Submitted:

16 December 2025

Posted:

18 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

2.2. ddRADseq Library Preparation and Sequencing

2.3. ddRADseq Data Processing

2.4. Genetic Diversity, Structure and Statistic Analyses

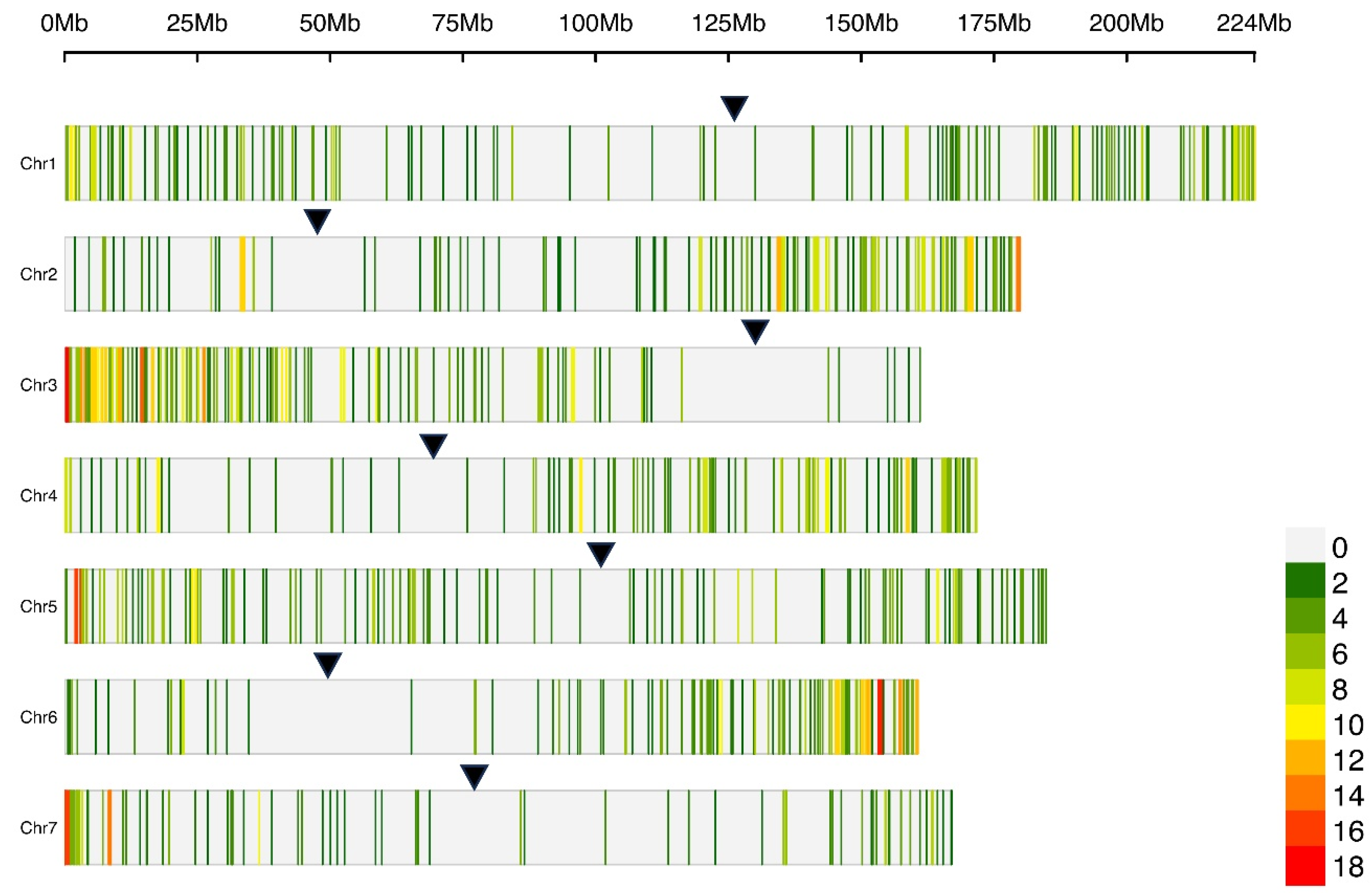

2.5. SNP Subset Selection for Core Set and Location in CDSs

3. Results

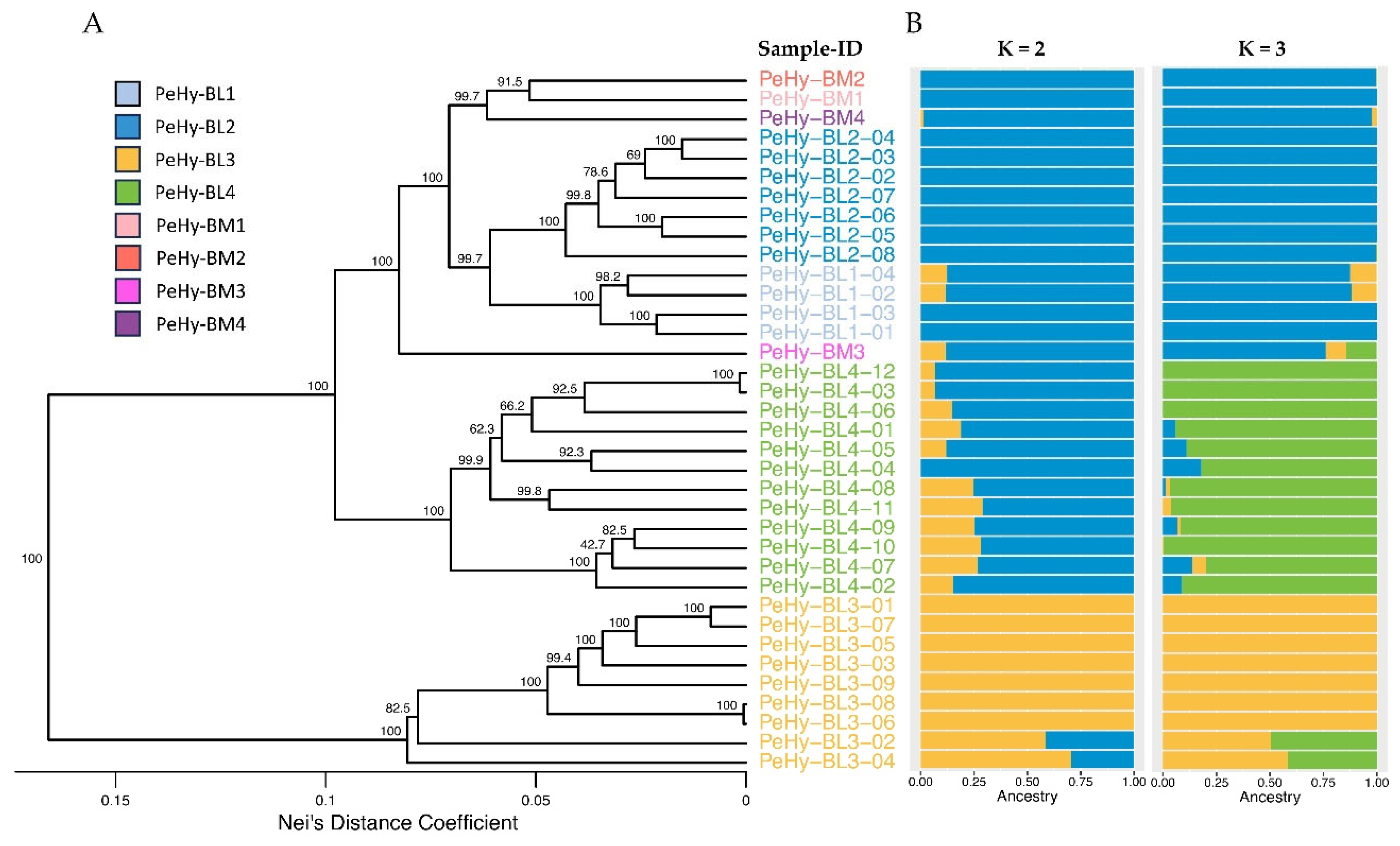

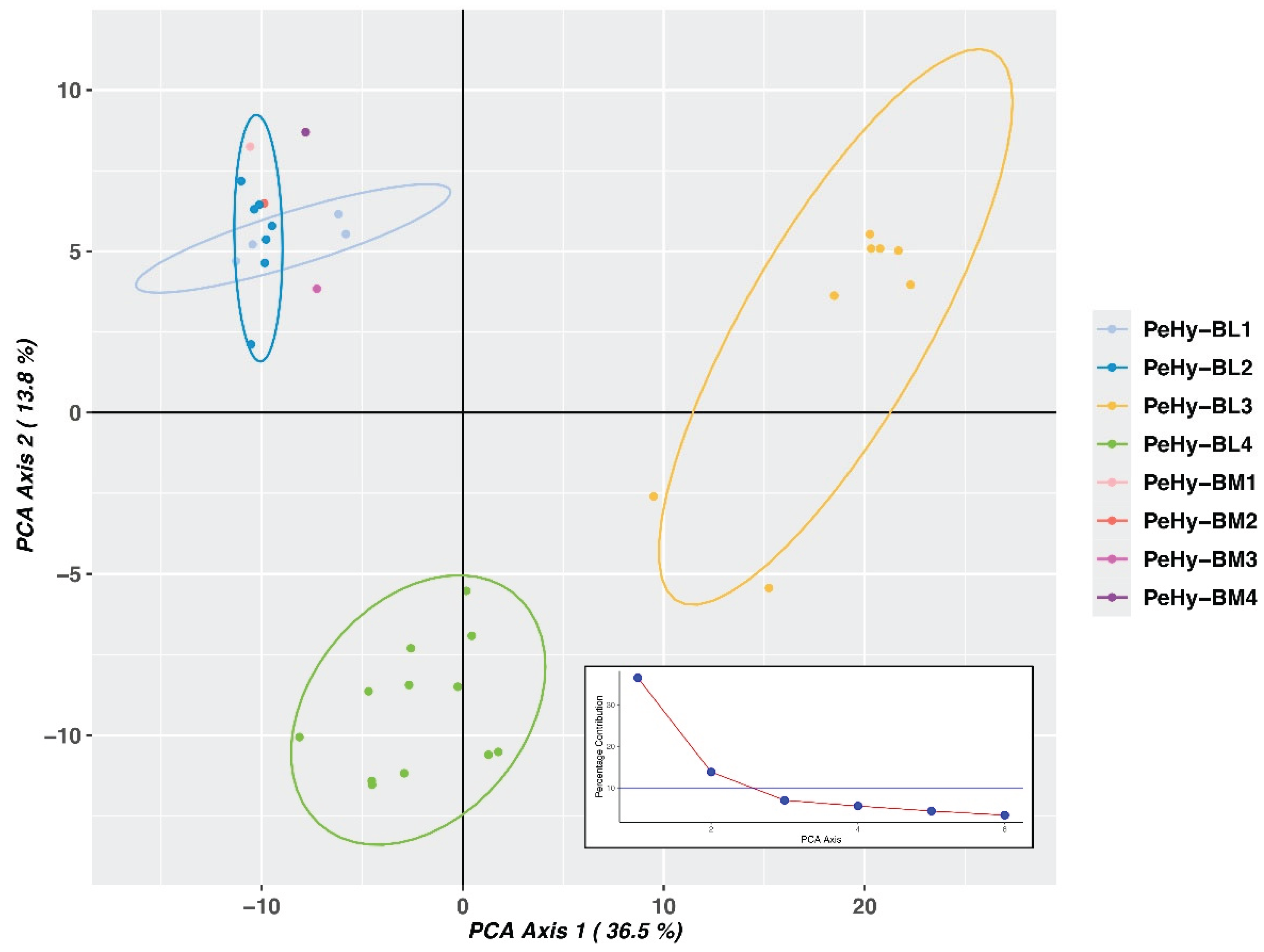

3.1. Genetic Diversity and Structure Analysis

3.2. Genetic Statistics and AMOVA

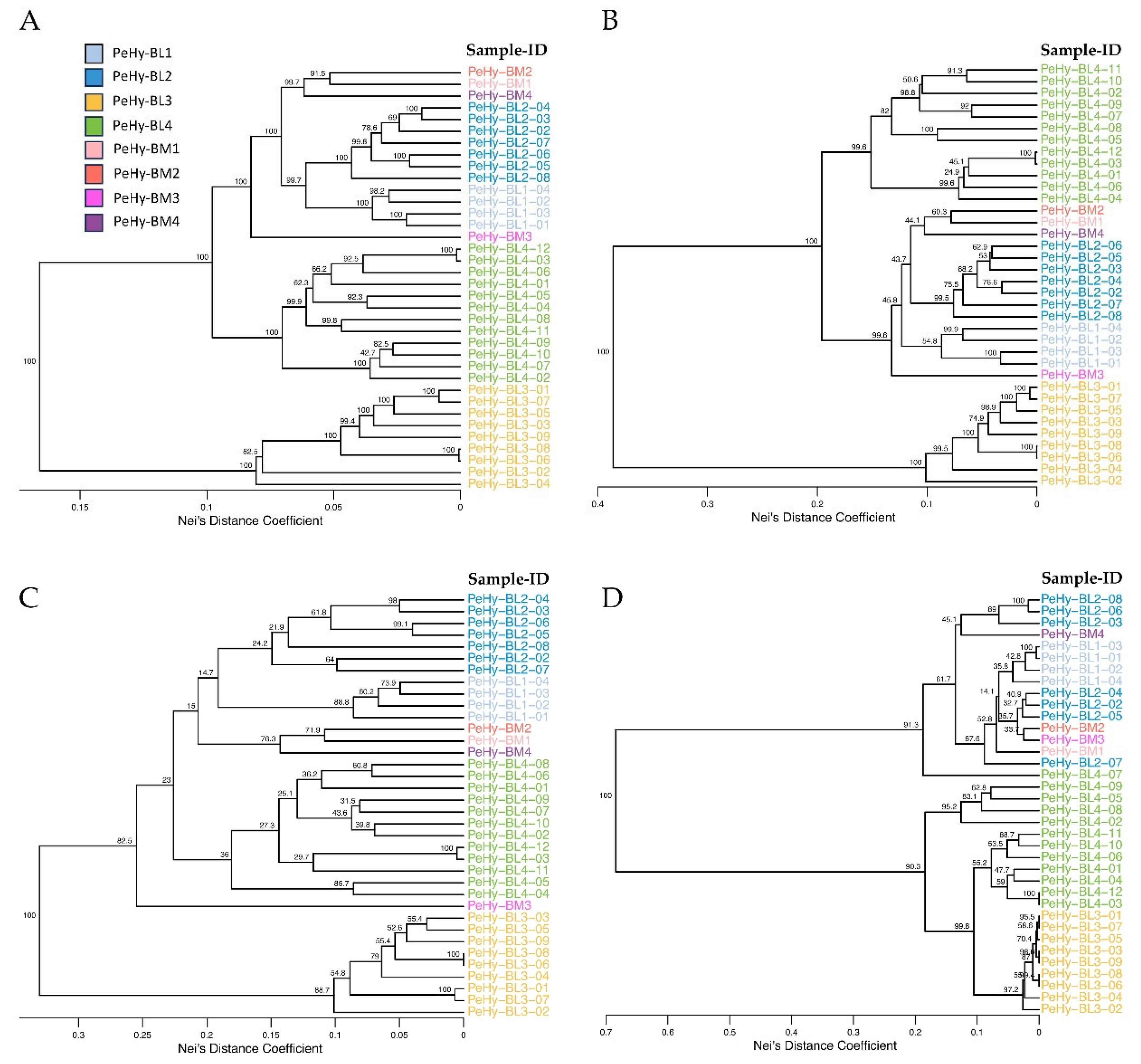

3.3. GD analysis Comparison between Total and Core Set SNP profiles

3.4. GD Analysis Comparison Between Total and CDS-Located SNP Profiles

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aswath, C.; Bose, T.K.; Bhatia, R.; Saha, T.N.; Dutta, K. Commercial Flowers; House, Daya Pub., Ed.; Daya Publishing, 2021; Vol. 4, ISBN 9789354614163. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q.X.C.; Warner, R.M. Identification of QTL for Plant Architecture and Flowering Performance Traits in a Multi-Environment Evaluation of a Petunia Axillaris × P. Exserta Recombinant Inbred Line Population. Horticulturae 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA Floriculture Crops 2020 Summary. Washington, DC, USA, 2021.

- Gebhardt, C. The Historical Role of Species from the Solanaceae Plant Family in Genetic Research. Theor Appl Genet 2016, 129, 2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sink, K.C. Petunia. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg 1984, 9. [CrossRef]

- Geitmann, A. Petunia. Evolutionary, Developmental and Physiological Genetics. Ann Bot 2011, 107, vi. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Warner, R.M. Dissecting Genetic Diversity and Genomic Background of Petunia Cultivars with Contrasting Growth Habits. Horticulture Research 2020, 7, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermann, K.; Klahre, U.; Venail, J.; Brandenburg, A.; Kuhlemeier, C. The Genetics of Reproductive Organ Morphology in Two Petunia Species with Contrasting Pollination Syndromes. Planta 2015, 241, 1241–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, D.M.; Caballero-Villalobos, L.; Turchetto, C.; Assis Jacques, R.; Kuhlemeier, C.; Freitas, L.B. Do We Truly Understand Pollination Syndromes in Petunia as Much as We Suppose? 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regalado, J.J.; Carmona-Martín, E.; Querol, V.; Veléz, C.G.; Encina, C.L.; Pitta-Alvarez, S.I. Production of Compact Petunias through Polyploidization. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult 2017, 129, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dermen, H. Polyploidy in Petunia. Am J Bot 1931, 18, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, T.P.; Harbord, R.M.; Sonneveld, T.; Clarke, K. The Molecular Genetics of Self-Incompatibility in Petunia Hybrida. Ann Bot 2000, 85, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.S.; Wu, L.; Li, S.; Sun, P.; Kao, T.-H.; Robbins, T.P.; Sims, T.L. Insight into S-RNase-Based Self-Incompatibility in Petunia: Recent Findings and Future Directions. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y.; Du, J.; Li, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; Wang, L.; Hu, H. Insight into the Petunia Dof Transcription Factor Family Reveals a New Regulator of Male-Sterility. Ind Crops Prod 2021, 161, 113196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nivison, H.T.; Hanson, M.R. Identification of a Mitochondrial Protein Associated with Cytoplasmic Male Sterility in Petunia. Plant Cell 1989, 1, 1121–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farinati, S.; Draga, S.; Betto, A.; Palumbo, F.; Vannozzi, A.; Lucchin, M.; Barcaccia, G. Current Insights and Advances into Plant Male Sterility: New Precision Breeding Technology Based on Genome Editing Applications. Front Plant Sci 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerats, T.; Vandenbussche, M. A Model System for Comparative Research: Petunia. Trends Plant Sci 2005, 10, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melzer, R.; Janssen, B.J.; Dornelas, M.C.; Vandenbussche, M.; Chambrier, P.; Rodrigues Bento, S.; Morel, P. Petunia, Your Next Supermodel? 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, P.; Heidmann, I.; Forkmann, G.; Saedler, H. A New Petunia Flower Colour Generated by Transformation of a Mutant with a Maize Gene. Nature 1987, 330:6149 1987(330), 677–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I.; Husnain, T.; Riazuddin, S. RNA Interference: The Story of Gene Silencing in Plants and Humans. In Elsevier Biotechnology advances; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Napoli, C.; Lemieux, C.; Jorgensen, R. Introduction of a Chimeric Chalcone Synthase Gene into Petunia Results in Reversible Co-Suppression of Homologous Genes. Trans. Plant Cell 1990, 2, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Guo, Y.; Yang, Q.; He, Y.; Fetouh, M.I.; Warner, R.M.; Deng, Z. Genome-Wide Identification of Quantitative Trait Loci for Important Plant and Flower Traits in Petunia Using a High-Density Linkage Map and an Interspecific Recombinant Inbred Population Derived from Petunia Integrifolia and P. Axillaris. Horticulture Research 2019, 1 2019(6), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Zhang, W.; Ruan, Y.; Dai, B.; Yang, T.; Gou, T.; Liu, C.; Ning, G.; Liu, G.; Yu, Y.; et al. Construction of a High-Density Genetic Map and Mapping of Double Flower Genes in Petunia. Sci Hortic 2024, 329, 112988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossolini, E.; Klahre, U.; Brandenburg, A.; Reinhardt, D.; Kuhlemeier, C.; Belzile, F. High Resolution Linkage Maps of the Model Organism Petunia Reveal Substantial Synteny Decay with the Related Genome of Tomato. Genome 2011, 54, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bombarely, A.; Moser, M.; Amrad, A.; Bao, M.; Bapaume, L.; Barry, C.S.; Bliek, M.; Boersma, M.R.; Borghi, L.; Bruggmann, R.; et al. Insight into the Evolution of the Solanaceae from the Parental Genomes of Petunia Hybrida. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saei, A.; Hunter, D.; Hilario, E.; David, C.; Ireland, H.; Esfandiari, A.; King, I.; Grierson, E.; Wang, L.; Boase, M.; et al. Chromosome-Level Genome Assembly and Annotation of Petunia Hybrida. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashikar, S.G.; Khalatkar, A.S. Breeding for Flower Colour in Petunia Hybrida Hort. Acta Hortic 1981, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man-Zhu, D.; Se-Ping, B. Advances in Genetics and Breeding of Petunia Hybrida Vilm. Chinese Bulletin of Botany 2004, 21, 385. [Google Scholar]

- Masclaux-Daubresse, C.; Daniel-Vedele, F.; Dechorgnat, J.; Chardon, F.; Gaufichon, L.; Suzuki, A. Nitrogen Uptake, Assimilation and Remobilization in Plants: Challenges for Sustainable and Productive Agriculture. Ann Bot 2010, 105, 1141–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lütken, H.; Clarke, J.L.; Müller, R. Genetic Engineering and Sustainable Production of Ornamentals: Current Status and Future Directions. Plant Cell Rep 2012, 31, 1141–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CPVO CPVO Legislation in Force. Available online: https://cpvo.europa.eu/en/about-us/law-and-practice/legislation-in-force (accessed on 27 October 2024).

- UPOV UPOV Lex. Available online: https://upovlex.upov.int/en/convention (accessed on 27 October 2024).

- CPVO Protocol for Tests on Distinctness, Uniformity and Stability Petunia Juss. and × Petchoa J. M. H. Shaw. Available online: https://cpvo.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/petunia_2.pdf (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- UPOV Guidelines for the Conduct of Tests for Distinctness, Uniformity and Stability - Petunia (Petunia Juss.). Available online: https://www.upov.int/en/publications/tg-rom/tg212/tg_212_1_corr.pdf (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Yu, J.K.; Chung, Y.S. Plant Variety Protection: Current Practices and Insights. Genes (Basel) 2021, 12, 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilliland, T.J.; Annicchiarico, P.; Julier, B.; Ghesquière, M. A Proposal for Enhanced EU Herbage VCU and DUS Testing Procedures. Grass and Forage Science 2020, 75, 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CPVO CPVO Guidance on the Use of Biochemical and Molecular Markers in the Examination of Distinctiveness, Uniformity and Stability (DUS). Available online: https://www.upov.int/edocs/tgpdocs/en/tgp_15.pdf (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Patella, A.; Scariolo, F.; Palumbo, F.; Barcaccia, G. Genetic Structure of Cultivated Varieties of Radicchio (Cichorium Intybus L.): A Comparison between F1 Hybrids and Synthetics. Plants 2019, Vol. 8 8, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seki, K.; Komatsu, K.; Hiraga, M.; Tanaka, K.; Uno, Y.; Matsumura, H. Development of PCR-Based Marker for Resistance to Fusarium Wilt Race 2 in Lettuce (Lactuca Sativa L.). Euphytica 2021, 217, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhigunov, A. V.; Ulianich, P.S.; Lebedeva, M. V.; Chang, P.L.; Nuzhdin, S. V.; Potokina, E.K. Development of F1 Hybrid Population and the High-Density Linkage Map for European Aspen (Populus Tremula L.) Using RADseq Technology. BMC Plant Biol 2017, 17, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, B.K.; Weber, J.N.; Kay, E.H.; Fisher, H.S.; Hoekstra, H.E. Double Digest RADseq: An Inexpensive Method for De Novo SNP Discovery and Genotyping in Model and Non-Model Species. PLoS One 2012, 7, e37135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiurugwi, T.; Kemp, S.; Powell, W.; Hickey, L.T. Speed Breeding Orphan Crops. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 2019, 132, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.; Deshpande, S.; Vetriventhan, M.; Upadhyaya, H.D.; Wallace, J.G. Genome-Wide Population Structure Analyses of Three Minor Millets: Kodo Millet, Little Millet, and Proso Millet. Plant Genome 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.; Hackett, C.; Hedley, P.; Liu, H.; Milne, L.; Bayer, M.; Marshall, D.; Jorgensen, L.; Gordon, S.; Brennan, R. The Use of Genotyping by Sequencing in Blackcurrant (Ribes Nigrum): Developing High-Resolution Linkage Maps in Species without Reference Genome Sequences. Molecular Breeding 2014, 33, 835–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praveen, P.; Gopal, R.; Ramakrishnan, U. The Population Structure of Invasive Lantana Camara Is Shaped by Its Mating System. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.J.; Liu, X.F.; Liu, D.T.; Cao, Y.R.; Li, Z.H.; Ma, Y.P.; Ma, H. Genetic Diversity and Structure of Rhododendron Meddianum, a Plant Species with Extremely Small Populations. Plant Divers 2021, 43, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, T.M.; Nazareno, A.G. One Step Away From Extinction: A Population Genomic Analysis of A Narrow Endemic, Tropical Plant Species. Front Plant Sci 2021, 12, 730258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Ramirez, A.R.; Bidot-Martínez, I.; Mirzaei, K.; Rasoamanalina Rivo, O.L.; Menéndez-Grenot, M.; Clapé-Borges, P.; Espinosa-Lopez, G.; Bertin, P. Comparing the Performances of SSR and SNP Markers for Population Analysis in Theobroma Cacao L., as Alternative Approach to Validate a New DdRADseq Protocol for Cacao Genotyping. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0304753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLean-Rodríguez, F.D.; Costich, D.E.; Camacho-Villa, T.C.; Pè, M.E.; Dell’Acqua, M. Genetic Diversity and Selection Signatures in Maize Landraces Compared across 50 Years of in Situ and Ex Situ Conservation. Heredity 2021 126:6 2021, 126, 913–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, C.; Aguirre, N.C.; Vera, P.A.; Filippi, C.V.; Puebla, A.F.; Poltri, S.N.M.; Paniego, N.B.; Acevedo, A. DdRADseq-Mediated Detection of Genetic Variants in Sugarcane. Plant Mol Biol 2023, 111, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, H.; Guo, J.; Yu, B.; Chen, W.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, X.; Chen, Y.; Huang, L.; Liu, N.; Ren, X.; et al. Construction of DdRADseq-Based High-Density Genetic Map and Identification of Quantitative Trait Loci for Trans-Resveratrol Content in Peanut Seeds. Front Plant Sci 2021, 12, 644402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martina, M.; Acquadro, A.; Gulino, D.; Brusco, F.; Rabaglio, M.; Portis, E.; Lanteri, S. First Genetic Maps Development and QTL Mining in Ranunculus Asiaticus L. through DdRADseq. Front Plant Sci 2022, 13, 1009206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ksouri, N.; Sánchez, G.; Forcada, C.F. i; Contreras-Moreira, B.; Gogorcena, Y. DdRAD-Seq-Derived SNPs Reveal Novel Association Signatures for Fruit-Related Traits in Peach. bioRxiv 2023, 2023.07.31.551252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daemi-Saeidabad, M.; Shojaeiyan, A.; Vivian-Smith, A.; Stenøien, H.K.; Falahati-Anbaran, M. The Taxonomic Significance of DdRADseq Based Microsatellite Markers in the Closely Related Species of Heracleum (Apiaceae). PLoS One 2020, 15, e0232471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Yoon, J.B.; Lee, J. Development of Fluidigm SNP Type Genotyping Assays for Marker-Assisted Breeding of Chili Pepper (Capsicum Annuum L.). Horticultural Science and Technology 2017 35:4 2017, 35, 465–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaglione, D.; Pinosio, S.; Marroni, F.; Di Centa, E.; Fornasiero, A.; Magris, G.; Scalabrin, S.; Cattonaro, F.; Taylor, G.; Morgante, M. PART OF A SPECIAL ISSUE ON BIOENERGY CROPS FOR FUTURE CLIMATES Single Primer Enrichment Technology as a Tool for Massive Genotyping: A Benchmark on Black Poplar and Maize. Ann Bot 2019, 124, 543–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Liu, D.; Zhang, X.; Li, W.; Liu, H.; Hong, W.; Jiang, C.; Guan, N.; Ma, C.; Zeng, H.; et al. SLAF-Seq: An Efficient Method of Large-Scale De Novo SNP Discovery and Genotyping Using High-Throughput Sequencing. PLoS One 2013, 8, 58700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonardi, S.; Sung, C.-J.; Kulkarni, R.; Hillhouse, A.; Simpson, C.E.; Cason, J.; Burow, M.D. Reduced-Cost Genotyping by Resequencing in Peanut Breeding Programs Using Tecan Allegro Targeted Resequencing V2. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Shi, X.; Chen, L.; Qin, J.; Zhang, M.; Yang, C.; Song, Q.; Yan, L.; Yang, Q.; et al. Development of SNP Marker Panels for Genotyping by Target Sequencing (GBTS) and Its Application in Soybean. 2023, 43, 26–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broccanello, C.; Chiodi, C.; Funk, A.; Mcgrath, J.M.; Panella, L.; Stevanato, P. Comparison of Three PCR-Based Assays for SNP Genotyping in Plants. Plant Methods 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.S.; Kang, M.Y.; Shim, E.J.; Oh, J.H.; Seo, K.I.; Kim, K.S.; Sim, S.C.; Chung, S.M.; Park, Y.; Lee, G.P.; et al. Genome-Wide Core Sets of SNP Markers and Fluidigm Assays for Rapid and Effective Genotypic Identification of Korean Cultivars of Lettuce (Lactuca Sativa L.). Hortic Res 2022, 9, uhac119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abed, A.; Légaré, G.; Pomerleau, S.; St-Cyr, J.; Boyle, B.; Belzile, F.J. Genotyping-by-Sequencing on the Ion Torrent Platform in Barley. Methods in Molecular Biology 2019, 1900, 233–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H. Aligning Sequence Reads, Clone Sequences and Assembly Contigs with BWA-MEM. Genomics 2013, 1303 . [Google Scholar]

- Danecek, P.; Bonfield, J.K.; Liddle, J.; Marshall, J.; Ohan, V.; Pollard, M.O.; Whitwham, A.; Keane, T.; McCarthy, S.A.; Davies, R.M. Twelve Years of SAMtools and BCFtools. Gigascience 2021, 10, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catchen, J.; Hohenlohe, P.A.; Bassham, S.; Amores, A.; Cresko, W.A. Stacks: An Analysis Tool Set for Population Genomics. Mol Ecol 2013, 22, 3124–3140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamvar, Z.N.; Tabima, J.F.; Gr̈unwald, N.J. Poppr: An R Package for Genetic Analysis of Populations with Clonal, Partially Clonal, and/or Sexual Reproduction. PeerJ 2014, 2014, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nei, M. Analysis of Gene Diversity in Subdivided Populations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1973, 70, 3321–3323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.C.; Chow, C.C.; Tellier, L.C.A.M.; Vattikuti, S.; Purcell, S.M.; Lee, J.J. Second-Generation PLINK: Rising to the Challenge of Larger and Richer Datasets. Gigascience 2015, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manichaikul, A.; Mychaleckyj, J.C.; Rich, S.S.; Daly, K.; Sale, M.; Chen, W.M. Robust Relationship Inference in Genome-Wide Association Studies. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 2867–2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Ploeg, A. Drawing Non-Layered Tidy Trees in Linear Time. Softw Pract Exp 2014, 44, 1467–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, B.; Unmack, P.J.; Berry, O.F.; Georges, A. Dartr: An r Package to Facilitate Analysis of SNP Data Generated from Reduced Representation Genome Sequencing. Mol Ecol Resour 2018, 18, 691–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pritchard, J.; Stephens, M.; Donnelly, P. Inference of Population Structure Using Multilocus Genotype Data. Genetics 2000, 155, 945–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Earl, D.A.; vonHoldt, B.M. STRUCTURE HARVESTER: A Website and Program for Visualizing STRUCTURE Output and Implementing the Evanno Method. Conserv Genet Resour 2012, 4, 359–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudet, J. Hierfstat, a Package for r to Compute and Test Hierarchical F-Statistics. Mol Ecol Notes 2005, 5, 184–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinnwell, J.P.; Therneau, T.M.; Schaid, D.J. The Kinship2 R Package for Pedigree Data. Hum Hered 2014, 78, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, G.S.; Singh, A.K.; Waters, D.L.E.; Henry, R.J. Molecular Markers for Harnessing Heterosis. Molecular Markers in Plants 2012, 119–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, A.; Villanueva, B.; Druet, T. On the Estimation of Inbreeding Depression Using Different Measures of Inbreeding from Molecular Markers. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.K.; Ha, S.T.T.; Lim, J.H. Analysis of Chrysanthemum Genetic Diversity by Genotyping-by-Sequencing. Hortic Environ Biotechnol 2020, 61, 903–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karikari, B.; Li, S.; Bhat, J.A.; Cao, Y.; Kong, J.; Yang, J.; Gai, J.; Zhao, T. Genome-Wide Detection of Major and Epistatic Effect QTLs for Seed Protein and Oil Content in Soybean Under Multiple Environments Using High-Density Bin Map. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2019, 20, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Ling, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Zhao, W.; Xiong, Y.; Dong, Z.; Yang, J.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, X.; Ma, X. RAD-Seq as an Effective Strategy for Heterogenous Variety Identification in Plants—a Case Study in Italian Ryegrass (Lolium Multiflorum). BMC Plant Biol 2022, 22, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean-Rodríguez, F.D.; Costich, D.E.; Camacho-Villa, T.C.; Pè, M.E.; Dell’Acqua, M. Genetic Diversity and Selection Signatures in Maize Landraces Compared across 50 Years of in Situ and Ex Situ Conservation. Heredity 2021, 126, 913–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltier, D.; Farcy, E.; Dulieu, H.; Bervillé, A. Origin, Distribution and Mapping of RAPD Markers from Wild Petunia Species in Petunia Hybrida Hort Lines. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 1994, 88, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galliot, C.; Hoballah, M.E.; Kuhlemeier, C.; Stuurman, J. Genetics of Flower Size and Nectar Volume in Petunia Pollination Syndromes. Planta 2006, 225, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strommer, J.; Peters, J.; Zethof, J.; De Keukeleire, P.; Gerats, T. AFLP Maps of Petunia Hybrida: Building Maps When Markers Cluster. Theor Appl Genet 2002, 105, 1000–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallejo, V.A.; Tychonievich, J.; Lin, W.K.; Wangchu, L.; Barry, C.S.; Warner, R.M. Identification of QTL for Crop Timing and Quality Traits in an Interspecific Petunia Population. Molecular Breeding 2015, 35, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; He, Y.; Gou, T.; Li, X.; Ning, G.; Bao, M. Identification of Molecular Markers Associated with the Double Flower Trait in Petunia Hybrida. Sci Hortic 2016, 206, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klahre, U.; Gurba, A.; Hermann, K.; Saxenhofer, M.; Bossolini, E.; Guerin, P.M.; Kuhlemeier, C. Pollinator Choice in Petunia Depends on Two Major Genetic Loci for Floral Scent Production. Current Biology 2011, 21, 730–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzi, P.H.; Guzmán-Rodriguez, S.; Giudicelli, G.C.; Turchetto, C.; Bombarely, A.; Freitas, L.B. A Convoluted Tale of Hybridization between Two Petunia Species from a Transitional Zone in South America. Perspect Plant Ecol Evol Syst 2022, 56, 125688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero-Villalobos, L.; Silva-Arias, G.A.; Turchetto, C.; Giudicelli, G.C.; Petzold, E.; Bombarely, A.; Freitas, L.B. Neutral and Adaptive Genomic Variation in Hybrid Zones of Two Ecologically Diverged Petunia Species (Solanaceae). Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 2021, 196, 100–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Wiegert-Rininger, K.E.; Vallejo, V.A.; Barry, C.S.; Warner, R.M. Transcriptome-Enabled Marker Discovery and Mapping of Plastochron-Related Genes in Petunia Spp. BMC Genomics 2015, 16, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Lin, W.K.; Chen, Q.; Vallejo, V.A.; Warner, R.M. Genetic Determinants of Crop Timing and Quality Traits in Two Interspecific Petunia Recombinant Inbred Line Populations. Sci Rep 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshire, R.J.; Glaubitz, J.C.; Sun, Q.; Poland, J.A.; Kawamoto, K.; Buckler, E.S.; Mitchell, S.E. A Robust, Simple Genotyping-by-Sequencing (GBS) Approach for High Diversity Species. PLoS One 2011, 6, e19379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berardi, A.E.; Esfeld, K.; Jäggi, L.; Mandel, T.; Cannarozzi, G.M.; Kuhlemeier, C. Complex Evolution of Novel Red Floral Color in Petunia. Plant Cell 2021, 33, 2273–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coste, C.F.D.; Bienvenu, François; Ronget, V.; Ramirez-Loza, J.-P.; Cubaynes, S.; Pavard, S.; Bienvenu, F. The Kinship Matrix: Inferring the Kinship Structure of a Population from Its Demography. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, E.A. Identity by Descent: Variation in Meiosis, Across Genomes, and in Populations. Genetics 2013, 194, 301–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rueda, M.A.R.; Briceño-Pinzón, I.D.; Miguel, L.A.; Martínez, J.L.Q.; Padua, L.N.; de Lima Ribeiro, R.H.; Martins, V.S.; de Souza, L.C.; da Silva Junior, A.L.; de Souza Marçal, T. Multivariate Analysis of Genetic Variability in Advanced Potato Clones Under Tropical Conditions. Agricultural Research 2025, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woldeyohannes, A.B.; Iohannes, S.D.; Miculan, M.; Caproni, L.; Ahmed, J.S.; de Sousa, K.; Desta, E.A.; Fadda, C.; Pè, M.E.; Dell’acqua, M. Data-Driven, Participatory Characterization of Farmer Varieties Discloses Teff Breeding Potential under Current and Future Climates. Elife 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COGEM Update on Unauthorised Genetically Modified Garden Petunia Varieties. Available online: https://cogem.net/en/publication/update-on-unauthorised-genetically-modified-garden-petunia-varieties/ (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Entani, T.; Takayama, S.; Iwano, M.; Shiba, H.; Che, F.S.; Isogai, A. Relationship between Polyploidy and Pollen Self-Incompatibility Phenotype in Petunia Hybrida Vilm. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 1999, 63, 1882–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Jiang, P.; Wilde, H.D. A Self-Pollinating Mutant of Petunia Hybrida. Sci Hortic 2014, 177, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lv, H.; Xiang, X.; Yang, A.; Feng, Q.; Dai, P.; Li, Y.; Jiang, X.; Liu, G.; Zhang, X. Construction of a SNP Fingerprinting Database and Population Genetic Analysis of Cigar Tobacco Germplasm Resources in China. Front Plant Sci 2021, 12, 618133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varshney, R.K.; Thiel, T.; Sretenovic-Rajicic, T.; Baum, M.; Valkoun, J.; Guo, P.; Grando, S.; Ceccarelli, S.; Graner, A. Identification and Validation of a Core Set of Informative Genic SSR and SNP Markers for Assaying Functional Diversity in Barley. Molecular Breeding 2008, 22, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, M.; Wei, S.J.; Wang, Y.Q.; Zhou, D.Y.; Ma, L.; Fang, D.; Yang, W.H.; Ma, Z.Y. Development of a Core Set of SNP Markers for the Identification of Upland Cotton Cultivars in China. JIAgr 2016, 15, 954–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, T.; Wang, C.; Ma, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, J.; Guo, G. CoreSNP: An Efficient Pipeline for Core Marker Profile Selection from Genome-Wide SNP Datasets in Crops. BMC Plant Biol 2023, 23, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pootakham, W.; Sonthirod, C.; Naktang, C.; Jomchai, N.; Sangsrakru, D.; Tangphatsornruang, S. Effects of Methylation-Sensitive Enzymes on the Enrichment of Genic SNPs and the Degree of Genome Complexity Reduction in a Two-Enzyme Genotyping-by-Sequencing (GBS) Approach: A Case Study in Oil Palm (Elaeis Guineensis). Mol Breed 2016, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gehring, M.; Henikoff, S. DNA Methylation Dynamics in Plant Genomes. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Gene Structure and Expression 2007, 1769, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mammadov, J.; Aggarwal, R.; Buyyarapu, R.; Kumpatla, S. SNP Markers and Their Impact on Plant Breeding. Int J Plant Genomics 2012, 2012, 728398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Pop-ID | N | Mn Bases | ≥Q20 Mn Bases | Mn Reads | MRL (bp) |

| PeHy-BL1 | 4 | 486.46 | 416.44 | 3.34 | 160 |

| PeHy-BL2 | 7 | 360.03 | 304.84 | 2.39 | 173 |

| PeHy-BL3 | 9 | 316.36 | 271.88 | 1.99 | 177 |

| PeHy-BL4 | 12 | 267.85 | 230.08 | 1.68 | 178 |

| PeHy-BM1 | 1 | 258.86 | 226.06 | 1.25 | 206 |

| PeHy-BM2 | 1 | 104.60 | 91.09 | 0.50 | 208 |

| PeHy-BM3 | 1 | 469.56 | 399.95 | 3.31 | 141 |

| PeHy-BM4 | 1 | 551.17 | 468.70 | 3.91 | 141 |

| Tot | 36 | 12291.01 | 10528.17 | 80.01 | - |

| Avg | 341.42 | 292.45 | 2.22 | 173 |

| GD | Cluster | Fst | ||||||

| PeHy-BL2 | ||||||||

| 6.93% | PeHy-BL1 | 0.23 | ||||||

| 10.51% | 9.85% | PeHy-BL4 | 0.23 | 0.22 | ||||

| 19.07% | 26.69% | 28.61% | PeHy-BL3 | 0.50 | 0.45 | 0.34 | ||

| PeHy-BL3 | PeHy-BL4 | PeHy-BL1 | PeHy-BL2 | PeHy-BL2 | PeHy-BL1 | PeHy-BL4 | PeHy-BL3 | |

| Pop ID | N | na | ne | Ho (%) | Hs (%) | Fis | PL (%) | PA (%) |

| PeHy-BL1 | 4 | 1.36 | 1.27 | 19.05 | 15.02 | -0.27 | 63.75 | 6.38 |

| PeHy-BL2 | 7 | 1.54 | 1.31 | 20.48 | 16.14 | -0.27 | 68.54 | 14.89 |

| PeHy-BL3 | 9 | 1.54 | 1.46 | 26.27 | 22.08 | -0.19 | 73.14 | 33.96 |

| PeHy-BL4 | 12 | 1.66 | 1.55 | 33.57 | 26.17 | -0.28 | 81.88 | 12.75 |

| Avg | 8 | 1.53 | 1.53 | 24.84 | 19.85 | -0.25 | 71.83 | 17.00 |

| StDev | 3 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 5.72 | 4.53 | 0.04 | 6.69 | 10.28 |

| Df | Sum Sq | Mean Sq | Est. Var. | Est. Var. (%) | |

| Between Subpopulations | 7 | 16100 | 2300 | 490 | 58.19 |

| Within Subpopulations | 28 | 9855 | 352 | 352 | 41.81 |

| Total | 35 | 25955 | 742 | 842 | 100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).