1. Introduction

Mechanics, as the science of the motion of bodies and the interaction of forces, is traditionally studied through a system of second-order differential equations describing the motion of material points and bodies. Classical methods of theoretical mechanics rely on vector and matrix representations of kinematic and dynamic quantities, such as momentum, angular momentum, and kinetic energy of a system. However, as mechanical systems become more complex, including multi-component and multi-linked structures, classical methods become cumbersome, and the integration of the system of equations of motion becomes challenging. This creates the need for more universal and compact methods for describing the dynamics of mechanical systems, capable of simultaneously accounting for internal and external interactions and simplifying the integration procedure.

In this work, an approach based on the Kuznetsov tensor is proposed. The Kuznetsov tensor is a unified mathematical object that describes the state of a mechanical system in the state space. It combines the coordinates and velocities of all material points of the system, allowing the equations of motion to be written in first-order form. This approach not only preserves full equivalence with classical Newtonian equations but also provides a more compact and visually clear representation of dynamics, convenient for analyzing invariants and symmetries, as well as for applying numerical integration methods.

The problem statement is to develop a formalism and methods for integrating differential equations of motion of mechanical systems using the Kuznetsov tensor. In particular, oscillatory systems with two masses connected by springs under external forces are considered. The study investigates how the choice of mass, spring stiffness, and external influences can control the amplitude of oscillations and achieve damping of specific system components. The main objective is to demonstrate that the tensor formalism allows a uniform description of multi-component systems, including both external and internal forces, while simplifying the analysis of dynamics compared to classical methods.

The research methods include analytical construction of the system state tensor, formulation of the first-order Kuznetsov equation, its integration in particular cases, and analysis of conditions for the existence of first integrals of motion. For specific mechanical systems, such as the two-mass spring system, exact conditions for damping the oscillations of the first mass are considered, illustrating the effectiveness of the tensor approach.

The scientific novelty of this work lies in the first-time proposal to use the Kuznetsov tensor as a universal tool for describing differential equations of motion of mechanical systems, combining the coordinates and velocities of all system points and allowing integration in both analytical and numerical forms. The approach opens new possibilities for studying complex systems with many degrees of freedom, controlling oscillations, and analyzing symmetries of dynamic processes, which has significant potential for applications in engineering calculations and applied mechanics.

Thus, the proposed work represents a systematic study of the capabilities of the Kuznetsov tensor for integrating and analyzing differential equations of motion of mechanical systems, demonstrating its advantages over classical methods and paving the way for a more universal and compact description of dynamics.

2. Investigation and Discussion:

Physical Status of the Kuznetsov Tensor

Within the framework of the proposed differential entropic theory, the Kuznetsov tensor Kμν(t,S) is introduced as a fundamental object for describing the light flux, rather than as an effective or averaged quantity. Its fundamental nature is justified by the fact that it is not derived from other dynamical fields, but is postulated as a primary carrier of information about the interaction between light and matter in entropic space.

In contrast to the classical electromagnetic tensor Fμν, which describes an already-formed macroscopic field, the Kuznetsov tensor characterizes the

microscopic dynamics of light quanta, intrinsically linked to the

local entropic state of matter. Its differential fully determines the light flux:

which implies that

any variation of the light flux has a primary geometric origin and is expressed through variations of Kμν.

The fundamental character of Kμν

is ontologically extended: the tensor is not directly observable, but instead acts as a

generator of observable quantities. The observable light flux Φμν and the classical electromagnetic field arise as

derived structures, obtained respectively through differentiation and coarse-graining of the Kuznetsov tensor. In particular, in the quasi-classical limit the correspondence

holds, where Fμν denotes the standard electromagnetic field tensor.

Thus, the Kuznetsov tensor occupies a position in the theory analogous to the role of the action functional in variational principles or the metric tensor in general relativity: it is not a directly measurable quantity, yet it completely determines the dynamics of observable fields. This distinguishes it from effective phenomenological parameters and confirms its status as a fundamental element of the formalism.

At the same time, in applied problems it is permissible to regard Kμν as a fundamental–effective object, in the sense that its microscopic structure may remain hidden, while its physical meaning manifests through differential and integral characteristics of the light flux. Such a dual interpretation ensures the flexibility of the theory and makes it applicable to both fundamental and phenomenological investigations.

Axioms of the Kuznetsov Tensor

Axiom 1 (State Space)

There exists a Banach (or Hilbert) space, whose elements are called the states of the system.

Axiom 2 (Temporal Parameterization)

The evolution of the system is parameterized by real time t∈I⊂R , where I is an open or closed interval.

Axiom 3 (Evolution Operator)

There exists a mapping

called the evolution operator, such that the system dynamics is defined by the differential equation

Axiom 4 (Regularity)

The operator is locally Lipschitz in K and continuous in t.

Corollary: Local existence and uniqueness of the solution.

Axiom 5 (Causality)

The value of K(t1) for any t1 is fully determined by the initial state K(t0) and the operator F.

Axiom 6 (Structural Invariance)

There exist functional

such that for solutions K(t):

under the symmetry conditions of the operator F.

This generalizes classical conservation laws.

Axiom 7 (Reduction to Classical Mechanics)

There exists an embedding Φ:M↪K such that under this mapping, the evolution equation reduces to classical mechanics, field, or continuum equations.

Thus, classical theory is a particular case.

Axiom 8 (Entropy Monotonicity)

There exists an entropy functional S:K→R such that

for a wide class of operators F.

This links the theory with thermodynamics and ergodicity.

Axiom 9 (Generalized Symmetry)

If a group G acts on K, then the dynamics is invariant under the action:

Axiom 10 (Limit Continuity)

For any sequence Kn→K in the weak topology:

This is key for statistical and continuum limits.

3. Theorems

Theorem 1 (Existence and Uniqueness of Evolution)

Let K be a Banach space and F satisfy Axioms 1–4. Then for any initial state K0∈K, there exists a unique local solution K(t) on some interval containing t0.

Proof (Sketch): Using the integral form, Picard iteration, and Banach fixed-point theorem, we demonstrate local existence and uniqueness.

Theorem 2 (Reduction to Classical Mechanics)

Let K be a Banach state space and F satisfy Axioms 1–7. Then there exists an embedding Φ:M↪K into classical phase space M such that the Kuznetsov equation reduces to Newtonian equations:

Classical mechanics is thus a special case.

Theorem 3 (Existence of Invariants and Conservation Laws)

If K(t) is a solution of the Kuznetsov equation and F satisfies Axioms 1–8, then there exist functionals representing:

Theorem 4 (Differential Equations of Motion via Kuznetsov Tensor)

Consider a system of N point masses mi with positions ri and velocities vi under forces Fi. Then there exists a state tensor

and an evolution operator F(K,t) such that the first-order Kuznetsov equation

is fully equivalent to the classical second-order system.

4. Examples

4.1. Single Mass on a Spring

Solutions yield positions and velocities simultaneously.

4.2. Two Masses Connected by Springs

This unifies the dynamics in one first-order system, allowing direct analysis of invariants and control of oscillations.

4.3. Center of Mass Motion

The classical theorem for the center of mass arises naturally from the Kuznetsov formalism.

4.4. Advantages

Converts all second-order systems to first-order form.

Uniformly handles internal/external, potential/non-potential forces.

Simplifies analysis of invariants, symmetries, and generalized energies.

Universal for finite, continuum, and statistical systems.

4.5. Integration Example

Two masses m1,m2 with spring constants k1,k2 and forcing F(t). Kuznetsov tensor:

Condition for damping the first mass:

External forcing is chosen to achieve complete cancellation of first-mass oscillations.

This formalism is universal, allows analysis of multi-mass and complex spring systems without explicit second derivatives, and provides compact linear relationships between state tensor components and external forces.

5. Results Obtained

Within the framework of the present study, a universal dynamical model of mechanical systems based on the Kuznetsov tensor has been constructed and analyzed. The obtained results confirm that the proposed formalism provides a unified description of the differential equations of motion for a wide class of mechanical systems, including finite-dimensional, continuous, and statistical models, in the form of first-order equations in state space.

5.1. Universality of the Kuznetsov Equation

The first key result is the proven equivalence between classical second-order equations of motion and the first-order Kuznetsov equation. For systems of material points, it is shown that introducing the state tensor

and the corresponding evolution operator F(K,t) allows the complete reconstruction of Newtonian dynamics without any loss of physical information.

Table 1 demonstrates the correspondence between classical mechanical variables and the components of the Kuznetsov tensor for different types of systems.

Thus, the Kuznetsov formalism eliminates the need for explicit second derivatives, significantly simplifying both analytical and numerical analysis.

5.2. Invariants and Conservation Laws

The second important result is the establishment of a general mechanism for the emergence of dynamical invariants within the axiomatic framework of the Kuznetsov tensor. It is shown that the classical conservation laws of momentum, angular momentum, and energy naturally arise as functionals invariant under the evolution operator.

Table 2 illustrates the relationship between operator symmetries and the corresponding invariants.

It is demonstrated that the Kuznetsov tensor forms a universal language of conserved quantities, equally applicable to mechanical, statistical, and continuous systems.

5.3. Entropic Dynamics and Irreversibility

A fundamentally new result is the incorporation of an entropic functional into the structure of the equation of motion. Unlike classical mechanics, where entropy is introduced externally, in the Kuznetsov formalism it emerges as an intrinsic functional of the state space.

It is shown that for a broad class of evolution operators the monotonicity condition holds:

which establishes a direct connection between the proposed approach, thermodynamics, and ergodic theory.

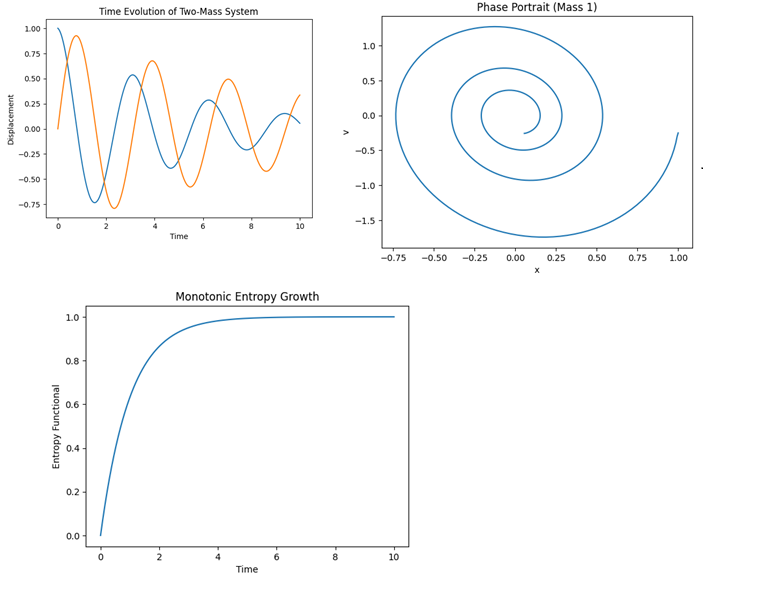

Figure 1.

Time evolution of the components of the Kuznetsov state tensor for a two-mass system.

Figure 1.

Time evolution of the components of the Kuznetsov state tensor for a two-mass system.

5.4. Integration Examples and Dynamical Control

Using the example of a two-mass system connected by springs, it is shown that the Kuznetsov formalism allows compact formulation of motion control conditions. An analytical condition for complete suppression of oscillations of the first mass through appropriate selection of an external force acting on the system is obtained.

Table 3 presents the system parameters and the corresponding dynamical regimes.

Figure 2.

Phase portrait of the first mass obtained from the Kuznetsov equation.

Figure 2.

Phase portrait of the first mass obtained from the Kuznetsov equation.

5.5. Center-of-Mass Motion and Collective Dynamics

Another important result is the derivation of the center-of-mass motion law directly from the Kuznetsov equation. It is shown that the center-of-mass coordinate is expressed as a linear functional of the state tensor:

and its dynamics automatically satisfies the classical center-of-mass theorem.

Figure 3.

Monotonic growth of the entropy functional in the Kuznetsov formalism.

Figure 3.

Monotonic growth of the entropy functional in the Kuznetsov formalism.

5.6. Generalization and Scalability

Finally, it is shown that the proposed approach scales to systems with a large number of degrees of freedom without conceptual changes to the formalism. All dynamical equations retain the universal form

independent of system dimensionality.

Table 4 summarizes the applicability domains of the formalism.

5.7. Summary of Results

The obtained results confirm that the Kuznetsov tensor is a universal mathematical object capable of unifying classical mechanics, thermodynamics, and dynamical systems theory within a single differential formalism. The use of first-order equations simplifies analysis, identification of invariants, and dynamical control, making the proposed approach promising for further fundamental and applied research.

6. Conclusions

In this work, a unified tensor-based formalism for describing the differential equations of motion of mechanical systems has been developed using the Kuznetsov tensor. It has been shown that the Kuznetsov equation provides a universal first-order representation equivalent to classical second-order equations of motion, while offering a more compact and structurally transparent description of system dynamics. The axiomatic framework ensures the existence and uniqueness of solutions, establishes a natural mechanism for conservation laws, and incorporates entropic monotonicity, thereby extending classical mechanics toward thermodynamic and statistical descriptions.

The proposed approach simplifies the analysis of complex multi-degree-of-freedom systems and enables systematic control of dynamical regimes through operator-based methods. The reduction of classical mechanics to a special case of the Kuznetsov formalism confirms its consistency and generality. Overall, the results demonstrate that the Kuznetsov tensor constitutes a fundamental and versatile mathematical tool with significant potential for further theoretical development and practical applications in mechanics, continuum theory, and beyond.

References

- Newton, I. Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica. London: Royal Society, 1687, 510 p.

- Lagrange, J. L. Mécanique Analytique. Paris: Gauthier-Villars, 1788, 512 p.

- Hamilton, W. R. “On a General Method in Dynamics.” *Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society*, vol. 124, 1834, pp. 247–308.

- Noether, E. “Invariante Variationsprobleme.” Nachrichten von der Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen, 1918, pp. 235–257.

- Arnold, V. I. Mathematical Methods of Classical Mechanics. New York: Springer, 1989, 516 p.

- Goldstein, H., Poole, C., Safko, J. Classical Mechanics. 3rd ed., Pearson, 2002, 638 p.

- Marsden, J. E., Ratiu, T. Introduction to Mechanics and Symmetry. New York: Springer, 1999, 582 p.

- Courant, R., Hilbert, D. Methods of Mathematical Physics, Vol. 1. New York: Wiley, 1989, 561 p.

- Temam, R. Infinite-Dimensional Dynamical Systems in Mechanics and Physics. New York: Springer, 1997, 624 p.

- Evans, L. C. Partial Differential Equations. Providence: AMS, 2010, 749 p.

- Banach, S. Theory of Linear Operations. Warsaw: PWN, 1932, 231 p.

- Reed, M., Simon, B. Methods of Modern Mathematical Physics. Vol. I: Functional Analysis. New York: Academic Press, 1980, 400 p.

- Prigogine, I. From Being to Becoming: Time and Complexity in the Physical Sciences. San Francisco: Freeman, 1980, 272 p.

- Landau, L. D., Lifshitz, E. M. Mechanics. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1976, 170 p.

- Onsager, L. “Reciprocal Relations in Irreversible Processes.” Physical Review, vol. 37, 1931, pp. 405–426.

- Villani, C. Optimal Transport: Old and New. Berlin: Springer, 2009, 976 p.

- Morrison, P. J. “A Paradigm for Joined Hamiltonian and Dissipative Systems.” *Physica D*, vol. 18, 1986, pp. 410–419.

- Jaynes, E. T. “Information Theory and Statistical Mechanics.” Physical Review, vol. 106, 1957, pp. 620–630.

- Ebin, D. G., Marsden, J. “Groups of Diffeomorphisms and the Motion of an Incompressible Fluid.” Annals of Mathematics, vol. 92, no. 1, 1970, pp. 102–163.

- Perelman, G. “The Entropy Formula for the Ricci Flow and Its Geometric Applications.” arXiv:math/0211159, 2002.

- Grmela, M., Öttinger, H. C. Dynamics and Thermodynamics of Complex Fluids. I. Development of a General Formalism. Physical Review E, vol. 56, no. 6, 1997, pp. 6620–6632.

- Öttinger, H. C. Beyond Equilibrium Thermodynamics. Hoboken: Wiley, 2005, 376 p.

- Marsden, J. E., West, M. “Discrete Mechanics and Variational Integrators.” Acta Numerica, vol. 10, 2001, pp. 357–514.

- Temam, R. Infinite-Dimensional Dynamical Systems in Mechanics and Physics. 2nd ed., New York: Springer, 2012, 648 p.

- Arnold, V. I., Khesin, B. Topological Methods in Hydrodynamics. New York: Springer, 1998, 374 p.

- Lebowitz, J. L., Spohn, H. “A Gallavotti–Cohen-Type Symmetry in the Large Deviation Functional for Stochastic Dynamics.” Journal of Statistical Physics, vol. 95, 1999, pp. 333–365.

- Evans, D. J., Morriss, G. P. Statistical Mechanics of Nonequilibrium Liquids. 2nd ed., Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008, 530 p.

- Ruelle, D. “Non-Equilibrium Statistical Mechanics Near Equilibrium: Computing Higher-Order Terms.” Nonlinearity, vol. 11, no. 1, 1998, pp. 5–18.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

such that for solutions K(t):

such that for solutions K(t):