1. Introduction

Tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV), currently known as

Orthoflavivirus encephalitidis of the

Orthoflavivirus genus of the

Flaviviridae family [

1], is the causative agent of tick-borne encephalitis (TBE), a severe disease of the human central nervous system. TBEV has a single-stranded positive-sense RNA genome of approximately 10.5-11 kb in length. This includes a 5’ type I cap, 5’- and 3’-noncoding regions and one open reading frame (ORF), which encodes three structural and seven non-structural proteins [

2]. TBE foci have been identified in many European and Asian countries, where up to 12,000 cases of the disease are detected annually. The mortality rate ranges from 0.2% to 20%, depending on the region and possibly the virus subtype [

2].

In accordance with the generally accepted classification, TBEV is currently divided into three subtypes: Far Eastern (TBEV-FE), Siberian (TBEV-Sib) and European (TBEV-Eu) [

3]; in addition, two putative TBEV subtypes have been described: Baikalian [

4] and Himalayan [

5]. TBEV-Sib is the most common subtype and, with the exception of Central and Western Europe, is found in all regions where TBEV has been detected. Five genetic lineages have currently been described for TBEV-Sib: Zausaev, Vasilchenko, Baltic, Obskaya, and Bosnia [

3,

6], with each lineage having specific patterns of geographical distribution. Genetic lineages have also been described for the Far Eastern and European subtypes [

2].

Kyrgyzstan (or officially, the Kyrgyz Republic) is located in Central Asia, bordering the TBE-endemic regions of Kazakhstan and China, and is therefore at risk of the spread of TBE within its territory. The alternation of mountain ranges and intermontane depressions determines the exceptional diversity of the landscapes and, as a result, the diversity of arthropods, including TBEV vectors.

Data on the epidemiology and clinical picture of TBE in Kyrgyzstan are very fragmentary. Isolated studies show that both TBEV and TBE cases are detected in this territory. Thus, previously in Kyrgyzstan, TBEV has been found in ticks [

7], and the presence of TBEV seropositivity was shown in humans and birds [

8,

9]. However, since the late 1990s, there has been no data on the spread of TBEV in Kyrgyzstan. In the early 2000s, field studies were conducted to assess the risk level of zoonotic diseases, including TBE. As a result of the study, the distribution of tick-borne encephalitis was identified, namely in two areas of the Ala-Archa National Nature Park. A repeat experiment was conducted to collect animals and ticks in these areas, which resulted in the discovery of ticks infected with TBEV whose genome corresponded to the Siberian subtype, as well as the presence of IgG and IgM to TBEV in small mammals [

10].

Cases of TBE in Kyrgyzstan have been reported both in 1976–1981 [

11] and more recently [

10]. Every year, with the onset of the tick season, the media publish instructions for the population on how to prevent TBE infection (see, for example, [

12,

13]), which may also indicate the relevance of this problem in the region.

Assessing the spread and studying the specific characteristics of TBEV populations in low-endemic regions is a pressing task in the field of virology. Data on the genetic diversity of tick-borne encephalitis virus strains in Kyrgyzstan is practically absent, which makes this issue particularly interesting. Therefore, the aim of this study was to analyze the genetic diversity of TBEV in Kyrgyzstan.

In this study, we demonstrated for the first time that the TBEV-Sib and TBEV-FE subtypes were found in Kyrgyzstan. The TBEV-Sib subtype was represented by at least three genetic lineages: Zausaev, Vasilchenko and Bosnia. Given that different TBEV subtypes predominantly cause different forms of the disease, these data are important for predicting disease severity and providing direction for further study of tick-borne encephalitis in this region.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. TBEV Strains

In this study, the TBEV strains from the collection of the Scientific Сentre for Family Health and Human Reproduction Problems, Irkutsk, Russia (Collection №478258,

http://www.ckp-rf.ru) were used. The strains were isolated from

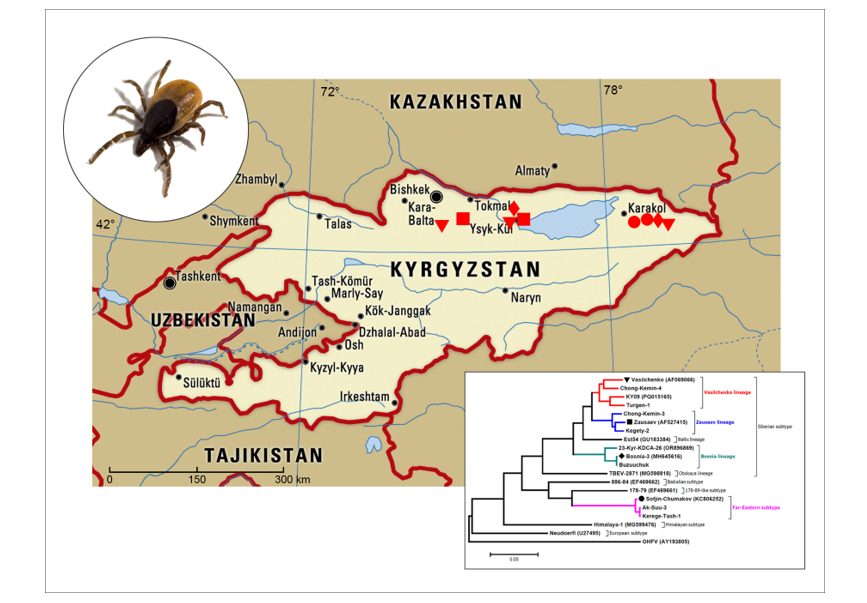

I. persulcatus ticks collected in Kyrgyzstan in 1986 (

Figure 1) and maintained by intracerebral inoculation to white non-linear mice weighing 6-7 g. Mice were housed in plastic cages (four to six animals per cage) under normal daylight conditions. Water and food were provided ad libitum. All animal procedures were carried out in accordance with the recommendations for the protection of animals used for scientific purposes (EU Directive 114 2010/63/EU). All experiments conducted on animals were approved by the local Bioethics Committee of the Scientific Сentre for Family Health and Human Reproduction Problems, Irkutsk, Russia (Protocol No. 3.5 dated Apr 07, 2021).

Information on TBEV strains, collection dates, isolation sources, and collection locations is presented in

Table 1.

The brain tissue samples from infected mice were placed in RNA/DNA shield solution (Zymo Research, USA) for inactivation, transport and preservation of RNA integrity.

2.2. TBEV RNA Isolation

RNA from TBEV strains was isolated from brain suspensions of infected mice using the QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

2.3. TBEV Genome Amplification and Sequencing

For primary screening for the presence of TBEV in the samples, reverse transcription followed by PCR (RT-PCR) was used with a set of oligonucleotide primers (TBEV_E7, 5' – GGCATAGAAAGGCTGACAGTG -3'; TBEV_E10, 5'- GATACCTCTCTCCACACAACCAG -3'), specific to the E-NS1 gene sequences of all TBEV subtypes, developed earlier [

16]. RNA libraries were prepared using the KAPA RNA HyperPrep Kit (Roche, Switzerland), and targeted enrichment of libraries was performed using SeqCap EZ technology (Roche, Switzerland) according to the manufacturer's protocol. For this purpose, a panel of oligonucleotides was designed to correspond to various fragments of the genomes of all known TBEV subtypes and genovariants, which are currently present in the GenBank database (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nucleotide/). The sequencing of the resulting libraries was performed with a new generation high-performance sequencer MiSeq (Illumina, USA). The variant of sequencing of paired end fragments (2x150) with the total number of cycles 300 was used.

2.4. Genome Assembly

The following pipeline was used for the genome assembly. The quality control of raw reads was performed with the FastQC software (

https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/). This software enables the determination of the overall quality profile of the reads by means of the Phred score metric, the number of adapters, the range of read lengths, the presence of contamination using the GC composition, and a number of other important parameters that determine the overall quality of libraries. The trimming of data was carried out with the fastp software [

17] from low-quality reads and trimming from technical sequences (adapters). Subsequently, the obtained data were subjected to mapping using the BWA-MEM software [

18] with the reference TBEV genome (GenBank: MH645618). The resulting .sam files were converted into .bam files using the SAMtools utility suite (

http://www.htslib.org/) with sorting and further deduplication with the Picard tool (

https://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/). Deduplicated .bam files were used to determine variants (alleles) with the GATK (Genome Analysis Toolkit) utility package (

https://gatk.broadinstitute.org/hc/en-us). This enabled the efficient identification and documentation of variants in .vcf format, thereby facilitating subsequent manipulation. Following acquisition of the .vcf files, the variants obtained were filtered within each file according to criteria such as depth of variant coverage (minimum 10 reads per variant) and quality of variant definition (minimum 20).

The FastaAlternateReferenceMaker utility, which is included in the GATK utility package, was used to generate an alternative reference genome sequence in the specified interval in .fasta format. Given a set of variants, the FastaAlternateReferenceMaker utility replaces the reference bases in the locations of the variations with the bases specified in the corresponding entries in the set. The determined TBEV genome coding region sequences were submitted to the GenBank database (PX470191–PX470197).

2.5. Genetic Analysis

Sequence alignment was performed using the ClustalW method with MEGA 6.0 software [

19]. The identity levels of the sequences were calculated using Unipro UGENE v. 52.1 software [

20]. Dendrograms were constructed in MEGA 6.0 software [

19] using the discrete maximum likelihood method [

21]. The most suitable substitution model for sequence analysis and dendrogram construction was selected using jModelTest [

22] and MEGA 6.0 [

19] software. The significance of the dendrograms was estimated using bootstrap analysis with 1000 replicates.

3. Results and Discussion

Complete genome sequences of seven TBEV strains were obtained, and the sequences of the genome coding regions were deposited in GenBank (accession numbers PX470191-PX470197). The choice of coding regions for deposition was determined, on the one hand, by their use for further analysis and, on the other hand, by the limitations of the sequence assembly method used, since the non-coding regions of the TBEV genome are variable, especially the 3'-untranslated region, and different reference sequences give different results when assembling these regions (data not shown).

Currently, in addition to the complete genome sequences of TBEV strains isolated from Kyrgyzstan presented in this paper, as of November 2025, the GenBank database contains five nucleotide sequences of TBEV genomes and their fragments from this territory, while among them, sequences with accession numbers OR555825 and OR555826 are short sequences of various fragments of the 23-Kyr-26 strain genome, for which the complete genome sequence OR896869 was later presented, and sequence HM641235 is a fragment of the complete genome sequence of KY09 strain (PQ015165) (

Table 1).

Using the sequences of the genome coding parts of the TBEV strains from this study and sequences from GenBank databese, a dendrogram was constructed to assess the genetic diversity of TBEV in Kyrgyzstan (

Figure 2).

Dendrogram analysis revealed that the Siberian subtype occupies a leading position in this region, and seven of the nine strains studied belonged to the Siberian subtype. Within the Siberian subtype, three strains belonged to the Vasilchenko genetic lineage (strains Chong-Kemin-4, Turgen-1, and KY09), two strains to the Zausaev genetic lineage (strains Chong-Kemin-3 and Kegety-2), and two strains to the Bosnia genetic lineage (strains 23-Kyr-KDCA-26 and Buzuuchuk). No strains belonging to the Baltic or Obskaya genetic lineages were found among the strains studied. In addition to strains of the Siberian subtype, two strains of the Far Eastern subtype were identified (strains Ak-Suu-3 and Kerege-Tash-1). No European, Baikal or Himalayan subtypes were found among the strains studied. In addition to the Siberian subtype, two strains of Far Eastern subtype (Ak-Suu-3 and Kerege-Tash-1) were identified. No European, Baikal or Himalayan subtype TBEV strains were found among those studied.

A comparison of the identified genetic variants of the virus and the locations of sample collection (

Figure 1) did not reveal any patterns, likely due to the small number of available TBEV strains. However, the data obtained made it possible to compare information on the genetic diversity of TBEV in territories neighbouring Kyrgyzstan.

Previously, only the Vasilchenko but not Zausaev genetic lineage of the TBEV Siberian subtype was found in south-eastern Kazakhstan [

23], although Kazakhstan is located close to Western Siberia, where the Zausaev genetic lineage occurrence is comparable to the Vasilchenko lineage [

3].

The discovery of the Buzuchuk and 23-Kyr-KDCA-26 TBEV strains is of particular interest. Previously, genetically similar TBEV variants were classified as belonging to the Bosnia genetic lineage within the Siberian subtype and were found in Bosnia, the Crimean Peninsula [

3], and south-eastern Kazakhstan [

23]. This genetic variant appears to be distributed close to the southern border of the TBEV range, since no similar isolates or strains of the virus have been found further north. It should be noted that this genetic variant represents a separate genetic lineage. Analysis of the identity levels of the genome coding region sequences between different lineages and within each lineage of TBEV Siberian subtype from the GenBank database demonstrated that Bosnia genetic lineage levels of similarity/difference fall within the boundaries of the genetic lineage division within the Siberian subtype (

Table 2). Within TBEV-Sib, the division border for identity level of nucleotide sequences was 92-95% between different lineages, and strains belonging to the Bosnia lineage meet this criterion.

The detection of the Far Eastern subtype in Kyrgyzstan is consistent with data from neighboring regions, particularly China, where the Far Eastern subtype is predominantly detected [Wu et al., 2024]. However, isolated TBEV strains of the Siberian subtype of the Vasilchenko genetic lineage have been described in the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, located near Kyrgyzstan [

24], and TBEV strain belonging to Zausaev genetic lineage was found in Inner Mongolia Province [

25]. As for other neighboring regions, there are no data available on TBEV or TBE in Uzbekistan and Tajikistan.

Thus, two TBEV subtypes, the Siberian and the Far Eastern, were found in Kyrgyzstan, which is probably the southernmost boundary of the range of these subtypes at present. Information on the occurrence of different subtypes in the study area is important for predicting the disease severity in patients, as previous studies have shown that the Far Eastern subtype predominantly causes more severe forms of tick-borne encephalitis. In contrast, the Siberian subtype is believed to cause a less severe disease with a tendency to develop chronic infections accompanied by diverse neurological and/or neuropsychiatric symptoms [

26]. Nevertheless, given the limited amount of data available, further in-depth study of TBEV in these areas is required.

4. Conclusions

Thus, the analyses of the seven new TBEV strains isolated in this study and two TBEV strains from GenBank database demonstrated that the Siberian subtype of three genetic lineages is predominantly distributed in Kyrgyzstan, and TBEV of the Far Eastern subtype is also presented. The findings underscore the necessity of conducting epidemiologic surveys of TBEV in this region that could benefit disease control and the prevention of TBEV infection in Kyrgyzstan.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.S.E. and K.I.V.; Methodology, T.S.E.; Software, K.G.V.; Formal Analysis, T.S.E., K.G.V.; Investigation, Sh.L.Kh., Sh.E.I., K.I.V., L.O.V., D.E.K., S.O.V., D.Yu.P. and Z.V.I.; Resources, Sh.E.I., K.I.V., and Z.V.I.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, Sh.L.Kh. and T.S.E.; Writing – Review & Editing, K.I.V. and Z.V.I.; Visualization, T.S.E. and K.I.V.; Project Administration, T.S.E. and Sh.E.I.; Funding Acquisition, T.S.E. and Sh.E.I.

Funding

This work was supported by the Strategic Academic Leadership Program of Kazan Federal University (PRIORITY-2030) (sequencing and analysis), the Quality Improvement project No. 65238411 of the Pfizer Inc. (method optimization) and the internal grant funding from the Scientific Centre for Family Health and Human Reproduction Problems No. 121022500179-0 (TBEV strains isolation and cultivation).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All animal procedures were carried out in accordance with the recommendations for the protection of animals used for scientific purposes (EU Directive 114 2010/63/EU). All experiments conducted on animals were approved by the local Bioethics Committee of the Scientific Сentre for Family Health and Human Reproduction Problems, Irkutsk, Russia.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Dr. Alla Bryanskaya, PhD (Universidade Estadual de Campinas (UNICAMP), Brazil) for her invaluable assistance in preparing the illustrative materials, and for her valuable comments and moral support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ORF |

Open reading frame |

| PCR |

Polymerase chain reaction |

| RT-PCR |

Reverse transcription followed by polymerase chain reaction |

| TBE |

Tick-borne encephalitis |

| TBEV |

Tick-borne encephalitis virus |

| TBEV-Eu |

European subtype of tick-borne encephalitis virus |

| TBEV-FE |

Far Eastern subtype of tick-borne encephalitis virus |

| TBEV-Sib |

Siberian subtype of tick-borne encephalitis virus |

References

- Current ICTV Taxonomy Release. Available online: https://ictv.global/taxonomy (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Dobler, G.; Erber, W.; Bröker, M.; Chitimia-Dobler, L.; Schmitt, H.J. (Eds.) The TBE Book, 8th edition; Global Health Press: Singapore, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkachev, S.E.; Babkin, I.V.; Chicherina, G.S.; Kozlova, I.V.; Verkhozina, M.M.; Demina, T.V.; Lisak, O.V.; Doroshchenko, E.K.; Dzhioev, Y.P.; Suntsova, O.V.; Belokopytova, P.S.; Tikunov, A.Y.; Savinova, Y.S.; Paramonov, A.I.; Glupov, V.V.; Zlobin, V.I.; Tikunova, N.V. Genetic diversity and geographical distribution of the Siberian subtype of the tick-borne encephalitis virus. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2020, 11, 101327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozlova, I.V.; Demina, T.V.; Tkachev, S.E.; Doroshchenko, E.K.; Lisak, O.V.; Verkhozina, M.M.; Karan, L.S.; Dzhioev, Yu.P.; Paramonov, A.I.; Suntsova, O.V.; Savinova, Yu.S.; Chernoivanova, O.O.; Ruzek, D.; Tikunova, N.V.; Zlobin, V.I. Сharacteristics of the Baikal subtype of tick-borne encephalitis virus circulating in Eastern Siberia. Acta Biomed. Sci. 2018, 3, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Shang, G.; Lu, S.; Yang, J.; Xu, J. A new subtype of eastern tick-borne encephalitis virus discovered in Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, China. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2018, 7, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tkachev, S.E.; Chicherina, G.S.; Golovljova, I.; Belokopytova, P.S.; Tikunov, A.Y.; Zadora, O.V.; Glupov, V.V.; Tikunova, N.V. New genetic lineage within the Siberian subtype of tick-borne encephalitis virus found in Western Siberia, Russia. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2017, 56, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karas’, F.R. Arboviruses in Kirgizia. Sborn Tr Inst Virus Im Ivanov Akad Med Nauk SSSR. 1978; pp. 40–44. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Timofeev, E.M.; Shakhgil’dyan, I.V.; Grebenyuk, Y.I.; Karas’, F.R. Results of serological examination of human blood sera and domestic animals with 15 arboviruses in southwestern districts of Osh Oblast in Kirghiz SSR. Sborn Tr Ekol Virus 1973, 1, 80–87. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Vargina, S.G.; Steblyanko, S.N.; Karas’, F.R.; Usmanov, R.K.; Gontar’, I.A.; et al. Investigation of viruses ecologically associated with birds of Chu Valley, Kirgizia. Sborn Tr Ekol Virus 1973, 74–80. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Briggs, B.J.; Atkinson, B.; Czechowski, D.M.; Larsen, P.A.; Meeks, H.N.; Carrera, J.P.; Duplechin, R.M.; Hewson, R.; Junushov, A.T.; Gavrilova, O.N.; Breininger, I.; Phillips, C.J.; Baker, R.J.; Hay, J. Tick-borne encephalitis virus, Kyrgyzstan. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011, 17, 876–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suranchieya, R.K.; Vargina, S.G. Clinical-epidemiologic observations in natural tick-borne encephalitis foci in Kirghizia. In Frunze Zdr Kirg; 1984; pp. 14–17. (In Ruissian) [Google Scholar]

- Tick-borne viral encephalitis. Prevention. How to protect yourself from a tick bite and what to do if you are not successful. May 03, 2022 Department of Disease Prevention and State Sanitary and Epidemiological Surveillance. Available online: https://dgsen.kg/novosti/kleshhevoj-virusnyj-jencefalit-profilaktika-kak-uberechsja-ot-ukusa-kleshha-i-chto-delat-esli-jeto-ne-udalos.html?pdf=3550 (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Ticks are becoming increasingly active in Kyrgyzstan. Healthcare professionals remind people not to ignore safety precautions. 18 April 2025. Available online: https://kg.mir24.tv/news/16631210/kleshi-stanovyatsya-vse-aktivnee-v-kyrgyzstane.-mediki-napominayut:-ignorirovat-mery-bezopasnosti-nelzya (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Jung, H.; Choi, C.H.; Lee, M.; Kim, S.Y.; Aknazarov, B.; Nyrgaziev, R.; Atabekova, N.; Jetigenov, E.; Chung, Y.S.; Lee, H.I. Molecular Detection and Phylogenetic Analysis of Tick-Borne Encephalitis Virus from Ticks Collected from Cattle in Kyrgyzstan, 2023. Viruses 2024, 16, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D'Addiego, J.; Curran-French, M.; Smith, J.; Junushov, A.T.; Breininger, I.; Atkinson, B.; Hay, J.; Hewson, R. Whole-genome sequencing surveillance of Siberian tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV) identifies an additional lineage in Kyrgyzstan. Virus Res. 2025, 351, 199517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rar, V.; Livanova, N.; Tkachev, S.; Kaverina, G.; Tikunov, A.; Sabitova, Y.; Igolkina, Y.; Panov, V.; Livanov, S.; Fomenko, N.; Babkin, I.; Tikunova, N. Detection and genetic characterization of a wide range of infectious agents in Ixodes pavlovskyi ticks in Western Siberia, Russia. Parasit Vectors 2017, 10, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. arXiv 2013, 1303.3997v2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Peterson, D.; Filipski, A.; Kumar, S. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2013, 30, 2725–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okonechnikov, K.; Golosova, O.; Fursov, M. the UGENE team. Unipro UGENE: a unified bioinformatics toolkit. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 1166–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felsenstein, J. Evolutionary trees from DNA sequences: a maximum likelihood approach. J. Mol. Evol. 1981, 17, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posada, D. jModelTest: phylogenetic model averaging. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2008, 25, 1253–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdiyeva, K.; Turebekov, N.; Yegemberdiyeva, R.; Dmitrovskiy, A.; Yeraliyeva, L.; Shapiyeva, Z.; Nurmakhanov, T.; Sansyzbayev, Y.; Froeschl, G.; Hoelscher, M.; Zinner, J.; Essbauer, S.; Frey, S. Vectors, molecular epidemiology and phylogeny of TBEV in Kazakhstan and central Asia. Parasit Vectors 2020, 13, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Lu, L.; Du, J.; Yang, L.; Ren, X.; Liu, B.; Jiang, J.; Yang, J.; Dong, J.; Sun, L.; Zhu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zheng, D.; Zhang, C.; Su, H.; Zheng, Y.; Zhou, H.; Zhu, G.; Li, H.; Chmura, A.; Yang, F.; Daszak, P.; Wang, J.; Liu, Q.; Jin, Q. Comparative analysis of rodent and small mammal viromes to better understand the wildlife origin of emerging infectious diseases. Microbiome 2018, 6, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Mao, M.; Chen, H.; Qi, R. Diversity of species and geographic distribution of tick-borne viruses in China. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1309698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruzek, D.; Avšič Županc, T.; Borde, J.; Chrdle, A.; Eyer, L.; Karganova, G.; Kholodilov, I.; Knap, N.; Kozlovskaya, L.; Matveev, A.; Miller, A.D.; Osolodkin, D.I.; Överby, A.K.; Tikunova, N.; Tkachev, S.; Zajkowska, J. Tick-borne encephalitis in Europe and Russia: Review of pathogenesis, clinical features, therapy, and vaccines. Antiviral Res 2019, 164, 23–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).