Submitted:

18 December 2025

Posted:

22 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Research Status

2.1. Existing Issues

2.2. Proposed Solution

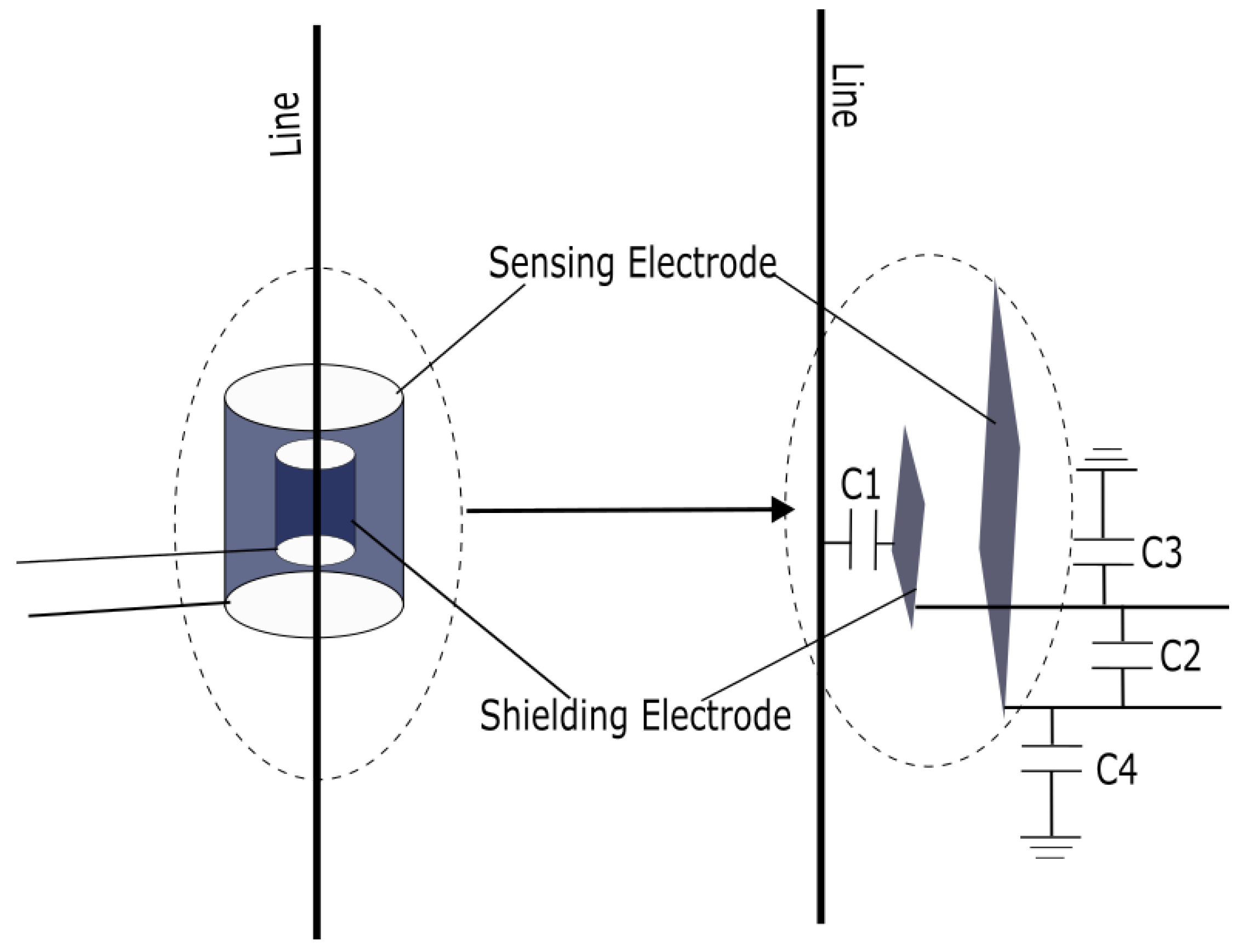

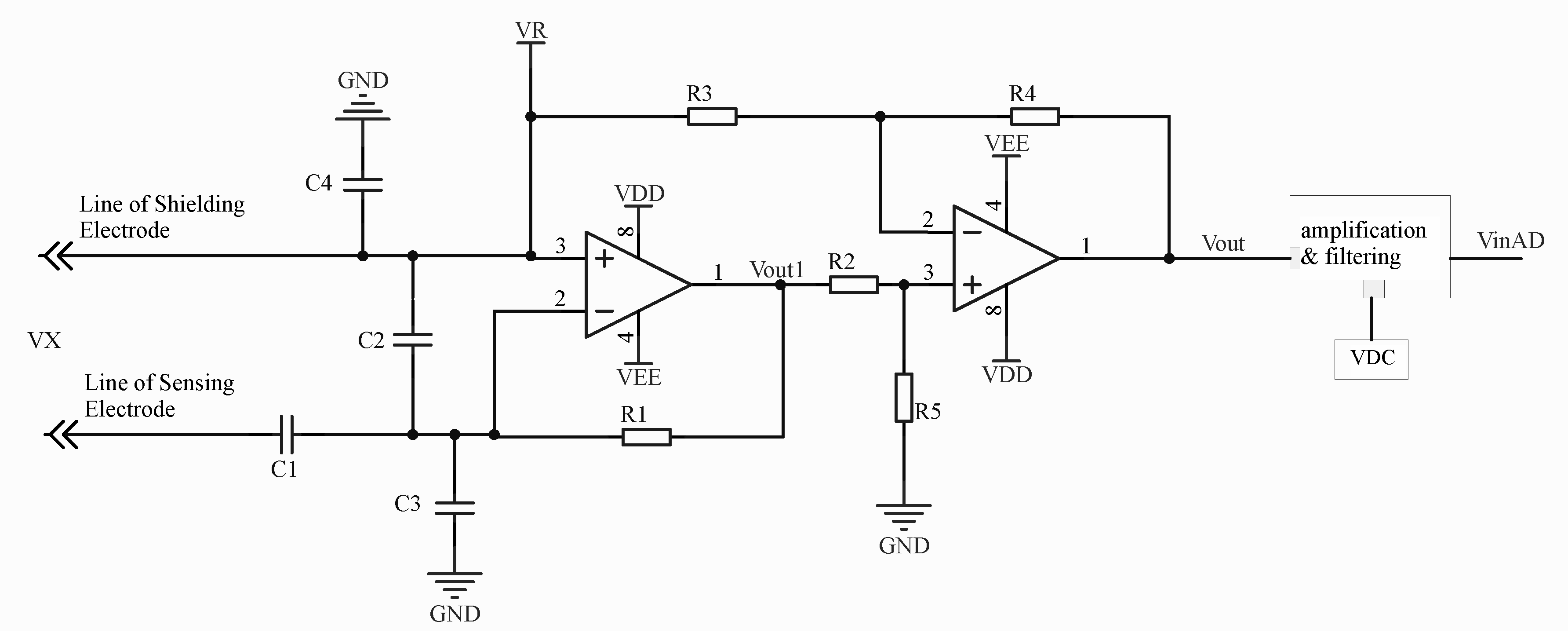

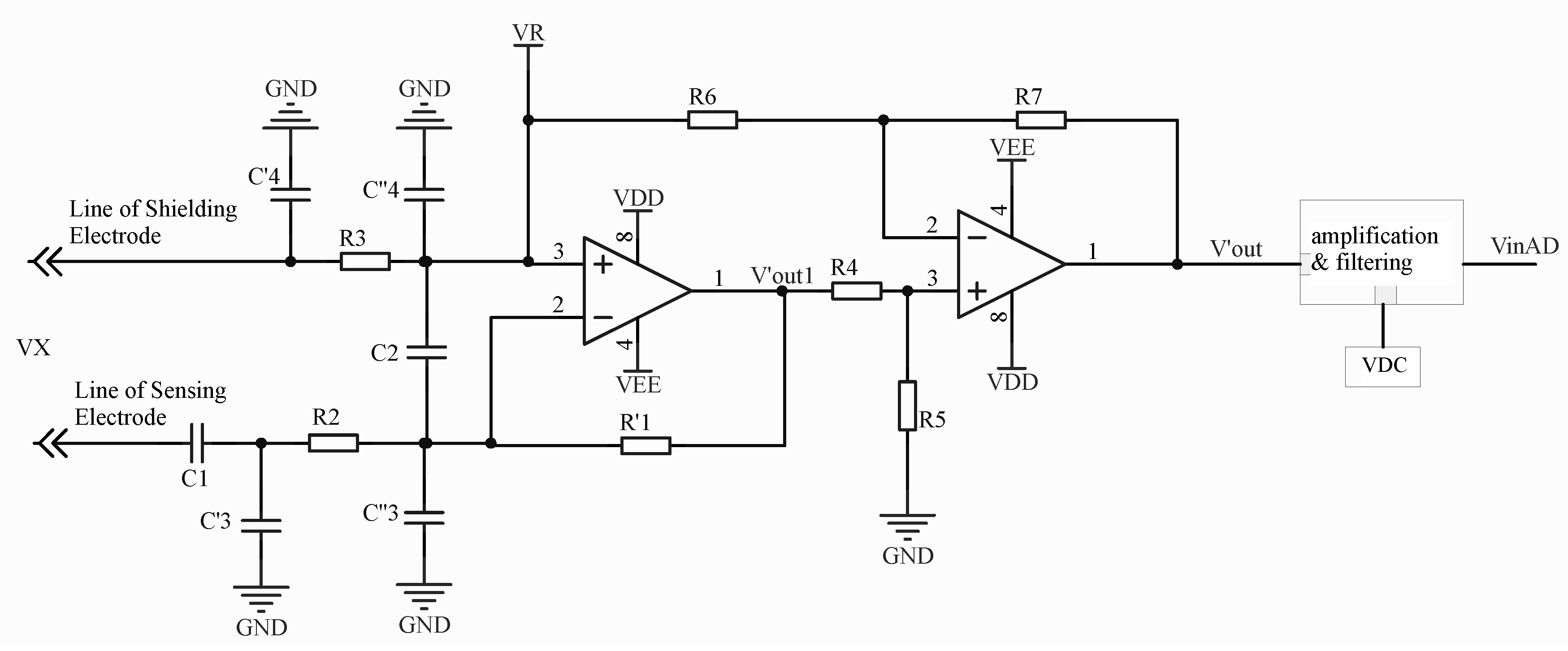

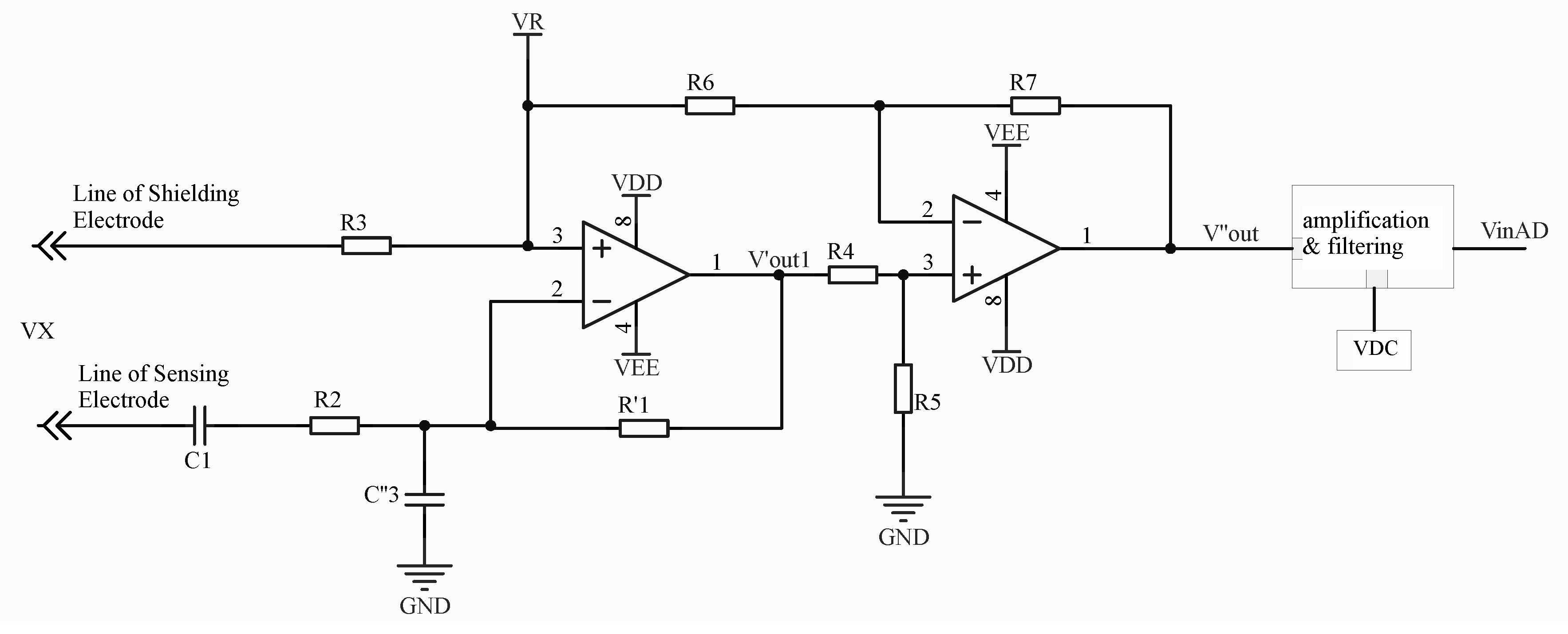

3. Circuit Principles

3.1. Resistive-Capacitive Signal Input Circuit

4. Data Processing Methods

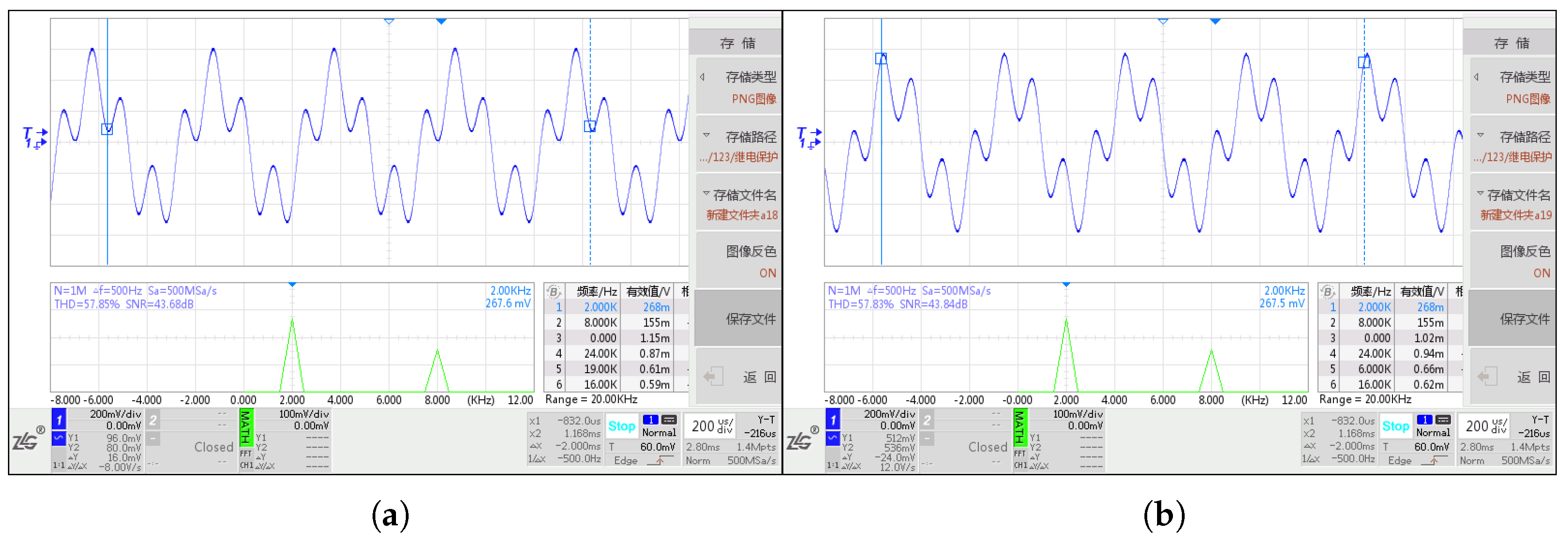

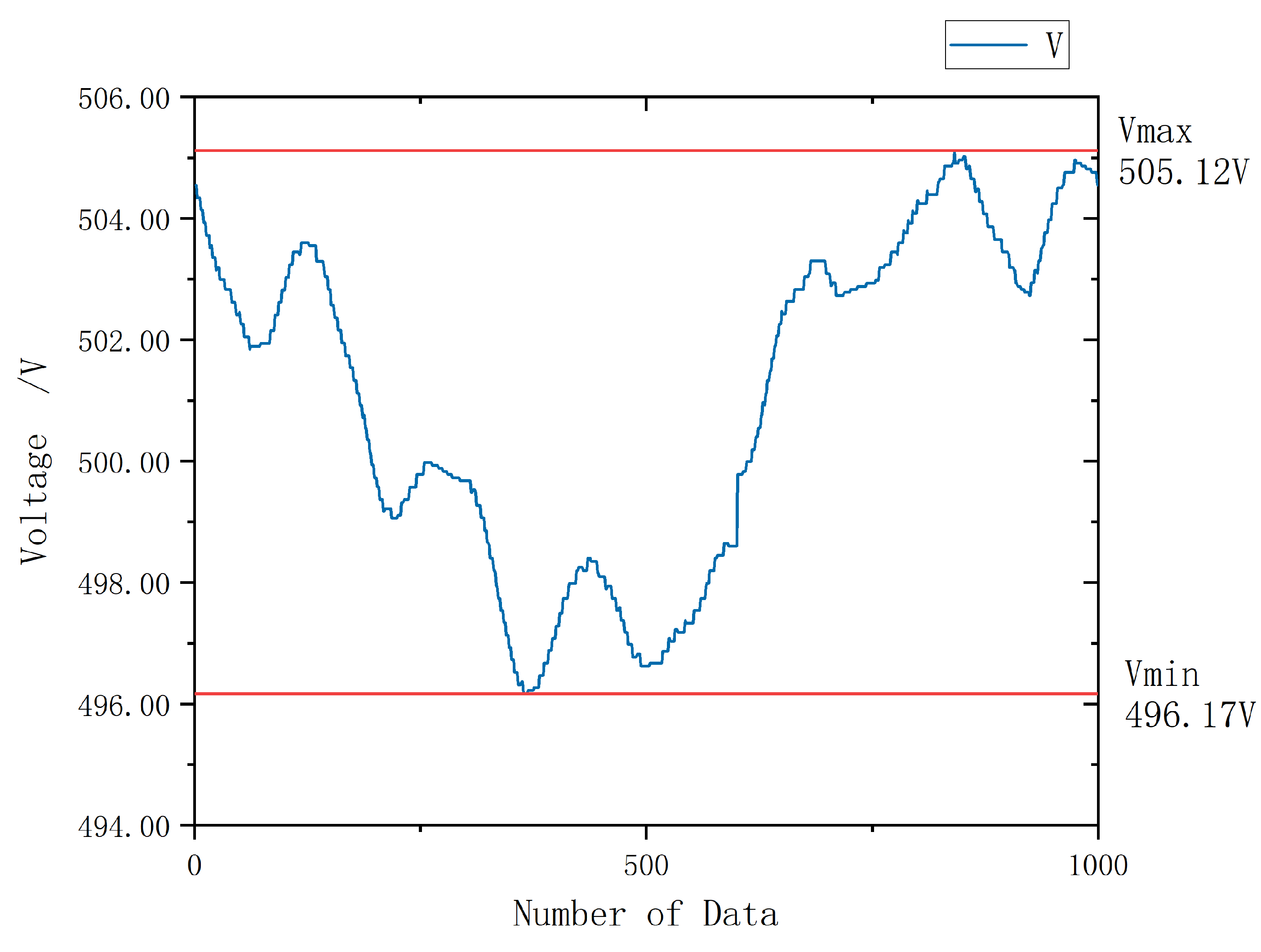

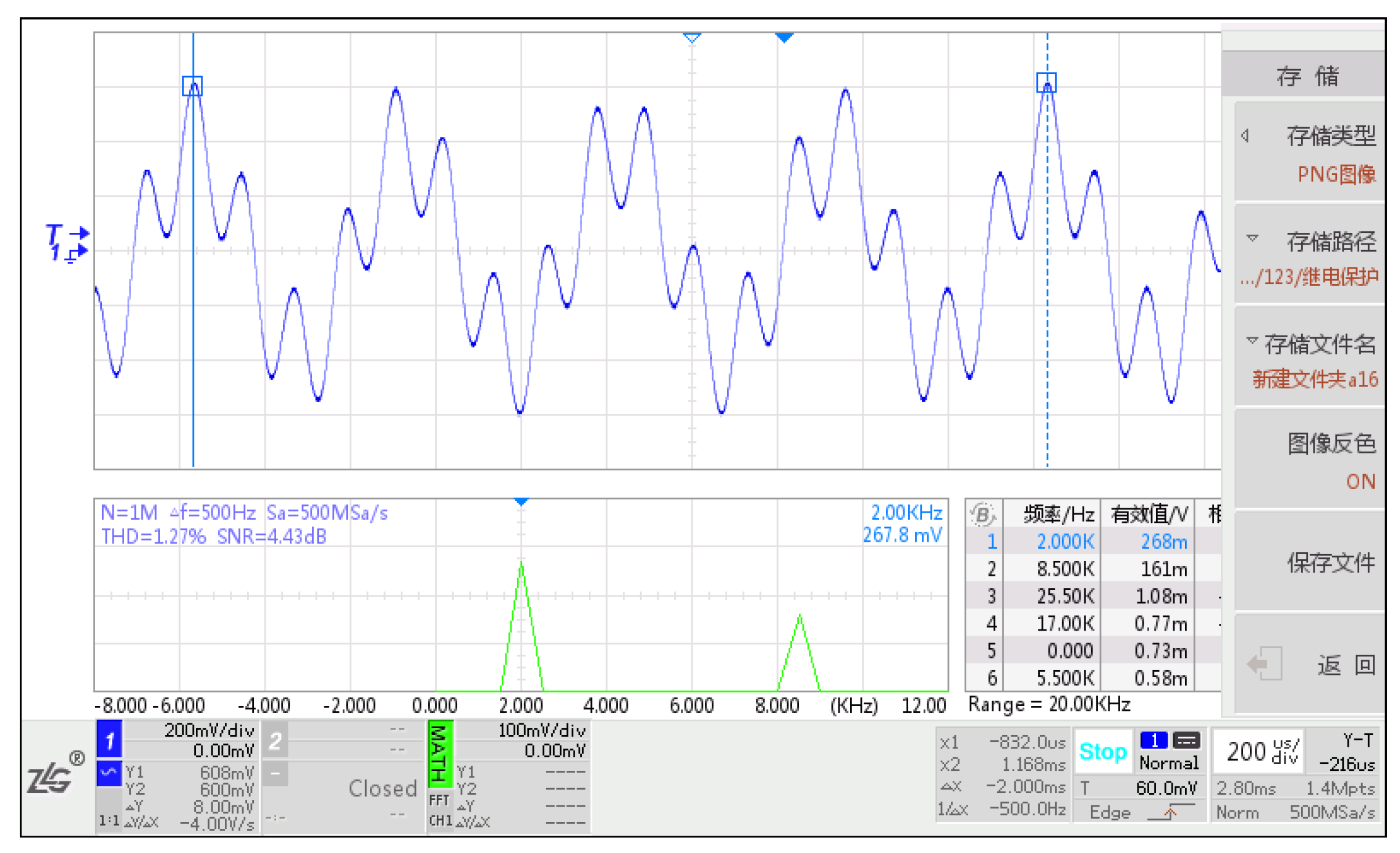

4.1. Causes of Data Fluctuations Due to Phase Drift in Mixed-Frequency Signals

4.2. Solution to Data Fluctuations

5. Determination of Circuit Parameters

5.1. Selection of Injection Signal

- According to standard engineering practice, a 20% safety margin should be reserved for the MCU input signal range. To simplify the hardware architecture, AC coupling is adopted for sampling. Consequently, the voltage at the ADC input must satisfy the following condition:

- To simplify the circuit design and enhance reliability in engineering applications, the number of distinct power supply voltage levels for all electronic components should be minimized while still satisfying the operating requirements of standard industrial devices. In this design, the operational amplifiers along the signal path are powered by a 12 V supply, the MCU operates at 3.3 V, and the DC bias voltage is set to 1.65 V.

- At each stage of the operational amplifier circuits, the signal peak values must not exceed the corresponding supply voltage limits of the integrated amplifiers. In the improved circuit proposed in this paper, the stages most prone to exceeding these limits are the first-stage current-to-voltage (I–V) conversion circuit and the second-stage subtraction circuit, as both stages handle the full amplitude of . Constrained by the frequency selection principles discussed in Chapter 3, the amplitude of should be as high as possible within the permissible range. As a result, the component appearing at the output of the first-stage I–V conversion circuit is substantially greater than the corresponding values of and .

| (V) | 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | 2000 | 100k | 1M | 10 |

| 7 | 1970 | 100k | 1M | 10 |

| (V) | 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 8000 | 40k | 1M | 10 |

| 4 | 8500 | 40k | 1M | 10 |

6. Results

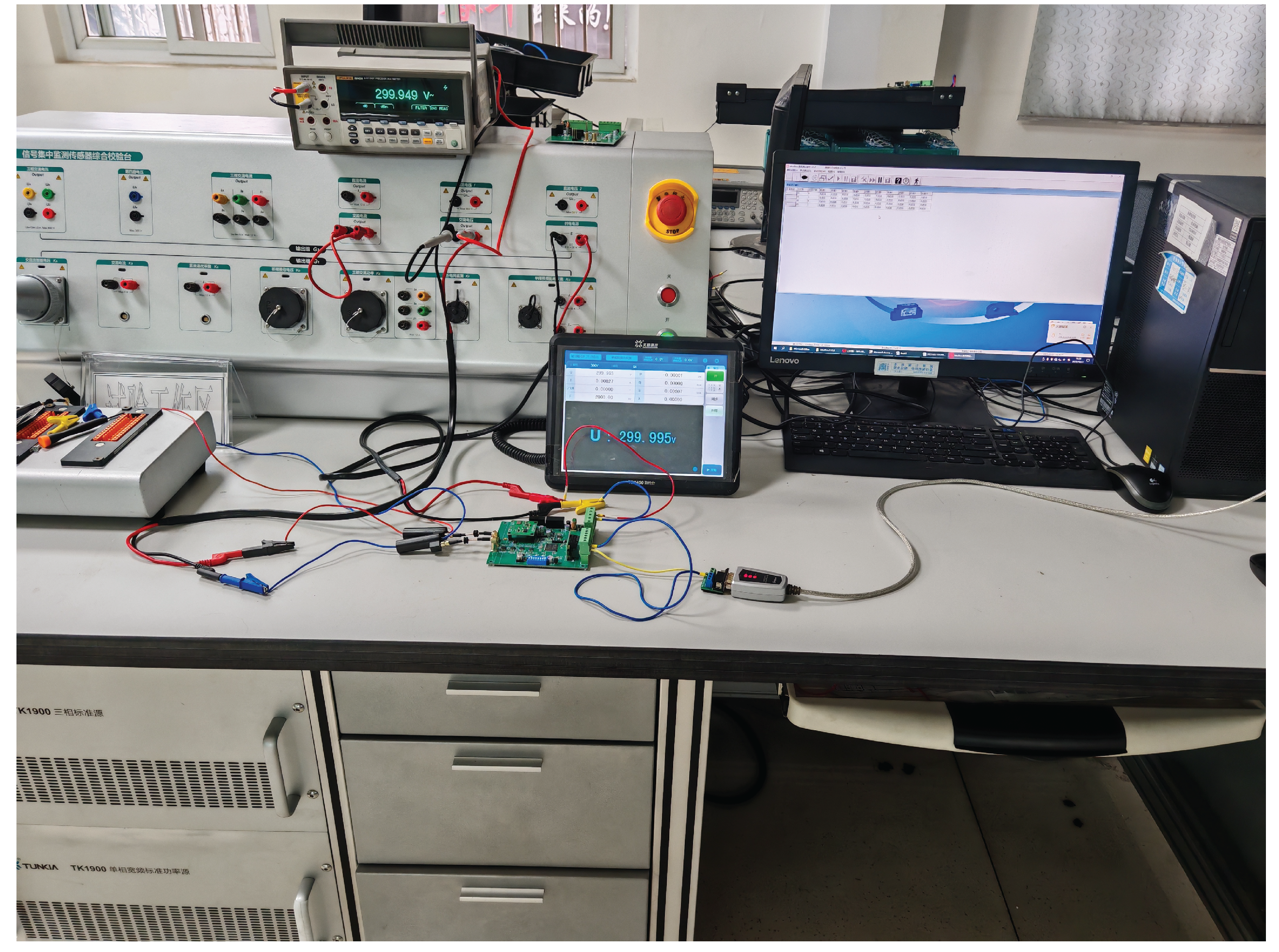

6.1. Test Conditions

| (V) | Cross-sectional area of the measured signal cable | |

|---|---|---|

| 0-500 | 50 | 4.0mm² |

| 0-500 | 50 | 2.0mm² |

| 0-300 | 2000 | 4.0mm² |

| 0-300 | 2000 | 2.0mm² |

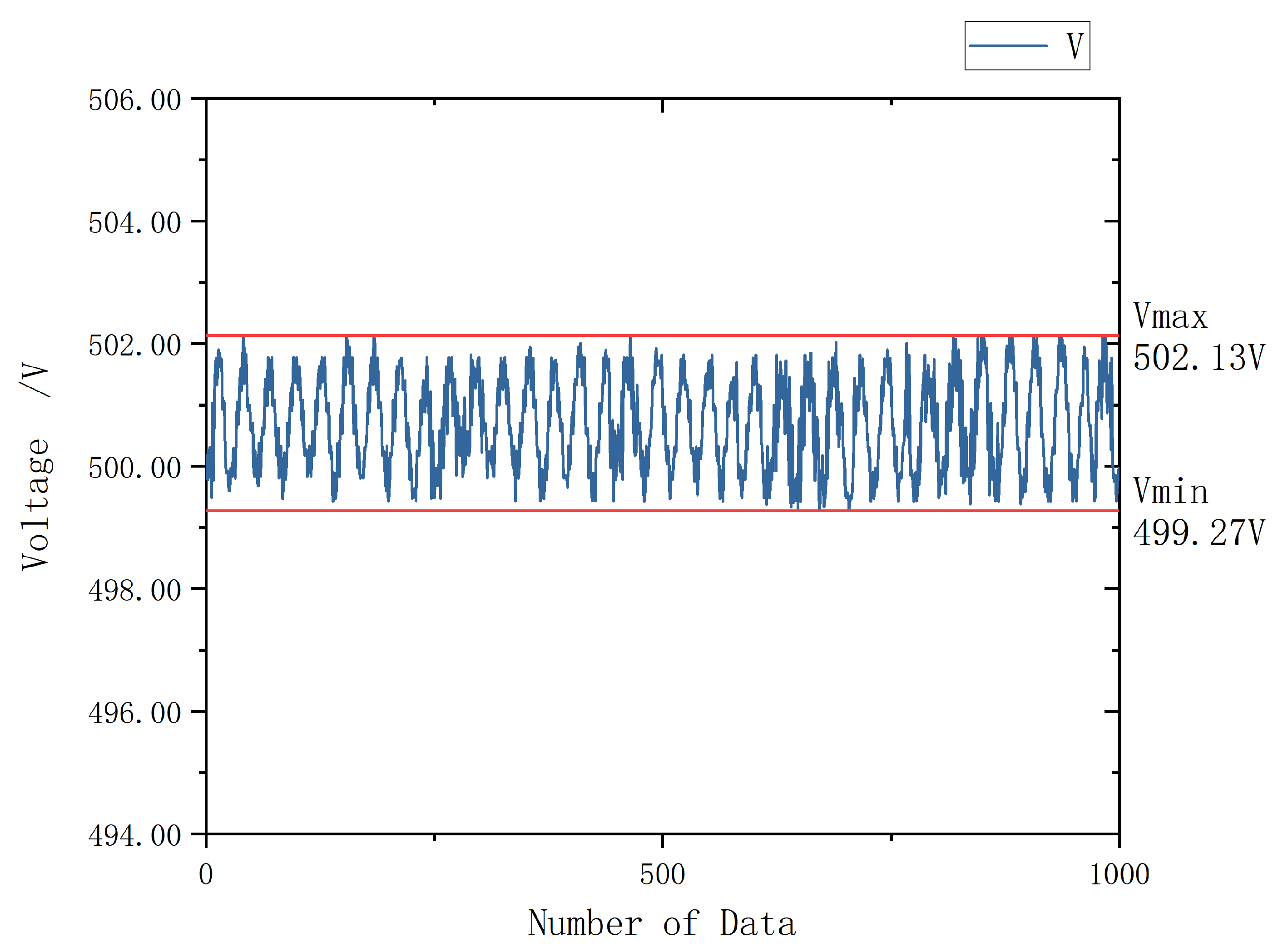

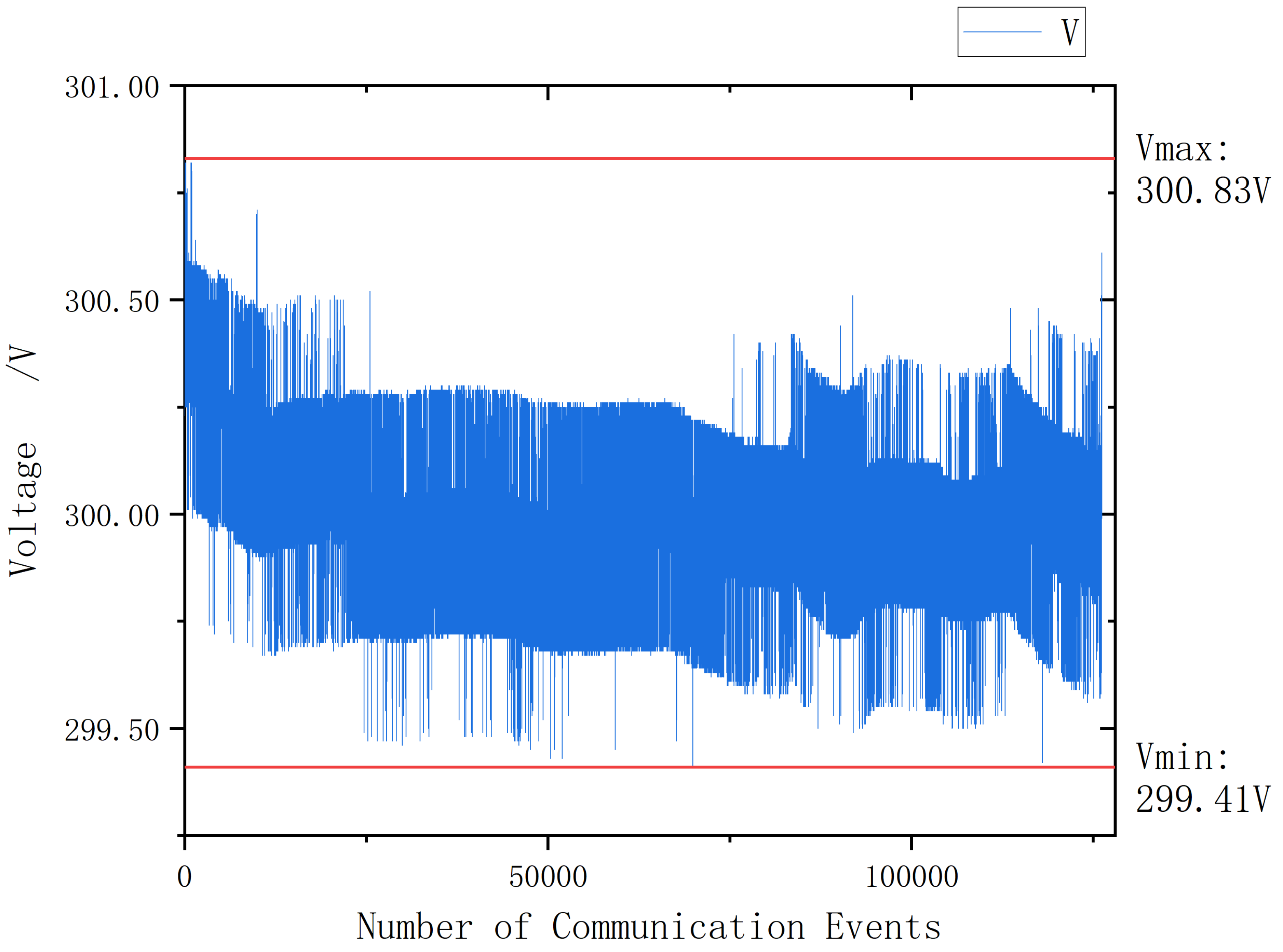

6.2. Results

| Theoretical Value(V) | Measured Value(V) | Error(%) |

|---|---|---|

| 30 | 30.05 | 0.02 |

| 60 | 60.15 | 0.05 |

| 90 | 89.99 | 0.00 |

| 120 | 120.39 | 0.13 |

| 150 | 150.14 | 0.05 |

| 180 | 180.42 | 0.14 |

| 210 | 209.86 | 0.06 |

| 240 | 240.33 | 0.11 |

| 270 | 270.35 | 0.13 |

| 300 | 300.14 | 0.05 |

| Theoretical Value(V) | Measured Value(V) | Error(%) |

|---|---|---|

| 50 | 49.88 | -0.25 |

| 100 | 100.24 | 0.24 |

| 150 | 149.81 | -0.13 |

| 200 | 199.70 | -0.15 |

| 250 | 250.24 | 0.10 |

| 300 | 300.54 | 0.18 |

| 350 | 350.50 | 0.14 |

| 400 | 400.59 | 0.15 |

| 450 | 450.74 | 0.16 |

| 500 | 500.49 | 0.10 |

7. Discussion

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PCB | Printed Circuit Board |

| MCU | Micro controller Unit |

| RMS | Root Mean Square |

References

- Ao, G.; Tang, J.; Li, D.; Zhang, W.; Yang, L.; Xu, Z. Research on Non-Invasive Voltage Measurement Method Based on Impedance Adaptation. Integrated Ferroelectrics 2024, 240, 517–533. [CrossRef]

- Balsamo, D.; Porcarelli, D.; Benini, L.; Davide, B. A new non-invasive voltage measurement method for wireless analysis of electrical parameters and power quality. 2013 IEEE SENSORS 2013, pp. 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Haberman, M.; Spinelli, E. A Noncontact Voltage Measurement System for Power-Line Voltage Waveforms. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2020, 69, 2790–2797. [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, D.; Donnal, J.; Leeb, S.; He, Y. Non-Contact Measurement of Line Voltage. IEEE Sensors Journal 2016, 16, 8990–8997. [CrossRef]

- Reza, M.; Rahman, H.A. Non-Invasive Voltage Measurement Technique for Low Voltage AC Lines. 2021 IEEE 4th International Conference on Electronics Technology (ICET) 2021, pp. 143–148. [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Ma, F.; Yang, Q.; Ni, H.; Bai, T.; Ke, K.; Qiu, Z. Research on Non-Contact Voltage Measurement Method Based on Near-End Electric Field Inversion. Energies 2023. [CrossRef]

- Suo, C.; He, M.; Zhou, G.; Shi, X.; Tan, X.; Zhang, W. Research on Non-Invasive Floating Ground Voltage Measurement and Calibration Method. Electronics 2023. [CrossRef]

- Walczak, K.; Sikorski, W. Non-Contact High Voltage Measurement in the Online Partial Discharge Monitoring System. Energies 2021. [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Liu, H. Research on Synchronous Measurement Methods Based on Non-Contact Sensing. 2024 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Power Science and Technology (ICPST) 2024, pp. 414–419. [CrossRef]

- xiangyu shen.; Xu, Y.; Zhuang, W.; Xie, N. A Non-Contact Voltage Measurement Technology for Three-Phase Cables. 2025 International Conference on Electrical Automation and Artificial Intelligence (ICEAAI) 2025, pp. 676–679. [CrossRef]

- Shenil, P.S.; George, B. Nonintrusive AC Voltage Measurement Unit Utilizing the Capacitive Coupling to the Power System Ground. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2021, 70, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- ShenilP., S.; Raveendranath, A.; George, B. Feasibility study of a non-contact AC voltage measurement system. 2015 IEEE International Instrumentation and Measurement Technology Conference (I2MTC) Proceedings 2015, pp. 399–404. [CrossRef]

- Haberman, M.; Spinelli, E. Noncontact AC Voltage Measurements: Error and Noise Analysis. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2018, 67, 1946–1953. [CrossRef]

- Delle Femine, A.; Gallo, D.; Landi, C.; Lo Schiavo, A.; Luiso, M. Low power contactless voltage sensor for low voltage power systems. Sensors 2019, 19, 3513.

- Zhang Wei, Li Xiaojian, L.J. Simulation Analysis of Non-contact Voltage Sensor Electrode. Mechanical & Electrical Engineering Technology 2021, 50, 41–45.

- Huang Rujin, Suo Chunguang, Z.W.Z.J.Z.X. Self-Calibration Method for Non-Contact Voltage Measurement Based on Impedance Transformation. Chinese Journal of Scientific Instrument 2023, 44, 137–145. [CrossRef]

- Šerlat, A.; Grzegrzółka, M.; Czuba, K. Two-tone RF signal phase drift measurement system. Measurement 2025, 243, 116183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).