1. Introduction

The dynamics of galaxies and the large-scale structure of the Universe present one of the most persistent challenges in modern theoretical physics. Within the standard cosmological paradigm, the observed discrepancies between luminous matter and gravitational dynamics are attributed to a dominant non-baryonic dark matter component [

1]. While this framework has been remarkably successful at cosmological scales, its application at galactic scales relies on dark matter halo profiles that are not uniquely predicted from first principles, leading to long-standing phenomenological tensions [

1].

An alternative approach is to modify the laws of gravity or inertia in regimes of low acceleration. Modified Newtonian Dynamics (MOND), originally proposed by Milgrom, introduces a characteristic acceleration scale below which Newtonian gravity is altered [

2,

3]. Remarkably, MOND naturally explains several empirical regularities of galaxy rotation curves, including the baryonic Tully–Fisher relation and the tight correlation between baryonic mass distributions and observed accelerations [

4,

5,

6,

7]. These successes suggest that galactic dynamics may encode fundamental information about gravity beyond the Newtonian limit.

More recently, emergent gravity has been proposed as a framework in which gravity is not a fundamental interaction but arises from underlying microscopic degrees of freedom associated with spacetime and information [

8]. In this approach, additional gravitational effects emerge from entropic or holographic considerations, potentially reproducing MOND-like phenomenology without introducing dark matter. In particular, Verlinde’s formulation predicts modifications to gravitational dynamics at galactic scales that can mimic observed rotation curves under certain assumptions [

8].

Despite their conceptual differences, MOND and emergent gravity share a common goal: explaining galactic phenomenology without invoking particle dark matter. However, their theoretical foundations, assumptions, and regimes of validity differ substantially. A careful phenomenological comparison is therefore necessary to assess how these frameworks relate to each other and how well they reproduce observed galactic regularities.

In this work, we present a comparative phenomenological analysis of MOND and emergent gravity at galactic scales. We review the basic phenomenological predictions of MOND, outline the assumptions underlying emergent gravity models, and examine how each framework accounts for key observational relations such as galaxy rotation curves and acceleration relations. Rather than focusing on cosmological extensions or microscopic derivations, we emphasize observable consequences at galactic scales, where both approaches are most directly tested.

2. MOND Phenomenology at Galactic Scales

2.1. Galaxy Rotation Curves

One of the primary empirical motivations for Modified Newtonian Dynamics arises from the observed behavior of galaxy rotation curves. In spiral galaxies, the measured rotational velocity

is found to remain approximately constant at large galactocentric radii, despite the fact that the enclosed baryonic mass profile predicts a Keplerian decline within Newtonian dynamics [

9]. Within the standard dark matter paradigm, this discrepancy is attributed to the presence of extended dark matter halos whose density profiles dominate the outer regions of galaxies.

Within the MOND framework, flat rotation curves emerge naturally in the low-acceleration regime without invoking dark matter. For a test particle in circular orbit around a baryonic mass

M, the Newtonian gravitational acceleration is

In the deep-MOND limit, where

, the modified acceleration relation reduces to

a result that is independent of the specific form of the interpolation function in this regime

1.

Identifying the centripetal acceleration as

, one obtains

which immediately yields an asymptotically constant rotational velocity,

This result provides a natural explanation for the observed flatness of galaxy rotation curves at large radii, directly linking the rotational dynamics to the underlying baryonic mass distribution.

Beyond reproducing the overall flatness of rotation curves, MOND successfully accounts for detailed features of individual galaxy rotation profiles when the observed baryonic mass distribution is used as input. In many systems, small-scale features in the baryonic surface density are reflected directly in the inferred acceleration profile, indicating a close correspondence between baryonic and dynamical structures

2.

2.2. Baryonic Tully–Fisher Relation

The asymptotic velocity relation derived in the deep-MOND regime leads directly to the baryonic Tully–Fisher relation (BTFR). Squaring the asymptotic velocity expression obtained above yields

which predicts a power-law relation between the total baryonic mass of a galaxy and the fourth power of its asymptotic rotational velocity.

Observationally, the BTFR is found to be remarkably tight across several orders of magnitude in galaxy mass and surface brightness. The intrinsic scatter of the relation is extremely small, suggesting a fundamental link between baryonic mass and galactic dynamics

3. This behavior stands in sharp contrast to expectations from

CDM simulations, where reproducing the observed BTFR typically requires fine-tuned baryonic feedback processes

4.

Within the MOND framework, the BTFR is not an empirical coincidence but a direct consequence of the modified acceleration law and the existence of the universal acceleration scale . The emergence of a single acceleration scale governing galactic dynamics provides a compelling explanation for the observed regularities, though it also highlights the phenomenological nature of the framework.

Despite its success at galactic scales, the explanatory power of MOND relies on the phenomenological input of the acceleration scale

and the assumption of a universal interpolation function. While these assumptions yield excellent agreement with galactic rotation curves and scaling relations, their extension to larger systems such as galaxy clusters and cosmology remains nontrivial and has motivated the development of relativistic extensions and alternative theoretical frameworks

5.

2.3. Radial Acceleration Relation

A more recent and particularly striking empirical regularity associated with galactic dynamics is the so-called radial acceleration relation (RAR), which establishes a tight correlation between the observed centripetal acceleration in disk galaxies and that predicted from the observed baryonic mass distribution alone. The relation was systematically identified using high-quality rotation curve data and has since emerged as one of the most robust phenomenological signatures of galactic dynamics

6.

The RAR is commonly expressed as a relation between the observed acceleration,

and the Newtonian acceleration computed from the baryonic mass distribution,

Observationally, these two quantities are found to be tightly correlated over several orders of magnitude in acceleration, with remarkably small intrinsic scatter. At high accelerations, corresponding to inner galactic regions, the relation approaches the Newtonian limit , while at low accelerations a systematic deviation from Newtonian expectations is observed.

Within the MOND framework, the radial acceleration relation arises naturally as a direct consequence of the modified acceleration law. Using the interpolation relation

one obtains an explicit functional relation between

and

. In the deep-MOND regime, where

, the modified dynamics predict

which reproduces the low-acceleration branch of the observed RAR. Importantly, this relation is not an additional empirical input but follows directly from the same acceleration scale

that governs rotation curves and the baryonic Tully–Fisher relation.

The observed tightness of the RAR presents a significant challenge for the standard

CDM paradigm. In that framework, the relation between baryonic and total acceleration depends on the complex interplay between baryonic physics and dark matter halo properties, and is not predicted a priori. Reproducing the observed RAR typically requires finely tuned feedback processes that correlate baryonic distributions with dark matter halos across a wide range of galaxy masses

7.

From a phenomenological perspective, the RAR strengthens the case for a universal underlying principle governing galactic dynamics. Whether this principle reflects a modification of gravity, a modification of inertia, or an emergent gravitational phenomenon remains an open question. Nevertheless, the existence of a single, tight relation linking baryonic mass distributions to observed accelerations across diverse galaxy populations constitutes one of the most compelling empirical regularities in galactic astrophysics.

In the context of this work, the radial acceleration relation serves as a crucial benchmark for comparing MOND and emergent gravity models. Any viable alternative to dark matter must account not only for individual rotation curves and scaling relations but also for the observed universality and low scatter of the RAR.

2.4. Phenomenological Limitations of MOND

Despite its remarkable phenomenological success at galactic scales, Modified Newtonian Dynamics faces several well-known challenges when confronted with a broader range of astrophysical and cosmological observations. These limitations do not invalidate the phenomenological achievements discussed above, but they highlight the restricted domain of applicability of the non-relativistic MOND framework and motivate the development of more complete theoretical extensions.

One of the most persistent challenges for MOND arises in galaxy clusters. Observations of cluster dynamics, including galaxy velocity dispersions and X-ray emitting intracluster gas, indicate a residual mass discrepancy even when MONDian dynamics are applied. While MOND reduces the inferred mass discrepancy relative to Newtonian gravity without dark matter, it does not fully eliminate it in clusters, suggesting the need for additional unseen mass or further modifications of the framework

8. Proposed resolutions include the presence of additional baryonic components or massive neutrinos, though these additions partially undermine the original motivation of avoiding unseen matter altogether.

A second important limitation is the so-called external field effect (EFE), a distinctive feature of MOND that arises from its inherent nonlinearity. In MOND, the internal dynamics of a gravitationally bound system can depend on the external gravitational field in which it is embedded, even if that field is uniform. This violates the strong equivalence principle and leads to observable consequences in systems such as dwarf galaxies orbiting larger hosts

9. While the EFE provides a potential observational discriminator between MOND and dark matter models, it also complicates the theoretical interpretation of galactic dynamics and introduces sensitivity to environmental effects.

Perhaps the most significant limitation of MOND concerns its extension to cosmology. The original MOND formulation is non-relativistic and therefore insufficient for describing cosmological expansion, structure formation, and gravitational lensing in a consistent manner. Relativistic extensions, such as Tensor–Vector–Scalar (TeVeS) theory, have been proposed to embed MOND-like phenomenology within a covariant framework

10. While such theories can reproduce some cosmological observations, including aspects of large-scale structure and lensing, they often require additional fields or fine-tuning and do not yet match the overall simplicity and empirical success of the standard

CDM model at cosmological scales.

Taken together, these phenomenological limitations indicate that MOND, in its simplest form, should be regarded primarily as an effective description of galactic-scale dynamics rather than a complete theory of gravity. Nevertheless, the consistency and predictive power of its galactic phenomenology suggest that it captures an essential aspect of gravitational dynamics in the low-acceleration regime. This has motivated the exploration of alternative theoretical frameworks, including emergent gravity models, which aim to reproduce MOND-like behavior while offering a deeper microscopic or cosmological foundation.

In the following sections, we examine whether emergent gravity provides a viable alternative explanation for the phenomenological successes of MOND, and whether it can address some of the limitations encountered by MOND when extended beyond galactic scales.

3. Emergent Gravity at Galactic Scales

Emergent gravity has been proposed as an alternative framework in which gravity is not a fundamental interaction but arises as an effective, macroscopic phenomenon associated with microscopic degrees of freedom of spacetime and information. In this approach, additional gravitational effects emerge at large distances, potentially accounting for observed galactic dynamics without invoking particle dark matter. In this section, we restrict attention exclusively to the phenomenological implications of emergent gravity at galactic scales, where observational tests are most direct.

3.1. Phenomenological Prescription

In Verlinde’s formulation of emergent gravity, deviations from Newtonian gravity arise due to an additional, emergent contribution to the gravitational acceleration associated with the baryonic mass distribution [

8]. Under a set of simplifying assumptions—such as spherical symmetry, isolation, and equilibrium—the total radial acceleration

experienced by a test particle can be written as

where

is the standard Newtonian acceleration sourced by baryonic matter, and

denotes the emergent gravity contribution.

For a spherically symmetric baryonic mass distribution

, the emergent component is often expressed phenomenologically as

where

is an acceleration scale of order

numerically comparable to the MOND acceleration scale. This relation leads to an effective enhancement of the gravitational acceleration in the low-acceleration regime, yielding flat galaxy rotation curves at large radii without introducing dark matter.

Importantly, this phenomenological scaling is not derived here from microscopic considerations but is taken as an effective prediction of the emergent gravity framework under idealized conditions. Its domain of validity is therefore limited to systems where the underlying assumptions—such as approximate spherical symmetry and negligible environmental effects—are expected to hold.

3.2. Predictions for Galaxy Rotation Curves

Applying the above acceleration law to circular motion, where

, one finds that at large radii the rotational velocity asymptotically satisfies

recovering a baryonic Tully–Fisher–like scaling similar to that obtained in MOND. As a result, emergent gravity naturally predicts approximately flat rotation curves and a tight correlation between baryonic mass and asymptotic rotational velocity.

At the phenomenological level, emergent gravity therefore reproduces several of the same galactic-scale regularities that motivate MOND, including the close coupling between baryonic mass distributions and observed kinematics. However, unlike MOND, the emergent gravity prescription is not formulated as a modification of inertia or a fundamental acceleration law but instead arises as an effective description linked to macroscopic properties of spacetime.

3.3. Scope and Limitations

While emergent gravity captures key features of galactic rotation curves under idealized conditions, its applicability beyond simple, isolated systems remains an open question. Extensions to non-spherical systems, environments with strong external fields, and galaxy clusters are not yet fully established at the phenomenological level. Moreover, the framework has not been developed into a complete relativistic theory capable of addressing cosmological perturbations, structure formation, and gravitational lensing in a fully consistent manner.

For these reasons, emergent gravity should presently be regarded as an effective phenomenological framework for galactic dynamics rather than a complete alternative to the standard cosmological model. In the following section, we compare its galactic-scale predictions directly with those of MOND, highlighting both similarities and key differences in their phenomenological behavior.

4. Comparative Phenomenological Analysis

4.1. Conceptual Comparison of MOND and Emergent Gravity

Although MOND and emergent gravity can reproduce similar galactic phenomenology without invoking particle dark matter, they differ substantially in their theoretical interpretation, predictive rigidity, and domain of validity. A direct comparison therefore requires distinguishing not only their empirical successes but also the assumptions underlying those successes.

MOND was introduced as a phenomenological modification of Newtonian dynamics in the low-acceleration regime. Its defining feature is the existence of a universal acceleration scale , below which the relation between baryonic mass and gravitational acceleration is altered. Once and an interpolation function are specified, MOND yields tightly constrained predictions for galaxy rotation curves and scaling relations, leaving little freedom to adjust individual systems. As a result, its empirical successes at galactic scales are highly nontrivial.

Emergent gravity, by contrast, does not modify the laws of motion but interprets gravity as an effective, macroscopic phenomenon arising from microscopic degrees of freedom associated with spacetime and information. In Verlinde’s formulation, additional gravitational effects emerge at large distances due to entropic or holographic considerations, leading to MOND-like scaling relations. The associated acceleration scale is naturally of order , suggesting a connection between galactic dynamics and cosmology. At present, however, these results are obtained at an effective phenomenological level and rely on restrictive assumptions such as spherical symmetry, isolation, and equilibrium. Consequently, emergent gravity does not yet provide a unique or generally applicable mapping from baryonic mass distributions to observed galactic dynamics.

Both frameworks predict a strong correlation between baryonic matter and observed gravitational effects, but the origin of this correlation differs. In MOND, it follows directly from the modified acceleration law, whereas in emergent gravity it arises as an effective response of spacetime to baryonic matter. This difference is reflected in their predictive structure: MOND is highly constrained and extensively tested across diverse galactic environments, while emergent gravity remains more sensitive to idealized conditions.

Environmental effects further distinguish the two approaches. MOND generically predicts the external field effect, whereby the internal dynamics of a system depend on the external gravitational field, violating the strong equivalence principle and leading to observable consequences. In emergent gravity, the existence of a comparable effect remains unclear. The presence or absence of such environmental dependence therefore provides a potential empirical discriminator between the two frameworks.

In summary, while both MOND and emergent gravity reproduce key galactic-scale regularities, they do so from fundamentally different conceptual standpoints. Their apparent phenomenological agreement masks important differences in theoretical status and robustness, motivating a direct comparison of their predictions for specific observables.

4.2. Radial Acceleration Relation

One of the most striking empirical regularities in galactic dynamics is the radial acceleration relation (RAR), which links the observed centripetal acceleration inferred from galaxy rotation curves to the acceleration predicted by the observed baryonic mass distribution alone. Observationally, disk galaxies populate a narrow, nearly universal relation across several orders of magnitude in acceleration, with extremely small intrinsic scatter.

The RAR is commonly expressed as a relation between the observed acceleration

and the Newtonian acceleration sourced by baryonic matter,

where

denotes the enclosed baryonic mass. The observed relation exhibits a smooth transition from the Newtonian regime at high accelerations to a modified regime below an acceleration scale of order

.

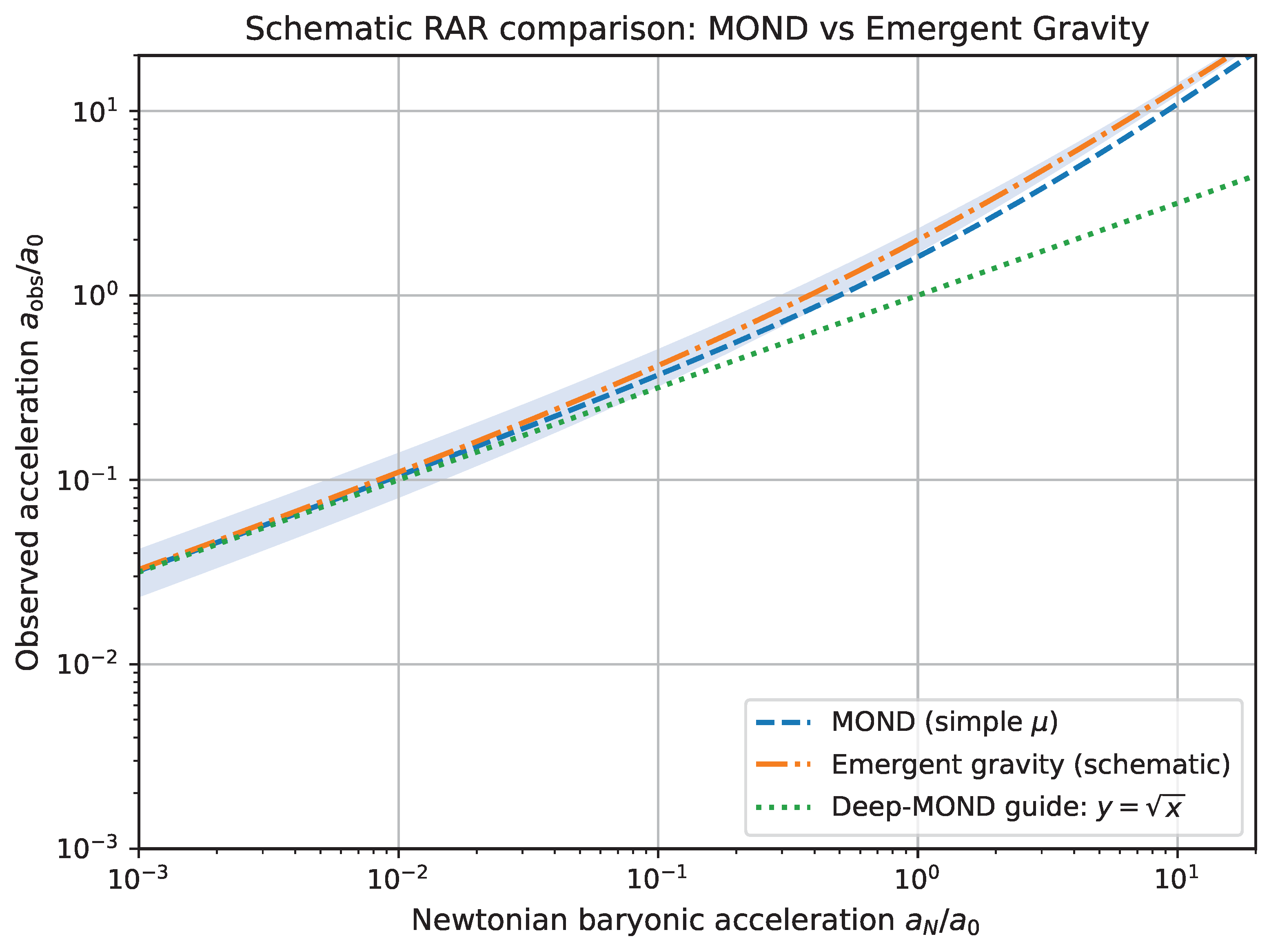

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the radial acceleration relation (RAR) at galactic scales. The observed centripetal acceleration is plotted against the Newtonian baryonic acceleration , both normalized by the characteristic acceleration scale . MOND predicts a smooth transition between the Newtonian and deep-MOND regimes, while emergent gravity reproduces a similar scaling at the phenomenological level under idealized assumptions. The curves shown are schematic and intended solely as a qualitative comparison, not as quantitative predictions or fits to observational data.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the radial acceleration relation (RAR) at galactic scales. The observed centripetal acceleration is plotted against the Newtonian baryonic acceleration , both normalized by the characteristic acceleration scale . MOND predicts a smooth transition between the Newtonian and deep-MOND regimes, while emergent gravity reproduces a similar scaling at the phenomenological level under idealized assumptions. The curves shown are schematic and intended solely as a qualitative comparison, not as quantitative predictions or fits to observational data.

Within the MOND framework, the RAR arises directly from the modified acceleration law

where

is an interpolation function satisfying the appropriate Newtonian and deep-MOND limits. In the low-acceleration regime

, this relation reduces to

yielding a one-to-one correspondence between baryonic mass and observed dynamics. Importantly, this prediction does not rely on assumptions of symmetry, isolation, or equilibrium. Once the acceleration scale

is fixed, the form and tightness of the RAR follow with minimal freedom, naturally accounting for both its shape and low intrinsic scatter.

In emergent gravity, the RAR is reproduced at the phenomenological level through an additional effective contribution to the gravitational acceleration arising from entropic or holographic considerations. Under simplifying assumptions such as spherical symmetry and isolation, the total acceleration may be written as

with the emergent component often expressed as

where the acceleration scale

is naturally of order

. This leads to a MOND-like scaling in the low-acceleration regime and reproduces the observed form of the RAR without invoking particle dark matter.

The key distinction lies in the origin and robustness of the relation. In MOND, the RAR is a direct and unavoidable consequence of the fundamental dynamical law, whereas in emergent gravity it arises as an effective scaling under restrictive and idealized conditions. Departures from spherical symmetry, equilibrium, or isolation are therefore expected to introduce deviations or additional scatter in emergent gravity models, placing strong constraints on their domain of applicability.

At the level of galactic phenomenology, both frameworks reproduce the gross form of the RAR. However, the observed universality and exceptionally low intrinsic scatter of the relation favor frameworks in which the RAR is encoded fundamentally rather than emerging conditionally. This contrast highlights a key phenomenological difference between MOND and emergent gravity that is directly testable using galactic data.

4.3. Environmental Dependence and Intrinsic Scatter

A key observational feature of galactic scaling relations, including the radial acceleration relation, is their exceptionally low intrinsic scatter across a wide range of galaxy masses, morphologies, and environments. Any viable alternative to dark matter must therefore account not only for the mean form of these relations but also for their remarkable uniformity.

In the MOND framework, environmental effects arise explicitly through the external field effect (EFE), whereby the internal dynamics of a gravitationally bound system depend on the external gravitational field in which it is embedded. This behavior follows directly from the nonlinearity of the MOND acceleration law and represents a violation of the strong equivalence principle. Importantly, the EFE leads to specific and testable deviations from isolated-system predictions, particularly in low-mass systems such as dwarf galaxies orbiting more massive hosts. While the EFE introduces environment-dependent modifications, it does so in a controlled and predictable manner, preserving the overall tightness of galactic scaling relations.

Emergent gravity, by contrast, does not currently incorporate an explicit analogue of the external field effect. Its phenomenological predictions are typically derived under assumptions of isolation, spherical symmetry, and equilibrium. Environmental influences therefore enter only implicitly, through departures from these idealized conditions. As a result, the impact of external gravitational fields on galactic dynamics is not formulated as a universal law within the framework, and its observational consequences remain less well defined.

This distinction has important implications for intrinsic scatter. In MOND, the low scatter of relations such as the RAR is a natural consequence of the underlying dynamical law, with environmental effects introducing only limited and systematic deviations. In emergent gravity, however, the universality and small scatter of observed relations place strong constraints on the validity of the simplifying assumptions across diverse galactic environments. Significant departures from isolation or symmetry would be expected to generate additional scatter, unless suppressed by yet-unknown mechanisms.

From a phenomenological perspective, the observed robustness of galactic scaling relations therefore favors frameworks in which environmental dependence is encoded explicitly and predictively, rather than emerging indirectly through restrictive assumptions. The treatment of environmental effects and intrinsic scatter thus provides a further point of contrast between MOND and emergent gravity at galactic scales, complementing the comparison based on the form of the radial acceleration relation.

5. Discussion

The comparative analysis presented above highlights that the empirical success of galactic scaling relations does not, by itself, uniquely identify the underlying physical mechanism responsible for them. Both MOND and emergent gravity reproduce key features of galactic dynamics without invoking particle dark matter, yet they do so through fundamentally different theoretical structures. Understanding this distinction is essential for assessing the physical significance of their phenomenological agreement.

In MOND, the tight coupling between baryonic matter and observed gravitational dynamics is encoded directly in the fundamental acceleration law. As a consequence, relations such as the baryonic Tully–Fisher relation and the radial acceleration relation emerge as unavoidable predictions once the characteristic acceleration scale is fixed. The observed universality and low intrinsic scatter of these relations therefore follow naturally within the framework, with environmental effects introducing only controlled and systematic deviations.

Emergent gravity offers a conceptually distinct perspective in which MOND-like phenomenology arises as an effective manifestation of spacetime microphysics and information-theoretic considerations. While this approach provides an appealing connection between galactic dynamics and cosmology, its current phenomenological formulation relies on restrictive assumptions such as symmetry, isolation, and equilibrium. The reproduction of galactic scaling relations in this context is therefore conditional, and the observed robustness of these relations across diverse environments places strong constraints on the domain of validity of emergent gravity models.

The comparison underscores a broader point regarding alternative approaches to the dark matter problem. Empirical regularities with exceptionally small scatter, such as the radial acceleration relation, act as stringent filters on theoretical frameworks. Models in which such relations are fundamental tend to be more predictive and robust, whereas models in which they emerge only under idealized conditions must explain why deviations are not observed more frequently in real galaxies.

These considerations do not imply that emergent gravity is ruled out at galactic scales. Rather, they clarify the challenges it faces in matching the predictive rigidity of MOND while retaining its conceptual motivation. Progress in this direction would likely require a more complete and systematic treatment of environmental effects, departures from symmetry, and the transition between isolated and non-isolated systems.

Overall, the phenomenological comparison presented here suggests that, at present, MOND provides a more tightly constrained and empirically robust description of galactic dynamics, while emergent gravity remains an intriguing but less predictive framework. The tension between these approaches reflects a deeper open question: whether the observed regularities of galaxies point toward a modification of gravitational dynamics or toward an emergent, thermodynamic origin of gravity itself.

6. Conclusions

In this work, we have presented a phenomenological comparison of Modified Newtonian Dynamics and emergent gravity at galactic scales, focusing on empirical regularities that directly probe the coupling between baryonic matter and gravitational dynamics. Rather than addressing cosmological extensions or microscopic foundations, we have emphasized observables such as galaxy rotation curves, the baryonic Tully–Fisher relation, and the radial acceleration relation, which provide the most stringent tests of gravity in the low-acceleration regime.

We find that both MOND and emergent gravity can reproduce the gross features of galactic dynamics without invoking particle dark matter. However, the origin and robustness of these phenomenological successes differ significantly. In MOND, the observed scaling relations arise as direct and unavoidable consequences of a modified acceleration law, leading to highly predictive behavior and exceptionally low intrinsic scatter. In emergent gravity, similar relations emerge at an effective level under restrictive assumptions, making their validity more sensitive to symmetry, isolation, and environmental conditions.

The comparison highlights the importance of empirical universality and small intrinsic scatter as discriminating criteria for alternative theories of gravity. Frameworks in which galactic regularities are encoded fundamentally tend to be more tightly constrained and robust, whereas those in which such regularities emerge only under idealized conditions face stronger phenomenological challenges.

These results do not preclude the relevance of emergent gravity as a conceptual approach to the dark matter problem. Rather, they clarify the conditions under which it must operate in order to match the predictive success of MOND at galactic scales. Future progress will likely require a more systematic treatment of environmental effects and departures from idealized assumptions, as well as a clearer connection between galactic phenomenology and relativistic or cosmological extensions.

Overall, the phenomenological evidence considered here suggests that MOND currently provides a more constrained and empirically robust description of galactic dynamics, while emergent gravity remains an intriguing but less predictive framework. Whether the observed regularities of galaxies ultimately point toward a modification of gravitational dynamics or toward an emergent origin of gravity remains an open and fundamental question.

References

- McGaugh, S.S. A tale of two paradigms: the mutual incommensurability of ΛCDM and MOND. Canadian Journal of Physics 2015, 93, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milgrom, M. A modification of the Newtonian dynamics as a possible alternative to the hidden mass hypothesis. Astrophysical Journal 1983, 270, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milgrom, M. A modification of the Newtonian dynamics: Implications for galaxies. Astrophysical Journal 1983, 270, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGaugh, S.S.; Schombert, J.M. The baryonic Tully–Fisher relation. Astrophysical Journal 2000, 533, L99–L102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGaugh, S.S. The baryonic Tully–Fisher relation of gas-rich galaxies as a test of ΛCDM and MOND. Astronomical Journal 2012, 143, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGaugh, S.S.; Lelli, F.; Schombert, J.M. The radial acceleration relation in rotationally supported galaxies. Physical Review Letters 2016, 117, 201101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Famaey, B.; McGaugh, S.S. Modified newtonian dynamics (mond): Observational phenomenology and relativistic extensions. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verlinde, E. Emergent gravity and the dark universe. Science Advances 2016, 2, e1600343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, V.C.; Ford, W.K.J.; Thonnard, N. Extended rotation curves of high-luminosity spiral galaxies. IV. Systematic dynamical properties. Astrophysical Journal Letters 1978, 225, L107–L111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 |

In the deep-MOND limit , all commonly used interpolation functions satisfy ; see Famaey & McGaugh (2012) for a review. |

| 2 |

This empirical coupling between baryonic matter and inferred dynamics is often referred to as the mass–discrepancy–acceleration relation. |

| 3 |

See McGaugh et al. (2000, 2012) for observational studies establishing the baryonic Tully–Fisher relation over a wide range of galaxy types. |

| 4 |

For a discussion of the challenges faced by CDM in reproducing the BTFR without tuning, see Famaey & McGaugh (2012). |

| 5 |

Examples include TeVeS and related relativistic MOND theories; see Bekenstein (2004) for the original proposal. |

| 6 |

See McGaugh, Lelli & Schombert (2016) for the original identification of the radial acceleration relation using the SPARC galaxy sample. |

| 7 |

For discussions of the challenges faced by CDM in reproducing the RAR without tuning, see McGaugh et al. (2016) and Desmond (2017). |

| 8 |

For early discussions of MOND in galaxy clusters, see Sanders (1999); more recent analyses can be found in Angus, Famaey & Buote (2008). |

| 9 |

The external field effect was discussed in Milgrom (1983) and has since been explored observationally; see, for example, Famaey & McGaugh (2012). |

| 10 |

The original relativistic MOND theory was proposed by Bekenstein (2004); see also Skordis (2009) for cosmological applications. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).