Submitted:

22 September 2024

Posted:

23 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

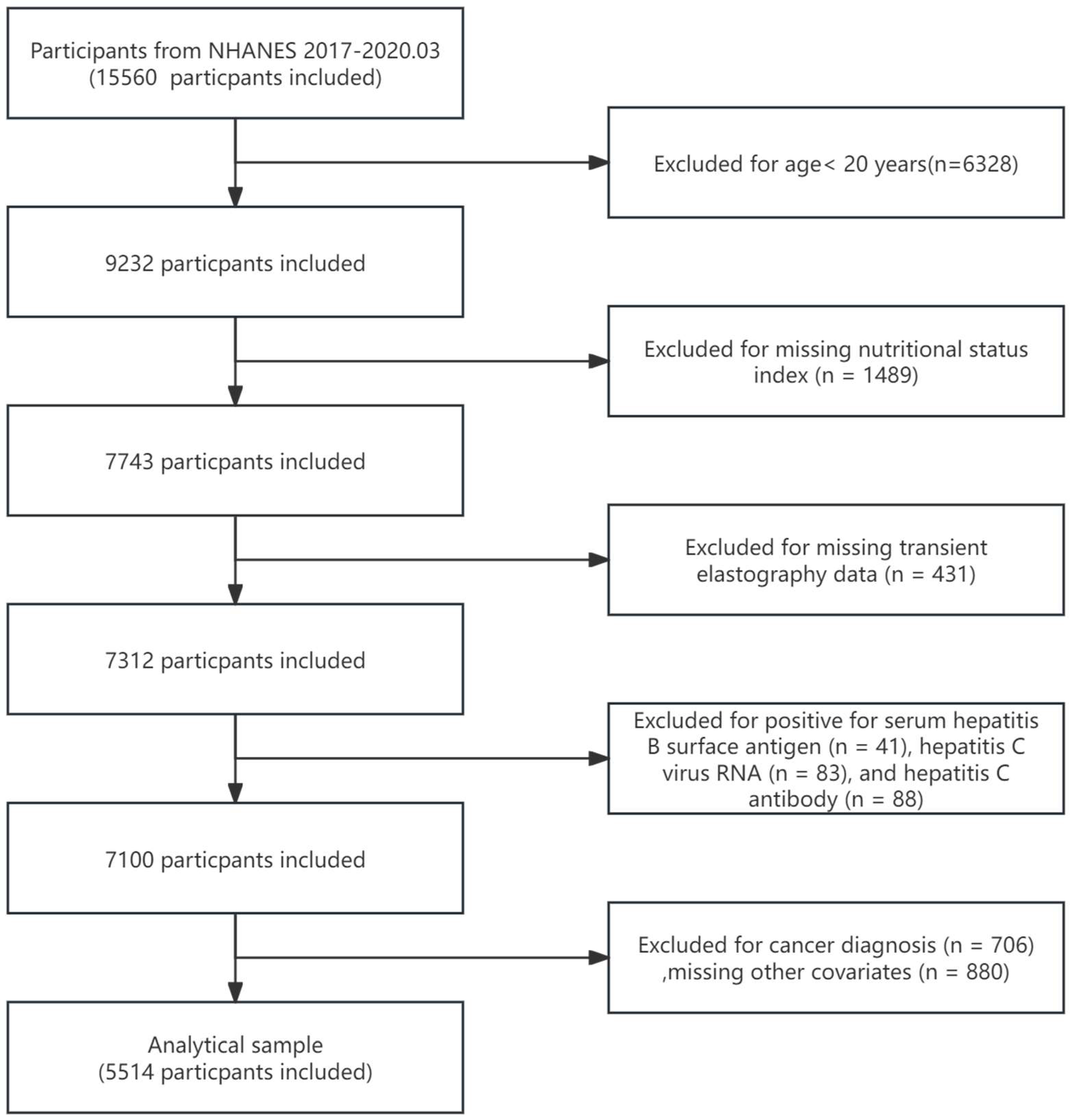

2. Materials and Methods

Assessment of NAFLD and AHF

Assessment of Nutritional Status

Covariates

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

| Characteristics | Total (n = 5514) | NAFLD | AHF | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No(n = 3426) | Yes(n = 2088) | p-value | No(n = 5155) | Yes(n = 359) | p-value | ||

| Age (years) | 48.67± 16.80 | 47.23 ± 17.50 | 51.04 ± 15.29 | <0.001 | 48.23 ± 16.82 | 54.99 ± 15.24 | <0.001 |

| Sex, n (%) | <0.001 | 0.005 | |||||

| Male | 2666(48.35%) | 1506 (43.96%) | 1160 (55.56%) | 2467 (47.86%) | 199 (55.43%) | ||

| Female | 2848(51.65%) | 1920 (56.04%) | 928 (44.44%) | 2688 (52.14%) | 160 (44.57%) | ||

| Race, n (%) | <0.001 | 0.062 | |||||

| Mexican American | 685(12.42%) | 318 (9.28%) | 367 (17.58%) | 634 (12.30%) | 51 (14.21%) | ||

| Other Hispanic | 575(10.43%) | 361 (10.54%) | 214 (10.25%) | 536 (10.40%) | 39 (10.86%) | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 1876(34.02%) | 1136 (33.16%) | 740 (35.44%) | 1738 (33.71%) | 138 (38.44%) | ||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1400(25.39%) | 957 (27.93%) | 443 (21.22%) | 1315 (25.51%) | 85 (23.68%) | ||

| Other Race - Including Multi-Racial | 978(17.74%) | 654 (19.09%) | 324 (15.52%) | 932 (18.08%) | 46 (12.81%) | ||

| Education level, n (%) | 0.007 | 0.092 | |||||

| Below high school | 957(17.36%) | 565 (16.49%) | 392 (18.77%) | 889 (17.25%) | 68 (18.94%) | ||

| High school | 1311(23.78%) | 789 (23.03%) | 522 (25.00%) | 1212 (23.51%) | 99 (27.58%) | ||

| Above high school | 3246(59.45%) | 2072 (60.48%) | 1174 (56.23%) | 3054 (59.24%) | 192 (53.48%) | ||

| Marital status , n (%) | <0.001 | 0.06 | |||||

| Married or living with partner | 3278(48.35%) | 1926 (56.22%) | 1352 (64.75%) | 3059 (59.34%) | 219 (61.00%) | ||

| Divorced, separated, or widowed | 1128(20.46%) | 706 (20.61%) | 422 (20.21%) | 1044 (20.25%) | 84 (23.40%) | ||

| Never married | 1108(20.09%) | 794 (23.18%) | 314 (15.04%) | 1052 (20.41%) | 56 (15.60%) | ||

| PIR, n (%) | 0.3 | 0.002 | |||||

| <1.3 | 1547(28.06%) | 973 (28.40%) | 574 (27.49%) | 1447 (28.07%) | 100 (27.86%) | ||

| 1.3-3.5 | 2149(38.97%) | 1308 (38.18%) | 841 (40.28%) | 1981 (38.43%) | 168 (46.80%) | ||

| ≥3.5 | 1818(32.97%) | 1145 (33.42%) | 673 (32.23%) | 1727 (33.50%) | 91 (25.35%) | ||

| BMI | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| < 25.0 kg/m² | 1404(25.46%) | 1278 (37.30%) | 126 (6.03%) | 1386 (26.89%) | 18 (5.01%) | ||

| 25.0–29.9 kg/m² | 1720(31.19%) | 1185 (34.59%) | 535 (25.62%) | 1670 (32.40%) | 50 (13.93%) | ||

| >29.9 kg/m² | 2390(43.34%) | 963 (28.11%) | 1427 (68.34%) | 2099 (40.72%) | 291 (81.06%) | ||

| Stroke,n (%) | 0.421 | 0.066 | |||||

| Yes | 221(4.01%) | 143 (4.17%) | 78 (3.74%) | 200 (3.88%) | 21 (5.85%) | ||

| NO | 5293(95.99%) | 3283 (95.83%) | 2010 (96.26%) | 4955 (96.12%) | 338 (94.15%) | ||

| Pulmonary disease, n (%) | 0.003 | 0.003 | |||||

| Yes | 1099(19.93%) | 640 (18.68%) | 459 (21.98%) | 1006 (19.52%) | 93 (25.91%) | ||

| NO | 4415(80.07%) | 2786 (81.32%) | 1629 (78.02%) | 4149 (80.48%) | 266 (74.09%) | ||

| Heart disease, n (%) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| Yes | 380(6.89%) | 194 (5.66%) | 186 (8.91%) | 322 (6.25%) | 58 (16.16%) | ||

| NO | 5134(93.11%) | 3232 (94.34%) | 1902 (91.09%) | 4833 (93.75%) | 301 (83.84%) | ||

| Hypertension, n (%) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| Yes | 2980(54.04%) | 1563 (45.62%) | 1417 (67.86%) | 2699 (52.36%) | 281 (78.27%) | ||

| NO | 2534(45.96%) | 1863 (54.38%) | 671 (32.14%) | 2456 (47.64%) | 78 (21.73%) | ||

| Diabetes, n (%) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| Yes | 986(17.88%) | 364 (10.62%) | 622 (29.79%) | 812 (15.75%) | 174 (48.47%) | ||

| NO | 4528(82.12%) | 3062 (89.38%) | 1466 (70.21%) | 4343 (84.25%) | 185 (51.53%) | ||

| Intensity of activity, n (%) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| Moderate to low | 2530(45.88%) | 1506 (43.96%) | 1024 (49.04%) | 2330 (45.20%) | 200 (55.71%) | ||

| High | 2984(54.12%) | 1920 (56.04%) | 1064 (50.96%) | 2825 (54.80%) | 159 (44.29%) | ||

| Smoking status, n (%) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| Former | 1252(22.71%) | 675 (19.70%) | 577 (27.63%) | 1132 (21.96%) | 120 (33.43%) | ||

| Current | 958(17.37%) | 622 (18.16%) | 336 (16.09%) | 910 (17.65%) | 48 (13.37%) | ||

| Never | 3304(59.92%) | 2129 (62.14%) | 1175 (56.27%) | 3113 (60.39%) | 191 (53.20%) | ||

| Drinking status, n (%) | 0.257 | 0.005 | |||||

| Moderate | 1899(34.44%) | 1179 (34.41%) | 720 (34.48%) | 1767 (34.28%) | 132 (36.77%) | ||

| Heavy | 1958(35.51%) | 1241 (36.22%) | 717 (34.34%) | 1858 (36.04%) | 100 (27.86%) | ||

| Never | 1657(30.05%) | 1006 (29.36%) | 651 (31.18%) | 1530 (29.68%) | 127 (35.38%) | ||

| Chronic kidney disease | <0.001 | 0.296 | |||||

| Yes | 1037(18.81%) | 596 (17.40%) | 441 (21.12%) | 962 (18.66%) | 75 (20.89%) | ||

| NO | 4477(81.19%) | 2830 (82.60%) | 1647 (78.88%) | 4193 (81.34%) | 284 (79.11%) | ||

| ALT | 22.17± 16.27 | 18.81 ± 12.10 | 27.67 ± 20.25 | <0.001 | 21.46 ± 14.72 | 32.34 ± 29.11 | <0.001 |

| ALP | 77.00± 25.73 | 74.41 ± 26.00 | 81.25 ± 24.71 | <0.001 | 76.16 ± 24.83 | 89.06 ± 34.15 | <0.001 |

| AST | 21.55± 12.50 | 20.43 ± 10.17 | 23.39 ± 15.43 | <0.001 | 20.96 ± 9.97 | 30.06 ± 29.97 | <0.001 |

| GGT | 31.63± 53.53 | 26.54 ± 54.61 | 39.98 ± 50.63 | <0.001 | 29.20 ± 38.19 | 66.53 ± 147.71 | <0.001 |

| GNRI | 117.36± 13.48 | 112.87 ± 11.30 | 124.72 ± 13.54 | <0.001 | 116.31 ± 12.29 | 132.38 ± 19.58 | <0.001 |

| PNI | 51.81± 5.15 | 51.63 ± 5.11 | 52.10 ± 5.22 | <0.001 | 51.87 ± 5.10 | 50.90 ± 5.76 | <0.001 |

| CONUT | 1.38± 0.76 | 1.40 ± 0.77 | 1.34 ± 0.73 | 0.002 | 1.37 ± 0.73 | 1.58 ± 1.02 | <0.001 |

| TCBI | 2335.01± 2414.36 | 1729.94 ± 1541.31 | 3327.82 ± 3148.38 | <0.001 | 2252.99 ± 2297.38 | 3512.78 ± 3506.11 | <0.001 |

| AGR | 1.35± 0.24 | 1.37 ± 0.24 | 1.32 ± 0.24 | <0.001 | 1.36 ± 0.24 | 1.27 ± 0.26 | <0.001 |

3.2. Association of Nutrition-Related Indices with NAFLD and AHF

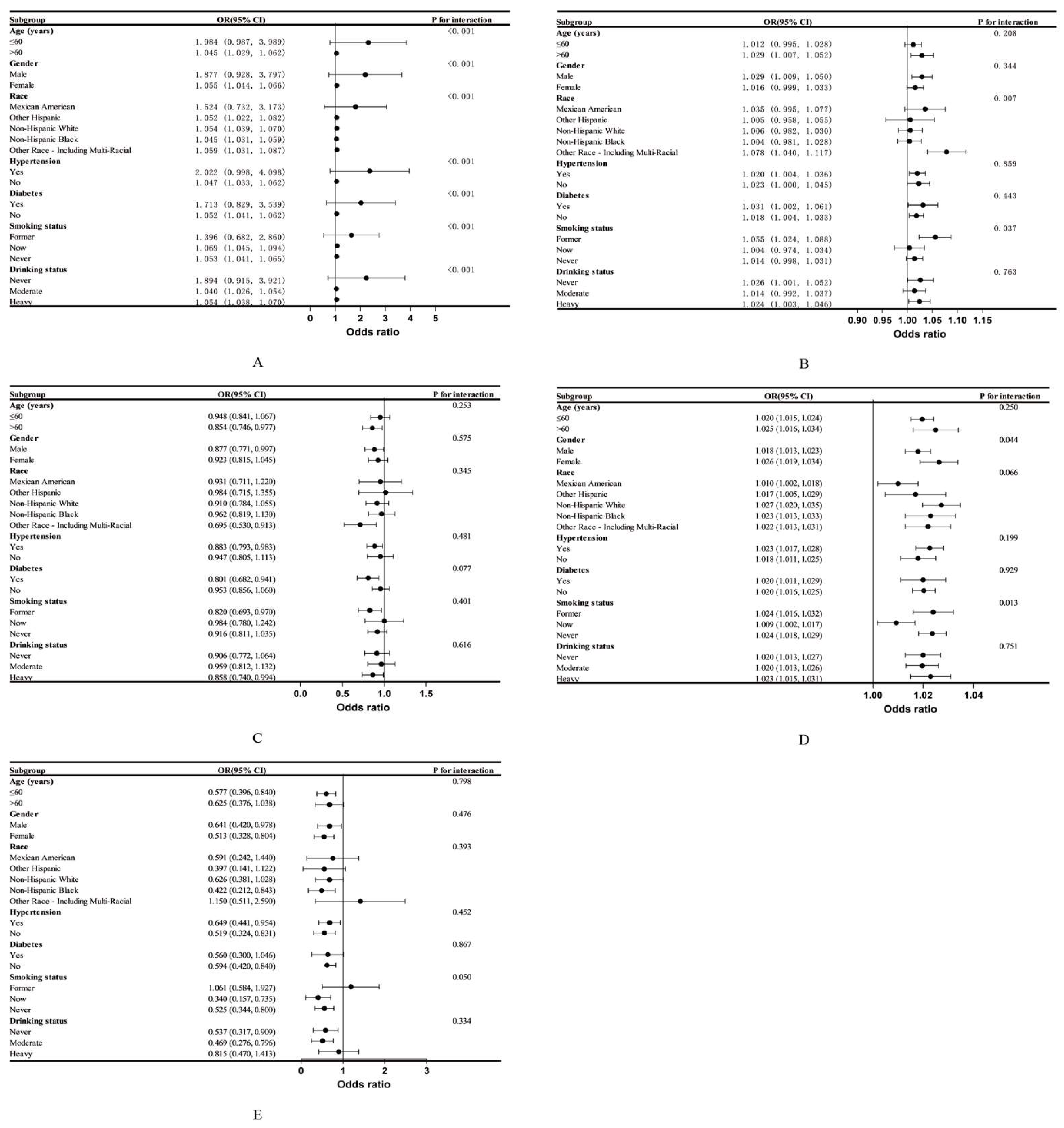

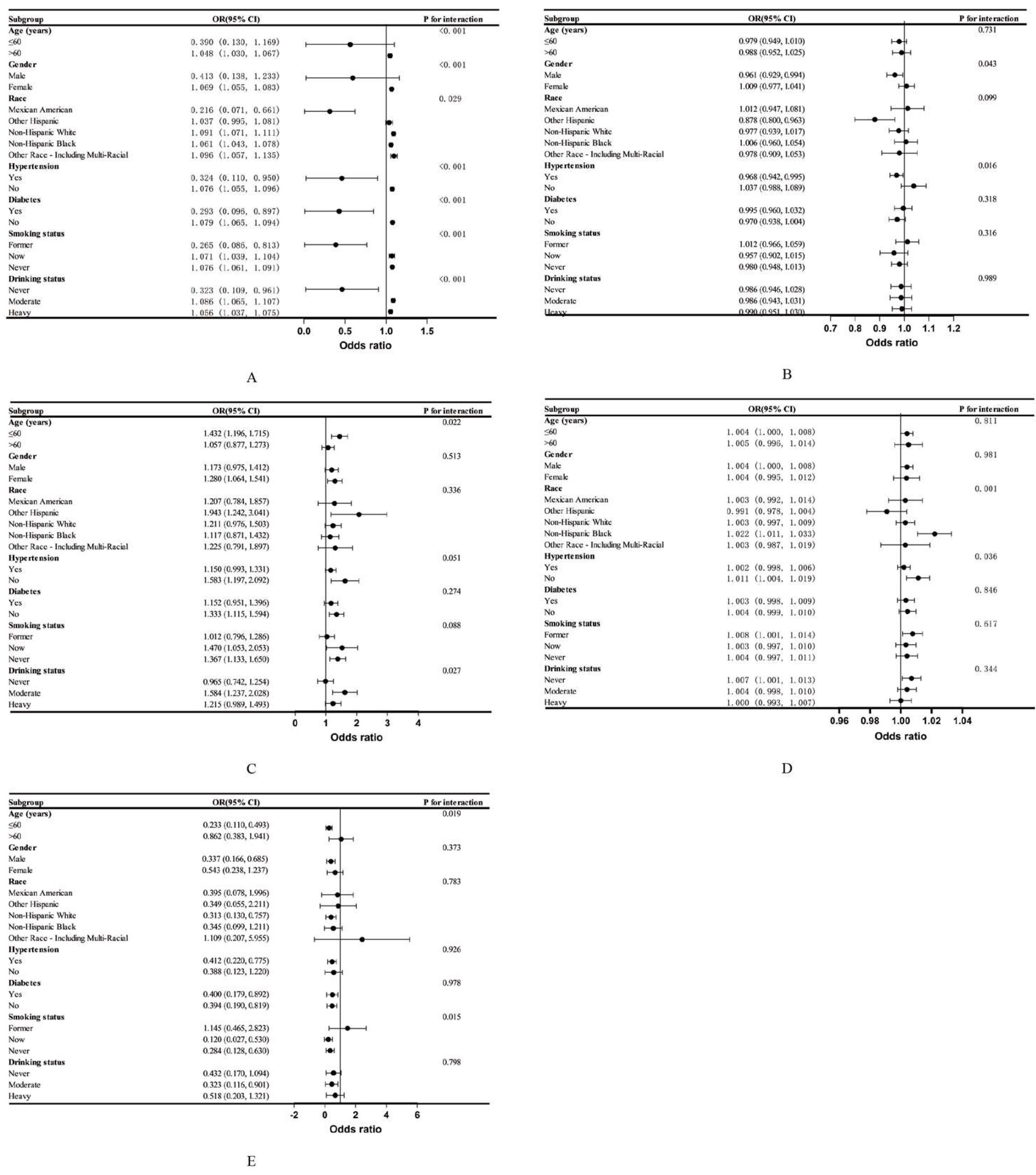

3.3. Subgroup Analysis

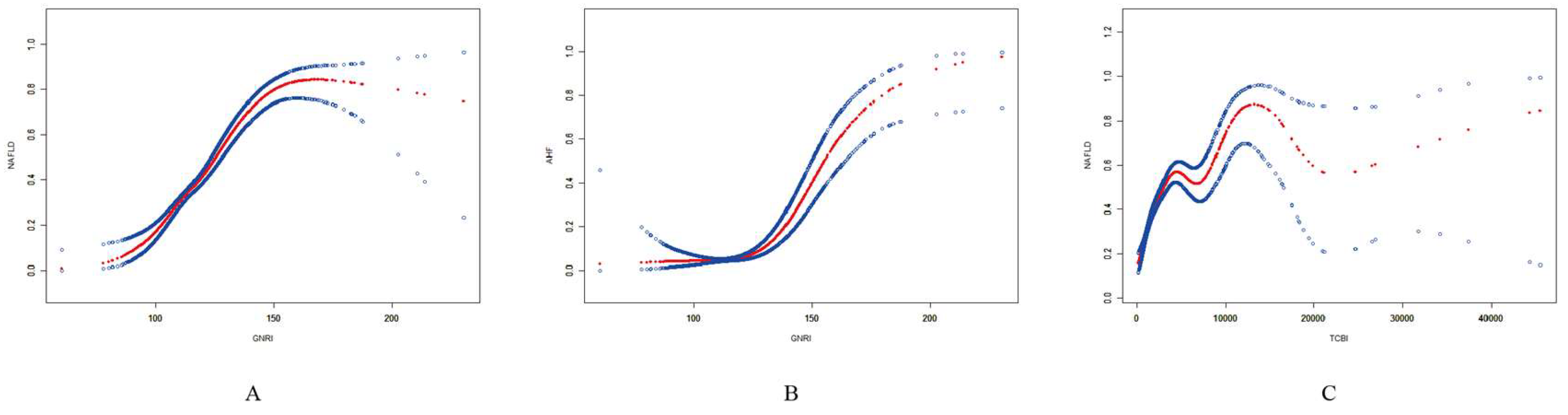

3.4. Smooth Curve Fitting and Threshold Effect Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Blüher, M. Obesity: global epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nature reviews Endocrinology. 2019;15(5):288-98. [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z.M.; Stepanova, M.; Younossi, Y.; Golabi, P.; Mishra, A.; Rafiq, N. , et al. Epidemiology of chronic liver diseases in the USA in the past three decades. Gut. 2020;69(3):564-8. [CrossRef]

- Shah, P.A.; Patil, R.; Harrison, S.A. NAFLD-related hepatocellular carcinoma: The growing challenge. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md). 2023;77(1):323-38. [CrossRef]

- Buzzetti, E.; Pinzani, M.; Tsochatzis, E.A. The multiple-hit pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Metabolism: clinical and experimental. 2016;65(8):1038-48. 10.1016/j.metabol.2015.12.012.

- Tanwar, S.; Rhodes, F.; Srivastava, A.; Trembling, P.M.; Rosenberg, W.M. Inflammation and fibrosis in chronic liver diseases including non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and hepatitis C. World journal of gastroenterology. 2020;26(2):109-33. [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.G.; Cao, H.X. Role of diet and nutritional management in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Journal of gastroenterology and hepatology. 2013;28 Suppl 4:81-7. [CrossRef]

- Rives, C.; Fougerat, A.; Ellero-Simatos, S.; Loiseau, N.; Guillou, H.; Gamet-Payrastre, L. , et al. Oxidative Stress in NAFLD: Role of Nutrients and Food Contaminants. Biomolecules. 2020;10(12). [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.L.; Norhaizan, M.E.; Liew, W.P. Nutrients and Oxidative Stress: Friend or Foe? Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity. 2018;2018:9719584.

- Ucar, F.; Sezer, S.; Erdogan, S.; Akyol, S.; Armutcu, F.; Akyol, O. The relationship between oxidative stress and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Its effects on the development of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Redox report: communications in free radical research. 2013;18(4):127-33. [CrossRef]

- Alisi, A.; McCaughan, G.; Grønbæk, H. Role of gut microbiota and immune cells in metabolic-associated fatty liver disease: clinical impact. Hepatology international. 2024. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Fan, L.; Yang, T.; Xu, T.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y. , et al. Prognostic nutritional index (PNI) and risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and advanced liver fibrosis in US adults: Evidence from NHANES 2017-2020. Heliyon. 2024;10(4):e25660. [CrossRef]

- Bouillanne, O.; Morineau, G.; Dupont, C.; Coulombel, I.; Vincent, J.P.; Nicolis, I. , et al. Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index: a new index for evaluating at-risk elderly medical patients. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2005;82(4):777-83.

- Onodera, T.; Goseki, N.; Kosaki, G. [Prognostic nutritional index in gastrointestinal surgery of malnourished cancer patients]. Nihon Geka Gakkai zasshi. 1984;85(9):1001-5.

- Buzby, G.P.; Mullen, J.L.; Matthews, D.C.; Hobbs, C.L.; Rosato, E.F. Prognostic nutritional index in gastrointestinal surgery. American journal of surgery. 1980;139(1):160-7. [CrossRef]

- Doi, S.; Iwata, H.; Wada, H.; Funamizu, T.; Shitara, J.; Endo, H. , et al. A novel and simply calculated nutritional index serves as a useful prognostic indicator in patients with coronary artery disease. International journal of cardiology. 2018;262:92-8. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Qin, S.; Sun, X.; Liu, D.; Zhang, B.; Xiao, G. , et al. Prognostic Significance of Albumin-Globulin Score in Patients with Operable Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Annals of surgical oncology. 2018;25(12):3647-59. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Zhou, D.; Li, T.; Wang, C.; Fei, S. The relationship between Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index (GNRI) and in-hospital mortality in critically ill patients with Acute Kidney Injury (AKI). BMC anesthesiology. 2024;24(1):313. [CrossRef]

- Belinskaia, D.A.; Jenkins, R.O.; Goncharov, N.V. Serum Albumin in Health and Disease: From Comparative Biochemistry to Translational Medicine. International journal of molecular sciences. 2023;24(18). [CrossRef]

- Oettl, K.; Birner-Gruenberger, R.; Spindelboeck, W.; Stueger, H.P.; Dorn, L.; Stadlbauer, V. , et al. Oxidative albumin damage in chronic liver failure: relation to albumin binding capacity, liver dysfunction and survival. Journal of hepatology. 2013;59(5):978-83. [CrossRef]

- Khanna, D.; Kar, P.; Sahu, P. Efficacy of long-term albumin therapy in the treatment of decompensated cirrhosis. Indian journal of gastroenterology: official journal of the Indian Society of Gastroenterology. 2024;43(2):494-504.

- Lela, L.; Russo, D.; De Biasio, F.; Gorgoglione, D.; Ostuni, A.; Ponticelli, M. , et al. Solanum aethiopicum L. from the Basilicata Region Prevents Lipid Absorption, Fat Accumulation, Oxidative Stress, and Inflammation in OA-Treated HepG2 and Caco-2 Cell Lines. Plants (Basel, Switzerland). 2023;12(15). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, C.; Huang, K.; Zhao, J.; Le, S. , et al. B-cell lymphoma 6 alleviates nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in mice through suppression of fatty acid transporter CD36. Cell death & disease. 2022;13(4):359. [CrossRef]

- Radu, F.; Potcovaru, C.G.; Salmen, T.; Filip, P.V.; Pop, C. , Fierbințeanu-Braticievici C. The Link between NAFLD and Metabolic Syndrome. Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland). 2023;13(4). [CrossRef]

- Pinato, D.J.; North, B.V.; Sharma, R. A novel, externally validated inflammation-based prognostic algorithm in hepatocellular carcinoma: the prognostic nutritional index (PNI). British journal of cancer. 2012;106(8):1439-45. [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.W.; Chan, S.L.; Wong, G.L.; Wong, V.W.; Chong, C.C.; Lai, P.B. , et al. Prognostic Nutritional Index (PNI) Predicts Tumor Recurrence of Very Early/Early Stage Hepatocellular Carcinoma After Surgical Resection. Annals of surgical oncology. 2015;22(13):4138-48. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Guan, Y.; Zheng, F. CD4(+) T cell activation and inflammation in NASH-related fibrosis. Frontiers in immunology. 2022;13:967410. [CrossRef]

- Mao, T.; Yang, R.; Luo, Y.; He, K. Crucial role of T cells in NAFLD-related disease: A review and prospect. Frontiers in endocrinology. 2022;13:1051076. [CrossRef]

- Bruzzì, S.; Sutti, S.; Giudici, G.; Burlone, M.E.; Ramavath, N.N.; Toscani, A. , et al. B2-Lymphocyte responses to oxidative stress-derived antigens contribute to the evolution of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Free radical biology & medicine. 2018;124:249-59. [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Cao, W.W.; Chen, S.H.; Zhang, B.F.; Zhang, Y.M. Association between total cholesterol and all-cause mortality in geriatric patients with hip fractures: A prospective cohort study with 339 patients. Advances in clinical and experimental medicine: official organ Wroclaw Medical University. 2024;33(5):463-71. [CrossRef]

- Rauchbach, E.; Zeigerman, H.; Abu-Halaka, D.; Tirosh, O. Cholesterol Induces Oxidative Stress, Mitochondrial Damage and Death in Hepatic Stellate Cells to Mitigate Liver Fibrosis in Mice Model of NASH. Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland). 2022;11(3). [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.; Bicho, M.; Serejo, F. ABCA1 Polymorphism R1587K in Chronic Hepatitis C Is Gender-Specific and Modulates Liver Disease Severity through Its Influence on Cholesterol Metabolism and Liver Function: A Preliminary Study. Genes. 2022;13(11). [CrossRef]

- Miano, N.; Todaro, G.; Di Marco, M.; Scilletta, S.; Bosco, G.; Di Giacomo Barbagallo, F. , et al. Malnutrition-Related Liver Steatosis, CONUT Score and Poor Clinical Outcomes in an Internal Medicine Department. Nutrients. 2024;16(12). [CrossRef]

- Ishiwata, S.; Yatsu, S.; Kasai, T.; Sato, A.; Matsumoto, H.; Shitara, J. , et al. Prognostic Effect of a Novel Simply Calculated Nutritional Index in Acute Decompensated Heart Failure. Nutrients. 2020;12(11). [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Wang, X.; Yu, C.; Zhou, W.; Wang, T.; Zhu, L. , et al. Association of a novel nutritional index with stroke in Chinese population with hypertension: Insight from the China H-type hypertension registry study. Frontiers in nutrition. 2023;10:997180. [CrossRef]

- Gastaldelli, A. Insulin resistance and reduced metabolic flexibility: cause or consequence of NAFLD? Clinical science (London, England: 1979). 2017;131(22):2701-4.

- Moreno-Vedia, J.; Llop, D.; Rodríguez-Calvo, R.; Plana, N.; Amigó, N.; Rosales, R. , et al. Lipidomics of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins derived from hyperlipidemic patients on inflammation. European journal of clinical investigation. 2024;54(3):e14132. [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Niu, X.; Yu, R.; Zhao, R.; Wang, Q.; Sun, N. , et al. Association of Serum AGR With All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality Among Individuals With Diabetes. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Duran-Güell, M.; Flores-Costa, R.; Casulleras, M.; López-Vicario, C.; Titos, E.; Díaz, A.; et al. Albumin protects the liver from tumor necrosis factor α-induced immunopathology. FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2021;35(2):e21365.

- Yang, M.; Zhang, Q.; Ge, Y.; Tang, M.; Hu, C.; Wang, Z. , et al. Prognostic Roles of Inflammation- and Nutrition-Based Indicators for Female Patients with Cancer. Journal of inflammation research. 2022;15:3573-86.

- Patrick-Melin, A.J.; Kalinski, M.I.; Kelly, K.R.; Haus, J.M.; Solomon, T.P.; Kirwan, J.P. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: biochemical and therapeutic considerations. Ukrains’kyi biokhimichnyi zhurnal (1999 ). 2009;81(5):16-25.

- Sakamoto, N.; Suda, G.; Morikawa, K.; Ogawa, K. Nutrition is often ignored in management of chronic liver diseases. Journal of gastroenterology and hepatology. 2019;34(7):1127-8. [CrossRef]

| Nutrition-related indicators | Calculation formula | Reference |

| GNRI | 1.489 × serum albumin (g/L) + 41.7 × (current weight/ideal weight) Men: Ideal body weight = Height (cm) − 100 − (Height (cm) − 150)/4 Women: Ideal body weight = Height (cm) − 100 − (Height (cm) − 150)/2.5 |

[12] |

| PNI | Albumin (g/L) + 5 × total lymphocyte count (109/L) | [13] |

| CONUT | Serum albumin score + total lymphocyte count score + total cholesterol score Albumin score: 0, 2, 4 and 6 points are assigned when the albumin level is ≥3.5, 3.0-3.49, 2.5-2.99 and <2.5 g/dL, respectively.Lymphocyte total score: 0, 1, 2 and 3 points are awarded for total lymphocyte counts of ≥1,600, 1,200-1,599, 800-1,199 and <800/mm3, respectively.Total cholesterol score: When the total cholesterol level is ≥180, 140-179, 100-139 and <100 mg/dL, the corresponding scores are 0, 1, 2 and 3 points, respectively. |

[14] |

| TCBI | Triglycerides (mg/dL) × Total cholesterol (mg/dL) × Weight (kg)/1,000 | [15] |

| AGR | Albumin (g/L)/Globulin (g/L) | [16] |

| Characteristics | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

| GNRI continuous | 1.086 (1.080, 1.093) *** | 1.099 (1.092, 1.106) *** | 1.054 (1.045, 1.063) *** |

| GNRI binary | |||

| < 98 | 1[Reference] | 1[Reference] | 1[Reference] |

| ≥ 98 | 12.814 (6.774, 24.242)*** | 12.370 (6.513, 23.492) *** | 2.487 (1.238, 4.996)* |

| PNI continuous | 1.018 (1.007, 1.029) *** | 1.022 (1.011, 1.034)* | 1.020 (1.007, 1.034)** |

| PNI quartiles | |||

| Quartile 1 | 1[Reference] | 1[Reference] | 1[Reference] |

| Quartile 2 | 1.090 (0.929, 1.280) | 1.116 (0.946, 1.317) | 1.156 (0.955, 1.400) |

| Quartile 3 | 1.048 (0.893, 1.229) | 1.104 (0.935, 1.305) | 1.179 (0.971, 1.431) |

| Quartile 4 | 1.271 (1.091, 1.481) ** | 1.343 (1.141, 1.581)*** | 1.351 (1.115, 1.638)** |

| P for trend | 0.004 | <0.001 | 0.003 |

| CONUT continuous | 0.891 (0.827, 0.960)** | 0.849 (0.785, 0.917) *** | 0.899 (0.821, 0.983) * |

| CONUT ternary | |||

| 0-1 | 1[Reference] | 1[Reference] | 1[Reference] |

| 2-4 | 0.789 (0.696, 0.894) *** | 0.733 (0.644, 0.835) *** | 0.873 (0.748, 1.019) |

| 5-12 | 0.651 (0.321, 1.321) | 0.540 (0.262, 1.113) | 0.476 (0.209, 1.083) |

| P for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.032 |

| TCBI/100 continuous | 1.049 (1.044, 1.053) *** | 1.046 (1.042, 1.051)*** | 1.021 (1.017, 1.025)* |

| TCBI/100 quartiles | |||

| Quartile 1 | 1[Reference] | 1[Reference] | 1[Reference] |

| Quartile 2 | 2.766 (2.266, 3.376) *** | 2.608 (2.131, 3.193)*** | 1.547 (1.236, 1.935) *** |

| Quartile 3 | 6.083 (5.017, 7.376) *** | 5.525 (4.542, 6.720) *** | 2.347 (1.882, 2.928) *** |

| Quartile 4 | 13.539 (11.135, 16.462) *** | 12.198 (9.990, 14.894)*** | 3.751 (2.982, 4.718) *** |

| P for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| AGR continuous | 0.434 (0.345, 0.546) *** | 0.255 (0.197, 0.330)*** | 0.588 (0.431, 0.801)*** |

| AGR quartiles | |||

| Quartile 1 | 1[Reference] | 1[Reference] | 1[Reference] |

| Quartile 2 | 0.784 (0.673, 0.912) ** | 0.685 (0.584, 0.803) *** | 0.887 (0.738, 1.066) |

| Quartile 3 | 0.698 (0.598, 0.815) *** | 0.540 (0.457, 0.637) *** | 0.759 (0.624, 0.923)** |

| Quartile 4 | 0.583 (0.500, 0.681) *** | 0.418 (0.353, 0.496) *** | 0.763 (0.622, 0.936)* |

| P for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.004 |

| Characteristics | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

| GNRI continuous | 1.071 (1.063, 1.079) *** | 1.087 (1.078, 1.096) *** | 1.074 (1.062, 1.086) ** |

| GNRI binary | |||

| < 98 | 1[Reference] | 1[Reference] | 1[Reference] |

| ≥ 98 | 2.051 (0.958, 4.388) | 1.973 (0.917, 4.245) | 0.544 (0.184, 1.604) |

| PNI continuous | 0.961 (0.940, 0.983)*** | 0.975 (0.953, 0.998) * | 0.984 (0.961, 1.008) |

| PNI quartiles | |||

| Quartile 1 | 1[Reference] | 1[Reference] | 1[Reference] |

| Quartile 2 | 0.632 (0.468, 0.854) ** | 0.676 (0.498, 0.917) * | 0.784 (0.563, 1.093) |

| Quartile 3 | 0.600 (0.443, 0.812) *** | 0.689 (0.505, 0.940) * | 0.812 (0.577, 1.141) |

| Quartile 4 | 0.658 (0.495, 0.874)** | 0.793 (0.588, 1.069) | 0.875 (0.628, 1.219) |

| P for trend | 0.005 | 0.154 | 0.493 |

| CONUT continuous | 1.351 (1.206, 1.513) *** | 1.265 (1.125, 1.422) *** | 1.219 (1.068, 1.391) ** |

| CONUT ternary | |||

| 0-1 | 1[Reference] | 1[Reference] | 1[Reference] |

| 2-4 | 1.398 (1.111, 1.759) ** | 1.244 (0.983, 1.573) | 1.274 (0.980, 1.658) |

| 5-12 | 3.105 (1.283, 7.516)* | 2.430 (0.990, 5.965) | 2.097 (0.778, 5.655) |

| P for trend | <0.001 | 0.021 | 0.033 |

| TCBI/100 continuous | 1.012 (1.009, 1.016) *** | 1.012 (1.009, 1.015) *** | 1.004 (1.000, 1.008) * |

| TCBI/100 quartiles | |||

| Quartile 1 | 1[Reference] | 1[Reference] | 1[Reference] |

| Quartile 2 | 1.650 (1.063, 2.562) * | 1.883 (1.216, 2.915) ** | 0.995 (0.616, 1.606) |

| Quartile 3 | 2.979 (1.984, 4.473) *** | 3.508 (2.345, 5.247) *** | 1.193 (0.756, 1.882) |

| Quartile 4 | 4.993 (3.369, 7.399) *** | 5.603 (3.805, 8.251)*** | 1.453 (0.923, 2.287) |

| P for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.022 |

| AGR continuous | 0.189 (0.118, 0.304) *** | 0.133 (0.080, 0.220) *** | 0.411 (0.235, 0.716) ** |

| AGR quartiles | |||

| Quartile 1 | 1[Reference] | 1[Reference] | 1[Reference] |

| Quartile 2 | 0.480 (0.360, 0.640) *** | 0.438 (0.326, 0.588)*** | 0.617 (0.447, 0.852) ** |

| Quartile 3 | 0.464 (0.345, 0.623) *** | 0.389 (0.285, 0.530) *** | 0.645 (0.457, 0.909)* |

| Quartile 4 | 0.405 (0.301, 0.547) *** | 0.325 (0.236, 0.448) *** | 0.657 (0.459, 0.940)* |

| P for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.019 |

| Characteristics | OR (95% CI) |

| GNRI and NAFLD | |

| Fitting by standard linear model | 1.054 (1.045, 1.063) |

| Fitting by two-piecewise linear model | |

| Inflection point | 141.16 |

| < 141.16 | 1.066 (1.054, 1.077) |

| > 141.16 | 1.016 (0.996, 1.036) |

| Log likelihood ratio | <0.001 |

| GNRI and AHF | |

| Fitting by standard linear model | 1.074 (1.062, 1.086) |

| Fitting by two-piecewise linear model | |

| Inflection point | 120.17 |

| < 120.17 | 0.992 (0.953, 1.034) |

| > 120.17 | 1.083 (1.070, 1.096) |

| Log likelihood ratio | <0.001 |

| TCBI/100 and NAFLD | |

| Fitting by standard linear model | 1.021 (1.017, 1.025) |

| Fitting by two-piecewise linear model | |

| Inflection point | 31.20 |

| < 31.20 | 1.052 (1.042, 1.061) |

| > 31.20 | 1.005 (1.001, 1.010) |

| Log likelihood ratio | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).