1. Introduction

The equilibrium description of the quantum monatomic fluid structures at the pair level

in the diffraction and Bose-Einstein regimes, can be achieved using Feynman’s path integrals (PI) [

1,

2] combined with computer simulation methods, i.e., path integral Monte Carlo (PIMC) and path integral molecular dynamics (PIMD) [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. (The Fermi-Dirac regime is out of the conventional PI practical applications and requires a special PI formulation [

15,

16]; see below). The usual PI framework is directly expressed in the coordinate representation and its success at the pair level prompts the interest in undertaking the study of the quantum triplet-structural level

[

17,

18,

19]. Although fluid triplet structures in general cannot be obtained via radiation scattering experiments today [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24], the equilibrium structures in statistical mechanics behave in a hierarchical manner [

25,

26,

27,

28] and the triplet step forward in the quantum domain is needed. This task implies the numerical determination of an involved variety of structural functions, i.e.,

correlation functions in real space (

r-space) and

structure factors in the reciprocal Fourier space (

k-space) [

19,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. The different nature of these functions depends on the external field

applied that makes them show up.

As a matter of fact, the triplet-structural task for monatomic fluids may be regarded as already accomplished in the classical domain [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59], where computer simulation methods (Monte Carlo (MC) and molecular dynamics (MD) [

41,

45,

46,

48,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

57]) and theories based on integral equations and closures [

17,

20,

25,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

49,

50,

52,

53,

55,

57,

58] have been utilized. (Closures are cost-effective theoretical approaches that try, in general, to infer

n-level structures from the knowledge of the lower-level

structures;

and

denote the elemental number of particles involved). Given that PI computer simulations can be regarded as appropriate “translations” of their classical counterparts [

4,

5,

9], the parallel experience accumulated in the classical domain is a precious asset to tackling the quantum triplet-structural challenge. The same can be said of closures, which were used to deal with classical and quantum structures alike, regardless of their original motivations and derivations [

17,

20,

25,

36,

60,

61]. Nevertheless, the complexities of the quantum domain have led to consider some special features that escape the classical analogies [

19].

Therefore, the quantum fluid triplet program to be followed not only shares the same general reasons that guided the corresponding classical developments, but also must include the new aspects arising from the distinct quantum behaviors. Among the general reasons, one may mention the following: statistical thermodynamics questions beyond the usual pairwise approach, the characterization of the freezing transition, the understanding of the selection between crystal lattice sites, the discussion of glass-forming liquid properties, multiple scattering phenomena, and the calculations of transport coefficients and time-dependent properties (e.g., the dynamic structure factor). Among the new aspects, which in a sense extend the scope of the latter reasons, one may mention the following quantum problems [

6,

9,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

62,

63,

64]: the variety of the distinct fluid responses to external fields, the effect of quantum fluctuations on the formations of crystals and glasses, the role of phonon-phonon interactions in superfluid systems, and the fixing of spin-resolved fluid structures. In connection with these problems, from the scarce initial results on quantum fluid triplets obtained so far, one observes intriguing behaviors of order parameters on the crystallization lines of liquid para-H

2 [

33] and the hard-sphere fluid [

34]. In addition, triplet closures have been proven to capture more quantum traits than expected and their usefulness deserves further investigation [

19,

34,

35].

Now, some comments on the difficulties that one encounters when tackling quantum fluid triplets are in order. In the classical and the quantum domains, the dimensionality of the triplet structural functions for a homogeneous and isotropic monatomic fluid is 4-D, with conceptual and computational reasons increasing the complications in the quantum case. The simplest thermal quantum behavior is that of the diffraction effects (i.e., interference phenomena among delocalized atoms, whose magnitude cannot be disregarded); this behavior ignores any possible spin feature of the indistinguishable atoms (or the model one-site particles) composing the fluid. Such diffraction behavior can be observed in every system subjected to low-temperature conditions, but the applied temperatures are to be sufficiently high as to make the spin features negligible [

1,

2,

4,

9,

12,

13,

14]. The spin features become fundamental at very low temperatures and add further intricacies to the fluid descriptions: (a) for integer spin atoms, one faces Bose-Einstein exchange statistics (BE) [

2,

9,

10,

11,

65]; and (b) for half-odd-integer spin atoms, one faces Fermi-Dirac exchange statistics (FD) [

2,

15,

16,

65]. Typical examples of monatomic systems that can show these exchange regimes are liquid

4He (zero-spin atoms, BE) and liquid

3He (one-half spin atoms, FD), for which diffraction effects dominate their behaviors so long as the temperatures are

and

respectively [

65]. Below these temperature limits the corresponding BE and FD behaviors cannot be neglected (

3He even enters the BE regime for

[

65].

Interestingly, and focusing on the structural questions, the diffraction and zero-spin BE regimes admit a common general framework in that, by paying attention to their distinct peculiarities, they can be dealt with by using PI in its conventional original form [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

19]. However, nonzero-spin cases require special PI developments; for BE statistics see Reference [

66], whereas for FD statistics see the recent works in References [

15,

16] that use Wigner’s formulation of quantum mechanics [

67,

68,

69] combined with PIMC simulations (WPIMC). (Note that, when studying FD conditions with PI, any proposed method must cope with the so-called “sign problem” [

15,

16,

70,

71,

72,

73]). Therefore, with the addition of WPIMC, the basic methods for computing monatomic fluid structures via PI have been put forward and are, in principle, applicable to the foregoing quantum regimes. However, although the problem of pair-level structures involves affordable PI computations, the current situation for triplet structures is not so nice, even in the thermal quantum diffraction regime. This work deals with this latter regime and the presentation concentrates on it hereafter.

The thermal quantum diffraction regime may be visualized through the well-known PI image of necklaces composed of beads for representing the actual quantum atoms/particles. Despite the many PI mathematical intricacies, this allows one to study the quantum fluid and its interactions with external fields in a very intuitive way [

4,

9,

12,

13,

14,

74,

75,

76]. Thus, for example, an actual fluid composed of

N atoms is represented, in the end, by a PI model consisting of

N necklaces with

P beads apiece (

is an integer that becomes greater with increasing quantum effects and is to be optimized); thus, there is a one-to-one correspondence between thermally quantum delocalized atoms and necklaces. Through various applications of linear response theory [

27,

28,

77], adapted to the treatment of the quantum domain [

14,

19,

32,

78,

79], three general classes of fluid structures can be identified and defined in terms of inter-bead/inter-necklace distances in real space. One finds the following classes: (a) centroid

abbreviated to CMn (a centroid is the “center of mass” of its necklace); (b) instantaneous

abbreviated to ETn; and (c) total thermalized-continuous linear response

abbreviated to TLRn. As seen, the basic pattern per

n-level is the same for every fluid class: one correlation structure

associated with real space plus one structure factor

associated with its corresponding reciprocal Fourier space. Each of the foregoing classes is related to the fluid response to a type of external weak field

; within a class, the connections among its functions are far from straightforward, since their formal complexity increases with the order

n [

19,

32]. A warning is in order here: for structural purposes, depending on the PI-scheme selected to carry out the fluid study, there may be beads that are not significant and must be disregarded; for generality, the number of structurally significant beads per necklace will be denoted by

X hereafter (in normal practice, one finds either

or

[

9,

12,

14,

76]. The centroid and instantaneous quantities are formulated in ways similar to that of the familiar classical domain [

26,

27,

28]; however, in the total thermalized-continuous linear response case, one faces more entangled formulations [

14,

19,

32].

Furthermore, it is worth remarking that radiation scattering experiments allow one to obtain the pair-level ET2 and TLR2 structures [

21,

22,

23,

24]; these structures are defined by the actual atoms composing the sample, because atoms interact effectively with the external field. However, given that the (small) intensity of the triplet contribution is hidden in the whole intensity of the outgoing signal [

20], no structural function can be experimentally determined beyond

As for the centroid class CMn, although not even the pair CM2 structures can be directly obtained in any experiments (centroids cannot actually couple with any fields), its importance as an intermediate theoretical object cannot be overemphasized, as its usefulness is astonishing. In this regard, centroid structures do follow the same rules as those of a classical fluid [

19,

30,

78], and their applications cover from the exact connections with the fluid equation of state to order parameters for charactering quantum samples to appealing approximate formulations of quantum dynamics, and even to certain BE exchange questions [

6,

7,

12,

14,

19,

30,

78,

79,

80,

81,

82,

83,

84,

85,

86,

87,

88,

89,

90,

91,

92,

93,

94,

95].

The foregoing comments on the distinct quantum structural classes point to the greater complexity of the quantum studies as compared to the more reduced scope of their classical counterpart, where only one class of structures

abbreviated to Cn, exists. (Note that Cn can be extended further to incorporate, in a formally exact way, the

n-body direct correlation functions

[

37,

38,

40,

45]). Nevertheless, these theoretical reasons are just half the issue. The other half includes the practical causes behind the current scarcity of quantum triplet structure applications using “exact” path integral methodologies, and it is considered below.

PIMC computational studies on triplet structures in homogeneous and isotropic quantum monatomic fluids [

19,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35] have focused mostly on the equilateral and isosceles features of the instantaneous ET3 and the centroid CM3 structures. PI simulation work needs powerful computational resources and time-consuming runs; the results so obtained are “exact”, that is, with controllable statistical errors. Therefore, the desired accuracy of the numerical answers can be increased, but at the expense of more calculations. Such a fact has its ramifications. In this connection, one must consider the PI sample size, which leads to the analysis of the expanded configurational space resulting from the introduction of the necklaces and their associated beads: for a system of

N actual quantum atoms, the dimensionality of the configuration space is

whereas for its PI model the corresponding dimensionality is

Moreover, the number of different quantum structural classes mentioned above magnify the task. Roughly speaking, one finds in PI work that: (a) centroid structure calculations scale with

N, as in their classical counterparts [

41,

48]; and (b) the instantaneous and the total thermalized-continuous linear response calculations, apart from the usual

N-dependence, also scale with

X and

respectively [

19,

29,

32]. Furthermore, aside from the 4-D character of the triplet functions, structure factors in simulation work are fixed via the scanning of appropriate sets of wave vectors, because the latter must: be commensurate with the basic box in which the sample is contained [

46], and target independently the three different classes of structures [

33]. Therefore, the quantum diffraction situation contrasts sharply with that of the classical monatomic fluid composed of

N atoms, where the configuration space has a dimensionality

and only one class of structures is to be targeted. Owing to these difficulties, in the quantum treatments of the classes CM3 and ET3, the introduction of closures and direct correlation functions

[

17,

25,

38,

45,

47] can be expected to play a significant role [

19,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. However, although these mathematical tools augment the reach of the conceptual framework and are intended to diminish the computational overload, their quantum applications are not free from uncertainties [

19,

45], as happens (to a lower extent) in the classical domain.

The aim of this work is to continue the study of fluid triplet structures in the thermal quantum diffraction regime. Two systems that were analyzed by this author in pilot investigations are selected: helium-3 under supercritical conditions [

19,

35,

96], and the quantum hard-sphere fluid (QHS) on its crystallization line [

19,

34,

97]. PIMC simulations are performed for both systems in the canonical ensemble. The PI propagators selected are: (a) for helium-3, the fourth-order propagator in Voth et al’s form [

12] (SCVJ, based on the Suzuki-Chin’s developments [

98,

99]), its application involving the use of Janzen-Aziz’s SAPT2 interatomic potential [

100]; and (b) for QHS, Cao-Berne’s pair action [

76]. Also, complementary closure calculations are reported; the following closures are utilized: Jackson-Feenberg convolution [

17], Kirkwood superposition [

25], the intermediate closure AV3 [

34], and Denton-Ashcroft approximation in symmetrized form [

47]. Obviously, exhaustiveness in this study is not attempted since, for the time being, the computational load involved would be immense. Rather, the current work adds up to the knowledge of these two systems by exploring quantum triplet properties under very different fluid conditions: far and near the first-order fluid-solid transition. The results focus on salient triplet features (equilateral and isosceles) of the centroid and instantaneous structures, by covering spatial correlations in helium-3, and structure factors in helium-3 and QHS. Path integral and closure results are compared, and a number of further procedural and structural conclusions are drawn.

The outline of this article is as follows.

Section 2 contains the basic PI theory.

Section 3 describes the PI triplet centroid and instantaneous structural concepts.

Section 4 focuses on the triplet closures utilized in this work.

Section 5 gives the computational details, and

Section 6 the results and their discussion. Finally,

Section 7 collates a number of closing remarks and perspectives for future work.

2. Path Integral Background

In the study of quantum monatomic fluids, one utilizes the usual statistical ensembles [

1,

2,

26,

27,

28]. For constraints defining a closed system there are the canonical

and the isothermal-isobaric

ensembles, while for constraints defining an open system there is the grand canonical ensemble

. The variables, whose values are held fixed in each case, are the number of particles

N, the volume

, the temperature

T, the pressure

, and the chemical potential

. Within the conventional statistical mechanical treatments, the atoms composing the system under study are considered structureless particles, their spatial positions in the system being defined by those of their nuclei

The latter reduction is consistent with the experimental techniques that reveal the actual existence of fluid structures [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

27], and it implies that the electronic degrees of freedom have undergone a quantum mechanical averaging process for setting an adequate potential energy interaction function

(non-collapsing and tempered [

28]). Such an operation is rooted in the Born-Oppenheimer approximation [

101]. In the absence of any external field

the whole situation for a quantum system is contained essentially in the canonical density matrix given by the operator

[

2,

4,

9,

28].

stands for the isolated system Hamiltonian, which is built as

where one includes the operators for the kinetic energy,

and the potential energy,

Once the form of

is fixed, the canonical partition function

arises as the trace of the density matrix,

[

2,

26,

28], which allows one to set the basic thermodynamic connection

where

A stands for Helmholtz free energy. The definitions of the partition functions for the isothermal-isobaric or the grand canonical ensembles are straightforward using

[

26,

27]. Within this context, recall that there is a Wick rotation contained in the formal equivalence

), where

stands for a time-independent Hamiltonian and

for real time. The definition of an imaginary time as

follows from that equivalence [

1,

2], and

emerges as a thermal quantum variable for the characterization of equilibrium states. Furthermore, to give operational forms to the partition functions, one uses the PI approach and obtains their proper adaptations [

4,

8,

9,

11,

12,

76,

102,

103]. To introduce the basic concepts, attention will be given to the canonical ensemble questions in this Section.

2.1. PI Canonical Partition Function

When using the PI formalism [

2], every atom/nucleus

j is represented by an elastic path

in imaginary time

. The general form of the path-integral canonical partition function of a monatomic quantum fluid, e.g., composed of helium atoms, with all the atoms in the same spin state, can be written in the canonical ensemble as [

2]:

The symbol

runs over the

permutations among the

indistinguishable atoms,

is the sign of the permutation

(i.e., +1 for every boson permutation;

for fermion permutations that, depending on their parity, is

for even

or

for odd

). In Equation (1a), the integrations cover all the configuration space associated with the particle paths

, the symmetry constraints are denoted by the conditions at

and

which imply that the particle paths may interlink for

Identity in a large variety of ways. The exp-factor contains the action in imaginary time, where:

stands for the derivative with respect to

and

is the potential energy function acting at equal-

“instants”. Equivalently,

can also be cast in the coordinate representation as [

2,

4,

9]:

where

is the

dimensional volume element of the configurational space of the

actual atoms,

is the ket of position states

, and the permutations act on the particle position states as

At sufficiently high temperature, only the identity permutation contributes to effectively shape Equations (1), the BE or FD quantum statistics features can be neglected, and both exchange situations lead to the same general result in the form of “distinguishable” delocalized atoms (this is nicely illustrated by helium systems [

9,

96]). Such a situation is that of thermal quantum diffraction/dispersion effects, for which the PI canonical partition function reads as [

2,

4]:

where every atom

j is represented by an elastic closed path

in imaginary time, such that

In the coordinate representation, Equation (2a) reads as follows [

4,

9]:

In Equations (2), although only the identity permutation is retained and the atoms can be “numbered”, the presence of

as the remaining factor of the true indistinguishability among the atoms is to be noticed; the presence of

as a factor necessary to guarantee the correct dimensionality, is also to be noticed. (Both

and

are indispensable for the formulation of the classical partition function [

2]). In general, for many-body system studies, Equations (1b) and (2b) are the practical forms of the partition function that serve as starting points to develop the PI-discretized numerical approaches [

4,

9,

12,

76].

In this work, attention is focused on Equation (2b) and its connections with the incorporation of weak external fields

acting on the atoms/nuclei/particles of the quantum fluid. The fields define the three classes of equilibrium structures

in a fluid under quantum diffraction conditions, with linear response theory being instrumental in the corresponding derivations. In this context, the specific nature of the field and its interactions with the atoms/nuclei/particles are determinant, which contrasts with its classical counterpart [

19,

27,

32,

77,

78,

79].

In this connection, some cautionary remarks are to be made. The discussion in this Section considers the path-integral case involving weak continuous fields, which is a situation amenable to classical-like treatments and allows one to introduce most of the basic concepts. It so happens that the total thermalized-continuous linear response (TLRn) and centroid (CMn) classes are directly linked to the following developments [

14,

19,

32]. However, the instantaneous class (ETn) escapes such a direct treatment based on continuous fields, owing to the localizing fields involved in its definition. Despite the previous remark, Equation (2b) serves equally well the purposes of formulating the instantaneous structural functions at any

n-level, because the underlying arguments involved are also associated with linear response theory [

9,

19,

27]. The structural facts relevant to this work (CMn and ETn) are considered in the next Section.

2.2. The Action of Weak External Continuous Fields

In the presence of a weak external continuous field

acting as

the canonical partition function for diffraction effects can be cast in the coordinate representation as [

14]:

The operators

and

are assumed to be self-adjoint, having complete sets of eigenvectors and eigenvalues. (To generalize the right-hand side of Equation (2a) by including

the action integral should contain the term

. To obtain general operative forms, one applies to the density matrix operator the identity [

9]:

Next, one inserts in Equation (4)

spectral resolutions of the identity in the coordinate representation, i.e.,

, where

and

Then, by denoting

Equation (4) reads as:

Now, Equation (5), which is an exact expansion, needs explicit forms for the propagator

, where the cyclic property

is to be applied. In addition, for every atom

j, the latter property brings forth discretized closed trajectories:

. In the limit

any

) trajectory transforms into a closed continuous path

in imaginary time [

2,

9]. Therefore, any

) trajectory takes place in real space and evolves in imaginary time according to the “time”-step

(see further details below). The foregoing general propagator, defined in the coordinate representation, takes nonnegative values [

9], a decisive fact that guarantees the existence of probability densities in the related PI formulations. Note that the selection of the size of the imaginary time-step will influence the propagator form. Also, one must bear in mind that the kinetic energy operator

does not commute with the potential energy operators

and

hence,

does not commute with

either.

Given that the PI partition function in the associated configurational space is consistent with a proper statistical analysis, the set of PI elastic closed paths is equivalent to a statistical distribution of closed paths. Factors that affect such statistical distribution are: (a) the symmetry among the

N descriptions

of the particles, and (b) the packing of the particles and/or other parameters relevant for the system description [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

12,

13,

14]. In relation to this, the actual bulk density of a system is taken as the number density

(e.g., for

N particles in a fixed volume

the density is

).

The formulation of structures based on developments of Equation (5) is a delicate matter, and one should deal first with the questions involving

and

. One can proceed by applying the straightforward operator relationship [

14]:

which arises from the Baker-Campbell-Haussdorf formula for the exponential operator built as the sum of two non-commuting operators [

104]. Potential energy operators are diagonal in the coordinate representation, i.e.,

, a fact that leads to the PI-discretized approximation

for the canonical partition function [

14]:

where

implies the abovementioned cyclic property

for the

product. The foregoing partition function is accurate up to terms

. In the limit

, one retrieves the actual

since the operators

and

are self-adjoint and make sense separately, as required by Trotter’s analysis [

3,

9] (the same applies to

and

regarding questions that involve the isolated

operator [

9]). Given that the propagators contained in Equation (7) must be nonnegative everywhere in the configuration space corresponding to the set of variables

, it is easy to identify the underlying probability density of this formulation. Therefore, classical-like statistical developments and calculations involving

can be performed, and

represents a compromise between statistical convergence and theoretical accuracy (i.e.,

[

3], which means that

can be properly optimized for the problem under study. Remarkably, linear response theory utilizes the structural functions of the isolated-from-

fluid, that is, those functions derived from the consideration of

alone. Hence, questions on the accuracy of the structures obtained through the use of Equations (6) and (7), related to the number of “instants”

, are merely formal, because one can optimize

by analyzing just the isolated-from-

fluid structures.

2.3. Propagators for the PI Discretized Canonical Partition Function

At this point, it is convenient to discuss the options for the propagator

in the absence of

which will give final forms to

. For structural studies, there are three main types of propagators: primitive [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9], pair actions [

9,

76], and the fourth-order SCVJ [

12,

98,

99]. (See also another fourth-order propagator version in Reference [

105]). Two main interrelated facts take part in their derivations. First, there is the form in which the imaginary-time step is chosen. Thus, if

is divided into

equally-spaced intervals, with the step-unit set to

arbitrary integer

one will deal with the primitive or a pair action propagator. However, if a double step

is selected, making

be an even positive integer, i.e.,

one can deal with the SCVJ propagator. In the end, for practical and consistency reasons, the final number of intervals will be

P, regardless of the type of propagator selected, although the roles of the interval ends may not be equivalent in the final description achieved (e.g., the SCVJ case). Second, there are different choices to deal with the noncommutativity between

and

These choices are in the roots of the picture of

necklaces with

beads apiece for the discretized closed paths in imaginary time,

), of the particles: such

picture is common to the three types of propagators considered. In this connection, for a sufficiently large

the three propagators yield the same final description; thus, a critical issue in PI calculations is the distinct statistical convergence rates that, depending on the optimal

P, can be achieved with each type of propagator [

9,

12,

14,

76].

Although for specific details the reader is referred to the References quoted above, for the current purposes, it is worth stressing that the general form of

can be cast as [

9,

12,

14]:

where

or

and, for notational simplicity, two symbols to denote the beads,

t and

are employed. The relations between the bead sets

and

are explained below (the

elements coincide with choices extracted from the

set) [

14].

In Equation (8), the integrations cover the whole

-dimensional configurational space associated with the

closed necklaces,

each necklace is composed of

beads,

contains the specific connections/interactions among all the beads in the sample, thereby being an “effective potential” for the resulting classical-like set of

beads. Thus, one finds the so-called (semi) classical isomorphism [

4], in which the

form containing the bead interactions depends on the propagator selected and, also, on

and

While for the primitive and pair action propagators the situation is straightforward

the SCVJ derivation doubles necessarily the initial number

of instants,

by adding

intermediate instants to the initially closed

X-trajectory [

12]. Therefore, the complete SCVJ bead set is renumbered according to the total number of beads

and the odd-numbered ones are associated with the field-bead interactions, as stated in Equations (7) and (8). Linear response theory [

14,

77] uses such interactions in its derivations and, therefore, one can anticipate that the significant beads for the definitions of structures will be as follows: (a) for the primitive and pair action propagators,

and

with all the beads being significant and equivalent; and (b) for SCVJ,

and

with the odd-numbered beads playing the role of the

initial ones,

, these being the significant ones and also equivalent among themselves. (Equivalent means that the mathematical treatment is the same for every bead in the sample).

It may be worthwhile to highlight some facts contained in the foregoing discussion. Each closed path contains

marked imaginary-time instants

or

such that: conventionally,

corresponds to

to

to

…, and

to

. The continuous description is retrieved in the limit

which may seem obvious but runs deeper than one might think at first sight, as no errors creep in the process (i.e., Trotter’s theoretical accuracy) [

3,

9]. Moreover, note that the taking of the imaginary-time origin at

has nothing special; it could have been taken at any other

instant of the

X-sequence, since translational

invariance must hold. In this regard, the only requirement is that once the origin is chosen, it must be applied to every atom/nucleus/particle path in the system for consistency reasons [

9]. The imaginary-time evolution is periodic in that

as is customary in Fourier analysis (this does not mean that

whatsoever!). Finally, the recipe for structural studies: all the beads are significant in the primitive and pair action cases, although only the odd-numbered beads are significant in the SCVJ case.

For the reader’s convenience, the explicit forms of the effective potential

dealt with in this article are worth giving. The optimal

P discretization is assumed in each case. For helium-3, the SCVJ propagator leads to [

12]:

where

is the atom mass, use is made of the pairwise interaction approach

involving the pair potentials

,

the primed

denotes the cyclic property

, the parameter

is a real number in

and

is the unit vector

Note that the interactions between beads occur if and only if the beads share the same

t-label, and that a recommended value for

is

[

12]

Furthermore, the nonequivalence between even- and odd-numbered beads is apparent; it influences not only the structural calculations but also the thermodynamic ones, although in quite different practical forms (e.g., in thermodynamic evaluations using

all the beads play a role) [

12,

14,

96,

97]. The SCVJ propagator is accurate up to

and its associated partition function is up to

. For the quantum hard-sphere fluid, the effective potential

is built with the Cao-Berne propagator (CBHSP) [

76] that, for hard spheres with mass

and diameter

can be cast as [

81,

82,

97]:

where, once again, the cyclic property implied by

applies to the corresponding sum and product that run over

t. The pairwise approach for the interactions between equal-

t beads is used;

is the usual hard-sphere potential that vanishes for

and becomes infinity for

and

is the angle defined by

and

The equivalence among all the beads in the sample is clear in this case. Also, there are no specific rules for the accuracy of pair-action propagators; their effectiveness is to be checked by increasing

P, but they are extremely efficient in reducing the optimal number of beads [

9,

70,

71,

76,

106,

107,

108]. Equations (9) and (10) illustrate the analogies and differences between the effective potentials

for both types of systems. Both possess a formally identical first term on the right-hand side that contains the image of

P-membered closed necklaces (i.e., free-particle contributions [

2,

4]). However, the rest of the terms clearly differ from one another, owing to: (a) the characteristics of the interparticle potentials involved in their constructions, which bring about the appearance of forces in SCVJ [

12] and of kinetic correlation effects in CBHSP (the contributions from adjacent beads in different necklaces) [

97]; and (b) the bead symmetry and asymmetry present in CBHSP and SCVJ, respectively.

3. Quantum Fluid Structures

The whole set of equilibrium structures of a monatomic fluid in the thermal quantum diffraction regime can be deduced from the basic form given in Equation (8). In achieving this task, the related developments are to be complemented with the linear response considerations of external weak fields

acting on the fluid [

14,

19,

32,

78,

79]. Thus, one finds the following classes and associations: (a) total thermalized-continuous linear response TLRn, associated with continuous external fields

(b) centroids CMn, as a particular case of TLRn, since its corresponding continuous field acts as

where

f is a constant strength; and (c) instantaneous ETn, associated with singular fields that cause the localization of the thermally delocalized quantum atoms (nuclei) in the fluid sample, i.e., the fields used in elastic X-ray diffraction or in the inelastic scattering of neutrons [

20,

21,

22,

24], for which collision processes are involved [

27,

79]. (As stressed earlier, zero-spin-atom BE fluids also follow the same systematics [

19,

78,

79]).

Remarkably, the classes CMn and ETn keep a classical-like pattern in that the thermal quantum delocalization of the atoms (nuclei), although accounted for in their developments at every structural

n-level, is not obviously patent in the resulting analytic equations for their structure factors [

9,

19]. In sharp contrast, the class TLRn includes nontrivial particle self-correlations in the formulations at every

n-level [

14,

19,

32],

The analysis involving fields completes the standard probabilistic method for the definition of structures [

9,

12,

13,

26]. For conceptual reasons [

26,

27,

28,

37,

45], these quantum developments can be extended fully if they are carried out in the grand canonical ensemble [

14,

19,

30,

32], although the use of the canonical ensemble also serves the primary purpose of establishing basic formal definitions of the structures [

26,

27,

28]. In this connection, it is worthwhile to stress that, albeit the parallel reasoning employed in the classical domain, based on functional calculus operating with

, is an excellent guide [

26,

37,

45], the quantum complexity does not allow one to follow such a procedure in its entirety. The specific nature of

may make certain classical-like manipulations either meaningful or void in the quantum domain. Moreover, some special mathematical objects that are perfectly defined in the classical domain, as associated with the grand canonical ensemble (i.e., the direct correlation functions

[

37,

45], may not be defined in an exact manner for every quantum structural case [

19,

32]. Given that, for computational reasons, this work will be focused on CM3 and ET3, attention to their main theoretical features is given in this Section.

3.1. The Centroid Structures

3.1.1. Opening Centroid Facts

The centroid concept in quantum statistical mechanics arose within Feynman’s path integral formulation (PI) of the equilibrium behavior of many-body monatomic systems at nonzero temperatures [

1,

2]. For the centroid definition to be made, thermal quantum diffraction effects were required to completely dominate the system behavior. The centroid associated with atom

j is defined as the “center of mass”

of its representative closed path

that, for this purpose, is always considered to have a uniform “mass-density” along its contour. Thus, the centroid concept can be formulated per atom

j as follows [

1,

2]:

The same definition may be applied to every delocalized particle composing neat many-body systems, so long as they may be described by one-site models (e.g., liquid deuterium [

109], liquid para-H

2 [

97,

110,

111,

112], liquid N

2 [

113], the hard-sphere fluid or solid [

29,

81,

82,

97], etc.).

Application of a variational principle leads to approximate (semiclassical) forms of the partition function in terms of the foregoing centroid variables [

1,

2,

114,

115]. The main result of these approximations is contained in the centroid-effective interparticle potentials

that shape the variational semiclassical partition functions (intercentroid distance

The

potentials correct the (usual) interatomic potential energies

but differ dramatically from them in that they depend on the parameters

and

m. There is, obviously, formal equivalence among the centroids that can be defined in this simplified way to model a given monatomic fluid. However, it is worth realizing that these objects are not representations of the true particles/atoms of the fluid [

14]; in fact, centroids mimic a fluid at a higher density than the actual one, and the conclusions drawn from their only use do not necessarily apply to the properties of the quantum system under study [

12,

13,

14,

80,

85,

90,

94,

114,

115,

116,

117,

118].

The best illustration of the foregoing fact is, perhaps, given by the centroid structures, which can be directly calculated from the centroid-effective partition functions in classical-like ways (MC or MD) [

14,

84,

85,

117]. The determination of the actual particle correlation structures does need special convolutions [

84,

85,

117]; the latter involve particle thermal quantum packets (i.e., representations of a delocalized particle around its centroid, which may be nontrivial Gaussians) and the centroid structures, producing approximations to the true path integral TLRn [

14,

85]. These PI centroid-based approaches are far more useful than the well-known Wigner-Kirkwood expansion [

67,

119,

120], even when the latter is extended to highly sophisticated forms [

121,

122,

123]. Nonetheless, the thermodynamic and structural predictive powers of the

effective potential pictures are limited: they cannot yield complete results, nor lead to accurate pictures of the real fluid under increasing quantum effects [

14,

85].

Despite the incompleteness of the centroid-effective approximations, the usefulness of the centroid concept as seen from the full PI perspective exceeds expectations [

12,

19,

34,

78,

90,

94,

112] (see below). The starting point is the discretized version of the PI formulation, Equation (8), which involves a faithful probability density (i.e., nonnegative everywhere). Note that no variational approximation is involved here and, therefore, this “exact” realization of the centroid concept is not the same as that arising from the

schemes [

85]. Through PIMC and PIMD simulations, one can gather statistics related to the

n-body general structural quantities (correlation functions

and structure factors

, in particular the centroid structures [

19,

32,

33,

34,

35,

78,

97]. The grand canonical ensemble derivations for the centroid CMn class need to consider a field

of constant strength

f and its main features are given below [

19,

32,

78,

94].

3.1.2. PI Centroid Formulations

The PI grand canonical partition function in the presence of

can be written as:

For the SCVJ and CBHSP frameworks, the centroid variables are given by [

12,

14]:

where each definition can be viewed as the proper discretization of Equation (11). Therefore, the general form of the partition function can be reformulated as [

19,

30,

78]:

In Equation (14),

the de Broglie wavelength is

, and

stands for the corresponding PI effective potential. The foregoing form of the partition function is akin to a (semi-)classical partition function, and it is ready to carry out the functional derivatives with respect to the field, i.e.,

by applying the standard classical procedures [

27,

28,

45,

77]. Accordingly, the structural results for centroids are of a clear classical-like nature [

19,

30,

78]. Hereafter, the grand canonical ensemble averages at zero field

will be denoted by

, and those in the canonical ensemble by

The first three functional derivatives of Equation (14) with respect to

lead to the centroid structural functions up to the triplet level. They can be cast as [

19]:

Equations (15) define the generalized quantities

which contain the in-the-field correlation functions

up to the very same upper level

n Application of Yvon’s linear response developments [

27,

77] implies to take

on the right-hand sides of Equations (15). Thus, the trivial result at

can be cast as:

where

is the mean number density for the isolated-from-

quantum fluid. At the levels

and

one obtains the generalized zero-field centroid structures that, with the use of the total correlation function

can be written as [

19]:

where the

and

correlation functions are analogous to the usual two- and three-body correlation functions in the theory of classical homogeneous and isotropic fluids [

26,

27,

28]. The latter are defined by the following ensemble averages involving Equation (12) at

where the generic intercentroid distances are defined in terms of auxiliary

q variables, i.e.,

These spatial averages can be determined via PI simulation by following closely procedures parallel to those applied in the study of classical monatomic fluids [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

41,

46,

48].

The formulations of the static structure factors, the pair

and the triplet

are obtained through the Fourier transforms of

and

respectively. Thus, one finds [

19]:

In the foregoing formulas, the

k wave vectors define the momentum transfers from the field to the fluid (i.e.,

The operative expressions take the forms

and

in which a modulus-variable

denotes the corresponding wavenumber and

is the angle between the wave vectors

and

From the PI computational standpoint, the centroid pair and triplet structure factors can be fixed through the ensemble averages [

18,

19,

32,

96]:

where the reader’s attention should be drawn to the fact that the

-evaluations at

and

are avoided, as they are not directly accessible in simulation work [

27,

46].

At higher orders (

the process can be iterated giving the generalized correlation functions

that describe, from the centroid standpoint, the loss of homogeneity of the quantum fluid brought about by

. In general, one finds the linear response relationships

:

Equation (24) results from Fourier transforming the center-right-hand side of Equation (23), which takes advantage of the translational invariance [

28] of the fluid structural quantity

). As seen, in Fourier space, the variation

is a linear functional of the field applied. Also, note that the centroid structures are intermediate quantities, since the application of a weak field of constant strength would lead to the TLR2 response function as the, in principle, measurable object [

19,

30,

32]; centroids as such do not couple physically with external fields, actual particles do.

From the practical standpoint, the correlation function and structure factor calculations are more affordable using the canonical ensemble, involving a sample size

in a box of volume

at temperature

T. In relation to this, the corresponding averages for the centroid structures given above, Equations (17) to (22), only need to reflect the changes associated with the reduction

; for example, the triplet Equation (22) in the canonical ensemble reads as:

As for the zero-wavenumber situations

, costly PI extrapolation procedures must be employed to obtain approximate answers: by increasing consistently

and

so as to keep the number density

constant [

46], lower

k can be reached and extrapolations to zero wavenumbers may be obtained.

3.1.3. The Exact Centroid OZn Framework

In the quantum diffraction regime, the important point regarding PI centroids, Equations (13), is that they behave according to the same rules for structures applicable to classical monatomic fluids at equilibrium [

27,

40,

45]. This is of great practical importance when addressing

k-space questions. In fact, it has been demonstrated [

19] that the (hierarchies of) centroid direct correlation functions and structure factors

can be defined in the same fashion as in the classical domain. Therefore, the underlying classical Ornstein-Zernike framework (OZn) [

37,

38,

40,

45,

124,

125,

126,

127,

128], which is consistently defined in the grand canonical ensemble, can be safely applied to the PI centroid correlations and their structure factors. Hence, one may deal with the centroid zero-wavevector problems considered above in an essentially “exact” manner. In particular, at the pair OZ2 and triplet OZ3 levels, in the absence of the external field (

one can write rigorously the following basic equations for PI centroids [

19,

30]:

where

and

are the Fourier transforms of the functions

and

respectively. Equation (27) is the pair-level Ornstein-Zernike equation that defines the pair direct correlation function

which is a short-ranged function that shows a quick decay to zero with increasing distances [

46]. Equations (28) belong to Baxter’s exact hierarchy, under uniform changes of density [

38,

45], for the direct correlation functions in the quantum

extension [

19]. Equations (29) and (30) are the analytically closed reformulations of the pair and triplet structure factors defined in Equations (19) and (20). The advantage of Equations (29) and (30) is clear: none of them explicitly contains the simulation-intractable

terms [

46] that appear in the “raw” analytic formulations based on the Fourier transforms of the

and

functions.

Note that all the structural functions depend on the density and the temperature, although such dependence is only written when necessary [

20,

27,

60,

61]. Equations (27)-(30) are mathematically exact and yield the formal solutions to the problematic zero-wavevector situations: (a) at the pair level, via

[

78]; and (b) at the triplet level, via Equation (28b) plus the symmetry property

for the cases

[

45].

However, once the function

in real space is known (via PI simulation), the question arises as to how to determine the pair and triplet structure factors using the direct correlation functions

and

These latter functions are defined by integral equations, and a hierarchical structure is in the way. In this regard, there are theoretical methods derived in the classical domain that, being based on closures, provide answers to these key problems [

14,

40,

45,

46,

125,

126,

127,

128]. These methods are highly accurate and reliable at the level

, and they can also be successfully applied to quantum calculations (regardless of the structural class!) [

14,

78,

85,

96,

97]. However, the same favorable situation is not generally found at the level

, neither in the classical case [

44,

45,

47] nor in the quantum case [

19,

33,

35]. In any event, one has two complementary routes to compute the foregoing structure factors: (a) the computationally “exact”, though incomplete (and expensive), based on the PI simulation of Equations (21)-(22) -or better, of their more affordable translations into the canonical ensemble-; and (b) the theoretically exact, though subjected to the closure uncertainties in the triplet case, based on the general OZn framework summarized in Equations (27)-(30).

An observation of practical value is in order here. The standard PI simulation of the structural functions in

r-space using the canonical ensemble, i.e.,

, also poses well-known theoretical drawbacks (e.g., inadequate asymptotic behaviors and finite sample size) [

19,

81]. To cope with this general problem [

26,

46,

126,

127], some corrections [

127,

128] allow one to improve the pair-level canonical results, thus yielding good approximations to the grand canonical pair structures [

34,

35,

81,

96,

97]. These corrections are based on the use of the Ornstein-Zernike OZ2 framework and go both ways:

r-space

k-space, that is, involving jointly the pair of structures

thereby benefiting the whole centroid pair structural determination issue.

3.1.4. The Centroid Usefulness

Although centroid structures are not directly accessible via experimental techniques, it is important to make some further comments on the global usefulness of the centroid quantities. In addition to the abovementioned effective potential approximations, one finds the following applications of the set :

(i) Keeping track of the closed paths (or necklaces) associated with the atoms

j (or the one-site particles) throughout general PI simulations. Without any loss of generality, the closed paths can be expressed as

where use of the auxiliary general path-vector

is made

runs over the bead labels

Thus, the displacements of the particles

can be referred to those of their moving centroids

plus those of the closed paths

around the centroids. This also yields the useful PI image of the centroid-constrained paths for every particle

j [

6,

81,

82,

85,

90,

91,

92,

93,

94,

95,

129].

(ii) Fixing, via OZ2-

the equations of state for fluids with thermal quantum diffraction behavior [

19,

78,

81], since in the grand canonical ensemble one finds:

where

is the isothermal compressibility.

(iii) Formulating higher-order number fluctuations, as for example [

19]:

where the exact centroid relationships with OZ2 and OZ3 are to be noticed [

32].

(iii) Characterizing global order in quantum samples through the use of centroid adapted quantities: Steinhardt et al’s parameters [

83], configurational pair structure factor information, etc. [

6,

34,

82,

97].

(iv) Designing approaches to deal with quantum dynamics (e.g., centroid molecular dynamics [

90,

91,

92,

112] and other approximations [

80,

94]).

(v) Dealing with coarse-graining approaches in quantum statistical mechanics [

95].

(vi) Studying the number fluctuations under zero-spin BE conditions [

19,

78,

79]. As a result of the action of an external field of constant strength

given the algebraic group character of the

permutations, one can derive a partition function closely similar to (14) involving the conventional PI centroids given by Equations (13):

where the coefficients within the permutation sum are

, and the probability density function at zero field behaves as

[

19,

78]. Consequently, with the proviso that

is used, number fluctuations can be counted as in Equations (31).

3.2. The Instantaneous Structures

Conceptually, the instantaneous ETn class is linked to the context of elastic scattering of radiation. The pair level ET2 can be understood by following the standard quantum treatments [

21,

27] of X-ray diffraction and inelastic neutron scattering. In X-ray scattering [

22,

27], the collisions of the X-ray photons with the electrons of the atoms define the nuclei positions, thereby yielding the actual pair quantum structures associated with this phenomenon: the radial correlation function

and the structure factor

[

9]. In neutron scattering [

21,

24,

27], the neutron-nucleus interactions are described through Fermi’s pseudopotential (a

collision process); this time-dependent quantum phenomenon is characterized by the dynamic structure factor that, through its “elastic reduction” (frequency sum rule), also yields the same pair structures

and

[

27]. For both experimental techniques, the corresponding arguments belong to the general linear response theory [

27], hence the statistical mechanics treatments give, in the end, the same response function from the fluid:

. Such a response is formulated in terms of

in the absence of the external field [

79], the

mathematical form being essentially the Fourier transform of

[

21,

22,

27] (i.e., a “classical-like” formulation). Thus, one finds the instantaneous ensemble average recipes:

where

If the PI formalism is used,

directly translates into the following approximation [

9,

19,

30,

32]:

where the

notation for beads is retained, and the associated structure factor reads as:

where the grand canonical partition function

at zero field is involved [

19]:

(The forms of Equations (33) and (34) can be applied to both the grand canonical and the canonical ensembles [

27], provided that the proper partition function is employed).

Although the basic PI canonical partition function

, Equation (8), already defines the beads that are going to be significant in the structure calculations, centroid-like functional calculus manipulations are inapplicable to the instantaneous class; this fact forces the

condition in Equation (35). If one wished to apply functional derivatives, setting

to obtain the generalized structure functions

, a fundamental difficulty would arise: the collision phenomena localize the actual quantum particles, which is not compatible with the structure of

[

19,

79]. Within the current

framework of nucleus positions, one faces the “collapse” of the atom quantum thermal packets, and the functional derivatives turn out to be meaningless; in fact, if this sort of manipulations were “formally” carried out, one would obtain the total thermalized-continuous linear response structures TLRn [

19,

32]. The functions

and

at levels

can be defined (using

by PI-adapting their classical counterparts (e.g., at

Equations (16c), (18), (20), etc.) [

19]. The reasons behind this procedure are: (a) it is a straightforward consequence of the averaging of the dynamical

n-body number density functions/operators

that define the elemental

structures in real space [

28] (e.g., see Equation (33b)); and (b) consistency with the transition to the classical limit at every

n-level for

[

19]. In this work, attention will be focused on the triplet-level instantaneous structure functions

and

As remarked earlier, grand canonical PI simulations for obtaining structures pose a hard problem because of the computational effort involved. In general, the ETn class computations scale with

(i.e.,

P/2 for SCVJ, or

P for CBHSP), and the practical alternative is based on the canonical ensemble applications [

9,

19,

33,

34,

96]. Therefore, depending on the propagator selected, the instantaneous triplet structure averages read as [

19,

30,

32]:

- SCVJ (fourth-order propagator)

The classical-like OZn framework for the instantaneous structures is not exact but an approximation [

19,

32,

78]. At the pair level, however, OZ2 and its corrections to the canonical ensemble results have proven to be highly accurate in the thermal quantum diffraction regime [

81,

85,

96,

97,

117]. Therefore, applications of OZ3 to the instantaneous triplet structures are well-worth exploring in depth [

19,

33,

35]. In this context, the related basic equations can be translated from the centroid class and written as

:

(Recall that the use of closures is compulsory at every OZn structural level [

37,

38,

39,

40,

44,

45,

46,

47,

125,

126,

127,

128]).

4. Triplet Closures and Associated Features

Given the classical-like forms of

and

, the closures may be applied indistinctly to both of them. For the calculations carried out in this work, the employed closures are: (a) for triplets in real space, Jackson-Feenberg convolution (JF3) [

17] that contains Kirkwood superposition (KS3) [

25], and the intermediate average AV3 [

34]; and (b) for triplets in Fourier space, Jackson-Feenberg convolution [

17,

40,

45], and the symmetrized version of Denton-Ashcroft approximation (DAS3) [

47]. Obviously, the pair information needed arises from PIMC simulations and OZ2 treatments.

The mathematical expressions for the real-space closures are given below.

- -

JF3

where the distances

stand for

for centroids or

for actual quantum particles (the atoms of helium-3, or the one-site hard spheres), and

is Kirkwood superposition [

25], which reads as:

- -

AV3

The Fourier-space closures read as:

- -

DAS3

This closure satisfies Baxter’s exact behavior Equation (28b) only at .

The use of other closures to deal with triplet quantum calculations can be seen in References [

19,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. In particular, when considering Fourier-space applications, AV3 and the elaborate Barrat-Hansen-Pastore factorization ansatz (BHP3) [

45] appear to need very detailed numerical treatments [

19,

45]; this clarifying task is left for future work.

The structure factors

and

given by Equations (30) and (43), respectively, need their corresponding pair and triplet direct correlation functions, and some remarks are necessary here. First, the pair direct correlation functions

and

can be determined in a highly accurate way [

81,

96,

97] with the use of the OZ2 numerical procedure put forward by Baxter, Dixon and Hutchinson (BDH) [

125,

126]. As stated earlier, the BDH application to

comes from an exact OZ2 framework, whereas to

is an approximation. Second, the final closure results for

are, in general, subjected to inaccuracies owing to the hierarchical structure of the direct correlation functions [

38], which is illustrated for triplets by Equations (28) and (41)

Third, the formal use of direct correlation functions yields answers to questions that cannot be exactly solved using PI simulations: the behaviors at zero-momentum transfers

and

which are contained in the theoretical relationships [

19,

32,

78]:

It is worthwhile to make some useful observations here. (a) Equations (48) can be extended to include the TLR case [

19,

32,

78], with

in Equation (48a) and

in Equation (48b). (b) Given the identities in Equation (48a), the ET and TLR extensions of Equation (48b) in terms of their pair

) components are equally valid. (c) Highly accurate estimates of the exact values can be obtained from the OZ2 centroid quantities, as Equations (48) arise from the consideration of the exact role played by

(d) Although the parallel extensions of the whole Equation (48b) to ET and TLR are exact, their practical applications via OZ2 schemes will produce approximations to the exact behavior of the

quantity. And (e) by applying the underlying

k-space symmetry properties [

45], one can also obtain from Equation (28b) the exact values of the triplet CM3 components

:

where the presence of single zero-momentum transfers is to be noticed. The general type of symmetry expressed in Equation (48c) allows one to set sum rules for the

and

components [

32], which are exact for the centroid case but approximate for the instantaneous case.

7. Final Remarks and Perspectives

The present investigation on quantum fluid structures adds new triplet results to the knowledge of fluids composed of helium-3 atoms and of quantum hard spheres, for which initial information can be found in previous works by this author. Both systems are studied under thermal quantum diffraction conditions, although the respective fluid state points differ qualitatively: supercritical for helium-3, and on the crystallization line for quantum hard spheres. Path integral Monte Carlo simulations and closure computations, at the pair and triplet levels of the centroid and instantaneous structures, are performed in the real and the Fourier spaces, and the following remarks can be made.

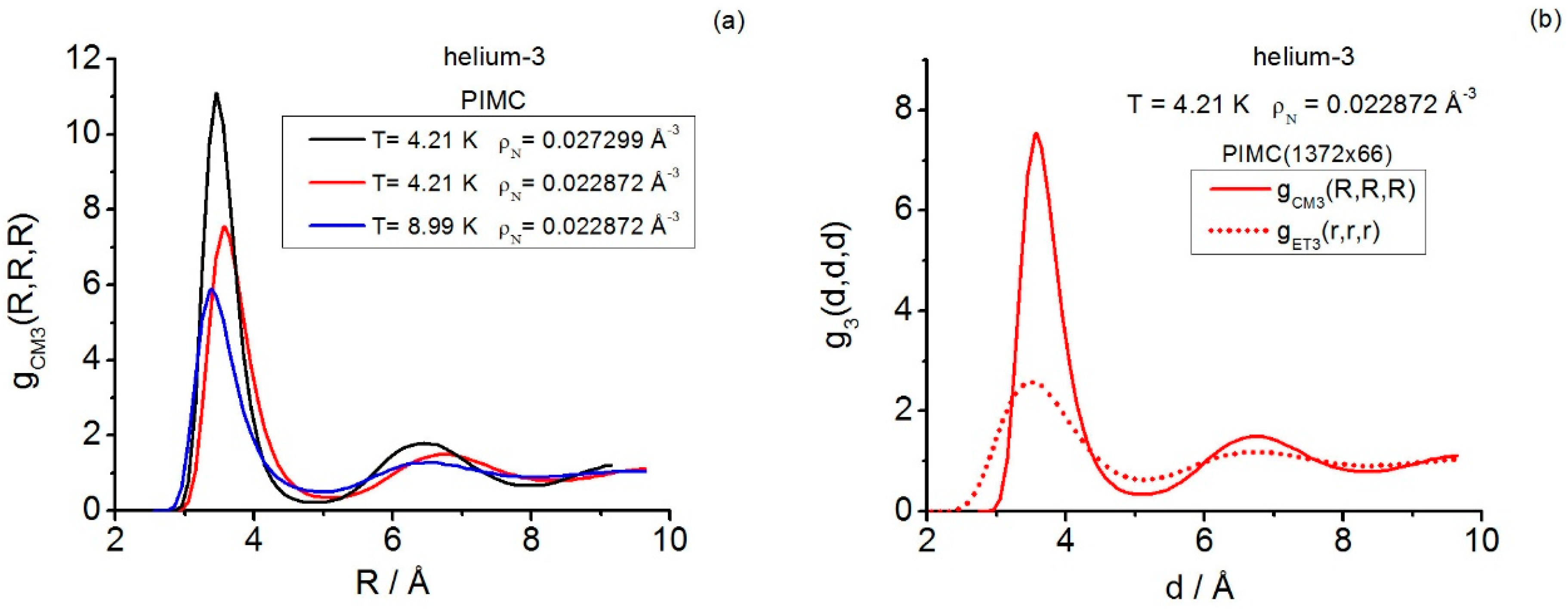

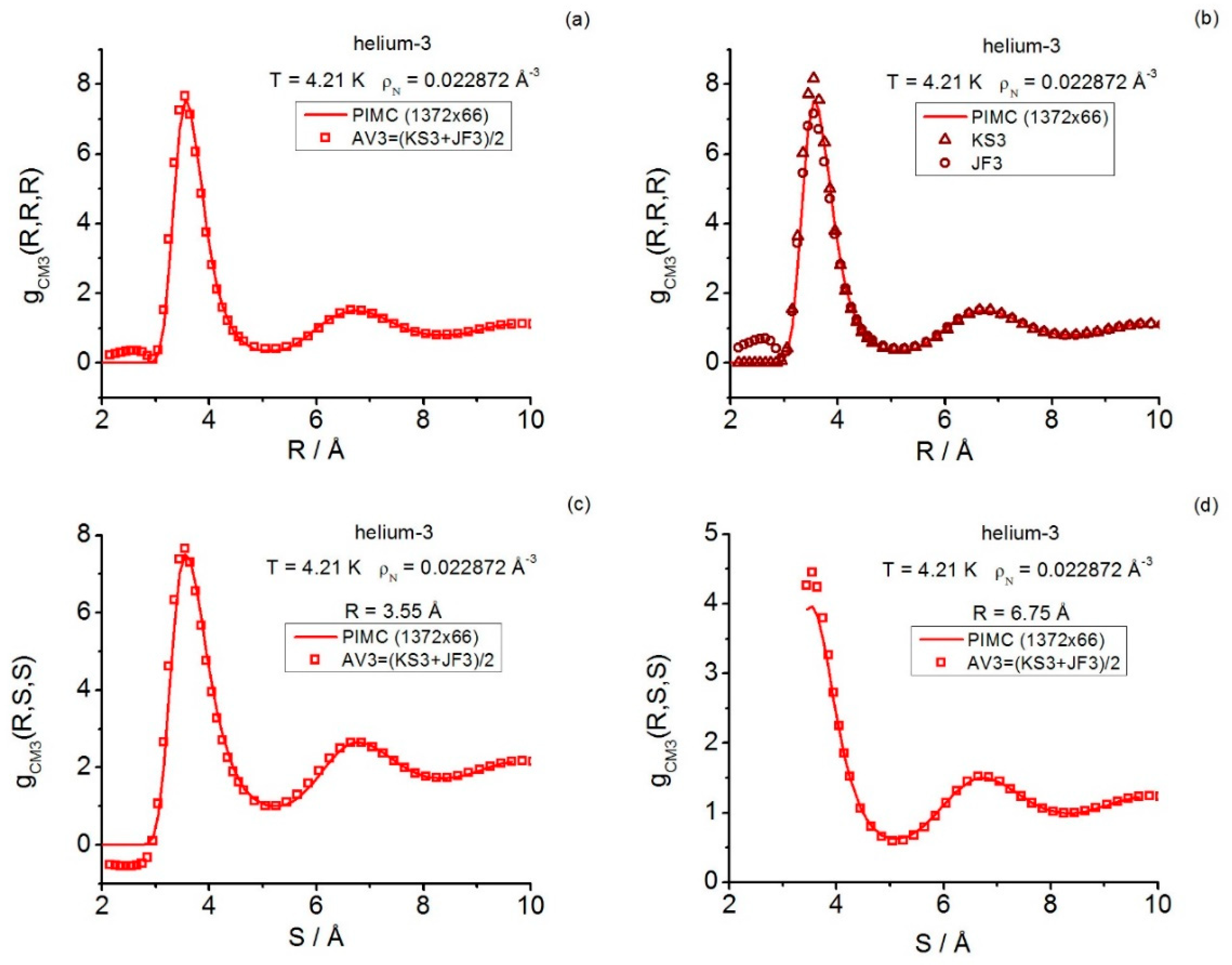

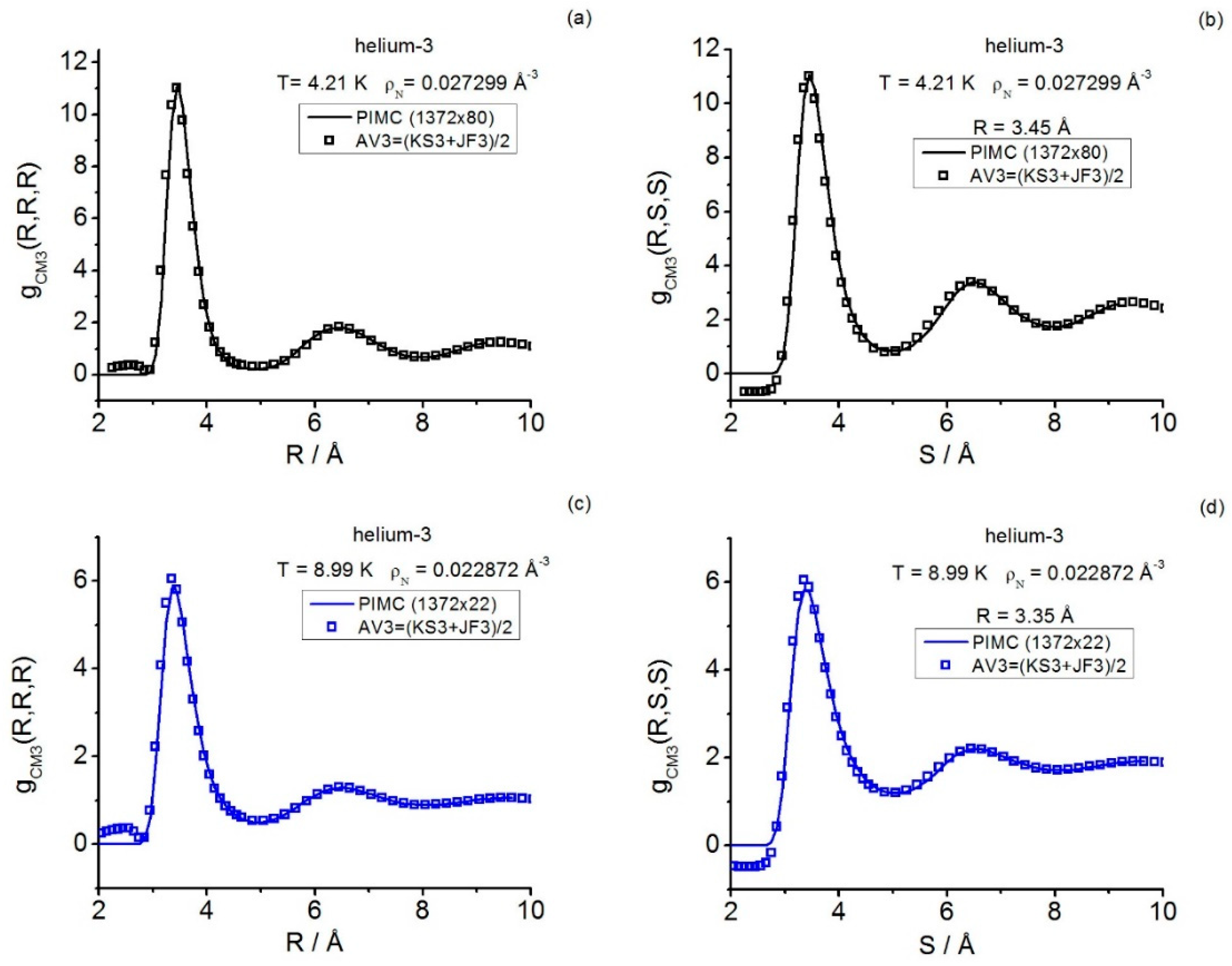

In real space, the path-integral triplet structures (equilateral and isosceles configurations) obtained for helium-3 show that the centroid structure features are more pronounced than their instantaneous counterparts, in agreement with the general expected behavior since centroids are known to mimic a fluid at a higher density than the actual one. The related whole path-integral computational load depends critically on the simulation sample size -canonical ensemble-, which includes the number of necklaces (particles) and the number of beads even under strong quantum diffraction effects, this task is known to be perfectly affordable at the pair level, and, by focusing on the abovementioned specific types of triplet configurations, it is also at the triplet level (run lengths kpasses). Most interestingly, the application of the real-space intermediate closure AV3 to the determination of centroid and instantaneous triplet structures allows one, via comparison with exact path integral data, to confirm the great usefulness of this approximation: by analyzing structural conditions more extreme (the centroid correlations in helium-3) than those previously studied elsewhere, the AV3 closure performance is, once again, excellent and far less expensive than full path integral simulations.

AV3 is the straightforward average of two basic closures: Kirkwood superposition and Jackson-Feenberg convolution; both closures show clear deficiencies in the treatment of the triplet features in real space. Therefore, although AV3 partly inherits the unphysical short-range-distance failure of the Jackson-Feenberg convolution, the compensating effect of the abovementioned average makes AV3 capture most of the salient features of the path-integral centroid correlations (equilateral and isosceles). Such a surprising triplet fact in real space was observed in recent works by this author (e.g., centroid and instantaneous triplets in the quantum hard-sphere fluid, and instantaneous triplets in supercritical helium-3). Within the significant correlation ranges of distances (i.e., those showing nonzero path-integral structure values), the AV3 applicability to fluids with quantum behavior appears to cover diffraction effects characterized by substantial values of the degeneracy parameter , including singular model systems (e.g., quantum hard spheres for and real systems (e.g., helium-3 for However, note that AV3 worsens as the density increases along isotherms, and it does not capture relevant maximum region behaviors in the isosceles configurations either. All in all, closures may give good and cost-effective “pictures” of complex interrelations among the actual atoms/particles in fluid phases. In this regard, the further centroid triplet results obtained in this work indicate that, in the study of quantum fluids via closures, the improvement of AV3 is well-worth exploring, which should also incorporate general three-body configurations in the study. When trying to fix the abovementioned density effects that AV3 suffers from, the time-honored Abe’s developments may be a good guidance.

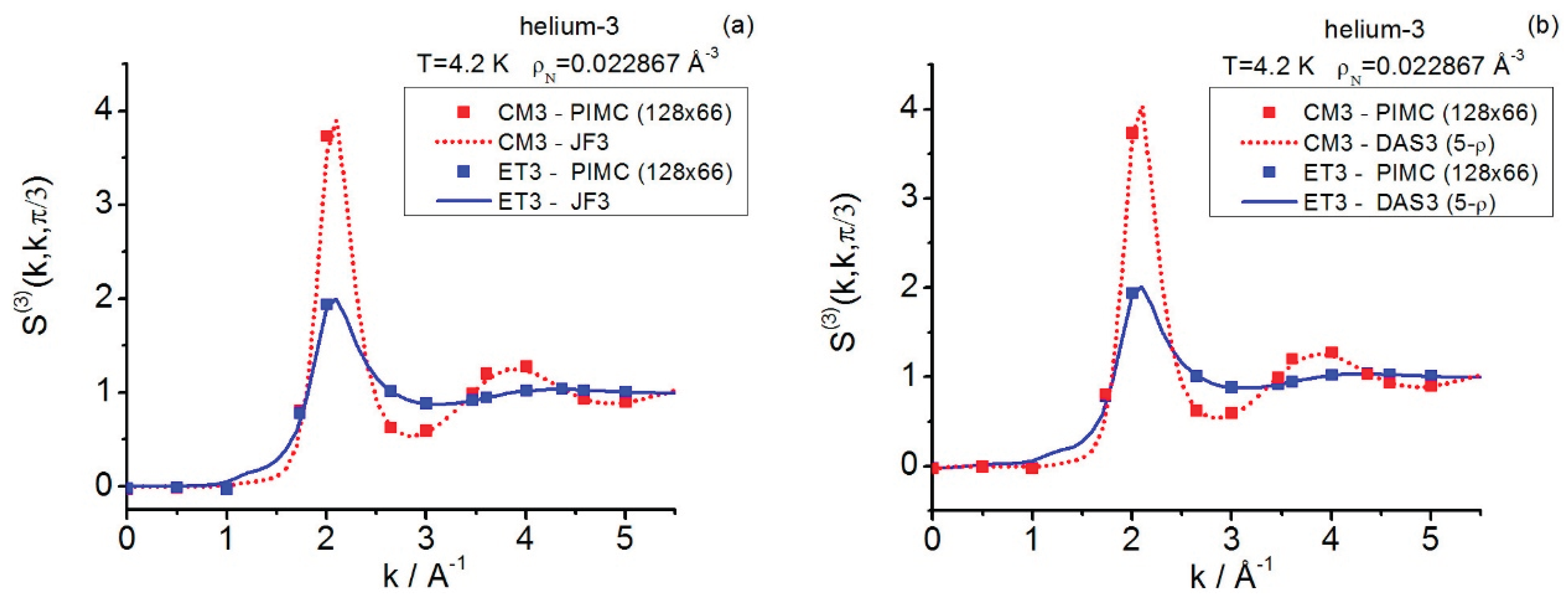

In the study reported in this work, the Fourier space applications to the fluid centroid and instantaneous triplet structures (equilateral and isosceles wave-vector geometries) illustrate the nature of these highly demanding calculations. In general, path integral Monte Carlo simulations present strong fluctuations in the structure factor component values along the Markov chain; this fact becomes critical in the vicinities of the main peak amplitudes investigated for both the centroid and the instantaneous structure factors. This imposes very long run lengths ( Mpasses) to achieve reasonably reduced statistical errors in such regions. Such a hard computational situation is aggravated by some factors: (a) the number and sizes of the sets of commensurate wave vectors, which are needed to obtain significant descriptions of the components analyzed; and (b) the conditions under study, which put lower limits to the simulation sample size to be utilized (i.e., in general, changes of phase influence and diffraction effects influence ). In this connection, selective sampling of the path-integral structure factor components (e.g., equilateral main peak amplitudes) can be used for increasing the accuracy of the results in specific regions. In any event, currently, the whole quantum fluid triplet study in Fourier space via path integrals, even in the diffraction regime, with its diversity of classes and 4-D intricate numerical behavior, poses a formidable challenge in every respect. Accordingly, the use of closures in Fourier space is a useful way to obtain insights into the quantum triplet structure factor issues.

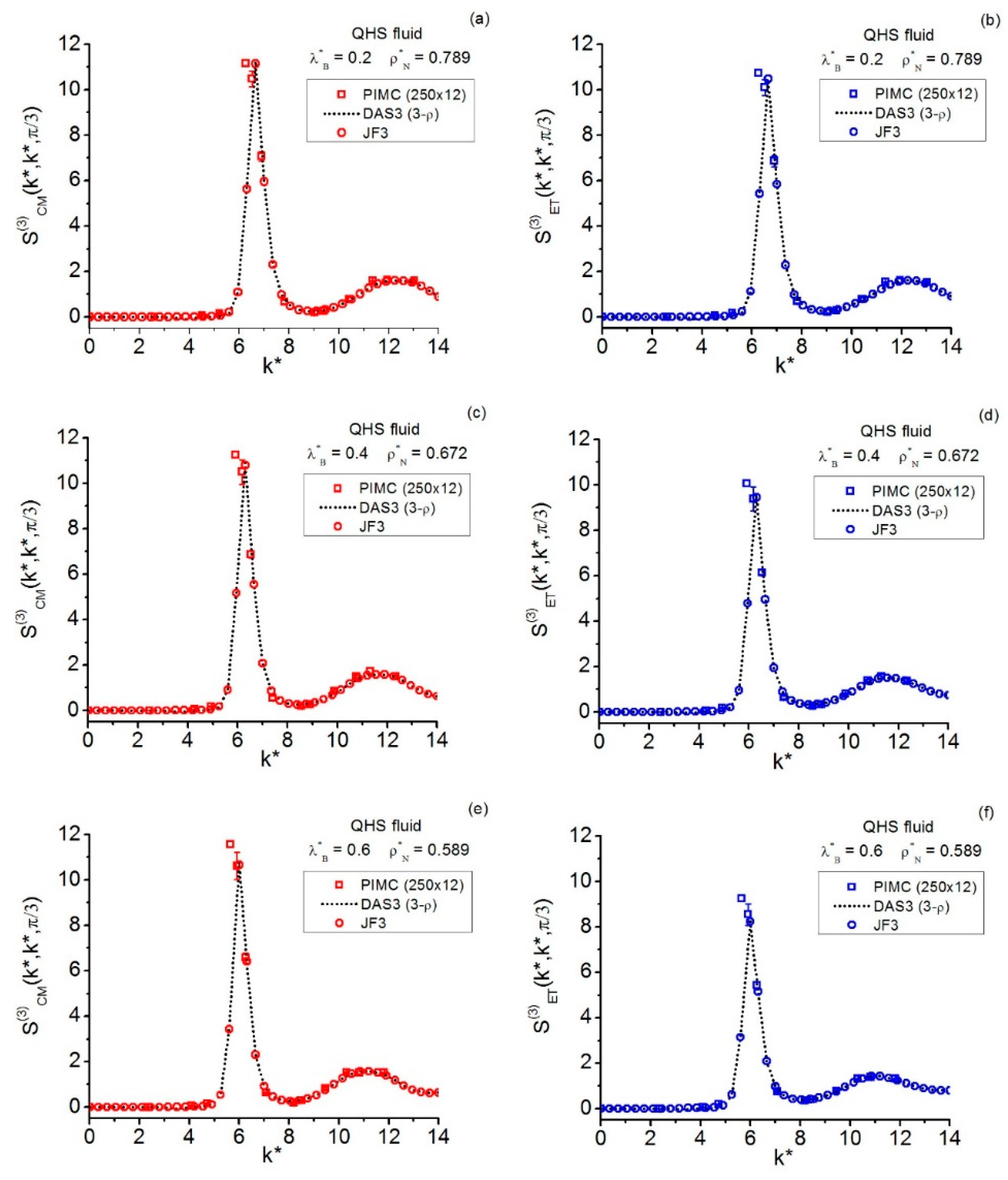

The current path integral results clearly indicate that, for low and not large wavenumbers, the Fourier equilateral components take on (small) negative values in both the centroid and the instantaneous cases. This exact equilateral feature is observed at every fluid state point investigated in this work (helium-3 and quantum hard spheres). However, as regards the present closures, such a feature is only captured by the symmetrized Denton-Ashcroft and not in its full details (Jackson-Feenberg convolution cannot give this behavior). Thus, with respect to these below-zero regions, the centroid triplets are in general better represented than the instantaneous triplets by such Denton-Ashcroft closure, a feature to be ascribed to the classical-like structural nature of centroids (i.e., the exact theoretical applicability of Ornstein-Zernike schemes, in particular the pair OZ2, to centroids). In addition, as compared to the data obtained via path integrals, both closures give reasonably good equilateral results beyond the below-zero regions, with Jackson-Feenberg convolution closure becoming dominant for large wavenumbers.

Continuing with the equilateral components, the path-integral centroid calculations in Fourier space for the quantum hard-sphere fluid lead, via interpolation in the computed data tables, to equilateral main-peak amplitude estimates that suggest a “constancy” in these centroid quantities along the section of the crystallization line studied. This surmise needs more elaboration before stating its validity and range of applicability. Therefore, extended simulation work is needed to: (a) reduce the current statistical errors, and (b) analyze more extreme quantum conditions. (As an aside, note that the analogous maxima of the instantaneous components cannot be candidates for “constancy”, because they show a definite decay pattern with increasing quantum effects). Moreover, other triplet centroid features in Fourier space (e.g., the maxima of salient isosceles components, as those near angles etc.) might be subjected to this sort of “constancy” search. Even though the analysis of these possibilities entails costly simulations, this issue seems well-worth studying; its potential applicability to complex real systems, as a triplet way to provide more insights into quantum freezing phenomena, should be sufficient motivation to justify the effort. Furthermore, in the search for triplet-structure signatures of distinctive quantum fluid behaviors, the role of the centroid component should not be overlooked (recall its relationship with the third-order number fluctuations). The present results for the fluid phases analyzed give a fact that indicates a negative skewness for all of the particle number (marginal) distributions involved in this work. Therefore, the ranges of values that this quantity may take under different thermodynamic conditions deserve further investigation; this is essentially a pair-level task, which could be undertaken by paying careful attention to the accuracy in the density derivatives involving just the centroid pair direct correlation functions (Equation (28b)).

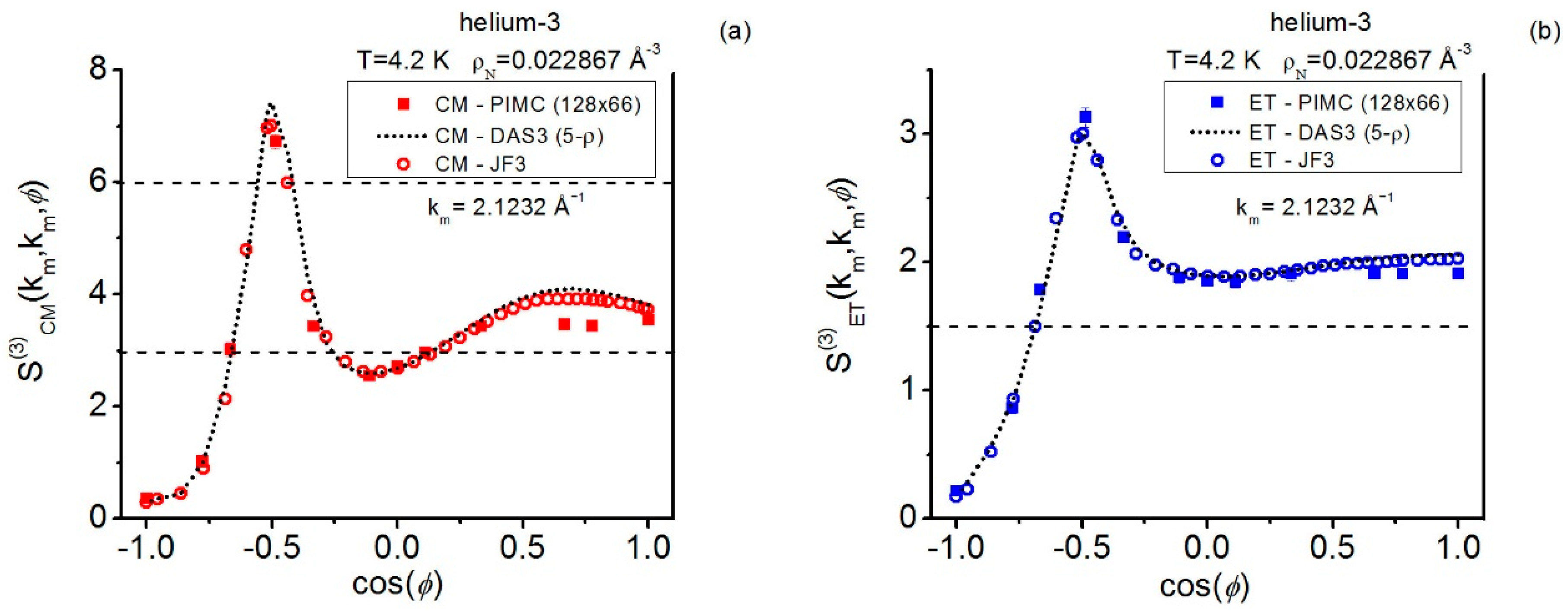

Although, for low wavenumbers, the isosceles components may be expected to take negative values (as suggested by closure calculations), the current path-integral applications to helium-3 for the centroid and instantaneous structures, recorded at a wavenumber close to those of the maximum amplitudes of the pair structure factors, show that the exact path integral values stay above zero within the complete angular range . The symmetrized Denton-Ashcroft and Jackson-Feenberg convolution closures produce results remarkably close to the path integral treatment within the subinterval but they fail in its complement where Jackson-Feenberg’s behaves in a wrong way that propagates into Denton-Ashcroft’s. The foregoing facts apply to both classes of isosceles results, centroid and instantaneous, although the discrepancies from the path-integral reference values are especially pronounced in the centroid case (i.e., the closure significant undulations against the path-integral leveled behavior). These results suggest that the study with other more numerically-involved triplet closures (e.g., Barrat-Hansen-Pastore) may be highly significant and also help to clarify how to improve closure approaches.

The quantum fluid triplet topic presents one with many challenges, theoretical and computational. The coming and extended use of increasingly efficient computational resources (i.e., exascale and, hopefully, quantum computers) can thrust the topic of fluid n-body structures forward, especially in the quantum domain. In any event, the research on triplet closures in both the real and the Fourier spaces will remain a valuable complement to the thorough understanding of the quantum fluid structures. It is expected that not only Statistical Mechanics but also disciplines involved in materials design can benefit from all these developments.