1. Introduction

Cancer remains a common cause of death worldwide, with a projected global economic cost of

$25.2 trillion in international dollars between the years 2020 and 2050 [

1]. Traditional treatments, such as chemotherapy, can cause debilitating side effects [

2]. Newer targeted and personalized treatments such as monoclonal antibodies [

3] and cell therapies [

4,

5] are having some success but are cost-prohibitive [

6,

7], and their effectiveness is limited to tumors that express certain target molecules [

3]. Therapies that are inexpensive, effective, and minimize off-target effects are crucial for the future of cancer treatment. One strategy to target cancer cells takes advantage of their weakness to induced oxidative stress at levels that are non-toxic to healthy tissues. For example, cancer cells are susceptible to the oxidative stress generated by ascorbic acid, a well-known antioxidant that can also produce large amounts of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the presence of catalytic metal ions [

8].

We observed a toxic effect on cancer cell lines from two small molecules in combination:

tert-butyl hydroquinone (tBHQ) and a manganese porphyrin, each best known for their antioxidant effect. tBHQ is a phenolic compound that is widely used as a food additive to mitigate fat oxidation [

9]. It is considered safe for use in this capacity by the FDA and the WHO [

10,

11,

12]. While studies have demonstrated that tBHQ can have toxic effects in cancer cells, inducing apoptosis and causing DNA damage [

13,

14], toxic concentrations are generally considered well above the physiological range attainable by oral dosing. For example, studies in animals show that while 80-90% of orally-dosed tBHQ is bioavailable, it is rapidly metabolized in the liver to the 4-

O-sulphate conjugate and the 4-

O-glucuronide conjugate [

9,

15,

16], greatly minimizing free tBHQ.

First developed as superoxide dismutase mimics, manganese porphyrins have been optimized for over three decades for bioavailability, minimized toxicity, and therapeutic efficacy, and myriad interactions with redox-sensitive pathways have been identified [

17]. They protect normal cells from the harmful effects of radiation therapy, while at the same time, sensitize cancer cells to the therapy [

18,

19]. They also tend to accumulate at higher concentrations in cancer cells, as opposed to healthy cells [

19], and these traits have made them promising therapeutic agents. The manganese porphyrin tested in this study, MnTnBuOE-2-PyP

5+ (MnBuOE), also called BMX-001, is currently being assessed in clinical trials as a radioprotectant of normal tissues during treatment for cancers ranging from head and neck to rectal. Its effectiveness is evident in a recently-completed Phase II glioma trial, in which BMX-001 was tested in combination with radiation and oral chemotherapy drug temozolomide, where the data showed that BMX-001 improved overall patient survival [

19,

20].

Herein, we present the effect of the combination of tBHQ and MnBuOE on cancer cells. We show that, while each antioxidant on its own is toxic only at relatively high doses, the combination of both drugs is toxic to cancer cells at physiologically achievable doses. We investigate the mechanism by which this cell death occurs and propose that the toxicity is caused by hydrogen peroxide generated by tert-butylquinone (tBQ), the electrophilic quinone produced by the manganese porphyrin-catalyzed oxidation of tBHQ. Additionally, we demonstrate the ability of this combination treatment to target cancer cells by showing its minimal toxicity in non-cancerous primary cells.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

Unless stated otherwise, all chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The compounds tBHQ (112941), tBQ (429074), and di-tert-butylhydroquinone (dtBHQ) (112976) were prepared daily in DMSO from powder to 50 mM. Both tBHQ and dtBHQ were prepared in fresh plastic tubes, and the ultrapurified water used in subsequent dilutions was stored in the same, to prevent trace metal contamination. MnBuOE, a gift from Dr. James Crapo, was dissolved in PBS to 4 mM, with aliquots stored in the dark at 4°C. Treatments contained 1 µM MnBuOE unless otherwise stated. Catalase (C1345) was prepared daily by dissolving in 50 mM phosphate followed by sterile filtration, and the final concentration was 2000 U/mL in treated wells.

2.2. UV-Vis Spectroscopy

Solutions of 25 µM tBHQ or dtBHQ in phosphate buffered saline pH 7.4 were prepared, and their UV-Vis spectra from 220 to 520 nm were measured on an Agilent Cary 60 UV-Vis spectrophotometer at room temperature (21°C). To observe oxidation of each to the quinone form, 30 µL of 0.1 mM MnBuOE was added to 3 mL final volume of the tBHQ or dtBHQ solutions, and spectra were collected every 30 to 60 s. To maintain solubility of the di-tert-butylquinone (dtBQ) product at 21°C upon its formation, reactions were set up under the same conditions but with 200 proof ethanol included at 50% final concentration. Data were fit to a one phase decay using GraphPad Prism.

2.3. Cell Culture

2.3.1. Suspension Cell Culture

The Jurkat clone E6-1 cell line (TIB-152, ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) was maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2 in RPMI-1640 containing phenol red (Cytiva, SH30096.01, Marlborough, MA, USA) and stabilized L-glutamine (L-alanyl-L-glutamine dipeptide) (bioWORLD, 44043001-1, Dublin, OH, USA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (R&D Bio-Techne, S1115014, Minneapolis, MN, USA) in T75 flasks. This complete media was stored at 4°C, with aliquots warmed to 37°C just prior to use. Cell cultures were passaged every two to four days and were strictly maintained at cell densities between 1 × 105 and 1.5 × 106 cells/mL during propagation.

2.3.2. Adherent Cell Culture

The PC3 cell line (CRL-1435, ATCC) and the MDA-MB-231 (HTB-26, ATCC) cell line were grown in complete media in T75 flasks. Media for these lines was RPMI and Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) respectively, both supplemented with 10% FBS. For experiments comparing PC3 cells to mouse prostate fibroblast (MPF) cells, 1% penicillin/streptomycin was also included in the cell culture media. Cells were passaged when they had reached 70-85% confluency.

2.3.3. Mouse Primary Prostate Fibroblast Isolation and Cell Culture

Male C57BL/6J mice obtained from Jackson Laboratories were used in this study [

21]. The mice were housed at the University of Nebraska Medical Center (UNMC) and exposed to a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle and fed and watered ad libitum. This study was carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. All procedures were approved by the institutional animal care and use committee at UNMC (20-019-03-FC).

Mouse primary fibroblasts were isolated as previously described [

21]. Briefly, prostates were isolated from 6-8 week old C57BL/6J mice. Tissue was minced with a scalpel then digested in 5 mg/mL collagenase I (ThermoFisher, 17100017, Waltham, MA, USA) for 30 min at 37 °C. Cells and tissue fragments were then cultured for 2–3 weeks in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin and 1% nonessential amino acids. Cultures were maintained at 5% CO

2 and 37°C. After 5 days of culture, only fibroblasts were present.

2.4. Toxicity Assays

2.4.1. Cell Treatments

Cells were treated for 24 h with tBHQ, dtBHQ, dtBQ, MnBuOE, and/or catalase, as indicated in the figures. The final volume in all wells was 105 µL, and the final DMSO concentration in media was 0.05%. When designing plate layouts for experiments, care was taken to minimize any neighboring well effect of the treatments, as previously reported for tBHQ [

22]. Thus, titrations of tBHQ, dtBHQ, or tBQ were set up from lowest to highest concentration across a plate.

2.4.2. CellTiter-Glo® Assay

Toxicities of tBHQ, dtBHQ, and MnBuOE in PC3 and Jurkat cells were determined using a CellTiter-Glo® assay, which measures ATP levels and defines a living cell as a metabolically active one. After treatment, cells were washed with PBS, followed by addition of 25 µL of PBS and 25 µL of CellTiter-Glo 2.0 (CTGlo) (Promega, G9241, Madison, WI, USA), and incubation in the dark at room temperature for 10 min. Luminescence was measured using a ClarioStar Plus plate reader (BMG Labtech, Ortenberg, Germany).

2.4.3. CellTiter-Fluor™ Assay

Toxicities of tBHQ, tBQ, and MnBuOE in Jurkat cells were determined using a CellTiter-Fluor™ assay, which assesses viable cells by measuring protease activity. After treatment, cells were washed with PBS, followed by resuspension in 25 µL Hank’s Buffered Salt Solution (HBSS) (Cytiva, SH30268.01). Upon addition of 25 µL of CellTiter-Fluor (CTF) (Promega, G6080), samples were incubated in the dark at 37°C for 1 h. Fluorescence was measured using the ClarioStar Plus plate reader with excitation and emission of 390/505 nm.

2.4.4. Bicinchoninic Acid (BCA) Assay

Toxicities of tBHQ, tBQ, and MnBuOE in MDA-MB-231 cells were determined using a BCA assay, which, after washing adhered cells to remove lysed cells and their concentration, measures remaining living cells by total protein content. After treatment, cells were washed twice with PBS, followed by addition of 25 µL lysis buffer consisting of 0.03% Triton X-100 (X100RS). After incubation on a plate shaker for 10 min, 200 µL of BCA reagent (Thermo Fisher, 23225) was added, and the plate was shaken for 3 min. The plate was incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Absorbance was measured at 562 nm on the ClarioStar Plus plate reader.

2.4.5. Data Analysis to Determine the Concentration Lethal to 50% of the Cells (LC50)

Readings from each assay were either normalized to the untreated control or to the lowest concentration of the treated control, as described in the figure legends. Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism, and the LC50 values were determined using a variable-slope four-parameter fit. The data were analyzed without constraining the parameters, except for tBHQ+MnBuOE in

Figure 1C (top constrained to 100) and the data in

Figure 1E (bottom constrained to 0).

2.4.6. Trypan Blue Exclusion Assay

A Trypan blue exclusion assay was used to compared the toxicity of tBHQ and MnBuOE in PC3 versus MPF cells. After treatment, cells were trypsinized and pelleted, then resuspended in 200 µM of cell culture media. Cells were counted and viability was measured using a Vi-CELL BLU cell viability analyzer (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA).

2.5. Flow Cytometry Assays

2.5.1. Cell Treatment

PC3 cells in a 24-well plate at ~80% confluency were treated in 500 µL of media with 20 µM tBHQ or dtBHQ and with 1 µM MnBuOE where indicated. Jurkat cells (1 x106 cells/mL in 150 µL) in a 96-well plate were treated with 10 µM tBHQ or dtBHQ and with 1 µM MnBuOE where indicated.

After 4 h in a 37°C CO2 incubator, PC3 cells were trypsinized to remove them from the plate, and Jurkat cells were removed directly from the plate for the apoptosis and necrosis assay. Following completion of this assay, after 6 h total of treatment time, additional wells were used to harvest PC3 cells and Jurkat cells for the MitoSOX assay.

2.5.2. Apoptosis & Necrosis Assay

Apoptosis and necrosis were assayed by flow cytometry using Annexin-PE (Biotium, 29045, Fremont, CA, USA) to measure apoptosis and RedDot 2 dye (Biotium, 40061-T) to measure necrosis, according to manufacturer instructions. A sample (nominally comprising 1x105 cells) was centrifuged and washed with 100 µL of 1x Annexin binding buffer (10 mM HEPES, 140 mM NaCl, and 2.5 mM CaCl2, pH 7.4). Cells were resuspended in 20 µL of this buffer with 1 µL of Annexin and 0.05 µL of RedDot added and incubated at room temperature in the dark for 10 min. An additional 80 µL of Annexin binding buffer was added, and the cells were incubated for an additional 10 min covered from the light. Fluorescence was measured using an Accuri C6 Plus flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ). A 488-nm laser was used to excite the dyes, and emitted fluorescence was measured using the FL2 (585/40 nm) and FL4 (675/25 nm) filters for Annexin and RedDot, respectively. A total of 10,000 events were collected for each sample. The data were analyzed using FlowJo version 10.10.0.

2.5.3. Mitochondrial Superoxide Assay

MitoSOX Red, which is targeted to the mitochondria and fluoresces when oxidized by superoxide, was used to measure mitochondrial oxidative stress according to manufacturer instructions. A sample (nominally comprising 1x105 cells) was centrifuged and washed twice with 100 µL of 1x Annexin binding buffer. Cells were then resuspended in 100 µL Annexin binding buffer containing 1 µM MitoSOX Red (Invitrogen, M36008, Waltham, MA). The cells were covered from the light and incubated for 10 min at room temperature, then centrifuged and resuspended in 100 µL binding buffer. The cells were incubated for another 10 min covered from light, and then fluorescence was measured using an Accuri C6 Plus flow cytometer. A 488-nm laser was used to excite the dyes, and emitted fluorescence was measured using the FL2 filter. Unless otherwise noted, a total of 10,000 events were collected for each sample. The data were analyzed using FlowJo version 10.10.0.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism. For the MitoSOX experiments and the CTGlo experiments that compared single concentrations of various additives and were presented in bar graph format, a one-way ANOVA test was used, followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test to compare each condition to the vehicle control. For the apoptosis/necrosis flow cytometry results, a two-way ANOVA test was used, followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test to compare each condition to the vehicle control. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

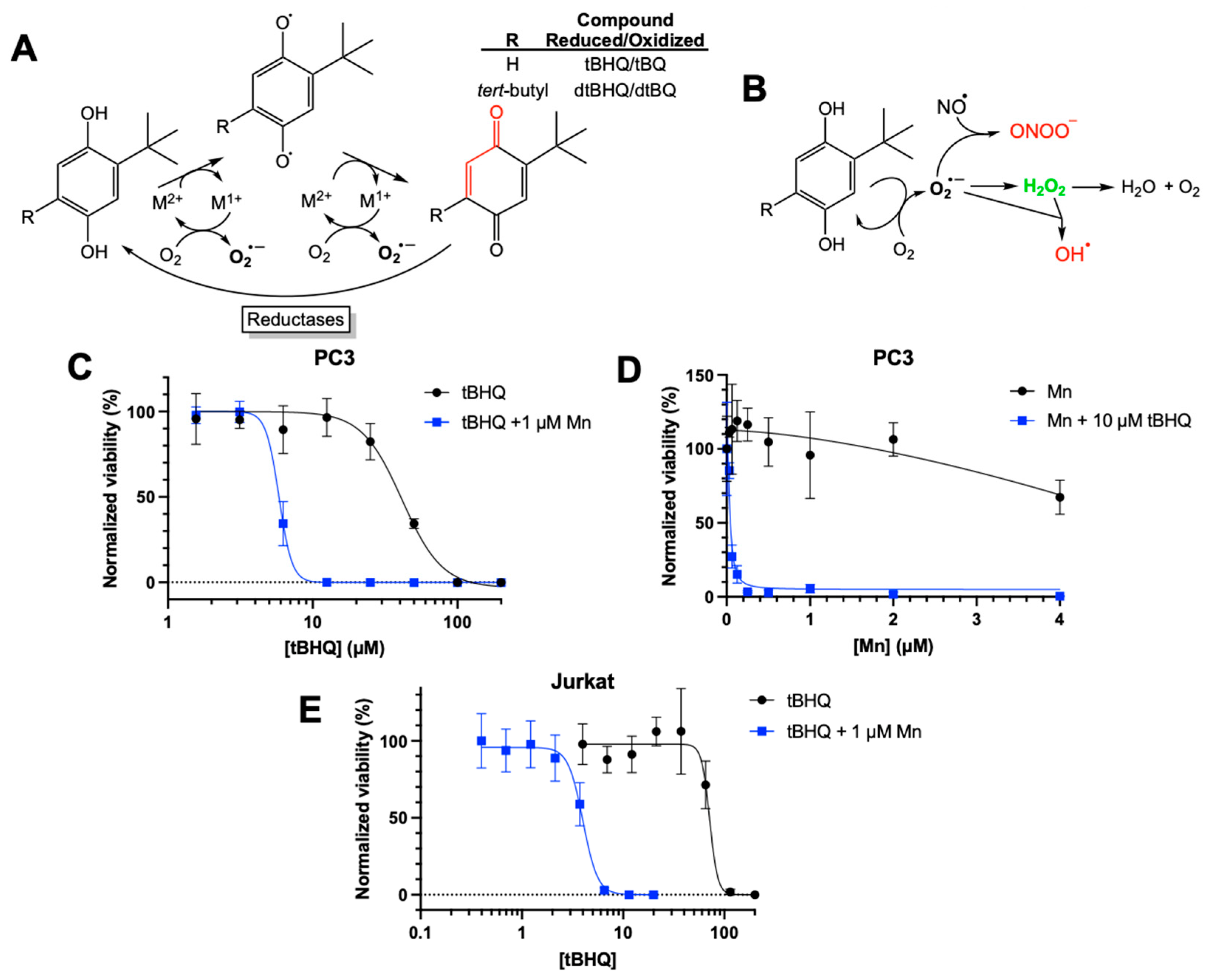

3.1. The Combination of tBHQ and MnBuOE Is More Toxic than Either Component Alone

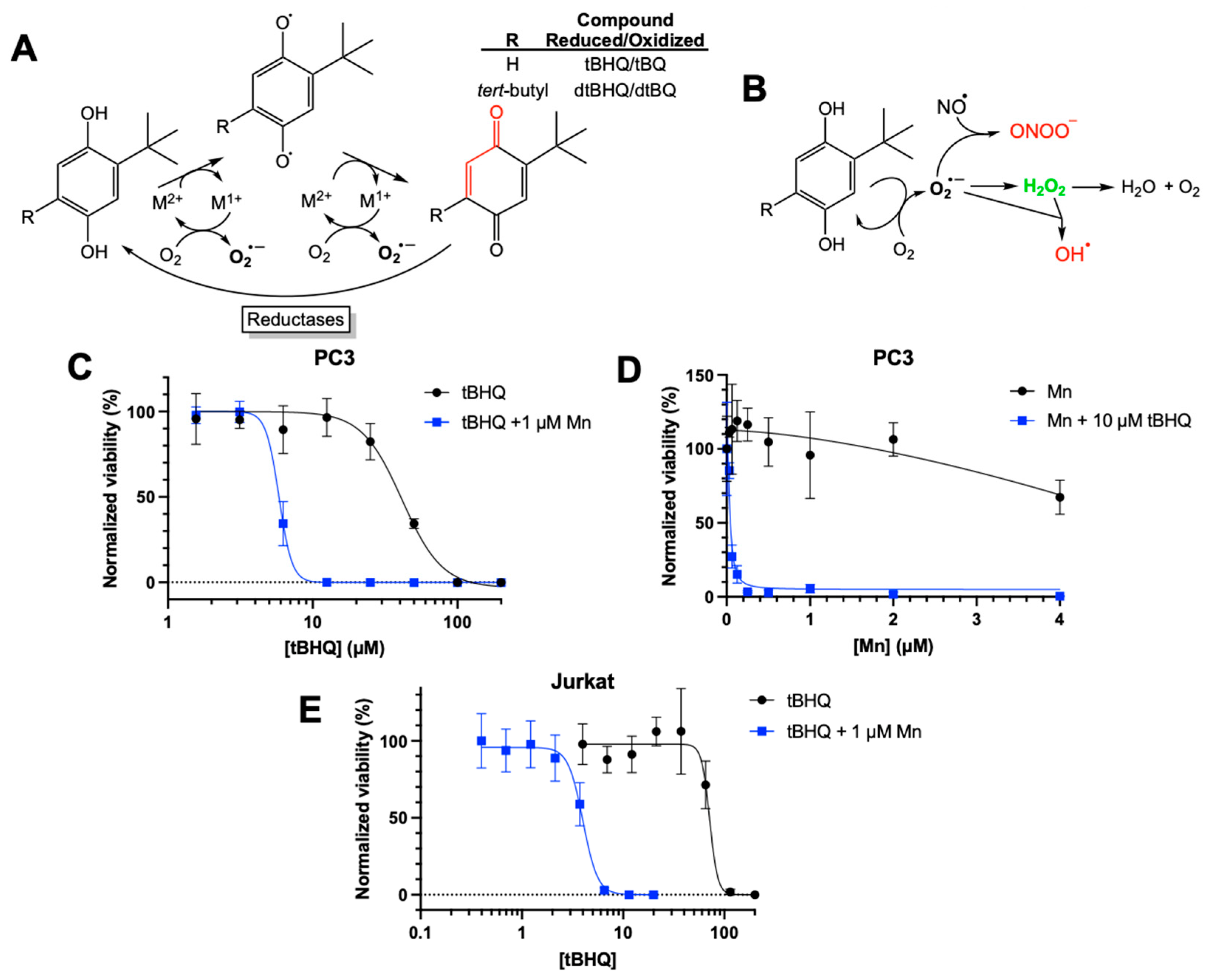

While previously investigating the toxicity of tBHQ as a redox-cycling compound (

Figure 1A), we attempted to mitigate this toxicity to immortalized cell lines by including a commercially available superoxide dismutase mimetic—manganese (III) tetrakis(1-methyl-4-pyridyl)porphyrin pentachloride (MnTMPyP). As shown in

Figure 1A, hydroquinones such as tBHQ and dtBHQ are readily oxidized in a catalytic manner by transition metals to first the semiquinone and then the quinone, generating superoxide. Toxicity from redox cycling is generally attributed to reactive oxygen and nitrogen species formed downstream of superoxide (

Figure 1B). Superoxide dismutase and its small molecule mimetics act as antioxidants by catalyzing the conversion of superoxide to hydrogen peroxide, limiting generation of strong oxidizing molecules such as the hydroxyl radical and peroxynitrite. MnTMPyP was highly effective at rescuing dtBHQ-induced suppression of global protein synthesis in the immortalized HaCaT keratinocyte cell line [

23], and we expected the same for tBHQ-induced effects when treating with MnTMPyP. Instead, we observed that MnTMPyP greatly sensitized HaCaT cells and cancer cell lines to tBHQ, significantly decreasing tBHQ LC50 values (

Figure S1). To determine whether this observation might be translatable to a therapeutically relevant manganese porphyrin in clinical trials, the combination of MnBuOE and tBHQ was investigated in cancer cell lines. As shown in

Figure 1C, in PC3 cells, an adherent prostate cancer cell line, tBHQ had an LC50 value of 41 ± 3 µM. MnBuOE alone also showed low toxicity at concentrations of 2 µM or less (

Figure 1D). However, the combination of tBHQ with 1 µM MnBuOE resulted in an LC50 of 6 ± 0.5 µM, a 6 to 7-fold increase in the potency of tBHQ. Thus, the combination of tBHQ and MnBuOE was far more toxic to PC3 cells than either component by itself. A titration of MnBuOE with 10 µM tBHQ showed that 0.25 µM MnBuOE was sufficient for the toxic effect (

Figure 1D), which is far less than the amount of MnBuOE (2-6 µM) that has been shown to accumulate in the liver, kidney and lymph nodes [

24].

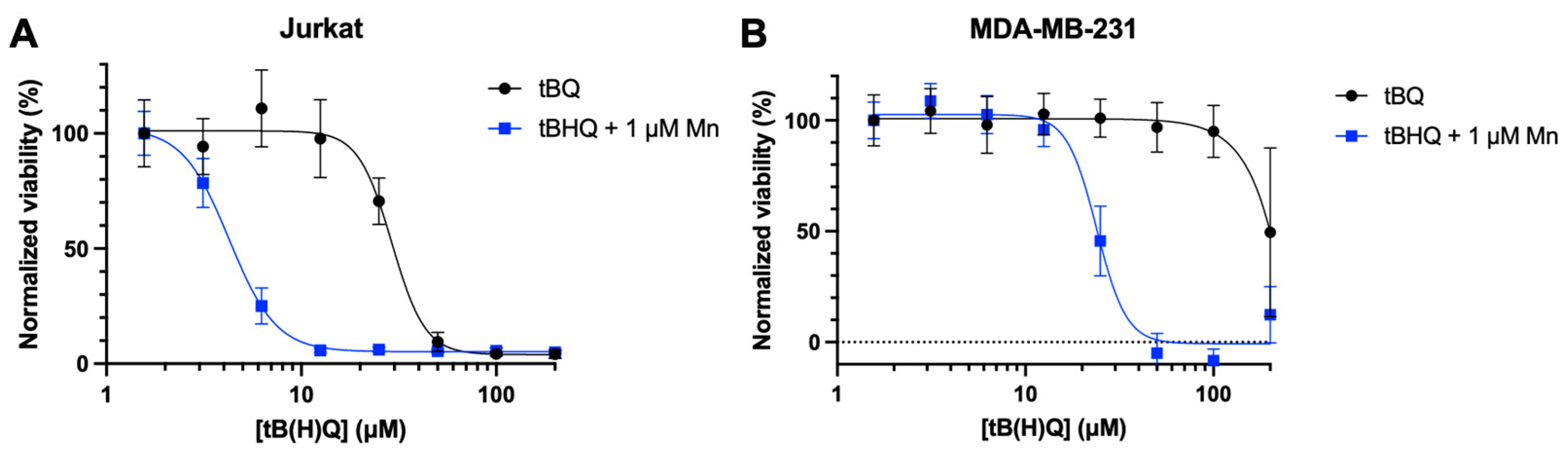

To determine if this phenomenon applied to other cancer cell lines, we tested the combination in Jurkat cells, a suspension leukemia cell line. As with PC3 cells, tBHQ alone was fairly non-toxic to Jurkat cells, with an LC50 value of 72 ± 10 µM (

Figure 1E). Inclusion of MnBuOE decreased the LC50 approximately 18-fold to 4 ± 0.2 µM. Additionally, testing the combination treatment in the adherent breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-231 showed similar results, reducing the LC50 by approximately 10-fold (

Figure S2).

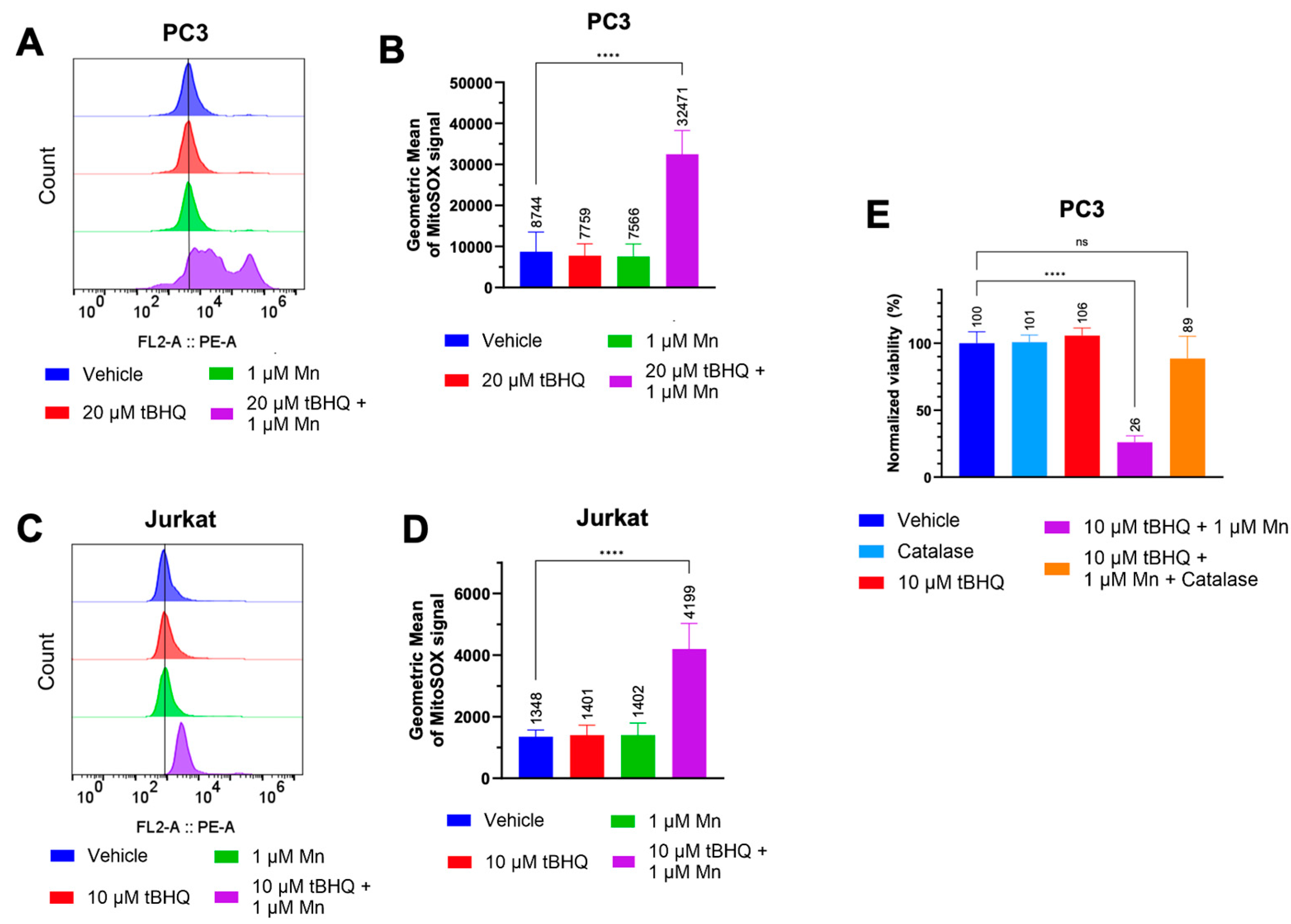

3.2. Hydrogen Peroxide Is a Major Contributor to the Toxicity of the tBHQ-MnBuOE Treatment

We hypothesized that the toxicity of the tBHQ-MnBuOE combination was caused by oxidation of tBHQ catalyzed by the manganese ion in MnBuOE (

Figure 1A). We examined the extent to which the tBHQ-MnBuOE combination induced oxidative stress in PC3 and Jurkat cells. Because MnBuOE can localize to the mitochondria [

19], mitochondrial superoxide levels were measured using MitoSOX Red dye. In PC3 cells, neither 20 µM tBHQ nor 1 µM MnBuOE alone caused oxidative stress compared to cells treated with vehicle (

Figure 2A,B). The combination of tBHQ and MnBuOE increased the MitoSOX signal intensity by approximately four-fold compared to the vehicle, shown by an increase in the geometric mean (

Figure 2A,B). Jurkat cells showed similar results, with an approximately three-fold signal increase in cells treated with tBHQ and MnBuOE compared to vehicle (

Figure 2C,D).

As hydrogen peroxide is generally considered to be a major contributor to cell stress caused by two-electron redox cycling (

Figure 1A), catalase was included at the time of treatment of PC3 cells with 10 µM tBHQ and MnBuOE. Catalase converts hydrogen peroxide into harmless water and oxygen. Although catalase does not enter the cell, it reduces intracellular hydrogen peroxide levels due to the ability of hydrogen peroxide to cross cellular membranes [

25,

26]. Addition of catalase improved cell viability from ~25% to ~90% in cells treated with the tBHQ-MnBuOE combination (

Figure 2E). Thus, hydrogen peroxide is a major factor in the mechanism of cell death caused by the tBHQ-MnBuOE combination.

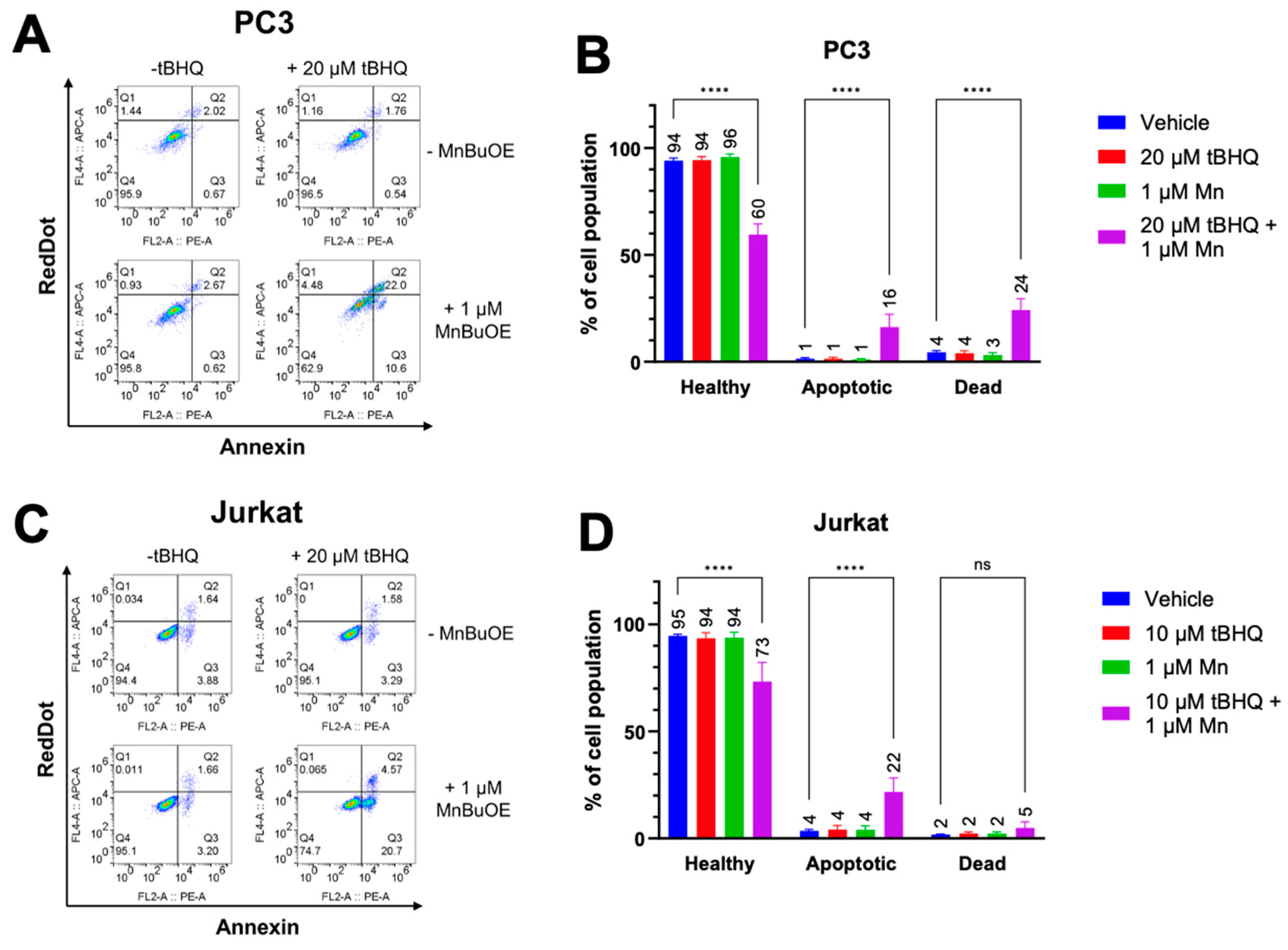

3.3. The Combination of tBHQ and MnBuOE Causes Apoptotic Cell Death

Since oxidative stress has been linked to apoptotic cell death [

27], early apoptosis was measured in PC3 and Jurkat cells treated with tBHQ and MnBuOE using an Annexin V assay. As expected, each component alone did not cause an increase in apoptosis or necrosis (

Figure 3A,B). However, PC3 cells treated with a combination of 20 µM tBHQ and MnBuOE showed an increase in apoptotic cell death of approximately 15% compared to cells treated only with vehicle. Necrotic cell death also increased to approximately 20%, indicating that there is some other mechanism of cell death occurring as well. Jurkat cells treated with tBHQ and MnBuOE also showed an increase in apoptotic cell death of nearly 20%, but no significant increase in necrotic cell death (

Figure 3C,D), indicating that oxidative stress was the most likely cause of cell death.

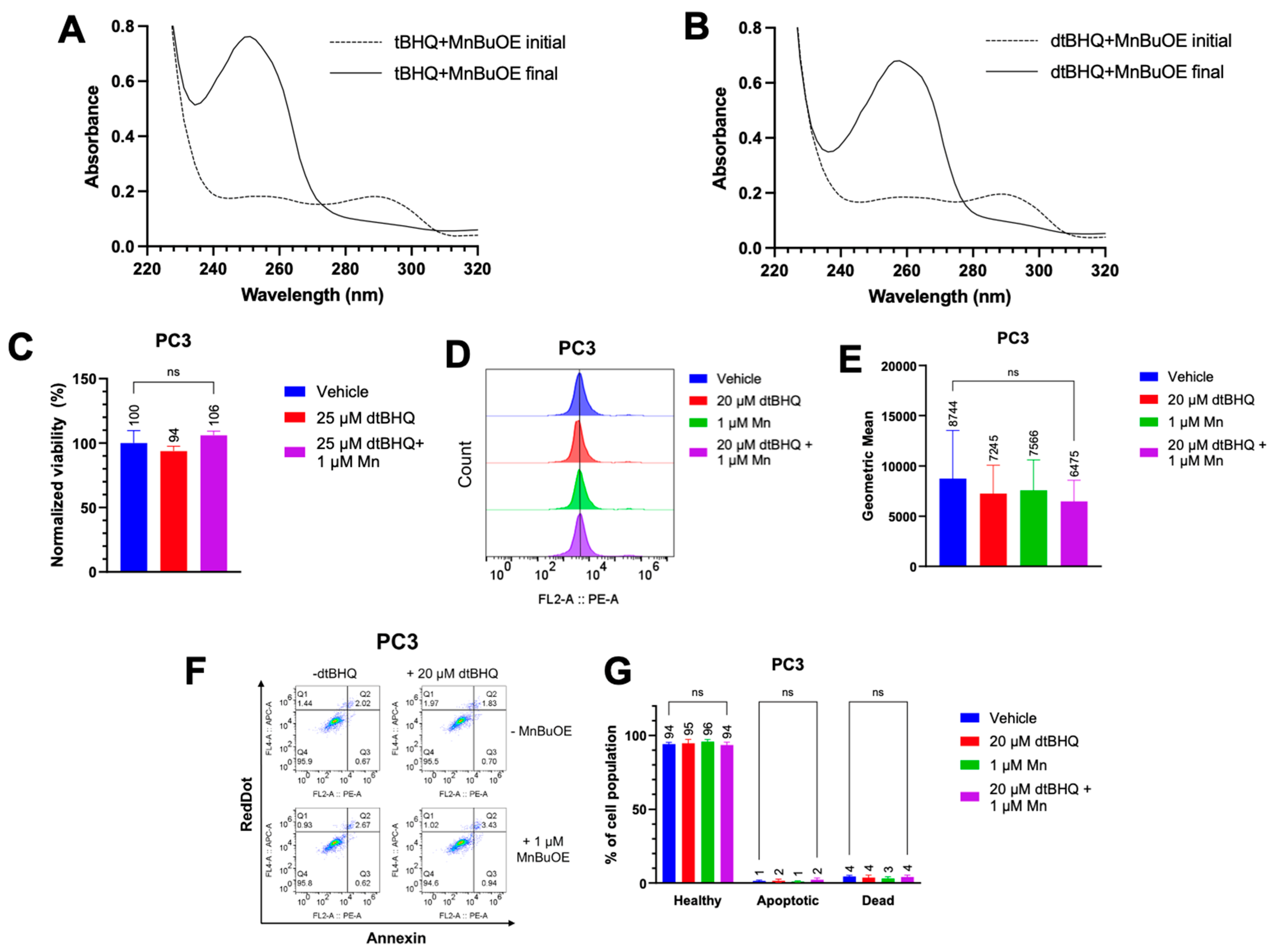

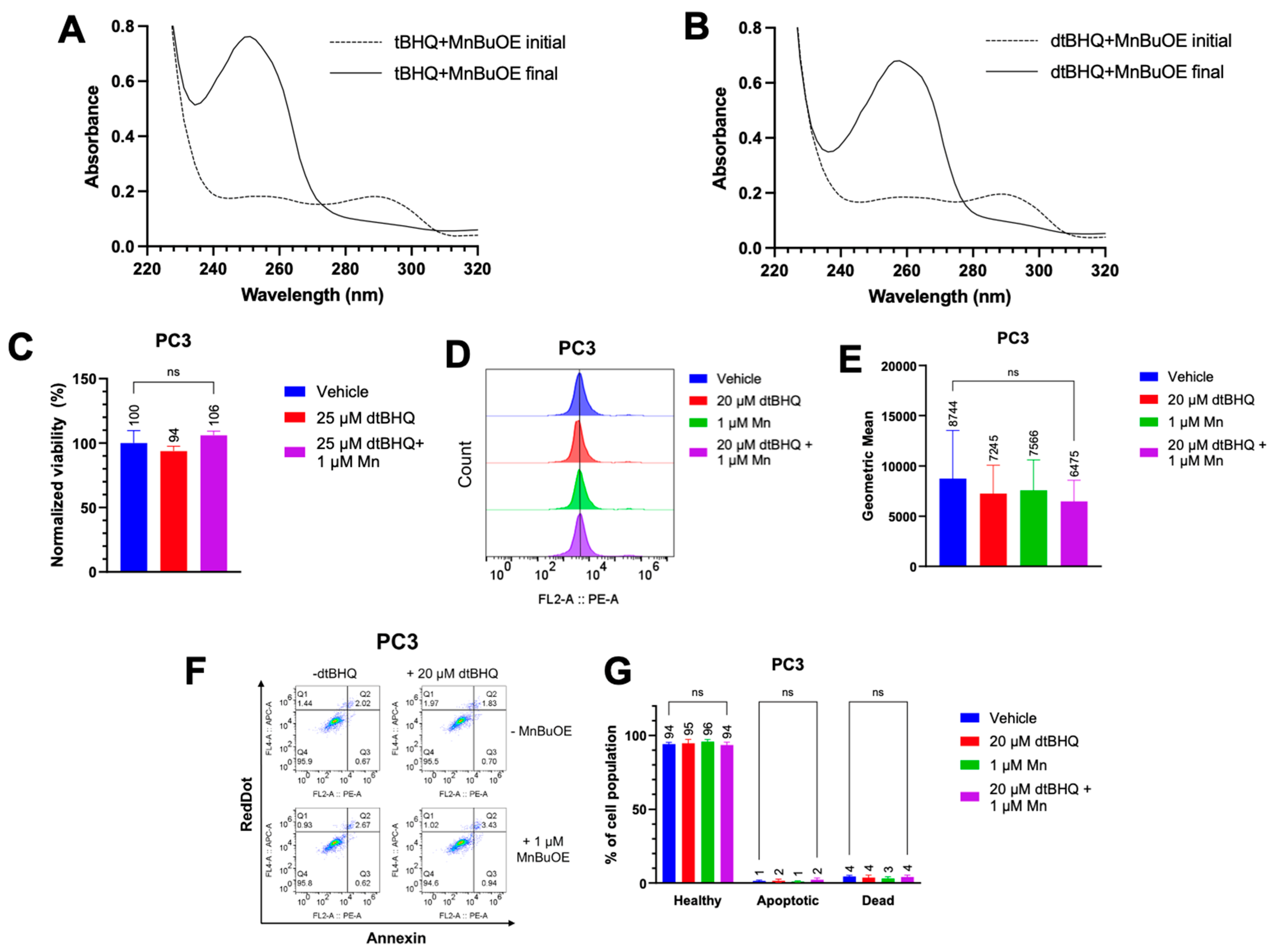

3.4. Cell Death Is Related to the Catalyzed Oxidation of tBHQ into an Electrophilic Quinone

We now had evidence that the hydrogen peroxide was a major contributor to cell death by the tBHQ-MnBuOE treatment. To investigate the extent to which hydroquinone redox-cycling or perhaps the electrophilic nature of tBQ were responsible for generating hydrogen peroxide at toxic levels, dtBHQ was tested in combination with MnBuOE. dtBHQ is a useful analog of tBHQ, with an additional

tert-butyl group (

Figure 1A) that blocks addition of nucleophiles to the quinone produced upon oxidation, dtBQ [

28,

29]. dtBHQ is readily oxidized to dtBQ in the presence of transition metals.

We first determined whether MnBuOE was able to oxidize both tBHQ and dtBHQ to their quinone forms, using UV-Vis spectroscopy. Both tBHQ and dtBHQ at 25 µM readily oxidized upon addition of MnBuOE (

Figure S4A, B). However, as dtBQ accumulated, its lower water solubility than tBQ, together with a room temperature of 21°C, caused precipitation, shown by an increase in light scattering at 500 nm (

Figure S4B), complicating comparison of tBHQ and dtBHQ oxidation rates. Conducting both reactions in 50% ethanol to solubilize the dtBQ at room temperature, the kinetics of oxidation for tBHQ and dtBHQ were assessed, with similar

kobs for each (the oxidation of tBHQ is two times faster than that of dtBHQ) (

Figure S4C–F). The first and last timepoint spectra for tBHQ and dtBHQ with MnBuOE are shown in

Figure 4A and

Figure 4B, respectively. These results suggest that MnBuOE will readily catalyze the oxidation of both compounds in the cellular environment, and thus that hydrogen peroxide from redox cycling will be generated when either tBHQ or dtBHQ is present in combination with MnBuOE.

To test whether redox cycling-generated hydrogen peroxide was responsible for the toxicity to cancer cells, PC3 cells were treated with MnBuOE and dtBHQ at a concentration (25 µM) that was highly toxic in parallel experiments with tBHQ in the combination treatment (

Figure 1C). Either with dtBHQ alone or in combination with MnBuOE, there was no statistically-significant decrease in cell viability (

Figure 4C). Likewise, treating PC3 cells with 20 µM dtBHQ and 1 µM MnBuOE alone or in combination resulted in no increase in mitochondrial superoxide, apoptosis, or necrosis (

Figure 4D–G). Similar results were seen in Jurkat cells treated with 10 µM dtBHQ and 1 µM MnBuOE (

Figure S3). Therefore, two-electron redox cycling by dtBHQ generates insufficient hydrogen peroxide to induce cell death. By extension, redox cycling by tBHQ is likely insufficient to cause cell death. Instead, as for other arylating quinones [

30], the cell death that occurs when cells are treated with tBHQ and MnBuOE is likely caused by the electrophilic quinone, tBQ (

Figure 1A, with the electrophilic moiety denoted in red).

3.5. tBQ Alone Is Less Potent in Cancer Cells than the Combination of tBHQ and MnBuOE

To investigate whether the toxicity of the tBHQ-MnBuOE combination was caused by the electrophilic quinone tBQ, Jurkat and MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with tBQ, or the tBHQ-MnBuOE combination treatment (

Figure 5A,B). In both cell lines, tBQ alone was much less toxic than the combination treatment, with an LC50 of 29.1 ± 2 µM for Jurkat cells and >200 µM for MDA-MB-231 cells. The combination of tBHQ and MnBuOE was far more potent, with LC50 values of 4.3 ± 0.2 µM and 23.9 ± 1 µM for Jurkat and MDA-MB-231 cells, respectively. The data suggest that the combination of tBHQ and MnBuOE would likely make a more effective therapeutic than administering tBQ.

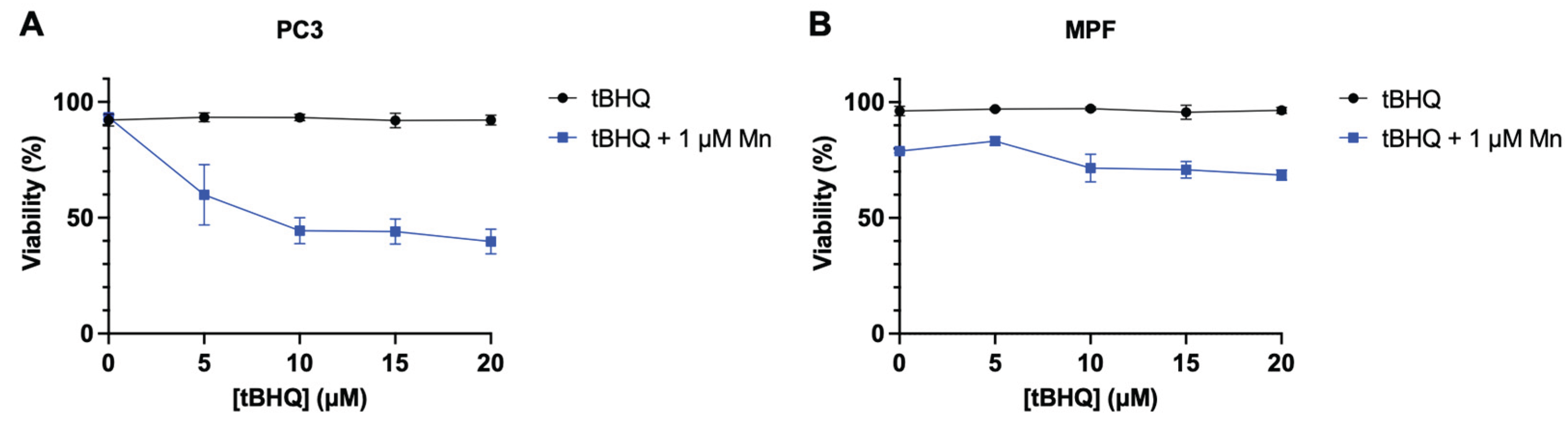

3.6. The Selectivity of the Toxicity of the tBHQ-MnBuOE Treatment to Cancer Cell Lines

While the combination of tBHQ and MnBuOE generates levels of oxidative stress that are toxic to the tested cancer lines, primary cells from healthy tissue are typically less sensitive to induced oxidative stress. To test whether primary cells might be less affected by the treatment, tBHQ and MnBuOE were tested in non-cancerous mouse prostate fibroblasts (MPF) and compared to PC3 cells. PC3 cells were sensitive to the tBHQ-MnBuOE treatment as expected, with viability dropping by half at 10 µM tBHQ with MnBuOE present (

Figure 6B). MPF cells, on the other hand, were slightly sensitive to 1 μM MnBuOE alone, with 80% viability, but adding tBHQ with MnBuOE did not further decrease viability, up to 20 µM tBHQ (

Figure 6B). This finding that cancer cell lines are more sensitive to tBHQ and MnBuOE than MPF supports a potential therapeutic usage for this combination of antioxidants.

4. Discussion

4.1. tBQ as the Causative Agent of Oxidative Stress and Cytotoxicity

The electrophilic nature of tBQ appears to be largely responsible for the toxic levels of hydrogen peroxide by the tBHQ-MnBuOE treatment, given the lack of toxicity when treating with dtBHQ-MnBuOE instead. This is consistent with the general understanding that arylating (electrophilic) quinones like tBQ are much more toxic than non-arylating quinones that are sterically blocked from acting as electrophiles [

30].

Although the dtBHQ experiments suggest tBQ is the agent responsible for oxidative stress and toxicity, tBQ alone was far less potent than the tBHQ-MnBuOE combination. Prior to entering the cell, electrophilic tBQ can react with nucleophiles in the cell culture media, such as cysteines in bovine serum album, during the treatment incubation [

31]. Of particular relevance to

in vivo studies, tBQ would likely react with glutathione in the cytoplasm prior to reaching the ER or the mitochondria [

32]. The combination of tBHQ with a manganese porphyrin in therapies may allow for more targeted delivery of tBQ to the tumor environment, and specifically to sensitive organelles such as the ER in cancer cells.

4.2. How might tBQ be generating hydrogen peroxide through its electrophilic functionality?

The two major sources of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the cell are the mitochondria and the endoplasmic reticulum. While the electron transport chain is a well-known source of superoxide, disulfide bond formation in the ER also uses molecular oxygen as the terminal electron acceptor, leading to superoxide formation [

33]. tBQ is an arylating quinone, a soft electrophile that reacts with the soft nucleophilic cysteine residue in proteins and glutathione. A seminal study by Wang

et al. in 2006 demonstrated that arylating quinones form Michael adducts with protein thiols in the endoplasmic reticulum, disrupting disulfide bonds essential for proper protein folding, and triggering the unfolded protein response (UPR) through activation of the protein kinase RNA-like ER kinase (PERK) signaling pathway [

30]. In contrast, non-arylating quinones, which lack this electrophilic reactivity, induced significantly less ER stress and toxicity. This result is consistent with our observations that tBHQ, but not dtBHQ, is toxic in combination with MnBuOE. There is a complex interplay between ER stress and oxidative stress, recently reviewed in [

34], but it is clear that ER stress alone is sufficient to generate ROS, shown for example, in cells treated with tunicamycin, which disrupts protein folding by blocking N-linked glycosylation [

35]. Very recently, Tao

et al. reported that PERK disrupts ER–mitochondria communication at mitochondria-associated membranes (MAMs), impairing calcium and lipid exchange and destabilizing mitochondrial homeostasis, leading accumulation of mitochondrial ROS [

36]. Numerous studies show mitochondrial oxidative stress generation by electrophiles. For example, the electrophile sulforaphane generates mitochondrial oxidative stress that is responsible for cancer cell death [

37,

38].

The mechanisms of toxicity of tBQ administered to cultured cells in media have been investigated [

32], and in this context, ER stress was not observed. Rather, cellular glutathione levels were depleted, which could generate oxidative stress. However, it seems that under these conditions, many other cellular thiols would also be modified, leading to general toxicity that would be unlikely to be rescued by catalase so effectively as was the tBHQ-MnBuOE treatment-induced toxicity in our study. Collectively, these observations suggest that glutathione depletion is not the source of toxic levels of hydrogen peroxide from the combination treatment, though this remains to be tested, in particular since the combination treatment may generate tBQ intracellularly, as opposed to extracellular tBQ addition.

Quinones such as tBQ are well-known to generate toxic levels of hydrogen peroxide in the cell by one-electron redox cycling [

39,

40]. Quinones are readily reduced by one electron by cytochrome P450 enzymes to unstable semiquinone radical anions, with the electron then being readily donated back to molecular oxygen to generate superoxide and subsequently, hydrogen peroxide. A major role as an antioxidant enzyme has been identified for NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase (NQO1) to prevent one-electron redox cycling by rapidly reducing quinones back to the hydroquinone (

Figure 1A) [

41]. Aldo-keto reductase family 1 member B1 (AKR1B1) can reduce tBQ to tBHQ [

42]. Both enzymes are widely expressed in various tissues and organs, primarily in the cytoplasm. Reduction of tBQ in the cytoplasm by a relevant reductase may be one reason why tBQ is so much less toxic as a cellular treatment than the tBHQ-MnBuOE combination, which may be able to generate tBQ within particularly vulnerable cellular compartments such as the endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria.

Given that the dtBHQ-MnBuOE combination treatment is non-toxic, it seems unlikely that toxic levels of hydrogen peroxide are generated by either one-electron or two-electron redox cycling of tBHQ, apart from the electrophilic character of tBQ. dtBHQ is easily oxidized to dtBQ when catalyzed by MnBuOE, and yet the generated dtBQ does not induce detectable mROS or cytotoxicity. For tBQ and dtBQ generated intracellularly to both undergo one-electron redox cycling, they would be reduced by cytochrome P450s, which seems likely given the high structural diversity among quinones able to generate oxidative stress in this manner [

40]. Similarly, for tBQ and dtBQ to both undergo two-electron redox cycling, they would be reduced by cellular reductases such as NQO1, which also seems likely given the structural diversity in the many known substrates of the enzyme [

43]. The ability of NQO1 and cytochrome P450s to act on tBQ and dtBQ as substrates remains to be determined.

4.3. Role of the Manganese Porphyrin in Toxicity of the Combination Treatment to Cancer Cells

Intravenous administration of decagrams of ascorbate alone has shown significant promise in clinical trials [

44,

45], due the ability of ascorbate to redox cycle and generate levels of hydrogen peroxide that are toxic to cancer cells. There are sufficient free transition metal levels in the cell to catalyze oxidation and thus redox cycling of ascorbate. The inclusion of manganese porphyrins can significantly increase the toxicity of hydrogen peroxide generated by ascorbate toward cancer cells ([

46,

47], reviewed in [

19]). Not only does MnBuOE catalyze redox cycling of ascorbate, producing more hydrogen peroxide, but at high enough ascorbate levels, sufficient hydrogen peroxide is generated to switch MnBuOE to an “oxidative” function. As largely discovered by the Tome lab, sufficient concentrations of hydrogen peroxide oxidize manganese porphyrins from the +5 to the +3 state, which then catalyzes the oxidation of protein thiols inducing

S-glutathionylation, causing massive changes to signaling and function in the cell, as well as overall oxidation of the glutathione pool. Healthy cells, by comparison, have sufficient antioxidant enzyme capacity, induced largely by the Nrf2 transcription factor in response to oxidative stress, to keep hydrogen peroxide levels below the threshold that can oxidize manganese porphyrins to the +3 state. This capacity of normal cells explains why a combination treatment of a manganese porphyrin with a hydrogen peroxide-generating molecule shows selective toxicity to cancer cells. Importantly, the toxicity of an ascorbate-manganese porphyrin combination was completely dependent on hydrogen peroxide in breast cancer cell lines SUM149 [

46] and MDA-MB-231 [

47], shown by the inclusion of catalase in the media, as was the toxicity of the tBHQ-MnBuOE combination in this study. Thus, it seems likely that the tBHQ-MnBuOE combination generates sufficient hydrogen peroxide to oxidize MnBuOE to the +3 state, causing both depletion of GSH and massive

S-glutathionylation, leading to apoptotic cell death.

The concentration of tBHQ needed in combination with a manganese porphyrin to kill cancer cells is much lower than the concentration of ascorbate required for a similar effect. This difference in LC50 likely arises because ascorbate generates hydrogen peroxide through redox cycling, whereas tBHQ produces hydrogen peroxide via a different mechanism—likely ER stress—through its electrophilic quinone form, tBQ.

Supporting this hypothesis, 50 µM dtBHQ in HaCaT cells suppressed global protein synthesis but did not generate enough hydrogen peroxide to activate the “oxidant” function of MnTMPyP [

48]. Instead, MnTMPyP rescued cells from protein synthesis inhibition by acting as a superoxide dismutase mimetic. In contrast, as observed in PC3 and Jurkat cells in this work, adding MnTMPyP to HaCaT cells treated with tBHQ increased toxicity. Because dtBHQ induces oxidative stress sufficient to inhibit protein synthesis, yet MnTMPyP reverses this effect rather than causing toxicity, it suggests that dtBHQ-driven redox cycling produces hydrogen peroxide at levels too low to oxidize manganese porphyrin to the +3 state. These findings support the idea that the electrophilic activity of tBQ is critical for generating high hydrogen peroxide levels in cancer cells, which then trigger the “oxidant” function of manganese porphyrins—oxidation to the +3 state—leading to GSH depletion and extensive protein S-glutathionylation. This phenomenon may occur because dtBHQ generates less hydrogen peroxide through redox cycling compared to tBQ, allowing manganese porphyrin to maintain its antioxidant role. Indeed, 50 µM dtBHQ did not alter the [GSH]:[GSSG] ratio in HaCaT cells [

23], even though global protein synthesis was suppressed at that concentration [

48].

4.3. Therapeutic Potential of a tBHQ-Manganese Porphyrin Combination

The apparent selectivity of the tBHQ-MnBuOE combination for cancer cells, LC50 values that are likely achievable physiologically, and the use of tBHQ as a common food preservative and MnBuOE in clinical trials as a radioprotectant together make this finding an exciting possible avenue for cancer treatment. An important next step prior to animal studies is to test an array of primary cells from healthy tissue for possible susceptibility. In addition, other manganese porphyrins in clinical development display varying degrees of targeting to the tumor environment and cellular organelles such as the mitochondria [

17]. These capabilities may enhance selective production of tBQ from tBHQ in vulnerable cellular compartments in cancer cells, widening the therapeutic window of a combination therapy.

5. Conclusions

The electrophilic nature of tBQ plays an essential role in generating levels of hydrogen peroxide in the tBHQ-MnBuOE combination treatment that are toxic to cancer cells. According to current knowledge in the field, ER stress is a likely means by which the generated tBQ produces hydrogen peroxide in these cells, potentially both from the ER itself and from mitochondria. The amount of hydrogen peroxide produced is likely sufficient to interact with the manganese porphyrin to cause hyper glutathionylation of cellular targets, a well-described mechanism for toxicity caused by manganese porphyrins in combination with hydrogen peroxide.

6. Patents

Eggler, A.L.; Tamarin, S.; Biesterveld, L.; LaMorte, J. Pharmaceutical composition comprising oxidizable biphenol and manganese porphyrin, and method of using the same. U.S. Patent No. 12201649. 2025. U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

https://www.mdpi.com/article/doi/s1, Figure S1: The combination of tBHQ + MnTMPyP is toxic to immortalized keratinocyte line HaCaT and cancer line MDA-MB-231; Figure S2: The combination of tBHQ + MnBuOE is toxic to cancer line MDA-MB-231; Figure S3: Use of dtBHQ in Jurkat cells to probe the mechanism of cell death suggests that oxidative stress is not from tBHQ redox cycling. Figure S4: Catalysis of (d)tBHQ oxidation by MnBuOE; Supplementary Methods: HaCaT Cell Culture.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.T., J.L., L.B., R.O. and A.L.E..; methodology, S.T., H.J., J.L., M.S.M., R.O., and A.L.E.; validation, S.T., M.S.M., R.O., and A.L.E..; formal analysis, S.T., H.J., J.L., M.S.M., and A.L.E.; investigation, S.T., H.J., J.L., L.B., G.P., G.T., and M.S.M.; resources, A.L.E and R.O.; data curation, A.L.E and R.O.; writing—original draft preparation, S.T. and A.L.E.; writing—review and editing, S.T., H.J., M.S.M., R.O., and A.L.E.; visualization, S.T. and A.L.E.; supervision, A.L.E.; project administration, A.L.E.; funding acquisition, M.S.M., R.O., and A.L.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funding was provided by Villanova University to A.L.E; funding was provided by the National Institutes of Health, R01CA255618 to R.O. and T32GM153375 to M.S.M.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the article/Supplementary Material; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the contributions of Dr. Jared Paul and his students David Sokoloski and Hailey Bierling in generating UV-Vis data for these compounds. We are also grateful to Gwenny Go, for contributing to best practices to minimize unintended oxidation of tBHQ, and to Margueritte Lalo, for experiments that informed our examination of toxicity of tBHQ and a manganese porphyrin in various cell types.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funder had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| tBHQ |

Tert-butylhydroquinone |

| tBQ |

Tert-butylquinone |

| dtBHQ |

Di-tert-butylhydroquinone |

| dtBQ |

Di-tert-butylquinone |

| MnBuOE |

MnTnBuOE-2-PyP5+

|

| DMEM |

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium |

| MPF |

Mouse prostate fibroblast |

References

- Chen, S.; Cao, Z.; Prettner, K.; Kuhn, M.; Yang, J.; Jiao, L.; Wang, Z.; Li, W.; Geldsetzer, P.; Bärnighausen, T.; et al. Estimates and Projections of the Global Economic Cost of 29 Cancers in 204 Countries and Territories From 2020 to 2050. JAMA Oncol. 2023, 9, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowenthal, R.M.; Eaton, K. Toxicity of Chemotherapy. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. North Am. 1996, 10, 967–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahavi, D.; Weiner, L. Monoclonal Antibodies in Cancer Therapy. Antibodies 2020, 9, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Cao, Y.J. Engineered T Cell Therapy for Cancer in the Clinic. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zugasti, I.; Espinosa-Aroca, Lady; Fidyt, K.; Mulens-Arias, V.; Diaz-Beya, M.; Juan, M.; Urbano-Ispizua, Á.; Esteve, J.; Velasco-Hernandez, T.; Menéndez, P. CAR-T Cell Therapy for Cancer: Current Challenges and Future Directions. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez, I.; Samuel W. Bott, B.S.; Anish S. Patel, B.S.; Collin G. Wolf, B.S.; Alexa R. Hospodar, B.S.;

Shivani Sampathkumar, B.S.; Shrank, W.Pricing of Monoclonal Antibody Therapies: Higher If Used for Cancer? 2018, 24.

- Di, M.; Potnis, K.C.; Long, J.B.; Isufi, I.; Foss, F.; Seropian, S.; Gross, C.P.; Huntington, S.F. Costs of Care during Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell Therapy in Relapsed or Refractory B-Cell Lymphomas. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2024, 8, pkae059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, J.; Cullen, J.J.; Buettner, G.R. Ascorbic Acid: Chemistry, Biology and the Treatment of Cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA - Rev. Cancer 2012, 1826, 443–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khezerlou, A.; Akhlaghi, A. pouya; Alizadeh, A.M.; Dehghan, P.; Maleki, P. Alarming Impact of the Excessive Use of Tert-Butylhydroquinone in Food Products: A Narrative Review. Toxicol. Rep. 2022, 9, 1066–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 21 CFR 172.185 -- TBHQ. Available online: https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-21/part-172/section-172.185 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- 21 CFR 177.2420 -- Polyester Resins, Cross-Linked. Available online: https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-21/part-177/section-177.2420 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- 952. Butylhydroquinone, Tert- (TBHQ) (WHO Food Additives Series 42). Available online: https://inchem.org/documents/jecfa/jecmono/v042je26.htm (accessed on 22 November 2021).

- Okubo, T.; Yokoyama, Y.; Kano, K.; Kano, I. Cell Death Induced by the Phenolic Antioxidant Tert-Butylhydroquinone and Its Metabolite Tert-Butylquinone in Human Monocytic Leukemia U937 Cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2003, 41, 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskandani, M.; Hamishehkar, H.; Ezzati Nazhad Dolatabadi, J. Cytotoxicity and DNA Damage Properties of Tert-Butylhydroquinone (TBHQ) Food Additive. Food Chem. 2014, 153, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Niu, H.; Gu, Y. Metabolic Kinetics of Tert-Butylhydroquinone and Its Metabolites in Rat Serum after Oral Administration by LC/ITMS. Lipids 2008, 43, 757–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.M.C.G.; Lau, S.S.; Dulik, D.; Murphy, D.; Van Ommen, B.; Van Bladeren, P.J.; Monks, T.J. Metabolism of Tert -Butylhydroquinone to S -Substituted Conjugates in the Male Fischer 344 Rat. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1996, 9, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batinic-Haberle, I.; Tovmasyan, A.; Spasojevic, I. Mn Porphyrin-Based Redox-Active Drugs: Differential Effects as Cancer Therapeutics and Protectors of Normal Tissue Against Oxidative Injury. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2018, 29, 1691–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, A.; Zhu, Y.; Tong, Q.; Kosmacek, E.A.; Lichter, E.Z.; Oberley-Deegan, R.E. The Addition of Manganese Porphyrins during Radiation Inhibits Prostate Cancer Growth and Simultaneously Protects Normal Prostate Tissue from Radiation Damage. Antioxidants 2018, 7, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batinic-Haberle, I.; Tovmasyan, A.; Huang, Z.; Duan, W.; Du, L.; Siamakpour-Reihani, S.; Cao, Z.; Sheng, H.; Spasojevic, I.; Alvarez Secord, A. H2O2-Driven Anticancer Activity of Mn Porphyrins and the Underlying Molecular Pathways. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 6653790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, K.; Kirkpatrick, J.; Batinic-Haberle, I.; Affronti, M.; Woodring, S.; Iden, D.; Panta, S.; Lipp, E.; Healy, P.; Herndon, J.; et al. ACTR-28. PHASE 1 DOSE ESCALATION TRIAL OF THE SAFETY OF BMX-001 CONCURRENT WITH RADIATION THERAPY AND TEMOZOLOMIDE IN NEWLY DIAGNOSED PATIENTS WITH HIGH-GRADE GLIOMAS. Neuro-Oncol. 2018, 20, vi17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosmacek, E.A.; Oberley-Deegan, R.E. Adipocytes Protect Fibroblasts from Radiation-Induced Damage by Adiponectin Secretion. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braeuning, A.; Vetter, S.; Orsetti, S.; Schwarz, M. Paradoxical Cytotoxicity of Tert-Butylhydroquinone in Vitro: What Kills the Untreated Cells? Arch. Toxicol. 2012, 86, 1481–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauman, B.M.; Jeong, C.; Savage, M.; Briker, A.L.; Janigian, N.G.; Nguyen, L.L.; Kemmerer, Z.A.; Eggler, A.L. Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde: Oxidizable Phenol-Generated Reactive Oxygen Species Enhance Sulforaphane’s Antioxidant Response Element Activation, Even as They Suppress Nrf2 Protein Accumulation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2018, 124, 532–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boss, M.K.; Dewhirst, M.W.; Sampaio, R.S.; Bennett, A.; Tovmasyan, A.; Berman, K.G.; Beaven, A.W.; Rizzieri, D.A.; Batinic-Haberle, I.; Hauck, M.L.; et al. Potential for a Novel Manganese Porphyrin Compound as Adjuvant Canine Lymphoma Therapy. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2017, 80, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, Barry; Gutteridge, John M. C. Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press, 2015; ISBN 978-0-19-871747-8. [Google Scholar]

- Bienert, G.P.; Schjoerring, J.K.; Jahn, T.P. Membrane Transport of Hydrogen Peroxide. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA - Biomembr. 2006, 1758, 994–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, K.; Jain, S.K. Oxidative Stress and Apoptosis. Pathophysiology 2000, 7, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gant, T.W.; Rao, D.N.; Mason, R.P.; Cohen, G.M. Redox Cycling and Sulphydryl Arylation; Their Relative Importance in the Mechanism of Quinone Cytotoxicity to Isolated Hepatocytes. Chem. Biol. Interact. 1988, 65, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, Y.; Kumagai, T.; Yoshida, C.; Naito, Y.; Miyamoto, M.; Ohigashi, H.; Osawa, T.; Uchida, K. Pivotal Role of Electrophilicity in Glutathione S-Transferase Induction by Tert-Butylhydroquinone. Biochemistry 2003, 42, 4300–4309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Thomas, B.; Sachdeva, R.; Arterburn, L.; Frye, L.; Hatcher, P.G.; Cornwell, D.G.; Ma, J. Mechanism of Arylating Quinone Toxicity Involving Michael Adduct Formation and Induction of Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2006, 103, 3604–3609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LoPachin, R.M.; Gavin, T. Reactions of Electrophiles with Nucleophilic Thiolate Sites: Relevance to Pathophysiological Mechanisms and Remediation. Free Radic. Res. 2016, 50, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endo, S.; Nishiyama, A.; Suyama, M.; Takemura, M.; Soda, M.; Chen, H.; Tajima, K.; El-Kabbani, O.; Bunai, Y.; Hara, A.; et al. Protective Roles of Aldo-Keto Reductase 1B10 and Autophagy Against Toxicity Induced by p-Quinone Metabolites of Tert-Butylhydroquinone in Lung Cancer A549 Cells. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2015, 234, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, B.P.; Weissman, J.S. Oxidative Protein Folding in Eukaryotes : Mechanisms and Consequences. J. Cell Biol. 2004, 164, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, G.; Logue, S.E. Unfolding the Interactions between Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa, C.D.; Wu, R.F.; Terada, L.S. ROS Signaling and ER Stress in Cardiovascular Disease. Mol. Aspects Med. 2018, 63, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Pang, J.; Liao, Z.; Chen, G.; Zhong, X.; Cao, X.; Lin, Y.; Guan, D.; Tian, Y.; et al. ER Stress Sensor PERK Drives Ferroptosis by Disrupting MAMs-Mediated Mitochondrial Homeostasis and Promoting mtROS Accumulation in Acute Myocardial Infarction. Pharmacol. Res. 2025, 222, 108029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, D.; Powolny, A.A.; Antosiewicz, J.; Hahm, E.-R.; Bommareddy, A.; Zeng, Y.; Desai, D.; Amin, S.; Herman-Antosiewicz, A.; Singh, S.V. Cellular Responses to Dietary Cancer Chemopreventive Agent D,L-Sulforaphane in Human Prostate Cancer Cells Are Initiated by Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species. Pharm. Res. 2009, 26, 1729–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, W.Y.; Choi, B.T.; Lee, W.H.; Choi, Y.H. Sulforaphane Generates Reactive Oxygen Species Leading to Mitochondrial Perturbation for Apoptosis in Human Leukemia U937 Cells. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2008, 62, 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochstein, P. Futile Redox Cycling: Implications for Oxygen Radical Toxicity. Fundam. Appl. Toxicol. 1983, 3, 215–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, J.L.; Dunlap, T.L. Formation and Biological Targets of Quinones: Cytotoxic versus Cytoprotective Effects. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinkova-Kostova, A.T.; Talalay, P. NAD(P)H:Quinone Acceptor Oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1), a Multifunctional Antioxidant Enzyme and Exceptionally Versatile Cytoprotector. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2010, 501, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsunaga, T.; Endo, S.; Takemura, M.; Soda, M.; Yamamura, K.; Tajima, K.; Miura, T.; Terada, T.; El-Kabbani, O.; Hara, A. Reduction of Cytotoxic p-Quinone Metabolites of Tert-Butylhydroquinone by Human Aldo-Keto Reductase (AKR) 1B10. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2012, 27, 553–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, D.; Siegel, D. Functions of NQO1 in Cellular Protection and CoQ10 Metabolism and Its Potential Role as a Redox Sensitive Molecular Switch. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Böttger, F.; Vallés-Martí, A.; Cahn, L.; Jimenez, C.R. High-Dose Intravenous Vitamin C, a Promising Multi-Targeting Agent in the Treatment of Cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 40, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodeker, K.L.; Smith, B.J.; Berg, D.J.; Chandrasekharan, C.; Sharif, S.; Fei, N.; Vollstedt, S.; Brown, H.; Chandler, M.; Lorack, A.; et al. A Randomized Trial of Pharmacological Ascorbate, Gemcitabine, and Nab-Paclitaxel for Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer. Redox Biol. 2024, 77, 103375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, M.K.; Tovmasyan, A.; Batinic-Haberle, I.; Devi, G.R. Mn Porphyrin in Combination with Ascorbate Acts as a Pro-Oxidant and Mediates Caspase-Independent Cancer Cell Death. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 68, 302–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovmasyan, A.; Sampaio, R.S.; Boss, M.-K.; Bueno-Janice, J.C.; Bader, B.H.; Thomas, M.; Reboucas, J.S.; Orr, M.; Chandler, J.D.; Go, Y.-M.; et al. Anticancer Therapeutic Potential of Mn Porphyrin/Ascorbate System. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 89, 1231–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pensabene, K.M.; LaMorte, J.; Allender, A.E.; Wehr, J.; Kaur, P.; Savage, M.; Eggler, A.L. Acute Oxidative Stress Can Paradoxically Suppress Human NRF2 Protein Synthesis by Inhibiting Global Protein Translation. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Toxic effects of combining tBHQ and a manganese porphyrin superoxide dismutase mimetic. (A) The two-electron redox cycling of tBHQ and dtBHQ, catalyzed by transition metals, produces superoxide. Oxidation by one electron produces the semiquinone, with loss of the second electron producing the quinone. While the tBQ quinone is an electrophilic α,β unsaturated carbonyl (indicated in red), the corresponding carbon in dtBQ is sterically blocked from reacting with a nucleophile by the bulky t-butyl group. Cellular reductases can reduce a quinone by two electrons back to the hydroquinone, allowing for redox cycling with superoxide as a product. (B) Upon production of superoxide in redox cycling, subsequent reactions and transformations result in biologically-relevant reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. In particular, the highly spontaneous reaction of nitric oxide with superoxide creates the damaging oxidant peroxynitrite, and the rapid conversion of superoxide to hydrogen peroxide catalyzed by superoxide dismutase is critical to preventing this. The metal-catalyzed Haber-Weiss reaction of superoxide with hydrogen peroxide generates the most damaging of all reactive oxygen species, the hydroxyl radical. A superoxide dismutase mimetic would be expected to significantly limit production of peroxynitrite and hydroxyl radical by more fully converting superoxide to hydrogen peroxide. (C) PC3 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of tBHQ alone or in combination with MnBuOE. Viability was measured using a CellTiter Glo assay and normalized to the untreated control. (D) PC3 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of MnBuOE alone or in combination with 10 µM tBHQ. Viability was measured using a CellTiter Glo assay and normalized to the untreated control. (E) Jurkat cells were treated with increasing concentrations of tBHQ alone or in combination with 1 µM MnBuOE. Viability was measured using a CellTiter Glo assay and normalized to the untreated control. n=5 (technical replicates). “Mn” in the legends for C, D, and E is the abbreviation for “MnBuOE”.

Figure 1.

Toxic effects of combining tBHQ and a manganese porphyrin superoxide dismutase mimetic. (A) The two-electron redox cycling of tBHQ and dtBHQ, catalyzed by transition metals, produces superoxide. Oxidation by one electron produces the semiquinone, with loss of the second electron producing the quinone. While the tBQ quinone is an electrophilic α,β unsaturated carbonyl (indicated in red), the corresponding carbon in dtBQ is sterically blocked from reacting with a nucleophile by the bulky t-butyl group. Cellular reductases can reduce a quinone by two electrons back to the hydroquinone, allowing for redox cycling with superoxide as a product. (B) Upon production of superoxide in redox cycling, subsequent reactions and transformations result in biologically-relevant reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. In particular, the highly spontaneous reaction of nitric oxide with superoxide creates the damaging oxidant peroxynitrite, and the rapid conversion of superoxide to hydrogen peroxide catalyzed by superoxide dismutase is critical to preventing this. The metal-catalyzed Haber-Weiss reaction of superoxide with hydrogen peroxide generates the most damaging of all reactive oxygen species, the hydroxyl radical. A superoxide dismutase mimetic would be expected to significantly limit production of peroxynitrite and hydroxyl radical by more fully converting superoxide to hydrogen peroxide. (C) PC3 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of tBHQ alone or in combination with MnBuOE. Viability was measured using a CellTiter Glo assay and normalized to the untreated control. (D) PC3 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of MnBuOE alone or in combination with 10 µM tBHQ. Viability was measured using a CellTiter Glo assay and normalized to the untreated control. (E) Jurkat cells were treated with increasing concentrations of tBHQ alone or in combination with 1 µM MnBuOE. Viability was measured using a CellTiter Glo assay and normalized to the untreated control. n=5 (technical replicates). “Mn” in the legends for C, D, and E is the abbreviation for “MnBuOE”.

Figure 2.

The tBHQ-MnBuOE combination induces mitochondrial superoxide formation in cancer cells and generates toxic levels of hydrogen peroxide. (A, B) The MitoSOX assay was used to measure mitochondrial superoxide formation in PC3 cells exposed to 20 µM tBHQ and MnBuOE, singly or in combination. n=7-9 (technical replicates). For the tBHQ + Mn condition, a minimum of 5,000 events were collected. (C, D) The MitoSOX assay was used to measure mitochondrial superoxide formation in Jurkat cells exposed to 10 µM tBHQ and MnBuOE, singly or in combination. n=5-6 (technical replicates). (E) The CellTiter Glo assay was used to measure the viability of PC3 cells treated with 10 µM tBHQ alone, with tBHQ and MnBuOE, or with tBHQ, MnBuOE, and catalase for 24. Viability was normalized to the untreated control. n=5 (technical replicates).

Figure 2.

The tBHQ-MnBuOE combination induces mitochondrial superoxide formation in cancer cells and generates toxic levels of hydrogen peroxide. (A, B) The MitoSOX assay was used to measure mitochondrial superoxide formation in PC3 cells exposed to 20 µM tBHQ and MnBuOE, singly or in combination. n=7-9 (technical replicates). For the tBHQ + Mn condition, a minimum of 5,000 events were collected. (C, D) The MitoSOX assay was used to measure mitochondrial superoxide formation in Jurkat cells exposed to 10 µM tBHQ and MnBuOE, singly or in combination. n=5-6 (technical replicates). (E) The CellTiter Glo assay was used to measure the viability of PC3 cells treated with 10 µM tBHQ alone, with tBHQ and MnBuOE, or with tBHQ, MnBuOE, and catalase for 24. Viability was normalized to the untreated control. n=5 (technical replicates).

Figure 3.

The tBHQ-MnBuOE combination causes apoptotic cell death in cancer cells. (A, B) The Annexin V/RedDot assay was used to measure apoptotic and necrotic cell death in PC3 cells exposed to 20 µM tBHQ and 1 µM MnBuOE, singly or in combination. n=3-6 (technical replicates). (C, D) The Annexin V/RedDot assay was used to measure apoptotic and necrotic cell death in Jurkat cells exposed to 10 µM tBHQ and 1 µM MnBuOE, singly or in combination. n=6 (technical replicates).

Figure 3.

The tBHQ-MnBuOE combination causes apoptotic cell death in cancer cells. (A, B) The Annexin V/RedDot assay was used to measure apoptotic and necrotic cell death in PC3 cells exposed to 20 µM tBHQ and 1 µM MnBuOE, singly or in combination. n=3-6 (technical replicates). (C, D) The Annexin V/RedDot assay was used to measure apoptotic and necrotic cell death in Jurkat cells exposed to 10 µM tBHQ and 1 µM MnBuOE, singly or in combination. n=6 (technical replicates).

Figure 4.

Use of dtBHQ to probe the mechanism of cell death suggests that oxidative stress is not due to tBHQ redox cycling. (A) UV-vis spectra of the tBHQ-MnBuOE reaction. The dashed line is the spectrum of the tBHQ-MnBuOE mixture immediately after mixing, and the solid line is the reaction near completion (22 min). (B) UV-vis spectra of the tBHQ-MnBuOE reaction. The dashed line is the spectrum of the dtBHQ-MnBuOE mixture immediately after mixing, and the solid line is the reaction near completion (42 min). (C) The viability of PC3 cells after addition of dtBHQ alone or in combination with MnBuOE for 24 h, as measured by CTGlo assay. Viability was normalized to the untreated control. n=5 (technical replicates). (D, E) Mitochondrial superoxide was measured in PC3 cells by the MitoSOX assay. Cells were treated with dtBHQ and MnBuOE alone or in combination. n=5-9 (technical replicates). (F, G) In the same treatments as for C and D, apoptosis or necrosis in PC3 cells was measured by the Annexin V/RedDot assay. n=3-5 (technical replicates).

Figure 4.

Use of dtBHQ to probe the mechanism of cell death suggests that oxidative stress is not due to tBHQ redox cycling. (A) UV-vis spectra of the tBHQ-MnBuOE reaction. The dashed line is the spectrum of the tBHQ-MnBuOE mixture immediately after mixing, and the solid line is the reaction near completion (22 min). (B) UV-vis spectra of the tBHQ-MnBuOE reaction. The dashed line is the spectrum of the dtBHQ-MnBuOE mixture immediately after mixing, and the solid line is the reaction near completion (42 min). (C) The viability of PC3 cells after addition of dtBHQ alone or in combination with MnBuOE for 24 h, as measured by CTGlo assay. Viability was normalized to the untreated control. n=5 (technical replicates). (D, E) Mitochondrial superoxide was measured in PC3 cells by the MitoSOX assay. Cells were treated with dtBHQ and MnBuOE alone or in combination. n=5-9 (technical replicates). (F, G) In the same treatments as for C and D, apoptosis or necrosis in PC3 cells was measured by the Annexin V/RedDot assay. n=3-5 (technical replicates).

Figure 5.

tBQ is less potent than the tBHQ-MnBuOE combination in two cancer cell lines. Cell death from treatment with tBQ was measured in (A) Jurkat cells by the CTF assay and (B) MDA-MB-231 cells by the BCA assay (B). For each condition, viability was normalized to the signal for the lowest concentration of tBHQ or tBQ. n=6 (technical replicates).

Figure 5.

tBQ is less potent than the tBHQ-MnBuOE combination in two cancer cell lines. Cell death from treatment with tBQ was measured in (A) Jurkat cells by the CTF assay and (B) MDA-MB-231 cells by the BCA assay (B). For each condition, viability was normalized to the signal for the lowest concentration of tBHQ or tBQ. n=6 (technical replicates).

Figure 6.

Treatment with tBHQ shows no toxicity in primary cells than to PC3 cells. Viability upon treatment with tBHQ alone or in combination with MnBuOE for (A) PC3 cells or (B) MPF cells, measured by the Trypan blue exclusion test. n=3 biological replicates.

Figure 6.

Treatment with tBHQ shows no toxicity in primary cells than to PC3 cells. Viability upon treatment with tBHQ alone or in combination with MnBuOE for (A) PC3 cells or (B) MPF cells, measured by the Trypan blue exclusion test. n=3 biological replicates.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).