1. Introduction. (Re)Build It Circular

As circularity has become a central paradigm of sustainability, the transformation of the built environment increasingly focuses on the regeneration of material cycles and the reduction of resource extraction. While the culture of circularity has found a clear field of application in new construction through various strategies—such as design for disassembly and adaptability [

1], material passports [

2], digital twin–based traceability systems [

3], and modular prefabrication with reversible connections [

4]—its implementation in refurbishment, regeneration, and post-disaster reconstruction remains significantly more constrained. Post-disaster reconstruction processes, whether triggered by natural hazards or human-induced events, are in fact full-fledged forms of urban transformation with particularly high environmental and territorial impacts. They not only generate large quantities of construction and demolition waste, in the form of rubble and debris, but also impose extensive and time-critical interventions that profoundly reshape the built and natural environment. Despite this, post-disaster reconstruction largely remains outside the scope of circularity-oriented approaches, continuing to rely on linear, emergency-driven models that limit the integration of circular principles [

5].

These limitations are mainly due to the structural, regulatory and cultural rigidity of the existing built environment, where heritage-protection frameworks, fragmented ownership and the lack of standardized digital material data hinder the full adoption of circular design principles. In such contexts, the potential of circularity lies not merely in substituting materials or components but in rethinking the building as a dynamic resource system—capable of continuous transformation while preserving its historical, social and spatial identity [

6].

This challenge becomes particularly evident in reconstruction processes affecting culturally and landscape-sensitive territories, such as the sub-Apennine inland areas of Central Italy, where seismic events intersect with long-standing environmental and socio-economic fragilities. The most recent large-scale earthquake sequence in this area dates back to 2016; almost a decade later, reconstruction processes remain markedly slow and fragmented. In these regions—characterised by historic settlement patterns, strong material identities, and limited infrastructural capacity—the built environment has traditionally relied on locally sourced materials, deeply embedded in construction practices, landscape logics, and community identities. Within this context, rubble assumes a dual and inherently contradictory role: on the one hand, it constitutes a material testimony of local construction cultures, techniques, and resources; on the other, it represents a major operational and logistical constraint, whose prolonged management and disposal have become a critical bottleneck, delaying reconstruction and reinforcing linear, waste-oriented approaches [

7].

This paper addresses this systemic gap by introducing Rubble as a Materials Bank (RMB), a circular post-disaster reconstruction approach developed at the School of Architecture and Design, the University of Camerino (Italy). RMB conceptualises earthquake debris as a traceable and programmable material stream—rather than an inert by-product—capable of enabling local, culturally coherent, and low-impact rebuilding. The framework establishes a continuous rubble-to-component chain that links material characterisation and digital survey with AI-supported sorting, robotic fabrication, and reversible design, so that recovered resources can be selected, processed, and reintegrated into new construction through digitally informed, automation-ready workflows

This study pursues a set of operational and cultural–territorial objectives, articulated across two complementary domains.

On the operational and methodological side:

define a computational and material methodology capable of transforming the heterogeneity of seismic rubble into a knowledge-rich resource;

articulate an integrated rubble-to-component chain linking material data, digital processes and fabrication workflows;

validate selected portions of this chain through the TRAP project, developed within the European TARGET-X programme.

On the cultural and territorial side:

demonstrate how material characterisation and digital traceability can form the informational backbone of circular reconstruction;

assess whether rubble-derived components can support culturally coherent reconstruction aligned with the material identity of sub-Apennine settlements.

By embedding rubble reuse within a multi-layered informational and robotic infrastructure, the proposed methodology reframes reconstruction as a regenerative process in which environmental sustainability, territorial identity, and digital innovation converge, thereby foregrounding the materiality of reconstruction as a central dimension through which post-disaster continuity and transformation are negotiated.

2. The Materiality of Reconstruction

In disaster-affected inner territories such as the historic villages of Central Italy—characterised by vernacular construction systems based on locally sourced materials—post-earthquake reconstruction often confronts conditions in which structural damage is so severe that repair is no longer feasible and, in some cases, even in-situ rebuilding becomes impracticable. Extreme events may compromise the very stability of settlement sites, as in the case of Pescara del Tronto, in the municipality of Arquata del Tronto on the border between the Lazio and Marche regions, where large portions of the village slid down the mountain ridge during the 2016 seismic sequence. In such contexts, reconstruction cannot be reduced to the technical repair of collapsed structures nor to the straightforward reproduction of pre-existing urban and architectural configurations, as suggested by the

dov’era, com’era paradigm [

8]. When applied literally, this approach has shown clear limitations in territories marked by demographic shrinkage, changing risk scenarios, and environmental constraints [

5,

9].

In such contexts, rubble can assume a strategic role: when reframed as a recoverable material resource rather than as waste, it may operate as a bridge between pre- and post-disaster conditions, preserving traces of local material cultures while enabling new reconstruction and territorial reconfiguration processes. As argued by Bianchi and Ruggiero [

10], post-disaster reconstruction in inner areas thus constitutes a cultural and territorial operation in which continuity is not achieved through replication, but through the material rearticulation of disrupted landscapes, practices, and identities.

From this perspective, the stones, aggregates, and construction materials of collapsed buildings become tangible carriers of continuity, anchoring collective memory and local identity when spatial layouts and architectural typologies are irreversibly altered. Reconstruction therefore extends beyond the restoration of spatial legibility, emerging as a process of material articulation through which communities renegotiate their relationship with place and landscape [

13,

14,

46].

This perspective extends the notion of architectural materiality beyond its conventional association with construction techniques or expressive languages. As argued by Picon [

12], materiality constitutes a cultural and cognitive dimension through which architecture mediates environmental intelligence, historical sedimentation, and technological paradigms. In post-disaster reconstruction processes occurring in historically and landscape-sensitive territories, materiality could no longer be defined primarily by formal continuity or structural replication, but rather by the capacity of recycled and transformed materials to convey memory, territorial identity, and social meaning. In this sense, post-disaster reconstruction may be interpreted as expanding Picon’s concept toward a notion of recycled materiality, in which matter itself becomes the primary medium through which continuity is negotiated after rupture.

This reading, in turn, frames rubble not as an inert residue to be removed, but as a material archive whose recharacterisation, reprocessing, and reintegration into reconstruction require informed and technologically mediated practices [

14]. At the same time, it anticipates the intrinsic ambivalence of rubble, which simultaneously embodies a potential resource for material continuity and a substantial constraint within post-disaster reconstruction processes.

3. The Dual Nature of Rubble

Italy offers a particularly significant field of observation for post-disaster reconstruction in historically and landscape-sensitive inner territories, where seismic events have repeatedly affected settlements characterised by strong material identities and deeply sedimented construction cultures. Across these contexts, rubble has rarely been approached as a material resource and has more often been treated as an obstacle to be removed in order to enable rapid rebuilding. In many cases, reconstruction processes have consequently prioritised the replacement of damaged building stocks through new typologies and materials, frequently producing a growing material discontinuity with historically sedimented settlement systems [

16].

This tendency is evident in several Italian reconstruction experiences. Following the 1980 Irpinia earthquake, continuity with local construction cultures was often set aside in favour of standardised building solutions [

17]. Similar dynamics emerged after the 2009 earthquake in L’Aquila, where large-scale interventions introduced materials—such as timber-based systems—and residential typologies, including linear housing blocks, largely extraneous to the traditional masonry-based building culture and settlement patterns of the area [X]. An emblematic yet divergent case is represented by the Belice Valley after the 1968 earthquake, where rubble was assigned a powerful symbolic role through Alberto Burri’s Cretto, crystallising destruction into a monumental act of memory, while reconstruction proceeded through the creation of an entirely new settlement, detached from the material and spatial logic of the original town [

18].

Together, these experiences highlight both the limitations and the missed opportunities of rubble management in post-disaster contexts, calling for a systematic analysis that is developed in the remainder of this chapter.

3.1. Rubble as Constraint

Earthquakes generate rubble at a scale and speed that far exceed those of ordinary demolition processes, a condition that becomes particularly critical in inner and mountainous territories characterised by limited accessibility and fragile logistical infrastructures. The 2016 Central Italy seismic sequence provides a paradigmatic example: approximately 2.7 million tons of rubble were produced almost instantaneously across hundreds of small settlements, overwhelming waste-management systems designed for gradual and predictable material flows and delaying emergency operations, especially in small sub-Apennine municipalities with limited spatial, organisational, and technical capacity [

19].

These difficulties are further exacerbated by the fragmented territorial structure of Central Italy, marked by dispersed settlements, limited infrastructure, and complex administrative boundaries. In the absence of predefined pathways for disposal, recycling, or reuse, temporary storage sites are often identified ex post during the emergency phase and operate under provisional regulatory conditions, resulting in prolonged material immobilisation and persistent spatial and operational bottlenecks that delay reconstruction and constrain everyday territorial use [

20].

Beyond logistical constraints, the material condition of seismic rubble represents a major limitation for reuse. Unlike controlled demolition waste, earthquake rubble is largely unsegregated and frequently contaminated (

Figure 1), increasing the complexity and cost of sorting operations and often favouring disposal as the least demanding legal option, thereby reinforcing linear waste-management models [

20]. Evidence from recycled aggregate production further indicates that, under certain conditions, processing mixed waste streams may be more expensive than sourcing natural aggregates, limiting the practical uptake of circular approaches in post-disaster reconstruction [

21].

Regulatory frameworks introduce an additional layer of constraint. Under Italian law, materials resulting from collapses and demolitions are generally classified as waste unless directly separable for reuse or recycling [

19]. Although specific exemptions have been introduced in post-earthquake contexts, compliance with European End-of-Waste criteria remains difficult to achieve [

22]. As a result, despite the formal adoption of the waste hierarchy mandated by the EU Waste Framework Directive [

23], emergency regimes and material conditions often prevent its effective implementation, inhibiting the development of local circular material chains [

21].

A further critical issue concerns the loss of material traceability during emergency clearance and handling operations [

22]. As rubble is rapidly consolidated into heterogeneous stocks, information on origin, composition, and construction context is progressively erased, compromising both technical classification and the territorial and cultural specificity of materials. In reconstruction contexts where structural performance must be reconciled with landscape continuity and heritage values, this loss of provenance emerges as a structural barrier to culturally grounded circular practices [

21].

Taken together, these conditions position rubble not merely as a waste stream, but as a multidimensional constraint that delays reconstruction, increases economic and environmental costs, and disrupts socio-material continuity. Recognising this complexity is a necessary step toward reframing rubble management from an emergency-driven liability into a strategic component of circular, territorially grounded reconstruction.

3.2. Rubble as Resource

From an environmental standpoint, reusing and recycling rubble as a secondary raw material can reduce greenhouse-gas emissions associated with quarrying, processing and transporting virgin aggregates, limit landscape degradation in already fragile territories and reduce the demand for new landfill sites [

24]. However, these benefits depend on reprocessing strategies capable of reintegrating materials into construction cycles at comparable or higher levels of performance, rather than limiting reuse to low-grade recycling.

At the economic level, rubble is typically perceived as a cost, as transportation, sorting and disposal place a heavy burden on public budgets, particularly in small municipalities [

25]. When converted into certified secondary aggregates, however, these costs can be partially transformed into local value. In large-scale reconstruction areas, the development of local processing chains can reduce dependence on external suppliers, support specialised enterprises and foster technological clusters focused on debris valorisation.

The social dimension is equally significant. Circular processes based on rubble reuse can generate skilled employment in areas such as materials science, digital surveying and robotic fabrication, helping to counter long-term depopulation trends in inner areas. Moreover, transforming the remains of collapsed buildings into new construction elements carries a strong symbolic charge, enabling communities to re-appropriate the tangible traces of disaster as instruments of regeneration.

Within this framework, upcycling plays a pivotal role. Defined as “a conversion process requiring creativity and design to transform waste into materials or products of higher environmental value” [

26], upcycling in post-earthquake contexts must extend beyond environmental metrics to encompass cultural, social and economic dimensions. While consolidated frameworks for circularity, such as the 10Rs ladder, prioritise minimal-intervention strategies [

27], the heterogeneity and contamination of seismic rubble make transformative processes unavoidable.

Crushing, cleaning and re-fabricating rubble into new components are more energy-intensive than direct reuse, yet they are often necessary to recover meaning and continuity. In post-disaster territories, the exceptional nature of seismic destruction justifies approaches in which environmental optimisation is balanced with symbolic regeneration and territorial cohesion. Upcycling thus shifts from a technical strategy to a cultural and territorial one, capable of generating new material languages that reinterpret inner-area materiality without erasing its origins.

In this perspective, rubble is no longer the inert endpoint of a linear chain from crisis to landfill, but the starting point of a circular and territorially grounded reconstruction model, in which environmental, economic, social and cultural values are negotiated through informed design and digital material practices.

4. Rubble as a Material Bank (RMB): A Digital and Material-Based Method for Post-Disaster Reconstruction

4.1. Urban Mining and the Material Bank Concept

The constraints and opportunities associated with earthquake rubble reveal the limitations of conventional reconstruction paradigms, which remain largely focused on waste removal and material replacement and are therefore insufficient to address the material, environmental, and territorial challenges of post-disaster recovery. Within the broader field of circular construction strategies, concepts such as urban mining and material banks offer resource-centred approaches that can be meaningfully extended to reconstruction contexts, enabling the reintegration of debris into rebuilding processes.

Urban mining refers to the systematic extraction and management of materials embedded in the built environment, shifting attention from geological resources to anthropogenic material stocks [

28]. Although traditionally applied to planned demolition and refurbishment, this approach is particularly relevant in earthquake-affected territories, where destruction generates large volumes of heterogeneous materials within short timeframes, providing a framework to redirect debris from disposal streams toward value-generating reconstruction processes (

Figure 2).

In post-disaster contexts, urban mining introduces a knowledge-based approach in which rubble is understood as a distributed material stock whose properties, composition, and potential applications require systematic assessment. This perspective supports reductions in environmental impacts, facilitates the reintroduction of secondary aggregates into local reconstruction cycles, and contributes to the preservation of material identity through localised reuse. To operationalise this shift, rubble must be treated not as an undifferentiated waste stream, but as a material bank [

29].

4.2. Digitalisation as an Enabler of Circular Reconstruction

While industrial and policy narratives often frame digitalisation as a pathway to optimisation—aimed at reducing time, costs, and logistical complexity [

30,

31]—this productivity-oriented interpretation has increasingly been called into question. Recent studies emphasise the need for digital approaches that also address environmental impacts, labour reconfiguration, and contextual appropriateness, rather than efficiency gains alone [

32,

33].

Within this broader perspective, digital tools do not operate as automated executors of predefined models, but as cognitive infrastructures capable of accommodating variability, irregularity, and incomplete information within design and construction workflows. The objective is therefore not automation per se, but the ability to model, manage, and govern complexity through fabrication-aware and data-rich processes [

34,

35].

Research on circular construction further shows that the reuse of materials across the built-environment system is often constrained less by technical feasibility than by discontinuities in information across actors, phases, and lifecycle stages. In this sense, digitalisation becomes a key enabler of circular processes when it provides shared frameworks for identifying, documenting, and exchanging data on products and materials, as demonstrated by approaches such as the Circular Digital Built Environment and material-passport systems [

36,

37]. Complementary workflows that integrate reality capture, AI-supported identification and classification, and computational design rely on passports as a traceability layer to support material selection, processing, and reintegration [

38].

This enabling role of digitalisation becomes particularly critical in post-disaster reconstruction contexts, where linear workflows and centralised supply chains are poorly aligned with the spatial dispersion of debris, the heterogeneity of materials, and the fragmented nature of affected territories. In such environments, digital infrastructures are not ancillary tools but necessary conditions for activating circular reconstruction practices capable of reconnecting material flows, regulatory requirements, and territorial specificities.

To address the information discontinuities that typically constrain material reuse in these contexts, the Rubble as a Material Bank (RMB) framework adopts a flow-based information model in which rubble batches and fractions are progressively linked to mixes and discrete building elements through persistent identifiers and minimum datasets. In this contribution, the rubble-to-component chain is introduced as the operationalisation of the RMB framework, while the TRAP project is employed to validate selected downstream segments of this chain at prototype level.

4.3. RMB: Framework and Workflow

Rubble as a Materials Bank (RMB) is a research framework for translating repair into contemporary reconstruction practices. In RMB, the objective is to treat debris as a material archive that can be re-characterised, reprocessed, and reintegrated into new construction through verifiable and traceable pathways.

RMB is based on a coupled digital–material workflow in which operations such as survey, sorting and fraction selection, material characterisation, and fabrication are interconnected through structured data. Through this workflow, rubble is progressively transformed from an indeterminate mixed condition into a computable and governable material stream, aligning the approach with the logic of Digital Material Banks (DMBs), where material value is retained by preserving the knowledge required for present and future use.

RMB framework defines a methodological approach for integrating rubble reuse, material characterisation, and data-driven management within post-disaster reconstruction processes. In this study, selected components of the RMB framework are experimentally explored through the TRAP project, funded under the Horizon Europe TARGET-X programme (2024 call), which focuses on digital innovation in the construction sector enabled by 5G infrastructures. While TRAP provides a testbed for specific digital and operational aspects of RMB—such as data connectivity, real-time information exchange, and digitally assisted construction workflows—the overall RMB framework also encompasses material, regulatory, and territorial dimensions that extend beyond the scope of the TRAP experimentation.

4.4. Method and Goal

This section presents the methodological framework adopted to operationalise local circularity in post-disaster reconstruction through the reuse of earthquake-generated rubble. The overall objective is to enable the fabrication of building components of different nature—such as cladding elements, paving units, blocks, and other construction components—by reprocessing rubble-derived materials through extrusion-based additive manufacturing. In this approach, three-dimensional printing is not treated as an end in itself, but as a fabrication strategy capable of accommodating material variability, enabling controlled material transformation, and supporting the production of context-specific building components.

The Rubble as a Material Bank (RMB) framework addresses this objective by defining a rubble-to-component chain: an integrated digital–material workflow that transforms debris from an indeterminate mixed condition into a programmable material stream capable of supporting fabrication processes. Within RMB, the term rubble refers specifically to loose mineral-based construction materials generated by building collapse—such as stones, masonry fragments, bricks, and mixed aggregates derived from mortars and concrete—which constitute the predominant mass fraction of earthquake debris in historic masonry-based settlements. Discrete dry elements (e.g., timber components, steel profiles) are therefore excluded, as they follow different recovery logics, regulatory pathways, and reuse practices.

By delimiting its scope to lapideous and granular material streams, RMB focuses on material flows that are typically considered low-value and difficult to characterise, yet which hold significant potential for circular reintegration when supported by appropriate digital, technical, and regulatory processes. Rather than optimising isolated operations, the rubble-to-component chain frames reconstruction as the orchestration of material, informational, and territorial flows, in which each phase generates data that informs subsequent transformations and preserves material intelligence for future cycles.

Methodologically, the RMB workflow is organised around three interconnected domains—Material, Technology, and Design—linked by a cross-cutting layer of data continuity:

Material, addressing the identification of rubble sources and fractions, the characterisation of lithotypes and key material descriptors, and the documentation of provenance as a proxy for territorial identity;

Technology, defining the digital infrastructure required for passports and Digital Material Banks (DMBs), computational workflows, robotic extrusion supported by sensing and monitoring, and collaborative model exchange;

Design, translating material and technological knowledge into fabrication-aware and reversible components, including toolpath constraints, tolerances, and assembly sequencing aligned with circular design principles;

Data continuity (cross-cutting), ensuring persistent identifiers, logging schemas, and interoperability rules that link material descriptors, process records, and the digital representation of the assembled system end-to-end.

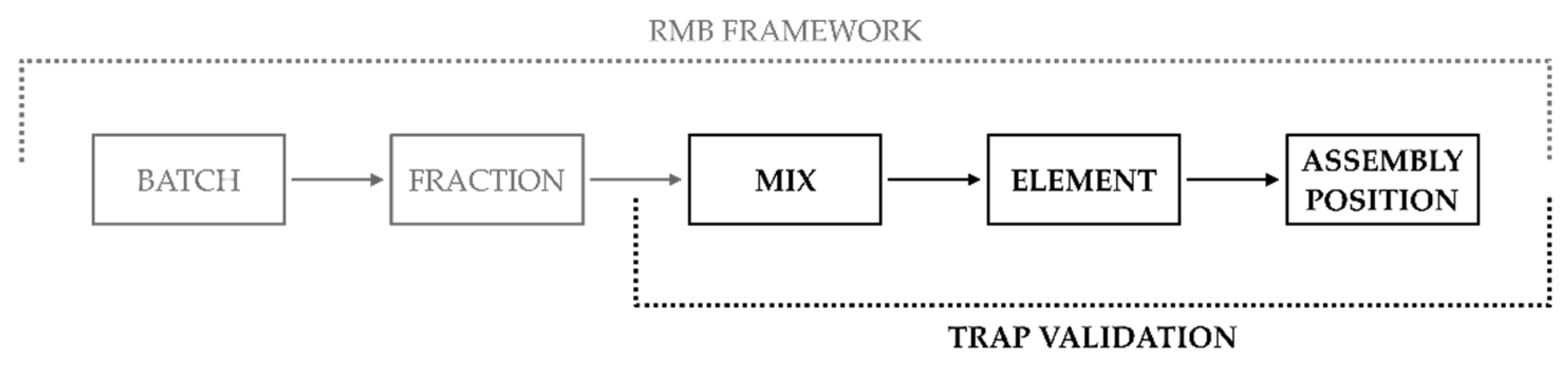

To make this operational, the chain adopts an explicit information architecture inwhich design intent and process evidence travel with the material through nested objects:

batch = a traceable intake unit (source-defined)

fraction = a graded subset derived from processing/selection

mix = a printable formulation associated with a fraction set

element = a fabricated component instance

assembly position = as-built placement reference in the digital model

Upstream sourcing, sorting, and batch-level provenance remain part of the RMB framework but are not validated within the TRAP demonstrator and are treated as out of scope for the experimental evidence reported here (

Figure 3).

4.4.1. Material — Reframing Rubble as a Characterised Resource

Within the RMB framework, the Material domain focuses on transforming post-earthquake rubble from an indeterminate waste stream into a characterised and programmable resource. Seismic rubble is intrinsically heterogeneous, difficult to sort, and potentially contaminated; at the same time, it is closely linked to local lithotypes, construction traditions, and landscape cultures. The methodological objective is therefore to preserve and formalise this material intelligence through systematic characterisation and controlled definition of material fractions.

Material processing along the rubble-to-component chain includes selective sorting where feasible, controlled fragmentation (

Figure 4), and laboratory testing aimed at generating decision-relevant datasets. Typical descriptors comprise granulometric distribution, density, porosity, water absorption, and compositional characteristics, while mechanical indicators may be included to support mix design and performance assessment. These datasets serve a dual role: they support potential regulatory compliance pathways (e.g., End-of-Waste-related requirements) and provide the epistemic basis for fabrication planning and computational modelling.

Given the lack of geometry, purity, and conventional traceability that characterises rubble, component-based material bank models are often unsuitable. The methodology therefore adopts a flow-based Digital Material Bank (DMB) organised around material attributes—physical, mechanical, environmental, and compositional—rather than discrete components. In this framework, datasets function both as scientific records supporting experimental validation and as contextual records preserving knowledge of the collapsed built fabric and its territorial provenance.

4.4.2. Technology — Building the Informational Infrastructure of Transformation

Within the RMB framework, the Technology domain translates characterised material knowledge into actionable fabrication processes by establishing an informational infrastructure capable of governing variability, uncertainty, and heterogeneity—conditions intrinsic to rubble-derived material streams. Technology is therefore not conceived merely as a means of automation, but as the design of data structures, identifiers, and monitoring strategies that support traceability and informed decision-making along the rubble-to-component chain.

At the framework level, digital technologies enable the classification, monitoring, and continuous enrichment of material data through reality capture, rule-based or AI-assisted identification, sensing systems, and structured databases. Processed batches and fractions can be associated with material passports, ensuring traceability and structured data updates as materials progress through selection, mix design, fabrication, and assembly stages.

Extrusion-based robotic fabrication is addressed as a rheology-governed technological infrastructure rather than a generic mechanisation step. When mortars incorporate recycled aggregates, coordinated control of interdependent parameters—such as extrusion pressure or equivalent pumping control, volumetric flow, deposition speed, interlayer time, and environmental conditions—is required. As highlighted in the 3D Concrete Printing literature, these coupled variables directly affect printability (

Figure 5), mechanical performance, and failure modes, particularly in the presence of non-standard aggregates [

32,

39].

The fabrication phase is supported by PLC-controlled mixing/pumping/dosing systems—integrated and automated units governed by a Programmable Logic Controller (PLC) that ensure coordinated control over material preparation and extrusion—combined with environmental monitoring. Fabrication generates process data (e.g., dosage proxies, flow control variables, pump torque or pressure where available, temperature and humidity, and timestamps), which can be logged and linked to element identifiers. Where proprietary parameters cannot be disclosed, proxy variables and observed ranges are reported to support comparability. Together, these datasets form the backbone of an evolving digital twin, recording geometry, material biography, and fabrication history at the element level.

4.4.3. Design — From Knowledge-Rich Matter to Reversible Components

The Design domain represents the translational interface through which material characterisation and technological control are converted into architectural form. Design is treated as a knowledge-driven process integrating material intelligence (granulometry, rheology proxies, mechanical indicators), fabrication constraints (bead geometry, anisotropy, buildability), and reconstruction-specific requirements (structural behaviour, compatibility with existing masonry logics, reversibility).

Computational design tools are used to integrate heterogeneous inputs and negotiate constraints rather than to impose predefined typologies. Within this approach, discrete dry-assembled and reversible components are developed to operate within heritage-sensitive wall systems while meeting contemporary performance requirements. Geometries, joints, and cavities can be defined to facilitate assembly, accommodate reinforcement where required, and enable future disassembly, aligning with Design for Disassembly and Design for Recycling principles [

40,

41].

Each component is conceived as both a physical element and an informational asset. Through persistent identifiers, it is linked to its material passport, fabrication parameters, and assembly position within the digital twin. This dual status is essential to maintain traceability across the lifecycle and preserve the conditions for future adaptation, reuse, and material recirculation.

5. The TRAP Experiment. A Controlled Cyber–Physical Workflow

The TRAP test case implements the downstream segment of the RMB rubble-to-component chain (mix → element → assembly position) as a controlled cyber–physical workflow. The experimentation focuses on the fabrication of blocks (

Figure 6) for a dry-assembled wall system, but its primary objective is not the optimisation of the building product itself. Rather, the experiment is designed to investigate the processual dimension of post-disaster reconstruction, addressing how material, data, and operational information can be coordinated across design, production, and assembly stages.

The workflow integrates parametric design and a BIM-based digital twin, robotic extrusion of discrete blocks, production monitoring with structured data logging, and Mixed Reality (MR) tools supporting storage management, assembly sequencing, and logistics verification. The experiment was conducted within the TARGET-X Trial Platform as a connectivity-enabled testbed, where the BIM digital twin functions as the coordinating reference model for distributing geometry and attribute data among design, fabrication, and assembly actors.

According to the validation boundary defined, the methods reported here address only downstream mechanisms and their measurable outputs. Upstream rubble sourcing, site-scale sorting, and batch-level provenance governance remain outside the experimental scope of TRAP and are therefore not used as evidence in this study.

5.1. Material Inputs, Mix Classification, and “Material Descriptor” Datasets

The TRAP demonstrator employed a printable cement-based formulation incorporating recycled aggregates, specifically developed for the robotic extrusion of modular blocks. Within the project reporting, the sustainability inventory of the printed material is documented using a cement specifically formulated for 3D printing as the binder and recycled aggregate as the primary granular input. The recycled aggregate fraction accounts for 30% of the printable mixture by mass.

To ensure traceable and comparable reporting at the prototype scale, this study organises material inputs through a minimum material-descriptor dataset, intended to support continuity and interpretability rather than full material certification. Each tested condition is therefore described using a limited and consistent set of descriptors, including:

the binder system identifier (3D-printing-specific cement) and declared mix family;

the aggregate class (recycled aggregate), including the maximum size class adopted in the demonstrator and in the printing tests reported in the appendices;

the declared recycled content of the printable formulation;

minimum available physical descriptors derived from experimental records (e.g., density values used for pre-production calculations).

This descriptor-based approach provides a pragmatic basis for linking material composition to downstream fabrication indicators and sustainability accounting, while remaining compatible with the exploratory and process-oriented nature of the TRAP experimentation.

5.2. Software Infrastructure and Information Model (Data Continuity Implementation)

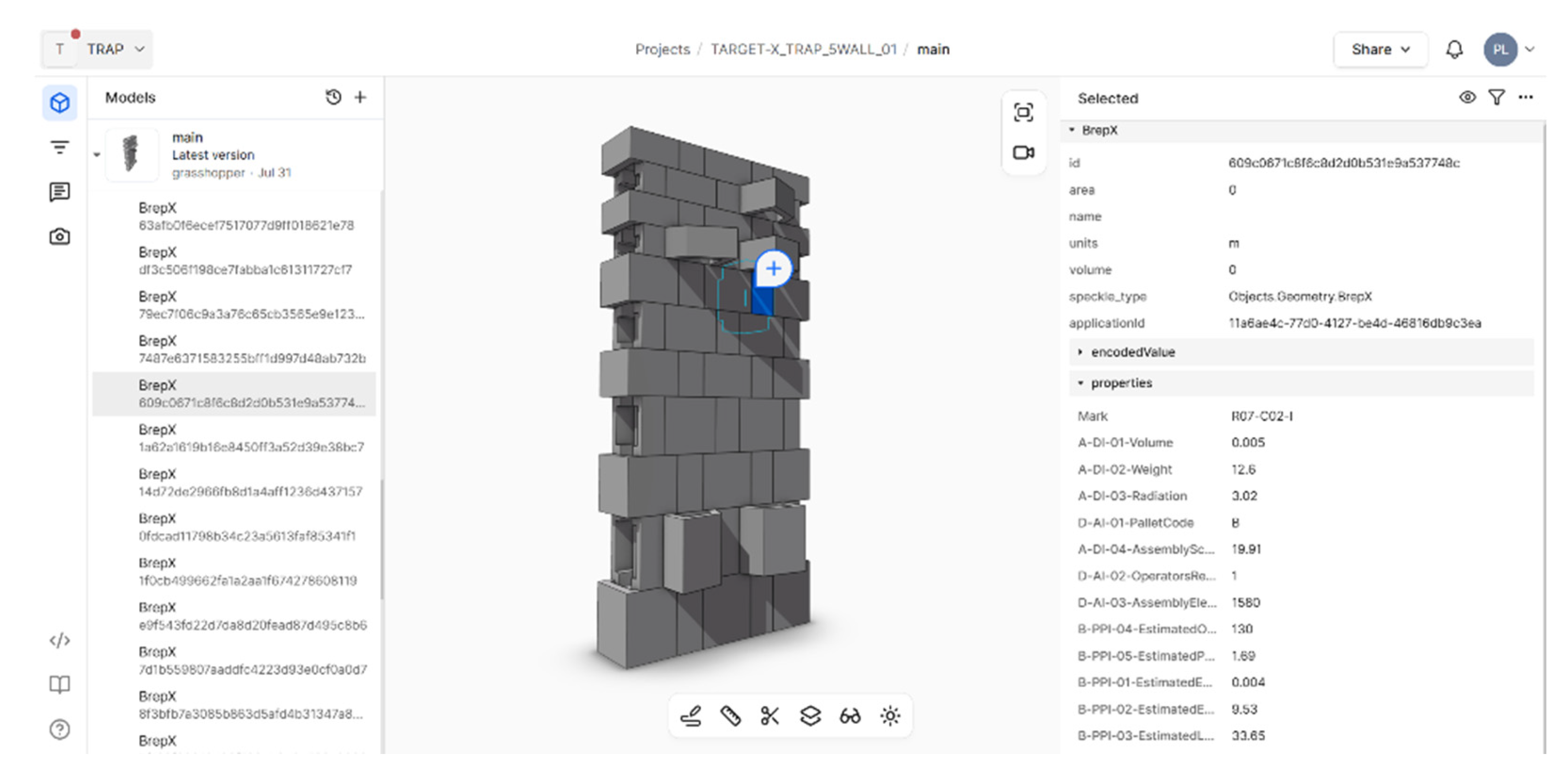

A BIM-based digital twin was adopted as the shared reference model for coordinating design, production, and assembly information across the TRAP workflow. Within this environment, data continuity was implemented through an integrated information model designed to maintain consistent links between digital representations and physical elements along the downstream rubble-to-component chain.

The information model relies on two coupled mechanisms: an element identification strategy that uniquely maps each physical block to a corresponding digital object and its intended assembly position, and a structured indicator schema that associates pre-production estimates, production logs, and assembly/logistics attributes with the same element identifier. Together, these mechanisms ensure traceability across stages and enable the aggregation and comparison of datasets generated at different points in the workflow.

5.2.1. Element ID Encoding and Mapping to Assembly Positions

Element-level traceability in TRAP is enabled through a positional–typological coding system that combines row and column indices with a block typology label (e.g., R08–C01–I). Row (Rxx) and column (Cyy) indices map each block to its intended position within the wall layout, while the typology letter identifies the block family as defined in the parametric design model.

The code is generated within the parametric environment, embedded as a parameter in the BIM-based digital twin, and used as a unique lookup key to associate production records, monitoring data, and assembly attributes with each block instance. This encoding strategy enables deterministic positioning, supports downstream logistics reasoning, and provides a stable reference for linking heterogeneous datasets.

5.2.2. Model Exchange and Synchronisation

Parametric modelling and workflow control were developed in Rhino/Grasshopper, which acted as the generative environment for element geometry and identifier assignment. Model and data exchange across heterogeneous platforms were implemented via Speckle (

Figure 7) - a cloud-based interoperability platform - used as a synchronisation layer enabling the iterative distribution of both geometry and per-element attributes.

Within this architecture, Grasshopper operates as the source of parametric logic and ID generation, while Speckle propagates synchronised updates to the BIM-based digital twin and to Mixed Reality (MR) applications that consume the same attributes during storage and assembly simulations. This configuration supports bidirectional updates and maintains consistency across design, production, and downstream operational environments without requiring direct file-based interoperability.

5.3. Pre-Production Computation and Indicator Definition (PPI)

TRAP distinguishes pre-production indicators (PPI), derived from the digital model and toolpath estimates, from production indicators (PI) measured and logged during execution. PPI are computed using the production-setting parameters declared in the project development report—namely layer height (13.0 mm), nozzle diameter (20.0 mm), concrete density (2400 kg/m³), nominal mass flow rate (6.3 kg/min), and robot speed (70–200 mm/s). Pre-production computations estimate:

printing time, based on toolpath length and speed assumptions;

extruded volume, calculated either from mass flow rate and time or from layer cross-sectional area and toolpath length;

extruded mass, obtained from volume–density relationships;

target geometric descriptors, such as element height derived from layer height and number of layers.

These indicators establish a quantitative baseline against which production measurements and logs are compared, enabling the assessment of deviation and supporting the interpretation of process stability and repeatability.

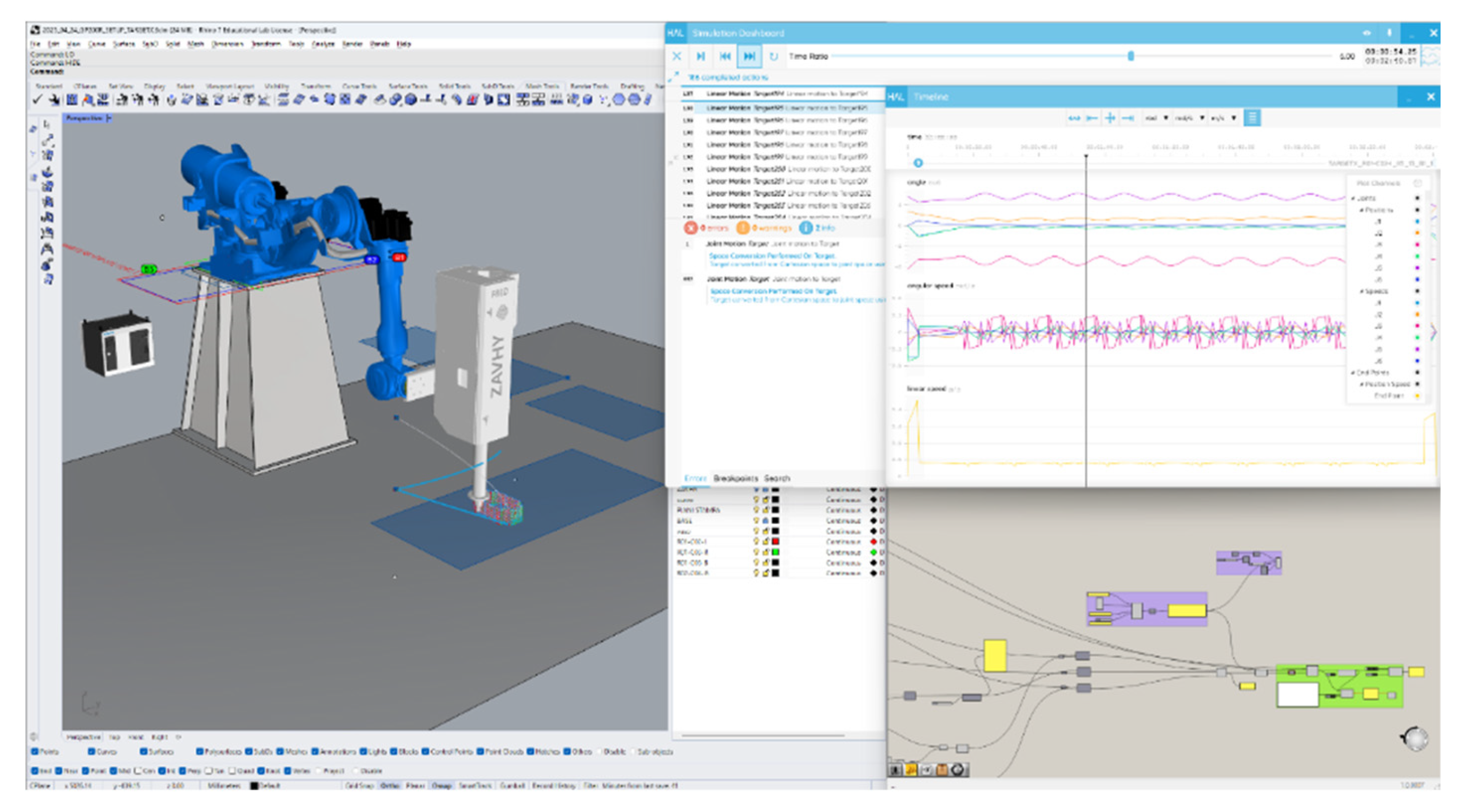

5.4. Robotic Production Cell and Execution Environment

Robotic fabrication was carried out within an integrated production cell combining a Yaskawa industrial robot for toolpath execution with an extrusion system designed for cement-based printing incorporating recycled aggregates and supplied by a mixing/pumping architecture (

Figure 8). Toolpaths were simulated and verified in Rhino/Grasshopper using HAL Robotics (

Figure 9) - a plugin for robotic programming and simulation - prior to execution, supporting collision avoidance, parameter calibration, and pre-production computations.

Following the TRAP confidentiality framework, the methods report controllable parameters and observed ranges using a process-window approach, rather than disclosing proprietary thresholds. Subsystem-level settings (mixer, extruder, doser, pump) are treated as internal control variables and are reported only in terms of variable categories and adjustment logic where necessary for scientific interpretation.

5.5. Production Monitoring, Logging, and “Process-Window” Evidence Acquisition (PI)

Production monitoring was implemented through a PLC/HMI architecture, integrating dosing, mixing, water management, and extrusion subsystems. The PLC provides deterministic real-time control of the process, while the HMI supports operator interaction, supervision, and on-site process adjustment. Data were recorded with timestamps and exported in standard formats (CSV/JSON) to support both process interpretation and sustainability accounting, and to enable linkage to element IDs in the digital twin.

5.5.1. Logged Data Categories

Production-phase data were organised into two main dataset categories.

The first includes sustainability-oriented datasets supporting cradle-to-gate accounting, such as material quantities, water consumption, electricity proxies, process duration and cycle times, and transport assumptions where relevant for inventory construction.

The second category comprises process and quality-control datasets used to interpret print stability and execution behaviour. These datasets include time-structured operation logs and measurable outcomes that can be compared against pre-production expectations, such as actual printing time, observed layer or bead-width consistency, and recorded element weights where available.

In this study, the process window is defined as the combination of declared setpoints or admissible ranges for controllable parameters and the corresponding execution outcomes demonstrating stable material deposition (e.g., continuous layer formation without collapse) under the tested conditions..

5.5.2. Association of Logs to Element IDs

Element-level traceability requires associating each production record with the corresponding element ID. In TRAP, this association is implemented by embedding the element ID within the digital twin object and by structuring production records to be linked to the same ID during data integration. Element-level segmentation of logs was performed through operator-defined cycles, and every single file was launched on the robot

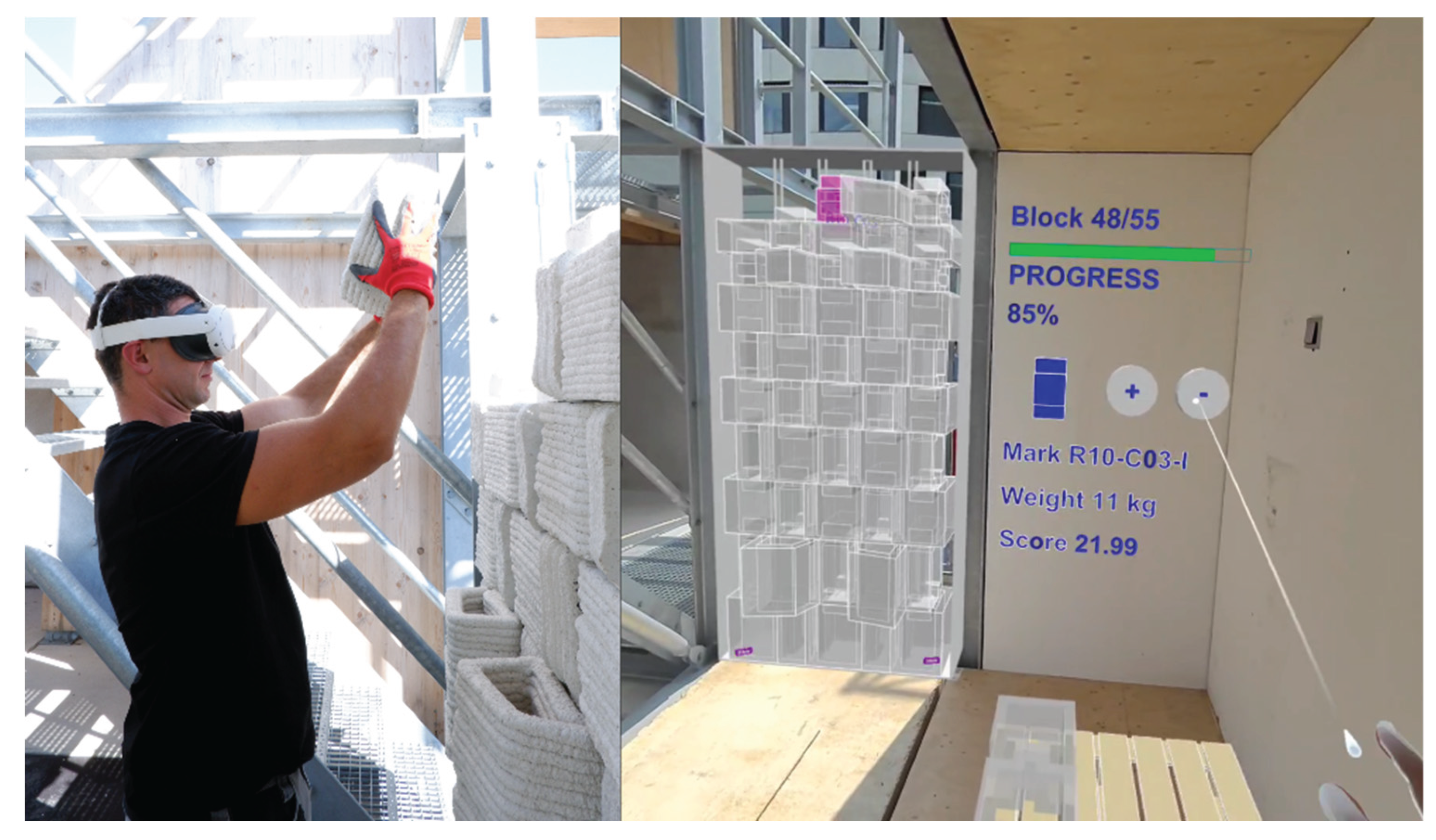

5.6. MR-Assisted Storage, Assembly Sequencing, and Logistics Verification

Mixed Reality (MR) was employed to support downstream handling and assembly tasks by visualising the digital twin and accessing element-level attributes—such as IDs, pallet codes, and weight-related handling parameters—during simulated storage and assembly operations (

Figure 10). Two MR configurations were implemented in TRAP. The first used HoloLens 2 with Trimble Connect to visualise IFC-based BIM models and attributes, with spatial alignment achieved through printed QR codes placed at known reference points. The second adopted a Fologram workflow integrated with Meta Quest headsets, enabling a more flexible MR environment with real-time streaming from Rhino/Grasshopper and synchronisation via Speckle, supported by alignment through printed QR codes and ArUco markers.

MR procedures included spatial verification of the wall model within the testbed area, full dry-run simulations of block-by-block assembly sequencing, and simulated positioning of pallets and components for logistics reasoning. In addition, MR-based remote support scenarios—such as real-time instructions, action recording, and video streaming—were tested. Latency observed during high-bandwidth operations (e.g., model updates and streaming) was documented as a relevant limitation for potential field deployment.

5.7. Assembly/Logistics Indicators and Traceability Completeness Metrics

Assembly-related datasets were integrated into the digital twin to support traceability and logistics/safety management. The project reporting defines assembly indicators (AI, letter “D”) compiled at element level, including:

D-AI-01 PalletCode: the identifier of the pallet in which the block is positioned;

D-AI-02 OperatorsRequired: the number of people needed to lift the block manually, calculated using a maximum load of 25 kg per operator;

D-AI-03 AssemblyElevation: the elevation in mm at which the block is to be installed, used to reason about work-at-height or lifting requirements.

Traceability completeness is evaluated as the coverage of persistent IDs and linked metadata across the downstream chain, i.e., the extent to which each element has: (i) an ID defined in the parametric model and embedded in the digital twin, (ii) linked pre-production and production datasets, and (iii) an assembly-position reference and logistics attributes retrievable in MR.

5.8. Preliminary Cradle-To-Gate LCA Method

A preliminary cradle-to-gate LCA was carried out to convert production inventories into environmental impact indicators under a defined functional unit and system boundary. The functional unit is 1 m³ of printed material, while the system boundary includes material production (binder and aggregates), transport of inputs to the production site, electricity consumption for printing and auxiliary processes, packaging, water use, and disposal of process waste, as documented in the project reporting. The assessment is intended as prototype-scale environmental profiling aligned with the demonstrator configuration and is not presented as an EPD-ready result.

5.9. Connectivity, Confidentiality, and Data Availability

TRAP was implemented as a connectivity-enabled workflow supporting synchronisation across design, production, storage/assembly, and remote supervision. Project documentation indicates that MR streaming and model-update operations are sensitive to latency and bandwidth and therefore benefit from optimised network architectures, such as edge processing and simplified network configurations.

In accordance with industrial confidentiality constraints, this manuscript reports only non-sensitive parameter categories, value ranges, and decision criteria sufficient for scientific interpretation, while proprietary thresholds and exact control values are not disclosed. Where feasible, aggregated or anonymised datasets—such as per-element indicators excluding sensitive machine settings—are provided as supplementary material.

6. TRAP — Experimental Validation of the Chain

Within the proposed Rubble as a Material Bank (RMB) framework, the TRAP (Remote-controlled Assembly Process) project provides an experimental validation of the downstream segment of the rubble-to-component chain, with specific focus on the Technology–Design interface. Funded under the European TARGET-X programme (Trial Platform for 5G Evolution), TRAP operates as a cyber–physical testbed aimed at assessing the feasibility, robustness, and limitations of digitally integrated workflows for construction processes under real-world, connectivity-enabled conditions. In this context, TRAP does not address the full scope of rubble management but concentrates on the phases in which characterised material streams are transformed into fabricable elements and subsequently assembled through digitally coordinated processes.

The value of the TRAP experimentation lies primarily in the validation of the workflow, rather than in the architectural outcome. The Green5Wall dry-assembled wall system is therefore conceived as a demonstrator, intended to test the operability, internal coherence, and critical thresholds of the proposed rubble-to-component chain, rather than as a finished construction solution designed for direct replication. The experiment investigates how rubble-derived aggregates, once characterised and digitally governed, can be reprocessed into discrete components through extrusion-based fabrication and assembled within a reversible system.

A first level of validation concerns the alignment between digital design intent and material behaviour. Parametric design tools were used to define component geometries, toolpaths, and assembly sequences based on material descriptors and simulated fabrication constraints. These digital assumptions—relating to layer geometry, tolerances, and assembly fit—were then confronted with the observed behaviour of rubble-based mortars during robotic extrusion. Deviations between expected and actual performance, including variations in dimensional accuracy, surface quality, and buildability, were captured and documented within the digital twin. This comparison confirms the role of digital design not as a prescriptive model, but as a mediating layer capable of accommodating uncertainty and negotiating the intrinsic variability of recycled aggregates.

A second validation dimension addresses the capacity of robotic extrusion systems to operate with variable, rubble-derived feedstocks. Unlike industrial mortars with tightly controlled compositions, mixes incorporating recycled aggregates exhibit variability in granulometry, absorption, and rheological response. Within TRAP, robotic fabrication was executed in a dedicated production cell equipped with a six-axis industrial robot and an extrusion system capable of processing mortars containing recycled aggregates up to 8 mm. Key process parameters—such as extrusion flow rate, deposition speed, interlayer timing, and environmental conditions—were monitored and adjusted in real time. The experimentation demonstrates that stable deposition can be achieved despite material heterogeneity, provided that fabrication parameters are continuously calibrated based on material response and process feedback.

A third aspect of validation concerns the role of digital twins and data continuity in maintaining traceability across fragmented workflows. Each fabricated block was assigned a persistent identifier linking its digital representation to material descriptors, pre-production estimates, and production logs. Process data—including flow-related proxies, pump and extrusion metrics, and environmental records—were synchronised with the digital twin, enabling element-level correlation between fabrication conditions and observed performance within the assembled system. This continuity supports quality control, post-fabrication assessment, and the potential for future disassembly and reuse, reinforcing the role of digital infrastructures as enabling conditions for circular reconstruction.

A final validation dimension explores the integration of digitally assisted assembly processes. Assembly of the Green5Wall prototype was supported through Mixed Reality (MR) interfaces connected to the same digital twin used for design and fabrication. MR tools provided placement guidance, sequence verification, and tolerance control, demonstrating how digitally mediated assembly can compensate for geometric variability and support dry, reversible construction systems. The connectivity framework provided by TARGET-X enabled synchronisation between design models, fabrication data, and on-site operations, allowing real-time supervision and coordination across stages.

TRAP does not exhaust the rubble-to-component chain. Upstream phases—such as large-scale debris management, selective deconstruction, and full regulatory consolidation—remain outside the scope of the experiment. Nevertheless, the project validates a central hypothesis of the RMB framework: once characterised and digitally governed, rubble can be transformed into a knowledge-rich material stream capable of supporting fabricable, reversible, and territorially grounded construction processes. At the same time, TRAP exposes technical, organisational, and regulatory limits, providing a critical basis for refinement, scaling strategies, and future research on circular reconstruction in earthquake-affected inner territories.

7. Results and Discussion — How Far Are We?

The experimental outcomes of the TRAP project provide a basis for critically assessing the distance between current post-disaster reconstruction practices and a transition toward circular, digitally enabled, and territorially grounded models. Despite growing recognition of the built environment as a reservoir of material resources and cultural knowledge [

2,

44], post-earthquake reconstruction still predominantly follows linear logics, in which collapse marks the beginning of a waste-management trajectory rather than a regenerative process.

Within this context, the experimental validation of the rubble-to-component chain offers partial but concrete evidence that this paradigm can be reconfigured, particularly in inner territories where seismic events generate what Clemente and Salvati [

9] describe as interrupted landscapes, simultaneously affecting material continuity, spatial legibility, and social cohesion.

7.1. Digital Innovation as an Enabler—Not a Simplifier—of Circular Reconstruction

The TRAP experiment confirms that digital innovation enables circular reconstruction not by simplifying complexity, but by rendering it governable. Robotic extrusion, sensor-informed process control, and digital twin infrastructures demonstrate that material heterogeneity—traditionally considered a limiting factor—can be incorporated as a computational variable within fabrication workflows.

The feasibility of printing mortars containing rubble-derived aggregates shows that uncertainty associated with recycled materials can be managed through real-time calibration, particularly when parameters such as granulometry proxies, extrusion flow, deposition speed, and environmental conditions are continuously monitored and logged. This finding aligns with established positions in computational fabrication research, which frame digital technologies as mediating systems capable of negotiating material behaviour rather than merely executing predefined forms (Gramazio & Kohler, 2008; Menges, 2015).

In this sense, digital tools do not “optimise” reconstruction in an industrial sense; rather, they enable reconstruction under conditions of fragmentation, resource scarcity, and heritage sensitivity typical of Apennine inner areas, supporting forms of material repair that incorporate—rather than erase—the material consequences of collapse.

7.2. Material and Regulatory Bottlenecks: The Obstacles Ahead

Despite these results, several structural bottlenecks remain evident.First, the processing cost of rubble-derived aggregates remains high. Contamination, soil admixture, and irregular granulometry require washing, screening, and repeated sorting, increasing both energy demand and operational complexity, consistent with previous analyses of post-disaster debris management (Cellini, 2021).

Second, the instability of material flows poses a major challenge. Earthquake rubble emerges suddenly and unpredictably, conflicting with the stable input assumptions underpinning most recycling plants and End-of-Waste certification pathways.

Third, technological limitations of current extrusion systems constrain geometric resolution. While the TRAP blocks support dry and reversible assembly, extrusion-based processes do not yet reproduce the stereotomic richness or morphological variation characteristic of historic masonry, echoing concerns raised by Picon (2024) regarding the risk of material homogenisation.

Finally, regulatory misalignment persists. Seismic codes, heritage prescriptions, and waste regulations remain compartmentalised, offering limited support for hybrid workflows in which rubble is transformed, certified, and reintegrated into construction within the same territorial cycle. These constraints do not invalidate the process, but clearly define its present operational boundaries.

7.3. Compatibility with Territorial Identity and Architectural Continuity

A key question emerging from the experiment concerns the compatibility of rubble-derived components with the identity of historic settlements. The TRAP demonstrator suggests that continuity can be maintained when material provenance is documented, chromatic responses reflect local lithotypes, and modular, reversible geometries resonate with long-standing seismic construction logics.

At the same time, limitations are evident. The surface regularity associated with extrusion, mechanical anisotropy, and reduced textural variation introduces perceptual and cultural distances from traditional stonework. These results indicate that circular reconstruction should not aim at literal replication, but at contextual continuity, in which technological transformation is negotiated within the material logic of place rather than imposed upon it.

7.4. A Transitional Stage: From Prototype to Systemic Model

Taken together, the results position the rubble-to-component chain at a transitional stage. The conceptual framework is supported by experimental validation at component and workflow levels, but not yet by systemic or territorial-scale implementation.

At present, the chain can be considered partially validated: material characterisation protocols are available but require standardisation; computational workflows for modelling, fabrication, and traceability are operational; reversible block families have been successfully produced and assembled; and digital twin infrastructures demonstrate that material biographies can persist across lifecycle stages. However, scaling beyond the prototype requires conditions that extend well beyond the laboratory, including regulatory frameworks recognising transformed rubble as a resource, mobile processing infrastructures suitable for mountainous territories, reduced energy costs for aggregate preparation, and stronger alignment between digitally fabricated components and the cultural landscapes of Italy’s diffuse settlement system.

7.5. How Far Are We?

The results indicate that circular reconstruction based on rubble reuse is technically feasible, but not yet institutionally consolidated, economically stable, or culturally embedded. In Technology Readiness Level (TRL) terms, the rubble-to-component chain currently lies between TRL 4 and TRL 6: validated in controlled settings and partially demonstrated in relevant environments, but not ready for full territorial deployment.

Nevertheless, the trajectory is clear. The experiment reframes rubble from an inert residue of destruction into a knowledge-rich material stream; demonstrates the role of digital tools as cognitive infrastructures for managing uncertainty; and suggests that reconstruction can evolve into a project of continuity rather than replication.

7.6. Towards a New Material Ecology of Reconstruction

The broader implication is that reconstruction in fragile inner territories can no longer be conceived as an exceptional response requiring external resources alone. It must instead evolve into a material ecology, in which local matter, digital intelligence, cultural memory, and reversible design converge to support long-term territorial resilience.

If rubble represents the last material layer of collapsed settlements, rebuilding with rubble—characterised, transformed, and digitally governed—means weaving past and future into a continuous material narrative. This approach is neither nostalgic nor technologically deterministic; it operationalises the condition of polycrisis, as theorised by Morin and Kern, by framing reconstruction as a materially grounded and context-sensitive response to contemporary landscape transformations [

43].

8. Conclusions

This study proposes a rethinking of post-disaster reconstruction in earthquake-affected territories, demonstrating that—under defined technical, digital, and regulatory conditions—rubble traditionally treated as waste can instead operate as an active resource within territorially grounded circular-economy models. Through the definition and partial experimental validation of the rubble-to-component chain, and its implementation within the TRAP project, the research provides evidence that digitally governed fabrication workflows can transform heterogeneous debris into traceable and fabricable construction components.

The findings highlight three interrelated dimensions through which circular reconstruction becomes feasible. First, rubble can be redefined as a qualified material resource. When supported by systematic material characterisation, rubble-derived aggregates can meet contemporary construction requirements while retaining links to local lithotypes and construction cultures. In historic inner-area contexts, material provenance thus functions not only as a technical descriptor but also as a carrier of cultural continuity, extending the material identity of collapsed settlements into future building cycles [

9,

44].

Second, the research demonstrates that digital and robotic workflows enable the governance of material heterogeneity under post-disaster conditions. Robotic extrusion, sensor-based monitoring, structured data logging, and digital twins together form a knowledge infrastructure capable of absorbing uncertainty and regulating fabrication processes with a degree of adaptability unattainable through conventional approaches. This confirms emerging perspectives in computational fabrication that frame digital tools as mediators of material behaviour rather than executors of predefined forms [

34,

45,

46], supporting a shift from standardised and resource-intensive reconstruction toward localised, adaptive, and knowledge-rich practices.

Third, the development of reversible, dry-assembled components fabricated with rubble-derived mixes illustrates how material and digital intelligence can be translated into architectural systems compatible with heritage-sensitive contexts. While these components do not replicate the stereotomic complexity of traditional masonry [

12], their reversibility and assembly logic suggest a hybrid architectural language capable of negotiating continuity and transformation without resorting to literal reconstruction.

At the same time, the study identifies critical conditions for broader adoption. Regulatory frameworks must evolve to recognise transformed rubble as a construction resource; mobile or near-site processing infrastructures are required for fragmented mountain territories; professional skills and local SMEs must be supported in adopting digital workflows; and cultural acceptance of new material expressions must be addressed through participatory processes. Without these conditions, rubble-based circular reconstruction risks remaining confined to experimental settings.

Beyond the Central Italy case, the proposed approach is relevant to territories worldwide characterised by strong material identities and structural vulnerability. In an era marked by climate stress, resource scarcity, and demographic contraction, reconstruction can no longer be conceived as a short-term response to damage but as an opportunity to reduce extraction, shorten supply chains, and reinforce territorial resilience. This research demonstrates that rubble—when characterised, processed, and digitally governed—can shift from being the endpoint of disaster to becoming a catalyst for regeneration.

In this perspective, rubble represents not the inert residue of collapse but the starting point of a new material ecology, in which digital intelligence, cultural memory, and reversible design converge to support sustainable transformation. Future research will focus on extending the rubble-to-component chain from prototype validation to territorial-scale implementation, including regulatory development, community-centred design strategies, mobile processing platforms, and performance assessment at building and settlement scales. Through this progression, the proposed framework may evolve into a replicable model for circular reconstruction capable of supporting architecture that not only rebuilds, but regenerates.

9. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

The limitations of this study are consistent with its exploratory and process-oriented focus. The rubble-to-component chain has been validated at prototype scale and under controlled conditions. While TRAP demonstrates the feasibility of digitally governed fabrication with rubble-derived aggregates, it does not address upstream phases such as large-scale debris logistics, selective deconstruction, or in-situ processing in operational post-disaster environments.

Material characterisation was applied to a limited set of rubble fractions and mix designs. Further investigation is required to assess long-term durability, structural performance, and environmental impacts through extended testing campaigns and full life-cycle assessments. Similarly, the technological validation reflects the constraints of a specific robotic cell and software ecosystem; transferability to alternative hardware configurations, automation levels, and fabrication contexts remains to be demonstrated.

From an architectural perspective, the experimentation focused on a single family of reversible wall components. Issues related to typological diversification, integration with other building systems, and performance at building and settlement scales are only partially explored. In addition, the study did not systematically involve local communities, institutional actors, or regulatory bodies, leaving questions of social acceptance, governance, and policy alignment largely conceptual.

Future research will therefore focus on four aligned directions. At the material and environmental level, the framework will be extended to a broader range of rubble fractions, binders, and admixtures, supported by durability testing and comparative environmental assessments. At the technological level, the rubble-to-component chain will be adapted to different robotic platforms and mobile or semi-mobile fabrication systems suitable for fragmented and mountainous territories. At the design level, the component catalogue will be expanded beyond wall systems, with evaluations at building and settlement scales. Finally, at the socio-institutional level, co-designed pilot projects involving public authorities, local communities, SMEs, and regulatory bodies will be developed to test acceptance and inform the evolution of regulatory frameworks.

Through these developments, the rubble-to-component chain may progress from a validated prototype toward a systemic and transferable model for circular reconstruction, consistent with the material, cultural, and territorial challenges outlined in the Conclusions.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. Introduction. (Re)Build it circular – Roberto Ruggiero; The Materiality of Reconstruction -Roberto Ruggiero; The Dual Nature of rubble – Pio Lorenzo Cocco; Rubble as a Material Bank (RMB): A Digital and Material-Based Method for Post-Disaster Reconstruction – Pio Lorenzo Cocco; The TRAP Experiment. A Controlled Cyber–Physical Workflow – Roberto Cognoli; TRAP — Experimental Validation of the Chain – Roberto Cognoli; Results and Discussion — How Far Are We?- Roberto Cognoli; Conclusion – Roberto Ruggiero; Limitations and Directions for Future Research – Pio Lorenzo Cocco.

Funding

“This research was funded by TARGET-X Program, Subgrant agreement no 21_TARGET-X_2OC TARGET-X 2 nd Open Call, TRAP project”.

References

- O'Grady, T.M.; Minunno, R.; Chong, H.-Y.; Morrison, G. Design for disassembly, deconstruction and resilience: A circular economy index for the built environment. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 175, 105847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rau, T.; Oberhuber, S. Material Matters: The Past and Future of Materials in Sustainable Architecture; Terra Publishers: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 9–34. [Google Scholar]

- Pomponi, F.; Moncaster, A. Circular economy for the built environment: A research framework. J. Clean. Prod 2017, 143, 710–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisellini, P.; Ripa, M.; Ulgiati, S. Exploring environmental and economic costs and benefits of a circular economy approach to the construction and demolition sector. A literature review. Jour. of Cl. Prod. 2017, 178, pp 618–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjiang, S.; Cao, Q.; Wei, L. A conceptual framework integrating “building back better” and post-earthquake needs for recovery and reconstruction. Sustainab. 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, K. The Circular Economy: A Wealth of Flows; Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Cowes, UK, 2015; pp. pp 41–70. [Google Scholar]

- Faleschini, F.; Zanini, M.A.; Hofer, L.; Zampieri, P. Sustainable management of demolition waste in post-quake recovery processes: The Italian experience. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2017, 24, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norberg-Schulz, C. Genius Loci: Towards a Phenomenology of Architecture; Rizzoli: New York, NY, USA, 1980; pp. 11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Clemente, M.; Salvati, L. ‘Interrupted’ landscapes: Post-earthquake reconstruction in between urban renewal and social identity of local communities. Sustainab. 2017, 9, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, R.; Ruggiero, R. Re-thinking Re-construction: New design strategies for the reconstruction after natural disasters. A local research experience for a global topic. In Architecture across Boundaries: 2019 XJTLU International Conference; KnE Social Sciences: Dubai, UAE, 2019; pp. 439–449.

- Chinellato, F.; Petriccione, G. Types and technologies of rural mountain architecture in the Northeast of Italy: Three valleys compared. In Memoria e Innovazione / Memory and Innovation; Dassori, E., Morbiducci, R., Eds.; EdicomEdizioni: Monfalcone (GO), Italy, 2022; pp. 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Ruggiero, R. La città dell'attesa tra emergenza e ricostruzione. Agathon 2018, 4, 146–159. [Google Scholar]

- Cognoli, R.; Ruggiero, R.; Cocco, P.L. From Debris to the Data Set (DEDA): A Digital Application for the Upcycling of Waste Wood Material in Post Disaster Areas. In Design for Sustainability; Barberio, M., et al., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 647–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picon, A. The materiality of architecture: Between the rise of the Digital Age and the advent of the Anthropocene. Perspectives in Architecture and Urbanism 2024, 1, 100019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernabei, L.; Gulli, R.; Predari, G.; Mochi, G. Resilience strategy after 2016 Central Italy earthquake in

historical centres: Seismic vulnerability assessment method of traditional masonry buildings. In Proceedings

of the 3rd RILEM Spring Convention and Conference, Ambitioning a Sustainable Future for the Built Environment:

Comprehensive Strategies for Unprecedented Challenges, Guimarães, Portugal, 2021; Springer: Cham,

Switzerland, pp. 239–251. [CrossRef]

- Ventura, S. Storia di una ricostruzione. LʹIrpinia dopo il terremoto; Rubbettino: Soveria Mannelli, Italy, 2020;

pp. 161‐220

- Mashiko, T.; Franz, G.; Uchida, N.; Ariga, T.; Satoh, S. The mutual relationship between established process of reconstruction governance and implemented process of reconstruction project: A focus on L’Aquila city 10 years after the Abruzzo earthquake. Japan Arch. Rev. 2021, vol. 4(issue 4), 633–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallitano, G. Ricostruzione post-terremoto e identità nuove. I cinquant'anni del Belice. In Proceedings of the Conference on Post-Disaster Reconstruction, 2017; University of Palermo: Palermo, Italy; pp. 163–167. [Google Scholar]

- Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri; Dipartimento della Protezione Civile. Indicazioni operative per la gestione delle macerie a seguito di evento sismico. Available online: https://www.protezionecivile.gov.it/static/18a2bbfcd6c913386a2d6acc9affd486/io-17112023-3.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Regione Marche. Piano Regionale di Gestione dei Rifiuti. Piano di gestione delle macerie derivanti dal crollo e dalla demolizione di edifici ed infrastrutture a seguito di un evento sismico. Available online: https://www.regione.marche.it/portals/0/Ambiente/Rifiuti/All_A.4_PRGR%20PARTE%20IV%20PIANO%20MACERIE_adoz%202024-10_signed_signed.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2025).

-

Pacheco, J.N.; de Brito, J.; Lamperti Tornaghi, M. Use of Recycled Aggregates in Concrete: Opportunities for

Upscaling in Europe. Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2023. Available online:

https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2760/144802 (accessed on 8 December 2025). [CrossRef]

- Dipartimento della Protezione Civile. I numeri del sisma in Centro-Italia. Available online: https://emergenze.protezionecivile.gov.it/static/f438b5ebc904a11a47dd5db891db0fbb/Relazione_di_aggiornamento_numeri_dell_emergenza__22_agosto_2018_.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- European Parliament; Council of the European Union.

Directive 2008/98/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 November 2008 on Waste and Repealing Certain Directives (Waste Framework Directive)

. Official Journal of the European Union 2008, L312, 3–30. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:[008L0098 (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- de Oliveira, J.; Schreiber, D.; Jahno, V.D. Circular economy and buildings as material banks in mitigation of environmental impacts from construction and demolition waste. Sustainab 2024, 16, 5022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caro, D.; et al. Environmental and socio-economic effects of construction and demolition waste recovery in the European Union. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altamura, P.

Costruire a zero rifiuti

. In Strategie e strumenti per la prevenzione e l'upcycling dei materiali di scarto in edilizia; FrancoAngeli: Milano, 2016; p. 358. [Google Scholar]

- PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency. Outline of the Circular Economy. PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2019. Available online: https://www.pbl.nl/en/publications/outline-of-the-circular-economy (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Arora, M.; et al. Urban mining in buildings for a circular economy: Planning, process and management. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2021, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, J.; Schreiber, D.; Jahno, V. D. Circular Economy and Buildings as Material Banks in Mitigation of Environmental Impacts from Construction and Demolition Waste. Sustainab 2024, 16(12),

5022

. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

DOI. [CrossRef]

- McKinsey Global Institute. Reinventing construction: A route to higher productivity. McKinsey Global Institute. 2017. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/operations/our-insights/reinventing-construction-through-a-productivity-revolution (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- European Commission. A new Circular Economy Action Plan for a cleaner and more competitive Europe. Brussels: European Commission. 2020. Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/strategy/circular-economy-action-plan_en (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Zhuang, Z.; Xu, F.; Ye, J.; et al. A comprehensive review of sustainable materials and toolpath optimization in 3D concrete printing. npj Mater. Sustain. 2024, 2, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breseghello, L.; Naboni, R. Carbon-driven design of 3D concrete printed horizontal structures. In AM Perspectives: Research in Additive Manufacturing for Architecture and Construction; Rosendahl, P.L., Figueiredo, B., Turrin, M., Knaack, U., Cruz, P.J.S., Eds.; TU Darmstadt: Darmstadt, Germany, 2024; pp. 90–99. [Google Scholar]

- Vrachliotis, G. Building knowledge through printing: Rediscovering the architectural project in the age of data. In AM Perspectives: Research in Additive Manufacturing for Architecture and Construction; Rosendahl, P.L., Figueiredo, B., Turrin, M., Knaack, U., Cruz, P.J.S., Eds.; TU Darmstadt: Darmstadt, Germany, 2024; pp. 17–18. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; He, S.; Gan, Y.; Çopuroğlu, O.; Veer, F.; Schlangen, E. A review of printing strategies, sustainable cementitious materials and characterization methods in the context of extrusion-based 3D concrete printing. Cement and Concrete Composites 2023, 142, 105166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çetin, S; De Wolf, C; Bocken, N. Circular digital built environment: An emerging framework. Sustainab. 2021, 13(11), 6348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çetin, S; Raghu, D; Honic, M; Straub, A; Gruis, V. Data requirements and availabilities for material passports: A digitally enabled framework for improving the circularity of existing buildings. Sustain Prod Consum. 2023, 40, 422–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wolf C, Byers BS, Raghu D, Gordon M, Schwarzkopf V, Triantafyllidis E. D5 digital circular workflow:

Five digital steps towards matchmaking for material reuse in construction. npj Mater Sustain. 2024;2:36. [CrossRef]

- Buswell, R.A.; Leal de Silva, W.R.; Jones, S.Z.; Dirrenberger, J. 3D printing using concrete extrusion: A roadmap for research. Cem. Concr. Res. 2018, 112, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]