1. Introduction

Porphyrins are polycyclic aromatic compounds consisting of four pyrrole rings interconnected by methine bridges, forming an extended conjugated π-electron system with 18 delocalized electrons. Their ability to coordinate metal ions within the macrocyclic cavity determines their unique catalytic properties. These molecules are fundamental components of numerous biologically significant proteins, playing key roles in essential processes such as oxygen transport, electron transfer, and enzymatic catalysis. A prominent example is heme, which serves as a prosthetic group in hemoglobin and cytochromes, where the coordinated iron ion (Fe

2+) undergoes cyclic redox reactions, facilitating electron transport in processes such as cellular respiration [

1]. Beyond their biological significance, porphyrins exhibit distinctive photochemical and catalytic properties, making them attractive for biomedical applications, particularly in oncology. Their role as photosensitizers in photodynamic therapy (PDT) and as contrast agents for fluorescence and photoacoustic imaging is well established [

2]. Upon light absorption, porphyrins undergo transition to triplet excited states, subsequently generating reactive oxygen species (ROS), which trigger oxidative stress, leading to apoptosis or necrosis of targeted cells. Furthermore, photogenerated ROS contribute to tumor vasculature disruption, trigger inflammatory responses, enhance the expression of heat-shock proteins, and promote immune cell infiltration, thereby supporting the development of long-term immune memory. [

3,

4]. A key advantage of PDT lies in its spatial selectivity, as ROS production occurs exclusively in the illuminated region, minimizing systemic side effects [

5,

6]. However, the clinical use of porphyrin-based photosensitizers in PDT is limited by poor light penetration into deep tissues, restricting its efficacy mainly to superficial tumors. To address this limitation, alternative strategies have been explored, including chemical modulation, such as structural modifications involving the reduction of pyrrole rings, attachment of substituents to enhance long-wavelength absorption and biocompatibility, or the addition of adjuvants to improve therapeutic efficacy [

7]. Among potential adjuvants, ascorbate (vitamin C) has attracted considerable attention for its ability to enhance the therapeutic efficacy of porphyrin-based systems, particularly when light activation is not feasible [

8].

L-ascorbic acid (AA) is a key regulator of lysyl and prolyl hydroxylase activity, making it indispensable for collagen biosynthesis [

9]. It plays a fundamental role in maintaining the homeostasis of connective tissue; however, due to a mutation in the gene encoding L-gulono-γ-lactone oxidase, humans lack the ability to synthesize it endogenously, necessitating dietary intake. Under physiological conditions, the plasma concentration of AA is approximately 90 µM, with a maximum level of about 220 µM achievable through oral supplementation. At these concentrations, AA primarily functions as an antioxidant, scavenging ROS to protect cells from oxidative stress and prevent degradation of subcellular structures [

10]. However, at pharmacological concentrations, AA exhibits a distinct prooxidant effect, which has been linked to its potential anticancer activity. Intravenous administration can elevate plasma ASC levels to approximately 0.5 mM without causing severe adverse effects [

11]. Transiently, plasma concentrations as high as 20 mM can be achieved, leading to a disruption of cellular redox homeostasis. This oxidative imbalance contributes to glutathione oxidation and depletion of intracellular antioxidant reserves, as well as the redox cycling of iron ions, which often accumulate in cancer cells due to ferritin overexpression. These processes facilitate the generation of hydroxyl radicals via the Fenton and Haber-Weiss reactions, ultimately contributing to cytotoxic effects [

12].

The cytotoxic effect of pharmacological ascorbate appears to be selective toward cancer cells, which often display weakened antioxidant defense systems and increased susceptibility to ferroptosis resulting from metal ion accumulation [

12]. Additionally, certain tissues, particularly tumors, can locally accumulate higher concentrations of ASC, further enhancing its cytotoxic potential [

14]. Cellular uptake of vitamin C occurs primarily through sodium-dependent vitamin C transporters (SVCT-1 in intestinal epithelial cells and SVCT-2 in other tissues) [

15,

16], as well as via glucose transporters (GLUT). They mediate the uptake of dehydroascorbate (DHA), which is the oxidized form of ascorbate, taken up via GLUT transporters and intracellularly reduced to ASC. Structurally similar to glucose, DHA enters cells through GLUT transporters and is subsequently reduced intracellularly to ASC. This mechanism is particularly relevant in cancer cells, which exhibit increased glucose uptake and GLUT overexpression, enabling preferential accumulation of ASC in tumor tissue [

10]. Some studies also suggest that a fraction of ASC may directly diffuse through lipid membranes, although this is considered a secondary uptake mechanism [

11]. Both in vitro and clinical studies indicate that pharmacological doses of vitamin C can exert selective cytotoxic effects on cancer cells, presenting a promising adjunctive strategy in oncology [

17]. An emerging therapeutic concept involves the combination of ASC and manganese porphyrins as a complementary approach to conventional porphyrin-based photodynamic therapy (PDT), potentially enhancing therapeutic efficacy.

Manganese porphyrins (MnPs) have been explored as redox-active compounds with potential roles in radio- and chemosensitization, and some analogs have also shown radioprotective properties in normal tissues [

18]. This dual function, combined with their superoxide dismutase (SOD)-mimicking catalytic activity, makes them particularly valuable in oncology, as they can enhance the effectiveness of radiotherapy and chemotherapy while mitigating radiation-induced damage to normal cells. Several MnPs have been developed that catalyze the oxidation of ASC and thiols, leading to the generation of ROS. The redox potential (E

1/

2) of the Mn

3+/Mn

2+ couple plays a crucial role in determining the ability of Mn

3+ to participate in redox cycling with ASC [

19]. When the half-cell reduction potential (E

1/

2) of MnPs is well-matched with the redox potential of the Asc

•−/AscH

− pair, ROS production via redox cycling is significantly enhanced [

20]. Several MnPs have already been tested in combination with ASC on cancer cells, yielding promising therapeutic outcomes [

18,

19,

21].

These findings prompted us to investigate the biological activity of two manganese porphyrins, MnTPPS and MnF

2BMet, obtained following a general synthetic route previously described for related porphyrins prepared for other applications. These compounds are structurally related to porphyrin-based photosensitizers used in PDT, but their design allows them to undergo redox reactions without the need for light activation [

7,

22,

23,

24]. In particular, we aimed to assess the synergy between the cytotoxic effects of these MnPs and ASC. Furthermore, we explored the molecular mechanisms underlying this cytotoxicity, with particular attention to the contribution of hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2) in mediating these effects. To achieve this, we employed an experimental model integrating analyses of glutathione (GSH) depletion, lipid peroxidation, and direct H

2O

2 quantification in a panel of normal and cancer cell lines undergone MnPs/ASC treatment in vitro.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines

Human MCF-7 and PANC-1, and rat cancer AT-2 cells were cultured under standard conditions (37 °C, 5% CO2) in RPMI 1640 medium (Sigma). Glioblastoma cell lines U87 and T98G, along with normal human dermal fibroblasts (HDF), were maintained under identical conditions in DMEM-high glucose medium (Sigma). Culture media were supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco) and 1% Antibiotic-Antimycotic Solution (Merck; 100 U/mL penicillin, 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin, 0.25 µg/mL amphotericin B). Cells were harvested using TrypLE™ (Gibco), counted using a Z2 particle counter (Beckman Coulter), and seeded into multi-well tissue culture plates (Falcon®).

2.2. Manganese Porphyrins

Mn(III) tetrakis(4-benzoic acid) porphyrin chloride (MnTBAP) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The manganese(III) porphyrins were prepared following a general multistep procedure commonly used for related metalloporphyrins, involving condensation via the nitrobenzene method, chlorosulfonation, and subsequent manganese(III) complexation[

25]. Solid manganese porphyrins (MnPs) were stored in light-protected vials at −20 °C. When dissolved in DMSO, solutions were stored at 4 °C in light-protected vials. MnPs were added to cell cultures for 24 hours, after which the medium was removed, and cells were washed with PBS (Gibco) to eliminate unbound porphyrins. The final DMSO concentration in the medium was 0.1% for 5 µM porphyrins and 1% for 50 µM porphyrins. Control samples received the same DMSO concentration without porphyrins.

2.3. Optical Properties

Electronic absorption spectra of MnTPPS and MnF2BMet were recorded in PBS using quartz cuvettes with a 1 cm path length. Measurements were performed with a UV-3600 Shimadzu spectrophotometer, covering the 300–800 nm wavelength range. Fluorescence spectra were acquired in the 500–750 nm range following excitation at the respective Soret bands. Measurements were conducted using a RF-6000 Shimadzu Spectrophotometer. Samples were initially adjusted to an absorbance of 0.2 at the Soret band and subsequently diluted 100-fold for fluorescence analysis.

2.4. Cytotoxicity Assay

In all experiments, a sequential treatment approach was applied: cells were incubated with MnPs for 24 hours, after which unbound porphyrins were removed by washing with PBS (Sigma). ASC was added in fresh medium. The ascorbate solution was freshly prepared immediately before use. Cells were seeded into 24-well plates at a density of 10,000 cells/well. After 24 hours of incubation, cell viability was assessed using the Trypan Blue (Sigma) exclusion assay. Cytotoxicity of MnPs was evaluated after the same incubation period, with the same procedure but without adding ASC. The experiments were done in three biological replicates.

For proliferation analysis, cells were seeded in 12-well plates at a density of 10,000 cells per well and then incubated for 24 hours with MnPs. Subsequently, unbound porphyrins were removed, and fresh culture medium containing ASC was added. Cell were harvested after 96 hours of incubation with ASC. Cell counts were performed using a Z2 particle counter (Beckman Coulter). Experiments with extracellular catalase were conducted using catalase from bovine liver (Sigma). Catalase was dissolved in PBS and added to the culture medium at a final concentration of 200–500 U/mL.

2.5. Kinetics of Propidium Iodide Uptake

Propidium iodide (PI) uptake kinetics was monitored using time-lapse videomicroscopy on 24-well plates (Falcon®). MCF-7 cells were seeded at a density of 10,000 cells/well and incubated with 5 µM MnTPPS or 5 µM MnF2BMet for 24 hours. After removing unbound porphyrins, fresh medium containing 0.5 or 1 mM ASC was added, along with propidium iodide. Cell viability was monitored for 12 hours at 5-minute intervals using a Leica DMI6000B imaging system equipped with integrated modulation contrast (IMC; Hoffman contrast), fluorescence module, and environmental control for temperature (37 °C) and CO2 (5%). Propidium iodide fluorescence intensity was measured over time in specific cells (n=30). Cell imaging was started 30 min after ASC addition.

2.6. Cell Migration Assay

MCF-7 cell migration was analyzed using 24-well plates (Falcon®). Cells were seeded at a density of 10,000 cells/well and incubated with 5 µM MnTPPS or 5 µM MnF

2BMet for 24 hours. After removing unbound porphyrins, fresh medium containing ascorbate was added. Cell movement was recorded for 8 hours at 5-minute intervals using a Leica DMI6000B imaging system equipped with integrated modulation contrast (IMC; Hoffman contrast), CO

2 (5%), and temperature (37 °C) monitoring. Cell migration trajectories were manually tracked using Hiro v.1.0.0.4 software (developed by W. Czapla), and the speed of movement (µm/min) was calculated [

26].

2.7. Fluorescence Microscopy

For fluorescence microscopy studies, MCF-7 cells were seeded into 12-well plates on UVC-sterilized coverslips at a density of 10,000 cells/well. Cells were incubated for 24 hours with 5 µM MnPs, washed with PBS, and subsequently incubated with 0.5 mM ASC for 6 hours. Cells were then fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100. Non-specific binding sites were blocked with 2% BSA (Invitrogen). Actin cytoskeleton visualization was performed using AlexaFluor546-conjugated phalloidin (1:80), and nuclear staining was performed with Hoechst 33,258 (Sigma, 1–2 µg/mL). After 45 minutes of incubation, samples were mounted in Moviol 4–88 mounting medium. Images were acquired using a Leica Stellaris 5 confocal microscope [

27].

2.8. Quantification of GSH, Lipid Peroxidation, and Mitochondrial Membrane Potential

MCF-7 cells were seeded at 10,000 cells/well in 24-well plates (Eppendorf). Cells were incubated with 5 µM MnTPPS or 5 µM MnF

2BMet for 24 hours, washed with PBS, and incubated in phenol red-free RPMI 1640 medium. GSH levels were quantified using the ThiolTracker™ Violet assay (Invitrogen™) after 2 hours of incubation with 0.5 mM ASC. Lipid peroxidation was assessed using the Image-iT™ Lipid Peroxidation Kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Mitochondrial membrane potential was analyzed using the JC-1 fluorescence probe in glass-bottom culture dishes (Thermo Fisher™). MCF-7 cells were preloaded with 20 µM MnF

2BMet for 24 hours, washed with PBS, and incubated in phenol red-free RPMI 1640 [

28]. Red-to-green fluorescence ratio was measured 2 hours after the addition of 0.5 mM ASC. All imaging was performed using a Leica Stellaris 5 microscope equipped with a CO

2 chamber (5%) and temperature control (37 °C).

2.9. Quantification of Intracellular H2O2

Intracellular hydrogen peroxide levels were measured using the HyPer7 fluorescent probe [

29]. MCF-7 cells were transfected with pCS2+HyPer7-NES plasmid (kindly provided by Dr. Vsevolod Belousov; Addgene plasmid #136467) using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen), according to manufacturer’s protocol. 24 hours later, 5 µM MnF

2BMet was added and the cells were incubated in its presence for the next 24 hours. Imaging was performed in glass-bottom culture dishes (Ibidi) using a Leica Stellaris 5 confocal microscope with CO

2 (5%) and temperature control (37 °C). Images were collected at 30-second intervals over 6 minutes. After initial 90 seconds of imaging, ASC was added to achieve a final concentration of 0.1 mM. Cells were imaged using excitation at 405 and 488 nm, with emission in the green fluorescence range. Fluorescence analysis was performed using a custom ImageJ macro, which generated 488/405 nm ratiometric images by pixel-by-pixel division and applied threshold-based masks to automatically detect individual cells. For each time point, the average ratio within each cell was calculated.

2.10. Quantification of Intracellular Ascorbate Levels

Intracellular ASC levels were measured using the Ascorbic Acid Assay Kit II (Sigma). MCF-7 cells (1 × 106) were seeded in culture dishes and treated with either 0.5 or 2 mM ASC, or 0.5 or 2 mM DHA in PBS for 90 minutes. Then, the cells were washed twice with PBS, lysed, and centrifuged to remove cellular debris. Proteins were eliminated from the supernatant with a 10 kDa MWCO spin filter, and the reducing activity of each sample was measured at 595 nm. For each sample, a control containing ASC oxidase was included to distinguish between the oxidized and reduced forms of ASC. All samples were prepared in triplicate to ensure statistical accuracy.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

The statistical significance of variances in cell migration speed, cell viability and fluorescence assay was evaluated using the Student’s t-test. All statistical analyses were conducted using STATISTICA 13, with a threshold for statistical significance set at p < 0.05.

4. Discussion

The hypothesis that manganese porphyrins catalyze ascorbate oxidation, yielding ascorbyl radicals and hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2) with preferential toxicity toward cancer cells, has been widely investigated [18, 21, 34). MnPs are recognized as potent redox-active catalysts that facilitate the formation of ROS from ASC, which preferentially damages cancer cells due to their heightened sensitivity to oxidative stress and impaired antioxidant defenses [

3]. Despite the promising results of previous studies, the precise mechanisms underlying MnPs-ASC cytotoxicity remain only partially understood. Notably, in several studies the role of H

2O

2 as a major mediator was inferred from indirect markers such as GSH depletion or lipid peroxidation, with fewer reports providing direct H

2O

2 readouts [

35]. Furthermore, both intracellular and extracellular sources have been discussed, although multiple studies have supported a predominant extracellular contribution under specific conditions [

19,

36,

37].

Here, we evaluated two synthetic MnPs (MnTPPS and MnF2BMet) for their ability to efficiently catalyze ASC oxidation, generate H2O2, and exert cytotoxic effects in cancer cells. Our study indicates a predominant contribution of extracellular H2O2 to the observed cytotoxicity, reinforcing the relevance of extracellular ROS dynamics in MnP–ascorbate responses.

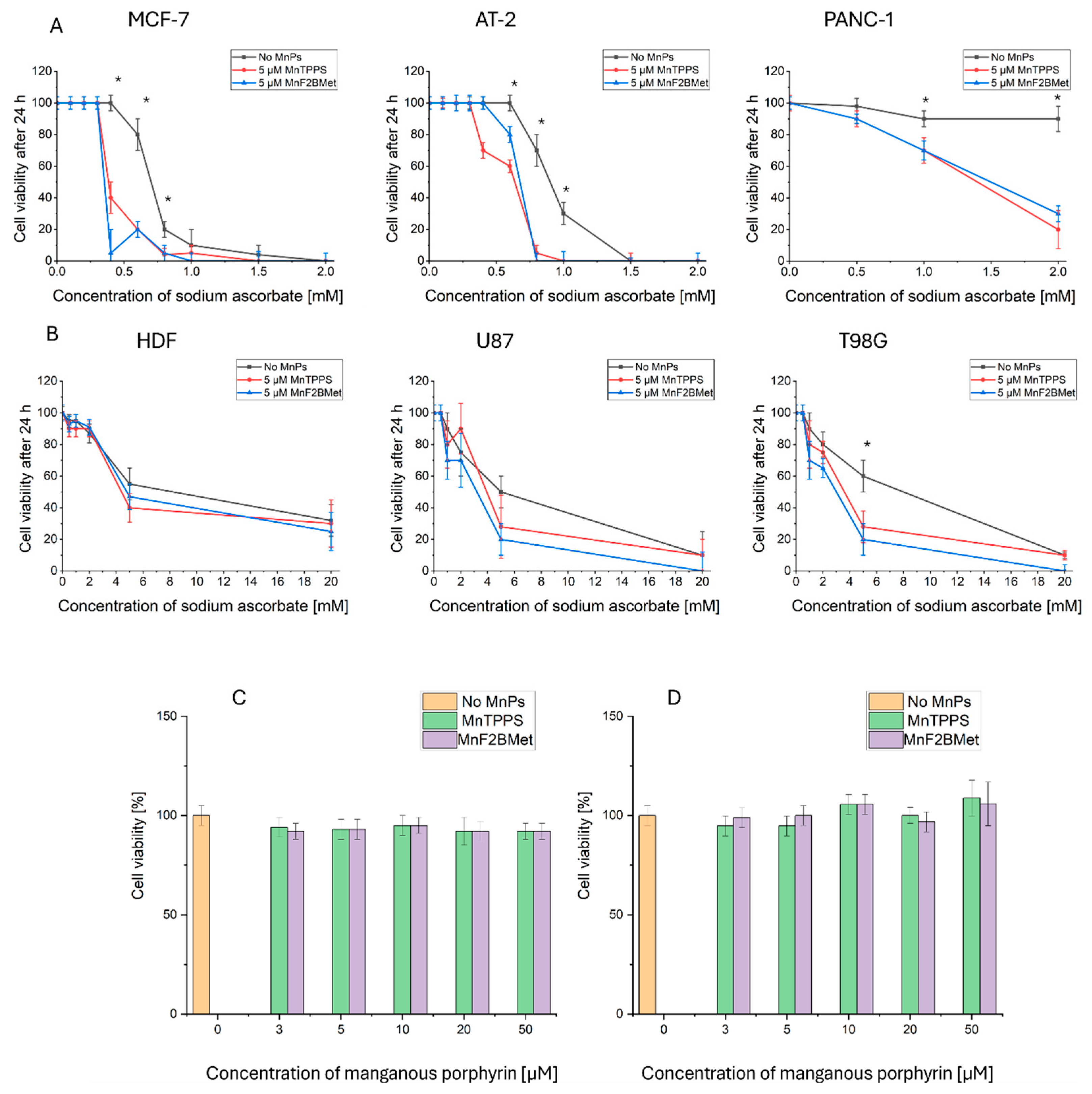

Previous studies have reported that some MnPs exhibit intrinsic cytotoxicity when administered alone [

38]. However, our results demonstrate that MnTPPS and MnF

2BMet, when applied at standard in vitro concentrations (5–20 µM), do not induce significant cytotoxic nor do they affect the migratory or proliferative potential of cancer cells [

18,

21,

38,

39]. These findings align with earlier observations regarding the redox properties of manganese porphyrins in breast cancer models [

34,

40,

41]. In contrast, when combined with ASC, both MnPs significantly enhance ASC-induced cytotoxicity in MCF-7 cells, consistent with the proposed mechanism of ASC oxidation and subsequent ROS generation. The extent of ascorbate oxidation by manganese porphyrins, with H

2O

2 generation, depends on their redox and structural properties [

21]. To date, numerous MnPs have been developed that catalyze ASC oxidation, generating ROS such as superoxide (O

2•−) and H

2O

2. Among these, 5''N-substituted pyridyl-porphyrins have been specifically designed as superoxide dismutase (SOD) mimetics [

38]. Notably, the ASC concentrations used in our experiments are physiologically relevant, corresponding to plasma levels observed in patients receiving pharmacological ASC administration [

11,

17]. Some studies have even reported ASC concentrations as high as 20 mM in patient sera shortly after intravenous administration [

13]. Thus, our findings add to reports of ROS-dependent cytotoxicity in cancer models and support further evaluation of this approach.

To date, most studies on the pro-oxidative activity of MnPs have been based on oxygen consumption assays and indirect detection of H

2O

2 in cell-free systems [

35]. It has been shown that numerous MnPs generate ROS under cell-free conditions, particularly when combined with high concentrations of ASC [

18,

19,

34]. These findings indirectly suggest the induction of oxidative stress in cells treated with MnPs/ASC; however, the intracellular environment is highly complex and contains many redox-active species that can interact with MnPs, including thiols, superoxide anions (O

2•

−), and hydrogen peroxide. Moreover, local pH fluctuations further modulate these interactions [

34]. Previous in vitro studies have suggested that MnPs-ASC interactions lead to ROS generation, but these conclusions were mostly based on indirect markers such as GSH depletion or lipid peroxidation. It has been demonstrated that H

2O

2 is crucial for the cytotoxic properties of MnPs-ASC, as the application of extracellular catalase abolished the cytotoxic effect. This indicates an extracellular mechanism of ROS generation.

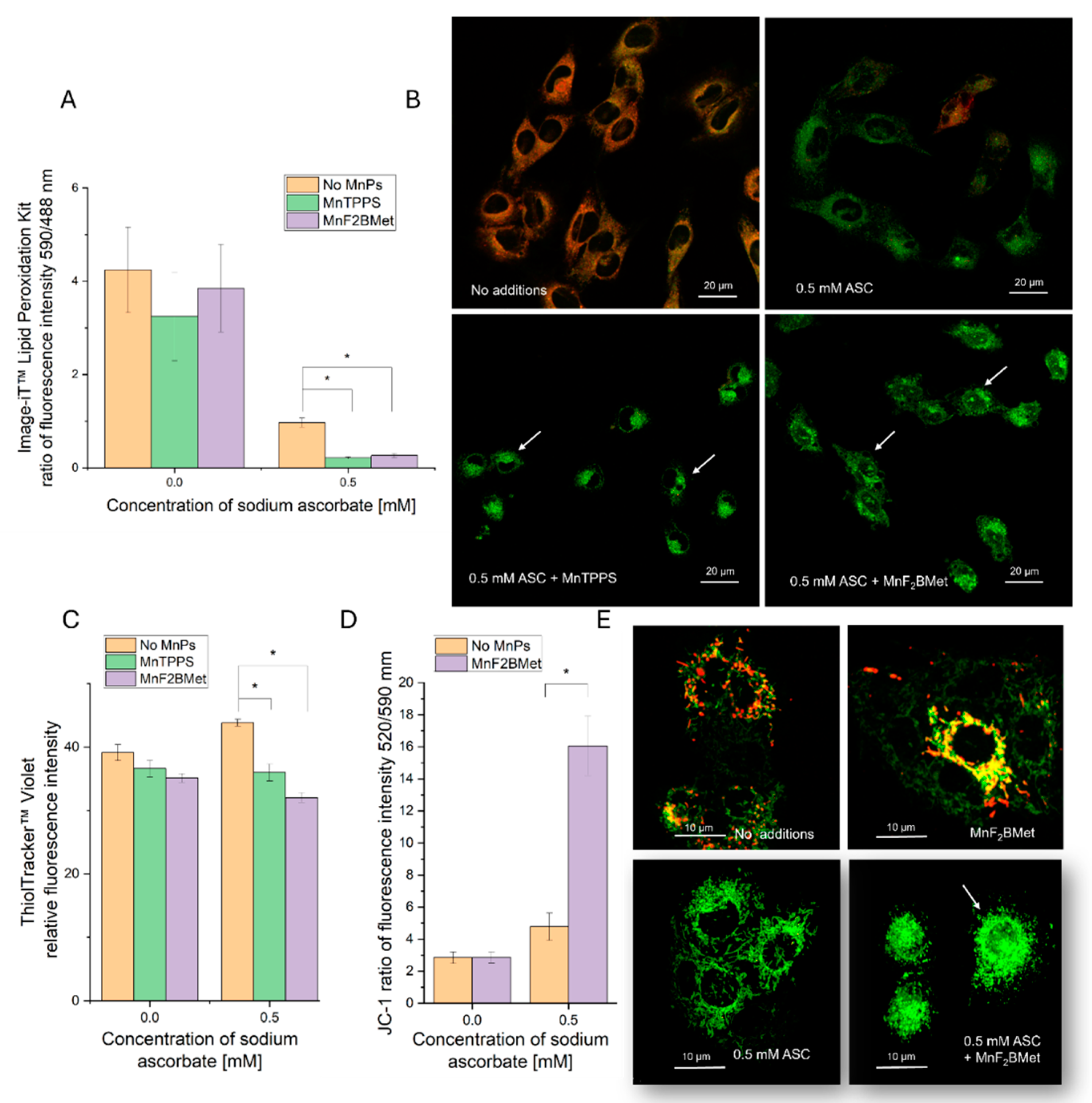

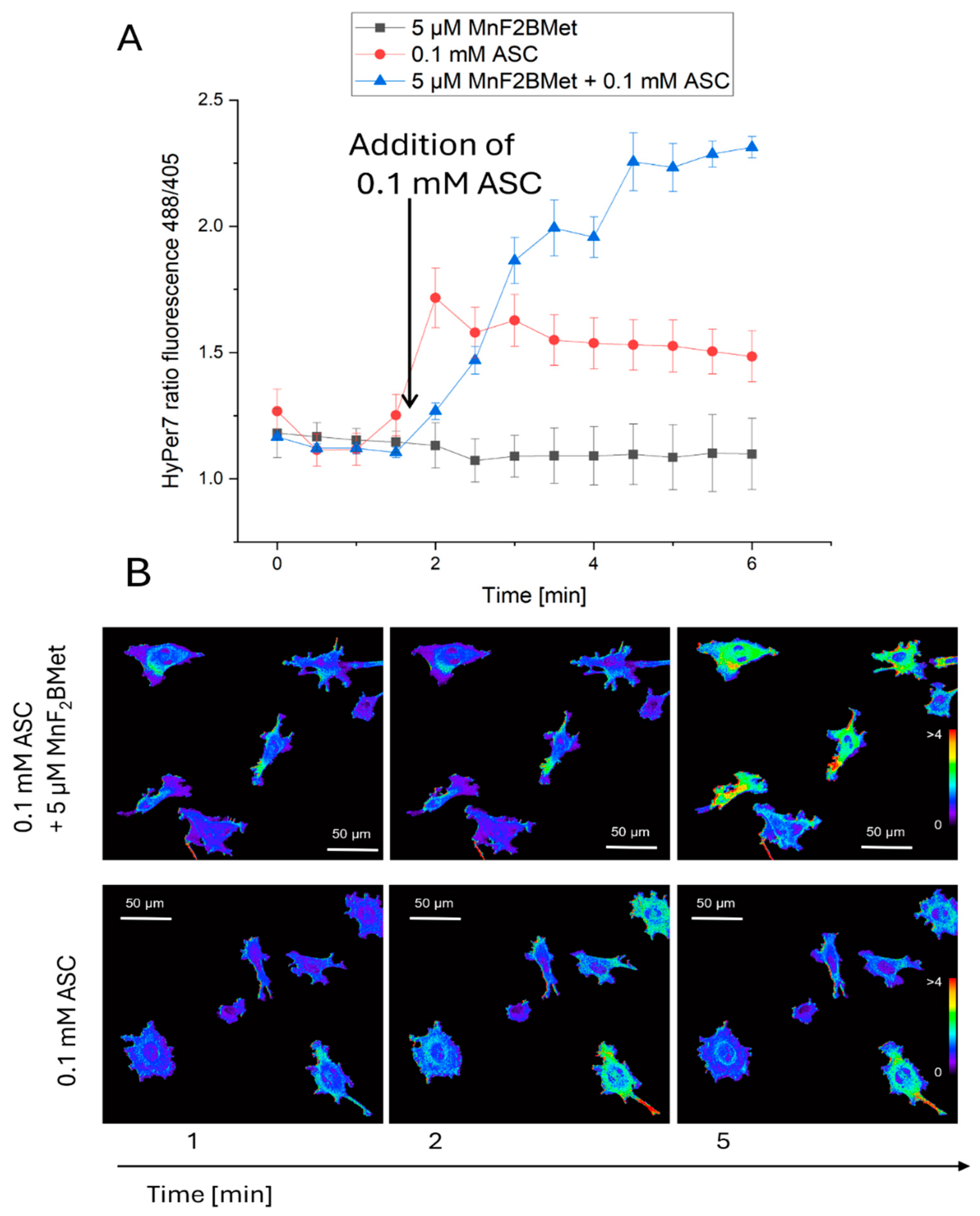

In our study, we directly quantified intracellular H

2O

2 levels using the HyPer7 fluorescent probe, providing clear evidence that H

2O

2 is the key mediator of MnPs-ASC-induced oxidative stress in MCF-7 cells. This method allowed us to demonstrate that MnPs-ASC treatment leads to sustained intracellular H

2O

2 elevation, correlating with increased lipid peroxidation, mitochondrial membrane depolarization, and ultimately cell death. The trypan blue exclusion test and (PI) uptake are complementary assays that indicate the loss of cell membrane integrity but are not capable of detecting cells in the early stages of apoptosis. On the other hand, the PI-uptake kinetics are consistent with rapid membrane integrity loss; however, definitive discrimination between necrosis and apoptosis would require dedicated markers [

21,

42,

43]. Our results support extracellular H

2O

2 as a main contributor to MnP–ascorbate cytotoxicity under our conditions. Extracellular catalase completely abolished MnPs-ASC cytotoxic effects, confirming that H

2O

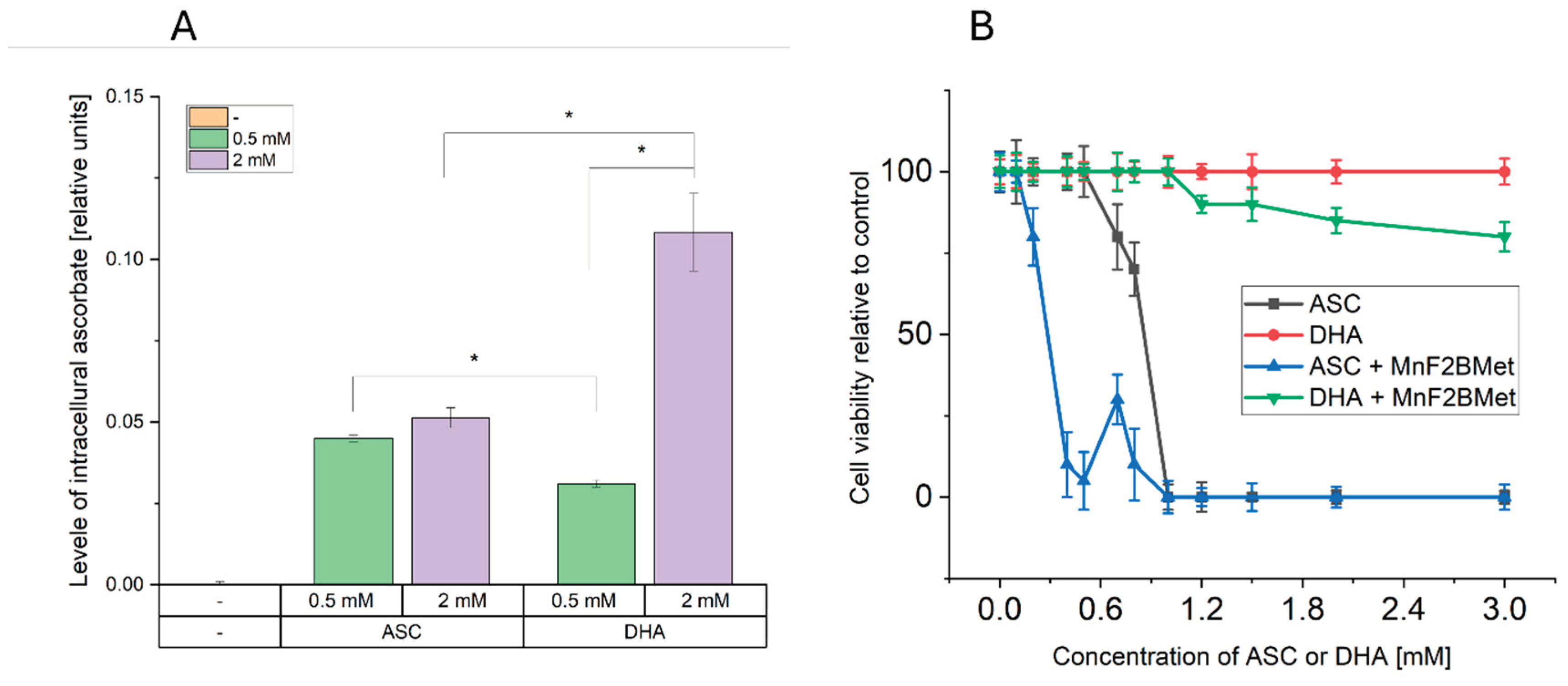

2 is generated outside the cells and must diffuse intracellularly to exert its effects. DHA supplementation (which enters cells and is reduced to ASC intracellularly) failed to induce significant cytotoxicity, even though it increased intracellular ASC levels. This strongly suggests that intracellular ASC alone is insufficient to drive MnPs-mediated ROS production and cell death. Washing the MnPs prior to ascorbate addition did not alter cytotoxicity. Although this observation suggests an intracellular mechanism, alternative explanations—such as residual surface-associated compound or incomplete washout—cannot be excluded.

Collectively, these findings confirm the role of extracellular interactions between manganese porphyrins and ascorbate in H

2O

2 formation at or near the cell surface. A similar mechanism has been described in the degradation of hyaluronic acid, which depends on MnPs-ASC interactions in the extracellular milieu [

37]. Based on these observations, we propose a mechanistic model in which i) MnPs accumulate on the cancer cell surface, possibly through electrostatic interactions with extracellular proteins or altered glycocalyx structures; ii) in the presence of ASC, MnPs catalyze the extracellular accumulation of H

2O

2 and its diffusion into the cells iii) locally accumulated ROS lead to cell membrane damage, whereas intracellular H

2O

2 overwhelms antioxidant defenses (GSH depletion), induces lipid peroxidation, and disrupts mitochondrial function, leading to iv) irreversible damages and necrotic cell death. These findings support an extracellular ROS-linked mechanism of cancer cell death and motivate further studies to define conditions under which such redox modulation could be therapeutically leveraged.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Michał Rąpała, Janusz Dąbrowski and Zbigniew Madeja; Methodology, Michał Rąpała and Maciej Pudełek; Software, Sławomir Lasota; Validation, Michał Rąpała and Maciej Pudełek; Formal analysis, Sławomir Lasota; Investigation, Michał Rąpała and Maciej Pudełek; Resources, Michał Rąpała and Maciej Pudełek; Data curation, Sławomir Lasota; Writing – original draft, Michał Rąpała and Zbigniew Madeja; Writing – review & editing, Michał Rąpała, Jarosław Czyż, Janusz Dąbrowski and Zbigniew Madeja; Visualization, Michał Rąpała and Sławomir Lasota; Supervision, Zbigniew Madeja; Project administration, Michał Rąpała and Zbigniew Madeja; Funding acquisition, Michał Rąpała, Janusz Dąbrowski and Zbigniew Madeja.

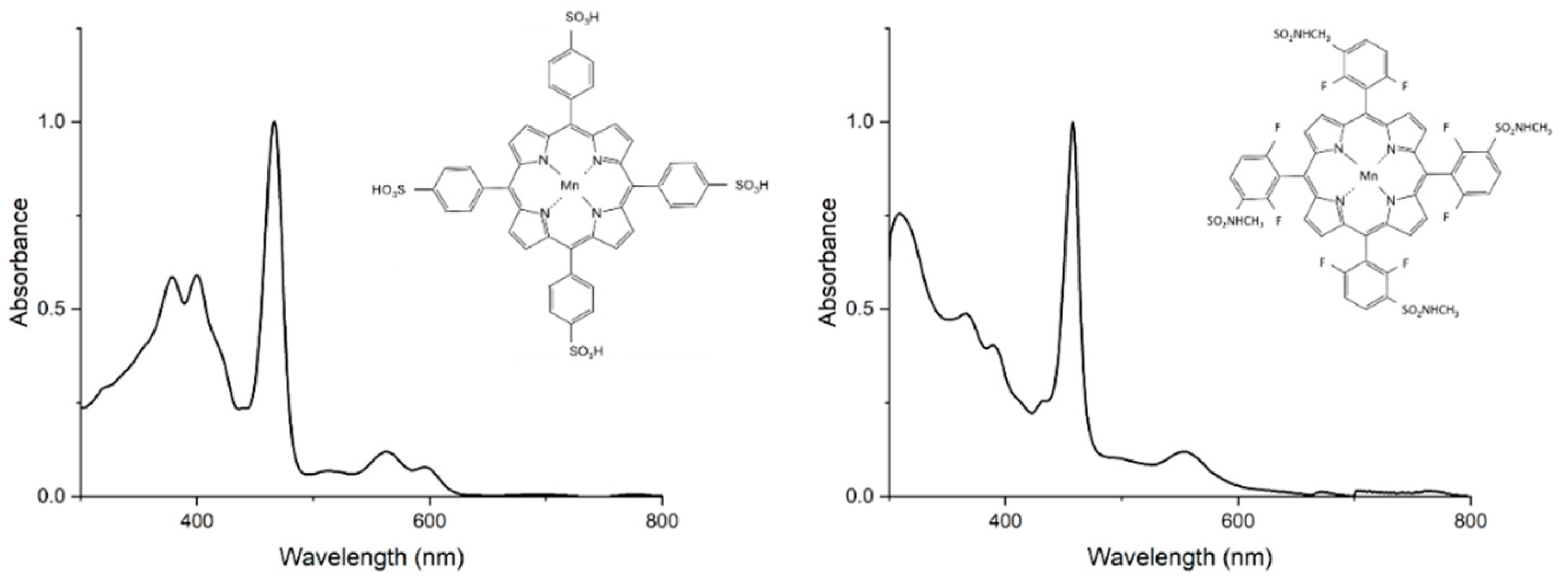

Figure 1.

Chemical structures and electronic absorption spectra of 5,10,15,20-Tetrakis(4-sulfonylphenyl)porphyrin manganese(III) acetate (MnTPPS) and 5,10,15,20-Tetrakis [2,6-difluoro-5(N-methylsulfamoyl)phenyl]porphyrin manganese(III) (MnF2BMet) recorded in PBS or PBS with 0.5 % DMSO at room temperature.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures and electronic absorption spectra of 5,10,15,20-Tetrakis(4-sulfonylphenyl)porphyrin manganese(III) acetate (MnTPPS) and 5,10,15,20-Tetrakis [2,6-difluoro-5(N-methylsulfamoyl)phenyl]porphyrin manganese(III) (MnF2BMet) recorded in PBS or PBS with 0.5 % DMSO at room temperature.

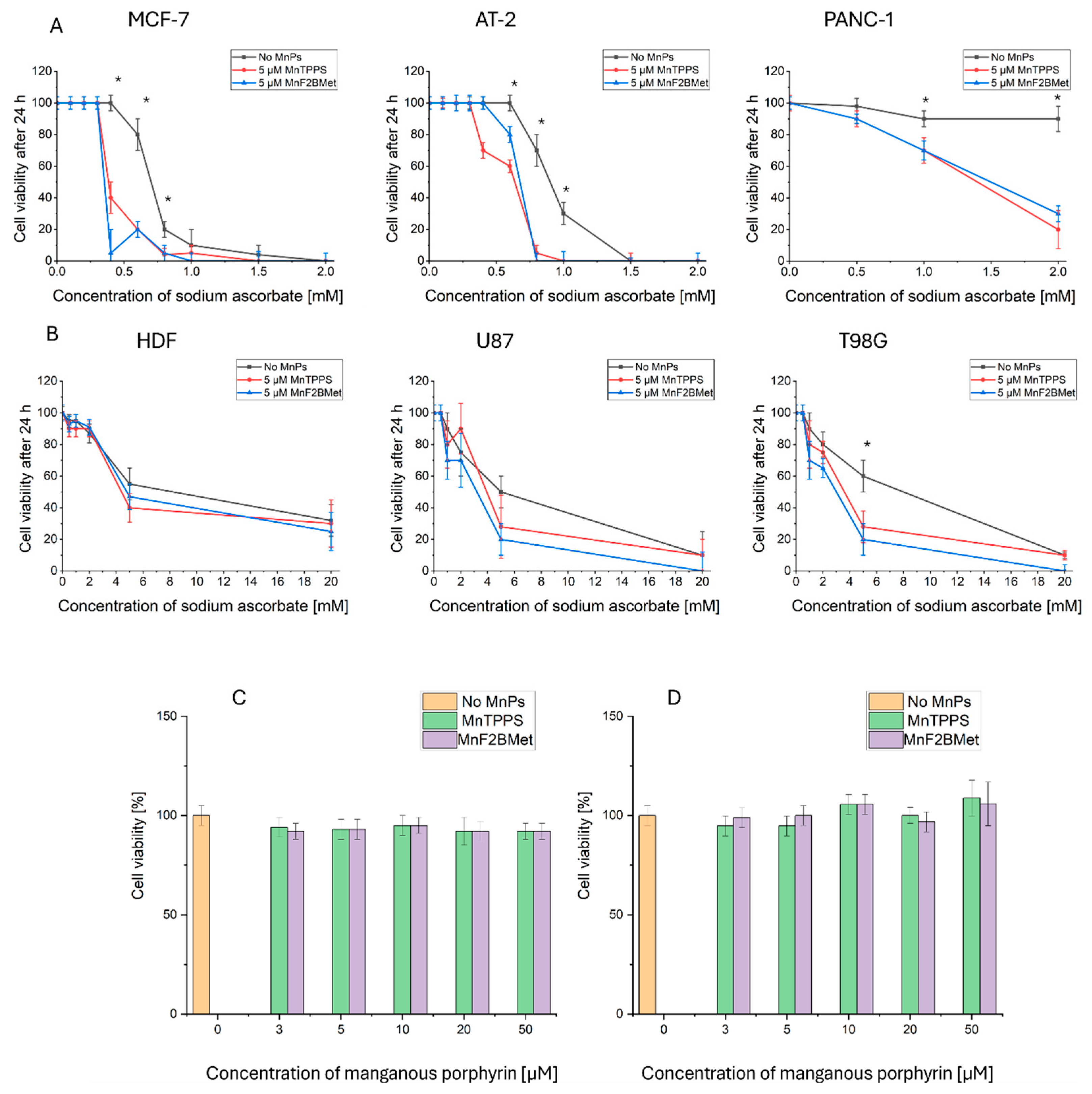

Figure 2.

(A) Viability of PANC-1, AT-2, and MCF-7 cells assessed using the trypan blue exclusion assay following treatment with 5 μM MnTPPS or 5 μM MnF2BMet in the presence of ASC at concentrations ranging from 0 to 2 mM, measured after 24 hours. (B) Viability of HDF, U87, and T98G cells determined using the trypan blue exclusion assay after treatment with 5 μM MnTPPS or 5 μM MnF2BMet in the presence of high concentrations of ASC (0–20 mM), measured after 24 hours. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, with viable cells expressed as a percentage of the total cell population, n = 3, (* p < 0.05) Statistical significance relative to the control without MnPs. (C) Viability of AT-2 cells and (D) viability of T98G cells, assessed using the trypan blue exclusion assay following treatment with MnTPPS or MnF2BMet over a concentration range of 0 to 50 µM, measured after 24 hours. Data are normalized to a DMSO control (0–1%) and presented as mean ± SEM, with viable cells expressed as a percentage of the total cell population.

Figure 2.

(A) Viability of PANC-1, AT-2, and MCF-7 cells assessed using the trypan blue exclusion assay following treatment with 5 μM MnTPPS or 5 μM MnF2BMet in the presence of ASC at concentrations ranging from 0 to 2 mM, measured after 24 hours. (B) Viability of HDF, U87, and T98G cells determined using the trypan blue exclusion assay after treatment with 5 μM MnTPPS or 5 μM MnF2BMet in the presence of high concentrations of ASC (0–20 mM), measured after 24 hours. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, with viable cells expressed as a percentage of the total cell population, n = 3, (* p < 0.05) Statistical significance relative to the control without MnPs. (C) Viability of AT-2 cells and (D) viability of T98G cells, assessed using the trypan blue exclusion assay following treatment with MnTPPS or MnF2BMet over a concentration range of 0 to 50 µM, measured after 24 hours. Data are normalized to a DMSO control (0–1%) and presented as mean ± SEM, with viable cells expressed as a percentage of the total cell population.

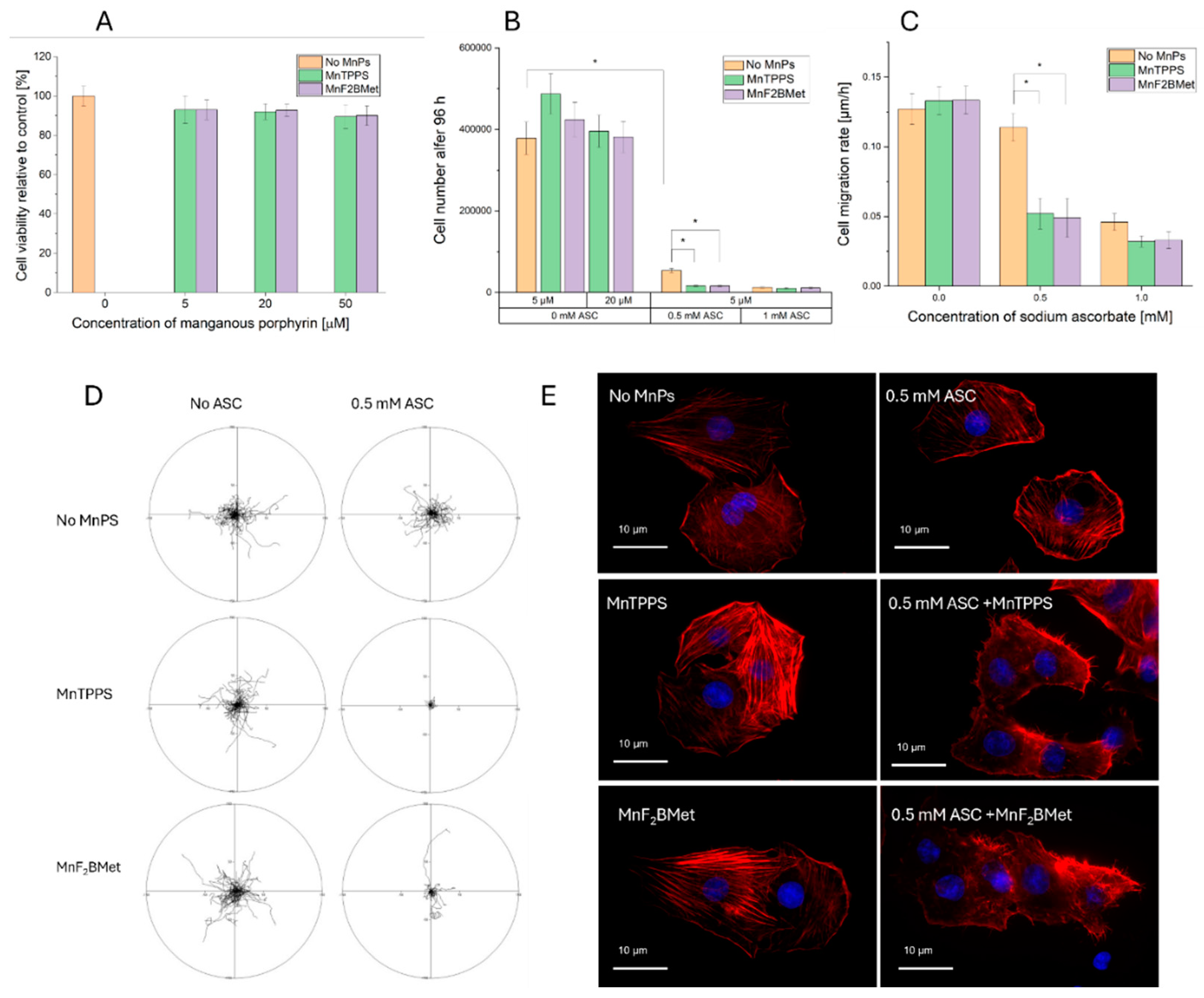

Figure 3.

(A) Viability of MCF-7 cells, assessed using the trypan blue exclusion assay, following treatment with MnTPPS (5, 20 or 50 μM) or MnF2BMet (5, 20 or 50 μM) for 24 hours. Data represent mean ± SEM of viable cells as a percentage of total cells n = 3. (B) Cell count measured 96 hours after treatment with 0.5 or 1 mM ASC, in the presence of either 5 or 20 μM MnTPPS or MnF2BMet. Data represent mean ± SEM, n = 3, * p < 0.05. (C) Cell migration rate of ASC-treated MCF-7 cells, assessed after ASC exposure. Data represent mean ± SEM of analyzed cells, n = 60, (p < 0.05). (D) Cell movement trajectories, determined over an 8-hour time-lapse experiment. (E) Cell morphology, visualized after the treatment with 0.5 mM ASC for 6 hours, with or without preloading with 5 μM MnTPPS. Red – F-actin, Blue – DNA.

Figure 3.

(A) Viability of MCF-7 cells, assessed using the trypan blue exclusion assay, following treatment with MnTPPS (5, 20 or 50 μM) or MnF2BMet (5, 20 or 50 μM) for 24 hours. Data represent mean ± SEM of viable cells as a percentage of total cells n = 3. (B) Cell count measured 96 hours after treatment with 0.5 or 1 mM ASC, in the presence of either 5 or 20 μM MnTPPS or MnF2BMet. Data represent mean ± SEM, n = 3, * p < 0.05. (C) Cell migration rate of ASC-treated MCF-7 cells, assessed after ASC exposure. Data represent mean ± SEM of analyzed cells, n = 60, (p < 0.05). (D) Cell movement trajectories, determined over an 8-hour time-lapse experiment. (E) Cell morphology, visualized after the treatment with 0.5 mM ASC for 6 hours, with or without preloading with 5 μM MnTPPS. Red – F-actin, Blue – DNA.

Figure 4.

Time-dependent propidium iodide (PI) uptake following ASC administration. PI uptake was monitored as an indicator of loss of membrane integrity in MCF-7 cells preloaded with 5 µM MnTPPS or 5 µM MnF2BMet and subsequently treated with 0.5 mM ASC (A) or 1 mM ASC (B). In the absence of MnPs, PI uptake was detected 4 hours post-treatment with 1 mM ASC. However, the presence of manganese porphyrins significantly accelerated this process, leading to detectable PI uptake within 2.5 hours after ASC administration. Decrease of fluorescence intensity after about 6 h of imaging is related to cell detachment. Microscopic images of MCF-7 cells captured at 1, 3, and 5 hours after treatment with 0.5 mM ASC (C) or 1 mM ASC (D) illustrate the progressive loss of membrane integrity. Images are composites of integrated modulation contrast (IMC) microscopy and the red fluorescence channel, highlighting PI-positive cells undergoing membrane permeabilization.

Figure 4.

Time-dependent propidium iodide (PI) uptake following ASC administration. PI uptake was monitored as an indicator of loss of membrane integrity in MCF-7 cells preloaded with 5 µM MnTPPS or 5 µM MnF2BMet and subsequently treated with 0.5 mM ASC (A) or 1 mM ASC (B). In the absence of MnPs, PI uptake was detected 4 hours post-treatment with 1 mM ASC. However, the presence of manganese porphyrins significantly accelerated this process, leading to detectable PI uptake within 2.5 hours after ASC administration. Decrease of fluorescence intensity after about 6 h of imaging is related to cell detachment. Microscopic images of MCF-7 cells captured at 1, 3, and 5 hours after treatment with 0.5 mM ASC (C) or 1 mM ASC (D) illustrate the progressive loss of membrane integrity. Images are composites of integrated modulation contrast (IMC) microscopy and the red fluorescence channel, highlighting PI-positive cells undergoing membrane permeabilization.

Figure 5.

Manganese porphyrins combined with ASC induce oxidative cellular damage. (A) Lipid peroxidation in MCF-7 cells, assessed 2 hours after ASC administration using the Image-iT™ Lipid Peroxidation Kit. (B) Representative fluorescence images show merged channels (red – no peroxidation, green - peroxidase lipid) with arrows indicating morphological changes associated with oxidative stress. (C) Intracellular glutathione (GSH) levels, measured 2 hours after exposure to 0.5 mM ASC in MCF-7 cells preloaded with 5 µM MnTPPS or 5 µM MnF2BMet, using ThiolTracker™ Violet assay and fluorescence microscopy. (D) Mitochondrial membrane potential, assessed using the JC-1 assay. MCF-7 cell loaded with 5 µM MnF2BMet and treated 0.5 mM ASC. (E) Representative fluorescence images highlight mitochondrial morphology alterations, with arrows indicating regions of structural disruption (red - High potential of mitochondrial membrane, green - low potential of mitochondrial membrane). Data represent mean ± SEM (n = 50, *p < 0.05).

Figure 5.

Manganese porphyrins combined with ASC induce oxidative cellular damage. (A) Lipid peroxidation in MCF-7 cells, assessed 2 hours after ASC administration using the Image-iT™ Lipid Peroxidation Kit. (B) Representative fluorescence images show merged channels (red – no peroxidation, green - peroxidase lipid) with arrows indicating morphological changes associated with oxidative stress. (C) Intracellular glutathione (GSH) levels, measured 2 hours after exposure to 0.5 mM ASC in MCF-7 cells preloaded with 5 µM MnTPPS or 5 µM MnF2BMet, using ThiolTracker™ Violet assay and fluorescence microscopy. (D) Mitochondrial membrane potential, assessed using the JC-1 assay. MCF-7 cell loaded with 5 µM MnF2BMet and treated 0.5 mM ASC. (E) Representative fluorescence images highlight mitochondrial morphology alterations, with arrows indicating regions of structural disruption (red - High potential of mitochondrial membrane, green - low potential of mitochondrial membrane). Data represent mean ± SEM (n = 50, *p < 0.05).

Figure 6.

Detection of intracellular hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) using the HyPer7 biosensor. (A) MCF-7 cells preloaded with 5 µM MnF2BMet were illuminated every 30 seconds with 405 nm and 488 nm lasers over the course of a 6-minute experiment to establish a baseline fluorescence level and confirm that MnF2BMet does not generate intracellular H2O2 upon light exposure. ASC was added after 90 seconds. In the absence of MnPs, the addition of 0.1 mM ASC caused a rapid increase in H2O2 levels, followed by a gradual decline in fluorescence intensity. In contrast, when 0.1 mM ASC was added to cells preloaded with 5 µM MnF2BMet, the increase in H2O2 levels was slower but reached a maximum, that was 2.5 times higher than in ASC-treated cells without MnPs. Data represent mean ± SEM, n = 30. (B) Fluorescence microscopy images of MCF-7 cells captured at 1, 2, and 5 minutes live cell imaging, either in the presence of 5 µM MnF2BMet or in MnPs-free control cells. ASC was introduced between the 1st and 2nd minute of live-cell imaging. The images represent ratiometric data, with the fluorescence signal excited at 488 nm divided by the signal excited at 405 nm. The pseudocolor scale reflects ratio fluorescence.

Figure 6.

Detection of intracellular hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) using the HyPer7 biosensor. (A) MCF-7 cells preloaded with 5 µM MnF2BMet were illuminated every 30 seconds with 405 nm and 488 nm lasers over the course of a 6-minute experiment to establish a baseline fluorescence level and confirm that MnF2BMet does not generate intracellular H2O2 upon light exposure. ASC was added after 90 seconds. In the absence of MnPs, the addition of 0.1 mM ASC caused a rapid increase in H2O2 levels, followed by a gradual decline in fluorescence intensity. In contrast, when 0.1 mM ASC was added to cells preloaded with 5 µM MnF2BMet, the increase in H2O2 levels was slower but reached a maximum, that was 2.5 times higher than in ASC-treated cells without MnPs. Data represent mean ± SEM, n = 30. (B) Fluorescence microscopy images of MCF-7 cells captured at 1, 2, and 5 minutes live cell imaging, either in the presence of 5 µM MnF2BMet or in MnPs-free control cells. ASC was introduced between the 1st and 2nd minute of live-cell imaging. The images represent ratiometric data, with the fluorescence signal excited at 488 nm divided by the signal excited at 405 nm. The pseudocolor scale reflects ratio fluorescence.

Figure 7.

MCF-7 cell viability following MnPs-ASC treatment and the effect of extracellular catalase. Viability of MCF-7 cells was assessed using the trypan blue exclusion assay after 24 hours of treatment with 5 µM MnTPPS or 5 µM MnF2BMet in the presence of ASC (0.6, 1, and 2 mM). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, (*p < 0.05) with viable cells presented as a percentage of the total cell population.

Figure 7.

MCF-7 cell viability following MnPs-ASC treatment and the effect of extracellular catalase. Viability of MCF-7 cells was assessed using the trypan blue exclusion assay after 24 hours of treatment with 5 µM MnTPPS or 5 µM MnF2BMet in the presence of ASC (0.6, 1, and 2 mM). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, (*p < 0.05) with viable cells presented as a percentage of the total cell population.

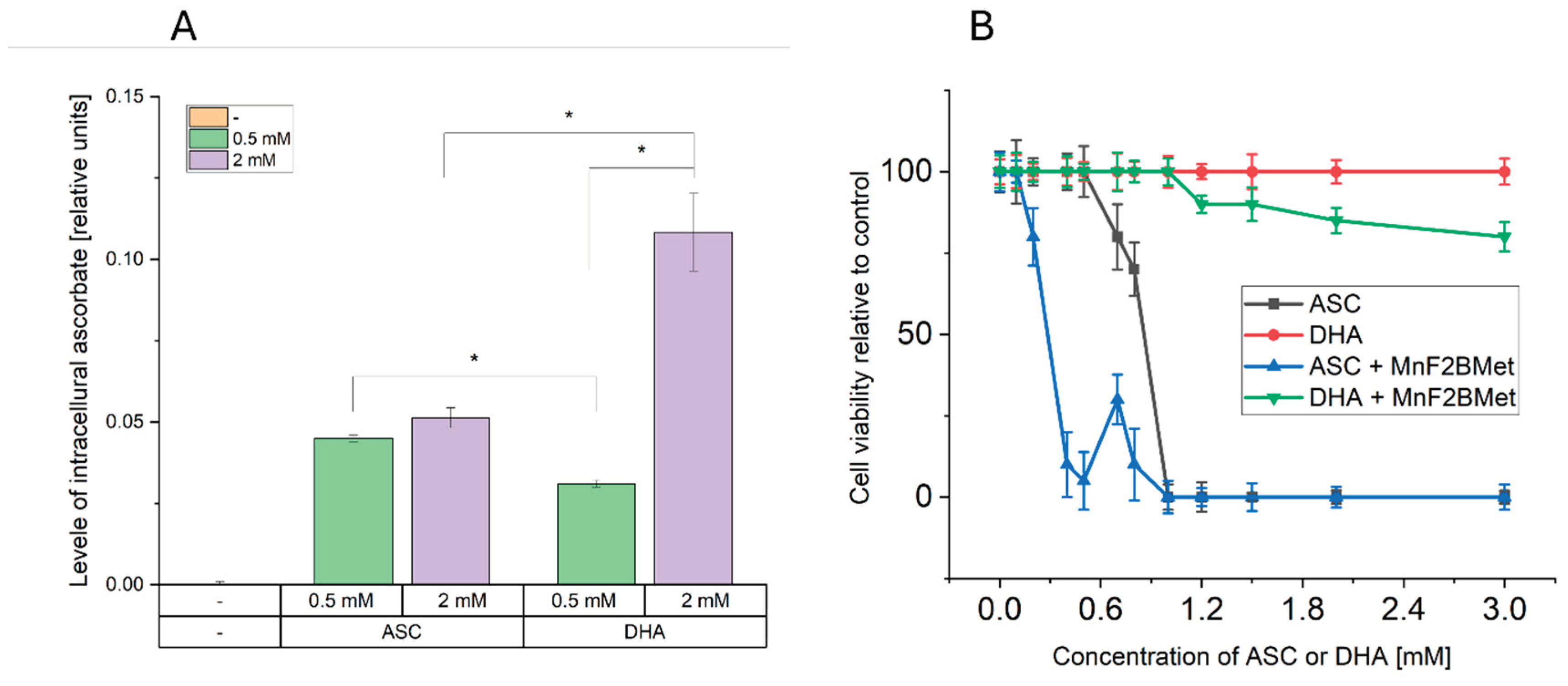

Figure 8.

Dehydroascorbic acid (DHA) enhances intracellular ASC levels but exhibits limited cytotoxicity in MCF-7 cells. (A) Intracellular ASC levels following the administration of 0.5 or 2 mM ASC or 0.5 or 2 mM DHA in MCF-7 cells. While 0.5 and 2 mM ASC resulted in a similar increase in intracellular ASC levels, 0.5 mM DHA was less effective in delivering ASC to cancer cells compared to its reduced form. The most efficient method for increasing intracellular ASC levels was the administration of 2 mM DHA, indicating a concentration-dependent effect. (B) Cytotoxic effects of ASC and DHA on MCF-7 cells. Unlike ASC, DHA alone did not exhibit cytotoxic properties in MCF-7 cells. However, the presence of 5 µM MnF2BMet led to a moderate decrease in cell viability (~80%) after 24 hours of DHA treatment. In contrast, under the same conditions, ASC treatment alone and ASC combined with 5 µM MnF2BMet resulted in a significant reduction in cell viability, further supporting the role of ASC in MnPs-induced cytotoxicity.

Figure 8.

Dehydroascorbic acid (DHA) enhances intracellular ASC levels but exhibits limited cytotoxicity in MCF-7 cells. (A) Intracellular ASC levels following the administration of 0.5 or 2 mM ASC or 0.5 or 2 mM DHA in MCF-7 cells. While 0.5 and 2 mM ASC resulted in a similar increase in intracellular ASC levels, 0.5 mM DHA was less effective in delivering ASC to cancer cells compared to its reduced form. The most efficient method for increasing intracellular ASC levels was the administration of 2 mM DHA, indicating a concentration-dependent effect. (B) Cytotoxic effects of ASC and DHA on MCF-7 cells. Unlike ASC, DHA alone did not exhibit cytotoxic properties in MCF-7 cells. However, the presence of 5 µM MnF2BMet led to a moderate decrease in cell viability (~80%) after 24 hours of DHA treatment. In contrast, under the same conditions, ASC treatment alone and ASC combined with 5 µM MnF2BMet resulted in a significant reduction in cell viability, further supporting the role of ASC in MnPs-induced cytotoxicity.