1. Introduction and Motivation

Casually observing a negative relation between two factors in all strands of life is a trivial matter: increase of sugar intake tends to decrease dental health; increase of exercise tends to decrease body weight; in high temperatures the consumption of hot drinks tends to decrease, etc. But in these examples and others like them, there is a direct causal and often physical treatment effect of the one factor over the other that tends to produce the negative relation. While, strictly speaking, the relation should be modeled as stochastic and not deterministic since other factors are expected to come into play, at the same time it remains mostly a strong and almost-deterministic relation with random two-sided shocks.

More interesting are cases where the negative relation/dependence arises between two non-negative random variables in systems, socio-economic or other, where there are “automatic stabilizers” in some equilibrium region, and the movement of one variable towards one direction often triggers the movement of the other towards the opposite one. The negative relation between selling price and quantity demanded in open markets is one economic example that comes easily to mind. Yet again, other more complex frameworks that give rise to negative dependence are those where the increase of the one factor is associated with other influences that lead to the decrease of the other. One such example, that we will develop in some detail in the empirical section of this study, is the negative dependence between the size of the capital base of a firm and the rate of return of capital.

Moreover, the existence of negative dependence, which speaks for the dominant underlying relation, does not preclude the occurrence of “positive relation" events. For example, while indeed selling prices tend to be negatively correlated with quantities sold, low prices-low quantities as well as high prices-high quantities are not impossible, or even very rare, events. Therefore, apart from modeling what happens along the “negative dependence” axis, it is of importance to capture also the characteristics of the relation along the positive dependence axis, which although weaker and less frequent, do also materialize. This introduces more strongly the possibility of asymmetries, and the Stingray copula that we will present in this study can model asymmetries as regards positive dependence. As an example, consider the relation between family poverty and educational achievement: the negative relation between the two appears indeed to be documented. But what happens with the joint events of positive relation, “high poverty-high educational achievement” , , and also “low poverty-low educational achievement”, ? One could plausibly argue that the event may be more frequent than the event because educational achievement can become an instrument for socio-economic advancement. Ultimately this is a matter of empirical investigation, but the prospect of asymmetry in the joint probabilistic structure is there, and it requires a tool capable of modeling such asymmetries.

Negative dependence has received rather less attention than positive dependence in the literature. To provide an informal metric on a natural experiment, the Karlin and Rinott [

1] paper pertaining to positive dependence has exactly five times more citations in Google Scholar as of December 16th 2025, from its twin paper Karlin and Rinott [

2] that examines topics related to negative dependence.

1

This is perhaps due to the fact that, for the bivariate case, as Drouet Mari and Kotz [

10] [pp. 43-44] mention, the results for negative dependence are mostly a `minus’ sign, or a reversion of an inequality, away from the results for positive dependence. To put it in a more direct way, negative dependence between a variable

U and a variable

V is equivalent to positive dependence between

U and

.

While this is not disputable, the implied tactic for applied research is not really productive.

2 This tactic would advise, “if you have negative dependence between two variables and you need to model it, multiply one of the two data series by

, and use a copula that reflects positive dependence”. There are at least three reasons why this approach is problematic: first, it is not at all certain that this `sign-flip’ will not conflict somewhere with the computational environment and estimation strategy and code used by the applied researcher, for reasons that have to do with software languages and their computational conventions (or the coding habits of the researcher). And the more complex this environment, the more time-consuming will be to audit it and adjust it in order to work smoothly with the sign-flipped data series. Second, we sometimes need to apply data transformations that cannot be used with negative data, the logarithm being the obvious example. Third, even if we manage to overcome these hurdles, once we’re done with estimation, we will have to spend extra amounts of time in order to translate the software output back into what actually holds, both in order to do inference and also to prepare it for presentation to whoever is expecting it.

Overall, the frequent occurrence of negative dependence together with the above mentioned realities of applied research make the development of bivariate negative dependence structures worthwhile, if our interest also lies in providing tools for empirical research.

The relative sparsity of statistical tools as regards negative dependence is also present in the copula field. Inspecting Table 4.1 of Joe [

11] [p. 161], only six out of the 29 copulas listed can represent negative dependence.

3 Moreover, and apart for workhorses like the Gaussian and Frank copulas (to which we will return), in many if not all other cases, the achieved strength of negative dependence is low, or it reaches the theoretical extreme at the price of sacrificing a considerable part of the copula support.

A well-known example here is the benchmark bivariate “Clayton” copula, when the range of its parameter is extended to include

.

4 While it can reach the extreme value

for Kendall’s

, it loses support. In order to have

it must shed

of it, while at the extreme

, only half of the support remains. As Joe [

11] [p.168] comments, due to this “the extension is not useful for statistical modeling.”

Analogous is the case in a recent proposal for a copula dedicated to modeling negative dependence by Ghosh, Bhuyan, and Finkelstein [

12]. They manage to allow for the full negative range

of concordance measures like Kendall’s

, but their copula is a piece-wise function that early on excludes whole areas of the

support as dependence becomes visible and increases (see their scatter plots in their

Figure 3, p. 1336). To give two specific examples, for

,

of

is excluded, while for

we lose 45% of the support area.

The one-parameter bivariate Stingray copula that we present here, is also constructed to represent exclusively negative dependence. It is generated by a mathematical device that, to our knowledge, has not been used previously to create copulas. Still, it remains simple and transparent. It does not reach the strongest degree of dependence but it still goes beyond the point where other copulas stop, and it maintains fully its support throughout. We do not consider the fact that it does not reflect the theoretically maximum degree of dependence as compromising its usefulness for empirical work, especially in the social sciences where very strong dependence is the exception and not the rule. Moreover, the Stingray copula is asymmetric as regards the “positive correlation” joint events as we will see.

The rest of the article unfolds as follows: in

Section 2 we present the basic mathematical functions (copula, conditional copulas and the copula density), and we provide visual input for an intuitive understanding on how dependence looks like under the Stingray. We also provide some probabilistic intuition related to its mathematical from. In

Section 3 we present some of the main negative dependence properties that characterize our copula. In

Section 4 we first compute the three main concordance measures (Kendall’s tau, Blomqvist-beta and Spearman’s rho), and then we compare the Stingray copula to other bivariate distributions and copulas that can model negative dependence, in terms of their reach.

Section 5 contains a simulation study to showcase the individuality of the dependence reflected by the Stingray copula against two all-purpose copula juggernauts (Gaussian and Frank). In

Section 6 we develop a simple specification/goodness-of-fit test, and in

Section 7 we fit the Stingray copula to an economic data set, exploring the relation between capital and its rate of return.

Section 8 concludes. Some mathematical calculations and proofs are collected in the Appendix.

2. The Stingray Copula

We consider a copula representation

for the joint distribution of two random variables

with absolutely continuous distribution functions

, where

u and

v are realizations from Uniforms (0,1). The new copula we present is

Using each variable also as an exponent to the other, is a mathematical device that we have not seen previously in the construction of copulas. This function is grounded and has the proper margins,

It is also 2-increasing (i.e it satisfies the rectangle inequality). When the copula density exists this is equivalent to the copula density being non-negative (Joe 13, p.12). This is the case here given the restriction on the dependence parameter .

The copula is obviously symmetric in its arguments (but that does not mean that the allocation of joint probabilities is symmetric over the unit square). As we show later, its partial second derivatives are both positive, so it is subharmonic. Moreover, for we get , the Independence copula, which is the one focal copula that is attainable here. Nesting the Independence copula is important for empirical work, because whether dependence exists or not in the first place is of importance, especially for quantitative research in the social sciences, where statistical results offer critical support to causality arguments.

The conditional copulas are

These can be used to simulate series that follow the Stingray copula, by the conditional distribution method (Nelsen 14, p. 41). We will also use them in deriving various properties of our copula, and also, in the empirical illustration of the paper in order to perform a goodness-of-fit test that begins with the Rosenblatt transform.

2.1. The Copula Density

One can verify by computation that the copula density is everywhere non-negative for

. Indicatively, we have

and these limits are non-negative for

.

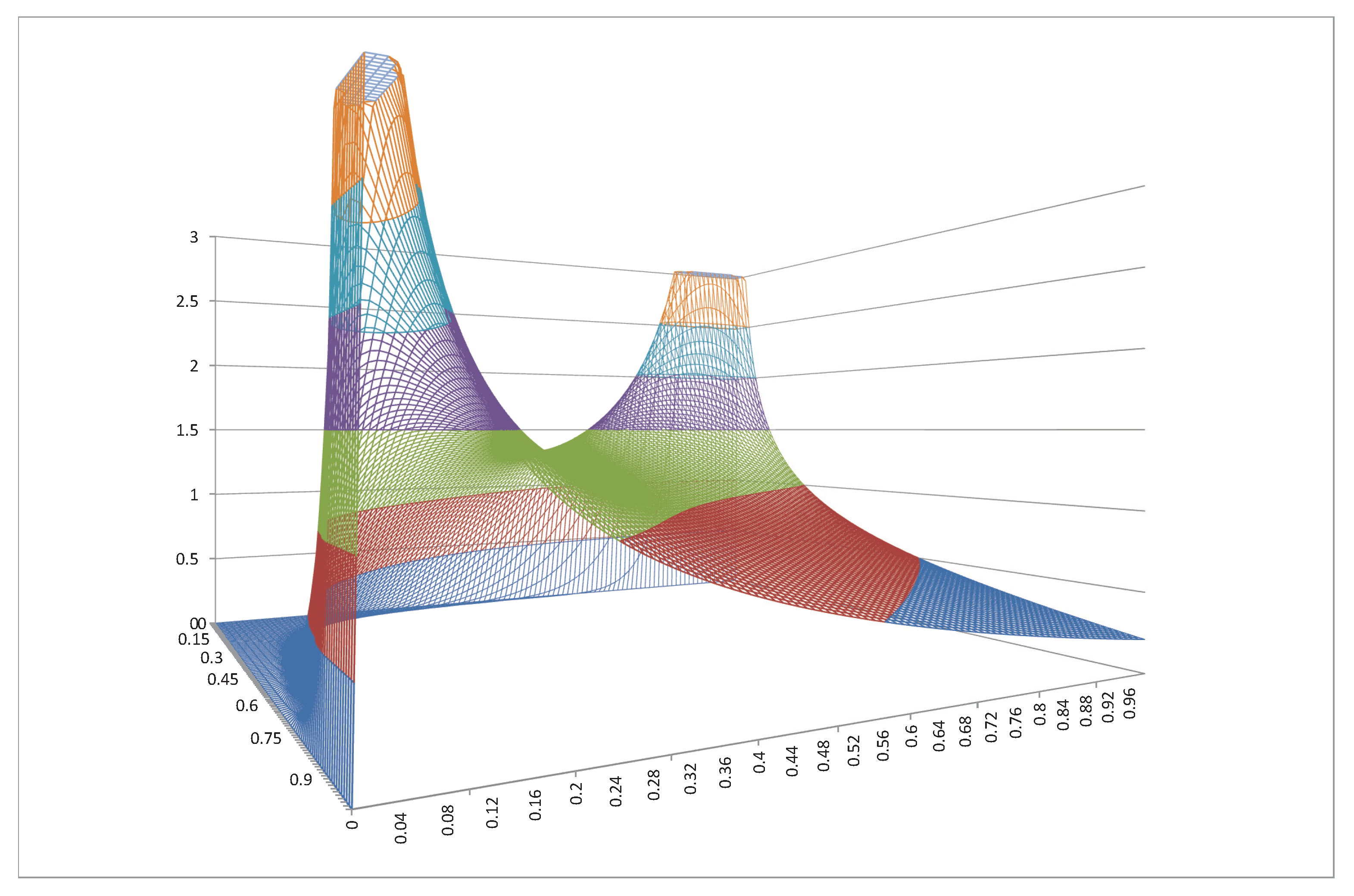

A 3-D image for this density is provided in

Figure 1.

5 The tip of the graph is at the

point, and it touches zero for

.

2.2. Scatterplots and Negative Dependence

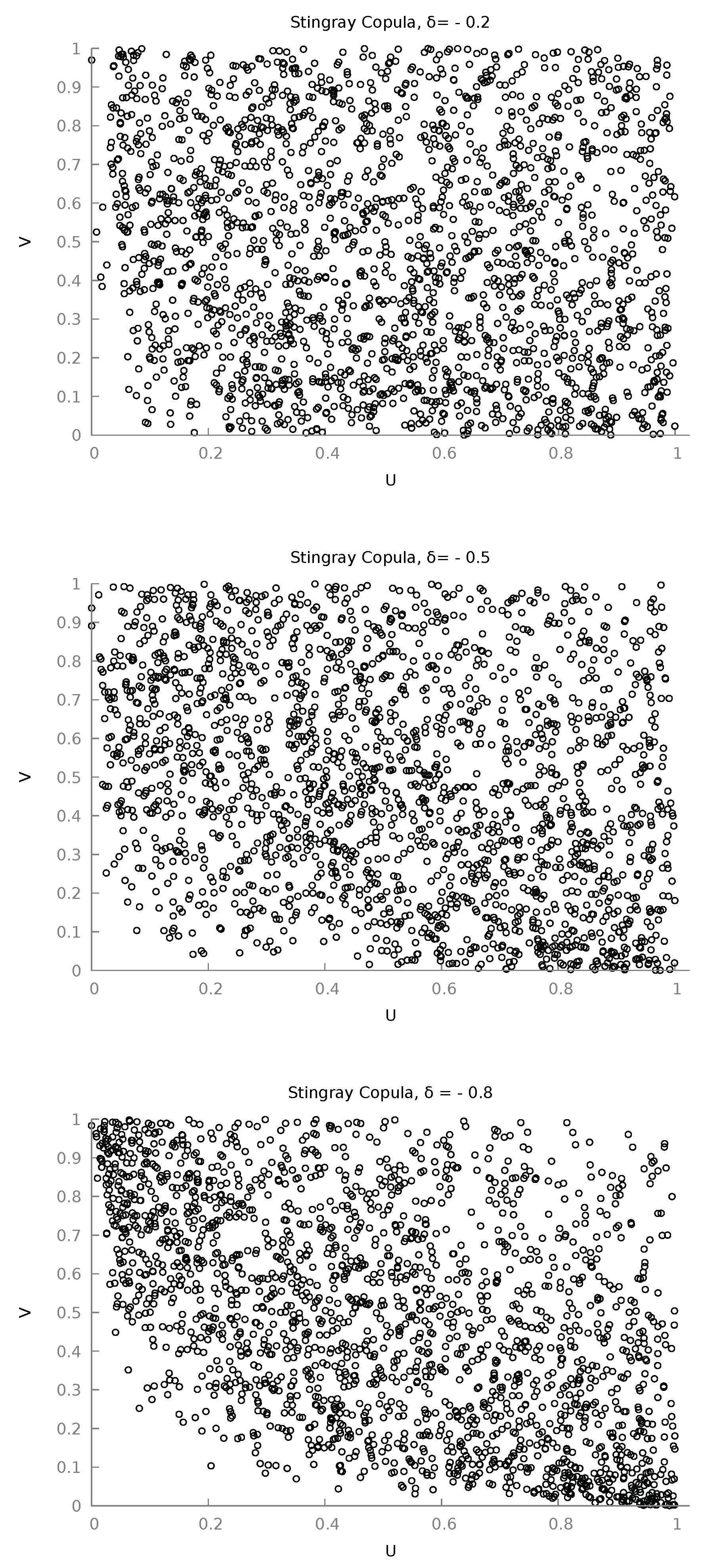

To obtain further visual intuition of the structure reflected by the Stingray copula we present in

Figure 2 three scatter plots of

for three different values of

, using 2,000 realizations.

The “convexity to the origin” that is clearly visible in the last scatter plot (

) is observable in other copulas also. For example, Nelsen [

14] pp. 120-122 provides scatter plots of several Archimedean copulas, and among them there are five that exhibit this characteristic for some value of their parameter (they are, using the book’s numbering, 4.2.1, 4.2.2, 4.2.7, 4.2.15, 4.2.18). In fact they have it much more sharply, and this is no accident; in all cases, these are copulas that use the

device to keep the copula positive, and forcibly impose this no-probability land near the origin (and so for jointly low-probability events). As regards the direction of dependence, the scatter plots of

Figure 2 show also that it is negative, as the copula density graph did previously. More formally we have

Since

, this implies that as

increases in absolute value,

decreases. The four fundamental underlying joint probability events for given

are

These relations formalize the result that as the negative moves towards its lower bound , it is the last two joint events, which represent negative dependence, that acquire higher probability. Visualizing the joint support on the plane as a unit square, as moves towards , probability mass moves towards the upper left and the lower right region, deserting the lower left and upper right ones.

2.3. Some Probabilistic Intuition

We have mentioned that the mathematical device of using one of the copula variables as an exponent to the other appears to be something novel. We next show how one can link this to probabilities and understand in a more intuitive way why the Stingray copula represents negative dependence, and why it is asymmetric on the two corners of the positive diagonal. We start by manipulating the copula as follows (using the fact that

is negative):

So the Stingray copula can be seen as adjusting the Independence copula by the factor to the right. We note that negative dependence implies that the fundamental joint probability of same-direction inequalities is smaller than the probability under Independence, and the adjustment factor above is always smaller than unity. Hence we get , which is why the Stingray copula reflects negative dependence.

We turn now to the issue of asymmetry along the positive diagonal in the unit square. For clarity, let’s examine the case where

. We also have the correspondences

Then we can write, say for the first component of the adjustment factor,

If we examine a value for

Y below its median

, we have

and the exponent in the expression will be higher than unity and it will reduce the value of this adjustment component,

When the Stingray copula evaluates “probabilistically low" intervals for

Y, the corresponding marginal probability for

X is lowered in value as a contributor to the adjustment factor, tending to strengthen the latter’s effect towards negative dependence. Now,

meaning that as

approaches zero from below it weakens the effect of the exponent, operating as a regulator of the strength of the relation, on top of its inherent tendency towards negative dependence. The same analysis holds identically for the other component of the adjustment factor. Combining the two, explains why there is no symmetry between what happens to the lower-left part compared to the upper-right part of the scatter plots shown before. If we look at events where the chosen

, both components of the adjustment factor will tend to increase its value, hence we will get more probability mass in the upper right quadrant than in the lower left quadrant. The whole adjustment factor is the geometric mean of the two, and it reflects both negative dependence and this asymmetry along the positive diagonal. Moreover, this analysis shows that one could explore an asymmetric version of the Stingray Copula, where only one of the two components of the adjustment factor is present, say,

But we leave that for future research.

3. Negative Dependence Properties

In this section we state some of the negative dependence properties of the Stingray copula. For the tail properties we will present also natural extensions of the properties usually mentioned in the literature, now for the negative-dependence tails.

3.1. Quadrant Dependence

The Stingray copula is Negative Quadrant Dependent (NQD),

Under negative dependence, joint same-direction inequality events have everywhere lower probability of occurring compared to the corresponding joint events under independence. This is an intuitive way to understand negative dependence. It also implies that for strictly increasing transformations

of the underlying random variables

, including the identity transformation, the covariance will be non-positive,

3.2. Reverse Rule of Order 2

The Stingray copula is

(“reverse rule of order 2”).

6 Following Joe [

13 p. 23, we express this as

The property can be proved by direct application of the definition.

3.3. Concordance Ordering

Our copula is concordance-increasing (Joe 11, pp. 51-52) in the sense that

This comes directly from the earlier result eq. (

5), that the derivative of the Stingray copula with respect to

is everywhere positive. If we examine a higher

, i.e. a

closer to zero, we get less negative dependence and so more concordance. This aligns with the fact that for

we get statistical independence.

3.4. Stochastic Monotonicity

The Stingray copula is stochastically decreasing (SD),

As we examine higher and higher

y-values, the probability that

X exceeds any given threshold is decreasing. The same holds for

Y given

. This is essentially the “regression dependence” property of Lehmann [

3], but using the complementary probability which is more intuitive, linking an increasing derivative with positive dependence and a decreasing one with negative. The SD property implies, but is not implied by, negative quadrant dependence, but we stated NQD first due to its conceptual importance. We provide the proof of the SD property in the Appendix, where essentially we show that the Stingray copula has positive second partial derivatives (which is what makes it subharmonic also).

3.5. Tail Monotonicity

Stochastic monotonicity implies also tail monotonicity (see Nelsen 14, Th. 5.2.12, p. 197). For the case of negative dependence this means that the Stingray copula is

-

Left-Tail Increasing (LTI),

This result, although certainly linked to negative dependence, does not provide an intuitive description that invokes the latter, and we will remedy this a few lines below.

-

Right Tail decreasing (RTD),

Here we can say that as we increase x the probability that Y exceeds any given threshold decreases, which is a good way to think about negative dependence.

We get the same results if we switch places between X and Y.

In preparation for the four tail-dependence coefficients that we will examine immediately after (for a reason), we note that while for the concept of stochastic monotonicity the adjectives “left-right’ are used, for the concept of tail dependence the literature uses “lower-upper” instead, to refer to the same two tails of a univariate distribution. But the bivariate copula has four tails in the plane, and we are particularly interested in the two that are not depicted by the above probabilities. We want the probabilities where the conditioning event has an inequality of opposite direction, and thankfully, combining these two pairs of words we can categorize transparently without confusion.

Keeping the unit square in mind and also the conventions that we linked

X to

u and then we put

u on the horizontal axis, we have that if the "left tail" is in reality the

lower left one when we look at a bivariate copula, we can examine what happens to the (upper) left tail by

We see from eq.(

8) that if the copula is “lower Left Tail Increasing”(LTI), it will necessarily be “upper Left Tail Decreasing”. Looking at the probability characterizing the upper left tail, we could describe this by saying that as we

decrease x, the probability that

Y exceeds any given threshold increases, and this is an intuitive description of negative dependence.

Also, if the “right tail” is the upper one, we can examine the lower right tail by

Here, from to eq.(

9) we see that if the copula is “upper Right Tail Decreasing” (RTD), it will necessarily be “lower Right Tail increasing”, that can be translated as “when we increase the value

x, the probability that

Y is below any given threshold increases”, and this, again, is an intuitive description that pertains to negative dependence.

Table 1 summarizes these interrelations.

We close this section by examining tail dependence.

3.6. Tail Dependence

As in the previous section we will examine four cases, in relation now to tail dependence, while usually only two are examined, the “upper” (meaning “upper right”), and the “lower” (meaning “lower left”), corresponding to the two corners along the positive dependence diagonal in the unit square. We will also examine the other two corners, those along the negative dependence diagonal. Here, the literature standard is to use

L for “lower” (and not for “left”) and

U for “upper”. We have the tail dependence coefficients

We kept the standard notation

and we made the other two fully transparent, sacrificing compactness. Due to the permutation symmetry of the copula we have

The results for the Stingray copula are as follows:

We provide the calculations in the Appendix, and we have also verified them by computation. The Stingray copula does not in general exhibit “tail dependence” (joint events of extreme probabilities), except if it represents the maximum dependence allowable, in which case the negative dependence extreme events maintain at the limit non zero probability of occurring.

4. Negative Concordance Measures and Competitors

In this section we first compute three basic concordance measures, Kendall’s , Blomqvist- and Spearman’s , and then we compare their maximum values (in absolute terms) with other copulas that can represent negative dependence, extending also the comparison in terms of Pearson’s correlation coefficient.

4.1. Kendall’s

Kendall’s

concordance coefficient can be expressed as

We show in the Appendix that for the Stingray copula we arrive at

We computed this double definite integral for the deciles of

using three different software.

7 They agreed, and its value is remarkably stable very near

. We will provide these values in a while, for the moment, this implies that a good estimate for

can be obtained by the sample estimate of Kendall’s

,

The maximum value in absolute terms of Kendall’s tau for the Stingray copula is

. As Nelsen [

16] shows, Kendall’s tau is also an average measure of the

property.

4.2. Blomqvist- (Medial Correlation)

The Blomqvist-

coefficient, often closely related to Kendall’s tau, is computed as

For the Stingray copula we have

Its maximum value in absolute terms is

4.3. Spearman’s

Spearman’s

is computed as

For the Stingray copula its maximum value in absolute terms is

While the value of this double integral changes as

changes, there is a nearly linear relation between

and

,

So,

can be seen approximately as the Spearman’s rho that holds in the data relative to the maximum

value that the Stingray copula may acquire. In turn, Spearman’s rho is an average measure of quadrant dependence,

8 and we will exploit this connection in the specification/goodness-of-fit test that we present later.

In

Table 2 we present the related detailed values.

From

Table 2 we see how closely Blomqvist-

is to Kendall’s tau for all values of

. We also note that the Kendall’s tau value of

means that there is

chance that the two random variables will move in opposite directions.

4.4. Judgment Day

How does the Stingray copula fare against other bivariate distributions and copulas that can represent negative dependence?

We start with something that we haven’t yet touched upon, namely, Pearson’s “linear” correlation coefficient

. This is a measure of dependence that is not margin-free, and this perhaps reduces its importance as a core feature of a copula. To the theorist. Because the applied researcher will almost always compute it and think about what it reveals. This is the same applied researcher that previously would want to keep its data on the positive axis, and negative linear correlation between two non-negative random variables has constraints. Moran [

18] showed that for such a pair Pearson’s

cannot reach the value

. Intuitively, this is due to the asymmetry in the support, where one variable is free to go to infinity while the other cannot go below zero. Moreover, the lowest possible value for

is determined by the marginal distributions (while the properties of their joint distribution may shrink this value even closer to zero). For the case of two Exponential variates, this lowest possible value is

. Papadopoulos, Parmeter, and Kumbhakar [

19] compute the same bound for two Half-Normal random variables as

.

An example of further restriction due to the joint distribution is Gumbel [

20] who presents a bivariate distribution with Exponential margins and with only negative dependence, where

. Another example is the bivariate Exponential Extension of Freund [

21] that stops at

(the margins here are mixtures of Exponentials). Papadopoulos et al. [

19] have examined a bivariate Truncated Normal that has Truncated Skew Normal margins, whose correlation coefficient cannot go below

. In comparison, we present in

Table 3 estimated correlation coefficients between variables that obey pairwise the Stingray copula, and have various margins, namely, Half-Normal (HN), Exponential (Exp), Generalized Exponential (GE, see Papadopoulos 22), but also of two-sided variables following the Normal (N) and the Laplace (L), in identical pairs but also in-between them (based on 10,000 bivariate Stingray draws with

).

From

Table 3 we obtain evidence that compared to the aforementioned bivariate distributions, the Stingray copula does better, in terms of Pearson’s

, in the sense of allowing for stronger negative linear dependence.

We turn now to copulas proper. We have already discussed in

Section 1 the MTCJ (“Clayton”) copula and another newly proposed, that exceed the capabilities of the Stingray but at the expense of a seriously restricted support. Regarding other well-known copulas that can model negative dependence without losing support, the Farlie-Gumbel-Morgenstern does not go below

,

, and

, while the Ali-Mikhail-Haq copula can go down to

and

, but not more (for the latter see Genest and MacKay [

23] for a simple computational formula). Chesneau [

24] recently developed a two-parameter modification of the MTCJ copula. This copula maintains its full support when it represents negative dependence, but it has

,

. The Stingray copula has

,

, and

, and hence has a higher reach in terms of all three concordance measures compared to these three copulas.

But we still have to face the big players in the room, and we have specifically in mind the Gaussian, Student’s-t, the Plackett and the Frank copulas, that are very popular and do allow for full negative dependence in terms of concordance measures.

As regards the Gaussian copula, we find that in order to reflect negative dependence higher than the Stingray in terms of Kendall’s tau, Blomqvist’s or Spearman’s rho, it must be the case that its parameter falls below (the Student’s-t-copula has the same expression for as the Gaussian, so the same conclusion holds for it). As regards the Plackett copula, that can represent negative dependence when its parameter is in , we find that related to Spearman’s rho, we must have to go beyond what the Stingray copula can represent, while as regards Blomqvist-, we must have . These copulas are comparable to the Stingray copula in the sense that their dependence parameter has a restricted support. And we see that they surpass the capabilities of the Stingray only after exhausting a large part of it, which allow us to argue that the Stingray is competitive, even here. But the Frank copula has an unrestricted dependence parameter, so, in the next section we provide an alternative comparison.

5. Individuality of the Stingray Copula: Simulation Study

In this section we present a simulation study to show that the negative dependence represented by the Stingray copula is decisively distinct from that represented by the Gaussian and Frank copulas.

We generated draws from the Stingray copula, for

(so for Kendall’s

), and for sample sizes

100, 200, 500, so nine worlds in total. In each world we did 1,000 repetitions, and for each repetition we executed the likelihood test of Vuong [

25] for non-nested likelihoods, between the Stingray and the Gaussian, and between the Stingray and the Frank copulas. This is a test whose null hypothesis is that the two contestant specifications are observationally equivalent, and the test is either inconclusive or it favors one of the two. In each of

Table 4 and

Table 5 we report the proportion of times the test statistic favored mathematically the Stingray (and vice versa), and also the proportion of times the test statistic formally designated the Stingray copula as a better fit for the data (and vice versa), with 90% statistical confidence. In the Tables,

S represents the Stingray,

G the Gaussian and

F the Frank copula.

It is clear from the Tables that even with a small sample of and rather low dependence , the Vuong test almost all of the times detects that the Stingray is a better fit for the data (upper parts of the two Tables), although it needs a sample of to decisively declare it the winner, in more than 80% of the times (lower parts of the Tables). When dependence strengthens at (Kendall’s ), it only needs a sample size of 200 to be able to say that. This shows that irrespective of the flexibility that characterizes the Gaussian and Frank copulas, the dependence structure reflected by the Stingray copula has individuality, namely, it is particular enough to warrant its own distinct model. The fact that both the Gaussian and the Frank copulas are symmetric as regards the allocation of joint probability mass in the the unit square, while the Stingray copula can reflect asymmetries in that respect, is the main discriminating factor here.

6. Specification Testing Under Quadrant Dependence

There are many specification/goodness-of-fit tests that have been developed for copulas (see

e.g. Genest, Rémillard, and Beaudoin 26 for review and comparisons). Here we devise a specification test that exploits the property of quadrant dependence, and is simple to implement. The first step is to transform the specification test into a test for independence by using the Rosenblatt transform presented originally in Rosenblatt [

27]. Then we use the fact that under quadrant dependence (positive or negative), Spearman’s rho, except of being a measure of concordance, becomes also a measure of dependence, measuring the distance of the copula from the Independence one, and representing Independence if and only if it is zero. The property of quadrant dependence is essential because in general zero concordance does not imply independence.

In the bivariate case, Rosenblatt’s transform amounts to test for independence each of the following two bivariate vectors separately:

At the same time, when negative quadrant dependence exists as a property, a proper measure of dependence, Schweizer and Wolff’s

(see Nelsen 14, p.209), is equal to the negative of Spearman’s rho:

Since the asymptotic distribution of

under the null Hypothesis is zero-mean Normal, the opposite sign does not affect the conclusion of the statistical tests. So we can test as usual the hypothesis that

is statistically zero, between the two pairs of vectors separately that reflect Rosenblatt’s transform.

9

If this independence hypothesis holds, then the data follow the prescribed copula, as a theoretical certainty for the populations involved. In the actual world where things are never exact and standard errors get in the way of sharpness, if we fail to reject the null hypothesis of independence, at the minimum we can conclude that the specified copula works well with the data.

7. An Empirical Illustration

Among business persons and economists alike, there is, broadly speaking, an anticipation that the gross rate of return of capital tends to be negatively associated with the level of capital employed. Let

X represent capital and

W its returns, so

is the rate of return. We expect that

W increases with

X, but if it increases by less in proportional terms, then

X and

Y will be negatively correlated. Moreover the relationship is expected to be asymmetric along the positive correlation axis, with higher frequency in the “high-high” (upper right) quadrant compared to the lower right quadrant. We summarize the situation in

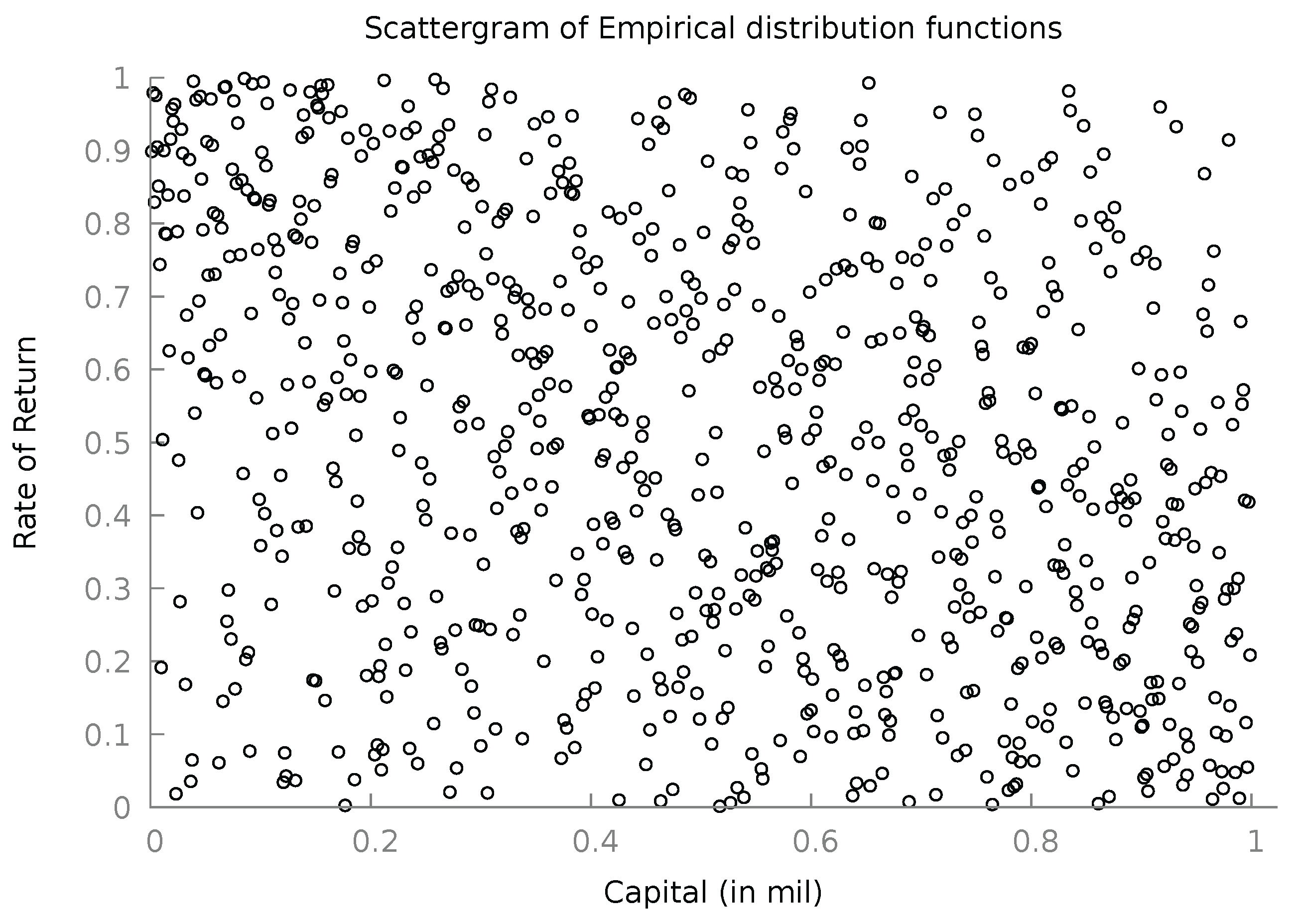

Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Magnitude of the capital base and its rate of return.

Figure 3.

Magnitude of the capital base and its rate of return.

The negative relation is expected to appear, first because as a firm expands its operations (high capital), it may encounter non-scalable or semi-scalable inputs which will bring about decreasing returns to scale, but also it will trigger antagonistic competition forces that may force the firm to offer lower prices than before, and hence lower returns although not lower capital (this is quadrant D of

Figure 3). At the same time, the “low capital-high returns” event (quadrant A) represents smaller firms that are highly efficient and maintain their place in the market due to their positive economic results and dynamism. And these indeed are the most frequent situations we encounter in open markets. As regards the positive dependence diagonal axis, the event “high capital-high returns” (quadrant B) is also observed when we have strong market power and domination that allows the firms to extract economic rents and thus higher returns, while the case of “low capital-low returns” (quadrant C) is relatively less likely, since in a more or less well-functioning market such firms have low probability of survival, leading to them being the smallest subset of firms.

In this context, we examine a cross-sectional sample of

Greek firms in the Buildings Construction sector (the 3-digit NACE rev2 classification is “412-Construction of residential and non-residential buildings”). The sample uses 2019 balance sheet data. We measure Capital Assets (CA) in the balance sheet as the sum of Fixed Assets and Inventory. As a measure of capital returns we take the EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest Taxes Depreciation and Amortization), which is standard international practice. Its ratio to the Capital Assets is the (gross) rate of capital returns (

). We then compute the empirical distribution function of these two variables, CA and

using for each

In

Figure 4 we present the scatter plot of the empirical distribution functions of CA and

.

A cursory look may create the impression that there is not statistical dependence worthy of discussion in

Figure 4. But Pearson’s correlation coefficient (among the original variables) was estimated as

, Spearman’s rho as

, and Kendall’s tau as

. Not strong, but not negligible, and statistically non-zero. A calmer look at the scatter plot reveals the mild concentration of points along the negative diagonal, while enough points are to be found in the upper-right and lower-left regions. This is exactly the territory of the Stingray copula, where the real world ranges in the whole unit square, but has some negative association without being too vocal about it.

We start with the specification test presented in the previous section. We make the test more strict by testing in parallel for a zero Kendall’s tau (which also follows asymptotically a zero-mean Normal under the null hypothesis). This creates four possible outcomes: , , , . From these four, the first three lead to the rejection of the null hypothesis and of the specification. This is because the third possible outcome, , even though it has , it is accompanied by the contradictory result . It is contradictory because under quadrant dependence is a measure of dependence while is still only a measure of concordance. And we cannot have zero dependence and non-zero concordance, hence this result is a sign of general misspecification. Only permits us to defend the specification under examination.

We computed

and

using the Stingray copula with

, we estimated non-parametrically their

and

with

u and

v respectively , and we tested for zero Spearman’s rho and zero Kendall’s tau following Genest and Favre [

28]. The results are presented in

Table 6.

From

Table 6 we see that the estimated sample concordance/dependence measures are already very small, and even though the large sample size leads to a low standard error of each statistic, still, the

p-value of the test is very high in all four cases. Therefore we can conclude that both these measures are zero, and so, that the necessary and sufficient condition in the context of the Rosenblatt transform cannot be rejected, and that the Stingray copula can be considered an adequate modeling device for the specific data set.

8. Conclusions and Further Research

We have presented a new single-parameter bivariate copula, baptized the Stingray copula, that specializes in representing negative dependence. It has stochastic and tail monotonicity (for negative dependence), it is concordance-increasing, Reverse Rule of order 2 and negative quadrant dependent. It can accommodate stronger dependence than comparable existing copulas in terms of concordance measures like Kendall’s tau and Spearman’s rho, and without losing any part of the support. It performs competitively with benchmark flexible all-purpose copulas like the Gaussian and the Frank, and it reflects a negative dependence structure that is not similar to what these copulas can model. It also outperforms bivariate distributions in terms of Pearson’s for various non-negative and two-sided margins. These results make it a potentially useful tool for statistical empirical work.

On the theoretical front, there appear at least four possible avenues for future research: the first is the prospect of increasing the number of its parameters in order to extend further its reach –but this must be balanced against the unavoidable complexity that it may create in handling and estimation matters. The second is the question as to whether it can be extended to accommodate more than two variables. The third, is the development of the survival function and the Stingray survival copula, but based on the logic of negative dependence, namely for events and vice versa. Finally, the Stingray copula generates the dependence by making the one variable operate also as an exponent to the other, something novel as far as we were able to check. We provided some probabilistic intuition as to how this works, and it is a device that could possibly be used more generally to construct new copulas.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data sample used in this study is available as a .txt supplementary file, accompanied by a “README” explanatory .txt file.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

| TLA |

Three letter acronym |

| LD |

Linear dichroism |

Appendix A.

Appendix A.1. Derivatives of the Stingray Copula Eq. (2) and (3).

We apply semi-logarithmic differentiation on the copula function,

Due to permutation symmetry, will have the exact same form, with swapping places.

Appendix A.2. The Copula Density Eq. (4).

Appendix A.3. The Derivative ∂C(u,v;δ)/∂δ, Eq.(5).

since is negative.

Appendix B. Dependence Properties

Appendix B.1. Reverse Rule of Order 2

Now, since

,

positive and smaller than unity, and

, it follows that

Then we have the result

and the initial inequality is verified.

Appendix B.2. Stochastic Monotonicity ( SD )

We want to verify the direction of the inequality in eq. (

6)

Permutation symmetry will then take care of the twin property eq. (

7).

We compute (ignoring the factor

and keeping in mind that there will be a minus sign in front)

Since we are interested only in the sign we now ignore the terms outside the curly brackets that are positive and focus on the expression inside. Define

Then the expression inside the curly brackets can be written

This is a quadratic polynomial in

w. Its discriminant

is

Over the allowed values for

and

u,

changes sign. So the polynomial has real roots for some combinations of

. For these combinations, whichever they are, we have the roots

To prove the SD property we need the polynomial to be positive. So we need

w to be always above its higher root, namely we require

Note that the components inside the square on the left side are positive. Decomposing the square, we want

Ignoring the first two terms on the left hand side (both positive), it suffices to show that

But this last inequality holds, because and . So the polynomial in w is always positive, either because its discriminant is negative or because of the just proven inequality. This implies that , and remembering the minus sign in front of it we obtain , proving the SD property.

Appendix B.3. Tail Dependence

We first examine

and

. We have

This leads to the indeterminate form

. We apply l’Hôpital’s rule and compute the derivative of the numerator (the derivative of the denominator is

). Applying semi-logarithmic differentiation,

Moving to the negative dependence corners, we have, due to permutation symmetry,

. We examine

We have, for the first and third component,

The second result uses .

For the second component

when

its

limit evaluates to 0 making

and the lambdas also zero, as it should be expected since for

, there is no dependence at all.

When

, its limit evaluates to

(since

.) Applying l’Hôpital’s rule, we want to evaluate the limit,

For

we have evidently

So for

we have

Appendix B.4. Kendall’s τ

We derive eq. (

13). To compact notation, we will omit the arguments from the copula function and density, writing simply

C and

c.

Kendall’s

is expressed as

Using the expression of the Stingray copula, we have

Inserting this into the expression of

we have

Next, we can manipulate in abstract the initial integral as follows, using integration by parts:

This leads to the indeterminate form

. Applying l’Hôpital,

because

.

Inserting these results to the Integral expression, we have

So an alternative expression for Kendall’s

is

Equating expressions (

A1) and (

A2), we have

Inserting this back into eq. (

A1) we have

Finally, we have

and this is what we wanted to show.

References

- Karlin, S.; Rinott, Y. Classes of orderings of measures and related correlation inequalities. I. Multivariate totally positive distributions. Journal of Multivariate Analysis 1980, 10, 467–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlin, S.; Rinott, Y. Classes of orderings of measures and related correlation inequalities II. Multivariate reverse rule distributions. Journal of Multivariate Analysis 1980, 10, 499–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, E.L. Some concepts of dependence. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics 1966, 37, 1137–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jogdeo, K.; Patil, G. Probability inequalities for certain multivariate discrete distribution. In The Indian Journal of Statistics, Series B; Sankhyā, 1975; pp. 158–164. [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahimi, N.; Ghosh, M. Multivariate negative dependence. Communications in Statistics-Theory and Methods 1981, 10, 307–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, H.W.; Savits, T.H.; Shaked, M. Some concepts of negative dependence. The Annals of Probability 1982, 10, 765–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joag-Dev, K.; Proschan, F. Negative association of random variables with applications. The Annals of Statistics 1983, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Yang, J. Further developments on sufficient conditions for negative dependence of random variables. Statistics & probability letters 2004, 66, 369–381. [Google Scholar]

- Amini, M.; Nili Sani, H.; Bozorgnia, A. Aspects of negative dependence structures. Communications in Statistics-Theory and Methods 2013, 42, 907–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drouet Mari, D.; Kotz, S. Correlation and dependence; Imperial College Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Joe, H. Dependence modelling with Copulas; CRC Press: Boca Raton FL, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, S.; Bhuyan, P.; Finkelstein, M. On a bivariate copula for modeling negative dependence: application to New York air quality data. Statistical Methods & Applications 2022, 31, 1329–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joe, H. Multivariate models and multivariate dependence concepts; CRC press, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Nelsen, R. An Introduction to Copulas, 2nd ed.; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Karlin, S. Total positivity; Standford University Press, 1968; vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Nelsen, R.B. On measures of association as measures of positive dependence. Statistics & probability letters 1992, 14, 269–274. [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishnan, N.; Lai, C.D. Continuous bivariate distributions, 2nd ed.; Springer, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Moran, P.A.P. Testing for correlation between non-negative variates. Biometrika 1967, 54, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadopoulos, A.; Parmeter, C.F.; Kumbhakar, S.C. Modeling dependence in two-tier stochastic frontier models. Journal of Productivity Analysis 2021, 56, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumbel, E.J. Bivariate Exponential distributions. Journal of the American Statistical Association 1960, 55, 698–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, J.E. A bivariate extension of the Exponential distribution. Journal of the American Statistical Association 1961, 56, 971–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, A. Stochastic frontier models using the Generalized Exponential distribution. Journal of Productivity Analysis 2021, 55, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genest, C.; MacKay, R.J. Copules archimédiennes et familles de lois bidimensionnelles dont les marges sont données. Canadian journal of statistics 1986, 14, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesneau, C. Proposal of a Modified Clayton Copula: Theory, Properties and Examples. European Journal of Statistics 2024, 4.9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuong, Q.H. Likelihood ratio tests for model selection and non-nested hypotheses. Econometrica 1989, 57, 307–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genest, C.; Rémillard, B.; Beaudoin, D. Goodness-of-fit tests for copulas: A review and a power study. Insurance: Mathematics and economics 2009, 44, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblatt, M. Remarks on a multivariate transformation. The annals of mathematical statistics 1952, 23, 470–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genest, C.; Favre, A.C. Everything you always wanted to know about copula modeling but were afraid to ask. Journal of hydrologic engineering 2007, 12, 347–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Notes

| 1 |

Of course, negative dependence has been examined in certain detail. Apart from the general books on copulas included in the References, indicative literature includes Lehmann [ 3], Jogdeo and Patil [ 4], Ebrahimi and Ghosh [ 5], Block et al. [ 6], Joag-Dev and Proschan [ 7], Hu and Yang [ 8], Amini et al. [ 9]. |

| 2 |

I would like to thank professor Christian Genest for his helpful comments and suggestions on an earlier draft of this work. |

| 3 |

Amusingly, this is again a five-to-one ratio in favor of positive dependence, as was with the two Karlin and Rinott articles mentioned earlier. |

| 4 |

Wrestling with Stigler’s law of eponymy, Joe [ 11] dutifully calls this copula “Mardia-Takahasi-Cook-Johnson” (MTCJ), writing (p. 170) “The abbreviation to MTCJ follows the abbreviation style of FGM used for Farlie-Gumbel-Morgenstern; the initial C can also include Clayton for the bivariate copula.” |

| 5 |

The pectoral fins in the negative diagonal go much higher and are truncated here for visual convenience. |

| 6 |

It appears that Samuel Karlin has sown some confusion related to terminology as regards to what the acronym RR corresponds. In p.12 Karlin [ 15] he uses the abbreviation `SR’ for “sign-regularity” and then `RR’ writing “where the letters represent an abbreviation of the sign-reversal rule”. From this it makes sense to translate `RR’ as “reverse-regular” (sign), and this is how Block et al. [ 6] use it, and so do Joag-Dev and Proschan [ 7], Nelsen [ 16], Drouet Mari and Kotz [ 10], and Balakrishnan and Lai [ 17]. But in Karlin and Rinott [ 2] the authors clearly state `RR’ to mean “reverse rule”, and other authors like Joe [ 13] follow this translation. p. 199 Nelsen [ 14] simply states both. |

| 7 |

These were the integral2 function from the package pracma in the R platform, and the online calculators of Wolfram Alpha and of dcode.fr. |

| 8 |

|

| 9 |

These results hold of course also for positive quadrant dependence with the obvious sign adjustment. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).