndromes, or behavioral categories, nor do they imply fixed outcomes. Their value lies in organizing complex physiological information, supporting hypothesis generation, and guiding systems-oriented analysis of autonomic regulation across diverse contexts. By framing autonomic dynamics in terms of emergent states, the Expanded Polyvagal Theory provides a flexible and integrative scaffold for understanding physiological organization within a complex systems paradigm [

3,

11,

16].

Autonomic Subtypes: Structural–Functional Patterns Within General States

Autonomic subtypes within the Expanded Polyvagal Theory are defined as recurrent structural–functional patterns of subsystem coupling observed within a given General State. These subtypes do not represent fixed physiological entities or actionable categories; they function as interpretative motifs that help contextualize dominant or hybrid patterns of autonomic organization across multiple analytical domains; they represent mesoscopic organizational patterns that describe how enteric, vagal dorsal, vagal ventral, and sympathetic components interact within a given global configuration [

3,

9,

10,

11,

16].

Autonomic subtypes are defined relationally, based on the relative contribution, coordination, and constraint among subsystems. Primary subtypes correspond to configurations in which one subsystem exerts a dominant organizing influence, whereas hybrid subtypes reflect stable or semi-stable couplings between two subsystems. Importantly, dominance in this context does not imply exclusivity or suppression of other components, but a relative weighting within an integrated system [

11,

16,

20].

The identification of autonomic subtypes relies on convergent analysis of HRV features across multiple domains. Spectral composition, geometric dispersion, symbolic dynamics, and entropy profiles provide complementary information regarding oscillatory structure, pattern diversity, and long-range organization [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

17,

18,

19]. Subtype inference depends on coherence across these descriptors rather than on predefined thresholds or single-domain criteria.

Hybrid subtypes are of particular relevance within the Expanded Polyvagal Theory, as they capture adaptive or compensatory configurations that cannot be adequately described by binary sympathetic–parasympathetic models. For example, coupled vagal–enteric or vagal–sympathetic patterns may support context-dependent stability under metabolic, inflammatory, or psychosocial constraints [

9,

10,

11,

20]. These hybrid organizations highlight the flexibility of autonomic regulation and the importance of considering subsystem interactions rather than isolated branch activity.

Autonomic subtypes are inherently state-dependent and context-sensitive. The same subtype pattern may support adaptive function within one General State while reflecting constraint or reduced flexibility in another. Consequently, subtypes should not be interpreted as fixed traits, risk markers, or clinical labels. Their interpretative value emerges only when considered in relation to the overarching General State, temporal evolution, and environmental context [

3,

16].

By introducing autonomic subtypes as mesoscopic patterns within General States, the Expanded Polyvagal Theory bridges global state-level organization and fine-grained physiological descriptors. This intermediate level of description facilitates nuanced interpretation of autonomic dynamics, supports longitudinal tracking of organizational shifts, and provides a structured basis for integrating complex HRV patterns within a systems-oriented framework [

11,

14,

15,

16].

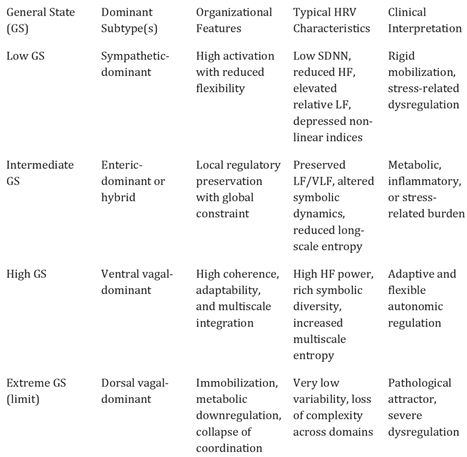

To provide a structured and synthetic overview of autonomic subtypes within the Expanded Polyvagal Theory,

Table 2 summarizes the primary and hybrid subtype patterns, their dominant subsystem couplings, and their characteristic heart rate variability features. This table is intended as an interpretative guide rather than a taxonomic classification, emphasizing state-dependence, organizational flexibility, and the non-diagnostic nature of subtype patterns [

3,

9,

10,

11,

16].

The Enteric Nervous System As a Structural Component of Autonomic Regulation

The enteric nervous system (ENS) constitutes a phylogenetically ancient and structurally autonomous neural network that precedes the differentiation of central sympathetic and parasympathetic pathways [

20,

21,

22]. Comprising extensive intrinsic circuitry capable of sensory processing, integration, and motor output, the ENS operates with a high degree of independence while remaining dynamically coupled to central autonomic regulation. Its early emergence in both phylogeny and ontogeny positions the ENS as a foundational component of autonomic organization rather than as a peripheral or secondary modulator.

Developmental and evolutionary evidence indicates that enteric circuits arise prior to the maturation of vagal and sympathetic control, establishing core regulatory patterns related to energy balance, nutrient processing, immune interaction, and visceral coordination [

20,

23,

24]. These functions impose fundamental constraints on later-developing autonomic subsystems, shaping the state space within which vagal and sympathetic dynamics subsequently operate. From this perspective, autonomic regulation cannot be fully understood without accounting for the organizing influence of enteric processes.

Functionally, the ENS participates in bidirectional communication with the central nervous system through multiple pathways, including vagal afferents, spinal connections, endocrine mediators, and immune signaling [

21,

25,

26]. These interactions contribute to the modulation of cardiovascular variability, metabolic regulation, inflammatory tone, and behavioral state. Importantly, enteric activity does not merely respond to central commands but actively participates in shaping global physiological organization through continuous feedback and constraint.

Within the Expanded Polyvagal Theory, the ENS is therefore incorporated as a structural autonomic subsystem, distinct from but interacting with vagal dorsal, vagal ventral, and sympathetic components. This inclusion extends traditional polyvagal models by explicitly acknowledging that autonomic states emerge from the coordinated activity of four interacting subsystems rather than from hierarchical vagal–sympathetic opposition alone [

9,

10,

11,

20]. The ENS contributes to state stability, energy availability, and long-range physiological coherence, particularly in contexts of chronic stress, inflammation, metabolic dysregulation, and multisystem disease.

Heart rate variability provides an indirect observational window into enteric–autonomic coupling, particularly through low-frequency dynamics and nonlinear measures that reflect long-range organization rather than short-term reflex activity [

4,

5,

17,

19]. Within the TPE, enteric influence on HRV is interpreted as a signature of coupling and constraint across subsystems, not as a direct measure of enteric neural firing. This distinction preserves physiological plausibility while allowing enteric contributions to be integrated into multiscale interpretative analysis.

By formally incorporating the enteric nervous system as a structural component of autonomic regulation, the Expanded Polyvagal Theory provides a more comprehensive and biologically grounded account of state-dependent physiological organization. This perspective aligns developmental biology, evolutionary neuroscience, and complexity theory, reinforcing the view that global autonomic states emerge from layered, interacting subsystems operating across multiple temporal and organizational scales [

14,

15,

16,

21].

The Osiris Protocol: An Integrative Framework for Autonomic Interpretation

The OSIRIS Protocol (Organic System for Integrated Rhythm Interpretation and Stratification) is introduced as an interpretative scaffold designed to operationalize the Expanded Polyvagal Theory through convergent analysis of heart rate variability. OSIRIS does not function as a diagnostic instrument, predictive algorithm, or clinical protocol; instead, it supports structured and context-sensitive interpretation of multiscale autonomic patterns within a complex systems perspective [

3,

14,

15,

16].

Conventional HRV analyses frequently rely on isolated metrics or single-domain interpretations, which may obscure nonlinear interactions and multiscale organization. OSIRIS addresses this limitation by explicitly prioritizing pattern convergence across domains, allowing meaning to emerge from coherence, redundancy, or divergence among descriptors rather than from any single parameter [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

17,

18,

19]. This approach aligns with complex systems theory, in which global states are inferred from coordinated patterns across interacting components rather than linear cause–effect relationships [

14,

15,

16].

Within the OSIRIS framework, HRV is analyzed across multiple complementary domains, including time-domain variability, frequency-domain structure, geometric descriptors, symbolic dynamics, and multiscale entropy. Each domain captures distinct aspects of autonomic organization across temporal scales, reflecting short-term responsiveness, oscillatory coupling, dispersion geometry, pattern diversity, and long-range complexity [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

17,

18,

19]. OSIRIS does not assign fixed weights to individual metrics; interpretative relevance arises from cross-domain consistency and contextual coherence.

A central objective of OSIRIS is to support the inference of General States and autonomic subtypes as emergent properties of global physiological organization. General State estimation focuses on identifying convergent signatures of stability, flexibility, and multiscale integration, whereas subtype interpretation emphasizes dominant subsystem couplings and mesoscopic patterning. These inferences are explicitly state-dependent and context-sensitive, preserving the dynamic nature of autonomic regulation [

3,

11,

16].

The protocol is particularly suited for longitudinal and comparative interpretation. Rather than producing absolute classifications, OSIRIS is designed to track changes in autonomic organization over time, across conditions, or in response to interventions. From a dynamical perspective, such trajectories within autonomic state space are often more informative than static snapshots, revealing adaptation, compensation, or loss of organizational complexity [

14,

15,

16,

19].

From an entropy-oriented standpoint, OSIRIS prioritizes the assessment of complexity preservation or degradation across scales. Multiscale entropy and symbolic dynamics play a central role in characterizing long-range organization and pattern richness, while spectral and geometric measures contextualize these findings within shorter temporal dynamics [

17,

18,

19]. This integrative perspective enables discrimination between HRV profiles that may appear similar under conventional metrics but differ fundamentally in organizational quality.

Crucially, OSIRIS is designed to preserve clinical judgment and contextual integration. Physiological signals are interpreted alongside clinical history, environmental conditions, and longitudinal evolution, avoiding deterministic mappings between numerical outputs and clinical decisions. In this sense, OSIRIS functions as a bridge between theoretical models of autonomic complexity and practical interpretative needs in research and clinical settings, without compromising the conceptual boundaries of the Expanded Polyvagal Theory [

3,

16].

Discussion and Limitations

The Expanded Polyvagal Theory (TPE) is proposed as a conceptual model intended to reorganize autonomic regulation within a complex systems perspective. By framing autonomic dynamics in terms of General States, mesoscopic autonomic subtypes, and convergent multiscale interpretation, the framework addresses limitations inherent to linear, branch-centered, or metric-isolated approaches to heart rate variability [

3,

14,

15,

16]. However, as with any integrative theoretical proposal, its assumptions, scope, and limitations must be explicitly acknowledged.

A central strength of the TPE lies in its state-based formulation. Conceptualizing autonomic regulation as a trajectory within a constrained state space allows the model to capture emergent properties, nonlinear transitions, and metastable configurations that are difficult to reconcile with traditional dichotomous interpretations [

14,

15,

16]. This perspective aligns with contemporary views of physiological regulation as adaptive and context-dependent rather than as oscillation around a fixed equilibrium. Nevertheless, state-based models inherently require interpretative discipline, as increased integrative power may also increase the risk of overgeneralization if constructs are reified or applied without adequate contextual grounding.

An important limitation concerns the inferential nature of General States and autonomic subtypes. These constructs are not directly observable physiological entities but interpretative abstractions inferred from convergent patterns across HRV domains [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

17,

18,

19]. Their validity depends on coherence across analytical domains, stability over time, and consistency with contextual and longitudinal information. Treating General States or subtypes as deterministic categories, diagnostic labels, or fixed traits would contradict the systems-oriented rationale of the framework [

3,

16].

The explicit incorporation of the enteric nervous system as a structural component represents a conceptual expansion with strong developmental and biological plausibility [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. However, the quantitative characterization of enteric contributions to global autonomic organization remains indirect. HRV-based inference of enteric influence—particularly through low-frequency and nonlinear measures—should be interpreted as signatures of coupling and constraint rather than as direct measures of enteric neural activity [

4,

5,

17,

19]. Multimodal empirical approaches integrating gastrointestinal, metabolic, immune, and neural signals will be required to refine and validate these associations.

Another limitation relates to the reliance on heart rate variability as a central observational window. While HRV provides a uniquely accessible and integrative signal, it represents only one projection of a high-dimensional regulatory system. Factors such as respiration, physical activity, circadian rhythms, pharmacological influences, and signal quality may substantially affect HRV patterns and must be carefully controlled or contextualized [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. The TPE does not claim that HRV alone is sufficient for comprehensive autonomic assessment, but rather that it offers a practical and informative entry point for systems-level interpretation [

16,

19].

The OSIRIS Protocol further illustrates both the strengths and constraints of integrative interpretation. By emphasizing pattern convergence across analytical domains, OSIRIS mitigates the limitations of single-metric inference. At the same time, its interpretative nature requires methodological transparency, expertise, and consistency to ensure reproducibility. Variability in preprocessing choices, analytical parameters, or contextual interpretation may lead to differences in inferred General States or subtype patterns, underscoring the need for explicit reporting standards in future applications [

14,

15,

16].

From an epistemological standpoint, the Expanded Polyvagal Theory is explicitly hypothesis-generating rather than predictive or diagnostic. It does not propose thresholds, cut-off values, or deterministic mappings between physiological patterns and clinical outcomes. Its primary contribution lies in structuring complex physiological information, guiding longitudinal observation, and generating testable hypotheses regarding stability, adaptability, and dysregulation in autonomic systems [

3,

11,

16]. Empirical validation of its constructs will require longitudinal designs, perturbation-based experiments, and multimodal data integration.

In summary, the Expanded Polyvagal Theory offers a coherent and biologically grounded approach to autonomic regulation within a complex systems paradigm. Its limitations—interpretative abstraction, reliance on indirect measures, and the need for empirical testing—are intrinsic to its conceptual ambition rather than weaknesses to be concealed. By explicitly acknowledging these boundaries, the framework positions itself as a flexible, transparent, and testable model capable of evolving alongside advances in physiological measurement and systems science [

14,

15,

16,

19].

Clinical and Translational Implications

The implications discussed in this section are conceptual and translational in nature. They are intended to illustrate how the Expanded Polyvagal Theory may inform theoretical interpretation and research design, and should not be construed as clinical recommendations, diagnostic criteria, or decision-support tools [

3,

14,

15,

16].

From a translational perspective, the framework offers a structured approach for interpreting heterogeneous autonomic findings that frequently coexist in clinical practice yet remain difficult to reconcile within linear or branch-based models. By framing autonomic regulation in terms of General States and state-dependent autonomic subtypes, the model supports longitudinal monitoring of physiological organization, identification of state transitions, and assessment of regulatory flexibility over time, even when conventional metrics remain within normative ranges [

16,

19].

The OSIRIS Protocol provides an operational bridge between theory and observation by enabling convergent interpretation of heart rate variability patterns across multiple analytical domains. This integrative approach allows clinicians and researchers to distinguish between superficially similar HRV profiles that differ in organizational quality, multiscale complexity, and stability, without reliance on fixed thresholds or deterministic mappings [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

17,

18,

19]. Such distinctions may be particularly informative in chronic stress-related conditions, inflammatory states, metabolic dysregulation, aging, and multisystem disease.

To illustrate this interpretative logic, consider a representative clinical vignette involving a patient with fatigue, gastrointestinal symptoms, and reduced cardiovascular variability. Conventional HRV analysis might suggest nonspecific autonomic imbalance. Within the Expanded Polyvagal Theory, convergent findings—such as reduced multiscale entropy, constrained symbolic dynamics, and altered low-frequency structure—may be interpreted as reflecting a stable enteric-dominant or hybrid autonomic configuration within a restricted General State. Importantly, this interpretation remains descriptive and contextual, supporting hypothesis generation and longitudinal tracking rather than categorical diagnosis [

11,

16].

More broadly, the translational relevance of the Expanded Polyvagal Theory lies in its capacity to guide research design and physiological interpretation rather than immediate clinical decision-making. By emphasizing patterns, trajectories, and state-space navigation, the framework aligns naturally with longitudinal studies, perturbation-based experiments, and multimodal data integration strategies. In this sense, its clinical value should be evaluated not by diagnostic performance, but by its ability to organize complex autonomic data, support testable hypotheses, and inform systems-oriented investigation of autonomic dynamics across health and disease [

14,

15,

16,

19].

Conclusions

The Expanded Polyvagal Theory proposes a systems-oriented reorganization of autonomic regulation grounded in complexity theory, developmental biology, and multiscale physiology. By conceptualizing autonomic dynamics in terms of General States, state-dependent autonomic subtypes, and convergent interpretation of heart rate variability, the framework moves beyond linear, branch-centered models toward an integrative representation of physiological organization [

3,

14,

15,

16].

A central contribution of the framework lies in its emphasis on emergence, state-space trajectories, and pattern convergence. Autonomic regulation is treated not as a static balance but as a dynamic process shaped by layered subsystems, contextual constraints, and temporal evolution. The explicit incorporation of the enteric nervous system as a structural component further strengthens the biological grounding of the model and aligns autonomic interpretation with developmental and evolutionary evidence [

9,

10,

11,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26].

The OSIRIS Protocol provides a transparent operational scaffold for applying these concepts to empirical data without reducing complexity to deterministic rules or diagnostic thresholds. By integrating complementary analytical domains and prioritizing longitudinal interpretation, OSIRIS enables structured exploration of autonomic organization while preserving clinical judgment and contextual awareness [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

17,

18,

19].

Importantly, the Expanded Polyvagal Theory is explicitly hypothesis-generating. Its constructs are intended to guide interpretation, organize complex information, and support the design of empirical studies rather than to replace established physiological measures or clinical decision-making. Future validation will depend on longitudinal designs, perturbation-based approaches, and multimodal integration capable of testing state transitions, stability, and adaptability across health and disease [

14,

15,

16,

19].

In summary, the Expanded Polyvagal Theory offers a coherent, flexible, and biologically grounded model for interpreting autonomic regulation within a complex systems paradigm. By articulating clear conceptual boundaries while remaining open to empirical refinement, the framework provides a robust platform for advancing systems-level understanding of autonomic dynamics and their relevance across physiological and clinical contexts.

References

- Goldberger, A.L.; Peng, C.K.; Lipsitz, L.A. What is physiologic complexity and how does it change with aging and disease? Neurobiol Aging 2002, 23, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipsitz, L.A. Physiological complexity, aging, and the path to frailty. Sci Aging Knowledge Environ. 2004, 2004, pe16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolis, G.; Prigogine, I. Self-Organization in Nonequilibrium Systems; Wiley: New York, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Heart rate variability: standards of measurement, physiological interpretation, and clinical use. Circulation 1996, 93, 1043–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, F.; Ginsberg, J.P. An overview of heart rate variability metrics and norms. Front Public Health 2017, 5, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Billman, G.E. The LF/HF ratio does not accurately measure cardiac sympatho-vagal balance. Front Physiol. 2013, 4, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassi, R.; Cerutti, S.; Lombardi, F.; Malik, M.; Huikuri, H.V.; Peng, C.K.; et al. Advances in heart rate variability signal analysis. Europace 2015, 17, 1341–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porges, S.W. The polyvagal theory: phylogenetic substrates of a social nervous system. Int J Psychophysiol. 2001, 42, 123–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porges, S.W. The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, and Self-Regulation. New York: W.W. Norton; 2011.

- Porges, S.W. Polyvagal theory: a science of safety. Front Integr Neurosci. 2022, 16, 871227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, P.; Taylor, E.W. Toward understanding respiratory sinus arrhythmia: relations to cardiac vagal tone, evolution and biobehavioral functions. Biol Psychol. 2007, 74, 263–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thayer, J.F.; Lane, R.D. A model of neurovisceral integration in emotion regulation and dysregulation. J Affect Disord. 2000, 61, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haken, H. Synergetics: An Introduction; Springer: Berlin, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Kelso, J.A.S. Dynamic Patterns: The Self-Organization of Brain and Behavior; MIT Press: Cambridge (MA), 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, M.; Goldberger, A.L.; Peng, C.K. Multiscale entropy analysis of complex physiologic time series. Phys Rev Lett. 2002, 89, 068102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.; Goldberger, A.L.; Peng, C.K. Multiscale entropy analysis of biological signals. Phys Rev E 2005, 71, 021906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porta, A.; Guzzetti, S.; Montano, N.; Furlan, R.; Pagani, M.; Malliani, A.; Cerutti, S. Entropy, entropy rate, and pattern classification as tools to typify complexity in short heart period variability series. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2001, 48, 1282–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershon, M.D. The enteric nervous system: a second brain. Hosp Pract. 1999, 34, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furness, J.B. The Enteric Nervous System; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, M.; Brookes, S.J.H.; Hennig, G.W. Anatomy and physiology of the enteric nervous system. Gut 2000, 47 (Suppl 4), iv15–iv19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, K.N.; Burns, A.J. Development of the enteric nervous system, smooth muscle and interstitial cells of Cajal in the vertebrate gastrointestinal tract. Cell Tissue Res. 2005, 319, 367–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obermayr, F.; Hotta, R.; Enomoto, H.; Young, H.M. Development and developmental disorders of the enteric nervous system. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013, 10, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, E.A. Gut feelings: the emerging biology of gut–brain communication. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011, 12, 453–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cryan, J.F.; Dinan, T.G. Mind-altering microorganisms: the impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012, 13, 701–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipsitz, L.A.; Goldberger, A.L. Loss of “complexity” and aging: potential applications of fractals and chaos theory to senescence. JAMA 1992, 267, 1806–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berntson, G.G.; Bigger, JTJr; Eckberg, D.L.; Grossman, P.; Kaufmann, P.G.; Malik, M.; et al. Heart rate variability: origins, methods, and interpretive caveats. Psychophysiology 1997, 34, 623–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Conceptual architecture and developmental timeline of the Expanded Polyvagal Theory.

Table 1.

Conceptual architecture and developmental timeline of the Expanded Polyvagal Theory.

Table 2.

Autonomic subtypes within the Expanded Polyvagal Theory: structural–functional patterns and characteristic HRV features.

Table 2.

Autonomic subtypes within the Expanded Polyvagal Theory: structural–functional patterns and characteristic HRV features.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).