Submitted:

15 August 2025

Posted:

19 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Metabolic–endocrine (bile acids / FXR–TGR5 / FGF19),

- Inflammatory–immune (cytokines / tryptophan–kynurenine metabolism),

- Microbiota–vagal (short-chain fatty acid production, vagal afferents).

1.1. Classical Neural Basis of Emotion

- Neglect of Peripheral Contributions – The CNS does not operate in isolation; gut-derived metabolites, liver-synthesized proteins, and immune signals modulate neural activity (Mayer et al., 2014).

- Overemphasis on Localized Brain Regions – Emotions arise from distributed networks, not isolated structures (Lindquist et al., 2012).

- Inadequate Explanation of Psychosomatic Links – Many mood disorders co-occur with metabolic and inflammatory conditions, suggesting systemic involvement (Felger & Lotrich, 2013).

1.2. Hepatic Modulation of Affective Oscillations: Neural, Circadian, and Inflammatory Pathways

1.3 The Liver’s Emerging Role in Affective Modulation

- Pathway III — Microbiota–vagal (SCFAs, α-diversity, HF-HRV)

1.4. Theory — NHAM formalism

- NHAM — Mathematical Formalism

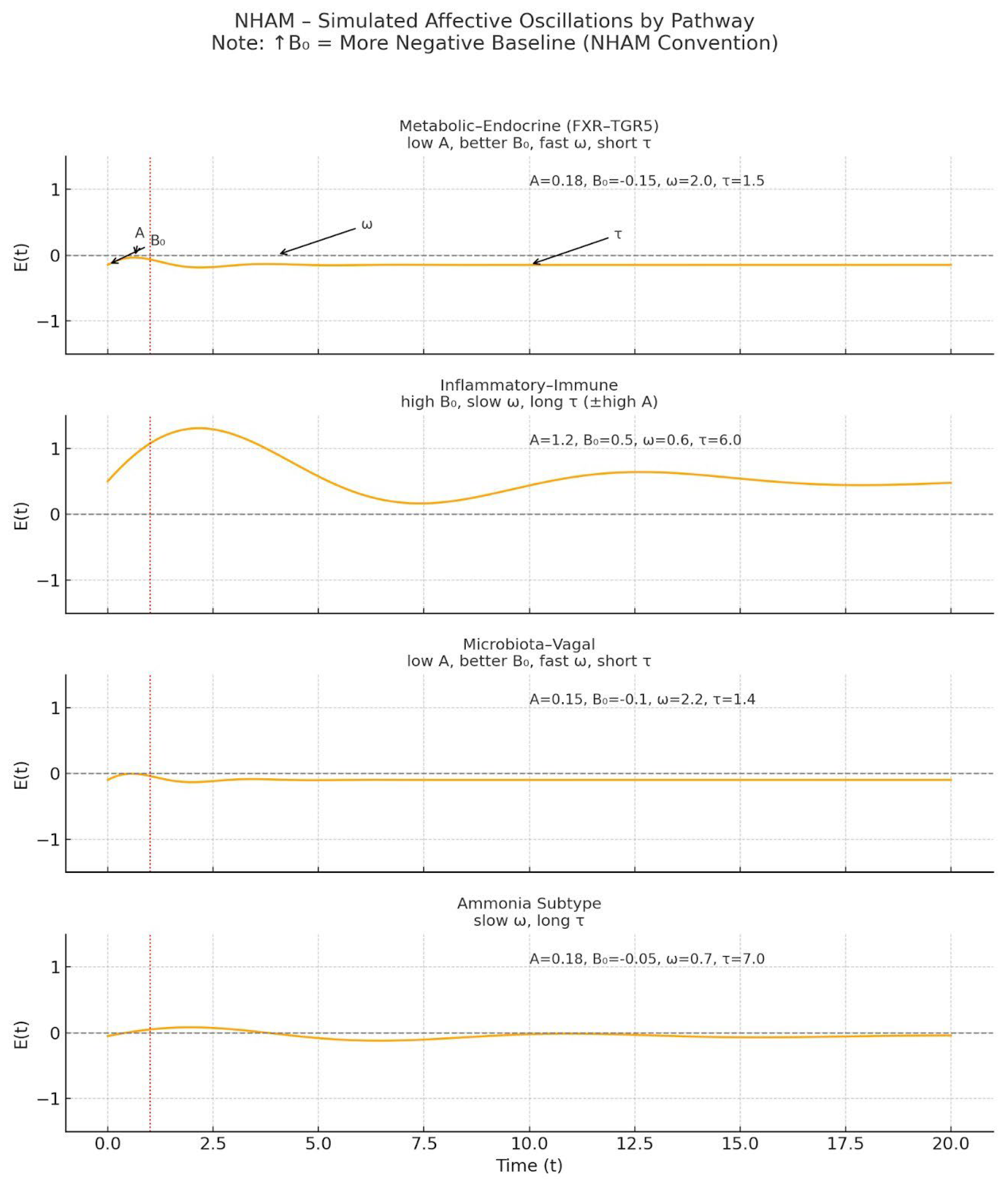

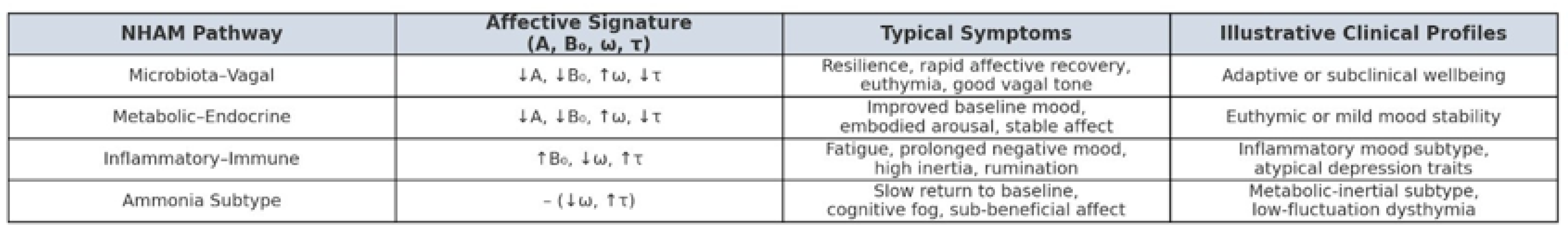

- Microbiota–Vagal (SCFAs, α-diversity, HRV) leads to ↓A, ↓B₀, ↑ω, ↓τ — a resilient affective signature.

- Metabolic–Endocrine (bile acids, FGF19, insulin) produces a similar beneficial pattern: ↓A, ↓B₀, ↑ω, ↓τ.

- Inflammatory–Immune (IL-6, CRP, Kyn/Trp) drives ↑B₀, ↑A, ↓ω, ↑τ — a high-persistence, high-reactivity affective state.

- Core dynamics

- State–space formulation

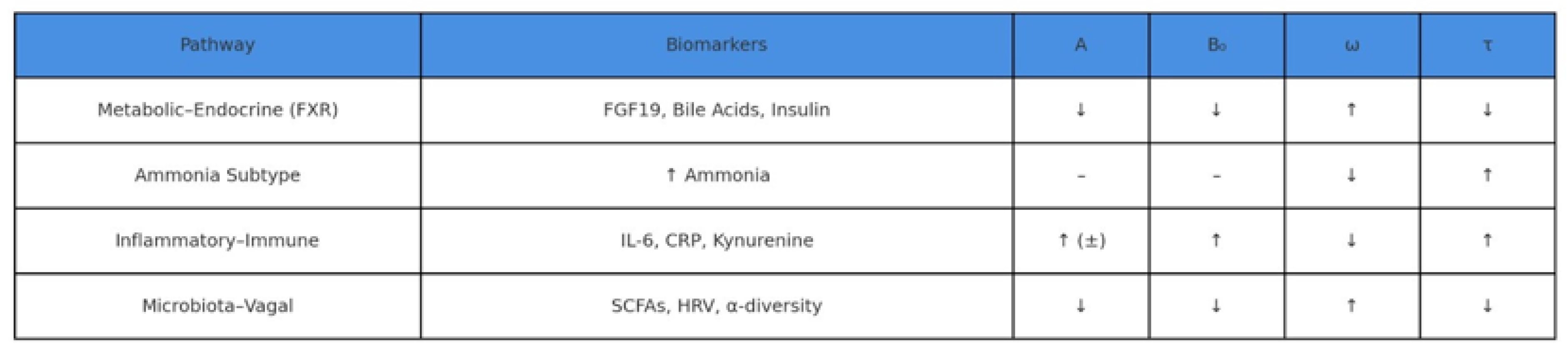

- Biomarker → parameter mapping

| Pathway | Primary biomarkers | Predicted parameter shifts | Functional impact |

| Metabolic–endocrine | Total bile acids, FGF19, HOMA-IR, ammonia |

↓A, ↓B₀, ↑ω, ↓τ; ammonia → ↓ω, ↑τ | Reduced reactivity, lower tonic negativity, faster updates (↑ω) & shorter persistence (↓τ); ammonia subtype: slower updates & longer persistence |

| Inflammatory–immune | IL-6, TNF-α, CRP, Kyn/Trp ratio, LPS/LBP |

↑B₀, ↓ω, ↑τ | Elevated baseline negativity, slower updates (↓ω) & prolonged recovery (↑τ) |

| Microbiota–vagal | SCFA levels, vagal tone (HF-HRV), diversity index |

↓A, ↓B₀, ↑ω, ↓τ | Lower reactivity, lower tonic negativity, faster recovery (↑ω) & shorter persistence (↓τ) — i.e., greater flexibility |

2. Definitions and Hypotheses (H1–H3)

- Amplitude (A) – intensity of transient affective responses.

- Baseline mood (B₀) – tonic affective set-point.

- Frequency (ω) – rate of oscillatory cycles (emotional adaptability).

- Persistence (τ) – temporal inertia of affective states.

- H1 – Metabolic–Endocrine Pathway:

- H2 – Inflammatory–Immune Pathway:

- H3 – Microbiota–Vagal Pathway:

3. Expected Results and Feasibility

- Autonomic indices (high-frequency HRV for vagal tone).

- Affective signal analysis from EDA and facial EMG.

- Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) for real-time emotional variability.

4. Clinical Implications and DSM/ICD Mapping

| DSM/ICD Diagnosis | NHAM Signature | Candidate Pathway | Suggested Intervention |

| Major Depressive Disorder | ↑B₀, ↑τ, ↓ω | Inflammatory–Immune | Anti-inflammatory modulation |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | ↑A, ↑B₀, ↑τ | Metabolic–Endocrine | Bile acid regulation |

| Irritable Bowel Syndrome | ↑A, ↑B₀, ↓ω | Microbiota–Vagal | SCFA and vagal tone enhancement |

| Chronic Fatigue Syndrome | ↑B₀, ↑τ, ↓ω | Ammonia-linked Metabolic | Ammonia clearance strategies |

5. Targeted Intervention Strategies

- Metabolic–Endocrine: FXR–TGR5 modulation, bile acid sequestration, insulin sensitivity improvement.

- Inflammatory–Immune: Cytokine-targeted therapy, gut permeability reduction, kynurenine pathway modulation.

- Microbiota–Vagal: SCFA supplementation, vagal nerve stimulation, microbiome diversity enhancement.

6. Research Priorities and Limitations

-

Longitudinal multi-omics cohortsProspective studies combining plasma bile acids, inflammatory markers, and microbiota metrics with psychophysiological parameters {A, B₀, ω, τ} are essential to assess parameter stability and transitions over time (Albillos et al., 2020; Nikkheslat et al., 2025). Such designs would clarify whether shifts in metabolic–endocrine, inflammatory–immune, or microbiota–vagal profiles precede affective changes.

-

Randomized controlled trials with oscillatory endpointsInterventional studies should test pathway-specific modulation—e.g., FXR/TGR5 agonists, probiotics, or anti-inflammatory agents—using {A, B₀, ω, τ} as mechanistic primary outcomes (Schaub et al., 2022; Dacaya et al., 2025). This approach aligns with the precision-medicine framework proposed in recent gastro-neuropsychiatric trials.

-

Computational modeling of network-wide affective shiftsBayesian state–space and oscillatory network models can simulate how pathway-specific perturbations propagate through affective dynamics (Tozzi & Peters, 2023). Integrating circadian gating and mood inertia (τ) into such simulations could identify optimal intervention timing.

-

Sex-specific analysesGiven documented sex differences in kynurenine metabolism and microbiota–vagal interactions (Nikkheslat et al., 2025), trials should be powered for sex-stratified analyses, with pre-specified interaction terms to detect differential pathway dynamics.

-

Closed-loop adaptive systemsWearable-enabled biofeedback integrating HRV, EDA, and biomarker readouts could trigger real-time intervention when parameter thresholds are breached (Wu et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2025). Such systems could be embedded within AI-driven digital twins for personalized simulation before clinical application.

- Limitations and Challenges

- Heterogeneity of affective phenotypes: Mixed presentations may not align with a single pathway, requiring weighted or composite signatures (Koenig et al., 2020).

- Evidence gaps: Pathway-to-parameter mapping remains largely cross-sectional; longitudinal causality is not yet established.

- Operational constraints: Multi-omics collection and continuous psychophysiological monitoring remain costly and logistically demanding outside specialized centers.

- Regulatory considerations: Closed-loop interventions will require robust safety validation and cross-disciplinary ethical oversight.

7. Discussion

7.1. Positioning within Existing Literature

7.2. Innovations and Conceptual Advances

- (i)

- Parameter-based interpretation. NHAM translates heterogeneous multi-omic and psychophysiological data into four interpretable parameters: amplitude (A), tonic baseline (B₀), update/recovery speed (ω), and persistence (τ).

- (ii)

- Phenotype-specific mapping. Patients are stratified into metabolic–endocrine, inflammatory–immune, microbiota–vagal, and autonomic phenotypes with defined biomarker profiles and directional parameter shifts (e.g., metabolic–endocrine → ↓A, ↓B₀, ↑ω, ↓τ; inflammatory–immune → ↑B₀, ↓ω, ↑τ; microbiota–vagal → ↓A, ↓B₀, ↑ω, ↓τ; low-HRV autonomic → ↓ω, ↑τ; ammonia subtype → ↓ω, ↑τ).

- (iii)

- Closed-loop potential. Combining wearable HRV, EMA, and lab panels enables continuous monitoring and adaptive interventions with parameter-level endpoints—analogous to feedback-controlled models in cardiology/endocrinology. (Operational thresholds—for example a drop in ω ≥ 20%—are heuristics pending prospective validation.) These thresholds are operational heuristics pending prospective validation.

- Topological and dynamical framing

- Clinical implications

- Challenges and caveats

8. Conclusions and Future Perspective

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

Availability of data and materials

Competing interests

Funding

Acknowledgements

Authors' contributions

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

References

- Albillos, A., de Gottardi, A., & Rescigno, M. (2020). The gut-liver axis in liver disease: Pathophysiological basis for therapy. Journal of Hepatology, 72(3), 558–577. [CrossRef]

- Albillos, A., Lario, M., & Álvarez-Mon, M. (2020). Cirrhosis-associated immune dysfunction: Distinctive features and clinical relevance. Journal of Hepatology, 73(6), 1549–1566. [CrossRef]

- Almulla, A. F., Supasitthumrong, T., Tunvirachaisakul, C., & Maes, M. (2022). The tryptophan catabolite or kynurenine pathway in major depressive and bipolar disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry, 112, 110405. [CrossRef]

- Almulla, A. F., Supasitthumrong, T., Tunvirachaisakul, C., Mukda, S., & Polyakova, M. (2022). The kynurenine pathway in major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia: A meta-analysis of 101 studies. Journal of Affective Disorders, 306, 109–120. [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, J. S., Heuman, D. M., & Sanyal, A. J. (2014). Modulation of the metabiome by rifaximin in patients with cirrhosis and minimal hepatic encephalopathy. PLOS ONE, 9(2), e83242. [CrossRef]

- Banks, W. A., & Erickson, M. A. (2010). The blood-brain barrier and immune function and dysfunction. Neurobiology of Disease, 37(1), 26–32. [CrossRef]

- Barrett, L. F. (2017). How emotions are made: The secret life of the brain. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Barrett, L. F. (2017). The theory of constructed emotion: An active inference account of interoception and categorization. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 12(1), 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Bechara, A., Damasio, H., & Damasio, A. R. (2000). Emotion, decision making and the orbitofrontal cortex. Cerebral Cortex, 10(3), 295–307. [CrossRef]

- Berger, M., Gray, J. A., & Roth, B. L. (2009). The expanded biology of serotonin. Annual Review of Medicine, 60, 355–366. [CrossRef]

- Berthoud, H. R., Münzberg, H., & Morrison, C. D. (2017). Blaming the brain for obesity: Integration of hedonic and homeostatic mechanisms. Gastroenterology, 152(7), 1728–1738. [CrossRef]

- Boeckxstaens, G., Denon, W., & De Jonge, F. (2014). The gut-brain axis: Neuroimmune interactions in gastrointestinal disorders. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 11(8), 452–459. [CrossRef]

- Boeckxstaens, G. E., et al. (2014). Neuroimmune mechanisms in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Neurogastroenterology & Motility, 26(6), 807–819. [CrossRef]

- Bonaz, B., Bazin, T., & Pellissier, S. (2018). The vagus nerve at the interface of the microbiota–gut–brain axis. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 12, 49. [CrossRef]

- Bush, G., Luu, P., & Posner, M. I. (2000). Cognitive and emotional influences in anterior cingulate cortex. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 4(6), 215–222. [CrossRef]

- Butterworth, R. F. (2015). Hepatic encephalopathy in cirrhosis: Pathology and pathophysiology. Drugs, 75(Suppl 1), 17–21. [CrossRef]

- Cipriani, A., Furukawa, T. A., & Salanti, G. (2018). Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. The Lancet, 391(10128), 1357–1366. [CrossRef]

- Craig, A. D. (2009). How do you feel—now? The anterior insula and human awareness. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10(1), 59–70. [CrossRef]

- Cryan, J. F., & Dinan, T. G. (2012). Mind-altering microorganisms: The impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behaviour. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 13(10), 701–712. [CrossRef]

- Albillos, A., de Gottardi, A., & Rescigno, M. (2020). The gut-liver axis in liver disease: Pathophysiological basis for therapy. Journal of Hepatology, 72(3), 558–577. [CrossRef]

- Albillos, A., Lario, M., & Álvarez-Mon, M. (2020). Cirrhosis-associated immune dysfunction: Distinctive features and clinical relevance. Journal of Hepatology, 73(6), 1549–1566. [CrossRef]

- Almulla, A. F., Supasitthumrong, T., Tunvirachaisakul, C., & Maes, M. (2022). The tryptophan catabolite or kynurenine pathway in major depressive and bipolar disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry, 112, 110405. [CrossRef]

- Almulla, A. F., Supasitthumrong, T., Tunvirachaisakul, C., Mukda, S., & Polyakova, M. (2022). The kynurenine pathway in major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia: A meta-analysis of 101 studies. Journal of Affective Disorders, 306, 109–120. [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, J. S., Heuman, D. M., & Sanyal, A. J. (2014). Modulation of the metabiome by rifaximin in patients with cirrhosis and minimal hepatic encephalopathy. PLOS ONE, 9(2), e83242. [CrossRef]

- Banks, W. A., & Erickson, M. A. (2010). The blood-brain barrier and immune function and dysfunction. Neurobiology of Disease, 37(1), 26–32. [CrossRef]

- Barrett, L. F. (2017). How emotions are made: The secret life of the brain. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Barrett, L. F. (2017). The theory of constructed emotion: An active inference account of interoception and categorization. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 12(1), 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Bechara, A., Damasio, H., & Damasio, A. R. (2000). Emotion, decision making and the orbitofrontal cortex. Cerebral Cortex, 10(3), 295–307. [CrossRef]

- Berger, M., Gray, J. A., & Roth, B. L. (2009). The expanded biology of serotonin. Annual Review of Medicine, 60, 355–366. [CrossRef]

- Berthoud, H. R., Münzberg, H., & Morrison, C. D. (2017). Blaming the brain for obesity: Integration of hedonic and homeostatic mechanisms. Gastroenterology, 152(7), 1728–1738. [CrossRef]

- Boeckxstaens, G., Denon, W., & De Jonge, F. (2014). The gut-brain axis: Neuroimmune interactions in gastrointestinal disorders. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 11(8), 452–459. [CrossRef]

- Boeckxstaens, G. E., et al. (2014). Neuroimmune mechanisms in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Neurogastroenterology & Motility, 26(6), 807–819. [CrossRef]

- Bonaz, B., Bazin, T., & Pellissier, S. (2018). The vagus nerve at the interface of the microbiota–gut–brain axis. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 12, 49. [CrossRef]

- Bush, G., Luu, P., & Posner, M. I. (2000). Cognitive and emotional influences in anterior cingulate cortex. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 4(6), 215–222. [CrossRef]

- Butterworth, R. F. (2015). Hepatic encephalopathy in cirrhosis: Pathology and pathophysiology. Drugs, 75(Suppl 1), 17–21. [CrossRef]

- Cipriani, A., Furukawa, T. A., & Salanti, G. (2018). Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. The Lancet, 391(10128), 1357–1366. [CrossRef]

- Craig, A. D. (2009). How do you feel—now? The anterior insula and human awareness. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10(1), 59–70. [CrossRef]

- Cryan, J. F., & Dinan, T. G. (2012). Mind-altering microorganisms: The impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behaviour. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 13(10), 701–712. [CrossRef]

- Mukherji, A., Kobiita, A., Ye, T., & Chambon, P. (2015). Homeostasis in intestinal epithelium is orchestrated by the circadian clock and microbiota cues transduced by the nuclear receptor FXR. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(9), E1104–E1113.

- Nestler, E. J., & Carlezon, W. A. (2006). The mesolimbic dopamine reward circuit in depression. Biological Psychiatry, 59(12), 1151–1159. [CrossRef]

- Nikkheslat, N., Keevil, B. G., Keeling, E., Nasrallah, R., Dupont, C. M., Cattrell, A., … & Dantzer, R. (2025). Sex-specific alterations of the kynurenine pathway in adolescents with major depressive disorder: Longitudinal associations with prognosis. Biological Psychiatry, 97(4), 367–379. [CrossRef]

- Nikkheslat, N., Pariante, C. M., & Nettis, M. A. (2025). Sex-specific inflammation profiles in depression: From pathophysiology to precision medicine. Molecular Psychiatry, 30(1), 102–118.

- Nikkheslat, N., Williams, S., Taylor, R., & Pariante, C. M. (2025). Sex-specific kynurenine pathway abnormalities predict persistence of major depressive disorder. Translational Psychiatry, 15, 60.

- O’Mahony, S. M., Clarke, G., & Dinan, T. G. (2015). Early-life adversity and brain development: Is the microbiome a missing piece of the puzzle? Neuroscience, 342, 37–54.

- Osadchiy, V., Martin, C. R., & Mayer, E. A. (2019). The gut–brain axis and the microbiome: Mechanisms and clinical implications. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 17(2), 322–332. [CrossRef]

- Osimo, E. F., Baxter, L. J., Lewis, G., Jones, P. B., & Khandaker, G. M. (2020). Prevalence of low-grade inflammation in depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis of CRP studies. Psychological Medicine, 50(3), 394–403. [CrossRef]

- Pessoa, L. (2017). A network model of the emotional brain. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 21(5), 357–371. [CrossRef]

- Pessoa, L., & Adolphs, R. (2010). Emotion processing and the amygdala: From a ‘low road’ to ‘many roads’ of evaluating biological significance. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 11(11), 773–783. [CrossRef]

- Romero-Ramírez, L., & Mey, J. (2024). Bile acid signaling in the central nervous system: Emerging therapeutic implications. Progress in Neurobiology, 224, 102438.

- Romero-Ramírez, L., & Mey, J. (2024). Emerging roles of bile acids and TGR5 in the central nervous system: Molecular functions and therapeutic implications. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 25(17), 9279. [CrossRef]

- Schaub, A. C., Schneider, E., & Holzer, P. (2022). Probiotics for major depressive disorder: Effects on microbiota composition, symptoms, and neural activity. Psychological Medicine, 52(8), 1445–1455.

- Schaub, A. C., Schneider, E., Vazquez-Castellanos, J. F., Schweinfurth, N., Kettner, M., Usbeck, J. C., … & Wirth, S. (2022). Clinical, gut microbial and neural effects of a probiotic add-on in depression: A randomized controlled trial. Translational Psychiatry, 12, 227.

- Shaffer, F., & Ginsberg, J. P. (2017). An overview of heart rate variability metrics and norms. Frontiers in Public Health, 5, 258. [CrossRef]

- Tkemaladze, J. (2023). Reduction, proliferation, and differentiation defects of stem cells over time: A consequence of selective accumulation of old centrioles in the stem cells? Molecular Biology Reports, 50(3), 2751–2761.

- Tkemaladze, J. (2024). Editorial: Molecular mechanism of ageing and therapeutic advances through targeting glycative and oxidative stress. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 14, 1324446. [CrossRef]

- Tozzi, A., & Peters, J. F. (2023). Towards a single parameter for the assessment of oscillations. Cognitive Neurodynamics, 18(3), 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Tsurugizawa, T., Tamura, R., & Kobayashi, M. (2025). Oscillatory brain dynamics underlying affective face processing. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 20(1), nsaf047. [CrossRef]

- Valkanova, V., Ebmeier, K. P., & Allan, C. L. (2013). CRP, IL-6 and depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Journal of Affective Disorders, 150(3), 736–744. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Chen, J., Li, X., & Zhou, X. (2025). Heart rate variability alterations in psychiatric disorders: An umbrella review of meta-analyses. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 164, 105404.

- Wang, Y., Shao, X., & Yan, C. (2025). Heart rate variability biofeedback for depression: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 167, 12–25. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Zhao, X., Zhang, Q., Wang, H., Liu, Q., & Zhang, J. (2025). Heart rate variability in mental disorders: An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 154, 105451.

- Wiest, R., Lawson, M., & Geuking, M. (2017). Pathological bacterial translocation in liver cirrhosis. Journal of Hepatology, 60(1), 197–209. [CrossRef]

- Woodie, L. N., Vettorazzi, J. F., Rouse, M., … & Wasserman, D. H. (2024). Hepatic vagal afferents convey clock-dependent signals to regulate circadian food intake. Cell Reports, 42(6), 112385.

- Wu, C., Zhang, L., & Liu, Y. (2023). Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation for major depressive disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 338, 21–32. [CrossRef]

- Wu, T., Wang, H., Yang, Y., Zhang, J., Li, Y., & Liu, Q. (2023). Heart rate variability status at rest in adult depressed patients: A meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research, 321, 115064. [CrossRef]

- Wu, T., Wang, H., Zhang, J., & Chen, S. (2023). Resting-state heart rate variability in major depressive disorder: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 165, 95–104. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y., Xu, L., & Zhou, H. (2023). The circadian clock and liver function in health and disease. Frontiers in Physiology, 14, 1187160.

- Yoo, B. B., & Mazmanian, S. K. (2017). The enteric network: Interactions between the immune and nervous systems of the gut. Immunity, 46(6), 910–926. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H., Xu, P., & Xu, Y. (2022). Hepatic inflammation and its impact on central nervous system functions. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 16, 858612. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).