Submitted:

17 December 2025

Posted:

18 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

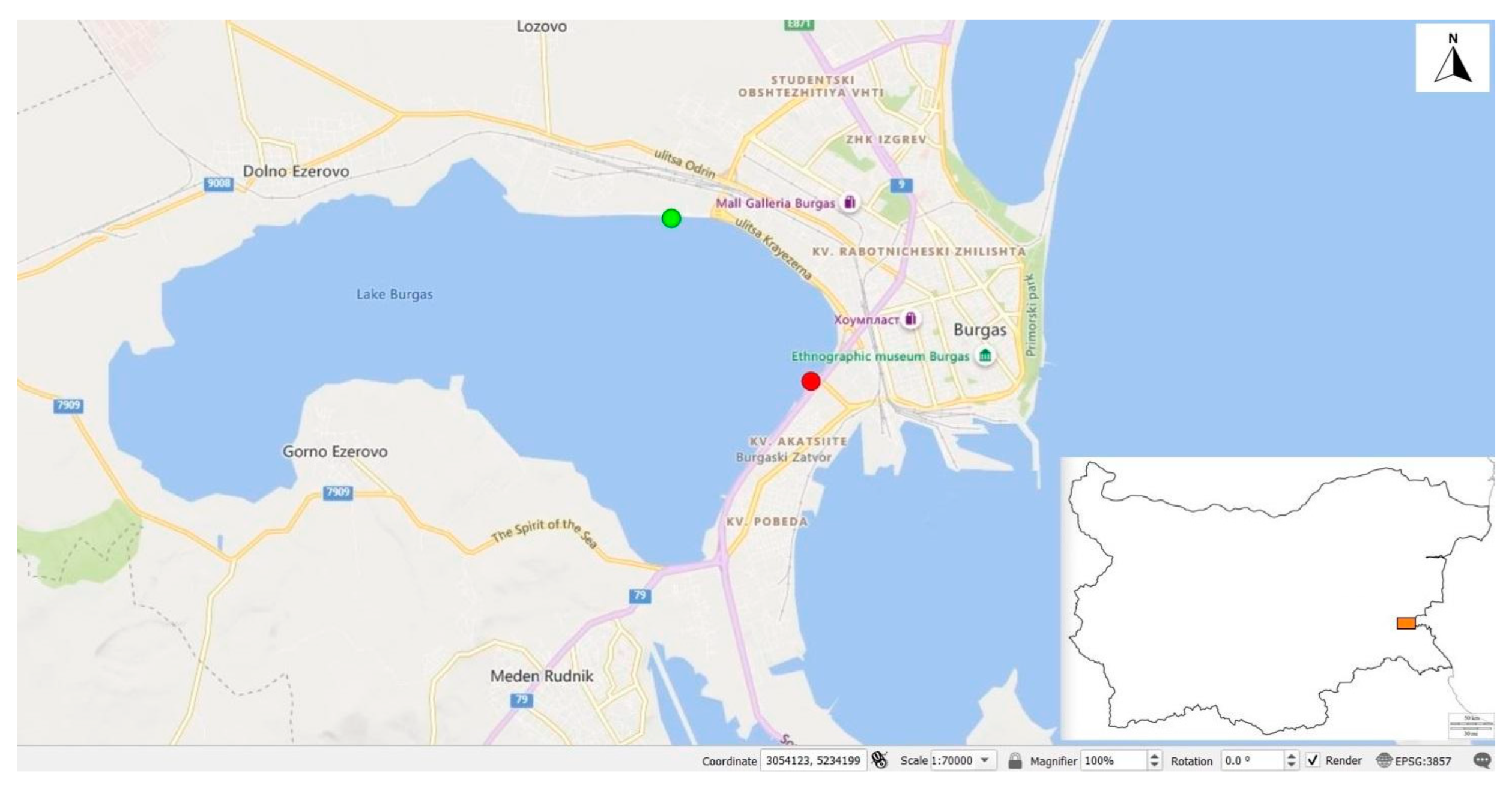

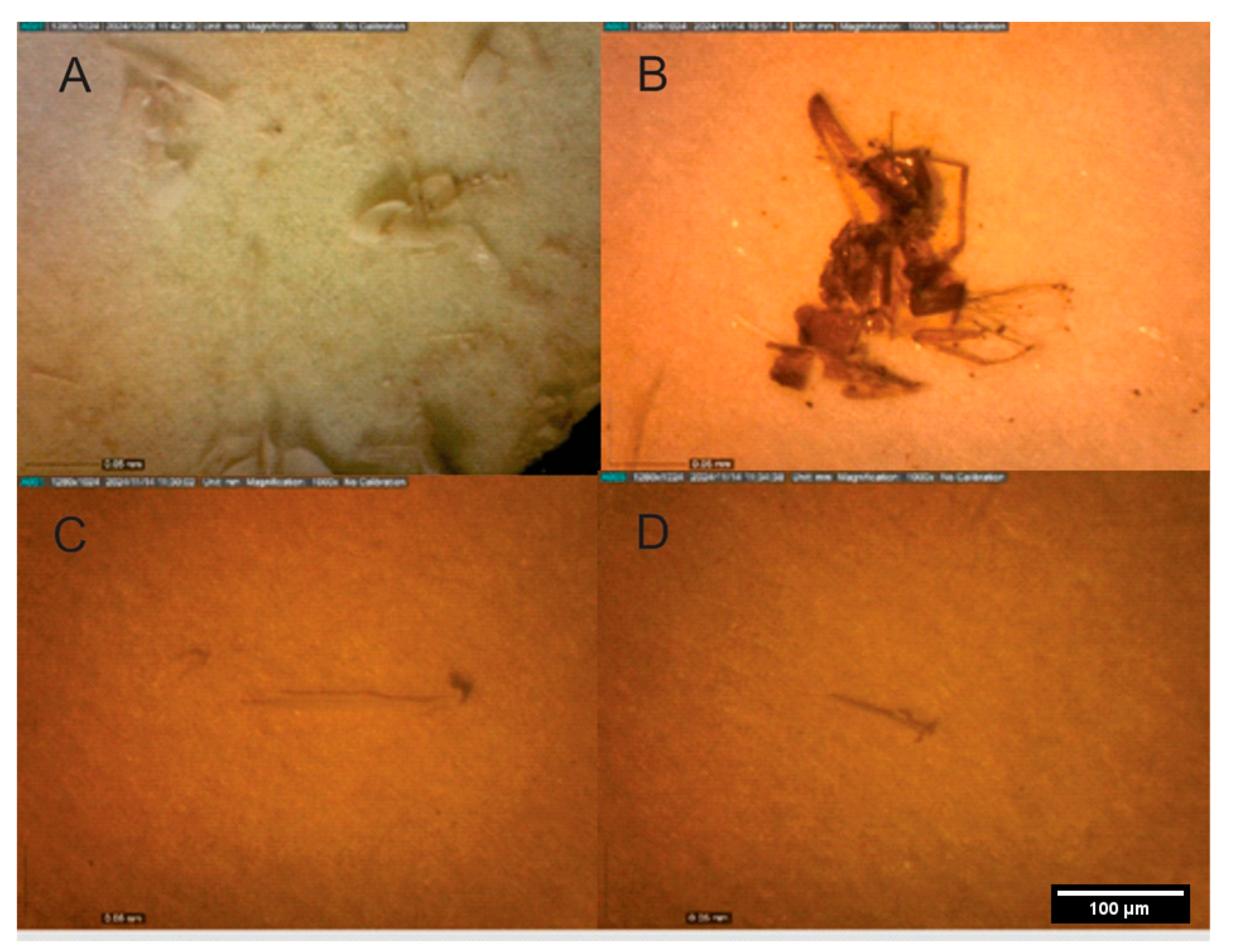

2. Materials and Methods

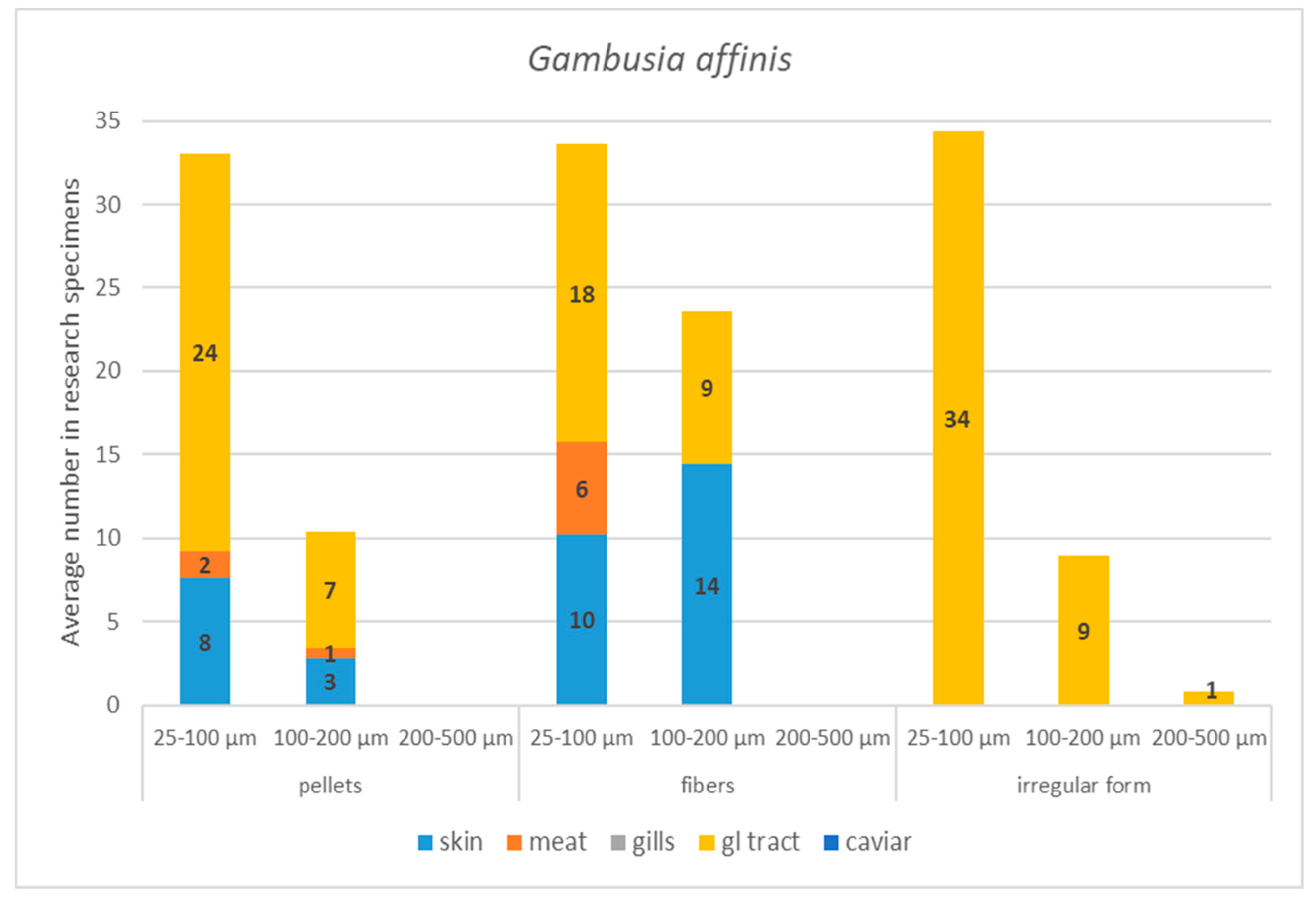

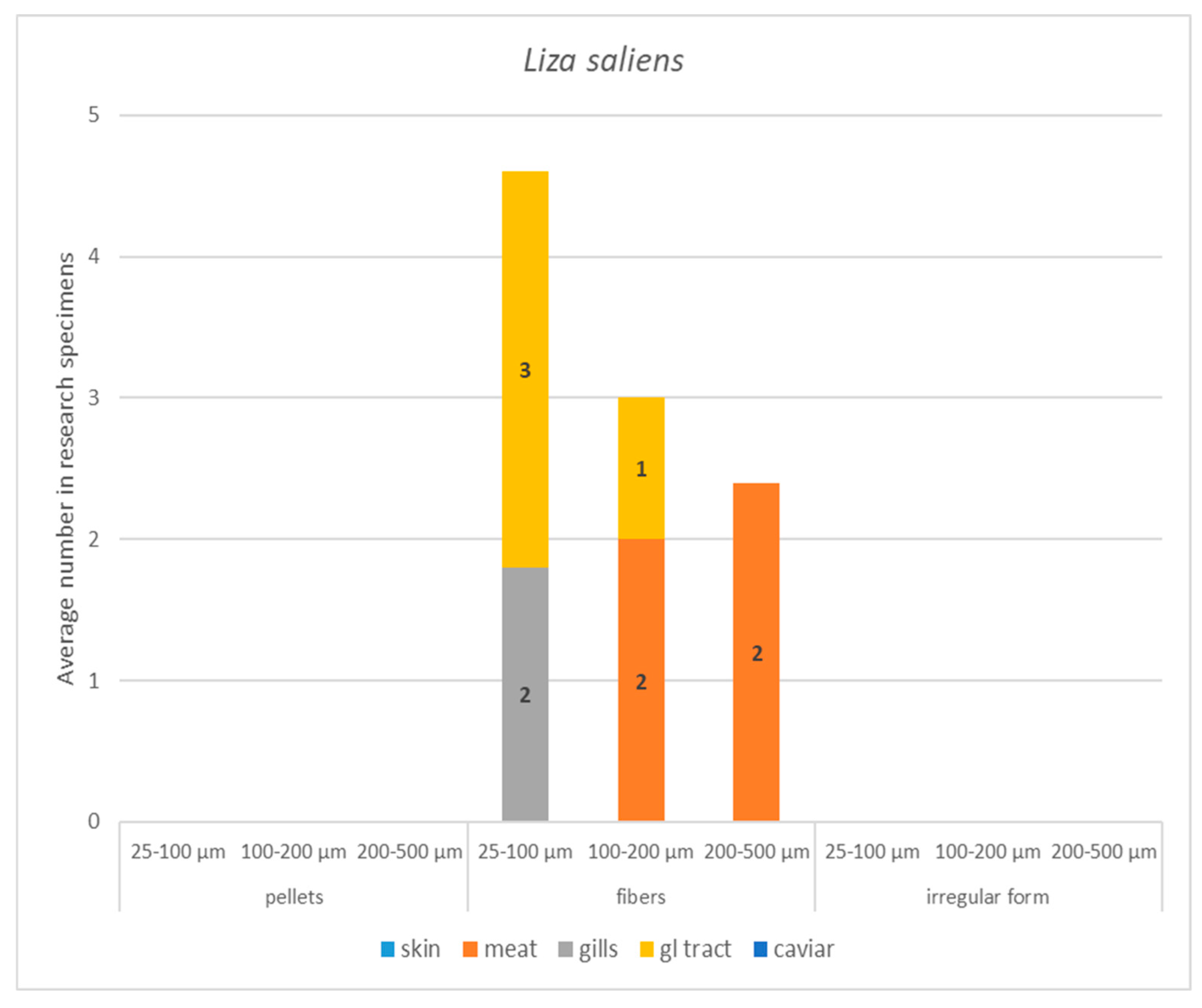

3. Results

| Mode | Value | Temp (°C) | MTC/ATC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample 1 | Sample 2 | Sample 1 | Sample 2 | ||

| mV | -39.3 mV | -37.1 mV | 13.3 | 14.0 | ATC |

| Cond | 14.28 mS/cm | 13.99 mS/cm | 15.1 | 15.8 | ATC |

| TDS | 10.1 g/l | 9.93 g/l | 15.1 | 15.8 | ATC |

| SAL | 7.97 ppt | 7.80 ppt | 15.1 | 15.8 | ATC |

| OXY | 7.5 Mg/L | 5.5 Mg/L | 15.0 | 15.8 | ATC |

| Sample 1 | Sample 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Chlorophyll A | 65 µg/L | 50 µg/L |

| TSI | 72 | 69 |

| pellets | fibers | irregular form | |||||||

| 25-100 µm | 100-200 µm | 200-500 µm | 25-100 µm | 100-200 µm | 200-500 µm | 25-100 µm | 100-200 µm | 200-500 µm | |

| Gambusia affinis | 165 | 52 | 0 | 168 | 118 | 0 | 172 | 45 | 4 |

| Liza saliens | 0 | 0 | 0 | 23 | 15 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 165 | 52 | 0 | 191 | 133 | 12 | 172 | 45 | 4 |

| Grand total | 217 | 336 | 221 | ||||||

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MP / MPs | Microplastic / Microplastics |

| PET | Polyethylene terephthalate |

| PA | Polyamide |

| LDPE | Low Density Polyethylene |

| PP | Polypropylene |

| PVP-P | Polyvinylpolypyrrolidone |

| PVC-U | Unplasticized Polyvinyl Chloride |

| EPS | Expanded Polystyrene |

| GIT | Gastrointestinal Tract |

| FTIR | Fourier Transform Infrared (Spectroscopy) |

| ATR | Attenuated Total Reflectance |

| KOH | Potassium hydroxide |

| QC | Quality control |

| QA/QC | Quality assurance / Quality control combined |

| TSI | Trophic State Index |

| Chl a | Chlorophyll a |

| ERDF | European Regional Development Fund |

| ATC | Automatic Temperature Compensation |

| MTC | Manual Temperature Compensation |

References

- Plastics the Fast Facts 2025. Global and European plastics production and economic indicators 2025, October 2025 Plastics Europe AISBL.

- Brooks, A.L., Wang, S., and Jambeck, J.R., The Chinese import ban and its impact on global plastic waste trade. Science Advances, (2018), 4 (6): eaat0131. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, H.U., Ali, Q.M., Rahman, M.A., Kamal, M., Tanjin, S., Farooq, U., Mawa, Z., Badshah, N., Mahmood, K., Hasan, R., Gabool, K., Rima, F.A., Islam, A., Rahman, O. and Hossain, Y. Growth pattern, condition and prey-predator status of 9 fish species from the Arabian Sea (Baluchistan and Sindh), Pakistan. Egyptian Journal of Aquatic Biology & Fisheries, (2020), 24: 281-292. [CrossRef]

- Lusher, A. Microplastics in the marine environment: distribution, interactions and effects. In: M. BERGMANN, L. GUTOW and M. KLAGES, eds. Marine anthropogenic litter Cham: Springer (2015), 245-307. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W., and Yu, X. Bioavailability and toxicity of microplastics to fish species: A review. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety (2020) 189: 109913. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karami, A. Gaps in aquatic toxicological studies of microplastics. Chemosphere, (2017), 184: 841-848. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.L., and Hassan, H.U. Effects of microplastics in freshwater fishes health and the implications for human health. Braz. J. Biol. (2024), 84 • . [CrossRef]

- Siddique, M.A.M., Uddin, A., Rahman, S.M.A., Rahman, M., Islam, M.S. and Kibria, G. Microplastics in an anadromous national fish, Hilsa shad Tenualosa ilisha from the Bay of Bengal, Bangladesh. Marine Pollution Bulletin, (2022), 174: 113236. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilal, M., Ali, H., Hassan, H.U., Khan ,S.U., Ghafar, R., Akram, W., Ahmad, H., Mushtaq, S., Jafari, H., Yaqoob, H., Khan, M.M., Ullah, R. and Arai, T. Cadmium (Cd) influences calcium (Ca) levels in the skeleton of a freshwater fish Channa gachua. Brazilian Journal of Biology = Revista Brasileira de Biologia, (2024), 84: e264336. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, C.B. and Quinn, B. Microplastic pollutants. Kidlington: Elsevier. The biological impacts and effects of contaminated microplastics: (2017), 159-178. [CrossRef]

- Strungaru, S.A., Jijie, R., Nicoara, M., Plavan, G. and Faggio, C. Micro-(nano) plastics in freshwater ecosystems: abundance, toxicological impact and quantification methodology. Trends in Analytical Chemistry, (2019) 110: 116-128. [CrossRef]

- Khan, W., Hassan, H.U., Gabol, K., Khan, S., Gul, Y., Ahmed, A.E., Swelum, A.A., Khooharo, A.R., Ahmad, J., Shafeeq, P., and Ullah, R.Q. Biodiversity, distributions and isolation of microplastics pollution in finfish species in the Panjkora River at Lower and Upper Dir districts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan. Brazilian Journal of Biology = Revista Brasileira de Biologia, (2024), 84: e256817. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S., Zhou, M., Chen, X., Hu, L., Xu, Y., Fu, W., Li, C. A comparative review of microplastics in lake systems from different countries and regions. Chemosphere 286 (2022), 131806. [CrossRef]

- von Moos, N., Burkhardt-Holm, P., Kohler, A. Uptake and effects of microplastics on cells and tissue of the blue mussel Mytilus edulis L. after an experimental exposure. Environ. sci. & tech. (2012), 46, 11327–11335.

- Hurley, R.R., Woodward, J.C., Rothwell, J.J. Ingestion of microplastics by freshwater tubifex worms. Environ. sci. & tech. (2017), 51: 12844–12851.

- Ghosh, S., Dey, S., Mandal, A.H., Sadhu, A., Saha, N.С., Barcel´, D., Pastorino, P., Saha, S. Exploring the ecotoxicological impacts of microplastics on freshwater fish: A critical review, Journal of Contaminant Hydrology, Journal of Contaminant Hydrology, (2025), 269: 104514. [CrossRef]

- Lund, M.A., Davis, J.A. Seasonal dynamics of plankton communities and water chemistry in a eutrophic wetland (Lake Monger: western Australia): implications for biomanipulation. Mar. Freshw. Res., (2000), 51: 321-332. [CrossRef]

- Jourdan, J., Rüdiger, R., Sarah, C. "Off to new shores: Climate niche expansion in invasive mosquitofish (Gambusia spp.)". Ecology and Evolution. (2021), 11 (24): 18369–18400. Bibcode:2021EcoEv..1118369J. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Walton et al ''Gambusia affinis (Baird & Girard) and Gambusia holbrooki Girard (mosquitofish''2012, 1st edition, A Handbook of Global Freshwater Invasive Species.

- Powell, W-J., Ford, A. K., Dehm, J. Evidence of elevated microplastic accumulation in Pacific Island mangrove sediments. Marine Pollution Bulletin. (2025), (221): 118514. [CrossRef]

- Falah, A., Peeva, G., Koleva, R., Yemendzhiev, H., Nenov, V. Monitoring and Water Quality Assessment of Burgas Lake (Vaya Lake) in the Black Sea Region of Republic of Bulgaria. Int. J. Life Sci. Res., (2019), 7:30–140.

- Georgieva, S., Stancheva, M., Makedonski, L. Persistent organochlorine compounds (PCBs, DDTs, HCB & HBDE) in wild fish from the Lake Burgas and Lake Mandra, Bulgaria. J. Int. Sci. Publ., (2015), 9: 515–523.

- Peycheva, K., Makedonski, L., Georgieva, S., Stancheva, M. Assessment of mercury content in fish tissues from selected lakes in Bulgaria and Bulgarian Black Sea. J. Int. Sci. Publ., (2015), 9: 506–514.

- Aminot, A., and Rey, F. Determination of chlorophyll a by spectroscopic methods. ICES Techniques in Marine Environmental Sciences, (2020) , DK-1261, Copenhagen K, Denmark, ISSN 0903-2606.

- Najla, S. I., Hashim, S., Hidayah, S., Talib, A., * and Abustan, M.S. Spatial and Temporal Variations of Water Quality and Trophic Status in Sembrong Reservoir, Johor. International Conference on Civil & Environmental Engineering (CENVIRON 2017), (2018), (34): 7, E3S Web of Conferences 34, 02015 (2018) . [CrossRef]

- Cunha, D.G.F., Finkler, N.R., Lamparelli, M.C. et al. Characterizing Trophic State in Tropical/Subtropical Reservoirs: Deviations among Indexes in the Lower Latitudes. Environmental Management, (2021). 68: 491–504 . [CrossRef]

- Marcogliano et al ‘’Extraction and identification of microplastics from mussels: Method development and preliminary results’’ Ital J Food Saf. 2021 Mar 11;10(1):9264. [CrossRef]

- Ibryamova, S., Toschkova, S., Bachvarova, D., Lyatif, A., Stanachkova, E., Ivanov, R., Natchev, N., Ignatova-Ivanova, Ts. Assessment of the bioaccumulation of microplastics in the black sea mussel Mytilus Galloprovincialis L., 1819. Journal of IMAB - Annual Proceeding (Scientific Papers) (2022), 28 (4): 4676-4682. [CrossRef]

- Brander, S. M., Renick, V.C., Foley, M. M., Steele, C., Woo, M., Lusher, A., Carr, S., Helm, P., Box, C., Cherniak, S., Andrews, R. C., and Rochman, C .M. Sampling and Quality Assurance and Quality Control: A Guide for Scientists Investigating the Occurrence of Microplastics Across Matrices. Applied Spectroscopy, (2020), 74 (9), 1099-1125. https://opg.optica.org/as/abstract.cfm?URI=as-74-9-1099. [CrossRef]

- Hermsen, E., Mintenig, S. M., Besseling, E., Koelmans, A. A. Quality Criteria for the Analysis of Microplastic in Biota Samples: A Critical Review. Environmental Science & Technology. (2018), 52 (18), 10230–10240. [CrossRef]

- Noonan, M.J., Grechi, N., Mills, C. et al. Microplastics analytics: why we should not underestimate the importance of blank controls. Micropl.&Nanopl. (2023). 3: 17. [CrossRef]

- Lares, M., Ncibi, M. C., Sillanpää, M., Sillanpää, M. Occurrence, identification and removal of microplastic particles and fibers in conventional activated sludge process and advanced MBR technology. Water Research, (2018), 133: 236-246. [CrossRef]

- Dimitrova , R., Nenova , E., Uzunov , B., Shishiniova, M., and Stoyneva, M. PHYTOPLANKTON COMPOSITION OF VAYA LAKE (2004–2006). Bulgarian Journal of Agricultural Science, (2014) 20 (Supplement 1): 165–172.

- Vinagre, P. Setting reference conditions for mesohaline and oligohaline macroinvertebrate communities sensu WFD: Helping to define achievable scenarios in basin management plans. Ecological Indicators. (2015). [CrossRef]

- Falah, A., Peeva, G., Koleva, R., Yemendzhiev, H., Nenov, V. Monitoring and Water Quality Assessment of Burgas Lake (Vaya Lake) in the Black Sea Region of Republic of Bulgaria. International Journal of Life Sciences Research, (2019), 7 (3): 130-140.

- Dimitrova , R., Nenova , E., Uzunov , B., Shishiniova, M., and Stoyneva, M. Phytoplankton abundance and structural parameters of the critically endangered protected area Vaya Lake (Bulgaria). Biotechnology & Biotechnological Equipment, (2014), 28, (5): 871-877. [CrossRef]

- Teneva, I., Belkinova, D., Mladenov, R., Stoyanov, P., Moten, D., Basheva, D., Kazakov, S., Dzhambazov, Balik. Phytoplankton composition with an emphasis of Cyanobacteria and their toxins as an indicator for the ecological status of Lake Vaya (Bulgaria) – part of the Via Pontica migration route. Biodiversity Data Journal. (2020), 8: e57507. 10.3897/BDJ.8.e57507.

- Kurtul, I., Eryaşar, A., Mutlu, T. et al. Microplastic ingestion in invasive mosquitofish ( Gambusia holbrooki ): a nationwide survey from Türkiye. Environ Sci Eur, (2025). [CrossRef]

- Buwono, N. R., Risjani, Y., Soegiantoa, A. Oxidative stress responses of microplastic-contaminated Gambusia affinis obtained from the Brantas River in East Java, Indonesia. Chemosphere, (2022),133543. [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, T., Gholizadeh, M., Abarghouei, S., Zakeri, M., Hedayati, A., Rabaniha, M., Aghaeimoghadam,A., Hafezieh, M. Microplastics distribution, abundance and composition in sediment, fishes and benthic organisms of the Gorgan Bay, Caspian sea. Chemosphere, (2020), 257: 127201. [CrossRef]

- Wang, F., Gao, J., Zhai, W., Liu, D., Zhou, Z., Wang, P. The influence of polyethylene microplastics on pesticide residue and degradation in the aquatic environment. Journal of Hazardous Materials, (2020), 394: 122517. [CrossRef]

- James, B. D., de Vos, A., Aluwihare, L. I., Youngs, S., Wart, C.P., Nelson, R. K., W.,. Michel, A.P., Hahn, M. E., Reddy, C. M. Divergent Forms of Pyroplastic: Lessons Learned from the M/V X-Press Pearl Ship Fire. ACS Environ. (2022), 2 (5): 467–479. [CrossRef]

- Peycheva, K., Panayotova, V., Stancheva, R., Makedonski, L., Merdzhanova, A., Parrino, V., Nava, V., Cicero, N., and Fazio, F. Risk Assessment of Essential and Toxic Elements in Freshwater Fish Species from Lakes near Black Sea, Bulgaria. Toxics (2022), 10: 675. [CrossRef]

- Munno, K., Helm, P. A., Rochman, C., George, T., Jackson, D.A. Microplastic contamination in Great Lakes fish. Conservation biology. (2022), 36 (1): e13794. [CrossRef]

- Yin, X., Wu, J., Liu, Y., Chen, X., Xie, C., Liang, Y., Li, J., Jiang, Z. Accumulation of microplastics in fish guts and gills from a large natural lake: Selective or non-selective? Environmental Pollution, (2022), (309): 15, 119785. [CrossRef]

- Capone, A., Petrillo, M., Misic, C. Ingestion and Elimination of Anthropogenic Fibres and Microplastic Fragments by the EuropeanAnchovy (Engraulis Encrasicolus) of the NW Mediterranean Sea. Mar. Biol. (2020), 167, 166. [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.J., Jia, Y.F., Chen, N.A., Bian, W.P., Li, Q.K., Ma, Y.B., Chen,Y.L, & Pei, D.S. Zebrafish as a model system to study toxicology. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, (2014), 33: 11–17. https:// doi.org/10.1002/etc.2406.

- Lei, L., Wu, S., Lu, S., Liu, M., Song, Y., Fu, Z., Shi, H., Raley-Susman, K.M., & He, D. Microplastic particles cause intestinal damage and other adverse effects in zebrafish Danio rerio and nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Science of the Total Environment, (2018), 619–620:1–8. [CrossRef]

- Mazurais, D., Ernande, B., Quazuguel, P., Severe, A., Huelvan, C., Madec, L., Mouchel, O., Soudant, P., Robbens, J., Huvet, A., & Zambonino- Infante, J. Evaluation of the impact of polyethylene microbeads ingestion in European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) larvae. Marine Environmental Research, (2015), 112: 78–85. [CrossRef]

- Qu, H., Ma, R., Wang, B., Yang, J., Duan, L., & Yu, G. Enantiospecific toxicity, distribution and bioaccumulation of chiral antidepressant venlafaxine and its metabolite in loach (Misgurnus anguillicaudatus) co-exposed to microplastic and the drugs. Journal of Hazardous Materials, (2019), 370: 203–211. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y., Bao, Z., Wan, Z., Fu, Z., & Jin, Y. Polystyrene microplastic exposure disturbs hepatic glycolipid metabolism at the physiological, biochemical, and transcriptomic levels in adult zebrafish. Science of the Total Environment, (2020), 710: 136279. [CrossRef]

- Pannetier, P., Morin ,B., Le Bihanic, F., Dubreil, L., Clérandeau, C., Chouvellon, F., Van Arkel, K., Danion, M., & Cachot, J. Environmental samples of microplastics induce significant toxic effects in fish larvae. Environment International, (2020), 134: 105047. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2019.105047.

- Ding, J., Huang, Y., Liu, S., Zhang, S., Zou, H., Wang, Z., Zhu, W., & Geng, J. Toxicological effects of nano- and micro-polystyrene plastics on red tilapia: Are larger plastic particles more harmless? Journal of Hazardous Materials, (2020), 396: 122693. [CrossRef]

- Jabeen, K., Su, L., Li, J., Yang, D., Tong, C., Mu, J., & Shi, H. Microplastics and mesoplastics in fish from coastal and fresh waters of China. Environmental Pollution, (2017), 221: 141–149. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.envpol.2016.11.055.

- Qiao, R., Deng, Y., Zhang, S., Borri, M., Zhu, Q., Ren, H., & Zhang, Y. Accumulation of different shapes of microplastics initiates intestinal injury and gut microbiota dysbiosis in the gut of zebra fish. Chemosphere, (2019), 236: 124334. [CrossRef]

- Xia, X., Sun, M., Zhou, M., Chang, Z., & Li, L. Polyvinyl chloride microplastics induce growth inhibition and oxidative stress in Cyprinus carpio var. larvae. Science of the Total Environment, (2020), 716: 136479. [CrossRef]

- Menezes, M., Mello, F.T., Ziegler, L., Wanderley, B., Gutiérrez, J.M., Dias, J.D. Revealing the hidden threats: Genotoxic effects of microplastics on freshwater fish. Aquatic Toxicology, (2024), 276: 107089. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).