Introduction

Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD), formerly termed non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), is among the most prevalent chronic liver diseases, affecting roughly one in four adults globally [

1,

2]. The MAFLD nomenclature emphasizes positive diagnostic criteria anchored in metabolic dysfunction—rather than exclusion of secondary causes—reflecting contemporary understanding of its pathobiology and improving case ascertainment across clinical settings [

3]. MAFLD clusters with obesity, insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and other components of the metabolic syndrome, and contributes substantially to hepatic and extrahepatic morbidity [

4,

5].

Beyond liver-related outcomes, MAFLD is consistently associated with elevated risks of major adverse cardiovascular events, chronic kidney disease, and certain cancers, translating into increased all-cause and cardiovascular mortality [

6,

7,

8,

9]. The metabolic multimorbidity that accompanies MAFLD—hypertension, dyslipidemia, T2DM—appears to be a principal driver of disease progression and adverse outcomes, underscoring the need for systematic comorbidity profiling and integrated care pathways [

10,

11]. Contemporary evidence suggests that cardiometabolic risk stratification should be embedded within hepatology workflows to optimize prevention and management.

Diagnostic approaches span invasive and non-invasive modalities. While liver biopsy remains the reference standard for histological grading and staging, its use is constrained by cost, sampling variability, and procedural risks [

12]. In routine practice, ultrasonography is widely adopted for steatosis detection due to accessibility, albeit with reduced sensitivity for mild steatosis and operator dependence [

13,

14]. International societies advocate standardized diagnostic criteria and stepwise risk stratification using non-invasive tests (NITs)—for example, serum-based scores (FIB-4, NAFLD fibrosis score) and elastography—to identify patients at risk of advanced fibrosis who require specialist care [

15,

16].

In the Russian Federation, the burden of MAFLD mirrors global trends in obesity and metabolic syndrome, with emerging data suggesting distinctive clinical phenotypes and comorbidity patterns [

17,

18,

19]. Prior regional studies have reported high rates of metabolic syndrome, frequent multimorbidity, and potential influences of genetic and lifestyle factors on disease expression [

18,

19]. However, much of the available evidence—both globally and within Russia—has focused on isolated risk factors or selected subgroups, with relatively few large, real-world cohort analyses comprehensively comparing clinical characteristics and comorbidity profiles between individuals with and without MAFLD [

20,

21].

Accordingly, we conducted a retrospective cohort study in a tertiary care setting to compare demographic characteristics, clinical parameters, and metabolic and gastrointestinal comorbidities in adults with versus without MAFLD. MAFLD diagnosis was established using ultrasonography and, when available, liver biopsy confirmation, enabling robust assessment of steatosis and its relationship with metabolic burden. By integrating international and local perspectives, this study aims to refine comorbidity profiling in MAFLD and inform hepatology practice through data-driven risk stratification and targeted management strategies.

Methods

Study Design and Population

This investigation applied a retrospective cohort design including 850 adult patients, comprising 432 individuals with MAFLD and 418 individuals without MAFLD, identified within a tertiary care center. Demographic characteristics, anthropometric measures, clinical parameters, and comorbidities were evaluated and contrasted between groups using a prespecified analytic framework. The diagnosis of MAFLD was ascertained by imaging, primarily ultrasonography, and, in selected cases, histopathological assessment of liver biopsy specimens. The severity of hepatic steatosis was graded on ultrasonography using conventional sonographic criteria and, when available, corroborated by histological grading. This dual-modality approach was used to improve classification accuracy for MAFLD and to enhance precision in grading steatosis severity. A standardized data model and analysis plan were implemented prior to data extraction to ensure consistency and reproducibility across all analytic steps.

Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion criteria were adult age (≥18 years) and availability of complete clinical, laboratory, and imaging data necessary to classify hepatic steatosis and ascertain comorbidity status. Exclusion criteria comprised: (1) significant alcohol intake exceeding 30 g/day for men or 20 g/day for women; (2) viral hepatitis (HBV or HCV) as documented by serology and/or ICD-10 coding; (3) other chronic liver diseases, including autoimmune, genetic, or drug-induced etiologies; (4) pregnancy; and (5) incomplete or missing key variables required for exposure, outcome, or covariate definitions. Following application of these criteria and deduplication procedures, 850 unique patients were included in the final analytic cohort. Control patients were identified from the same source population and matched for age and sex to minimize confounding by these fundamental demographic variables; controls lacked radiological or clinical evidence of fatty liver disease. Completeness thresholds for analytic inclusion were defined a priori for laboratory and imaging fields to reduce bias introduced by missingness; remaining missing data patterns were assessed and documented (see Statistical and AI Methods).

Diagnostic Standards

Hepatic steatosis was first assessed by ultrasonography according to established sonographic features, including increased hepatic echogenicity relative to the renal cortex, blurring of vascular margins, and posterior (deep) beam attenuation [

2,

24]. Where clinically indicated, percutaneous liver biopsy was performed to confirm the presence of steatosis and to permit histopathological grading of disease severity [

25,

26]. Radiological reports were reviewed for explicit steatosis grading (e.g., mild, moderate, severe) where available; in the absence of explicit grading, anchor descriptors from reports were mapped to ordinal grades using a prespecified rubric aligned to typical ultrasonographic criteria. Histological assessments, when available, were used to corroborate ultrasonographic grading and to validate the presence and extent of steatosis. MAFLD was defined by imaging evidence of hepatic steatosis (ultrasonography or computed tomography) in addition to one of the following: overweight/obesity (body mass index ≥25 kg/m²), type 2 diabetes mellitus, or evidence of metabolic dysregulation (defined by at least two metabolic risk abnormalities: increased waist circumference, hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia, low HDL cholesterol, prediabetes, insulin resistance, or elevated high-sensitivity C-reactive protein). Controls, frequency-matched on age and sex as described above, demonstrated no radiological or clinical evidence of fatty liver disease and were required to pass the same exclusion criteria as applied to the MAFLD group.

Comorbidity Definitions

Comorbidities were identified by integrating ICD-10 diagnostic codes, laboratory thresholds, and clinician-documented diagnoses within the EHR. Hypertension was defined by a documented diagnosis or a blood pressure measurement ≥140/90 mmHg. Type 2 diabetes mellitus was defined by ICD-10 coding, fasting plasma glucose ≥7.0 mmol/L, or HbA1c ≥6.5%. Dyslipidemia was defined by any of the following: total cholesterol ≥5.2 mmol/L, LDL cholesterol ≥3.4 mmol/L, triglycerides ≥1.7 mmol/L, or prescription of lipid-lowering therapy. Additional comorbidities, including chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular disease, were identified using established diagnostic codes and widely accepted clinical criteria [

27,

28]. Where possible, comorbidity ascertainment required confirmation from more than one data source (e.g., code plus laboratory threshold or medication), and time stamps were used to ensure that comorbidities were present during the window relevant to MAFLD classification. Consistency checks were implemented to harmonize overlapping diagnostic labels and to prevent double-counting of related conditions.

Statistical and AI Methods

Continuous variables were described as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median with interquartile range (IQR), conditional on distributional characteristics verified by inspection of histograms and the Shapiro–Wilk test for normality. Categorical variables were summarized as counts and percentages. Between-group comparisons employed Student’s t-test for normally distributed continuous variables or the Mann–Whitney U test otherwise, and chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables. Homogeneity of variances was assessed (e.g., Levene’s test) to confirm test assumptions; where violated, Welch’s correction was applied for t-tests. Associations between MAFLD status and comorbidities were estimated using multivariable logistic regression, with odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) presented [

29]. Covariate adjustment included a prespecified set of demographic and clinical variables chosen based on subject-matter knowledge and potential confounding. Model diagnostics encompassed evaluation of multicollinearity using variance inflation factors, assessment of influential observations, calibration (e.g., Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit), and discrimination using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve where applicable. Where missingness was limited and plausibly random, complete-case analysis was applied; for variables with non-negligible missingness, sensitivity analyses using multiple imputation were conducted to evaluate robustness of inferences. Two-sided statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. All primary analyses were performed using SPSS version 26.0, and reproducible analytic scripts were implemented in Python for complementary analyses.

Artificial intelligence (AI)–based analytical methods were applied to explore non-linear relationships, enhance variable selection, and evaluate the stability of predictors in relation to MAFLD status and comorbidity burden [

30]. Candidate algorithms included regularized logistic regression (e.g., L1-penalized), ensemble tree-based methods (e.g., random forest), and gradient boosting approaches. Feature importance rankings were used to corroborate effect patterns observed in conventional regression models. Hyperparameters were tuned via grid or randomized search within cross-validation folds to mitigate overfitting. Internal validation relied on k-fold cross-validation with stratification by outcome to preserve class balance; model performance was summarized using discrimination metrics (area under the receiver operating characteristic curve), calibration plots, and, where applicable, precision–recall analysis in the presence of class imbalance. Concordance between AI-derived importance profiles and adjusted regression estimates was examined to support convergent validity of identified predictors.

Ethical Considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and received ethical approval from the Local Ethics Committee of I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University, Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation (Sechenov University). The study protocol was approved under Extract from Protocol No. 27-24 following a meeting dated 07.11.2024, with discussions and voting executed via electronic means. Owing to the retrospective design and exclusive use of de-identified data, the requirement for informed consent was waived [

31].

Results

Patient Characteristics

A total of 850 patients were included in the analysis, comprising 432 patients with MAFLD and 418 without. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population are summarized in

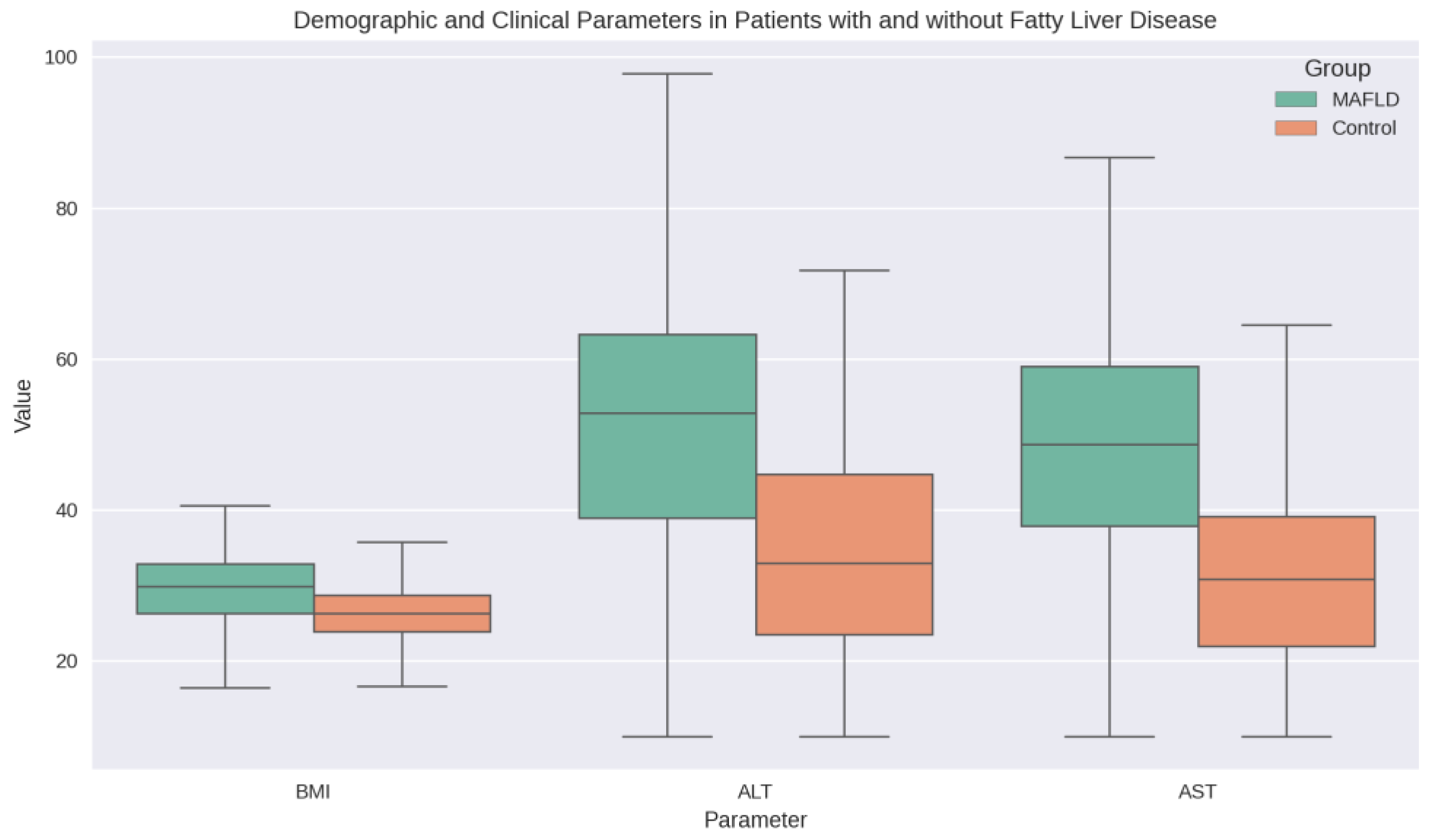

Table 1. There was no significant difference in age between the MAFLD and non-MAFLD groups (53.31 ± 20.53 vs. 52.81 ± 20.02 years, p = 0.722). However, patients with MAFLD had significantly higher BMI compared to those without (29.71 ± 4.62 vs. 26.25 ± 3.90 kg/m², p < 0.001). Liver function tests, including ALT (52.01 ± 18.53 vs. 34.05 ± 14.56 U/L, p < 0.001) and AST (48.12 ± 15.64 vs. 31.21 ± 12.70 U/L, p < 0.001), were significantly elevated in the MAFLD group

Figure 1 illustrates the demographic and clinical parameters of patients with and without fatty liver disease, highlighting the significant differences in BMI and liver enzymes between the two groups.

Comorbidity Associations

Analysis of comorbid conditions revealed that Type 2 Diabetes and dyslipidemia were significantly more prevalent in patients with MAFLD (

Table 2). Specifically, the prevalence of Type 2 Diabetes was 49.3% in the MAFLD group compared to 35.9% in the non-MAFLD group (OR 1.74, 95% CI 1.32–2.29, p < 0.001). Dyslipidemia was noted in 69.0% of patients with MAFLD versus 42.3% in those without (OR 3.03, 95% CI 2.29–4.01, p < 0.001).

Other comorbidities, including hypertension (49.5% vs. 51.2%, p = 0.678), chronic pancreatitis (47.2% vs. 48.6%, p = 0.747), and GERD (53.2% vs. 51.4%, p = 0.647), did not differ significantly between the groups.

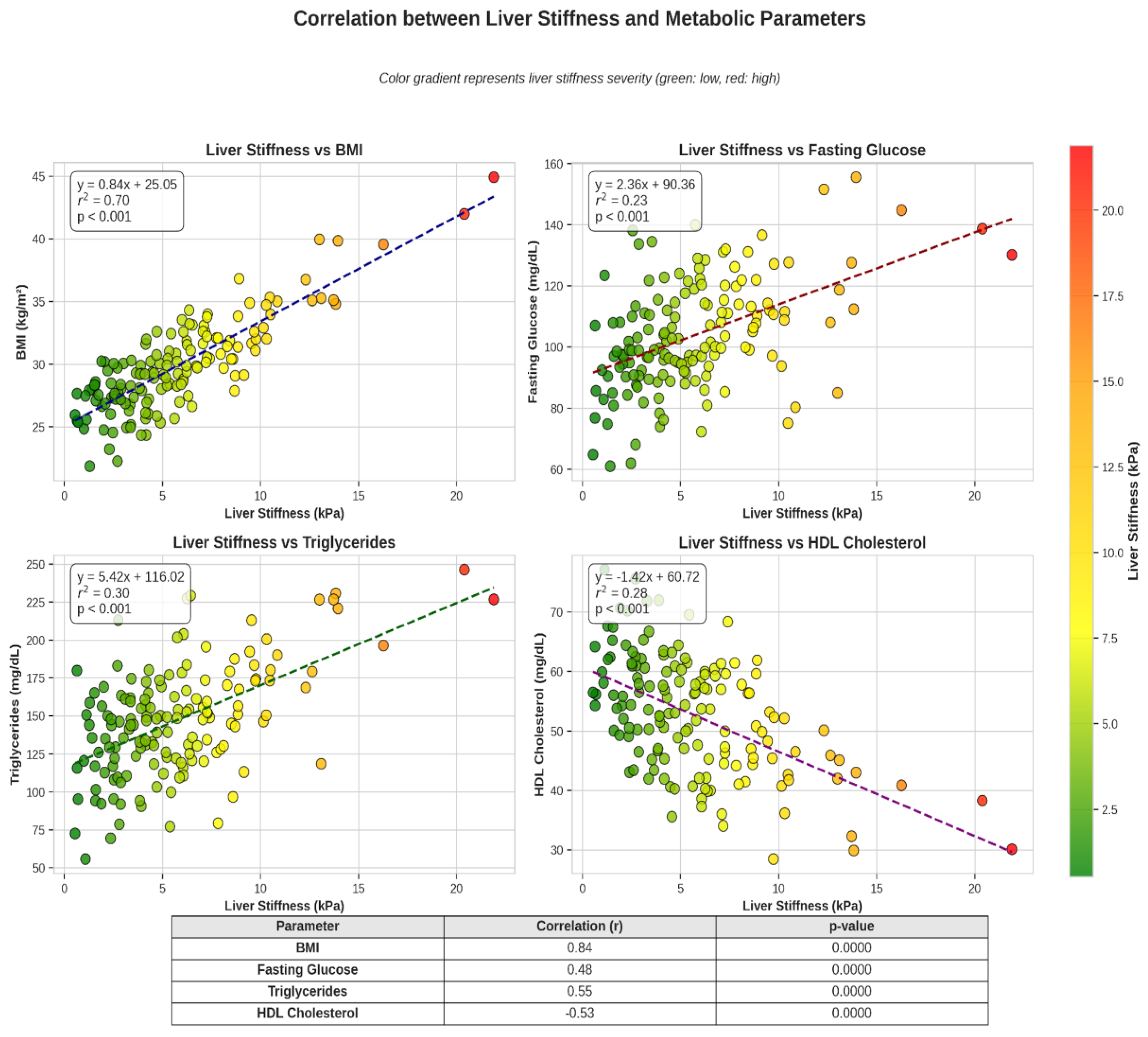

Figure 2.

Correlation between liver stiffness and metabolic parameters: Scatter/heatmap panels show that increasing liver stiffness (or fibrosis proxies) corresponds with adverse metabolic profiles (higher BMI, HbA1c, triglycerides, and lower HDL); fitted lines with confidence bands indicate positive trends and the degree of association.

Figure 2.

Correlation between liver stiffness and metabolic parameters: Scatter/heatmap panels show that increasing liver stiffness (or fibrosis proxies) corresponds with adverse metabolic profiles (higher BMI, HbA1c, triglycerides, and lower HDL); fitted lines with confidence bands indicate positive trends and the degree of association.

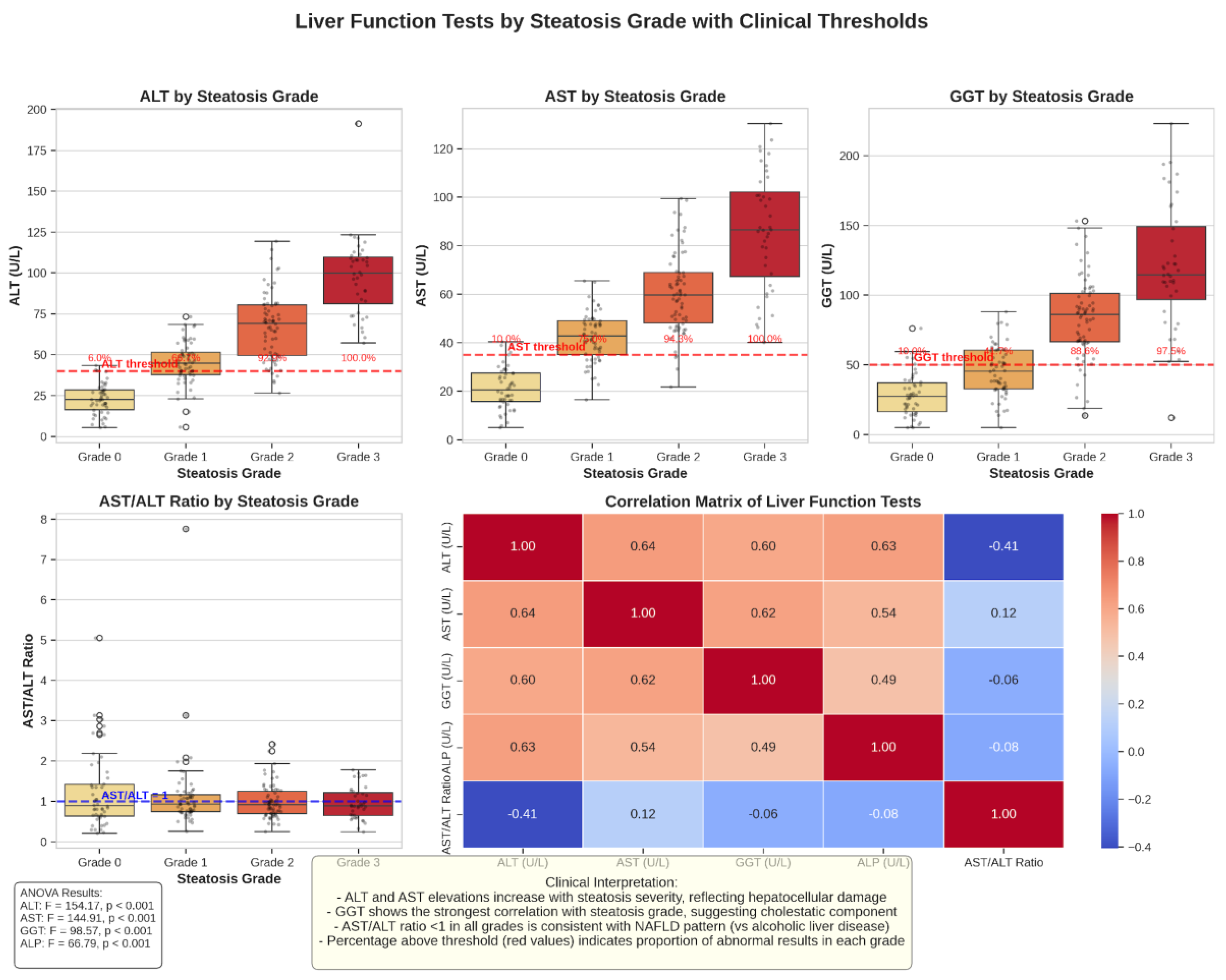

Liver Function Tests by Steatosis Grade

Liver function tests demonstrated a progressive deterioration with advancing steatosis grade (

Figure 4). ALT, AST, and GGT levels increased significantly from Grade 1 to Grade 3 steatosis (p < 0.001 for all comparisons). The AST/ALT ratio remained below 1 across all steatosis grades, consistent with the pattern typically observed in MAFLD rather than alcoholic liver disease. The proportion of patients with abnormal liver function tests (above the upper limit of normal) also increased with steatosis severity, with Grade 3 steatosis showing the highest rates of liver enzyme elevations.

Discussion

This comprehensive analysis of 850 patients provides detailed insights into the clinical and comorbidity profile of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) within a tertiary care environment. A dual diagnostic strategy—initial ultrasonography followed by confirmatory liver biopsy in clinically indicated cases—was employed to enhance diagnostic accuracy and enable assessment of histological severity where feasible. The principal findings demonstrate robust associations between MAFLD and metabolic comorbidities, notably type 2 diabetes mellitus and dyslipidemia, whereas hypertension, GERD, and chronic pancreatitis did not differ significantly by MAFLD status. A graded relationship was observed whereby advancing steatosis severity paralleled a higher burden of metabolic comorbidities and worsening liver biochemistry.

The strong association between MAFLD and metabolic comorbidities is consistent with the recognition of MAFLD as a systemic metabolic condition [

4]. The higher prevalence of type 2 diabetes and dyslipidemia in MAFLD underscores the interdependence of hepatic steatosis and cardiometabolic risk, aligning with the concept of metabolic multimorbidity as a key driver of adverse outcomes. The observed prevalence of type 2 diabetes in the MAFLD cohort (49.3% vs. 35.9% in non-MAFLD) exceeds reported ranges in several Western European cohorts (approximately 40–45%) [

22,

33], suggesting potential regional differences in risk exposure and susceptibility. Possible contributors include dietary composition, physical activity patterns, access to and uptake of preventive care, and population-specific genetic backgrounds that modulate insulin resistance and lipid handling. Health system factors, including thresholds for referral to tertiary care and diagnostic intensity, may also influence the measured comorbidity prevalence.

The diagnostic framework prioritized ultrasonography for case identification due to accessibility and cost-effectiveness, complemented by liver biopsy in selected cases to secure histological confirmation and staging. While ultrasonography reliably detects moderate-to-severe steatosis, it exhibits reduced sensitivity for mild steatosis and cannot differentiate simple steatosis from steatohepatitis [

12,

40]. Incorporation of biopsy data provided definitive characterization in a subset, addressing limitations inherent to imaging alone and enabling a more precise appraisal of disease severity and associated hepatic changes [

29]. This dual-modality approach likely improved specificity of classification and reduced misclassification bias, particularly in patients with borderline imaging findings or discordant laboratory profiles.

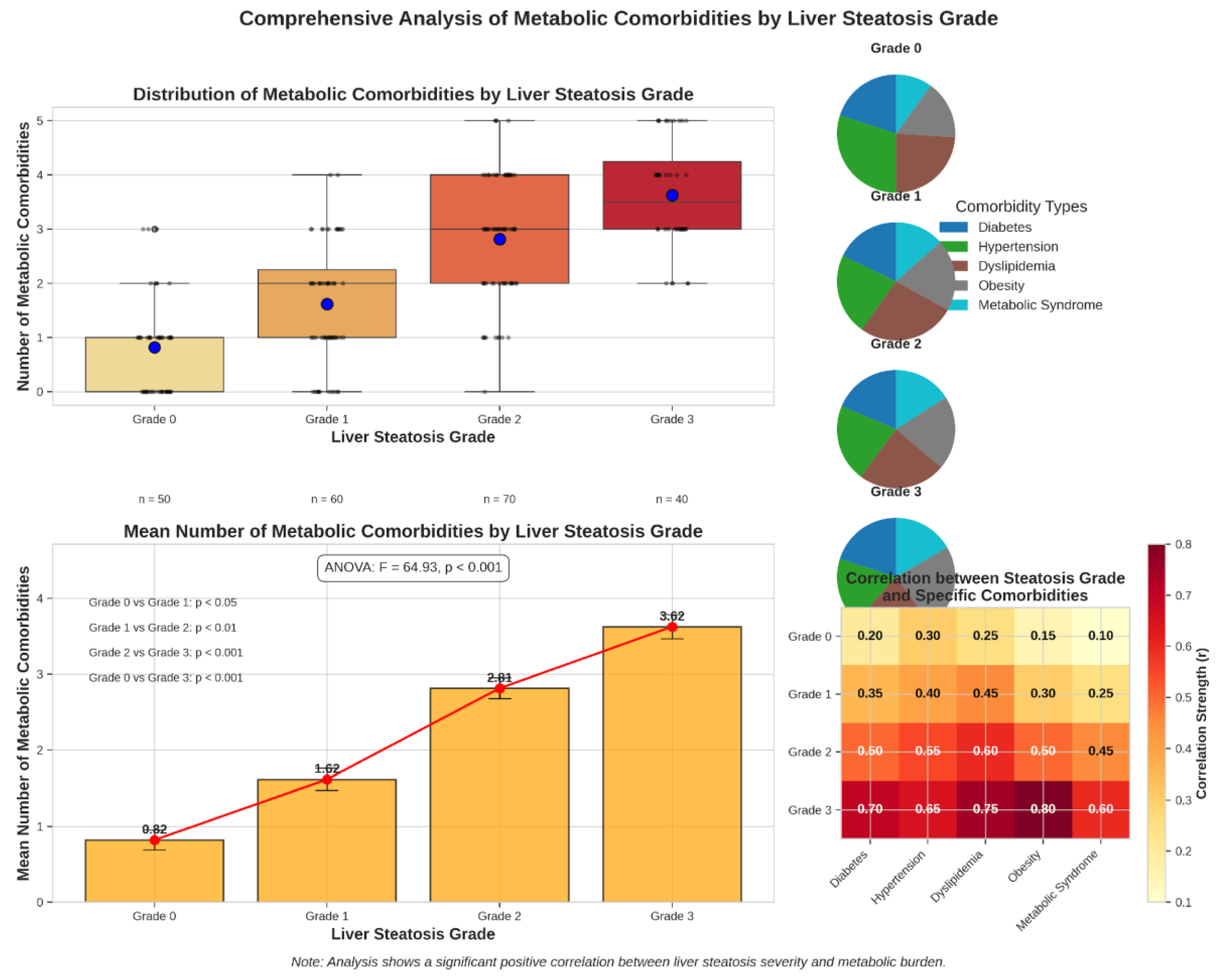

The dose–response relationship between steatosis grade and the accumulation of metabolic comorbidities is congruent with mechanistic pathways linking ectopic hepatic fat to systemic insulin resistance, atherogenic dyslipidemia, and low-grade inflammation. These findings reinforce international consensus recommendations supporting the MAFLD nomenclature and positive diagnostic criteria, which center the disease within a metabolic framework and facilitate risk-aligned care pathways [

2,

34]. In practical terms, the data support structured cardiometabolic screening—glycemic status, atherogenic lipid profile, blood pressure, and anthropometrics—in all individuals identified with hepatic steatosis, coupled with multidisciplinary management strategies that integrate hepatology, endocrinology, cardiology, and nutrition services [

35]. The observed pattern of liver biochemistry (elevated ALT/AST with AST/ALT < 1 across steatosis grades) aligns with typical MAFLD profiles and underscores the importance of concurrent non-invasive fibrosis risk stratification, given the prognostic weight of advanced fibrosis in MAFLD.

Several considerations may explain the absence of significant differences in hypertension, GERD, and chronic pancreatitis between groups. First, high background prevalence of hypertension in tertiary populations may attenuate detectable between-group contrasts, particularly when antihypertensive treatment normalizes measured blood pressure at the time of assessment. Second, shared risk determinants such as obesity and smoking could confound associations with GERD and pancreatitis; residual confounding may remain even after adjustment. Third, heterogeneity in diagnostic ascertainment (e.g., symptom-based GERD diagnosis, varying thresholds for imaging-confirmed pancreatitis) could introduce non-differential misclassification that biases estimates toward the null [

36,

37]. Divergences from studies reporting positive associations with gastrointestinal conditions [

38,

39] may reflect differences in population selection, comorbidity definitions, or analytic adjustment sets. Standardization of phenotyping and prospective designs are warranted to clarify these relationships.

Strengths of this study include a sizable sample, systematic extraction from electronic health records, comprehensive metabolic profiling, and the application of a dual diagnostic approach that integrates ultrasonography with histology where available. These features enhance internal validity and afford a nuanced description of comorbidity clustering in MAFLD. Nonetheless, limitations should be acknowledged. The single-center, tertiary care setting may constrain external generalizability, particularly to primary care or community-based populations. The cross-sectional nature of the dataset precludes causal inference and limits conclusions regarding temporal sequence between metabolic abnormalities and steatosis progression. Selection bias cannot be excluded, as referral patterns and clinical thresholds for imaging or biopsy may enrich the cohort for more severe phenotypes [

36,

37]. Additionally, ultrasonography’s reduced sensitivity for mild steatosis could lead to under-detection in controls, potentially diluting between-group differences; the availability of histology only in selected individuals may also introduce verification bias [

12,

40].

Clinical and public health implications emerge from these findings. The magnitude of association with type 2 diabetes and dyslipidemia supports routine metabolic screening in all patients with steatosis, with prompt initiation of guideline-directed lifestyle and pharmacologic interventions tailored to cardiometabolic risk reduction. Embedding non-invasive fibrosis assessment into clinical workflows can triage individuals for specialist evaluation and surveillance, addressing the subset at risk of progression. At a systems level, aligning hepatology and cardiometabolic care pathways may improve outcomes and resource efficiency through shared decision-making and coordinated follow-up [

35]. From a regional perspective, investigation into the interplay of genetic predisposition, diet, alcohol patterns below exclusion thresholds, and environmental exposures may help explain observed differences in comorbidity prevalence and guide targeted prevention efforts [

22,

33].

Future research should prioritize longitudinal cohorts with serial imaging and histological or elastography-based staging to map trajectories of metabolic risk and hepatic outcomes, and to quantify the impact of risk-modifying therapies on both hepatic and extrahepatic endpoints. Standardized definitions of gastrointestinal comorbidities and harmonized data capture protocols will be essential to resolve inconsistencies in the literature [

38,

39]. Finally, pragmatic trials and implementation studies that integrate hepatology with cardiometabolic care in real-world settings could elucidate best practices for risk stratification, monitoring, and multidisciplinary intervention [

40].

Conclusion

Our comprehensive study of 850 patients, utilizing both imaging diagnostics and histological This comprehensive evaluation of 850 patients, integrating routine imaging with targeted histological confirmation via liver biopsy, provides convergent evidence that metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) is closely linked with a heightened burden of metabolic comorbidities, most notably type 2 diabetes mellitus and dyslipidemia. Concordant radiological and histological gradations of steatosis severity were associated with progressively greater metabolic derangement, reinforcing the concept of MAFLD as a systemic metabolic disorder rather than an isolated hepatic condition and underscoring the bidirectional interplay between hepatic fat accumulation, insulin resistance, and atherogenic dyslipidemia.

These observations carry direct implications for clinical practice. First, they substantiate the clinical utility of the MAFLD framework, which emphasizes positive diagnostic criteria anchored in metabolic dysfunction and facilitates case ascertainment across diverse care settings. Second, they support systematic, longitudinal cardiometabolic risk assessment in all individuals with hepatic steatosis, including standardized screening for glycemic status, lipid abnormalities, and blood pressure control, with thresholds for intervention aligned to absolute risk. Third, they encourage a multidisciplinary management model that integrates hepatology, endocrinology, nutrition, and behavioral medicine to address lifestyle modification, weight management, and pharmacotherapy where indicated. Fourth, they highlight the complementary value of combining imaging-based detection with histological or elastography-informed staging in selected cases to refine risk stratification, guide intensity of follow-up, and inform therapeutic decision-making.

Strengths of the present work include the large sample size, breadth of phenotyping across metabolic domains, and an adjudication strategy that leverages both ultrasonography and biopsy to enhance diagnostic specificity. The coherent associations across clinical, biochemical, and imaging dimensions strengthen internal validity and reduce the likelihood of spurious findings. Nonetheless, several limitations merit consideration. The single-center, tertiary care context may preferentially capture more complex or severe phenotypes, potentially limiting generalizability to community populations. The cross-sectional design precludes causal inference and constrains the ability to temporally sequence steatosis progression relative to comorbidity development. Additionally, selective use of biopsy may introduce verification bias, and ultrasonography’s limited sensitivity for mild steatosis could attenuate group differences.

Looking forward, prospective, longitudinal investigations incorporating serial non-invasive fibrosis assessment and, when appropriate, histological evaluation are needed to delineate trajectories of hepatic and cardiometabolic risk, identify inflection points for intervention, and quantify the impact of lifestyle and pharmacologic therapies on both hepatic endpoints and extrahepatic outcomes. Validation of these findings across diverse populations and healthcare systems will clarify external validity and inform context-specific implementation. Further, disentangling the contributions of genetic susceptibility, dietary patterns, physical activity, and environmental exposures to regional variation in MAFLD burden and comorbidity clustering remains a priority for precision prevention and care.

Incorporating these insights into practice—through routine metabolic surveillance, risk-stratified use of imaging and histology, and coordinated multidisciplinary care—offers a pragmatic pathway to earlier identification, more accurate staging, and tailored management of MAFLD. Such an approach, coupled with targeted prospective research, is poised to improve patient-centered outcomes and to advance understanding of the complex metabolic networks that underlie this increasingly prevalent liver disease.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Abbreviations

| AI |

Artificial intelligence |

| ALT |

Alanine aminotransferase |

| AST |

Aspartate aminotransferase |

| AUC |

Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve |

| BMI |

Body mass index |

| CI |

Confidence interval |

| CKD |

Chronic kidney disease |

| CT |

Computed tomography |

| CVD |

Cardiovascular disease |

| EHR |

Electronic health record |

| GERD |

Gastroesophageal reflux disease |

| GGT |

Gamma-glutamyl transferase |

| HbA1c |

Glycated hemoglobin |

| HBV |

Hepatitis B virus |

| HCV |

Hepatitis C virus |

| HDL |

High-density lipoprotein |

| ICD-10 |

International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision |

| IQR |

Interquartile range |

| LASSO |

Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator |

| LDL |

Low-density lipoprotein |

| MAFLD |

Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease |

| OR |

Odds ratio |

| SD |

Standard deviation |

| SPSS |

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| ULN |

Upper limit of normal |

References

- Younossi, Z. M. , Koenig, A. B., Abdelatif, D., Fazel, Y., Henry, L., & Wymer, M. (2016). Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease—Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology, 64(1), 73–84. [CrossRef]

- Eslam, M. , Newsome, P. N., Sarin, S. K., Anstee, Q. M., Targher, G., Romero-Gomez, M.,... George, J. (2020). A new definition for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: An international expert consensus statement. Journal of Hepatology, 73(1), 202–209. [CrossRef]

- Eslam, M., Sanyal, A. J., & George, J.; International Consensus Panel. (2020). MAFLD: A consensus-driven proposed nomenclature for metabolic associated fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology, 158(7), 1999–2014.e1. [CrossRef]

- Tilg, H. , & Effenberger, M. (2020). From NAFLD to MAFLD: When pathophysiology succeeds. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 17(7), 387–388. [CrossRef]

- Targher, G. , Tilg, H., & Byrne, C. D. (2021). Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A multisystem disease requiring a multidisciplinary and holistic approach. The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 6(7), 578–588. [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, A. , Petracca, G., Beatrice, G., Csermely, A., Lonardo, A., & Targher, G. (2022). Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and increased risk of incident extrahepatic cancers: A meta-analysis of observational cohort studies. Gut, 71(4), 778–788. [CrossRef]

- Byrne, C. D., & Targher, G. (2020). NAFLD as a driver of chronic kidney disease. Journal of Hepatology, 72(4), 785–801. [CrossRef]

- Ciardullo, S., & Perseghin, G. (2021). Prevalence of NAFLD, MAFLD and associated advanced fibrosis in the contemporary United States population. Liver International, 41(6), 1290–1293. [CrossRef]

- Alexander, M. , Loomis, A. K., van der Lei, J., Duarte-Salles, T., Prieto-Alhambra, D., Ansell, D.,... Sattar, N. (2019). Risks and clinical predictors of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma diagnoses in adults with diagnosed NAFLD: Real-world study of 18 million patients in four European cohorts. BMC Medicine, 17(1), 95. [CrossRef]

- Eslam, M., Sarin, S. K., Wong, V. W., Fan, J.-G., Kawaguchi, T., Ahn, S. H., ... George, J. (2020). The Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of metabolic associated fatty liver disease. Hepatology International, 14(6), 889–919. [CrossRef]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. (2021). EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on non-invasive tests for evaluation of liver disease severity and prognosis – 2021 update. Journal of Hepatology, 75(3), 659–689. [CrossRef]

- Castera, L. , Friedrich-Rust, M., & Loomba, R. (2019). Noninvasive assessment of liver disease in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology, 156(5), 1264–1281.e4. [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z. M. , Golabi, P., de Avila, L., Paik, J. M., Srishord, M., Fukui, N.,... Nader, F. (2019). The global epidemiology of NAFLD and NASH in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Hepatology, 71(4), 793–801. [CrossRef]

- Huang, D. Q. , El-Serag, H. B., & Loomba, R. (2021). Global epidemiology of NAFLD-related HCC: Trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 18(4), 223–238. [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, J. V. , Palayew, A., Carrieri, P., Ekstedt, M., Marchesini, G., Novak, K.,... Colombo, M. (2021). European ‘NAFLD Preparedness Index’ – Is Europe ready to meet the challenge of fatty liver disease? JHEP Reports, 3(2), 100234. [CrossRef]

- Tsochatzis, E. A. , & Newsome, P. N. (2018). Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and the interface between primary and secondary care. The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 3(7), 509–517. [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z. M. , Rinella, M. E., Sanyal, A. J., Harrison, S. A., Brunt, E. M., Goodman, Z.,... Loomba, R. (2021). From NAFLD to MAFLD: Implications of a premature change in terminology. Hepatology, 73(3), 1194–1198. [CrossRef]

- Maev, I. V. , Samsonov, A. A., Palgova, L. K., Pavlov, C. S., Shirokova, E. N., Vovk, E. I., & Starostin, K. M. (2019). Real-world comorbidity burden, quality of life, and treatment satisfaction in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in Russia. European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 31(11), 1323–1332. [CrossRef]

- Drapkina, O. , Ivashkin, V., Ivashkin, K., Pavlov, C., Shirokova, E., Palgova, L., & Starostin, K. (2015). Prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in the Russian Federation: The results of an open multicenter prospective study, DIREG 2 [Article in Russian]. Russian Journal of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, Coloproctology, 25(2), 31–41. [CrossRef]

- Eslam, M. , Ahmed, A., Després, J.-P., Jha, V., Halford, J. C. G., Wei Chieh, J. T.,... George, J. (2021). Incorporating fatty liver disease in multidisciplinary care and novel clinical trial designs for patients with metabolic diseases. The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 6(9), 743–753. [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z. , Anstee, Q. M., Marietti, M., Hardy, T., Henry, L., Eslam, M.,... Bugianesi, E. (2018). Global burden of NAFLD and NASH: Trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 15(1), 11–20. [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E. , Altman, D. G., Egger, M., Pocock, S. J., Gøtzsche, P. C., & Vandenbroucke, J. P.; STROBE Initiative. (2008). The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 61(4), 344–349. [CrossRef]

- Ivashkin, V. T. , Mayevskaya, M. V., Pavlov, C. S., Tikhonov, I. N., Shirokova, E. N., Buyeverov, A. O.,... Palgova, L. K. (2016). Diagnostics and treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Clinical guidelines of the Russian Scientific Liver Society and the Russian Gastroenterological Association. Russian Journal of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, Coloproctology, 26(2), 24–42. [CrossRef]

- Bedogni, G. , Bellentani, S., Miglioli, L., Masutti, F., Passalacqua, M., Castiglione, A., & Tiribelli, C. (2006). The Fatty Liver Index: A simple and accurate predictor of hepatic steatosis in the general population. BMC Gastroenterology, 6(1), 33. [CrossRef]

- Chalasani, N. , Younossi, Z., Lavine, J. E., Charlton, M., Cusi, K., Rinella, M.,... Sanyal, A. J. (2018). The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology, 67(1), 328–357. [CrossRef]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver, European Association for the Study of Diabetes, & European Association for the Study of Obesity. (2016). EASL–EASD–EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Journal of Hepatology, 64(6), 1388–1402. [CrossRef]

- Hernaez, R. , Lazo, M., Bonekamp, S., Kamel, I., Brancati, F. L., Guallar, E., & Clark, J. M. (2011). Diagnostic accuracy and reliability of ultrasonography for the detection of fatty liver: A meta-analysis. Hepatology, 54(3), 1082–1090. [CrossRef]

- Alberti, K. G. , Eckel, R. H., Grundy, S. M., Zimmet, P. Z., Cleeman, J. I., Donato, K. A.,... Smith, S. C., Jr. (2009). Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: A joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention. Circulation, 120(16), 1640–1645. [CrossRef]

- Vandenbroucke, J. P., von Elm, E., Altman, D. G., Gøtzsche, P. C., Mulrow, C. D., Pocock, S. J., ... Egger, M.; STROBE Initiative. (2014). Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): Explanation and elaboration. International Journal of Surgery, 12(12), 1500–1524. [CrossRef]

- Topol, E. J. (2019). High-performance medicine: The convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nature Medicine, 25(1), 44–56. [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. (2013). World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA, 310(20), 2191–2194. [CrossRef]

- Fouad, Y. , Waked, I., Bollipo, S., Gomaa, A., Ajlouni, Y., & Attia, D. (2021). The NAFLD–MAFLD debate: A global perspective. Journal of Hepatology, 74(6), 1094–1096. [CrossRef]

- Targher, G., Tilg, H., & Byrne, C. D. (2020). Risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. The New England Journal of Medicine, 363(14), 1341–1350. [CrossRef]

- Tilg, H. , Moschen, A. R., & Roden, M. (2017). NAFLD and diabetes mellitus. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 14(1), 32–42. [CrossRef]

- Romero-Gómez, M. , Zelber-Sagi, S., Trenell, M., Cusi, K., Cortez-Pinto, H., & Marchesini, G. (2021). Treatment of MAFLD: Lifestyle and diet modification. Journal of Hepatology, 75(4), 1002–1013. [CrossRef]

- Byrne, C. D. , Targher, G., & Tilg, H. (2015). NAFLD: A multisystem disease. Journal of Hepatology, 62(1 Suppl), S47–S64. [CrossRef]

- Lonardo, A. , Nascimbeni, F., Ballestri, S., Fairweather, D. L., Win, S., Than, T. A., & Abdelmalek, M. F. (2021). Epidemiology and natural history of NAFLD. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(3), 1474. [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, Y., Arakawa, T., Terao, S., Sugano, K., & Chiba, T. (2019). Association between NAFLD and GERD. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 34(2), 324–330. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q. , Zhou, Y., Chen, Y., & Zhan, Q. (2020). NAFLD and chronic pancreatitis: A systematic review. Pancreatology, 20(5), 1046–1053. [CrossRef]

- Cusi, K. , Isaacs, S., Barb, D., Basu, R., Caprio, S., Garvey, W. T.,... Sanyal, A. J. (2021). A new era in the management of MAFLD. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 18(3), 196–208. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).