Submitted:

13 November 2024

Posted:

14 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

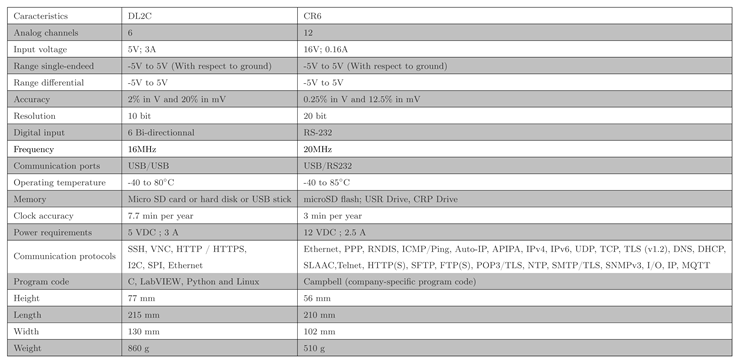

- The financial cost of high precision stations is too costly;

- The programming source code for the majority of these acquisition units is inaccessible;

- Some data collection devices on the market are incapable of providing the high accuracy of measurement required in experimental research;

- Some of these mobile and autonomous dataloggers have insufficient storage capacity;

- The majority of mobile dataloggers are not linked to the internet network;

- Experts remain skeptical about the Arduino’s performance and accuracy in regard to a scientific experimental investigation. For instance, there are few experimental research equipment using Arduinos materials;

- Finally, for business reasons, some data aquisition units are specific and can’t be use with any sensor. In other words, they are not universal.

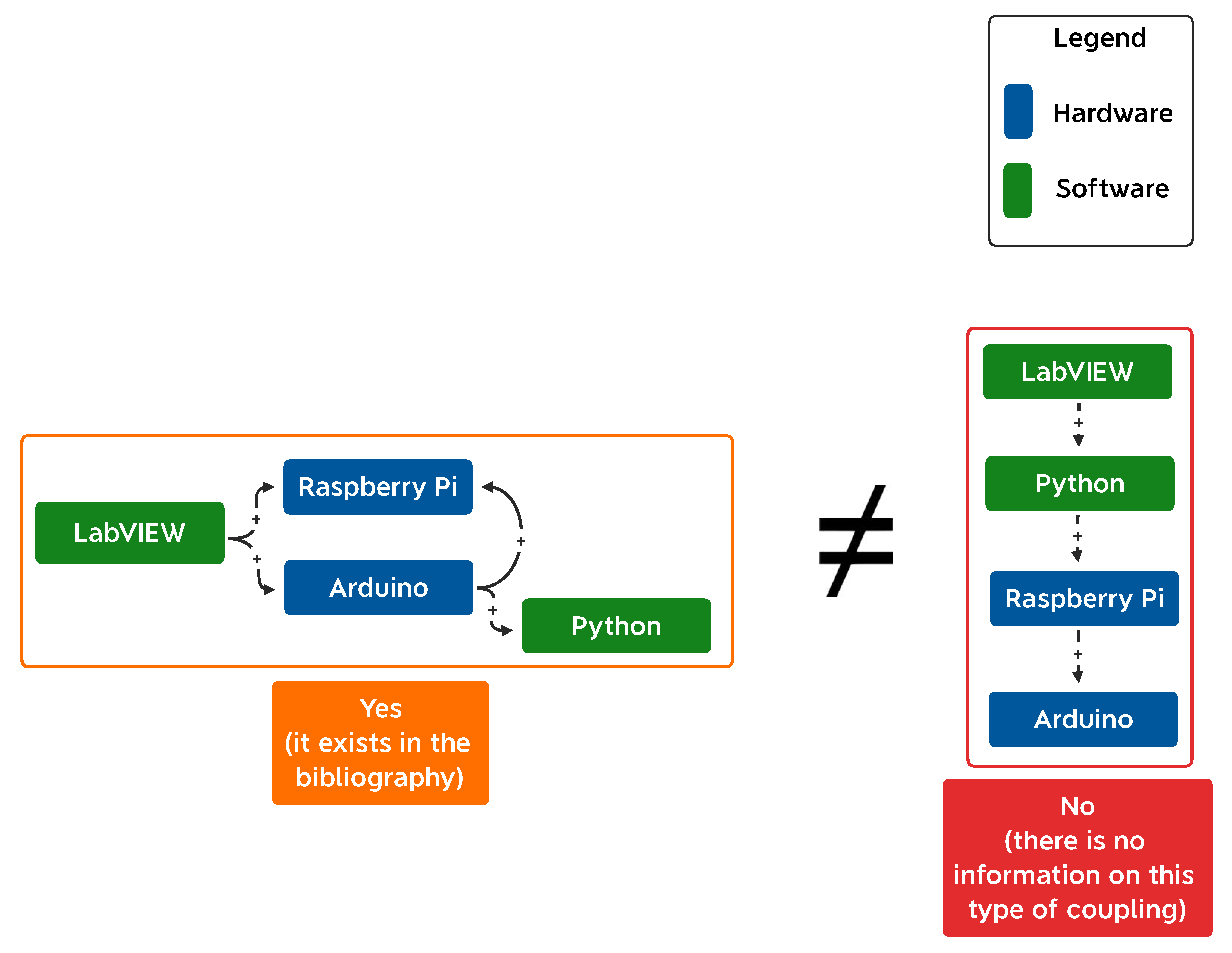

2. Related Work (i.e., State of Art)

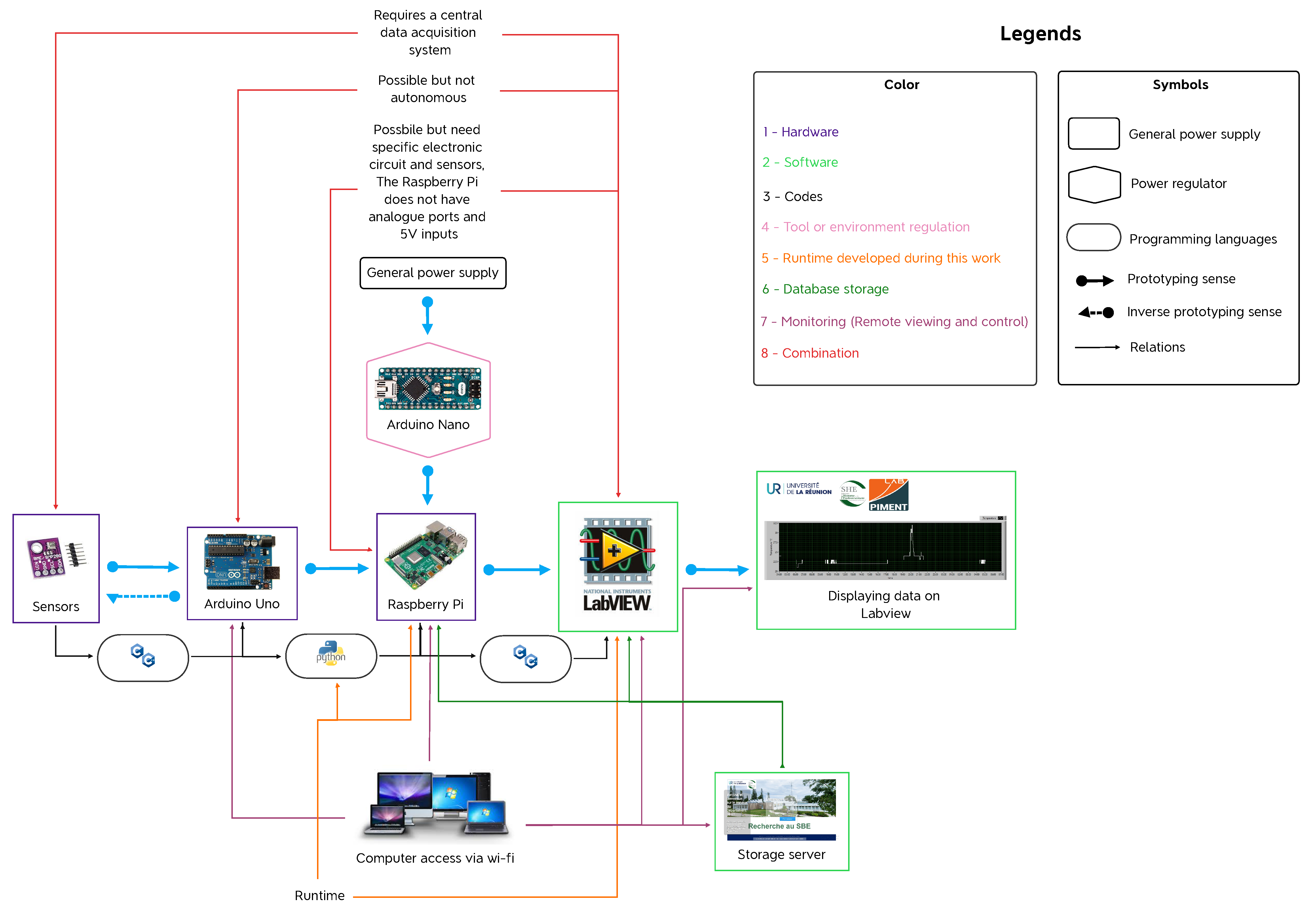

3. System Description

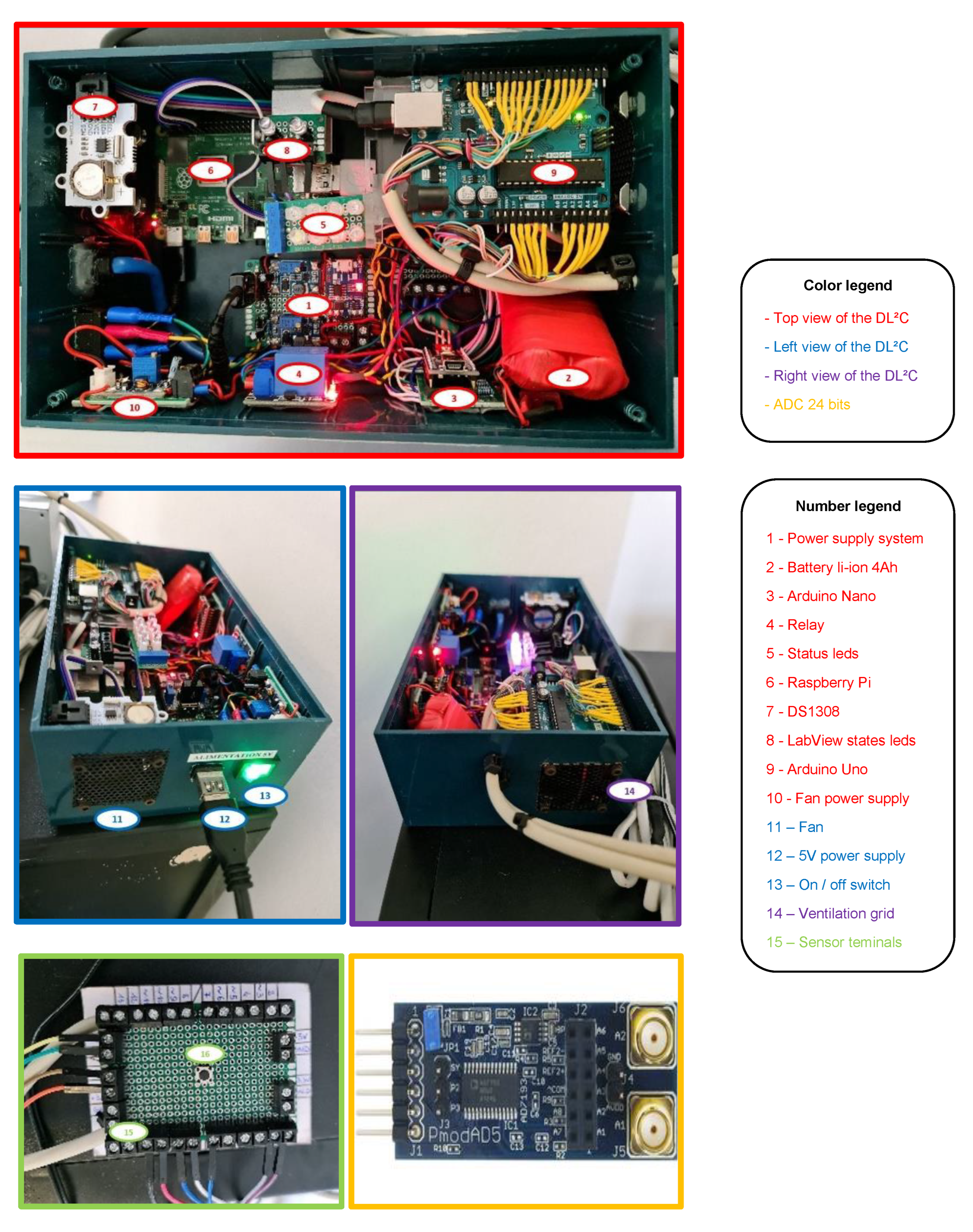

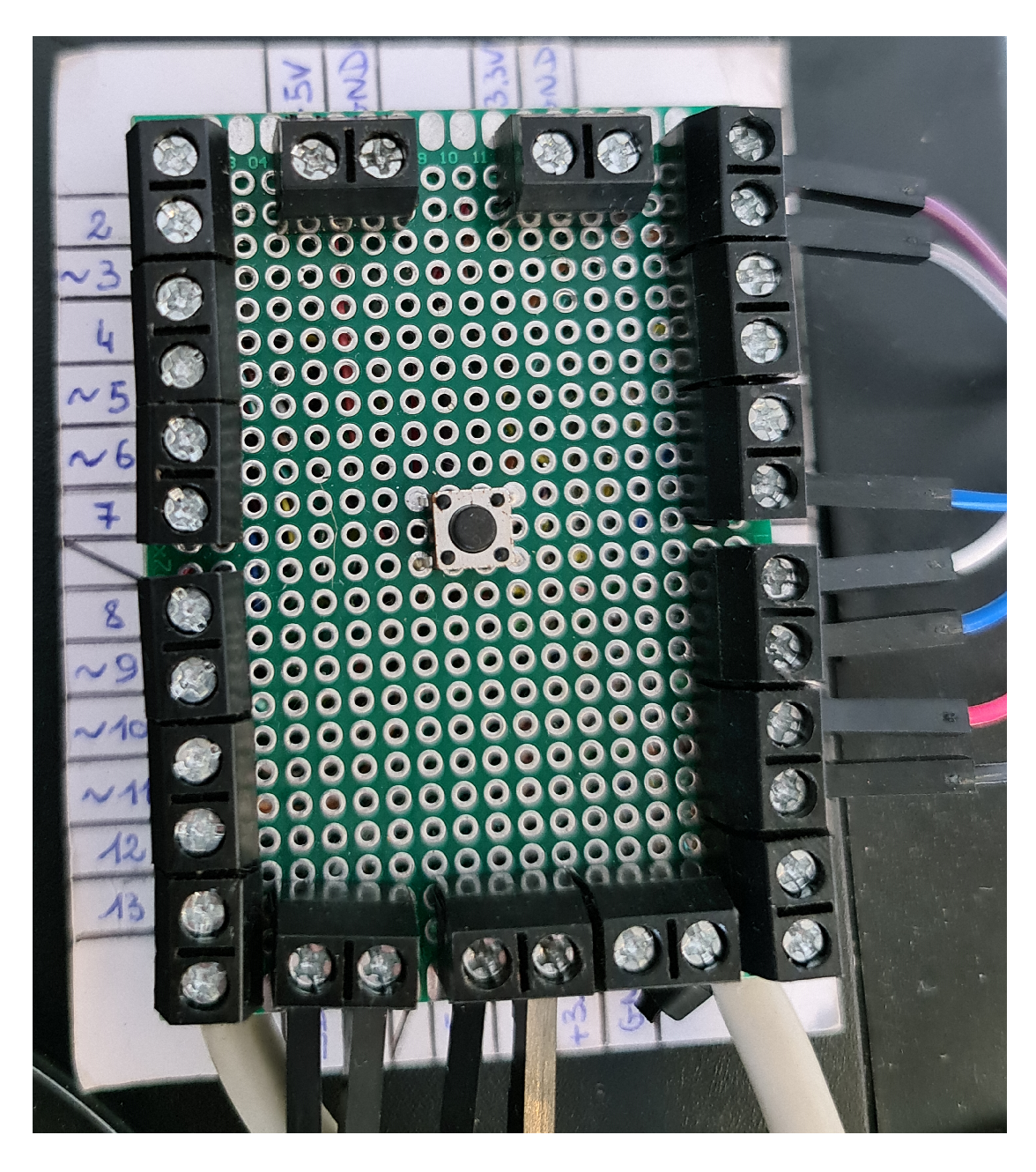

3.1. Hardware

3.1.1. Components Description and Operating Principle

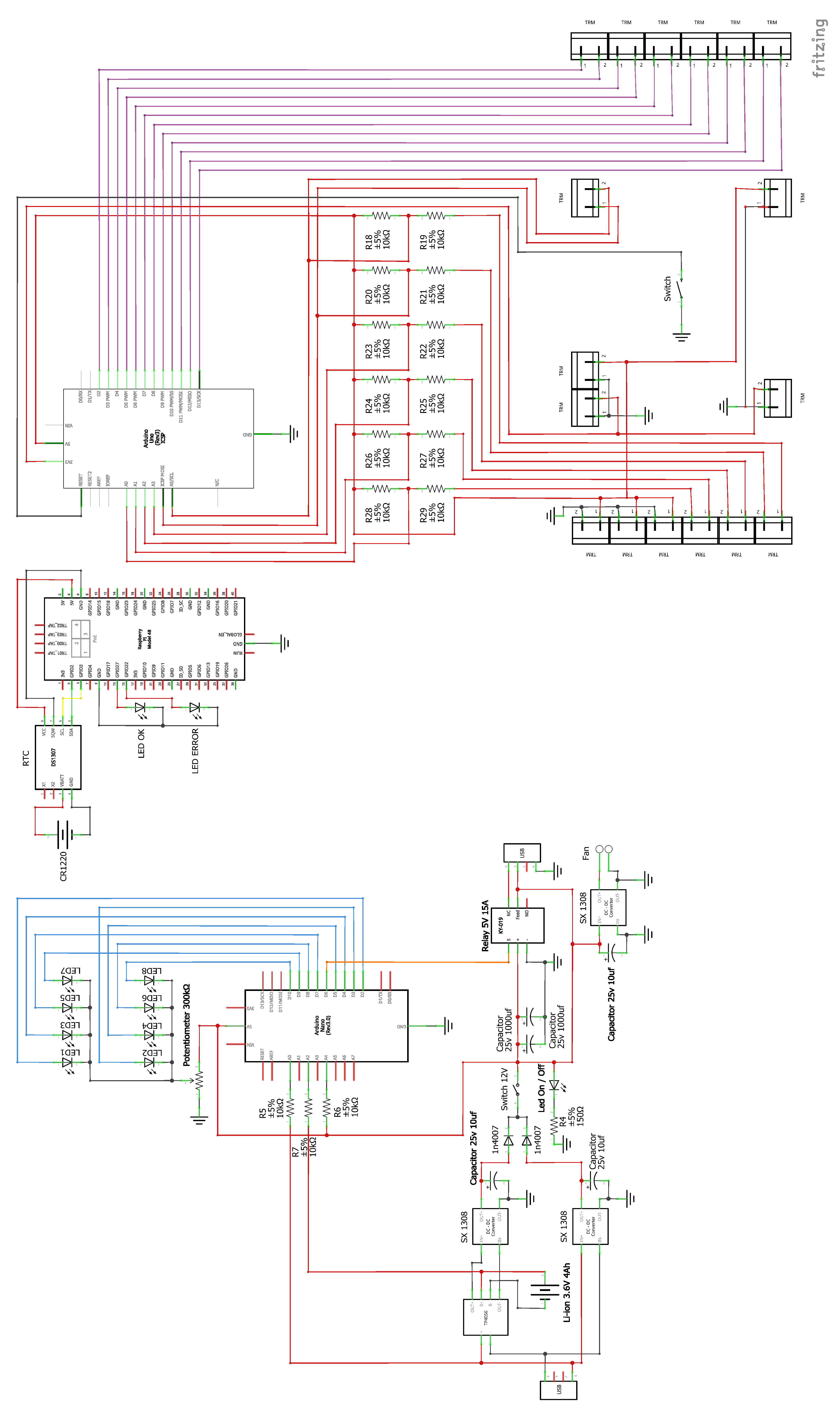

3.1.2. Electronic Schema of the

- A direct power supply from a 220V power adapter is comprised of an SX1308 module that increases the voltage through a potentiometer, followed by a 1N4007 diode. This power supply is accomplished through a 5V USB connection with a nominal current of 4A.

- A power source from the acquisition unit’s internal battery. the battery power section is fitted with a TP4056 module that controls and protects the 4Ah lithium-ion battery. When the battery voltage hits 2.9V, the TP4056 module shuts off power to the battery, although it is always capable of charging the battery and providing current if power is provided. The charging is stopped when the battery hits 4.2V. The SX1308 module subsequently boosts the voltage at the TP4056 module’s output, and the current is then sent via a 1N4007 diode.

- A voltage divider bridge has been constructed to split the voltage in half while also supplying a reference value of 5V to the Arduino Uno’s ADC. The impedance associated with the measured voltage must be at least ten times that of the divider bridge’s resistors.

- The Arduino code has been changed to link the voltage ranges -5V à 0V with the numerical values 0 to 511 and 0V à 5V with the numerical values 511 to 1023. 1023 is the highest ten-bit numerical number that the Arduino can give.

- Two of them are reserved for peripherals, such as a USB keyboard, mouse, or keys;

- The third is for the power adapter’s connection.

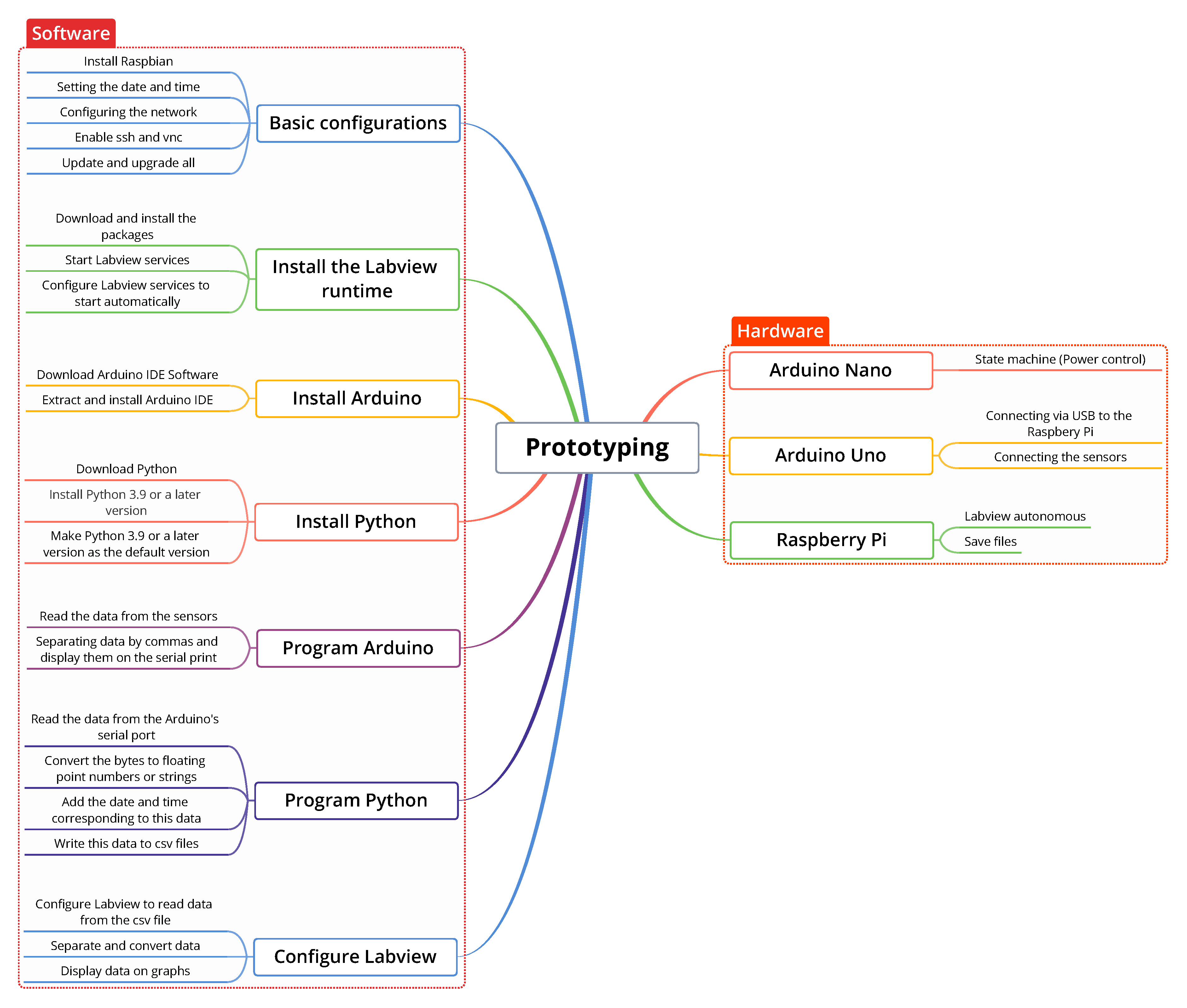

3.2. Software

-

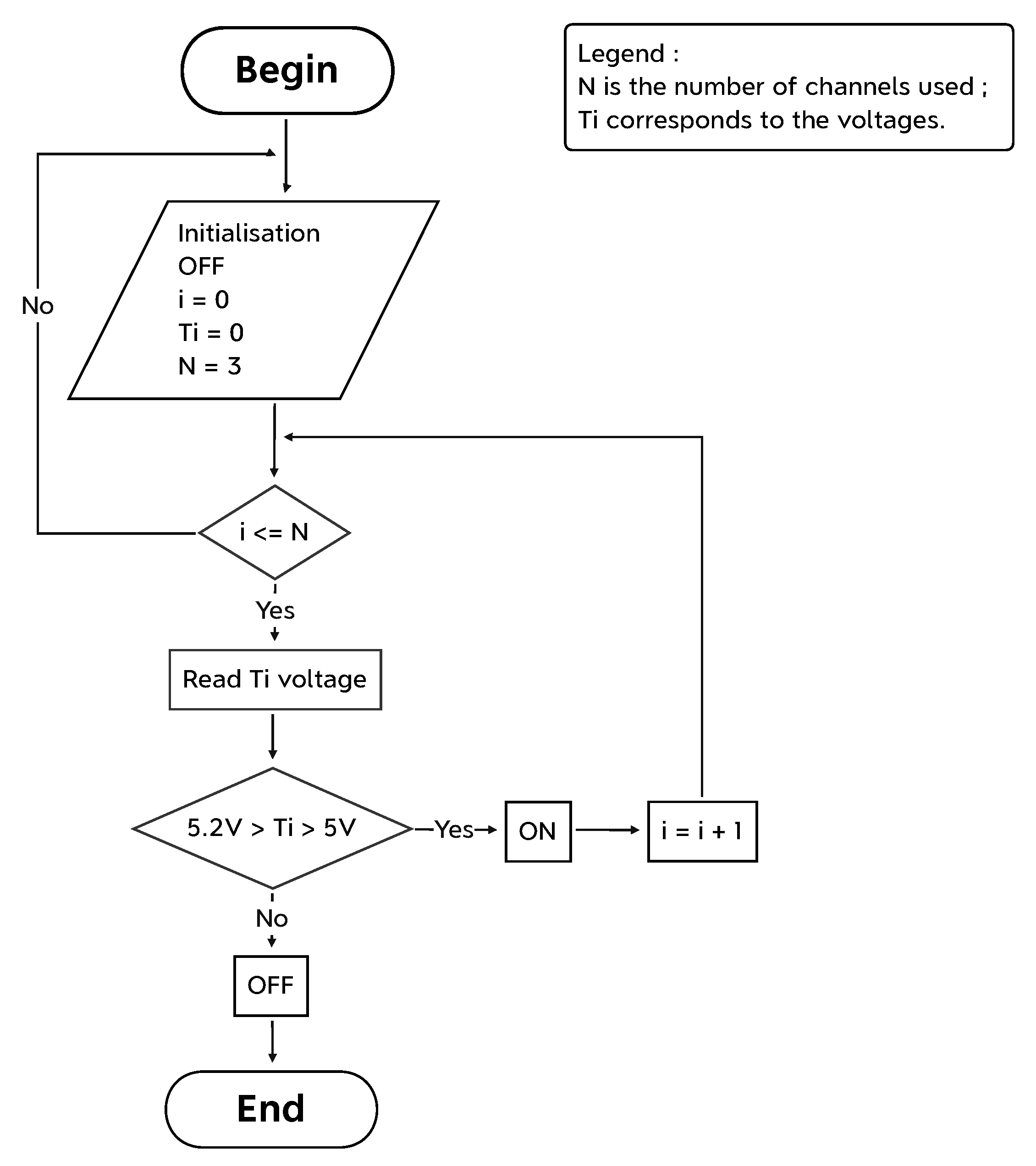

Concerning the Arduino Nano:

- -

- It enables the management of the power supply and alarm systems (state of the battery and the electric sector). The latter constantly reads the analog ports A0 (voltage at the ’s input), A1 (battery voltage), A2 (voltage before the relay), and A3 (voltage after the relay) in volts, while ensuring that the specified thresholds for each electrical component are not exceeded. If the circuit’s voltage falls below 5V, the Arduino Nano disables the system’s power source by opening the mechanical relay to avoid damaging the components. Additionally, the Arduino Nano has status LEDs that flash. When the voltages fall below the thresholds, the red LEDs illuminate; when the voltages rise over the thresholds, the LEDs flash in various colors,

- -

- The analog reading precision is about 10 bits or between 100 and 300mV.

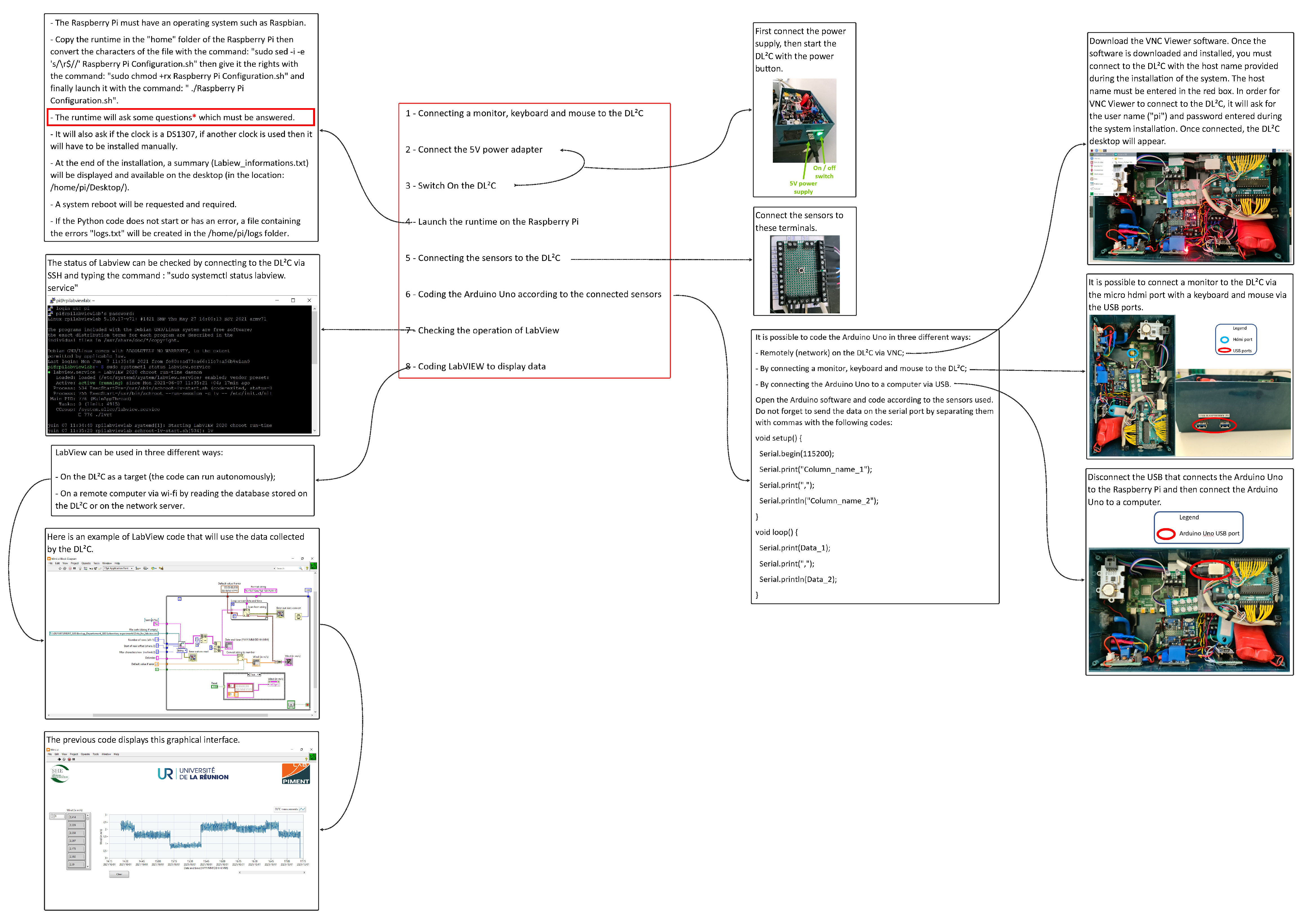

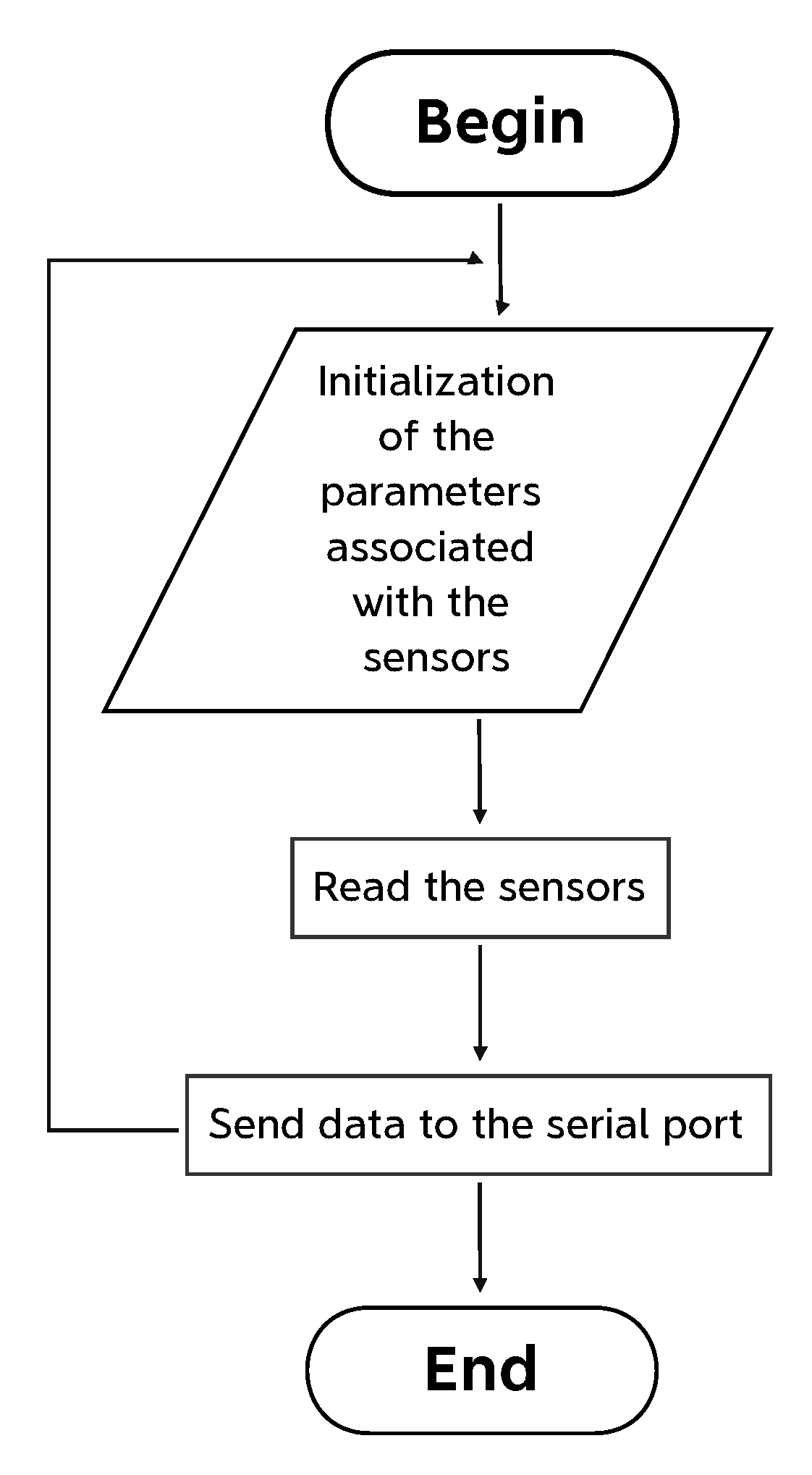

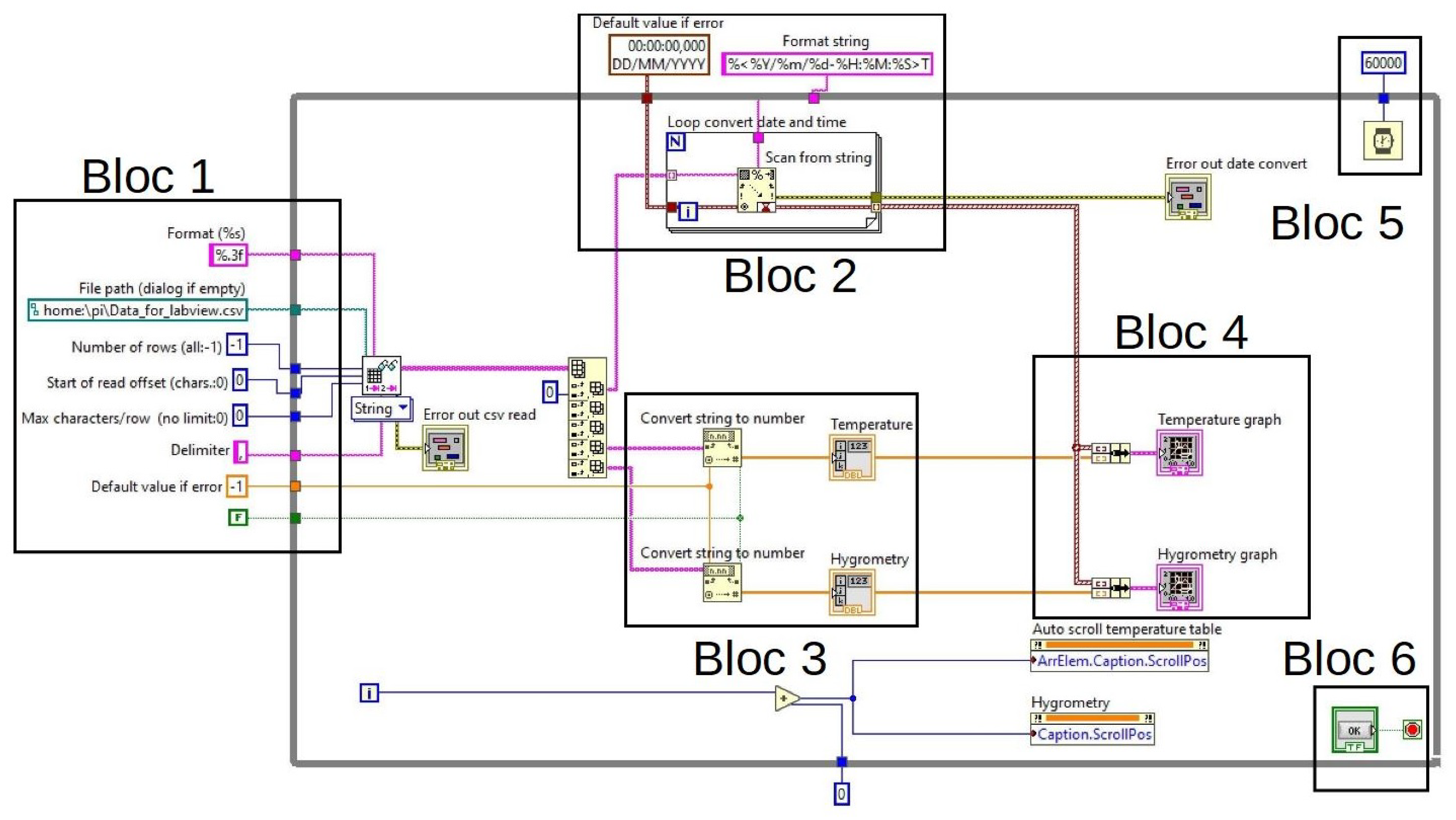

- The sensors are linked to the Arduino Uno through the USB cable. The collection of signals and the reading and transfer of data to the serial port are shown in Figure 9;

-

With regards to the Raspberry Pi:

- -

- Python is the programming language that is used on raspberry Pi;

- -

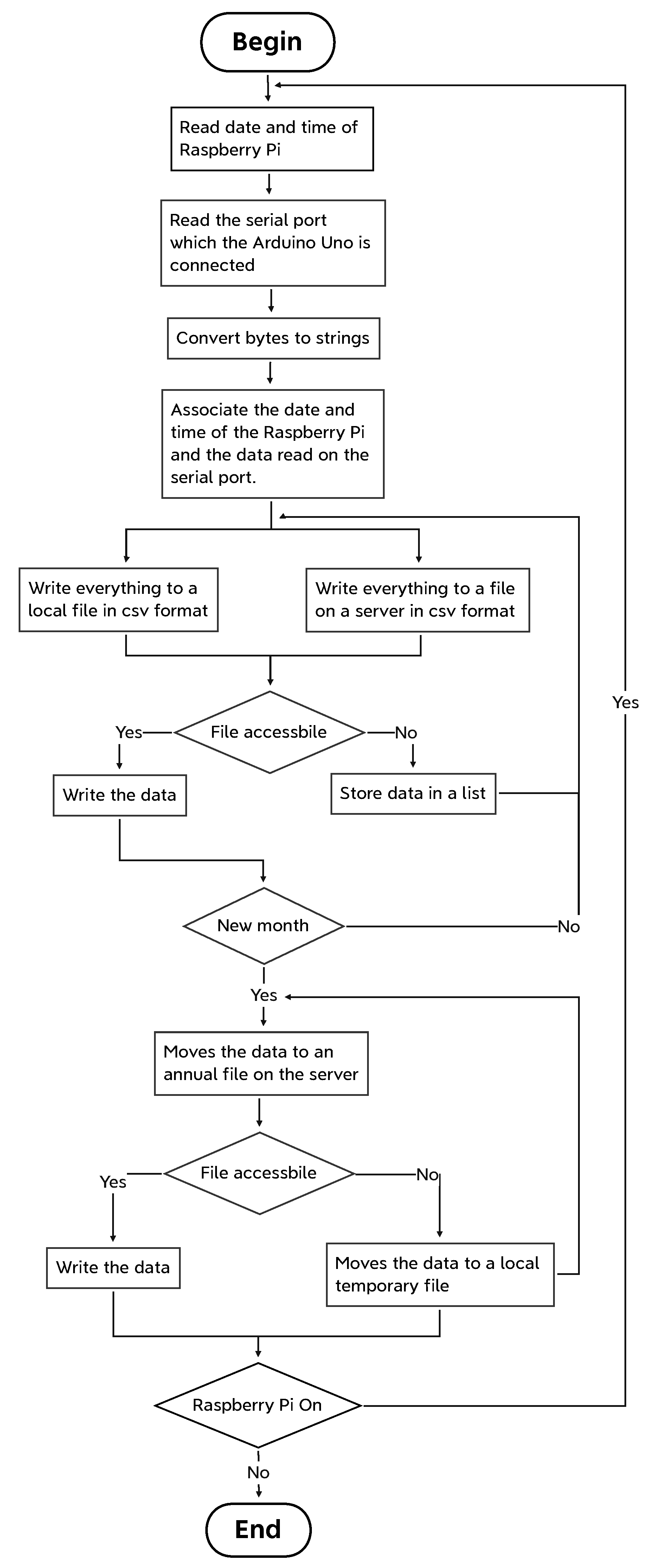

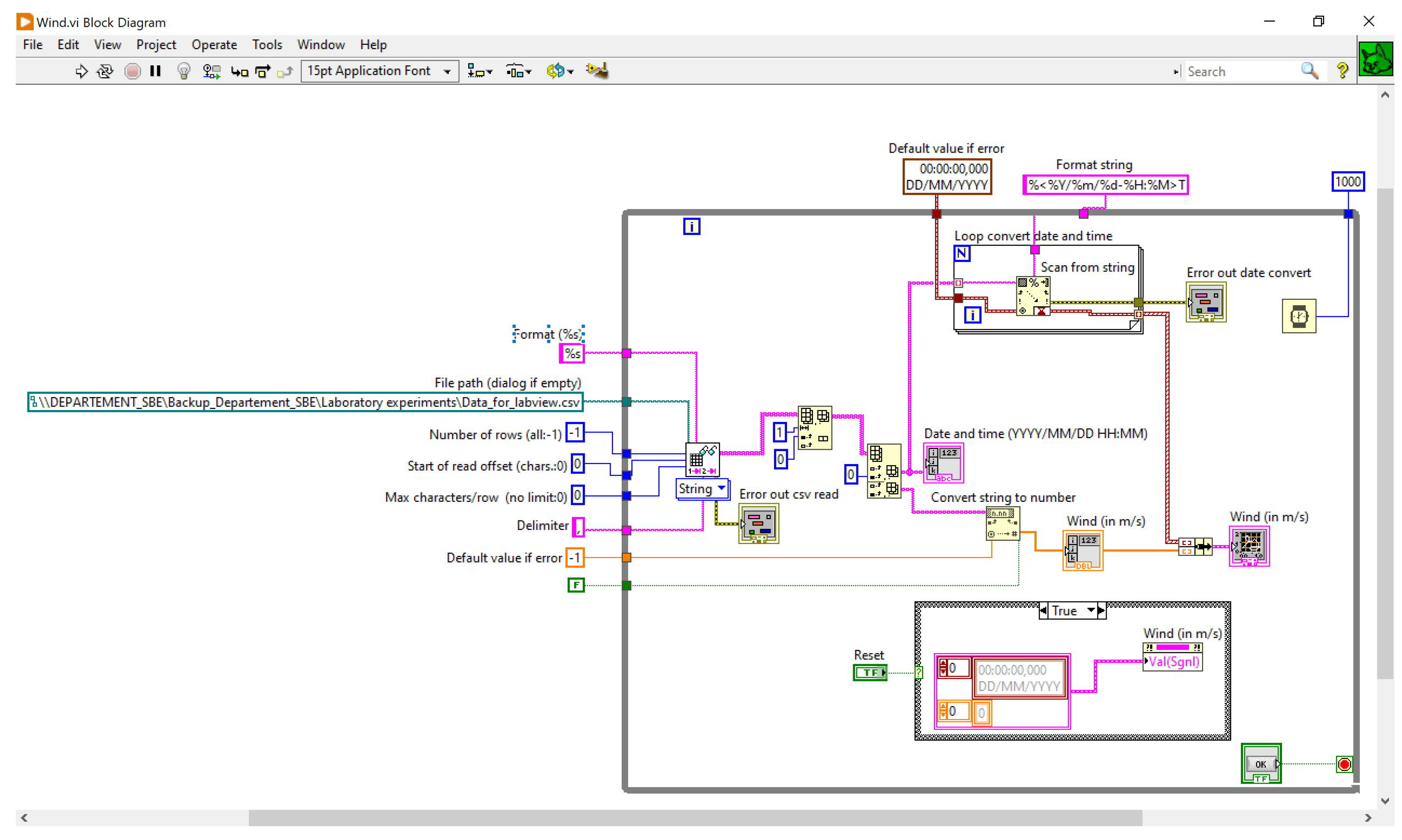

- The Arduino Uno’s database is obtained using the Python code shown in Figure 10 and then saved in multiple CSV files (Comma-Separated Values);

- -

- The Raspberry Pi’s serial port is configured as follows: /dev/ttyACM0 is the port name; the baud rate is 115200, and the decoding is UTF8;

- -

- In the background, Python code is run. It is started immediately upon the Raspberry Pi’s starting. Crontab allows users of Linux systems to schedule the execution of scripts, commands, or programs. Additionally, this application (i.e., Crontab) provides for executing a bash file (i.e., Bourne-Again shell, a script-type command-line interpreter) capable of starting the Python code according to a specified cycle;

- -

- When a problem happens during the Python code’s initialization, a full explanation of the issue is written to the "logs.txt" file. This file will be created in the directory /home/pi/log;

- -

- Because the Raspberry Pi lacks an internal clock, the date and time are not saved in memory. As a result, an external hardware clock is necessary. For resolve the problem, an external hardware clock in a DS1307 RTC (Real Time Clock) module is added. After installing and synchronizing the DS1307 module, the date and time are saved in memory. Each time the Raspberry Pi boots, the date and time are received via the DS1307 module. This module communicates through the I2C protocol when connected to the SDA (GPIO2) and SCL (GPIO3) ports and powered via the VCC and GND ports (see electrical schematic in Figure 6). In addition, the DS1307 enables the central unit to retain and update the clock settings specified even after the device is turned off or restarted. Apart from the DS1307 module, the Raspberry Pi’s date and time may be synchronized through an Internet connection to an NTP (Network Time Protocol) server;

- -

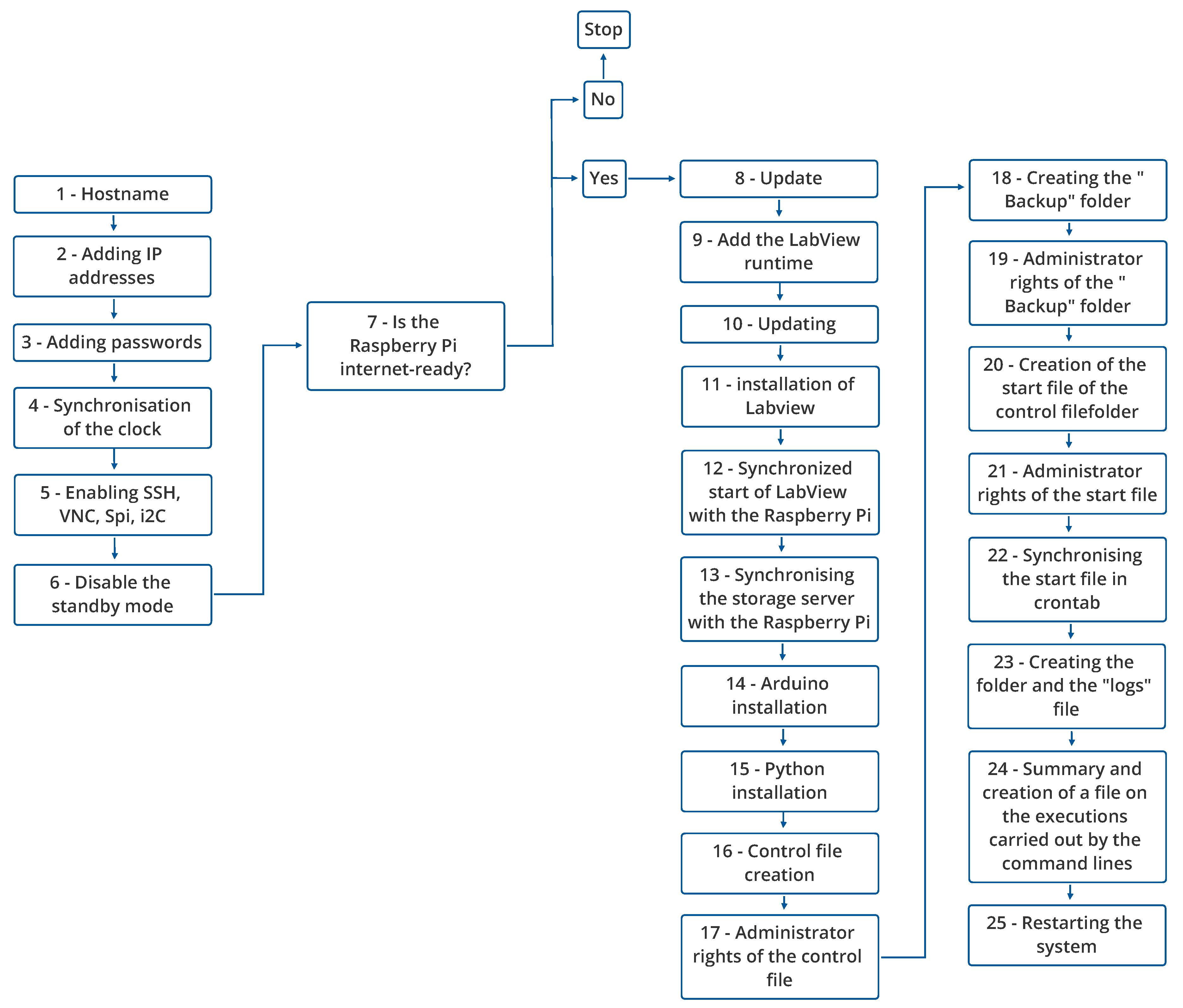

- An executable has been developed to facilitate and expedite the installation of Raspberry Pi Linux applications. The procedure is accomplished by launching just three instructions rather than 500 lines of commands and codes. This program is named "Raspberry Pi Configuration.sh" and is shown in Figure 13. It is a bash file. Then, it is necessary to transfer the bash file to the Raspberry Pi, convert the characters (the file was generated in a text editor on a Windows PC; the characters on a Linux system are different), and run it. The software begins by requesting the date and time, followed by the hostname (of the Raspberry Pi) and then the password. The installation procedure is automated for many hours (LabView, Python, Arduino, SSH, VNC, codes, and clock), and the Python code is generated.

- -

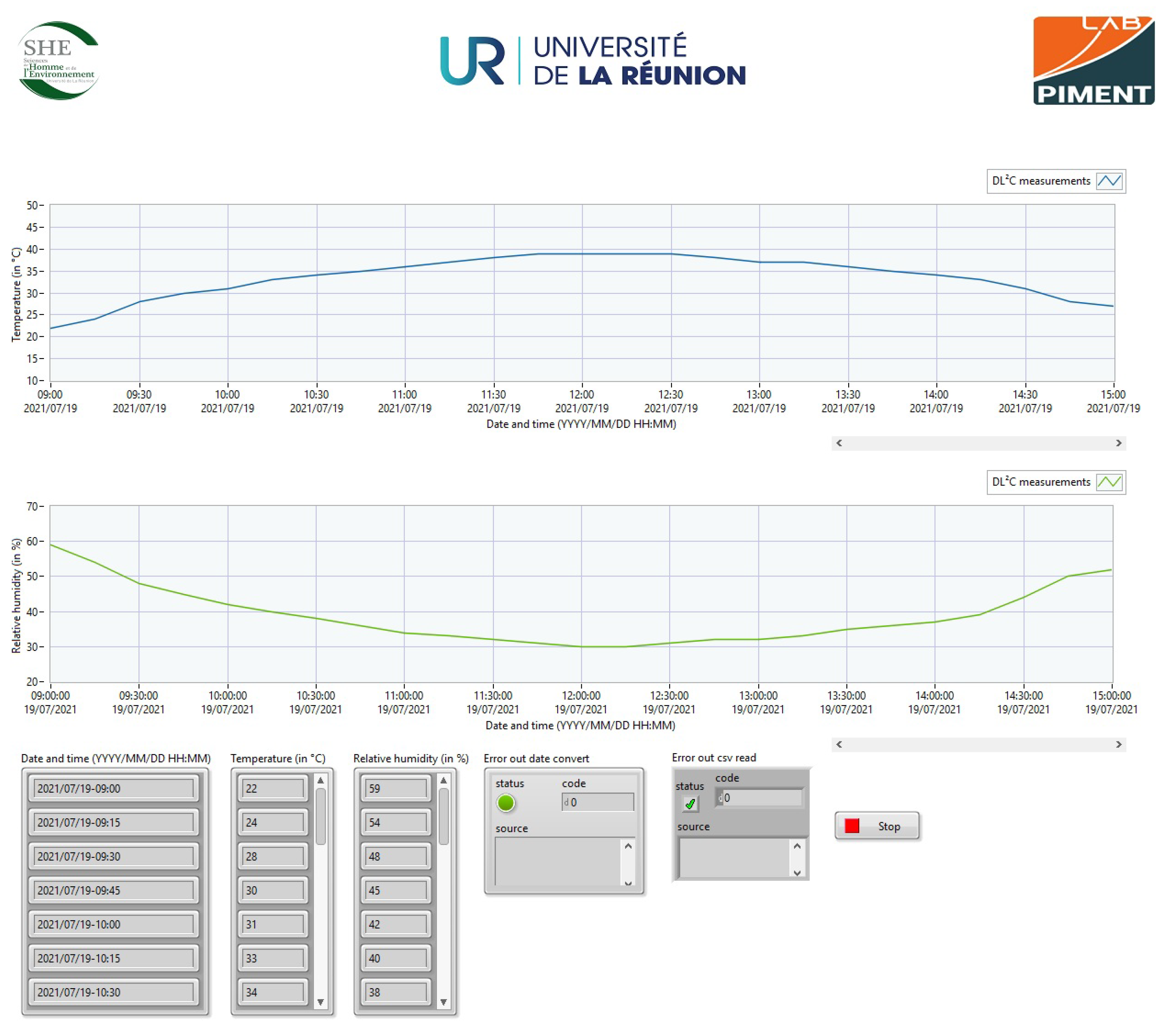

- One of the ’s unique features is its network connectivity through the VNC and SSH communication protocols, as well as the LabView environment installed on the Raspberry Pi. These communication protocols provide remote access to the without the need for a screen, keyboard, or mouse.

3.3. Data Storage

- ’s memory: The data collection system is fitted with a sixteen-gigabyte micro SD memory card that serves as internal memory. This internal memory space is used by both the operating system, which requires about two gigabytes, and CSV files.

- External storage’s: CSV files are saved on a network server to guarantee high file availability and prevent overloading the ’s internal memory.

- Two "LabView Data.csv" files. The first file, "Data for LabView.csv," is saved in the datalogger and includes one month’s worth of data. The second file, "Data for LabView.csv," operates similarly to the first, except that it is saved on the network server to provide a secondary backup in the event of failure or data loss. These files are compatible with LabView;

- On the network server, a yearly file named "Overall Backup.csv" is kept. Each month, the "Data for LabView.csv" file’s contents are copied to the "Overall Backup.csv" file. After all data has been transferred to this yearly file, the "Data for LabView.csv" files will be emptied to make room for fresh data;

- On the Raspberry Pi, a temporary file named "Monthly Backup.csv" is generated. If the "Overall Backup.csv" file is not available, the data will be saved in this temporary file, which will enable the "Data for LabView.csv" file to be emptied without interruption or data loss. After transferring the pending data in this temporary file to the "Data for LabView.csv" file, the "Monthly Backup.csv" file is deleted.

4. Experiments

4.1. Reliability Test, Results and Discussions

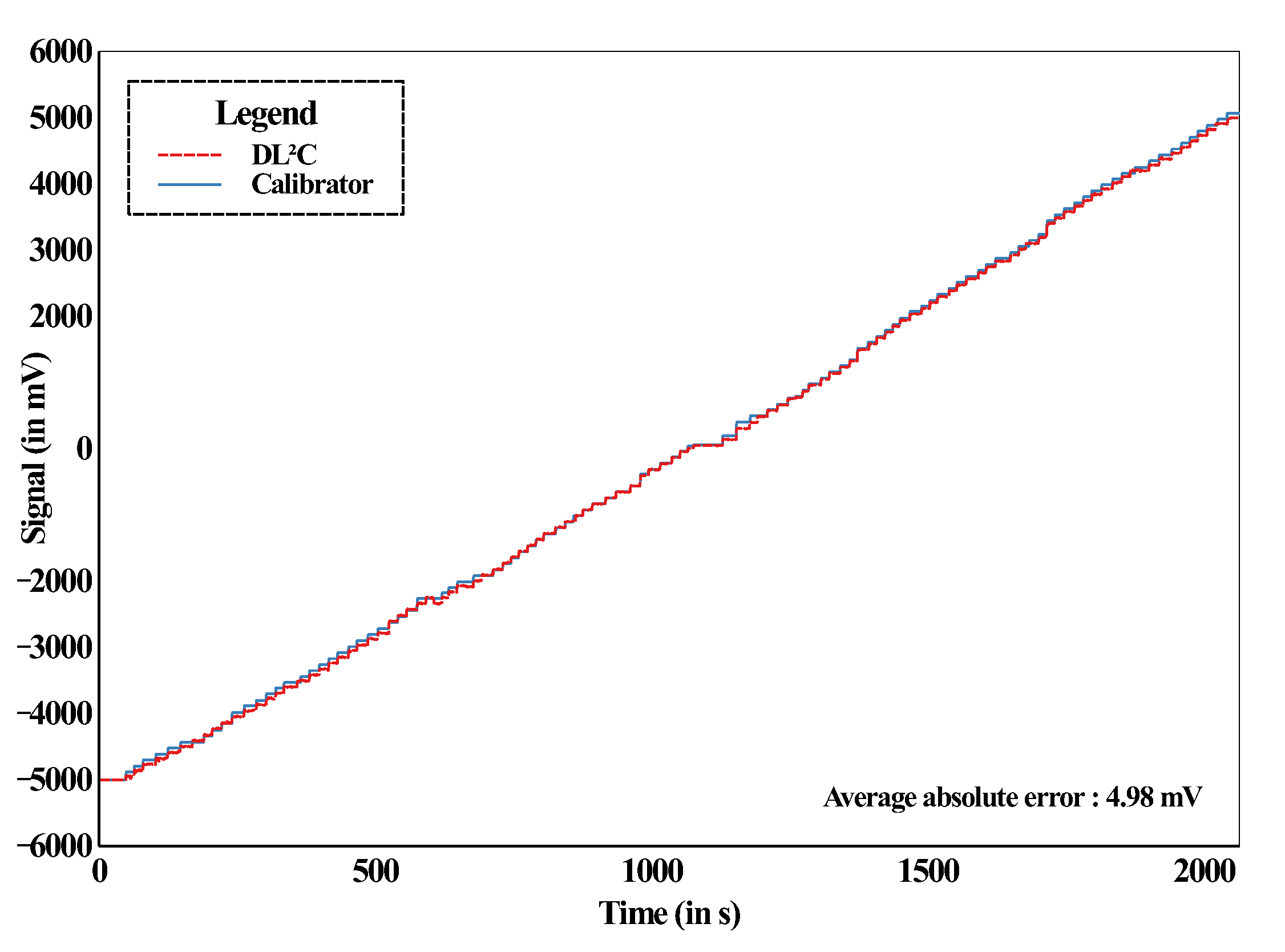

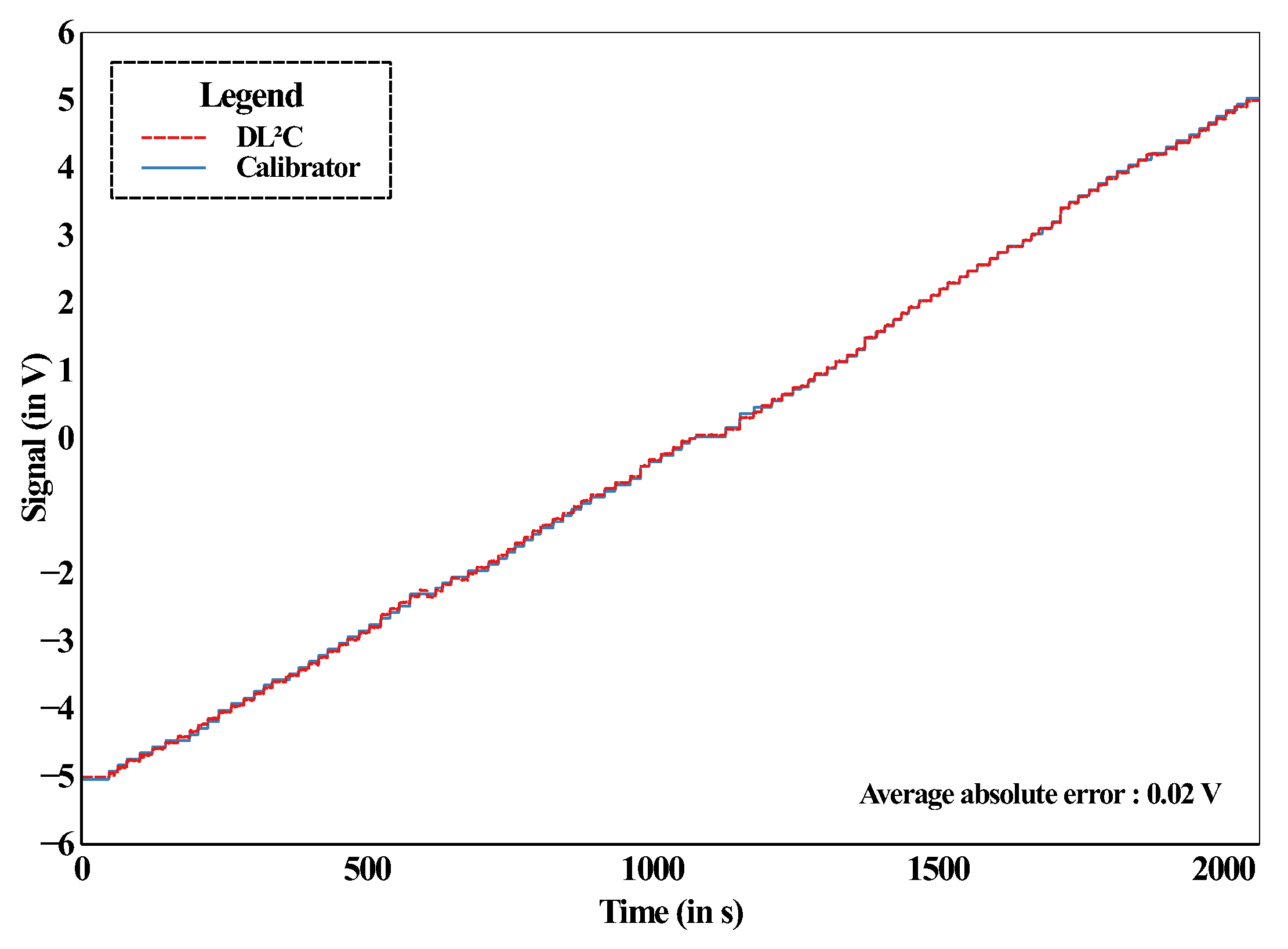

4.1.1. The Reference Generator Signal Test

4.1.2. Comparisons Results and Discussions

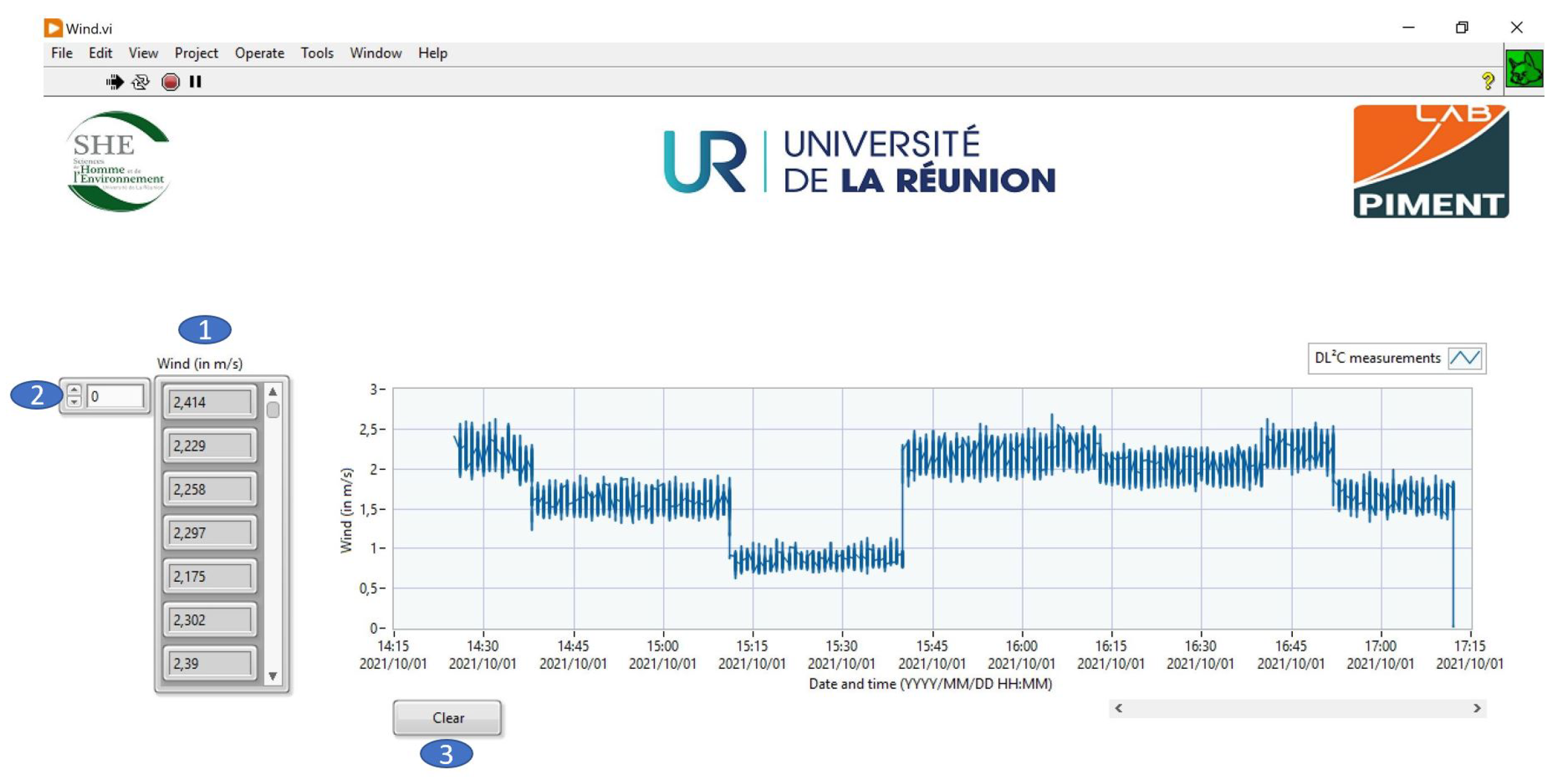

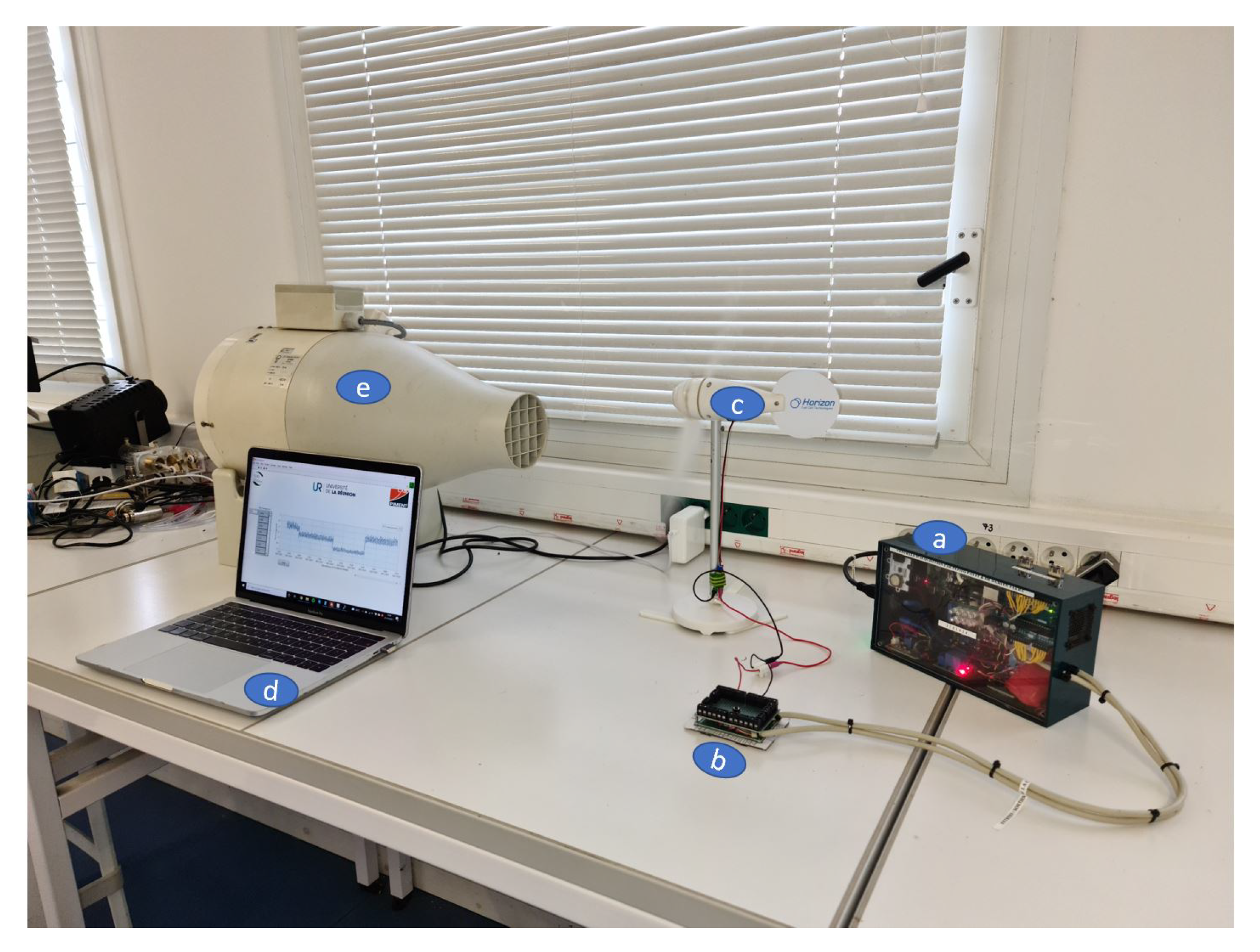

4.2. Application Example

4.2.1. Description of the Experimentation

- Connect the DL2C to the wind turbine’s analog ports A0 to A5 to read the voltages given by the device.The positive terminal of the wind turbine is connected to the analog port A0, while the negative terminal is connected to the common ground GND of the data collecting center;

- The Arduino Uno must then be configured to intercept this signal through the serial port chosen;

- The next step is to turned on the DL2C;

4.2.2. Synology and Visualization

5. Conclusion

References

- Fisher, D.K.; Kebede, H. A low-cost microcontroller-based system to monitor crop temperature and water status. Computers and electronics in agriculture 2010, 74, 168–173.

- Ansari, S.; Ayob, A.; Lipu, M.S.H.; Saad, M.H.M.; Hussain, A. A Review of Monitoring Technologies for Solar PV Systems Using Data Processing Modules and Transmission Protocols: Progress, Challenges and Prospects. Sustainability 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Gonzalez, J.; Infante-Alarcón, A.; Asanza, V.; Loayza, F.R. A 3D-Printed EEG based Prosthetic Arm. 2020 IEEE International Conference on E-health Networking, Application Services (HEALTHCOM), 2021, pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Calderón, A.J.; González, I.; Calderón, M.; Segura, F.; Andújar, J.M. A New, Scalable and Low Cost Multi-Channel Monitoring System for Polymer Electrolyte Fuel Cells. Sensors 2016, 16. [CrossRef]

- Liang, R.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, L.; Gao, Y. Real-time monitoring implementation of PV/T façade system based on IoT. Journal of Building Engineering 2021, 41, 102451. [CrossRef]

- González, I.; Calderón, A.J.; Figueiredo, J.; Sousa, J.M.C. A Literature Survey on Open Platform Communications (OPC) Applied to Advanced Industrial Environments. Electronics 2019, 8. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.J.; Wang, T.Z. Design of Temperature Control System Based on LabVIEW. Advances in Manufacturing Technology. Trans Tech Publications Ltd, 2012, Vol. 220, Applied Mechanics and Materials, pp. 808–811. [CrossRef]

- Mokhtar, Mukhlis, Ghazali, Abu Bakar, and Taat, Muhammad Zahidee. Development of Baby-EBM Interface System, 2010.

- Cenușă, M.; Poienar, M.; Milici, L.D.; Pața, S.D. Monitoring System for the EmotionalStates. International Conference on Advancements of Medicine and Health Care through Technology; 12th - 15th October 2016, Cluj-Napoca, Romania; Vlad, S.; Roman, N.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2017; pp. 85–88.

- Stój, J.; Smołka, I.; Maćkowski, M. Determining the Usability of Embedded Devices Based on Raspberry Pi and Programmed with CODESYS as Nodes in Networked Control Systems. Computer Networks; Gaj, P.; Sawicki, M.; Suchacka, G.; Kwiecień, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2018; pp. 193–205.

- Mansour, N.A.; El-Bab, A.M.R.F.; Abdellatif, M. Shape characterization of a multi-modal tactile display device for biomedical applications. 2012 First International Conference on Innovative Engineering Systems, 2012, pp. 7–12. [CrossRef]

- R. E. Rossel, Programming of the Wavelength Stabilization for a Titanium:Sapphire Laser using LabVIEW and Implementation into the CERN ISOLDE RILIS Measurement System, presented 15 Feb 2012 (Dec 2011). URL https://cds.cern.ch/record/1523721.

- Dixit, S.A.; Jain, A. Implementation of PPC-SSR as final control element and interfacing of PLC with LabVIEW using Modbus in two tank non interacting level control system. 2016 IEEE 1st International Conference on Power Electronics, Intelligent Control and Energy Systems (ICPEICES), 2016, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Bell, C. Beginning Sensor Networks with Arduino and Raspberry Pi; Apress, Berkeley, CA, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Krauss, R. Combining Raspberry Pi and Arduino to form a low-cost, real-time autonomous vehicle platform. 2016 American Control Conference (ACC), 2016, pp. 6628–6633. [CrossRef]

- Real-Time Interfacing Using the Arduino. In Exploring Raspberry Pi; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2016; chapter 11, pp. 453–480, [https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/9781119211051.ch11]. [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.H.; Fu, Y.T.; Ou, K.S.; Gu, D.; Pi, C.H.; Chen, K.S. On the development of autonomously manipulation of group mobile robots for smart living and biomimetic applications. 2012 IEEE International Conference on Computer Science and Automation Engineering (CSAE), 2012, Vol. 2, pp. 259–263. [CrossRef]

- Soriano, A.; Marín, L.; Vallés, M.; Valera, A.; Albertos, P. Low Cost Platform for Automatic Control Education Based on Open Hardware. IFAC Proceedings Volumes 2014, 47, 9044–9050. 19th IFAC World Congress, . [CrossRef]

- Mabbott, G.A. Teaching Electronics and Laboratory Automation Using Microcontroller Boards. Journal of Chemical Education 2014, 91, 1458–1463, . [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Santos, J.C.; Acevedo-Patino, O.; Contreras-Ortiz, S.H. Influence of Arduino on the Development of Advanced Microcontrollers Courses. IEEE Revista Iberoamericana de Tecnologias del Aprendizaje 2017, 12, 208–217. [CrossRef]

- Sobota, J.; PiŜl, R.; Balda, P.; Schlegel, M. Raspberry Pi and Arduino boards in control education. IFAC Proceedings Volumes 2013, 46, 7–12. 10th IFAC Symposium Advances in Control Education, . [CrossRef]

- James, A.E.; Chao, K.M.; Li, W.; Matei, A.; Nanos, A.G.; Stan, S.D.; Figliolini, G.; Rea, P.; Bouzgarrou, C.B.; Bratanov, D.; Cooper, J.; Wenzel, A.; Capelle, J.V.; Struckmeier, K. An Ecosystem for E-Learning in Mechatronics: The CLEM Project. 2013 IEEE 10th International Conference on e-Business Engineering, 2013, pp. 62–69. [CrossRef]

- Maiti, A.; Kist, A.A.; Maxwell, A.D. Real-Time Remote Access Laboratory With Distributed and Modular Design. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2015, 62, 3607–3618. [CrossRef]

- Blackstock, M.; Lea, R. Toward a Distributed Data Flow Platform for the Web of Things (Distributed Node-RED); Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2014; WoT ’14, p. 34–39. [CrossRef]

- Teikari, P.; Najjar, R.P.; Malkki, H.; Knoblauch, K.; Dumortier, D.; Gronfier, C.; Cooper, H.M. An inexpensive Arduino-based LED stimulator system for vision research. Journal of Neuroscience Methods 2012, 211, 227–236. [CrossRef]

- Ursutiu, D.; Samoila, C.; Jinga, V. Creative developments in LabVIEW student training: (Creativity laboratory — LabVIEW academy). 2017 4th Experiment@International Conference (exp.at’17), 2017, pp. 309–312. [CrossRef]

- Ursutiu, D., Samoila, C., Jinga, V., Altoe, F.. The future of hardware – software reconfigurable labview compiler to raspberry PI. Auer M.E.,Uhomoibhi J.,Guralnick D. [CrossRef]

- Buele, J.; Espinoza, J.; Pilatásig, M.; Silva, F.; Chuquitarco, A.; Tigse, J.; Espinosa, J.; Guerrero, L. Interactive System for Monitoring and Control of a Flow Station Using LabVIEW. Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Technology & Systems (ICITS 2018); Rocha, Á.; Guarda, T., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2018; pp. 583–592.

- Abdullah, A.; Ismael, A.; Rashid, A.; Abou-Elnour, A.; Tarique, M. Real Time Wireless Health Monitoring Application Using Mobile Devices. International journal of Computer Networks & Communications 2015, 7, 13–30. [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, M.; Manickum, O. Programming Arduino with LabVIEW; Community experience distilled, Packt Publishing, 2015.

- Tehami, S.; Khan, M.A.; Mazhar, O. Hardware and software designing of USB based plug n play data acquisition device with C and LabView compatibility. 2015 IEEE 21st International Symposium for Design and Technology in Electronic Packaging (SIITME), 2015, pp. 143–146. [CrossRef]

- Tong-on, A.; Saphet, P.; Thepnurat, M. Simple Harmonics Motion experiment based on LabVIEW interface for Arduino. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2017, 901, 012114. [CrossRef]

- Al-Arga, A.S.D. Liquid Level Control System with arduino Uno and Labview. Journal of Alasmarya University 2017, 2, 57–68.

- Mohanraj, K.; Balaji, N.; Chithrakkannan, R. IoT BASED PATIENT MONITORING SYSTEM USING RASPBERRY PI 3 and LabVIEW. 2017.

- Touati, F.; Al-Hitmi, M.; Chowdhury, N.A.; Hamad, J.A.; San Pedro Gonzales, A.J. Investigation of solar PV performance under Doha weather using a customized measurement and monitoring system. Renewable Energy 2016, 89, 564–577. [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar, R.; Alexander, T.; Subramoniam, M. Arduino Based Wireless Datalogger For Nuclear Power Plant Using Processing Software. 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Computing Research (ICCIC), 2017, pp. 1–4. [CrossRef]

- González, A.; Olazagoitia, J.L.; Vinolas, J. A low-cost data acquisition system for automobile dynamics applications. Sensors 2018, 18, 366.

- Bassous, G.F.; Calili, R.F.; Barbosa, C.H. Development of a low-cost data acquisition system for very short-term photovoltaic power forecasting. Energies 2021, 14, 6075.

- Caballero-Russi, D.; Ortiz, A.R.; Guzmán, A.; Canchila, C. Design and Validation of a Low-Cost Structural Health Monitoring System for Dynamic Characterization of Structures. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 2807.

- Fernández-Conde, J. A Low-Cost Hardware/Software Platform for Lossless Real-Time Data Acquisition from Imaging Spectrometers. Sensors 2023, 23, 4349.

- Özdemir, K.; Kömeç Mutlu, A. Cost-effective data acquisition systems for advanced structural health monitoring. Sensors 2024, 24, 4269.

- Haizad, M.; Ibrahim, R.; Adnan, A.; Chung, T.D.; Hassan, S.M. Development of low-cost real-time data acquisition system for process automation and control. 2016 2nd IEEE International Symposium on Robotics and Manufacturing Automation (ROMA). IEEE, 2016, pp. 1–5.

| Designation | Programming environment | Associated components |

|---|---|---|

| Algorithm 1 (Figure 8) | C | Arduino Nano |

| Algorithm 2 (Figure 9) | C | Arduino Uno |

| Algorithm 3 (Figure 10) | Python | Raspberry Pi |

| Algorithm 4 (Figure 13) | Linux | Raspberry Pi |

| Clock | Linux | DS1307 |

| Network | LabView ; SSH ; VNC . |

Raspberry Pi |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).