1. Introduction

Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MASLD), previously termed non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), is the most common chronic liver disease in children and adolescents worldwide. With a global epidemic of obesity and type 2 diabetes, pediatric MASLD is on the rise, thus posing a future critical issue for public health [

1]. While MASLD is often considered a benign condition, its progression to metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) involves inflammation and cell damage that can evolve into fibrosis, cirrhosis, and, in rare cases, hepatocellular carcinoma, even at a young age. Early identification of the factors driving this progression is crucial for the timely implementation of therapies and preventing severe long-term outcomes. It is known that pediatric patients with MASLD have an increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD), the leading cause of long-term morbidity and mortality. Despite the importance of the issue, early identification of children and adolescents with MASLD who are at higher risk of developing CVD is a clinical challenge [

2]. Conventional diagnostic methods for CV risk, such as the standard lipid profile, may not be sufficient to detect early signs of vascular dysfunction in this population. In this regard, the triglyceride (TG)/high-density lipoprotein (HDL) ratio has been suggested as a simple and inexpensive biomarker that reflects insulin resistance and atherogenic dyslipidemia [

3]. Several studies have demonstrated its usefulness in predicting CV risk in adults; however, its specific role in the pediatric population affected by MASLD needs further investigation [

4,

5]. Besides the TG/HDL ratio, serum homocysteine (Hcy) levels also appear as an additional reliable biomarker for assessing CVD risk in specific settings [

6]. Indeed, Hcy is a sulfur amino acid whose elevated levels have long been associated with endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and inflammation, all pathogenetic mechanisms that underlie liver disease progression and CVD risk [

7]. Hcy has been implicated in the pathogenesis of atherosclerotic complications in patients with metabolic syndrome, a condition that underlies the strong interplay between MASLD and CVD [

7]. However, even though hyperhomocysteinemia has been associated with MASLD and insulin resistance in adults, data on its role in pediatric MASLD and its association with CV risk in this population are limited [

8].

Hence, our study aimed to evaluate the association between the TG/HDL ratio, serum Hcy, and CV parameters in children and adolescents with MASLD, evaluating the predictive capacity of these biomarkers in predicting the progression of fibrotic damage.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

We enrolled 182 consecutive Caucasian children (mean age 10.89 years; 50% males), with an ultrasound diagnosis of steatosis and persistently elevated serum aminotransferase levels (≥ 6 months), who were referred to the Liver Unit of the Bambino Gesù Children’s Hospital (Rome, Italy) between January 2015 and March 2025. Following the novel nomenclature and consensus statements [

9], all these patients were categorized as MASLD because they had steatotic liver disease (SLD) and at least one of the cardiometabolic criteria without overlapping SLD diseases (e.g., Wilson’s disease, autoimmune hepatitis, α-1-antitrypsin deficiency, celiac disease, thyropathies, viral, genetic, and metabolic hepatitis, and alcohol and drug use). Of these patients, 89 with moderate/severe steatosis underwent liver biopsy for histopathological evaluation in accordance with ESPGHAN guidelines [

10].

2.2. Anthropometrical and Biochemical Parameters

Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters (kg/m²). Waist circumference was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using a non-elastic tape placed midway between the lower margin of the last palpable rib and the top of the iliac crest, at the end of a normal expiration. Blood pressure was measured in the right arm using a standard sphygmomanometer; the average of three values of systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) was reported. Elevated blood pressure was defined by systolic or diastolic values > 95th percentile for age, height, and sex. Venous blood samples were collected after fasting for at least 8 hours. The levels of serum liver enzymes (i.e., aspartate aminotransferase, AST; alanine aminotransferase, ALT; and gamma-glutamyltransferase, GGT), total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, triglycerides (TGs), and fasting blood glucose and insulin, and platelet count were measured in all patients using standard laboratory procedures at the Central Laboratory of the “Bambino Gesù” Children’s Hospital. Total Hcy levels were determined by high-performance liquid chromatography with fluorimetric detection as previously described [

8].

2.3. Biochemical Scores

The homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) was calculated by using the [glucose (mg/dL) * insulin (IU/mL)]/405, and a value greater than 2.5 was considered an index of insulin resistance [

11].

The TG/HDL ratio was calculated in all patients by using the following formula: TGs (mg/dL) ÷ HDL cholesterol (mg/dL). Values between 2 and 3 indicate a potential metabolic imbalance, while values > 3 indicate an elevated risk of CVD. This report is particularly useful for risk assessment in patients with MASLD, as it directly reflects the atherogenic dyslipidemia typical of this condition [

12].

2.4. Liver Ultrasound

The diagnosis of fatty liver disease was obtained by abdominal ultrasound performed by two experienced radiologists, unaware of the patients’ health conditions, using an Acuson Sequoia C512 ultrasound machine equipped with a 15L8 transducer (Universal Diagnostic Solutions, Oceanside, CA, USA). The brilliant hepatic ultrasound pattern was compared with the ultrasound response of the right kidney. The degree of hepatic steatosis was defined according to the following criteria: mild = 0, moderate = 1 and severe = 2.

2.5. Liver Biopsy

Eighty-nine children underwent liver biopsy, as per ESPGHAN guidelines [

9]. Liver biopsies were performed using an automatic 18 fr caliber biopsy needle, general anesthesia, and guided ultrasound. The characteristic histological features of MASH including, steatosis, lobular inflammation, ballooning hepatocytes, and fibrosis, were evaluated by a single experienced liver pathologist.

Each biopsy was evaluated centrally and independently read by two expert liver pathologists to assess NAS (NAFLD Activity Score) and fibrosis stage (according to NASH- Clinical Research Network CRN criteria). Hepatic fibrosis was quantified using a five-point grading: 0 = no fibrosis; 1 = perisinusoidal or periportal fibrosis; 2 = perisinusoidal/periportal portal fibrosis; 3 = fibrous bridge; 4 = cirrhosis [

13].

The presence of MASLD and MASH was defined according to the algorithm recently proposed by the Delphi consensus [

9]. MASH was defined as NAS ≥ 4 with at least one grade

in each category of histological features of MASH (i.e. steatosis, lobular inflammation, and ballooning) and fibrosis ≥1.

2.6. Assessment of Non-Invasive Fibrosis Scores

Two non-invasive fibrosis scores were evaluated, including AST/Platelet Ratio Index (APRI), and Fibrosis-4 Index for Liver Fibrosis (FIB-4) [

14]. In particular, the APRI was calculated as follow: ALT (U/L) /AST(U/L)*100/platelet count. While FIB-4 score was calculated as follows: age (years) × AST (U/L) / platelets (109/L) × √ALT (U/L).

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Data were expressed as means and standard deviations or as medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) or frequencies. The continuous variables were analyzed using the ANOVA test (when normally distributed) and the Mann–Whitney U test (when non-normally distributed). Pearson’s correlation test was used to evaluate the possible correlation between metabolic and histologic parameters, as well as one-carbon metabolism and cytokine levels. Spearman’s correlation coefficients were calculated to examine the invariable linear association. Subsequently, multivariate regression analysis was used to test the independent association of TG/HDL ratio and Hcy with metabolic parameters, as well as histological inflammation, fibrosis, and steatosis, after adjusting for potential confounders (i.e., age and sex). Covariates included in all regression models were selected as potential confounders based on their significance in univariate regression analyses or their biological plausibility.

Overall, the diagnostic accuracy of Hcy, TG/HDL ratio, APRI, and FIB-4 was calculated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. The area under the ROC (AUC) was compared, to predict liver fibrosis in MASH patients. The combined AUCs between Hcy and the markers and scoring system, and the distribution of the values in the form of Log10, was evaluated. Diagnostic performance was determined by sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value. A p-value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The data were analyzed by using GraphPad Prism 5.01 and MedCalc version 19.1.

3. Results

3.1. Assessment of Pathological Characteristics of Patients

A total of 182 children diagnosed with MASLD (age range 8.12-14 years) were enrolled in the study. Among them, 93 (51.1%) patients had mild SLD, while 89 (48.9%) had moderate-to-severe SLD as assessed by ultrasound. According to the established diagnostic criteria, the 89 patients with moderate-to-severe SLD underwent liver biopsy. Histological evaluation confirmed moderate-to-severe SLD without evidence of MASH in 23 patients and revealed histopathological features consistent with MASH in 66 patients (

Supplementary Table S1). These data allowed us to classify patients into three distinct groups: i) the Mild SLD group (N=93), ii) the All SLD group (N=116), which collectively includes patients with mild (N=93) and moderate-to-severe SLD (N=23) groups, iii) the MASH group (N=66). In these groups, we evaluated anthropometric and biochemical parameters, as well as the non-invasive fibrosis scores APRI and FIB-4.

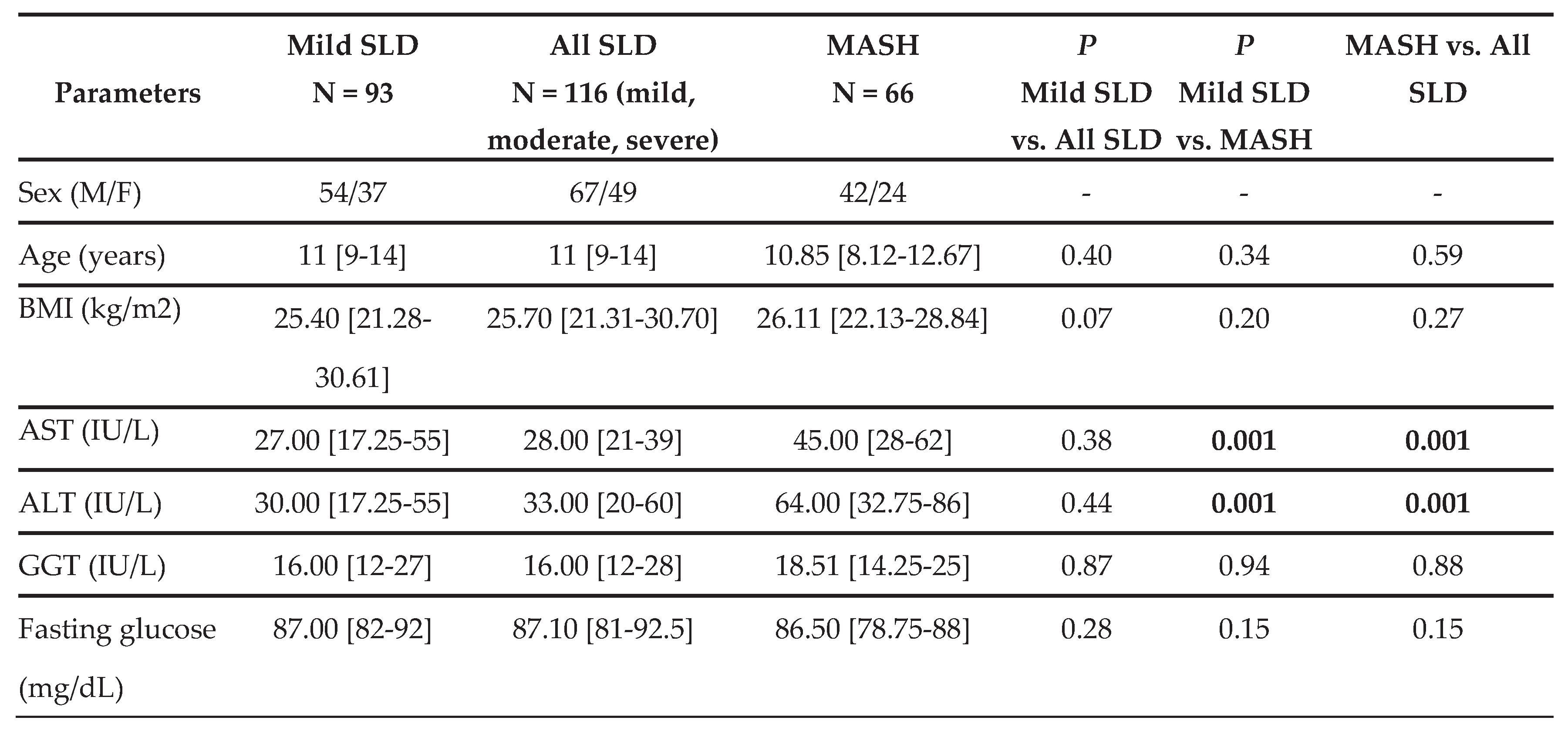

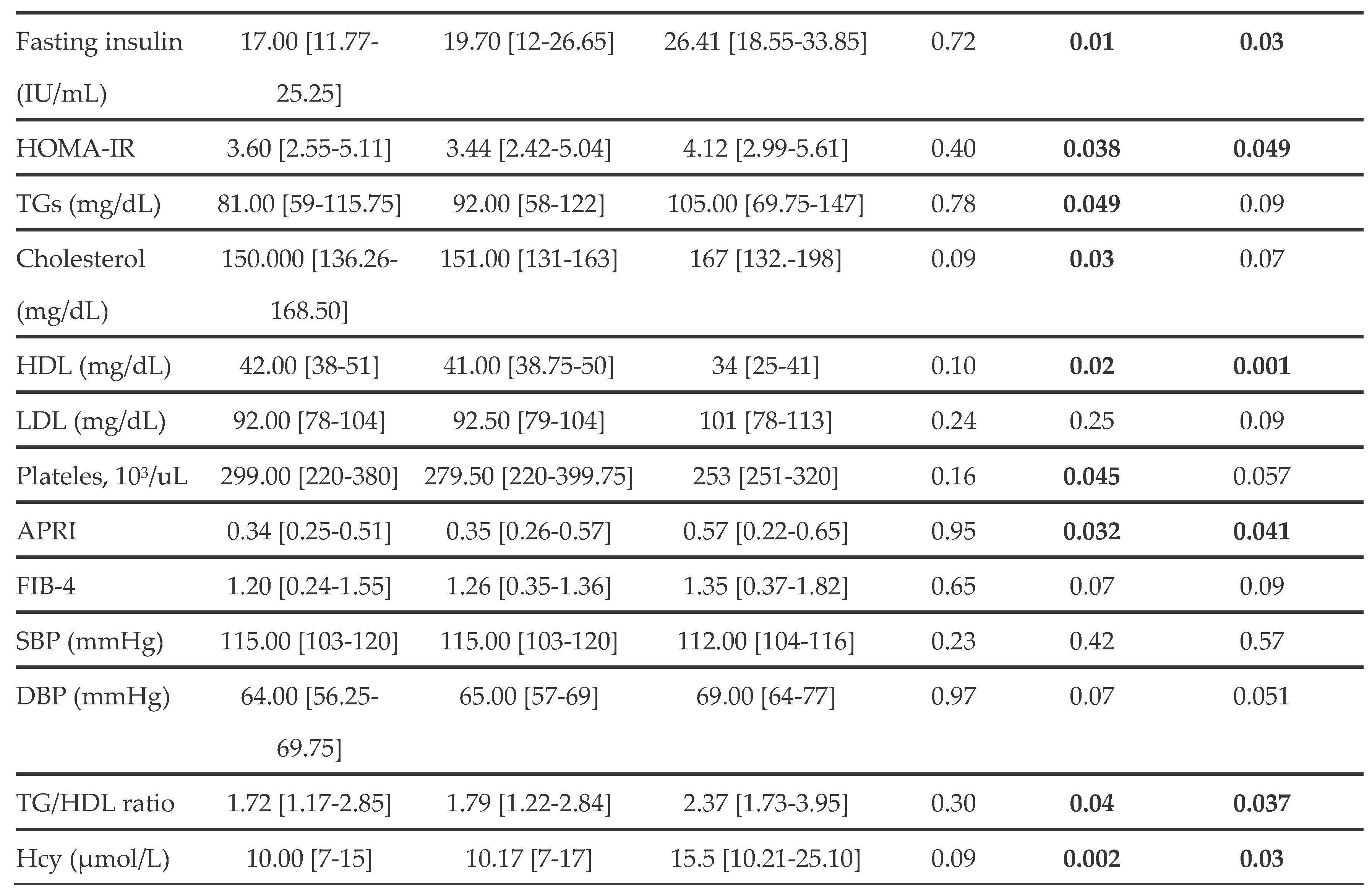

As shown in

Table 1, there are no statistically significant differences between Mild SLD and All SLD patients. Conversely, the MASH group showed statistically significant differences in various parameters compared to the SLD groups. Specifically, MASH patients had higher ALT, AST, insulin, and HOMA-IR values, as well as lower HDL levels, than the mild and all SLD groups. However, in the MASH group, TG and total cholesterol concentrations were significantly higher, and platelet counts were comparatively lower than those observed in the Mild SLD group.

Furthermore, patients with MASH had significantly higher APRI values than those in the SLD groups, whereas no significant differences were observed in FIB-4 indices.

Next, we evaluated CV parameters, including SBP, DBP, TG/HDL ratio, and Hcy levels. As reported in

Table 1, there were no statistically significant differences in SBP or DBP values among the groups. It is also noteworthy that a MASH diagnosis was associated with a higher TG/HDL ratio and higher Hcy levels than in the Mild and All SLD groups.

3.2. Correlations Between Hcy and Anthropometric and Metabolic Parameters, Non-Invasive Fibrosis Scores, and Histological Grading in Children with masld

The relationship between serum Hcy concentrations and parameters of cardiometabolic dysfunction, as well as non-invasive scores of liver fibrosis, were first evaluated in all patients with MASLD. As shown in

Table S2, Hcy levels were correlated positively with fasting insulin (r = 0.28, p = 0.04) and HOMA-IR (r = 0.31, p = 0.02), and negatively with HDL cholesterol (r = -0.38, p = 0.02). Furthermore, circulating levels of Hcy exhibited positive associations with APRI (r = 0.28, p = 0.03) and TG/HDL ratio (r = 0.43, p = 0.02).

Subsequently, to assess whether elevated Hcy concentration was associated with histopathological features of the advanced disease phenotype, we conducted Spearman correlation analyses in the subgroup of patients with MASH. In this patient’s subgroup (

Table 2), serum Hcy levels correlated positively with BMI (r = 0.22, p = 0.038), fasting insulin (r= 0.62, p = 0.008), HOMA-IR (r = 0.28, p = 0.006) and LDL (r = 0.45 p = 0.0011) and negatively with HDL (r = −0.34, p = 0.021). Noteworthy, increased levels of Hcy were significantly associated with the fibrosis index APRI, and the TG/HDL ratio (r = 0.23, p = 0.033; r = 0.53, p = 0.006), as well as with histological evidence of hepatic lobular inflammation and liver fibrosis (r = 0.24, p = 0.017; r = 0.28, p = 0.022).

To further clarify the relationship between serum concentrations of Hcy and the likelihood of developing MASH, a multivariate regression analysis was performed. As reported in

Table 3, after adjusting for age and sex, the model revealed that elevated Hcy levels were independently associated with HOMA-IR (β=0.55; SE= 0.31; p=0.049), with elevated TG/HDL ratio (β=3.23; SE= 0.94; p=0.002) and histological evidence of liver fibrosis (β=2.59; SE= 1.24; p=0.04). These results indicated that Hcy levels remain independently associated with cardiometabolic dysfunction and liver fibrosis.

Overall, these results suggest that elevated levels of Hcy may predict both cardiometabolik risk and the severity of liver disease in pediatric patients with MASLD.

3.3. Evaluation of the Fitness of Hcy Levels in Predicting Liver Fibrosis

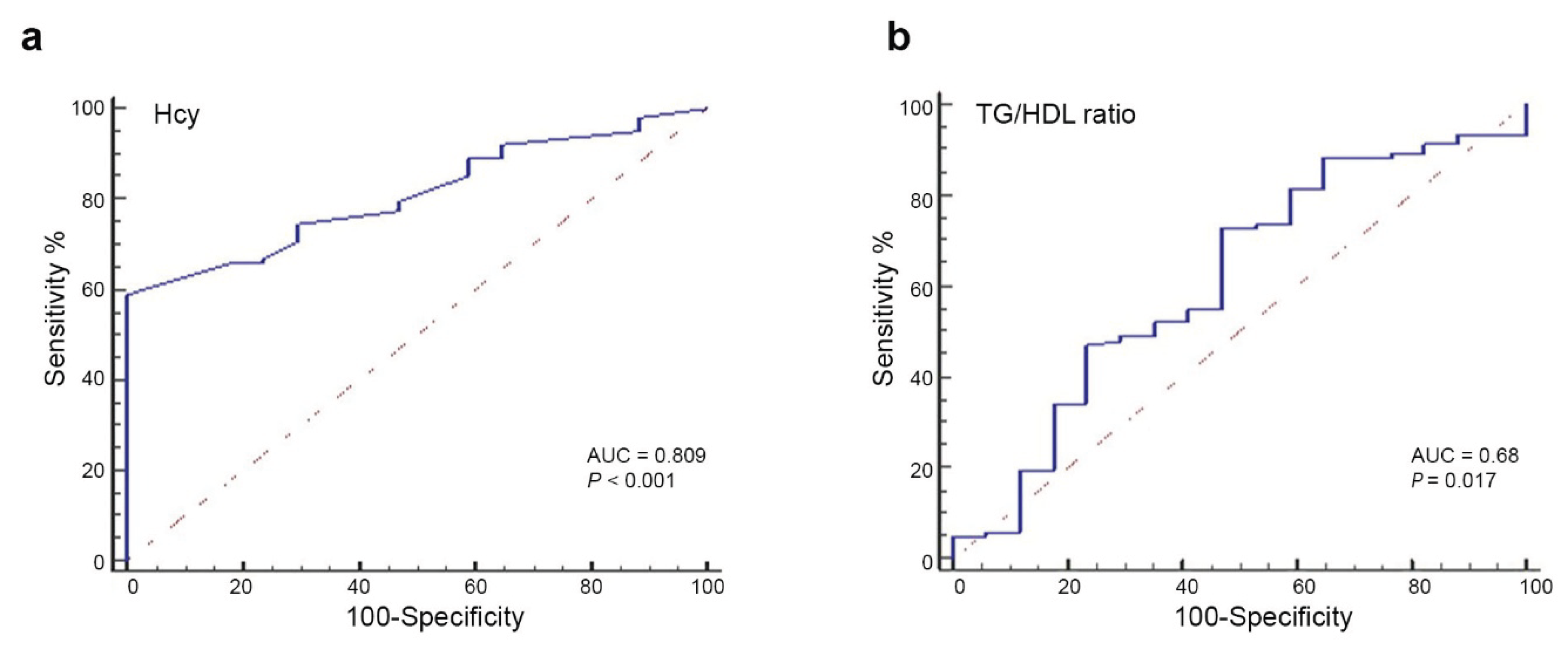

Next, we assessed the diagnostic accuracy of Hcy for predicting liver fibrosis in patients with MASH by calculating the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC). As shown in

Figure 1a, the AUC for Hcy in identifying patients with fibrosis was 0.809 (95% CI, 0.72–0.87; p = 0.0001). The analysis showed that, for values greater than 8, the sensitivity was 74.5% [95% CI, 65%-83%] and the specificity was 70.6% [95% CI, 44%-89%]. These findings suggest that elevated Hcy levels are a strong predictor of clinically relevant liver fibrosis in pediatric MASLD patients.

Conversely, the ROC analysis of TG/HDL ratio (

Figure 1b) to distinguish liver fibrosis showed an AUC of 0.68 (95% CI, 0.54–0.71; p = 0.017). Using values greater than 1.35, this parameter exhibited a sensitivity of 73.5% (95% CI, 63.8–81.8), and a specificity of 56.25% (95% CI, 30.0–80.2), indicating a poor/moderate discriminatory ability and a predictive performance lower than that of serum Hcy levels (

Figure 1b).

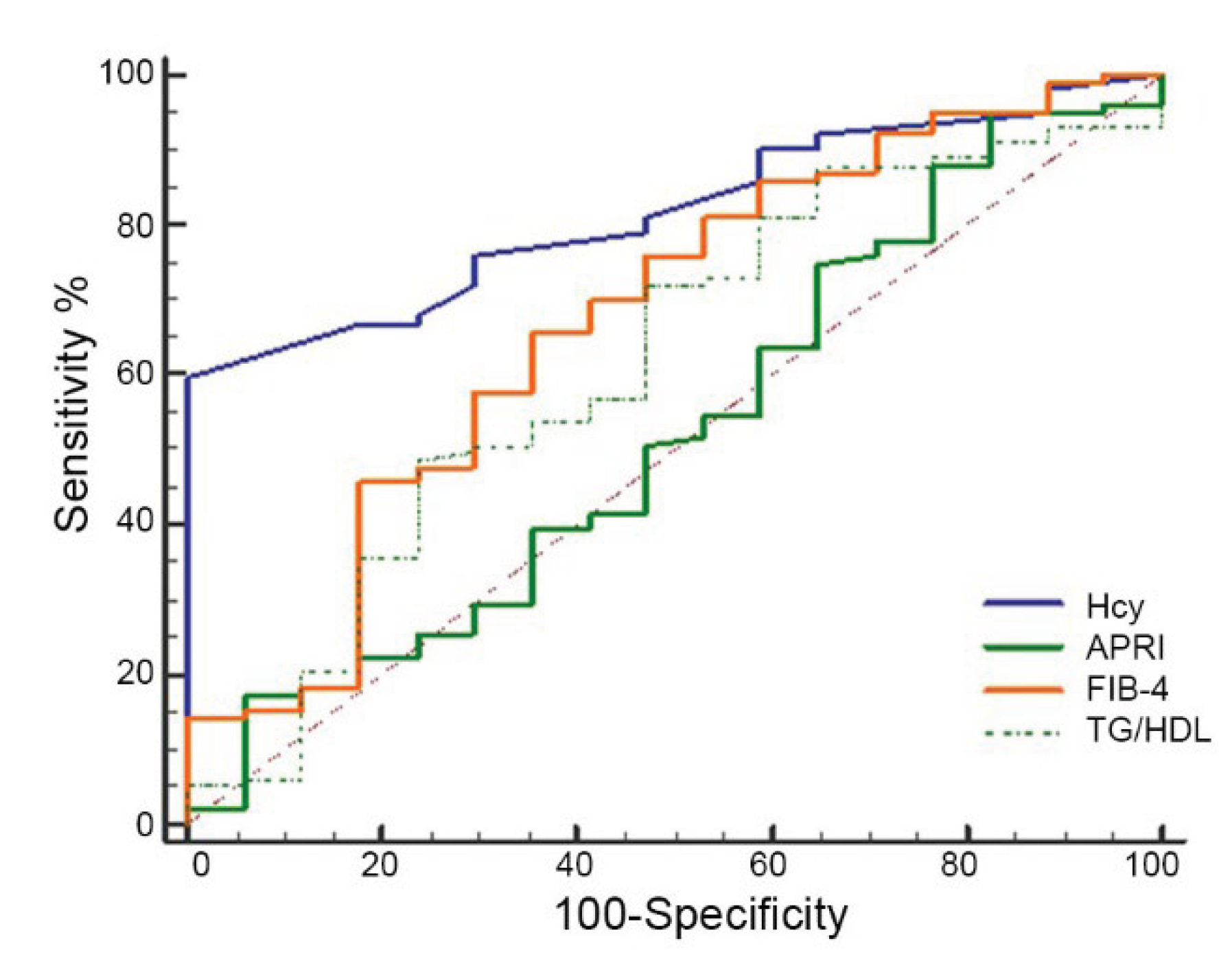

Next, we compared the predictive performance of Hcy values with the commonly used serum fibrosis scores and the TG/HDL ratio for predicting advanced fibrosis. In our subgroup of children with MASH, the ROC curves (

Figure 2) revealed that the AUC value of Hcy for predicting fibrosis was 0.82 (95% CI: 0.73–0.88; p = 0.0001). Conversely, the AUC values were 0.50 (95% CI: 0.41–0.59; p = 0.005) for APRI, 0.67 (95% CI: 0.57–0.75; p = 0.114) for FIB-4, and 0.63 (95% CI: 0.53–0.72; p = 0.034) for the TG/HDL ratio. Among the evaluated indicators, Hcy had the highest AUC value, demonstrating its greatest ability to discriminate between patients with and without liver fibrosis. Compared to Hcy, the predictive accuracy of APRI and the TG/HDL ratio was limited, and the FIB-4 did not reach statistical significance

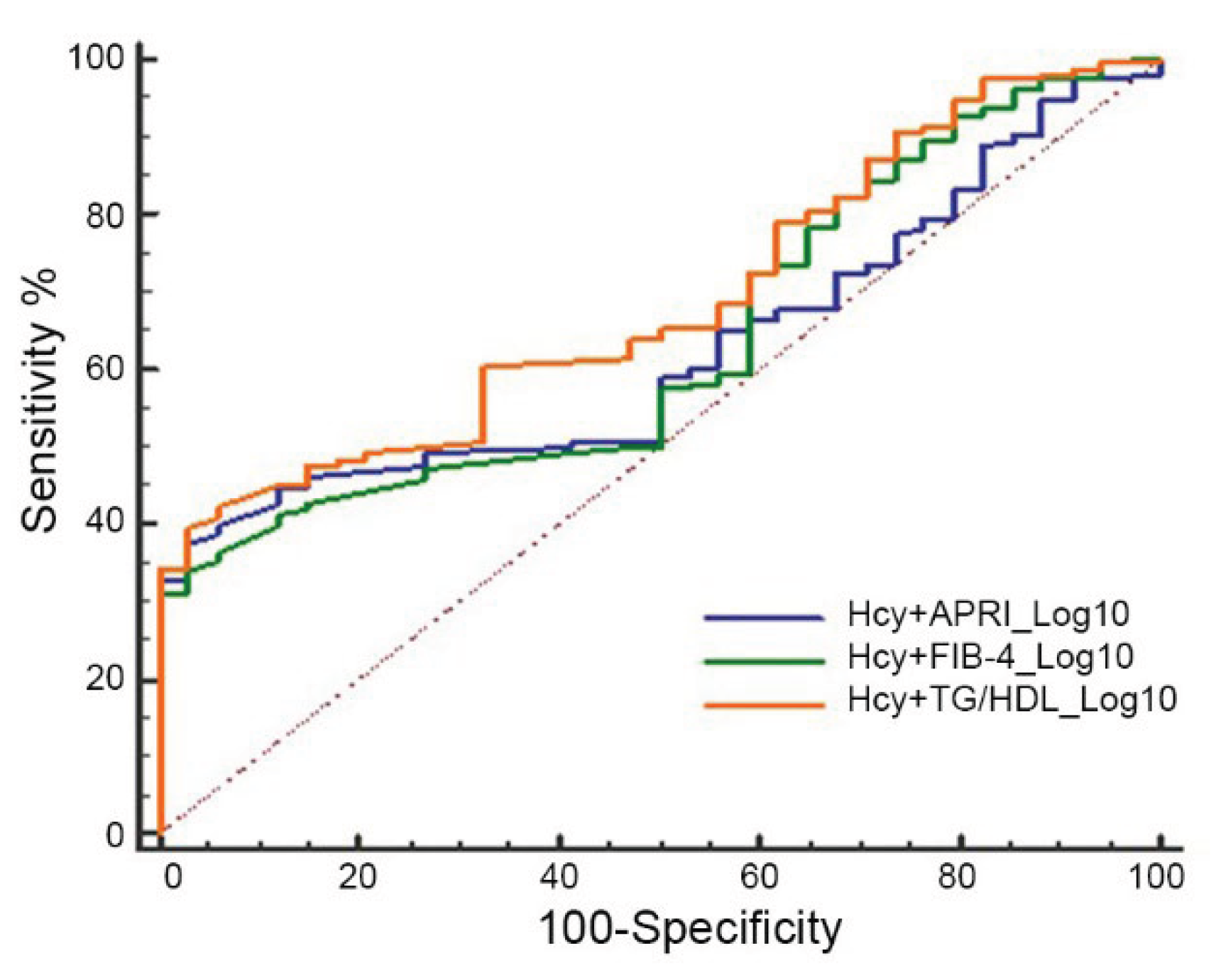

Finally, we evaluated the AUC of Hcy in combination with each of the other parameters including APRI, FIB-4, and TG/HDL ratio. Data reported in

Figure 3 showed an AUC of 0.62, (95% 0.55-0.68) for Hcy+APRI; an AUC of 0.63 (95%CI, 0.57-0.99) for Hcy+FIB-4, and an AUC of 0.69 (95% 0.62-0.74) for HCy+TG/HDL ratio, suggesting that combinations of Hcy with other non-invasive indexes for fibrosis and CV risk performed less well than Hcy alone.

4. Discussion

The increasing prevalence of MASLD in pediatric populations underscores the need for reliable non-invasive biomarkers to enable accurate disease staging, risk stratification for progression to severe forms such as MASH and liver fibrosis, and, in particular, differentiation of advanced fibrosis from mild stages. Our study revealed Hcy is an additional parameter for distinguishing SLD from MASH-related fibrosis in pediatric MASLD.

However, more importantly, our results suggest that hyperhomocysteinemia is not only an epiphenomenon but is closely intertwined with the metabolic alterations that characterize the progression from simple steatosis to MASH. Indeed, the association of Hcy with APRI and histological damage confirms that Hcy is an independent and accurate marker of significant liver fibrosis in patients with MASH compared to MASLD and SLD as we previously demonstrated in another pediatric cohort [

15]. The direct association between Hcy levels and the histological grade of lobular inflammation and fibrosis (grade >1) strengthens the hypothesis of its active role in the progression of liver damage [

20]. Hyperhomocysteinemia is known to promote endoplasmic reticulum stress, hepatocyte apoptosis, and activation of hepatic stellate cells, which are the key cellular events in the fibrogenetic process [

21].

The most clinically relevant finding from our study is the excellent diagnostic accuracy of Hcy as a non-invasive marker of fibrosis. With an AUC of 0.809, Hcy demonstrated a significantly superior performance compared to fibrosis scores commonly used in clinical and research settings. Moreover, we found that a threshold value > 8 μmol/L allows us to identify children with fibrosis, maintaining good sensitivity (74.5%) and specificity (70.6%). In our cohort, APRI (AUC=0.50) was completely ineffective, and FIB-4 (AUC=0.67) did not reach statistical significance, in line with other studies in pediatric cohorts [

22]. While the TG/HDL ratio, although associated with disease, showed modest accuracy with an AUC of 0.68 for fibrosis. The AUC for Hcy is comparable to the performance of GDF15 in assessing fibrosis in pediatric cohorts and highlights how both markers reflect the broad state of cellular and inflammatory stress that drives MASH progression [

23]. Comparing the diagnostic accuracy of Hcy obtained in our pediatric cohort with data in the literature relating to PRO-C3 (Propeptide of Type III Collagen), the most accurate marker for fibrosis in pediatric and adult MASLD (AUC > 0.80), Hcy showed similar or slightly lower performance [

24]. Therefore, Hcy provides an excellent alternative or complementary adjunct for initial risk stratification, given its excellent performance compared to routine biomarkers, such as APRI and FIB-4 [

22].

It is necessary to recognize some limitations of our work. Firstly, the cross-sectional design does not allow us to establish a definitive causal link between Hcy and MASLD progression, but only to highlight a strong association. Secondly, the study was conducted in a single hospital center, albeit highly specialized, and the results need validation in larger multicenter charts. Finally, no data were collected on factors known to influence Hcy levels, such as vitamin status (folate, B6, B12) or genetic polymorphisms of the MTHFR enzyme, which could be confounding factors. However, our study, using liver biopsy as the gold standard for a significant fraction of the cohort, provides robustness to our results [

25].

Overall, our findings suggest Hcy as a simple, cost-effective, and reliable screening tool to identify pediatric patients with MASLD at higher risk for advanced fibrosis [

26]. Therefore, this biomarker could be integrated into clinical practice to select patients who need more intensive monitoring or more in-depth evaluation, such as liver biopsy or elastography.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our data candidate Hcy as a non-invasive, robust, and reliable marker for fibrosis risk stratification in children with MASLD, surpassing some fibrosis scores currently used in the adult population in terms of accuracy. Its close correlation with the pillars of metabolic dysfunction suggests an active pathogenetic role. Further prospective longitudinal studies are warrented to confirm its predictive value over time and to explore whether interventions aimed at reducing hyperhomocysteinemia, such as vitamin supplementation, can modify the natural history of liver disease in children.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org, Table S1: Histological characteristics of the 89 patients with moderate-to-severe SLD; Table S2: Correlation analysis between Hcy and cardiometabolic parameters and fibrosis score in the children with MASLD.

Author Contributions

The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, A.M. and A.A.; methodology, G.A., L.D.V., M.R.B., P.F., and G.S.; formal analysis, A.M., L.D.V.; data curation, N.P., G.A., L.D.V., A.P. (Anna Pastore), M.R.B., L.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M, N.P., A.P. (Anna Pastore), L.M., P.F., and G.S..; writing—review and editing, A.M., N.P., and A.A., .; visualization, A.M., A.P. (Andrea Pietrobattista), and A.A .; supervision, A.M. and A.A; funding acquisition, A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

The Italian Ministry of Health supported this work with “Current Research funds”. This research was also funded by the European Union—Next Generation EU—NRRP M6C2—Investment 2.1 Enhancement and strengthening of biomedical research in the NHS (CUP number E83C22006360001).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Bambino Gesù Children’s Hospital Ethics Committee (protocol number PNRR-MAD-2022-12375633 on 1 February 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ALT |

Alanine aminotransferase, |

| APRI |

AST/Platelet Ratio Index |

| AST |

Aspartate aminotransferase, |

| BMI |

Body mass index |

| CVD |

Cardiovascular disease |

| DBP |

Diastolic blood pressure, |

| FIB-4 |

Fibrosis-4 index |

| GGT |

Gamma-glutamyltransferase |

| HDL |

High-density lipoprotein |

| IQR |

Interquartile range |

| LDL |

Low-density lipoprotein |

| HOMA-IR |

homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance |

| MASLD |

Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease |

| MASH |

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis |

| NAFLD |

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease |

| NAS |

NAFLD Activity score |

| SBP |

Systolic blood pressure |

| SLD |

Steatotic liver disease |

| TGs |

Triglycerides |

References

- Kanwal, F.; Neuschwander-Tetri, B.A.; Loomba, R.; Rinella, M.E. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: Update and impact of new nomenclature on the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases practice guidance on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2024, 79, 1212-1219. [CrossRef]

- Michalopoulou, E.; Thymis, J.; Lampsas, S.; Pavlidis, G.; Katogiannis, K.; Vlachomitros, D.; Katsanaki, E.; Kostelli, G.; Pililis, S., Pliouta, L.; et al. The Triad of Risk: Linking MASLD, Cardiovascular Disease and Type 2 Diabetes; From Pathophysiology to Treatment. J Clin Med. 2025, 14, 428. [CrossRef]

- Baneu, P.; Văcărescu, C.; Drăgan, S.R.; Cirin, L.; Lazăr-Höcher, A.I.; Cozgarea, A.; Faur-Grigori, A.A.; Crișan, S.; Gaiță, D.; Luca, C.T.; et al. The Triglyceride/HDL Ratio as a Surrogate Biomarker for Insulin Resistance. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1493. [CrossRef]

- Kosmas, C.E.; Rodriguez Polanco, S.; Bousvarou, M.D.; Papakonstantinou, E.J.; Peña Genao, E.; Guzman, E.; Kostara, C.E. The Triglyceride/High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol (TG/HDL-C) Ratio as a Risk Marker for Metabolic Syndrome and Cardiovascular Disease. Diagnostics (Basel) 2023, 13, 929. [CrossRef]

- Aydin, F.; Murat, B.; Murat, S.; Dağhan, H. TG/HDL-C Ratio as a Superior Diagnostic Biomarker for Coronary Plaque Burden in First-Time Acute Coronary Syndrome. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 2222. [CrossRef]

- Jakubowski, H.; Witucki, Ł. Homocysteine Metabolites, Endothelial Dysfunction, and Cardiovascular Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2025, 26, 746. [CrossRef]

- Piazzolla, G.; Candigliota, M.; Fanelli, M.; Castrovilli, A.; Berardi, E.; Antonica, G.; Battaglia, S.; Solfrizzi, V.; Sabbà, C.; Tortorella, C. Hyperhomocysteinemia is an independent risk factor of atherosclerosis in patients with metabolic syndrome. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2019, 11, 87. [CrossRef]

- Pastore, A.; Panera, N.; Mosca, A.; Caccamo, R.; Camanni, D.; Crudele, A.; De Stefanis, C.; Alterio, A.; Di Giovamberardino, G.; De Vito, R.; et al. Changes in Total Homocysteine and Glutathione Levels After Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy in Children with Metabolic-Associated Fatty Liver Disease. Obes Surg. 2022, 32, 82-89. [CrossRef]

- Rinella, M.E.; Lazarus, J.V.; Ratziu, V.; Francque, S.M.; Sanyal, A.J.; Kanwal, F.; Romero, D.; Abdelmalek, M.F.; Anstee, Q.M.; Arab, J.P. et al. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. J Hepatol. 2023, 79, 1542-1556. [CrossRef]

- European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN); European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL); North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (NASPGHAN); Latin-American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (LASPGHAN); Asian Pan-Pacific Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (APPSPGHAN); Pan Arab Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition (PASPGHAN); Commonwealth Association of Paediatric Gastroenterology & Nutrition (CAPGAN); Federation of International Societies of Pediatric Hepatology, Gastroenterology and Nutrition (FISPGHAN). Paediatric steatotic liver disease has unique characteristics: A multisociety statement endorsing the new nomenclature. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2024, 78, 1190-1196. [CrossRef]

- Sugiura, M.; Nakamura, M.; Ikoma, Y.; Yano, M.; Ogawa, K.; Matsumoto, H.; Kato, M.; Ohshima, M.; Nagao, A. The homeostasis model assessment-insulin resistance index is inversely associated with serum carotenoids in non-diabetic subjects. J Epidemiol. 2006, 16, 71-78. [CrossRef]

- Kosmas, C.E.; Rodriguez Polanco, S.; Bousvarou, M.D.; Papakonstantinou, E.J.; Peña Genao, E.; Guzman, E.; Kostara, C.E. The Triglyceride/High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol (TG/HDL-C) Ratio as a Risk Marker for Metabolic Syndrome and Cardiovascular Disease. Diagnostics (Basel), 2023, 13, 929. [CrossRef]

- Kleiner, D.E.; Brunt, E.M.; Van Natta, M.; Behling, C.; Contos, M.J.; Cummings, O.W.; Ferrell, LD.; Liu, Y.C.; Torbenson, M.S.; Unalp-Arida, A. et al. Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network. Design and validation of a histological scoring system for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2005, 41:1313-21.

- Li, W.; Jiang, L.; Li, M.; Lin, C.; Zhu, L.; Zhao, B.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, S.; et al. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease is associated with the risk of severe liver fibrosis in pediatric population. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2025, 13, goaf056. [CrossRef]

- Pastore, A.; Alisi, A.; di Giovamberardino, G.; Crudele, A.; Ceccarelli, S.; Panera, N.; Dionisi-Vici, C.; Nobili, V. Plasma levels of homocysteine and cysteine increased in pediatric NAFLD and strongly correlated with severity of liver damage. Int J Mol Sci. 2014, 15, 21202-14. [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Chen, T.; Zhou, F.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Zhao, W.; Li, Y.; Shi, Y.; Niu, K.; et al. The association between different insulin resistance surrogates and all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality in patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2025, 24, 200. [CrossRef]

- Koklesova, L.; Mazurakova, A.; Samec, M.; Biringer, K.; Samuel, S.M.; Büsselberg, D.; Kubatka, P.; Golubnitschaja, O. Homocysteine metabolism as the target for predictive medical approach, disease prevention, prognosis, and treatments tailored to the person. EPMA J. 2021, 12, 477-505. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Qu, Y.Y.; Liu, L.; Qiao, Y.N.; Geng, H.R.; Lin, Y.; Xu, W.; Cao, J.; Zhao, J.Y. Homocysteine inhibits pro-insulin receptor cleavage and causes insulin resistance via protein cysteine-homocysteinylation. Cell Rep. 2021, 37, 109821. [CrossRef]

- Verdile, G.; Keane, K.N.; Cruzat, V.F.; Medic, S.; Sabale, M.; Rowles, J.; Wijesekara, N.; Martins, R.N.; Fraser, P.E.; Newsholme, P. Inflammation and Oxidative Stress: The Molecular Connectivity between Insulin Resistance, Obesity, and Alzheimer’s Disease. Mediators Inflamm. 2015, 2015, 105828. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Guan, Y.; Yang, X.; Xia, Z.; Wu, J. Association of Serum Homocysteine Levels with Histological Severity of NAFLD. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2020, 29, 51-58. [CrossRef]

- Lv, D.; Wang, Z.; Ji, S.; Wang, X.; Hou, H. Plasma Levels of Homocysteine is Associated with Liver Fibrosis in Health Check-Up Population. Int J Gen Med. 2021, 14, 5175-5181. [CrossRef]

- Mosca, A.; Della Volpe, L.; Alisi, A.; Veraldi, S.; Francalanci, P.; Maggiore G. Non-Invasive Diagnostic Test for Advanced Fibrosis in Adolescents With Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Front Pediatr. 2022, 10:885576. [CrossRef]

- Mosca, A.; Braghini, M.R.; Andolina, G.; De Stefanis, C.; Cesarini, L.; Pastore, A.; Comparcola, D.; Monti, L.; Francalanci, P.; Balsano, C. et al. Levels of Growth Differentiation Factor 15 Correlated with Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease in Children. Int J Mol Sci. 2025, 26, 6486. [CrossRef]

- Mosca, A.; Mantovani, A.; Crudele, A.; Panera, N.; Comparcola, D.; De Vito, R.; Bianchi, M.; Byrne, C.D.; Targher G., Alisi, A. Higher Levels of Plasma Hyaluronic Acid and N-terminal Propeptide of Type III Procollagen Are Associated With Lower Kidney Function in Children With Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Front Pediatr. 2022, 10, 917714. [CrossRef]

- Ovchinsky, N.; Moreira, R.K.; Lefkowitch, J.H.; Lavine, J.E. Liver biopsy in modern clinical practice: a pediatric point-of-view. Adv Anat Pathol. 2012, 19, 250-262. [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Yoon, E.L.; Kim, M.; Park, J.H.; Cheung, R.; Cho, J.Y.; Kim, H.L.; Jun, D.W. Cost-effectiveness of advanced hepatic fibrosis screening in individuals with suspected MASLD identified by serologic noninvasive tests. Sci Rep. 2025, 15, 24186. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).